Abstract

Background

Heavy episodic drinking (HED) is associated with sexual risk behavior and HIV seroconversion among men who have sex with men (MSM), yet few studies have examined heavy drinking typologies in this population.

Methods

We analyzed data from 4,075 HIV-uninfected MSM (aged 16 to 88) participating in EXPLORE, a 48-month behavioral intervention trial, to determine the patterns and predictors of HED trajectories. Heavy episodic drinking was defined as the number of days in which ≥5 alcohol drinks were consumed in the past 6 months. Longitudinal group-based mixture models were used to identify HED trajectories, and multinomial logistic regression was used to determine correlates of membership in each group.

Results

We identified five distinct HED trajectories: non-heavy drinkers (31.9%); infrequent heavy drinkers (i.e., <10 heavy drinking days per 6 month period, 54.3%); regular heavy drinkers (30-45 heavy drinking days per 6 months, 8.4%); drinkers who increased HED over time (average 33 days in the past six months to 77 days at end of follow-up, 3.6%); and very frequent heavy drinkers (>100 days per 6 months, 1.7%). Intervention arm did not predict drinking trajectory patterns. Younger age, self-identifying as white, lower educational attainment, depressive symptoms, and stimulant use were also associated with reporting heavier drinking trajectories. Compared to non-heavy drinkers, participants who increased HED more often experienced a history of childhood sexual abuse. Over the study period, depressive symptomatology increased significantly among very frequent heavy drinkers.

Conclusions

Socioeconomic factors, substance use, depression, and childhood sexual abuse were associated with heavier drinking patterns among MSM. Multi-component interventions to reduce HED should seek to mitigate the adverse impacts of low educational attainment, depression, and early traumatic life events on the initiation, continuation or escalation of frequent HED among MSM.

Keywords: alcohol, men who have sex with men, depression, substance use, educational attainment

INTRODUCTION

Unhealthy alcohol use has long been a public health concern among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM) (McKirnan and Peterson, 1989). Findings from some nationally representative surveys suggest that MSM use alcohol more frequently than heterosexual men (Cochran et al., 2000, Dermody et al., 2014). Frequent heavy episodic drinking (HED) has also been observed among some samples of urban MSM (Stall et al., 2001, Thiede et al., 2003). These disparities in alcohol use are posited to arise primarily as a consequence of social and cultural factors, including homophobia and other stressors, which uniquely affect sexual minority populations in the United States (Hughes, 2005).

Among MSM, alcohol use prior to or during sex has been associated with engagement in sexual risk behavior (Colfax et al., 2004, Koblin et al., 2003). Heavy alcohol use (including “binge” drinking) has been documented as an independent risk factor for HIV seroconversion in some studies (Koblin et al., 2006, Sander et al., 2013), but not in others (Plankey et al., 2007). Additionally, a growing body of literature has established relationships between heavy alcohol use and poorer HIV treatment outcomes among MSM (e.g., lower adherence to antiretroviral therapy resulting in more rapid HIV disease progression) (Woolf-King et al., 2014, Michel et al., 2010). Despite these public health concerns, few longitudinal studies have been conducted to examine the typologies of alcohol use among MSM, and to elucidate how these patterns may change over the lifecourse (Woolf and Maisto, 2009). Identification of typologies of heavy alcohol use among MSM is important for designing and implementing targeted intervention strategies for those subgroups with greatest risk for adverse clinical outcomes. Because heavy alcohol use is itself a broad category, encompassing infrequent heavy drinkers as well as consistently frequent heavy drinkers, greater differentiation among subgroup categories may have important implications for prevention and treatment programs. Finally, identification of typologies in heavy alcohol use among MSM would allow for the specification of unique risk factors, which may vary according to different levels of heavy alcohol use, leading to more specific, tailored prevention interventions. Descriptive and cross-sectional studies have shown broad associations between heavy alcohol use and specific drinking settings (Jones-Webb et al., 2013), parental substance abuse (Stall et al., 2001), peer engagement in risk behavior (Wong et al., 2008), as well as depression and other mental health outcomes (Stall et al., 2001, Wong et al., 2008) among MSM.

Recent longitudinal studies have investigated risk and protective factors for hazardous alcohol use in young people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT), including some work that examined drinking trajectories in adolescence to emerging adulthood (Marshal et al., 2009, Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008). Male and female LGBT youth are more likely to report alcohol use and have more rapid increases in drinking frequency than their heterosexual peers (Marshal et al., 2009). While much less is known about alcohol use trajectories among LGBT adults, a recent study using data from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) demonstrated that sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., race, income, and education), sexual sensation seeking, and internalized homophobia were predictive of sustained and increasing trajectories of combined heavy drinking and illicit drug use (Ostrow et al., 2012).

The objective of the current study was to examine the patterns and predictors of HED trajectories in a large cohort of MSM participating in an HIV prevention trial and recruited in six urban centers across the United States. To identify particularly high-risk sub-groups of MSM, we employed a semi-parametric, group-based trajectory modeling approach, used previously in other studies of alcohol use trajectories, including among HIV-infected women (Cook et al., 2013).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Sampling

The recruitment, sampling, data collection, measures, and other methods of the EXPLORE study (HIVNET 015) have been described in detail elsewhere (Chesney et al., 2003, Koblin et al., 2003, Koblin et al., 2004). The primary purpose of the study was to test the effect of a behavioral intervention in preventing HIV acquisition among MSM. The study protocol, intervention, training manuals, and interview details are also available from the study website: http://www.hptn.org/research_studies/hivnet015.asp.

In brief, study recruitment occurred between January 1999 and February 2001, taking place in the following six U.S. cities: Boston, Chicago, Denver, New York City, San Francisco, and Seattle. Participants were recruited using street- and venue-based outreach in areas where MSM were known to congregate (e.g., dance clubs, bathhouses, health clubs). Project staff also mounted public relations and media campaigns, with participants recruited through Internet sites, community forums, and community-based agencies. Finally, individuals were referred from other study participants and clinics. The institutional review boards of each participating center approved the study protocol.

Men were eligible to participate in EXPLORE if they were: HIV-uninfected at study enrollment (confirmed with an antibody test using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay); aged 16 years or older; and reported engaging in anal intercourse with one or more men during the past year. Men were excluded if they reported being in a mutually monogamous relationship with a partner of known HIV-uninfected status for two or more years. Of the 4,862 men assessed for eligibility, 4,295 (88.3%) met the inclusion criteria, agreed to participate, and provided written informed consent. Two weeks after enrollment, men were randomized to receive a behavioral intervention, consisting of ten counseling modules, or standard risk reduction counseling, provided twice yearly (Chesney et al., 2003). After randomization, participants completed a baseline assessment and were evaluated every six months for up to 48 months thereafter. Each assessment included an audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) behavioral questionnaire, HIV pre-test counseling, and blood specimen collection. Data collection continued until the end of the study in July 2003.

Since the group-based trajectory models only utilize information from participants followed longitudinally, we restricted the sample to the 4,077 (94.9%) who completed at least one follow-up assessment. Finally, we excluded two persons who were missing baseline alcohol use data. Therefore, the final analytic sample consisted of 4,075 MSM.

Measures

The primary outcome for this analysis was number of heavy episodic drinking (HED) days, derived from responses to the question, “On how many days in the last six months did you have five drinks or more?” Participants could report any non-negative integer number; we truncated a small number of responses (0.5%) in which the number of HED days was greater than 182 (i.e., every day in the past six months). This definition of HED has been well-validated among men (Wechsler and Nelson, 2001), has been shown to be a good indicator for alcohol-related problems (Jackson, 2008), is predictive of an increased risk of mortality (Plunk et al., 2014), and has been used previously to examine developmental HED trajectories among adolescents (Oesterle et al., 2004).

We examined a number of other alcohol-related constructs and variables. Participants were asked to report drinking frequency in the past six months (e.g., never, less than once a week, more than once a week, or daily). Participants also completed to the CAGE Questionnaire, a four-item clinical screening instrument, for which an affirmative response to 2 or more questions is commonly used as an indicator for alcohol-related problems (Ewing, 1984, Bush et al., 1987). At baseline, participants were also asked if they ever had a drinking problem (yes vs. no), and/or had ever received medical treatment for alcoholism, not including self-help programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous (yes vs. no). Finally, participants were asked to report the proportion of times in the last six months alcohol or drugs were used two hours prior to or during sex (never, occasionally, often, all the time).

In our analysis, we assessed a number of socio-demographic, behavioral, drug-related, and social factors as independent variables of interest. These variables were chosen based on a priori hypotheses informed by a review of previously published literature examining correlates of alcohol use among MSM (Stall et al., 2001, Woolf and Maisto, 2009, Wong et al., 2008, Mimiaga et al., 2009, Colfax et al., 2004, Ostrow et al., 2012). The following sociodemographic characteristics were examined: age (per year older); race (white/Caucasian, African American, or other/mixed race [which included Asian/Pacific Islander and Native American/Alaskan Native]); educational attainment (high school completion or less, some college, college degree, post-college education); annual income (<$12,000, $12,000 - $29,999, $30,000 - $59,999, ≥$60,000); student status (yes, no); and employment status (full-time, part-time, unemployed/other). To be consistent with previous EXPLORE analyses (Mimiaga et al., 2009, Bedoya et al., 2012), we defined childhood sexual abuse (CSA) as a sexual experience before the age of 13 with someone ≥5 years older, or a sexual experience between the ages of 13 and 17 with someone ≥10 years older (yes vs. no).

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression – Short Form (CES-D-SF) scale (Ross and Mirowsky, 1984). The shortened seven-item version has been validated previously (Cronbach’s α = 0.85) and correlates well (r = 0.92) with the full CES-D (Ross and Mirowsky, 1984, Radloff, 1977). As a cut-off point has not been established for the 7-item CES-D, we analyzed scores continuously, with higher scores (max. 21) representing greater levels of depressive symptomatology.

Finally, we examined the following social and substance use characteristics, referring to activities in the six months prior to the baseline interview: involvement in gay-related social or community activities, including political/social organizations, community events, and volunteer work (yes, no); termination of a primary relationship with a sex partner (yes, no); cocaine use (yes, no); crack use (yes, no); and amphetamine use (yes, no), including “speed”, crystal methamphetamine, etc.

Statistical Analyses

First, we examined the distribution of baseline characteristics using descriptive statistics (i.e., medians and proportions). Then, we plotted the distribution of number of HED days reported at baseline and at each follow-up assessment.

To identify distinct heavy drinking trajectories over time, we employed a longitudinal, semi-parametric method for estimating group-based mixture models (Nagin, 1999). The method is a specialized application of finite mixture modeling, and is designed to identify distinct clusters of individuals following similar trajectories over time (Jones and Nagin, 2007). The SAS macro (PROC TRAJ) sorts each individual’s set of reported number of HED days from each study assessment into clusters, estimating a single model consisting of distinct trajectories from all available data (Jones et al., 2001). Unlike latent class growth models, group-based mixture models estimate mean growth curves for each trajectory, and allow for individual variation around each curve (Muthén and Muthén, 2000). All available data is used to model group trajectories; therefore, individuals without a complete set of observations are included.

In all fitted models, we specified a censored normal outcome distribution, with a minimum equal to zero HED days and a maximum equal to 182 days. To run the procedure, we specified the number of groups to be fit, and the number of polynomial terms (e.g., intercept, linear, quadratic, etc.) for each group. The Bayesian information criterion (BIC) was used to select the model with the best fit. The observed mean number of HED days reported at each time point for each trajectory were plotted using TRAJPLOT (Jones, 2012).

Following estimation of the HED trajectories, we used multinomial logistic regression to identify correlates of trajectory membership. Specifically, the probability of membership in each of the five groups was examined, and the trajectory with the highest probability of membership was assigned to each participant. These group assignments were then used as dependent variables in regression-based analyses. To validate the modeled trajectories, we regressed group membership onto the other alcohol variables measured at baseline (i.e., alcohol/drug use during sex, CAGE scores, and self-reported drinking problems and receipt of alcohol treatment). The associations between behavioral, social, and drug-related factors measured at baseline and group membership were then examined in bivariate analyses. We also examined the relationship between the intervention arm and alcohol group membership. To identify the factors most strongly associated with membership in distinct heavy drinking trajectories, we constructed a multivariable multinomial regression model, including all variables significant at p < 0.05 in bivariable analyses.

Finally, recognizing that some factors, specifically depressive symptomology and substance use, may have changed over the course of the study, we used generalized linear mixed effect models (GLMM) to identify associations between group membership and changes in these covariates of interest over time. Specifically, time by group interaction terms were included in the GLMM to determine whether these variables (measured repeatedly at each follow-up) covaried with the observed HED trajectories. All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and all reported p-values are two-sided.

RESULTS

The 4,075 participants provided a total of 26,749 observations over the 48-month study period. At baseline, the median age was 34 (interquartile range [IQR]: 28 - 40), and 3,112 (76.4%) were white. Other baseline characteristics are detailed in Table 1. The median number of HED days reported in the past six months at baseline was 2 (IQR: 0-9). The majority (56.9%) reported drinking on average at least once per week.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of eligible sample (N = 4,075)

| Characteristic | Number (%) or Median (IQR) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Alcohol Variables | |

|

| |

| Number of heavy episodic drinking days† (past 6 months) | 2 (0 – 9) |

| Drinking frequency (last 6 months) | |

| Never | 427 (10.5) |

| Less than once per week | 1183 (29.0) |

| More than once per week | 2314 (56.9) |

| Daily | 147 (3.6) |

| CAGE Score§ (median, IQR) | 1 (0 – 2) |

|

| |

| Other Covariates | |

|

| |

| Age (median, IQR) | 34 (28 – 40) |

| Race | |

| White | 3112 (76.4) |

| African American | 283 (6.9) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 120 (2.9) |

| Native American/Alaskan Native | 35 (0.9) |

| Other/mixed race | 523 (12.8) |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 360 (8.8) |

| Some college | 1057 (25.9) |

| College degree | 1466 (36.0) |

| Post-College | 1191 (29.2) |

| Income | |

| < $12,000 | 498 (12.2) |

| $12,000 - $29,999 | 1105 (27.1) |

| $30,000 - $59,999 | 1591 (39.0) |

| ≥ $60,000 | 875 (21.5) |

| Student | |

| Yes | 652 (16.1) |

| No | 3420 (83.9) |

| Employment Status | |

| Full Time | 3106 (76.2) |

| Part Time | 584 (14.3) |

| Unemployed/Other | 385 (9.5) |

| Childhood Sexual Abuse* | |

| Yes | 1621 (39.8) |

| No | 2443 (60.0) |

| Depressive Symptomatology (CESD-SF)$ (median, IQR) | 5 (3 – 8) |

| Involvement in gay-related community activities¶ | |

| No | 812 (19.9) |

| Yes | 3263 (80.1) |

| Termination of primary relationship¶ | |

| Yes | 953 (23.4) |

| No | 3075 (75.5) |

| Cocaine Use¶ | |

| Yes | 775 (19.1) |

| No | 3295 (80.9) |

| Crack Use¶ | |

| Yes | 160 (3.9) |

| No | 3910 (96.1) |

| Amphetamine use¶ | |

| Yes | 520 (12.8) |

| No | 3548 (87.2) |

Defined as number of days in which five or more drinks were consumed in the past six months;

‡ Defined as >14 drinks/week or ≥5 drinks per occasion on a typical drinking day;

Defined as any sexual experience with someone ≥5 years older before the age of 13 and/or any sexual experience with someone who was ≥10 years older between the ages of 13 and 17;

Refers to activities in the past 6 months prior to the baseline interview;

Score ≥2 on the CAGE screening questionnaire indicative of current alcohol problem (Ewing, 1984).

CESD-SF = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Short-Form (7 items with max. score 21; higher scores represent greater depressive symptomatology) (Ross and Mirowsky, 1984).

The distribution of HED days observed at each assessment over the 48-month study period is shown in Figure 1. The proportion of individuals who reported zero HED days increased from 39.3% at baseline to 50.9% at 48 months of follow-up, while the proportion of persons reporting >30 HED days increased slightly, from 7.3% at baseline to 9.2% at the end of follow-up.

Figure 1. † Mountain plot of number of heavy episodic drinking† days (past 6 months) reported by Project EXPLORE Participants over 48 months of follow-up (N = 4,075).

Defined as number of days in which 5 or more alcoholic drinks were consumed in the past six months. Note: The decreased sample size in later months of follow-up is due to a common close out date of the trial (i.e., study participation ended regardless of when participants were recruited). Therefore, later visits are comprised only of those who were enrolled early in the recruitment period.

Heavy Episodic Drinking Trajectories

As shown in Supplemental Figure S1, we chose a five-group solution since it had the best fit to the data, based on the BIC. We selected a final model with intercept, linear, and quadratic terms for each group, as it had the best model fit.

The observed HED trajectories are shown in Figure 2. Approximately one-third of participants (31.9%) were classified as non-heavy drinkers (group 1) who, on average, reported 1.0 HED days in the past six months. Of these participants, 360 (27.7%) reported no alcohol use in the past six months at baseline. Compared to others in group 1, persons reporting no alcohol use did not differ with respect to age or race, but were more likely to have a high school or less education (p < 0.001) and earn less than $6,000 annually (p = 0.003). The majority of participants (54.3%) were classified as infrequent heavy drinkers (group 2), who reported, on average, 7.5 HED days in the past six months. This trajectory remained stable over the 48-month study period. The third group comprised 8.4% of the sample, and was classified as regular heavy drinkers. This group reported, on average, between 31.8 and 44.8 HED days in the past six months. A small proportion of participants (3.6%) were classified as increasingly frequent heavy drinkers (group 4). This trajectory was characterized by a moderate amount of HED days at baseline (average = 33.0), increasing to 76.6 by the final study assessment. A final and fifth group (1.7% of the sample) was classified as very frequent heavy drinkers, consistently reporting over 100 HED days throughout the study. By the final assessment this group reported, on average, 155.9 HED days, corresponding to 85.4% of all days during the six-month recall period. The mean probability of membership in each trajectory was 0.98, 0.99, 0.94, 0.99, and 1.00 for groups one through five, respectively.

Figure 2. Heavy episodic drinking trajectories among Project EXPLORE participants (N = 4,075).

† Defined as number of days in which 5 or more alcoholic drinks were consumed in the past 6 months. Note: dashed lines represent fitted values. Five-group solution with second order (quadratic) terms for each trajectory selected using BIC criteria. Implemented in SAS using PROC TRAJ (Jones et al., 2001).

The proportion of individuals who had at least three missing study assessments varied by group (p < 0.01). Specifically, the proportion missing at least three visits was smallest in the non-heavy drinking group (15.0%) and greatest in the increasingly frequent and very frequent HED groups (29.5% and 27.6%), respectively.

Correlates of Membership in Distinct Heavy Drinking Trajectories

Associations between membership in heavy drinking trajectories and alcohol-related variables are shown in Supplemental Table S1. Compared to non-heavy drinkers (group 1), membership in other trajectories was associated with self-reported alcohol or drug use during sex, baseline CAGE score ≥2, and self-reported history of a drinking problem at baseline. Compared to members in the non-heavy drinking trajectory, participants in the very frequent heavy drinking trajectory (group 5) had significantly greater odds of reporting lifetime receipt of alcohol treatment at baseline. Notably, individuals classified as infrequent heavy drinkers (group 2) were less likely to report a history of drinking-related problems and lifetime receipt of alcohol treatment at baseline, compared to members of the non-heavy drinking trajectory.

Factors associated with membership in each drinking trajectory in bivariable and multivariable analyses are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. In the final multinomial regression model, compared to participants classified as non-heavy drinkers, individuals in the infrequent heavy drinking trajectory (group 2) were: more likely to be younger, less likely to be African American, more likely to report a recent termination of a relationship (a “break up”) at baseline, and more likely to use cocaine. In the final model, individuals classified in group 3 (regular heavy drinkers), compared to non-heavy drinkers, had greater odds of: being younger, white, having less than a post-college education, reporting greater levels of depressive symptomatology, and using cocaine. Similarly, factors positively associated with membership in group 4 (increasingly frequent heavy drinkers) were younger age, white race, lower educational attainment, and cocaine use. Notably, increasingly frequent heavy drinkers had independently greater odds of reporting a history of CSA, compared to non-heavy drinkers. Finally, membership in the very frequent heavy drinking trajectory (group 5) was associated with lower educational attainment, higher levels of depressive symptomatology, and cocaine and/or crack use.

Table 2.

Factors associated with heavy drinking trajectory group membership among Project EXPLORE participants*

|

Group 1:

non-heavy drinkers (n = 1346) |

Group 2:

infrequent heavy drinkers (n = 2184) |

Group 3:

regular heavy drinkers (n = 331) |

Group 4:

increasingly frequent heavy drinkers (n = 156) |

Group 5:

very frequent heavy drinkers (n = 58) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Baseline Variable | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Age (per 10 years older) | ref | - | 0.6 | 0.6 – 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 – 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 – 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.5 – 0.9 |

| Race (ref = White) | ||||||||||

| African American | ref | - | 0.7 | 0.5 – 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.4 – 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.3 – 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 – 1.7 |

| Other/mixed race | ref | - | 1.1 | 0.9 – 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.6 – 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.7 – 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.3 – 1.6 |

| Education (ref = post-college) | ||||||||||

| College degree | ref | - | 1.6 | 1.3 – 1.9 | 2.5 | 1.8 – 3.6 | 2.8 | 1.7 – 4.8 | 2.1 | 0.9 – 4.9 |

| Some college | ref | - | 1.5 | 1.3 – 1.8 | 3.6 | 2.5 – 5.1 | 5.1 | 3.0 – 8.7 | 4.2 | 1.9 – 9.3 |

| High school or less | ref | - | 1.7 | 1.3 – 2.2 | 4.8 | 3.1 – 7.5 | 6.2 | 3.3 – 11.8 | 5.4 | 2.1 – 14.0 |

| Income (ref = ≥ $60,000) | ||||||||||

| $30,000 - $59,999 | 1.0 | 0.9 – 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.7 – 1.3 | 1.9 | 1.1 – 3.3 | 1.3 | 0.6 – 2.7 | ||

| $12,000 - $29,999 | ref | - | 1.1 | 0.9 – 1.4 | 1.3 | 0.9 – 1.9 | 2.4 | 1.4 – 4.2 | 1.5 | 0.7 – 3.4 |

| <$12,000 | ref | - | 1.2 | 0.9 – 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.0 – 2.4 | 3.4 | 1.8 – 6.3 | 1.9 | 0.8 – 4.8 |

| Student | not significant (p = 0.142) | |||||||||

| Employment (ref = Full Time) | not significant (p = 0.091) | |||||||||

| Childhood sexual abuse | ref | - | 1.0 | 0.9 – 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.8 – 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.3 – 2.6 | 1.1 | 0.6 – 1.8 |

| CES-D-SF (per unit increase)§ | ref | - | 1.0 | 1.0 – 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 – 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 – 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 – 1.2 |

| Not involved in gay activities¶ | not significant (p = 0.148) | |||||||||

| Recent Break-upঠ| ref | - | 1.5 | 1.2 Р1.7 | 1.3 | 1.0 Р1.8 | 1.7 | 1.2 Р2.5 | 1.0 | 0.5 Р2.0 |

| Cocaine use¶ | ref | - | 3.2 | 2.6 – 4.1 | 6.5 | 4.8 – 8.8 | 7.4 | 5.1 – 10.8 | 8.0 | 4.5 – 14.1 |

| Crack use¶ | ref | - | 1.5 | 1.0 – 2.3 | 3.8 | 2.3 – 6.4 | 3.1 | 1.5 – 6.3 | 8.7 | 4.1 – 18.8 |

| Amphetamine use¶ | ref | - | 2.3 | 1.8 – 2.9 | 2.6 | 1.8 – 3.7 | 3.1 | 2.0 – 4.9 | 3.8 | 2.0 – 7.4 |

| Intervention arm | not significant (p = 0.326) | |||||||||

Note: significant associations at p < 0.05 are shown in bold;

Multinomial logistic regression analyses using Group 1 as the reference category;

Refers to activities in the past 6 months prior to the baseline interview;

† Self-reported primary relationship with a male sex partner;

Self-reported termination of primary relationship;

CESD-SF = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Short-Form (7 items with max. score 21; higher scores represent greater depressive symptomatology) (Ross and Mirowsky, 1984).

Table 3.

Adjusted associations of factors associated with heavy drinking trajectory group membership among Project EXPLORE participants*

|

Group 1:

non-heavy drinkers (n = 1346) |

Group 2:

infrequent heavy drinkers (n = 2184) |

Group 3:

regular heavy drinkers (n = 331) |

Group 4:

increasingly frequent heavy drinkers (n = 156) |

Group 5:

very frequent heavy drinkers (n = 58) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Baseline Variable | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI |

| Age (per 10 years older) | ref | - | 0.6 | 0.6 – 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 – 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 – 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.6 – 1.2 |

| Race (ref = White) | ||||||||||

| African American | ref | - | 0.6 | 0.4 – 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.3 – 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.2 – 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.1 – 1.2 |

| Other/mixed race | ref | - | 0.8 | 0.7 – 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.4 – 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.4 – 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.2 – 1.1 |

| Education (ref = post-college) | ||||||||||

| College Degree | ref | - | 1.2 | 1.0 – 1.5 | 2.0 | 1.4 – 2.9 | 2.2 | 1.3 – 3.8 | 1.7 | 0.7 – 3.9 |

| Some College | ref | - | 1.2 | 0.9 – 1.4 | 2.8 | 1.9 – 4.1 | 3.4 | 1.9 – 5.9 | 3.7 | 1.6 – 8.6 |

| High School or less | ref | - | 1.3 | 0.9 – 1.8 | 4.0 | 2.4 – 6.5 | 4.3 | 2.1 – 8.5 | 4.7 | 1.7 – 13.3 |

| Income (ref = ≥ $60,000) | ||||||||||

| $30,000 - $59,999 | 0.9 | 0.7 – 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.5 – 1.1 | 1.5 | 0.9 – 2.7 | 1.0 | 0.4 – 2.1 | ||

| $12,000 - $29,999 | ref | - | 0.8 | 0.7 – 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.5 – 1.2 | 1.4 | 0.7 – 2.6 | 0.9 | 0.4 – 2.1 |

| <$12,000 | ref | - | 0.9 | 0.7 – 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.5 – 1.4 | 1.9 | 0.9 – 3.8 | 0.8 | 0.3 – 2.3 |

| Childhood sexual abuse | ref | - | 1.0 | 0.9 – 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.7 – 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.1 – 2.2 | 0.8 | 0.5 – 1.5 |

| CES-D-SF (per unit increase)§ | ref | - | 1.0 | 1.0 – 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 – 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 – 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 – 1.1 |

| Recent Break-upঠ| ref | - | 1.2 | 1.0 Р1.4 | 1.1 | 0.8 Р1.4 | 1.3 | 0.9 Р1.9 | 0.9 | 0.4 Р1.7 |

| Cocaine Use¶ | ref | - | 2.5 | 2.0 – 3.2 | 5.2 | 3.7 – 7.3 | 5.6 | 3.7 – 8.7 | 5.2 | 2.7 – 10.1 |

| Crack Use¶ | ref | - | 0.9 | 0.6 – 1.5 | 1.6 | 0.9 – 3.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 – 2.2 | 3.3 | 1.3 – 8.1 |

| Amphetamine Use¶ | ref | - | 1.4 | 1.1 – 1.8 | 0.9 | 0.6 – 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.7 – 2.0 | 1.2 | 0.5 – 2.5 |

Note: significant associations at p < 0.05 are shown in bold;

Multivariate multinomial logistic regression analysis using Group 1 as the reference category;

Refers to activities in the past 6 months prior to the baseline interview;

† Self-reported primary relationship with a male sex partner;

Self-reported termination of primary relationship;

CESD-SF = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Short-Form (7 items with max. score 21; higher scores represent greater depressive symptomatology) (Ross and Mirowsky, 1984).

Concurrent Changes in Depression and Substance Use Over Time

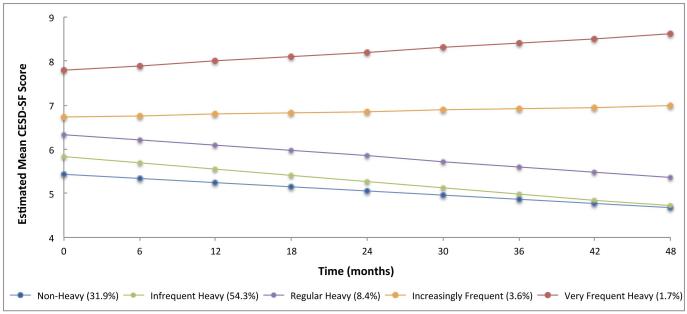

We examined whether membership in specific HED trajectories correlated with changes in levels of depressive symptomatology and substance use over time. In a repeated-measures GLMM analysis of depressive symptomatology, we observed significant differences between groups (type III p-value < 0.001), a significant trend over time (type III p-value = 0.018), and a significant time-by-group interaction effect (type III p-value < 0.001). Specifically, as shown in Figure 3, depressive symptomatology decreased among the non-heavy, infrequent heavy, and regular heavy drinking trajectories (all p < 0.05). Among the increasingly frequent heavy episodic drinking group, depressive symptomatology remained stable (time-by-group interaction term p = 0.417). Notably, CESD-SF scores increased among the very frequent heavy drinkers (p = 0.010). No statistically significant time-by-group interaction terms were observed for cocaine use, crack use, or amphetamine use.

Figure 3. Concurrent changes in depressive symptomatology among heavy episodic drinking trajectory groups.

Predicted mean CESD-SF scores obtained from a generalized linear mixed effects model including trajectory group, time, and time by group interaction terms.

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study of over 4,000 HIV-uninfected MSM, we identified five distinct heavy drinking trajectories over a 48-month study period. The majority of participants—greater than 85%—were classified as non-heavy or infrequent heavy drinkers. Membership in the three heavier drinking trajectories was significantly associated with current alcohol-related problems and a greatly increased risk of alcohol use prior to or during sex, as well as younger age, self-identifying as white, and low educational attainment. Among the small proportion of participants who increased their heavy drinking frequency over the study period, a history of childhood sexual abuse was independently associated with membership in this heavy drinking trajectory. Finally, although associations between baseline depressive symptomatology and HED trajectories were mixed, analyses revealed that membership in the heaviest episodic drinking category were significantly associated with increasing depression symptoms over time.

These results have important implications for public health and clinical practice. First, the vast majority of participants were classified as infrequent or non-heavy drinkers, among whom we failed to identify a subset whose heavy episodic drinking increased during follow-up. However, approximately 14% of study participants were classified into one of three heavy drinking trajectories, characterized by more than 26 HED days per six-month period (i.e., at least one HED day per week). Given that HED at a frequency of at least once per week has been shown to predict both increased morbidity and mortality among adults (Plunk et al., 2014, Room et al., 2005), participants within the heaviest drinking trajectories may be at risk of adverse alcohol-related health outcomes.

Collectively, these findings suggest that a “vulnerable populations” approach (Frohlich and Potvin, 2008) might be more effective than an overall population health approach in reducing alcohol use disparities among MSM. As a complementary strategy to population-level interventions, vulnerable subgroups approaches could focus on alcohol interventions that are designed for sub-groups of the population sharing common characteristics (e.g., exposure to childhood trauma; low educational attainment) that differentiate them from the rest of the population. Although widespread publicity campaigns have been a mainstay of HIV prevention efforts within MSM communities for some time (Kegeles et al., 1996), public health efforts, including venue-based interventions, may need to focus specific resources on the small subset of gay, bisexual, and other MSM who engage in regular heavy drinking, and whose drinking trajectories appear to be exacerbated by an accumulation of more ‘fundamental causes’ linked to their social position (Link and Phelan, 1995, Phelan and Link, 2005)..

Accounting for life course perspectives is a major strength of our approach, and the finding that educational attainment was a consistent correlate of membership in heavier drinking trajectories further supports the notion that a vulnerable groups approach may be warranted, recognizing the minority stress that MSM may experience is exacerbated by being less educated. Our findings regarding education attainment are consistent with other studies that have also documented associations between low education attainment and alcohol misuse among adults (Paschall et al., 2000, Greenfield et al., 2003).

The observed relationship with educational attainment may also be explained by the fact that alcohol use during young adulthood can adversely impact educational attainment in later life — again, pointing to the importance of understanding both the accumulation and concentration of risk amongst vulnerable population subgroups over the life course. One study observed that heavy alcohol use during adolescence, particularly in the context of low socioeconomic conditions, significantly diminished educational attainment for men, but not for women (Staff et al., 2008). Given that education was only assessed at baseline and the effect of changes to educational attainment on HED was not observed over time, the direction of this association remains in question and should be the focus of future work among MSM.

Our finding that CSA predicted increasingly frequent heavy episodic drinking adds to a growing body of literature demonstrating the enduring, detrimental effects of exposure to early childhood trauma among gay, bisexual, and other MSM (Mimiaga et al., 2009, Kalichman et al., 2004). The fact that CSA predicted increasing HED over the study period points to the potential benefit of improving access to mental health services for people seeking help to address early life trauma. Moreover, the intensification of existing efforts to ameliorate symptoms of PTSD, depression, and other mental health disorders resultant from such trauma may be effective at reducing heavy drinking among MSM. However, it is important to note that CSA was not associated with membership in the regular heavy or very frequent heavy drinking trajectories. Sociodemographic differences between the groups does not account for this discrepancy, as the multivariable model adjusted for age, race, education, and income. It is possible that individuals in the regular and very frequent heavy drinking trajectories were less likely to report childhood sexual abuse (relative to increasingly frequent heavy drinkers), resulting in differential misclassification towards the null. It is also possible that the association between CSA and increasing heavy episodic drinking is due to random chance. For these reasons, we recommend that this finding be interpreted with caution.

This study is subject to a number of limitations. First, EXPLORE study participants were not a random sample of all MSM in the United States, and thus the findings may not necessarily be generalizable to the larger, particularly less urban populations of MSM. Second, the selection and post hoc classification of heavy drinking trajectories was ultimately a subjective process, involving qualitative interpretation of bit fit trajectories. However, the identified trajectories were highly correlated with other measures of alcohol-related problems, including scores on the CAGE. Third, participation in the trial may have influenced drinking trajectories over follow-up. The intervention did include a module designed to address alcohol and drug use specifically in the context of sexual encounters, but did not address unhealthy alcohol use broadly (Chesney et al., 2003). Furthermore, we found no significant association between enrollment in the intervention versus control arm and HED trajectory membership. Thus, we expect the magnitude of this effect, if present, to be small. Fourth, although the group-based trajectory modeling assumes data are missing at random, the number of individuals with greater than three missing study visits varied by group. However, the number and shape of the best fit trajectories did not differ substantially when analyses were restricted to the 3,269 participants who completed at least six of the nine total study assessments (data not shown). Therefore, we expect potential biases arising from differential survey completion and attrition rates across HED group to be small. Fifth, given diminishing sample size over time due to the common close out date of the trial, the trajectory shapes in later follow-ups visits are subject to greater imprecision. Sixth, the relatively small number of individuals in the increasing and very frequent heavy drinking trajectories may have resulted in an increased probability of type-II error, which may explain the discrepant findings across a number of observed variables (including CSA and depression). Seventh, study outcomes were self-reported, and thus may be susceptible to socially desirable reporting and other biases. The EXPLORE study used ACASI-based interview methods in an attempt to minimize reporting biases. Finally, given significant changes in the social, cultural, political, and HIV prevention environment relevant to MSM in the United States over the past two decades, these data (collected between 1999 and 2003) may not be reflective of heavy episodic drinking patterns among MSM today. However, we note that recent studies have shown binge drinking and other unhealthy alcohol consumption patterns to be a continuing public health problem among MSM (Newcomb et al., 2014, Tobin et al., 2014), suggesting that the prevalence of HED in this population has not declined significantly.

In conclusion, the results of the current study suggest that the alcohol consumption patterns of a small proportion of MSM are characterized by engagement in regular or increasingly frequent heavy drinking. Socioeconomic factors (in particular, low educational attainment), childhood sexual abuse, depression, concurrent substance use, and current alcohol-related problems were most strongly associated with long-term heavy drinking trajectories, and thus may be effective targets for future intervention. To our knowledge no interventions have sought to address the adverse effect of low educational attainment on alcohol and substance use among MSM; however, a growing body of literature suggests that improving socioeconomic position, and the provision of educational opportunities, improves health and reduces disparities in adult populations (Williams et al., 2008, Richardson et al., 2012). Understanding the psychological and social mechanisms of action (e.g., coping strategies, peer networks) by which education might influence lifetime alcohol misuse could also aid in the design of preventative or treatment interventions targeting MSM with lower educational backgrounds. Furthermore, there is a need for new research to inform actions that could improve access to supportive services (e.g., counseling; peer support) for those MSM who have experienced early life trauma, particularly sexual trauma. New work in both these areas is crucial, as individuals from vulnerable subgroups of the MSM population are the least likely to be able to access existing services, and the most likely to be left out of the potential benefits offered through conventional interventions in this area.

Supplementary Material

ACKnOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the EXPLORE study participants and the entire EXPLORE Study Team. In particular, we would like to thank protocol co-chairs Drs. Margaret Chesney and Thomas Coates. We would also like to thank the project staff and teams at Boston’s Fenway Community Health Center and the Latin American Health Institute, Chicago’s Howard Brown Community Health Center (Site Principal Investigator David McKirnan), Denver Public Health (Site Principal Investigator Franklyn Judson), the New York Blood Center Site Principal Investigator Beryl Koblin), the San Francisco Department of Public Health (Site Co-Principal Investigators Susan Buchbinder and Grant Colfax), and Seattle’s University of Washington (Site Principal Investigator Connie Celum). We are also grateful for the assistance we received from staff at the Statistical Center for HIV/AIDS Research & Prevention (SCHARP) at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division. Finally, we would like to thank Drs. Deborah Donnell for her assistance accessing the EXPLORE data.

Sources of support: This work was funded by the US National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) grants U24-AA022000 and P01-AA019072, and in part by the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) grant P30-AI042853 through the Lifespan/Tufts/Brown Center for AIDS Research. The EXPLORE study was originally supported by the HIV Prevention Trials Network as study HIVNET 015, and was sponsored by the NIAID and NIAAA, of the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, through: contract N01-AI35176 with Abt Associates Inc.; contract N01-AI45200 with the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; and subcontracts with the Denver Public Health, the Fenway Community Health Center, the Howard Brown Health Center, the New York Blood Center, the Public Health Foundation Inc., and the University of Washington. This work was additionally sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), and the Office of AIDS Research of the National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services, through: a cooperative agreement with Family Health International (U01-AI46749) with a subsequent sub-contract to Abt Associates Inc. with sub-contracts to the Howard Brown Health Center and Denver Public Health; cooperative agreement U01-AI48040 to the Fenway Community Health Center; cooperative agreement U01-AI48016 to Columbia University (including a sub-agreement with the New York Blood Center); a cooperative agreement U01-AI47981 to the University of Washington; and cooperative agreement U01-AI47995 to the University of California, San Francisco.

REFERENCES

- Bedoya CA, Mimiaga MJ, Beauchamp G, Donnell D, Mayer KH, Safren SA. Predictors of HIV transmission risk behavior and seroconversion among Latino men who have sex with men in Project EXPLORE. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:608, 617. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9911-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush B, Shaw S, Cleary P, Delbanco TL, Aronson MD. Screening for alcohol abuse using the CAGE questionnaire. Am J Med. 1987;82:231, 235. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Koblin BA, Barresi PJ, Husnik MJ, Celum CL, Colfax G, Mayer K, McKirnan D, Judson FN, Huang Y, Coates TJ. An individually tailored intervention for HIV prevention: baseline data from the EXPLORE Study. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:933, 938. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Keenan C, Schober C, Mays VM. Estimates of alcohol use and clinical treatment needs among homosexually active men and women in the U.S. population. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:1062, 1071. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.6.1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colfax G, Vittinghoff E, Husnik MJ, McKirnan D, Buchbinder S, Koblin B, Celum C, Chesney M, Huang Y, Mayer K, Bozeman S, Judson FN, Bryant KJ, Coates TJ. Substance use and sexual risk: a participant- and episode-level analysis among a cohort of men who have sex with men. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:1002, 1012. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RL, Zhu F, Belnap BH, Weber KM, Cole SR, Vlahov D, Cook JA, Hessol NA, Wilson TE, Plankey M, Howard AA, Sharp GB, Richardson JL, Cohen MH. Alcohol Consumption Trajectory Patterns in Adult Women with HIV Infection. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:1705, 1712. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0270-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermody SS, Marshal MP, Cheong J, Burton C, Hughes T, Aranda F, Friedman MS. Longitudinal disparities of hazardous drinking between sexual minority and heterosexual individuals from adolescence to young adulthood. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43:30, 39. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9905-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252:1905, 1907. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.14.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohlich KL, Potvin L. Transcending the known in public health practice: the inequality paradox: the population approach and vulnerable populations. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:216, 221. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Sugarman DE, Muenz LR, Patterson MD, He DY, Weiss RD. The relationship between educational attainment and relapse among alcohol-dependent men and women: a prospective study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1278, 1285. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000080669.20979.F2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Corbin WR, Fromme K. Trajectories and determinants of alcohol use among LGB young adults and their heterosexual peers: results from a prospective study. Dev Psychol. 2008;44:81, 90. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL. Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among lesbians and gay men. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2005;23:283, 325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM. Heavy episodic drinking: determining the predictive utility of five or more drinks. Psychol Addict Behav. 2008;22:68, 77. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BL. TRAJ: Group-based modeling of longitudinal data. 2012 [Online]. Available at: http://www.andrew.cmu.edu/user/bjones/index.htm. Accessed April 1, 2014.

- Jones BL, Nagin DS. Advances in group-based trajectory modeling and an SAS procedure for estimating them. Sociol Method Res. 2007;35:542, 571. [Google Scholar]

- Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociol Method Res. 2001;29:374, 393. [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Webb R, Smolenski D, Brady S, Wilkerson M, Rosser BR. Drinking settings, alcohol consumption, and sexual risk behavior among gay men. Addict Behav. 2013;38:1824, 1830. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Gore-Felton C, Benotsch E, Cage M, Rompa D. Trauma symptoms, sexual behaviors, and substance abuse: correlates of childhood sexual abuse and HIV risks among men who have sex with men. J Child Sex Abus. 2004;13:1, 15. doi: 10.1300/J070v13n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegeles SM, Hays RB, Coates TJ. The Mpowerment Project: a community-level HIV prevention intervention for young gay men. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1129, 1136. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.8_pt_1.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblin B, Chesney M, Coates T, The EXPLORE Study Team Effects of a behavioural intervention to reduce acquisition of HIV infection among men who have sex with men: the EXPLORE randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2004;364:41, 50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16588-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblin BA, Chesney MA, Husnik MJ, Bozeman S, Celum CL, Buchbinder S, Mayer K, McKirnan D, Judson FN, Huang Y, Coates TJ. High-risk behaviors among men who have sex with men in 6 US cities: baseline data from the EXPLORE Study. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:926, 932. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblin BA, Husnik MJ, Colfax G, Huang Y, Madison M, Mayer K, Barresi PJ, Coates TJ, Chesney MA, Buchbinder S. Risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2006;20:731, 739. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216374.61442.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav Spec. 1995:80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, Thompson AL. Individual trajectories of substance use in lesbian, gay and bisexual youth and heterosexual youth. Addiction. 2009;104:974, 981. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02531.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKirnan DJ, Peterson PL. Alcohol and drug use among homosexual men and women: epidemiology and population characteristics. Addict Behav. 1989;14:545, 553. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(89)90075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel L, Carrieri MP, Fugon L, Roux P, Aubin HJ, Lert F, Obadia Y, Spire B, Grp VS. Harmful alcohol consumption and patterns of substance use in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretrovirals (ANRS-EN12-VESPA Study): relevance for clinical management and intervention. AIDS Care. 2010;22:1136, 1145. doi: 10.1080/09540121003605039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimiaga MJ, Noonan E, Donnell D, Safren SA, Koenen KC, Gortmaker S, O'Cleirigh C, Chesney MA, Coates TJ, Koblin BA, Mayer KH. Childhood sexual abuse is highly associated with HIV risk-taking behavior and infection among MSM in the EXPLORE Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:340, 348. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a24b38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Muthén LK. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:882, 891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS. Analyzing Developmental Trajectories: A Semiparametric, Group-Based Approach. Psychol Methods. 1999;4:139, 157. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Ryan DT, Greene GJ, Garofalo R, Mustanski B. Prevalence and patterns of smoking, alcohol use, and illicit drug use in young men who have sex with men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;141:65, 71. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oesterle S, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Guo J, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. Adolescent heavy episodic drinking trajectories and health in young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65:204, 212. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrow DG, Stall RC, Jantz I, Berona J, Herrick A, Carrico A, Swartz J, Study LTEMU Predictors of long-term trajectories (2003-2010) of sex-drug and heavy alcohol (SDA) use among MSM. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15:194, 195. [Google Scholar]

- Paschall MJ, Flewelling RL, Faulkner DL. Alcohol misuse in young adulthood: effects of race, educational attainment, and social context. Subst Use Misuse. 2000;35:1485, 1506. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JC, Link BG. Controlling disease and creating disparities: a fundamental cause perspective. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60:27, 33. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plankey MW, Ostrow DG, Stall R, Cox C, Li X, Peck JA, Jacobson LP. The relationship between methamphetamine and popper use and risk of HIV seroconversion in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45:85, 92. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180417c99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plunk AD, Syed-Mohammed H, Cavazos-Rehg P, Bierut LJ, Grucza RA. Alcohol consumption, heavy drinking, and mortality: rethinking the j-shaped curve. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:471, 478. doi: 10.1111/acer.12250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psych Meas. 1977;1:385, 401. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson L, Sherman SG, Kerr T. Employment amongst people who use drugs: a new arena for research and intervention? Int J Drug Policy. 2012;23:3, 5. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Babor T, Rehm J. Alcohol and public health. Lancet. 2005;365:519, 530. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17870-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Components of depressed mood in married men and women. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies' Depression Scale. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;119:997, 1004. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander PM, Cole SR, Stall RD, Jacobson LP, Eron JJ, Napravnik S, Gaynes BN, Johnson-Hill LM, Bolan RK, Ostrow DG. Joint effects of alcohol consumption and high-risk sexual behavior on HIV seroconversion among men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2013;27:815, 823. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835cff4b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staff J, Patrick ME, Loken E, Maggs JL. Teenage alcohol use and educational attainment. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69:848, 858. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stall R, Paul JP, Greenwood G, Pollack LM, Bein E, Crosby GM, Mills TC, Binson D, Coates TJ, Catania JA. Alcohol use, drug use and alcohol-related problems among men who have sex with men: the Urban Men's Health Study. Addiction. 2001;96:1589, 1601. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961115896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiede H, Valleroy LA, Mackellar DA, Celentano DD, Ford WL, Hagan H, Koblin B, LaLota M, McFarland W, Shehan D, Torian LV, Young Men's Survey Study Group Regional patterns and correlates of substance use among young men who have sex with men in 7 US urban areas. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1915, 1921. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.11.1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin K, Davey-Rothwell M, Yang C, Siconolfi D, Latkin C. An examination of associations between social norms and risky alcohol use among African American men who have sex with men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;134:218, 221. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Nelson TF. Binge drinking and the American college student: what's five drinks? Psychol Addict Behav. 2001;15:287, 291. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Costa MV, Odunlami AO, Mohammed SA. Moving upstream: how interventions that address the social determinants of health can improve health and reduce disparities. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14:S8–S17. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000338382.36695.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CF, Kipke MD, Weiss G. Risk factors for alcohol use, frequent use, and binge drinking among young men who have sex with men. Addict Behav. 2008;33:1012, 1020. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf SE, Maisto SA. Alcohol use and risk of HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:757, 782. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9354-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf-King SE, Neilands TB, Dilworth SE, Carrico AW, Johnson MO. Alcohol use and HIV disease management: The impact of individual and partner-level alcohol use among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2014;26:702, 708. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.855302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.