Abstract

Raloxifene is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) that binds to the estrogen receptor (ER), and exhibits potent anti-tumor and autophagy-inducing effects in breast cancer cells. However, the mechanism of raloxifene-induced cell death and autophagy is not well-established. So, we analyzed mechanism underlying death and autophagy induced by raloxifene in MCF-7 breast cancer cells.

Treatment with raloxifene significantly induced death in MCF-7 cells. Raloxifene accumulated GFP-LC3 puncta and increased the level of autophagic marker proteins, such as LC3-II, BECN1, and ATG12-ATG5 conjugates, indicating activated autophagy. Raloxifene also increased autophagic flux indicators, the cleavage of GFP from GFP-LC3 and only red fluorescence-positive puncta in mRFP-GFP-LC3-expressing cells. An autophagy inhibitor, 3-methyladenine (3-MA), suppressed the level of LC3-II and blocked the formation of GFP-LC3 puncta. Moreover, siRNA targeting BECN1 markedly reversed cell death and the level of LC3-II increased by raloxifene. Besides, raloxifene-induced cell death was not related to cleavage of caspases-7, -9, and PARP. These results indicate that raloxifene activates autophagy-dependent cell death but not apoptosis. Interestingly, raloxifene decreased the level of intracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and activated the AMPK/ULK1 pathway. However it was not suppressed the AKT/mTOR pathway. Addition of ATP decreased the phosphorylation of AMPK as well as the accumulation of LC3-II, finally attenuating raloxifene-induced cell death.

Our current study demonstrates that raloxifene induces autophagy via the activation of AMPK by sensing decreases in ATP, and that the overactivation of autophagy promotes cell death and thereby mediates the anti-cancer effects of raloxifene in breast cancer cells.

Keywords: AMPK, ATP, autophagy, breast cancer, raloxifene

INTRODUCTION

Macroautophagy (autophagy) is a self-digestion mechanism for degrading damaged organelles and misfolded proteins in the lysosomal compartments. Autophagy starts with the formation of double-membraned vesicles, or autophagosomes, which undergo maturation by fusion with lysosomes in order to create autolysosomes. In autolysosomes, the inner membrane of the autophagosome and its contents are degraded by lysosomal enzymes (Eskelinen, 2008; Maiuri et al., 2007). Under metabolic stress, autophagy maintains a balance between synthesis, degradation, and the subsequent recycling of macromolecules and organelles in order to continue survival. On the other hand, the overactivation of autophagy can promote cell death during persistent stress (Eskelinen, 2008; Levine, 2007; Levine and Kroemer, 2008; Morselli et al., 2009).

The paradox that autophagy plays a role in both survival and death is more complicated in cancer cells. The first specific link between autophagy and cancer was reported in 1999 by Levine et al. They reported that BECN1 acts as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting cell proliferation and tumorigenesis both in vitro and in vivo, and that downregulating autophagy may contribute to the progression of breast and other cancers (Liang et al., 1999). It was also reported that autophagy-dependent cell death is induced by many anti-cancer drugs, such as tamoxifen (Hwang et al., 2010), rapamycin (Takeuchi et al., 2005), arsenic trioxide (Kanzawa et al., 2005), and histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors (Liu et al., 2010). These reports suggested that the overactivation of autophagy is an important death mechanism in tumors, where apoptosis is limited. In contrast, several groups report that inhibiting autophagy facilitates tumor regression because autophagy promotes the survival of stressed cancer cells (Hippert et al., 2006). For these reasons, the relationship between autophagy and cancer cannot be summarized simply and requires further investigation.

Previously, we reported that tamoxifen induces autophagy-dependent cell death in MCF-7 cells via the accumulation of intracellular zinc ions and reactive oxygen species (ROS), which finally leads to lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP) (Hwang et al., 2010). Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERMs) that binds to the estrogen receptor (ER) and exhibits selective agonistic or antagonistic effects against target tissue (Fabian and Kimler, 2005). Tamoxifen is the first SERM to be used to treat and prevent ER-positive breast cancer (Fisher et al., 1998). Raloxifene has been used to prevent and treat osteoporosis in 2001, since it has an estrogenic activity in bone (Gizzo et al., 2013). In contrast, since it had and antiestrogenic activity in breast, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved raloxifene for reduction the risk of invasive breast cancer in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis and in postmenopausal women at high risk for invasive breast cancer in 2007 (Powles, 2011). In breast cancer cells, many studies demonstrated that in vivo and in vitro anti-tumorigenic effect of raloxifene (Shibata et al., 2010; Taurin et al., 2013). One of the these studies, Taurin et al. (2013) reports that raloxifene decreases tumorigenecity, migration, and invasion in breast cancer cells.

In our current study, we evaluated whether raloxifene induces autophagy-dependent mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), and autophagy, and is accordingly responsible for the anti-proliferative effects of raloxifene on MCF-7 breast cancer cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and drug treatment

MCF-7 human breast cancer cells expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP)-conjugated microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) (GFP-LC3-MCF-7) and red fluorescent protein (mRFP)-GFP tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3 (mRFP-GFP-LC3-MCF-7) were established as previously described (Hwang et al., 2010). These cells were pre-treated with various concentrations of raloxifene (Cayman, USA) in RPMI1640 medium containing 10% charcoal-stripped FBS (Thermo Scientific, Germany), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen, USA). Pancaspase inhibitor, caspase-9 inhibitor (R&D Systems, USA), 3-methyladenine (3-MA) (Sigma, USA), siRNA control, and siRNA BECN1 (Bioneer, USA) were applied for the indicated times prior to the addition of raloxifene.

Cell viability assay

CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (MTS assay) reagent (Promega, USA) was added to each well containing cells that had been treated with various drugs according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell viability was determined by measuring absorbance at 490 nm using a Sunrise microplate reader (TECAN, Switzerland).

Trypan blue exclusion assay

Cells were stained with 0.1% trypan blue solution (Invitrogen) for 1 min and counted using a homocytometer under a light microscope. The percentage and total number of stained dead cells were calculated.

ATP measurement

The CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Assay reagent (Promega) was added to each well according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The level of ATP was determined using an EnVision Multilabel Reader (Perkin-Elmer, USA) by measuring the luminescent signal.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed, as previously described (Hwang et al., 2010), using antibodies against BECN1, phospho-AMPK (Thr172), AMPK, phospho-ULK1 (Ser317), phospho-ULK1 (Ser757), ULK1, phospho-mTOR (Ser2448), mTOR, phospho-AKT (Ser473), AKT, tubulin (Cell Signaling, USA), ATG5 (Abcam, UK), LC3 (NOVUS Biologicals, USA), caspase-7, caspase-9, PARP (Santa Cruz Biochemicals, USA), and actin (Sigma). Actin or tubulin was used as the loading control.

RNA interference and transfection

Cells were transfected with 0.17 μM BECN1 siRNA (Thermo Scientific) or non-targeting control siRNA (Santa Cruz) for 48 h using Lipofectamin2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Autophagic flux analysis

mRFP-GFP-LC3-MCF-7 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, Sigma) and stained with 10 μM Hoechst33342 (Sigma) after treatment with raloxifene or rapamycin (Sigma). Images of the cells were obtained from the Operetta High Content Imaging System (Perkin-Elmer) and analyzed using the Harmony Analysis Software (Perkin-Elmer). Cells were detected with green (GFP) or red (mRFP) fluorescence. Autophagosomes are yellow puncta and autolysosomes are only red puncta in merged images. Autophagic flux was determined by increased percent of only red puncta in the merged images.

Statistics

Data were obtained from ≥ 3 independent experiments and are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical evaluations of the results were performed using one-way ANOVA. Data were considered significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

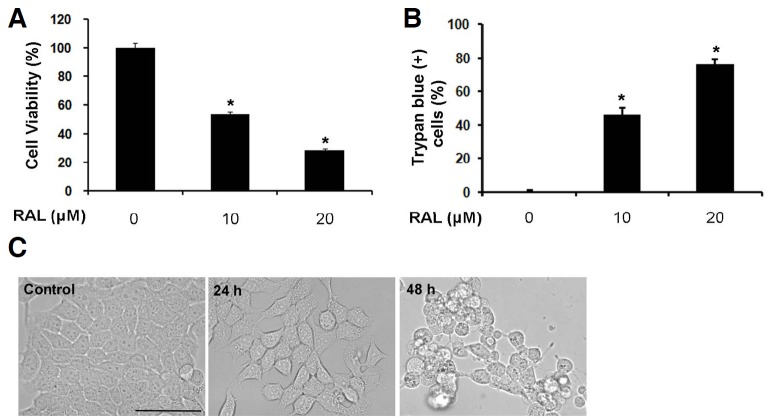

Raloxifene inhibits the growth of MCF-7 cells

Raloxifene has in vitro anti-estrogen activities on breast cancer cells, and associated with a decreased incidence of invasive breast cancer. Several studies have demonstrated that raloxifene is effective in other cancers such as prostate cancer and myeloma (Olivier et al., 2006; Rossi et al., 2011). However, their mechanism of anticancer effects is not established well. To assess the effects of raloxifene on cell growth, MCF-7 breast cancer cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of raloxifene for 48 h, and cell viability and death were examined using the MTS and trypan blue exclusion assays, respectively. Raloxifene efficiently attenuated cell growth and induced cell death in a concentration-dependent manner (Figs. 1A and 1B). We selected 10 μM raloxifene, which killed about 50% of cell within 48 h, for further analysis. Raloxifene-treated cells had rounded up at 24 h, detached from the dish, and died at 48 h when observed under a light microscope (Fig. 1C). These data indicate that raloxifene induces death in MCF-7 cells.

Fig. 1.

Raloxifene induces cell death and decreases cell viability in MCF-7 cells. (A) MCF-7 cells were treated with 10 μM or 20 μM raloxifene (RAL) for 48 h. Cell viability was assessed using the MTS assay (mean ± SD; n = 3). *P < 0.05 compared to control. (B) Cell death was evaluated using the trypan blue exclusion assay after treatment with raloxifene for 48 h (mean ± SD; n = 3). *P < 0.05 compared to control. (C) MCF-7 cells were treated with 10 μM raloxifene for 24 or 48 h. Cell morphology was examined using a light microscope (Magnification, 20×; Scale bar, 50 μm).

Raloxifene activates autophagy in MCF-7 cells

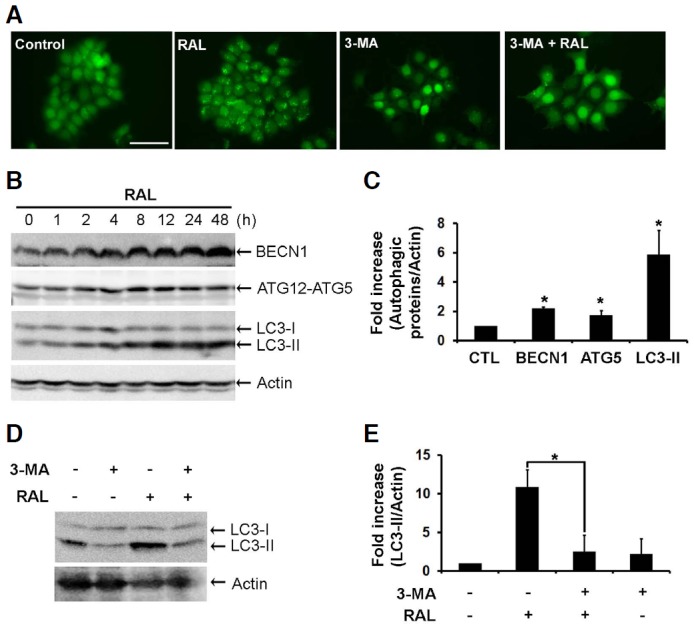

To monitor autophagic vacuoles (AVs), we used MCF-7 cells that constitutively expressed GFP-tagged LC3 (GFP-LC3-MCF-7). GFP-LC3 diffuses into the cytoplasm and nucleus under normal conditions, but conjugates with phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) and is incorporated into the AV membrane upon the induction of autophagy. These GFP-positive vacuoles can be visualized using fluorescent microscopy (Dorsey et al., 2009). When we exposed GFP-LC3-MCF-7 cells to raloxifene for 8 h, GFP-positive AVs were obviously apparent in comparison with the sham-washed control cells (Fig. 2A). We also detected autophagic marker proteins using Western blot analysis. Raloxifene augmented the level of BECN1 required for early autophagophore formation, in addition to the ATG12-ATG5 conjugates and LC3-II needed to elongate the autophagosomal membrane in a time-dependent manner (Figs. 2B and 2C). Pretreatment with 3-MA, which blocks autophagy by inhibiting class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), decreased GFP-positive AVs (Fig. 2A) and the level of LC3-II increased following raloxifene treatment (Figs. 2D and 2E), thereby confirming the activation of autophagy by raloxifene.

Fig. 2.

Raloxifene induces autophagy in MCF-7 cells. (A) GFP-LC3-MCF-7 cells were pretreated with 4 mM 3-MA for 4 h and then exposed to 10 μM raloxifene for an additional 8 h. These cells were observed under a fluorescent microscope (Magnification, 20×; Scale bar, 50 μm). (B) BECN1, ATG12-ATG5, and LC3 were analyzed by Western blot analysis in MCF-7 cells treated with 10 μM raloxifene for the indicated times. (C) Bar graph shows the densitometric measurements of autophagic marker proteins expressed in MCF-7 cells treated with 10 μM raloxifene for 8 h (mean ± SD; n = 3). Mean intensity was normalized to actin and compared with the each control (mean ± SD, n = 3). *P < 0.05 compared to control. (D) MCF-7 cells were pretreated with 4 mM 3-MA for 4 h and then exposed to 10 μM raloxifene for an additional 8 h. LC3 was analyzed using Western blot analysis. (E) Bar graph shows the densitometric measurements of the LC3-II in MCF-7 cells which were pretreated with 4 mM 3-MA for 4 h and then exposed to 10 μM raloxifene for an additional 8 h. (mean ± SD, n = 3). *P < 0.05 compared to raloxifene alone.

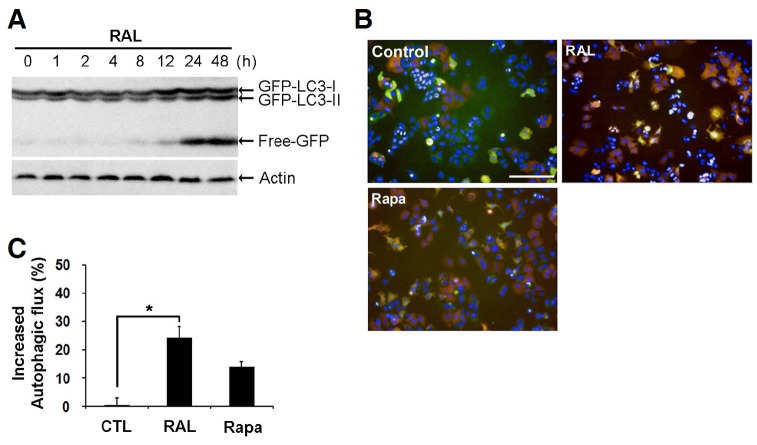

LC3-II is increased when the production of autophagophores or autophagosomes are increased or the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes are inhibited. So it is important to know whether raloxifene activates the whole process of autophagy. This process is called as autophagic flux which includes degradation of the contents of AVs after formation of autolysosome. It was reported that lysosomal hydrolases cleaved GFP-LC3-II and increased free-GFP proteins during the autophagic flux (Balgi et al., 2009). Raloxifene induced a time-dependent increase in free-GFP (Fig. 3A). Besides, we used MCF-7 cells that constitutively expressed mRFP-GFP tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3 (mRFP-GFP-LC3-MCF-7) to monitor autophagic flux. Because GFP fluorescence is unstable in the low pH, it will be quenched in the autolysosomes. But acidic insensitive-mRFP fluorescence will not be quenched (Mizushima et al., 2010). Therefore, while the yellow puncta represent the autophagosomes, the red puncta indicate autolysosomes in the merged fluorescent image, representing autophagic flux. Raloxifene increased the yellow and red puncta (Figs. 3B and 3C), indicating that raloxifene stimulates autophagic flux as well as the formation of AVs in MCF-7 cells.

Fig. 3.

Raloxifene activates autophagic flux in MCF-7 cells. (A) MCF-7 cells were treated with 10 μM raloxifene for the indicated times. GFP was analyzed using Western blot analysis. (B) mRFP-GFP-LC3-MCF-7 cells were exposed to 10 μM raloxifene and 400 nM rapamycin (Rapa) for 24 h, and fluorescent images were obtained from the Operetta automated microscope (Magnification, 20×; Scale bar, 50 μm). The yellow puncta indicate autophagosomes and red puncta represent autolysosomes. Rapamycin was used as a positive control to visualize the autophagic flux. (C) The percent of increased autophagic flux were calculated only red puncta in the merged images. Data are representation of two independent experiments (mean ± SD). *p < 0.05 according to one-way ANOVA.

Because MCF-7 cells are ER-positive breast cancer cells, we also examined if raloxifene induces autophagy in ER-negative SKBr-3 breast cancer cells and HCT116 colon cancer cells. In accordance with our previous study on tamoxifen (Hwang et al., 2010), raloxifene increased the level of LC3-II in these cell lines (data not shown). These results indicate that either raloxifene or tamoxifen activates autophagy regardless of the ER status in breast cancer and even colon cancer cells.

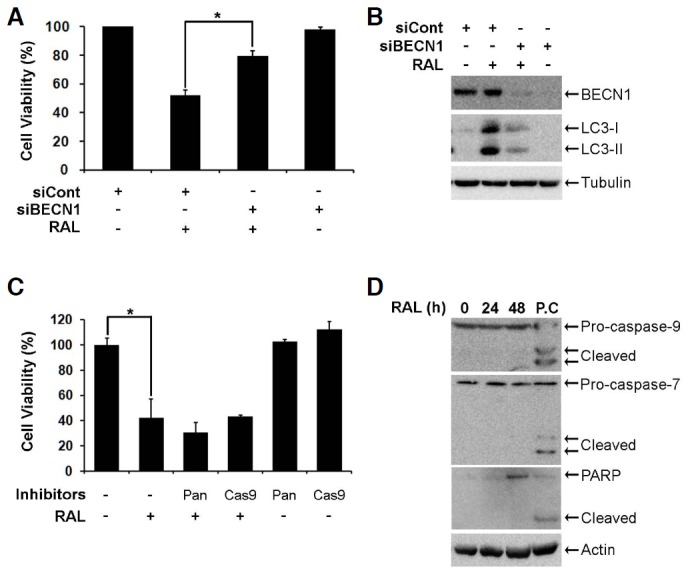

Raloxifene induces autophagy-dependent cell death in MCF-7 cells

To determine if raloxifene induces autophagy-dependent cell death, cell viability was measured in MCF-7 cells that were treated with raloxifene after BECN1 knockdown using siRNA. RNA interference against BECN1 recovered the viability of the MCF-7 cells that were treated with raloxifene for 48 h (Fig. 4A) and reduced the level of LC3-II as well as BECN1 that increased following raloxifene treatment (Fig. 4B). The addition of inhibitors for pan-caspase and caspase-9 neither reversed the decreased cell viability that occurred following raloxifene treatment (Fig. 4C), nor raloxifene-activated caspase-9 (Fig. 4D). Because MCF-7 cells had Caspase-3 deleted and expressed functional caspase-7 among various effector caspases, we next examined the cleavage of caspase-7 and its substrate, PARP. As expected, raloxifene did not facilitate the cleavage of these proteins (Fig. 4D). These results show that raloxifene induces cell death associated with autophagy, but not apoptosis in MCF-7 cells.

Fig. 4.

Raloxifene induces autophagy-dependent cell death. (A) MCF-7 cells were transfected with 0.17 μM non-targeting control siRNA (siCont) or BECN1 siRNA (siBECN1) for 48 h. Bars denote cell viability of cells treated with 10 μM raloxifene for 48 h, and cell viability was assessed using the MTS assay (mean ± SD; n = 3). *p < 0.05 according to one-way ANOVA. (B) MCF-7 cells were transfected with 0.17 μM siCont or siBECN1 for 48 h. BECN1 and LC3 were analyzed using Western blot analysis. (C) MCF-7 cells were pretreated with 20 μM caspase inhibitors for 2 h and then exposed to 10 μM raloxifene for 48 h. Cell viability was measured using the MTS assay (mean ± SD; n = 3). *p < 0.05 according to one-way ANOVA. (D) MCF-7 cells were treated with 10 μM raloxifene for the indicated times. Caspase-7, -9, and PARP were analyzed using Western blotting. The lysate of the HCT116 cells treated with 10 μM PXD101 for 24 h was used as a positive control (P.C) to assess the cleavage of caspase-7, -9, and PARP.

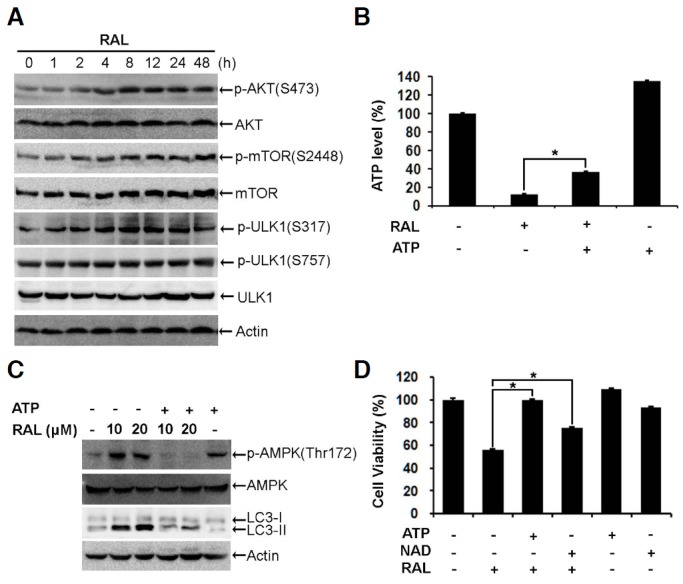

Raloxifene induces autophagy via AMPK activation

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms that underlie raloxifene-induced autophagy, we examined the upstream signaling pathways. First, we examined the inhibition of AKT and mTOR, which are well-known mechanisms of autophagy activation (He and Klionsky, 2009; Jung et al., 2010; Ryter et al., 2013; Yang and Klionsky, 2010). In contrast to our expectations, Western blot analysis revealed that the phosphorylation of AKT and mTOR increased following raloxifene treatment. Moreover, raloxifene did not change the phosphorylation of ULK1 at serine 757, an inhibitory site phosphotylated by mTOR (Fig. 5A). These results indicate that raloxifene-activated autophagy is not related to mTOR signaling. We next examined the level of intracellular ATP, because decrease in ATP activates AMPK. Exposure to raloxifene decreased the level of intracellular ATP to 12% (Fig. 5B), thereby increasing the phosphorylation of threonine 172 on APMK and serine 317 on ULK1 which is required to initiate autophagy (Figs. 5A and 5C). (Alers et al., 2012; Egan et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2010). The addition of ATP, which raised the level of intracellular ATP to 36% (Fig. 5B), rescued the cell viability reduced by raloxifene (Fig. 5D) and decreased phospho-AMPK as well as LC3-II (Figs. 5C). Accordingly, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), which accelerates the production of ATP (Khan et al., 2007), recovered the viability of the raloxifene-exposed cells (Fig. 5D). Collectively, these results suggest that raloxifene-induced autophagy and death are mediated by the activation of AMPK, without the inhibition of AKT/mTOR pathway.

Fig. 5.

Raloxifene activates AMPK/ULK1 signaling. (A) MCF-7 cells were exposed to 10 μM raloxifene for the indicated times. Phospho-AKT (S473), AKT, phospho-mTOR (S2448), mTOR, phospho-ULK1 (S317), phospho-ULK1 (S757), and ULK1 were analyzed using Western blotting. (B) MCF-7 cells were pretreated with 50 μM ATP for 2 h and then exposed to 10 μM raloxifene for 4 h. Bars denoted the level of ATP measured by the CellTiter-Glo Luminescent assay (mean ± SD; n = 3). *p < 0.05 according to one-way ANOVA. (C) MCF-7 cells were pretreated with 50 μM ATP for 2 h and then exposed to 10 or 20 μM raloxifene for 4 h. The level of phospho-AMPK (Thr172), AMPK, and LC3 were analyzed by Western blotting. (D) MCF-7 cells were pretreated with 50 μM ATP or 40 μM NAD for 2 h and then exposed to 10 μM raloxifene for 48 h. The cell viability was measured using the MTS assay (mean ± SD; n = 3). *p < 0.05 according to one-way ANOVA.

According to the 1996 study by Bursch et al. (1996) tamoxifen reportedly activates autophagy and induces type II cell death. We have also reported that tamoxifen increases the ROS- and zinc-mediated overactivation of autophagy, thereby leading to lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP) (Hwang et al., 2010). de Medina et al. (2009) reported that tamoxifen and other SERMs activate autophagy by modulating cholesterol metabolism. However, none of these studies described raloxifene in detail. Here, we show that raloxifene increases autophagy-mediated cell death by activating the AMPK pathway via decreases in intracellular ATP in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. The addition of ATP increased the intracellular level of ATP in this experiment, thereby protecting cells from raloxifene-induced cell death. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that extracellular role of ATP. Extracellular ATP binds to specific plasma membrane receptors (called P2 receptors) and initiates cellular signaling events such as growth, proliferation, and apoptosis (Deli and Csernoch, 2008). The anti-cancer activity of ATP has been reported by many groups, which have reported that ATP-activated P2 receptors decrease tumor growth and increase apoptosis in diverse types of cancers (Hopfner et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2004; White and Burnstock, 2006). Conversely, extracellular ATP activates P2 receptors followed by increases intracellular calcium and cell proliferation of MCF-7 cells, which is supported by ATP acting as a promoter of cell proliferation and growth (Dixon et al., 1997; Wagstaff et al., 2000). Therefore, further studies on the mechanisms by which raloxifene inhibits P2 receptor-mediated signaling are needed.

In this study, we suggest that raloxifene-induced decrease in ATP activates AMPK, leading to autophagy and autophagic flux. The overactivation of autophagy can lead to cell death, which can be one of the mechanisms of anti-cancer effect of raloxifene.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI06C0868, HI10C2014, and HI09C1345).

REFERENCES

- Alers S, Loffler AS, Wesselborg S, Stork B. Role of AMPK-mTOR-Ulk1/2 in the regulation of autophagy: cross talk, shortcuts, and feedbacks. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:2–11. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06159-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balgi AD, Fonseca BD, Donohue E, Tsang TC, Lajoie P, Proud CG, Nabi IR, Roberge M. Screen for chemical modulators of autophagy reveals novel therapeutic inhibitors of mTORC1 signaling. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bursch W, Ellinger A, Kienzl H, Torok L, Pandey S, Sikorska M, Walker R, Hermann RS. Active cell death induced by the anti-estrogens tamoxifen and ICI 164 384 in human mammary carcinoma cells (MCF-7) in culture: the role of autophagy. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:1595–1607. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.8.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Medina P, Payre B, Boubekeur N, Bertrand-Michel J, Terce F, Silvente-Poirot S, Poirot M. Ligands of the antiestrogen-binding site induce active cell death and autophagy in human breast cancer cells through the modulation of cholesterol metabolism. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1372–1384. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deli T, Csernoch L. Extracellular ATP and cancer: an overview with special reference to P2 purinergic receptors. Pathol Oncol Res. 2008;14:219–231. doi: 10.1007/s12253-008-9071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon CJ, Bowler WB, Fleetwood P, Ginty AF, Gallagher JA, Carron JA. Extracellular nucleotides stimulate proliferation in MCF-7 breast cancer cells via P2-purinoceptors. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:34–39. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey FC, Steeves MA, Prater SM, Schroter T, Cleveland JL. Monitoring the autophagy pathway in cancer. Methods Enzymol. 2009;453:251–271. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)04012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan D, Kim J, Shaw RJ, Guan KL. The autophagy initiating kinase ULK1 is regulated via opposing phosphorylation by AMPK and mTOR. Autophagy. 2011;7:643–644. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.6.15123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskelinen EL. New insights into the mechanisms of macroautophagy in mammalian cells. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2008;266:207–247. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(07)66005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian CJ, Kimler BF. Selective estrogen-receptor modulators for primary prevention of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1644–1655. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Redmond CK, Kavanah M, Cronin WM, Vogel V, Robidoux A, Dimitrov N, Atkins J, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the national surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project P-1 study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1371–1388. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.18.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gizzo S, Saccardi C, Patrelli TS, Berretta R, Capobianco G, Di Gangi S, Vacilotto A, Bertocco A, Noventa M, Ancona E, et al. Update on raloxifene: mechanism of action, clinical efficacy, adverse effects, and contraindications. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2013;68:467–481. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e31828baef9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, Klionsky DJ. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:67–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102808-114910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippert MM, O’Toole PS, Thorburn A. Autophagy in cancer: good, bad, or both? Cancer Res. 2006;66:9349–9351. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopfner M, Lemmer K, Jansen A, Hanski C, Riecken EO, Gavish M, Mann B, Buhr H, Glassmeier G, Scherubl H. Expression of functional P2-purinergic receptors in primary cultures of human colorectal carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;251:811–817. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang JJ, Kim HN, Kim J, Cho DH, Kim MJ, Kim YS, Kim Y, Park SJ, Koh JY. Zinc(II) ion mediates tamoxifen-induced autophagy and cell death in MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. Biometals. 2010;23:997–1013. doi: 10.1007/s10534-010-9346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung CH, Ro SH, Cao J, Otto NM, Kim DH. mTOR regulation of autophagy. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzawa T, Zhang L, Xiao L, Germano IM, Kondo Y, Kondo S. Arsenic trioxide induces autophagic cell death in malignant glioma cells by upregulation of mitochondrial cell death protein BNIP3. Oncogene. 2005;24:980–991. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan JA, Forouhar F, Tao X, Tong L. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide metabolism as an attractive target for drug discovery. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2007;11:695–705. doi: 10.1517/14728222.11.5.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:132–141. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Park S, Takahashi Y, Wang HG. The association of AMPK with ULK1 regulates autophagy. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B. Cell biology: autophagy and cancer. Nature. 2007;446:745–747. doi: 10.1038/446745a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang XH, Jackson S, Seaman M, Brown K, Kempkes B, Hibshoosh H, Levine B. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature. 1999;402:672–676. doi: 10.1038/45257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YL, Yang PM, Shun CT, Wu MS, Weng JR, Chen CC. Autophagy potentiates the anti-cancer effects of the histone deacetylase inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma. Autophagy. 2010;6:1057–1065. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.8.13365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiuri MC, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A, Kroemer G. Self-eating and self-killing: crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:741–752. doi: 10.1038/nrm2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Levine B. Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell. 2010;140:313–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morselli E, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Vicencio JM, Criollo A, Maiuri MC, Kroemer G. Anti- and pro-tumor functions of autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:1524–1532. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier S, Close P, Castermans E, de Leval L, Tabruyn S, Chariot A, Malaise M, Merville MP, Bours V, Franchimont N. Raloxifene-induced myeloma cell apoptosis: a study of nuclear factor-kappaB inhibition and gene expression signature. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1615–1623. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.020479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powles T. Prevention of breast cancer by newer SERMs in the future. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2011;188:141–145. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-10858-7_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi V, Bellastella G, De Rosa C, Abbondanza C, Visconti D, Maione L, Chieffi P, Della Ragione F, Prezioso D, De Bellis A, et al. Raloxifene induces cell death and inhibits proliferation through multiple signaling pathways in prostate cancer cells expressing different levels of estrogen receptor alpha and beta. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:1334–1339. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryter SW, Cloonan SM, Choi AM. Autophagy: a critical regulator of cellular metabolism and homeostasis. Mol Cells. 2013;36:7–16. doi: 10.1007/s10059-013-0140-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata MA, Morimoto J, Shibata E, Kurose H, Akamatsu K, Li ZL, Kusakabe M, Ohmichi M, Otsuki Y. Raloxifene inhibits tumor growth and lymph node metastasis in a xenograft model of metastatic mammary cancer. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:566. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi H, Kondo Y, Fujiwara K, Kanzawa T, Aoki H, Mills GB, Kondo S. Synergistic augmentation of rapamycin-induced autophagy in malignant glioma cells by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3336–3346. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taurin S, Allen KM, Scandlyn MJ, Rosengren RJ. Raloxifene reduces triple-negative breast cancer tumor growth and decreases EGFR expression. Int J Oncol. 2013;43:785–792. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagstaff SC, Bowler WB, Gallagher JA, Hipskind RA. Extracellular ATP activates multiple signalling pathways and potentiates growth factor-induced c-fos gene expression in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:2175–2181. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.12.2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Wang L, Feng YH, Li X, Zeng R, Gorodeski GI. P2X7 receptor-mediated apoptosis of human cervical epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C1349–1358. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00256.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White N, Burnstock G. P2 receptors and cancer. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Mammalian autophagy: core molecular machinery and signaling regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]