Abstract

Antibody-inducing vaccines are a major focus in the preventive HIV vaccine field. Because the most common tests for HIV infection rely on detecting antibodies to HIV, they may also detect antibodies induced by a candidate HIV vaccine. The detection of vaccine-induced antibodies to HIV by serological tests is most commonly referred to as vaccine-induced sero-reactivity (VISR). VISR can be misinterpreted as a sign of HIV infection in a healthy study participant. In a participant who has developed vaccine-induced antibodies, accurate diagnosis of HIV infection (or lack thereof) may require specialized tests and algorithms (differential testing) that are usually not available in community settings. Organizations sponsoring clinical testing of preventive HIV vaccine candidates have an ethical obligation not only to inform healthy volunteers about the potential problems associated with participating in a clinical trial but also to help manage any resulting issues. This article explores the scope of VISR-related issues that become increasingly prevalent as the search for an effective HIV vaccine continues and will be paramount once a preventive vaccine is deployed. We also describe ways in which organizations conducting HIV vaccine trials have addressed these issues and outline areas where more work is needed.

Scope of the Problem

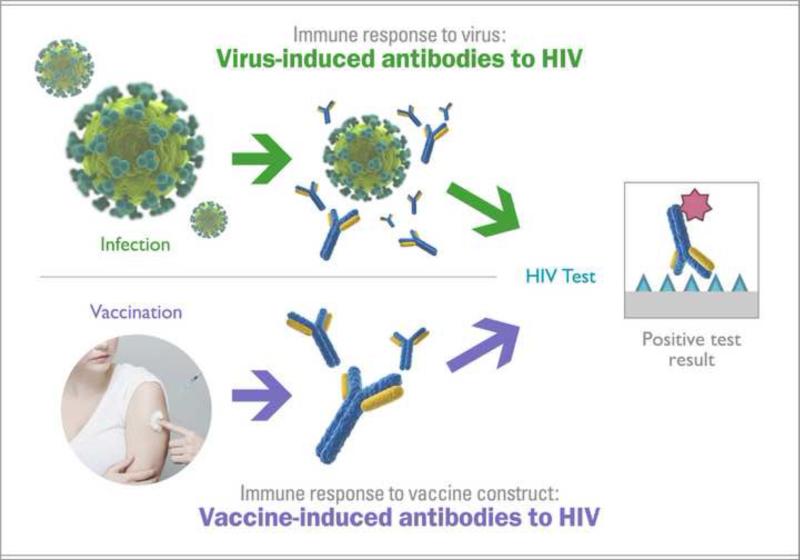

The detection of vaccine-induced antibodies to HIV by serological tests is most commonly referred to as vaccine-induced sero-reactivity (VISR)† or vaccine-induced sero-positivity (VISP) (Fig. 1). While eliciting broadly-reactive, long-lasting antibody responses to HIV is generally viewed as desirable for HIV vaccine candidates1–5, trial participants that develop antibodies to HIV and, as a result, VISR status, may experience a number of challenges in their day-to-day life. Social harms associated with VISR have included disruption of personal relationships; difficulties in finding or keeping employment; difficulties in obtaining insurance; impediments to travel; inability to enlist into the military; inability to donate blood, sperm, and organs; and inappropriate medical treatment (Table 1).

Fig 1.

Results of commonly used serology-based tests are inconclusive with regard to HIV infection status in participants with VISR. The tests may not differentiate between vaccine-induced antibodies and antibodies present as a result of an HIV infection. Trial participants with VISR may be incorrectly perceived as being HIV-positive. Because the person with vaccine-induced antibodies could still become infected with HIV, VISR-status may lead to delayed diagnosis of infection.

Table 1.

Study participants with VISR may experience social harms associated with the misunderstanding of their HIV status

| Area of daily life | Potential social harms | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Personal relationships and stigma in the society | Family members, loved ones, and co-workers may have negative reactions to trial participation or misinterpret VISR as true HIV infection. | The stigma of being associated with HIV ‘positivity’ was reported as a major concern for potential trial volunteers23,24 and was the main social harm in the CAB consultations conducted by the Enterprise. |

| Employment | Employers may discriminate against a potential employee perceived as being HIV positive. | Reported cases have been rare, but the potential impact is serious25,26. |

| Insurance (medical/dental, disability, or life) | In some countries, insurance companies may request an HIV test from an applicant to check for pre-existing conditions and could deny insurance or charge a higher premium from a person perceived to be HIV-infected. | Trial sponsors can intervene by providing confirmation of participation and true HIV status; however, companies are not legally compelled to accept test results from CRSs. The insurance industry of the Republic of South Africa has implemented guidelines for HIV testing of individuals applying for insurance who identify as HIV vaccine study participants. These testing guidelines are incorporated into laboratory test requisitions27. |

| Travel - immigration | A volunteer with VISR may be denied a visa as a result of an HIV test during the medical exam portion of a visa application28,29. | For a small number of countries that require an HIV test for entry, visa applicants with VISR should contact the embassy of the destination country and inquire if an HIV test result from a specific laboratory is acceptable or if they need to contact the trial sponsor for assistance in providing comprehensive documentation of their true HIV status. International travelers may also benefit from alerting their own country's consulate in the event that further assistance is needed once abroad. |

| Military career, blood banking within military, and deployment | For some countries with high prevalence, HIV infection is not exclusionary to military service. In the US, individuals with VISR are ineligible to join the military. If already enrolled, they cannot be deployed because they cannot be blood donors in the field30,31. | Potential trial volunteers in the US need to be clearly informed that development of VISR may make them ineligible to serve in the US military and eliminate military service as a career option for the foreseeable future. Keefer et al. reported a case that was resolved after the trial sponsor established HIV-negative status32. US soldiers are excluded from enrollment in the military's own HIV vaccine trials33. |

| Blood, organ, stem cell, and sperm donations | A person with VISR may be rejected on the basis of testing uncertainty. The inability to donate may be considered a social harm by volunteers and may also prevent lifesaving medical procedures for loved ones and patients in critical conditions. | In France and the USA, volunteers with VISR are not allowed to donate blood. In Thailand, trial volunteers must produce proof that they were enrolled in the placebo arm of an HIV vaccine trial to be able to donate blood. Confirmation of HIV-negative status of a participant with VISR may not change the exclusion from blood donation per Red Cross guidelines34. |

| Newborn HIV prophylaxis in the context of PMTCT | A newborn in the clinic or hospital may be given antiretroviral drugs as prophylaxis if the mother has VISR and is tested with a rapid test during labor. | One case is known in the US wherein a newborn was placed on ART due to the mother's VISR. ART was discontinued after the mother self-identified as a vaccine volunteer, the trial site confirmed study participation, and confirmatory tests were conducted35. There was another case in the US where a newborn was about to be placed on ART due to the mother's VISR status despite the mother self-identifying as a vaccine trial volunteer; initiation of ART was avoided after the trial site was contacted, and confirmatory tests were conducted36. |

In clinical studies, the frequency of VISR has varied extensively depending on several factors (Table 2). The profile of the elicited immune responses and resulting VISR is affected by various characteristics of the HIV vaccine candidates, such as the viral components being targeted and the delivery technologies used. Small changes in vaccine regimens, such as the dose of a single component, may affect VISR frequency. In addition, duration of VISR status is also very variable. In some cases HIV antibody responses have persisted for more than 20 years after vaccination6.

Table 2.

Examples of variability in VISR incidence and duration. For the same candidate vaccine, VISR rates can vary greatly depending on which test is used (1-a vs. 1-b and 1-c; 2-a vs.2-b; 4-a vs.4-b) and by treatment groups. A 10-fold difference in the dose of one component can drastically influence the rate of VISR detected by the same test (6-a vs.6-b).

| Vaccine trial and regimen | HIV assay | Incidence of VISR at end of study (6 months) | Durability of VISR over time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | VRC DNA/Ad5 - EnvABC, Gag, Pol (Nef) HVTN20433 |

a | Bio-Rad GS HIV 1/2 Plus O EIA | 6% | 0 % after 5 years |

| b | Abbot HIVAB HIV-1/HIV-2 (rDNA) EIA | 85.8% | NA | ||

| c | Abbott AxSYM HIV Ag/Ab Combo | NA | 84.3% after 5 years | ||

| 2 | Ad26-EnvA/Ad35-EnvA HVTN 910 (IAVI B003)33 | a | Bio-Rad Multispot HIV-1/HIV-2 Rapid Test | 12.5% | NA |

| b | bioMerieux Vironostika HIV Ag/Ab | 96.8% | NA | ||

| 3 | ALVAC- HIV vCP125/gp160 gp160/peptide V3 ANRS VAC01 and VAC0221 |

Bio-Rad Genscreen ULTRA HIV Ag-Ab | NA | 33% after 16.5 years | |

| Biotest Anti-HIV TETRA ELISA | NA | 44% after 16.5 years | |||

| 4 | ALVAC –HIV vCP1452 or vCP205 ANRS VAC03 and VAC1021 |

a | Bio-Rad Genscreen ULTRA HIV Ag-Ab | NA | 0% after 8 years |

| b | Biotest Anti HIV TETRA ELISA | NA | 18% after 8 years | ||

| 5 | ALVAC-HIV (vCP1521)/AIDSVAX B/E MHRP RV14411 |

bioMerieux Vironostika HIV Ag/Ab | 0.4% | NA | |

| 6 | rAd5 109 VLP/NYVAC-B/NYVAC-B HVTN078, Treatment Group 333 |

a | Abbott ARCHITECHT HIV Ag/Ab Combo | 0.0 % | NA |

| rAd5 1010 VLP/ NYVAC-B/NYVAC-B HVTN078, Treatment Group 433 |

b | 46.7% | NA |

Commercially available tests have different specificity and sensitivity, which may result in different VISR outcomes. A study participant who tested sero-negative at the time of study exit may still harbor HIV antibodies that could be detected by different or newly available tests. Therefore a negative VISR status at the end of a study does not guarantee that a participant will not need differential testing in the future.

While developing antibodies to HIV does not result in physiological harm, the evolution of the HIV diagnostic and vaccine research fields have created the potential for negative social impacts for individuals with such vaccine-induced antibodies. This situation can be addressed on two fronts: changes in diagnostic technologies and measures to prevent or mitigate social harms.

Technical approaches to differentiate vaccine-induced responses from infection

The confounding effects of VISR on HIV diagnostics are due to the fact that these tests are based on detection of antibodies (Fig. 1). Although the fourth generation of diagnostic HIV tests include detection of viral antigens, they continue to detect antibodies and, therefore, are unlikely to address VISR challenges 7,8.

One way to prevent the complications of VISR is to develop tests that detect non-vaccine antibody responses or viral components, such as proteins, RNA, or DNA and to promote their use in community settings. Several small companies are making good progress toward differential tests. One such example is HIV-Selectest9–11, which is being developed by Immunetics, Inc. HIV-Selectest detects antibodies to a region in gp41 that is rarely included in vaccine immunogens and can therefore be used for differential serologic testing. HIV-Selectest has been tested against specimens from a number of clinical trials with good results11,12.

With regard to detecting viral components, monoclonal antibodies can be used to detect viral proteins, such as capsid protein (p24), in the blood, but tests based on this strategy must overcome the challenge of plasma antibodies competing with the assay antibody. Detection of HIV RNA by quantitative PCR is highly accurate and is used in management of HIV disease. However, this assay is complex, expensive, and may give false-negative results in individuals who naturally control viral load or are on ARV medications. Qualitative nucleic acid (DNA or RNA or both) assays face similar challenges, but may provide a cheaper and more reliable alternative. The only nucleic acid-based diagnostic test for HIV infection approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the Aptima HIV-1 RNA assay (Hologic), and there are few point-of-care nucleic acid-based diagnostic tests in development.

In addition to the challenge of technological feasibility, the tests must be adaptable to low-resource settings where electricity and cold chain are not always available. These technologies must also be portable, easy to use with little training, and inexpensive to operate. From a regulatory perspective, the FDA considers HIV tests as Class III devices (i.e., high-risk medical devices), which is the most stringent regulatory category13. Therefore the development of differential HIV tests capable of distinguishing VISR from HIV infection entails more regulatory and logistical complexities than other diagnostic areas, discouraging large diagnostic companies from investing in such specialized tests.

Licensure of an HIV vaccine would drastically increase the need for differential testing. However, in the absence of a widely available HIV vaccine, serological tests are likely to remain the primary diagnostic approach. Thus, it is highly unlikely that the challenges that trial participants with VISR face in the community will have simple/rapid technological solutions in the near future. Therefore, it is up to the organizations sponsoring these studies to help study participants avoid social harm by offering support and state-of-the art diagnostic testing.

Current practices and areas for improvement

The issues associated with VISR have been recognized for years, and organizations conducting clinical HIV vaccine studies are addressing them to various degrees. The solutions can be divided into four general categories: (a) educate participants of the potential for VISR and how it may impact their lives, (b) provide ongoing differential testing for former vaccine trial participants who have VISR, (c) help manage any social harms that occur as a result of the participant's VISR status, and (d) educate the investigators, community, healthcare providers about VISR. A survey of nine organizations conducting HIV vaccine clinical trials showed that while the most essential of these activities are implemented by many of the organizations, other activities are less widespread or need to be refined (Table 3).

Table 3.

Current practices that organizations conducting HIV vaccine trials use to address VISR‡

| Survey question | # of organizations answering YES |

|---|---|

| Inform participants of the potential for VISR and how it may impact their lives | |

| The protocol informed consent describes VISR and associated risks | 9 |

| Provide accurate testing for former trial participants who have VISR | |

| End of study HIV testing to asses risk of VISR, performed with locally available tests | 9 |

| Post-study differential VISR vs. HIV infection testing provided as long as needed | 9 |

| Participants who relocate can access VISR vs. HIV infection testing remotely | 5 |

| A long-term mode for contact is provided in the event that CRS closes | 7 |

| Help manage any social harms that occur as a result of the participant's VISR status | |

| The protocol collects laboratory data on VISR | 9 |

| The protocol collects data on VISR related social impact | 5 |

| Post-study enrollment in long-term follow up study offered | 5 |

| Assistance is provided to participants with VISR in regards to social harms | 9 |

| Research staff maintains records with identifiers and study regimen of participants who may need support with VISR related issues | 9 2 Registries |

| Inform scientists, health care providers, and the community about the existence of VISR | |

| Information about VISR was presented at meetings attended by investigators and healthcare practitioners | 8 |

| Data about VISR was published in scientific journals | 7 |

| In-country blood banks have been informed about VISR | 5 |

Survey conducted by NIAID and the Global HIV Vaccine Enterprise (2013-2014). Organizations participating: ANRS: Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le SIDA- Vaccine Research Institute, France; China CDC: Chinese Center for Disease Control, China; EDCTP: European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership, The Netherlands; IAVI: International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, US; HVTN: HIV Vaccine Trials Network, US; UK HVC: HIV Vaccine Consortium, UK; US MHRP: Military HIV Research Program, US.

Educate study participants about VISR

All surveyed organizations provide information to study participants about the existence of VISR at the time of informed consent. The participants are told that they should be tested for HIV infection only at clinical research sites (CRS) and strongly advised against community-based testing. The participants are informed that VISR may persist for prolonged periods of time, perhaps years, and that the study organization or sponsor will provide long-term support to ensure accurate testing and to address any resulting social harms. At the end of study, participants with VISR status are counseled to contact their CRS before any community-based HIV testing and to inform their regular doctor about their participation in a vaccine study. However, according to recommendations for HIV testing by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, individuals can be tested for HIV under a general consent for all medical care and that pre-test counseling is not required as part of screening programs in healthcare settings14. While individuals can “opt-out” of HIV testing, the process may be confusing for some, especially if they are not aware of this practice beforehand and/or present at a hospital for an emergency. The availability of over-the-counter in-home tests may further exacerbate these HIV testing challenges.

Recommended: trial sponsors to strongly advise all participants to inform their primary care physician about their participation in an HIV vaccine trial and the possibility of VISR.

Providing accurate testing in the long term

At the end of the study, participants are tested for HIV infection using study-specific diagnostic algorithms and for VISR using diagnostic serologic kits used in the community. This service is provided by all organizations surveyed.

Commercially available tests are constantly evolving, and new tests may have different specificity or sensitivity for detecting vaccine-induced antibodies. Alternatively, participants may relocate to a community where different commercial HIV screening tests are used, which could also lead to a change in VISR status. Therefore, all trial participants, even those without VISR at the end of study, may need differential testing in the future.

Differential testing after the trial is typically managed through the CRS. If participants move away from their original study site, access to long-term testing may be compromised. If no other CRS exists near a relocated participant, arrangements have to be made to draw blood and to ship the samples back to the organization or affiliated laboratory for testing. Only five of the nine surveyed organizations have a system in place for remote testing; other organizations indicated that they provide such support on a case-by-case basis.

Recommended: trial sponsors to establish procedures to provide accurate HIV testing to all participants for as long as needed.

Unknowns about the frequency and durability of VISR make it challenging for trial sponsors to plan and budget for long-term testing. As the number of participants in HIV vaccine clinical trials increases, the cost to manage long-term HIV testing for participants is expected to become a major expense for clinical trial programs.

Recommended: the HIV vaccine field, together with regulatory authorities and public health agencies, to set aside contingency resources to assure that trial records are maintained and all testing needs are met in the future, independent of funding availability for individual programs.

Confirming trial participation

All clinical trial organizations maintain records with identifiers and study regimens that can verify a person's participation in the vaccine arm of a study. However, since the records are usually maintained by the trial sites, it may be difficult for participants to gain access to the information if the site closes or the participant relocates. The HVTN has addressed this issue by creating the “VISP Testing Service”15 with a toll free number for the US (and soon for South Africa) distributed in emails and brochures and posted on the HVTN website to ensure participants have a permanent contact with the sponsor.

Recommended: trial sponsors to provide a permanent point of contact for all trial participants to obtain confirmation of participation in the vaccine arm of a study.

Because records are not kept in a centralized location, the time to access records may vary depending on the responsiveness of the trial site. To quickly identify former trial participants, some organizations have created dedicated registries in which the name of the participant is readily matched to the study regimen and identifiers.

The HVTN, for example, created the “VISP Registry”15 and recently mandated that all trial participants be included in the registry. The United States Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (USAMRMC) in the US and Thailand also collects data from all trial participants into the ‘Volunteer Registry Database’.

While the creation of regional or national study participant registries has been strongly advised by some, it faces a number of challenges: merging data from different trial organizations into a common secure database is technically complex, in-country regulatory authorities and ethics committees need to be consulted, and such registries must comply with local privacy laws.

Recommended: trial sponsors to consider creating a secure participant registry to facilitate access to records, including cross-sponsor regional or national registries.

Once trial participation is confirmed, trial sponsors can communicate on behalf of the participant and/or issue documentation such as a “certificate of trial participation” to help the participants demonstrate their need for specialized HIV testing. The certificate is a portable identifier that documents past participation in a vaccine study, but cannot attest to the current HIV status of the individual. For example, the NIAID Vaccine Research Program offers photo ID cards that indicate participation in a trial (the word “HIV” is not included to reduce the chances of stigmatization) and provide contact information for the CRS. However, individuals may decline the card or be uncomfortable carrying such a document.

Raising awareness about the existence and impact of VISR

Information about VISR frequency, duration, and impact on life needs to be gathered and disseminated to relevant stakeholders.

Scientific community

While it is impossible to predict the frequency and duration of VISR before a trial, clinical researchers need to be prepared to prevent and mitigate various social harms encountered by participants with VISR. Multiple groups have presented at conferences and published peer-reviewed articles on the rate and durability of VISR in trial participants, as well as on social harms16–21.

Five clinical trial organizations offer participants the opportunity to enroll in long-term follow-up (LTFU) observational studies once the trial is closed. These studies are IRB approved and can be used for research purposes, including research on the incidence and duration of VISR and the nature of social harms. Such trials may help clarify the actual needs of participants with VISR in the future. Participants can be followed either for a set number of years or for an open-ended period, as in the HVTN 910 protocol15. While all organizations encourage enrollment in LTFU studies, access to testing is not contingent on participation.

The data on VISR will continue to evolve as new vaccine candidates and HIV tests are developed. The data regarding country-specific challenges remain sparse.

Recommended: the research community to continue to study VISR and publish systematic studies and case reports to enable clinical researchers to better anticipate, prevent, and mitigate the impact of VISR on participants.

Healthcare providers

Education of healthcare providers could significantly reduce VISR-related issues. When HIV testing is performed at the doctor's office, the physician who knows to ask about the patient's past or current participation in a vaccine trial can avoid potential misdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment. Physicians should also be aware of the availability of differential testing performed by trial sponsors. As an example, the FHCRC/University of Washington Vaccine CRS, located in Seattle, WA, worked with public health authorities in Washington State to incorporate VISR education into state-mandated healthcare provider training, including the health department's training sessions on HIV testing and counseling15. Websites, such as the public section of HVTN's website on VISP22, can be a useful resource both to physicians and to participants.

Recommended: trial sponsors to inform and educate healthcare providers about VISR in the areas where sponsors are conducting clinical trials.

HIV testing

In 2006, the US CDC published its Revised Recommendations for HIV Testing of Adults, Adolescents, and Pregnant Women in Health-Care Settings, which specifically mentions participants in HIV vaccine trials: “Recipients of preventive HIV vaccines might have vaccine-induced antibodies that are detectable by HIV antibody tests. Persons whose test results are HIV positive and who are identified as vaccine trial participants might not be infected with HIV and should be encouraged to contact or return to their trial site or an associated trial site for the confirmatory testing necessary to determine their HIV status” 14. Similar considerations are expected to be included in the updated 2014 guidelines (personal communication to authors from Michele Owen, CDC).

Recommended: in-country health authorities to ensure that national guidelines for HIV testing identify VISR as a potential confounder for interpreting serological test results.

In the US, the FDA works with manufacturers to include the following language about VISR in package inserts for HIV serological tests: “A person who has antibodies to HIV-1 is presumed to be infected with the virus except that a person who has participated in an HIV vaccine study may develop antibodies to the vaccine and may or may not be infected with HIV.” The World Health Organization could play a role in helping to ensure that similar advisory language is implemented worldwide, e.g. through its prequalification processes for medicinal products, including diagnostic tests.

Recommended: test manufacturers to include language about the possibility of VISR interference with testing in package inserts for commercially available serological HIV tests worldwide.

Conclusions

VISR may be viewed as a straightforward challenge that can be addressed using available technologies. However, the unpredictable nature of the phenomenon, its potentially long duration, and the complexity of social interactions associated with HIV testing make the delivery of these technologies expensive and logistically challenging. Trial sponsors recognize an ethical obligation to support trial participants to the best of their abilities, and many sponsors currently spend considerable resources to study and mitigate the potential harms encountered by participants with VISR. However, more long-term and universally applicable solutions are needed. In this article, we aimed to identify the gaps in the current landscape as well as the stakeholders best positioned to take action in each area (Box 1). These recommendations may serve as a field-wide roadmap to a coordinated effort and as a baseline for assessing the state of the field in the future.

Box 1: Summary of recommendations.

It is recommended that

➢ Trial sponsors strongly advise all participants to inform their primary care physician about their participation in an HIV vaccine trial and the possibility of VISR

➢ Trial sponsors establish procedures to provide accurate HIV testing to all participants for as long as needed

➢ The HIV vaccine field, together with regulatory authorities and public health agencies, to set aside contingency resources to assure that trial records are maintained and all testing needs are met in the future, independent of funding availability for individual programs

➢ Trial sponsors to provide a permanent point of contact for all trial participants to obtain confirmation of participation in the vaccine arm of a study

➢ Trial sponsors to consider creating a secure participant registry to facilitate access to records, including cross-sponsor regional or national registries

➢ The research community to continue to study VISR and publish systematic studies and case reports to enable clinical researchers to better anticipate, prevent, and mitigate the impact of VISR on participants

➢ Trial sponsors to inform and educate healthcare providers about VISR in the areas where sponsors are conducting clinical trials

➢ In-country health authorities to ensure that national guidelines for HIV testing identify VISR as a potential confounder for interpreting serological test results

➢ Test manufacturers to include language about the possibility of VISR interference with testing in package inserts for commercially available serological HIV tests worldwide

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants of the March 2013 meeting “Vaccine-Induced Sero-Reactivity/Sero-Positivity”, whose opinions greatly influenced the content of this article. For a complete list of participants and the meeting report, visit http://www.vaccineenterprise.org/content/timely-topic-VISP. This project has been funded in part with Federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. HHSN272200800014C. IAVI's work is made possible by generous support from many donors, including the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). A full list of IAVI donors is available at www.iavi.org.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

It has been suggested that the terms VISP and VISR could be obscure or even stigmatizing (when the word ‘positive’ is perceived as an HIV-infected status). Community consultations conducted by the Global HIV Vaccine Enterprise in US and Kenya echoed this concern. However, in a discussion organized by the Global HIV Vaccine Enterprise, representatives from ten HIV vaccine research organizations around the world agreed that VISP and VISR present the best option to maintain historical continuity in bibliographical searches in the context of research publications. New terms, such as ‘vaccine-induced antibodies’ or ‘vaccine antibody response’, should be considered for dialogue with the public. To see the full report on the consultation and existing nomenclature guide, visit: http://www.vaccineenterprise.org/content/timely-topic-VISP. In this paper, the term VISR is used to refer to this phenomenon.

References

- 1.Ackerman M, Alter G. Mapping the journey to an HIV vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(4):389–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1304437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mascola JR, Haynes BF. HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies: understanding nature's pathways. Immunol Rev. 2013;254(1):225–44. doi: 10.1111/imr.12075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Excler J-L, Robb ML, Kim JH. HIV-1 vaccines: Challenges and new perspectives. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2014;10(6) doi: 10.4161/hv.28462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haynes BF, Gilbert PB, McElrath MJ, et al. Immune-Correlates Analysis of an HIV-1 Vaccine Efficacy Trial. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(14):1275–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zolla-Pazner S, deCamp A, Gilbert PB, et al. Vaccine-induced IgG antibodies to V1V2 regions of multiple HIV-1 subtypes correlate with decreased risk of HIV-1 infection. PloS One. 2014;9(2):e87572. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karg C. Personal communication [Google Scholar]

- 7.GS HIV Combo Ag/Ab EIA | Clinical Diagnostics | Bio-Rad [Internet]. [cited 2014 Oct 15];Available from: http://www.bio-rad.com/en-us/product/retrovirus-hiv-mdash-microplate/gs-hiv-combo-ag-ab-eia

- 8.HIV Combo [Internet] [2014 Oct 15]; Available from: http://hivcombo.com/index.html.

- 9.Khurana S, Needham J, Park S, et al. Novel approach for differential diagnosis of HIV infections in the face of vaccine-generated antibodies: utility for detection of diverse HIV-1 subtypes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2006;43(3):304–12. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000242465.50947.5f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khurana S, Needham J, Mathieson B, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) vaccine trials: a novel assay for differential diagnosis of HIV infections in the face of vaccine-generated antibodies. J Virol. 2006;80(5):2092–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2092-2099.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penezina O, Krueger NX, Rodriguez-Chavez IR, et al. Performance of a redesigned HIV Selectest enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay optimized to minimize vaccine-induced seropositivity in HIV vaccine trial participants. Clin Vaccine Immunol CVI. 2014;21(3):391–8. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00748-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khurana S, Norris PJ, Busch MP, et al. HIV-Selectest enzyme immunoassay and rapid test: ability to detect seroconversion following HIV-1 infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(1):281–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01573-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.FDA-Vaccines Blood & Biologics- Development & Approval Process (Biologics) - Devices Regulated by the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research [Internet] Available from: www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/510kProcess/ucm133429.htm)

- 14.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Recomm Rep Cent Dis Control. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17. quiz CE1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karg C, Wecker M. VISP and the HVTN's Commitment to Poststudy HIV Testing [Internet] 2012 Available from: http://hvtnews.wordpress.com/2012/03/02/visp-and-the-hvtns-commitment-to-poststudy-hiv-testing/more-560.

- 16.Ackers M-L, Parekh B, Evans TG, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) seropositivity among uninfected HIV vaccine recipients. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(6):879–86. doi: 10.1086/368169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper CJ, Metch B, Dragavon J, Coombs RW, Baden LR. NIAID HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN) Vaccine-Induced Seropositivity (VISP) Task Force. Vaccine-induced HIV seropositivity/reactivity in noninfected HIV vaccine recipients. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2010;304(3):275–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt C, Fast P. Long term follow-up of Study Participants from Prophylactic HIV Clinical Trials in Africa. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2014;10(3) doi: 10.4161/hv.27559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christine Durier CD. Long-Term Persistence of Vaccine-Induced HIV Seropositivity in Healthy Volunteers. [2014 Jun 5];J AIDS Clin Res [Internet] 2014 05(02). Available from: http://omicsonline.org/open-access/longterm-persistence-ofvaccineinduced-hiv-seropositivity-in-healthy-volunteers-2155-6113.1000275.php?aid=24233.

- 20.Silbermann B, Tod M, Desaint C, et al. Short communication: Long-term persistence of vaccine-induced HIV seropositivity among healthy volunteers. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008;24(11):1445–8. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durier Long term VISP in healthy volunteers in ANRS COV1-COHVAC cohort. Poster, CROI. 2011 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22. [2012 Apr 25];Getting the Right Test for HIV [Internet] Available from: http://www.hvtn.org/visp/index.html.

- 23.Strauss RP, Sengupta S, Kegeles S, et al. Willingness to volunteer in future preventive HIV vaccine trials: issues and perspectives from three U.S. communities. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2001;26(1):63–71. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200101010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buchbinder SP, Metch B, Holte SE, Scheer S, Coletti A, Vittinghoff E. Determinants of enrollment in a preventive HIV vaccine trial: hypothetical versus actual willingness and barriers to participation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2004;36(1):604–12. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200405010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen M, Israel H, Rybczyk K, et al. Trial-Related Discrimination in HIV Vaccine Clinical Trials. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17(8):667–74. doi: 10.1089/088922201750236942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allen M, Metch B, Lau C, et al. Negative Social Impacts in Preventive HIV Vaccine Clinical Trials. Amsterdam, Netherlands: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.LOA Code of Conduct. HIV Testing Protocol. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weissner P, Lemmen K. Quick Reference Guide. Entry and residence regulations for people living with HIV 2012-2013. Deutsche AIDS-Hilfe e.V. [Internet] 2012 Available from: www.aidshilfe.de/en.

- 29.International AIDS Society (IAS), the European AIDS Treatment Group (EATG), and the Global Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS(GNP+) The Global Database on HIV related travel restrictions. [Internet] International AIDS Society (IAS); Available from: www.hivtravel.org. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berséus O, Hervig T, Seghatchian J. Military walking blood bank and the civilian blood service. Transfus Apher Sci Off J World Apher Assoc Off J Eur Soc Haemapheresis. 2012;46(3):341–2. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strandenes G, Cap AP, Cacic D, et al. Blood Far Forward--a whole blood research and training program for austere environments. Transfusion (Paris) 2013;53(Suppl 1):124S–130S. doi: 10.1111/trf.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keefer MC, Gilmour J, Hayes P, et al. A phase I double blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study of a multigenic HIV-1 adenovirus subtype 35 vector vaccine in healthy uninfected adults. PloS One. 2012;7(8):e41936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peel S. Personal communication [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eligibility Requirements [Internet]. [2014 Jun 5];Am. Red Cross. Available from: http://www.redcrossblood.org/donating-blood/eligibility-requirements.

- 35.Lally MA. Personal communication [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allen M. Personal Communication [Google Scholar]