Abstract

Clinical diagnostic criteria for memory loss in adults typically assume that subjective memory ratings accurately reflect compromised memory functioning. Research has documented small positive between-person associations between subjective memory and memory performance in older adults. Less is known, however, about whether within-person fluctuations in subjective memory covary with within-person variance in memory performance and depressive symptoms. The present study applied multilevel models of change to nine waves of data from 27,395 participants of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS; mean age at baseline = 63.78; SD = 10.30; 58% women) to examine whether subjective memory is associated with both between-person differences and within-person variability in memory performance and depressive symptoms and explored the moderating role of known correlates (age, gender, education, and functional limitations). Results revealed that across persons, level of subjective memory indeed covaried with level of memory performance and depressive symptoms, with small-to-moderate between-person standardized effect sizes (0.19 for memory performance and 0.21 for depressive symptoms). Within individuals, occasions when participants scored higher than usual on a test of episodic memory or reported fewer-than-average depressive symptoms generated above-average subjective memory. At the within-person level, subjective memory ratings became more sensitive to within-person alterations in memory performance over time and those suffering from functional limitations were more sensitive to within-person alterations in memory performance and depressive symptoms. We take our results to suggest that within-person changes in subjective memory in part reflect monitoring flux in one’s own memory functioning, but are also influenced by flux in depressive symptoms.

Keywords: longitudinal, cognitive aging, subjective memory, memory performance, depressive symptoms

Aging researchers have long been interested in understanding people’s perception of their own memory (e.g., Dixon & Hultsch, 1983; Kahn, Zarit, Hilbert, & Niederehe, 1975). The increased concerns about memory impairment in old age make it important to understand how subjective perceptions of memory functioning develop and whether they derive from actual memory performance or other sources, such as depressive symptoms. Our goal in the present study was to move from the usual between-person differences perspective towards approaching this question from a within-person perspective. At the between person level, we examined whether a participant who shows higher memory performance and reports fewer depressive symptoms as compared to peers also reports higher subjective memory. At the within-person level, we focused on fluctuations in these constructs. Long-term intraindividual change is typically defined as more or less enduring within-person trends that take place over many years. Intraindividual fluctuations refer to occasion-specific deviations of a person’s scores from his or her long-term trajectory (see Nesselroade, 1991; Sliwinski, 2011). We examined whether a participant’s fluctuating perceptions of his or her own memory functioning are coupled with fluctuations in his or her memory test performance or depressive symptoms. In doing so, we made use of 9-wave longitudinal data from 27,395 participants of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) to examine between-person and within-person associations between subjective memory, memory performance, and depressive symptoms and to explore the moderating role of known correlates.

Between-Person Associations between Subjective Memory, Memory Performance, and Depressive Symptoms

Cross-sectional studies have typically shown that better memory performance is associated with more favorable subjective reports of memory functioning, but the association is usually small (e.g. Gilewski, Zelinski, & Schaie, 1990; Hertzog, Dixon, & Hultsch, 1990; Pearman & Storandt, 2004). In a recent meta-analysis of 107 studies, Beaudoin and Desrichard (2011) found a small weighted mean correlation between subjective and objective memory (r = .15) that was reliably different from zero.

Longitudinal studies, where subjective memory and memory performance are assessed repeatedly over time, can be used to examine correlations between rates of long-term change in subjective memory and rates of long-term change in memory performance in bivariate latent growth curve models (McArdle, 1988). A positive correlation of the two slopes would indicate that individuals who exhibit steeper declines in subjective memory also show steeper declines in memory performance, relative to their peers. Some studies have found small correlations between rates of long-term change in the two variables (e.g., Lane & Zelinski, 2003; McDonald-Miszczak, Hertzog, & Hultsch, 1995). Two recent longitudinal studies using growth curve models reported more robust correlations between long-term changes in subjective memory and long-term changes in memory performance (Mascherek & Zimprich, 2011; Parisi et al., 2011). However, another recent longitudinal study using growth curve analysis in persons over the age of 70 reported no significant correlation between changes in memory complaints (which did not vary reliably across individuals) and changes in memory performance (Pearman et al., in press).

Multiple cross-sectional studies have shown that individuals with more depressive symptoms tend to report more subjective memory complaints. Kahn et al. (1975) initially reported that subjective memory complaints were in fact more closely related to depressive symptoms than to memory performance. Since then, many studies have replicated the link between subjective memory and depressive symptoms (e.g., Crane, Bogner, Brown, & Gallo, 2007; Zelinski & Gilewski, 2004; Pearman et al., in press) or with the personality trait of neuroticism (e.g., Pearman & Storandt, 2005; Pearman et al., in press).

A Within-Person Coupling Approach

Previous evidence about correlated changes in subjective memory and memory performance has been derived from analysis and interpretation of between-person associations, even when longitudinal data have been analyzed. For example, growth curve models of longitudinal data can examine whether individuals who show steeper declines of memory performance also report steeper declines of subjective memory as compared to their peers. However, these findings do not necessarily imply that the variables are coupled within an individual, such that within-person fluctuations in one variable covary with analogous fluctuations in the other variable. Prioritizing a within-person perspective, we examine whether an individual’s subjective memory reports are coupled over time with his or her actual performances on memory tests or with his or her depressive symptoms. That is, on occasions when the typical person performs worse than usual, does he or she also report lower than usual subjective memory? Asking the question from this within-person perspective provides additional information about the factors that potentially influence subjective memory.

Long-term intraindividual change is typically defined as more or less enduring (developmental) linear and quadratic trends that manifest over many years. Intraindividual fluctuations refer to occasion-specific deviations from an individual’s enduring trajectory (see Nesselroade, 1991; Sliwinski, 2011). Repeated measures data can be used to examine within-person covariances directly, provided that sufficient occasions of measurement are available to discriminate long-term intraindividual change from intraindividual fluctuations. With an appropriate study design and analysis, the coupling of variables within individuals can be statistically identified independent of long-term change (see Molloy, Ram & Gest, 2011; Ram et al., 2014; Schoellgen, Morack, Infurna, Ram, & Gerstorf, under review; Thorvaldsson et al., 2012).

Although much can be learned from between-person correlations of within-person slopes from latent growth curve models (e.g.., Parisi et al., 2011), this approach can be challenged on the basis of the implicit assumption of ergodicity (homogeneity in the nature of within-person change and variability; e.g., Brose, Schmiedek, Lövdén, Molenaar, & Lindenberger, 2010; Molenaar, 2013). Inferring intraindividual coupling from between-person slope correlations risks ecological fallacy (Robinson, 1950), because correlations of between-person differences in aggregate amounts of change do not necessarily imply that variables are coupled within-person as they fluctuate across time. For instance, Stawski, Sliwinski, and Hofer (2013) found that processing speed was related to working memory at the between-person level, but not at the within-person level (see also Schmiedek, Lövdén, & Lindenberger, 2013). They argued that between-person differences in processing speed may provide a general index of brain integrity, while the lack of significant associations between processing speed and working memory at the within-person level suggests that processing speed is not a central mechanism involved in working memory. If subjective memory ratings are indeed derived by monitoring one’s memory functioning, associations between these constructs should emerge at the within-person level. That is, on occasions when an individual performs higher than usual on tests of memory, he or she should also report higher levels of perceived memory functioning.

Intraindividual Change and Variability in Memory Performance

Cognitive function in old age shows considerable stability of individual differences (e.g., Hertzog & Schaie, 1986). However, cognitive function – including episodic memory – also shows reliable intraindividual (within-person) variability in younger and older adults over time (e.g., Hertzog, Dixon, & Hultsch, 1992; Ram, Rabbitt, Stollery, & Nesselroade, 2005; Schmiedek et al., 2013; Sliwinski, Smyth, Hofer, & Stawski, 2006;), also over similar time scales as examined in the present study (Bielak, Hultsch, Strauss, MacDonald, & Hunter, 2010; Sliwinski & Buschke, 1999, 2004). The research to date has only examined short-term variability and coupling, but not longer term covarying change. Previous research has shown that day-to-day fluctuations in environmental demands and stressors may increase the likelihood that intrusive thoughts interfere with ongoing cognitive activity and lower one’s sense of control in cognitively demanding situations (Lachman & Agrigoroaie, 2012; Sliwinski & Scott, 2014). If memory successes and failures fluctuate over time and individuals are able to monitor these outcomes, then their subjective memory would covary accordingly. That is, on occasions when an individual experiences better memory outcomes than usual, accurate memory monitoring should also lead him or her to report higher subjective memory, independent of long-term change.

Intraindividual Change and Variability in Depressive Symptoms

Previous research has shown that depressive symptoms fluctuate within a person over time. For instance, Spielberger (1995) differentiated between trait and state depressive symptoms. Hence the link between depressive symptoms and subjective memory that has been established in the literature (using between-person associations) could reflect flux in depressive symptoms that generates intraindividual variability in subjective memory as well. Furthermore, depressive symptoms in old age typically include somatic complaints (Müller-Spahn & Hock, 1994; Sutin et al., 2013), cognitive slowing (Broomfield et al., 2007), and apathy (Lampe & Heeren, 2004; Mehta et al., 2008). These symptoms may cause everyday memory problems independent of the influence created by long-term age-related memory decline. These fluctuating influences will produce less favorable self-ratings of memory functioning on occasions when depressive symptoms are elevated, but self-rated memory can also increase when depressive symptoms are damped by more favorable circumstances or the waxing of cyclic endogenous influences.

The Present Study

In the present study, we examined between-person and within-person associations among subjective memory, memory performance and depressive symptoms using multilevel models of change that were applied to nine waves of data from the HRS (N = 27,395). Following the usual between-person perspective, we expected to corroborate earlier findings indicating between-person correlations of depressive symptoms, memory performance and subjective memory. Based on previous research, we expected those with more education and fewer functional limitations to report higher levels of subjective memory (e.g., Zelinski, Burnight, & Lane, 2001). Furthermore, we expected stronger between-person associations of subjective memory and memory performance for those with more education (see Zelinski et al., 2001). As previous research on age and gender differences in subjective memory was inconclusive (see Hertzog & Pearman, 2014), we did not have specific hypotheses about these correlates. Extending into the within-person perspective, we also evaluated the extent of within-person coupling of memory performance and depressive symptoms with subjective memory and whether individual differences existed in the strength of these couplings. We expected memory performance and depressive symptoms to relate to subjective memory at the within-person level as well. We explored age, gender, education, and functional limitations as potential moderators of these within-person associations.

Method

Longitudinal data for our study of between-person and within-person associations among subjective memory, memory performance, and depressive symptoms were drawn from the HRS. Detailed descriptions of participants, variables, and procedures can be found in McArdle, Fisher, and Kadlec (2007) and Soldo, Hurd, Rodgers, and Wallace (1997) for the core HRS, and in Gerstorf, Hoppmann, Kadlec, and McArdle (2009) and Hülür, Infurna, Ram, & Gerstorf (2013) for the Asset and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old (AHEAD) component of the HRS that involved older subsamples. Specific details relevant to the present study (HRS + AHEAD) are presented below.

Participants and Procedure

The HRS started in 1992 with a nationally representative probability sample of households in the United States that included a non-institutionalized individual of age 50 years or more. If a study participant was married or living with a partner, the spouse or partner was also asked to participate, regardless of her or his age. Thus, the individuals in the sample also included participants who were younger than 50 years old. Data collection took place every second year since 1992, with new ‘refresher’ cohorts added every six years (with a few exceptions, e.g., the AHEAD cohort that merged into the HRS in 1998 had also been assessed in 1993 and 1995). By 2010, data were available for more than 30,000 participants, with consistent measurement of memory performance across all but two waves (i.e., in 1992 and 1994 memory performance was assessed differently than in other waves).

Our analysis makes use of data from N = 27,395 participants who provided (a) at least one wave of data on subjective memory, memory performance and depressive symptoms when they were 50 years old or older, and (b) information on the correlates (age, gender, years of education, and at least one observation on functional limitations). In total, we analyzed longitudinal data that was obtained on up to nine measurement occasions over 17 years (1993, 1995, 1996, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, and 2010). On average, participants (58% women) were 63.78 years old at their first measurement occasion (SD = 10.30; range = 50 to 104 years) and had obtained 12.03 years of formal education (SD = 3.40).

Measures

Subjective memory

The main outcome variable, subjective memory, was measured at each occasion using the item, “How would you rate your memory at the present time? Would you say it is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?”, with responses provided on a 0 (poor) to 4 (excellent) scale (Herzog & Wallace, 1997). Number of observations and descriptive statistics by age for the subjective memory measure are shown in Table 1. As can be seen, participants rated their memory functioning less favorably at higher ages, and fewer observations were available at higher ages.

Table 1.

Total Observations of Subjective Memory Provided by Age

| Age | n | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50–59 | 31,846 | 50.11 | 9.64 |

| 60–69 | 44,770 | 48.46 | 9.31 |

| 70–79 | 38,921 | 48.30 | 9.44 |

| 80–89 | 18,139 | 47.38 | 9.91 |

| 90–99 | 2,604 | 47.24 | 10.74 |

| 100–109 | 43 | 45.70 | 12.50 |

Note. Total number of observations provided across all utilized waves of the HRS. N = 27,395.

Memory performance

Episodic memory performance was measured at each occasion using tests of immediate and delayed free recall (see Ofstedal, Fischer, and Herzog, 2005). In brief, a list of 10 nouns was presented to the participants, and they were asked to recall as many words as possible (a) immediately after presentation and (b) after a delay of approximately five minutes. Immediate and delayed recall conditions were scored as the proportion of words correctly remembered (ranging from 0 to 1), and summed to create a single index where higher scores indicated better memory performance. This memory performance score had a reliability of Cronbach’s α = 0.85 to 0.87 for various subsamples (Ofstedal et al., 2005).

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms (DS) were measured at all occasions as the sum of responses to eight items from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Specifically, participants indicated whether they had experienced (0 = no, 1 = yes) a variety of depressive symptoms (e.g., felt depressed, everything was an effort) during the past week (Wallace et al., 2000). The CES-D cannot be used on its own to diagnose clinical depression but is generally considered a good measure of depressive symptomatology. This eight-item measure had a reliability of Cronbach’s alpha = 0.77 to 0.83 for various subsamples of the HRS (Wallace et al., 2000).

Correlates

Time in study, gender, education, functional limitations, and average age were included as correlates in our models. Gender was a time-invariant dichotomous variable obtained as part of the initial demographics questionnaire. Education was a time-invariant variable indexed as the number of years an individual had spent in formal schooling. Extent of functional limitations was assessed at each wave as the sum of responses to items asking individuals to indicate whether they had difficulty performing 10 everyday activities (0 = no; 1 = yes): using the phone, managing money, shopping for groceries, preparing hot meals, walking several blocks, climbing one flight of stairs, lifting or carrying over 10 lbs, picking a dime up, and pulling or pushing large objects (adapted from Lawton & Brody, 1969; Nagi, 1969, 1976). Scores ranged from 0 to 10 with higher scores indicating more difficulties (Rodgers & Miller, 1997). Age was calculated at each wave as the difference between an individual’s birth year and the year of the assessment. Individual’s average age was calculated as the arithmetic mean of all available ages, separately for each participant.

To facilitate the interpretation of model parameters, subjective memory, memory performance, depressive symptoms, and functional limitation scores were converted into a T-score metric (M = 50; SD = 10) using baseline sample statistics. Descriptive statistics for and correlations among measures at baseline assessment are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations of Subjective Memory, Memory Performance, Depressive Symptoms, and Correlates at Baseline.

| M | SD | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Subjective memory (0 – 4) | 2.17 | 0.99 | 1 | ||||||

| (2) Memory performance (0 – 1) | 0.50 | 0.19 | 0.18* | 1 | |||||

| (3) Depressive symptoms (0 – 8) | 1.43 | 1.92 | −0.23* | −0.18* | 1 | ||||

| (4) Age at baseline (50 – 104) | 63.78 | 10.30 | −0.06* | −0.43* | 0.01 | 1 | |||

| (5) Gender (0 = men; 1 = women) | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 0.12* | 0.08* | −0.02 | 1 | ||

| (6) Years of education (8 – 17) | 12.03 | 3.40 | 0.24* | 0.40* | −0.24* | −0.23* | −.04* | ||

| (7) Functional limitations (0 – 10) | 1.30 | 1.81 | −0.23* | −0.27* | 0.40* | 0.23* | 0.11* | −0.27* | 1 |

Note. N = 27,395. M = mean. SD = standard deviation.

p < 0.001

Data analysis

Data preparation

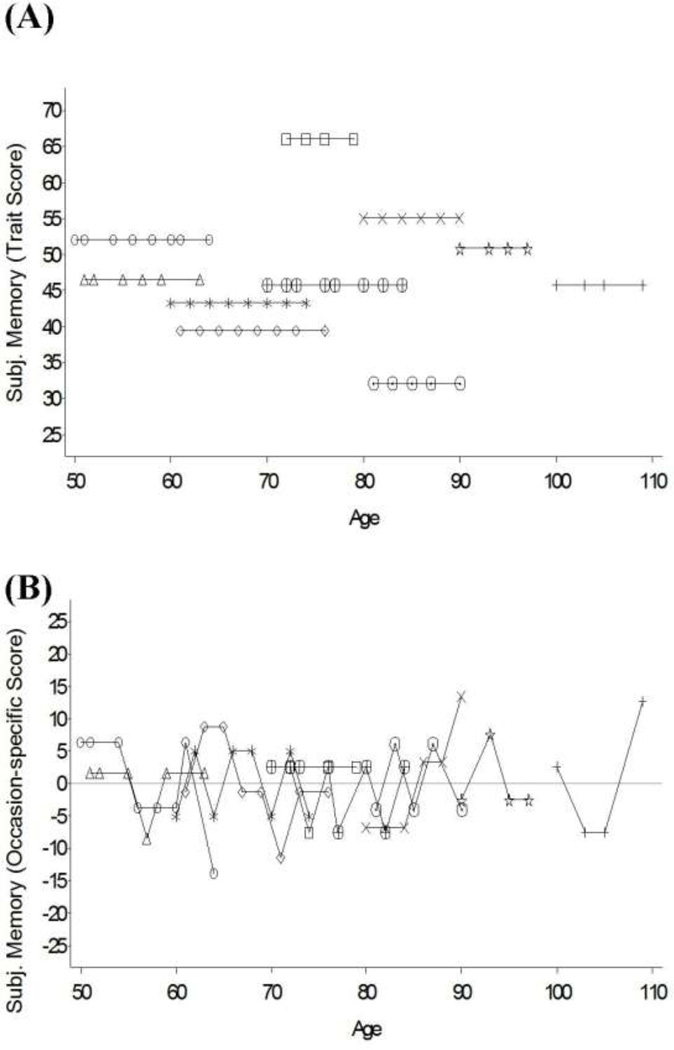

Prioritizing the separation of within-person coupling from between-person associations, we split the time-varying predictors of interest into “state” (within-person changes) and “trait” components (between-person differences) using the procedures typically used in analysis of intensive longitudinal data (see e.g., Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013; Schwartz & Stone, 2007). Specifically, between-person components (average memoryi and chronic DSi) were defined as the average of an individual’s repeated measures of memory and depressive symptoms. The within-person component (occasion–specific memoryti and occasion-specific DSti), then, was defined as the occasion-to-occasion deviation from this average. For example, Figure 1 illustrates how the repeated measures of subjective memory obtained from a random set of 10 individuals were split into a trait (time-invariant) component (Panel A) and a state (time-varying) component. To reduce complexity of our models, the number of functional limitations was only examined as a between-person, trait variable. All person-level predictors were centered at sample means so that the intercepts and coefficients can be interpreted as representing the typical or average person in the sample.

Figure 1.

Subjective memory scores from 10 participants used to illustrate how this variable can be separated into between-person components (trait score) and within-person components (occasion-specific score). Panel A shows the individual averages obtained by taking the mean across an individual’s time series and are time-invariant. Panel B shows the individual deviations obtained by subtracting the mean from each score across the time-series. The individual residuals represent time-varying deviations from the individual average and are centered at zero. Negative residuals indicate that at a given occasion an individual reported lower subjective memory than his or her own average. Data presented in T scores (M= 50 and SD= 10).

Multilevel model of change

To separate and simultaneously examine how the larger set (predictors and correlates) of between-person and within-person variables were associated with subjective memory, we applied a multilevel model of change (occasions nested within persons) to the nine-occasion data from the HRS. The model was specified as

| (1) |

where Subjective_Memoryti, personi’s subjective memory score at occasion t, is a function of an individual specific intercept parameter, β0i; individual-specific slope parameters, β1i, capturing linear change per year, β2i capturing the acceleration of change per year; an individual-specific coupling between subjective memory and state component of memory performance (that is independent of linear and quadratic changes across time), β3i; an individual-specific coupling between subjective memory and state component of depressive symptoms (independent of linear and quadratic changes across time), β4i; coefficients indicating the extent to which time moderates the within-person couplings of subjective memory and memory performance, β5i, and the within-person couplings of subjective memory and depressive symptoms, β6i; and residual error, eti. Of note long-terms individual-level trends are modeled with respect to time in study, timeit, which was centered at the middle of an individual’s time series. This choice implements a statistical model that is conceptually equivalent with time-series modeling wherein the data are “detrended” separately for each individual. In principle the within-person centering provides a relatively conservative approach wherein as much variance as possible is attributed to long-term trends and not available for within-person coupling. A variety of follow-up analyses were used to check the impact of the centering choice.

Following standard multilevel modeling procedures, individual-specific intercept, β0i, linear slope, β1i, quadratic slope, β2i, couplings β3i and β4i, moderations of the occasion-specific associations by time, β5i and β6i, were modeled as

| (2) |

where the γs are the sample-level intercepts and associations and the us are individual-specific deviations from these sample-level intercepts and associations. The sample-level (between-person) association between subjective memory and memory performance (independent of all other variables) is denoted by γ04, and the typical within-person association by γ30. Likewise, the sample-level (between-person) association between subjective memory and depressive symptoms is denoted by γ05, and the typical within-person association by γ40. We note that individual deviations in the moderation of within-person couplings by time, β5i and β6i could not be estimated due to convergence issues (i.e., pushed beyond the viable number of random effects), and thus assumed invariant across persons. Between-person differences in the quadratic slope, β2i, were left un-modeled to provide for a more parsimonious model. In order to examine whether memory performance or depressive symptoms was a better predictor of subjective memory, we compared proportional reductions in prediction error (i.e., a pseudo-R2 measure; Snijders & Bosker, 1999) of two models that only included either memory performance or depressive symptoms as predictors at the between-person and within-person levels. Models were estimated in SAS 9.4 using PROC MIXED (Littell, Milliken, Stroup, Wolfinger, & Schabenberger, 2006) with incomplete data treated as missing at random (Little & Rubin, 1987).

Due to the large sample size, very small effects could reach conventional levels of significance (even at p < .001). Hence, we do not emphasize significance tests here, but instead focus more on reporting and evaluating effect sizes (Harlow, Mulaik, & Steiger, 1997). However, this is not entirely straightforward when using multi-level regression models, where issues of how to calculate and how to interpret effect size statistics at the within-person level of analysis are still not established. In this study, we used the Mplus 7.0 program (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012) to obtain estimates of the within-person and between-person variances, and then used these estimates to calculate standardized regression estimates (STEs) at both the between-person and within-person levels. That is, the unstandardized regression estimates were rescaled using the between-person and within-person SDs of the relevant variables, thus representing size of effects in between-person or within-person SD units. We forthrightly acknowledge that this approach for obtaining effect sizes includes some generally unresolved issues. For example, Level 1 (within-person) and Level 2 (between-person) standardized effects cannot be directly compared because effects scaled in between-person SDs may have different implications for outcomes than effects scaled in within-person SDs. In particular, the within-between decomposition implicitly assigns all random measurement error variance to the lowest level of analysis (in our case, to within-person variance). Furthermore, all widely accepted benchmarks for effect sizes are scaled in between-person SDs (e.g., Cohen, 1988) and were derived from research where stable individual differences are a major component of the between-person SD. However, their utility for assessing practical significance at the within-person level is questionable. Still, while the benchmarks based on between-person SDs form a basis for conceptualizing replicability of results (e.g., Killeen, 2005), the ‘normative’ reproducibility of within-person effects scaled against within-person SDs is a largely unexplored issue at present. Our interest in considering STEs at each level is a practical one – to avoid interpretation of exceptionally small effects. Thus, keeping in mind issues surrounding both practical and statistical meaningfulness, we set the Type I criterion to .001 and set benchmarks of between-person STE = .050 and within-person STE = .010 as values to be equaled or exceeded in absolute magnitude for a regression effect to be considered practically meaningful.

Results

Parameter estimates and model fits are shown in Table 3, with the variance-covariance matrix for the random effects shown in Table 4. Results from each portion of the model are presented below.

Table 3.

Multilevel Model examining the Coupling of Memory Performance and Depressive Symptoms with Subjective Memory (Fixed Effects)

| Parameter | Estimate (SE) | Standardized regression estimate (STE) |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | ||

| Intercept, γ 00 | 47.771* (0.068) | 6.773* |

| Changes across time in study and correlates | ||

| Time, γ10 | −0.227* (0.008) | −0.135* |

| Time × time, γ20 | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.002 |

| Gender, γ01 | 0.475* (0.091) | 0.033 |

| Education, γ02 | 0.391* (0.016) | 0.188* |

| Functional limitations, γ03 | −0.094* (0.008) | −0.133* |

| Average age, γ013 | 0.038* (0.005) | 0.055* |

| Average age × average age, γ014 | 0.006* (<0.001) | 0.088* |

| Gender × time, γ11 | 0.044* (0.012) | 0.012 |

| Education × time, γ12 | −0.009* (0.002) | −0.017 |

| Functional limitations × time, γ13 | 0.002 (0.001) | 0.011 |

| Time × average age, γ16 | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.006 |

| Time × average age × average age, γ17 | −0.0004* (0.0001) | −0.023 |

| Between-person associations | ||

| Average memory, γ04 | 0.158* (0.007) | 0.192* |

| Average memory × time, γ14 | 0.008* (0.001) | 0.038 |

| Average memory × gender, γ06 | −0.084* (0.011) | −0.050* |

| Average memory × education, γ07 | 0.023* (0.002) | 0.095* |

| Average memory × functional limitations, γ08 | 0.002* (0.001) | 0.024 |

| Chronic DS, γ05 | −0.171* (0.007) | −0.207* |

| Chronic DS × time, γ15 | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.005 |

| Chronic DS × gender, γ09 | −0.005 (0.012) | −0.003 |

| Chronic DS × education, γ010 | 0.000 (0.002) | 0.000 |

| Chronic DS × functional limitations, γ011 | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.012 |

| Chronic DS × average memory, γ012 | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.010 |

| Within-person associations | ||

| Occasion-specific memory, γ30 | 0.030* (0.005) | 0.030* |

| Occasion-specific memory × average memory, γ34 | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.009 |

| Occasion-specific memory × chronic DS, γ35 | 0.000 (0.001) | 0.000 |

| Occasion-specific memory × time, γ50 | 0.003* (0.001) | 0.012* |

| Occasion-specific memory × gender, γ31 | 0.008 (0.007) | 0.004 |

| Occasion-specific memory × education, γ32 | 0.002 (0.001) | 0.007 |

| Occasion-specific memory × functional limitations, γ33 | 0.002* (<0.001) | 0.020* |

| Occasion-specific memory × average age, γ36 | 0.000 (<0.001) | 0.000 |

| Occasion-specific memory × average age × average age, γ37 | 0.000 (<0.001) | 0.000 |

| Occasion-specific DS, γ40 | −0.063* (0.005) | −0.067* |

| Occasion-specific DS × chronic DS, γ44 | 0.000 (<0.001) | 0.000 |

| Occasion-specific DS × average memory, γ45 | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.009 |

| Occasion-specific DS × time, γ60 | −0.001 (0.001) | 0.004 |

| Occasion-specific DS × gender, γ41 | 0.002 (0.007) | 0.001 |

| Occasion-specific DS × education, γ42 | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.004 |

| Occasion-specific DS × functional limitations, γ43 | −0.002* (<0.001) | −0.021* |

| Occasion-specific DS × average age, γ46 | 0.002* (<0.001) | 0.022* |

| Occasion-specific DS × average age × average age, γ47 | 0.000 (<0.001) | 0.000 |

| −2LL | 940,968 | |

| AIC | 941,000 |

Note. N = 27,395 participants. Subjective memory, memory performance and depressive symptoms standardized to a T metric (M = 50, SD = 10) based on cross-sectional data of the present sample at baseline. Unstandardized estimates. Standard errors in parentheses. DS = depressive symptoms.

p < .001, or STE ≥ 0.050 for changes across time in study and between-person associations, and STE ≥ 0.010 for within-person associations.

Table 4.

Multilevel Model examining the coupling of Memory Performance and Depressive Symptoms with Subjective Memory (Random Effects)

| Parameter | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random effects (variance-covariance matrix) | |||||

| Intercept | Time | Time × time | Occasion-sp. memory | Occasion-sp. DS | |

| Intercept | 42.154* (0.501) | ||||

| Time | 0.010 (0.042) | 0.139* (0.006) | |||

| Time × time | −0.102* (0.009) | −0.002 (0.001) | 0.002* (<0.001) | ||

| Occasion-sp. memory | −0.030 (0.025) | −0.006 (0.002) | 0.000 (<0.001) | 0.011* (0.002) | |

| Occasion-sp. DS | 0.052 (0.023) | 0.003 (0.002) | 0.001 (<0.001) | −0.001 (0.001) | 0.019* (0.001) |

| Residual variance | 37.773* (0.208) | ||||

Note. N = 27,395 participants. Subjective memory, memory performance and depressive symptoms standardized to a T metric (M = 50, SD = 10) based on cross-sectional data of the present sample at baseline. Unstandardized estimates. Standard errors in parentheses. DS = depressive symptoms.

p < .001.

Age-Related Long-Term Trends in and Correlates of Subjective Memory

For the typical person at the middle of their time series, subjective memory was γ00 = 47.771 and decreased slightly by γ10 = −0.227 per year (about 2 T-score units per decade). There were individual differences in both levels of subjective memory (σ2u0= 42.154), and in rate of linear change in subjective memory across time (σ2u1= 0.139), even after accounting for the variables in our model. Although there was no reliable quadratic change in subjective memory across time at the sample level (γ20 = 0.001, p = 0.363), there were substantial individual differences in the quadratic component of changes in subjective memory across time (σ2u2= 0.002, p < 0.001). For those with higher levels of subjective memory, accelerated declines in subjective memory were weaker (σu0,u2 = −0.102).

Education (γ02 = 0.391; STE = 0.188) and functional limitations (γ03 = −0.094; STE = −0.133) related to levels of subjective memory: Those with more education and those with fewer functional limitations reported better subjective memory. Gender (γ01 = 0.475) was also related to subjective memory with women reporting higher ratings, but the effect fell below our criterion of 0.050 for practical significance of between-subjects effects (STE = 0.033). Unexpectedly, older participants reported better subjective memory (γ013 = 0.038; STE = 0.055) controlling for all other covariates, and this effect of age on ratings of subjective memory became even stronger at higher ages (γ014 = 0.006; STE = 0.088), suggestive of (as will be discussed below) either age-related expectation biases or age-based selectivity in the sample. Women’s reports of subjective memory declined less steeply, on average, over time than men’s reports, (γ11 = 0.044; STE = 0.012), but the difference was very small. Likewise, individuals with higher levels of education (γ12 = −0.009) showed slightly steeper declines of subjective memory over time, but again the effect fell below our criterion of 0.050 for practical significance of between-subjects effects (STE = −0.017).

Between-Person Associations of Subjective Memory with Memory Performance and Depressive Symptoms

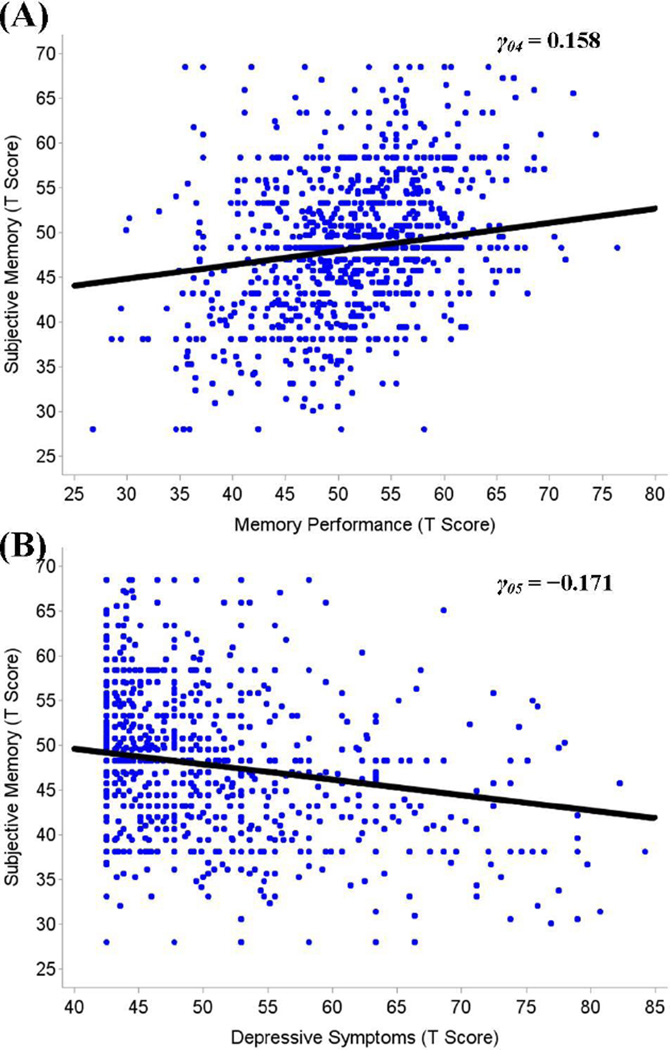

There was a positive between-person association between subjective memory and memory performance, as shown in Panel A of Figure 2. Individuals who performed better on the memory test tended to report better subjective memory (γ04 = 0.158; STE = 0.192): People who were 1 between-person SD above the sample mean in memory were, on average, 0.192 SDs above the sample mean in subjective memory, what would traditionally be seen as a small-to-moderate standardized (in between-person SD units) regression coefficient (Cohen, 1988). Gender (γ06 = −0.084; STE = −0.050) and education (γ07 = 0.023; STE = 0.095) moderated the between-person association of subjective memory and memory performance. That is, among men and better-educated individuals, levels of memory performance were more strongly associated with subjective memory. Functional limitations (γ08 = 0.002; STE = 0.024) also moderated the association between memory performance and subjective memory, but the extent of moderation was of relatively small effect size. Participants with higher average levels of memory performance tended to show less steep declines of subjective memory over time (γ14 = 0.008; STE = 0.038).

Figure 2.

Panel A shows the average between-person association of subjective memory and memory performance. The dots are raw data from 1,000 participants, and the line shows the average between-person association between individual’s average memory performance and subjective memory. Participants with higher average memory performance also reported higher subjective memory. Panel B shows the average between-person association of subjective memory and depressive symptoms. Participants reporting higher average levels of depressive symptoms reported lower subjective memory. The figure also highlights the tremendous amount of between-person differences. Data presented in T scores (M= 50 and SD= 10).

As shown in Panel B of Figure 2, depressive symptoms negatively associated with subjective memory at the between-person level. As expected, individuals who reported more chronic depressive symptoms also reported lower subjective memory (γ05 = −0.171; STE = −0.207): People who were 1 SD above the sample mean in chronic depressive symptoms, were on average about 0.207 SD below the sample mean in subjective memory. The between-person association between subjective memory and depressive symptoms was not moderated by any of the other correlates. Taken together, this portion of the analyses corroborated earlier findings that between-person differences in subjective memory are associated with between-person differences in memory performance and depressive symptoms and that these associations are small in magnitude.

Within-Person Associations of Subjective Memory with Memory Performance and Depressive Symptoms

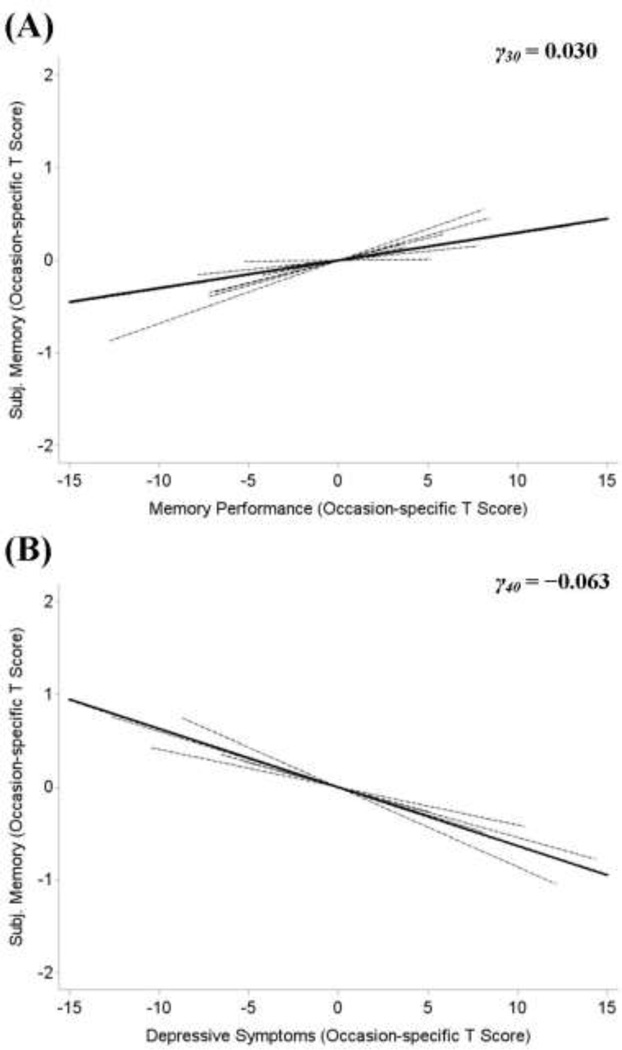

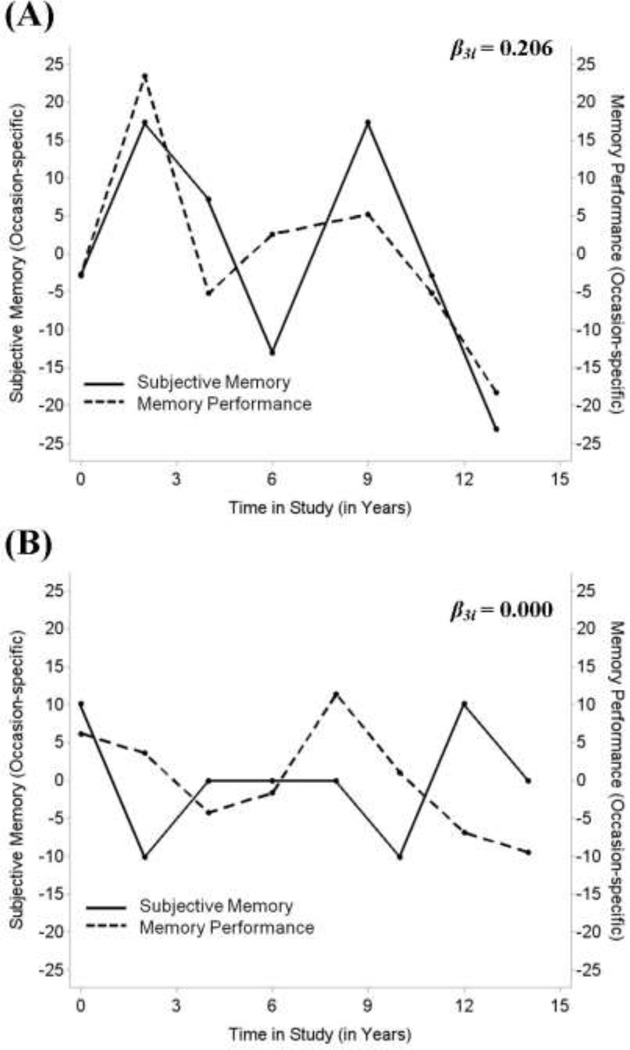

Continuing to the within-person portion of the analyses, we found that, typically, on occasions when an individual showed higher levels of memory performance than usual, he or she also reported higher levels of subjective memory (γ30 = 0.030, STE = 0.030): on occasions when individuals’ memory performance was 1 within-person SD better than usual, they tended to rate their subjective memory about 3.0% of a within-person SD higher than usual. This small positive within-person association is displayed in Panel A of Figure 3. As illustrated by the multitude of lines in the figure, there were individual differences in the strength of this within-person association (σ2u3= 0.011). As well, the within-person association between subjective memory and memory performance was moderated by time in study and functional limitations: The within person-association became stronger over time (γ50 = 0.003; STE = 0.012) and was stronger among participants with more functional limitations (γ33 = 0.002; STE = 0.020). Figure 4 illustrates within-person associations between subjective memory and memory performance for two participants.

Figure 3.

Panel A shows the average within-person association of subjective memory and memory performance (solid line). The within-person relations of 10 participants are also plotted (dashed lines). On occasions when individuals scored higher than usual on a test of episodic memory, they also reported higher subjective memory than usual. Panel B shows the average within-person association of subjective memory and depressive symptoms (solid line) and the within-person relations of 10 participants (dashed lines). On occasions when individuals reported more than usual depressive symptoms, they also reported lower subjective memory than usual. Again, the figure also highlights the tremendous amount of between-person differences. Data presented in T scores (M= 50 and SD= 10).

Figure 4.

Individual plots of within-person association between subjective memory (solid line) and memory performance (dashed line). Each plot represents an individual participant. Panel A illustrates a person with a positive within-person association (β2i = 0.206) that is well above the sample mean of γ20 = 0.030), indicating closely related subjective memory and memory performance. In contrast, Panel B shows a person with no within-person association between subjective memory and memory performance (β2i = 0.000).

At the within-person level, subjective memory was also associated with depressive symptoms (γ40 = −0.063; STE = −0.067): On an occasion when an individual was 1 SD above their usual (average) level of depressive symptoms, they were 6.7% of a SD lower than their average level on subjective memory. This within-person association, along with some of the individual differences (σ2u4= 0.019), is shown in Panel B of Figure 3. Functional limitations and age moderated the within-person association between subjective memory and depressive symptoms: For individuals with more functional limitations, the within-person association between depressive symptoms and subjective memory was more strongly negative (γ43 = −0.002; STE = −0.021). Older participants showed a less strong within-person association between depressive symptoms and subjective memory (γ46 = 0.002; STE = 0.022).

In a final step we examined whether memory performance or depressive symptoms was a better predictor of subjective memory, by comparing proportional reductions in prediction error (Snijders & Bosker, 1998) in models that included either memory performance or depressive symptoms as a predictor of subjective memory at the between-person and within-person levels. Memory performance and depressive symptoms predicted subjective memory about equally well: The proportional reduction in error variance amounted to 12.4% for the model including memory performance, and to 13.6% for the model including depressive symptoms.

We conducted two sets of follow-up analyses to check on potential confounds. Our first set of follow-up analyses aimed at determining whether our findings at the within-person level were confounded by our choice of centering at the mean of an individual’s time series. In a first step, we de-trended the time series for subjective memory, memory performance, and depressive symptoms on an individual-by-individual basis to obtain person-specific intercepts, and linear and quadratic trends across time in study. For memory performance, we also controlled for retest. Because we did not use the waves 1992 to 1994 due to differences in the assessment of memory performance, no baseline data without retest was available for a large number of participants Therefore, we coded the first occasion of the HRS participation as 1 (no retest) and other occasions as 0 (retest) for participants for whom the baseline assessment was available. This allowed removing the effect of having no practice at baseline from their time series. From there, we estimated the within-person portion of our analytical model using these de-trended data. The follow-up analysis confirmed the presence of the within-person associations in the original (simultaneous) modeling framework. Subjective memory was coupled with memory performance (γ30 = 0.017; STE = 0.015) and depressive symptoms (γ40 = −0.042; STE = −0.046) at the within-person level. Individuals with more functional limitations were more sensitive to alterations of memory performance (γ33 = 0.002; STE = 0.018) and depressive symptoms (γ43 = −0.001; STE = 0.011). Older participants were less sensitive to alterations of depressive symptoms (γ46 = 0.002; STE = 0.022). We take the findings from the follow-up analyses to indicate that our findings at the within-person level are not solely methodological artifacts and can be interpreted substantively.

Our second set of follow-up analyses aimed at controlling for the number of measurement occasions each participant provided. Individuals who participated in the HRS for a longer time period can be expected to show more pronounced changes in the relevant constructs. Thus, we included number of observations as a correlate of the intercept and time-related changes in subjective memory. We also included interaction terms of this correlate with average memory performance and chronic depressive symptoms, as well as with occasion-specific memory performance and occasion-specific depressive symptoms. The pattern of findings from this model controlling for individual differences in number of available observations was the same as the pattern of findings reported in Table 3.

In order to replicate previous findings on the between-person association of changes in subjective memory and memory performance (e.g., Mascherek & Zimprich, 2011; Parisi et al., 2011), we also ran a latent growth curve analysis to model linear changes in subjective memory, memory performance, and depressive symptoms (adjusted for correlates) with the Mplus program (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012), ignoring the issue of within-person coupling of residuals off of the best fitting linear slopes. The model fitted the data well (CFI = 0.982; RMSEA = 0.017; SRMR = 0.052). Intercepts of subjective memory and memory performance, indicating levels of these variables at the middle of an individual’s time series were positively correlated (r = 0.219; p < 0.001). Slopes of subjective memory and memory performance, indicating the rates of linear change in these variables were positively correlated as well (r = 0.243; p < 0.001). Intercepts and slopes of subjective memory and depressive symptoms were also correlated (r = −0.227; p < 0.001, and, r = −0.405; p < 0.001; respectively). These analyses indicated, then, that between-person differences in long-term intraindividual change in these three variables were indeed correlated.

Discussion

Our goal in the present study was to examine between-person and within-person associations of subjective memory with memory performance and depressive symptoms and to explore potential moderators of these associations using longitudinal data from a large national sample in the US (HRS data from 27,395 participants across nine measurement waves collected over 17 years). Our findings on between-person associations largely corroborate existing findings. Individuals with better memory performance and fewer depressive symptoms tend to rate their memory more favorably (STE = 0.192 for memory performance; STE = −0.207 for depressive symptoms). At the within-person level, we found that fluctuations in individuals’ subjective memory ratings are, on average, coupled with fluctuations in memory performance and depressive symptoms. When the typical participant had better memory performance or fewer depressive symptoms than usual, he or she was also more likely to provide a higher rating of subjective memory. These associations were of small and comparable magnitude for memory performance and depressive symptoms.

In a previous study, Pearman et al. (in press) found no evidence of systematic long-term change in subjective memory and no slope-slope covariance of memory performance with subjective memory. However, they did find that the occasion-specific residuals in their longitudinal panel data were correlated. This occasion-specific residual correlation might be explained by an occasion-specific intraindividual coupling of the type observed in this study. Although occasion-specific deviations from long-term trends are typically treated as measurement error, our findings suggest that these occasion-specific deviations are related to subjective memory. For example, two individuals, who show similar long-term trajectories of memory performance, could differ in the amount of variation they show around these trajectories at specific time points. By taking these occasion-specific fluctuations of memory performance into account, one can make more specific predictions about the current state of these individuals in related constructs, such as subjective memory. An implication that arises from such within-person associations is that clinical recommendations should also take within-person variations into account.

We do not yet know what explains the within-person coupling of subjective memory and depressive symptoms, but there are several candidate explanations. Clinical depression is associated with an increased elaboration of and with difficulties disengaging from negative information (for a review, see Gotlib & Joormann, 2010). Thus, depression might lead to an increased attention and concern for memory problems in everyday life and, thereby, negatively influence subjective perceptions of memory functioning. For example, a typical everyday memory problem, such as not remembering where one has placed an object, might be interpreted more negatively by a person when they are frustrated or under stress (e.g., Garrett, Grady, & Hasher, 2010), or when they are prone to perceiving the instance of forgetting as an indicator of serious memory-related problems such as Alzheimer’s disease (e.g., Cutler & Hodgson, 1996). Our results suggest that this hypothesis should be examined more carefully at the within-person level. Our findings further suggest that depressive symptoms do not play a substantive role for all older adults in explaining fluctuations of subjective memory at the population level (this may of course differ for sub-populations suffering from depression). A total of 4,175 participants (15.2 % of our sample) reported no depressive symptoms throughout all of the observations used in the present study. Approximately half of our sample (14,210 participants; 51.9 %) reported a maximum of up to 2 symptoms. For the average person in our study, the average intraindividual standard deviation of depressive symptoms amounted to 1.098 symptoms, suggesting that the average person’s reports varied by a little more than one symptom and the majority of the sample was probably not clinically depressed. Thus, we note that large fluctuations in depressive symptoms are not the normative case for the older adults in this sample.

Correlates of Subjective Memory

In line with previous research (e.g., Cutler & Grams, 1998; Herzog & Rodgers, 1989; Zelinski et al., 2001), more education and fewer functional limitations were associated with higher ratings of subjective memory. Gender differences were rather small (STE = 0.033) and suggestive of sampling differences rather than inherent differences. Unexpectedly, we found that older participants reported higher levels of subjective memory. Follow-up analyses indicated that this effect only emerged when other correlates, including time, were added into the model. The average age of participants was negatively related to subjective memory in a model only including average age as a correlate. Several interpretations appear possible. To begin with, older adults may shift their standards or expectations as incidents of forgetting become more commonplace. That is, concerns about memory aging may become less salient after the transition from middle to old age (e.g., Rabbitt, Maylor, McInnes, Bent, & Moore, 1995), a phenomenon also seen in the subjective health literature (e.g., Idler, 1993). However, because we controlled for changes across time, average age across the study might also reflect age-related sample selection bias (Singer, Verhaeghen, Ghisletta, Lindenberger, & Baltes, 2003): By the 2010 wave, n = 9,561 participants from our sample (34.9%) had deceased (average age at death: M = 79.91, SD = 10.32). The median age at death was 81 years, indicating that about half of the deceased participants had died before reaching the age of 81 years. Individuals surviving into higher ages might be a select subsample.

Between-Person Differences in Associations of Subjective Memory with Memory Performance and Depressive Symptoms

In the present study, we explored potential moderators of the between-person and within-person associations of subjective memory with memory performance and depressive symptoms. Men and those with more education had a stronger between-person association between subjective memory and memory performance. The moderating effect of education is in line with previous research (Zelinski et al., 2001), and might indicate that those with more education have more experience in between-person cognitive comparisons, a factor that has been found to increase the accuracy of self-evaluations of ability (for a review, see Mabe & West, 1982). Likewise, limitations in educational and occupational opportunities (Moen, 1996) might have left the women in our sample with fewer opportunities for between-person cognitive comparisons. Moderator effects were also found at the within-person level: First, subjective memory ratings became more dependent on actual memory performance over time. Over time individuals might have (a) accumulated more experience in within-person comparison in a range of cognitively demanding activities (possibly even through participation in this study), and (b) experienced more extensive cognitive declines (e.g. Baltes et al., 1999; Schaie, 2005), changes that were more likely to be noticed. Second, perceived memory functioning of older individuals was less prone to alterations of depressive symptoms, suggesting less vulnerability to fluctuations. Third, subjective memory ratings of participants suffering from functional limitations depended more on their current memory performance and depressive symptoms, suggesting that these individuals may monitor their current state more closely.

Limitations and Outlook

In closing, we note several limitations of our report. To begin with, as is the case for many broadly-cast surveys, the HRS includes only brief measures of the relevant constructs. Although it is reassuring that our report replicated findings obtained in studies with multiple-item scales and tasks, future research should replicate these findings with more comprehensive measures of the key constructs. The HRS only included a single, Likert-scaled item to assess subjective memory. This precluded examinations of whether the subjective memory measure is measurement invariant across the time period of 17 years and across the wide age range of the participants. Also, single-item measures may not be very sensitive to detect subtle changes in the underlying phenomenon and can thus be expected to constrain the range of variability observed. In order to reduce the complexity of our models, we examined functional limitations as a between-person trait variable. Given the link between functional limitations and subjective memory reported in previous research (e.g. Herzog & Rodgers, 1989) and in the present study, it could be expected that within-person fluctuations in functional limitations might relate to subjective memory as well.

Second, our report included participants from a large national sample of the US population. The incidence of individuals seeking professional help for self-reported memory problems is increasing. For example, recent epidemiological findings show that 12.7% of persons aged ≥ 60 years reported increased confusion or memory loss in the preceding year (Adams, Deokar, Anderson, & Edwards, 2013). Future research should examine whether perception of subjective memory functioning is a predictor of actual memory problems in these individuals (Hertzog & Pearman, 2014). Also, our choice of centering at the middle of an individual’s time series implied that epochal or cohort effects remained constant. For example, for some individuals the center of their time series might have been in 1998 while for others it was in 2009. Given previous reports of cohort differences in memory performance (e.g., Hülür et al., 2013), future research should examine whether subjective memory and its associations with memory performance and depressive symptoms differ across cohorts.

Third, the availability of up to nine measurement waves in the HRS provided a unique opportunity to examine within-person couplings. However, couplings at the bi-yearly time scale may not generalize to coupling at other (faster) time scales. For example, previous research on depression and cognition (for a review, see Gotlib & Joormann, 2010) suggests that individuals who experience more depressive symptoms might be more concerned with memory problems in everyday life. Future research should examine within-person associations of subjective memory and memory performance on a daily level, and how depressive symptoms moderate this association. For example, it is possible that individuals experiencing more depressive symptoms are more sensitive for circadian or day-to-day fluctuations in memory performance because they may interpret downward deviations from their average more negatively than others due to a higher negative cognitive bias (Broomfield, Davies, MacMahon, Ali, & Cross, 2007; Gotlib & Joormann, 2010). Future studies might also include a clinical interview to actually diagnose clinical depression as a way of teasing apart “normal” fluctuations in affect and actual depressive symptomatology. For instance, reporting low energy over the past two weeks might represent an ongoing life stressor rather than a clinical depressive symptom.

Conclusions

The current study adds to previous work by showing small associations of subjective memory with memory performance and depressive symptoms at both the between-person and within-person levels. By taking advantage of the availability of multiple occasions of measurement, we showed both that (a) between-person latent growth curve slopes of subjective memory were correlated with slopes of change in memory performance and depressive symptoms, and also that (b) controlling for long-term trends, within-person variability around a person’s slope of subjective memory change was associated with occasion-specific fluctuations in memory and depressive symptoms. The between-person and within-person associations of subjective memory were of small and comparable magnitude for memory performance and depressive symptoms. We take these findings to suggest that subjective perceptions of memory functioning partly derive from the monitoring of current memory performance, but also reflect the influence of other fluctuating variables, such as depressive symptoms.

Acknowledgments

The Health and Retirement Study was supported by a cooperative agreement (Grant U01 AG09740) between the NIA and the University of Michigan. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the National Institute on Aging Grants R21-AG032379, R21-AG033109, and RC1-AG035645. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Contributor Information

Gizem Hülür, Email: gizem.hueluer@hu-berlin.de.

Christopher Hertzog, Email: christopher.hertzog@psych.gatech.edu.

Ann Pearman, Email: apearman6@mail.gatech.edu.

Nilam Ram, Email: nilam.ram@psu.edu.

Denis Gerstorf, Email: denis.gerstorf@hu-berlin.de.

References

- Adams ML, Deokar AJ, Anderson LA, Edwards VJ. Self-reported increased confusion or memory loss and associated functional difficulties among adults aged ≥ 60 years — 21 states, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62:347–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, Staudinger UM, Lindenberger U. Lifespan psychology: Theory and application to intellectual functioning. Annual Review of Psychology. 1999;50:471–507. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin M, Desrichard O. Are memory self-efficacy and memory performance related? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137:211–241. doi: 10.1037/a0022106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielak AAM, Hultsch DF, Strauss E, MacDonald SWS, Hunter MA. Intraindividual variability is related to cognitive change in older adults: Evidence for within-person coupling. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25:575–586. doi: 10.1037/a0019503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Laurenceau J-P. Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research. New York: Guilford; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brose A, Schmiedek F, Lövdén M, Molenaar PCM, Lindenberger U. Adult age differences in covariation of motivation and working memory performance: Contrasting between-person and within-person findings. Research in Human Development. 2010;7:61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Broomfield NM, Davies R, MacMahon K, Ali F, Cross SM. Further evidence of attention bias for negative information in late life depression. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;22:175–180. doi: 10.1002/gps.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Crane MK, Bogner HR, Brown GK, Gallo JJ. The link between depressive symptoms, negative cognitive bias and memory complaints in older adults. Aging & Mental Health. 2007;11:708–715. doi: 10.1080/13607860701368497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler SJ, Grams AE. Correlates of self-reported everyday memory problems. Journals of Gerontology. 1988;43:S82–S90. doi: 10.1093/geronj/43.3.s82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler SJ, Hodgson LG. Anticipatory dementia: a link between memory appraisals and concerns about developing Alzheimer’s disease. The Gerontologist. 1996;36:657–664. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.5.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RA, Hultsch DF. Structure and development of metamemory in adulthood. Journal of Gerontology. 1983;38:682–688. doi: 10.1093/geronj/38.6.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett DD, Grady CL, Hasher L. Everyday memory compensation: The impact of cognitive reserve, subjective memory, and stress. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25:74–83. doi: 10.1037/a0017726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstorf D, Hoppmann CA, Kadlec KM, McArdle JJ. Memory and depressive symptoms are dynamically linked among married couples: Longitudinal evidence from the AHEAD Study. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1595–1610. doi: 10.1037/a0016346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilewski MJ, Zelinski EM, Schaie KW. The Memory Functioning Questionnaire for assessment of memory complaints in adulthood and old age. Psychology and Aging. 1990;5:482–490. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Joormann J. Cognition and depression: current status and future directions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:285–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow LL, Mulaik SA, Steiger JH, editors. What if there were no significance tests? Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzog C, Dixon RA, Hultsch DF. Relationships between metamemory, memory predictions, and task performance in adults. Psychology and Aging. 1990;5:215–227. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzog C, Dixon RA, Hultsch DF. Intraindividual change in text recall in the elderly. Brain and Language. 1992;42:248–269. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(92)90100-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzog C, Pearman AM. Memory complaints in adulthood and old age. In: Perfect TJ, Lindsay D. Stephen, editors. Handbook of Applied Memory. London, England: Sage; 2014. pp. 423–443. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzog C, Schaie KW. Stability and change in adult intelligence: 1. Analysis of longitudinal covariance structures. Psychology and Aging. 1986;1:159–171. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.1.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog AR, Rodgers WL. Age differences in memory performance and memory ratings as measured in a sample survey. Psychology and Aging. 1989;4:173–182. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.4.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog AR, Wallace RB. Measures of cognitive functioning in the AHEAD Study. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1997;52B:37–48. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.special_issue.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hülür G, Infurna FJ, Ram N, Gerstorf D. Cohorts based on decade of death: No evidence for secular trends favoring later cohorts in cognitive aging and terminal decline in the AHEAD study. Psychology and Aging. 2013;28:115–127. doi: 10.1037/a0029965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL. Age differences in self-assessments of health: age changes, cohort differences, or survivorship? Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1993;48:S289–S300. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.6.s289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RL, Zarit SH, Hilbert NM, Niederehe GA. Memory complaint and impairment in the aged: The effect of depression and altered brain function. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1975;32:1560–1573. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760300107009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killeen PR. An alternative to null hypothesis statistical tests. Psychological Science. 2005;16:345–353. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01538.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Agrigoroaei S. Low perceived control as a risk factor for episodic memory: The mediational role of anxiety and task interference. Memory and Cognition. 2012;40:287–296. doi: 10.3758/s13421-011-0140-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane CJ, Zelinski EM. Longitudinal hierarchical linear models of the memory functioning questionnaire. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:38–53. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampe IK, Heeren TJ. Is apathy in late-life depressive illness related to age-at-onset, cognitive function or vascular risk? International Psychogeriatrics. 2004;16:481–486. doi: 10.1017/s1041610204000766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD, Schabenberger O. SAS for mixed models. 2nd edition. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. New York: J. Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Mabe PA, West SG. Validity of self-evaluation of ability: A review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Applied Psychology. 1982;67:280–296. [Google Scholar]

- Mascherek A, Zimprich D. Correlated change in memory complaints and memory performance across 12 years. Psychology & Aging. 2011;26:884–889. doi: 10.1037/a0023156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ. Dynamic but structural equation modeling of repeated measures data. In: Nesselroade JR, Cattell RB, editors. The handbook of multivariate experimental psychology. Vol. 2. New York: Plenum Press; 1988. pp. 561–614. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Fisher GG, Kadlec KM. Latent variable analyses of age trends from the Health and Retirement Study, 1992–2004. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22:525–545. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.3.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald-Miszczak L, Hertzog C, Hultsch DF. Stability and Accuracy of Metamemory in Adulthood and Aging: A Longitudinal Analysis. Psychology and Aging. 1995;10:553–564. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.10.4.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta M, Whyte E, Lenze E, Hardy S, Roumani Y, Subashan P, Huang W, Studenski S. Depressive symptoms in late life: associations with apathy, resilience and disability vary between young–old and old–old. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;23:238–243. doi: 10.1002/gps.1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moen P. Gender, age, and the life course. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. fourth edition. New York: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 230–238. [Google Scholar]

- Molenaar PCM. On the necessity to use person-specific data analysis approaches in psychology. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2013;10:29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Molloy LE, Ram N, Gest SD. Development and lability in early adolescents’ self-concept: Within- and between-person variation. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:1589–1607. doi: 10.1037/a0025413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoellgen I, Morack J, Infurna FJ, Ram N, Gerstorf D. Health sensitivity of older adults: Corresponding ups and downs of individuals’ well-being and health. 2014 Manuscript under review. [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Spahn F, Hock J. Clinical presentation of depression in the elderly. Gerontology. 1994;40:10–14. doi: 10.1159/000213615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nagi SZ. Disability and rehabilitation: legal, clinical, and self-concepts and measurement. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Nagi SZ. An epidemiology of disability among adults in the United States. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly/Health and Society. 1976;54:439–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesselroade JR. The warp and the woof of the developmental fabric. In: Downs R, Liben L, Palermo DS, editors. Visions of aesthetics, the environment, & development: The legacy of Joachim F. Wohlwill. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1991. pp. 213–240. [Google Scholar]

- Ofstedal MB, Fisher GG, Herzog AR. Documentation of cognitive functioning measures in the Health and Retirement Study. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; 2005. (HRS/AHEAD Documentation Report DR-006) [Google Scholar]

- Parisi JM, Gross AL, Rebok GW, Saczynski JS, Crowe M, Cook SE, Unverzagt FW. Modeling change in memory performance and memory perceptions: Findings from the ACTIVE study. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26:518–524. doi: 10.1037/a0022458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearman A, Hertzog C, Gerstorf D. Little evidence for links between memory complaints and memory performance in very old age: Longitudinal analyses from the Berlin Aging Study. Psychology and Aging. 2014;29:828–842. doi: 10.1037/a0037141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearman A, Storandt M. Predictors of subjective memory in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences. 2004;59B:P4–P6. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.1.p4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbitt P, Maylor E, McInnes L, Bent N, Moore B. What goods can self-assessment questionnaires deliver for cognitive gerontology? Applied Cognitive Psychology. 1995;9:S127–S152. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ram N, Conroy D, Pincus AL, Lorek A, Rebar AH, Roche MJ, Morack J, Coccia M, Feldman J, Gerstorf D. Examining the interplay of processes across multiple time-scales: Illustration with the Intraindividual Study of Affect, Health, and Interpersonal Behavior (iSAHIB) Research in Human Development. 2014;11:142–160. doi: 10.1080/15427609.2014.906739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram N, Rabbitt P, Stollery B, Nesselroade JR. Cognitive performance inconsistency: Intraindividual change and variability. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20:623–633. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.4.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson WS. Ecological correlations and the behavior of individuals. American Sociological Review. 1950;15:351–357. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers WL, Miller B. A comparative analysis of ADL questions in surveys of older people. Journals of Gerontology, Social Sciences. 1997;52B:21–36. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.special_issue.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaie KW. What can we learn from longitudinal studies of adult intellectual development. Research in Human Development. 2005;2:133–158. doi: 10.1207/s15427617rhd0203_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiedek F, Lövdén M, Lindenberger U. Keeping it steady: Older adults perform more consistently on cognitive tasks than younger adults. Psychological Science. 2013;24:1747–1754. doi: 10.1177/0956797613479611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz JE, Stone A. The analysis of real-time momentary data: A practical guide. In: Stone AA, Shiffman SS, Nebeling L, editors. The science of real-time data capture: self-report in health research. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 76–113. [Google Scholar]

- Singer T, Verhaegen P, Ghisletta P, Lindenberger U, Baltes PB. The fate of cognition in very old age: Six-year longitudinal findings in the Berlin Aging Study (BASE) Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:318–331. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinski MJ. Approaches to modeling intraindividual and interindividual facets of change for developmental research. In: Fingerman KL, Berg CA, Smith J, Antonucci TC, editors. Handbook of life-span development. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinski M, Buschke H. Cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships among age, memory and processing speed. Psychology and Aging. 1999;14:18–33. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.14.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinski M, Buschke H. Modeling intraindividual cognitive change in aging adults: Results from the Einstein Aging Studies. Aging, Neuropsychology and Cognition. 2004;11:196–211. [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinski MJ, Scott SB. Boundary conditions for emotional well-being in aging: The importance of daily stress. In: Verhaeghen P, Hertzog C, editors. Emotion, social cognition, and everyday problem-solving during adulthood. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2014. pp. 128–141. [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinski MJ, Smyth JM, Hofer SM, Stawski RS. Intraindividual coupling of daily stress and cognition. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21:545–557. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.3.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. London, England: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Soldo B, Hurd M, Rodgers W, Wallace R. Asset and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old: An overview of the AHEAD study. Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1997;52:P1–P20. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.special_issue.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. State-Trait Depression Scales. Palo Alto, CA: Mind Garden; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Stawski RS, Sliwinski MJ, Hofer SM. Between-person and within-person associations among processing speed, attention switching, and working memory in younger and older adults. Experimental Aging Research. 2013;39:194–214. doi: 10.1080/0361073X.2013.761556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Terracciano A, Milaneschi Y, An Y, Ferrucci L, Zonderman AB. The trajectory of depressive symptoms across the adult life span. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:803–811. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorvaldsson V, Skoog I, Hofer SM, Börjesson-Hanson A, Ostling S, Sacuiu S, Johansson B. Nonlinear blood pressure effects on cognition in old age: Separating between-person and within-person associations. Psychology and Aging. 2012;27:375–383. doi: 10.1037/a0025631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace RB, Herzog AR, Ofstedal MB, Steffick DC, Fonda S, Langa K. Documentation of affective functioning measures in the Health and Retirement Study. Ann Arbor: Survey Research Center, University of Michigan; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zelinski EM, Burnight KP, Lane CJ. The relationship between subjective and objective memory in the oldest old: comparisons of findings from a representative and a convenience sample. Journal of Aging and Health. 2001;13:248–266. doi: 10.1177/089826430101300205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelinski EM, Gilewski MJ. A 10-item Rasch modeled memory self-efficacy scale. Aging and Mental Health. 2004;8:293–306. doi: 10.1080/13607860410001709665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]