Abstract

Neural prostheses have become ever more acceptable treatments for many different types of neurological damage and disease. Here we investigate the use of two different morphologies of titania nanotube arrays as interfaces to advance the longevity and effectiveness of these prostheses. The nanotube arrays were characterized for their nanotopography, crystallinity, conductivity, wettability, surface mechanical properties and adsorption of key proteins: fibrinogen, albumin and laminin. The loosely packed nanotube arrays fabricated using a diethylene glycol based electrolyte, contained a higher presence of the anatase crystal phase and were subsequently more conductive. These arrays yielded surfaces with higher wettability and lower modulus than the densely packed nanotube arrays fabricated using water based electrolyte. Further the adhesion, proliferation and differentiation of the C17.2 neural stem cell line was investigated on the nanotube arrays. The proliferation ratio of the cells as well as the level of neuronal differentiation was seen to increase on the loosely packed arrays. The results indicate that loosely packed nanotube arrays similar to the ones produced here with a DEG based electrolyte, may provide a favorable template for growth and maintenance of C17.2 neural stem cell line.

Keywords: titania nanotube arrays, C17.2 neural stem cell line, neural prostheses, neurons, astrocytes

1. Introduction

Neural prostheses have become ever more acceptable treatments for many different types of neurological damage and disease. There are three main types of neural prostheses. Auditory and visual prostheses can act on various neural populations in an attempt to emulate the natural signaling from the auditory or visual pathways [1–4]. Sensory and motor control prostheses are fully implantable complex electrical arrays often referred to as brain machine interfaces (BMIs). They are used to translate neuronal activity across damaged neural networks in order to restore sensation and motor control in limbs [5–7]. Cognitive prostheses electrically stimulate deep lying brain structures to alleviate symptoms of neurodegenerative diseases [8–10]. For example, Parkinson’ disease is one of the most common neurodegenerative diseases which results in the loss of movement control and coordination, it is predicted to affect between 8.7 and 9.3 million people world wide by 2030 [11, 12]. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a form of cognitive prostheses used in the treatment of Parkinson’ disease. DBS works through electrical stimulation at 1–5V 120–180Hz, and pulse width’s of 60–200μs in order to interfere with the overactive signaling triggered by dopamine depletion in the degenerative neural population [13, 14]. However the longevity and effectiveness of these prostheses are reduced as a result of the immune response. The response occurs in the form of a compact sheath of glial cells around the prostheses, which electrically segregates it from the target neurons by 50–200μm [15, 16]. This is referred to as glial encapsulation or reactive gliosis. It is the result of the initial trauma from prostheses implantation, as well as the recognition of the prostheses surface as a foreign body by the cells. Gliosis is recognized by the increased expression of proteins specific to astrocytes and astroglia, which are know to assist in the formation of the blood brain barrier, and play a role in the repair and scarring of neural tissue after trauma [17–19]. The encapsulation of the prostheses by these cells drastically limits electrical signaling as the neurons are forced further away from the surface of prostheses [20]. In attempt to reduce gliosis, different prosthesis geometries, size, and surface roughness’s have been examined, with device size having the most significant affect by reducing the volume disturbed during implantation [16]. Nanotopographies such as nanotubes have already been shown to improve cell adhesion and growth of cells [21]. Studies have shown that nanoporous silicon promotes neuronal adhesion while limiting gliosis [22]. Submicron machining on the order of 10–70nm has been shown to direct neurite outgrowth [23, 24]. Despite these advancements, there is still a need to develop robust interfaces that increase prostheses effectiveness and longevity.

Titanium has proven biocompatibility and has been used for a variety of biomedical applications. Although it is not often used in neurological applications, its ability to be produced as thin films on other materials makes it a good candidate for neurological applications. Even in its thin film form, titanium surfaces can be modified to produce a variety of nanoarchitectures. Using different techniques such as hydrothermal and electrochemical anodization, different nanotopographies of titania such as particles, rods, tubes, dendrites, and flower like structures have been produced [25–27]. Many of these surfaces have robust and favorable mechanical and electrical properties and have been used for different biomedical and energy applications. For example, titania nanotubes arrays have been used to improve the efficiency of dye-sensitized solar cells by permitting charge transfer along their length, reducing energy loss [28]. Anodization parameters such as electrolyte solution, voltage, and time can be varied to alter the nanotube array diameter, length and density [28, 29]. Other parameters such as annealing temperature can be adjusted to alter their mechanical and electrical properties [30]. Furthermore, these nanotube arrays have been shown to provide a favorable template for the growth of stem cells such as the differentiation of multipotent stem cells into osteoblasts [31]. They have even been shown to reduce immune response by lowering platelet adhesion and activation [32].

In this work, we have investigated the potential of titania nanotube arrays as interfaces for neural prostheses. Two different nanotube morphologies were investigated: highly oriented, densely packed nanotube arrays with individual nanotubes adjacent to each other; and loosely packed nanotube arrays with individual nanotubes forming clusters or anemone-like structures. The nanotube array morphology, crystallinity, conductivity, wettability, and mechanical properties were investigated with the use of scanning electron microscopy (SEM), glancing angle x-ray diffraction (GAXRD), four-point probe (4PP), contact angle goniometry, and nanoindentation respectively. The adsorption of key proteins: fibrinogen, albumin and laminin were investigated using biochemical assays. The C17.2 neural stem cell line was used to investigate cellular functionality on these nanotube arrays. This neural stem cell line has been shown to retain its ability to differentiate into neurons and astrocytes as well as express relevant levels of nerve growth and neurotrophic factors under culture conditions [33, 34]. Cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation were investigated up to 7 days of culture using fluorescence and immunofluorescence microscopy. The results presented here suggest that the nanotopography and material properties influence cellular functionality with loosely packed nanotube arrays fabricated using a DEG based electrolyte may provide a favorable interface for neural prostheses, warranting further investigation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Fabrication of titania nanotube arrays

Commercially pure titanium foil (0.25mm, 95%, Titanium Joe Inc.) was cut into rectangular substrates of 2cm × 2.5cm. These substrates were cleaned in acetone, soap, and isopropyl alcohol. Titania nanotube arrays were fabricated on these substrates using an electrochemical anodization process previously described [28, 35, 36]. An electrochemical cell was developed with the titanium substrates acting as the anode, and platinum foil acting as the cathode (Figure 1). Two different electrolytes were used for anodization:

Figure 1.

Schematic of electrochemical anodization set-up with titanium anode and platinum cathode placed within a fluorinated electrolyte solution.

A water-based electrolyte composed of 1% v/v hydrofluoric acid solution (HF, 48% v/v stock solution) in deionized (DI) water. Anodization was carried out at 20V for 3.5hrs to form titania nanotube arrays (NT-H2O).

A diethylene glycol (DEG)-based electrolyte composed of 95% v/v DEG (99.7% v/v stock solution) with 2% v/v HF (48% v/v stock solution) in DI water. Anodization was carried out at 60V for 23hrs to form titania nanotube arrays (NT-DEG).

All experiments were carried out at room temperature (RT). Following anodization, the nanotube arrays were rinsed 3 times with DI water and dried with nitrogen gas. The nanotube arrays were then annealed in ambient oxygen at 530°C at a ramp rate of 15°C/min for 3hrs (NT-H2O) or 5hrs (NT-DEG) to stabilize them.

2.2 Characterization of titania nanotube arrays

The surface morphology was characterized using SEM (JEOL JSM 6500F) to ensure surface uniformity, and to determine the nanotube diameter and length. The nanotube lengths were measured after delamination by bending the substrate to access the cross-sectional profile. A 10nm layer of gold was deposited on the substrates prior to imaging at 15kV.

The presence of anatase and rutile crystal phases was detected through GAXRD (Bruker D8). XRD scans were collected at θ=1.5° and 2θ ranges were chosen based on significant peak intensities. Detector scans were run at a step size of 0.01 with a time per step of 1sec. Peaks were filtered and correlated to crystal structures using DIFFRACT.EVA software and values from the International Center for Diffraction Data.

In order to evaluate the conductivity of the titania nanotube arrays, they were further modified such that half of the substrate had the titania nanotube array morphology with the other half being etched to expose the underlying titanium substrate. The surfaces were then coated with 40nm of gold to form ohmic contacts. A 4PP was placed on to the ohmic contacts with a voltage and a current probe on each half of the substrate (Figure 2). The distance between the probes was approximately 7mm. A voltage was applied and current was measured to produce a current-voltage plot that was further processed using Ohm’ s law to calculate the conductance from the slope.

Figure 2.

Schematic of 4PP device used to measure the conductance of titania nanotube arrays, comprised of a voltage probe and current probe on the nanotube array surface and the etched titanium surface coated with gold to form ohmic contacts. Current was measured as a potential was applied.

Surface wettability or contact angles were measured using the static sessile water-drop method on a contact angle goniometer (Rame-hart 250). A predetermined volume of water was dropped onto the surfaces and images of the water droplet were immediately captured. The images were analyzed to determine the contact angles. The contact angles were correlated to surface energy using the following equation [37]:

where Es is the surface energy, Elv = 72.8 mJ/m2 (energy of liquid/vapor interface) at 20°C for DI water, and θ represents the static contact angle.

Nanoindentation was performed using a Nanoindenter (XP, MTS) with a spherical tip of 100-micron radius (for measuring the elastic modulus), and a Berkovich tip (for measuring hardness). Indentations were made under two conditions: 1 load-unload cycle reaching a maximum applied load of 1mN, and a set of 6 loading cycles doubling from 1.25mN to 50mN. The elastic modulus was calculated based off the spherical tip indentation using the Oliver and Pharr method [38]:

where Eeff is the effective elastic modulus, E is the elastic modulus of the material, Ei is the elastic modulus of indenter material and ν is the Poisson’s ratio. The hardness was calculated based off the Berkovich tip indentations using the Oliver and Pharr method [38]:

Where, H is the hardness, Pmax is the maximum load and A is the cross-sectional area.

2.3 Protein adsorption on titania nanotube arrays

To understand how proteins adsorb on titania nanotube arrays; fibrinogen (Sigma), albumin (Sigma), and laminin (BD Biosciences) adsorption was investigated. All substrates were cut into squares of 1cm × 1cm. They were then sterilized by incubation in 70% ethanol for 30mins followed by 3 rinses in phosphate buffer solution (PBS, 10×) and 30mins of UV exposure. Following sterilization the substrates were incubated in 100μg/mL of protein solutions in 24 well plates on a horizontal shaker plate at 100 rpm at RT for 2hrs. The protein solution was aspirated and the substrates were rinsed 2 times with PBS. They were then incubated in 1% v/v sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, Sigma) solution in PBS on a shaker plate at 100 rpm for 4hrs to desorb the proteins. The protein concentrations in this solution were measured using a commercially available micro-BCA assay (Pierce Biotechnology) and a plate reader (BMG Labtech).

2.4 C17.2 cell culture

Murine neural stem cell-like subclone C17.2 generously provided by Dr. Evan Y. Snyder’s group at the Sanford Burnham Medical Research Institute were used in this study. C17.2 cells were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in 100mm × 20mm polystyrene vented tissue-culture petri dishes. A growth media consisting of DMEM containing high glucose (4500mg/L), L-glutamine and sodium pyruvate, and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 5% horse serum, 1% L-glutamine and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin/Fungazone was used. Cells of passage 3 were used for subsequent studies. Prior to seeding the cells, the substrates were incubated in 70% ethanol for 30mins followed by 2 rinses in PBS and 30mins of UV exposure. The cells were seeded onto substrates at a concentration of 1500 cells/well in 24 well plates and were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2.

2.5 C17.2 adhesion and proliferation on titania nanotube arrays

The C17.2 cell response was investigated after 1, 4 and 7 days of culture in growth media. Cell adhesion and proliferation were evaluated by staining the cells with 5-chloromethylfluorescein diacetate (CMFDA, Life Technologies), rhodamine phalloidin, and 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Invitrogen) to visualize cytoplasm, cytoskeleton, and nucleus respectively using a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss). Prior to staining unadhered cells were aspirated and the substrates were gently rinsed 2 times with PBS before being transferred to a new 24-well plate. The substrates were then incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 in a 10μM solution of CMFDA in PBS for 45mins. Following this incubation, the solution was aspirated and the substrates were incubated in growth media at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 30mins. The media was then aspirated and the substrates were rinsed once in PBS before being transferred to a new 24-well plate where the cells were fixed in a 3.7% w/v formaldehyde solution in DI water for 15mins at RT. The fixative was then aspirated and the substrates were rinsed 3 times in PBS for 5mins per rinse before being transferred to a new 24-well plate. The cells were permeablized in a 1% v/v Triton-X solution in water for 3mins at RT. The permeative was aspirated and the substrates were rinsed and transferred to a new 24 well plate where they were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 in a 5μL/mL rhodamine-phalloidin solution in DI water for 25mins at RT before DAPI was added to the solution at a concentration of 1μL/mL and were incubated for additional 5mins. The solution was then aspirated and the substrates were rinsed 2 times in PBS before being stored in PBS in a light resistant container at 20°C until imaging. Analysis of the fluorescence images was performed with ImageJ software.

2.6 Differentiation marker protein expression and cell morphology on titania nanotube arrays

C17.2 cell differentiation was investigated after 7 days of culture in differentiation media. The cells were initially seeded in growth media, which was then replaced with differentiation media after 1 day of culture. The differentiation media was formulated to encourage differentiation towards astrocytic and neuronal lineages [39]. The media consisted of a 1:1 ratio of DMEM containing high glucose (4500mg/L), L-glutamine, sodium pyruvate, and Ham’s F-12 Nutrient Mixture; and supplemented with 1% L-glutamine, 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin/Fungazone, N-2 supplement, glial derived neurotropic factor (GDNF, 10ng/mL) and nerve growth factor (NGF, 10ng/mL).

After 4 and 7 days of culture, indirect immunofluorescence staining was performed to measure the level of cellular differentiation through marker protein expression. The C17.2 cells were immunostained for the presence of neuronal marker: light neuroflilament (NF-L), astrocyte marker: aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member L1 (ALDH1L1), and neural precursor: Nestin.

Prior to staining, unadhered cells were aspirated and the substrates were gently rinsed 2 times with PBS before being transferred to a new 24-well plate where they were fixed using a 3.7% w/v formaldehyde solution in DI water for 15mins at RT. The fixative was then aspirated and the substrates were rinsed 3 times in PBS for 5mins per rinse before being transferred to a new 24-well plate. The cells were permeablized in a 1% v/v Triton-X solution in water for 3mins at RT. The permeative was aspirated and the substrates were rinsed and transferred to a new 24 well plate where they were incubated in 10% blocking serum in PBS for 30mins at RT to block any non-specific binding. The substrates were then rinsed and transferred to a new 24-well plate and incubated at 20°C overnight in a primary antibody solution of either NF-L or ALDH1L1 (rabbit polyclonal, 1:1000, Neuromics) with Nestin (mouse monoclonal, 1:250, Neuromics) with 2% blocking serum in PBS. The substrates were rinsed 3 times with PBS for 5mins per wash. They were then incubated for 1hr at RT with appropriate fluorescently labeled secondary-antibody solution (bovine ant-rabbit IgG-TR for NF-L or ALDH1L1, goat anti-mouse IgG-FITC for Nestin, 1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) with 2% blocking serum in PBS. The substrates were then rinsed 3 times with PBS for 5mins per wash and imaged with a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss) and analyzed using ImageJ software.

Cellular morphology and cell interaction with the surfaces was investigated through SEM imaging. Before imaging, unadhered cells were aspirated and the surfaces underwent 2 delicate rinses with PBS. The substrates were then fixed and dehydrated in glass petri dishes. The cells were fixed for 45mins by incubating the substrates in a primary fixative solution (3% v/v glutraldehyde (Sigma), 0.1M sodium cacodylate (Polysciences), and 0.1M sucrose (Sigma)). Prior to dehydration the substrates were incubated in a buffer (primary fixative without glutraldehyde) for 10mins. The surfaces were then dehydrated in consecutive solutions of increasing ethanol concentrations (35%, 50%, 70%, 95%, 100%) for 10mins each. A final dehydration was performed by incubating the substrates in hexamethyldisilazane for 10mins (HMDS, Sigma). The surfaces were stored in a desiccator until imaging. They were coated with a 10nm layer of gold and imaged using SEM at 7kV.

2.7 Statistics

All the material characterization experiments were conducted on at least 3 substrates and at least 3 different locations per substrate (nmin = 9). All the biological experiments were conducted on at least 3 different substrates with at least 3 different cell populations (nmin = 9). All quantitative results were analyzed using ANOVA and statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

The longevity and effectiveness of current neural prostheses are limited in part by the immune response resulting in a layer of glial cells that encapsulate the implants and isolate them from the targeted tissue. The development of an interface for these implants that is capable of preventing gliosis and promoting direct neuronal adhesion could increase the implants lifespan and effectiveness. Different nanotopographical surface modifications have been shown to limit gliosis, promote neuronal adhesion, and even direct neurite outgrowth [22–24]. Nanotopographies such as titania nanotube arrays have demonstrated great potential as interfaces for implantable devices due to their capability of limiting immune response and directing cellular differentiation [31, 32]. In this work, we have investigated the efficacy of different types of titania nanotube arrays as interfaces for neural prostheses.

3.1 Characterization of titania nanotube arrays

SEM was used to characterize the surface morphology of titania nanotube arrays. The results indicate uniform and repeatable nanoarchitectures. NT-H2O arrays were highly ordered, vertically oriented, with adjacent nanotubes, in contrast to the NT-DEG arrays which were composed of distinct, vertically oriented nanotubes that would cluster together forming anemone-like structures (Figure 3(a)). The NT-DEG arrays were significantly longer at approximately 3.72μm compared to the NT-H2O arrays at approximately 1.25μm. The NT-DEG arrays had larger diameters at approximately 125nm compared to the NT-H2O arrays at 96nm, but no significant difference was found. Wall thickness for both arrays was approximately 18 ± 5nm (Figure 3(b)).

Figure 3.

Figure 3(a) Representative SEM images of NT-H2O and NT-DEG arrays indicating the top view (top) and cross-sectional view (bottom).

Figure 3(b) Diameter and length of NT-H2O and NT-DEG arrays masured from SEM images using the ImageJ software. Measurements were taken from at least 3 different substrates at 3 different locations (nmin = 9). Diameter and length of the NT-H2O arrays were significantly lower than that of NT-DEG arrays (* → p < 0.05). Error bars represent standard deviation.

The crystallinity of the nanotube arrays was investigated using GAXRD with the peaks correlated to titanium (JCPDS# 44-1294, ■), anatase (JCPDS# 21-1272, ○), and rutile (JCPDS# 44-1294, ❖) from the International Center for Diffraction Data. The differences in electrolyte, annealing temperature, and nanotube architecture may lead to a difference in crystalline phases. The crystal structure is important as grain restructuring into the stable rutile phase can destroy nanoarchitectures, while the metastable anatase phase can reduce the electron free path length, yielding a more conductive material [30]. The results indicate an increase in anatase and rutile phases on both nanotube arrays as compared to the titanium substrate. However, the NT–DEG arrays have a higher presence of anatase phase than the NT-H2O arrays (Figure 4). The higher presence of anatase phase suggests that the NT-DEG arrays may be more favorable than NT-H2O arrays since the anatase phase is more conductive than the rutile phase.

Figure 4.

Representative high-resolution GAXRD scans of titanium substrates, NT-H2O, and NT-DEG arrays with the different peaks for amorphous titanium (■), anatase phase (○), and rutile phase (❖). The NT-DEG arrays have higher amounts of more conductive anatase phase as compared to titanium substrates and NT-H2O arrays.

The conductance of a material for a neural prosthesis interface is critical as their method of action is to electrically stimulate or record neuronal populations [6, 40]. Hence conductance was measured using a standard 4PP method. The results indicate that both nanotube arrays have comparable conductance to that of silicon semiconductors. Both nanotube array conductances are not significantly different than that of the titanium surface (which has an inherent natural oxide layer present). However, the conductance of the NT-DEG arrays at approximately 480Ω−1 was significantly higher than that of NT–H2O at 78Ω−1, correlating the higher presence of anatase phase in NT-DEG than in NT–H2O (as indicated by GAXRD results) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Conductance of titanium substrates, NT-H2O and NT-DEG arrays measured using a 4PP method. Measurements were taken from at least 3 different substrates at 3 different locations (nmin = 9). The conductance of NT-DEG arrays is significantly higher than that of NT-H2O arrays (* → p < 0.05). Error bars represent standard deviation.

The surface energy and wettability of material surfaces can affect how cells adhere, grow, and differentiate. Hydrophilic surfaces have been shown to promote cellular adhesion and prevent the accumulation of cellular multilayers, while high surfaces energies have been shown to promote cellular differentiation [41, 42]. Contact angle goniometry was performed to investigate the surface wettability, with the surface energy calculated from the measured contact angles [37]. The results indicate that titania nanotube arrays had significantly lower contact angles compared to the titanium substrate. The NT–DEG arrays had lower contact angles than that of NT–H2O arrays (Figure 6). This may be due to the fact that the NT-DEG arrays provide a larger surface area for interaction with water [43]. The lower contact angles of the nanotube arrays resulted in higher surface energies as compared to the titanium substrates. The NT–DEG arrays had the highest surface energy of approximately 71.5mJ/m2 compared to 68.0mJ/m2 of the NT-H2O arrays and 44.8mJ/m2 of titanium (Figure 6). Thus, the more hydrophilic NT-DEG arrays may provide a beneficial interface to promote cell adhesion and subsequent cellular functions.

Figure 6.

Representative images of water droplet on different substrates, respective contact angle values and calculated surface energies of different substrates. Contact angle measurements were taken on at least 3 different substrates at 3 different locations. Statistical symbols are not used in this figure. Titanium substrates have significantly higher contact angles (significantly lower surface energy) as compared to NT-H2O and NT-DEG arrays (p < 0.05).

Localized forces experienced by the cell from the surface affect cellular functionality through mechanotransduction and protein expression, changing cell signaling, and subsequent behavior [22, 44, 45]. Surface topography can greatly affect these localized forces by altering properties such as hardness. Hardness is very important in neurological applications as neural tissue is known to prefer softer materials [46]. The modulus of elasticity and the surface hardness were measured using nanoindentation and the Oliver and Pharr method [47]. The elastic modulus of titanium substrates (approximately 10.3GPa) was significantly higher than that of either of the nanotube arrays (approximately 4.5GPa for the NT-H2O arrays and 4.2GPa for the NT-DEG arrays) (Figure 7(a)). Further, the results indicate that the titanium substrates at 3.0GPa were significantly harder than either of the nanotube arrays with the NT-H2O arrays at approximately 1.0GPa, and NT-DEG having a much lower hardness near 500MPa (Figure 7(b)). This is expected since the nanotube arrays provide less restriction to deformation allowing more space for the structure to “give way” as the force is applied on nanotube arrays. The NT–DEG arrays, having higher spacing between individual nanotubes and longer length are less resistant to deflection, yielding a softer material.

Figure 7.

Figure 7(a) Elastic modulus of titanium substrates, NT-H2O and NT-DEG arrays measured using nanoindentation. Indents were performed on at least 3 different substrates at 3 different locations (nmin = 9). Statistical symbols are not used in this figure. Both NT-H2O and NT-DEG arrays had a significantly lower elastic modulus than that of titanium substrates (p < 0.05). Error bars represent standard deviation.

Figure 7(b) Hardness of titanium substrates, NT-H2O and NT-DEG arrays measured using nanoindentation. Indents were performed on at least 3 different substrates at 3 different locations (nmin = 9). Statistical symbols are not used in this figure. Titanium substrates have significantly higher hardness, followed by NT-H2O and NT-DEG arrays (p < 0.05). Error bars represent standard deviation.

3.2 Protein adsorption on titania nanotube arrays

The surface of a neural prosthesis may readily adsorb proteins that may impact the performance of the implant and its interaction with the surrounding tissue [48–50]. The common blood proteins: albumin and fibrinogen, which may be encountered during prosthesis implantation, have been known to influence the functionality of neural prostheses. Albumin has been implicated in Alzheimer’s disease while fìbrinogen has been shown to increase immunoreactivity [51, 52]. Laminin is a common adhesion protein in neurological tissue and is necessary for neuronal growth [53]. The results indicated statistically similar amounts of albumin and fibrinogen adsorption on all the substrates. However, there was significantly higher laminin adsorption on NT-DEG arrays than on NT-H2O arrays and titanium substrates (Figure 8). The increased laminin adsorption on NT-DEG arrays indicates their potential to increase the adhesion of neurons.

Figure 8.

Adsorption of key proteins encountered during neurological prostheses implantation. Proteins adsorption was done on at least 9 different substrates (nmin = 9). The NT-DEG arrays had a significantly laminin adsorption as compared to NT-H2O arrays and titanium substrates (* → p < 0.05). Error bars represent standard deviation.

3.3 C17.2 adhesion and proliferation on titania nanotube arrays

The C17.2 subclone, generously provided by Dr. Evan Y. Snyder’s group at the Sanford Burnham Medical Research Institute, was used as a model cell line for this study. These cells were isolated from the neonatal mouse cerebellum and underwent v-myc transfection [34]. This cell line has similar developmental potential to that of endogenous neural progenitor stem cells, and with the aid of differentiation cues and supplements can differentiate into all neural cell types without the need for co-culture.

Cell adhesion and proliferation were investigated after 1, 4 and 7 days of culture in growth media using fluorescence microscopy (Figure 9(a)). The results indicate that after 1 day of culture there were similar numbers of cells adhered on all the surfaces. However, the cells have distinct morphologies with large flat cells on titanium substrates and NT-H2O arrays, whereas spindle and pyramidal shaped cells on NT-DEG arrays. After 4 days of culture, there was minimal proliferation on titanium substrates and NT-H2O arrays, with significantly higher proliferation on NT-DEG arrays. Further, the cells on the NT-H2O arrays appeared to have microglia-like morphologies. After 7 days of culture there was notable proliferation on NT-H2O and NT-DEG arrays with cells reaching confluency. Minimal proliferation was seen on titanium substrates. Cell adhesion was quantified by counting the number of DAPI stained nuclei on each fluorescent image (Figure 9(b)). The results indicate higher cell adhesion on both NT-H2O and NT-DEG arrays as compared to the titanium substrates. In order to quantify the cell proliferation, proliferation ratio was calculated by dividing the number of adhered cells after 4 and 7 days by the number of adhered cells after 1 day of culture. The results indicate higher proliferation ratio on NT-DEG arrays than NT-H2O arrays or titanium substrates (Figure 9(c)). These results are expected since the NT-DEG arrays where more hydrophilic than NT-H2O arrays and titanium substrates.

Figure 9.

Figure 9(a) Representative fluorescence microscopy images of C17.2 cells stained with rhodamine phalloidin (red), FITC CMFDA (green), and DAPI (Blue) on titanium substrates, NT-H2O and NT-DEG arrays after 1, 4, and 7 days of culture in growth media. Experiments were replicated on at least 3 different substrates with at least 3 different cell populations (nmin = 9).

Figure 9(b) C17.2 cell density on titanium substrates, NT-H2O and NT-DEG arrays after 1, 4, and 7 days of culture in growth media. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI and counted using ImageJ software. Experiments were replicated on at 3 three different substrates with at least 3 different cell populations and at least 3 different images (nmin = 27). Titanium substrates had significantly lower cell densities than NT-H2O or NT-DEG arrays after each day of culture (p < 0.05). Error bars represent standard deviation.

Figure 9(c) Proliferation ratio calculated from cell densities on titanium substrates, NT-H2O, and NT-DEG arrays after 4 and 7 days of culture.

3.4 Differentiation marker protein expression and cell morphology on titania nanotube arrays

Cell differentiation was investigated after 7 days of culture in differentiation media in order to evaluate the potential of the interfaces to promote and maintain the different neural lineages. The supplements and factors used in the differentiation media provide cues to direct cellular differentiation towards astrocytes and neurons. The N-2 supplement that was added to the media is a commercially available formulation that supports the growth of post-mitotic neurons in the peripheral and central nervous system. GDNF is known to promote the growth, differentiation, and survival of dopaminergic neurons [54]. NGF 7S is known to promote the survival and neurite outgrowth of neurons, as well as proliferation of astrocytes in vitro [55]. After 7 days of culture, immunofluorescence staining was performed in pairs, with either ALDH1L1 or NF-L with nestin. Nestin is a frequently used marker to indicate the presence of neural progenitor cells that may not have undergone differentiation, and ensures they have not become fibroblastic. ALDH1L1 is a highly specific, highly expressed marker for astrocytes as it has many roles in biochemical reactions, especially in cellular growth and division [56]. NF-L is the smallest of the neurofilaments, making up the backbone to which other neurofilaments copolymerize, and is directly correlated to axonal diameter and electrical signal transduction [57, 58].

The results of staining with ALDH1L1/nestin show higher expression of ALDH1L1 on titanium substrates and NT-DEG arrays with minimal expression on NT–H2O arrays (Figure 10(a)). The cells on NT-DEG arrays have multi-polar morphologies similar to that of astrocytes. The cells on the NT–H2O arrays show circular morphologies with some cell-cell interaction via long extensions. The cells on the titanium substrates show flat morphologies with no cellular extensions. Further, many cells on all the substrates expressed nestin, indicating that they are still neural progenitors and have not undergone differentiation.

Figure 10.

Figure 10(a) Representative immunofluorescence images of C17.2 cells after 7 days of culture in differentiation media immunostained with ALDH1L1 (red), nestin (green), and DAPI (blue) for the expression of astrocyte marker, neural precursor marker, and nucleus respectively. Experiments were replicated on at least 3 different substrates with at least 3 different cell populations (nmin = 9).

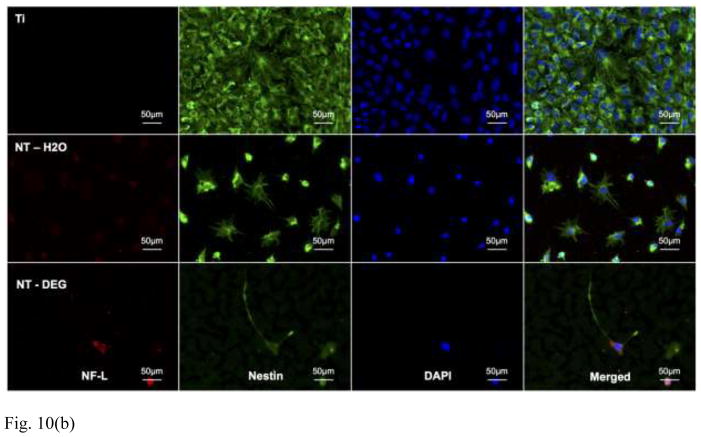

Figure 10(b) Representative immunofluorescence images of C17.2 cells after 7 days of culture in differentiation media, immunostained with NF-L (red), nestin (green), and DAPI (blue) for the expression of neuronal marker, neural precursor marker, and nucleus respectively. Experiments were replicated on at least 3 different substrates with at least 3 different cell populations (nmin = 9).

Figure 10(c) Percentage of TR-labeled ALDH1L1 and NF-L normalized by total number of cells in an image.

The results of staining with NF-L/nestin show increased expression of NF-L on NT-DEG arrays compared to NT–H2O arrays with little to no expression on titanium substrates (Figure 10(b)). The cells on the NT-DEG arrays have neuronal morphologies with longer cellular extensions. However, the cells on the NT–H2O arrays present circular morphologies. The cells on the titanium substrates have flat morphology with limited cellular extension. Further, many cells on all surfaces expressed nestin, indicating that they are still in their neural progenitor stage and have not undergone differentiation.

In order to quantify protein expression, the immunofluorescence images were analyzed using ImageJ software. The surface area covered by TR and was normalized by the number of cells present in that particular image. This gave the relative expressions of ALDH1L1 (Figure 10(a)) and NF-L (Figure 10(b)) for the group of cells that were visualized (Figure 10(c)). The results indicate no significant difference in ALDH1L1 expression between substrates. However, NF-L expression was significantly higher on NT-DEG arrays than NT–H2O arrays and titanium substrates.

To further investigate the cell morphology and the cell-substrate interaction, SEM imaging was used (Figure 11). The results were comparable to the morphologies observed through immunofluorescence microscopy. The cells on the titanium substrates have flat morphologies, whereas the cells on the NT–H2O and NT-DEG arrays have unique morphological features. The cells on the NT–H2O arrays have circular morphologies with some cell-surface interaction. However, the cells on the NT-DEG arrays have a significant level of interaction with the nanotube morphology as seen in the high magnification images.

Figure 11.

Representative SEM images of C17.2 cells on titanium substrates, NT-H2O and NT-DEG arrays after 7 days of culture in differentiation media. Experiments were replicated on at least 3 different substrates with at least 3 different cell populations (nmin = 9). The substrates and cells were coated with a 10nm layer of gold and were imaged a 7keV.

4. Conclusion

Titania nanotube arrays with controllable and repeatable nanotopographies were fabricated by electrochemical anodization of titanium in water and DEG based fluoride-containing electrolytes. Material characterization revealed that the nanotube arrays with water-based electrolyte were highly oriented, densely packed with adjacent nanotubes; whereas the DEG-based electrolyte nanotube arrays were loosely packed with individual nanotubes forming clusters or anemone-like structures. After annealing, the NT-DEG arrays were seen to have an increased presence of the anatase crystal phase, with conductance measurements confirming that NT-DEG arrays were the most conductive. Contact angle goniometry revealed that the nanotube arrays were more hydrophilic than the titanium substrates. Nanoindentation revealed that the NT-DEG arrays were significantly softer than the titanium substrates. While no significant differences were observed in albumin or fibrinogen adsorption among the substrates, there was significantly higher laminin adsorption on the NT–DEG arrays. Fluorescence microscopy images showed higher initial adhesion and subsequent proliferation of C17.2 cells on nanotube arrays. Immunofluorescence microscopy of marker proteins, ALDH1L1 and NF-L, revealed that C17.2 cells were differentiating towards neuronal lineages under the presence of differentiation cues. NF-L expression was significantly higher on NT-DEG arrays as compared to the other substrates. These results indicate that nanotube arrays with similar properties and morphologies to the NT-DEG arrays produced here may provide a favorable interface for neural prostheses by impeding gliosis while promoting direct neuronal interaction. Further studies will be directed toward understanding how these nanoarchitectures influence the mechanisms of cell differentiation and on the long-term efficacy of these nanotube arrays in maintaining the differentiated phenotypes of the cells.

Highlights.

Titania nanotube arrays can be fabricated with to have a loosely or densely packed morphologies.

Titania nanotube arrays support higher C17.2 neural stem cell adhesion and proliferation.

Titania nanotube arrays support higher C17.2 neural stem cell differentiation towards neuronal lineage.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 5-R21-AR057341-02. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pezaris JS, Eskandar EN. Neurosurgical focus. 2009;27:E6. doi: 10.3171/2009.4.FOCUS0986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim HH, Lenarz M, Lenarz T. Trends in amplification. 2009;13:149–180. doi: 10.1177/1084713809348372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson BS, Dorman MF. Hearing research. 2008;242:3–21. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen ED. Journal of neural engineering. 2007;4:R14–31. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/4/2/R02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waldert S, Pistohl T, Braun C, Ball T, Aertsen A, Mehring C. Journal of physiology, Paris. 2009;103:244–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lebedev MA, Nicolelis MA. Trends in neurosciences. 2006;29:536–546. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicolelis MA. Nature. 2001;409:403–407. doi: 10.1038/35053191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dias M, Antunes A. Chest. 2014;145:570A. doi: 10.1378/chest.1825727. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breit S, Wachter T, Schols L, Gasser T, Nagele T, Freudenstein D, Kruger R. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2009;80:235–236. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.145656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger TW, Ahuja A, Courellis SH, Deadwyler SA, Erinjippurath G, Gerhardt GA, Gholmieh G, Granacki JJ, Hampson R, Hsaio MC, LaCoss J, Marmarelis VZ, Nasiatka P, Srinivasan V, Song D, Tanguay AR, Wills J. IEEE engineering in medicine and biology magazine : the quarterly magazine of the Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society. 2005;24:30–44. doi: 10.1109/memb.2005.1511498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorsey ER, Constantinescu R, Thompson JP, Biglan KM, Holloway RG, Kieburtz K, Marshall FJ, Ravina BM, Schifitto G, Siderowf A, Tanner CM. Neurology. 2007;68:384–386. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000247740.47667.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jankovic J. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2008;79:368–376. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.131045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breit S, Schulz JB, Benabid AL. Cell and tissue research. 2004;318:275–288. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0936-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pahwa R, Wilkinson S, Smith D, Lyons K, Miyawaki E, Koller WC. Neurology. 1997;49:249–253. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Widge A, Jeffries-El M, Lagenaur CF, Weedn VW, Matsuoka Y. Ieee Int Conf Robot. 2004:5058–5063. doi: 10.1109/Robot.2004.1302519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szarowski DH, Andersen MD, Retterer S, Spence AJ, Isaacson M, Craighead HG, Turner JN, Shain W. Brain research. 2003;983:23–35. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bovolenta P, Wandosell F, Nieto-Sampedro M. Prog Brain Res. 1992;94:367–379. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61765-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landis DM. Annual review of neuroscience. 1994;17:133–151. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.001025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norton WT, Aquino DA, Hozumi I, Chiu FC, Brosnan CF. Neurochemical research. 1992;17:877–885. doi: 10.1007/BF00993263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green RA, Lovell NH, Wallace GG, Poole-Warren LA. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3393–3399. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Mingxian, Shen Yan, Ao Peng, Dai Libing, Liu Zhihe, Zhou Changren. RSC Advances. 2014;4:23540–23553. doi: 10.1039/C4RA02189D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva GA. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2006;7:65–74. doi: 10.1038/nrn1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jang KJ, Kim MS, Feltrin D, Jeon NL, Suh KY, Pertz O. PloS one. 2010;5:e15966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fozdar DY, Lee JY, Schmidt CE, Chen S. Biofabrication. 2010;2:035005. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/2/3/035005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu M, Piao LY, Wang WJ. Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology. 2010;10:7469–7472. doi: 10.1166/Jnn.2010.2870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mali SS, Kim H, Shim CS, Patil PS, Kim JH, Hong CK. Sci Rep-Uk. 2013;3:Artn 3004. doi: 10.1038/Srep03004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X, Li Z, Shi J, Yu Y. Chemical reviews. 2014 doi: 10.1021/cr400633s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mor GK, Varghese OK, Paulose M, Shankar K, Grimes CA. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells. 2006;90:2011–2075. doi: 10.1016/j.solmat.2006.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoriya S, Grimes CA. Journal of Materials Chemistry. 2011;21:102–108. doi: 10.1039/C0jm02421j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varghese OK, Gong D, Paulose M, Grimes CA, Dickey EC. Journal of Materials Research. 2003;18:156–165. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Popat KC, Leoni L, Grimes CA, Desai TA. Biomaterials. 2007;28:3188–3197. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith BS, Capellato P, Kelley S, Gonzalez-Juarrero M, Popat KC. Biomaterials Science. 2013;1:322. doi: 10.1039/c2bm00079b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu P, Jones LL, Snyder EY, Tuszynski MH. Experimental Neurology. 2003;181:115–129. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Snyder EY, Deitcher DL, Walsh C, Arnold-Aldea S, Hartwieg EA, Cepko CL. Cell. 1992;68:33–51. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90204-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruan CM, Paulose M, Varghese OK, Mor GK, Grimes CA. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:15754–15759. doi: 10.1021/Jp052736u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoriya S, Grimes CA. Langmuir : the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids. 2010;26:417–420. doi: 10.1021/La9020146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu X, Lim JY, Donahue HJ, Dhurjati R, Mastro AM, Vogler EA. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4535–4550. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pharr GM, Oliver WC, Brotzen FR. Journal of Materials Research. 1992;7:613–617. doi: 10.1557/Jmr.1992.0613. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lundqvist J, El Andaloussi-Lilja J, Svensson C, Gustafsson Dorfh H, Forsby A. Toxicology in vitro : an international journal published in association with BIBRA. 2013;27:1565–1569. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2012.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montgomery EB., Jr Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine. 1999;66:9–11. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.66.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ranella A, Barberoglou M, Bakogianni S, Fotakis C, Stratakis E. Acta biomaterialia. 2010;6:2711–2720. doi: 10.1016/J.Actbio.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao G, Schwartz Z, Wieland M, Rupp F, Geis-Gerstorfer J, Cochran DL, Boyan BD. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2005;74A:49–58. doi: 10.1002/Jbm.A.30320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wenzel RN. Ind Eng Chem. 1936;28:988–994. doi: 10.1021/Ie50320a024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Biggs MJ, Richards RG, Dalby MJ. Nanomedicine : nanotechnology, biology, and medicine. 2010;6:619–633. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stevens MM, George JH. Science. 2005;310:1135–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.1106587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Discher DE, Janmey P, Wang YL. Science. 2005;310:1139–1143. doi: 10.1126/Science.1116995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oliver WC, Pharr GM. Journal of Materials Research. 2004;19:3–20. doi: 10.1557/Jmr.2004.0002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gupta AK, Gupta M. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3995–4021. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Selvakumaran J, Keddie JL, Ewins DJ, Hughes MP. Journal of materials science Materials in medicine. 2008;19:143–151. doi: 10.1007/s10856-007-3110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams DF, Askill IN, Smith R. Journal of biomedical materials research. 1985;19:313–320. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820190312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahn SM, Byun K, Cho K, Kim JY, Yoo JS, Kim D, Paek SH, Kim SU, Simpson RJ, Lee B. PloS one. 2008;3:e2829. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schachtrup C, Ryu JK, Helmrick MJ, Vagena E, Galanakis DK, Degen JL, Margolis RU, Akassoglou K. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:5843–5854. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0137-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liesi P, Dahl D, Vaheri A. Journal of neuroscience research. 1984;11:241–251. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490110304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Erickson JT, Brosenitsch TA, Katz DM. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2001;21:581–589. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00581.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shao N, Wang H, Zhou T, Liu C. Brain research. 1993;609:338–340. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90893-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Giamblanco N, Martines E, Marletta G. Langmuir : the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids. 2013;29:8335–8342. doi: 10.1021/la304644z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuhle J, Plattner K, Bestwick JP, Lindberg RL, Ramagopalan SV, Norgren N, Nissim A, Malaspina A, Leppert D, Giovannoni G, Kappos L. Multiple sclerosis. 2013;19:1597–1603. doi: 10.1177/1352458513482374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alberts B. Molecular biology of the cell. 4. Garland Science; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]