Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the prevalence and CT image characteristics of anterior mediastinal masses in a population-based cohort and their association with the demographics of the participants.

Materials and methods

Chest CT scans of 2571 Framingham Heart Study participants (mean age 58.9 years, 51% female) were evaluated by two board-certified radiologists with expertise in thoracic imaging for the presence of anterior mediastinal masses, their shape, contour, location, invasion of adjacent structures, fat content, and calcification. For participants with anterior mediastinal masses, a previous cardiac CT scan was reviewed for interval size change of the masses, when available. The demographics of the participants were studied for any association with the presence of anterior mediastinal masses.

Results

Of 2571, 23 participants (0.9%, 95% CI: 0.6–1.3) had anterior mediastinal masses on CT. The most common CT characteristics were oval shape, lobular contour, and midline location, showing soft tissue density (median 32.1 HU). Fat content was detected in a few cases (9%, 2/23). Six out of eight masses with available prior cardiac CT scans demonstrated an interval growth over a median period of 6.5 years. No risk factors for anterior mediastinal masses were detected among participants’ demographics, including age, sex, BMI, and cigarette smoking.

Conclusions

The prevalence of anterior mediastinal masses is 0.9% in the Framingham Heart Study. Those masses may increase in size when observed over 5–7 years. Investigation of clinical significance in incidentally found anterior mediastinal masses with a longer period of follow-up would be necessary.

Keywords: Anterior mediastinal masses, CT, Prevalence, The Framingham Heart Study

1. Introduction

Incidental encounters with mediastinal masses have become more common with the growing use of computed tomography (CT) in clinical practice as well as in screening of lung cancer. Anterior mediastinal masses account for 50% of all mediastinal masses [1], [2]. Anterior mediastinal masses can represent a wide spectrum of diseases, including thymoma, thymic carcinoma, thymic cyst, thymic hyperplasia, mature teratoma, malignant germ cell tumor, and malignant lymphoma [1], [3]. CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the noninvasive study of choice for the diagnosis of mediastinal masses [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. To date, the report by Henschke et al. is the only study describing a prevalence of anterior mediastinal masses of 0.4% (41/9263) in the Early Lung Cancer Action Project (ELCAP) with CT scans of 9263 smokers over the age of 40 at high risk for lung cancer [2]. They also reported that the mediastinal masses, if less than 3 cm in diameter, remained unchanged or even decreased in size at a short follow-up CT scan 1 year later [2].

Despite these findings, little is known about the prevalence and natural course of anterior mediastinal masses in the general population. There are no prior studies of anterior mediastinal masses with a long follow-up and their risk factors have not been investigated. To investigate the prevalence and natural course of anterior mediastinal masses we assessed 2571 chest CT scans from the Framingham Heart Study and retrospectively assessed prior cardiac CT scans from those identified to have an anterior mediastinal mass. The demographics of the participants were also investigated for any associations with anterior mediastinal masses.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study population

The Framingham Heart Study was launched in 1948 to investigate epidemiologic risk factors of cardiovascular disease [9]. Subsequent to the recruitment of the original cohort in 1948, the offspring cohort, formed by children of the original cohort members and their spouses, was recruited in 1971, followed in 2002 by the third generation cohort, consisting of grandchildren from the original cohort members. From 2008 to 2011, 2764 participants of the Framingham Heart Study from the offspring and the third generation cohorts underwent non-contrast chest CT scans (FHS-MDCT2) without any clinical intentions. Participants underwent CT scans in the supine position at full inspiration using a 64-detector-row CT scanner (Discovery, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) with 120 kV and 300–350 mA (optimized with body weight) with a gantry rotation time of 0.35 s. The section thickness of images was 0.63 mm. Of the 2633 participants with CT scans available for review, 62 participants with prior sternotomy were excluded from the study (Fig. 1) because it could have purported thymectomy and hamper evaluations of the anterior mediastinum with significant artifact. Therefore, the study population included 2571 participants (mean age 58.9 years, range 34–92 years, 51% female). From 2002 to 2005, cardiac CT scans (FHS-MDCT1) were also provided. Participants underwent ECG-gated non-contrast cardiac scans in the supine position at full inspiration using an 8-detector-row CT scanner (Lightspeed, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) with 120 kV, 320–400 mA (optimized with body weight), and a gantry rotation time of 0.5 s. The section thickness of cardiac CT images was 2.5 mm. Cardiac CT scans cover from 2 cm below the carina to the apex of the heart and we utilized the scans only for comparison if the mass lesion was within the covered area. The institutional review boards at Brigham and Women's Hospital and Boston University approved the present study and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study is compliant with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Fig. 1.

Workflow of the study.

2.2. Evaluation of chest CT images

An anterior mediastinal mass was defined as any mass lesion no less than 5 mm in the short axis diameter located in the anterior mediastinum, the compartment between the back of the sternum and the anterior aspect of the great vessels and pericardium [8], [10], [11], [12]. Cases with multiple masses were not included in the analysis as these were most consistent with lymphadenopathy and the present study focused on solitary anterior mediastinal masses. All CT scans were uploaded to a Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) workstation (Virtual Place Raijin, AZE Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and screened for anterior mediastinal masses by a board-certified radiologist (T.A.). Bidimensional diameters of the longest and perpendicular longest diameters (mm), and CT attenuations (HU, Hounsfield unit) were also measured by the radiologist using a caliper-type measurement tool as described previously [13]. Cases with an anterior mediastinal mass as a result of the first review were further evaluated by two board-certified radiologists with expertise in thoracic imaging (M.N. and H.H.) for the following qualitative findings: (1) shape (round, oval, triangular, irregular), (2) contour (smooth, lobular, irregular), (3) location (midline, right-sided, left-sided), (4) invasion or mass effect on adjacent structures, and (5) other findings (fat content, necrosis, calcification) [14]. The readers were blinded to any participants’ information, including age and sex. After the evaluation of these features, radiologic diagnoses (up to three differential diagnoses with rank) were also provided by consensus. In participants with anterior mediastinal masses, we retrospectively assessed their previous cardiac CT scans (FHS-MDCT1, median 6.5 years prior to the FHS-MDCT2), when available, for interval change (no change, increase, or decrease in size). We defined growth in the mass as a more than 20% increase in the longest diameter. For the evaluation and measurements of the masses, window level and width were fixed at 50 HU and 350 HU, respectively.

2.3. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses used mixed effect models for continuous traits and generalized estimating equations for binary traits to account for familial correlations [15]. The demographics of the participants were studied for associations with the presence of anterior mediastinal masses using R (version 3.1.1, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). P values were two-sided and regarded as statistically significant at the level of 0.05.

3. Results

Of 2571 participants, 23 participants (0.9%, 95% confidence interval 0.6–1.3) had a solitary anterior mediastinal mass based on the radiologic review of CT scans. The summary of the quantitative measurements for the 23 participants is presented in Table 1 and the distribution of the longest diameter of the masses is shown in Table 2. The medians of the longest and the perpendicular longest diameters and CT attenuation were 17.9 mm (range 9.3–38.2), 10.5 mm (5.1–23.0), and 32.1 HU (−10.7 to 392.4), respectively. The results of the qualitative CT findings are shown in Table 3. The most common CT characteristics of the anterior mediastinal masses were oval shape (14/23, 62%), lobular contour (11/23, 47%), and midline location (9/23, 39%). Calcifications and fat contents were present in 2 out of 23 cases (9%), respectively. Invasion and mass effect to the adjacent structures, or necrosis in the mass, were not observed in any case. The leading radiologic diagnosis was thymoma in 11 (48%), thymic cyst in 3 (13%), thymic hyperplasia in 2 (9%), pericardial cyst in 2 (9%), and solitary lymph node in 5 (22%).

Table 1.

Size and CT attenuation of anterior mediastinal masses in 23 participants.

| Measurements | Mean ± SD [range] | Median [Q1, Q3] |

|---|---|---|

| Longest diameter (mm) | 19.9 ± 9.2 [9.3 to 38.2] | 17.9 [11.0, 30.0] |

| Longest perpendicular diameter (mm) | 11.3 ± 4.4 [5.1 to 23.0] | 10.5 [7.4, 13.8] |

| CT attenuation (HU) | 46.3 ± 78.6 [−10.7 to 392.4] | 32.1 [10.2, 56.2] |

SD: standard deviation; Q1, Q3: first and third quartiles.

Table 2.

Longest diameter of anterior mediastinal masses.

| Longest diameter (mm) |

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5–10 | 10–20 | 20–30 | ≥30 | ||

| Count No. (%) | 4 (17%) | 9 (39%) | 5 (22%) | 5 (22%) | 23 |

Table 3.

Qualitative features of anterior mediastinal masses on CT images.

| Shape | |

| Oval | 14 (62%) |

| Irregular | 7 (30%) |

| Round | 1 (4%) |

| Triangular | 1 (4%) |

| Contour | |

| Lobular | 11 (47%) |

| Smooth | 10 (44%) |

| Irregular | 2 (9%) |

| Location | |

| Midline | 9 (39%) |

| Left-sided | 8 (35%) |

| Right-sided | 6 (26%) |

| Calcification | |

| Absent | 21 (91%) |

| Present | 2 (9%) |

| Fat content | |

| Absent | 21 (91%) |

| Present | 2 (9%) |

The summary of the participants’ demographics is shown in Table 4. Participants with anterior mediastinal masses had a mean age of 62.1 years (median 60.9 years, range 39.0–83.8 years) and 12 were female (52%). Statistically significant differences were not detected in age, sex, BMI, smoking status, or pack-years between participants with and without anterior mediastinal masses (P ≥ 0.2).

Table 4.

Characteristics of participants with and without anterior mediastinal masses.

| Characteristic | Without anterior mediastinal mass (N = 2548) | With anterior mediastinal mass (N = 23) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age – years | 58.9 ± 11.9 | 62.1 ± 13.2 | 0.2 |

| Female – no. (%) | 1299 (51) | 12 (52) | 0.9 |

| Body mass indexb | 28.5 ± 5.4 | 27.5 ± 4.6 | 0.3 |

| (N = 2534) | |||

| Smoking status – no. (%) | |||

| Never | 1234 (49) | 11 (48) | 0.9 |

| Former | 1134 (45) | 12 (52) | 0.5 |

| Current | 159 (6) | 0 (0) | – |

| (N = 2527) | |||

| Pack-years | 18.6 ± 18.0 | 19.9 ± 16.2 | 0.2 |

| (N = 1211) | (N = 11) |

P values for the comparison between participants with and without anterior mediastinal masses were calculated with the use of linear mixed effect models to account for familial relationships in the Framingham Heart Study, as described previously [15].

The body mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

Of 23 participants with anterior mediastinal masses, we were able to retrospectively assess prior cardiac CT scans in 8 participants (median interval of 6.5 years, ranging 5.9–7.8 years). In all 8 cardiac CT scans, we could identify an anterior mediastinal lesion. With a follow-up period of more than 5 years, six masses out of eight increased in size (Table 5). Median diameter in the six cases at the initial CT scans is 14.6 mm (range 6.8–25 mm). Representative images with enlarged thymic masses (Cases #1 and #2 in Table 5) are shown in Fig. 2, Fig. 3.

Table 5.

Interval changes in eight cases with comparison of CT scans.

| Case # | The longest diameter (mm) at the initial CT (FHS-MDCT1) | The longest diameter (mm) at the consequent CT (FHS-MDCT2) | Percent increase in the diameter (%) | Interval duration between the CT scans (year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12.3 | 38.2 | 211 | 5.9 |

| 2 | 8.1 | 17.9 | 121 | 7.2 |

| 3 | 6.8 | 9.7 | 43 | 5.9 |

| 4 | 25.0 | 34.3 | 37 | 7.8 |

| 5 | 24.9 | 33.2 | 33 | 6.4 |

| 6 | 16.9 | 20.9 | 24 | 7 |

| 7 | 22.9 | 24.3 | 6 | 6.2 |

| 8 | 33.0 | 30.4 | −8 | 6.6 |

Cases #1–6 showed an increase of the masses more than 20% in diameter.

Median diameter in the six cases at the initial CT scans is 14.6 mm, ranging 6.8–25 mm.

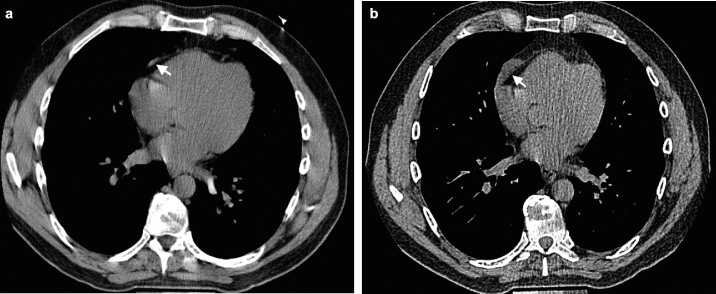

Fig. 2.

An anterior mediastinal lesion in a 46-year-old male participant. A CT image at initial study (a) shows a small streak of soft tissue (arrow) adjacent to the right anterior part of the pericardium. A follow-up CT image 5.9 years later (b) reveals that the lesion increased in diameter by 211% (from 12.3 to 38.2 mm) during that period. (Supplementary DICOM images are available.)

Fig. 3.

An anterior mediastinal lesion in a 73-year-old female participant. A CT image at initial study (a) shows a small nodule, somewhat triangular and deviated slightly to the left (arrow), in the anterior mediastinum. A follow-up CT image 7.2 years later (b) shows that the lesion (arrow) increased in diameter by 121% (from 8.1 to 17.9 mm) over that period. Thymoma was suspected radiologically. (Supplementary DICOM images are available.)

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrated a 0.9% prevalence of anterior mediastinal masses in the population-based Framingham Heart Study cohorts, which included both smoker and non-smoker adults with a wide range of ages (34–92 years). Oval shape, lobular contour, and midline location are the most frequent image findings for the anterior mediastinal masses. None of the masses showed invasion of adjacent structures or apparent metastasis to the lungs. Six out of the eight masses with previous CT scans demonstrated an increase in size by more than 20% over a period of 5–7 years. The participant characteristics, including age, sex, BMI, and cigarette smoking are not associated with the presence of anterior mediastinal masses.

In the previous study of smokers at increased risk of lung cancer, the prevalence of anterior mediastinal masses was 0.4% in smokers at high risk for lung cancer [2]. The prevalence of anterior mediastinal masses in the Framingham Heart Study was approximately twice as high as the previous report [2]. Potential causes of this difference may include age, smoking status, and size criteria of the masses. Although the prior study noted no interval change in the mediastinal masses less than 3 cm at a 1-year follow-up, we note that six out of eight of the anterior mediastinal masses less than 3 cm in initial diameter (median longest diameter 14.6 mm, range 6.8–25 mm) increased in size over a median follow-up period of 6.5 years. This observation calls into question how to manage a small incidental anterior mediastinal lesion within a short time period.

In the present study, only two cases, which were radiologically suspected to be either thymomas or thymic cysts, had calcifications. Fat contents, which lead to the radiologic diagnosis of thymic hyperplasia, were noted in only two cases. Fat infiltration has been reported as a useful finding to differentiate anterior mediastinal masses, suggesting thymic hyperplasia or normal thymus [3]. Germ cell tumors or thymolipoma reportedly may contain fat tissue, but usually occur at a relatively young age [16], [17].

CT attenuation is a reliable measurement of thymic lesions [3], [14]. In the present study, most of the masses showed soft tissue density (median 32.1 HU) and were suspected thymomas. However, distinguishing thymic cysts from thymomas on CT images is still challenging because thymic cysts may appear with higher CT attenuation than serous fluid due to protein-rich content or hemorrhage [1], [13], [16]. It may be true that low CT attenuation is helpful to diagnose cystic lesions and that anterior mediastinal masses with low attenuation of simple fluid can be consistent with thymic cysts or pericardial cysts; however, cystic lesions cannot be excluded even in a mass with higher attenuation [1], [13].

Our study has several limitations. First, the number of previous CT scans we assessed retrospectively in those identified to have an anterior mediastinal mass was limited. We designed the study this way because initial CT scans had limitations in coverage of the mediastinum due to the cardiac protocol of the scans. Second, our study does not include pathological diagnoses due to the uniqueness of the population-based study design. However, discussing anterior mediastinal masses in general rather than specific diagnosis of the mass would be still worthy and applicable in our daily clinical practice. Third, the participants’ clinical information is limited in terms of medical conditions associated with thymic lesions, such as autoimmune diseases, especially myasthenia gravis [18], [19], [20], thyroid diseases, malignancies, and systemic treatment with steroid or antineoplastic drugs [16], [17]. Because the Framingham Heart Study originally focused on cardiovascular diseases, information associated to thymic lesions has not been thoroughly obtained. Fourth, participants of the Framingham Heart Study were recruited in a relatively limited geographical area and most are of European descent. Some critics state that the Framingham Heart Study participants are healthier than the general population due to high health consciousness and careful follow-up with substantial medical support. However, the Framingham Heart Study is still one of the largest study cohorts recruited regardless of participants’ disease status, providing important data in epidemiology [21].

In conclusion, the prevalence of anterior mediastinal masses is 0.9% in the Framingham Heart Study. They most often appear as an oval mass with a lobular contour at the midline location. Those masses may grow in size even though the baseline size is as small as 6–8 mm when observed for 5–7 years, suggesting potential growth of the masses over a long period of time. There are no statistically significant risk factors detected, including age, sex, BMI, or smoking status, in association with the presence of anterior mediastinal masses. Further investigation with a long period of follow-up is necessary to reveal the clinical significance of incidentally found anterior mediastinal masses.

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare no conflicts of interest on the present study.

Funding

Dr. Nishino is supported by NCI Grant: 1K23CA157631. Dr. Washko is supported by NIH Grants: R01 HL116473, R01 HL107246, and P01 HL114501. Dr. Hunninghake is supported by NIH Grants: K08 HL092222, U01 HL105371, P01 HL114501, and R01 HL111024. Dr. Hatabu is supported by NIH Grants: K25 HL104085 and R01 HL116473. This work was partially supported by the NHLBI's Framingham Heart Study contracts: N01-HC-25195 and R01 HL111024.

Acknowledgement

Authors acknowledge Alba Cid M.S. for editorial work on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ejro.2014.12.003.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Tomiyama N., Honda O., Tsubamoto M., Inoue A., Sumikawa H., Kuriyama K. Anterior mediastinal tumors: diagnostic accuracy of CT and MRI. Eur J Radiol. 2009;69(2):280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henschke C.I., Lee I.J., Wu N., Farooqi A., Khan A., Yankelevitz D. CT screening for lung cancer: prevalence and incidence of mediastinal masses. Radiology. 2006;239(2):586–590. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2392050261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araki T., Sholl L.M., Gerbaudo V.H., Hatabu H., Nishino M. Imaging characteristics of pathologically proven thymic hyperplasia: identifying features that can differentiate true from lymphoid hyperplasia. Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202(3):471–478. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baron R., Lee J., Sagel S., Levitt R. Computed tomography of the abnormal thymus. Radiology. 1982;142(1):127–134. doi: 10.1148/radiology.142.1.7053522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inaoka T., Takahashi K., Mineta M., Yamada T., Shuke N., Okizaki A. Thymic hyperplasia and thymus gland tumors: differentiation with chemical shift MR imaging. Radiology. 2007;243(3):869–876. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2433060797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Juanpere S., Canete N., Ortuno P., Martinez S., Sanchez G., Bernado L. A diagnostic approach to the mediastinal masses. Insights Imaging. 2013;4(1):29–52. doi: 10.1007/s13244-012-0201-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi K., Al-Janabi N.J. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of mediastinal tumors. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;32(6):1325–1339. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown L.R., Aughenbaugh G.L. Masses of the anterior mediastinum: CT and MR imaging. Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157(6):1171–1180. doi: 10.2214/ajr.157.6.1950860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendis S. The contribution of the Framingham Heart Study to the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a global perspective. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;53(1):10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitten C.R., Khan S., Munneke G.J., Grubnic S. A diagnostic approach to mediastinal abnormalities. Radiographics. 2007;27(3):657–671. doi: 10.1148/rg.273065136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carter B.W., Tomiyama N., Bhora F.Y., Rosado de Christenson M.L., Nakajima J., Boiselle P.M. A modern definition of mediastinal compartments. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9(9 Suppl. 2):S97–S101. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujimoto K., Hara M., Tomiyama N., Kusumoto M., Sakai F., Fujii Y. Proposal for a new mediastinal compartment classification of transverse plane images according to the Japanese Association for Research on the Thymus (JART) General Rules for the Study of Mediastinal Tumors. Oncol Rep. 2014;31(2):565–572. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Araki T., Sholl L.M., Gerbaudo V.H., Hatabu H., Nishino M. Intrathymic cyst: clinical and radiological features in surgically resected cases. Clin Radiol. 2014;69(7):732–738. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Araki T., Sholl L.M., Gerbaudo V.H., Hatabu H., Nishino M. Thymic measurements in pathologically proven normal thymus and thymic hyperplasia: intraobserver and interobserver variabilities. Acad Radiol. 2014;21(6):733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uh H.W., Wijk H.J., Houwing-Duistermaat J.J. Testing for genetic association taking into account phenotypic information of relatives. BMC Proc. 2009;7(Suppl. 3):S123. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-3-s7-s123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishino M., Ashiku S.K., Kocher O.N., Thurer R.L., Boiselle P.M., Hatabu H. The thymus: a comprehensive review. Radiographics. 2006;26(2):335–348. doi: 10.1148/rg.262045213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimosato Y., Mukai K., Matsuno Y. ARP Press; Silver Spring, MD: 2010. Tumors of the mediastinum; AFIP atlas of tumor pathology 4th series fascicle 11. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Priola A.M., Priola S.M. Imaging of thymus in myasthenia gravis: from thymic hyperplasia to thymic tumor. Clin Radiol. 2014;69(5):e230–e245. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicolaou S., Muller N.L., Li D.K., Oger J.J. Thymus in myasthenia gravis: comparison of CT and pathologic findings and clinical outcome after thymectomy. Radiology. 1996;201(2):471–474. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.2.8888243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pirronti T., Rinaldi P., Batocchi A., Evoli A., Di Schino C., Marano P. Thymic lesions and myasthenia gravis. Acta Radiol. 2002;43(4):380–384. doi: 10.1080/j.1600-0455.2002.430407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunninghake G.M., Hatabu H., Okajima Y., Gao W., Dupuis J., Latourelle J.C. MUC5B promoter polymorphism and interstitial lung abnormalities. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(23):2192–2200. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1216076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.