Abstract

Aging is associated with a large number of both phenotypic and molecular changes, but for most of these, it is not known whether these changes are detrimental, neutral, or protective. We have identified a conserved Caenorhabditis elegans GATA transcription factor/MTA-1 homolog egr-1 (lin-40) that extends lifespan and promotes resistance to heat and UV stress when overexpressed. Expression of egr-1 increases with age, suggesting that it may promote survival during normal aging. This increase in expression is dependent on the presence of the germline, raising the possibility that egr-1 expression is regulated by signals from the germline. In addition, loss of egr-1 suppresses the long lifespan of insulin receptor daf-2 mutants. The DAF-16 FOXO transcription factor is required for the increased stress resistance of egr-1 overexpression mutants, and egr-1 is necessary for the proper regulation of sod-3 (a reporter for DAF-16 activity). These results indicate that egr-1 acts within the insulin signaling pathway. egr-1 can also activate the expression of its paralog egl-27, another factor known to extend lifespan and increase stress resistance, suggesting that the two genes act in a common program to promote survival. These results identify egr-1 as part of a longevity-promoting circuit that changes with age in a manner that is beneficial for the lifespan of the organism.

Keywords: aging, Caenorhabditis elegans, GATA, gene regulation, insulin signaling, NuRD, stress

Introduction

Studies in Caenorhabditis elegans have defined a large number of molecular and organismal phenotypes that occur as the animal ages (Herndon et al., 2002; Lund et al., 2002; Golden & Melov, 2004; Huang et al., 2004; Budovskaya et al., 2008; Golden et al., 2008; McGee et al., 2011). However, it is generally not known which of these age-dependent changes are negative and cause aging, which are simply neutral markers of old age, and which exert positive, anti-aging effects. For example, many heat-shock proteins rise in expression until middle age before declining in old age (Lund et al., 2002), but how these changes affect lifespan is not clear.

Previously, the GATA transcription factor egl-27 was shown to both increase expression with age and to have beneficial effects on lifespan and stress tolerance in C. elegans (Xu & Kim, 2012). EGL-27 is homologous to mammalian MTA1, a member of the NuRD chromatin remodeling complex, and also contains GATA DNA-binding domains (Solari et al., 1999). EGL-27 binds to age- and stress-regulated genes, and increased levels of egl-27 extend lifespan and promote stress resistance. Furthermore, egl-27 expression is induced by multiple forms of stress and damage. These results suggest that some proportion of the aging changes are protective.

In developing worms, the function of egl-27 is partially redundant with its paralog egr-1 (also called lin-40). EGR-1 and EGL-27 share the same domain structure and are 22% identical across their shared conserved domains (Solari et al., 1999). Both genes are important for proper cellular organization and fate specification during development, and the embryonic cell patterning phenotype of egr-1; egl-27 double knockdowns is more severe than the phenotype of either single mutant alone (Solari et al., 1999; Chen & Han, 2001). This result indicates that the two genes have shared functions and that inactivation of these functions is only achieved by knockdown of both simultaneously. Because these genes seem to serve similar functions, we hypothesized that egr-1 may also play a role in aging and stress response and could be another example of a gene that has a protective role during normal aging.

As egl-27, egr-1 contains a GATA DNA-binding domain and is homologous to mammalian MTA1 (Solari et al., 1999). MTA1 is a member of the NuRD chromatin remodeling complex, which has been shown to have nucleosome remodeling and histone deacetylase activity (Xue et al., 1998). As MTA1, EGR-1 has been shown to physically associate with other members of the NuRD complex (Passannante et al., 2010). Although both GATA transcription factors and chromatin state have been shown to play a role in aging and longevity in C. elegans (Budovskaya et al., 2008; Greer et al., 2010, 2011; Maures et al., 2011; Ni et al., 2012), the function of egr-1 in adult animals and during aging has not been fully characterized.

In this work, we show that increasing egr-1 levels extends lifespan and confers resistance to multiple stresses, while decreasing egr-1 levels suppresses the long lifespan of insulin signaling and germline mutants. As egl-27, expression of egr-1 increases with age, indicating that its role in normal aging is protective. This increase in expression is suppressed in germline-deficient mutants, suggesting that egr-1 may respond to signals from the germline. Finally, we show that egr-1 acts in the insulin signaling pathway, suggesting that it may have an important role in insulin signaling-mediated stress resistance and longevity.

Results

Decreasing and increasing levels of egr-1 have opposite effects on lifespan

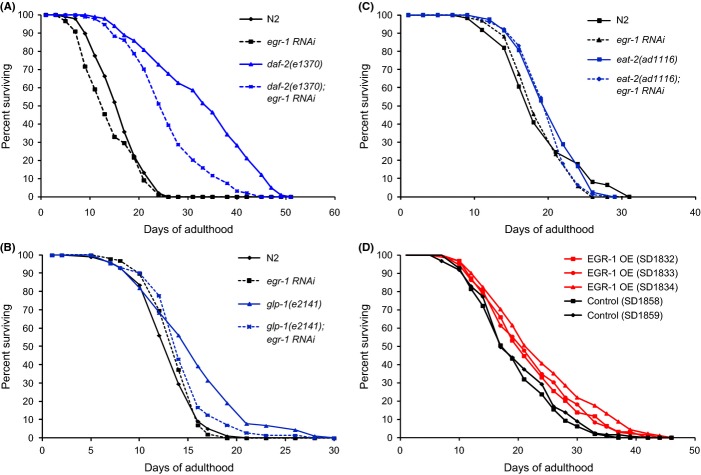

Previous research has shown that the GATA transcription factor/MTA-1 homolog egl-27 can extend lifespan and increase stress tolerance when overexpressed (Xu & Kim, 2012). During development, egl-27 function is partially redundant with the function of its paralog egr-1 (Solari et al., 1999), which suggests that egr-1 might also be a good candidate for being involved in aging and stress resistance. Knockdown of egr-1 by adult onset RNAi has been shown to partially suppress the extended lifespan of daf-2 mutants (Samuelson et al., 2007; Budovskaya et al., 2008). We confirmed this result that egr-1 RNAi reduced daf-2(e1370) lifespan by about 25% compared with an empty vector control in 2 replicates (p < 0.001 by log rank test in each replicate) (Fig. 1A, Table S1). Knockdown of egr-1 did not significantly affect wild-type lifespan, indicating that egr-1 is specifically required for the extended longevity of insulin signaling mutants and that egr-1 knockdown does not merely have a nonspecific effect on lifespan. To see whether egr-1 was also required for other longevity pathways, we tested whether egr-1 RNAi could suppress the extended longevity of glp-1(e2141) and eat-2(ad1116) mutants. egr-1 RNAi almost completely suppressed the extended lifespan of glp-1 mutants (p < 0.05 by log rank test) (Fig. 1B), but did not suppress the lifespan of eat-2 mutants (Fig. 1C). These results indicate that egr-1 may act downstream of the germline-dependent longevity pathway, but is dispensable for longevity induced by dietary restriction.

Figure 1.

egr-1 activity promotes lifespan. (A) egr-1 RNAi partially suppresses the extended lifespan of daf-2(e1370). Synchronized populations of worms were grown at 20°C and transferred to either egr-1 or control RNAi bacteria as day 1 adults. egr-1 RNAi significantly shortened the median lifespan of long-lived daf-2(e1370) animals by 28% (p < 0.001 by log rank test). egr-1 RNAi had no significant effect on N2 lifespan (p > 0.05 by log rank test). The x-axis indicates days of adulthood and the y-axis percentage of surviving animals. Shown is a representative lifespan of two experiments performed (Table S1). (B) egr-1 RNAi suppresses the extended lifespan of glp-2(e2141). Synchronized populations of worms were grown at 25°C and transferred to either egr-1 RNAi bacteria or empty vector control as day 1 adults. egr-1 RNAi significantly shortened the lifespan of long-lived glp-1(e2141) animals to nearly wild-type control levels (p < 0.05 by log rank test). egr-1 RNAi had no significant effect on N2 lifespan (p > 0.05 by log rank test). The x-axis indicates days of adulthood and the y-axis percentage of surviving animals. (C) egr-1 RNAi does not suppress the extended lifespan of eat-2(ad1116) mutants. Synchronized populations of worms were grown at 20°C and transferred to either egr-1 RNAi bacteria or empty vector control as day 1 adults. egr-1 RNAi had no significant effect on eat-2(ad1116) or N2 lifespan (p > 0.05 by log rank test). The x-axis indicates days of adulthood and the y-axis percentage of surviving animals. (D) Overexpression of the egr-1 gene extends lifespan 15–24% in three independent lines (p < 0.01 by log rank test). Transgenic animals were created by microinjection to form extrachromosomal arrays of the full-length egr-1 gene and the C. briggsae unc-119 gene in an unc-119(ed3) background. Control lines express only the unc-119+ transgene in an unc-119(ed3) background. Shown is a representative lifespan of four experiments performed (Table S1).

As low levels of egr-1 activity are detrimental to extended longevity, we next tested whether increased levels of egr-1 activity could extend lifespan. We created three transgenic lines that contain extra copies of the full-length egr-1 gene (strains SD1832, SD1833, and SD1834). To confirm that egr-1 was overexpressed in these lines, we used qRT–PCR to measure egr-1 RNA levels in synchronized young adult worms and found that the egr-1 transgenic lines had 1.8- to 3.1-fold increased levels of egr-1 compared with unc-119 rescue controls in young adults (Fig. S1). For each strain, we measured the lifespan four times compared with two unc-119 rescue controls (strains SD1858 and SD1859) and observed a 17-25% increase in lifespan (p < 0.05 by log rank test) (Fig. 1D, Table S1). The lifespan extension was significant in every assay for all three lines except for one of the four replicates of SD1833 (Table S1).

To test whether the lifespan extension observed in EGR-1 overexpression lines comes at a cost to fecundity, we measured the brood size of the three overexpression lines compared with the two unc-119 rescue controls. The brood size of one of the three overexpression lines (SD1832) was significantly reduced compared with controls (15% fewer progeny, p < 0.05); the brood sizes of the other two were not significantly different (Fig. S2).

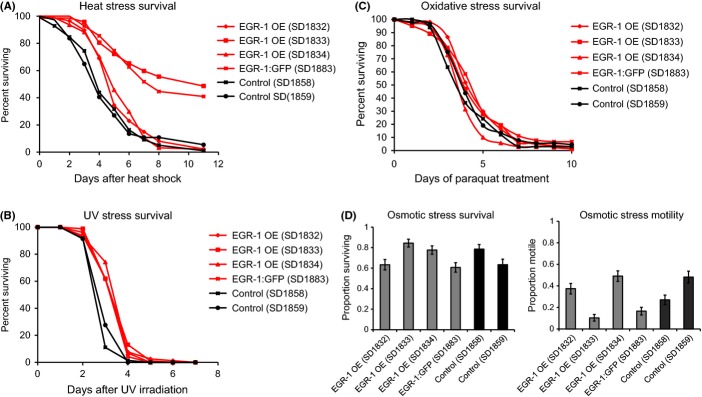

egr-1(+) promotes resistance to heat and UV stress, while egr-1(−) reduces resistance to oxidative and UV stress

Because aging is associated with an increase in certain types of stress and increased longevity is often correlated with increased stress resistance (Finkel & Holbrook, 2000; Johnson et al., 2000, 2001), we investigated whether egr-1 overexpression can confer stress protection as well as lifespan extension. Synchronized day 1 adult worms were exposed to heat stress (34°C for 8 h), UV irradiation (20 J m−2 and 30 J m−2), oxidative stress (10 mm paraquat), or osmotic stress (500 mm NaCl) and subsequent survival was measured. We found that egr-1 overexpression resulted in resistance to heat shock and UV irradiation, but not to oxidative or osmotic stress (Fig. 2, Table S2). egr-1 overexpression resulted in a 20–132% increase in survival of heat stress (p < 0.05 for all lines) (Fig. 2A) and a 28–33% increase in survival of UV irradiation (p < 0.01 for all lines) (Fig. 2B). The variability of heat stress resistance between the four transgenic lines does not correlate with the level of egr-1 RNA levels in young adults (Fig. S1), but could be due to background differences or differences in egr-1 levels in specific tissues.

Figure 2.

Overexpression of egr-1 confers resistance to heat and UV stress, but not oxidative or osmotic stress. (A) Overexpression of egr-1 increases survival after heat shock in four independent lines. Synchronized day 1 adult animals were heat-shocked at 34°C for 8 h and subsequent deaths were counted. Lines SD1833 and SD1883 show markedly increased survival: an increase of 132% and 91%, respectively, over the longer-lived control. The other two lines show survival increases of 20% and 27% (all lines p < 0.05 by log rank test). The x-axis indicates days after heat shock and the y-axis percent of animals surviving. (B) Overexpression of egr-1 increases survival 28–33% after UV irradiation in four independent lines (all lines p < 0.001 by log rank test). Synchronized day 1 adult animals were exposed to 20 J m−2 of ultraviolet light and subsequent deaths were counted. The x-axis indicates days after UV irradiation and the y-axis percent of animals surviving. (C) Overexpression of egr-1 does not increases survival to oxidative stress. Synchronized day 1 adult animals were transferred to NGM plates containing 10 mM paraquat and subsequent deaths were counted. The x-axis indicates days of paraquat exposure and the y-axis percent of animals surviving. (D) Overexpression of egr-1 does not increase survival (left) or motility (right) in osmotic stress conditions induced by 500 mm NaCl. For the survival assay, synchronized day 1 adult animals were transferred to NGM plates containing 500 mm NaCl for 24 h and then allowed to recover for 24 h on normal NGM plates (51 mm NaCl) for 24 h before deaths were counted. For the motility assay, day 1 adult worms were transferred to NGM plates containing 500 mM NaCl and motility was assessed after 1 h. The y-axis indicates percentage of worms surviving or motile.

To determine whether egr-1 is required for wild-type stress resistance, we next tested whether reduction in egr-1 expression reduced survival to heat stress (35°C for 8 h), UV irradiation (20 J m−2), and oxidative stress (10 mm paraquat). Knockdown of egr-1 by RNAi did not affect survival after heat stress (Fig. S3A), but did slightly reduce survival after oxidative stress (17%) and UV irradiation (7%) (p < 0.05 by log rank test for both conditions) (Fig. S3B-C).

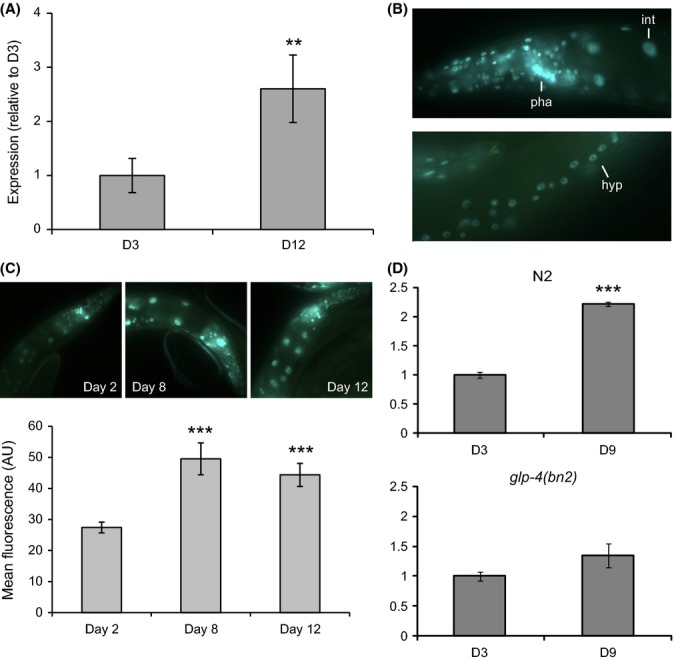

EGR-1 is broadly expressed and increases in expression with age

Next, we investigated changes in egr-1 expression during normal aging. Because high levels of egr-1 are beneficial for lifespan, a decrease in egr-1 expression with age would suggest that loss of egr-1 has a detrimental effect on lifespan, whereas an increase in expression would suggest that egr-1 has a protective role in the normal aging process. Using qRT–PCR to measure levels of egr-1 RNA in wild-type worms at day 3 and day 12 of adulthood, we found that egr-1 expression increases by approximately 2.5-fold with age (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

EGR-1 is broadly expressed and increases with age in a germline-dependent manner. (A) egr-1 RNA levels increase between day 3 and day 12 of adulthood by approximately 2.5-fold (**p < 0.01). Expression of egr-1 was measured by qRT–PCR and normalized to the expression of β-actin (act-1). The data are represented as fold-change relative to expression at day 3. Error bars equal ±SEM of three technical replicates. (B) EGR-1:GFP is broadly expressed in nearly all somatic cells of the day 1 adult animal. int = intestine; pha = pharynx; hyp = hypodermis. (C) The expression of EGR-1:GFP increases by approximately 2-fold between day 2 and day 12 (***p < 0.001). Top: representative fluorescent images of EGR-1:GFP worms at day 2, day 8, and day 12 of adulthood. Bottom: quantification of EGR-1:GFP expression in the intestine at day 2, day 8, and day 12 of adulthood. The EGR-1:GFP reporter strain contains a glo-4(ok623) mutation to facilitate imaging by decreasing gut autofluorescence. Data are represented as mean fluorescent intensity in arbitrary units; error bars are ±SEM. (D) egr-1 expression does not increase with age in glp-4 mutant animals. In wild-type (N2) worms (left), egr-1 RNA expression increases 2.2-fold between D3 and D9 (***p < 0.001), but does not change with age in glp-4(bn2) mutants (right) (p > 0.05). Worms were grown at 25°C, the restrictive temperature for glp-4 expression. Expression of egr-1 was measured by qRT–PCR and normalized to the expression of β-actin (act-1). Identical results were obtained by normalizing to β-tubulin (tbb-2). The data are represented as fold-change relative to expression at day 3. Error bars equal ±SEM of three technical replicates.

To determine whether an increase in egr-1 RNA leads to a corresponding increase in EGR-1 protein, we constructed an EGR-1 translational reporter with GFP fused to the C-terminus of egr-1 isoform b. Isoform b is the most highly expressed isoform (Hillier et al., 2009) and can fully rescue the lethal and sterile phenotypes of egr-1 mutants (Chen & Han, 2001). Transgenic worms carrying EGR-1:GFP show broad, nuclear-localized GFP expression in nearly all somatic cells in all larval stages and adults, as was previously observed (Solari et al., 1999; Chen & Han, 2001). In young adult worms, there is particularly strong expression in the intestine, pharynx, vulva, and hypodermal cells (Fig. 3B).

As GFP expression can be difficult to measure in old worms due to increasing background levels of gut autofluorescence, we created lines that express EGR-1:GFP in the glo-4(ok623) background. Worms carrying the glo-4(ok623) mutation lack lysosome-related gut granules and have markedly reduced background fluorescence in the intestine (Hermann et al., 2005). We measured EGR-1:GFP expression in these worms by quantifying GFP intensity from images taken of synchronized adult worms at day 2, day 8, and day 12. We found that EGR-1:GFP increased by nearly 2-fold with age (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3C). To confirm this observation in a wild-type background (without the glo-4 mutation), we measured the expression of EGR-1:GFP by immunofluorescence staining with an anti-GFP antibody. Using this method, we observed an approximately 2-fold increase in the fraction of GFP-positive intestinal nuclei between day 2 and day 12, confirming that EGR-1 protein levels increase with age in the intestine (p < 0.01) (Fig. S4). The observation that high levels of egr-1 promote longevity and that egr-1 RNA and protein levels increase with age suggests that the change in egr-1 expression late in life is not detrimental, but instead exerts protective effects.

egr-1 expression is not directly regulated by stress

One possible explanation for the observed age-upregulation of egr-1 is that it responds to increased levels of stress with old age. This seemed likely given that the paralog of egr-1, egl-27, has been found to increase expression in response to heat stress, oxidative stress, starvation, and UV irradiation (Xu & Kim, 2012). To examine whether stress affects egr-1 expression, we quantified levels of an EGR-1:GFP reporter in day 1 adult worms after exposure to varying doses and times of starvation, oxidative stress induced by paraquat, heat stress, osmotic stress induced by high salt, UV irradiation, and gamma irradiation. EGR-1:GFP expression did not increase in response to any of the stresses tested (Fig. S5A–F). One time point and dose of osmotic stress (500 mm NaCl for 4 h) did significantly decrease EGR-1:GFP expression (p < 0.05 after Bonferroni correction), but was not reflective of general trends. In addition, the magnitude of the change was relatively small (~30% decrease) compared with the increase in expression observed during aging (100% increase).

An additional source of stress during aging is pathogen stress induced by E. coli. E. coli is the common laboratory food for C. elegans, but is mildly pathogenic and shortens lifespan compared with a nonpathogenic food source such as Bacillus subtilis (Garsin et al., 2003; Sanchez-Blanco & Kim, 2011). To test whether exposure to E. coli pathogenicity leads to the observed increase in egr-1 expression, we compared EGR-1:GFP levels in young and old worms fed E. coli and B. subtilis. We observed no difference in absolute levels or the rate of increase of EGR-1:GFP in worms fed B. subtilis (Fig. S5G), indicating that E. coli pathogenicity does not drive the increase in EGR-1:GFP levels. Together, these results suggest that egr-1 expression is not directly increased by stress (unlike its paralog egl-27), and hence, stress does not appear to be the cause of the increased expression of egr-1 with age.

The increase in egr-1 expression is dependent on the presence of the germline

As none of the tested stress conditions could explain the increase in egr-1 expression with age, we looked to other aspects of normal aging that could drive changes in egr-1 expression. Reproductive aging and changes to the germline occur early in life (Luo & Murphy, 2011), and the absence of a germline can extend lifespan by signaling to somatic tissues (Arantes-Oliveira et al., 2002). To test whether egr-1 could respond to signals from the germline, we used qRT–PCR to measure egr-1 RNA levels in young and old wild-type and glp-4(bn2) animals grown at 25°C, the restrictive temperature for glp-4 expression. glp-4 mutants lack a germline and somatic gonad, but do not have an extended lifespan (TeKippe & Aballay, 2010). Similar to the results shown previously for worms grown at 20°C, egr-1 RNA expression increased 2.2-fold between day 3 and day 9 (p < 0.001). However, egr-1 did not increase in glp-4 mutants over the same time period (Fig. 3D). This result indicates that the increase in egr-1 expression is dependent on the presence of a germline and may be responding to signals from the germline to the soma.

egr-1 acts downstream of daf-2 in the insulin signaling pathway

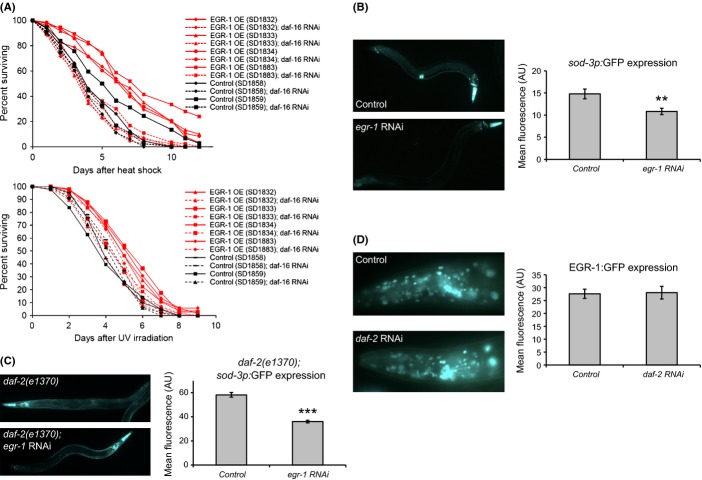

Several observations suggest that egr-1 may interact with the insulin signaling pathway. First, both egr-1 and the insulin signaling pathway mediate stress resistance and lifespan (Kenyon, 2005, 2010). Second, knockdown of egr-1 activity can suppress the longevity phenotype of daf-2 mutations, suggesting that egr-1 may act downstream of the daf-2 insulin receptor gene in the insulin signaling pathway. In the insulin signaling pathway, inactivation of the DAF-2 insulin receptor results in activation of the DAF-16/FOXO transcription factor, inducing downstream genes involved in stress resistance and longevity extension (Kenyon, 2010). We first asked whether the stress resistance phenotype of egr-1 overexpression mutants is dependent on DAF-16 activity. Reduction in daf-16 expression by RNAi in egr-1 overexpression mutants completely abolished their increased resistance to heat stress and partially or completely suppressed their resistance to UV stress (Fig. 4A). This suggests that egr-1 acts upstream of DAF-16 and that at least in the case of stress resistance, the benefits conferred by high levels of egr-1 require DAF-16.

Figure 4.

EGR-1 acts in the insulin signaling pathway. (A) Loss of DAF-16 completely suppresses the increased thermotolerance of EGR-1 overexpression worms (top) and partially or completely suppresses the increased UV irradiation of EGR-1 overexpression worms (bottom). EGR-1 overexpression and control worms were placed on daf-16 RNAi or empty vector control RNAi as L4s. One day later, day 1 adult animals were heat-shocked at 34°C for 8 hrs or irradiated at 20 J m−2 and subsequent deaths were counted. The x-axis indicates days poststress and the y-axis percent of animals surviving. (B–C) Worms expressing sod-3p:GFP (B) or sod-3p:GFP and daf-2(e1370) (C) were placed on either egr-1 RNAi or empty vector control RNAi as eggs and imaged 3 days later as day 1 adults. egr-1 RNAi decreased expression of sod-3 by 27% in a wild-type background (**p < 0.01), and by 40% in a daf-2(1370) background (***p < 0.001). Representative images are shown on the left, and mean GFP intensity in arbitrary units is shown on the right; error bars are ±SEM. (D) Worms expressing EGR-1:GFP in the glo-4(ok623) background were placed on either daf-2 RNAi or empty vector control RNAi as eggs and imaged 3 days later as day 1 adults. There was no significant difference in EGR-1 expression between the two groups.

To further characterize the role of egr-1 in insulin signaling, we next tested whether reduced levels of egr-1 affect DAF-16 activity. When DAF-16 is activated, it turns on a large number of genes including its well-established target sod-3 (Honda & Honda, 1999; Murphy et al., 2003; Oh et al., 2006). The expression of a sod-3 reporter can be used to measure activation of DAF-16; that is, high levels of sod-3 suggests high levels of DAF-16 activity and low levels of sod-3 suggest low levels of DAF-16 activity (Libina et al., 2003; Sanchez-Blanco & Kim, 2011). We tested whether sod-3 activation by DAF-16 is dependent on egr-1 in a wild-type background (in which DAF-16 activity is low) and in a daf-2(e1370) mutant background (in which DAF-16 activity is high) (Lin et al., 2001). We measured the effect of egr-1 RNAi on the expression of a sod-3:GFP transcriptional reporter in day 1 adult worms. In the wild-type background, we found that knockdown of egr-1 reduced levels of sod-3 by approximately 27% (p < 0.01) (Fig. 4B). In a daf-2(e1370) background, egr-1 RNAi results in a 40% decrease in sod-3 expression (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that egr-1 acts as part of the insulin signaling pathway downstream of daf-2 and is necessary for the proper regulation of sod-3.

Finally, we examined whether the insulin signaling pathway could regulate the expression of egr-1. We quantified the expression of an EGR-1:GFP reporter in day 1 adult worms grown on either daf-2 or control RNAi and found that daf-2 knockdown had no effect on EGR-1:GFP expression compared with control (Fig. 4D). To control for ineffective knockdown of daf-2 by RNAi, we showed that RNAi of daf-2 caused a dramatic increase in expression of sod-3 levels, as had been previously shown (Fig S6, (Libina et al., 2003; Sanchez-Blanco & Kim, 2011)). This suggests that although egr-1 acts downstream of daf-2 to affect lifespan and stress, its expression is not regulated by daf-2.

egr-1 regulates expression of egl-27

Because egr-1 and its paralog egl-27 both encode GATA transcription factors with homology to mammalian NuRD proteins, and because they have redundant genetic functions, it is possible that they regulate each other’s expression to ensure that the combined expression from both genes is at an appropriate level.

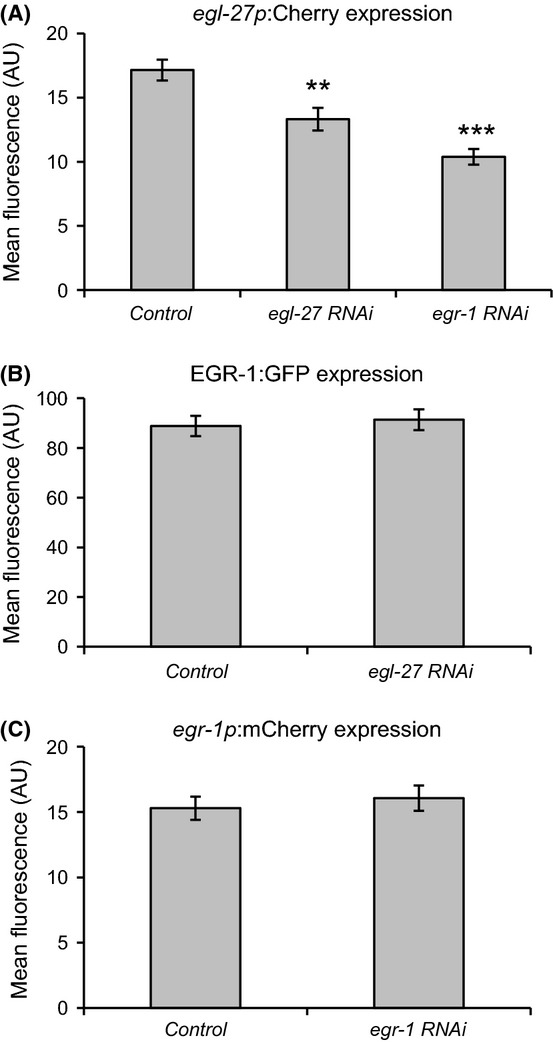

We first asked whether egr-1 could regulate the expression of egl-27. To test this possibility, we compared the expression of an egl-27:mCherry transcriptional reporter in egr-1 RNAi and control worms. We found that egr-1 RNAi reduced the expression of egl-27:mCherry by 40% (p < 0.001), indicating that egr-1 activates egl-27 expression (Fig. 5A). Next, we asked whether egl-27 could regulate egr-1 expression. To test this, we compared expression of an EGR-1:GFP translational reporter in worms fed egl-27 RNAi and control worms. We found that reduction in egl-27 activity had no effect on EGR-1:GFP levels (Fig. 5B). This result is unlikely to be due to ineffective knockdown of egl-27 by RNAi because we showed that egl-27 RNAi reduces the expression of its own transcriptional reporter by 22% (p < 0.01), as had been observed previously (Fig. 5A, (Xu & Kim, 2012)). These results indicate that egl-27 does not regulate egr-1 expression.

Figure 5.

EGR-1 activates egl-27 expression, but neither egl-27 nor egr-1 regulate egr-1 expression. (A) Worms expressing egl-27pro:mCherry were placed on egr-1 RNAi, egl-27 RNAi, or empty vector control RNAi as eggs and imaged 3 days later as day 1 adults. egl-27 RNAi decreased egl-27 promoter activity by 22% (**p < 0.01), and egr-1 RNAi decreased egl-27 promoter activity by 40% (***p < 0.001). All data are represented as mean fluorescence intensity in arbitrary units; error bars are ±SEM. (B) Worms expressing EGR-1:GFP in the glo-4(ok623) background were placed on either egl-27 RNAi or empty vector control RNAi as eggs and imaged 3 days later as day 1 adults. There was no significant difference in EGR-1 expression in either group. (C) Worms expressing egr-1pro:mCherry were placed on either egr-1 RNAi or empty vector control RNAi as eggs and imaged 3 days later as day 1 adults. There was no significant difference in egr-1 expression in either group.

Because egl-27 auto-activates its own expression, we wondered whether the same was true for egr-1. To test this, we measured the expression of an egr-1:mCherry transcriptional reporter in worms fed egr-1 RNAi. We found that egr-1 reporter expression was unchanged with loss of egr-1 (Fig. 5C). To control for the possibility of ineffective knockdown of egr-1 by RNAi, we measured the expression of the EGR-1:GFP translational reporter in worms fed egr-1 RNAi and saw dramatically decreased expression (Fig. S6). These results indicate that egr-1 does not autoregulate.

Histone H3 acetylation increases with age, but is not affected by egr-1 RNAi or overexpression

EGR-1 contains both a GATA DNA-binding domain and homology to MTA1, a member of the NuRD chromatin remodeling/histone deacetylase complex. To investigate whether egr-1 is capable of modifying chromatin, we examined the levels of H3K9 acetylation in wild-type, egr-1 RNAi and egr-1 overexpression lines by Western blot of whole worm protein lysates. Neither egr-1 RNAi nor egr-1 overexpression measurably affected acetylation at this locus (Fig. S7A). This result suggests that the function of the egr-1(+) in lifespan extension and stress resistance may not involve chromatin modification via the NuRD complex but possibly transcriptional regulation via the GATA DNA-binding domain.

During normal aging, we found that H3K9 acetylation increases approximately 20% between young (day 4) and old (day 14) wild-type animals (Fig. S7B). This increase in H3K9 acetylation is unlikely to be caused by EGR-1. First, EGR-1 increases with age and is part of the NuRD deactylation complex, suggesting that increased EGR-1 levels would be expected to decrease rather than increase H3K9 acetylation in old age. Second, the previous experiments show that neither increased nor decreased levels of EGR-1 activity results in a change in H3K9 acetylation levels.

Discussion

In this work, we have identified the GATA transcription factor/MTA1 homolog egr-1 as a regulator of longevity and stress response. We show that low levels of egr-1 suppress the extended lifespan of insulin signaling and germline mutants and reduce resistance to certain stresses, and that increased levels of egr-1 extend lifespan and confer resistance to stress. Furthermore, egr-1 RNA and protein levels increase in expression with age. Thus, egr-1 is an example of a gene that changes expression in a direction that is beneficial for the lifespan of the organism. This suggests that not all of the changes that occur with age are detrimental and that an old animal is not merely a degenerated version of a young animal.

Unlike the age-related change in egr-1 levels, many previously characterized changes in old age are detrimental to survival. For example, in C. elegans, the GATA transcription factor elt-3 decreases in expression with age and has a negative effect on survival, suggesting that this decrease may drive the aging process (Budovskaya et al., 2008). Although few positive age-dependent changes have been previously reported, the paralog of egr-1, egl-27, is another factor that increases with age and is pro-survival (Xu & Kim, 2012). These two genes may be part of a common longevity-promoting program that increases with age and can partially compensate for the negative changes that drive the aging process.

What drives the increase in EGR-1 expression with age? One possibility is that the increase could be driven by extrinsic or environmental factors, such as increasing stress, molecular damage, or pathogen load. However, we were unable to recapitulate the change in EGR-1 expression seen with age by exposure to several types of stresses or damaging agents. In addition, EGR-1 expression increased at the same rate when pathogen load was decreased by feeding a nonpathogenic food source. However, the increase in egr-1 expression is fully suppressed in animals lacking a germline and somatic gonad. This suggests that that change in egr-1 expression may be due to intrinsic signals from the aging reproductive system. It is known that the germline and somatic reproductive system can signal to the rest of the soma to regulate lifespan through steroid hormones and the insulin signaling pathway (Hsin & Kenyon, 1999; Arantes-Oliveira et al., 2002; Yamawaki et al., 2010), and it is possible that EGR-1 is responding to these signals. As reproductive aging occurs relatively early in the worm lifespan (Luo & Murphy, 2011), it is likely that changes in signals from the germline represent an early molecular event in aging and could cause changes in many downstream genes in the soma. The fact that loss of egr-1 fully suppresses the longevity of germlineless mutants adds further evidence that egr-1 acts downstream of the germline to promote longevity.

If increased levels of egr-1 in old age are beneficial for lifespan and stress resistance, a question arises regarding why young animals do not also express high egr-1 levels. One possibility is that high egr-1 expression reduces reproductive fitness. However, we only observed a significant reduction in brood size in one of three overexpression lines and the magnitude of the effect was relatively small, suggesting that progeny production is not substantially limited in EGR-1 overexpression lines. Nevertheless, it is certainly possible that a small reduction in brood size could have an effect on fitness or that EGR-1 overexpression lines have fitness defects that we have not detected.

In addition to promoting longevity, egr-1 overexpression increases thermotolerance and resistance to UV stress. Many mutations that extend lifespan also increase tolerance to multiple stresses (Johnson et al., 2000, 2001), and egr-1 may be part of this common program that promotes both longevity and response to stress. Although the expression of egr-1 itself is not induced upon exposure to stress, it is possible that EGR-1 activity increases in stress conditions or that its presence at baseline level is necessary for the induction of downstream stress response genes. This is supported by the observation that knockdown of egr-1 reduces wild-type tolerance to UV and oxidative stress. In addition, egr-1 was identified in a screen of genes necessary for the induction of cytoprotective pathways (Shore et al., 2012) and was found to be required to protect cells from ionizing radiation (van Haaften et al., 2006). Both of these results indicate that egr-1 may be an important component of the normal stress response.

In mammalian cells, components of the NuRD complex are lost in both progeria and during normal aging, leading to chromatin defects that are thought to be detrimental to survival (Pegoraro et al., 2009). This is consistent with a conserved role for the NuRD complex in promoting lifespan, by decreasing in expression and causing aging in mammals and increasing in expression and increasing lifespan in C. elegans. Recently, another member of the C. elegans NuRD complex (let-418/Mi-2) has been shown to have a dual role in longevity and stress resistance (De Vaux et al., 2013). Knockdown of let-418 increases longevity and stress resistance (opposite to egr-1), while also shortening the long lifespan of insulin signaling mutants (same role as egr-1).

EGR-1’s biochemical role as a member of the NuRD complex remains unclear. We were unable to detect changes in H3 acetylation when egr-1 levels were perturbed, but this may be due to a lack of sensitivity in our assay or the fact that the NuRD complex may have stronger effects at other chromatin sites. It is also possible that EGR-1 acts predominantly as a GATA transcription factor and is largely independent of the NuRD complex.

In addition, we found that H3K9 acetylation levels increase with age in C. elegans. H3K9 acetylation is associated with active chromatin. This result is consistent with previous findings that H3K27 trimethylation, a repressive mark, decreases with age (Maures et al., 2011). The chromatin acetylation and methylation results together suggest that aging is associated with a general opening of chromatin. A general loss of repressive chromatin and increase in active chromatin with age have also been seen in mouse brain and are associated with aberrant de-repression of genes (Shen et al., 2008). In addition, several methyltransferases and demethylases regulate lifespan in C. elegans (Greer et al., 2010; Maures et al., 2011), and recently, the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex was found to bind with DAF-16 to regulate stress resistance and longevity (Riedel et al., 2013).

The mechanism whereby egr-1 and egl-27 increase stress resistance and longevity appears to involve the insulin signaling pathway, as mutations in either egr-1 or egl-27 can suppress the longevity of daf-2 insulin receptor mutants. Reduction in insulin signaling by mutations in daf-2 results in activation of the DAF-16 FOXO transcription factor, which induces the expression of many genes that promote stress resistance and longevity (Kenyon, 2010). We found that egr-1 acts downstream of daf-2 and that DAF-16 activity is required for the stress resistance phenotype of egr-1 overexpression mutants. In addition, egr-1 is necessary for the proper regulation of the canonical DAF-16 target sod-3. These data suggest that egr-1 may increase longevity by contributing to the health- and lifespan-promoting program activated by DAF-16.

egr-1 and egl-27 encode highly similar proteins with homology to GATA transcription factors and NuRD chromatin remodeling proteins. egr-1 activates the expression of its paralog egl-27, which has also been shown to increase stress tolerance and lifespan downstream of the insulin signaling pathway. These experiments predict that a long-lived egr-1 overexpression line would also have higher levels of egl-27. As high levels of egl-27 have been shown to be beneficial for lifespan, this could contribute to the longevity and stress resistance phenotype observed in egr-1 overexpression mutants.

Expression of egl-27 is controlled both by egl-27 itself and by egr-1, but egr-1 expression is not regulated by either itself or egl-27. Transcriptional profiling experiments indicate that egr-1 RNA levels are more than 20-fold higher than egl-27 RNA levels in young worms (Van Nostrand et al., 2013). These observations suggest that the shared activity of egr-1 and egl-27 is comprised mostly by egr-1 and that there is fine-tuning of the level of shared activity by feedback control of egl-27.

Although egr-1 and egl-27 share common functions, they are not entirely redundant. First, although both genes promote stress resistance, egl-27 promotes resistance to heat and oxidative stress, while egr-1 extends lifespan in response to heat and UV stress, but not oxidative stress. Second, egl-27 expression is directly induced by stress while it appears that at least in comparable experiments, EGR-1 expression is not. A previous study found that EGR-1 physically associates with other NuRD complex members but that EGL-27 does not (Passannante et al., 2010), which may explain some of their differences in function.

In summary, we have identified egr-1 as an example of a gene that has protective effects on lifespan and stress resistance during normal aging. In the future, it will be interesting to determine whether the bulk of changes seen during aging are in fact detrimental, or whether a substantial portion promote survival, as does the change in egr-1 expression. If so, extending lifespan may not be a simple matter of resetting the transcriptome to a more youthful state, but may require a careful balancing that removes the negative changes while preserving the natural protective changes in old age.

Experimental procedures

Strains

All C. elegans strains were handled and maintained as described previously (Brenner, 1974). EGR-1 overexpression strains were generated by microinjection of the full-length egr-1 gene and the C. briggsae unc-119 gene into the unc-119(ed3) background to form lines carrying the transgenes as an extrachromosomal array. Control strains were generated by microinjection of the Cbr unc-119 plasmid alone.

The EGR-1:GFP reporter construct was generated by inserting eGFP into the C-terminus of egr-1 isoform b by recombineering (Sarov et al., 2006). Transgenic worms were produced by microinjection of the resulting plasmid into the unc-119(ed3) background and the unc-119(ed3) and glo-4(ok623) background.

All experiments utilizing strains carrying daf-2(e1370) were carried out at 20°C. Experiments using the temperature sensitive germline mutants glp-1(e2141) and glp-4(bn2) were carried out at 25°C. A full list of all strains used in this study can be found in Table S3.

RNAi

All RNAi experiments were carried out on NGM plates supplemented with 100 ug mL−1 ampicillin and 1 mm IPTG (2 mm IPTG if using FUDR). Plates were seeded with 10× concentrated overnight cultures E. coli expressing the appropriate RNAi clone or control. All RNAi clones were obtained from the Ahringer RNAi library (Kamath et al., 2003) and sequenced to verify proper insertions. HT115 bacteria carrying an empty vector were used as a control. The egr-1 RNAi clone used (forward primer - TCTCATTGAAATCCTTGCCC; reverse primer - CTGATGACGTGGCAGAGAAA) was determined to be unlikely to significantly cross-react with egl-27 by comparing the targeting region and the region upstream of the targeting region with the egl-27 genomic sequence using the BLAT alignment tool (Kent, 2002). The egr-1 RNAi clone is unlikely to target egl-27 directly, as there are no shared regions of 22 nt or more between egr-1 and egl-27.

Analysis of lifespan

Lifespan assays were performed as previously described (Kenyon et al., 1993). Unless otherwise noted, all lifespan experiments were performed at 20°C and on NGM plates supplemented with 30 mm 5-fluoro-2’-deoxyuridine (FUDR) to inhibit progeny production. Animals that died due to internal progeny hatching were censored. Animals were scored as dead if they failed to respond to repeated prodding by a pick. Lifespan experiments using RNAi knockdown were performed on NGM plates supplemented with 30 um FUDR, 100 ug mL−1 ampicillin, and 2 mm IPTG. Significance of lifespan experiments was determined using the log rank test (Lawless, 1982).

Brood size experiment

Five unmated L4 hermaphrodite worms were placed on NGM plates and transferred to new plates every 24 h until day 4 of adulthood. Progeny were counted 24 h after the parental generation had been moved off the plate. Total brood size was calculated as the sum of the progeny produced on each of the first 4 days of adulthood per worm.

Quantitative RT–PCR

Wild type (N2), egr-1 overexpression strains, and unc-119 rescue control strains were synchronized using hypochlorite to extract eggs. Day 1 adult worms were transferred to NGM plates containing 30 mm FUDR until day 3 and day 12. For the comparison with glp-4(bn2), adult worms were grown on NGM plates containing 30 mm FUDR until day 3 and day 9 at 25°C. Total RNA was isolated from approximately 100 worms per condition using Trizol reagent and phenol-chloroform extraction. cDNA was synthesized using oligo dT primers and SuperScript II First Strand Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The cDNA and primers were tested using standard PCR and gel electrophoresis to ensure that the PCR resulted in a single product. qPCRs were performed using RT2SYBR Green qPCR Mastermix (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Each primer pair was serially diluted to generate a standard curve, and egr-1 expression values were normalized to the expression of β-actin (act-1) as an internal control. For the glp-4(bn2) experiment, β-tubulin (tbb-2) was also used as a normalization control. Each qPCR was performed in technical triplicate.

Imaging and quantification of expression

For all imaging studies, synchronized adult worms were immobilized on slides with 1 mm levamisole and imaged on a Zeiss Axioplan fluorescent microscope. All conditions being compared were imaged on the same day using the same microscope and image capture settings. Fluorescent intensities were quantified using ImageJ (Abramoff et al., 2004). At least 20 worms were measured for each condition.

For imaging studies using RNAi, worms carrying the relevant fluorescent reporter were synchronized using hypochlorite to extract eggs. Eggs were placed on NGM plates supplemented with ampicillin and IPTG that had been seeded with the appropriate RNAi clone as above. The resulting larvae were grown for 3 days on RNAi until day 1 of adulthood before imaging.

Immunofluorescence

Synchronized day 2, day 8, and day 12 adult worms expressing EGR-1:GFP were fixed and stained according to the modified Finney-Ruvkun protocol described by Bettinger et al. (1996). Formaldehyde-fixed worms were incubated in chicken anti-GFP primary antibody (ab13970; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) diluted 1:2000 overnight at 4°C, and Alexa-Fluor 555 goat anti-chicken secondary antibody (Invitrogen) diluted 1:200 for 2 h at room temperature. Fixed and antibody-stained worms were mounted using Vectashield Hard Set Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vector) to label nuclei. Slides were imaged on a Zeiss Axioplan fluorescent microscope. All three time points were fixed, antibody-stained, and imaged in parallel. The percent of EGR-1:GFP-positive intestinal nuclei was quantified by dividing the number of visible fluorescent nuclei (GFP+) by the total number of DAPI stained intestinal nuclei. At least 20 worms were measured per time point.

Stress resistance assays

All assays were performed using synchronized day 1 adult animals. Unless otherwise specified, all experiments were carried out at 20°C. Deaths were scored daily as for lifespan assays above. For the egr-1 RNAi experiments, worms were picked to egr-1 or empty vector control RNAi plates at L4 and exposed to stress 1 day later as day 1 adults and then maintained on RNAi plates until the end of the experiment.

Heat stress

Worms were incubated at 34°C for 8 h as described by Lithgow et al. (1995) and then returned to 20°C. For the DAF-16 epistasis experiment, worms were picked to daf-16 or empty vector control RNAi plates as L4s and heat-shocked 1 day later as day 1 adults.

UV stress

Worms were transferred to unseeded plates and irradiated with 20 or 30 J m−2 UV using a UV Stratalinker (Stratagene) as described previously (Murakami & Johnson, 1996) and then moved back to seeded plates.

Oxidative stress

Worms were transferred to NGM plates containing 10 mm paraquat and 30 mm FUDR to prevent internal hatching of progeny, as described by Xu and Kim (2012). Plates were seeded with 10× concentrated overnight cultures of E. coli.

Osmotic stress

Worms were transferred to NGM plates containing 500 mm NaCl for 24 h and then allowed to recover for 24 h on normal NGM plates (51 mm NaCl) for 24 h before deaths were counted, as described by Solomon et al. (2004). For the motility assay, day 1 adult worms were transferred to NGM plates containing 500 mm NaCl, and motility was assessed after 1 h.

Stress expression assays

All assays were performed using synchronized day 1 adult animals. Control worms were transferred to new plates at the same time as experimental worms, and both control and experimental worms were imaged together at each time point. Unless otherwise specified, all experiments were carried out at 20°C.

Starvation

Worms were transferred to unseeded plates and imaged after 2 h, 4 h, and 24 h.

Oxidative stress

Worms were transferred to NGM plates containing 10 mm paraquat and imaged after 1 h, 5 h, and 24 h.

Heat stress

Worms were heat-shocked at 34°C for 90 min and then allowed to recover at 20°C for 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, and 24 h before imaging.

Osmotic stress

Worms were transferred to NGM plates containing 200, 300, or 500 mm NaCl and imaged after 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, and 24 h. Control worms were maintained on standard NGM plates (51 mm NaCl).

UV and gamma irradiation

Worms were transferred to unseeded plates and irradiated with 30 J m−2 UV using a UV Stratalinker (Stratagene) or a 137Cs source at 40 Gy as described previously (Budovskaya et al., 2008) and then moved back to seeded plates and allowed to recover for 1 h, 5 h, and 24 h before imaging. Control worms were transferred to unseeded and back to seeded plates at the same time as irradiated worms.

B. subtilis

Overnight cultures of B. subtilis strain PY79 and E. coli strain OP50 were seeded on NGM plates supplemented with 30 mm FUDR, as described by Sanchez-Blanco and Kim (2011). Day 1 adult worms were transferred onto freshly seeded plates and maintained there until day 2 and day 12, when they were imaged. Worms were moved to new freshly seeded plates every 2–3 days to prevent the formation of B. subtilis spores.

Western blots

Total protein from synchronized L4, young, or old adult worms of the appropriate genotype was collected by lysing approximately 120 worms in Laemmli sample buffer (SDS, 2.36%; glycerol, 9.43%; b-mercaptoethanol, 5%; Tris pH 6.8, 0.0945 m; bromophenol blue, 0.001%). Samples were boiled for 10 min at 95°C before being resolved on a 10% Novex Tricine SDS-PAGE gel (Invitrogen) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were incubated with anti-acetyl-Histone H3 (Lys9) (07–352, 1:5000 dilution; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) or anti-H3 (ab1791, 1:2000 dilution; Abcam) at 4°C overnight. Primary antibodies were visualized using an HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (#7071, 1:2000 dilution; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) and the Phototope-HRP Western blot detection system (Cell Signaling). Western blots were quantified using ImageJ (Abramoff et al., 2004). Background-subtracted H3K9 acetylation levels were normalized to background-subtracted H3 levels for all conditions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Xiao Xu for advice and assistance with the stress assays and help generating the EGR-1:GFP construct; Dror Sagi for assistance with the B. subtilis experiment; Lena Budovskaya and Cindie Slightam for generating the egr-1pro:Cherry transgenic worms; Travis Maures, Shuo Han, and Anne Brunet for providing strains and antibodies; Lisl Esherick for assistance with Western blots; and all the members of the Kim laboratory for advice and critical reading of the manuscript. Some strains used in this work were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

Author contributions

SMZ and SKK designed the experiments; SMZ performed the experiments and analyzed the data; SMZ and SKK wrote the article.

Funding

SMZ is supported by the NSF GRFP and the Smith Stanford Graduate Fellowship. Research in the laboratory of SKK is supported by the National Institutes of Health R01AGO25941.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site.

Fig. S1 egr-1 RNA is overexpressed in egr-1 overexpression lines, and increases with age in all genotypes.

Fig. S2 Brood size of EGR-1 overexpression lines.

Fig. S3 egr-1 RNAi reduces resistance to oxidative and UV stress, but not heat stress.

Fig. S4 EGR-1:GFP protein increases with age by immunofluorescence staining.

Fig. S5 EGR-1 expression is not induced in response to stress.

Fig. S6 RNAi controls.

Fig. S7 Changes in H3K9 acetylation by knockdown or overexpression of egr-1, and during aging.

Table S1 Additional lifespan data.

Table S2 Additional stress resistance data.

Table S3 Strains used in this study.

References

- Abramoff MD, Magalhaes PJ, Ram SJ. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics Int. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Arantes-Oliveira N, Apfeld J, Dillin A, Kenyon C. Regulation of life-span by germ-line stem cells in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2002;295:502–505. doi: 10.1126/science.1065768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettinger JC, Lee K, Rougvie AE. Stage-specific accumulation of the terminal differentiation factor LIN-29 during Caenorhabditis elegans development. Development. 1996;122:2517–2527. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.8.2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budovskaya YV, Wu K, Southworth LK, Jiang M, Tedesco P, Johnson TE, Kim SK. An elt-3/elt-5/elt-6 GATA transcription circuit guides aging in C. elegans. Cell. 2008;134:291–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Han M. Role of C. elegans lin-40 MTA in vulval fate specification and morphogenesis. Development. 2001;128:4911–4921. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.23.4911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vaux V, Pfefferli C, Passannante M, Belhaj K, von Essen A, Sprecher SG, Muller F, Wicky C. The Caenorhabditis elegans LET-418/Mi2 plays a conserved role in lifespan regulation. Aging Cell. 2013;12:1012–1020. doi: 10.1111/acel.12129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408:239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garsin DA, Villanueva JM, Begun J, Kim DH, Sifri CD, Calderwood SB, Ruvkun G, Ausubel FM. Long-lived C. elegans daf-2 mutants are resistant to bacterial pathogens. Science. 2003;300:1921. doi: 10.1126/science.1080147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden TR, Melov S. Microarray analysis of gene expression with age in individual nematodes. Aging Cell. 2004;3:111–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2004.00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden TR, Hubbard A, Dando C, Herren MA, Melov S. Age-related behaviors have distinct transcriptional profiles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2008;7:850–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00433.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer EL, Maures TJ, Hauswirth AG, Green EM, Leeman DS, Maro GS, Han S, Banko MR, Gozani O, Brunet A. Members of the H3K4 trimethylation complex regulate lifespan in a germline-dependent manner in C. elegans. Nature. 2010;466:383–387. doi: 10.1038/nature09195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer EL, Maures TJ, Ucar D, Hauswirth AG, Mancini E, Lim JP, Benayoun BA, Shi Y, Brunet A. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2011;479:365–371. doi: 10.1038/nature10572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Haaften G, Romeijn R, Pothof J, Koole W, Mullenders LH, Pastink A, Plasterk RH, Tijsterman M. Identification of conserved pathways of DNA-damage response and radiation protection by genome-wide RNAi. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:1344–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann GJ, Schroeder LK, Hieb CA, Kershner AM, Rabbitts BM, Fonarev P, Grant BD, Priess JR. Genetic analysis of lysosomal trafficking in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:3273–3288. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herndon LA, Schmeissner PJ, Dudaronek JM, Brown PA, Listner KM, Sakano Y, Paupard MC, Hall DH, Driscoll M. Stochastic and genetic factors influence tissue-specific decline in ageing C. elegans. Nature. 2002;419:808–814. doi: 10.1038/nature01135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier LW, Reinke V, Green P, Hirst M, Marra MA, Waterston RH. Massively parallel sequencing of the polyadenylated transcriptome of C. elegans. Genome Res. 2009;19:657–666. doi: 10.1101/gr.088112.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda Y, Honda S. The daf-2 gene ne for longevity regulates oxidative stress resistance and Mn-superoxide dismutase gene expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. FASEB J. 1999;13:1385–1393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsin H, Kenyon C. Signals from the reproductive system regulate the lifespan of C. elegans. Nature. 1999;399:362–366. doi: 10.1038/20694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Xiong C, Kornfeld K. Measurements of age-related changes of physiological processes that predict lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:8084–8089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400848101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TE, Cypser J, de Castro E, de Castro S, Henderson S, Murakami S, Rikke B, Tedesco P, Link C. Gerontogenes mediate health and longevity in nematodes through increasing resistance to environmental toxins and stressors. Exp. Gerontol. 2000;35:687–694. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TE, de Castro E, Hegi de Castro S, Cypser J, Henderson S, Tedesco P. Relationship between increased longevity and stress resistance as assessed through gerontogene mutations in Caenorhabditis elegans. Exp. Gerontol. 2001;36:1609–1617. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(01)00144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath RS, Fraser AG, Dong Y, Poulin G, Durbin R, Gotta M, Kanapin A, Le Bot N, Moreno S, Sohrmann M, Welchman DP, Zipperlen P, Ahringer J. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature. 2003;421:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nature01278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ. BLAT–the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12:656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon C. The plasticity of aging: insights from long-lived mutants. Cell. 2005;120:449–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon CJ. The genetics of ageing. Nature. 2010;464:504–512. doi: 10.1038/nature08980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon C, Chang J, Gensch E, Rudner A, Tabtiang R. A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature. 1993;366:461–464. doi: 10.1038/366461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawless JF. Statistical Models and Methods for Lifetime Data. New York: Wiley; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Libina N, Berman JR, Kenyon C. Tissue-specific activities of C. elegans DAF-16 in the regulation of lifespan. Cell. 2003;115:489–502. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00889-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin K, Hsin H, Libina N, Kenyon C. Regulation of the Caenorhabditis elegans longevity protein DAF-16 by insulin/IGF-1 and germline signaling. Nat. Genet. 2001;28:139–145. doi: 10.1038/88850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lithgow GJ, White TM, Melov S, Johnson TE. Thermotolerance and extended life-span conferred by single-gene mutations and induced by thermal stress. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:7540–7544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund J, Tedesco P, Duke K, Wang J, Kim SK, Johnson TE. Transcriptional profile of aging in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:1566–1573. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S, Murphy CT. Caenorhabditis elegans reproductive aging: regulation and underlying mechanisms. Genesis. 2011;49:53–65. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maures TJ, Greer EL, Hauswirth AG, Brunet A. The H3K27 demethylase UTX-1 regulates C. elegans lifespan in a germline-independent, insulin-dependent manner. Aging Cell. 2011;10:980–990. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00738.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee MD, Weber D, Day N, Vitelli C, Crippen D, Herndon LA, Hall DH, Melov S. Loss of intestinal nuclei and intestinal integrity in aging C. elegans. Aging Cell. 2011;10:699–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00713.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami S, Johnson TE. A genetic pathway conferring life extension and resistance to UV stress in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1996;143:1207–1218. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.3.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CT, McCarroll SA, Bargmann CI, Fraser A, Kamath RS, Ahringer J, Li H, Kenyon C. Genes that act downstream of DAF-16 to influence the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2003;424:277–283. doi: 10.1038/nature01789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Z, Ebata A, Alipanahiramandi E, Lee SS. Two SET domain containing genes link epigenetic changes and aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2012;11:315–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00785.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SW, Mukhopadhyay A, Dixit BL, Raha T, Green MR, Tissenbaum HA. Identification of direct DAF-16 targets controlling longevity, metabolism and diapause by chromatin immunoprecipitation. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:251–257. doi: 10.1038/ng1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passannante M, Marti CO, Pfefferli C, Moroni PS, Kaeser-Pebernard S, Puoti A, Hunziker P, Wicky C, Muller F. Different Mi-2 complexes for various developmental functions in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e13681. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegoraro G, Kubben N, Wickert U, Gohler H, Hoffmann K, Misteli T. Ageing-related chromatin defects through loss of the NURD complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11:1261–1267. doi: 10.1038/ncb1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel CG, Dowen RH, Lourenco GF, Kirienko NV, Heimbucher T, West JA, Bowman SK, Kingston RE, Dillin A, Asara JM, Ruvkun G. DAF-16 employs the chromatin remodeller SWI/SNF to promote stress resistance and longevity. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013;15:491–501. doi: 10.1038/ncb2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson AV, Carr CE, Ruvkun G. Gene activities that mediate increased life span of C. elegans insulin-like signaling mutants. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2976–2994. doi: 10.1101/gad.1588907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Blanco A, Kim SK. Variable pathogenicity determines individual lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarov M, Schneider S, Pozniakovski A, Roguev A, Ernst S, Zhang Y, Hyman AA, Stewart AF. A recombineering pipeline for functional genomics applied to Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:839–844. doi: 10.1038/nmeth933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen S, Liu A, Li J, Wolubah C, Casaccia-Bonnefil P. Epigenetic memory loss in aging oligodendrocytes in the corpus callosum. Neurobiol. Aging. 2008;29:452–463. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore DE, Carr CE, Ruvkun G. Induction of cytoprotective pathways is central to the extension of lifespan conferred by multiple longevity pathways. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solari F, Bateman A, Ahringer J. The Caenorhabditis elegans genes egl-27 and egr-1 are similar to MTA1, a member of a chromatin regulatory complex, and are redundantly required for embryonic patterning. Development. 1999;126:2483–2494. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon A, Bandhakavi S, Jabbar S, Shah R, Beitel GJ, Morimoto RI. Caenorhabditis elegans OSR-1 regulates behavioral and physiological responses to hyperosmotic environments. Genetics. 2004;167:161–170. doi: 10.1534/genetics.167.1.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TeKippe M, Aballay A. C. elegans germline-deficient mutants respond to pathogen infection using shared and distinct mechanisms. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Nostrand EL, Sanchez-Blanco A, Wu B, Nguyen A, Kim SK. Roles of the developmental regulator unc-62/homothorax in limiting longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Kim SK. The GATA transcription factor egl-27 delays aging by promoting stress resistance in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1003108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y, Wong J, Moreno GT, Young MK, Cote J, Wang W. NURD, a novel complex with both ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling and histone deacetylase activities. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:851–861. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80299-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamawaki TM, Berman JR, Suchanek-Kavipurapu M, McCormick M, Gaglia MM, Lee SJ, Kenyon C. The somatic reproductive tissues of C. elegans promote longevity through steroid hormone signaling. PLoS Biol. 2010;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000468. e1000468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 egr-1 RNA is overexpressed in egr-1 overexpression lines, and increases with age in all genotypes.

Fig. S2 Brood size of EGR-1 overexpression lines.

Fig. S3 egr-1 RNAi reduces resistance to oxidative and UV stress, but not heat stress.

Fig. S4 EGR-1:GFP protein increases with age by immunofluorescence staining.

Fig. S5 EGR-1 expression is not induced in response to stress.

Fig. S6 RNAi controls.

Fig. S7 Changes in H3K9 acetylation by knockdown or overexpression of egr-1, and during aging.

Table S1 Additional lifespan data.

Table S2 Additional stress resistance data.

Table S3 Strains used in this study.