Abstract

Purpose

Pharmacoepidemiologic studies of acute effects of episodic exposures often must control for many time-dependent confounders. Marginal structural models permit this and provide unbiased estimates when confounders are on the causal pathway. However, if causal pathway confounding is minimal, analyses with time-dependent propensity scores, calculated for time-periods defined by individual drug prescriptions, may have better efficiency. We justify time-dependent propensity scores and compare the performance of these methods in a case study from a previous investigation of the risk of medication toxicity death in current users of propoxyphene and hydrocodone, with both substantial time-dependent confounding and a large number of covariates.

Methods

The cohort included Tennessee Medicaid enrollees who filled a qualifying study opioid prescription between 1992 and 2007. We identified 22 time-dependent covariates that accounted for most of the confounding in the original study. We compared analyses with all covariates in the regression model with those based on time-dependent propensity scores and those from marginal structural models.

Results

We identified 489,008 persons with 1,771,295 propoxyphene and 4,088,754 hydrocodone prescriptions. The unadjusted HR (propoxyphene:hydrocodone) was 0.70 (95% CI, 0.46–1.07). Estimates from inclusion of all covariates in the model, time-dependent propensity score analysis with inverse probability of treatment weighting, and marginal structural models were 1.63 (1.04–2.57), 1.65 (1.01–2.72), and 1.64 (0.83–3.27), respectively. Findings varied little with use of alternative propensity score methods, time origin, or techniques for marginal structural model estimation.

Conclusions

Time-dependent propensity scores may be useful for pharmacoepidemiologic studies with time-varying exposures when causal pathway confounding is limited.

Pharmacoepidemiologic studies of the acute effects of medications taken episodically require calculation of endpoint occurrence during periods of active drug use, or current use.1–5 To control for confounding, the study must account for covariate changes over time because their baseline values may not adequately capture medication use and other patient characteristics at the time of endpoint occurrence. Epidemiologists frequently manage such potential confounding by including time-dependent covariates in a regression analysis. However, there are two important potential limitations of this approach.

First, traditional regression methods do not work well when the number of covariates is large relative to the number of endpoints. Second, the exposure may affect confounders, which occurs for variables that mediate an effect, or are on the “causal pathway”. For example, in HIV studies, CD4 counts are likely to be both a time-dependent confounder and altered by antiretroviral therapy, hence lying on the causal pathway between medication use and AIDS or its complications. When this occurs, standard methods to control for time-dependent confounders, such as regression analysis, produce biased estimates of the exposure effect.6

Marginal structural models, a generalization of inverse probability of treatment (IPT) weighting,7–9 can provide unbiased estimates when the number of endpoints is limited or there are time-dependent causal pathway confounders.6;10–12 For this reason, many consider them as the default analysis for time-dependent confounders. However, marginal structural model analyses may be inefficient. They divide follow-up into discrete time intervals and calculate a weight that is a product with terms for the current and all preceding intervals. As the number of intervals increases, the weights can take on extreme values, affecting the stability and precision of exposure effect estimates. Although stabilization and truncation of weights can improve efficiency,13 there is limited theory to guide their use.

If causal pathway confounding is absent or limited, time-dependent propensity scores may provide another approach for management of time-dependent confounding. They are a natural extension of the propensity score methods7–9 commonly employed for analyses with large numbers of covariates. Although time-dependent propensity scores have occasionally been used,4;14 little is known regarding their rationale and performance.

We address this question in the context of a prior investigation of the safety of propoxyphene,5 a low-potency opioid analgesic withdrawn from the market because of concerns regarding fatality in overdose15;16 and adverse cardiovascular effects.17–19 This example is characteristic of studies for which time-dependent propensity scores would be useful: an episodic exposure with risk linked to current drug use and substantial confounding by a large number of time-dependent covariates, but with little of this confounding thought to be due to factors on the causal pathway.

Here we present a brief theoretical rationale for the use of time-dependent propensity scores. We compare the time-dependent propensity score analyses to those with individual time-dependent covariates and to analyses from corresponding marginal structural models.

Methods

1. Time-Dependent Propensity Score

a. Setting

Following standard notation12 we consider a scenario with treatment (exposure) variable A, outcome (endpoint) Y, and covariates (confounders) L (Figure 1)*. For every possible treatment history ā, is the potential (possibly counterfactual) outcome that would have occurred had a subject received treatment history ā.

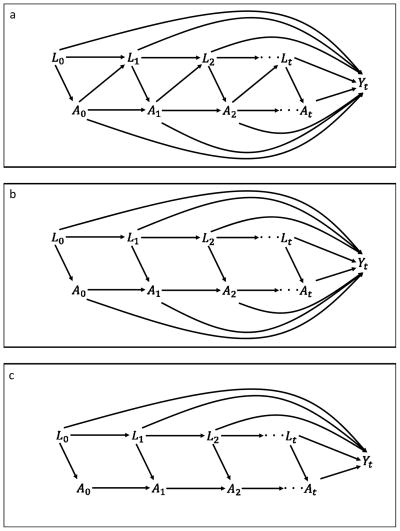

Figure 1.

Causal diagram for various time-dependent confounding scenarios. A is the treatment variable, L the covariates, and Y is the outcome. Three scenarios are presented a) most general case with causal pathway confounding in which the treatment can affect the future values of the covariates; b) no causal pathway confounding but past treatments can affect the outcome independent of At, and c) the entire causal effect of the treatment is mediated by At.

b. Justification: Conditional estimates

For an analysis with time-invariant covariates, if there is no unmeasured confounding, then for every possible a

the conditional exchangeability (also known as strongly ignorable treatment assignment or no unmeasured confounding) assumption. Intuitively, treatment assignment contains no information with regard to the outcome beyond that in the covariates. Thus, conditioning on L consistently estimates the conditional treatment effect. For binary treatments, the propensity score is

Then

so long as 0 < p(L) < 1 (the positivity assumption),8 and thus conditioning on the propensity score also will consistently estimate the conditional treatment effect.

In the time-dependent covariate setting, the conditional exchangeability assumption is:

It is well known that if there is causal pathway confounding (treatment at time t − 1 affects the covariates at time t [Figure 1-a]) then conditioning on the treatment and covariate histories does not consistently estimate conditional treatment effects.12 To do so, one must further assume that treatment does not affect future covariate values (Figure 1-b).

Generalizing the time-invariant result and assuming conditional exchangeability, positivity, and no causal pathway confounding:

where p(Āt − 1, L̄t) is the time-dependent propensity score. That is, if conditioning on the time-dependent prior treatment and covariates produces consistent conditional estimates, then, given positivity, so does conditioning on the time-dependent propensity score. The Appendix (§1) illustrates this reasoning for the specific case of the piecewise exponential distribution.

c. Justification: Marginal estimates

Marginal structural models can consistently estimate the marginal effect of At in the most general case in which Yt is influenced by the entire treatment and covariate history and the covariates are affected by prior treatment (Figure 1-a).6;12 Absent causal pathway confounding (Figure 1-b), we can obtain consistent conditional estimates as described above (§1-a). As shown in the Appendix (§2), the time-dependent propensity score IPT-weighted mean estimates the marginal mean of potential outcome whereas the mean calculated with marginal structural model weights estimates that for potential outcome . Even in the absence of causal pathway confounding, these are not necessarily equal. However, if we further assume that the entire effect of the treatment is mediated by At (Figure 1-c), the marginal mean of potential outcome is equal to that for . Thus, a time-dependent propensity score analysis with IPT weights and a marginal structural model will estimate the same marginal treatment effect (Appendix §2).

d. Censoring

Many pharmacoepidemiologic studies consider a time-to-event outcome with right censoring. To consistently estimate treatment effects, the time-to-event and censoring variables must be independent, conditional on the treatment and covariates. Thus, to condition on propensity scores, even in the time-invariant case, such independence must be present when the covariates are replaced by the propensity score. For IPT weighting, independence must hold in the pseudo population created by the weighting.

e. Time periods

Studies with time-dependent covariates require definition of the minimum period into which time is divided. In many automated database studies, this is the person-day, given that the date for medical care encounters typically is available. This may be inappropriate for time-dependent propensity scores. The positivity assumption requires that for every person and time-period combination, the probability of either treatment be non-zero†. However, when treatment is determined from prescriptions, it cannot change throughout the interval defined by the prescription, requiring a fixed propensity score during this interval, even though other covariates might change. Thus, the prescription interval is a natural time period for the analysis.

f. Time origin

Time-to-event analyses with right-censored data require definition of a time origin.11 The analysis risk sets consist of all persons alive and uncensored at a time relative to that origin. The time variable typically corresponds to a study subject’s time on followup, or a person-relative time origin. However, for many pharmacoepidemiologic studies, a time variable that begins with the prescription, or prescription-relative time origin, may be appropriate.11 The risk set for day one includes day one for all study prescriptions and so on. This time origin best reflects a hazard that varies according to time since the filling of the most recent prescription, which may better represent patient risk for episodically used medications with no carry-over effect.

2. Propoxyphene Example

a. Prior study

We conducted a cohort study of Tennessee Medicaid enrollees between the ages of 30 and 74 and found that current users of propoxyphene had greater risk of death from medication toxicity than did current users of hydrocodone, another widely used low-potency opioid analgesic.5 Cohort members had a highly variable number of periods of current use of study drugs, often separated by intervals of non-use. Risk for death from medication toxicity was most plausibly altered by the drugs only during these periods. Because such risk was affected by numerous factors such as patient frailty that in turn were strongly associated with study opioid use, the analysis ultimately included 206 covariates, many of which were likely to change during followup. We hypothesized that causal pathway confounding was minimal, given that the effects of both study opioids are thought to be acute and it was unlikely, although certainly not impossible, that these materially affected future levels of key covariates. However, given the number of medication toxicity deaths, all covariates could not be included in the regression models. Thus, we managed confounding by propensity-score matching propoxyphene and hydrocodone prescriptions.

b. Present study: Cohort and followup

The present study included the full cohort from which the matched cohort for the prior study was selected, with minor changes in drug exposure definition (Appendix §3) to facilitate the marginal structural model analyses. A cohort member’s followup consisted of a series of time periods corresponding to the current use of study opioids implied by study prescriptions (Figure 2). Other person-time was not considered, which assumes that periods of time off study opioids did not affect the risk of medication toxicity death.5

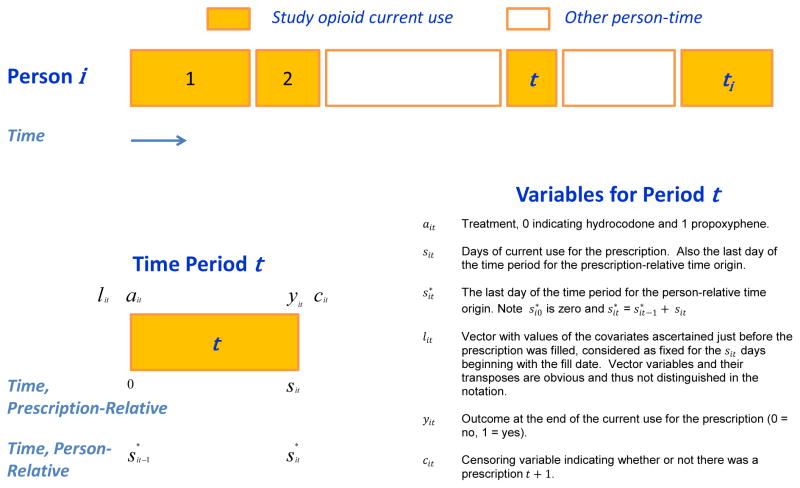

Figure 2.

Study time periods and variables. Followup is depicted for a single cohort member, person i, who has ti study opioid prescriptions, each represented by a colored block. The numbers within the blocks denote the time periods, which are half open--e.g., (0, sit], may be of different lengths and separated by intervals of non-use of study opioids, which are not considered in the analysis. The variables for a single time period (denoted by t) are shown, along with the corresponding notation.

c. Present study: covariates

The present analyses included a subset of 22 of the original 206 covariates (Appendix Table 1) that were strongly related to the risk of medication toxicity death and accounted for most of the confounding. All covariates were defined for an interval (generally 365 days) just preceding the prescription.

3. Analyses

a. Time-dependent propensity score calculation

The propensity score, the probability that prescription t for subject i is for propoxyphene (ait = 1), given the covariates (lit), was estimated from the logistic regression model‡

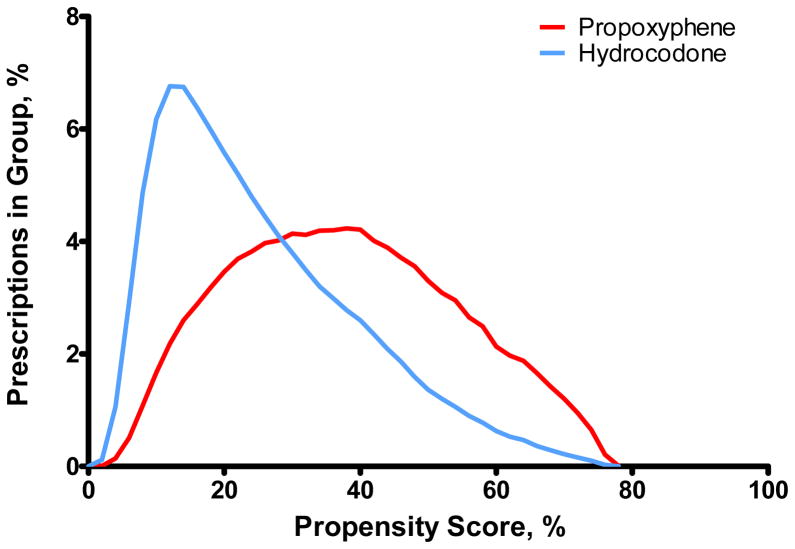

with the prescription as the unit of analysis. The distributions of the propensity score in the hydrocodone and propoxyphene groups (Figure 3) overlapped (range: 0.02 to 0.79). We calculated time-dependent stabilized IPT weights20 from the propensity score as:

where the numerator was estimated as the marginal frequency of the treatment group.

Figure 3.

Distribution of the propensity score in the propoxyphene and hydrocodone groups.

b. Prescription-relative time origin analyses

In the prescription-relative analyses (Models 1–5), the unit of analysis is the prescription (each prescription considered as an individual observation), which is equivalent to a prescription-relative time origin.11 We assumed a proportional hazards model for the risk of medication toxicity death during the period of current use defined by the prescription (Figure 2, sit days). Thus, for subject i, prescription t the hazard of medication toxicity death on day s in (0, sit] given study opioid ait and covariates lit was

with

λ0(s) the baseline hazard;

β1 log of the hazard ratio (HR) for current use of propoxyphene versus hydrocodone§;

β2 vector of log HRs for the covariates.

The univariate analysis (Model 1) included only a term for ait; the analysis with individual covariates (Model 2) also included terms for lit. The propensity-score-weighted analysis (Model 3) included only ait and was fit with IPT weights . The propensity score stratified analysis (Model 4) modeled the hazard of a medication death for a prescription with treatment ait in stratum m as

with a common β1 across strata estimated by maximum partial likelihood (see Allison21 p. 180). For propensity score regression modeling (Model 5), the model included the treatment and lit was replaced with indicator variables for propensity score deciles. The weighted analysis used robust variance estimation because a single time period could be included multiple times.21;22 This was unnecessary for the other analyses because the time periods for an individual did not overlap and each person had at most one outcome (see Westreich et al11 and Allison21 pp. 246–247).

c. Person-relative time origin analyses

In the person-relative analyses (Models 6–10, which correspond to Models 1–5 above) the time origin was the fill date of the first study prescription and the time variable corresponded to cumulative days of drug treatment (Figure 2). For example, a person with two prescriptions, each with 15 days of supply would have a total of 30 days of followup and the time variable would be included in the interval (0,30].

Thus, for person i and day s* in (0, ] during the entire period of followup (Figure 2), we assumed

where t is the time period including day s* and ait and lit indicate the respective time-dependent values of the treatment and covariates for period t. The analyses were as defined for the corresponding prescription-relative time origin analyses, except that the risk sets differed and the propensity score and related variables were time-dependent.

d. Marginal structural models

For these analyses (Models 11–14), we modeled the hazard for person i on day s of followup (s* in (0, ], Figure 2) as

The model was fit with time-dependent weights wit calculated for each prescription fill (Appendix, §4). These inverse probability of treatment and censoring (IPTC) weights informally represent the time-dependent probability of the observed treatment and censoring history.6;10–12 The outcome model included the baseline covariates because the IPTC weights were stabilized by inclusion of these covariates in the numerator model for the weights (Appendix §4 and Daniel et al12, §4.2.2–§4.2.4) to reduce variability. 6;10–12;23 However, the estimates are no longer marginal, but rather conditional on baseline covariates. Given the wide range of the IPTC weights (Appendix Table 2), these were truncated at the 1st and 99th percentiles (Models 11,13,14) and at the 5th and 95th percentiles in a sensitivity analysis (Model 12).

We estimated β1 from proportional hazards with time-dependent weights (Models 11,12).23 We also included sensitivity analyses that used a common discrete time approximation methods6;10–12;21;24 appropriate for time periods with either variable (Model 13) or fixed (Model 14) length (Appendix §5).

e. Statistical software

All analyses were performed with SAS 9.2. The analysis programs are included in the Appendix (§6).

Results

Cohort Characteristics

The study cohort included 489,008 persons with 1,771,295 qualifying propoxyphene and 4,088,754 hydrocodone prescriptions. At the time of the prescription fill, cohort members with hydrocodone prescriptions had markedly different characteristics than did those with propoxyphene prescriptions (Table 1). Hydrocodone was more likely to be prescribed to males, younger patients, and during a later calendar year. These patients were also more likely to be taking psychoactive medications, particularly higher doses of benzodiazepines, and to have had prior medical care indicating an injury. After IPT weighting, the characteristics were highly comparable (Table 1), which suggests the propensity score was properly formulated.7;8

Table 1.

Study covariates at the time of the prescription fill. Unless otherwise specified, all values are percentages. Covariates describing medical care reflect that received during the 365 days just preceding the prescription fill, unless otherwise stated. IPT denotes inverse probability of treatment.

| Unweighted | IPT Weighted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrocodone | Propoxyphene | Hydrocodone | Propoxyphene | |

| N of prescriptions* | 4,088,754 | 1,771,295 | - | - |

| Age, mean | 47.9 | 52.5 | 49.3 | 49.2 |

| Calendar year, mean | 2001.8 | 1999.6 | 2001.1 | 2000.9 |

| Sex, female | 66.0% | 73.5% | 68.3% | 68.4% |

| Residence, standard metropolitan statistical area | 48.4% | 47.1% | 48.0% | 48.3% |

| Medicaid enrollment uninsured | 23.7% | 22.6% | 23.4% | 23.7% |

| Benzodiazepine use | ||||

| None in past year | 43.6% | 51.2% | 45.9% | 46.6% |

| Former (use past year but not past 90 days) | 10.0% | 8.9% | 9.7% | 9.6% |

| Recent (use past 90 days but not current use) | 8.6% | 7.7% | 8.3% | 8.2% |

| Current, <5mg diazepam equivalents** | 3.8% | 5.5% | 4.3% | 4.3% |

| Current, 6–9mg | 8.2% | 8.5% | 8.3% | 8.2% |

| Current, 10–19mg | 13.0% | 10.5% | 12.2% | 11.9% |

| Current, 20+mg | 12.8% | 7.7% | 11.3% | 11.2% |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | 37.9% | 27.6% | 34.8% | 35.1% |

| Bipolar disorder medication | 17.2% | 9.9% | 15.0% | 15.1% |

| Emergency department visit prior 30 days | 15.4% | 10.4% | 13.9% | 14.1% |

| Musculoskeletal relaxant | 53.8% | 41.6% | 50.0% | 49.7% |

| Unintentional fall | 10.3% | 6.1% | 9.0% | 9.1% |

| Emergency department visit for injury | ||||

| 1–5 visits | 29.2% | 20.4% | 26.5% | 26.7% |

| 6 or more visits | 1.2% | 0.4% | 0.9% | 0.9% |

| Outpatient visits for injury | ||||

| 1–10 visits | 41.7% | 36.4% | 40.1% | 40.4% |

| 11 or more visits | 0.7% | 0.4% | 0.6% | 0.6% |

There were 74,782 persons with only prescriptions for propoxyphene, 213,691 with only prescriptions for hydrocodone, and 200,535 with prescriptions for both.

Benzodiazepine dose equivalents: Alprazolam (0.75 mg), Bromazepam (6 mg), Chlordiazepoxide (15 mg), Clonazepam (0.5 mg), Clorazepate (7.5 mg), Diazepam (4 mg), Estazolam (1 mg), Flurazepam (15 mg), Halazepam (60 mg), Lorazepam (1 mg) Oxazepam (30 mg), Quazepam (15 mg), Temazepam (7.5 mg), Triazolam (0.125 mg).

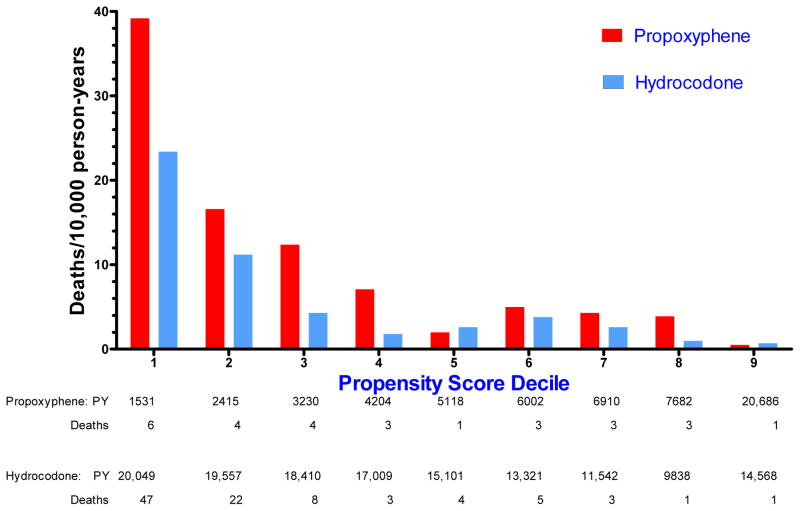

The study included 139,395 person-years of hydrocodone current use and 57,778 person-years of propoxyphene current use, with 94 and 28 medication toxicity deaths, respectively**. The unadjusted incidence of such deaths was greater in the hydrocodone group (6.7 per 10,000 person-years) than in the propoxyphene group (4.8 per 10,000). However, analysis according to propoxyphene propensity score deciles revealed strong confounding (Figure 4), with rates of death in the lowest decile more than 30 times those in the highest decile. Within each decile, the rates for propoxyphene were generally greater than those for hydrocodone.

Figure 4.

Unadjusted incidence of medication toxicity deaths among current users of propoxyphene and hydrocodone, according to decile of the propoxyphene propensity score. PY denotes person-years of current use. In this and all other stratified analyses, the two highest propensity deciles were combined to assure at least 1 endpoint per stratum.

Time-Dependent Propensity Score Analyses

In the prescription-relative time origin analysis, the univariate HR for propoxyphene was 0.70 (0.46–1.07) (Table 2), indicating a non-significant protective effect for propoxyphene. However, the HR with all of the covariates in the model was 1.63 (1.04–2.57), indicating increased risk. The IPT-weighted analysis had a point estimate (HR = 1.65 [1.01–2.72]) nearly identical to the individual covariate analysis, although the 95% confidence interval (CI) was slightly wider. Both stratification by propensity score deciles and inclusion of these in the regression model led to slightly higher point estimates (1.72 [1.09–2.69] and 1.73 [1.10–2.71] respectively), but with confidence interval widths more comparable to that from the individual covariate analysis.

Table 2.

Performance of analyses with time-dependent propensity scores relative to those with time-dependent individual covariates and marginal structural model analyses. IPT denotes inverse probability of treatment.

| Model | Description | Hazard Ratio Estimate | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-Dependent Covariate Analyses: Propensity Score versus Individual Covariates | |||

| Time Origin Prescription-Relative | |||

| 1 | Univariate | 0.70 | 0.46–1.07 |

| 2 | Individual covariates in regression model | 1.63 | 1.04–2.57 |

| 3 | Propensity score: IPT weighting | 1.65 | 1.01–2.72 |

| 4 | Propensity score: stratified by propensity score deciles | 1.74 | 1.10–2.75 |

| 5 | Propensity score: regression model includes propensity score deciles | 1.73 | 1.10–2.71 |

| Time Origin Person-Relative | |||

| 6 | Univariate | 0.71 | 0.47–1.09 |

| 7 | Individual covariates in regression model | 1.67 | 1.06–2.62 |

| 8 | Propensity score: IPT weighting | 1.69 | 1.03–2.77 |

| 9 | Propensity score: stratified by propensity score deciles | 1.77 | 1.12–2.78 |

| 10 | Propensity score: regression model includes propensity score deciles | 1.78 | 1.13–2.80 |

| Marginal Structural Model Analyses* | |||

| 11 | Weights truncated at 1st, 99th percentiles | 1.64 | 0.83–3.27 |

| 12 | Weights truncated at 5th, 95th percentiles | 1.63 | 0.82–3.24 |

| 13 | Discrete time approximation, variable prescription length allowed | 1.64 | 0.84–3.20 |

| 14 | Discrete time approximation, fixed prescription length assumed | 1.56 | 0.80–3.04 |

Unless otherwise specified, estimated with proportional hazards with time-dependent inverse probability of treatment and censoring weights truncated at the 1st and 99th percentiles.

Person-relative time origin analyses had generally similar findings (Table 2). Point estimates after adjustment for either the individual covariates or the time-dependent propensity score were slightly higher than those from the prescription-relative analysis. The IPT-weighted analysis HR was closest to that from the individual covariate analysis, but the CI was slightly wider.

Marginal Structural Model Analyses

The marginal structural model estimate (HR = 1.64 [0.83–3.27]) was virtually identical to the prescription-relative analyses that included individual covariates in the regression model or that was IPT-weighted (Table 2). However, the 95% confidence interval was substantially wider and included 1. Truncating the weights at the 5th and 95th percentiles did not materially alter this finding, nor did use of a discrete time approximation with variable-length time periods. The estimate from the discrete time approximation with fixed-length time periods was slightly lower.

Discussion

In our case study, time-dependent propensity score analysis results were quite comparable to those from analyses with time-dependent covariates in a regression model. This was true for both prescription-relative and person-relative time origins. These analyses had point estimates close to those from marginal structural model analyses (although no formal tests of significance were performed). This suggests that causal pathway confounding was minimal, informally justifying the time-dependent propensity score approach for the study dataset.

The setting for the propoxyphene marginal structural model analyses differs from that of many previously published studies,6;10–12 which typically analyzed the effects of long-term treatments on chronic diseases, such as antiretroviral therapy efficacy for HIV. Once initiated, treatment was assumed to persist,11 limiting variation in weights. In contrast, we studied an acute drug treatment for which disease risk was most plausibly altered only during periods of active medication use. Thus, we formulated marginal structural models that ignored person-time off drug and had weights that permitted treatment to change with each new time period. The outcome model allowed variable-length time periods, reflecting the common circumstance in which prescriptions define different periods of probable drug treatment. This application of marginal structural models may be useful for other pharmacoepidemiologic studies.

Confidence intervals for the marginal structural model analyses were substantially wider than those for the other analyses, even after stabilizing and truncating the weights. This suggests that for pharmacoepidemiology applications with limited causal pathway confounding, the mean square error for marginal structural model estimates may be greater than those from time-dependent propensity score analyses. In addition, use of stabilized weights for marginal structural models requires including the baseline covariates in the model for the numerator of these weights in the outcome model, problematic for large numbers of baseline covariates. Indeed, the original cohort for this case study had 206 covariates, but only 122 medication toxicity deaths.5

The period of current drug use defined by a filled prescription, during which the exposure was fixed, was the shortest time interval for which covariate values were updated. Similarly, we used this period for calculation of weights in the marginal structural model analyses. This approach was necessary because the positivity assumption 25 requires that the probability of either treatment be non-zero for each study time period. However, if covariate changes within the prescription interval were important (for example, prescriptions issued for long time periods), then propensity-score-based analyses might be suboptimal. In our case study (as in many pharmacoepidemiologic studies), prescription intervals were short (ranging between 2 and 30 days) and covariate changes within the intervals infrequent.

We suggest the time origin be chosen according to the pattern of drug treatment and the hypothesized mechanism by which this affects the endpoint. In our example, study opioid use typically was episodic and toxicity was most plausibly related to current rather than past exposure. This argues for the prescription-relative time origin as risk sets will consist of comparable days relative to the prescription fill. However, for treatments that are less variable or have cumulative effects, a person-relative origin might be more appropriate, although in this circumstance causal pathway confounding might be more likely.

Because our findings come from a single case study, the extent to which they can be generalized to other circumstances is unknown. Although prior study of time-dependent propensity score analyses has been limited,26 our findings suggest these methods are useful for pharmacoepidemiologic studies with large numbers of covariates and time periods, but minimal causal pathway confounding. For the data set studied, these analyses yielded point estimates very comparable to those from either inclusion of individual time-dependent covariates in regression models or from marginal structural model analyses. Further research to better define the reliability and utility of time-dependent propensity score analyses is needed.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL081707, HL114518), the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (HD074584), the National Institute for Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (P60AR056116), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01AI093234).

We gratefully acknowledge the Tennessee Bureau of TennCare and the Department of Health, which provided study data.

Appendix

1. Time-Dependent Propensity Score: Piecewise Exponential Approximation to Proportional Hazards

The justification for time-dependent propensity scores in Methods, §3-b reduced the time-dependent case to the time-invariant case. The piecewise exponential model provides a concrete illustration of this reasoning. As shown in Figure 2, followup for subject i is divided into ti periods of length sit such that a treatment (exposure) variable (ait) and a set of covariates (lit) are constant for the period and with an indicator variable for outcome (endpoint) occurrence (yit). We assume that for each period the hazard, conditional on the treatment and covariates, is constant. For this model,26 the hazard function

| (1) |

where β0t is the log of the constant hazard for period t. Estimation of parameters for model (1) is known to be equivalent to estimation of those for a Poisson count variable model in an independent pseudo-population of Σti subjects, where each subject corresponds to a single time period.1–3 In this model

| (2) |

In the original problem the yit are neither Poisson (because they cannot take on values >1) nor independent (for each person, only the last can be 1). However, because the likelihoods for these models coincide,1–3 solving (2) is equivalent to solving (1), a result that is the basis for Poisson regression for individual subjects with time-dependent covariates. The duality of these models allows us to transform a time-dependent covariate problem (1) into a time-invariant problem (2). Thus, if conditioning on the propensity score in model 2 will provide the same result as conditioning on the covariates, the same will occur for model 1.

If there is causal pathway confounding, estimates conditional on the individual time-dependent covariates will not estimate the conditional treatment effect. By the results above, estimates based on time-dependent propensity score analyses will be similarly biased.

2. Marginal Estimates Via IPT Weighting: Analyses Based on Weights from Time-Dependent Propensity Scores Versus Those from Marginal Structural Models††

Conceptually, marginal structural models create pseudo-populations in which the treatment is sequentially randomized. This permits consistent estimation of the marginal mean of potential outcome . In contrast, inverse weighting with the time-dependent propensity score creates a pseudo-population in which the randomization occurs at time t, which permits consistent estimation of the marginal mean of potential outcome Ytat (see below). However, even in the absence of causal pathway confounding (scenario depicted in Figure 1-b) the effect of At on Yt would be confounded by previous treatment history Āt−1 in the pseudo-population generated by inverse time-dependent propensity score weighting. That is, since the previous treatment history Āt−1 can affect the outcome Yt independently of the current treatment At, the marginal mean of potential outcome is not necessary equal to that for Ytat. Thus, we cannot establish equivalence between the two weighting methods for the scenario in Figure 1-b.

We can demonstrate this equivalence if the entire treatment effect is mediated by the current value of the treatment variable (Figure 1-c scenario). First, we show the inverse time-dependent propensity score weighted mean is equal to the marginal mean of potential outcome Ytat assuming consistency, conditional exchangeability, and positivity. The inverse time-dependent propensity score weighted mean can be written as

where I(·) is the indicator function and f(·) is the conditional probability mass function.

If we further assume the potential outcome has the same marginal mean as the potential outcome , that is , then the two weighting procedures both estimate the marginal mean of potential outcome .

3. Changes from Prior Study

Drug exposure

For the present study, there were minor changes in the definitions of drug exposure. In the prior study, current use began on the day the prescription was filled and terminated with the end of the days of supply.4 We reduced the number of prescriptions per person by combining contiguous prescriptions for study opioids, so long as the periods of current use overlapped, combined current use was no more than 30 days (Tennessee Medicaid generally has a maximum of 30 days of supply) and none of the covariates changed. This only affected the marginal structural model analyses, for which reducing the number of time periods per person led to more stable weights. We also extended the period of current use by 1 day for prescriptions for which this period was less than 30 days, which did not materially affect study findings. This permitted combining prescriptions with a 1 day separation between periods of current use (not uncommon for the study opioids), further reducing the number of prescriptions per person.

Covariates

The original study included 206 covariates. The present analysis included 22 covariates (Appendix Table 1) that accounted for most of the confounding. The prescription-relative propensity-scorestratified analysis based on the 206 covariates from the original study yielded an HR of 1.82, whereas that from the analysis based on the 22 covariates for the present study was 1.74.

Appendix Table 1.

Study covariates, binary unless otherwise noted.

| Covariate | Comparison |

|---|---|

| 1. Age at prescription fill | Continuous, per year |

| 2. Calendar year 1992 to 1995 | Vs 2004–2007 |

| 3. Calendar year 1996 to 1999 | Vs 2004–2007 |

| 4. Calendar year 2000 to 2003 | Vs 2004–2007 |

| 5. Sex, female | Vs male |

| 6. Residence standard metropolitan statistical area | Yes vs no |

| 7. Medicaid enrollment uninsured | Yes vs no |

| 8. Benzodiazepine, former (use past year but not past 90 days) | Vs no use past year |

| 9. Benzodiazepine, recent (use past 90 days but not current use) | Vs no use past year |

| 10. Benzodiazepine, current, <5mg diazepam equivalents** | Vs no use past year |

| 11. Benzodiazepine, current, 6–9mg | Vs no use past year |

| 12. Benzodiazepine, current, 10–19mg | Vs no use past year |

| 13. Benzodiazepine, current, 20+mg | Vs no use past year |

| 14. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | Any past year vs none |

| 15. Bipolar disorder medication | Any past year vs none |

| 16. Emergency department visit prior 30 days | Yes vs no |

| 17. Musculoskeletal relaxant | Any past year vs none |

| 18. Unintentional fall | Any past year vs none |

| 19. Emergency department visit for injury, 1–5 visits | Vs none past year |

| 20. Emergency department visit for injury, 6 or more visits | Vs none past year |

| 21. Outpatient visits for injury, 1–10 visits | Vs none past year |

| 22. Outpatient visits for injury, 11 or more visits | Vs none past year |

4: Marginal Structural Model Weights

Weight calculation

The time-dependent weights are the product of a treatment weight (denoted by superscript x) and a censoring weight (superscript c):

where the individual terms for the products are

where the bar notation denotes the history of the values of the time-varying treatment or covariate through the specified time period (see Figure 2 for notation). The models for the treatment weight numerator and denominator, respectively, were

This modeled treatment probability for a time period as a function of treatment in the prior period and either the baseline covariates or the covariates in the current time period. (Throughout this section, for simplicity we denote all parameters with α, although these parameters clearly differ between models.) Given that much study opioid use was episodic, we hypothesized it was more strongly related to recent rather than remote history.

The models for the censoring weight numerator and denominator, respectively, were

The term for the time period (k) was included because it was strongly related to the probability of censoring.

The distribution of the weights (excluding those for the first time period, which by definition were 1) is shown in Appendix Table 2. Given the extreme values, they were truncated at the 1st and 99th percentiles.

Appendix Table 2.

Distribution of marginal structural model (MSM) weights (prior to truncation). Excludes weights for the first time period, which by definition are 1.

| Percentile | MSM Treatment Weight | MSM Censoring Weight | MSM Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | 0.000038572 | 0.000029843 | 0.000025259 |

| 1st | 0.114841621 | 0.073919730 | 0.027046284 |

| 5th | 0.318198241 | 0.206221984 | 0.118766570 |

| 10th | 0.468472236 | 0.321313504 | 0.224852629 |

| 25th | 0.737734956 | 0.574393955 | 0.500723452 |

| 50th | 0.997192171 | 0.845243987 | 0.836161037 |

| 75th | 1.191405556 | 0.982832114 | 1.067799465 |

| 90th | 1.704992879 | 1.352723708 | 1.630875634 |

| 95th | 2.491622884 | 2.049419746 | 2.551147684 |

| 99th | 8.496094814 | 6.240454391 | 9.241844235 |

| Maximum | 467370.8417 | 1059.279845 | 140312.1591 |

5. Marginal Structural Models, Discrete Time Approximation

In the discrete time approximation, a data set is created with one observation for each time period of each subject. The probability of an outcome for subject i in period t (e.g., yit = 1, see Figure 2), given that none has yet occurred is then modeled. The approximation is accurate if this probability is low for each period, which is the case for medication toxicity deaths.

The most common discrete time approximation is the pooled logistic model. The distribution of yit is assumed to be binomial and the model is:

However, this assumes that the time periods are of equal length. As Alison5 notes (pp 248–249), applying this analysis to data for which the intervals are of unequal length can result in biased estimates if the probability of the outcome is related to the length of the interval. For the present study the risk of medication toxicity death is most plausibly associated with acute opioid exposure and thus should increase with increasing periods of exposure. Given that this can vary markedly for the study opioid prescriptions, we used a discrete time approximation that accounted for the days of opioid current use in each prescription. We can use the piecewise exponential approximation to proportional hazards and the equivalence of this to Poisson regression with independent count variables1–3 to solve

This discrete time approximation is a standard way of accounting for events whose occurrence is dependent on the length of a time interval (e.g., see Kalbfleisch and Prentice6 p.136).

These models are over-parameterized given that they include a term for the hazard during each time period. We followed two approaches to estimating these parameters. First, we simply estimated a single intercept term, the assumption of constant hazard. Second, we performed an additional analysis that included time period via 6 indicator variables: for time periods 1–10, 11–20, …, and 61+. The results were essentially identical to those of the primary analysis with a single intercept term and thus are not presented.

In the discrete time approximation, the weighting creates a pseudo-population in which a single subject with an endpoint could be included multiple times. To account for this, robust variance estimation via generalized estimating equations was used. This utilized SAS Proc GENMOD with the statement

6: SAS Analysis Programs

/* ================== Analysis programs for Table 2 ========================== */ /* Each analysis is referred to by its number in the “Model” column of Table 2 */ /* Inputs */ /* Datasets RxAnalysis08 Includes one observation for each study prescription Observation variables listed below */ /* Variables recip ID of individual cohort members curdays Days of current use in prescription lpyears log(curdays/365) Ptime0 Person-relative time, first day of prescription Ptime1 Person-relative time, last day of prescription xanypois_cur Indicator variable for endpoint tab1opioid Exposure: 0 = hydrodocone, 1 = propoxyphene &Reduced_Variables Covariate values for given prescription, e.g., lit &Reduced_Variables_1 Covariate values for first prescription, e.g., li1 IPT_Weight Inverse probability of treatment weight for prescription Rx_Decile Propensity score decile for prescription Wit Marginal structural model weight, truncation 1/99 % Wita “ ”, truncation 5/95 */ /* Formats decilef Combines upper two deciles propensity score */ /* Macros %PrintCoxParms Prints proportional hazards parameter estimates %PrintGENMODParms1 Prints generalized linear model parameter estimates */ Title2 ‘Time-dependent propensity score’; Title3 ‘1. Prescription relative, Univariate’; ods select none; proc phreg data=data.RxAnalysis08; class tab1opioid /descending; model curdays*xanypois_cur(0) = tab1opioid /RL; ods output ParameterEstimates=data.RxTab02_01; run; %PrintCoxParms(DataFile=data.RxTab02_01); run; Title3 ‘2. Prescription relative, Individual covariates ‘; ods select none; proc phreg data=data.RxAnalysis08; class tab1opioid /descending; model curdays*xanypois_cur(0) = &Reduced_Variables tab1opioid /RL; ods output ParameterEstimates=data.RxTab02_02; run; %PrintCoxParms(DataFile=data.RxTab02_02); run; Title3 ‘3. Prescription-relative, IPT weighting, robust variance’; ods select none; proc phreg data=data.RxAnalysis08 covs(aggregate); weight IPT_Weight; ID Recip; class tab1opioid/descending; model curdays*xanypois_cur(0) = tab1opioid /RL; ods output ParameterEstimates=Data.RxTab02_03; run; %PrintCoxParms(DataFile=data.RxTab02_03); run; Title3 ‘4. Prescription-relative, Propensity score decile stratification ‘; ods select none; proc phreg data=data.RxAnalysis08; format Rx_Decile decilef.; strata Rx_Decile; class tab1opioid /descending; model curdays*xanypois_cur(0) = tab1opioid /RL; ods output ParameterEstimates=Data.RxTab02_04; run; %PrintCoxParms(DataFile=Data.RxTab02_04); Title3 ‘5. Prescription-relative, Propensity score decile in model’; ods select none; proc phreg data=data.RxAnalysis08; format Rx_Decile decilef.; class tab1opioid Rx_Decile/descending; model curdays*xanypois_cur(0) = Rx_Decile tab1opioid /RL; ods output ParameterEstimates=Data.RxTab02_05; run; %PrintCoxParms(DataFile=Data.RxTab02_05); Title3 ‘6. Person-relative, Univariate’; ods select none; proc phreg data=data.RxAnalysis08; class tab1opioid /descending; model (Ptime0,Ptime1)*xanypois_cur(0) = tab1opioid /RL; ods output ParameterEstimates=data.RxTab02_06; run; %PrintCoxParms(DataFile=data.RxTab02_06); run; Title3 ‘07. Person-relative, individual covariates in model’; ods select none; proc phreg data=data.RxAnalysis08; class tab1opioid /descending; model (Ptime0,Ptime1)*xanypois_cur(0) = &Reduced_Variables tab1opioid /RL; ods output ParameterEstimates=data.RxTab02_07; run; %PrintCoxParms(DataFile=data.RxTab02_07); run; Title3 ‘08. Person-relative, IPT weighting, robust variance’; ods select none; proc phreg data=data.RxAnalysis08 covs(aggregate); weight IPT_Weight; ID Recip; class tab1opioid/descending; model (Ptime0,Ptime1)*xanypois_cur(0) = tab1opioid /RL; ods output ParameterEstimates=Data.RxTab02_08; run; %PrintCoxParms(DataFile=data.RxTab02_08); run; Title3 ‘09. Person-relative, Propensity score decile stratification ‘; ods select none; proc phreg data=data.RxAnalysis08; format Rx_Decile decilef.; Strata Rx_Decile; class tab1opioid/descending; model (Ptime0,Ptime1)*xanypois_cur(0) = tab1opioid /RL; ods output ParameterEstimates=Data.RxTab02_09; run; %PrintCoxParms(DataFile=data.RxTab02_09); run; Title3 ‘10. Person-relative, Propensity score decile in model’; ods select none; proc phreg data=data.RxAnalysis08; format Rx_Decile decilef.; class tab1opioid Rx_Decile/descending; model (Ptime0,Ptime1)*xanypois_cur(0) = Rx_Decile tab1opioid /RL; ods output ParameterEstimates=data.RxTab02_10; run; %PrintCoxParms(DataFile=data.RxTab02_10); run; Title2 ‘Marginal Structural Models’; Title3 ‘11. Proportional hazards with time-dependent weights, robust variance’; ods select none; proc phreg data=data.RxAnalysis08 covs(aggregate); weight Wit; ID Recip; class tab1opioid /descending; model (Ptime0,Ptime1)*xanypois_cur(0) = &Reduced_Variables_1 tab1opioid /RL; ods output ParameterEstimates=data.RxTab02_11; run; %PrintCoxParms(DataFile=data.RxTab02_11); run; Title3 ‘12. Proportional hazards, time-dependent weights, robust variance, 5/95 trunc’; ods select none; proc phreg data=data.RxAnalysis08 covs(aggregate); weight Wita; ID Recip; class tab1opioid /descending; model (Ptime0,Ptime1)*xanypois_cur(0) = &Reduced_Variables_1 tab1opioid /RL; ods output ParameterEstimates=data.RxTab02_12; run; %PrintCoxParms(DataFile=data.RxTab02_12); run; Title3 ‘13. Discrete time approximation, variable length time period’; ods select all; proc genmod data=data.rxanalysis08 descending; weight Wit; class recip tab1opioid/descending; model xanypois_cur = &Reduced_variables_1 tab1opioid/dist=poisson link=log offset=lpyears; repeated subject=recip/sorted type=ind; ods output ParameterEstimates=Data.RxTab02_13; run; %PrintGENMODParms1(DataFile=Data.RxTab02_13); Title3 ‘14. Discrete time approximation, fixed length time period’; ods select all; proc genmod data=data.RxAnalysis08 descending; weight Wit; class recip tab1opioid/descending; model xanypois_cur = &Reduced_variables_1 tab1opioid/dist=binomial link=logit; repeated subject=recip/sorted type=ind; ods output ParameterEstimates=Data.RxTab02_14; run; %PrintGENMODParms1(DataFile=Data.RxTab02_14);

REFERENCES

- 1.Friedman M. Piecewise exponential models for survival data with covariates. Annals of Statistics. 1982;10:101–113. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holford TR. The analysis of rates and survivorship using log-linear models. Biometrics. 1980;36:299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laird N, Olivier D. Covariance analysis of censored survival data using log-linear analysis technique. J Amer Statist Assoc. 1981;76:231–240. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ray WA, Murray KT, Kawai V, et al. Propoxyphene and the risk of out-of-hospital death. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22:403–412. doi: 10.1002/pds.3411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allison PD. A Practical Guide. 2. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2010. Survival Analysis Using SAS. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. 2. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

To reduce notational complexity, subscripts indicating subjects are omitted. Upper case letters denote random variables, lower case their observed values. denotes the treatment history (a0, a1, …, at) through time t with similar notation for the history of other variables. The orthogonal symbol ⊥ denotes independence; the vertical bar | conditioning, Pr[ ] probability.

See Daniel et al12 §4.2.7 for a generalization for non-binary treatments.

The notation for the remainder of the Methods, shown in Figure 2, allows for time-to-event data and right censoring. It does not distinguish between random variables and observed values. Thus, instead of Pr[Ait = ait] to denote the probability that the exposure random variable for time period Ait takes on its observed value ait, we write Pr[ait].

The parameter β1 technically differs between models: some represent marginal effects (e.g., Models 1, 3, and 4) and others conditional effects (e.g., Models 2 and 5).

The prior study had 27 medication toxicity deaths in the propoxyphene group; the additional death in the present study resulted from the one day extension of the period of current use.

The notation is that of the Methods, §1-a to §1-c (also see Figure 1). To better illustrate the underlying logic of the justification, we assume a fixed number of time periods (0,1, …, t) with no censoring; generalization to other scenarios is traightforward. The treatment and covariates are defined just before each of time periods with the outcome observed at the end of time period t.

References

- 1.Thapa PB, Gideon P, Fought RL, Ray WA. Psychotropic drugs and the risk of recurrent falls in ambulatory nursing home residents. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:202–211. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ray WA, Stein M, Daugherty JR, Hall K, Arbogast PG, Griffin MR. COX-2 selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of serious coronary heart disease. Lancet. 2002;360:1071–1073. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ray WA, Murray KT, Meredith S, Narasimhulu SS, Hall K, Stein CM. Oral erythromycin use and the risk of sudden cardiac death. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1089–1096. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ray WA, Murray KT, Hall K, Arbogast PG, Stein CM. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1881–1890. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ray WA, Murray KT, Kawai V, et al. Propoxyphene and the risk of out-of-hospital death. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22:403–412. doi: 10.1002/pds.3411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robins JM, Hernan MA, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in Epidemiology. Epidemiol. 2000;11:550–560. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shadish WR, Steiner PM. A primer on propensity score analysis. Newborn & Infant Nursing Reviews. 2010;10:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding on observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46:399–424. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arbogast PG, Ray WA. Performance of disease risk scores, propensity scores, and traditional multivariable outcome regression in the presence of multiple confounders. Am J Epi. 2011;174:613–620. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernan MA, Brumback B, Robins JM. Marginal structural models to estimate the causal effect of zidovudine on the survival of HIV-positive men. Epidemiol. 2000;11:561–570. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westreich D, Cole SR, Tien PC, et al. Time scale and adjusted survival curves for marginal structural cox models. Am J Epi. 2010;171:691–700. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daniel RM, Cousens SN, De Stavola BL, Kenward MG, Sterne JAC. Methods for dealing with time-dependent confounding. Stat Med. 2013;32:1584–1618. doi: 10.1002/sim.5686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole SR, Hernan MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am J Epi. 2008;168:656–664. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ali MS, Groenwold RHH, Pestman WR, et al. Time-dependent propensity score and collider-stratification bias: an example of beta2-agonist use and the risk of coronary heart disease. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28:291–299. doi: 10.1007/s10654-013-9766-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawton K, Simkin S, Deeks J. Co-proxamol and suicide; a study of national mortality statistics and local non-fatal self poisonings. BMJ. 2003;326:1006–1008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7397.1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Afshari R, Good AM, Maxwell SRJ, Bateman DN. Co-proxamol overdose is associated with a 10-fold excess mortality compared with other paracetamol combination analgesics. Br J Clin Pharmac. 2005;60:444–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Afshari R, Maxwell S, Dawson A, Bateman DN. ECG Abnormalities in co-proxamol (paracetamol/dextropropoxyphene) poisoning. Clin Toxicol. 2005;43:255–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heaney RM. Left bundle branch block associated with propoxyphene hydrochloride poisoning. Ann Emerg Med. 1983;12:780–782. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(83)80259-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitcomb DC, Gilliam FR, Starmer CF, Grant AO. Marked QRS complex abnormalities and sodium channel blockade by propoxyphene reversed with lidocaine. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1629–1636. doi: 10.1172/JCI114340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sturmer T, Schneeweiss S, Brookhart MA, Rothman KJ, Avorn J, Glynn RJ. Analytic strategies to adjust confounding using exposure propensity scores and disease risk scores: Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and short-term mortality in the elderly. Am J Epi. 2005;161:891–898. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allison PD. A Practical Guide. 2. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2010. Survival Analysis Using SAS. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donner A, Klar N. Design and analysis of cluster randomization trials in health research. 1. London: Arnold; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao Y, Abrahamowicz M, Moodie EEM. Accuracy of conventional and marginal structural cox model estimators: A simulation study. The International Journal of Biostatistics. 2010;6:1–28. doi: 10.2202/1557-4679.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. 2. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Westreich D, Cole SR. Invited Commentary: Positivity in Practice. Am J Epi. 2010;171:674–677. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu B. Propensity score matching with time-dependent covariates. Biometrics. 2005;61:721–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2005.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]