Abstract

The incidence of osteoporosis-related fractures in Asian countries is steadily increasing. Optimizing osteoporosis treatment is especially important in Japan, where the rate of aging is increasing rapidlyelderly population is increasing rapidly and life expectancy is among the longest in the world. There are several therapies currently available in Japan for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis, each with a unique risk/benefit profile. A novel selective estrogen receptor modulator, bazedoxifene (BZA), was recently approved for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis in Japan. Results from a 2-year, phase 2 trial in postmenopausal Japanese women showed that BZA significantly improved lumbar spine and total hip bone mineral density compared with placebo, while maintaining endometrial and breast safety, consistent with results from 2 global, phase 3 trials including a 2-year osteoporosis prevention study and a 3-year osteoporosis treatment study. In the pivotal 3-year treatment study, BZA significantly reduced the incidence of new vertebral fractures compared with placebo; in a post hoc analysis of a subgroup of women at higher risk of fractures, BZA significantly reduced the risk of nonvertebral fractures compared with placebo and raloxifene. A 2-year extension of the 3-year treatment study demonstrated the sustained efficacy of BZA over 5 years of treatment. BZA was generally safe and well tolerated in these studies. In a “super-aging” society such as Japan, long-term treatment for postmenopausal osteoporosis is a considerable need. BZA may be considered as a first choice for younger women anticipating long-term treatment, and also an appropriate option for older women who are unable or unwilling to take bisphosphonates.

Keywords: Bazedoxifene, Fracture, Japan, Osteoporosis, Selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM)

Introduction

Osteoporosis is an asymptomatic, skeletal disease characterized by decreased bone mineral density (BMD), which is associated with an increased risk of fractures [1]. Osteoporosis disproportionately affects postmenopausal women, in whom estrogen deficiency can accelerate the loss of bone mass and cause deterioration of bone quality [2]. Osteoporosis-related fractures can lead to increased morbidity and mortality and can also result in significant costs to the healthcare system [3–5]. An estimated 200 million women worldwide are affected by osteoporosis [6], with the prevalence increasing with age from 4 % in women aged 50 to 59 years to 52 % in women >80 years of age [7]. Thus, postmenopausal osteoporosis is a global health concern and the availability of effective and safe treatments for postmenopausal osteoporosis is an important issue.

In Japan, there is an increasing awareness of the interaction between certain “lifestyle-related diseases” (e.g., type 2 diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease) and osteoporosis [8, 9]. For example, an increased fracture risk has been observed in patients with type 2 diabetes, and incident fractures have been shown to contribute to clinical deterioration in patients with lifestyle-related diseases. Further, lifestyle-related diseases such as type 2 diabetes and atherosclerosis have been shown to increase fracture risk independent of changes in BMD [9]. The relationship between lifestyle-related diseases and bone metabolism is thought to be due to increased oxidative stress, which promotes bone fragility in patients via various mechanisms; decreased osteoblast differentiation resulting in increased osteoblast/osteocyte cell death; accumulation of advanced glycation products in bone; and abnormalities in collagen cross-link formation in bone [8, 9]. Because recent studies have also suggested that certain therapies for lifestyle-related disease can affect bone metabolism, it is important for clinicians and patients to consider the associations between lifestyle-related diseases and osteoporosis when choosing appropriate treatment regimens.

The treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis is particularly important in Asia, where the elderly population is increasing rapidly [10]. The incidence of hip fractures in Asia is projected to increase by 520 % between 1990 and 2050; this increase would mean that in 2050, 45 % of all hip fractures that occur worldwide would take place in Asia, compared with 26 % in 1990 [10]. The growing burden of fractures is expected to have a greater impact in Japan, which has one of the longest life expectancies among developed countries [11]. In the 20-year period from 1985 to 2005, the number of citizens over 65 years of age increased from 12.4 million to 25.7 million people, and from 1987 to 2007, the number of fractures increased from 53,200 to 148,100 cases per year, with approximately 79 % of these fractures occurring in women [12]. The estimated number of patients in Japan with osteoporosis was 12.8 million in 2012 [8], and it is estimated that only 20 % of patients with osteoporosis are actively receiving treatment [13].

Along with the growing number of at-risk patients, Asian women may have a greater vertebral fracture risk relative to Caucasian women. In a large retrospective analysis derived from the Hong Kong Osteoporosis Study, the risk of vertebral fractures was shown to increase exponentially with age among women from Hong Kong and Japan and was nearly double the risk of Caucasian women 80 years and older [14]. In addition, projections indicate that hip fractures will increase throughout the world in the coming years, particularly in Asia. As a result, the socioeconomic impact of hip fractures will increase accordingly [10].

Several therapies are available for the prevention and/or treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Each has a unique risk/benefit profile and therefore may not be appropriate for all women. Here, we review the currently available agents for osteoporosis prevention and/or treatment, with a focus on bazedoxifene (BZA), a third-generation selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) approved in Japan in 2010. Data from preclinical and clinical studies of BZA are discussed, with an emphasis on the rationale for incorporating BZA into the osteoporosis treatment paradigm for postmenopausal Japanese women.

Current therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis

Currently available therapies in Japan for the prevention and/or treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis include vitamin D (used in the active form) and/or calcium supplementation, bisphosphonates, hormone therapy, eel calcitonin, parathyroid hormone (PTH), denosumab, and SERMs. The efficacy and safety of these therapies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of efficacy and safety for current therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis

| Therapy | Efficacy | Safety |

|---|---|---|

| Active vitamin D | • Increases in lumbar spine and total hip BMD [25]; reduces risk of vertebral fractures and wrist fractures [27] | • Transient hypercalcemia [25] |

| Bisphosphonates | • Reduces vertebral and nonvertebral fracture risk [28–30] |

• Short-term: acute phase reaction, acute renal failure, and gastrointestinal and esophageal irritation for oral formulations [15, 31] |

| Calcium Hormone therapy |

• Reduces nonvertebral fracture risk in combination with vitamin D [102, 103] |

• Increased risk of cardiovascular disease [104] |

| ET | • Reduces bone loss and fracture risk [49] | • Increased risk of stroke and VTEs [51] |

| EPT | • Reduces bone loss and fracture risk [48] |

• Increased risk of stroke, VTEs, and breast cancer [52] |

| Calcitonin | Improves lumbar spine BMD [105, 106] | • Nausea, vomiting, dizziness, leg cramps, hot flushes, and inflammation/irritation at administration site [107] |

| PTH | • Reduces vertebral and nonvertebral fracture risk [61, 62] | • Nausea, headache, dizziness, leg cramps, abdominal discomfort, and vomiting [61, 62] |

| Denosumab | • Reduces vertebral, nonvertebral, and hip fracture risk [67] | • Atypical fractures, delayed fracture healing, and ONJ [68] |

| SERMs | ||

| RLX | • Reduces bone loss and vertebral, but not nonvertebral, fracture risk [70–72] | • Increased incidence of hot flushes, leg cramps, VTEs, and fatal stroke [74, 108, 109] |

| LAS | • Reduces vertebral and nonvertebral fracture risk [75] |

• Increased incidences of hot flushes and leg cramps [75] • Increased rates of AEs related to the reproductive tract and number of diagnostic uterine procedures [76] |

| BZA | • Reduces bone loss and vertebral fracture risk; reduces nonvertebral fracture risk in women at high risk of fracture [89, 91, 93, 95, 96] |

• Increased incidences of hot flushes, leg cramps, and venous thromboembolic events [88–90, 93] • No evidence of endometrial or breast stimulation [87, 90, 92, 98] |

ET estrogen therapy, VTE venous thromboembolic event, EPT estrogen-progestin therapy, PTH parathyroid hormone, AE adverse event, ONJ osteonecrosis of the jaw, SERM selective estrogen receptor modulators, RLX raloxifene, LAS lasofoxifene, BZA bazedoxifene

Calcium supplementation and vitamin D

Sufficient dietary intake of calcium and vitamin D is known to be important for bone health [15]. Calcium supplementation alone has been shown to reduce bone loss in postmenopausal women [16, 17]. Calcium supplementation (1,000 mg) plus vitamin D (400 IU) has been shown to preserve total hip BMD compared with placebo (p < 0.001 at 3 and 6 years; p = 0.01 at 9 years) in generally healthy, postmenopausal women enrolled in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trial [18]. Over a mean of 7 years of follow-up, the incidence of hip fracture was not significantly reduced in the overall study population; however, among a subset of women who were >80 % adherent to study medication, calcium supplementation plus vitamin D was associated with a 29 % (hazard ratio [HR], 0.71; 95 % confidence interval [CI], 0.52–0.97) reduction in hip fracture incidence compared with placebo. The effects of vitamin D in reducing fracture risk have been shown to be dose-dependent; a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials in postmenopausal women showed a 26 % reduction in hip fracture (pooled relative risk [RR], 0.74; 95 % CI, 0.61–0.88) and a 23 % reduction in any nonvertebral fracture (pooled RR, 0.77; 95 % CI, 0.68–0.87) for doses of 700 to 800 IU per day compared with placebo, whereas no significant reductions in hip or nonvertebral fractures (pooled RR of 1.15 and 1.03, respectively) were observed with a dose of 400 IU per day [19]. However, vitamin D3 supplementation has not been found to correlate with calcium absorption [20].

The mean calcium and vitamin D intake in Asian countries such as Japan, China, and Korea are considerably lower than USA and European countries [21]. In the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the mean calcium intake among Korean adults was generally low (mean 485 mg/day) [21]. Low calcium intake was associated with elevated PTH and lower femoral neck BMD. In turn, as dietary calcium intake, calcium/phosphorus product, and/or serum vitamin D levels decreased, the risk for osteoporosis was significantly increased [22]. Calcium intake of ≥668 mg/d is recommended to effectively influence serum PTH and BMD in order to maintain bone mass [21]. In a large cross-sectional study of Japanese women, the risk of bone fracture was associated with low bone mass. In addition, dieting behaviors and associated poor lifestyle choices also impacted bone fracture risk [23]. Because traditional Asian diets are low in calcium, calcium and vitamin D supplementation may be a necessary component of bone health in this region of the world.

In Japan, active vitamin D derivatives (e.g., calcitriol, alfacalcidol) are commonly used in the treatment of osteoporosis [8, 24]. Early studies with the active vitamin D3 compound, eldecalcitol (ED-17) demonstrated increases in lumbar spine and total hip BMD and improvements in bone remodeling balance compared with native vitamin D in patients with osteoporosis [25, 26]. More recently, a 3-year, randomized, superiority study in patients (>95 % women) with osteoporosis compared eldecalcitol with alfacalcidol, a vitamin D analogue shown to positively affect BMD in postmenopausal women [27]. In this study, eldecalcitol was associated with a reduced risk of vertebral fractures, as well as increased BMD and decreased bone turnover markers compared with alfacalcidol at 3 years. Eldecalcitol was also associated with a marked reduction in wrist fractures (71 %) at 3 years, and similar safety profiles were observed among eldecalcitol and alfacalcidol treatment groups [26, 27]. Eldecalcitol was approved for treatment of osteoporosis in Japan in 2011.

Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonates are antiresorptive agents with established efficacy in reducing the risk of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures and are generally considered to be the first-line therapy for postmenopausal osteoporosis [15]. Bisphosphonates are available in Japan as oral formulations (including alendronate, minodronate, and risedronate) and as an intravenous injection (ibandronate). Studies have shown reductions in the risk of vertebral fractures of 39–59 % for oral bisphosphonates and reductions in nonvertebral fractures of 20–37 % have also been observed for alendronate and risedronate [28–30]. However, bisphosphonates have been associated with some short-term safety concerns, including acute phase reactions (transient, flu-like illness), acute renal failure, and gastrointestinal and esophageal irritation for oral formulations [15, 31]. In addition, long-term bisphosphonate treatment may be associated with the development of atypical fractures, such as low-impact subtrochanteric stress fractures, with the risk increasing with duration of therapy [32, 33]. In general, the safety profile of bisphosphonates in Japan is considered to be similar to Western populations. However, the exact incidence of atypical fracture with long-term treatment has not been determined. Osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) is a significant concern with bisphosphonate therapy. In a retrospective cohort study conducted by the Japanese Society of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, 39.5 % of patients diagnosed with ONJ had received an oral bisphosphonate [34].

There are several preparations of bisphosphonates available in Japan including oral formulations for daily, weekly or monthly administration, and nonoral formulations. Intravenous ibandronate has recently become available. The recommended doses of many bisphosphonates in Japan are half of the standard doses in Western countries. The relatively smaller body size and fairly higher incidence of upper gastrointestinal disorders [35] is considered to reduce the tolerability for bisphosphonate treatment in the Japanese population. Despite lower doses, increases in BMD in Japanese subjects in clinical trials were similar to those observed in subjects from Western countries in global studies where full dose treatments were administered [36].

Oral bisphosphonates also have an inconvenient dosing regimen that may contribute to poor adherence and high rates of therapy discontinuation [37–39]. A Taiwanese retrospective analysis of adherence/persistence with bisphosphonate treatment showed that 50 % of the subjects was nonadherent at 3 months and only approximately 30 % of subjects remained adherent at 1 year [40]. Adherence and compliance to bisphosphonate treatment is a considerable confounder of fracture risk. In a large retrospective analysis, the metric medication possession ratio of more than 80 % was associated with a lower probability of fracture [41].

To aid in compliance, alendronate is formulated for daily (5 mg) and weekly (35 mg) administration in tablet form, as a weekly administration in jelly form (35 mg), and as a once-monthly (900 μg) intravenous injection. Risedronate is available as a 2.5 mg/day, 17.5 mg/week, or 75 mg/month tablet. Minodronate, a nitrogen-containing bisphosphonate, is an example of a compound available in both daily (1 mg) and monthly (50 mg) formulations. Both the daily and monthly formulations of minodronate have been found to increase BMD and reduce fracture risk [30, 42], and have effects on BMD similar to alendronate [43]. Use of the once-monthly 50 mg minodronate dose has been found to increase treatment adherence among Japanese patients previously using daily or weekly bisphosphonates [44].

Recent studies indicate that the efficacy of bisphosphonates in postmenopausal women is significantly reduced by vitamin D deficiency [45–47]. The Japan Osteoporosis Intervention Trial (JOINT-02) conducted by the Consortium on the Adequate Treatment of Osteoporosis evaluated fracture incidence in relation to baseline serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) levels in women with severe osteoporosis (N = 2,164; mean age, 76.6 years) [46]. In this study, approximately 85 % of the subjects was reported to have baseline 25(OH)D levels of <30 ng/mL. Lower 25(OH)D levels (<20 ng/mL) were associated with a higher incidence of nonvertebral weight-bearing bone fractures (HR, 3.42; 95 % CI, 1.04–11.31), despite receiving alendronate therapy [46]. Subgroup analyses indicated that combination therapy with a vitamin D analog such as alfacalcidol may reduce the risk of fractures in some patients. In a study of 210 postmenopausal women with low BMD receiving bisphosphonate therapy, women with a mean 25(OH)D ≥33 ng/mL were reported to have a 4.5-fold increase in the probability of a favorable response to bisphosphonates, and a 1-ng/mL decrease in 25(OH)D was associated with an approximately 5 % decrease in the probability of responding [45]. In another study of 120 postmenopausal women (mean age, 68.8 years) with osteoporosis receiving bisphosphonates, women with 25(OH)D >30 ng/mL displayed a significant increase in lumbar spine BMD (3.6 %) compared with women with 25(OH)D <30 ng/mL (0.8 %; p < 0.05); women with 25(OH)D <30 ng/mL demonstrated a 4-fold increase in the probability of an inadequate response [47]. Overall, these studies suggest that vitamin D deficiency can significantly impact the efficacy of bisphosphonates and support the use of vitamin D supplementation for osteoporosis patients.

Hormone therapy

Hormone therapy, in the form of estrogen therapy (ET) and combined estrogen-progestin therapy (EPT; for nonhysterectomized women), is primarily indicated for the treatment of menopausal symptoms, but also has demonstrated efficacy in preventing bone loss and reducing the risk of fractures [48–50]. In the WHI trial, ET reduced total fracture incidence by 29 % (HR, 0.71; 95 % CI, 0.64–0.80) and hip fracture incidence by 35 % (HR, 0.65; 95 % CI, 0.45–0.94) over a mean follow-up period of 7.1 years [49]; EPT reduced total fracture incidence by 24 % (HR, 0.76; 95 % CI, 0.69–0.83) and hip fracture incidence by 33 % (HR, 0.67; 95 %, 0.47–0.96) over 5.6 years of follow-up [48]. ET and EPT have been associated with increased risk of venous thromboembolic events (VTEs) and stroke [51, 52]. In addition, EPT has been associated with increased risk of breast cancer as well as some tolerability concerns, including irregular vaginal bleeding and breast pain [52–55].

ET and EPT are rarely used in Japan for the prevention and/or treatment of osteoporosis [24]. A community survey conducted in Japan in the 1990s showed that only 2.5 % of women aged 45 to 64 reported current use of hormone therapy and 6.3 % had previously used hormone therapy [56]. Currently, although CE, estradiol, and estriol are approved for use in Japan, estradiol and estriol are not recommended for reduction of fracture risk, and CE is not covered by public health insurance for the treatment of osteoporosis [8].

Calcitonin

Although several forms of calcitonin are available worldwide (salmon, eel, human, porcine), synthetic eel calcitonin is the most commonly used in Japan [57]. Among Japanese postmenopausal women, synthetic eel calcitonin, elcatonin, administered by weekly 20-unit intramuscular injections provided sustained lumbar BMD for 5 years [58]. Elcatonin has also been found to improve patient quality-of-life scores among Japanese women with vertebral fractures, possibly due to some of the analgesic effects of elcatonin [59].

PTH

PTH and its analogs are anabolic agents that stimulate bone formation; PTH is approved in Japan (given as a daily subcutaneous injection) for the treatment of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who are at high risk of fracture [8, 15]. Its cost compared to bisphosphonates (i.e., 15–20 times higher) may influence the choice of this treatment for osteoporosis. A once-weekly formulation is in development [60], with treatment limited to 18 months. PTH has been shown to reduce the risk of both vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with prior vertebral fractures. Treatment with PTH 1–34 (teriparatide) 20 or 40 μg reduced the risk of new vertebral fractures (RR, 0.35; 95 % CI, 0.22–0.55 and RR, 0.31; 95 % CI, 0.19–0.50, respectively) and new nonvertebral fragility fractures (RR, 0.47; 95 % CI, 0.25–0.88 and RR, 0.46; 95 % CI, 0.25–0.86, respectively) compared with placebo over a median follow-up period of 21 months [61]. Teriparatide has also been studied in Japan as a once weekly injection. The effectiveness and safety of a weekly subcutaneous injection of teriparatide 56.5 μg (200 IU) was assessed in a large, 72-week, phase 3 study (TOWER trial). Among healthy men and women (aged 65–95 years) who had 1 to 5 vertebral fractures with low BMD, the cumulative incidence of new morphometric vertebral fractures by Kaplan–Meier estimation was 3.1 % in the teriparatide group and 14.5 % in the placebo group (p < 0.01, log-rank test). In addition, weekly teriparatide significantly reduced the relative risk of a new morphometric fractures relative to placebo (RR, 0.20; 95 % CI, 0.09–0.45, p < 0.01) [62]. In a long-term, unblinded extension of the TOWER trial, patients sustained the reduction in fracture risk over a 1-year period (RR , 0.18; 95 % CI, 0.09–0.36, p < 0.05 relative to placebo) [63]. In the TOWER trial and others, weekly subcutaneous administration of teriparatide effectively improved serum bone turnover markers and BMD at the lumbar spine [62, 64]. In a subgroup analysis of the TOWER trial, significant fracture risk reductions were observed regardless of age, number and grade of prevalent vertebral fractures, bone turnover, and renal function [65].

Adverse events (AEs) associated with PTH include nausea, headache, dizziness, leg cramps, abdominal discomfort, and vomiting [61, 62]. PTH is generally reserved for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who are at high risk for fractures; PTH treatment is limited to a 24-month course in Japan [8].

Denosumab

Denosumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to the receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand, thereby inhibiting bone resorption by osteoclasts [66]. Denosumab was approved in Japan in 2013 for the treatment of osteoporosis. Two-year results from the DIRECT trial reported the effects of denosumab (60 mg subcutaneous injection every 6 months) on fracture risk in Japanese patients (N = 1,262; 95 % women) with osteoporosis [67]. In this phase 3 study of Japanese women aged 50 or older with osteoporosis and 1–4 prevalent vertebral fractures, treatment with denosumab for 24 months reduced the risk of new or worsening vertebral fractures by 65.7 %. The incidence of new or worsening vertebral fractures was less among women treated with denosumab vs placebo (3.6 vs 10.3 %, HR 0.343, 95 % CI 0.194–0.606, p = 0.0001) at 24 months [67]. Denosumab was also associated with significant increases in lumbar spine, total hip, femoral neck, and distal radius BMD compared with placebo (p < 0.0001 for all), as well as significant reductions in serum C-telopeptide (CTX) and bone alkaline phosphatase levels. In an open-label portion of the study, denosumab was compared with alendronate (35 mg weekly). BMD changes for alendronate were significantly lower compared with denosumab at the lumbar spine and total hip starting at 3 months, femoral neck at 12 and 24 months, and distal 1/3 radius at 18 months (all p < 0.05) [67]. The HR (95 % CI) for new vertebral fractures for denosumab relative to alendronate was 0.416 (0.180, 0.962, p = 0.034) indicating a superior fracture inhibition effect with denosumab. These results may also be explained by the relatively low dose of alendronate approved for use in Japan compared with other countries. Denosumab was generally well tolerated with an AE and safety profile similar to alendronate and placebo. No incidences of delayed fracture healing, atypical femoral fractures, or ONJ were reported [67]. Because of the potential for reduction in bone remodeling with denosumab, safety concerns include atypical fractures, delayed fracture healing, and ONJ [68]. Denosumab may also be associated with an increased risk of serious infections and is indicated for postmenopausal women at a high risk of fractures [68].

SERMs

SERMs are a novel class of agents that exhibit tissue-specific estrogen receptor agonist or antagonist activity [69]. An ideal SERM would retain the positive effects of estrogens on bone but have ER-antagonist or neutral effects in the uterus and breast. Currently, 3 SERMs have been approved for the prevention and/or treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis [15]. Raloxifene (RLX) is a second generation SERM approved in multiple countries, including Japan, for the prevention and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. BZA and lasofoxifene (LAS) are third generation SERMs approved in the European Union and Japan (BZA only) for the treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women who are at increased risk of fractures. These SERMs are discussed in greater detail below.

SERMs for postmenopausal osteoporosis

RLX

The efficacy of RLX was evaluated in the phase 3, Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) study in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis [70]. At 3 years, reduced incidence of new vertebral fractures was observed for RLX 60 mg (RR, 0.7; 95 % CI, 0.5–0.8) and 120 mg (RR, 0.5; 95 % CI, 0.4–0.7) compared with placebo. However, the incidence of nonvertebral fractures for both RLX groups combined was not reduced compared with placebo (RR, 0.9; 95 % CI, 0.8–1.1). Analysis of combined data from two studies in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis in Japan and China, respectively, showed significant decreases at 12 months in the incidence of new vertebral fractures for RLX 60 mg and RLX 60 and 120 mg combined compared with placebo (p = 0.01 and p = 0.002, respectively); significant reductions in any type of clinical fracture were also observed for the RLX 60 mg (RR, 0.17; 95 % CI, 0.04–0.75; p = 0.01) and RLX combined (RR, 0.11; 95 % CI, 0.03–0.51; p = 0.001) groups [71]. In a post-marketing surveillance study of long-term RLX treatment in postmenopausal Japanese women with osteoporosis, lumbar spine BMD was significantly improved from baseline with RLX 60 mg at 6, 12, 24, and 36 months (p < 0.001 for all) [72]. In a postmarketing observational study, Japanese patients naïve to RLX treatment were assessed on quality of life measures at baseline (before treatment), 8 weeks, and 24 weeks after treatment with RLX [73]. On the validated Japanese Osteoporosis Quality of Life Questionnaire, total scores increased significantly from baseline after 24 weeks (p < 0.001). Similar improvements in quality of life were seen on other measures, including the Short Form-8 and the European Quality of Life Instrument. A limitation of this study was that it did not have a control arm. RLX is associated with adverse effects including increased incidences of hot flushes, leg cramps, and VTEs [74].

LAS

The phase 3, Postmenopausal Evaluation and Risk-reduction with Lasofoxifene trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of LAS 0.25 and 0.5 mg in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis [75]. At 5 years, LAS 0.25 and 0.5 mg showed significant reductions in vertebral fracture risk of 31 % (HR, 0.69; 95 % CI, 0.57–0.83; p < 0.001) and 42 % (HR, 0.58; 95 % CI, 0.47–0.70; p < 0.001), respectively, compared with placebo. The risk of nonvertebral fractures was decreased by 24 % (HR, 0.76; 95 % CI, 0.64–0.91; p = 0.002) relative to placebo for LAS 0.5 mg, but not LAS 0.25 mg. Both doses of LAS were associated with increased incidences of hot flushes and leg cramps compared with placebo [75]. In addition, the rates of AEs related to the reproductive tract, including vaginal candidiasis, vaginal discharge, vaginal bleeding, endometrial hypertrophy, and uterine polyps, were significantly increased with both LAS doses compared with placebo [76]. Treatment with both LAS doses also increased the number of diagnostic uterine procedures performed, and LAS 0.25 mg showed increased rates of surgery for pelvic organ prolapse or urinary incontinence, compared with placebo.

BZA

BZA was selected for clinical development based on results from a stringent preclinical screening process to identify compounds with favorable effects on bone that did not stimulate the breast or uterus [77]. Findings from preclinical studies of BZA and clinical trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of BZA are discussed in the sections below.

Preclinical studies of BZA

BZA showed positive effects on bone in preclinical studies utilizing an ovariectomized (OVX) rat model of osteopenia. BZA was associated with significant increases in BMD at the proximal tibia over 6 weeks of treatment [78, 79] and at the lumbar spine and proximal femur over 52 weeks of treatment [80] compared with OVX control rats. In these studies, BZA was effective in maintaining bone mass at a 10-fold lower dose (0.3 mg/kg/day) than the effective dose for RLX [77]. In addition, trabecular core samples from the L4 vertebrae of BZA-treated OVX animals showed significantly greater resistance to compressive force compared with untreated OVX animals [79]. BZA does not appear to accumulate in significant amounts in bone relative to other organs in rat models [81].

BZA was not associated with endometrial or breast stimulation in preclinical studies. In immature and OVX rat models, BZA did not increase uterine wet weight compared with that in control animals [77, 78, 80], and histological analysis showed no endometrial hypertrophy or hyperplasia with BZA [77]. BZA has also been shown to completely inhibit increases in uterine wet weight induced by treatment with 17β-estradiol (E2) [82] or conjugated estrogens (CE) [83].

BZA treatment did not stimulate proliferation of MCF-7 breast tumor cells or end bud formation in the mammary gland of OVX mice [82]. Moreover, coadministration of BZA inhibited E2-stimulated proliferation of MCF-7 cells [77, 79] and more completely inhibited CE-induced stimulation of MCF-7 cell proliferation than RLX or LAS [84]. BZA also demonstrated better prevention of CE-induced breast stimulation and reduction of ductal tree complexity compared with RLX or LAS [83].

Clinical studies of BZA

Based on promising findings from the preclinical studies, BZA was selected for clinical development. The efficacy and safety of BZA have been evaluated in two global, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled phase 3 trials as well as a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose–response, phase 2 study in Japan (Table 2). The two phase 3 studies included a 2-year osteoporosis prevention study (N = 1,583) evaluating BZA 10, 20, or 40 mg compared with placebo or RLX 60 mg in healthy, postmenopausal women at risk for osteoporosis [85, 86], and a 3-year osteoporosis treatment study (N = 7,492) evaluating BZA 20 or 40 mg compared with placebo or RLX 60 mg in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis [87–89].

Table 2.

Summary of key safety findings for BZA

| Parameter | Global prevention study (N = 1,583) | Global treatment study (N = 7,492) | Japanese phase 2 study (N = 429) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall safety/tolerability | • Similar AE rates compared with placebo [85] | • Similar AE rates among groups [88, 90, 93] | • Similar AE rates among groups [94] |

| Cardiac events | • No cardiac safety concerns [85] | • Incidence was low and similar among groups [88, 90] | • Incidence was low and similar among groups [94] |

| Cerebrovascular events | • Incidence was low and similar among groups [85] | • Incidence was low and similar among groups [88, 90] | • Incidence was low and similar among groups [94] |

| VTEs | • Incidence was low and similar among groups [85] | • Higher incidences for BZA versus placebo [88, 90, 93] | • No cases reported [94] |

| Endometrial safety |

• No differences among groups in change in endometrial thickness [86] • No confirmed cases of endometrial carcinoma or hyperplasia [86] |

• No differences among groups in change in endometrial thickness [87, 90, 92] • Incidences of endometrial hyperplasia were low and similar among groups [87, 90, 92] |

• No differences among groups in change in endometrial thickness [94] • No cases of endometrial carcinoma or hyperplasia reported [94] |

| • Lower incidences of endometrial carcinoma with BZA versus placebo (overall p < 0.05) [90, 92] | |||

| Breast safety | • Incidence of breast-related AEs was low and similar among groups [86] | • Incidence of breast-related AEs was low and similar among groups [87, 90, 92] | • Incidence of breast-related AEs was low and similar among groups [94] |

| Other reproductive safety | • No other reproductive safety concerns [86] |

• Numerically higher incidence of ovarian carcinoma for BZA versus placebo (not statistically significant) [90, 92] |

• No other reproductive safety concerns [94] |

BZA bazedoxifene, AE adverse event, VTE venous thromboembolic event

Two 2-year extensions of the 3-year, core treatment study have been completed. During Extension I (years 4–5; N = 3,146), the RLX 60 mg arm was discontinued and subjects who received BZA 40 mg were transitioned to BZA 20 mg. Findings from Extension I are reported for BZA 20 mg and BZA 40/20 mg (subjects who transitioned from BZA 40 to 20 mg) compared with placebo at 5 years [90, 91]. All subjects who entered Extension II (years 6–7; N = 1,732) in the active treatment group continued to receive BZA 20 mg. Findings from Extension II are reported for all BZA-treated subjects (including those who were transitioned from BZA 40 to 20 mg during Extension I) compared with placebo at 7 years [92, 93]. In the phase 2 study in Japan (N = 429), the efficacy and safety of BZA 20 or 40 mg were assessed relative to placebo over 2 years of treatment in postmenopausal Japanese women with osteoporosis [94].

Global osteoporosis prevention study

The primary efficacy endpoint for the global osteoporosis prevention study was the percent change from baseline in BMD of the lumbar spine at 2 years. BZA 10, 20, and 40 mg showed significantly improved lumbar spine BMD at 2 years compared with placebo, with differences ± standard deviation [SD] compared with placebo in the mean percent change from baseline of 1.08 ± 0.28, 1.41 ± 0.28, and 1.49 ± 0.28, respectively (p < 0.001 for all) [85]. All BZA doses also showed significantly improved total hip BMD at 2 years compared with placebo (differences ± SD versus placebo in the mean percent change from baseline for BZA 10, 20, and 40 mg of 1.29 ± 0.21, 1.75 ± 0.21, and 1.60 ± 0.21, respectively; p < 0.001 for all). All BZA groups showed greater reductions from baseline in serum levels of bone turnover markers, osteocalcin (OC) and CTX, at 2 years compared with placebo (p < 0.001 for all).

The incidences of AEs, serious AEs, and study discontinuations due to AEs were similar among the BZA and placebo groups [85]. The incidence of hot flushes in the BZA groups was higher than for placebo, but similar to that for RLX 60 mg. There were no differences among the BZA and placebo groups in the incidences of cardiovascular events and VTEs. BZA treatment did not increase endometrial thickness from baseline and the mean endometrial thickness at 2 years was similar among the BZA and placebo groups [85, 86]. There were no cases of confirmed endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial carcinoma in the BZA groups, and the incidence of endometrial polyps was similar among groups. In addition, there were no differences between the BZA and placebo groups in the incidences of breast pain, breast carcinoma, and other gynecological AEs.

Global osteoporosis treatment study

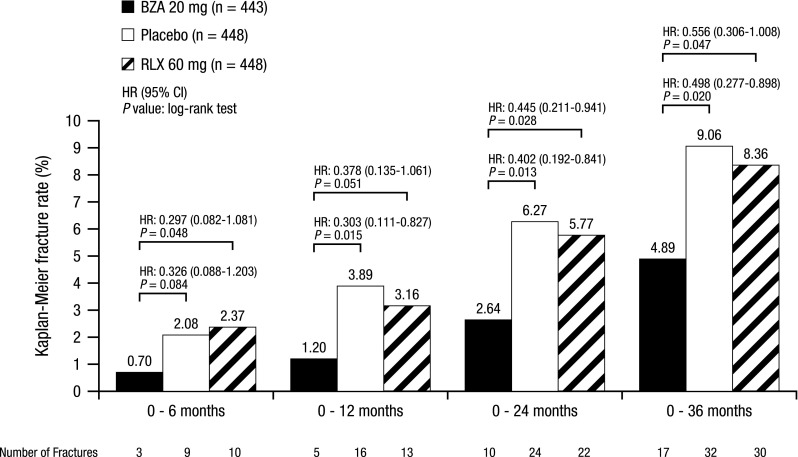

The primary efficacy endpoint for the global osteoporosis treatment study was the incidence of new vertebral fractures at 3 years. BZA 20 and 40 mg showed significantly lower incidences of new vertebral fractures at 3 years compared with placebo (Kaplan–Meier estimates of 2.3, 2.5, and 4.1 %, respectively; p < 0.05 for both vs placebo) [89]. BZA 20 and 40 mg decreased the risk of new vertebral fractures by 42 % (HR, 0.58; 95 % CI, 0.38–0.89) and 37 % (HR, 0.63; 95 % CI, 0.42–0.96), respectively, compared with placebo. The overall incidence of nonvertebral fractures was similar among groups; however, in a post hoc analysis of a subgroup of women at higher risk of fractures (N = 1,772), BZA 20 mg significantly reduced the risk of nonvertebral fractures by 50 % compared with placebo (p = 0.020) and by 44 % compared with RLX 60 mg (p = 0.047; Fig. 1) [89]. A re-analysis of the study findings based on combined data for BZA 20 and 40 mg using the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX®) showed a significant reduction in the risk of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women, with 10-year fracture probabilities of ≥6.9 % for vertebral fractures and ≥16 % for all clinical fractures (as assessed by FRAX®) compared with placebo. The treatment effect of BZA was greater with increasing probability of fracture [95, 96]. BZA 20 and 40 mg also showed significant improvements in lumbar spine and total hip BMD at 3 years (p < 0.001 for both vs placebo) and significantly lower OC and CTX levels at 1 year (p < 0.001 for both vs placebo) compared with placebo.

Fig. 1.

Incidence of nonvertebral fracture risk at 3 years in subjects at higher risk for fracturea (global osteoporosis treatment study [89]). Kaplan–Meier estimates of the rates of new nonvertebral fractures over 3 years of treatment. BZA bazedoxifene, RLX raloxifene, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval. aHigher-risk subgroup (femoral neck T-score −3.0 and/or ≥1 moderate or severe vertebral fracture or multiple mild vertebral fractures); N = 1,772

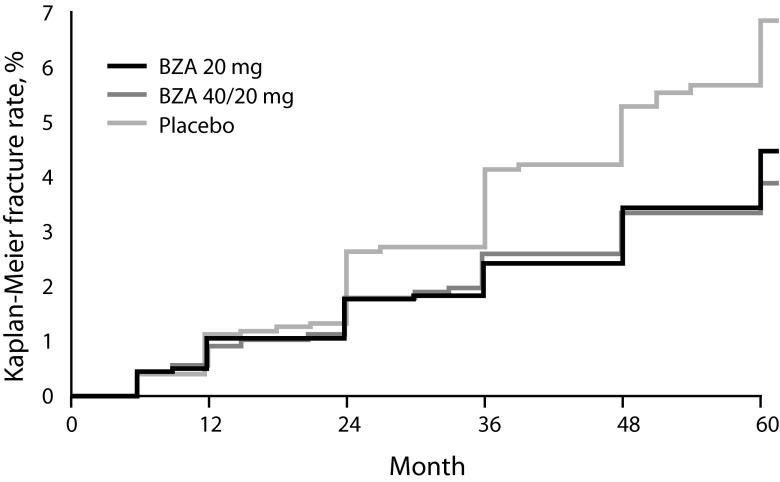

In Extension I of the study, BZA 20 and 40/20 mg reduced the incidence of new vertebral fractures by 35 % (p = 0.014) and 40 % (p = 0.005), respectively, relative to placebo at 5 years (Fig. 2) [91]. In a subgroup of women at higher risk of fractures, BZA 20 mg showed a 37 % reduction (p = 0.06) in the risk of nonvertebral fractures compared with placebo. Combined data for BZA 20 and 40/20 mg demonstrated a 34 % reduction in nonvertebral fracture risk (p = 0.049) versus placebo at 5 years. Both BZA groups showed significant improvements in BMD and decreases in bone turnover compared with placebo (p < 0.05 for all). Extension II of the study showed a sustained reduction of 37 % (p < 0.001) in the risk of new vertebral fractures at 7 years for BZA-treated subjects compared with those who received placebo [93]. Because the RLX treatment arm was discontinued during Extension I of the study, the effects of RLX on prevention of new vertebral fractures compared with BZA is limited to 3 years of treatment [89].

Fig. 2.

Cumulative incidence of new vertebral fractures at 5 years (Global osteoporosis treatment study [91]). Reprinted from Silverman SL et al. (2012) Sustained efficacy and safety of bazedoxifene in preventing fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results of a 5-year, randomized, placebo-controlled study Osteoporos Int 23: 351–363, Figure 2, with kind permission from Springer Science and Business Media

Overall, BZA treatment was associated with a favorable safety and tolerability profile over 7 years, with incidences of treatment-emergent AEs, serious AEs, and discontinuations due to AEs that were similar between the BZA-treated and PBO groups [88–90, 93]. Consistent with findings for other SERMs [74, 75], BZA treatment was associated with increased incidences of hot flushes, leg cramps, and VTEs compared with placebo; there were no differences among groups in the incidences of cardiac or cerebrovascular AEs and there were no incidents of ONJ. Of note is that Asians have a much lower risk of developing VTE than non-Asians [97] and have a higher incidence of bisphosphonate-related ONJ [34], both of which may make Asian postmenopausal women appropriate candidates for SERM treatment.

There was no evidence of endometrial or breast stimulation with BZA over 7 years of treatment [87, 90, 92]. Changes in endometrial thickness were minimal and incidences of endometrial hyperplasia were low and similar among groups; BZA showed lower rates of endometrial carcinoma compared with placebo (p < 0.05). Incidences of breast carcinoma and other breast-related AEs were similar among the BZA and PBO groups over 7 years. In a retrospective, ancillary study evaluating changes in mammographic breast density, no significant differences among groups were observed at 2 years [98].

Japanese phase 2 study

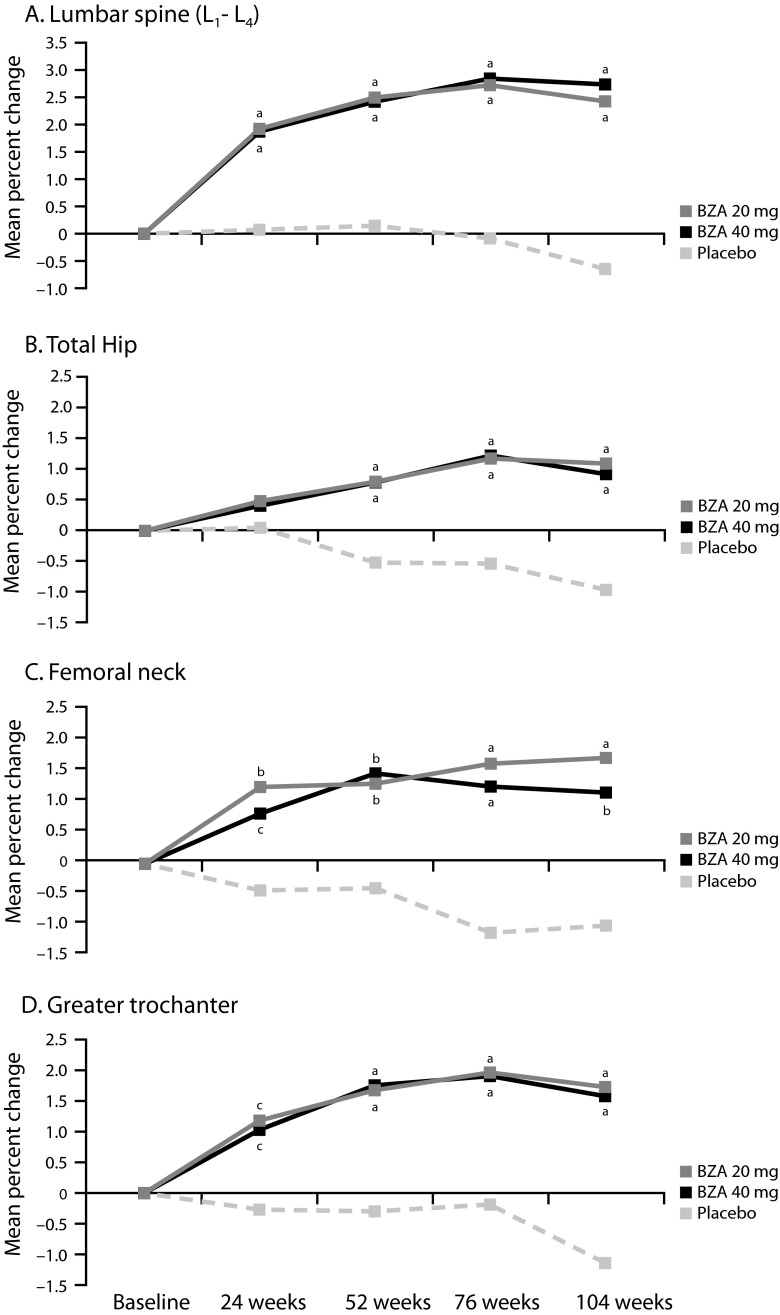

The primary efficacy endpoint for the Japanese phase 2 study was the percent change from baseline in lumbar spine BMD at 2 years. BZA 20 and 40 mg showed significant increases in mean percent change in lumbar spine BMD at 2 years compared with placebo, which showed a decrease from baseline (2.43, 2.74, and −0.65 %, respectively; p < 0.001; Fig. 3) [94]. Both BZA doses also showed significantly greater improvements compared with placebo in total hip BMD (1.10, 0.93, and −0.97 % for BZA 20 and 40 mg and placebo, respectively; p ≤ 0.001); similar improvements relative to placebo were observed with BZA at the femoral neck and greater trochanter (p ≤ 0.001 for all; Fig. 3). BZA 20 and 40 mg significantly reduced markers of bone turnover, including serum CTX, serum OC, serum N-telopeptide (NTX), and urinary NTX, compared with placebo (p < 0.01 for all). Both BZA doses showed lower incidences of vertebral fractures compared with placebo at 2 years (3.8, 2.4, and 4.7 %, respectively), but this difference was not statistically significant; incidences of nonvertebral fractures were similar among groups. However, it should be noted that this study was not powered to evaluate fracture risk.

Fig. 3.

Mean percent change from baseline in BMD response at the a lumbar spine, b total hip, c femoral neck, and d greater trochanter over 2 years (Japanese phase 2 study [94]). Reprinted from Itabashi A et al. (2011) Effects of bazedoxifene on bone mineral density, bone turnover, and safety in postmenopausal Japanese women with osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 26: 519–529, with permission from John Wiley and Sons. c2011 American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. BMD bone mineral density, BZA bazedoxifene. a p ≤ 0.001 vs placebo; b p < 0.01 vs placebo; c p < 0.05 vs placebo

BZA treatment was generally safe and well tolerated in this study, with no significant differences observed among groups in the incidences of treatment-emergent AEs, serious AEs, and discontinuations due to AEs [94]. Incidence of hot flushes was low across treatment groups, although BZA 20 mg was associated with higher rates of hot flushes compared with BZA 40 mg and placebo (overall p < 0.05). Rates of cardiac AEs were similar among groups and no VTEs were reported in any group. No significant differences were observed among groups in the change from baseline in endometrial thickness at 2 years or in incidences of reproductive or breast-related AEs.

A place for BZA in treating postmenopausal osteoporosis in Japan

BZA has been shown to have a favorable effect on lumbar spine and total hip BMD and bone turnover markers, while maintaining a favorable safety and tolerability profile in postmenopausal Japanese women over 2 years of treatment [94]. The findings from this Japanese phase 2 study are generally consistent with those observed in a global, 3-year osteoporosis treatment study [87–89]. Although reductions in fracture risk were not observed in the Japanese phase 2 study, which was not powered for assessment of fracture risk, two 2-year extensions of the 3-year osteoporosis treatment core study have demonstrated sustained efficacy of BZA in reducing the risk of vertebral fracture over 7 years of treatment [91, 93]. Notably, BZA reduced the risk of nonvertebral fracture compared with placebo and RLX in a subgroup of women at higher fracture risk. BZA was associated with a favorable overall safety and tolerability profile over 7 years, with no evidence of endometrial or breast stimulation, or other adverse effects on the reproductive tract [87, 90, 92].

The 2011 Japanese Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis state that BZA has an upregulatory effect on bone density (grade A), a preventive effect on vertebral fracture (grade A), a confirmed, preventive effect on nonvertebral fractures in a subgroup of women at high risk of fractures (grade B), and no reported preventive effect on hip fracture (grade C) [8]. Based on these guideline recommendations and in accordance with current global recommendations [99], BZA could potentially be an option for a) younger postmenopausal women who expect to be on long-term therapy and b) patients who are unable to take bisphosphonates or are concerned about the safety of long-term bisphosphonate therapy [31, 99]. Because some studies have shown sustained protection from vertebral fractures for up to 5 years following discontinuation of bisphosphonate therapy [100, 101], BZA may also be appropriate for women on long-term bisphosphonate therapy who are contemplating a “drug holiday.”

Conclusions

A variety of therapy options are currently available in Japan for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. These therapy options each have unique risk/benefit profiles and may meet the needs of a range of patients. SERMS have documented benefits compared to other osteoporosis treatments including fewer concerns with ONJ and atypical fractures often associated with long-term bisphosphonate treatment. Should excessive bone resorption occur with SERM treatment, prompt recovery will be expected by withdrawing treatment because SERMs do not accumulate appreciably in bone. BZA, in particular, has been shown to be effective in preventing fractures and improving BMD without stimulating the endometrium and breast over long-term treatment. Based on available evidence, BZA may be an appropriate option for younger postmenopausal women at increased risk of fracture and who expect to be on long-term therapy and postmenopausal women who cannot take bisphosphonates or are concerned about the safety of bisphosphonate treatment.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support for this manuscript was provided by Melissa Brunckhorst, PhD, at MedErgy and Linda Romagnano, PhD, of Peloton Advantage and was funded by Pfizer. The authors retained full editorial control over the content of the article.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Ohta reports advisory fee from Pola Pharma Inc. and research grants from Eisai Co., Ltd. and Astellas Pharma Inc. Dr. Solanki is a former employee of Pfizer.

Footnotes

Jit Solanki is a former employee of Pfizer.

Contributor Information

H. Ohta, Phone: +81 3 3402 5581, Email: ohtah@iuhw.ac.jp

J. Solanki, Phone: +447824 452200, Email: jit.solanki1@btinternet.com

References

- 1.National Osteoporosis Foundation (2010) Fast facts on osteoporosis. NOF web site. http://www.nof.org/node/40. Accessed 17 Nov 2011

- 2.Riggs BL, Khosla S, Melton LJ., III A unitary model for involutional osteoporosis: estrogen deficiency causes both type I and type II osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and contributes to bone loss in aging men. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:763–773. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.5.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atik OS, Gunal I, Korkusuz F. Burden of osteoporosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;443:19–24. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000200248.34876.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Center JR, Nguyen TV, Schneider D, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA. Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture in men and women: an observational study. Lancet. 1999;353:878–882. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)09075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riggs BL, Melton LJ., III The worldwide problem of osteoporosis: insights afforded by epidemiology. Bone. 1995;17:505S–511S. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Osteoporosis Foundation (2014) Facts and statistics about osteoporosis and its impact. IOF website http://www.iofbonehealth.org/facts-statistics. Accessed March 12, 2014.

- 7.Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, Calvo MS, Harris TB, Heyse SP, Johnston CC, Jr, Lindsay R. Updated data on proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:468–489. doi: 10.1007/s001980050093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orimo H, Nakamura T, Hosoi T, Iki M, Uenishi K, Endo N, Ohta H, Shiraki M, Sugimoto T, Suzuki T, Soen S, Nishizawa Y, Hagino H, Fukunaga M, Fujiwara S. Japanese 2011 guidelines for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis—executive summary. Arch Osteoporos. 2012;7:3–20. doi: 10.1007/s11657-012-0109-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugimoto T, Fujiwara S, Hagino H, Hosoi T, Inaba M, Okazaki R, Saito M, Shiraki M, Takeuchi Y, Yamaguchi T. Clinical practice guide on fracture risk in lifestyle-related diseases. Tokyo: Life Science Publishing Co., Ltd.; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA. World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. 1997;7:407–413. doi: 10.1007/PL00004148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagino H, Sakamoto K, Harada A, Nakamura T, Mutoh Y, Mori S, Endo N, Nakano T, Itoi E, Kita K, Yamamoto N, Aoyagi K, Yamazaki K. Nationwide one-decade survey of hip fractures in Japan. J Orthop Sci. 2010;15:737–745. doi: 10.1007/s00776-010-1543-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orimo H, Yaegashi Y, Onoda T, Fukushima Y, Hosoi T, Sakata K. Hip fracture incidence in Japan: estimates of new patients in 2007 and 20-year trends. Arch Osteoporos. 2009;4:71–77. doi: 10.1007/s11657-009-0031-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iki M. Epidemiology of osteoporosis in Japan. Clin Calcium. 2012;22:797–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bow CH, Cheung E, Cheung CL, Xiao SM, Loong C, Soong C, Tan KC, Luckey MM, Cauley JA, Fujiwara S, Kung AW. Ethnic difference of clinical vertebral fracture risk. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:879–885. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1627-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The North American Menopause Society Management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: 2010 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2010;17:25–54. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181c617e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawson-Hughes B, Dallal GE, Krall EA, Sadowski L, Sahyoun N, Tannenbaum S. A controlled trial of the effect of calcium supplementation on bone density in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:878–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199009273231305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shea B, Wells G, Cranney A, Zytaruk N, Robinson V, Griffith L, Ortiz Z, Peterson J, Adachi J, Tugwell P, Guyatt G. Meta-analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. VII. Meta-analysis of calcium supplementation for the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:552–559. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-7002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Gass M, Wallace RB, Robbins J, Lewis CE, Bassford T, Beresford SA, Black HR, Blanchette P, Bonds DE, Brunner RL, Brzyski RG, Caan B, Cauley JA, Chlebowski RT, Cummings SR, Granek I, Hays J, Heiss G, Hendrix SL, Howard BV, Hsia J, Hubbell FA, Johnson KC, Judd H, Kotchen JM, Kuller LH, Langer RD, Lasser NL, Limacher MC, Ludlam S, Manson JE, Margolis KL, McGowan J, Ockene JK, O’Sullivan MJ, Phillips L, Prentice RL, Sarto GE, Stefanick ML, Van HL, Wactawski-Wende J, Whitlock E, Anderson GL, Assaf AR, Barad D. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of fractures. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:669–683. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC, Wong JB, Giovannucci E, Dietrich T, Dawson-Hughes B. Fracture prevention with vitamin D supplementation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;293:2257–2264. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.18.2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallagher JC, Jindal P, Lynette MS. Vitamin D does not increase calcium absorption in young women: a randomized clinical trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:1081–1087. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joo NS, Dawson-Hughes B, Kim YS, Oh K, Yeum KJ. Impact of calcium and vitamin D insufficiencies on serum parathyroid hormone and bone mineral density: analysis of the fourth and fifth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES IV-3, 2009 and KNHANES V-1, 2010) J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:764–770. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong H, Kim EK, Lee JS. Effects of calcium intake, milk and dairy product intake, and blood vitamin D level on osteoporosis risk in Korean adults: analysis of the 2008 and 2009 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutr Res Pract. 2013;7:409–417. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2013.7.5.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tatsuno I, Terano T, Nakamura M, Suzuki K, Kubota K, Yamaguchi J, Yoshida T, Suzuki S, Tanaka T, Shozu M. Lifestyle and osteoporosis in middle-aged and elderly women: Chiba bone survey. Endocr J. 2013;60:643–650. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ12-0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujita T. Clinical guidelines for the treatment of osteoporosis in Japan. Calcif Tissue Int. 1996;59(suppl 1):S34–S37. doi: 10.1007/s002239900174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsumoto T, Miki T, Hagino H, Sugimoto T, Okamoto S, Hirota T, Tanigawara Y, Hayashi Y, Fukunaga M, Shiraki M, Nakamura T. A new active vitamin D, ED-71, increases bone mass in osteoporotic patients under vitamin D supplementation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:5031–5036. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsumoto T. Osteoporosis treatment by a new active vitamin D3 compound, eldecalcitol, in Japan. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2012;10:248–250. doi: 10.1007/s11914-012-0116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumoto T, Ito M, Hayashi Y, Hirota T, Tanigawara Y, Sone T, Fukunaga M, Shiraki M, Nakamura T. A new active vitamin D3 analog, eldecalcitol, prevents the risk of osteoporotic fractures—a randomized, active comparator, double-blind study. Bone. 2011;49:605–612. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wells G, Cranney A, Peterson J, Boucher M, Shea B, Robinson V, Coyle D, Tugwell P (2008) Risedronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD004523 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Wells GA, Cranney A, Peterson J, Boucher M, Shea B, Robinson V, Coyle D, Tugwell P (2008) Alendronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD001155 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Matsumoto T, Hagino H, Shiraki M, Fukunaga M, Nakano T, Takaoka K, Morii H, Ohashi Y, Nakamura T. Effect of daily oral minodronate on vertebral fractures in Japanese postmenopausal women with established osteoporosis: a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1429–1437. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0816-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silverman S, Christiansen C. Individualizing osteoporosis therapy. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:797–809. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1775-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneider JP. Bisphosphonates and low-impact femoral fractures: current evidence on alendronate-fracture risk. Geriatrics. 2009;64:18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shane E, Burr D, Ebeling PR, Abrahamsen B, Adler RA, Brown TD, Cheung AM, Cosman F, Curtis JR, Dell R, Dempster D, Einhorn TA, Genant HK, Geusens P, Klaushofer K, Koval K, Lane JM, McKiernan F, McKinney R, Ng A, Nieves J, O’Keefe R, Papapoulos S, Sen HT, van der Meulen MC, Weinstein RS, Whyte M. Atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femoral fractures: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:2267–2294. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Urade M, Tanaka N, Furusawa K, Shimada J, Shibata T, Kirita T, Yamamoto T, Ikebe T, Kitagawa Y, Fukuta J. Nationwide survey for bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws in Japan. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:e364–e371. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naylor GM, Gotoda T, Dixon M, Shimoda T, Gatta L, Owen R, Tompkins D, Axon A. Why does Japan have a high incidence of gastric cancer? Comparison of gastritis between UK and Japanese patients. Gut. 2006;55:1545–1552. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.080358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakamura T, Nakano T, Ito M, Hagino H, Hashimoto J, Tobinai M, Mizunuma H. Clinical efficacy on fracture risk and safety of 0.5 mg or 1 mg/month intravenous ibandronate versus 2.5 mg/day oral risedronate in patients with primary osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;93:137–146. doi: 10.1007/s00223-013-9734-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boonen S, Vanderschueren D, Venken K, Milisen K, Delforge M, Haentjens P. Recent developments in the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis with bisphosphonates: enhanced efficacy by enhanced compliance. J Intern Med. 2008;264:315–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pasion EG, Sivananthan SK, Kung AW, Chen SH, Chen YJ, Mirasol R, Tay BK, Shah GA, Khan MA, Tam F, Hall BJ, Thiebaud D. Comparison of raloxifene and bisphosphonates based on adherence and treatment satisfaction in postmenopausal Asian women. J Bone Miner Metab. 2007;25:105–113. doi: 10.1007/s00774-006-0735-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tosteson AN, Grove MR, Hammond CS, Moncur MM, Ray GT, Hebert GM, Pressman AR, Ettinger B. Early discontinuation of treatment for osteoporosis. Am J Med. 2003;115:209–216. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00362-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soong YK, Tsai KS, Huang HY, Yang RS, Chen JF, Wu PC, Huang KE. Risk of refracture associated with compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate therapy in Taiwan. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:511–521. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-1984-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siris ES, Harris ST, Rosen CJ, Barr CE, Arvesen JN, Abbott TA, Silverman S. Adherence to bisphosphonate therapy and fracture rates in osteoporotic women: relationship to vertebral and nonvertebral fractures from 2 US claims databases. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:1013–1022. doi: 10.4065/81.8.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okazaki R, Hagino H, Ito M, Sone T, Nakamura T, Mizunuma H, Fukunaga M, Shiraki M, Nishizawa Y, Ohashi Y, Matsumoto T. Efficacy and safety of monthly oral minodronate in patients with involutional osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:1737–1745. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1782-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hagino H, Nishizawa Y, Sone T, Morii H, Taketani Y, Nakamura T, Itabashi A, Mizunuma H, Ohashi Y, Shiraki M, Minamide T, Matsumoto T. A double-blinded head-to-head trial of minodronate and alendronate in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Bone. 2009;44:1078–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ikeda S, Sakai A, Okimoto N, Teshima K, Arita S, Matsumoto H, Tsurukami H, Okazaki Y, Nagashima M, Fukuda F, Yoshioka T Patient preference and adherence to once-monthly oral minodronate in Japanese osteoporotic patients previously using daily or weekly bisphosphonates [abstract]. Presented at: Annual Congress of the European Calcified Tissue Society; May 18–21, 2013; Lisbon, Portugal

- 45.Carmel AS, Shieh A, Bang H, Bockman RS. The 25(OH)D level needed to maintain a favorable bisphosphonate response is >/=33 ng/ml. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:2479–2487. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1868-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Orimo H, Nakamura T, Fukunaga M, Ohta H, Hosoi T, Uemura Y, Kuroda T, Miyakawa N, Ohashi Y, Shiraki M. Effects of alendronate plus alfacalcidol in osteoporosis patients with a high risk of fracture: the Japanese Osteoporosis Intervention Trial (JOINT) - 02. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:1273–1284. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2011.580341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peris P, Martinez-Ferrer A, Monegal A, Martinez de Osaba MJ, Muxi A, Guanabens N. 25 hydroxyvitamin D serum levels influence adequate response to bisphosphonate treatment in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Bone. 2012;51:54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cauley JA, Robbins J, Chen Z, Cummings SR, Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, LeBoff M, Lewis CE, McGowan J, Neuner J, Pettinger M, Stefanick ML, Wactawski-Wende J, Watts NB. Effects of estrogen plus progestin on risk of fracture and bone mineral density: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;290:1729–1738. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.13.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jackson RD, Wactawski-Wende J, LaCroix AZ, Pettinger M, Yood RA, Watts NB, Robbins JA, Lewis CE, Beresford SA, Ko MG, Naughton MJ, Satterfield S, Bassford T. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen on risk of fractures and BMD in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: results from the women’s health initiative randomized trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:817–828. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wells G, Tugwell P, Shea B, Guyatt G, Peterson J, Zytaruk N, Robinson V, Henry D, O’Connell D, Cranney A. Meta-analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. V. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of hormone replacement therapy in treating and preventing osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:529–539. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-5002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, Bassford T, Beresford SA, Black H, Bonds D, Brunner R, Brzyski R, Caan B, Chlebowski R, Curb D, Gass M, Hays J, Heiss G, Hendrix S, Howard BV, Hsia J, Hubbell A, Jackson R, Johnson KC, Judd H, Kotchen JM, Kuller L, LaCroix AZ, Lane D, Langer RD, Lasser N, Lewis CE, Manson J, Margolis K, Ockene J, O’Sullivan MJ, Phillips L, Prentice RL, Ritenbaugh C, Robbins J, Rossouw JE, Sarto G, Stefanick ML, Van HL, Wactawski-Wende J, Wallace R, Wassertheil-Smoller S. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701–1712. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, Ockene J. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.The North American Menopause Society Estrogen and progestogen use in postmenopausal women: 2010 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2010;17:242–255. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181d0f6b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Archer DF, Pickar JH, Bottiglioni F. Bleeding patterns in postmenopausal women taking continuous combined or sequential regimens of conjugated estrogens with medroxyprogesterone acetate. Menopause Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:686–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hammar ML, van de Weijer P, Franke HR, Pornel B, von Mauw EM, Nijland EA. Tibolone and low-dose continuous combined hormone treatment: vaginal bleeding pattern, efficacy and tolerability. BJOG. 2007;114:1522–1529. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nagata C, Matsushita Y, Shimizu H. Prevalence of hormone replacement therapy and user’s characteristics: a community survey in Japan. Maturitas. 1996;25:201–207. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5122(96)01067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamauchi H, Suzuki H, Orimo H. Calcitonin for the treatment of osteoporosis: dosage and dosing interval in Japan. J Bone Miner Metab. 2003;21:198–204. doi: 10.1007/s00774-003-0409-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Iwamoto J, Takeda T, Ichimura S, Uzawa M. Effects of 5-year treatment with elcatonin and alfacalcidol on lumbar bone mineral density and the incidence of vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: a retrospective study. J Orthop Sci. 2002;7:637–643. doi: 10.1007/s007760200114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoh K, Uzawa T, Orito T, Tanaka K. Improvement of Quality of Life (QOL) in osteoporotic patients by elcatonin treatment: a trial taking the participants’ preference into account. Jpn Clin Med. 2012;3:9–14. doi: 10.4137/JCM.S8291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sugimoto T, Nakamura T, Nakamura Y, Isogai Y, Shiraki M. Profile of changes in bone turnover markers during once-weekly teriparatide administration for 24 weeks in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:1173–1180. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2516-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR, Prince R, Gaich GA, Reginster JY, Hodsman AB, Eriksen EF, Ish-Shalom S, Genant HK, Wang O, Mitlak BH. Effect of parathyroid hormone (1–34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1434–1441. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105103441904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nakamura T, Sugimoto T, Nakano T, Kishimoto H, Ito M, Fukunaga M, Hagino H, Sone T, Yoshikawa H, Nishizawa Y, Fujita T, Shiraki M. Randomized Teriparatide [human parathyroid hormone (PTH) 1–34] Once-Weekly Efficacy Research (TOWER) trial for examining the reduction in new vertebral fractures in subjects with primary osteoporosis and high fracture risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:3097–3106. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sugimoto T, Shiraki M, Nakano T, Kishimoto H, Ito M, Fukunaga M, Hagino H, Sone T, Kuroda T, Nakamura T. Vertebral fracture risk after once-weekly teriparatide injections: follow-up study of Teriparatide Once-Weekly Efficacy Research (TOWER) trial. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29:195–203. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.761956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yamamoto T, Tsujimoto M, Hamaya E, Sowa H. Assessing the effect of baseline status of serum bone turnover markers and vitamin D levels on efficacy of teriparatide 20 mug/day administered subcutaneously in Japanese patients with osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Metab. 2013;31:199–205. doi: 10.1007/s00774-012-0403-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nakano T, Shiraki M, Sugimoto T, Kishimoto H, Ito M, Fukunaga M, Hagino H, Sone T, Kuroda T, Nakamura T. Once-weekly teriparatide reduces the risk of vertebral fracture in patients with various fracture risks: subgroup analysis of the Teriparatide Once-Weekly Efficacy Research (TOWER) trial. J Bone Miner Metab. 2014;32:441–446. doi: 10.1007/s00774-013-0505-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cummings SR, San MJ, McClung MR, Siris ES, Eastell R, Reid IR, Delmas P, Zoog HB, Austin M, Wang A, Kutilek S, Adami S, Zanchetta J, Libanati C, Siddhanti S, Christiansen C. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:756–765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nakamura T, Matsumoto T, Sugimoto T, Hosoi T, Miki T, Gorai I, Yoshikawa H, Tanaka Y, Tanaka S, Sone T, Nakano T, Ito M, Matsui S, Yoneda T, Takami H, Watanabe K, Osakabe T, Shiraki M, Fukunaga M. Fracture risk reduction with denosumab in japanese postmenopausal women and men with osteoporosis: Denosumab fracture Intervention RandomizEd placebo Controlled Trial (DIRECT) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-4175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Prolia [package insert] (2013) Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA

- 69.McDonnell DP, Connor CE, Wijayaratne A, Chang CY, Norris JD. Definition of the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the tissue-selective agonist/antagonist activities of selective estrogen receptor modulators. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2002;57:295–316. doi: 10.1210/rp.57.1.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ettinger B, Black DM, Mitlak BH, Knickerbocker RK, Nickelsen T, Genant HK, Christiansen C, Delmas PD, Zanchetta JR, Stakkestad J, Gluer CC, Krueger K, Cohen FJ, Eckert S, Ensrud KE, Avioli LV, Lips P, Cummings SR. Reduction of vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis treated with raloxifene: results from a 3-year randomized clinical trial. Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) Investigators. JAMA. 1999;282:637–645. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nakamura T, Liu JL, Morii H, Huang QR, Zhu HM, Qu Y, Hamaya E, Thiebaud D. Effect of raloxifene on clinical fractures in Asian women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Metab. 2006;24:414–418. doi: 10.1007/s00774-006-0702-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Iikuni N, Hamaya E, Nihojima S, Yokoyama S, Goto W, Taketsuna M, Miyauchi A, Sowa H. Safety and effectiveness profile of raloxifene in long-term, prospective, postmarketing surveillance. J Bone Miner Metab. 2012;30:674–682. doi: 10.1007/s00774-012-0365-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yoh K, Hamaya E, Urushihara H, Iikuni N, Yamamoto T, Taketsuna M, Miyauchi A, Sowa H, Tanaka K. Quality of life in raloxifene-treated Japanese women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a prospective, postmarketing observational study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28:1757–1766. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.736860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Martino S, Disch D, Dowsett SA, Keech CA, Mershon JL. Safety assessment of raloxifene over eight years in a clinical trial setting. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:1441–1452. doi: 10.1185/030079905X61839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cummings SR, Ensrud K, Delmas PD, LaCroix AZ, Vukicevic S, Reid DM, Goldstein S, Sriram U, Lee A, Thompson J, Armstrong RA, Thompson DD, Powles T, Zanchetta J, Kendler D, Neven P, Eastell R. Lasofoxifene in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:686–696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goldstein SR, Neven P, Cummings S, Colgan T, Runowicz CD, Krpan D, Proulx J, Johnson M, Thompson D, Thompson J, Sriram U. Postmenopausal evaluation and risk reduction with lasofoxifene (PEARL) trial: 5-year gynecological outcomes. Menopause. 2011;18:17–22. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181e84bb4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Komm BS, Lyttle CR. Developing a SERM: stringent preclinical selection criteria leading to an acceptable candidate (WAY-140424) for clinical evaluation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;949:317–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb04039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kharode Y, Bodine PV, Miller CP, Lyttle CR, Komm BS. The pairing of a selective estrogen receptor modulator, bazedoxifene, with conjugated estrogens as a new paradigm for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and osteoporosis prevention. Endocrinology. 2008;149:6084–6091. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Komm BS, Kharode YP, Bodine PV, Harris HA, Miller CP, Lyttle CR. Bazedoxifene acetate: a selective estrogen receptor modulator with improved selectivity. Endocrinology. 2005;146:3999–4008. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Komm BS, Vlasseros F, Samadfam R, Chouinard L, Smith SY. Skeletal effects of bazedoxifene paired with conjugated estrogens in ovariectomized rats. Bone. 2011;49:376–386. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Prakash C, Johnson KA, Schroeder CM, Potchoiba MJ. Metabolism, distribution, and excretion of a next generation selective estrogen receptor modulator, lasofoxifene, in rats and monkeys. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:1753–1769. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.021808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Crabtree JS, Peano BJ, Zhang X, Komm BS, Winneker RC, Harris HA. Activity of three selective estrogen receptor modulators on hormone-dependent responses in the mouse uterus and mammary gland. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;287:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Peano BJ, Crabtree JS, Komm BS, Winneker RC, Harris HA. Effects of various selective estrogen receptor modulators with or without conjugated estrogens on mouse mammary gland. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1897–1903. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chang KC, Wang Y, Bodine PV, Nagpal S, Komm BS. Gene expression profiling studies of three SERMs and their conjugated estrogen combinations in human breast cancer cells: insights into the unique antagonistic effects of bazedoxifene on conjugated estrogens. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;118:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Miller PD, Chines AA, Christiansen C, Hoeck HC, Kendler DL, Lewiecki EM, Woodson G, Levine AB, Constantine G, Delmas PD. Effects of bazedoxifene on BMD and bone turnover in postmenopausal women: 2-yr results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-, and active-controlled study. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:525–535. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.071206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pinkerton JV, Archer DF, Utian WH, Menegoci JC, Levine AB, Chines AA, Constantine GD. Bazedoxifene effects on the reproductive tract in postmenopausal women at risk for osteoporosis. Menopause. 2009;16:1102–1108. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181a816be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Archer DF, Pinkerton JV, Utian WH, Menegoci JC, de Villiers TJ, Yuen CK, Levine AB, Chines AA, Constantine GD. Bazedoxifene, a selective estrogen receptor modulator: effects on the endometrium, ovaries, and breast from a randomized controlled trial in osteoporotic postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2009;16:1109–1115. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181a818db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Christiansen C, Chesnut CH, III, Adachi JD, Brown JP, Fernandes CE, Kung AW, Palacios S, Levine AB, Chines AA, Constantine GD. Safety of bazedoxifene in a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled Phase 3 study of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Silverman SL, Christiansen C, Genant HK, Vukicevic S, Zanchetta JR, de Villiers TJ, Constantine GD, Chines AA. Efficacy of bazedoxifene in reducing new vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from a 3-year, randomized, placebo-, and active-controlled clinical trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1923–1934. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.de Villiers TJ, Chines AA, Palacios S, Lips P, Sawicki AZ, Levine AB, Codreanu C, Kelepouris N, Brown JP. Safety and tolerability of bazedoxifene in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results of a 5-year, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:567–576. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Silverman SL, Chines AA, Kendler DL, Kung AW, Teglbjaerg CS, Felsenberg D, Mairon N, Constantine GD, Adachi JD. Sustained efficacy and safety of bazedoxifene in preventing fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results of a 5-year, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:351–363. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1691-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Palacios S, de Villiers TJ, Nardone FC, Levine AB, Williams R, Hines T, Mirkin S, Chines AA. Assessment of the safety of long-term bazedoxifene treatment on the reproductive tract in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results of a 7-year, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Maturitas. 2013;76:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Palacios S, Silverman S, Levine AB Long-term efficacy and safety of bazedoxifene in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results of a 7-year, randomized, placebo-controlled study [abstract 973]. Presented at: the International Menopause Society World Congress on Menopause; June 8–11, 2011; Rome Italy

- 94.Itabashi A, Yoh K, Chines AA, Miki T, Takada M, Sato H, Gorai I, Sugimoto T, Mizunuma H, Ochi H, Constantine GD, Ohta H. Effects of bazedoxifene on bone mineral density, bone turnover, and safety in postmenopausal Japanese women with osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:519–529. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A, McCloskey EV. Bazedoxifene reduces vertebral and clinical fractures in postmenopausal women at high risk assessed with FRAX. Bone. 2009;44:1049–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.McCloskey E, Johansson H, Oden A, Chines A, Kanis J. Assessment of the effect of bazedoxifene on non-vertebral fracture risk [abstract FR0376] J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24(suppl 1):S140. [Google Scholar]

- 97.White RH, Keenan CR. Effects of race and ethnicity on the incidence of venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2009;123(suppl 4):S11–S17. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(09)70136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Harvey JA, Holm MK, Ranganath R, Guse PA, Trott EA, Helzner E. The effects of bazedoxifene on mammographic breast density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Menopause. 2009;16:1193–1196. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181a7fb1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Palacios S, Christiansen C, Sanchez BR, Gambacciani M, Hadji P, Karsdal M, Lambrinoudaki I, Lello S, O’Beirne B, Romao F, Rozenberg S, Stevenson JC, Ben-Rafael Z. Recommendations on the management of fragility fracture risk in women younger than 70 years. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2012;28:770–786. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2012.679062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]