Abstract

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are the target of many drugs prescribed for human medicine and are therefore the subject of intense study. It has been recognized that compounds called allosteric modulators can regulate GPCR activity by binding to the receptor at sites distinct from, or overlapping with, that occupied by the orthosteric ligand. The purpose of this study was to investigate the nature of the interaction between putative allosteric modulators and Ste2p, a model GPCR expressed in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae that binds the tridecapeptide mating pheromone α-factor. Biological assays demonstrated that an eleven amino acid α-factor analog and the antibiotic novobiocin were positive allosteric modulators of Ste2p. Both compounds enhanced the biological activity of α-factor, but did not compete with α-factor binding to Ste2p. To determine if novobiocin and the 11-mer shared a common allosteric binding site, a biologically-active analog of the 11-mer peptide ([Bio-DOPA]11-mer) was chemically cross-linked to Ste2p in the presence and absence of novobiocin. Immunoblots probing for the Ste2p-[Bio-DOPA]11-mer complex revealed that novobiocin markedly decreased cross-linking of the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer to the receptor, but cross-linking of the α-factor analog [Bio-DOPA]13-mer, which interacts with the orthosteric binding site of the receptor, was minimally altered. This finding suggests that both novobiocin and [Bio-DOPA]11-mer compete for an allosteric binding site on the receptor. These results indicate that Ste2p may provide an excellent model system for studying allostery in a GPCR.

Keywords: G PROTEIN-COUPLED RECEPTOR (GPCR), Ste2p, YEAST, NOVOBIOCIN, ALLOSTERY, DOPA

Introduction

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) represent the largest family of membrane proteins that sense environmental cues and send signals across the plasma membrane to initiate cellular responses [1]. This class of proteins, when mutated or inappropriately expressed, may be linked to a variety of disease states thus making them prime targets for prescribed drugs to treat ailments such as cardiovascular disease, allergies, asthma, and even some types of cancer [2]. These receptors consist of seven membrane-spanning domains, which transduce signals via activation of heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide binding proteins and/or other intracellular proteins [1, 3] Signal transduction relies on the activation of the GPCR by the binding of its cognate ligand to a specific orthosteric site of the receptor [4]. In addition, receptor activation can be modulated by ligands which bind to the receptor at non-canonical sites. These allosteric ligands bind to sites distinct from the orthosteric site on GPCRs and, depending on the specific ligand, can serve to either enhance or inhibit the biological response induced by the orthosteric ligand [5]. Allosteric modulators that inhibit orthosteric signaling are referred to as negative allosteric modulators (NAM), while those that enhance signaling by the orthosteric ligand are called positive allosteric modulators (PAM). Additionally, some allosteric ligands have the capability of not only modulating the efficiency of receptor activation, but can also activate the receptor in the absence of an orthosteric ligand [5].

While there is selective pressure to maintain the structural characteristics of the orthosteric binding site for a particular function of a GPCR, the regions of the receptor which serve as allosteric binding sites are not under this constraint. Thus, allosteric binding sites can be used to selectively modulate one specific receptor subtype over another [5–7]. Given the physiological importance of GPCRs, they are an ideal target for therapeutic agents [8, 9]. In addition, allosteric modulators have a limit on their maximal degree of enhancement or inhibition of the receptor, which also make them less prone to target related side-effects [5]. Research exploiting the utility of allosteric compounds to selectively modulate specific GPCR subclasses will promote the development of drugs targeting specific receptors with minimal side-effects.

The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been used as a model organism for GPCR research due to the robust genetic and molecular tools available to manipulate protein expression, and mutagenesis. This yeast expresses an endogenous GPCR, Ste2p, which is essential for pheromone-induced sexual conjugation of this single cell eukaryote The orthosteric ligand responsible for triggering this pathway is the 13-mer peptide α-factor (WHWLQLKPGQPMY) (Fig. 1A) [10]. Ste2p is one of only two GPCRs expressed in MATa yeast cells, thus providing a convenient and controllable system for the study of GPCR structure and function [11]. S. cerevisiae also provides a model system for the expression of certain vertebrate GPCR making findings uncovered and methods developed with Ste2p relevant to medically important targets [12, 13].

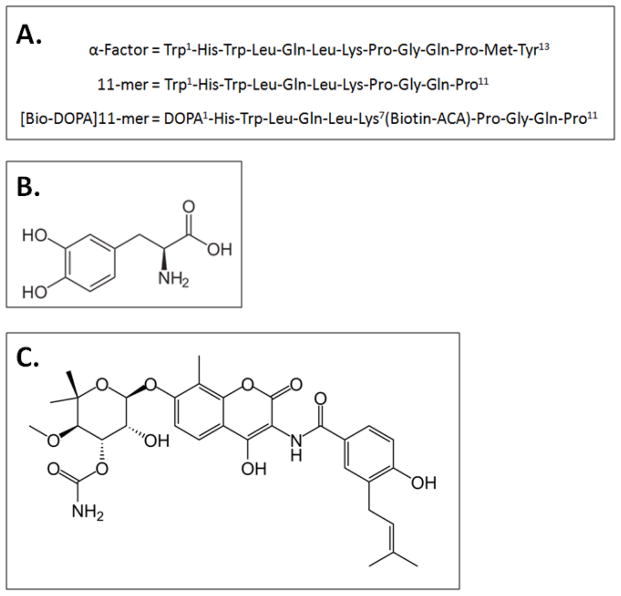

Figure 1.

A. Peptides used in this study: α-factor, 11-mer, and [Bio-DOPA]11-mer containing DOPA and biotinylaminocaproate (biotin ACA). B. Structure of L-3,4-dihydroxyphenyalanine (DOPA). C. Structure of novobiocin.

In a previous report [14] we described a modulator of Ste2p function, an 11-mer analog of α-factor lacking the C-terminal Met and Tyr residues (WHWLQLKPGQP) (Fig. 1B). This 11-mer peptide had no innate biological activity, did not compete for binding with α-factor, and did not influence the affinity of the receptor for the ligand in a wild-type yeast strain. However, this ligand did enhance the biological activity of the native ligand α-factor and was a very weak agonist in a yeast mutant that was supersensitive to the ligand. Originally, we applied the term “synergist” to this compound [14] but it more correctly fits the definition of a positive allosteric modulator, or PAM. In most circumstances, PAMs have little or no structural similarity to the orthosteric ligand. Interestingly, in this instance the 11-mer is a C-terminally truncated version of α-factor. The question we are addressing in this report is how does this peptide exert its effect: by binding to a distinct allosteric site, or by interaction at a site which overlaps the orthosteric site without competing for binding. To this end, we have synthesized an α-factor analog, [Bio-DOPA]11-mer, a novel modified 11-mer (Fig. 1A) that allowed for DOPA-mediated chemical cross-linking of the analog to the receptor. Previously we used a similar methodology to cross-link a full-length, DOPA-modified α-factor into Ste2p in order to determine the pheromone binding site in the receptor [15]. In order to detect the receptor-ligand complex, biotinylaminocaproate (biotin ACA) was tagged onto the Lys7 position of the ligand. Immunoblots containing the cross-linked Ste2p enriched samples were probed with NeutrAvidin-HRP to detect the [Bio-DOPA]α-factor bound to Ste2p [15]. Our intent in this report was to use this same technique to interrogate the interaction of the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer with the receptor.

To increase the scope of these studies, we have coupled our investigation of the 11-mer to that of novobiocin (Fig. 1C), a compound known as a coumarin antibiotic that inhibits bacterial DNA gyrase and also binds eukaryotic Hsp90 with high affinity. Previously, novobiocin, which has no structural similarity to α-factor, the orthosteric ligand (Fig. 1A), was shown to activate the Ste2p-mediated signal transduction pathway when added to a supersensitive mutant strain [16, 17]. We have determined that novobiocin had no activity in a wild-type strain of yeast, but in the presence of α-factor, novobiocin enhanced the biological response of the orthosteric ligand resulting in PAM activity. We also found that novobiocin competed with the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer for cross-linking to Ste2p, but did not compete for binding of α-factor leading us to hypothesize that these two structurally distinct compounds, novobiocin and the 11-mer derivative, may bind to the same, perhaps overlapping, allosteric site on Ste2p.

Experimental Procedures

Strains and Media

Saccharomyces cerevisiae LM102 (MATa, bar1, his4, leu4, trp1, met1, ura3, FUS1-lacZ::URA3, ste2-dl) [18] transformed with the plasmid pBEC2 was used in binding, growth arrest, and FUS1-lacZ reporter gene assays to test for biological activity. The plasmid pBEC2 encodes a Cys-less (C59S, C252S) Ste2p bearing C-terminal FLAG (FT) and His (HT) epitope tags [19]. We will refer to this particular construct as Ste2p-FT-HT in this report. The protease deficient strain BJS21 (MATa, prc1-407, prb1-1122, pep4-3, leu2, trp1, ura3-52, ste2::Kan) [20] bearing the pBEC2 plasmid was used for all DOPA cross-linking experiments. Both strains were grown in a synthetic medium lacking tryptophan (MLT) [21] to maintain selective pressure to retain the Trp-based pBEC2 plasmid.

Membrane Preparation

BJS21 cells expressing Ste2p-FT-HT receptor were grown overnight with shaking in 200 ml of MLT. Cells were harvested in a table top centrifuge, washed three times, and resuspended in a small volume of HEPES/EDTA (50 mM HEPES, 5 mM EDTA, pH 7.5). The cells were harvested by centrifugation (5,000 rpm for 30 seconds) in microcentrifuge tubes. Subsequent steps were performed at 4°C unless otherwise stated. The supernatant was removed, glass beads (0.5 mm diameter, 200 μl) and HEPES/EDTA (200 μl) added to the tube. Cells were shaken in a FastPrep-24 (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) homogenizer for one set of cycles (one minute on, two minutes off, repeated a total of three times). Cells were chilled on ice for 15 minutes and then subjected to a second set of homogenization cycles. Unbroken cells and glass beads were removed by centrifugation (2,000 rpm for 5 minutes), and the supernatant transferred to a clean microcentrifuge tube. Membranes were harvested from the supernatant by centrifugation (13,000 rpm, 30 minutes). The final membrane pellet was homogenized and resuspended in NE buffer (20 mM HEPES, 20% glycerol, 100 mM KCl, 12.5 mM EDTA, pH 9). Membrane concentration was determined using the BioRad Protein Assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA).

Synthesis and Cross-linking of [Bio-DOPA]11-mer

Synthesis of [DOPA1, K7 (BiotinACA),desM12desY13] α-factor ([Bio-DOPA]11-mer) and [DOPA1, K7 (BiotinACA)] α-factor ([Bio-DOPA] 13-mer) were completed using methodology similar to that previously described [15]. Briefly, assembly of the peptide chain and incorporation of 3, 4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) in the 11-mer peptide was conducted by automated solid-phase synthesis on a L-prolyl-2-chlorotrityl resin (0.7 mmole/mg) using standard Fmoc protocols with HBTU (N,N,N′,N′-Tetramethyl-O-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)uronium hexafluorophosphate, O-(Benzotriazol-1-yl)-(N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate)/HOBt (hydroxybenzotriazole) catalyzed single coupling reactions on an Applied Biosystems 433A automated peptide synthesizer. Fmoc-DOPA-OH was used without side-chain protection and the weight gain of the resin was 100% +/− 10%. After drying the resin was split 1:2 and the Fmoc group was cleaved from one third of the resin to give DOPA-HWLQLKPGQP-resin.

Both the free 11-mer and the α-Fmoc protected 11-mer were cleaved from the resin using of 0.75g phenol, 0.5 mL water, 0.5 mL thioanisole, 0.25 mL 1,2-ethanedithiol and 0.1 mL triisopropylsilane in 10 mL trifluoroacetic acid for 1.5h. The approximate yield of assembly and resin cleavage steps was 85% based on the initial resin loading. The crude 11-mer (DOPA-HWLQLKPGQP; 31 mg) was purified by HPLC using a C18 DeltaPak column to give 17.1 mg (55% recovery) of a homogeneous peptide with a MW of 1382.5 (calc 1382.6). The Fmoc-DOPA-HWLQLKPGQP peptide (104 mg) was purified similarly to give 33 mg (31.7% recovery) of homogeneous peptide with a MW of 1604.8 (calc. 1604.84). Biotinylaminocaproate was attached to Lys7 of the Fmoc-protected peptide (22.7 mg) in a solution phase reaction through hydroxysuccinimide-mediated amide bond formation [15] in a dimethylformamide/ sodium borate medium, which was flushed with argon, at 4°C for 1 h. The Fmoc was removed by addition of piperidine, the reaction quenched by HCl and the filtered medium was loaded on a preparative HPLC to give 18.8 mg of pure ([Bio-DOPA]11-mer; DOPA-HWLQLK(BiotinACA)PGQP, MW 1722.0 calc; 1722.1) representing a 77% yield of coupling, Fmoc removal, and purification.

The DOPA moiety was activated with periodate based on the method of Budine et al [22] for cross-linking of the peptide into Ste2p, and biotin was used for avidin-linked detection of the ligand in the receptor-ligand complex. For cross-linking of the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer into Ste2p, freshly prepared membrane samples (~4.5 mg) were adjusted to a final volume of 1 ml in NE Buffer in siliconized microcentrifuge tubes and incubated in the presence or absence of [Bio-DOPA]11-mer (85 μM) plus or minus novobiocin (5 mM or 50 mM; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 2 hr at 4 °C with end-over-end mixing. Novobiocin was freshly prepared in NE Buffer immediately before use in all experiments. For the crosslinking of [Bio-DOPA]13-mer, membranes were incubated with 10 μM of this 13-residue peptide in the presence or absence novobiocin (5 mM or 50 mM). To initiate cross-linking of DOPA, a freshly prepared sodium periodate solution (50 mM) was added to a final concentration of 2 mM, and the tubes were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min with occasional vortexing. The membranes were then harvested by centrifugation (13,000 rpm, 30 min. 4°C), resuspended in 3.0 ml solubilization buffer (TBS [50 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl], 1 mM EDTA, 2.5% Triton X-100) supplemented with protease inhibitors (phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride 1.7 ng/μl, pepstatin A 1ng/μl, and leupeptin 1ng/μl), and then incubated in a 15 ml conical tube overnight at 4°C with end-over-end mixing.

Ste2p Enrichment and Immunoblotting

Following overnight incubation, the solubilized samples were cleared by centrifugation (13,000 rpm, 30 min, 4°C). The resulting supernatant was combined with 100 μl FLAG resin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) prepared by washing with TBS (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and incubated overnight with end-over-end mixing at 4°C. Upon completion of the incubation interval, the tubes were placed on ice, and the beads allowed to settle by gravity for 15 minutes, then centrifuged for 30 seconds at 3,000 rpm in a table top centrifuge at 4°C to collect beads remaining on the sides of the tube. The supernatant was removed, and the beads washed with 1% Triton-X buffer (TBS [50 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl], 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100) followed by three washes with TBS, each time allowing the beads to settle by gravity followed by centrifugation as described. Material bound to the FLAG beads was extracted in 100 μl of non-reducing SDS sample buffer (200 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 40% glycerol) by mixing at room temperature for 5 minutes, and pelleting the beads for 30 seconds at 10,000 rpm. The supernatant was collected, and protein concentrations were measured using the detergent-compatible protein assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Samples were fractionated by gel electrophoresis (10% SDS-PAGE), and blotted onto Immobilon-P (Millipore, Billerica, MA). To probe for the FLAG epitope, blots were blocked in 5% milk in TBS and incubated overnight with FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) diluted 1:20,000 in TBS plus 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST). The FLAG blot was washed and then incubated with a goat anti-mouse HRP conjugate secondary antibody (Promega, Madison, WI) diluted 1:15,000 in TBST for three hours. To probe for biotin, blots were blocked in 3% BSA and incubated overnight with NeutrAvidin HRP conjugate (Pierce, Rockford, IL) diluted 1:10,000 dilution in TBST. Upon completion of the incubation intervals, FLAG and biotin blots were washed and incubated with West Pico chemiluminescent detection reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) for imaging on the ChemiDoc XRS photodocumentation system (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Band densities were measured using the volume tools of the Image Lab software (version 3.0 build 11, Bio-Rad, Hercules CA) and used to normalize the NeutrAvidin HRP signal (biotinylation) to the FLAG signal (total Ste2p) to control for sample to sample variation in protein concentration. The results were expressed as percent control, which was determined from the signal in the absence of novobiocin. These experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results in all cases and representative blots are presented..

Growth Arrest Assay

LM102 cells expressing Ste2p-FT-HT were grown overnight (~16 hours) at 30°C in MLT with shaking. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed three times with sterile water and adjusted to a final concentration of either 1 or 3 × 106 cells/ml. One ml of cell suspension was combined with 3.5 ml molten Noble agar (1.1%, tempered to 50°C), and the mixture overlayed onto MLT plates. For some experiments cells were combined with tempered Noble agar (1.1%) in the absence or presence of 2.2 mg of novobiocin, and the mixture overlayed onto MLT plates. Sterile filter discs impregnated with different amounts of peptide solution, as indicated for each specific experiment, were placed on the overlay and the plates incubated at 30°C for 24 to 48 hours and photographed using the BioRad ChemiDoc XRS photodocumentation system. These growth arrest assays were repeated three times with the area of the halo including the disc usually within ± 15% in each of the assays.

FUS1-lacZ Assay

FUS1-lacZ activity was determined by the method of Hoffman [23]. LM102 cells expressing or lacking Ste2p-FT-HT were grown overnight (~16 hours) at 30°C with shaking. The cells (5 ml) were harvested by centrifugation (4,000 rpm, 5 min.) and re-suspended in 1 ml of MLT. The cells were then diluted 1:20 into 5 ml of fresh MLT and cultured for 4 hours at 30°C. Cells (450 μL) were dispensed into 1.5 ml siliconized tubes, supplemented with 50 μl peptide or novobiocin solution (at the concentrations indicated for each experiment) and incubated at 30°C for 90 minutes with shaking. Upon completion of the incubation interval, 90 μl of cells was dispensed into each of 4 wells (quadruplicate each sample) of a 96 well plate. The optical density (OD600) of each sample was determined using a Synergy-4 96-well plate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc. Winooski, VT). A working solution of fluorescein di-β-galactopyranoside (FDG; Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR) was prepared by mixing equal amounts of fresh Solution A (40 μM FDG in 25 mM PIPES buffer, pH 7.2) and Solution B (0.5% Triton X-100 in 250 mM PIPES buffer, pH 7.2). The FDG working solution (20 μl) was added to each well to initiate the reaction, and the plate was gently mixed and incubated at 37°C for 90 minutes in the dark. Measurement of β-galactosidase activity was determined by measuring fluorescence (Excitation of 485 nm, Emission of 530 nm) with the Synergy-4 reader. Background fluorescence measured in the absence of cells was subtracted from resulting values, and measurements were divided by OD600 values.

Binding Assays

The saturation and competition binding assays were carried out using [3H]α-factor prepared as described [24]. LM102 cells expressing or lacking Ste2p-FT-HT receptor were grown overnight in MLT at 30°C with shaking. Cells were washed with water and resuspended in YM1i medium (5g yeast extract, 10g peptone, 10g succinic acid, 6g sodium hydroxide, 10g glucose, 0.64g sodium azide, 0.94 g potassium fluoride, 3.8g Tosyl-L-Arginine Methyl Ester (TAME), and 5g of BSA per 1 L) at a final concentration of 3 × 107 cells/mL. For the competition binding assays, cells (810 μl) were combined with 90 μl YM1i containing 50 nM 3H α-factor plus or minus 10X competitor (cold α-factor or novobiocin). The final concentration of 3H α-factor in the binding assay was 5 nM and the competitor concentrations are specified for each experiment. The cells were incubated in the binding assay mixture for 30 minutes on ice, then dispensed (4 × 200 μl) into wells of a 96-well plate. The wells were harvested using a Skatron Cell Harvester (Skatron Instruments, Sterling, VA) and radioactivity retained on the filter determined by liquid scintillation counting. Specific binding was determined by subtracting radioactivity associated with LM102 lacking Ste2-FT-HT (background) from the counts of the strain expressing the receptor (total counts). The data were analyzed by non-linear regression for single site binding using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

For the saturation binding assay, cells were resuspended in YM1i at a concentration of 3 × 107 cells/mL and dispensed into siliconized tubes (810 μL). To each tube, 90 μL of a 10X [3H]α-factor stock in the presence or absence of novobiocin was added. The final concentration of [3H]α-factor ranged from 1.5 to 50 nM, and novobiocin was present at a final concentration ranging from 10−4M to 10−8 M. The samples were incubated on ice for 30 minutes and processed as described above to determine the specific amount of radioactivity associated with each sample and subsequent data analysis. Statistical significance between Kd and Bmax values calculated at the various novobiocin concentrations was determined using GraphPad Prism6 extra sum of squares F-test (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

11-mer, [Bio-DOPA]11-mer, and novobiocin exhibit enhancement of α-factor activity in both growth arrest and FUS1-lacZ assays

The 13-residue α-factor pheromone (Fig. 1A) is the natural ligand for the pheromone receptor Ste2p. Binding of the pheromone to Ste2p initiates the signal transduction pathway resulting in growth arrest, cell morphogenesis, and gene induction in preparation for sexual conjugation of S. cerevisiae [25]. The 11-mer (Fig. 1A), a C-terminally truncated version of the α-factor, was previously reported to have no innate biological activity when added to wild-type cells expressing Ste2p, but this analog did promote an enhancement of the growth arrest in response to the natural ligand [14]. We re-tested the effect of the 11-mer on a different S. cerevisiae strain expressing a modified Ste2p receptor (Cys-less and epitope tagged) and found, similar to the previous results, that growth arrest was greatly increased when combining α-factor with the 11-mer (Fig. 2A). At a dosage of 0.1 μg/disk, α-factor produced a small ‘halo’ or zone of growth inhibition (86 ± 6 mm2, including the area of the disk), while the 11-mer (15 μg/disk) had no biological activity. In contrast, co-incubation with α-factor and 11-mer (0.1 μg and 15 μg/disk, respectively) yielded a large halo (382 ± 36 mm2) thus indicating an enhanced growth arrest in response to the presence of both peptides. Enhancement of FUS1-lacZ reporter gene activity was likewise observed when combining α-factor with 11-mer or the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer (Fig. 2B). In the absence of α-factor, the 11-mer did not stimulate reporter gene activity over control levels (Fig. 2B). Upon incubation with both α-factor (50 nM) and 11-mer (30 μM) a 2.5 fold increase in reporter gene activity was observed. Taken together, the results of the growth arrest and FUS1-lacZ reporter gene assays suggest that the 11-mer is functioning as a positive allosteric modulator of α-factor activity.

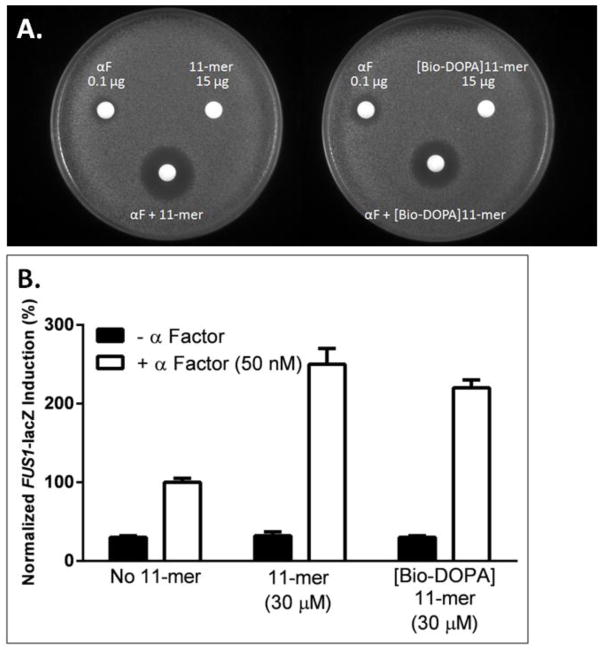

Figure 2.

A. Growth arrest assay in response to co-spotting 0.1 μg of α-factor with 15 μg of 11-mer (plate on the left), and when co-spotting 0.1 μg of α-factor with 15 μg of [Bio-DOPA]11-mer (plate on the right). The figure shown is a representative of three replicates, and halo sizes varied by less than 10%. B. Beta-galactosidase activity (FUS1-lacZ reporter gene assay) in response to 50 nM α-factor in the presence or absence of either 30 μM 11-mer or 30 μM [Bio-DOPA]11-mer. Results are reported as the mean ± standard error of three determinations normalized to the response to α-factor alone (100%).

To further explore the interaction between the 11-mer and Ste2p, we synthesized an analog of the 11-mer ([Bio-DOPA]11-mer) (Fig. 1A). Subsequent to activation by periodate, this ligand cross-links to proteins, and the cross-linked complex detected by virtue of the biotin tag on the ligand. This compound was tested for biological activity, and like the 11-mer, the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer analog has no intrinsic biological activity as assessed by growth arrest and FUS1-lacZ assay (Fig. 2A and 2B). However, the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer does promote increased growth arrest and reporter gene activity when combined with α-factor (Fig. 2A and 2B). For the growth arrest response, the combination of α-factor (0.1 μg/disk) and [Bio-DOPA]11-mer (15 μg) yielded a zone of inhibition (309 ± 27 mm2) somewhat less than that for the combination of the 11-mer and α-factor (382 ± 36 mm2, Fig. 2A. The allosteric effect of the 11-mer was not consequence of the 11-mer competing for non-specific binding of α-factor to the disc as shown previously [14]. In the FUS1-lacZ reporter gene assay (Fig. 2B), similarly to the 2.5 fold increase with the 11-mer, the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer enhanced the α-factor response by approximately 2-fold when cells were incubated with both peptides. These results suggest that modification of the peptide to include DOPA at position 1 and biotin on the ε-amine of lysine at position 7 only slightly reduced its stimulatory activity. Thus both the 11-mer and [Bio-DOPA]11-mer appear to function as positive allosteric modulators.

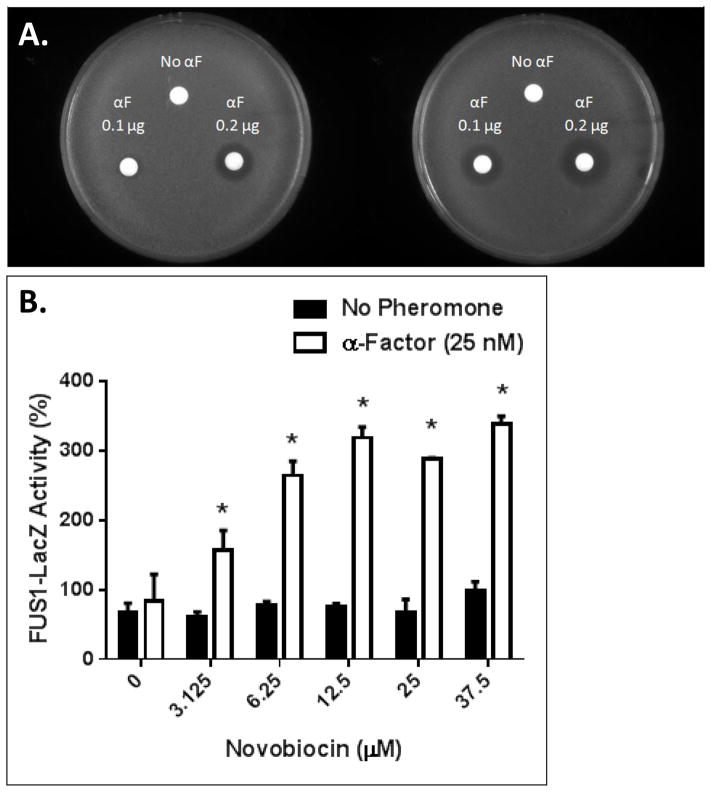

Novobiocin, an antibiotic produced by the actinomycete Streptomyces niveus, has no structural similarity to the 11-mer peptide (Fig. 1C), but in previous work it was shown to exhibit weak agonistic activity in growth arrest assays on a strain of S. cerevisiae that was supersensitive to α-factor [16, 17]. Using our yeast strain, which overexpresses Ste2p-FT-HT, but is not supersensitive to pheromone, we showed that novobiocin by itself has no measurable, intrinsic agonistic activity at the levels tested (up to 2.2 mg/disk in growth arrest assays and 37.5 μM in FUS1-lacZ assays). However, when combined with α-factor (0.1 or 0.2 μg per disk) the presence of novobiocin (2.2 mg/4.5 ml Noble agar-cell mixture) resulted in an increase in growth arrest activity (Fig. 3A). In the presence of 0.1 μg/disk α-factor, novobiocin caused an increase in halo area from 61 ± 14 mm2 to 155 ± 24 mm2. Similarly, an increase in size (192 ± 11 mm2 to 273 ± 14 mm2) was observed in the presence of 0.2 μg/disk α-factor and novobiocin. To eliminate the possibility that the novobiocin effect on halo size was due to the displacement α-factor from the paper disk rather than allosteric modulation, the experiment was repeated by spotting α-factor (10 ng) directly onto the lawn of cells containing novobiocin (2.2 mg/lawn). In the absence of the paper disk, halo area was increased in the presence of novobiocin by 45%, thus the allosteric effect was independent of the paper disk. Novobiocin by itself failed to increase reporter gene activity at concentrations up 37.5 μM (Fig. 3B). When tested at higher amounts (up to 400 μM), novobiocin likewise failed to stimulate reporter gene activity (data not shown). In contrast, in the presence of 25 nM α-factor, the FUS1-lacZ response to novobiocin exhibited a dose-dependent increase in activity up to 12.5 μM (Fig. 3B). These data indicate, that like the 11-mer and [Bio-DOPA]11-mer, novobiocin enhances the activity of α-factor in the manner consistent with that for a positive allosteric modulator.

Figure 3.

A. Growth arrest assay in response to 0.1 or 0.2 μg of α-factor in the absence (plate on the left) or presence of 2.2 mg of novobiocin in the top agar (plate on the right). The figure shown is a representative of three replicates, and halo sizes varied by less than 10%. B. Effect of novobiocin on FUS1-lacZ reporter gene activity in the absence (dark bars) and presence (gray bars) of 25 nM α-factor. The assay was repeated three times with the results normalized to response to α-factor in the absence of the novobiocin (100%) and reported as mean ± standard error. An asterisk (*) indicates that the results are significantly different (p<0.01) for activity in the presence and absence of α-factor.

Novobiocin does not compete with binding of α-factor to Ste2p or alter the pheromone’s binding affinity

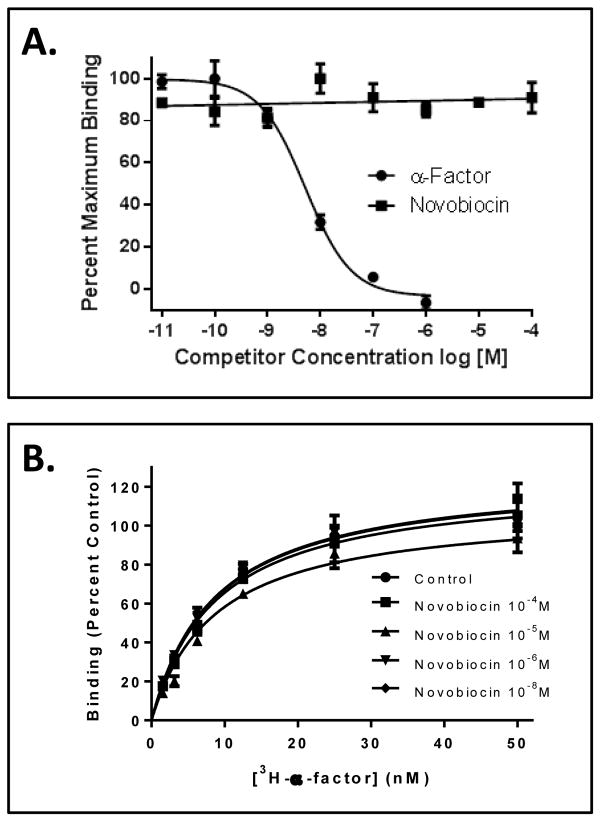

The hallmark of an allosteric modulator is that it exerts it effects via binding to a non-orthosteric site on the receptor. To determine if novobiocin might be interacting with Ste2p at an allosteric site, a competition binding assay was completed. In this assay, the ability of novobiocin (10−4M to 10−11M) to compete with 3H α-factor (5 nM) for binding to Ste2p-FT-HT was measured. The assay showed that novobiocin did not prevent α-factor binding to the receptor over an 7 log concentration range (Fig. 4A), representing a 20,000 fold molar excess at the highest concentration (0.1 mM). The control experiment demonstrated that non-radioactive α-factor had typical binding competition activity with a Ki value of 4 ± 0.1 nM (Fig. 4A). To determine if novobiocin influenced the α-factor ligand-receptor affinity, an α-factor saturation binding assay was carried out in the presence and absence of novobiocin at concentrations ranging from 10−4 M to 10−8M. Under all conditions tested, the Kd values and maximal binding activity were similar (p <0.001) for cells in the absence or presence of novobiocin (Fig. 4B). These results indicated that novobiocin does not exert its effects by influencing the binding of α-factor to Ste2p. The combination of the results showing the enhancement of α-factor-dependent activity and the lack of competition in ligand binding assays places novobiocin in the category of a positive allosteric modulator, as had been shown previously for the 11-mer [14]. The structural dissimilarity between these two compounds prompted us to determine whether these molecules acted through the same or different sites on Ste2p.

Figure 4.

A. Competition binding for [3H]α-factor (5 nM) in the presence of α-factor (10−11 M to 10−6 M) or novobiocin (10−11 M to 10−4 M). The data points (± standard error) represent quadruplicate determinations. B. [3H]α-factor saturation binding assay conducted in the absence and presence of novobiocin (10−4 to 10−8M). The data points (± standard error) represent quadruplicate determinations.

[Bio-DOPA]11-mer cross-links into Ste2p and novobiocin inhibits this cross-linking

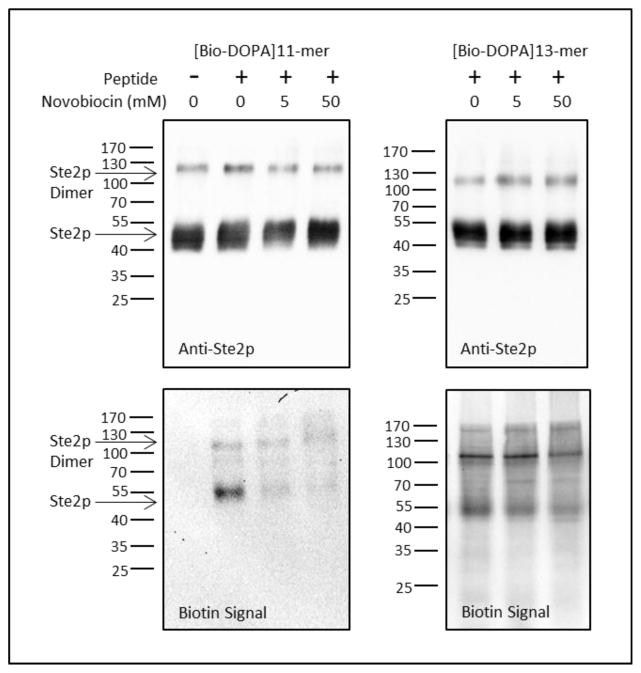

To determine whether the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer could be cross-linked into Ste2p in a manner similar to that accomplished for DOPA-labeled α-factor [15], cell membranes were incubated with the compound and cross-linking initiated by addition of 2 mM sodium periodate. Under the experimental conditions used our studies, periodate oxidation has been demonstrated to be specific for molecules containing an ortho dihydroxyphenyl ring, such as DOPA [22] and cross-linking only occurs when the oxidized DOPA intermediate is placed in close proximity to an amino acid with a suitable side chain via protein-protein interaction [26]. Approximately 2 μg of Ste2p-enriched membrane protein per lane was fractionated by SDS-PAGE and processed for immunoblotting. The western blot showed bands of similar size associated with Ste2p for membranes preparations incubated with or without [Bio-DOPA]11-mer (85 μM) and in the presence or absence of novobiocin (5 mM and 50 mM) (Fig. 5, Anti-Ste2p). Thus Ste2p-FT-HT was present in all lanes at approximately the same level. An identical blot, probed with NeutrAvidin-HRP to detect biotin incorporated through crosslinking of [Bio-DOPA]11-mer (Fig. 5, Biotin Signal) exhibited bands corresponding to the Ste2p-FT-HT monomer and dimer only for cells incubated with the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer; in the absence of ligand, no signal was detected. Incubation with the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer in the presence of 5 mM or 50 mM novobiocin reduced the labeling to 22% and 7% of the control level, respectively, for the blot in Fig. 5 (26% ± 11% and 11% ± 12% average over 3 replicate blots) suggesting that novobiocin blocked cross-linking of the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer to the receptor. The presence of 50-fold excess of α-factor did not compete with the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer in the cross-linking reaction (data not shown). Previous studies by our lab demonstrated that the 11-mer and α-factor did not compete for the same binding site [14], thus it was our hypothesis that α-factor binds to a site distinct from that for the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer, and would not inhibit cross-linking.

Figure 5.

Western blots of Ste2p enriched samples that were probed for Ste2p using an Anti-FLAG antibody (anti-Ste2p blots – top panels) and for the receptor-ligand complex using NeutrAvidin-HRP (biotin signal blots – lower panels) when incubated in the presence of [Bio-DOPA]11-mer (85 μM – panels on the left) in the presence or absence of novobiocin (5 mM and 50 Mm) or [Bio-DOPA]13-mer (10 μM – panels on the right) in the presence or absence of novobiocin (5 mM and 50 mM).

To determine whether novobiocin was being oxidized by the addition of sodium periodate, a series of 1H and 13C NMR experiments (Supplementary Material:, Figs. S1–S8) were conducted using a one-to-one stoichiometric ratio of 25 mM novobiocin to 25 mM sodium periodate. No new peaks or changes in relative peak intensities within the spectra were noted for either nuclei, which suggests that novobiocin is stable to periodate oxidation (Supplementary Material, compare Figs. S5 to S7 and S6 to S8) and is not consuming the periodate necessary to oxidize DOPA for the cross-linking reaction..

Using DL-DOPA as a model, an experiment was conducted to determine if oxidation by sodium periodate can occur in the presence of novobiocin. For this experiment, 16 mM concentrations of each of the three reagents were used. The novobiocin and periodate solution was prepared according to the procedure described in Supplementary Material. Following incubation, a stoichiometric equivalent of the 50 mM DL–DOPA solution was added. After mixing, the solution was allowed to incubate for one hour. During incubation, the mixture changed from the original clear solution to a transparent, dark brown. 1H NMR spectra were generated to monitor the reactivity of the system, and oxidation of DL-DOPA was confirmed by changes in the aromatic region, which matched those for a one-to-one mixture of 25 mM DL–DOPA and 25 mM periodate with no added novobiocin (Supplementary Material: Fig. S9–S12). In the presence of novobiocin, DOPA is still effectively oxidized by sodium periodate, therefore, the reduction in [Bio-DOPA]11-mer cross-linking to Ste2p observed under these conditions is likely not due to inhibition of the cross-linking reaction itself.

To examine whether novobiocin specifically blocked cross-linking of the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer to the receptor, we performed a cross-linking reaction using the [Bio-DOPA]13-mer, a full length α-factor which binds the orthosteric site of the receptor and retains biological activity [27] (Fig. 5). After normalization of the biotin signal (cross-linked product) to the anti-Ste2p signal (total receptor present), 5 mM novobiocin did not inhibit the cross-linking of the [Bio-DOPA]13-mer (136 % of control for the blot presented in Fig. 5, 118% ± 25% average over 3 replicate blots). In the presence of 50 mM novobiocin, cross-linking was decreased slightly to 84% of control levels as determined by normalization (92% ± 17% average over 3 replicate blots). In contrast, cross-linking of the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer was reduced to 7% of the control level in the presence of 50 mM novobiocin.. These data further support our hypothesis that the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer and novobiocin do not interact with the orthosteric site of Ste2p in the same manner as the orthosteric ligand α-factor.

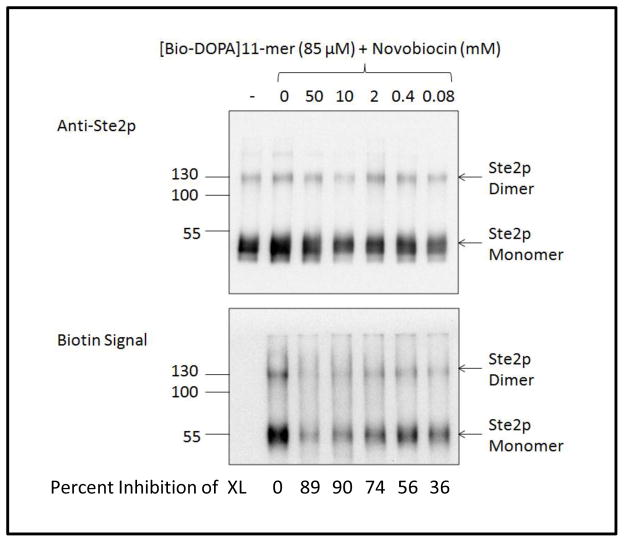

To determine if the effect of novobiocin on [Bio-DOPA]11-mer cross-linking was dose-dependent, cell membranes were incubated with [Bio-DOPA]11-mer in the presence of increasing concentrations of novobiocin, ranging from 0.08 mM to 50 mM, (Fig. 6A). Cross-linking of the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer to Ste2p-FT-HT increased as the concentration of novobiocin decreased (Biotin Signal, lower panel). The FLAG Blot indicated that there was a slight variation of Ste2p-FT-HT present in each sample (Anti-Ste2p, upper panel), thus the quantitation of band densities was normalized by calculating the ratio of biotin signal band density to that of anti-Ste2p signal band density. Novobiocin inhibits the cross-linking of the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer in a dose-dependent manner, with maximal inhibition (~ 90% reduction) occurring between 10 and 50 mM novobiocin. Even at 5:1 and 1:1 molar ratios of novobiocin to the crosslinker, 55% and 35% inhibition of crosslinking, respectively, was observed. The potency of novobiocin as an allosteric modulator is weak, but the effect is reproducible, suggesting that the two compounds may be interacting with the same site on the receptor.

Figure 6.

A. Western blots of FLAG enriched samples probed for Ste2p (upper blot, Anti-Ste2p) and for the receptor-ligand complex (lower blot, Biotin Signal). Membranes were treated with 85 μM [Bio-DOPA]11-mer in the presence or absence of novobiocin (0.08 mM to 50 mM). The values under each lane (Percent Inhibition of XL) were calculated by normalizing the Biotin Signal to the Anti-Ste2p signal and expressing the normalized value as percent reduction of cross-linking relative to that in the absence of novobiocin.

Discussion

Previously, two laboratories showed that the coumarin antibiotic, novobiocin, acts as a weak agonist of Ste2p, a tridecapeptide pheromone receptor, in a supersensitive yeast strain [16, 17]. We now present evidence that novobiocin can act as a positive allosteric modulator for Ste2p in a strain that is not supersensitive to the natural ligand. Likewise, the C-terminally truncated analogs of α-factor, the11-mer and [Bio-DOPA]11-mer, were shown to enhance α-factor’s activation of the receptor in both growth arrest and reporter gene assays, at concentrations where neither alone had a measureable effect; these peptides may be considered to be positive allosteric modulators as well.

Based on saturation and competition binding assays presented here with novobiocin and in a prior publication from our lab with the 11-mer [14] it appears that these compounds interact with a site on the receptor that is distinct from the orthosteric binding site. Specifically, neither the 11-mer [14] nor novobiocin (Fig, 4) competed with binding of α-factor to Ste2p. The results from the cross-linking experiments (Fig 5 and Fig 6) show that despite no structural similarity between novobiocin and the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer, both compounds appear to be competing for interaction at the same site on the receptor. Additionally, when present at a 1000-fold molar excess novobiocin did not prevent the cross-linking of α-factor analog, the [Bio-DOPA]13-mer (Fig. 5) which binds to the orthosteric site of the receptor [27], whereas .~120-fold molar excess of novobiocin led to a 90% reduction in the crosslinking of the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer (Fig. 6). This latter experiment also provides evidence that novobiocin does not work by reacting with periodate to prevent activation of the dihydroxyphenyl moiety. Our NMR results (Supplementary Material) indicate that novobiocin remains intact upon extended incubation (1 hour) with sodium periodate under the same conditions (i.e. buffer and temperature) used for the cross-linking reaction. However, the possibility remains that a minor degradation product or other contaminant present in the periodate-treated novobiocin mixture, which was not detected by NMR, might influence the cross-linking of the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer or [Bio-DOPA] 13-mer to the receptor. Clearly at 5 mM, this is not the case: novobiocin did not inhibit the cross-linking of the [Bio-DOPA] 13-mer, but did reduce markedly the cross-linking of the [Bio-DOPA] 11-mer. We did observe a slight decrease in cross-linking of the [Bio-DOPA] 13-mer in the presence of 50 mM novobiocin (to 84% of control level), but it was not as marked as the decrease in cross-linking observed for the 11-mer (to 7% of control level). Although visualization of the blot in Fig. 5 suggests that the decrease in cross-linking of the [Bio-DOPA]13-mer at 50 mM novobiocin is greater, quantitation of the band densities using Image Lab software showed only a minimal drop in cross-linking. It is possible that at 50mM novobiocin interaction of this allosteric modulator, or some associated contaminant, with the receptor could alter the receptor conformation to influence binding of the [Bio-DOPA]13-mer at the orthosteric site.

Since novobiocin clearly acts at a site that is different from the α-factor binding site, it is reasonable to conclude that [Bio-DOPA]11-mer also acts at this allosteric site. It is possible, however, that novobiocin interacts with a second allosteric site, and binding to this site induces a conformational change in the receptor that inhibits the cross-linking of the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer compound.

Another possibility is that the positive allosteric modulation observed in this study is mediated through one protomer of a receptor homodimer or a higher-ordered oligomeric complex. This type of modulation has been observed for a variety of GPCR constructs exhibiting negative cooperativity across receptor homodimers, but no examples of positive allosteric modulation have been clearly demonstrated [28]. A recent study demonstrated that binding of a bitopic allosteric modulator of the dopamine D2 receptor simultaneously to the orthosteric site and to a secondary binding pocket of one protomer imparted a negative allosteric effect to the orthosteric site of a second protomer[29]. Interestingly, α-factor binds to the receptor as a bitopic ligand; our model predicts that the N-terminus of the peptide interacts with receptor TM5–TM6 and is important for receptor activation, while the C-terminus interacts with TM1 and is important for receptor binding [27]. It is possible that the 11-mer or novobiocin bind to one protomer of a receptor dimer inducing a conformational change that causes α-factor to be active at lower concentrations.

As expected, α-factor did not inhibit cross-linking of [Bio-DOPA]11-mer as predicted by the lack of competition between the11-mer and α-factor for binding [14], further supporting our hypothesis that these ligands are binding at different sites on the receptor. However, the 11-mer itself did not inhibit cross-linking of [Bio-DOPA]11-mer to Ste2p (data not shown). One possibility for this anomalous result is that the experimental protocol required to obtain crosslinking (30 minute reaction; see Materials and Methods) favors covalent over non-coavalent interactions. Thus, once the [Bio-DOPA]11-mer is covalently cross-linked to Ste2p, competition by free 11-mer can no longer occur despite the fact that the 11-mer concentration of free was greater than that of the cross-linking ligand. Attempts to carry out the cross-linking at shorter time periods did not yield enough cross-linked product for detection on the western blots.

The 11-mer presents an interesting example of an allosteric modulator in that it is structurally very similar to the orthosteric ligand, α-factor. In most cases, allosteric modulators are structurally unrelated to the endogenous ligand and bind to a site that is distinct from that of the orthosteric site. However, there are accounts of allosteric enhancers that appear to overlap with residues in the orthosteric binding site [30–32]. Previous experiments have created a model depicting α-factor activating Ste2p in a two-step interaction. The C-terminal tail of the peptide binds to the receptor, then orients itself by bending through the Pro-Gly residues, and activates Ste2p by interaction with the peptide’s N-terminus [33]. Therefore, it seems likely that the N-terminus of the 11-mer, a structural analog of α-factor, may partially overlap with the orthosteric ligand’s activation site, but not the binding site. The exact interactions involved in 11-mer binding require experiments to identify the DOPA cross-linking site between Ste2p and [Bio-DOPA]11-mer. These are currently underway.

There are three theories [32] that offer possible explanations as to how allosteric modulators can overlap in binding with the orthosteric modulator: (1)Allosteric compounds may be able to overlap with the orthosteric sites when binding alone, but exploit a different subsite from the orthosteric sites when in the presence of the orthosteric ligand, (2) allosteric enhancers and orthosteric ligands may bind the receptor at different points in time depending on the receptor’s current ligand-preferring conformation, and (3) the allosteric and orthosteric modulators could be binding to separate monomeric forms of the receptor that ultimately form a dimer, one of which is bound to the orthosteric ligand while the other is bound to the allosteric modulator. At the present time, we cannot distinguish among these models by our data at hand.

In summary, we have found two structurally diverse molecules that act as positive allosteric modulators for the activation of Ste2p by the mating pheromone α-factor. To the best of our knowledge, these molecules represent the first allosteric ligands identified for a Class D (fungal mating pheromone receptors) GPCR. Furthermore, the yeast system described in this report could be readily adapted for use as a high-throughput screen to identify allosteric modulators for mammalian receptors expressed heterologously in yeast cells. Many mammalian receptors have been successfully expressed in yeast, and coupled to the endogenous yeast signaling pathway either directly or by co-expression of the appropriate cognate mammalian G protein [34, 35]. The genetic and molecular tools available for the manipulaton of protein expression in yeast provide an excellent model system for the characterization of receptor pharmacology. Further investigation of these interesting findings may reveal novel means to regulate GPCR function for both yeast and mammalian receptor.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Positive allostery is demonstrated for the G protein-coupled receptor Ste2p

An eleven amino acid α-factor analog is a positive allosteric modulator of Ste2p

Novobiocin is a positive allosteric modulator of Ste2p

[Bio-DOPA]11-mer) was chemically cross-linked to Ste2p

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants GM-22087 and GM-112496 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, NIH. We thank Sarah Kauffman for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pierce KL, Premont RT, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:639–650. doi: 10.1038/nrm908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Insel PA, Tang CM, Hahntow I, Michel MC. Impact of GPCRs in clinical medicine: monogenic diseases, genetic variants and drug targets. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:994–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roux BT, Cottrell GS. G protein-coupled receptors: what a difference a ‘partner’ makes. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:1112–1142. doi: 10.3390/ijms15011112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamal M, Jockers R. Bitopic ligands: all-in-one orthosteric and allosteric. F1000 Biol Rep. 2009;1:77. doi: 10.3410/B1-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Congreve M, Langmead CJ, Mason JS, Marshall FH. Progress in Structure Based Drug Design for G Protein-Coupled Receptors. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2011;54:4283–4311. doi: 10.1021/jm200371q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christopoulos A, May LT, Avlani VA, Sexton PM. G-protein-coupled receptor allosterism: the promise and the problem(s) Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:873–877. doi: 10.1042/BST0320873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flor PJ, Acher FC. Orthosteric versus allosteric GPCR activation: the great challenge of group-III mGluRs. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;84:414–424. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wise A, Gearing K, Rees S. Target validation of G-protein coupled receptors. Drug Discov Today. 2002;7:235–246. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(01)02131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giguere PM, Kroeze WK, Roth BL. Tuning up the right signal: chemical and genetic approaches to study GPCR functions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;27:51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka T, Kita H, Murakami T, Narita K. Purification and amino acid sequence of mating factor from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biochem. 1977;82:1681–1687. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a131864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Versele M, Lemaire K, Thevelein JM. Sex and sugar in yeast: two distinct GPCR systems. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:574–579. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price LA, Kajkowski EM, Hadcock JR, Ozenberger BA, Pausch MH. Functional coupling of a mammalian somatostatin receptor to the yeast pheromone response pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6188–6195. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ladds G, Goddard A, Davey J. Functional analysis of heterologous GPCR signalling pathways in yeast. Trends Biotechnol. 2005;23:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eriotou-Bargiota E, Xue CB, Naider F, Becker JM. Antagonistic and synergistic peptide analogues of the tridecapeptide mating pheromone of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry. 1992;31:551–557. doi: 10.1021/bi00117a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Umanah GK, Son C, Ding F, Naider F, Becker JM. Cross-linking of a DOPA-containing peptide ligand into its G protein-coupled receptor. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2033–2044. doi: 10.1021/bi802061z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pocklington MJ, Orr E. Novobiocin activates the mating response in yeast through the α-pheromone receptor, Ste2p. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1994;1224:401–412. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(94)90275-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin JC, Duell K, Konopka JB. A microdomain formed by the extracellular ends of the transmembrane domains promotes activation of the G protein-coupled alpha-factor receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:2041–2051. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.5.2041-2051.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sen M, Marsh L. Noncontiguous domains of the alpha-factor receptor of yeasts confer ligand specificity. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:968–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akal-Strader A, Khare S, Xu D, Naider F, Becker JM. Residues in the first extracellular loop of a G protein-coupled receptor play a role in signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30581–30590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204089200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Son CD, Sargsyan H, Naider F, Becker JM. Identification of ligand binding regions of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae alpha-factor pheromone receptor by photoaffinity cross-linking. Biochemistry. 2004;43:13193–13203. doi: 10.1021/bi0496889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sherman F, Fink GR, Lawrence CW. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burdine L, Gillette TG, Lin HJ, Kodadek T. Periodate-triggered cross-linking of DOPA-containing peptide-protein complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:11442–11443. doi: 10.1021/ja045982c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffman GA, Garrison TR, Dohlman HG. Analysis of RGS proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 2002;344:617–631. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)44744-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu S, Henry LK, Lee BK, Wang SH, Arshava B, Becker JM, Naider F. Position 13 analogs of the tridecapeptide mating pheromone from Saccharomyces cerevisiae: design of an iodinatable ligand for receptor binding. J Pept Res. 2000;56:24–34. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2000.00730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merlini L, Dudin O, Martin SG. Mate and fuse: how yeast cells do it. Open Biol. 2013;3:130008. doi: 10.1098/rsob.130008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu B, Burdine L, Kodadek T. Chemistry of periodate-mediated cross-linking of 3,4-dihydroxylphenylalanine-containing molecules to proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15228–15235. doi: 10.1021/ja065794h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Umanah GK, Huang L, Ding FX, Arshava B, Farley AR, Link AJ, Naider F, Becker JM. Identification of residue-to-residue contact between a peptide ligand and its G protein-coupled receptor using periodate-mediated dihydroxyphenylalanine cross-linking and mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:39425–39436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.149500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferre S, Casado V, Devi LA, Filizola M, Jockers R, Lohse MJ, Milligan G, Pin JP, Guitart X. G protein-coupled receptor oligomerization revisited: functional and pharmacological perspectives. Pharmacol Rev. 2014;66:413–434. doi: 10.1124/pr.113.008052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lane JR, Donthamsetti P, Shonberg J, Draper-Joyce CJ, Dentry S, Michino M, Shi L, Lopez L, Scammells PJ, Capuano B, Sexton PM, Javitch JA, Christopoulos A. A new mechanism of allostery in a G protein-coupled receptor dimer. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:745–752. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu H, Wang C, Gregory KJ, Han GW, Cho HP, Xia Y, Niswender CM, Katritch V, Meiler J, Cherezov V, Conn PJ, Stevens RC. Structure of a Class C GPCR Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor 1 Bound to an Allosteric Modulator. Science. 2014 doi: 10.1126/science.1249489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao ZG, Kim SK, Gross AS, Chen A, Blaustein JB, Jacobson KA. Identification of essential residues involved in the allosteric modulation of the human A(3) adenosine receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:1021–1031. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.5.1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwartz TW, Holst B. Allosteric enhancers, allosteric agonists and ago-allosteric modulators: where do they bind and how do they act? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naider F, Becker JM. The alpha-factor mating pheromone of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a model for studying the interaction of peptide hormones and G protein-coupled receptors. Peptides. 2004;25:1441–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2003.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minic J, Sautel M, Salesse R, Pajot-Augy E. Yeast System as a Screening Tool for Pharmacological Assessment of G Protein Coupled Receptors. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2005;12:961–969. doi: 10.2174/0929867053507261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dowell SJ, Brown AJ. Yeast assays for G protein-coupled receptors. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;552:213–229. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-317-6_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.