Abstract

Patient: Female, 28

Final Diagnosis: Sacral stress fracture

Symptoms: Lumbosacral pain during pregnancy

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Activity modification • conservative treatment

Specialty: Orthopedics and Traumatology

Objective:

Challenging differential diagnosis

Background:

Sacral stress fracture during pregnancy is an uncommon condition with unclear pathophysiology, presenting with non-specific symptoms and clinical findings. To date, few cases have been published in the literature describing the occurrence of sacral stress fracture during pregnancy.

Case Report:

We report a 28-year-old primigravid patient who developed lumbosacral pain at the end of the second trimester. Symptoms were overlooked throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period, resulting in the development of secondary chronic gait and balance problems.

Conclusions:

Stress fracture of the sacrum should be included in the differential diagnosis of low back and sacral pain during pregnancy. Its prevalence is probably underestimated because of the lack of specificity of the symptoms. Plain radiographs are not appropriate due to radiation exclusion; magnetic resonance is the only method that can be applied safely. There is limited information on natural history but many patients are expected to have a benign course. However, misdiagnosis may lead to prolonged morbidity and the development of secondary gait abnormalities. Stress fracture of the sacrum should be included in the differential diagnosis of low back and sacral pain during pregnancy. A high index of suspicion is necessary to establish an early diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

MeSH Keywords: Fractures, Stress; Lumbosacral Region; Pregnancy Complications; Sacrum

Background

Low back and sacral pain is a common complaint during pregnancy and the post-partum period [1]. It is frequently dismissed as trivial and inevitable, and simply attributed to the lumbosacral mechanical strain due to pregnancy. However, this fact tends to overshadow less common but important causes of lumbosacral pain [2].

Sacral stress fracture during pregnancy is a very rare condition presenting with non-specific symptoms and clinical signs. The pathophysiology of the occurrence of this fracture during pregnancy remains unclear, and a differentiation between fatigue and insufficiency fracture may not be possible due to transient osteoporosis [3–5]. Despite the progression of the pain and disability throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period, symptoms are usually overlooked, resulting in the development of secondary long-term gait and balance problems.

To date, few cases have been published in the literature describing the occurrence of sacral stress fracture during pregnancy [5–8] and the immediate postpartum period. There is very limited information on sacral stress fracture during pregnancy. A high index of suspicion is necessary to establish an early diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Case Report

A 28-year-old healthy woman was referred to the orthopaedic clinic with a history of pain in the left buttock in the upright standing and walking position. Although the pain had started at the end of the second trimester of her first pregnancy, she was already 6 months postpartum at the time of the referral.

She described an initial slight discomfort over her left buttock with radiation down the back of her left leg. The pain increased within a few days until the condition made it impossible for the patient to walk without crutches. The symptoms were increased by sitting, walking and standing, whereas the pain showed significant relief during bed rest. At that stage the patient sought medical advice. The initial diagnostic impression was nonspecific pregnancy-related low back pain and radiculalgia, and the recommendation of activity modification and oral paracetamol was made.

The patient denied any history of previous fractures, eating disorder, or metabolic bone disease. There was no past history of low back pain or trauma. Oral paracetamol and physiotherapy had not helped. No prolonged bed rest or immobilization occurred. Her symptoms persisted throughout pregnancy, after the delivery, and the postpartum period, with worsening intensity.

Six months after delivery, an orthopaedic opinion was requested. Left buttock pain had eased and patient was able to walk without crutches. Physical examination showed a highly localized painful point on the left sacroiliac joint radiating to the back of the left thigh and onto the calf, and inability to fully bear weight on the left leg. Examination of her hips revealed reduced (4/5) left hip abduction and extension muscles length and strength. Straight leg raise and Bragard’s test results were negative. Motor strength, reflexes, and sensation of the lower limbs were intact. On ambulation she showed an antalgic gait pattern with a positive left-sided Trendelenburg sign. Plain X-rays of the lumbar spine and pelvis showed no significant abnormality and there was no evidence of sacroiliac joint disease.

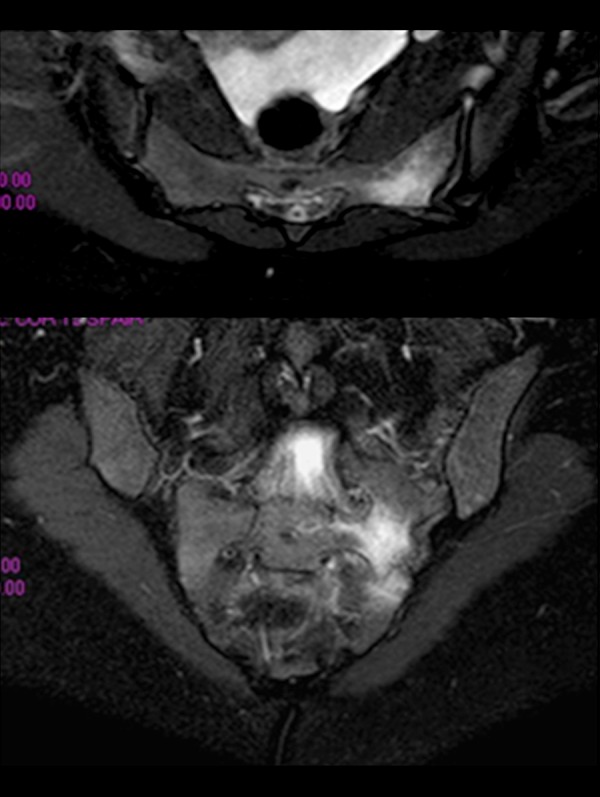

Magnetic resonance imaging (MR) was performed. T2-weighted images and fat-saturated images showed a band of increased signal intensity with marked enhancement in the left sacral ala (Figure 1). A technetium 99m (Tc-99m) bone scan showed increased uptake at the lower end of the left sacroiliac joint and the left sacral ala, reported as compatible with a left-sided sacral stress fracture involving the caudal area of the left sacroiliac joint (Figure 2). Bone densitometry scan revealed normal lumbar spine and left femoral neck bone mineral densities (BMDs). Electromyography (EMG) findings were normal, without radiculopathy, and an extensive workup excluded the occurrence of an underlying metabolic bone disease. The patient was instructed to limit weight-bearing exercise to allow complete fracture healing, and selective infiltration of the sacroiliac joint performed under fluoroscopic guidance instantly resulted in pain reduction.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). T2-weighted images and fat-saturated images showing a band of increased signal intensity with marked enhancement in the left sacral ala.

Figure 2.

Technetium 99m (Tc-99m) bone scan showing increased uptake at the lower end of the left sacroiliac joint and the left sacral ala, compatible with a left-sided sacral stress fracture involving the caudal area of the left sacroiliac joint.

Six months later, the patient reported almost complete resolution of her symptoms. Nevertheless, prolonged sitting, walking long distances, walking in high heels, and running was still causing left buttock discomfort.

Discussion

Atraumatic or stress fracture of the sacrum in pregnancy was first reported by Breuil et al. in 1997 [8]. It presents with low back pain during pregnancy, and continues into the postpartum period. It is an uncommon cause of low back pain, as shown by the few cases reported in the literature; however, the prevalence is probably underestimated because of the lack of specificity of the symptoms [1,2] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of case reports of pregnancy-related sacral stress fractures.

| Author | Year of publi. | When the fracture happened | X-ray showed | MR showed | CT-scan showed | Densitometry | Clinical neurological symptoms | Treatment | Recovery time/aftermath | Other incidents/findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breuil et al. | 1997 | During Pregnancy (7th month) | Fracture of the sacrum (performed after delivery) | Longitudinal insufficiency fracture | – | Lumbar T-score −1.21 | Exquisite painful point on the left sacroiliac articulation | Bed rest | Not stated | 25 OH vitamin D deficiency Increased alkaline phosphatase |

| Thienpont et al. | 1999 | During pregnancy (6th month) | Widened symphysis | Possible sacral stress fracture | Unilateral right sacral ala fracture | – | 4.5 months pain in the lower back and right hip. No neurological symptoms | Absolute rest | 2 months/no recurrence | Trendelenburg’s gait pattern. Restricted and painful hip rotation |

| Schmid et al. | 1999 | During pregnancy (last trimester) | No abnormalities | Excluded acute sacroiliac joint arthirtis | Bilateral sacral ala osteopenia and visible cortical fissure | Lumbar T-score +0.477 | Mennell’s sing + 3 month in pain | Bedrest 2 weeks 200 IU calcitonin 3 weeks |

2 months/4th month MR and CT scan showed resolution and callus formation |

BMI 27 Left Trendelenburg |

| Pishnamaz et al. | 2012 | During Pregnancy (7th month) | – | Non-displaced right sacral ala fracture | – | Normal T-scores | Hospital admission with severe low back pain. 30 weeks in pain + Patrick’s test | Oral analgesics Bed rest Epidural anesthesia |

Completely free from pain at the end of her pregnancy | – |

BMI – Body Mass Index.

Pentecost et al. classified sacral stress fractures into 2 groups [9]: insufficiency fracture and fatigue fractures. Insufficiency fractures occur in weak bone structures under normal mechanical loading. Fatigue fractures occur due to unusual mechanical loading in normal bone structure [10]. Insufficiency fractures have been reported primarily in the geriatric population with osteoporosis or in patients with secondary weakened bone. Sacral fatigue fractures have been reported in a younger population, including female athletes, especially long-distance runners, soldiers, and after lumbosacral arthrodesis [11]. However, both fatigue and insufficiency fractures have been recently reported in pregnant and postpartum patients [5–8,10].

The incidence of pregnancy-related osteoporosis is approximately 0.4/100,000 women [7]. Osteoporosis associated with pregnancy and lactation has rarely been described, and its pathophysiology remains controversial. It has been shown that spine bone mineral density decreases from pre-pregnancy to the immediate postpartum period by a mean of 3.5% in 9 months, increasing afterwards during a follow-up period of 1 to 8 years post-pregnancy, suggesting that pregnancy itself may cause reversible bone loss [11]. During pregnancy, there are additional requirements for calcium, and osteoporosis may occur if there is a failure of the maternal skeletal calcium metabolism [11]. Increasing levels of prolactin and progesterone during pregnancy have been implicated in pregnancy-induced osteoporosis [12]. In addition, transient osteoporosis can occur in association with pregnancy and breast feeding, which can also lead to increased risk of sacral insufficiency fractures [13]. Pregnancy-related osteoporosis is associated with vertebral and femoral neck fractures, most often occurring in the third trimester, and there have been only a few case reports of sacral fractures associated with pregnancy [7,11].

It has been hypothesized that during gestation and breast feeding, women might be prone to sacral fatigue stress fractures. Increased levels of relaxin loosen the pelvic ligaments of the pubic symphysis and the sacroiliac joints, and it is known that pubic instability may cause sacral stress fractures. Other factors such as large gain in weight, hyperlordosis, and sacral anteversion increase mechanical stress on the sacrum [6,13,14].

Sacral stress fractures can be easily missed due to the lack of specificity of the symptoms. The clinical presentation includes groin, buttock, and lumbosacral pain during pregnancy and in the early post-partum period. Radicular symptoms are uncommon but may be present. Symptoms usually increase while sitting, walking, and standing, but decrease while resting. Physical examination usually reveals marked tenderness on palpation over the sacrum, with completely normal neurologic examination [10,11]. However, it has been estimated that there is a 2% incidence of nerve root compromise in patients with osteoporotic fractures of the sacrum. In these fractures, the L5 root can become entrapped between the sacral ala and the transverse process of L5 as the alar fragment moves superiorly and posteriorly [11]. Our patient had radicular symptoms, which may have been secondary to nerve root irritation caused by the right sacral ala fracture.

Diagnosis may be confirmed with the use of diagnostic imaging. Plain radiographs are inadequate in detection of sacral stress fracture [10]. The fracture site may be obscured by over-lying bowel gas, fecal material, vascular calcifications, or by the sacral curvature itself [11]. Shah and Stewart reviewed a series of 27 sacral stress fractures and found 25 cases with normal radiographs [15]. MRI is considered as the criterion standard for diagnosis and is the only method that can be used safely due to radiation exclusion [10]. MRI can show bone marrow edema changes within the sacrum at early stages. In all previously reported cases, the diagnosis was confirmed by MRI and/or CT imaging. A Tc-99m bone scan has excellent sensitivity, but exposure to radiation should be avoided during pregnancy and breastfeeding. If necessary, after delivery, CT can be performed to show fracture healing. Laboratory tests are often non-specific and completely normal laboratory findings are not uncommon. Evaluation of calcium, phosphate, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels should be requested to exclude underlying metabolic bone disease [11]. Bone densitometry scans should be performed to rule-out pregnancy-related osteoporosis. Because of the high radiation load, the investigation should occur only after the pregnancy has ended [7]. Finally, differential diagnosis should exclude other causes of lumbosacral pain, such as lumbosacral spine infections, sacroiliac joint dislocation, pelvic or vertebral compression fractures, and malignancy [2].

In our patient, when the sacral fracture was determined, pregnancy-related osteoporosis was investigated, but the bone densitometry scan measurements showed no evidence of osteoporosis. Our patient had normal vitamin D, calcium, phosphate, and alkaline phosphatase serum levels and no other risk factors for osteoporosis were identified. These findings argued against a classical osteoporosis of pregnancy. The patient’s sacral fracture was considered to be a fatigue stress fracture.

Most patients with pregnancy-related sacral stress fractures respond well to conservative treatment, achieving complete relief from pain. However, adequate analgesic control is particularly challenging during pregnancy because it is complicated by drug interactions with the fetus and the increasing load exerted on the fractured sacrum during pregnancy [7].

Pain control is the first step in treatment of sacral stress fractures. Rest and activity modification are recommended until sufficient pain control is achieved and partial weight-bearing can be tolerated. Early weight-bearing is essential to stimulate osteoblastic activity and to avoid complications [1,10,11]. Paracetamol and ibuprofen are the primary analgesic choices. In cases of severe pain, morphine or epidural anesthesia can be administered under expert control [7]. After delivery, non-invasive biophysical therapy agents, such as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), pulse magnetotherapy (PEMF), capacitively-coupled electrical fields (CCEF), or low-intensity pulsed ultrasound, have been advocated for pain relief and bone healing [1,10].

Recovery time in the literature varies from 4 to 12 weeks, and patients regain ability to perform activities of daily living within an average of 6 weeks [1,7]. Comparing our results with those in other reports, we observed a significant delay in the recovery time. In retrospect, an MRI of the sacrum should have been performed at initial patient consultation, which would have allowed for an early diagnosis, potentially limiting the development of secondary gait and balance problems, particularly in single-leg standing and walking, in an attempt to offload the sacrum. The patient’s primary complaint was of local left-sided sacral tenderness and the provocative effect of weight-bearing.

Our patient had normal plain radiographs. Sacrum MRI demonstrated a vertical fracture in the right sacral ala. A high index of clinical suspicion is important in the initial assessment.

Conclusions

Atraumatic or stress fracture of the sacrum should be included in the differential diagnosis of low back and sacral pain during pregnancy and the post-partum period. A high index of suspicion is necessary to establish an early diagnosis and start appropriate analgesic treatment, rest, and activity modification. In the presence of sacral tenderness aggravated by weight-bearing, an MRI of the sacrum should be performed, and the occurrence of pregnancy-related osteoporosis or a metabolic bone disease should be excluded. Misdiagnosis may lead to prolonged morbidity and the development of secondary gait abnormalities.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors did not receive grants or outside funding in support of their research or preparation of this manuscript. They did not receive payments or other benefits or a commitment or agreement to provide such benefits from a commercial entity. No commercial entity paid or directed, or agreed to pay or direct, any benefits to any research fund, foundation, educational institution, or other charitable or non-profit organization with which the authors are affiliated or associated.

References:

- 1.Sansone V, McCleery J, Longhino V. Post-partum low-back pain of an uncommon origin: A case report. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2013;26:475–77. doi: 10.3233/BMR-130394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narvaez J, Narvaez JA. Post-partal sacral fatigue fracture. Rheumatology. 2003;42:384–85. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rousière M, Kahan A, Job-Deslandre C. Postpartal sacral fracture without osteoporosis. Joint Bone Spine. 2001;68:71–73. doi: 10.1016/s1297-319x(01)00262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Celik EC, Oflouglu D, Arioglu PF. Postpartum bilateral stress fractures of the sacrum. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2013;121(2):178–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmid L, Pfirrmann C, Hess T, Schlumpf U. Bilateral Fracture of the Sacrum Associated with Pregnancy: A Case Report. Osteoporos Int. 1999;10:91–93. doi: 10.1007/s001980050200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thienpont E, Simon JP, Fabry G. Sacral stress fracture during pregnancy – a case report. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999;70(5):525–26. doi: 10.3109/17453679909000996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pishnamaz M, Sellei R, Pfeifer R, et al. Low back pain during pregnancy caused by a sacral stress fracture: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:98. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-6-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breuil V, Brocq O, Euller-Ziegler L, Grimaud A. Insufficiency fracture of the sacrum revealing a pregnancy associated osteoporosis: first case report. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56:278–79. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.4.278b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pentecost RL, Murray RA, Brundley HH. Fatigue, insufficiency and pathologic fractures. JAMA. 1964;187:1001–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.1964.03060260029006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Öztürk G, Külcü DG, Aydoğ E. Intrapartum sacral stress fracture due to pregnancy-related osteoporosis: A case report. Arch Osteoporos. 2013;8:139. doi: 10.1007/s11657-013-0139-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin JT, Lutz GE. Postpartum Sacral Fracture Presenting as Lumbar Radiculopathy: A Case Report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1358–61. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dussa CU, El Daief SG, Sharma SD, Hughes PL. Atraumatic fracture of the sacrum in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;25(7):716–17. doi: 10.1080/01443610500303747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Búrca N. Low back pain post partum. A case report. Manual Therapy. 2012;17:597–600. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coskun E, Oflouglu D, Arioglu P. Postpartum bilateral stress fractures of the sacrum. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2013;121(2):178–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah MK, Stewart GW. Sacral stress fractures: an unusual cause of low back pain in an athlete. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27:E104–8. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200202150-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]