Abstract

Thioredoxin (TRX) is a disulfide reductase present ubiquitously in all taxa and plays an important role as a regulator of cellular redox state. Recently, a redox-independent, chaperone function has also been reported for some thioredoxins. We previously identified nodulin-35, the subunit of soybean uricase, as an interacting target of a cytosolic soybean thioredoxin, GmTRX. Here we report the further characterization of the interaction, which turns out to be independent of the disulfide reductase function and results in the co-localization of GmTRX and nodulin-35 in peroxisomes, suggesting a possible function of GmTRX in peroxisomes. In addition, the chaperone function of GmTRX was demonstrated in in vitro molecular chaperone activity assays including the thermal denaturation assay and malate dehydrogenase aggregation assay. Our results demonstrate that the target of GmTRX is not only confined to the nodulin-35, but many other peroxisomal proteins, including catalase (AtCAT), transthyretin-like protein 1 (AtTTL1), and acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 4 (AtACX4), also interact with the GmTRX. Together with an increased uricase activity of nodulin-35 and reduced ROS accumulation observed in the presence of GmTRX in our results, especially under heat shock and oxidative stress conditions, it appears that GmTRX represents a novel thioredoxin that is co-localized to the peroxisomes, possibly providing functional integrity to peroxisomal proteins.

Keywords: chaperone, peroxisome, thioredoxin, uricase

INTRODUCTION

Thioredoxins are small, ubiquitous proteins which act as disulfide reductase, catalyzing unidirectional thiol-disulfide interchange between themselves and substrate proteins, thereby playing as a major cellular redox switch (Collet and Messens, 2010; Couturier et al., 2013). By far the largest family of thioredoxins is found in plants, which can be subdivided into six major groups, Trxf, Trxm, Trxx, Trxy, Trxo, and Trxh, based upon the primary amino acid sequence similarities (Gelhaye et al., 2005). The chloroplast-targeted thioredoxins, which include Trxf, -m, -x, and –y, regulate the activity of the enzymes involved in photosynthetic carbon assimilation as well as other carbohydrate metabolisms (Lemaire et al., 2007). Trxo and a subset of Trxh are localized in the mitochondria, and they are thought to be involved in the regulation of a number of essential mitochondrial functions (Balmer et al., 2004; Gelhaye et al., 2004). Trxh, which represents the largest group of plant thioredoxins, are largely cytosolic but some non-cytosolic forms are also found in various subcellular locations including the nucleus, plasma membrane, extracellular matrices, apoplasts, and phloem saps (Meng et al., 2010; Serrato et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2011). In line with such diverse subcellular locations, they have been implicated in a number of different cellular processes including seed germination and development, oxidative stress responses, nodule development and intercellular communication. More recently, it has been also reported that some h-type thioredoxins exhibit chaperone function (Lee et al., 2009; Sanz-Barrio et al., 2012).

We previously identified a novel h-type thioredoxin from soybean (Glycine max) and demonstrated its positive role in nodule development (Lee et al., 2005). The protein, tentatively named GmTRX, was confirmed to be a cytosolic thioredoxin but showed a specific interaction with nodulin-35 (N35), a nodule-specific uricase targeted to the peroxisomes (Du et al., 2010). In the present study, we set out to further characterize this interaction and its outcome. Contrary to our initial view on the role of GmTRX, our results showed that the N35 uricase was not the only target of GmTRX for the interaction, but a number of other peroxisomal enzymes were also identified as its targets. GmTRX was found co-localized to the peroxisomes with these proteins, suggesting that it may play a role in protecting these proteins from damage by oxidative stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant materials

Arabidopsis thaliana (ecotype Columbia-0) seeds were surface-sterilized in 75% ethanol with 0.05% Tween-20 for 15 min, washed twice with 95% ethanol and once again with 100% ethanol. Arabidopsis plants were grown in a growth chamber at 22°C under long-day conditions (16-h light/8-h dark photoperiods) and used in protoplast isolation as described previously (Yoo et al., 2007).

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) analysis

cDNAs for the N-terminal (amino acid No. 1 to 158) and C-terminal regions (amino acid No. 158 to 238) of YFP were cloned into the p326-GFP vector after removing GFP to generate p326YFPN and p326YFPC, respectively. Full-length cDNA of the N35 was cloned into vector p326YFPN to generate N35-YFPN. Full-length cDNA or cDNA for the N-terminal (amino acid No. 1 to 40) or a C-terminal regions (amino acid No. 41 to 135) of GmTRX was cloned into p326YFPC to generate GmTRX-YFPC, GmTRX-NT-YFPC, and GmTRX-CT-YFPC, respectively. Amino acid substitution in the conserved catalytic amino acids (C59S and C62S) was carried out by PCR-mediated mutagenesis, forming GmTRXdm. cDNAs of AtCAT3, AtTTL1, AtTTL2, AtAPX1, and AtACX4 were cloned into the p326YFPN vector. The resulting fusion constructs were then introduced into Arabidopsis protoplasts as described previously (Yoo et al., 2007).

Chaperone activity

Chaperone activity was examined using malate dehydrogenase (MDH) or SmaI. Thermal aggregation of MDH was performed as described (Lee et al., 2009; Park et al., 2009; Sanz-Barrio et al., 2012). MDH was incubated in 50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 8.0) buffer at 43°C with various concentrations of GmTRX (molar ratios of GmTRX to MDH of 1:1, 2:1 and 4:1). The thermal aggregation of MDH was determined by monitoring the increase in turbidity at 340 nm using a spectrophotometer. For the SmaI activity assay (Santhoshkumar and Sharma, 2001), thermal denaturation was first performed at 37°C for 90 min, after which DNA digestion was carried out at 25°C for another 90 min. GmTRX or BSA was added to 3 units of SmaI in the supplied buffer.

Heat treatment

For the thermotolerance assay, the sterilized Arabidopsis seeds were plated on 0.8% agar plates of half-strength MS and grown at 22°C for 7 days. The plates were then sealed with parafilm, heated in a temperature-controlled water bath at 45°C for 2 h, and grown under normal growth conditions for 5 days.

Detection of hydrogen peroxide

As a hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) staining agent, 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) was used after dissolving in H2O and adjusting to pH 3.0 with HCl. The DAB solution was freshly prepared in order to avoid auto-oxidation. Two-week-old Arabidopsis seedlings grown after heat shock were immersed and infiltrated with 2 ml DAB solution under vacuum. After incubation for 4 h at room temperature, stained plantlets were bleached in acetic acid-glycerol-ethanol (1/1/3) (v/v/v) solution at 95°C for 15 min, and then stored in fresh bleaching solution until photographs were taken (Guan et al., 2013). Experiments were repeated three times using more than 20 plantlets.

Detection of ROS production

Arabidopsis protoplasts were isolated and heated at 42°C for 10 min. The protoplasts were then incubated with H2DCFDA at a final concentration of 5 μM for 10 min in the dark (Gomes et al., 2005). The ROS production was visualized under a Zeiss LCSM laser confocal scanning microscope. The fluorescence intensity of dichlorofluorescein (DCF) was also measured with a fluorescence spectrometer (PerkinElmer, LS55) at room temperature with excitation at 488 nm and emission at 500–600 nm.

Uricase assay

Plant extracts were isolated from 2-week-old seedlings of wild-type (Col-0), GmTRX-expressing, and GmTRXdm-expressing Arabidopsis after treatment with heat shock, H2O2 or menadione. Each extract was added to uricase reaction mixture containing 0.1 mM uric acid, and the uricase activity was measured as described previously (Du et al., 2010; Suzuki and Verma, 1991).

RESULTS

Interaction between GmTRX and nodulin-35 in Arabidopsis protoplasts

Despite being a cytosolic thioredoxin, GmTRX was found to interact with a peroxisomal protein, soybean uricase nodulin-35 (N35), in our previous study (Du at al., 2010). Our initial reasoning was that the actual interaction exists between a peroxisomal form of thioredoxin (TRX) and N35, and that the observed interaction merely reflects the structural similarity between peroxisomal and cytosolic TRXs. With no peroxisomal TRX having been identified either in soybean or Arabidopsis, we opted to use a mitochondrial TRX from Arabidopsis in our previous study to confirm the in vivo interaction with N35 via the bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) analysis (Du at al., 2010), because peroxisomes are most closely associated with mitochondria with active exchange of enzymes between the two organelles (Neuspiel et al., 2008). To test this possibility in root nodules, we generated transgenic nodules over-expressing either GmTRX or a peroxisomal form of TRX that was engineered by adding a peroxisomal targeting sequence 1 (PTS1; -Ser-Lys-Leu) to the cytosolic GmTRX, to form GmTRX-PTS1, and compared N35 activity of the two transgenic nodules. To our surprise, the transgenic nodules expressing the cytosolic GmTRX showed uricase activity as high as that of the transgenic nodules expressing the peroxisomal GmTRX-PTS1 (data not shown).

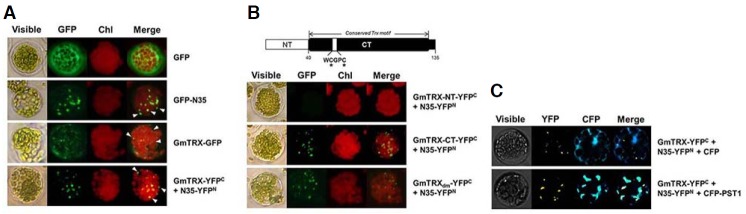

Thus, it was speculated that even though GmTRX is a cytoplasmic protein, it might establish a functional interaction with N35 and both ends up in the peroxisomes. This possibility was tested by BiFC analysis using the full-length cDNAs of GmTRX and N35, and as shown in Fig. 1A, protoplasts expressing both GmTRX-YFPC and N35-YFPN exhibited fluorescence, indicating that both proteins in fact interact with each other in vivo. The BLAST sequence comparison of GmTRX with other orthologuous cytosolic TRXs revealed that it contains additional 38 amino acids at the N-terminus (Fig. 1B). When the N-terminal extension of GmTRX (GmTRX-NT) was isolated separately and tested for binding with N35 by BiFC, it did not show any fluorescence signal, while the remainder of GmTRX (GmTRX-CT) containing the canonical catalytic domain of the thioredoxin family showed a strong interaction in the same assay (Fig. 1B), suggesting that the catalytic domain of GmTRX may be largely involved in the interaction. To further determine if the interaction is dependent upon the catalytic activity of GmTRX, we generated a mutant form of GmTRX (GmTRXdm), which was rendered catalytically inactive through substitution of both critical cysteine residues in the conserved catalytic motif (CXXC) with serines (see “Materials and Methods”), and tested its interaction with N35 via BiFC analysis as well. As shown in Fig. 1B, the protoplasts expressing GmTRXdm-YFPC and N35-YFPN constructs also exhibited a strong fluorescence signal, indicating that the interaction of GmTRX with N35 occurs independent of its thiol redox activity.

Fig. 1.

Analysis of the interaction between GmTRX and nodulin-35 (N35) in Arabidopsis protoplasts. Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) analyses of the interaction between GmTRX and N35 were performed as follows: expression of P35S-GFP as a control (GFP; A); expression of N35 fused to GFP (GFP-N35; A); expression of GmTRX fused to GFP (GmTRX-GFP; A); coexpression of P35S-GmTRX-YFPC and P35S-N35-YFPN (GmTRX-YFPC + N35-YFPN; A); coexpression of P35S-GmTRX-NT-YFPC and P35S-N35-YFPN (GmTRX-NT-YFPC + N35-YFPN; B); coexpression of P35S-GmTRX-CT-YFPC and P35S-N35-YFPN (GmTRX-CT-YFPC + N35-YFPN; B); coexpression of P35S-GmTRXdm-YFPC and P35S-N35-YFPN (GmTRXdm-YFPC + N35-YFPN; B); coexpression of P35S-GmTRX-YFPC, P35S-N35-YFPN and P35S-CFP (GmTRX-YFPC + N35-YFPN + CFP; C); and coexpression of P35S-GmTRX-YFPC, P35S-N35-YFPN and P35S-CFP-PTS1 (GmTRX-YFPC + N35-YFPN + CFP-PTS1; C). White arrowheads in (A) indicate the peroxisome-like area. A schematic representation of the domain structure of GmTRX used in the BiFC analysis is shown in (B); NT, the region of amino acids from No. 1 to 40; CT, the rest of the whole protein. Conserved cysteines in the catalytic domain (C59 and C62) are indicated. GmTRXdm: a mutated form of GmTRX with catalytic cysteins substituted (see “Materials and Methods”). PTS1: peroxisomal targeting signal 1. Chl: autofluorescence of chloroplasts. These experiments were replicated three times with similar results.

The observed BiFC signal pattern for the GmTRX-N35 complex appeared to coincide with that of the GFP-N35 (Figs. 1A and 1B), suggesting that GmTRX is co-localized to the peroxisomes. To verify the location of the GmTRX-N35 complex as peroxisome, we made a construct of cyan fluorescence protein (CFP) containing a peroxisomal targeting sequence 1 (CFP-PTS1) for use as a peroxisomal marker and co-transfected Arabidopsis protoplasts with the BiFC constructs of GmTRX and N35. The result revealed that most BiFC signals from the GmTRX-N35 interaction overlapped with that of CFP-PTS1 (Fig. 1C). When the full-length GmTRX alone was over-expressed in the protoplasts as a GFP fusion protein (Fig. 1A), GFP fluorescence was detected in these peroxisome-like area as well as in the cytoplasm. Thus, it seemed probable that GmTRX could also interact with the endogenous Arabidopsis uricase or with other peroxisomal proteins.

Property of GmTRX as a chaperone

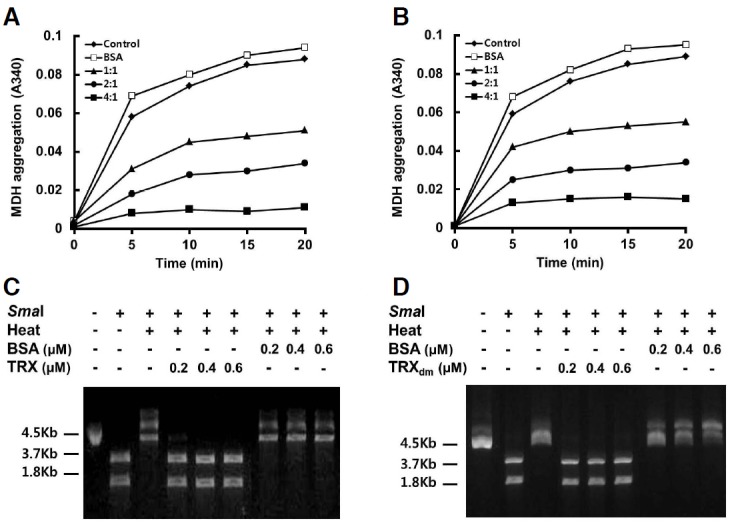

The finding that cytosolic GmTRX interacts with N35 in a redox-independent manner and is co-localized to peroxisomes led us to consider a possible chaperone function for GmTRX. It was previously reported that AtTDX, a thioredoxin-like protein of Arabidopsis, acts as a foldase or holdase chaperone as well as a disulfide reductase (Lee et al., 2009). Thus, the possibility that GmTRX may play a similar role as a chaperone was tested by assaying for holdase activity to reduce the thermal aggregation of malate dehydrogenase (MDH), as shown for other typical chaperones (Lee et al., 2009; Park et al., 2009; Sanz-Barrio et al., 2012). Incubation of MDH with increasing amounts of GmTRX or GmTRXdm indeed prevented the thermal aggregation of MDH, which showed maximum protection at a molar ratio of 4 GmTRX (or GmTRXdm) to 1 MDH (Figs. 2A and 2B). In addition, thermal denaturation assay on the restriction enzyme SmaI (Kumar et al., 2004; Santhoshkumar and Sharma, 2001) demonstrated that GmTRX could protect the enzyme from thermal inactivation. Incubation of SmaI at 37°C rendered complete loss of activity, while the activity was retained in the presence of GmTRX or GmTRXdm (Figs. 2C and 2D). These data altogether indicate that GmTRX indeed acts as a molecular chaperone, possibly facilitating the correct folding of N35.

Fig. 2.

Chaperone activity of GmTRX. (A, B) Holdase chaperone activity of GmTRX. Thermal aggregation of MDH was examined at 43°C in the absence (control; ◆) or presence of GmTRX (A) or GmTRXdm (B) with the molar ratios of GmTRX to MDH of 1:1 (▲), 2:1 (•), and 4:1 (■). Bovine serum albumin (BSA; □) was used as negative control. (C, D) Effects of GmTRX (C) or GmTRXdm (D) on the thermal denaturation of SmaI as a molecular chaperone. GmTRX, GmTRXdm or BSA was added to a reaction mixture containing 3 units of SmaI and incubated for 90 min at 37°C, and DNA digestion was performed at 25°C for another 90 min.

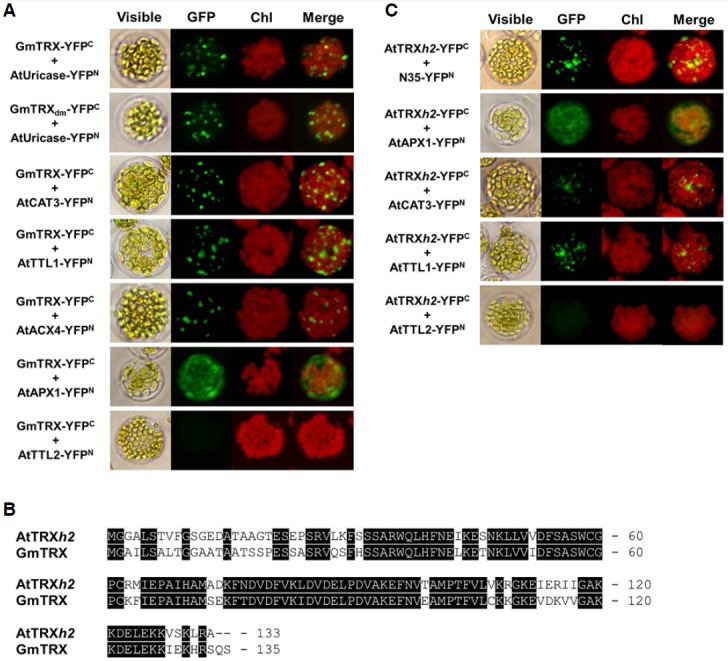

In order to determine if the proposed chaperone function of GmTRX is confined to nodulin-35 (N35), three additional peroxisomal proteins of Arabidopsis – transthyretin-Like 1 (AtTTL1; Scranton et al., 2012), catalase 3 (AtCAT3; Lamberto et al., 2010) and Acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 4 (AtACX4; Hu et al., 2012) – were chosen to test for interaction with GmTRX. All of the tested proteins were found to interact with GmTRX via BiFC analyses (Fig. 3A). The result also showed that GmTRX could interact with a cytosolic protein, AtAPX1 (Arent et al., 2010), while it did not interact with another cytosolic protein, AtTTL2 (Fig. 3A). These indicate that GmTRX is a cytosolic chaperone with a broad range of targets, the majority of which include peroxisomal proteins, as well as a few cytosolic proteins. Not so surprisingly, the observed role of GmTRX was also found to be conserved in Arabidopsis in that AtTRXh2, the closest orthologue of GmTRX in the Arabidopsis genome (Yamazaki et al., 2005; Fig. 3B), showed interaction with peroxisomal proteins including N35, AtCAT3, and AtTTL1 in the BiFC analysis (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Analysis of the interaction between GmTRX and peroxisomal proteins in Arabidopsis protoplasts. Two cytosolic proteins, AtAPX1 and AtTTL2, were used as controls. (A) BiFC analyses of the interaction between GmTRX and peroxisomal proteins were performed as follows: coexpression of P35S-GmTRX-YFPC and P35S-AtUricase-YFPN (GmTRX-YFPC + AtUricase-YFPN); coexpression of P35S-GmTRXdm-YFPC and P35S-AtUricase-YFPN (GmTRXdm-YFPC + AtUricase-YFPN); coexpression of P35S-GmTRX-YFPC and P35S-AtCAT3-YFPN (GmTRX-YFPC + At-CAT3-YFPN); coexpression of P35S-GmTRX-YFPC and P35S-AtTTL1-YFPN (GmTRX-YFPC + AtTTL1-YFPN); coexpression of P35S-GmTRX-YFPC and P35S-AtACX4-YFPN (GmTRX-YFPC + AtACX4-YFPN); coexpression of P35S-GmTRX-YFPC and P35S-AtAPX1-YFPN (GmTRX-YFPC + AtAPX1-YFPN); and coexpression of P35S-GmTRX-YFPC and P35S-AtTTL2-YFPN (GmTRX-YFPC + AtTTL2-YFPN). (B) Amino acid comparison of AtTRXh2 and GmTRX. Identical amino acid residues are shaded black. Dashes indicate gaps for optimizing alignment. (C) BiFC analyses of the interaction between AtTRXh2 and peroxisomal proteins were performed as follows: coexpression of P35S-AtTRXh2-YFPC and P35S-N35-YFPN (AtTRXh2-YFPC + N35-YFPN; coexpression of P35S-AtTRXh2-YFPC and P35S-AtAPX1-YFPN (AtTRXh2-YFPC + AtAPX1-YFPN); coex-pression of P35S-AtTRXh2-YFPC and P35S-AtCAT3-YFPN (AtTRXh2-YFPC + AtCAT3-YFPN); coexpression of P35S-AtTRXh2-YFPC and P35S-AtTTL1-YFPN (AtTRXh2-YFPC + AtTTL1-YFPN); and coexpression of P35S-AtTRXh2-YFPC and P35S-AtTTL2-YFPN (AtTRXh2-YFPC + AtTTL2-YFPN). Chl: autofluorescence of chloroplasts. These experiments were replicated three times with similar results.

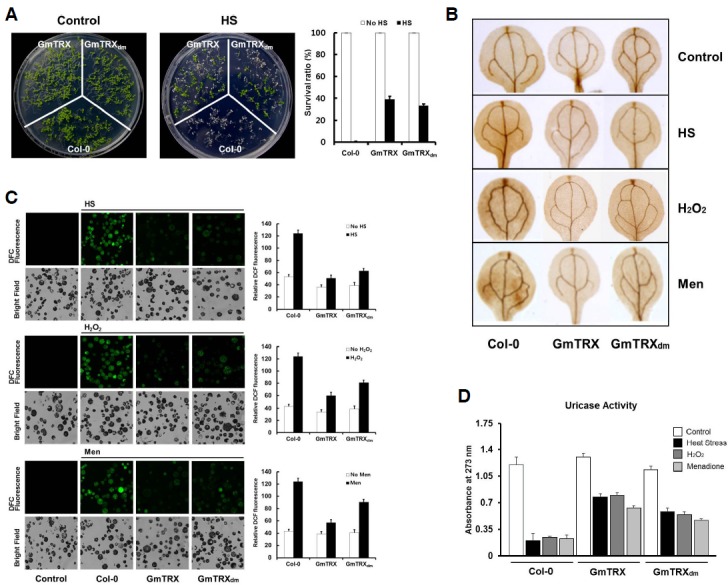

Enhanced protection from oxidative stresses by GmTRX overexpression

Previously, AtTrx-h3 was shown to confer enhanced heat-shock tolerance in Arabidopsis, primarily through its chaperone function (Park et al., 2009). To test if GmTRX can provide a similar biological function, seedlings of transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing GmTRX or GmTRXdm were subjected to heat stress at 45°C for 2 h. The transgenic plants showed no phenotypic differences compared with the wild type, but displayed greater heat tolerance than the wild-type plants, almost all of which did not survive over the recovery period after heat treatment (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Protective effects of GmTRX under oxidative stress. (A) Effects of GmTRX on Arabidopsis growth under heat shock (HS) conditions. Seven-day-old wild-type (Col-0), GmTRX-expressing, and GmTRXdm-expressing Arabidopsis seedlings were subjected to heat treatment at 45°C for 2 h and allowed to recover at 22°C for 5 days. Survival rates of wild-type (Col-0), GmTRX-expressing, and GmTRXdm-expressing Arabidopsis plants after heat shock (HS) treatment are shown. (B) The 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining for H2O2 accumulation in 2-week-old seedlings of wild-type (Col-0), GmTRX-expressing, and GmTRXdm-expressing Arabidopsis under heat shock, H2O2 and menadione (Men) treatment conditions. (C) ROS accumulation in Arabidopsis protoplasts. After treatment with heat shock, H2O2, and menadione (Men), protoplasts were kept at 22°C for about 1 h and then subjected to 5 μM H2DCFDA for 10 min. DCF fluorescence images were visualized by LCSM and the fluorescence intensities were measured with a fluorescence spectrometer (excitation at 488 nm, emission at 500–600 nm). (D) Effects of GmTRX on uricase activity under oxidative stress and heat stress. Uricase activity was measured using total proteins from wild-type (Col-0), GmTRX-expressing, and GmTRXdm-expressing Arabidopsis treated with HS, H2O2, or menadione.

It has been previously reported that ROS plays essential role in heat shock-induced programmed cell death in plant cells (Meyer et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2009). Thus, we checked the accumulation of H2O2 in seedling leaves by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining after heat shock. Under normal growth conditions, the highest level of H2O2 was detected in the wild-type plants, followed by the GmTRXdm transgenic plants and the GmTRX transgenic plants, in the order of the accumulation. With heat treatment, all the plants showed elevated levels of H2O2 but the relative level of accumulation was still far less in the transgenic plants expressing GmTRX or GmTRXdm (Fig. 4B).

The possible role of GmTRX in the elimination of cellular ROS was also tested by applying menadione, a ROS-generating chemical, to these seedlings or treating them directly with H2O2. Menadione is a redox-active compound often used in the study of cellular oxidative stress as a ROS generator producing supe-roxide radicals (O2−) and H2O2 (Borges et al., 2003). Again, DAB staining on the leaves of these plants after menadione or H2O2 treatment revealed that the transgenic plants expressing GmTRX or GmTRXdm had much lower levels of H2O2 than that of the wild-type control (Fig. 4B).

Next, the H2O2 accumulation was measured at the cellular level of these plants using the fluorescence probe, 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein (DCFH), which is converted to the highly fluorescent dichlorofluorescein (DCF) in the presence of H2O2 (Bartsch et al., 2008; Vacca et al., 2004). Protoplasts were isolated from these plants and measured for DCF fluorescence after treatment with heat, menadione or H2O2. Similar to the DAB staining results of the seedling leaves, the protoplasts derived from GmTRX- or GmTRXdm- transgenic plants showed less accumulation of H2O2 than those isolated from wild-type Arabidopsis (Fig. 4C).

Increased uricase activity resulting from the interaction with GmTRX in vitro was already observed in our previous study (Du et al., 2010). As our present study suggests that this enhancement was likely due to a redox-independent, chaperone function of GmTRX, we examined the effects of GmTRX and GmTRXdm overexpression on the endogenous uricase activity under oxidative stress conditions. The amino acids sequence of Arabidopsis uricase shows 68% identity with soybean N35. As expected, Arabidopsis uricase was able to interact with both GmTRX and GmTRXdm in Arabidopsis protoplasts (Fig. 3A). Under normal growth conditions, wild-type Arabidopsis plants and the GmTRX transgenic lines showed similar uricase activity. However, after heat shock, a sharp reduction in the uricase activity was observed in wild-type plants, whereas the GmTRX- and GmTRXdm- expressing plants showed that the uricase activity still retained up to 60% and 50% of the original level detected in unstressed plants, respectively (Fig. 4D). Similarly, treatment with H2O2 or menadione resulted in about 70–80% reduction of the enzyme activity in the wild-type plants, whereas the reduction of the enzyme activity in GmTRX-transgenic plants under the same conditions was only about 30–40% (Fig. 4D). Therefore, all these data consistently demonstrate a positive role played by GmTRX in protecting cellular components from oxidative stress, and the protection mechanism appears to be independent of its oxidoreductase activity.

DISCUSSION

As a thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase participating in the cellular redox signaling pathways, thioredoxins interact with many different target proteins to carry out their dynamic regulation of structure and function. Over the last few years, a number of new targets of thioredoxins have been identified in plants (Arent et al., 2010; Courteille et al., 2013).

We also identified the nodulin-35 (N35) to be an interacting partner of GmTRX (Du et al., 2010). Our initial interpretation of the observed interaction between GmTRX and the peroxisome-targeted N35 was that it was simply the reflection of a bona fide interaction between N35 and a yet-to-be identified peroxisomal form of thioredoxin. Many thioredoxins have been found in different subcellular compartments of plant cells, including chloroplasts, mitochondria, and the cytoplasm (Kern et al., 2003; Nuruzzaman et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2011), but no thioredoxins have been found to be located in peroxisomes until now. While our efforts to identify possible candidates for the peroxisomal thioredoxin in the soybean or Arabidopsis genome have been futile, our results showed that the cytoplasmic GmTRX was localized to the peroxisomes, together with N35 (Fig. 1). This interaction did not appear to be dependent upon the conventional catalytic activity of GmTRX since the catalytically inactive mutant form of GmTRX, GmTRXdm, also exhibited interaction with nodulin-35 and co-localization to the peroxisomes. It is possible that GmTRX may interact with many peroxisomal proteins in the cytoplasm, followed by their targeting to peroxisomes and that the peroxisomal protein with peroxisome targeting signal aids in translocation of the GmTRX-protein complex into the peroxisome. Another possibility is that GmTRX is somehow transported to the peroxisome wherein it then binds to the peroxisomal proteins.

Within peroxisomes, GmTRX could also provide the additional function of protecting the proteins from oxidative damages, as indicated by the results with GmTRX-transgenic plants (Fig. 4). An interesting aspect of the observed reduction of ROS by GmTRX is that it did not seem to require the conventional oxidoreductase activity of TRX, thus the catalytically inactive mutant GmTRXdm was as effective as the wild-type GmTRX in providing protection against ROS and heat stress, as well as in preserving the activity of peroxisomal enzymes such as uricase under such conditions. Hence, the observed protection by GmTRX against oxidative stress may be achieved indirectly through its chaperone function, stabilizing and thus enhancing the activity of ROS scavenging enzymes, with which GmTRX associates. Identification of catalase3 (AtCAT3) as one of the interacting proteins with GmTRX seems to support this scenario. Recent reports of the redox-independent, chaperone function of thioredoxins in E. coli, tobacco (N. tabacum), and Arabidopsis (Kern et al., 2003 ; Kthiri et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2009; Park et al., 2009; Sanz-Barrio et al., 2012) have provided a new insight into their diverse physiological roles. A novelty in our present finding is the potential role of GmTRX as a cytoplasmic chaperone largely specific for proteins targeted to peroxisomes. In addition to nodulin-35, we showed that other peroxisomal proteins were also the interacting targets of GmTRX. Moreover, AtTRXh2, the closest ortholog of GmTRX in the Arabidopsis genome, according to amino acid sequence homology comparison, was also found to interact with nodulin-35 and co-localized to the peroxisomes in our BiFC analysis (Fig. 3B). Therefore, the role of Trx as a specific interacting component for peroxisomal proteins may be a widely conserved mechanism at least in plants.

In summary, our present study demonstrated a prospect of a multi-functional thioredoxin, possibly acting both as a chaperone and a disulfide reductase and plays a key role in preserving the functional integrity of key enzymes in peroxisomes, especially under oxidative stress conditions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the SRC Research Center for Women’s Diseases of Sookmyung Women’s University (2011).

REFERENCES

- Arent S, Christensen CE, Pye VE, Nørgaard A, Henriksen A. The multifunctional protein in peroxisomal beta-oxidation: structure and substrate specificity of the Arabidopsis thaliana protein MFP2. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:24066–24077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.106005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balmer Y, Vensel WH, Tanaka CK, Hurkman WJ, Gelhaye E, Rouhier N, Jacquot JP, Manieri W, Schürmann P, Droux M, et al. Thioredoxin links redox to the regulation of fundamental processes of plant mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2642–2647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308583101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch S, Monnet J, Selbach K, Quigley F, Gray J, von Wettstein D, Reinbothe S, Reinbothe C. Three thioredoxin targets in the inner envelope membrane of chloroplasts function in protein import and chlorophyll metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4933–4938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800378105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges AA, Borges-Perez A, Fernandez-Falcon M. Effect of menadione sodium bisulfite, an inducer of plant defenses, on the dynamic of banana phytoalexin accumulation during pathogenesis. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;27:5326–5328. doi: 10.1021/jf0300689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collet JF, Messens J. Structure, function, and mechanism of thioredoxin proteins. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:1205–1216. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courteille A, Vesa S, Sanz-Barrio R, Cazalé AC, Becuwe-Linka N, Farran I, Havaux M, Rey P, Rumeau D. Thioredoxin m4 controls photosynthetic alternative electron pathways in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2013;161:508–520. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.207019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier J, Chibani K, Jacquot JP, Rouhier N. Cysteine-based redox regulation and signaling in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:105. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du H, Kim S, Nam KH, Lee MS, Son O, Lee SH, Cheon CI. Identification of uricase as a potential target of plant thioredoxin: Implication in the regulation of nodule development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;397:22–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelhaye E, Rouhier N, Gérard J, Jolivet Y, Gualberto J, Navrot N, Ohlsson PI, Wingsle G, Hirasawa M, Knaff DB, et al. A specific form of thioredoxin h occurs in plant mitochondria and regulates the alternative oxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14545–14550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405282101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelhaye E, Rouhier N, Navrot N, Jacquot JP. The plant thioredoxin system. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:24–35. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4296-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes A, Fernandes E, Lima JL. Fluorescence probes used for detection of reactive oxygen species. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 2005;65:45–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jbbm.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Q, Lu X, Zeng H, Zhang Y, Zhu J. Heat stress induction of miR398 triggers a regulatory loop that is critical for thermotolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2013;74:840–851. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Baker A, Bartel B, Linka N, Mullen RT, Reumann S, Zolman BK. Plant peroxisomes: biogenesis and function. Plant Cell. 2012;24:2279–2303. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.096586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern R, Malki A, Holmgren A, Richarme G. Chaperone properties of Escherichia coli thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. Biochem J. 2003;371:965–972. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kthiri F, Le HT, Tagourti J, Kern R, Malki A, Caldas T, Abdallah J, Landoulsi A, Richarme G. The thiore-doxin homolog YbbN functions as a chaperone rather than as an oxidoreductase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;374:668–672. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar JK, Tabor S, Richardson CC. Proteomic analysis of thioredoxin-targeted proteins in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3759–3764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308701101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamberto I, Percudani R, Gatti R, Folli C, Petrucco S. Conserved alternative splicing of Arabidopsis transthyretin-like determines protein localization and S-allantoin synthesis in peroxisomes. Plant Cell. 2010;22:1564–1574. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.070102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MY, Shin KH, Kim YK, Suh JY, Gu YY, Kim MR, Hur YS, Son O, Kim JS, Song E, et al. Induction of thioredoxin is required for nodule development to reduce reactive oxygen species levels in soybean roots. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:1881–1889. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.067884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JR, Lee SS, Jang HH, Lee YM, Park JH, Park SC, Moon JC, Park SK, Kim SY, Lee SY, et al. Heat-shock dependent oligomeric status alters the function of a plant-specific thioredoxin-like protein, AtTDX. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5978–5983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811231106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire SD, Michelet L, Zaffagnini M, Massot V, Issakidis-Bourguet E. Thioredoxins in chloroplasts. Curr Genet. 2007;51:343–365. doi: 10.1007/s00294-007-0128-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng L, Wong JH, Feldman LJ, Lemaux PG, Buchanan BB. A membrane-associated thioredoxin required for plant growth moves from cell to cell, suggestive of a role in intercellular communication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3900–3905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913759107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer Y, Reichheld JP, Vignols F. Thioredoxins in Arabidopsis and other plants. Photosynth Res. 2005;86:419–433. doi: 10.1007/s11120-005-5220-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuspiel M, Schauss AC, Braschi E, Zunino R, Rippstein P, Rachubinski RA, Andrade-Navarro MA, McBride HM. Cargo-selected transport from the mitochondria to peroxisomes is mediated by vesicular carriers. Curr Biol. 2008;18:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuruzzaman M, Sharoni AM, Satoh K, Al-Shammari T, Shimizu T, Sasaya T, Omura T, Kikuchi S. The thioredoxin gene family in rice: genome-wide identification and expression profiling under different biotic and abiotic treatments. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;423:417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.05.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SK, Jung YJ, Lee JR, Lee YM, Jang HH, Lee SS, Park JH, Kim SY, Moon JC, Lee SY, et al. Heat-shock and redox-dependent functional switching of an h-type Arabidopsis thioredoxin from a disulfide reductase to a molecular chaperone. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:552–561. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.135426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santhoshkumar P, Sharma KK. Analysis of alpha-crystallin chaperone function using restriction enzymes and citrate synthase. Mol Vis. 2001;7:172–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Barrio R, Fernández-San Millán A, Carballeda J, Corral-Martínez P, Seguí-Simarro JM, Farran I. Chaperone-like properties of tobacco plastid thioredoxins f and m. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:365–379. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scranton MA, Yee A, Park SY, Walling LL. Plant leucine aminopeptidases moonlight as molecular chaperones to alleviate stress-induced damage. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:18408–18417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.309500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrato AJ, Crespo JL, Florencio FJ, Cejudo FJ. Characterization of two thioredoxins h with predominant localization in the nucleus of aleurone and scutellum cells of germinating wheat seeds. Plant Mol Biol. 2001;46:361–371. doi: 10.1023/a:1010697331184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Verma DP. Soybean Nodule-Specific Uricase (Nodulin-35) Is Expressed and Assembled into a Functional Tetrameric Holoenzyme in Escherichia coli. Plant Physiol. 1991;95:384–389. doi: 10.1104/pp.95.2.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacca RA, de Pinto MC, Valenti D, Passarella S, Marra E, De Gara L. Production of reactive oxygen species, alteration of cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase, and impairment of mitochondrial metabolism are early events in heat shock-induced programmed cell death in tobacco Bright-Yellow 2 cells. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:1100–1112. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.035956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki D, Motohashi K, Kasama T, Hara Y, Hisabori T. Target proteins of the cytosolic thioredoxins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005;45:18–27. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SD, Cho YH, Sheen J. Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: a versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1565–1572. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Li Y, Xing D, Gao C. Characterization of mitochondrial dynamics and subcellular localization of ROS reveal that HsfA2 alleviates oxidative damage caused by heat stress in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:2073–2091. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang CJ, Zhao BC, Ge WN, Zhang YF, Song Y, Sun DY, Guo Y. An apoplastic h-type thioredoxin is involved in the stress response through regulation of the apoplastic reactive oxygen species in rice. Plant Physiol. 2011;157:1884–1899. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.182808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]