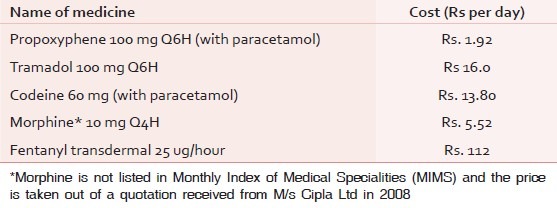

On 23rd May 2013, the Government of India banned the analgesic dextrpropoxyphene for human use.[1] With that one act, all over the country, the pain burden must have increased steeply because dextropropoxyphene, the effective and affordable analgesic belonging to step II of the World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder, was among the very few step II analgesics available in India. It was also the cheapest, the few available alternatives being many times more expensive. This ban has to be viewed in the context of the burden of pain in India. The annual incidence of cancer is about one million new cases a year, out of which 80% present in Stage III and IV. There are around 2.4 million people with cancer in India. Two-thirds of them, about 1.6 million, are likely to be in pain.[2] About 2.09 million people live with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)[3] Pain occurs in almost 25% of otherwise asymptomatic, 40–50% of ambulatory, and over 80% of hospitalized patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)[4] Almost 43% of patients with heart failure have pain.[5] Only a tiny fraction of the needy has access to analgesics of step III of the ladder. Various authors, mostly working with cancer statistics alone, have quoted figures as variable as 0.4–4%, but even if we take the best of them, it is clear that the vast majority of the needy do not have access to morphine, the only orally available step III analgesic in the country.[6] Step II analgesics could offer some pain relief to them, which would be adequate for some and inadequate for others. Poverty being rampant in India, affordability is indeed a major factor. Table 1 gives a comparative cost of step II analgesics in India. Among people who have been further impoverished by disease and treatment, it is obvious how important it is to have low-cost analgesics. In the context that other countries have banned propoxyphene, it is important to see whether the ban is justifiable in India—to see the consequence of the ban on the pain burden in the country and whether its potential hazards justify that additional burden. It is also necessary to go into the issue whether the available evidence against propoxyphene is reliable, particularly in the background of the interests of the pharmaceutical industry which stands to benefit if the vast market in India replaces propoxyphene with other medicines that are several times more expensive.[7,8]

Table 1.

The relative costs of the only available opioid analgesics that can be used in cancer pain

WHY WAS PROPOXYPHENE BANNED IN OTHER COUNTRIES?

In 2005, UK decided to phase dextropropoxyphene out, saying “There is no robust evidence that efficacy of this combination product is superior to full-strength paracetamol alone either in acute or chronic use.”[9] To the average reader, this naturally conveys the message that the combination is only as effective as paracetamol. The subtlety of the wording would be lost on many. Of course there is no “robust” evidence—there is never enough for many analgesics because pain is not easily measurable and because good studies are difficult anyway in conditions like advanced malignancy. Such weak evidence has led a reviewer to declare that “Propoxyphene analgesia was equated with that of merely acetaminophen or aspirin independently.”[10] The European Medicine Agency banned dextropropoxyphene in 2009 and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2010.[11] The main reason for the ban in the US was its potential cardio-toxicity and deaths related to overdose and suicides. These studies have mostly looked at its misuse as a recreational drug or in multiple-drug toxicity, not its use in persistent pain.[12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] A survey in the US conducted from 1969 through mid-1983 covering 27 medical examiner or coroner offices across the US and Canada confirmed the findings of the earlier studies that a high proportion of the deaths associated with propoxyphene are suicides and in most cases, the deceased were victims of multiple-drug toxicity. More than 90% of cases involved persons between the ages of 20 and 40 years. There were very few instances of pediatric, adolescent, or older adult deaths associated with propoxyphene.[21,22,23] Severe, non-malignant pain affects a large proportion of adults. Optimal treatment is not clear, and opioids are an important option for analgesia. However, there is relatively little information about the comparative safety of different opioids.[24] There are no studies to look at its use, efficacy, comparison to other analgesics, misuse or deaths caused in the population in palliative care or in chronic, malignant pain,[25] or to show the pattern of prescription and use for dextropropoxyphene in India. The preferred agents of suicide in India are different—organophosphorous pesticides, hanging, and burns being the most common.[26] Banning of insecticides, matches, and ropes would be more reasonable than banning dextropropoxyphene.

Most studies about efficacy of dextropropoxyphene listed in PubMed have compared dextropropoxyphene to tramadol[27,28] and mention that many other safer and more efficacious drugs than propoxyphene are available. Even if it were true, there are a number of effective opioid analgesics available in the western countries; but in India, effective and affordable alternatives are not there. A study on patients in the UK using dextropropoxyphene for chronic non-malignant pain has shown that not all patients found the alternatives satisfactory.[29] Difficulties in the estimation and interpretation of dextropropoxyphene and norpropoxyphene analyses have added to the controversy concerning the toxicity of these compounds. As dextropropoxyphene and norpropoxyphene are often taken in overdose with other drugs, their blood concentrations must be interpreted in the context of careful identification and quantitation of such agents. The present availability of accurate methods for measurement of parent drug and metabolite should now make anecdotal reports unsupported by analytical data entirely superfluous”.[30] At present, the main allegation against the drug seems to be its cardiotoxic potential and not clinical adverse effects. Though an overdose of dextropropoxyphene may result in cardiotoxicity,[31,32] there are many other drugs that have cardiotoxicity as a side-effect but continue to be in the market because they are useful—digitalis is the glaring example. A study of the cardiovascular complications of analgesics and glucocorticoids states that “Acetaminophen is considered by several scientific societies to be the first line analgesic treatment, particularly in case of cardiovascular risk but with caution since cardiovascular toxicity of acetaminophen cannot be totally excluded. On the other hand, the glucocorticoids need to be prescribed cautiously, at the lowest possible dose and for the shortest possible duration due to the non-negligible cardiovascular risk, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hypokalemia.”[33] The case for withdrawing dextropropoxyphene had been considered by the FDA of the US a number of times earlier too, but the evidence was not felt to be strong enough to alter the risk-benefit ratio and it continued to be used. A 10-year assessment of deaths in the US related to propoxyphene overdose concluded that “although propoxyphene cannot be regarded as a harmless drug, the study indicates a very low rate of dependency and a low potential for recreational abuse. As with other drugs, adequate warnings concerning dosage abuse and the concurrent use of alcohol and other drugs must be stressed.”

In 2010, however, the FDA after reconsidering all the old and new evidence came to the conclusion that “The findings of prolongation of the PR interval and the QT interval and widening of the QRS complex, in a dose-related manner, were present at doses within the therapeutic dosing range. The risk of toxicity for the individual patient on propoxyphene can change as a result of even a small change to the patient's metabolic status, concomitant drug use, or renal function although the other commonly prescribed analgesic drug products for use in chronic pain have toxicities that are also potentially lethal (e.g. respiratory failure and addiction with opioids). Nevertheless, the risk of these toxicities occurring can be mitigated with proper use, appropriate risk management strategies, and monitoring. However, it is not possible to monitor for, or mitigate, the risk of a fatal cardiac arrhythmia that may occur within the recommended dosing range for propoxyphene. As a result, the weight of evidence has shifted and the overall balance of risk and benefit can no longer be considered favorable. It is the conclusion of the Office of New Drugs and the Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology that propoxyphene-containing drug products should be withdrawn from the market.”

The statement accepts that

Toxicity is dose dependant

Risk of toxicity changes with metabolic status, renal function, and concomitant drug use

Other analgesics may also be potentially lethal.

One important factor was that during the voting, the FDA advisory committee voted 12 for and 14 against the continuing marketing of dextropropoxyphene.[34] The vote was thus passed with a very narrow margin.

CAN WE IMPLICITLY TRUST EVIDENCE AGAINST INEXPENSIVE DRUGS?

When we weigh the risk-benefit ratio of any drug, we have to take into consideration the fallacies with available evidence. It is a fact that the bulk of “evidence” seems to be generated out of research funded by the pharmaceutical industry. There is precious little research done with inexpensive medicines and this leads to a publication bias against inexpensive medicines. We agree with the statement that currently, there is insufficient evidence to conclude that dextropropoxyphene is inherently more toxic than codeine, or other opioids of similar efficacy, nor is there evidence that one is more effective than another.”[35] Dextropropoxyphene was the cheapest Step II opioid analgesic available in India. Its easy accessibility even in peripheral areas made it especially useful in chronic pain management, especially so in cancer. It is an unfortunate fact that almost 90% of research on drugs is funded by the pharmaceutical industry which has little interest in inexpensive drugs because it suits the interest of the industry if inexpensive drugs are pushed out of the market.[36,37] Ghost authorship in industry-initiated randomized trials is very common, and we believe that this practice serves commercial purposes.[38] With pharmaceutical companies funding the research into and testing of their own products, there is tremendous pressure on the researchers to come up with the desired results, regardless of whether the drugs really work or not. Huge bribes, threats, and the making or breaking of careers are all at stake.[39] As has been pointed out, “The greater the financial and other interests and prejudices in a scientific field, the less likely the research findings are to be true.”[40] This should warn us against knee-jerk reaction when evidence is brought to light against inexpensive medicines.

Further, “The credibility of modern science is grounded on the perception of the objectivity of its scientists, but that credibility can be undermined by financial conflicts of interest. One of every three articles in our sample has at least one author with a financial interest, and 15% of the authors in the sample had a financial interest relevant to one of their publications.”[41] The aim of any commercial establishment including pharmaceuticals is to maximize profit. Pharmaceutical companies are not especially big in terms of revenues, but they are very profitable. By February 2001, Pfizer had become the 18th largest market entity, bigger than the listed domestic equity markets of many countries, including South Africa and South Korea'[42] The WHO states that –“The total worth of the world's pharmaceuticals is about $300 billion a year with one-third market controlled by the ten biggest companies, which between themselves have a profit of about 30% from the sales of more than $10 billion a year. This obviously leads to a pressure for sales and an inherent conflict of interest between the legitimate business goals of manufacturers and the social, medical, and economic needs of providers and the public to select and use drugs in the most rational way. This is particularly true where drugs companies are the main source of information as to which products are most effective.”[43]

“Despite the relatively low prices that can be obtained on the international market, availability of essential drugs remains deficient, and over half the poorest people in Africa and Asia still do not have access to these drugs.”[44] Most of the world's poor—the ones who need these drugs most—cannot afford them because of the prohibitive costs, even in the case of life- saving medicines.

Results of published research are also not as unbiased as they ought to be, a fact supported by a number of studies. “The much-repeated argument from pharmaceutical companies, that high drug prices are mainly attributable to research costs, merits cautious scrutiny. With publicly available data, we can ascertain that costs of advertising and promotion generally much exceed research expenditure. Furthermore, industrial research usually benefits from public support, either in the form of tax breaks or as direct scientific input.”[45] “Articles with drug company support are more likely than articles without drug company support to have outcomes favoring the drug of interest”[46] and “Pharmaceutical company sponsorship of economic analyses is associated with reduced likelihood of reporting unfavorable results”[47] Research sponsored by companies is more likely to produce results favoring the company's product than that funded by other sources.[48] “The pattern of new medicines research and development reflects market opportunities rather than global public health priorities. The Global Forum for Health Research highlights the fact that only 10% of spending on research and development is directed to the health problems that account for 90% of the global disease burden—the so-called 10/90 Gap. The medicines market continues to be dominated by lifestyle-related and convenience medicines for richer populations at the expense of the medicine needs of the poor.”[49]

Inspite of the crisis that India faces in access to analgesics for severe pain, dextropropoxyphene stands banned. Developed countries could afford to take this stand with equanimity. There are plenty of alternatives, like codeine, dihydrocodeine, pethidine, buprenorphine, diamorhpine, methadone, hydromorphone, tapentadol, oxymorphone, oxycodone, available.[50,51]

But for many parts of the developing world, the axe is falling on the least-expensive opioid available for oral use.[52,53] In India, tramadol, codeine, and now buprenorphine are the only drugs available as WHO Ladder Step II analgesics. The cost is a major consideration for our countrymen where, unlike most of the western world every year, millions are pushed below the poverty line due to treatment costs alone.

The World Health Report of 2010, entitled “Health Systems Financing” stated that “the Path to Universal Coverage showed that over a billion people are unable to use the health services they need, while a 100 million people are pushed into poverty and 150 million people face financial hardship because they have to pay directly for the health services they use at the point of delivery.”[52]

The patients in India are already facing a crisis of unrelieved pain. Poor awareness, poor availability of palliative care, poor resources, and inaccessibility of opioid analgesics are already hurdles enough, without taking away one of the few inexpensive drugs that was accessible. The government must consider the plight of the millions living miserably and dying in unrelieved pain and review its decision to ban dextropropoxyphene.

Of the lot, stringent narcotic regulations restrict the availability of oral morphine to a tiny fraction of the needy. One hundred milligram of tramadol four times a day would cost twice the daily income that defines the poverty line.[54,55] What the average Indian could afford and could get is dextropropoxyphene, which anyway is not a popular drug for attempted suicide in this country; most would find a piece of rope more cost-effective and familiar.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balhara YP. Dextropropoxypheneban in India: Is there a case for reconsideration? J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2014;5:8–11. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.124406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajagopal MR, Joranson DE. India: Opioid availability. An update. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:615–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Government of India; Central Statistics Office. (2013) SAARC Development Goals; India country report 2013. Government of India, Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation. [Last accessed on 2014 May 25]. Available from: http://mospi.nic.in/mospi_new/upload/SAARC_Development_Goals_%20India_Country_Report_29aug13.pdf .

- 4.Woodruff R, Cameron D. HIV/AIDS in adults. In: Hanks G, Cherny NJ, Christakis NA, Fallon M, Kaasa S, Portenoy RK, editors. Oxford textbook of Palliative Medicine. 4th ed. Oxford University Press; 2010. p. 1205. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGavigan AD, Datta CL, Dunn FG. Palliative Care for patients with end stage stage heart failure. In: Hanks G, Cherny NJ, Christakis NA, Fallon M, Kaasa S, Portenoy RK, editors. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford United Kingdom; 2009. p. 1258. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Human Rights Watch. Unbearable Pain: India's Obligation to Ensure Palliative Care. [Last accessed on 2014 Jun 02]. Available from: http://www.hrw.org/reports/2009/10/28/unbearable-pain-0 .

- 7.Rajagopal MR, Joranson DE, Gilson AM. Medical use, misuse, and diversion of opioids in India. Lancet. 2001;358:139–43. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05322-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khosla D, Patel FD, Sharma SC. Palliative care in India: Current progress and future needs. Indian J Palliat Care. 2012;18:149–54. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.105683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.fda. gov. WITHDRAWAL OF CO-PROXAMOL PRODUCTS AND INTERIM UPDATED PRESCRIBING INFORMATION. [Last accessed on 2014 Jun 02]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/dockets/06p0090/06p-0090-sup0001-27-vol2.pdf .

- 10.Barkin RL, Barkin SJ, Barkin DS. Propoxyphene (dextropropoxyphene): A critical review of a weak opioid analgesic that should remain in antiquity. Am J Ther. 2006;13:534–42. doi: 10.1097/01.mjt.0000253850.86480.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.mhra.gov.co.uk. Medicines and healthcare products regulatory agency. “Co-proxamol to be withdrawn from the market”. [Last accessed on 2005 Jan 31]. Available from: http://www.mhra.gov.uk/index.htm .

- 12.Wetli CV, Bednarczyk LR. Deaths related to propoxyphene overdose: A ten-year assessment. South Med J. 1980;73:1205–9. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jonasson U, Jonasson B, Saldeen T, Thuen F. The prevalence of analgesics containing dextropropoxyphene or codeine in individuals suspected of driving under the influence of drugs. Forensic Sci Int. 2000;112:163–9. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(00)00247-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buckley NA, Whyte IM, Dawson AH, McManus PR, Ferguson NW. Correlations between prescriptions and drugs taken in self-poisoning. Implications for prescribers and drug regulation. Med J Aust. 1995;162:194–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonasson U, Jonasson B, Saldeen T. Middle-aged men--a risk category regarding fatal poisoning due to dextropropoxyphene and alcohol in combination. Prev Med. 2000;31:103–6. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonasson B, Jonasson U, Saldeen T. Among fatal poisonings dextropropoxyphene predominates in younger people, antidepressants in the middle aged and sedatives in the elderly. J Forensic Sci. 2000;45:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawton K, Simkin S, Gunnell D, Sutton L, Bennewith O, Turnbull P, et al. A multicentre study of coproxamol poisoning suicides based on coroners’ records in England. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;59:207–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02252.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whittington RM. Dextropropoxyphene deaths: Coroner's report. Hum Toxicol. 1984;(3 Suppl):175–85S. doi: 10.1177/096032718400300116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Afshari R, Good AM, Maxwell SR, Bateman DN. Co-proxamol overdose is associated with a 10-fold excess mortality compared with other paracetamol combination analgesics. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;60:444–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simkin S, Hawton K, Sutton L, Gunnell D, Bennewith O, Kapur N. Co-proxamol and suicide: Preventing the continuing toll of overdose deaths. QJM. 2005;98:159–70. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hci026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finkle BS. Self-poisoning with dextropropoxyphene and dextropropoxyphene compounds: The USA experience. Hum Toxicol. 1984;(3 Suppl):115–34S. doi: 10.1177/096032718400300113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawton K, Simkin S, Deeks J. Co-proxamol and suicide: A study of national mortality statistics and local non-fatal self poisonings. BMJ. 2003;326:1006–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7397.1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jonasson B, Jonasson U, Saldeen T. Suicides may be over reported and accidents underreported among fatalities due to dextropropoxyphene. J Forensic Sci. 1999;44:334–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solomon DH, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, Garneau K, Levin R, Lee J, et al. The comparative safety of opioids for nonmalignant pain in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1979–86. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel V, Ramasundarahettige C, Vijayakumar L, Thakur JS, Gajalakshmi V, Gururaj G, et al. Million Death Study Collaborators. Suicide mortality in India: A nationally representative survey. Lancet. 2012;379:2343–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60606-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Updated Epidemiological Review of Propoxyphene Safety. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pearson SA, Ringland C, Kelman C, Mant A, Lowinger J, Stark H, et al. Patterns of analgesic and anti-inflammatory medicine use by Australian veterans. Intern Med J. 2007;37:798–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis MP, Srivastava M. Demographics, assessment and management of pain in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2003;20:23–57. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200320010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ottewell L, Walker DJ. Co-proxamol: Where have all the patients gone? [Last accessed on 2014 Sep 20];Rheumatology. 2008 47:375. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem281. Available from: http://rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org/content/47/3/375.1.long . First published online: January 10, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buckley BM, Vale JA. Dextropropoxyphene poisoning: Problems with interpretation of analytical data. Hum Toxicol. 1984;(3 Suppl):95–101S. doi: 10.1177/096032718400300111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitcomb DC, Gilliam FR, 3rd, Starmer CF, Grant AO. Marked QRS complex abnormalities and sodium channel blockade by propoxyphene reversed with lidocaine. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1629–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI114340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heaney RM. Left bundle branch block associated with propoxyphene hydrochloride poisoning. Ann Emerg Med. 1983;12:780–2. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(83)80259-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dufauret-Lombard C, Bertin P. What are the cardiovascular complications of the analgesics and glucocorticoids? Presse Med. 2006;35(Suppl 1):47–51. doi: 10.1016/S0755-4982(06)74940-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharon H, Mark A. Recommendation on a regulatory decision for propoxyphene-containing products: FDA Centre for Drug Evaluation and Research; Document No 2865911. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fallon M, Cherny NI, Hanks G. Opioid Analgesic Therapy. In: Hanks G, Cherny NJ, Christakis NA, Fallon M, Kaasa S, Portenoy RK, editors. Oxford Textbook of palliative medicine. 4th edition. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2010. p. page 674. Chapter 10.1.6. [Google Scholar]

- 36.The British Journal of Psychiatry. Is academic psychiatry for sale? 2003. [Last accessed on 2014 Sept 16]. Available from: bjp.rcpsych.org/content/182/5/388.long .

- 37.Just how tainted has medicine become? Lancet. 2002;359:1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A, Johansen HK, Haahr MT, Altman DG, Chan AW. Ghost authorship in Industry-initiated randomised Trials. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Angell M. The truth about the drug companies: How they deceive us and what to do about it. Paperback edition. New York: Random House; 2004. p. 255. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ioannidis JP. Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krimsky S, Rothenberg LS, Stott P, Kyle G. Scientific journals and their authors’ financial interests: A pilot study. Psychother Psychosom. 1998;67:194–201. doi: 10.1159/000012281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henry D, Lexchin J. The pharmaceutical industry as a medicines provider. Lancet. 2002;360:1590–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.WHO Pharmaceutical Industry. [Last accessed on 2014 Jan 21]. Available from: www.who.int/trade/glossary/story073/en/

- 44.WHO Medicines Strategy: 2000:2003. Framework for action in essential Drugs and Medicines Policy. [Last accessed on 2014 Jan 21]. Available from: www.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/whozip16e/whozip16e.pdf .

- 45.Dukes MN. Accountability of the pharmaceutical industry. Lancet. 2002;360:1682–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11599-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cho MK, Bero LA. The quality of drug studies published in symposium proceedings. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:485–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-5-199603010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Friedberg M, Saffran B, Stinson TJ, Nelson W, Bennett CL. Evaluation of conflict of interest in economic analyses of new drugs used in oncology. JAMA. 1999;282:1453–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lexchin J, Bero LA, Djulbegovic B, Clark O. Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: Systematic review. BMJ. 2003;326:1167–70. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7400.1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.The World Medicines Situation: Chapter 2. Research and Development. Essential Medicines and Health Products information Portal. World Health Organisation Resource. [Last accessed on 2014 Apr 8]. Available from: who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js6160e/4.html .

- 50.MIMS. Opioid Analgesics: Approximate Potency Equivalence with Oral Morphine. [Last accessed on 2014 Sept 20]. Available from: http://www.mims.co.uk/news/1146201/opioid-analgesics-approximate-potency-equivalence-oral-morphine .

- 51.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. List of Extended-Release and Long-Acting Opioid Products Required to Have an Opioid REMS. [Last accessed on 2014 Sept 20]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm251735.htm .

- 52.Saksena P, Xu K, Evans DB. World Health Organization 2010. [Last accessed on 2014 Sep 20];Impact of out of pocket payments for treatment of Non communicable diseases in developing countries - a review of literature. Available at http://www.who.int/health_financing/documents/dp_e_11_02-ncd_finburden.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 53.Monthly Index of Medical Specialities. 10. Vol. 28. New Delhi: MIMS; 2008. pp. 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Times of India. New poverty line: Rs 32 in villages, Rs 47 in cities. [Last accessed on 2014 Sept 20]. Available from: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/New-poverty-line-Rs-32-in-villages-Rs-47.in- cities/articleshow/37920441.cms .

- 55.Planning Commission, Government of India. Methodology for identification of families living below the poverty line. 2012. Dec, [Last accessed on 2014 Sep 20]. Available from: http://planningcommission.gov.in/reports/genrep/rep_hasim1701.pdf .