Abstract

A thoracotomy is an incision into the pleural space of the chest. It is performed by surgeons (or emergency physicians under certain circumstances) to gain access to the thoracic organs, most commonly the heart, the lungs, or the esophagus, or for access to the thoracic aorta or the anterior spine. This surgical procedure is a major surgical maneuver it is the first step in many thoracic surgeries including lobectomy or pneumonectomy for lung cancer and as such requires general anesthesia with endotracheal tube insertion and mechanical ventilation, rigid bronchoscope can be also used if necessary. Thoracotomies are thought to be one of the most difficult surgical incisions to deal with post-operatively, because they are extremely painful and the pain can prevent the patient from breathing effectively, leading to atelectasis or pneumonia. In the current review we will present the steps of this procedure.

Keywords: Pneumothorax, thoracotomy, surgery

Introduction

Open thoracotomy with pleural abrasion was first described by Tyson and Grandall in 1941 for treatment of pneumothorax (1). Later, in 1956 parietal pleurectomy was introduced by Gaensler. Less invasive procedures, like axillary thoracotomy became more common during the past decades, but the main purpose, the resection of bullae and blebs and the pleurodesis through adhesions of visceral pleura and chest wall remained the same.

Open thoracotomy is considered a major surgical maneuver, requiring general anesthesia and endotracheal tube (single or double lumen) insertion, with the patient under mechanical ventilation for the duration of the procedure. One very important aspect that needs to be considered is pain management, requiring systemic and often epidural analgesia (2).

Positioning

Proper positioning of the patient in order to provide adequate exposure of the thoracic cavity after the incision is of great importance. Thoracotomies are performed with the patient in the lateral decubitus position. Care needs to be taken for injuries that might happen during positioning, due to nerve stretching or compression at pressure points.

The patient is secured at the operating table with adhesive tape straps placed over the hip. The superior arm is flexed and secured with straps on a padded stand, while the lower arm lies straight on a padded arm holder, secured the same way (3). Elbows need to be padded in order to avoid compression. The legs are separated with pillows, with the lower leg flexed at the hip and the knee and the upper leg lying straight on the pillows (3). A roll may be placed under the dependent axilla to release the pressure from the branchial plexus. In order to keep the cervical in a neutral position, head must be supported with a pad (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Positioning.

After securing the patient, the operating table is flexed at the middle. This helps to widen the intercostal spaces, providing easier entrance to the pleural cavity.

Prophylaxis

As in most surgical procedures, administration of prophylactic perioperative antibiotics is indicated, prior to the skin incision, in order to minimize the risk of wound infection. Repeated doses might be required during the operation to maintain adequate levels of the drug.

Perioperative use of low-molecular-weight heparin is recommended for prophylaxis from deep venous thrombosis during the procedure. Additional prophylaxis, e.g., elastic socks might be required.

Incisions

Posterolateral thoracotomy

Posterolateral thoracotomy is the most commonly used approach for most procedures because it provides the best exposure of the thoracic cavity, and though not many surgeons prefer it, it’s still used to treat spontaneous pneumothorax (4). It is performed with the patient in lateral decubitus position as described above (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Scin incision.

The skin incision, shaped as wide “S”, is performed approximately 1 cm below the tip of the scapula, after proper sterilization of the area. It extends from the vertical midline between the medial edge of the scapula and the thoracic spine posteriorly and the anterior axillary line.

After the skin incision, subcutaneous tissue and the latissimus dorsi muscle are divided using electrocautery. Immediately below latissimus dorsi is the serratus anterior muscle, which can be divided using electrocautery, or depending on the anatomy, might only be divided from its soft tissues and thus preserved and retracted anteriorly (muscle-sparing thoracotomy), providing less post-operative pain.

The entrance to the thoracic cavity is usually accomplished through the fifth intercostal space, because it allows adequate exposure of all the lung, but the fourth or the sixth intercostal spaces might also be used if better exposure of the apical or the lower segments of the lung is required. The desired interspace is located after retraction of the scapula and counting the ribs beneath by palpation. Intercostal muscles are divided on the surface of the inferior rib, in order to avoid damage of the intercostal neurovascular bandle.

Limited lateral thoracotomy

This is accomplished with a small incision 4-8 cm in the auscultatory triangle area. Both latissimus dorsi and serratus anterior muscles may be preserved, resulting in less post-operative pain and better function of the ipsilateral shoulder and arm. Entrance to the pleural cavity is gained the same way as in posterolateral thoracotomy, through division of the intercostal muscles at their inferior margin. It facilitates small segmentectomies of the lung (e.g., blebectomy) and due to the better post-operative cosmetic result and less post-operative is commonly used by many thoracic surgeons.

Axillary thoracotomy

Performed with the patient in the lateral decubitus position with the arm abducted at 90° degrees in order to provide access to the axilla, this approach provides excellent exposure of the apical segments of the lung. It was introduced in the 1970’s and still remains one of the most classic approaches for apical lesions (5,6).

An incision 5-6 cm, from the posterior margin of the pectoralis major to the anterior margin of the latissimus dorsi is performed. These muscles are retracted providing access to the 3rd rib, above which the intercostal muscle is being divided and entrance to the thoracic cavity is obtained (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Axillary mini-thoracotomy.

Extreme care needs to be taken during this procedure to preserve the long thoracic nerve and artery because of their course through the operating plane above the ribs.

Anterior thoracotomy

This technique has the advantage of keeping the patient in supine position, thus improving the cardiopulmonary function during surgery. The ipsilateral arm is placed on an elevated arm board and the incision is made over the fourth or fifth interspace from the mid-axillary line to curve parasternally under the mammal gland. Pectoral muscles are divided with electrocautery and through the division of intercostal muscles entrance to the thoracic cavity is obtained.

Pre-operative careful planning, with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging will vastly help the surgeon to choose the correct incision, making the whole procedure much easier. Of course, the surgeon’s experience plays also an important role and many times it might be preferable to choose the type of incision he is accustomed to.

Blebectomy/bullectomy

Bullae and blebs are the most common cause of primary or secondary spontaneous pneumothorax. In order to prevent re-occurrence of pneumothorax, segments of the lung with bullae or blebs need to be resected.

After access to the thoracic cavity has been achieved, through one of the foretold incisions, the whole surface of the lung needs to be inspected thoroughly for blebs and bullae. Particular attention must be given to the apical and basal parts of the lung and the lung edges, because these are the usual places where bullae are formed.

Many times, especially in patients with repeated episodes of pneumothorax, adhesions between visceral and parietal pleura might be present, making difficult the entrance to the thoracic cavity or the mobilization of the lung. These adhesions must be carefully divided, in order to avoid damage to the lung or blood vessels.

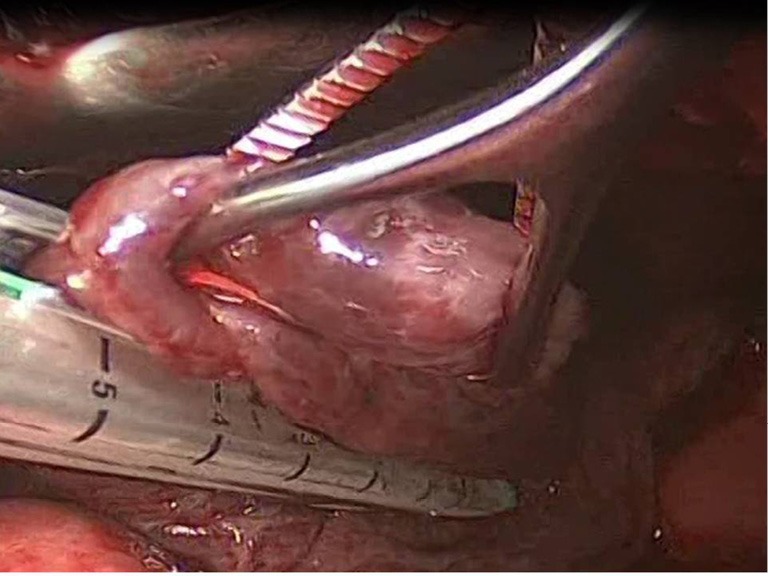

After the limits of resection are identified, excision of the abnormal lung tissue is facilitated by the use of linear cutting staplers. Depending on the size of excision and the tissue thickness, either blue or green loads may be used. The general principle followed, is to preserve as much normal lung tissue as possible, while resecting all the abnormal lung tissue. If more than one load is used, care must be taken that the stapling lines do not overlap, because air-leakage might appear. Smaller bullae and blebs may be treated with electrocautery or laser (7) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Bullectomy with the use of staplers.

All the bullae that are inspected must be excised. The same principle applies for areas of the lung that are suspicious for ruptured bullae, which might be difficult to identify. After the final excision is made, careful haemostasis takes place and the pleural cavity is filled with water, while re-expansion of the lung takes place, in order to check the stapler lines for air leak. If necessary, the staple lines may be reinforced with sutures to reduce the incidence of postoperative air leaks.

Pleurectomy/pleural abrasion

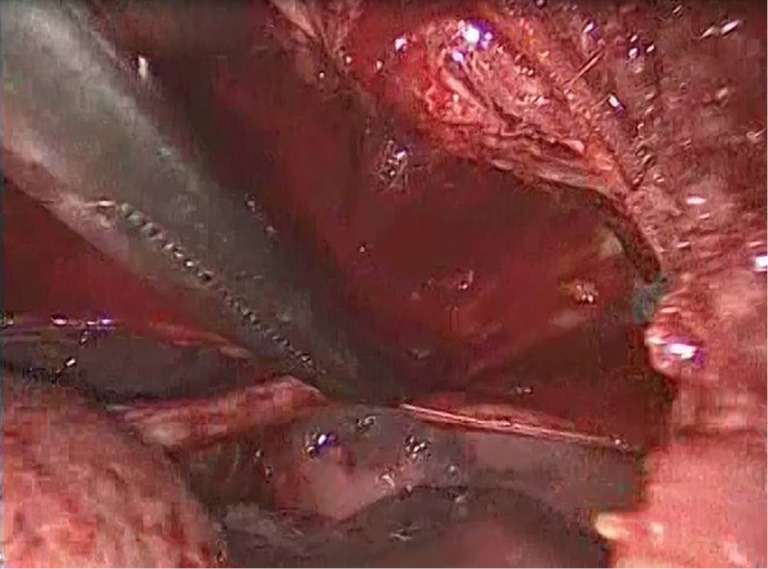

Pleurectomy is the stripping of parietal pleura. Starting at the point of the incision, the apical pleura are stripped from the chest wall with the help of a Kocher clamp and electrocautery until the internal mammal vessels, where the stripping stops, in order to avoid damage to the vessels. Haemostasis is achieved with the use of electrocautery. The rest of the parietal pleura and the visceral pleura may be abraded with dry gauze for better results (7). The point of this procedure is to achieve pleurodesis, e.g., symphysis between the visceral pleura and the chest wall, through inflammation of the visceral pleura, minimizing the recurrence of pneumothorax.

In the past, there was a lot of controversy between surgeons as to which method, pleurectomy or pleurodesis with pleural abrasion, had better results in recurrence prevention. As later studies showed, the best way to minimize the risk of pneumothorax recurrence is a combination of the two methods (5,8) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Parietal pleurectomy.

At the end of the procedure, two chest tubes are placed through different small incisions inferior to the starting incision and they are connected to a Bulau device. Usually they are guided to the apex of the lung. The lung is then re-expanded, final checks for air leaks or hemorrhage are made and the incision is closed layer by layer. First the intercostal space is closed with separate thick absorbable pericostal sutures. Then the serratus anterior and the latissimus dorsi are sutured separately, with constant absorbable suture, following the subcutaneous tissue. The skin is closed last either with sutures or surgical clips. The chest tubes remain post-operatively until any possible air leaks stop and the lung remains expanded in follow-up X-rays.

As it was mentioned above, open thoracotomy is a common surgical procedure for treating pneumothorax, although the past years more minimally invasive techniques, like VATS, have gained ground. The most important advantage of open thoracotomy and parietal pleurectomy, according to several meta-analyses of studies, is that they have the lowest pneumothorax recurrence rate (approximately 0-1%) (9-11).

Main disadvantages of the procedure are the post-operative pain and the longer hospital stay (3,12). Complications [0-16% according to different series (7)] of open thoracotomy for pneumothorax include blood loss, prolonged air leaks, pneumonia (7), infection of the trauma, haematoma, infection of the chest tubes resulting in possible empyema (13). Another issue that might be of concern is the cost. Compared to VATS, open posterolateral thoracotomy costs less as a procedure, but due to longer hospital stay and the need for continuous analgesia, the total cost is higher than the one with VATS. This might not be true, though, about the axillary mini-thoracotomy approach, as there are studies that show almost the same analgesic consumption, chest tube drainage duration and hospital stay with the VATS approach (5). Some other studies show that despite the slight bigger hospital stay for patients that undergo axillary mini-thoracotomy, the cost of the procedure is not that different that VATS (14).

There are numerous studies in the literature that report zero mortality for axillary minithoracotomy (9,15-17). Other series report almost 1% mortality for patients with lung disease, e.g., COPD, emphysema, and pneumothorax, mainly due to the worsening of the underlying lung disease (18-35). Radical excision of all the bullae, if that is possible, accompanied by pleuralabrasion and/or pleurectomy show the most promising results for these patients (36-55). The procedure appears to have equal safety and efficiency with other more invasive open procedures and VATS, for the treatment of pneumothorax and might provide the results in cases where there is contraindication for other minimally invasive techniques (47,56-63).

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Joe L, Gordin F, Parker RH. Spontaneous pneumothorax with Pneumocystis carinii infection. Occurrence in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Intern Med 1986;146:1816-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Passlick B, Born C, Häussinger K, et al. Efficiency of video-assisted thoracic surgery for primary and secondary spontaneous pneumothorax. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;65:324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dürrleman N, Massard G. Posterolateral thoracotomy. Multimed Man Cardiothorac Surg 2006;2006:mmcts.2005.001453. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Nkere UU, Kumar RR, Fountain SW, et al. Surgical management of spontaneous pneumothorax. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1994;42:45-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim KH, Kim HK, Han JY, et al. Transaxillary minithoracotomy versus video-assisted thoracic surgery for spontaneous pneumothorax. Ann Thorac Surg 1996;61:1510-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simansky DA, Yellin A. Pleural abrasion via axillary thoracotomy in the era of video assisted thoracic surgery. Thorax 1994;49:922-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tschopp JM, Rami-Porta R, Noppen M, et al. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: state of the art. Eur Respir J 2006;28:637-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansen AK, Nielsen PH, Møller NG, et al. Operative pleurodesis in spontaneous pneumothorax. Indications and results. Scand J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1989;23:279-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freixinet JL, Canalís E, Juliá G, et al. Axillary thoracotomy versus videothoracoscopy for the treatment of primary spontaneous pneumothorax. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;78:417-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu HP, Lin PJ, Hsieh MJ, et al. Thoracoscopic surgery as a routine procedure for spontaneous pneumothorax. Results from 82 patients. Chest 1995;107:559-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacDuff A, Arnold A, Harvey J, et al. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax 2010;65:ii18-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Penketh AR, Knight RK, Hodson ME, et al. Management of pneumothorax in adults with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 1982;37:850-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brooks JW. Open thoracotomy in the management of spontaneous pneumothorax. Ann Surg 1973;177:798-805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hyland MJ, Ashrafi AS, Crépeau A, et al. Is video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery superior to limited axillary thoracotomy in the management of spontaneous pneumothorax? Can Respir J 2001;8:339-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Czerny M, Salat A, Fleck T, et al. Lung wedge resection improves outcome in stage I primary spontaneous pneumothorax. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;77:1802-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falcoz PE, Binquet C, Clement F, et al. Management of the second episode of spontaneous pneumothorax: a decision analysis. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;76:1843-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massard G, Thomas P, Wihlm JM. Minimally invasive management for first and recurrent pneumothorax. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;66:592-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Körner H, Andersen KS, Stangeland L, et al. Surgical treatment of spontaneous pneumothorax by wedge resection without pleurodesis or pleurectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1996;10:656-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isaka M, Asai K, Urabe N.Surgery for secondary spontaneous pneumothorax: risk factors for recurrence and morbidity. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2013;17:247-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kioumis IP, Zarogoulidis K, Huang H, et al. Pneumothorax in cystic fibrosis. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S480-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuhajda I, Zarogoulidis K, Kougioumtzi I, et al. Tube thoracostomy; chest tube implantation and follow up. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S470-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manika K, Kioumis I, Zarogoulidis K, et al. Pneumothorax in sarcoidosis. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S466-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuhajda I, Zarogoulidis K, Kougioumtzi I, et al. Penetrating trauma. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S461-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Visouli AN, Zarogoulidis K, Kougioumtzi I, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S448-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang Y, Huang H, Li Q, et al. Transbronchial lung biopsy and pneumothorax. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S443-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Terzi E, Zarogoulidis K, Kougioumtzi I, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome and pneumothorax. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S435-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boskovic T, Stojanovic M, Stanic J, et al. Pneumothorax after transbronchial needle biopsy. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S427-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Z, Huang H, Li Q, et al. Pneumothorax: observation. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S421-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang Y, Huang H, Li Q, et al. Approach of the treatment for pneumothorax. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S416-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Browning RF, Parrish S, Sarkar S, et al. Bronchoscopic interventions for severe COPD. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S407-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Machairiotis N, Kougioumtzi I, Dryllis G, et al. Laparoscopy induced pneumothorax. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S404-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ouellette DR, Parrish S, Browning RF, et al. Unusual causes of pneumothorax. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S392-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parrish S, Browning RF, Turner JF, Jr, et al. The role for medical thoracoscopy in pneumothorax. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S383-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terzi E, Zarogoulidis K, Kougioumtzi I, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection and pneumothorax. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S377-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zarogoulidis P, Kioumis I, Pitsiou G, et al. Pneumothorax: from definition to diagnosis and treatment. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S372-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsakiridis K, Mpakas A, Kesisis G, et al. Lung inflammatory response syndrome after cardiac-operations and treatment of lornoxicam. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S78-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsakiridis K, Zarogoulidis P, Vretzkakis G, et al. Effect of lornoxicam in lung inflammatory response syndrome after operations for cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S7-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Argiriou M, Kolokotron SM, Sakellaridis T, et al. Right heart failure post left ventricular assist device implantation. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S52-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Madesis A, Tsakiridis K, Zarogoulidis P, et al. Review of mitral valve insufficiency: repair or replacement. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S39-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siminelakis S, Kakourou A, Batistatou A, et al. Thirteen years follow-up of heart myxoma operated patients: what is the appropriate surgical technique? J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S32-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foroulis CN, Kleontas A, Karatzopoulos A, et al. Early reoperation performed for the management of complications in patients undergoing general thoracic surgical procedures. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S21-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nikolaos P, Vasilios L, Efstratios K, et al. Therapeutic modalities for Pancoast tumors. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S180-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koutentakis M, Siminelakis S, Korantzopoulos P, et al. Surgical management of cardiac implantable electronic device infections. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S173-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spyratos D, Zarogoulidis P, Porpodis K, et al. Preoperative evaluation for lung cancer resection. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S162-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Porpodis K, Zarogoulidis P, Spyratos D, et al. Pneumothorax and asthma. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S152-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Panagopoulos N, Leivaditis V, Koletsis E, et al. Pancoast tumors: characteristics and preoperative assessment. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S108-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Visouli AN, Darwiche K, Mpakas A, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax: a rare entity? Report of 5 cases and review of the literature. J Thorac Dis 2012;4:17-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zarogoulidis P, Chatzaki E, Hohenforst-Schmidt W, et al. Management of malignant pleural effusion by suicide gene therapy in advanced stage lung cancer: a case series and literature review. Cancer Gene Ther 2012;19:593-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Papaioannou M, Pitsiou G, Manika K, et al. COPD assessment test: a simple tool to evaluate disease severity and response to treatment. COPD 2014;11:489-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boskovic T, Stanic J, Pena-Karan S, et al. Pneumothorax after transthoracic needle biopsy of lung lesions under CT guidance. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S99-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Papaiwannou A, Zarogoulidis P, Porpodis K, et al. Asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome (ACOS): current literature review. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S146-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zarogoulidis P, Porpodis K, Kioumis I, et al. Experimentation with inhaled bronchodilators and corticosteroids. Int J Pharm 2014;461:411-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bai C, Huang H, Yao X, et al. Application of flexible bronchoscopy in inhalation lung injury. Diagn Pathol 2013;8:174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zarogoulidis P, Kioumis I, Porpodis K, et al. Clinical experimentation with aerosol antibiotics: current and future methods of administration. Drug Des Devel Ther 2013;7:1115-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zarogoulidis P, Pataka A, Terzi E, et al. Intensive care unit and lung cancer: when should we intubate? J Thorac Dis 2013;5:S407-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hohenforst-Schmidt W, Petermann A, Visouli A, et al. Successful application of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation due to pulmonary hemorrhage secondary to granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Drug Des Devel Ther 2013;7:627-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zarogoulidis P, Kontakiotis T, Tsakiridis K, et al. Difficult airway and difficult intubation in postintubation tracheal stenosis: a case report and literature review. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2012;8:279-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zarogoulidis P, Tsakiridis K, Kioumis I, et al. Cardiothoracic diseases: basic treatment. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kolettas A, Grosomanidis V, Kolettas V, et al. Influence of apnoeic oxygenation in respiratory and circulatory system under general anaesthesia. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S116-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Turner JF, Quan W, Zarogoulidis P, et al. A case of pulmonary infiltrates in a patient with colon carcinoma. Case Rep Oncol 2014;7:39-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Machairiotis N, Stylianaki A, Dryllis G, et al. Extrapelvic endometriosis: a rare entity or an under diagnosed condition? Diagn Pathol 2013;8:194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsakiridis K, Zarogoulidis P.An interview between a pulmonologist and a thoracic surgeon-Pleuroscopy: the reappearance of an old definition. J Thorac Dis 2013;5:S449-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huang H, Li C, Zarogoulidis P, et al. Endometriosis of the lung: report of a case and literature review. Eur J Med Res 2013;18:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]