Abstract

Obesity is associated with an increased risk for malignant lymphoma development. We used Bcr/Abl transformed B cells to determine the impact of aggressive lymphoma formation on systemic lipid mobilization and turnover. In wild-type mice, tumor size significantly correlated with depletion of white adipose tissues (WAT), resulting in increased serum free fatty acid (FFA) concentrations which promote B-cell proliferation in vitro. Moreover, B-cell tumor development induced hepatic lipid accumulation due to enhanced hepatic fatty acid (FA) uptake and impaired FA oxidation. Serum triglyceride, FFA, phospholipid and cholesterol levels were significantly elevated. Consistently, serum VLDL/LDL-cholesterol and apolipoprotein B levels were drastically increased. These findings suggest that B-cell tumors trigger systemic lipid mobilization from WAT to the liver and increase VLDL/LDL release from the liver to promote tumor growth. Further support for this concept stems from experiments where we used the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) agonist and lipid-lowering drug fenofibrate that significantly suppressed tumor growth independent of angiogenesis and inflammation. In addition to WAT depletion, fenofibrate further stimulated FFA uptake by the liver and restored hepatic FA oxidation capacity, thereby accelerating the clearance of lipids released from WAT. Furthermore, fenofibrate blocked hepatic lipid release induced by the tumors. In contrast, lipid utilization in the tumor tissue itself was not increased by fenofibrate which correlates with extremely low expression levels of PPARα in B-cells. Our data show that fenofibrate associated effects on hepatic lipid metabolism and deprivation of serum lipids are capable to suppress B-cell lymphoma growth which may direct novel treatment strategies. This article is part of a Special Issue entitled Lipid Metabolism in Cancer.

Keywords: Cachexia, Lipid metabolism, B-cell lymphoma, Tumor growth, PPAR, Fenofibrate

Highlights

-

•

B-cell lymphoma induced WAT loss and elevated serum FFA.

-

•

B-cell lymphoma caused increased liver mass and FA uptake, impaired hepatic FA oxidation and enhanced hepatic lipid export.

-

•

Fenofibrate reduced lymphoma induced elevation of serum FA by increasing hepatic FA uptake and oxidation.

-

•

Fenofibrate blocks hepatic lipid export as triglyceride-rich VLDL or cholesterol-rich LDL in B-cell lymphoma bearing mice.

-

•

Fenofibrate suppresses B-cell lymphoma in mice.

1. Introduction

Obesity is one of the most common public health problems worldwide as it is associated with metabolic syndrome, hepatosteatosis, atherosclerosis, diabetes, and other metabolic diseases. Recent evidence also firmly linked obesity to an increased risk for developing several malignant tumors. Calle et al. reported that a body mass index (BMI) of > 40 is significantly related to higher rates of death due to cancer of the esophagus, colon and rectum, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, and kidney, as well as multiple myeloma and malignant lymphoma [1]. Malignant lymphoma presents a diverse group of malignancies of the lymphatic system with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma being the most common aggressive form. A meta-analysis of prospective studies regarding the association of BMI with the incidence and mortality for malignant lymphoma revealed that BMI is positively associated with an increased risk for developing diffuse large B-cell and Hodgkin's lymphoma [2]. Elevated hormone levels including adipokines (e.g. leptin [3]) and growth factors (e.g. insulin-like growth factor [4,5]) might partially explain the underlying mechanism. However, a potential direct impact of excess lipid supply on B-cell lymphoma growth and progression remains unclear. Several groups reported decreased serum levels of total cholesterol (TC) and increased triglyceride (TG) concentrations in patients with solid tumors [6–8]. Similar results were observed in hematological malignancies [7,9]. Unfortunately, no data are available for different types of malignant lymphoma such as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Burkitt's lymphoma, which are characterized by one of the fastest growth rates of human malignancies.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) belongs to the nuclear receptor family, which modulates gene transcription in response to specific endogenous and exogenous ligands such as fatty acids (FA) [10] and fibrates [11], respectively. PPARα was originally described as a central regulator of lipid metabolism but also plays a key role in modulating the inflammatory response in various tissues (reviewed in [12]). Its agonists are widely used to treat hyperlipidemic disorders [10]. Recently, tumor suppression mediated by PPARα agonists in various types of tumors (reviewed in [13]) has supported their beneficial “off target” effects against aggressive tumors. The mechanisms and potential connection of the lipid-lowering properties of PPARα agonists to tumor suppression are still poorly understood.

Our study aims to analyze the systemic effects of B-cell tumors on lipid metabolism and to evaluate the lipid-lowering effect of PPARα agonists on B-cell tumor growth using a mouse model. B-cell tumor caused loss of white adipose tissue (WAT) resulting in increased serum FA, TG, phospholipids (PL), TC and free cholesterol levels. Hepatic lipid metabolism was profoundly altered and export of lipids from liver increased. Treatment with the PPARα agonist fenofibrate decreased serum lipid parameters as well as TG- and cholesterol-rich lipoproteins. Tumor growth was dramatically suppressed by fenofibrate. These results indicate that the use of lipid-lowering drugs might be a novel potential approach to treat fast-growing B-cell lymphoma like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animal housing

Ten to twelve week old male C57Bl/6J and PPARα knock-out mice were housed under a 12 h light/dark cycle and permitted ad libitum consumption of water and food. During experiments, food intake and body weight were monitored. All experimental protocols were performed in accordance with animal protocol BMWF-66.010/0110-II/3b/2010, as approved by the Austrian government.

2.2. Creation and maintenance of Bcr/Abl-transformed B-cells

Bcr/Abl-transformed B-cells were created as previously reported [14]. Briefly, bone marrow was isolated from C57Bl/6J mice. Cells were transduced using GFP/p185bcr/abl viral supernatant from Φ-NX (Phoenix) cells. GFP is used as a transduction marker for primary positive cell selection. Candidate cell lineages were further sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) based on expression of the B-cell markers B220, CD43 and CD19. Stable Bcr/Abl-transduced B-cells were selected by puromycin and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS (PAA, Pasching, Austria) in a 37 °C incubator with 5% CO2.

2.3. Lipid supplementation and Wy14643 stimulation

For lipid supplementation experiments, 5 × 105 Bcr/Abl-transduced B-cells were seeded in 9.5 cm2 wells and incubated in 2 mL serum-free medium supplemented with purified human VLDL (Chemicon, Millipore, USA) or Chemically Defined Lipid Concentrate® containing cholesterol (220 mg/L), arachidonic acid (2 mg/L), linoleic acid, linolenic acid, myristic acid, oleic acid, palmitic acid, palmitoleic acid and stearic acid (10 mg/L each) (Invitrogen, Vienna, Austria). After 24 h, cells were counted in a CASY cell counter (Schärfe System GmbH, Germany). For Wy14643 (Cayman Chemical, Michigan, USA) stimulation, cells were seeded as mentioned above, treated with 50 μM Wy14643, and harvested after 24 h (for RNA extraction) or analyzed after 24, 48, 72 h, respectively, to determine growth characteristics.

2.4. Tumor implantation, feeding and tissue harvesting

Animals were divided into four groups as indicated. 1.5 × 105 Bcr/Abl-transformed B-cells, obtained from an exponentially proliferating cell culture, or saline solution as negative control were injected subcutaneously at dorsum below the neck. Mice were fed with regular chow diet (4.5% w/w fat) or chow diet mixed with 0.2% w/w fenofibrate (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany). After 13 to 15 days (for tumor-WAT correlation) or 13 days (fenofibrate treatment), mice were anesthetized using isoflurane and blood was isolated by retro-orbital puncture. Thereafter, mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and tissues were rapidly excised, weighed, and either frozen in liquid nitrogen or stored in 4% neutral-buffered formalin for subsequent preparation of paraffin blocks.

2.5. Serum lipid and lipoprotein analysis

Blood was collected as described above and centrifuged for 20 min at 1800g. Serum was stored at − 80 °C until analysis. Serum TG, total and free cholesterol, PL (DiaSys, Germany), and free fatty acids (FFA) (Wako, Germany) were quantified spectrophotometrically. Serum lipoproteins were separated by lipid electrophoresis and visualized using the SAS-3 Cholesterol Profile Kit according to the manufacturer's instruction (Helena BioSciences Europe, Sunderland, UK). The lipoprotein fractions of each electrophoretic pattern were quantified by densitometry and evaluated according to the integrated densitometric peak areas [15]. In the human sample, the α band with the fastest migration corresponds to HDL while the slowest β band indicates LDLs and pre-β in between corresponds to VLDL. 200 μL plasma pools from each condition were subjected to fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) (Pharmacia P-500; Pfizer Pharma, Karlsruhe, Germany) equipped with a Superose 6 column (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Lipoproteins were eluted with 10 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.9% NaCl, and 0.02% NaN3 (pH 7.4). Total cholesterol (TC) and triglyceride (TG) concentrations in 0.5 mL fractions were measured enzymatically (TC: Greiner Diagnostics AG, Bahlingen, Germany; TG: DiaSys, Holzheim, Germany). To enhance sensitivity, sodium 3,5-dichloro-2-hydroxy-benzenesulfonate was added to the reaction buffer. Quantitative immunoturbidimetric assays for apolipoprotein (Apo) B, ApoCII, and ApoCIII were obtained from Rolf Greiner Biochemica (Flacht, Germany). Assays were performed on a Hitachi 917 automated analyzer (Boehringer Mannheim, Germany).

2.6. Quantitative reverse transcription real-time PCR

Real time PCR was performed as described previously [16]. Total RNA was extracted from liver, dissected tumor tissue or cultured cells using Trizol LS (Invitrogen, Vienna, Austria). cDNA was synthesized with High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Vienna, Austria). For qPCR, SYBR Green PCR Master Mix from Invitrogen and the Applied Biosystems 7900 HT Sequence Detection System were used. Primers sequences are available upon request.

2.7. Hepatic TG and FFA determination

Liver samples were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), weighed and frozen. Total lipids were extracted by the method of Folch [17]. Lipids were dried and reconstituted by brief sonication in 0.1% Triton-X 100. TG and FFA contents were quantified as described above. For histology, two μm thick frozen liver sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Oil Red O staining.

2.8. Tissue FA uptake

Liver and tumor tissues were excised, weighed, and 30–50 mg pieces were used for the assay. Tissues were washed with PBS containing 5 mM EDTA and 0.1% (w/v) BSA. Tissue samples were cut into 3 mm2 size pieces and washed with PBS containing 5 mM EDTA. The substrate containing 2.5 mM oleate:BSA complex and 2 μCi/mL [14C] oleate as radioactive tracer was incubated with the samples in a 24-well plate for 1 h at 37 °C under regular shaking. [14C] oleate uptake and remaining radioactivity in the medium were determined by liquid scintillation counting. The amount of absorbed FA was calculated by determining (initial–final radioactivity in the media) and normalized by protein content as determined by the DC™ Protein Assay (Bio-Rad, Austria) according to the manufacturer protocol.

2.9. Histology and immunohistochemistry

Tumors of sacrificed mice were carefully isolated, fixed in 4% neutral buffered formaldehyde solution for 24 h and embedded in paraffin while livers were frozen in liquid nitrogen. 2 μm thick sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Caspase-3, CD31, Ki67 and F4/80 IHC were performed using specific antibodies against active caspase-3 (R&D, USA), CD31 (Thermo scientific, USA), Ki67 (Novocastra, UK) and F4/80 (Serotec, USA) respectively and appropriate secondary antibodies as previously described [16]. For determination of vessel density, the slides were scanned and CD31-positive cells were quantified and normalized to total analyzed area using ScanScope software (Aperio technologies, USA). For quantification of caspase-3 positive cells, the slides were scanned at 40 × magnification and manually quantified in 60 power fields.

2.10. ELISA

TNFα and IL-6 quantitative ELISA kits were purchased from eBioscience (Vienna, Austria). For serum samples, diluted serum (1:2) was loaded. For tumor lysates, 40–60 mg frozen samples were homogenized by MagNa Lyzer (Roche, Germany) for 3 × 15 s at 6500g in RIPA lysis buffer with proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Pierce, Germany), then kept on ice for 20 min. After centrifugation for 10 min at 4000g, protein concentrations in lysates were determined as described above. 50 μg proteins were loaded in each 96-well plate. ELISA was performed according to the manufacturer protocol.

2.11. Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5. Statistical significance was determined by the Student's unpaired two-tailed t test. Correlation was studied by Pearson's correlation test. Group differences were considered significant for P < 0.05 (*, #, §), P < 0.01 (**, ##, §§), P < 0.001 (***, ###, §§§).

3. Results

3.1. Influence of PPARα agonists on B-cell proliferation in vivo and in vitro

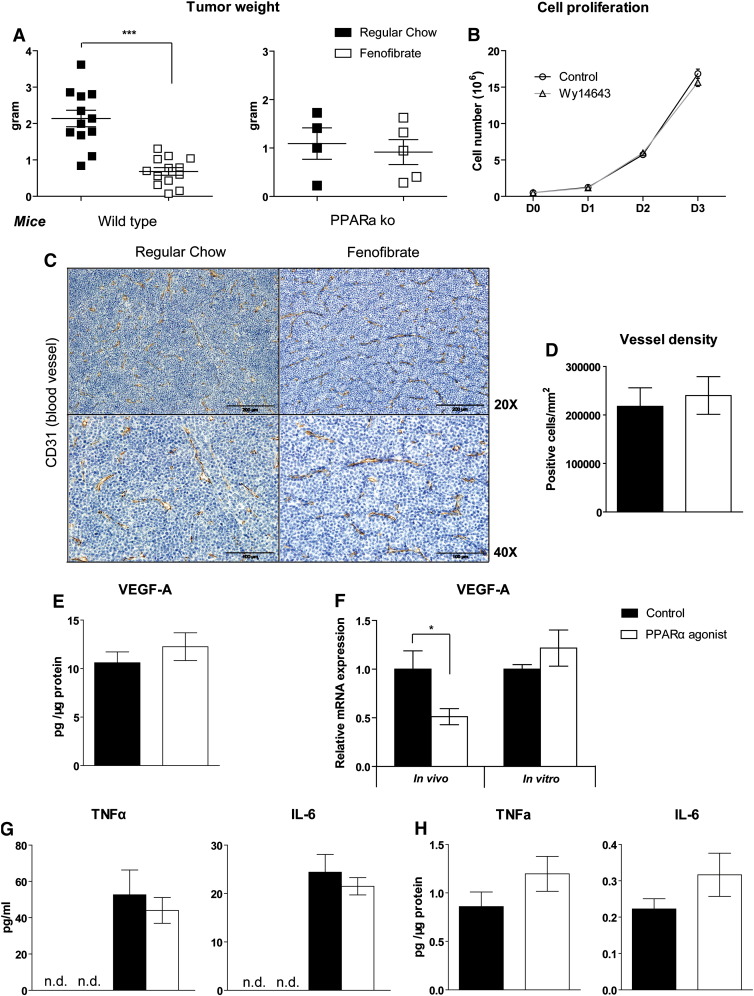

We confirmed the high proliferation rate of Bcr/Abl B-cells in vivo using subcutaneous implantation with low cell number and under short term conditions as well as in vitro by counting cell doubling time (data not shown). Fenofibrate is a serum lipid lowering drug that acts by stimulating PPARα activation [11] and possesses anti-tumorigenic properties against several tumor types [13]. In line with this report 0.2% fenofibrate treatment for 13 days significantly suppressed Bcr/Abl transduced B-cell tumor proliferation in vivo in wild-type mice (− 68.1%, P < 0.001) but not in PPARα knock-out mice (− 16.1%, P = 0.681) (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, although B-cell tumors in PPARα knock-out mice were not sensitive to fenofibrate, tumors in PPARα knock-out mice were smaller than in wild type mice (− 57.3%, P = 0.03). To determine whether PPARα activation directly inhibits tumor cell proliferation, we investigated the impact of a PPARα agonist on B-cell proliferation in vitro. As fenofibrate (a methylethyl ester of fenofibric acid) requires de-esterification via a hepatic esterase to its phamacologically active form—fenofibric acid [18,19], we used the PPARα agonist Wy14643 which does not need activation and shares similar properties with fenofibrate regarding lipid metabolism and tumor suppression for in vitro experiments. Surprisingly, Wy14643 failed to alter growth of Bcr/Abl transformed B-cells in vitro (Fig. 1B). The tumor suppressive effects of PPARα agonists have been attributed to the inhibition of angiogenesis. In contrast to previous findings in B16-F10 melanoma models [20], no significant differences regarding tumor vessel density were found in lymphomas treated with fenofibrate (Fig. 1C, D). In agreement with this finding, vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) protein expression in tumor lysates was not affected by fenofibrate treatment (Fig. 1E). Despite the lack of effects on protein expression, vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) mRNA was significantly downregulated in tumor tissue after fenofibrate treatment (Fig. 1F). Interestingly, no change of VEGF-A expression was detected in vitro after Wy14643 treatment (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

Fenofibrate suppresses B-cell tumor growth independent of angiogenesis and inflammation.

(A) Tumor weights in wild type (wt) mice (n = 13 for each group) and PPARα knock-out (ko) mice (n = 4–5 per group) fed with regular chow or chow supplemented with 0.2% (w/w) fenofibrate were determined on day 13 after mice had been injected subcutaneously with Bcr/Abl-transformed B-cells. (B) The effect of Wy14643 (50 μM) on B-cell proliferation in 10% FBS media was assessed by counting the cell number (n = 3). (C) Immunohistochemical staining of CD31 on sections of paraffin-embedded tumor specimen from wt mice. (D) Number of CD31 positive cells/mm2 tumor area (n = 5). (E) VEGF-A protein content in tumor lysates quantified by ELISA. (F) VEGF-A mRNA expression in vivo and in vitro after PPARα stimulation (fenofibrate in vivo and WY14643 in vitro, respectively) (n = 4). TNFα and IL-6 in (G) serum or (H) tumor lysates were determined by ELISA (n = 7). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

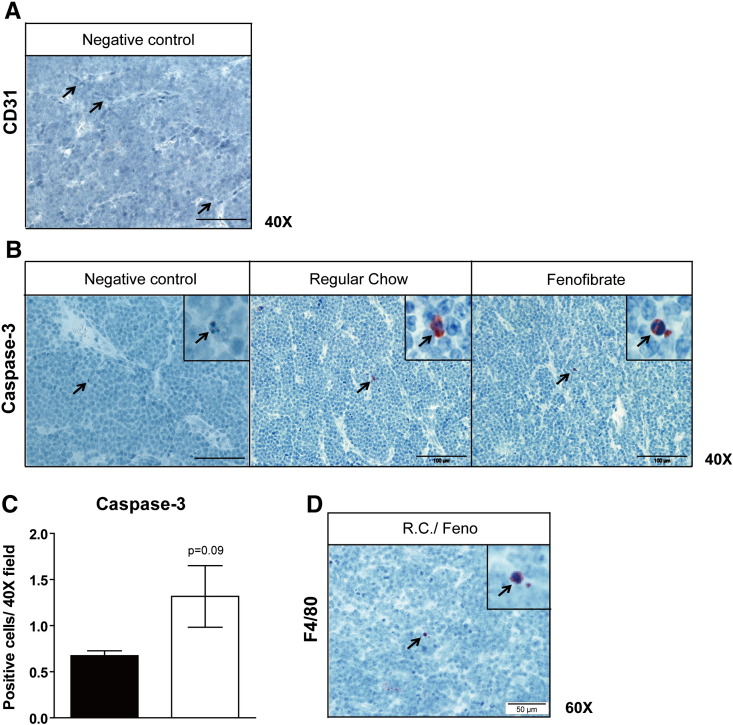

Pro-apoptotic property of fenofibrate was reported in mantle cell lymphoma in vitro [21]. However, in our tumor model, apoptotic cells were only rarely observed in fenofibrate treated as well as untreated tumors (Fig. S1B). Albeit we did find a small but not significant increase of apoptotic cells upon fenofibrate treatment (Fig. S1C), the low total number of apoptotic cells in tumors rules out that these differences account for the observed reduction in tumor growth.

Fig. S1.

Fenofibrate suppresses tumor independent on angiogenesis, apoptosis and inflammation. Immunohistochemical staining of (A) CD31 (negative control), (B) active caspase 3 and (D) F4/80 on sections of paraffin-embedded tumor specimen from wt mice. (C) Number of active caspase 3 positive cells quantified at 40 × magnification in 60 high power fields (n = 5). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

Anti-inflammatory properties of fenofibrate have been reported [12,22] and may modulate the interaction of the B-cell tumor with PPARα positive inflammatory cells in the tumor microenvironment. Several inflammatory mediators (e.g. IL-6) are integral to Bcr/Abl driven tumorigenesis [23,24] and associated with poor outcome of B-cell lymphoma [25]. We therefore determined TNFα and IL-6 concentrations in serum and tumor lysates. Both were undetectable in the control group while highly expressed in tumor bearing mice (Fig. 1G). Remarkably, fenofibrate treatment did not reduce their level in tumor bearing mice (Fig. 1G, H). This might be related to the low level of tumor infiltrating macrophages (Fig. S1D).

3.2. B-cell tumors and fenofibrate treatment induce loss of WAT while fenofibrate reverses tumor-induced increased serum FFA levels

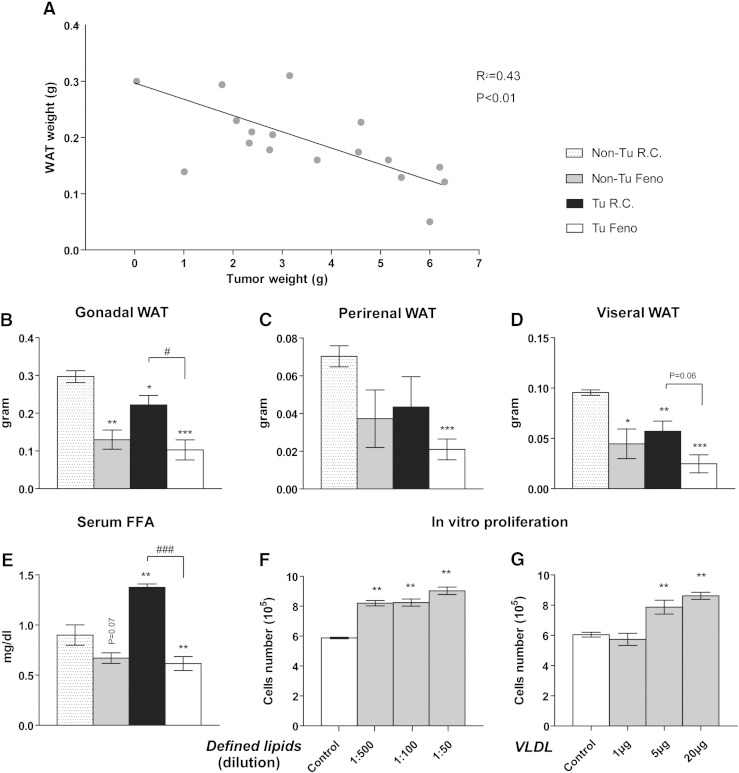

As Bcr/Abl-transformed B-cell tumors grow very rapidly in vivo and in vitro we speculated that there might be an increased demand for nutrients such as FFA that in vivo might be supplied by systemic lipid mobilization. Indeed, loss of WAT was observed in tumor bearing wild type mice and a clear inverse correlation between tumor weight and WAT weight was observed (R2 = 0.43, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2A). To account for the potential effect of very large tumor size on metabolic regulation and energy expenditure we monitored food intake (Fig. S3) and checked the physiological state of the animals from the time tumors became palpable until the end of the experiment. Food intake did not differ significantly among experimental groups and was not correlated to tumor size (non-tumor group average 4.22 g, < 4 g tumor group 4.07 g, > 4 g tumor group 3.82 g per day). We also did not detect abnormal behavior or overt signs of discomfort or sickness. WAT loss differed among WAT types. A significant loss of 40.3% and 25.3% was detected in visceral and gonadal WAT, respectively, while it was not significant in perirenal WAT (− 38.2%, P = 0.13) compared to control (Fig. 2B–D). These data indicate an association between tumor growth and lipolysis. Consistent with this finding, an increase of serum FFA levels (52.8%, P < 0.004) was observed in tumor bearing mice compared to healthy controls (Fig. 2E). It is conceivable that the released FFA might directly support B-cell growth. To address this, we subjected Bcr/Abl transformed B-cells in vitro to media containing defined lipid mixture consisting of multiple types of FA and cholesterol or purified human VLDL. Indeed, both the lipid mixture as well as purified VLDL increased B-cell proliferation in vitro significantly by 53.6% and 42.6%, respectively (Fig. 2F, G).

Fig. 2.

B-cell tumors induce WAT loss and elevation of serum FFA.

(A) Inverse correlation between tumor weight and gonadal WAT weight (n = 17) determined 13–15 days after tumor cell injection. Significance was studied by Pearson's correlation test. (B) Gonadal, (C) perirenal and (D) visceral WAT weights and (E) serum FFA concentration of mice (Tu: tumor-bearing; Non-Tu: non-tumor control), fed with regular chow (R.C.) or fenofibrate-supplemented chow (Feno) after 13 days of treatment. (F, G) In vitro cell proliferation after lipid supplement. (F) Chemically Defined Lipid Concentrate® (Gibco®) or (G) purified human VLDL was added into serum-free RPMI media and the cell number was determined after 24 h. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3–5). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01;***, P < 0.001 denote significant differences compared to non-tumor bearing mice fed with regular chow (Non-Tu R.C.) while # or § denote significant differences compared to tumor-injected mice fed with regular chow (Tu R.C.) or non-tumor mice fed with fenofibrate-containing chow (Non-Tu Feno), respectively.

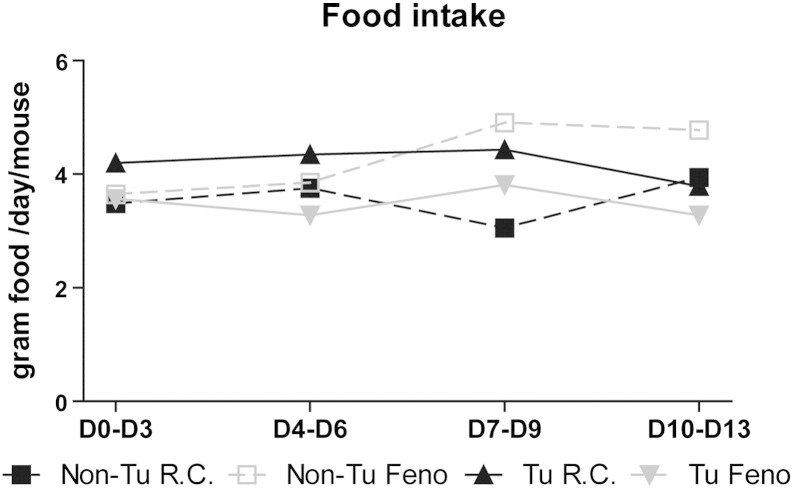

Fig. S3.

Food intake. Results are presented as mean intake per day per mouse (measured in three day intervals). Non-Tu R.C., non-tumor bearing mice fed with regular chow; Non-Tu Feno, non-tumor bearing mice fed with fenofibrate supplemented chow. Tu R.C., tumor bearing mice fed with regular chow; Tu Feno, tumor bearing mice fed with fenofibrate supplemented chow. (n = 5). No significant differences were detected.

We further speculated that fenofibrate treatment might be able to reverse tumor associated changes in lipid metabolism. In agreement with previous reports in normal (non-tumor) mice [26], fenofibrate induced gonadal WAT loss in non-tumor bearing animals by 56.2% and by 65.4% in tumor bearing animals after 13 days (Fig. 2B). Indeed, fenofibrate reversed the tumor-induced increase of serum FA and lowered it by 31.6%, (P < 0.001) while there was no significant FFA lowering effect in non-tumor bearing control mice (Fig. 2E).

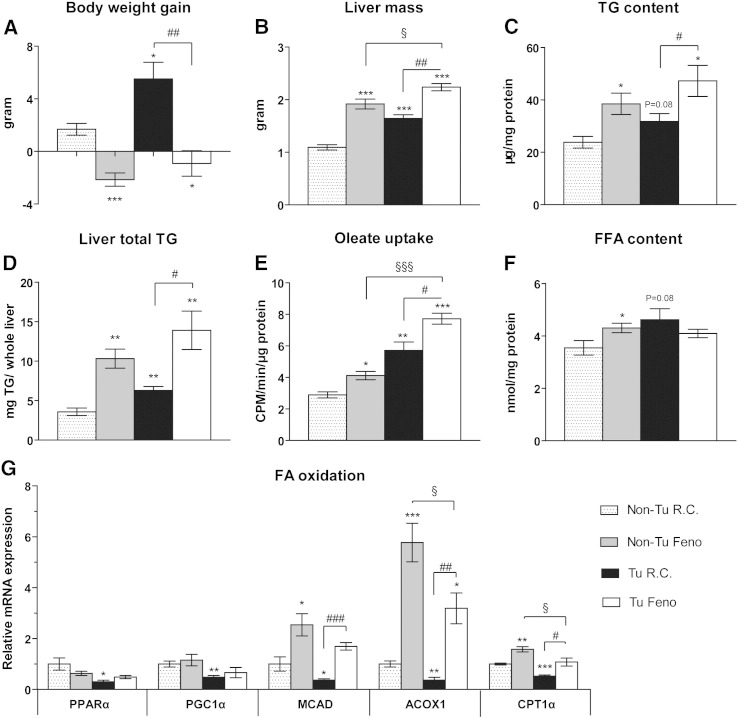

3.3. Impact of fenofibrate on tumor induced impairment of hepatic lipid metabolism

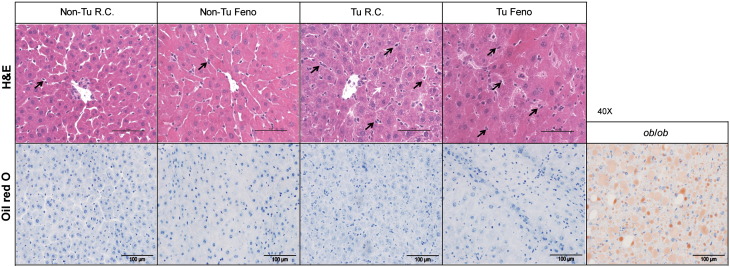

As the liver is the main organ for uptake of FFA released from WAT and subsequent esterification into TG for storage or export into the circulation [27], hepatic lipid turnover might be an important factor modulating the cachexia-associated effects conferred by B-cell tumor growth. In spite of WAT loss, total body weight increased in tumor-bearing mice mainly due to increased liver and spleen mass and severe skin edema (Fig. 3A, B and Fig. S2), whereas food intake did not differ significantly (Fig. S3). Fenofibrate treatment reduced body weight while increasing liver mass both in tumor-bearing (Tu) and non-tumor bearing control mice (Fig. 3A, B). As expected, fenofibrate treatment was accompanied by an increased percentage of Ki67 positive cells as determined by immunohistochemistry (data not shown). The reduction in body weight in tumor bearing fenofibrate treated mice is likely due to the lack of skin edema. Strikingly, liver mass was also increased by 50.1%, (P < 0.001) in tumor-bearing mice receiving regular chow (Fig. 3B). In addition to increased lipid storage, proliferation of hepatocytes as shown by an increased mitotic rate (Fig. S4) and by an increased percentage of Ki67 positive cells determined by immunohistochemistry (data not shown) might substantially contribute to the observed increased liver mass. Relative hepatic TG content was not significantly altered in tumor-bearing mice fed with regular chow, whereas fenofibrate treatment increased TG storage in non-tumor and tumor-bearing mice by 61.4% and 91.2%, respectively, compared with non-tumor bearing mice fed with regular chow (Fig. 3C). Increased total liver TG content was found in tumor-bearing mice fed with regular chow (75.8%, P = 0.008) with additional increments of liver TG content in the two fenofibrate-treated groups (188.2%, P = 0.002 for non-tumor bearing and 288.7%, P = 0.008 for tumor-bearing mice) (Fig. 3D). Consistently, oleate uptake was enhanced by 42.2% in the liver of non-tumor bearing fenofibrate treated mice, by 97.3% in tumor bearing mice fed regular chow and by 166.6% in tumor bearing fenofibrate treated mice (Fig. 3E). However, only non-tumor bearing fenofibrate treated mice showed a significantly increased FFA content (21.4%, P = 0.05). This might be attributed to accelerated FA esterification in tumor bearing mice.

Fig. 3.

Tumor growth and fenofibrate feeding increase hepatic lipid content and FA uptake. Fenofibrate increases FA oxidation in liver which is inhibited in tumor bearing mice.

(A) Carcass body weight gain and (B) liver weight were recorded 13 days after tumor cell or saline injection in fenofibrate-treated or control mice. (C) Hepatic TG content was determined and (D) total liver TG content was calculated as (mg TG/mg liver sample × liver weight (mg)). (E) Ex vivo [14C] oleate uptake and (F) hepatic FFA concentrations were quantified (G) Expression profiles of PPARα target genes involved in FA oxidation in the liver. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 4–5). Tu: tumor-bearing; Non-Tu: non-tumor (saline) injected controls, fed with regular chow (R.C.) or fenofibrate-supplemented chow (Feno). * denotes significant differences compared with non-tumor injected mice fed with regular chow (Non-Tu R.C.); # and § denote significant differences compared with tumor-injected mice fed with regular chow (Tu R.C.) or non-tumor injected mice fed with fenofibrate-containing chow (Non-TuFeno) group, respectively.

Fig. S2.

Macroscopic view of skin edema in a tumor bearing mouse representative figure from one female mouse 13 days after tumor cell injection.

Fig. S4.

Histology of liver samples.

Frozen liver samples were stained with H&E and oil O red respectively. Liver from obese ob/ob mice was used as positive control in O red staining. A representative image from each group is shown. Between the hepatocytes of tumor bearing mice an increased number of Kupffer cells (as indicated by black arrows) is found. White arrow indicates a mitotic figure of a hepatocyte.

PPARα-mediated hepatic FA oxidation plays a critical role in clearing intracellular lipids from the liver [28]. Notably, mRNA expression levels of PPARα and its target genes PGC1α, CPT1α, ACOX1 and MCAD were down-regulated in tumor-bearing mice compared with control mice fed with regular chow. In fenofibrate-treated mice, reduced mRNA levels of the PPARα target genes CPT1α, ACOX1 and MCAD in tumor-bearing mice were restored to or even beyond normal levels but did not reach the same level as in non-tumor bearing fenofibrate-treated mice [Fig. 3G]. These results suggest that FA β-oxidation is impaired by tumor growth.

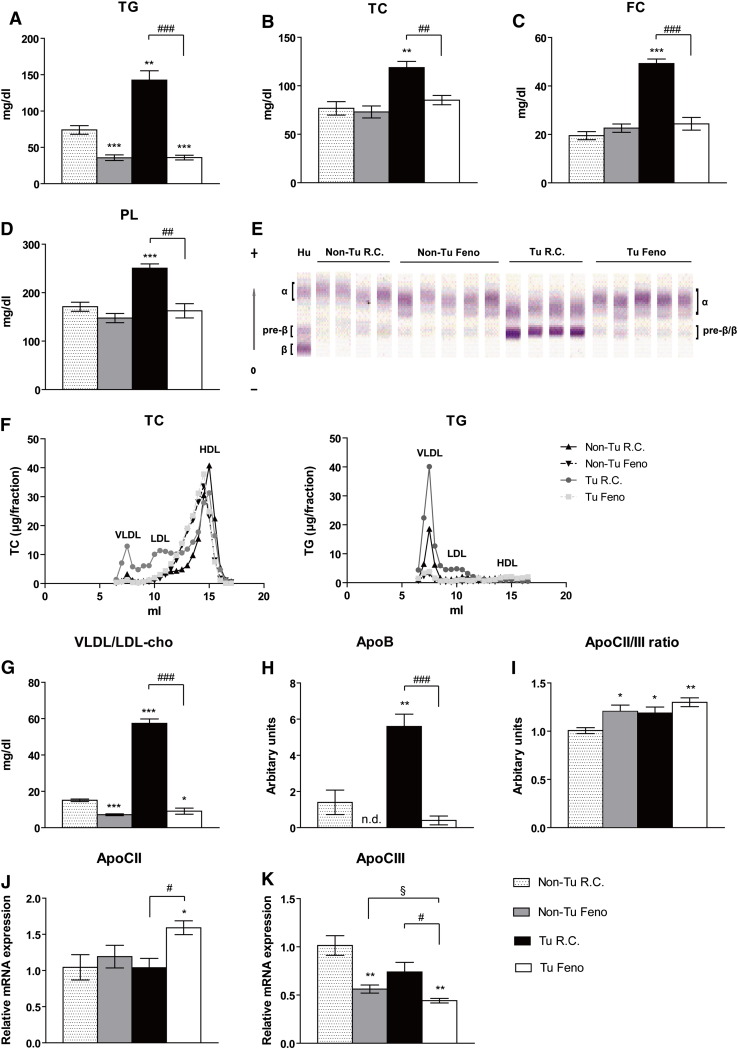

3.4. Impact of fenofibrate on tumor-induced hepatic lipid release

The liver is the main organ for TG and cholesterol synthesis, which are released as lipoproteins into the circulation [27]. Serum levels of TG, total cholesterol, free cholesterol and PL were increased in tumor-bearing mice compared with non-tumor bearing control mice (by 92.6%, 54.7%, 152.6%, and 36.5%, respectively) (Fig. 4A–D). Interestingly, fenofibrate treatment completely reversed this increase (− 51.4%, 11%, 25.1% and − 4.9%, respectively, compared with non-tumor bearing control mice) and lowered lipid levels to those of non-tumor bearing fenofibrate-treated mice (Fig. 4A–D).

Fig. 4.

Fenofibrate suppresses tumor-induced hepatic lipid export.

(A–D) Serum triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), free cholesterol (FC), and phospholipids (PL) were determined. (E) VLDL, LDL, and HDL in serum were separated by lipid electrophoresis. Human serum (Hu) was used as a positive control: the α band corresponds to HDL whereas the β band indicates LDL, pre-β corresponds to VLDL. Lipoproteins were visualized by enzymatic staining and VLDL/LDL percentage was determined by densitometry and quantified by Platinum Software according to the integrated densitometric peak areas and their (G) cholesterol concentrations were calculated based on the formula “percentage × TC concentration”. (F) Lipoprotein analyses by FPLC. Distribution of TC and TG in pooled plasma from mice (n = 4–5) of two independent experiments. TC and TG concentrations after FPLC separation were determined spectrophotometrically. (H) ApoB, (I) ApoCII, and ApoCIII were determined by immunoturbidimetric assays. The ratio of ApoCII/III was calculated manually. The transcript levels of (J) ApoCII and (K) ApoCIII were also checked by qPCR. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 4–5). * denotes significant differences compared with non-tumor injected mice fed with regular chow (Non-Tu R.C.); # denotes significant differences compared with tumor-injected mice fed with regular chow (Tu R.C.).

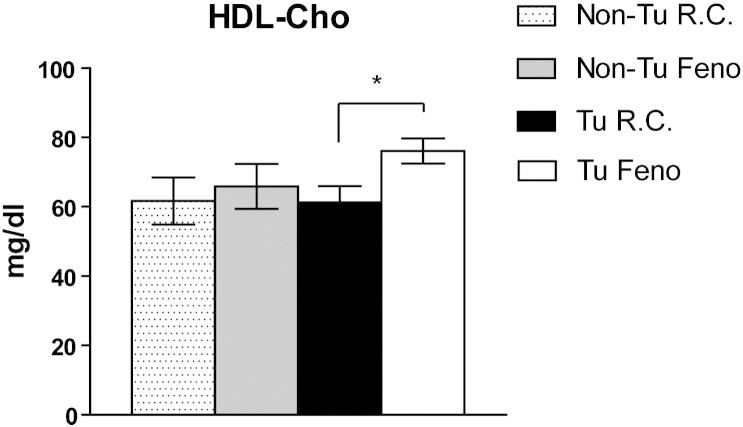

To determine which lipoprotein(s) are responsible for the observed increase of serum lipids in B-cell tumor-bearing mice, we performed lipid electrophoresis. We found the band with lowest mobility to be drastically increased compared to other lipoproteins detectable in tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 4E). Fenofibrate treatment reduced this band to normal levels in tumor-bearing mice. In humans, HDL, VLDL, and LDL are termed α, pre-β, and β bands, respectively, based on their characteristic surface charges [15]. We therefore speculate that the lower band in tumor-bearing mice is a fused band of pre-β and β lipoproteins equivalent to VLDL and LDL. Further FLPC analysis confirmed the profound increase in VLDL accompanied by LDL in tumor bearing mice fed with regular chow compared to control mice (Fig. 4F). Fenofibrate reduced VLDL level in non-tumor bearing mice and depleted VLDL and LDL dramatically in tumor bearing mice (Fig. 4F). Increased cholesterol in tumor-bearing mice corresponds to VLDL/LDL-cholesterol (281.1%, Fig. 4G) but not to HDL-cholesterol (Fig. S5). In agreement with these observations, the serum concentration of ApoB, which is found in lipoproteins originating from liver (VLDL, IDL, LDL) or intestine (chylomicron) and is well established as a predictor of VLDL/LDL levels, was increased by 3-fold in tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 4H). As expected, fenofibrate remarkably reduced serum VLDL/LDL-cholesterol and ApoB to levels similar as in non-tumor bearing fenofibrate-treated mice (Fig. 4G, H). ApoCII and CIII are protein components of VLDL; their ratio (ApoCII/III) reflects LPL activity in capillaries. In tumor-bearing mice, the serum ApoCII/III ratio was slightly increased (18.7%, P = 0.03) (Fig. 4I) although basal ApoCII and CIII levels were not significantly changed in circulation or in liver (Fig. 4J, K). One might speculate that more LPL-sensitive VLDL is available in the circulation, thus favoring utilization by the tumor. Similarly, both fenofibrate-treated groups (non-tumor and tumor-bearing mice) had an increased serum ApoCII/III ratio (20.6%, P = 0.02 and 30%, P < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 4H) and hepatic transcript level of ApoCII increased by 52.4% while ApoCIII deceased by – 56.4% in tumor bearing mice fed with fenofibrate (Fig. 4J, K). Increased ApoCII/III ratio upon fenofibrate might accelerate utilization of TG-rich lipoproteins in peripheral organs.

Fig. S5.

Impact of tumor and fenofibrate on serum HDL-cholesterol. Lipid electrophoresis was performed and HDL cholesterol was visualized by enzymatic staining. Concentrations were determined by densitometry and quantified using Platinum Software according to the integrated densitometric peak areas. *P < 0.05 denotes significant difference (n = 4–5).

3.5. Response of tumor to WAT loss in fenofibrate-treated mice

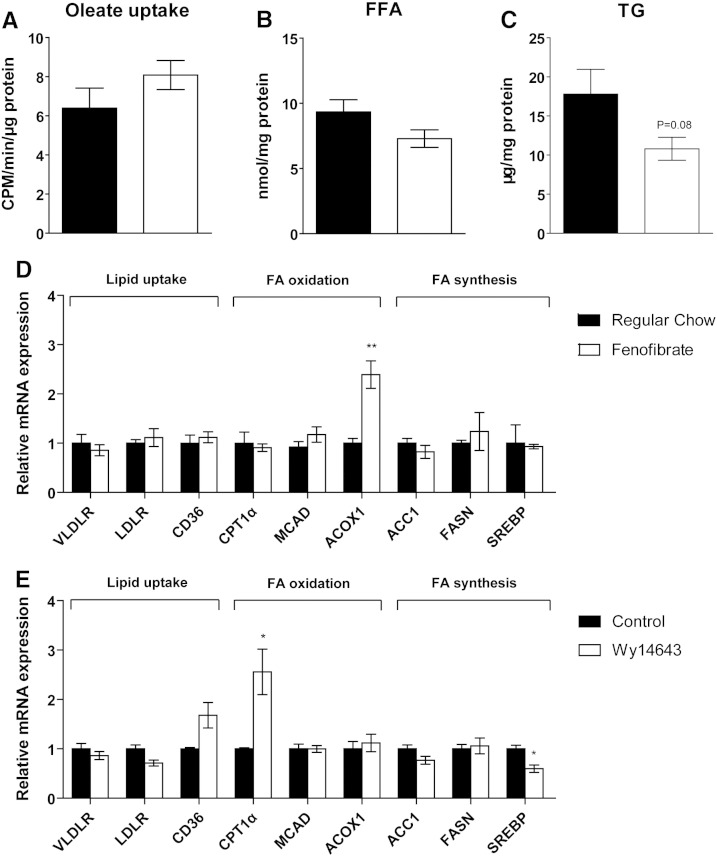

As described above, tumor-induced WAT loss resulted in increased hepatic FA uptake and increased liver mass in fenofibrate-fed mice. In contrast, the FA uptake by the tumor remained unchanged in fenofibrate-treated mice (Fig. 5A). In line with this result, intracellular FFA and TG contents were unaltered (Fig. 5B, C). Similarly, the expression of genes involved in lipid uptake (VLDLR, LDLR, CD36) and FA synthesis (ACC1, FASN, SREBP1) were unaltered both in vivo and in vitro (Fig. 5D, E). The fact that PPARα mRNA expression was not detectable by real time PCR (data not shown) most likely accounts for the lack of response of B-cell tumors to fenofibrate in vivo or to Wy14643 in vitro. This assumption is further supported by the fact that the PPARα targets (CD36, MCAD, and ACOX1) generally showed no significant responses to PPARα agonist in vivo and in vitro (Fig. 5D, E). These data and the fact that tumor growth was unaltered by fenofibrate treatment in PPARα knockout mice (Fig. 1B) strongly suggest that fenofibrate suppresses B-cells' tumor growth independent of PPARα activation in the B-cell tumor by reversing tumor induced changes in the lipid metabolism of recipient mice.

Fig. 5.

Unaltered tumor lipid metabolism in fenofibrate-treated mice due to absence of PPARα expression in tumor.

(A) Oleate uptake, (B) intracellular FFA, and (C) TG concentrations in tumors after fenofibrate treatment. The impact of (D) fenofibrate in vivo and (E) Wy14643 in vitro on the expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3–5). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

4. Discussion

The clear link between obesity and increased probability to develop cancer fuels the interest in changes in systemic lipid metabolism that may promote tumor development and progression. As a consequence lipid lowering drugs may provide novel therapeutic options to treat patients suffering from various types of tumors. Most cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma directly arise from regular B cells. In addition other types of lymphoma such as follicular lymphoma may transform into diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [29]. In this study we explored murine Bcr/Abl transformed B-cells [30] as an experimental model for fast-growing B-cell tumors such as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma to investigate the effects of the growing tumor on systemic lipid mobilization and distribution. The rapidly growing Bcr/Abl transformed B-cells induced a significant loss of WAT in close correlation with tumor-weight. Loss of WAT was accompanied by elevated serum FFA. FFA directly increased the proliferation of Bcr/Abl B-cells, as was clearly visible from our experiments using lipid supplement in vitro. Both a simple lipid formulation (FFA and cholesterol) and complex lipid form (VLDL) increased proliferation of Bcr/Abl B-cells. No hints for any lipotoxic effects such as an increased rate of apoptosis were detectable. To sustain the rapid proliferation rate and to match the high demand of lipids, the lymphoma/leukemia undergoes a metabolic shift either by increasing lipid anabolism via fatty acid synthase [31,32] or by withdrawing lipids from the circulation via LPL [33] or lipoprotein receptors mediated endocytosis. Accelerated lipid utilization mainly by increased lipid oxidation is a hallmark of cancer patients affected by tumor associated cachexia [34]. Surprisingly, in our B-cell tumor model, WAT loss was accompanied by a body weight gain, which is in contrast to our previous finding in Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) or B16 melanoma induced cachexia [35]. A likely explanation for this discrepancy might be the combination of a less severe effect on WAT resulting in an incomplete WAT loss, an increased liver and spleen mass as well as severe skin edema.

The liver is considered the main organ controlling systemic lipid mobilization; however, effects on liver metabolism in the context of tumor-associated cachexia are still poorly understood. Here we show profoundly altered hepatic lipid turnover as well as increased liver mass as a result of B-cell tumor growth. Increased liver mass in the fenofibrate treated groups is likely to be caused by an increased mitotic rate of hepatocytes and by peroxisome proliferation in response to PPARα activation while in the untreated tumor bearing group it might be attributed to hepatocyte proliferation in response to inflammatory mediators (e.g. TNFα, IL-6) released by the lymphoma. Remarkably, fenofibrate treatment did not reduce their level in tumor bearing mice. The low level of tumor infiltrating macrophages as well as the absence of PPARα in Bcr/Abl transformed B cells might explain the insensitivity of B-cell tumors to fenofibrate stimulation with regard to TNFα and IL-6. However, we cannot rule out that fenofibrate might block other pro-inflammatory stimuli thereby influencing tumor growth.

In liver, FA are rapidly esterified into TG, which are either stored within lipid droplets or exported as VLDL. In line with another tumor model [36], hepatic FA oxidation was suppressed in tumor-bearing animals. Notably, genes encoding for FA uptake and de novo lipogenesis did not change significantly (data not shown). Strikingly, serum lipid parameters were remarkably elevated in tumor-bearing mice. Our data strongly indicate that TG and synthesized cholesterol in the liver are transported into the circulation initially by VLDL and secondarily by LDL. The increased removal of lipids from the liver might be compensated by increased hepatic FA uptake and decreased FA oxidation in tumor-bearing mice.

Elevated plasma levels of TG are a hallmark of the metabolic syndrome and a risk factor for atherosclerosis [37]. In addition, VLDL-C/LDL-C are considered as “bad cholesterol” by distributing cholesterol to peripheral organs and hence being associated with the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Aberrant serum lipid profiles might also be connected to tumor development. Patients suffering from cancer have significantly lower plasma cholesterol, HDL-C, and LDL-C levels and higher TG concentrations than controls [9]. Similarly, a reduction of TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, and BMI was observed in patients with metastatic compared to patients with non-metastatic solid tumors. However, serum TG were also decreased in these patients [7], indicating that advanced cancer might have distinct effects on serum TG. Recent evidence provided first insights into the role of cholesterol for tumor development. Experimental models revealed that elevated plasma cholesterol levels due to dietary effects accelerate the development and aggressiveness of breast tumors [38]. Supportively, statins, which have been introduced for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia, display antitumor effects against various cancers including lymphoma in animal tumor models [39]. These results argue for an important role of cholesterol in B-cell lymphoma development and progression, in which elevated serum cholesterol (mainly VLDL/LDL-C) concentration and LDL levels were observed.

B-cell tumor-bearing mice developed hyperlipidemia, accompanied by impaired hepatic FA oxidation. Remarkably, these profoundly altered metabolic parameters were reversed by fenofibrate treatment, a commonly used lipid-lowering agent and PPARα agonist. Fenofibrate reversed the elevation of serum lipids in B-cell tumor-bearing mice presumably by one of the following mechanisms or a combination thereof: 1) Increased hepatic FA uptake from circulation, which is supported by studies demonstrating that fibrate promoted hepatic FA uptake by specific FATPs [40]. 2) Accelerated FA catabolism as PPARα plays a pivotal role in promoting FA oxidation in peripheral organs like liver, heart and muscle [28] but not in B-cell tumors as these lack PPARα expression. The resulting marked reduction of serum FFA concentrations consequently leads to FA starvation of the tumor. 3) Reduced cholesterol-rich LDL. Elevated VLDL/LDL-C and LDL levels in tumor-bearing mice were completely reversed by fenofibrate treatment, indicating that fenofibrate starves the tumor from available serum cholesterol. 4) Lowering serum TG concentrations via reducing hepatic TG export as TG-rich VLDL and by enhancing peripheral hydrolysis of VLDL. LPL is the main lipase which hydrolyzes TG from VLDL; its transcriptional level is up-regulated by PPARα agonists via PPAR-responsive elements in its promoter [41]. PPARα agonist treatment could also result in marked depression of hepatic ApoCIII [42,43], a negative regulator in the clearance of TG-rich VLDL through inhibiting enzyme activities of both LPL and hepatic lipase [44]. As a consequence fenofibrate might deprive tumors of available serum TG by reducing TG export and/or increasing the capacity of peripheral organs to utilize TG. The B-cell tumor itself is not affected as it lacks PPARα. Indeed, FA uptake by the tumor tissue remained unchanged upon fenofibrate treatment and intracellular FFA and TG contents were unaltered. Interestingly, although B-cell tumors in PPARα knock-out mice were not sensitive to fenofibrate, tumors in PPARα knock-out mice were smaller than in wild type mice. This might be due to the high level of thrombospondin-1 as angiogenesis inhibitor in circulation in PPARα knock-out mice [45]. Taken together, these data provide evidence that fenofibrate suppresses B-cells tumor growth via cell extrinsic pathways and that the tumor suppressing effects are independent of PPARα activation in the tumor.

To the best of our knowledge our study establishes for the first time that the depletion of WAT in an animal model of B-cell lymphoma is correlated to tumor size and resulted in profound alterations in lipid metabolism. These changes include elevated serum FFA, hepatic lipid accumulation due to increased FA uptake and reduced β-oxidation as well as drastically altered lipoprotein composition. Tumor growth could be inhibited by fenofibrate as this drug is capable of interrupting the systemic changes in lipid metabolism such as hypertriglyceridemia and hypercholesterolemia in B-cell tumor-bearing mice. In view of the high sensitivity of B-cell lymphoma to lipid deprivation, the application of lipid-lowering drugs may hold great promise as novel and innovative therapies against B-cell malignancies such as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Burkitt's lymphoma, and acute B-cell leukemia.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund projects DK-MCD W1226 and SFB LIPOTOX F30, and the PhD Program “Molecular Medicine” of the Medical University of Graz.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This article is part of a Special Issue entitled Lipid Metabolism in Cancer.

References

- 1.Calle E.E., Rodriguez C., Walker-Thurmond K., Thun M.J. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1625–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larsson S.C., Wolk A. Body mass index and risk of non-Hodgkin's and Hodgkin's lymphoma: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. J. Cancer. 2011;47:2422–2430. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skibola C.F., Holly E.A., Forrest M.S., Hubbard A., Bracci P.M., Skibola D.R., Hegedus C., Smith M.T. Body mass index, leptin and leptin receptor polymorphisms, and non-hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:779–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whelan J.T., Ludwig D.L., Bertrand F.E. HoxA9 induces insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor expression in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2008;22:1161–1169. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taslipinar A., Bolu E., Kebapcilar L., Sahin M., Uckaya G., Kutlu M. Insulin-like growth factor-1 is essential to the increased mortality caused by excess growth hormone: a case of thyroid cancer and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in a patient with pituitary acromegaly. Med. Oncol. 2009;26:62–66. doi: 10.1007/s12032-008-9084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muntoni S., Atzori L., Mereu R., Satta G., Macis M.D., Congia M., Tedde A., Desogus A., Muntoni S. Serum lipoproteins and cancer. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2009;19:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiorenza A.M., Branchi A., Sommariva D. Serum lipoprotein profile in patients with cancer, a comparison with non-cancer subjects. Int. J. Clin. Lab. Res. 2000;30:141–145. doi: 10.1007/s005990070013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kokoglu E., Karaarslan I., Karaarslan H.M., Baloglu H. Alterations of serum lipids and lipoproteins in breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 1994;82:175–178. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(94)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuliszkiewicz-Janus M., Malecki R., Mohamed A.S. Lipid changes occurring in the course of hematological cancers. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2008;13:465–474. doi: 10.2478/s11658-008-0014-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forman B.M., Chen J., Evans R.M. Hypolipidemic drugs, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and eicosanoids are ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and delta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:4312–4317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Willson T.M., Brown P.J., Sternbach D.D., Henke B.R. The PPARs: from orphan receptors to drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2000;43:527–550. doi: 10.1021/jm990554g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chinetti G., Fruchart J.C., Staels B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): nuclear receptors at the crossroads between lipid metabolism and inflammation. Inflamm. Res. 2000;49:497–505. doi: 10.1007/s000110050622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters J.M., Shah Y.M., Gonzalez F.J. The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in carcinogenesis and chemoprevention. Nat. Rev. 2012;12:181–195. doi: 10.1038/nrc3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoelbl A., Schuster C., Kovacic B., Zhu B., Wickre M., Hoelzl M.A., Fajmann S., Grebien F., Warsch W., Stengl G., Hennighausen L., Poli V., Beug H., Moriggl R., Sexl V. Stat5 is indispensable for the maintenance of bcr/abl-positive leukaemia. EMBO Mol. Med. 1992;2:98–110. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sparks D.L., Phillips M.C. Quantitative measurement of lipoprotein surface charge by agarose gel electrophoresis. J. Lipid Res. 1992;33:123–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamilarasan K.P., Temmel H., Das S.K., Al Zoughbi W., Schauer S., Vesely P.W., Hoefler G. Skeletal muscle damage and impaired regeneration due to LPL-mediated lipotoxicity. Cell death Dis. 2012;3:e354. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folch J., Lees M., Sloane Stanley G.H. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Issemann I., Green S. Activation of a member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily by peroxisome proliferators. Nature. 1990;347:645–650. doi: 10.1038/347645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tziomalos K., Athyros V.G. Fenofibrate: a novel formulation (Triglide) in the treatment of lipid disorders: a review. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2006;1:129–147. doi: 10.2147/nano.2006.1.2.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panigrahy D., Kaipainen A., Huang S., Butterfield C.E., Barnes C.M., Fannon M., Laforme A.M., Chaponis D.M., Folkman J., Kieran M.W. PPARalpha agonist fenofibrate suppresses tumor growth through direct and indirect angiogenesis inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:985–990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711281105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zak Z., Gelebart P., Lai R. Fenofibrate induces effective apoptosis in mantle cell lymphoma by inhibiting the TNFalpha/NF-kappaB signaling axis. Leukemia. 2010;24:1476–1486. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pyper S.R., Viswakarma N., Yu S., Reddy J.K. PPARalpha: energy combustion, hypolipidemia, inflammation and cancer. Nucl. Recept. Signal. 2010;8:e002. doi: 10.1621/nrs.08002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang L., Yang J., Qian J., Li H., Romaguera J.E., Kwak L.W., Wang M., Yi Q. Role of the microenvironment in mantle cell lymphoma: IL-6 is an important survival factor for the tumor cells. Blood. 2012;120:3783–3792. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-424630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta M., Maurer M.J., Wellik L.E., Law M.E., Han J.J., Ozsan N., Micallef I.N., Dogan A., Witzig T.E. Expression of Myc, but not pSTAT3, is an adverse prognostic factor for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with epratuzumab/R-CHOP. Blood. 2012;120:4400–4406. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-428466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charbonneau B., Maurer M.J., Ansell S.M., Slager S.L., Fredericksen Z.S., Ziesmer S.C., Macon W.R., Habermann T.M., Witzig T.E., Link B.K., Cerhan J.R., Novak A.J. Pretreatment circulating serum cytokines associated with follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a clinic-based case-control study. Cytokine. 2012;60:882–889. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeong S., Yoon M. Fenofibrate inhibits adipocyte hypertrophy and insulin resistance by activating adipose PPARalpha in high fat diet-induced obese mice. Exp. Mol. Med. 2009;41:397–405. doi: 10.3858/emm.2009.41.6.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canbay A., Bechmann L., Gerken G. Lipid metabolism in the liver. Z. Gastroenterol. 2007;45:35–41. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-927368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reddy J.K., Hashimoto T. Peroxisomal beta-oxidation and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha: an adaptive metabolic system. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2001;21:193–230. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.21.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alizadeh A.A., Eisen M.B., Davis R.E., Ma C., Lossos I.S., Rosenwald A., Boldrick J.C., Sabet H., Tran T., Yu X., Powell J.I., Yang L., Marti G.E., Moore T., Hudson J., Jr., Lu L., Lewis D.B., Tibshirani R., Sherlock G., Chan W.C., Greiner T.C., Weisenburger D.D., Armitage J.O., Warnke R., Levy R., Wilson W., Grever M.R., Byrd J.C., Botstein D., Brown P.O., Staudt L.M. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403:503–511. doi: 10.1038/35000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daley G.Q., Van Etten R.A., Baltimore D. Blast crisis in a murine model of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1991;88:11335–11338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gelebart P., Zak Z., Anand M., Belch A., Lai R. Blockade of fatty acid synthase triggers significant apoptosis in mantle cell lymphoma. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhatt A.P., Jacobs S.R., Freemerman A.J., Makowski L., Rathmell J.C., Dittmer D.P., Damania B. Dysregulation of fatty acid synthesis and glycolysis in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:11818–11823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205995109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pallasch C.P., Schwamb J., Konigs S., Schulz A., Debey S., Kofler D., Schultze J.L., Hallek M., Ultsch A., Wendtner C.M. Targeting lipid metabolism by the lipoprotein lipase inhibitor orlistat results in apoptosis of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Leukemia. 2008;22:585–592. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korber J., Pricelius S., Heidrich M., Muller M.J. Increased lipid utilization in weight losing and weight stable cancer patients with normal body weight. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999;53:740–745. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Das S.K., Eder S., Schauer S., Diwoky C., Temmel H., Guertl B., Gorkiewicz G., Tamilarasan K.P., Kumari P., Trauner M., Zimmermann R., Vesely P., Haemmerle G., Zechner R., Hoefler G. Adipose triglyceride lipase contributes to cancer-associated cachexia. Science. 2011;333:233–238. doi: 10.1126/science.1198973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silverio R., Laviano A., Rossi Fanelli F., Seelaender M. l-carnitine induces recovery of liver lipid metabolism in cancer cachexia. Amino Acids. 2012;42:1783–1792. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-0898-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krauss R.M. Atherogenicity of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. Am. J. Cardiol. 1998;81:13B–17B. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Llaverias G., Danilo C., Mercier I., Daumer K., Capozza F., Williams T.M., Sotgia F., Lisanti M.P., Frank P.G. Role of cholesterol in the development and progression of breast cancer. Am. J. Pathol. 2011;178:402–412. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jakobisiak M., Golab J. Potential antitumor effects of statins (Review) Int. J. Oncol. 2003;23:1055–1069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin G., Schoonjans K., Lefebvre A.M., Staels B., Auwerx J. Coordinate regulation of the expression of the fatty acid transport protein and acyl-CoA synthetase genes by PPARalpha and PPARgamma activators. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:28210–28217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schoonjans K., Peinado-Onsurbe J., Lefebvre A.M., Heyman R.A., Briggs M., Deeb S., Staels B., Auwerx J. PPARalpha and PPARgamma activators direct a distinct tissue-specific transcriptional response via a PPRE in the lipoprotein lipase gene. EMBO J. 1996;15:5336–5348. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peters J.M., Hennuyer N., Staels B., Fruchart J.C., Fievet C., Gonzalez F.J., Auwerx J. Alterations in lipoprotein metabolism in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha-deficient mice. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:27307–27312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qu S., Su D., Altomonte J., Kamagate A., He J., Perdomo G., Tse T., Jiang Y., Dong H.H. PPAR{alpha} mediates the hypolipidemic action of fibrates by antagonizing FoxO1. Am. J. Physiol. 2007;292:E421–E434. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00157.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shachter N.S. Apolipoproteins C-I and C-III as important modulators of lipoprotein metabolism. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2001;12:297–304. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200106000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaipainen A., Kieran M.W., Huang S., Butterfield C., Bielenberg D., Mostoslavsky G., Mulligan R., Folkman J., Panigrahy D. PPARalpha deficiency in inflammatory cells suppresses tumor growth. PLoS One. 2007;2:e260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]