Abstract

Summary

The objective of this study was to describe the risk of fragility-related fractures in the 2 years following teriparatide initiation. In an administrative claims analysis of over 11,407 patients, approximately one in eight patients had a new or recurrent fragility-related fracture in the 2 years following teriparatide initiation.

Introduction

The objective of this study was to describe the risk of fragility-related fractures in the 2 years following the initiation of teriparatide in a real-world setting.

Methods

This retrospective study used data from the 2002 to 2011 MarketScan® Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Databases to identify patients 50 years and older with a diagnosis of osteoporosis (ICD-9-CM code 733.0x) who were initiating teriparatide. Patients were required to have continuous medical and pharmacy benefit coverage for the 12 months prior to and 24 months following teriparatide initiation (index event). Teriparatide treatment patterns (persistence and adherence) were described, as was the use of antiresorptive therapy. The primary study outcome was the presence of a new or recurring fragility fracture following the initiation of teriparatide.

Results

A total of 11,407 patients met the study criteria (mean age = 69.5, standard deviation = 10.6 years; 92.0 % female). One in four (25.6 %) patients had fragility fracture claims in the year prior to teriparatide initiation, of which 64.0 % were on existing antiresorptive therapy. Overall, 13.4 % (n = 1527) of patients had a new or recurrent fracture during the 2-year follow-up period. Forty-eight percent of patients on teriparatide treatment were considered persistent; fragility fractures were more common among patients nonpersistent with teriparatide (15.2 %) than among those persistent with teriparatide (11.4 %). A higher fracture rate (35.7 %) was observed in the cohort with previous fragility fracture then those without pre-index fractures (24 %).

Conclusion

More than 13.4 % of patients had new or recurrent fragility-related fractures during the 2 years following the initiation of teriparatide; these fractures were more in common in patients with pre-existing fractures and the patients who were nonpersistent with teriparatide.

Keywords: Antiresorptive, Claims, Fracture, Osteoporosis, Teriparatide, Treatment persistence

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a disease characterized by microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue and low bone mass [1] which increases the risk of fractures and results in significant morbidity, mortality, and financial burden [2, 3]. Although there are a number of available treatments for osteoporosis, many patients continue to fracture while on therapy or are unable to tolerate treatments [4, 5]. Antiresorptive agents, which include bisphosphonates, estrogen, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), calcitonin, and RANK-Ligand inhibitors (denosumab) are the backbone of current modern osteoporosis drug-related prevention and treatment strategies in combination with vitamin D, calcium, and other behavioral modifications involving diet, exercise, and tobacco and alcohol use. In most instances, 2–3 years of consistent drug treatment is necessary until a substantial reduction of non-vertebral fracture risk can be shown [6]. In addition, compliance for oral bisphosphonates is low, potentially resulting in reduced or limited fracture risk reduction as demonstrated in randomized clinical trials [7, 8]. Recombinant human PTH (teriparatide), a subcutaneously administered anabolic agent indicated for high-risk osteoporosis populations, has been developed to reduce the risk of osteoporosis-related fractures [9]. Teriparatide has been approved to treat osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and in men with hypogonadal or idiopathic osteoporosis who are at high risk for fracture [10]. It is a recommended treatment for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis [11]. One randomized trial of postmenopausal women who had an already fractured vertebra compared teriparatide at either 20 or 40 μg per day with placebo. After 21 months, 14 % of the women taking placebo had new vertebral fractures, as compared with 5 % of the women taking 20 μg of teriparatide and 4 % of the women taking 40 μg. Non-vertebral fractures were also statistically significantly lower in the teriparatide-treated group [12]. In a comparative trial against alendronate, bone density at the spine and femoral neck was greater after 12 months in the teriparatide-treated group and a lower incidence of vertebral fractures was observed [13]. However, similarly to what has been observed with antiresorptive agents, low adherence and persistence has been associated with higher fracture risk [15].

The objective of this study was to describe the risk of fragility-related fractures in the 2 years following the initiation of teriparatide, and in the context of teriparatide persistence and adherence. Employing more recent administrative claims data from 2002 to 2011 covering both commercially insured and Medicare supplemental patients, we analyzed fracture rates among patients following the initiation of teriparatide and stratified the analysis according to teriparatide treatment patterns, whether they had used antiresorptive agents, or had a fragility fracture in the 12 months prior to initiating teriparatide.

Materials and methods

Data source

This retrospective study used the 2002–2011 MarketScan® Commercial Claims (commercial) and Encounters Database and Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefit Database (Medicare) from Truven Healthcare Analytics. The Commercial and Medicare databases contain medical claims, pharmacy claims, and enrollment data for approximately 38 million covered lives in the working population and 3 millions retirees in 2010, respectively. Major data contributors include employers and health plans that cover employees and their dependents through a variety of insurance plan structures including fee-for-service, fully capitated, and partially capitated health plans (preferred provider organizations [PPOs] and health maintenance organizations [HMOs]). The Medicare database is representative of the national commercially insured population of those individuals who have both Medicare coverage and supplemental employer-sponsored coverage. The patient data used in this analysis was de-identified in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations, and therefore, the study was not subject to institutional review board approval.

Patient selection

Patients were initially selected if they had a claim for teriparatide between January 1, 2003 and June 30, 2009. The study index date was set based on the first observed teriparatide claim. Patients were further required to have at least 12 months continuous enrollment with pharmacy benefit preceding and 24 months following the study index date. The study end date was June 30, 2011. We chose 24 months of follow-up and implied treatment duration because teriparatide is recommended for lifetime use of no more than 24 months [16]. In order to confirm the presence of osteoporosis, patients must have had an osteoporosis diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] diagnosis code 733.0x) recorded on an inpatient facility claim or a non-diagnostic inpatient professional or outpatient claim, or received any of the following medications during the pre-index period: alendronate, ibandronate, risedronate, zoledronic acid, raloxifene, or denosumab. Patients were excluded from the analysis if they were under age 50 at the study index date or received teriparatide in the pre-index period, or had pre-existing Paget’s disease, osteogenesis imperfecta, hypercalcemia, cancer (excluding skin cancer), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), or pre-index period hormonal therapy, as these conditions or treatments may impact bone health and treatment.

Outcome measures

Fragility fractures were captured by the presence of qualified diagnosis for fractures of the hip, vertebra, femur, pelvis, clavicle, wrist/radius-ulna, humerus, patella, tibia-fibular, and ankle. Closed and pathological fractures on these sites were included as done in previously published study [17]. Fractures recorded from primary or secondary diagnoses from an inpatient facility claim or on a non-diagnostic inpatient professional or outpatient claim were considered “qualified.” We applied the algorithm developed by Song et al. [17] to differentiate new fracture, recurrent fracture, and continuum care of previous fracture.

Treatment cohorts

Fragility fracture incidence was evaluated during the entire 24-month post-index period for patients persistent and nonpersistent on teriparatide and those with pre-index fragility fractures or antiresorptive use. Antiresorptive agents consisted of alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate, zoledronic acid, raloxifene, and denosumab. Nonpersistence with teriparatide was defined as having a gap of 90 days or longer between prescriptions after the expected run out of the previous prescription. The run out for each prescription was defined using the days supply field on the outpatient pharmacy claim. Previous studies measuring bisphosphonates and teriparatide used allowable gaps from 30 to 90 days [14, 15, 18–20]. A 90-day gap in therapy was used to classify patients as nonpersistent. The number of days from teriparatide initiation to the start of a 90-day gap was reported to track persistence time. The presence of teriparatide restarts following a 90-day gap was captured, as was the number of days between the 90-day gap start and subsequent restart. Treatment adherence was measured by MPR, calculated based on the total number of days on medication divided by 730 days (assumption of intended treatment duration 24 months). Patient-level binary flags were created to indicate if the patients received concomitant antiresorptive therapy (i.e., on both teriparatide and antiresorptives for 45 days or longer), or switched from teriparatide to antiresorptives during the 24-month post-index period.

Analysis

Descriptive patient demographic and clinical characteristics were captured during 12-month pre-period and compared between patients with and without post-period fracture. Age, gender, region, primary payer (commercial versus Medicare supplement), insurance plan type, and insurance capitation status were reported. Clinical characteristics consisted of general health status measures such as the Deyo-Charlson comorbidity index (DCI) score and number of unique ICD-9-CM diagnoses, as well as prevalence of select comorbid conditions and fragility-related fracture during the pre-index period. Fragility fractures after teriparatide initiation, pre-teriparatide antiresorptive use, and pre-teriparatide fracture status were described. Teriparatide treatment patterns and the presence of fragility fractures following teriparatide initiation were compared between patients who were persistent and nonpersistent with teriparatide. Categorical measures were presented as counts and percentages. Continuous measures were presented as means and standard deviations. Statistical significance was tested using standard descriptive statistical test (i.e., t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables) for differences in demographic and clinical variables as well as study outcomes between relevant patient groups, p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Cumulative incidence curves were produced showing new or recurrent fractures and were stratified by treatment status (persistent versus nonpersistent with teriparatide), and baseline fracture risk (baseline fragility fracture and baseline antiresorptive use). A logistic regression model was fitted predicting a new or recurrent fracture, controlling for the demographic and clinical characteristics listed in Table 1, along with teriparatide persistence.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with osteoporosis who newly initiated teriparatide treatment by post-index fracture status

| Patient characteristics | Fracture patients | Non-fracture patients | p value | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/mean | Percent/SD | N/mean | Percent/SD | N/mean | Percent/SD | ||

| Total number of patients | 1527 | 13.4 % | 9880 | 86.6 % | 11,407 | 100 % | |

| Age (mean, SD) | 72.4 | 10.5 | 69.1 | 10.5 | <0.001 | 69.5 | 10.6 |

| Age range (N, %) | |||||||

| 50–54 | 88 | 5.8 % | 851 | 8.6 % | <0.001 | 939 | 8.2 % |

| 55–59 | 151 | 9.9 % | 1531 | 15.5 % | <0.001 | 1682 | 14.7 % |

| 60–64 | 158 | 10.3 % | 1393 | 14.1 % | <0.001 | 1551 | 13.6 % |

| 65–69 | 155 | 10.2 % | 1178 | 11.9 % | 0.045 | 1333 | 11.7 % |

| 70–79 | 544 | 35.6 % | 3032 | 30.7 % | <0.001 | 3576 | 31.3 % |

| 80+ | 431 | 28.2 % | 1895 | 19.2 % | <0.001 | 2326 | 20.4 % |

| Female (N, %) | 1412 | 92.5 % | 9084 | 91.9 % | 0.481 | 10,496 | 92.0 % |

| Medicare payer (N, %) | 1146 | 75.0 % | 6167 | 62.4 % | <0.001 | 7313 | 64.1 % |

| Capitated services (N, %) | 38 | 2.5 % | 379 | 3.8 % | 0.009 | 417 | 3.7 % |

| Insurance plan type (N, %) | |||||||

| Comprehensive | 789 | 51.7 % | 4469 | 45.2 % | <0.001 | 5258 | 46.1 % |

| Point of service | 63 | 4.1 % | 621 | 6.3 % | 0.001 | 684 | 6.0 % |

| HMO | 60 | 3.9 % | 623 | 6.3 % | <0.001 | 683 | 6.0 % |

| PPO | 588 | 38.5 % | 3957 | 40.1 % | 0.251 | 4545 | 39.8 % |

| Other/unknown | 27 | 1.8 % | 210 | 2.1 % | 0.362 | 237 | 2.1 % |

| Region (N, %) | |||||||

| Northeast | 124 | 8.1 % | 663 | 6.7 % | 0.043 | 787 | 6.9 % |

| North Central | 581 | 38.0 % | 3505 | 35.5 % | 0.051 | 4086 | 35.8 % |

| South | 590 | 38.6 % | 4354 | 44.1 % | <0.001 | 4944 | 43.3 % |

| West | 229 | 15.0 % | 1322 | 13.4 % | 0.086 | 1551 | 13.6 % |

| Unknown | 3 | 0.2 % | 36 | 0.4 % | 0.296 | 39 | 0.3 % |

| DCI (mean, SD) | 0.97 | 1.23 | 0.63 | 0.99 | <0.001 | 0.68 | 1.03 |

| Unique 3-digit ICD-9 codes (mean, SD) | 14.8 | 8.8 | 11.7 | 7.3 | <0.001 | 12.1 | 7.6 |

| Baseline comorbid conditions (N, %) | |||||||

| Abnormalities of the esophagus | 53 | 3.5 % | 436 | 4.4 % | 0.091 | 489 | 4.3 % |

| Active UGI ulcer | 28 | 1.8 % | 125 | 1.3 % | 0.072 | 153 | 1.3 % |

| Alcoholism | 6 | 0.4 % | 30 | 0.3 % | 0.563 | 36 | 0.3 % |

| Diabetes | 214 | 14.0 % | 915 | 9.3 % | <0.001 | 1129 | 9.9 % |

| Endocrine disease (excluding diabetes) | 69 | 4.5 % | 354 | 3.6 % | 0.072 | 423 | 3.7 % |

| GERD | 180 | 11.8 % | 1111 | 11.2 % | 0.533 | 1291 | 11.3 % |

| Renal insufficiency | 2 | 0.1 % | 61 | 0.6 % | 0.017 | 63 | 0.6 % |

| Liver disease | 26 | 1.7 % | 181 | 1.8 % | 0.725 | 207 | 1.8 % |

| Malabsorption syndrome | 6 | 0.4 % | 59 | 0.6 % | 0.324 | 65 | 0.6 % |

| Metabolic bone disease | 31 | 2.0 % | 257 | 2.6 % | 0.186 | 288 | 2.5 % |

| Nephritis | 12 | 0.8 % | 52 | 0.5 % | 0.206 | 64 | 0.6 % |

| Osteopenia | 137 | 9.0 % | 900 | 9.1 % | 0.862 | 1037 | 9.1 % |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 185 | 12.1 % | 706 | 7.1 % | <0.001 | 891 | 7.8 % |

| Thyroid disease | 222 | 14.5 % | 1319 | 13.4 % | 0.206 | 1541 | 13.5 % |

| Fragility-related fractures (N, %) | 544 | 35.6 % | 2376 | 24.0 % | <0.001 | 2920 | 25.6 % |

| Vertebral | 207 | 13.6 % | 1326 | 13.4 % | 0.886 | 1533 | 13.4 % |

| Hip | 107 | 7.0 % | 323 | 3.3 % | <0.001 | 430 | 3.8 % |

| Non-hip non-vertebral | 252 | 16.5 % | 793 | 8.0 % | <0.001 | 1045 | 9.2 % |

| Multiple fractures | 22 | 1.4 % | 65 | 0.7 % | 0.001 | 87 | 0.8 % |

| Antiresorptive use (N, %) | 1,003 | 65.7 % | 6302 | 63.8 % | 0.150 | 7305 | 64.0 % |

| Raloxifene use (N, %) | 205 | 13.4 % | 1357 | 13.7 % | 0.743 | 1562 | 13.7 % |

| Antiresorptive agent count (mean, SD) | 1.1 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.538 | 1.1 | 0.2 |

| Days on antiresorptives (mean, SD) | 209.7 | 102.3 | 219.0 | 100.9 | 0.001 | 217.7 | 101.1 |

| Antiresorptive MPR (mean, SD) | 0.73 | 0.26 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.004 | 0.75 | 0.25 |

The italicized values denote p < 0.001

Results

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

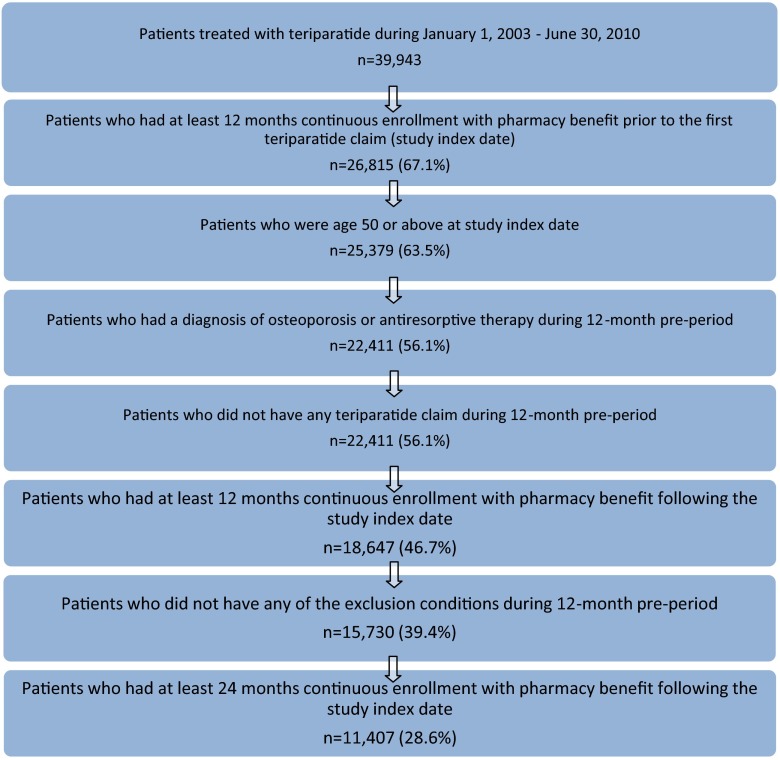

A total of 39,943 patients received at least one prescription for teriparatide between January 1, 2005 and June 30, 2010. Figure 1 shows the impact of each inclusion and exclusion criterion, resulting in a total of 11,047 patients meeting the final criteria. As shown in Table 1, the study patients were mostly female (92 %), with a mean age of 69.5 years, and 64 % were Medicare supplemental enrollees (versus fully commercially insured). The geographic region distribution in the study population was consistent with the geographic representation in the MarketScan Research Databases. There were several statistically significant differences between patients with and without post-index fragility fractures (Table 1). Patients with a fracture during follow-up were slightly older (72.4 versus 69.1 years, p < 0.001) and were more likely to have diabetes (14.0 versus 9.3 %, p < 0.001) and rheumatoid arthritis (12.1 versus 7.1 %, p < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Study sample

Overall, the study patients had a baseline average DCI score of 0.7. Patients with a post-index fracture had a significantly higher number of unique 3-digit ICD-9-CM diagnoses (14.8 versus 11.7, p < 0.001) and higher baseline DCI (0.97 versus 0.63, p < 0.001).

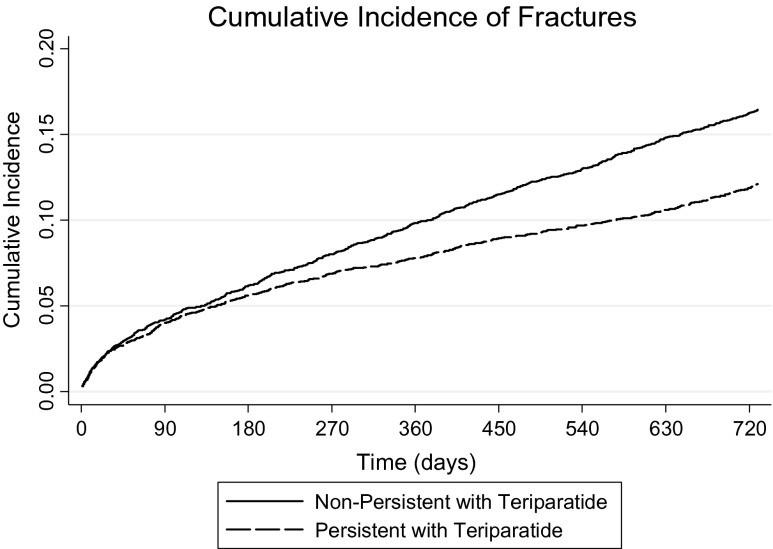

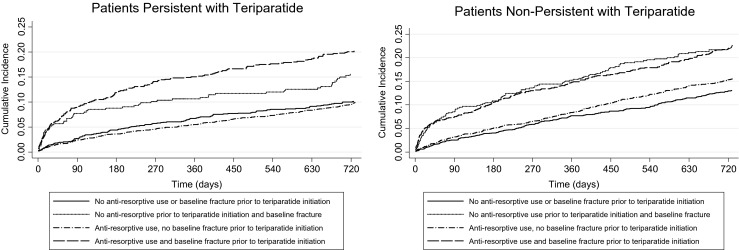

Post-period fragility-related fractures

Overall, 13.4 % of total patients had a new or recurrent fragility-related fracture during the 24 month follow-up period (Table 1). Figure 2 shows the cumulative incidence of new or recurrent fractures over the 24-month post-index period. Table 2 contains the baseline antiresorptive use and fragility fracture characteristics for patients with and without post-index fragility fractures, stratified by teriparatide persistence. Figure 3 contains eight cumulative incidence curves, showing fracture rates separately based on combinations of teriparatide persistence, baseline antiresorptive use, and baseline fragility-related fractures.

Fig. 2.

Cumulative incidence of new or recurring fractures among patients persistent and nonpersistent with teriparatide

Table 2.

Effect of previous fracture and antiresorptive use on fractures following initiation of teriparatide on patients that were persistent and nonpersistent with teriparatide

| Fracture patients | Non-fracture patients | p value | Overall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 1527 | N = 9880 | N = 11,407 | |||||

| N value | Percent | N value | Percent | N value | Percent | ||

| Persistent with teriparatide | 623 | 40.8 | 4835 | 48.9 | <0.001 | 5458 | 47.8 |

| Patients with baseline fracture | 234 | 37.6 | 1132 | 23.4 | <0.001 | 1366 | 25.0 |

| And with baseline antiresorptive use | 174 | 27.9 | 777 | 16.1 | <0.001 | 951 | 17.4 |

| And without baseline antiresorptive use | 60 | 9.6 | 355 | 7.3 | 0.514 | 415 | 7.6 |

| Patients without baseline fracture | 389 | 62.4 | 3703 | 76.6 | <0.001 | 4092 | 75.0 |

| And with baseline antiresorptive use | 264 | 42.4 | 2534 | 52.4 | <0.001 | 2798 | 51.3 |

| And without baseline antiresorptive use | 125 | 20.1 | 1169 | 24.2 | <0.001 | 1294 | 23.7 |

| Nonpersistent with teriparatide | 904 | 59.2 | 5045 | 51.1 | <0.001 | 5949 | 52.2 |

| Patients with baseline fracture | 310 | 34.3 | 1244 | 24.7 | <0.001 | 1554 | 26.1 |

| And with baseline antiresorptive use | 194 | 21.5 | 787 | 15.6 | <0.001 | 981 | 16.5 |

| And without baseline antiresorptive use | 116 | 12.8 | 457 | 9.1 | <0.001 | 573 | 9.6 |

| Patients without baseline fracture | 594 | 65.7 | 3801 | 75.3 | 0.749 | 4395 | 73.9 |

| And with baseline antiresorptive use | 371 | 41.0 | 2204 | 43.7 | 0.084 | 2575 | 43.3 |

| And without baseline antiresorptive use | 223 | 24.7 | 1597 | 31.7 | 0.121 | 1820 | 30.6 |

| Total | 1527 | 100.0 | 9880 | 100.0 | 11,407 | 100.0 | |

| Patients with baseline fracture | 544 | 35.6 | 2376 | 24.0 | <0.001 | 2920 | 25.6 |

| And with baseline antiresorptive use | 368 | 24.1 | 1564 | 15.8 | <0.001 | 1932 | 16.9 |

| And without baseline antiresorptive use | 176 | 11.5 | 812 | 8.2 | <0.001 | 988 | 8.7 |

| Patients without baseline fracture | 983 | 64.4 | 7504 | 76.0 | <0.001 | 8487 | 74.4 |

| And with baseline antiresorptive use | 635 | 41.6 | 4738 | 48.0 | <0.001 | 5373 | 47.1 |

| And without baseline antiresorptive use | 348 | 22.8 | 2766 | 28.0 | <0.001 | 3114 | 27.3 |

The italicized values denote p < 0.001

Fig. 3.

Cumulative fracture incidence following teriparatide initiation, stratified by teriparatide persistence, and baseline antiresorptive use or fracture

As shown in Table 2 and Fig. 3, patients with fragility fractures during the baseline period had the highest risk of new or recurrent fragility fractures during the post-index period, regardless of teriparatide persistence or baseline antiresorptive use. Among the 2920 patients with a baseline fracture, 544 patients (18.6 %) had a new or recurrent fragility fracture during the 24-month post-index period; among the 8487 patients without a baseline fracture, 983 patients (11.6 %) had a new or recurrent fragility fracture during the 24-month post-index period (Table 2).

Baseline fragility-related fracture and antiresorptive medication use and relationship to post index fractures

Overall, one in four (25.6 %) patients had a baseline fragility fracture (Table 1). A statistically significant greater proportion of patients with a baseline fragility fracture in the year prior to teriparatide initiation had a fragility fracture in the 2 years following teriparatide initiation (35.6 %) than patients without a baseline fragility fracture (24.0 %, p < 0.001). Overall, 13.4 % of patients had a vertebral fracture during baseline period, which was similar regardless of patient post-index fragility fracture status (Table 1). Patients with a hip fracture pre-index were more likely to have a post-index fragility fracture (7.0 versus 3.3 %, p < 0.001); similarly, patients with non-hip non-vertebral fractures pre-index were more likely to have a fragility fracture in the 2 years following teriparatide initiation (16.5 versus 8.0 %, p < 0.001) (Table 1). Overall, multiple fragility fractures were uncommon in the two years following teriparatide initiation (0.8 %) (Table 1). Overall, nearly two thirds of patients used an antiresorptive therapy prior to initiating teriparatide; baseline antiresorptive use was similar between patients with post-period fragility fractures and those without post-period fragility fractures (65.7 versus 63.8 %, p = 0.150) (Table 1).

Teriparatide treatment patterns

As shown in Table 3, over one half (52 %, n = 5,949) of patients had at least one gap of 90 days in their teriparatide use during the 24-month post-index period; these patients were classified as nonpersistent with teriparatide. The remaining 48 % who did not have a teriparatide gap of 90 days were classified as persistent with teriparatide. The MPR for the study patients was 0.62 (±0.33) over the entire 24-month post-index period (Table 3). Patients who were teriparatide persistent had a mean MPR of 0.85 (±0.11) for teriparatide during the entire 24-month post-index period, compared to 0.37 (±0.25) for the nonpersistent patients (Table 3). Prior to discontinuation, nonpersistent patients had an average teriparatide MPR of 0.88 (±0.16). Nearly one fifth (18.6 %) of non persistent patients restarted teriparatide after the first discontinuation.

Table 3.

Teriparatide treatment patterns

| Teriparatide MPR | N value | Percent | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teriparatide persistent patients (N, %) | 5458 | 47.8 | 0.89 | 0.11 |

| Teriparatide nonpersistent patients (N, %) | ||||

| During the 24-month target treatment duration | 5949 | 52.2 | 0.37 | 0.25 |

| While on persistent therapy with teriparatide | 5949 | 52.2 | 0.88 | 0.16 |

| During subsequent teriparatide therapy after teriparatide restart | 1104 | 18.6 | 0.81 | 0.24 |

Less than one half of patients (44 %) who were nonpersistent with teriparatide concomitantly used an antiresorptive agent (mean MPR of 0.69 (±0.32) for the antiresorptive agent), and few patients (6 %) who were persistent with teriparatide concomitantly used an antiresorptive agent.

Persistent patients had lower risk of new fractures than nonpersistent patients from 181 to 365 days post-index (2.0 versus 3.4 %, p < 0.001) and after 365 days post-index (3.8 versus 5.5 %, p < 0.001) (data not shown). Patients with a post-index fragility fracture were less likely to be persistent with teriparatide (40.8 %) than patients without a post-index fragility fracture (48.9 %) (p < 0.001) (Table 3). Patients persistent with teriparatide treatment had a significantly lower rate of new or recurrent fragility-related fractures during the 24-month follow-up period than patients nonpersistent with teriparatide (11.4 versus 15.2 % p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Multivariate analysis

As shown in Table 4, a logistic regression model indicated that the following characteristics were statistically significant predictors of having a new or recurrent fracture following teriparatide initiation: teriparatide nonpersistence, increasing age, the number of distinct baseline diagnoses, and a baseline diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. The odds of having a new or recurrent fracture were 1.31 times higher (95 % confidence interval (1.17, 1.47)) for patients nonpersistence with teriparatide than for persistent patients after controlling for baseline demographic and clinical characteristics.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis predicting new or recurrent fracture

| Independent variable | Odds ratio | p value | 95 % CI lower bound | 95 % CI upper bound |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teriparatide nonpersistence | 1.313 | <0.001 | 1.174 | 1.469 |

| Age | 1.027 | <0.001 | 1.022 | 1.033 |

| Baseline antiresorptive use | 1.066 | 0.314 | 0.941 | 1.208 |

| Gender: female | 1.136 | 0.237 | 0.920 | 1.404 |

| Deyo-Charlson comorbidity index score | 1.046 | 0.226 | 0.973 | 1.124 |

| Unique 3-digit ICD-9 codes | 1.043 | <0.001 | 1.035 | 1.052 |

| Abnormalities of the esophagus | 0.614 | 0.002 | 0.453 | 0.832 |

| Active UGI ulcer | 1.007 | 0.976 | 0.647 | 1.568 |

| Alcoholism | 1.199 | 0.692 | 0.488 | 2.944 |

| Diabetes | 1.178 | 0.106 | 0.966 | 1.436 |

| Endocrine disease (excluding diabetes) | 1.157 | 0.304 | 0.876 | 1.527 |

| GERD | 0.896 | 0.224 | 0.750 | 1.070 |

| Renal insufficiency | 1.060 | 0.74 | 0.752 | 1.494 |

| Liver disease | 0.759 | 0.208 | 0.494 | 1.166 |

| Malabsorption syndrome | 0.644 | 0.32 | 0.270 | 1.534 |

| Metabolic bone disease | 0.683 | 0.055 | 0.462 | 1.009 |

| Nephritis | 0.981 | 0.954 | 0.508 | 1.894 |

| Osteopenia | 0.985 | 0.883 | 0.811 | 1.197 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1.489 | <0.001 | 1.234 | 1.796 |

| Thyroid disease | 1.004 | 0.961 | 0.856 | 1.178 |

Discussion

Based on over 5 years of administrative claims data, our study found that patients with fragility-fractures in the year prior to initiating teriparatide are at greater risk for fragility fracture than patients with no baseline fragility-fracture history regardless of treatment persistence status. Overall, nearly one in eight patients had a new or recurrent fragility fracture in the 2-year post-index period following teriparatide initiation and the majority (63.7 %) occurred in the first year post-index period following teriparatide initiation, suggesting that teriparatide does not fully protect against imminent fracture risk. Teriparatide persistence was lower than expected and nonpersistence was more highly associated with post-index fracture incidence (24 months) than in persistent patients (15.2 versus 11.4 % p < 0.001). Cumulative fracture incidence appears to be primarily influenced by the occurrence of a fracture in the pre-index period (Figs. 2 and 3). This risk of fragility fractures appears to be only partially mitigated by persistent use of teriparatide and is consistent with results previously reported [15].

Baseline fragility fracture was comparable between patients persistent and nonpersistent with teriparatide (25 versus 26 %). These rates were lower than the 38 % reported in the Foster et al. [21] study using 2003–2004 MarketScan data, which may be due to differences in fracture definitions or evolving treatment patterns of teriparatide. This current study required a non-diagnostic claim to establish the presence of a fracture while Foster et al. did not discuss their fracture definitions and may have classified patients as having a fracture based only on the presence of a radiological or other diagnostic claim. Further, this current analysis only evaluated new or recurrent fractures during the post-index period using an algorithm that differentiated new or recurrent fractures from fracture claims suggestive of a continuation of a previous fracture episode [17, 22]; it is unclear if Foster et al. used a similar approach.

The demographic and baseline clinical characteristics among patients who were persistent and nonpersistent with teriparatide (data not shown) showed some statistically significant differences between persistent and nonpersistent patients, which may be due to the large sample size (e.g., age, geographic region). The mean DCI score, mean number of unique diagnoses, presence of gastric ulcer, GERD, renal insufficiency, and osteopenia at baseline were statistically significantly different but the magnitude of differences was small.

This current analysis followed 11,407 teriparatide patients for 2 years after initiation. The overall MPR for teriparatide during the 24-month (730 days) post-index period was 0.62, which is similar to that reported by Foster et al. [14] (MPR = 0.58, n = 298 patients) using 2002–2005 MarketScan Commercial database. The current study also showed more than half (52 %) of the study patients experienced a gap in teriparatide treatment, suggesting that forced breaks are implemented in therapy or that consistent use of teriparatide may be a challenge. The persistence rate is much higher than reported by Yu et al. [15], which may be due to the different allowable gap used in the definition of treatment discontinuation (45 days in Yu et al. and 90 days in the current study). Previous research has shown that teriparatide adherence decreases after 6 months of use [14, 15], and the decrease use of teriparatide over longer time periods may be due to medication tolerability [23] including injection discomfort associated with daily subcutaneous injections [24], adverse events [25, 26], cost [27], or other reasons. Once discontinued, patients were less likely to resume treatment as less than one in five nonpersistent patients restarted teriparatide after a gap of 90 days and less than half of all patients transitioned to an antiresorptive; those who did transition did so on average approximately 1 year later.

Concomitant use of antiresorptives during teriparatide treatment was rare among both persistent and nonpersistent patients, which could reflect the lack of adequate clinical data to recommend combination therapy with teriparatide and antiresorptive agents [28, 29]. Of those who discontinued teriparatide, less than 40 % of nonpersistent patients transitioned to an antiresorptive therapy on average, 98 days after the discontinuation of teriparatide. The average antiresorptive treatment duration was 10 months for those who switched.

Findings from this study are subject to several limitations. A main study limitation inherent to administrative databases is that the analysis of teriparatide and antiresorptive osteoporosis medication use was based on outpatient pharmacy prescriptions and/or medical claims rendered during the study period. Errors of omission and commission are also potential limitations in claims database analyses. Perhaps most importantly, claims data have limited clinical information which would include diagnostic evidence (BMD values, laboratory data, etc.), clinical assessment and health status measures, and disease severity, which may be an important factor in teriparatide persistence, adherence, and fracture rates. Formulary status for teriparatide and other antiresorptive agents may have an impact on treatment patterns. While this analysis utilized data from over 100 self-insured employers and health plans, formulary structure for the prescription benefits of those plans was not available for this analysis. This analysis could only evaluate fractures that were diagnosed and generated an insurance claim, which may underestimate the true fracture risk. Finally, the study population was limited to only those individuals continuously enrolled with commercial insurance and Medicare supplemental coverage in the USA. Consequently, results of this analysis should be generalized with care to outcomes in patient populations with other government-sponsored health insurance such as Medicaid and Veterans Health Administration coverage, Medicare enrollees without employer-sponsored supplemental coverage, or populations without health insurance coverage.

Conclusion

New or recurrent fragility fractures were not uncommon following the initiation of teriparatide. Persistence with teriparatide was associated with lower prevalence of fractures over the 24-month (730 days) follow-up period compared to nonpersistent patients. Pre-index fracture was associated with a higher likelihood of post-index fracture independent of teriparatide persistence status. Adherence with teriparatide was high leading up to the point of discontinuation, suggesting an abrupt intentional or non-intentional stop to teriparatide therapy as opposed to more intermittent therapy. The fracture rates post-treatment suggest that a number of patients remain at a high imminent risk for fracture despite initiating and receiving teriparatide, especially if they already have suffered a previous fracture. Future analysis should explore the identification and assessment of risk factors for differential treatment patterns and their association with fracture events and outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Shawn Li for his contributions to the data interpretation and discussion sections. This study was funded by Amgen Inc.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Footnotes

Tony G. Bower was an Amgen employee at the time of the study but currently is not.

References

- 1.Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy (2001) JAMA 285(6):785–795 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Bliuc D, Nguyen ND, Milch VE, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA, Center JR. Mortality risk associated with low-trauma osteoporotic fracture and subsequent fracture in men and women. JAMA. 2009;301(5):513–521. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanis JA, Johnell O. Requirements for DXA for the management of osteoporosis in Europe. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(3):229–238. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1811-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black DM, Thompson DE, Bauer DC, et al. Fracture risk reduction with alendronate in women with osteoporosis: the Fracture Intervention Trial. FIT Research Group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(11):4118–4124. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.11.6953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, et al. Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. Hip Intervention Program Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(5):333–340. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102013440503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meijer WM, Penning-van Beest FJ, Olson M, Herings RM. Relationship between duration of compliant bisphosphonate use and the risk of osteoporotic fractures. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(11):3217–3222. doi: 10.1185/03007990802470241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cramer JA, Gold DT, Silverman SL, Lewiecki EM. A systematic review of persistence and compliance with bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(8):1023–1031. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cramer JA, Amonkar MM, Hebborn A, Altman R. Compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate dosing regimens among women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(9):1453–1460. doi: 10.1185/030079905X61875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallagher JC, Genant HK, Crans GG, Vargas SJ, Krege JH. Teriparatide reduces the fracture risk associated with increasing number and severity of osteoporotic fractures. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(3):1583–1587. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forteo (teriparatide injection) (2002). Product labeling. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company

- 11.Grossman JM, Gordon R, Ranganath VK, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2010 recommendations for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62(11):1515–1526. doi: 10.1002/acr.20295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR, et al. Effect of parathyroid hormone (1–34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(19):1434–1441. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105103441904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saag KG, Shane E, Boonen S, et al. Teriparatide or alendronate in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(20):2028–2039. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster SA, Foley KA, Meadows ES, et al. Adherence and persistence with teriparatide among patients with commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid insurance. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(2):551–557. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1297-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu S, Burge RT, Foster SA, Gelwicks S, Meadows ES. The impact of teriparatide adherence and persistence on fracture outcomes. Osteoporos Int: J Established Result Cooperation Between Eur Found Osteoporos Nat Osteoporos Found USA. 2012;23(3):1103–1113. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1843-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.http://www.forteo.com/Pages/index.aspx. Accessed 30 Nov 2012

- 17.Song X, Shi N, Badamgarav E, et al. Cost burden of second fracture in the US health system. Bone. 2011;48(4):828–836. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gold DT, Martin BC, Frytak JR, Amonkar MM, Cosman F. A claims database analysis of persistence with alendronate therapy and fracture risk in post-menopausal women with osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(3):585–594. doi: 10.1185/030079906X167615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sunyecz JA, Mucha L, Baser O, Barr CE, Amonkar MM. Impact of compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate therapy on health care costs and utilization. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(10):1421–1429. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0586-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adachi J, Lynch N, Middelhoven H, Hunjan M, Cowell W. The association between compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate therapy and fracture risk: a review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:97. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foster SA, Foley KA, Meadows ES, et al. Characteristics of patients initiating raloxifene compared to those initiating bisphosphonates. BMC Womens Health. 2008;8:24. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi N, Foley K, Lenhart G, Badamgarav E. Direct healthcare costs of hip, vertebral, and non-hip, non-vertebral fractures. Bone. 2009;45(6):1084–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.07.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ziller V, Zimmermann SP, Kalder M, et al. Adherence and persistence in patients with severe osteoporosis treated with teriparatide. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(3):675–681. doi: 10.1185/03007990903538409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adachi JD, Hanley DA, Lorraine JK, Yu M. Assessing compliance, acceptance, and tolerability of teriparatide in patients with osteoporosis who fractured while on antiresorptive treatment or were intolerant to previous antiresorptive treatment: an 18-month, multicenter, open-label, prospective study. Clin Ther. 2007;29(9):2055–2067. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mulgund M, Beattie KA, Wong AK, Papaioannou A, Adachi JD. Assessing adherence to teriparatide therapy, causes of nonadherence and effect of adherence on bone mineral density measurements in osteoporotic patients at high risk for fracture. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2009;1(1):5–11. doi: 10.1177/1759720X09339551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gold DT, Weinstein DL, Pohl G, Krohn KD, Chen Y, Meadows ES. Factors associated with persistence with teriparatide therapy: results from the DANCE observational study. J Osteoporos. 2011;2011:314970. doi: 10.4061/2011/314970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamariz L, Uribe CL, Luo J, et al. Persistence with biologic therapies in the Medicare coverage gap. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(11):753–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stroup J, Kane MP, Abu-Baker AM. Teriparatide in the treatment of osteoporosis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(6):532–539. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hodsman AB, Bauer DC, Dempster DW, et al. Parathyroid hormone and teriparatide for the treatment of osteoporosis: a review of the evidence and suggested guidelines for its use. Endocr Rev. 2005;26(5):688–703. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]