Abstract

The development of cancer has been an extensively researched topic over the past few decades. Although great strides have been made in cancer prevention, diagnosis, and treatment, there is still much to be learned about cancer’s micro-environmental mechanisms that contribute to cancer formation and aggressiveness. Macrophages, lymphocytes which originate from monocytes, are involved in the inflammatory response and often dispersed to areas of infection to fight harmful antigens and mutated cells in tissues. Macrophages have a plethora of roles including tissue development and repair, immune system functions, and inflammation. We discuss various pathways by which macrophages get activated, various approaches that can regulate the function of macrophages, and how these approaches can be helpful in developing new cancer therapies.

Keywords: angiogenesis, cancer, invasion, macrophages, microenvironment, migration

INTRODUCTION

Macrophages are important cells of the immune system. They are derived from monocytes which enter various tissues and differentiate into macrophages. In the immune response, they use phagocytosis, a process in which the macrophages engulf pathogens, to protect the human body from disease. In addition to macrophages’ importance to the general functions of the immune system, they also play various roles in cancer. These macrophages, or tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), interact with cancer cells to cause phagocytosis and lysis of tumor cells. On the other hand, TAMs have also been discovered to be an integral part of the tumorigenic pathway. The balance of cytokines and other molecular signals determines the role of these TAMs and thus it is important to study them closely. However, it is important to note that approximately 80% of studies show an association between TAMs and pro-tumorigenic effects while only 10% of studies show the opposite effect.

Before delving into TAMs’ function in cancer, it is important to understand the general cancer process. Cancer can be broken into three distinct stages. In the first stage, cancerous cells invade an area’s surrounding tissues and blood vessels; this area is referred to as the primary site. In the second stage, the cancer cells begin to move to secondary sites through the circulatory system. In the third and final stage, the cancer cells invade the secondary site’s surrounding tissues and blood vessels. This cycle can then repeat yielding tertiary sites and so forth. Once the primary site is established, tumor development is spurred by angiogenesis. Hanahan and Weinberg (2000), created a model that lays out the six properties that a tumor acquires while growing. These properties include an ability to replicate endlessly, angiogenesis, evasion of apoptosis, creating its own growth signals, insensitivity to growth inhibitors, and tissue invasion and metastasis. A seventh property, tumor microenvironment inflammation, was later added to the model (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2000; Mantovani, 2009) (Fig. 1). Here we discuss the mechanisms by which macrophages get activated and their important role in tumor progression.

Fig. 1.

The major steps involved in cancer. This model depicts essential steps during cancer progression. These steps include continuous replication, developing new blood vessels, self- sufficiency of growth signals, insensitivity to growth inhibitors, formation of inflammatory microenvironment, promotion of tissue invasion and metastasis, and evasion of apoptosis (Adapted from Mantovani, 2009).

TUMOR ASSOCIATED MACROPHAGES AND RELATED MOLECULES

Two different types of phenotypes for macrophages have been described; these include: M1 and M2. The M1 phenotype is associated with active microbial killing while the M2 phenotype is associated with angiogenesis and wound repair. TAMs can typically be identified by low expression of tumor necrosis factors (TNF) and high expression of IL-1 and IL-6. Specifically M1 macrophage polarization is caused by interferon gamma (IFN-gamma) and TNF-α secretion by T helper 1 (Th1) lymphocytes or natural killer (NK) cells (Gordon, 2003; Martinez et al., 2009; Murray and Wynn, 2011). Interferon (IFNs) or toll-like receptor (TLR) signals can produce the M1 phenotype through the STAT1 signaling pathway. M1 macrophages also produce chemical attractants, such as pro-inflammatory cytokines, interleukin-12 (IL-12), IL-1β, and IL-6 (Heusinkveld and van der Burg, 2011; Porta et al., 2011). M2 macrophages, on the other hand, are activated by Th2. Th2 releases several cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13, to activate the M2 macrophages (Gordon, 2003; Murray and Wynn, 2011). The M2 macrophage phenotype is caused by IL-4 and IL-13 via the STAT6 signaling pathways. In addition, Kruppel-like factor 4 (KFL4) works in conjunction with STAT6 to produce M2 genes, while inhibiting M1 genes through isolation of some NF-κB activators. Unlike the M1 phenotype, the M2 phenotype can be divided into 3 more categories: M2a, M2b, and M2c. M2a is differentiated by IL-4 and IL-13 while M2b by immune complexes. M2c is differentiated by IL-10 and also plays a role in immunosuppression and tissue remodeling (Hagemann et al., 2009). Furthermore, it has been shown that Th1 cytokines produce M1 macrophages while M2 macrophages play a role in Th1 adaptive immunity suppression, resolution of inflammation, parasite protection, wound healing promotion, angiogenesis, and tissue remodeling (Biswas and Mantovani, 2010).

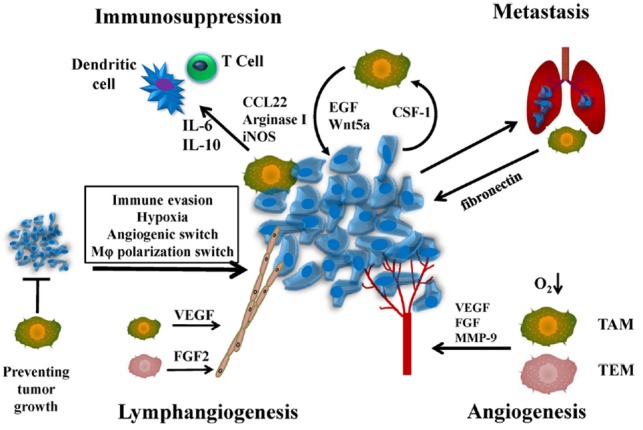

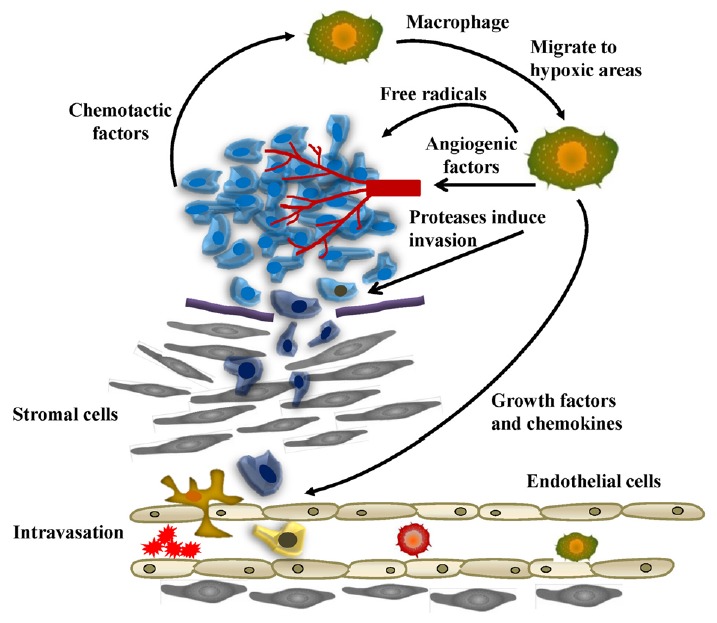

Some of the most potent macrophage activators of metastasis involved in Lewis lung carcinoma lead to the production of IL-6 and TNF-α through the activation of essential-to-metastasis TLR2 and TLR6 (Chiodoni et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2009). These macrophages are recruited to tumor cells by the production of monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP), macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), angiopoietin 1 (ANG1), and ANG2. In addition to macrophage recruitment, VEGF, ANG1, and ANG2 play roles in promoting angiogenesis (Pollard, 2004). Anti-inflammatory molecules, such as IL-4, IL-10, transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1), and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) produced by tumor cells cause macrophages to attain the M2 phenotype. Adding IL-10 in vitro inhibits production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Kim et al., 1995). IL-10 also reduces surface expression of major histocompatibility complex II (MHCII) and co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 resulting in immunosuppression (Moore et al., 2001). Additionally, IL-10 interacts with IL-4 to cause Arginase-1 expression in macrophages (Lang et al., 2002). The source of this IL-10 is not yet known, but PGE2, which is produced by tumor cells, has been shown to effect TAM polarization along with EP4 receptors (Akaogi et al., 2004; Heusinkveld et al., 2011; Kambayashi et al., 1995). TLRs, such as TLR2 and TLR4, cause cytokines to become proinflammatory and thus polarize TAMs. The production of proteases by TAMs, such as urokinase type plasminogen activator (uPA) and MMP-9, further enhance tumor invasion by breaking down the basement membrane and remodeling the stromal matrix (Huang et al., 2002; Stetler-Stevenson and Yu, 2001; Wang et al., 2005). Epidermal growth factor (EGF), TGF-β, IL-8, and TNF-α all play roles in the migration of tumor cells in addition to protecting the tumor cells by providing them with proliferative and anti-apoptotic signals. TGF-β1 derived from macrophages also caused greater expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) in glioma stem-like cells which has been shown to increase tumor cell invasiveness (Ye et al., 2012). MMP-9 also causes the release of VEGF-A, a precursor to angiogenesis. In addition, M2 macrophages express a truncated fibronectin isoform, migration-stimulation factor (MSF), which has a large chemotactic effect on tumor cells. Depletion studies conducted by Denardo et. al and Joyce and Pollard showed reduced levels of metastasis as well (DeNardo et al., 2009; Joyce and Pollard, 2009). Furthermore, macrophages that are attracted to inflammation or tissue breakdown sites have been shown to promote tumorigenesis by synthesizing estrogens (Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2.

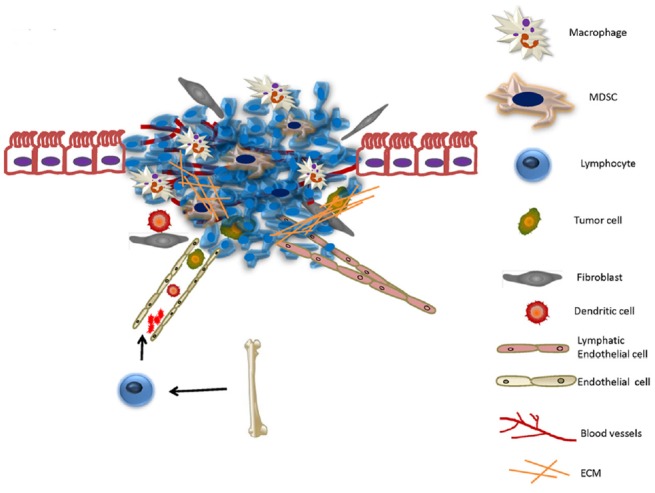

The tumor microenvironment. It is created the moment the tumor becomes attached to a site and encompasses the extracellular matrix surrounding the tumor cell and any non-cancerous cells. This microenvironment is composed of endothelial cells, stromal cells, bone marrow derived cells, macrophages and TIE2-expressing monocytes and myeloid derived suppressor cells.

Fig. 3.

Macrophage functions in the tumor microenvironment with special emphasis on immunosuppression, metastasis, lymphangiogenesis and angiogenesis. During immunosuppression, TAM generated molecules prevent the accumulation of cytotoxic T cells (anti-tumorigenic cells). During metastasis, tumor cells secrete soluble factors that prime specific cells such as macrophages that help in seeding tumor cells at distant locations. In hypoxic areas, TAMs and TEMs (Tie2-expressing monocytes) upregulate several angiogenic factors that promote angiogenesis. During lymphangiogenesis, TAMs secrete various factors that initiate the formation of lymphatics.

Looking further into VEGF, it has been determined that it is an angiogenic factor that triggers angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Angiogenic and lymphangiogenic factors include VEGF-A, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, and MMP that all bind to their respective coordinating receptors and play roles in enhancing endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and tube-like formation (Giraudo et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2012). MMP has also been shown to mediate VEGF-A levels in some studies. Specifically, MMPs are proteolytic enzymes tasked with the degradation of proteins within the extracellular matrix. They regulate many cell behaviors within the tumor microenvironment (Egeblad and Werb, 2002).

The importance of lymphangiogenesis must not be understated because it plays a large role in tumor stability and growth even though it occurs second to angiogenesis in a tumor. Lymphangiogenesis exposes the tumor to immune cells leading to lymphatic metastasis and without it, the tumor would likely stop growing and be destroyed (Kurahara et al., 2012). Lymphangiogenesis is typically induced by VEGF-A and VEGF C/D binding with VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 receptors. In addition, tissue inflammation in tumors has been shown to expand lymph nodes and lead to increased lymphangiogenesis and lymphoid hyperplasia. Inhibition of M-CSF has been shown to suppress tumor lymphangiogenesis since it plays a role in VEGF-A/C secretion. Interestingly, endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and IL-6 also regulate lymphangiogenesis (Ji, 2011) (Fig. 3).

Research has shown that there is a positive correlation between the number of TAMs and advanced tumor progression and metastasis. Many tumors show overexpression of M-CSF and when down-regulated, there is a decrease in macrophage activity. Knocking out MCP has led to lower levels of macrophages and decreased tumor progression as well. These data demonstrate a clear relationship between TAMs and tumorigenesis. Surprisingly, further overexpression of MCP has shown that at a certain point, M1 macrophages are attracted to the site causing cytotoxic effects on the tumor cells (Shirabe et al., 2011).

In addition to the decrease in macrophage activity due to the downregulation of M-CSF, vascularization is also reduced. Without vascularization, larger tumors struggle to grow due to insufficient amounts of oxygen causing hypoxic regions. TAMs compensate for this effect by congregating in these areas causing upregulation of certain transcription factors that lead to the expression of various growth factors, cytokines, and other signaling molecules resulting in angiogenesis (Obeid et al., 2013). These transcription factors cause secretion of VEGF and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) which promote the proliferation and maturation of endothelial cells (Lamagna et al., 2006; Siveen and Kuttan, 2009). TAM created proteases, such as MMPs, plasmin, and urokinase plasminogen activator, degrade and remodel the extracellular matrix leading to further angiogenesis (Siveen and Kuttan, 2009).

The majority of research indicates increased levels of TAM activity result in a negative prognosis. The M1 phenotype is usually present during early stages of tumor development while the M2 phenotype is associated with more advanced tumors. In addition, compounds such as VEGF and M-CSF allow for tumor development to progress by recruiting macrophages to the tumor site and initiating angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis.

TUMOR MICROENVIRONMENT AND MACROPHAGES

The tumor microenvironment is a niche that has been shown to affect tumor activity and outcome. It is created the moment the tumor becomes attached to a site and encompasses the extracellular matrix surrounding the tumor cell and any non-cancerous cells that happen to reside in the targeted organ (Fig. 2).

Colony stimulating factor 1 (CSF1) and chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) in the blood recruit monocytes that become TAMs in the tumor microenvironment, a process called intraepithelial neoplasia. In addition to CSF-1, the cytokines VEGF and PDGF and chemokines CCL2, CCL5, and CCL8 all attract monocytes to the tumor microenvironment (Allavena et al., 2008; Goede et al., 1999; Mantovani et al., 2008; Pollard, 2004) (Fig. 3). It may be important to note that CCL2 upregulation is caused by a RAS mutation (Qing et al., 2012). Consequently, overexpression of CSF-1 has led to a poor prognosis in patients with breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancers (Pollard, 2004; 2009). CSF-1 also interacts with IL-6 causing the maturation of dendritic cells creating a tumor microenvironment in which the tumor’s progression to metastasis is easier. Interestingly, CSF-1 in a trans-membrane form on the tumor surface has been shown to activate macrophages that kill tumor cells. Trans-membrane CSF-1 with higher concentrations of IL-4, IL-12, IL-13, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GMCSF) causes dendritic cells to mature as well; however, this leads to the presentation of tumor antigens to cytotoxic T cells resulting in the killing of the tumor (Pollard, 2004). By producing growth factors such as VEGF, TAMs assist the transition from intraepithelial neoplasia to an early carcinoma. While the carcinoma develops, TAMs continue to be activated allowing them to promote angiogenesis, cell invasion, intravasation, and immunosuppression. These abilities are due to the fact that TAMs are immobilized in hypoxic or necrotic regions of human tumors and, thus, TAMs upregulate hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) and HIF-2α (Raica et al., 2009). TAMs specifically promote angiogenesis with the help of Tie2-expressing monocytes (TEMs) and tumor cells themselves by upregulating angiogenic growth factors and enzymes to stimulate endothelial cells in the healthy surrounding areas to proliferate, migrate, and differentiate into the vessels in the tumor site (Coffelt et al., 2009). Evidence has shown that the tumor microenvironment is immunosuppressive causing the tumor to go unnoticed by the immune response. For example, M-CSF has been shown to render unable macrophages’ ability to present antigens. TAMs also produce immunomodulatory cytokines and growth factors that assist in immunosuppression (Galdiero et al., 2013). Typically, this occurs at the primary site or locations where lymphocytes mature, such as lymph nodes. TAMs also show immunosuppressive activity through their modulation of TGF-β, iNOS, Arginase-1, IDO, and IL-10 (Hagemann et al., 2006; Mantovani and Sica, 2010; Sica et al., 2000; Zhao et al., 2012a; 2012b). For instance, Arginase-1 and iNOS expression causes T cell suppression in mouse models of breast cancer (Bronte and Zanovello, 2005; Chang et al., 2001; Doedens et al., 2010; Movahedi et al., 2010). TAMs have also been shown to express B7-H1 in hepatocellular carcinoma, B7-H4 in ovarian and lung cancers, and B7-H3 in lung cancer on tumor cell surfaces which make it easier for the tumor cells to not be susceptible to immune response (Chen et al., 2012). These cytokines change the expression of genes by regulating NF-κB, a transcription factor, in addition to STAT1 and STAT3. Thus, the recruitment of antitumorigenic cells is downregulated resulting in a decrease of essential components of antigen-presenting. This inability to perform these functions affects the cytokine and protein profile of the tumor microenvironment, which plays a large role in determining the phenotype of local phagocytes (Coffelt et al., 2009).

TUMOR ASSOCIATED MACROPHAGE REGULATION BY TRANSCRIPTION FACTORS

It has been reported that some transcription factors also regulate TAM functions. Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) is activated by TNF-α, IL-1, and IKKβ. NF-κB refers to a family of transcription factors that plays a role in inflammation and immunity. NF-κB operates by causing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and angiogenic factors (Porta et al., 2011). Thus NF-κB is an important part of the regulation of TAM function. Transcription factors for NF-κB include Re1A (p65), c-Rel, RE1B, p50, and p52. Out of those transcription factors, only Re1A, Re1B, and c-Rel can activate gene transcription (Hagemann et al., 2009). NF-κB is activated primarily by IKKβ (Maeda et al., 2005). Another activator of NF-κB is hypoxia, a common marker of tumors (Rius et al., 2008). Activating NF-κB in inflammatory macrophages releases cytokines, interleukins, and TNF-α. It has been shown in breast cancer cells that secretion of TNF-α, activation of NF-κB, and presence of JNK leads to a more invasion and tumor progression. Inhibition of NF-κB also directly leads to lower levels of VEGF, impeding angiogenesis. IκBα is a prominent inhibitor of NF-κB and results in decreased tumor formation when it is overexpressed (Pikarsky et al., 2004). Interestingly, it has also been shown that low levels of NF-κB activation results in macrophages acquiring the M2 phenotype. A theory explaining this discrepancy is that NF-κB may have a different role depending on the stage and location of the TAMs within a tumor. This was shown in epithelial cells when IKKβ was knocked out and inflammation decreased, while in myeloid cells, inflammation was increased (Fong et al., 2008; Lawrence et al., 2001). In contrast, some reports indicate that targeted NF-κB activation can induce apoptosis of hepatocytes while decreasing tumor size, suggesting multiple roles of NF-κB (Greten et al., 2004; Hagemann et al., 2008; Luedde et al., 2007; Maeda et al., 2005; Naugler et al., 2007; Swain and Arezzo, 2008).

TUMOR ASSOCIATED MACROPHAGE REGULATION BY HYPOXIA

There have been many studies examining the effect of hypoxia on TAMs within the tumor microenvironment (Fig. 4). Low levels of tissue oxygenation induce TAM differentiation of macrophages (Erler et al., 2009; Shen et al., 2012). HIF activation has been determined to promote tumorigenesis due to higher levels of angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and TAM differentiation. There are 3 types of HIFs: HIF-1α, -2α, and -3α. HIF-1α is an important part of TAM response to hypoxia due to its ubiquitous expression and its induction of many hypoxia-inducible genes (Rankin and Giaccia, 2008). VEGF and CXCL12 are dependent on HIF-1α (Knowles and Harris, 2007). HIF-1α also regulates CSF-1. NF-κB can be modulated to regulate HIF-1α (Murdoch et al., 2004). Furthermore, deletion of HIF-1α has shown reduced tumor growth (Shen et al., 2012). Hypoxia causes HIF-1α to upregulate genes such as VEGF, bFGF, IL-1β, IL-8, cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2), MMP-7, MMP-9, MMP-12, and ANG-1 which lead to macrophages assuming the M2 phenotype and formation of a vascular system and malignant transition (Murdoch and Lewis, 2005; Murdoch et al., 2008). Increased HIF-2α expression in macrophages leads to angiogenesis and worse survival (Leek et al., 2002). Accordingly, TAMs with the highest levels of HIF-2α indicate high-grade breast cancers (Leek et al., 2002). Without HIF-1α, the suppressive capabilities of TAMs were reduced while without HIF-2α, there was less TAM recruitment in inflammatory hepatocellular and colon carcinoma models (Imtiyaz et al., 2010).

Fig. 4.

Functions of tumor associated macrophages during tumor cell migration and invasion. Macrophages migrate to hypoxic areas and in turn stimulate angiogenesis with the help of various angiogenic factors. TAMs also promote invasion through the secretion of proteases. Several growth factors and chemokines aid in promoting migration of tumor cells to the vessels, and TAMs can break down the basement membrane as well to promote intravasation.

TAMs AS POTENTIAL DIAGNOSTIC AND PROGNOSTIC MARKERS

TAMs in breast tumor microenvironments typically express four surface markers; receptors for Fc portion of IgG and C3, HLA-DR antigen, and a macrophage-associated antigen (Steele et al., 1985). CD68, the human homolog of macrosialin, has been widely used as a pan-macrophage marker. There are many antibodies that recognize CD68 including Ki-M6, Ki-M7, Y2/131 and Y1/82A, EBM11, KP1, Ki-M1P, and PG-M1 (Gottfried et al., 2008). Increased CD68 expression has been shown to correlate with high vascularity and nodal metastasis and reduced recurrence-free and survival in human breast cancer (Jubb et al., 2010; Leek et al., 1996). Mahmoud et al., showed that increased CD68 markers predicted worse breast cancer-specific survival and shorter disease-free interval (Mahmoud et al., 2011). Other markers such as estrogen receptors (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2) give a positive prognosis and were specifically designed to aid in therapy. However, it is not known how TAMs are associated with ER/PR/HER2 and thus more research must be conducted on the relationship between them before suggesting it as a possible treatment option. TAMs have also been shown to interfere with chemotherapy for breast cancer by releasing chemo-resistance factors or regulating the drug-resistance of cancer stem cells.

Since CD68 staining stains both M2 and M1 macrophages, CD68 cannot be used by itself to predict overall survival (Jubb et al., 2010; Mahmoud et al., 2011; Tsutsui et al., 2005). Thus other TAM-associated markers such as CD163, VEGF, HIFs markers, proliferating cellular nuclear antigen (PCNA), ferritin light chain (FTL), and CCL-18 have been proposed as possible options to use for detection of TAMs along with CD68. CD163 has been shown to be primarily expressed by M2 macrophages and thus has been associated with worse characteristics (Medrek et al., 2012). VEGF and EGFR are involved in macrophage infiltration in human breast cancer (Leek et al., 2000). VEGF, as noted previously, recruits more macrophages to the tumor microenvironment. TAMs with PCNA have been associated with high-grade, HR-negative breast cancers with an increased risk of recurrence and decreased overall survival in human breast cancers (Campbell et al., 2010; Mukhtar et al., 2011a). FTL stored in M2 macrophages indicates an aggressive phenotype in node-negative breast cancer patients. CCL18 is abundantly produced by breast cancer TAMs and is associated with metastasis and reduced patient survival. The counts predicted disease stage, histological grade, and lymph node and distant metastasis (Chen et al., 2011). Recent studies have indicated that CCL18 is a new and promising biomarker for cancer diagnosis and treatment.

POSSIBLE TREATMENT STRATEGIES USING VARIOUS PROTEINS AND SMALL MOLECULES

Tumor suppressors act in a variety of ways including inducing cell-cycle arrest, senescence, or apoptosis. Retinoblastoma protein (Rb) plays a role in cell cycle control, differentiation, and inhibition of oncogenic transformation in addition to activation of NF-κB pathway. Promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML) plays a role in tumorigenesis, DNA damage, senescence, apoptosis, and protein degradation. P53 plays a role in ribosome biogenesis, aging control, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis. P53 also regulates MCP-1/CCL2. ARF, interestingly, is one of the most frequently mutated genes in human cancer (Sharpless, 2005). ARF activates p53 and inhibits ribosomal RNA processing and transcriptional factors that induce proliferation. ARF activates p53 by displacing Mdm2 in the nucleolus (Pomerantz et al., 1998; Stott et al., 1998), and inhibits ribosomal RNA processing and transcriptional factors that induce proliferation (Kuo et al., 2003; Martelli et al., 2001; Qi et al., 2004; Sugimoto et al., 2003). ARF has a protective effect against viral infection by interacting with cell proliferation nucleophosmin (NPM) and activating dsRNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) (Garcia et al., 2006). ARF may even modulate M2 polarization of macrophages. ARF-deficient macrophages show less leukocyte recruitment and decreased ability to produce pro-inflammatory properties. E2F1 is increased in ARF-deficient mice which have been shown to be anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive which impaired the signaling of the NF-κB pathway. On the other hand, it has been shown to be deleted in some cancers thus more research must be conducted to further elucidate ARF’s function and effectiveness as a target for possible gene therapy.

Other methods have been investigated in order to interrupt or decrease macrophage recruitment to tumor microenvironments. Leuschner et al. used lipid nanoparticles containing siRNA to interrupt the CCL2-CCR2 interaction in order to disrupt macrophage recruitment. Using this method, they showed that the TAM infiltration was decreased (Leavy, 2011; Leuschner et al., 2011; Shantsila et al., 2011). Deletion of the CSFR1 gene reduced macrophage recruitment as well but only in resident tissue macrophages under normal conditions (MacDonald et al., 2010). Denardo et al. showed that using the PlexxiKon inhibitor, which inhibits CSFR1, along with cKit and PDGFR improved overall survival in mouse mammary carcinoma models (Denardo et al., 2011; Hume and MacDonald, 2011). Dijkgraaf et al. showed that blocking NF-κB signaling stopped platinum chemotherapy’s effect of increased IL-6 and PGE2 causing more M2 differentiation. Thus anti-IL-6 therapy is another recommended route for therapies (Dijkgraaf et al., 2013). Other approaches include inhibition of GM-CSF in vivo and decreased VEGF and CCL-5 as ways to reduce monocyte recruitment (Bayne et al., 2012; Elbarghati et al., 2008; Pylayeva-Gupta et al., 2012). Hystidine-rich glycoprotein (HRG) has been shown to have anti-tumor mechanisms in breast, pancreatic, and fibro-sarcoma murine models. Although there were no significant differences in TAM accumulation, the tumor volume was significantly decreased. Thus, HRG may be reducing M2 differentiation as levels of CXCL9 and IFN-β are increased, which is a characteristic for M1 macrophages (Rolny et al., 2011). CD40 has also been used to make macrophages attain the classical M1 phenotype (Beatty et al., 2011; Chan et al., 2010).

One way to directly target macrophage phenotype differentiation in tumor microenvironments is by targeting the NF-κB pathway. This was done by inhibiting IKKβ, the main activator of NF-κB in murine models. This led to reduced tumor volume (Hayakawa et al., 2009). Another method to reduce tumor survival is to reprogram the TME to impair tumor growth only. This can be accomplished by using antibodies such as ipilimumab which targets CTLA-4 activating T cells, nivolumab, lambrolizumab, and CD40 targeted antibodies. Nivolumab targets the PD1 receptor causing apoptosis, while lambrolizumab is a blocking antibody for the PD1 ligand (Hamid et al., 2013; Hodi et al., 2010; Hwu, 2010; Restifo et al., 2012; Sharma et al., 2011; Vonderheide and Glennie, 2013; Wolchok et al., 2013). Combining these strategies may reduce tumor cells’ evasion of the immune response and help destroy them. All of these methods have been somewhat effective and resulted in greater overall survival.

Therapeutic treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) that target TAMs have focused on inhibition of recruitment and/or polarization of M2 macrophages, inhibition of angiogenic and tissue remodeling, and inhibition of TAMs’ immunosuppressive effects. Clodronate-encapsulated liposomes or aminobisphosphonates knock down macrophages in vivo but have also been shown to reduce angiogenesis and tumor progression. Researchers have also attempted to prevent M2 polarization or to convert them from M2 to M1. This was attempted by using the CpG immunostimulatory oligonucleotide and anti-IL-10 receptor which caused macrophages to turn from M2 to M1 (Vicari et al., 2002). TAMs lacking STAT6 also display an M1 phenotype which can lead to further possibilities to prevent M2 polarization. CCL2/MCP-1 were discovered to have antitumor effects by using suicide gene therapy as well (Kakinoki et al., 2010; Tsuchiyama et al., 2008).

BISPHOSPHONATES AS THERAPEUTIC MODALITIES

Bisphosphonates are stable inorganic analogs of pyrophosphonate in which the central oxygen atom is replaced with a carbon atom. They are common in the treatment of many bone diseases such as cancer-induced bone disease, Paget’s disease, and osteoporosis. There are two types of bisphosphonates: nitrogen-containing (N-BP) and non-nitrogen containing (non N-BP) which are characterized by the presence of a nitrogen atom on the R2 side chain (Rodan and Fleisch, 1996; Stresing et al., 2007; Winter and Coleman, 2009). Non N-BPs inhibit the conversion of ATP to ADP which causes mitochondrial dysfunction leading to apoptosis. N-BPs alter protein prenylation by inhibiting farnesyldiphosphonate (FPP) synthase which is important for the mevalonate pathway in eukaryotic cells (Green, 2002; Luckman et al., 1998; Monkkonen et al., 2006; Moreau et al., 2007; Stern, 2007).

To target TAMs in breast cancer, N-BPs are utilized. They interfere with the process of PTHrP, prostaglandin-E, and interleukins stimulating RANKL causing osteoclast progression which in turn causes bone resorption leading to release of TGF-β helping tumor cells proliferate and grow. Specifically, they interfere with the bone resorption step in this cycle (Mundy, 2002). N-BPs have also been shown to directly affect tumors by reducing tumor cell proliferation, adhesion, migration, invasion, and angiogenesis while increasing apoptosis (Boissier et al., 1997; 2000; Fromigue et al., 2000; Hiraga et al., 2004; Senaratne et al., 2000; 2002; van der Pluijm et al., 1996). Biphosphonates can also directly target macrophages due to their similarities with osteoclasts. Using them has been shown to inhibit macrophage proliferation, migration, invasion, and cause apoptosis. They can also inhibit MMP-9 as shown in vivo and in vitro and inhibit VEGF, and thereby angiogenesis and polarization to M2 macrophages. This effect, in turn, resulted in decreased tumor sizes and growth (Coscia et al., 2009; Gabrilovich and Nagaraj, 2009; Mantovani et al., 2002). Other studies have shown the usage of N-BPs have resulted in similar results, presenting a promising therapeutic treatment for various cancers.

CONCLUSION

Much research has been completed elucidating the effects of TAMs in cancer. It has been shown that TAMs have a generally pro-tumorigenic effect. With this knowledge, it is possible to determine new therapies targeting TAMs and using them against the tumor to reduce volume and stunt tumor growth. A few proteins such as Rb, PML, and p53 act as tumor suppressors allowing for modulation of the proteins in an attempt to curb tumor growth. A viable and promising option is to modulate ARF, one of the most commonly mutated genes in cancer, to activate p53. This method has been shown to be promising, but more research must be completed. Directly targeting TAMs by reducing monocyte recruitment is another feasible option. This may be accomplished by interrupting the CCL2-CCR2 interaction. Another method to accomplish this is to downregulate GM-CSF, a crucial component used to recruit monocytes to the tumor. Similarly, it may be more feasible to control M2 differentiation by upregulating HRG or CD-40 to cause macrophages to assume the M1 phenotype, associated with antitumorigenic effects. The NF-κB pathway can also be targeted by inhibiting it with IKKβ reducing M2 differentiation. N-BPs have also been introduced as a novel idea to decrease tumor growth. N-BPs were shown to interfere in tumor cell proliferation, adhesion, migration, invasion, and angiogenesis while increasing apoptosis. In addition, N-BPs can inhibit MMP-9 and VEGF resulting in less M2 polarization and decreased angiogenesis.

Research on each of the aforementioned methods seems to indicate that they are all viable methods in the fight against cancer. More research must be completed to confirm their effects and usefulness in fighting tumors by attacking TAMs. It is clear, however, that progress is being made and novel methods to fighting cancer are on the horizon.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank LSU School of Medicine and LACaTS for financial support.

REFERENCES

- Akaogi J, Yamada H, Kuroda Y, Nacionales DC, Reeves WH, Satoh M. Prostaglandin E2 receptors EP2 and EP4 are up-regulated in peritoneal macrophages and joints of pristane-treated mice and modulate TNF-alpha and IL-6 production. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:227–236. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1203627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allavena P, Sica A, Solinas G, Porta C, Mantovani A. The inflammatory micro-environment in tumor progression: the role of tumor-associated macrophages. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;66:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayne LJ, Beatty GL, Jhala N, Clark CE, Rhim AD, Stanger BZ, Vonderheide RH. Tumor-derived granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor regulates myeloid inflammation and T cell immunity in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:822–835. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty GL, Chiorean EG, Fishman MP, Saboury B, Teitelbaum UR, Sun W, Huhn RD, Song W, Li D, Sharp LL, et al. CD40 agonists alter tumor stroma and show efficacy against pancreatic carcinoma in mice and humans. Science. 2011;331:1612–1616. doi: 10.1126/science.1198443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:889–896. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissier S, Magnetto S, Frappart L, Cuzin B, Ebetino FH, Delmas PD, Clezardin P. Bisphosphonates inhibit prostate and breast carcinoma cell adhesion to unmineralized and mineralized bone extracellular matrices. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3890–3894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissier S, Ferreras M, Peyruchaud O, Magnetto S, Ebetino FH, Colombel M, Delmas P, Delaisse JM, Clezardin P. Bisphosphonates inhibit breast and prostate carcinoma cell invasion, an early event in the formation of bone metastases. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2949–2954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronte V, Zanovello P. Regulation of immune responses by L-arginine metabolism. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:641–654. doi: 10.1038/nri1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MJ, Tonlaar NY, Garwood ER, Huo D, Moore DH, Khramtsov AI, Au A, Baehner F, Chen Y, Malaka DO, et al. Proliferating macrophages associated with high grade, hormone receptor negative breast cancer and poor clinical outcome. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;128:703–711. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1154-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan LL, Cheung BK, Li JC, Lau AS. A role for STAT3 and cathepsin S in IL-10 down-regulation of IFN-gamma-induced MHC class II molecule on primary human blood macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88:303–311. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1009659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CI, Liao JC, Kuo L. Macrophage arginase promotes tumor cell growth and suppresses nitric oxidemediated tumor cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1100–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Yao Y, Gong C, Yu F, Su S, Liu B, Deng H, Wang F, Lin L, Yao H, et al. CCL18 from tumor-associated macrophages promotes breast cancer metastasis via PITPNM3. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:541–555. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Shen Y, Qu QX, Chen XQ, Zhang XG, Huang JA. Induced expression of B7-H3 on the lung cancer cells and macrophages suppresses T-cell mediating anti-tumor immune response. Exp Cell Res. 2012;319:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiodoni C, Colombo MP, Sangaletti S. Matricellular proteins: from homeostasis to inflammation, cancer, and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:295–307. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9221-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffelt SB, Hughes R, Lewis CE. Tumor-associated macrophages: effectors of angiogenesis and tumor progression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1796:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coscia M, Quaglino E, Iezzi M, Curcio C, Pantaleoni F, Riganti C, Holen I, Monkkonen H, Boccadoro M, Forni G, et al. Zoledronic acid repolarizes tumour-associated macrophages and inhibits mammary carcinogenesis by targeting the mevalonate pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;14:2803–2815. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00926.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNardo DG, Barreto JB, Andreu P, Vasquez L, Tawfik D, Kolhatkar N, Coussens LM. CD4(+) T cells regulate pulmonary metastasis of mammary carcinomas by enhancing protumor properties of macrophages. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denardo SJ, Wen X, Handberg EM, Bairey Merz CN, Sopko GS, Cooper-Dehoff RM, Pepine CJ. Effect of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibition on microvascular coronary dysfunction in women: a Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) ancillary study. Clin Cardiol. 2011;34:483–487. doi: 10.1002/clc.20935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkgraaf EM, Heusinkveld M, Tummers B, Vogelpoel LT, Goedemans R, Jha V, Nortier JW, Welters MJ, Kroep JR, van der Burg SH. Chemotherapy alters monocyte differentiation to favor generation of cancer-supporting M2 macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2480–2492. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doedens AL, Stockmann C, Rubinstein MP, Liao D, Zhang N, DeNardo DG, Coussens LM, Karin M, Goldrath AW, Johnson RS. Macrophage expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha suppresses T-cell function and promotes tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7465–7475. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:161–174. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbarghati L, Murdoch C, Lewis CE. Effects of hypoxia on transcription factor expression in human monocytes and macrophages. Immunobiology. 2008;213:899–908. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erler JT, Bennewith KL, Cox TR, Lang G, Bird D, Koong A, Le QT, Giaccia AJ. Hypoxia-induced lysyl oxidase is a critical mediator of bone marrow cell recruitment to form the premetastatic niche. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong CH, Bebien M, Didierlaurent A, Nebauer R, Hussell T, Broide D, Karin M, Lawrence T. An antiinflammatory role for IKKbeta through the inhibition of “classical” macrophage activation. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1269–1276. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromigue O, Lagneaux L, Body JJ. Bisphosphonates induce breast cancer cell death in vitro. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:2211–2221. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.11.2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galdiero MR, Bonavita E, Barajon I, Garlanda C, Mantovani A, Jaillon S. Tumor associated macrophages and neutrophils in cancer. Immunobiology. 2013;218:1402–1410. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MA, Collado M, Munoz-Fontela C, Matheu A, Marcos-Villar L, Arroyo J, Esteban M, Serrano M, Rivas C. Antiviral action of the tumor suppressor ARF. EMBO J. 2006;25:4284–4292. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraudo E, Inoue M, Hanahan D. An aminobisphosphonate targets MMP-9-expressing macrophages and angiogenesis to impair cervical carcinogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:623–633. doi: 10.1172/JCI22087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goede V, Brogelli L, Ziche M, Augustin HG. Induction of inflammatory angiogenesis by monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. Int J Cancer. 1999;82:765–770. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990827)82:5<765::aid-ijc23>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried E, Kunz-Schughart LA, Weber A, Rehli M, Peuker A, Muller A, Kastenberger M, Brockhoff G, Andreesen R, Kreutz M. Expression of CD68 in non-myeloid cell types. Scand J Immunol. 2008;67:453–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2008.02091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JR. Bisphosphonates in cancer therapy. Curr Opin Oncol. 2002;14:609–615. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200211000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greten FR, Eckmann L, Greten TF, Park JM, Li ZW, Egan LJ, Kagnoff MF, Karin M. IKKbeta links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell. 2004;118:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann T, Wilson J, Burke F, Kulbe H, Li NF, Pluddemann A, Charles K, Gordon S, Balkwill FR. Ovarian cancer cells polarize macrophages toward a tumor-associated phenotype. J Immunol. 2006;176:5023–5032. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.5023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann T, Lawrence T, McNeish I, Charles KA, Kulbe H, Thompson RG, Robinson SC, Balkwill FR. “Re-educating” tumor-associated macrophages by targeting NF-kappaB. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1261–1268. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann T, Biswas SK, Lawrence T, Sica A, Lewis CE. Regulation of macrophage function in tumors: the multifaceted role of NF-kappaB. Blood. 2009;113:3139–3146. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-172825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, Hodi FS, Hwu WJ, Kefford R, Wolchok JD, Hersey P, Joseph RW, Weber JS, et al. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:134–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa Y, Maeda S, Nakagawa H, Hikiba Y, Shibata W, Sakamoto K, Yanai A, Hirata Y, Ogura K, Muto S, et al. Effectiveness of IkappaB kinase inhibitors in murine colitis-associated tumorigenesis. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:935–943. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heusinkveld M, van der Burg SH. Identification and manipulation of tumor associated macrophages in human cancers. J Transl Med. 2011;9:216. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heusinkveld M, de Vos van Steenwijk PJ, Goedemans R, Ramwadhdoebe TH, Gorter A, Welters MJ, van Hall T, van der Burg SH. M2 macrophages induced by prostaglandin E2 and IL-6 from cervical carcinoma are switched to activated M1 macrophages by CD4+ Th1 cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:1157–1165. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraga T, Williams PJ, Ueda A, Tamura D, Yoneda T. Zoledronic acid inhibits visceral metastases in the 4T1/luc mouse breast cancer model. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4559–4567. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Van Arsdall M, Tedjarati S, McCarty M, Wu W, Langley R, Fidler IJ. Contributions of stromal metalloproteinase-9 to angiogenesis and growth of human ovarian carcinoma in mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1134–1142. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.15.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hume DA, MacDonald KP. Therapeutic applications of macrophage colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) and antagonists of CSF-1 receptor (CSF-1R) signaling. Blood. 2011;119:1810–1820. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-379214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwu P. Treating cancer by targeting the immune system. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:779–781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1006416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imtiyaz HZ, Williams EP, Hickey MM, Patel SA, Durham AC, Yuan LJ, Hammond R, Gimotty PA, Keith B, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha regulates macrophage function in mouse models of acute and tumor inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2699–2714. doi: 10.1172/JCI39506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji RC. Macrophages are important mediators of either tumor- or inflammation-induced lymphangiogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;69:897–914. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0848-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce JA, Pollard JW. Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:239–252. doi: 10.1038/nrc2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jubb AM, Soilleux EJ, Turley H, Steers G, Parker A, Low I, Blades J, Li JL, Allen P, Leek R, et al. Expression of vascular notch ligand delta-like 4 and inflammatory markers in breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2019–2028. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakinoki K, Nakamoto Y, Kagaya T, Tsuchiyama T, Sakai Y, Nakahama T, Mukaida N, Kaneko S. Prevention of intrahepatic metastasis of liver cancer by suicide gene therapy and chemokine ligand 2/monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 delivery in mice. J Gene Med. 2010;12:1002–1013. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambayashi T, Alexander HR, Fong M, Strassmann G. Potential involvement of IL-10 in suppressing tumor-associated macrophages. Colon-26-derived prostaglandin E2 inhibits TNF-alpha release via a mechanism involving IL-10. J Immunol. 1995;154:3383–3390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Modlin RL, Moy RL, Dubinett SM, McHugh T, Nickoloff BJ, Uyemura K. IL-10 production in cutaneous basal and squamous cell carcinomas. A mechanism for evading the local T cell immune response. J Immunol. 1995;155:2240–2247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Takahashi H, Lin WW, Descargues P, Grivennikov S, Kim Y, Luo JL, Karin M. Carcinoma-produced factors activate myeloid cells through TLR2 to stimulate metastasis. Nature. 2009;457:102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature07623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles HJ, Harris AL. Macrophages and the hypoxic tumour microenvironment. Front Biosci. 2007;12:4298–4314. doi: 10.2741/2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo ML, Duncavage EJ, Mathew R, den Besten W, Pei D, Naeve D, Yamamoto T, Cheng C, Sherr CJ, Roussel MF. Arf induces p53-dependent and -independent anti-proliferative genes. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1046–1053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurahara H, Takao S, Maemura K, Mataki Y, Kuwahata T, Maeda K, Sakoda M, Iino S, Ishigami S, Ueno S, et al. M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophage infiltration of regional lymph nodes is associated with nodal lymphangiogenesis and occult nodal involvement in pN0 pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2012;42:155–159. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318254f2d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamagna C, Aurrand-Lions M, Imhof BA. Dual role of macrophages in tumor growth and angiogenesis. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:705–713. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1105656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang R, Patel D, Morris JJ, Rutschman RL, Murray PJ. Shaping gene expression in activated and resting primary macrophages by IL-10. J Immunol. 2002;169:2253–2263. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence T, Gilroy DW, Colville-Nash PR, Willoughby DA. Possible new role for NF-kappaB in the resolution of inflammation. Nat Med. 2001;7:1291–1297. doi: 10.1038/nm1201-1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavy O. Immunotherapy: Stopping monocytes in their tracks. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:715. doi: 10.1038/nri3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leek RD, Lewis CE, Whitehouse R, Greenall M, Clarke J, Harris AL. Association of macrophage infiltration with angiogenesis and prognosis in invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4625–4629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leek RD, Hunt NC, Landers RJ, Lewis CE, Royds JA, Harris AL. Macrophage infiltration is associated with VEGF and EGFR expression in breast cancer. J Pathol. 2000;190:430–436. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200003)190:4<430::AID-PATH538>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leek RD, Talks KL, Pezzella F, Turley H, Campo L, Brown NS, Bicknell R, Taylor M, Gatter KC, Harris AL. Relation of hypoxia-inducible factor-2 alpha (HIF-2 alpha) expression in tumor-infiltrative macrophages to tumor angiogenesis and the oxidative thymidine phosphorylase pathway in Human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1326–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuschner F, Dutta P, Gorbatov R, Novobrantseva TI, Donahoe JS, Courties G, Lee KM, Kim JI, Markmann JF, Marinelli B, et al. Therapeutic siRNA silencing in inflammatory monocytes in mice. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:1005–1010. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckman SP, Hughes DE, Coxon FP, Graham R, Russell G, Rogers MJ. Nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates inhibit the mevalonate pathway and prevent post-translational prenylation of GTP-binding proteins, including Ras. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:581–589. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.4.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luedde T, Beraza N, Kotsikoris V, van Loo G, Nenci A, De Vos R, Roskams T, Trautwein C, Pasparakis M. Deletion of NEMO/IKKgamma in liver parenchymal cells causes steatohepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:119–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald KP, Palmer JS, Cronau S, Seppanen E, Olver S, Raffelt NC, Kuns R, Pettit AR, Clouston A, Wainwright B, et al. An antibody against the colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor depletes the resident subset of monocytes and tissue-and tumor-associated macrophages but does not inhibit inflammation. Blood. 2010;116:3955–3963. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-266296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda S, Kamata H, Luo JL, Leffert H, Karin M. IKKbeta couples hepatocyte death to cytokine-driven compensatory proliferation that promotes chemical hepatocarcinogenesis. Cell. 2005;121:977–990. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud SM, Lee AH, Paish EC, Macmillan RD, Ellis IO, Green AR. Tumour-infiltrating macrophages and clinical outcome in breast cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2011;65:159–163. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A. Cancer: inflaming metastasis. Nature. 2009;457:36–37. doi: 10.1038/457036b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A, Sica A. Macrophages, innate immunity and cancer: balance, tolerance, and diversity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, Allavena P, Sica A. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:549–555. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelli F, Hamilton T, Silver DP, Sharpless NE, Bardeesy N, Rokas M, DePinho RA, Livingston DM, Grossman SR. p19ARF targets certain E2F species for degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4455–4460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081061398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez FO, Helming L, Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages: an immunologic functional perspective. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:451–483. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medrek C, Ponten F, Jirstrom K, Leandersson K. The presence of tumor associated macrophages in tumor stroma as a prognostic marker for breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:306. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monkkonen H, Auriola S, Lehenkari P, Kellinsalmi M, Hassinen IE, Vepsalainen J, Monkkonen J. A new endogenous ATP analog (ApppI) inhibits the mitochondrial adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT) and is responsible for the apoptosis induced by nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:437–445. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O’Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau MF, Guillet C, Massin P, Chevalier S, Gascan H, Basle MF, Chappard D. Comparative effects of five bisphosphonates on apoptosis of macrophage cells in vitro. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73:718–723. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Movahedi K, Laoui D, Gysemans C, Baeten M, Stange G, Van den Bossche J, Mack M, Pipeleers D, In’t Veld P, De Baetselier P, et al. Different tumor microenvironments contain functionally distinct subsets of macrophages derived from Ly6C(high) monocytes. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5728–5739. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtar RA, Moore AP, Nseyo O, Baehner FL, Au A, Moore DH, Twomey P, Campbell MJ, Esserman LJ. Elevated PCNA+ tumor-associated macrophages in breast cancer are associated with early recurrence and non-Caucasian ethnicity. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011a;130:635–644. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1646-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy GR. Metastasis to bone: causes, consequences and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:584–593. doi: 10.1038/nrc867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch C, Lewis CE. Macrophage migration and gene expression in response to tumor hypoxia. Int J Cancer. 2005;117:701–708. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch C, Giannoudis A, Lewis CE. Mechanisms regulating the recruitment of macrophages into hypoxic areas of tumors and other ischemic tissues. Blood. 2004;104:2224–2234. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch C, Muthana M, Coffelt SB, Lewis CE. The role of myeloid cells in the promotion of tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:618–631. doi: 10.1038/nrc2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Obstacles and opportunities for understanding macrophage polarization. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89:557–563. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0710409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naugler WE, Sakurai T, Kim S, Maeda S, Kim K, Elsharkawy AM, Karin M. Gender disparity in liver cancer due to sex differences in MyD88-dependent IL-6 production. Science. 2007;317:121–124. doi: 10.1126/science.1140485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeid E, Nanda R, Fu YX, Olopade OI. The role of tumor-associated macrophages in breast cancer progression (review) Int J Oncol. 2013;43:5–12. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikarsky E, Porat RM, Stein I, Abramovitch R, Amit S, Kasem S, Gutkovich-Pyest E, Urieli-Shoval S, Galun E, Ben-Neriah Y. NF-kappaB functions as a tumour promoter in inflammation-associated cancer. Nature. 2004;431:461–466. doi: 10.1038/nature02924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard JW. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:71–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard JW. Trophic macrophages in development and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:259–270. doi: 10.1038/nri2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz J, Schreiber-Agus N, Liegeois NJ, Silverman A, Alland L, Chin L, Potes J, Chen K, Orlow I, Lee HW, et al. The Ink4a tumor suppressor gene product, p19Arf, interacts with MDM2 and neutralizes MDM2's inhibition of p53. Cell. 1998;92:713–723. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81400-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porta C, Riboldi E, Sica A. Mechanisms linking pathogens-associated inflammation and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2011;305:250–262. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pylayeva-Gupta Y, Lee KE, Hajdu CH, Miller G, Bar-Sagi D. Oncogenic Kras-induced GM-CSF production promotes the development of pancreatic neoplasia. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:836–847. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Y, Gregory MA, Li Z, Brousal JP, West K, Hann SR. p19ARF directly and differentially controls the functions of c-Myc independently of p53. Nature. 2004;431:712–717. doi: 10.1038/nature02958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qing W, Fang WY, Ye L, Shen LY, Zhang XF, Fei XC, Chen X, Wang WQ, Li XY, Xiao JC, et al. Density of tumor-associated macrophages correlates with lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2012;22:905–910. doi: 10.1089/thy.2011.0452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raica M, Cimpean AM, Ribatti D. Angiogenesis in pre-malignant conditions. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1924–1934. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin EB, Giaccia AJ. The role of hypoxia-inducible factors in tumorigenesis. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:678–685. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restifo NP, Dudley ME, Rosenberg SA. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer: harnessing the T cell response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:269–281. doi: 10.1038/nri3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rius J, Guma M, Schachtrup C, Akassoglou K, Zinkernagel AS, Nizet V, Johnson RS, Haddad GG, Karin M. NF-kappaB links innate immunity to the hypoxic response through transcriptional regulation of HIF-1alpha. Nature. 2008;453:807–811. doi: 10.1038/nature06905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodan GA, Fleisch HA. Bisphosphonates: mechanisms of action. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2692–2696. doi: 10.1172/JCI118722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolny C, Mazzone M, Tugues S, Laoui D, Johansson I, Coulon C, Squadrito ML, Segura I, Li X, Knevels E, et al. HRG inhibits tumor growth and metastasis by inducing macrophage polarization and vessel normalization through downregulation of PlGF. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senaratne SG, Pirianov G, Mansi JL, Arnett TR, Colston KW. Bisphosphonates induce apoptosis in human breast cancer cell lines. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:1459–1468. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senaratne SG, Mansi JL, Colston KW. The bisphosphonate zoledronic acid impairs Ras membrane [correction of impairs membrane] localisation and induces cytochrome c release in breast cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:1479–1486. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shantsila E, Wrigley B, Tapp L, Apostolakis S, Montoro-Garcia S, Drayson MT, Lip GY. Immunophenotypic characterization of human monocyte subsets: possible implications for cardiovascular disease pathophysiology. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:1056–1066. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P, Wagner K, Wolchok JD, Allison JP. Novel cancer immunotherapy agents with survival benefit: recent successes and next steps. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:805–812. doi: 10.1038/nrc3153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpless NE. INK4a/ARF: a multifunctional tumor suppressor locus. Mutat Res. 2005;576:22–38. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z, Seppanen H, Vainionpaa S, Ye Y, Wang S, Mustonen H, Puolakkainen P. IL10, IL11, IL18 are differently expressed in CD14+ TAMs and play different role in regulating the invasion of gastric cancer cells under hypoxia. Cytokine. 2012;59:352–357. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirabe K, Mano Y, Muto J, Matono R, Motomura T, Toshima T, Takeishi K, Uchiyama H, Yoshizumi T, Taketomi A, et al. Role of tumor-associated macrophages in the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Surg Today. 2011;42:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00595-011-0058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sica A, Saccani A, Bottazzi B, Polentarutti N, Vecchi A, van Damme J, Mantovani A. Autocrine production of IL-10 mediates defective IL-12 production and NF-kappa B activation in tumor-associated macrophages. J Immunol. 2000;164:762–767. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siveen KS, Kuttan G. Role of macrophages in tumour progression. Immunol Lett. 2009;123:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele RJ, Brown M, Eremin O. Characterisation of macrophages infiltrating human mammary carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 1985;51:135–138. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1985.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern PH. Antiresorptive agents and osteoclast apoptosis. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:1087–1096. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetler-Stevenson WG, Yu AE. Proteases in invasion: matrix metalloproteinases. Semin Cancer Biol. 2001;11:143–152. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2000.0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stott FJ, Bates S, James MC, McConnell BB, Starborg M, Brookes S, Palmero I, Ryan K, Hara E, Vousden KH, et al. The alternative product from the human CDKN2A locus, p14(ARF), participates in a regulatory feedback loop with p53 and MDM2. EMBO J. 1998;17:5001–5014. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.17.5001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stresing V, Daubine F, Benzaid I, Monkkonen H, Clezardin P. Bisphosphonates in cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2007;257:16–35. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto M, Kuo ML, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ. Nucleolar Arf tumor suppressor inhibits ribosomal RNA processing. Mol Cell. 2003;11:415–424. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain SM, Arezzo JC. Neuropathy associated with microtubule inhibitors: diagnosis, incidence, and management. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2008;6:455–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiyama T, Nakamoto Y, Sakai Y, Mukaida N, Kaneko S. Optimal amount of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 enhances antitumor effects of suicide gene therapy against hepatocellular carcinoma by M1 macrophage activation. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:2075–2082. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00951.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui S, Yasuda K, Suzuki K, Tahara K, Higashi H, Era S. Macrophage infiltration and its prognostic implications in breast cancer: the relationship with VEGF expression and microvessel density. Oncol Rep. 2005;14:425–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Pluijm G, Vloedgraven H, van Beek E, van der Wee-Pals L, Lowik C, Papapoulos S. Bisphosphonates inhibit the adhesion of breast cancer cells to bone matrices in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:698–705. doi: 10.1172/JCI118841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicari AP, Chiodoni C, Vaure C, Ait-Yahia S, Dercamp C, Matsos F, Reynard O, Taverne C, Merle P, Colombo MP, et al. Reversal of tumor-induced dendritic cell paralysis by CpG immunostimulatory oligonucleotide and anti-interleukin 10 receptor antibody. J Exp Med. 2002;196:541–549. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonderheide RH, Glennie MJ. Agonistic CD40 antibodies and cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:1035–1043. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang FQ, So J, Reierstad S, Fishman DA. Matrilysin (MMP-7) promotes invasion of ovarian cancer cells by activation of progelatinase. Int J Cancer. 2005;114:19–31. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter MC, Coleman RE. Bisphosphonates in breast cancer: teaching an old dog new tricks. Curr Opin Oncol. 2009;21:499–506. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328331c794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, Postow MA, Rizvi NA, Lesokhin AM, Segal NH, Ariyan CE, Gordon RA, Reed K, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:122–133. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Xu JB, He YL, Peng JJ, Zhang XH, Chen CQ, Li W, Cai SR. Tumor-associated macrophages promote angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis of gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106:462–468. doi: 10.1002/jso.23110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye XZ, Xu SL, Xin YH, Yu SC, Ping YF, Chen L, Xiao HL, Wang B, Yi L, Wang QL, et al. Tumor-associated microglia/macrophages enhance the invasion of glioma stem-like cells via TGF-beta1 signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2012;189:444–453. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao JJ, Pan K, Wang W, Chen JG, Wu YH, Lv L, Li JJ, Chen YB, Wang DD, Pan QZ, et al. The prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating neutrophils in gastric adenocarcinoma after resection. PLoS One. 2012a;7:e33655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q, Kuang DM, Wu Y, Xiao X, Li XF, Li TJ, Zheng L. Activated CD69+ T cells foster immune privilege by regulating IDO expression in tumor-associated macrophages. J Immunol. 2012b;188:1117–1124. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]