Abstract

Next to the protein-based machineries composed of small G-proteins, coat complexes, SNAREs and tethering factors, the lipid-based machineries are emerging as important players in membrane trafficking. As a component of these machineries, lipid transfer proteins have recently attracted the attention of cell biologists for their involvement in trafficking along different segments of the secretory pathway. Among these, the four-phosphate adaptor protein 2 (FAPP2) was discovered as a protein that localizes dynamically with the trans-Golgi network and regulates the transport of proteins from the Golgi complex to the cell surface. Later studies have highlighted a role for FAPP2 as lipid transfer protein involved in glycosphingolipid metabolism at the Golgi complex. Here we discuss the available evidence on the function of FAPP2 in both membrane trafficking and lipid metabolism and propose a mechanism of action of FAPP2 that integrates its activities in membrane trafficking and in lipid transfer. This article is part of a Special Issue entitled Lipids and Vesicular Transport.

Keywords: Lipid transfer protein, FAPP2, Golgi complex, Glycosphingolipid, Transport carrier

Highlights

► FAPP2 contains a PtdIns4P (and ARF1) binding PH domain and a GLTP (Glycolipid Transfer Protein) domain. ► The FAPP2-PH domain targets the protein to the trans-Golgi network and has membrane bending activity. ► Via the GLTP domain FAPP2 transfers glucosylceramide and fosters complex glycolipid synthesis at the Golgi complex. ► FAPP2 controls TGN-to-plasma membrane vesicular trafficking by assisting the formation of post-Golgi carriers. ► The lipid-transfer activity of FAPP2 is required for its role in membrane trafficking.

1. Introduction

There is intense exchange of lipid and proteins between organelles of the endomembrane system that occurs mainly by vesicular transport [1]. In many cases the molecular machineries responsible for the distinct vesicular trafficking steps have been described in great detail. These include small G-proteins [2], coat complexes [3], tethering factors [4], and fusogenic SNAREs [5], but also a class of proteins that are able to exchange lipids between membranes by the transfer of specific monomeric lipid species: the lipid transfer proteins (LTPs) [6]. However, though the involvement of different LTPs in several trafficking events has been shown, their mechanism of action in membrane trafficking remains often undefined and appears to be far more complex than would be predicted simply by their lipid transfer activities [6]. A clear example of a LTP with a role in membrane trafficking is the four-phosphate adaptor protein 2 (FAPP2).

The first FAPP protein to be identified in a screen for pleckstrin-homology (PH) domain-containing proteins was the product of the gene PLEKHA3. This protein was named four-phosphate adaptor protein 1 (FAPP1), because its PH domain can bind selectively phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate (PtdIns4P) [7]. Subsequently, FAPP2 was identified as a protein with a PH domain similar to that of FAPP1 [8] but with an additional globular domain at its carboxy terminus. This domain of FAPP2 was initially defined as a glycolipid-transfer protein homology (GLTPH) domain due to sequence similarity with the glycolipid-transfer protein (GLTP), a protein that mediates the inter-membrane transfer of glycosphingolipids (GSLs) in vitro [9]. Later, FAPP2 was shown to bind and transfer specifically glucosylceramide (GlcCer) [10].

FAPPs were found to associate dynamically with the trans-Golgi network (TGN) where they specifically decorate nascent carriers directed to the plasma membrane [8]. This peculiar distribution stimulated the study of the role of FAPPs in membrane trafficking out of the Golgi. It was shown subsequently that silencing FAPP2 inhibits membrane transport from the TGN to the plasma membrane both in non-polarized and polarized epithelial cells where it impairs specifically the transport of cargoes destined for the apical plasma membrane [8,11,12].

Later, the GlcCer transfer activity associated with FAPP2 has been shown to control the subcellular distribution of the common precursor of GSLs, GlcCer and to foster the synthesis of GSLs at the Golgi complex [10].

It has been hypothesized that the metabolic and trafficking functions associated with FAPP2 are related [10], but the meaning of such a relationship is not yet completely clear.

Herein we provide a description of the molecular organisation, activities, and cellular functions of FAPP2 and propose a mechanism of action of FAPP2 that integrates its activities in membrane trafficking and in lipid transfer.

2. Molecular organization of FAPP2

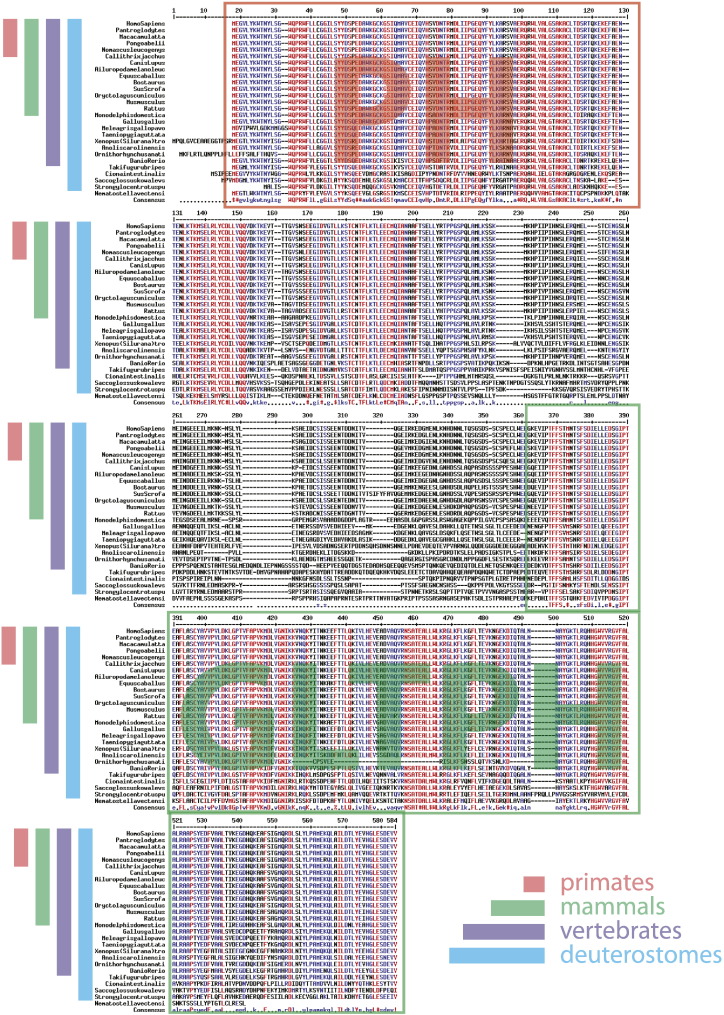

Human FAPP2 is a 519 amino acid protein encoded by the gene PLEKHA8 located on chromosome 7. Homologs of the PLEKHA8 gene are found in vertebrates and deuterostomes, while they are virtually absent in lower metazoans, plants, fungi and lower eukaryotes [6]. Protein sequence alignment of FAPP2 homologs from all of the species where the gene has been sequenced shows that the FAPP2 protein has two strongly conserved regions (the most N-terminal 180 and the most C-terminal 200 amino acids, Fig. 1) including the PH and GLTPH domains. By contrast, the central region of FAPP2 (residues 180–320) is weakly conserved and may be less strictly structured and thus more flexible. Both the FAPP2-like PH and GLTPH folds are evolutionarily older than the FAPP2 gene itself and are found in lower eukaryotes as separate entities (Fig. 2). This last observation points to the possibility that the PH and GLTPH folds are self-sufficient to sustain some independent biological processes while their presence in the same molecule might have been selected to assist some emergent function of vertebrate systems. Interestingly the appearance of FAPP2 in evolution coincides with a leap in complexity in the glycolipid system going from a linear “unbranched” metabolism to a branched one, thus raising the possibility that FAPP2 might be involved in controlling this level of complexity.

Fig. 1.

Protein sequence alignment of the FAPP2 protein in different organisms. Strongly and moderately conserved residues are shown in red and blue, respectively. Protein regions corresponding to the PH and GLTPH domains are indicated.

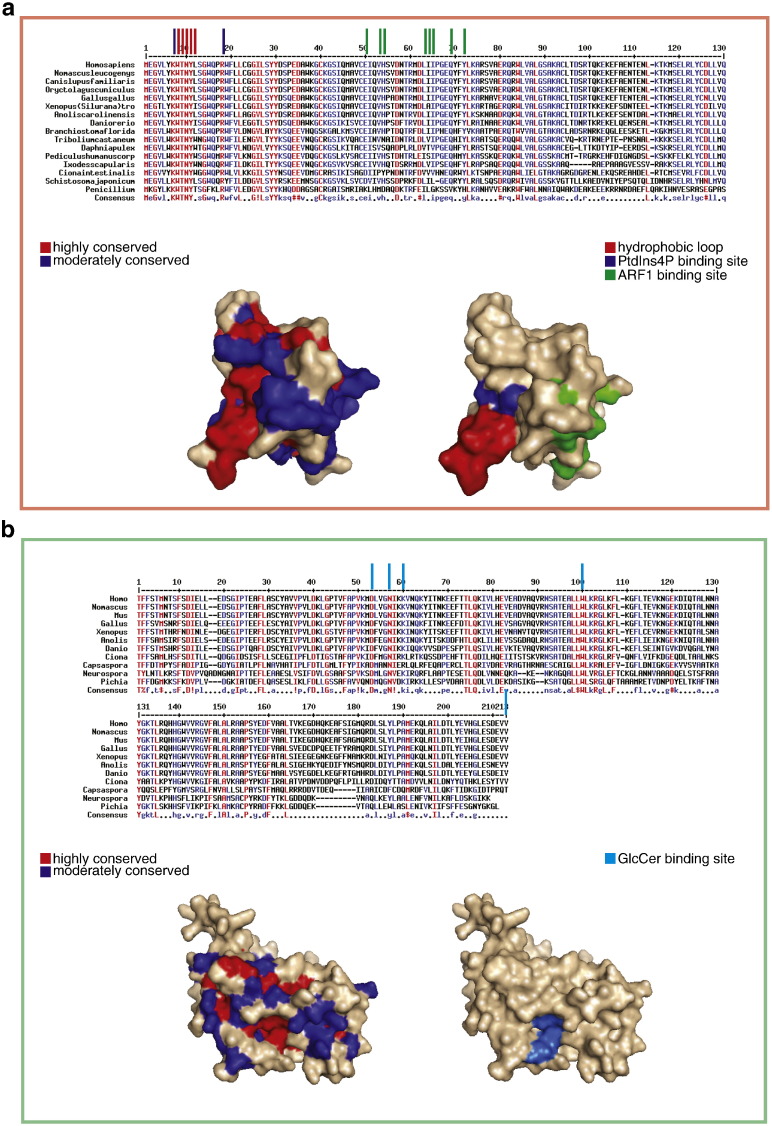

Fig. 2.

The lipid binding domains of FAPP2: the PH domain and the GLTPH domain. a) The FAPP2 PH domain. Upper panel: sequence alignment of the FAPP2 PH domain in different species. Bars on top of the sequence indicate residues involved in PtdIns4P binding (blue bars), ARF1 binding (green bars) or in the formation of the hydrophobic hairpin loop (red bars). Lower panel: homology modelling of the FAPP2-PH structure derived from the FAPP1-PH crystal structure (PDB ID: 3RCP) using Swiss-model [32] highlighting, on the left, the conservation of the different regions (strongly and moderately conserved regions coloured in red and blue, respectively) and on the right the regions involved in PtdIns4P binding (blue), ARF1 binding (green) or in the formation of the hydrophobic hairpin loop (red). b) The FAPP2 GLTPH domain. Upper panel: sequence alignment of the FAPP2 GLTPH domain in different species. Bars on top of the sequence indicate residues involved in glycolipid binding. Lower panel: homology modelling of the FAPP2-GLTPH structure derived from the GLTP crystal structure (PDB ID: 1SWX) using Swiss-model [32], highlighting, on the left, the conservation of the different regions (strongly and moderately conserved regions coloured in red and blue, respectively) and, on the right, the residues involved in glycolipid binding (cyan).

2.1. The PH domain

The FAPP2 PH domain belongs to a family of PH domains that share high sequence homology and a preferential interaction with PtdIns4P. Indeed, FAPP2-PH, as well as the PH domain of FAPP1, OSBP1, ORP9, and CERT, drives the localisation of the full length-protein(s) to the TGN by recognizing and binding PtdIns4P, which is enriched on the cytoplasmic membrane leaflet of this organelle [13]. FAPP1-PH and OSBP1-PH have also been demonstrated to bind ARF1 and thus to restrict their localisation to specific membranes through the coincident detection of both Arf1 and PtdIns4P [8]. The PtdIns4P and ARF1 binding sites have been characterized in FAPP1-PH [14]. In addition, the crystal structure of FAPP1-PH shows that it folds into a seven-stranded β-barrel capped by an α-helix at one edge, whereas the opposite edge is flanked by three loops and the β4 and β7 strands that form a lipid-binding pocket within the β-barrel [14]. The solution of the FAPP1-PH structure has also led to the identification of a hydrophobic hairpin protrusion that is able to penetrate the membrane leaflet and, by virtue of this, to induce membrane deformation [15]. All of the residues relevant for the binding of PtdIns4P and ARF1 in FAPP1-PH are conserved in FAPP2-PH, making it likely that FAPP2-PH can also localize to the TGN via the coincident detection of ARF1 and PtdIns4P. Furthermore, the residues that make up the hydrophobic protrusion in FAPP1-PH [15] are also conserved in FAPP2-PH (Fig. 2a). Consideration of the similarity in the FAPP2 PH domain of FAPP2 homologs from different species shows the strongest conservation in residues responsible for PtdIns4P binding and in those lining the hydrophobic hairpin protrusion, while those responsible for ARF1 binding are slightly less conserved (Fig. 2a). Therefore, the FAPP2 PH domain seems to contain the information needed to localize to the TGN by interacting with PtdIns4P and possibly ARF1, and to promote local membrane deformation required for the budding of post-Golgi transport carriers (see below).

2.2. The GLTPH domain

The C-terminal 200 amino acids of FAPP2 show significant similarity to the GLTP protein [10] that facilitates the selective transfer of glycolipids between lipid vesicles in vitro. Although the overall homology between the FAPP2 GLTPH domain and GLTP is limited, the residues important for GLTP glycolipid transfer activity are all conserved in FAPP2-GLTPH [10]. The overall folding of GLTP and FAPP2-GLTPH are also likely to be very similar as indicated by homology modelling of FAPP2-GLTPH on the crystal structure template of GLTP [10]. In addition, FAPP2 has a glycolipid transfer activity, which is abolished by a mutation in the glycolipid binding site that can be inferred from the homology with GLTP [10]. The GLTP protein has been extensively characterized also in terms of its interaction with membranes [16]. Tryptophan 142 (W142) in GLTP has been proposed to be part of the membrane interacting surface and would exhibit shallow intrusion into the membrane bilayer [16]. GLTP W142 is conserved in FAPP2-GLTPH (Fig. 2b), which possibly retains the same membrane interaction properties and orientation as GLTP. GLTP has also been demonstrated to interact with the ER resident protein VAP-A in vitro through a FFAT-like motif in the GLTP sequence [17], which is, however, not conserved in FAPP2-GLTPH. Finally, the GLTPH domain of FAPP2 shows a remarkable conservation of residues lining the glycolipid binding site (Fig. 2b) while the external surface is less conserved, suggesting that glycolipid transfer/binding is a conserved feature in the FAPP2 GLTPH domain while regulatory layers and interactors might have changed during evolution.

2.3. FAPP2 supramolecular organization

Information on the overall structure of FAPP2 and on the coordination of its PH and GLTPH domains is scarce. Nevertheless, the combined use of analytical ultracentrifugation and small-angle x-ray scattering techniques has provided some insights about the assembly of the protein and its low-resolution envelope structure [18]. These studies demonstrate that recombinant FAPP2 exists as a dimer in solution that is organized as an extended curved protein assembly with a maximal size of 30 nm. Based on rigid body modelling applied to the small-angle x-ray scattering-derived low-resolution envelope structure, the FAPP2-PH domains would occupy the central region of the extended structure while the GLTPH domains would be positioned at the wings (Fig. 3b inset). The actual existence of FAPP2 dimers in cells as well as the identification of the dimerization surface remains to be demonstrated.

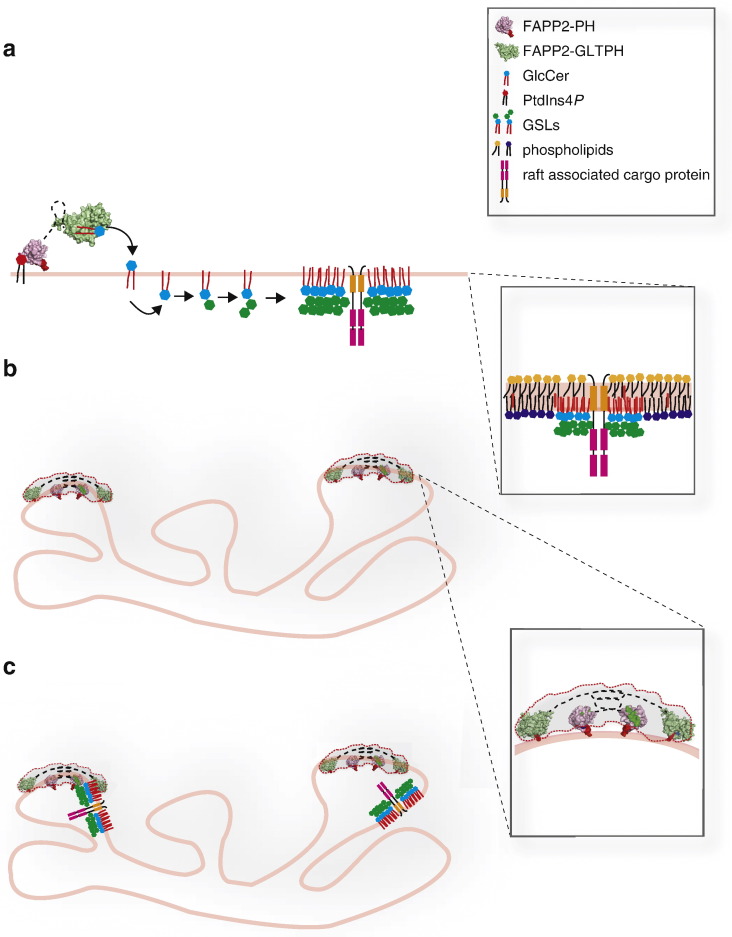

Fig. 3.

The roles of FAPP2 in the biogenesis of transport carriers at the TGN. a) FAPP2 might contribute to sort specific cargoes within specific membrane microdomains by fostering the synthesis of GSLs that segregate from other membrane lipids thus forming sorting platforms. b) FAPP2 is involved in the budding of post-Golgi carrier by inducing membrane bending through the insertion of the hydrophobic loop (located in its PH domain) into the lipid bilayer. c) The combined sorting and budding activities of FAPP2 can coordinate the formation of specific post-Golgi carriers (most probably apically directed) with specific lipid and protein composition.

3. FAPP2 activities

The described structural organization of FAPP2 parallels the different activities that have been associated with the protein.

3.1. Membrane tubulation

The first indication that FAPPs might have membrane deformation properties came from the observation that the overexpression of FAPP1-PH in cells induces the formation of cargo protein-containing long tubules emanating out of the TGN [8]. Subsequently an in vitro correlate of this activity has been reported by Cao et al. showing that the addition of recombinant FAPP2 [18] or FAPP1-PH [15] to artificial membrane sheets is sufficient to induce their tubulation. This tubulation is accomplished by multiple concerted interactions with the membrane. Non-specific electrostatic attraction allows the protein to diffuse over the lipid bilayer until PtdIns4P is recognized. The interaction with PtdIns4P concentrates oriented FAPP molecules at discrete sites (enriched in PtdIns4P), compressing the membrane via the insertion of the wedge-shaped hydrophobic hairpin, and thus favoring local positive curvature. The bilayer buds spontaneously when it reaches a critical protein concentration, yielding a tubule that grows rapidly [15]. As mentioned above, the residues of the hydrophobic protrusion in FAPP1-PH are conserved in FAPP2 (Fig. 2a) and mutations in these residues affect the ability of FAPP2 to tubulate membrane sheets in vitro [18]. This membrane deformation property of FAPP-PH is highly likely to be central for the activity of FAPP2 in controlling membrane trafficking, however it does not seem to be sufficient. In fact, the over-expression of FAPP1-PH in cells, though stimulating tubule formation at the TGN, inhibits cargo transport [8], as the FAPP1-PH-induced tubules are incompetent for fission and for fusion with the plasma membrane [8]. As this inhibitory effect is not seen when the full-length FAPP2 protein is over-expressed, it is possible that additional functions associated with other domains of the protein are required for the completion of the carrier formation process.

3.2. Glycolipid transfer

The presence of a GLTPH domain in the C-terminal portion of FAPP2 stimulated the search for a possible glycolipid transfer activity [10]. The only glycolipid that would be accessible for a cytosolic protein, such as FAPP2, is GlcCer as it is synthesized on the cytosolic leaflet of early Golgi compartments. Therefore, the ability of FAPP2 to transfer GlcCer was tested in vitro [10]. Importantly, FAPP2 was found to be able to specifically transfer GlcCer (but not ceramide or sphingomyelin) from donor to acceptor liposomes [10], in a reaction stimulated by the presence of PtdIns4P and ARF1 in the acceptor liposomes. In addition, when recombinant FAPP2 loaded with a fluorescent homolog of GlcCer was added to permeabilized cells it was found to deliver the fluorescent lipid to the Golgi area [10]. Finally, support for FAPP2 having a GlcCer transfer activity in vivo came from the observation that silencing of FAPP2 changed the intra-Golgi distribution of GlcCer, with a loss of GlcGer at the TGN and its accumulation at the cis pole of the Golgi complex [10]. Altogether, these different lines of evidence demonstrate that FAPP2 is a genuine GlcCer transfer protein in vitro and, possibly, in vivo.

4. FAPP2 cellular functions

4.1. FAPP2 localization

Since its discovery, FAPP2 was recognized as a protein peripherally associated with Golgi membranes [8]. Its localisation was found to be promptly abrogated by drugs impinging either on PtdIns4P synthesis or on ARF cycling and to depend on its PH domain [8]. The FAPP PH domain was shown to be sufficient to recapitulate the localization of the full-length protein and to compete with the full-length protein for Golgi localization [8]. In the same study FAPP1-PH was found to interact directly with the GTP-bound form of ARF1 and to counteract the GTPase activating function of ARF GAP1, probably by competing for the same binding sites on the ARF1 molecule. Mutations in the PtdIns4P binding site of FAPP-PH, which abrogate the binding to PtdIns4P, also abrogate its localisation to the Golgi complex, while the same mutation in a FAPP-PH tandem protein results in a repositioning of the protein from the TGN to the core Golgi region [8]. This last observation led to the conclusion that the coincident detection of ARF and PtdIns4P by FAPP-PH drives the localization of FAPP proteins to the Golgi, with PtdIns4P-binding specifying the TGN sub-compartment [8]. Interestingly, FAPP-PH exogenously expressed in organisms that do not have a genuine FAPP gene (e.g. plants and yeasts) [19,20] also localizes to the Golgi complex suggesting that ARF and PtdIns4P represent a conserved regional code for the recruitment of cytosolic factors to the Golgi region. More recently, the molecular basis of FAPP1-PH binding to ARF and PtdIns4P has been elucidated in detail leading to the concept that both ligands can be bound simultaneously and independently to determine its multivalent anchoring to TGN membranes [14].

4.2. FAPP2 controls TGN to plasma membrane trafficking

The role of FAPPs in membrane trafficking has been studied both in non-polarized fibroblast-like and polarized epithelial cells [8,11,12]. Silencing of both FAPP1 and FAPP2 expression in non-polarized Cos7 cells inhibited the transport of the t045-VSV-G cargo reporter and glycosaminoglycans from the TGN to the plasma membrane while it did not inhibit the transport of t045-VSV-G cargo from the ER to the TGN [8]. In addition, displacing FAPPs by treatment with the PI4K inhibitor phenylarsine oxide (PAO) or catalytically inactive PI(4)KIIIβ phenocopied the defects in membrane trafficking caused by FAPP KD. When the silencing effects of FAPP1 and FAPP2 knock down (KD) were addressed separately on TGN-to-plasma membrane trafficking both in HeLa and Cos7 cells, FAPP2 was found to be the only FAPP involved in this trafficking step [11]. The role of FAPPs in membrane trafficking out of the Golgi has been further elucidated by Vieira et al. [11] in polarized MDCK cells where the knock down of FAPP2 was found to selectively impair the transport of raft-associated apical cargoes, such as a glycosylated glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored-GFP reporter and hemagglutinin. In agreement with these results it has been well documented [21–23] that GlcCer and its derivatives after being synthesized are delivered preferentially to apical plasma membrane in polarized cells. Although a specific role for FAPP2 in this process has not been formally addressed so far, the negative impact of FAPP2 silencing on the outgrowth of the primary cilium, which grows out of the apical plasma membrane, has been established in MDCK cells [24]. Here, FAPP2-KD resulted also in a change in the composition/distribution of the plasma membrane lipids, with glycolipids, normally residing only at the apical PM, appearing in both apical and basolateral domains of FAPP2-KD cells. These results suggest that FAPP2 is involved in transport of raft lipids and associated proteins to the apical membranes and that the impaired ciliogenesis in FAPP2-KD cells might arise from disrupted raft lipid delivery to the correct cellular location [24].

It is important to note that the requirement for FAPP2 does not appear to be shared by all apical cargoes exiting the TGN, as Yui et al. [12] have demonstrated that constitutive transport of apical cargoes such as the Na-Cl cotransporter and the transient receptor potential vanilloid-4 is not affected in FAPP2-depleted cells. However FAPP2 was found to be required for the apical accumulation of aquaporin-2 (AQP2) triggered by treatments that elevate intracellular cAMP levels [12].

4.3. FAPP2 controls GSL synthesis

The discovery of a GlcCer transfer activity associated with FAPP2 has stimulated the study of the role of FAPP2 in GSL synthesis. GlcCer is, indeed, the common precursor of complex GSLs, the vast majority of which is synthesized on the lumen of the Golgi apparatus. In two independent studies [10,25] FAPP2 was discovered to foster complex GSL synthesis. Two distinct models for the role of FAPP2 in GSL synthesis have been put forward. One model proposes that FAPP2 operates a net transfer of GlcCer from the cis-Golgi to the TGN where, upon translocation into the lumen (through a yet poorly defined GlcCer transporter), GlcCer undergoes further glycosylation to more complex GSLs [10]. The second model proposes that FAPP2 retrogradely transfers GlcCer from the Golgi to the ER - where, due to the nature of ER membranes, GlcCer would efficiently translocate into the lumen- and would be subsequently transported anterogradely again to the Golgi by vesicular trafficking and converted here into complex GSLs [25]. Further studies are needed to elucidate whether FAPP2 fosters the synthesis of LacCer and of its downstream metabolic products by promoting the anterograde or the retrograde transfer of GlcCer.

5. The integrated FAPP2 function

While a large body of evidence links membrane trafficking to sphingolipid metabolism [26], a clear causal connection between the GlcCer transfer activity of FAPP2 and its role in the biogenesis of post-Golgi carriers at the TGN cannot be drawn at the moment.

The relevance of the lipid transfer activity of FAPP2 in membrane trafficking has been investigated by analyzing the effects of expressing siRNA-resistant forms of wild-type FAPP2 and the GlcCer-transfer-dead form of FAPP2 (W407A) on the impaired TGN-to-plasma membrane transport induced by FAPP2 silencing. While expressing siRNA-resistant wild-type FAPP2 completely rescued TGN-to-plasma membrane transport, only a very limited recovery was seen in cells expressing FAPP2 (W407A) [10]. In addition, it has been reported the homolog of FAPP2 lacking the GLTPH domain (i.e. FAPP1) is not able to substitute for FAPP2 in its membrane trafficking function [10,11]. These data imply that the GlcCer transfer activity associated with FAPP2 is required for efficient TGN-to-plasma membrane transport.

A further indication that the GlcCer transfer activity of FAPP2 is relevant for its role in membrane trafficking at the TGN comes from the observation that some of the phenotypes induced by FAPP2 silencing are mimicked by the depletion of the first enzyme involved in GSL synthesis, namely glucosylceramide synthase (GCS) [10]. These include the defect in TGN-to-plasma membrane transport and the reduction of TGN tubular profiles (accompanied by the increase in the number of cisternae per Golgi stack) [10].

The above lines of evidence support the notion that either GlcCer synthesis/transport and/or the synthesis of complex GSL play a role in the functional organization of TGN membranes in mammals. In line with these possibilities recent studies have linked GlcCer specifically to the regulation of membrane trafficking, polarity establishment, and TGN homeostasis [27,28].

In this context, FAPP2, via its GlcCer transfer activity, can control membrane trafficking at the TGN by intervening at different steps during transport carrier biogenesis. These steps include cargo selection (sorting), membrane bending (budding), and membrane scission (fission) [29] and FAPP2 has the potential to participate in each of these events and possibly to coordinate them.

Firstly, by fostering GSL synthesis, FAPP2 might contribute to cargo sorting at the TGN as it can couple the formation of specific post-Golgi carriers with the control of their lipid composition [10]. GSLs have, indeed, been proposed to form membrane domains able to “attract” specific proteins and thus to play a role in protein sorting along the biosynthetic pathway [30] (Fig. 3a).

Secondly, through the membrane bending property of its PH domain [15] FAPP2 may act as a key player in mediating the budding/elongation of the transport carrier emerging from the TGN (Fig. 3b).

Finally, FAPP2 might also play a role in the fission step, via the localized transfer (and/or its local metabolism) of GlcCer to the budding carrier at the TGN. Indeed, GlcCer and GSLs have distinctive biophysical properties by which they tend to partition into liquid ordered or gel domains in model membranes [26]. It has been proposed that phase separation in elongating membrane tubules contributes to membrane fission by inducing tension at the domain interfaces [31]. In this respect, both GlcCer (on the cytosolic leaflet) and GSLs (on the luminal leaflet) of growing post-Golgi carrier precursors might play a permissive role in carrier fission.

Thus, through the combination of its control of GSL synthesis and membrane deformation properties FAPP2 might integrate the processes of carrier formation and cargo sorting (Fig. 3c) possibly contributing also to the final fission step.

Although the above hypothesis of an integrated mode of action of the PH and the GLTP domains of FAPP2 in the budding and fission step of post-Golgi carrier formation awaits further testing, the evolutionary “recent” combination of these two lipid binding domains in FAPP2, as compared to their existence as separate modules in earlier organisms, would suggest that FAPP2 represents an advanced (and possibly specialized) solution to coordinate the elementary processes mediating carrier biogenesis at the TGN.

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Wilson for editorial assistance. MADM acknowledges the support of Telethon [grant numbers GSP08002 and GGP06166] and AIRC [AIRC, grant IG 8623]. GDA acknowledges the support of AIRC [AIRC, MFAG 10585]. LRR is a recipient of a Fellowship from AIRC.

Footnotes

This article is part of a Special Issue entitled Lipids and Vesicular Transport.

References

- 1.Rothman J.E. Mechanisms of intracellular protein transport. Nature. 1994;372:55–63. doi: 10.1038/372055a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Segev N. Coordination of intracellular transport steps by GTPases. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2010;22:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Field M.C., Sali A., Rout M.P. Evolution: On a bender — BARs, ESCRTs, COPs, and finally getting your coat. J. Cell Biol. 2011;193:963–972. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waters M.G., Pfeffer S.R. Membrane tethering in intracellular transport. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1999;11:453–459. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)80065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malsam J., Kreye S., Sollner T.H. Membrane fusion: SNAREs and regulation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65:2814–2832. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8352-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Angelo G., Vicinanza M., De Matteis M.A. Lipid-transfer proteins in biosynthetic pathways. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2008;20:360–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dowler S., Currie R.A., Campbell D.G., Deak M., Kular G., Downes C.P., Alessi D.R. Identification of pleckstrin-homology-domain-containing proteins with novel phosphoinositide-binding specificities. Biochem. J. 2000;351:19–31. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Godi A., Di Campli A., Konstantakopoulos A., Di Tullio G., Alessi D.R., Kular G.S., Daniele T., Marra P., Lucocq J.M., De Matteis M.A. FAPPs control Golgi-to-cell-surface membrane traffic by binding to ARF and PtdIns(4)P. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:393–404. doi: 10.1038/ncb1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao C.S., Lin X., Pike H.M., Molotkovsky J.G., Brown R.E. Glycolipid transfer protein mediated transfer of glycosphingolipids between membranes: a model for action based on kinetic and thermodynamic analyses. Biochemistry. 2004;43:13805–13815. doi: 10.1021/bi0492197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Angelo G., Polishchuk E., Di Tullio G., Santoro M., Di Campli A., Godi A., West G., Bielawski J., Chuang C.C., van der Spoel A.C., Platt F.M., Hannun Y.A., Polishchuk R., Mattjus P., De Matteis M.A. Glycosphingolipid synthesis requires FAPP2 transfer of glucosylceramide. Nature. 2007;449:62–67. doi: 10.1038/nature06097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vieira O.V., Verkade P., Manninen A., Simons K. FAPP2 is involved in the transport of apical cargo in polarized MDCK cells. J. Cell Biol. 2005;170:521–526. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yui N., Okutsu R., Sohara E., Rai T., Ohta A., Noda Y., Sasaki S., Uchida S. FAPP2 is required for aquaporin-2 apical sorting at trans-Golgi network in polarized MDCK cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C1389–C1396. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00098.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Angelo G., Vicinanza M., Di Campli A., De Matteis M.A. The multiple roles of PtdIns(4)P — not just the precursor of PtdIns(4,5)P2. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:1955–1963. doi: 10.1242/jcs.023630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He J., Scott J.L., Heroux A., Roy S., Lenoir M., Overduin M., Stahelin R.V., Kutateladze T.G. Molecular basis of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate and ARF1 GTPase recognition by the FAPP1 pleckstrin homology (PH) domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:18650–18657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.233015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lenoir M., Coskun U., Grzybek M., Cao X., Buschhorn S.B., James J., Simons K., Overduin M. Structural basis of wedging the Golgi membrane by FAPP pleckstrin homology domains. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:279–284. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamlekar R.K., Gao Y., Kenoth R., Molotkovsky J.G., Prendergast F.G., Malinina L., Patel D.J., Wessels W.S., Venyaminov S.Y., Brown R.E. Human GLTP: Three distinct functions for the three tryptophans in a novel peripheral amphitropic fold. Biophys. J. 2010;99:2626–2635. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuuf J., Wistbacka L., Mattjus P. The glycolipid transfer protein interacts with the vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein VAP-A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;388:395–399. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao X., Coskun U., Rossle M., Buschhorn S.B., Grzybek M., Dafforn T.R., Lenoir M., Overduin M., Simons K. Golgi protein FAPP2 tubulates membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:21121–21125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911789106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vermeer J.E., Thole J.M., Goedhart J., Nielsen E., Munnik T., Gadella T.W., Jr. Imaging phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate dynamics in living plant cells. Plant J. 2009;57:356–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levine T.P., Munro S. Targeting of Golgi-specific pleckstrin homology domains involves both PtdIns 4-kinase-dependent and -independent components. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:695–704. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00779-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Genderen I., van Meer G. Differential targeting of glucosylceramide and galactosylceramide analogues after synthesis but not during transcytosis in Madin–Darby canine kidney cells. J. Cell Biol. 1995;131:645–654. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.3.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Meer G., Stelzer E.H., Wijnaendts-van-Resandt R.W., Simons K. Sorting of sphingolipids in epithelial (Madin–Darby canine kidney) cells. J. Cell Biol. 1987;105:1623–1635. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.4.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wojtal K.A., de Vries E., Hoekstra D., van Ijzendoorn S.C. Efficient trafficking of MDR1/P-glycoprotein to apical canalicular plasma membranes in HepG2 cells requires PKA-RIIalpha anchoring and glucosylceramide. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:3638–3650. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-03-0230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vieira O.V., Gaus K., Verkade P., Fullekrug J., Vaz W.L., Simons K. FAPP2, cilium formation, and compartmentalization of the apical membrane in polarized Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:18556–18561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608291103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halter D., Neumann S., van Dijk S.M., Wolthoorn J., de Maziere A.M., Vieira O.V., Mattjus P., Klumperman J., van Meer G., Sprong H. Pre- and post-Golgi translocation of glucosylceramide in glycosphingolipid synthesis. J. Cell Biol. 2007;179:101–115. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helms J.B., Zurzolo C. Lipids as targeting signals: lipid rafts and intracellular trafficking. Traffic. 2004;5:247–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.0181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Poel S., Wolthoorn J., van den Heuvel D., Egmond M., Groux-Degroote S., Neumann S., Gerritsen H., van Meer G., Sprong H. Hyperacidification of Trans-Golgi Network and Endo/Lysosomes in Melanocytes by Glucosylceramide-Dependent V-ATPase Activity. Traffic. 2011;12:1634–1647. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H., Abraham N., Khan L.A., Hall D.H., Fleming J.T., Gobel V. Apicobasal domain identities of expanding tubular membranes depend on glycosphingolipid biosynthesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;13:1189–1201. doi: 10.1038/ncb2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Matteis M.A., Luini A. Exiting the Golgi complex. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:273–284. doi: 10.1038/nrm2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikonen E., Simons K. Protein and lipid sorting from the trans-Golgi network to the plasma membrane in polarized cells. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 1998;9:503–509. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1998.0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roux A., Cuvelier D., Nassoy P., Prost J., Bassereau P., Goud B. Role of curvature and phase transition in lipid sorting and fission of membrane tubules. EMBO J. 2005;24:1537–1545. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arnold K., Bordoli L., Kopp J., Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]