Abstract

Transcriptional regulation of thousands of genes instructs complex morphogenetic and molecular events for heart development. Cardiac transcription factors (TFs) choreograph gene expression at each stage of differentiation by interacting with co-factors, including chromatin-modifying enzymes, and by binding to a constellation of regulatory DNA elements. Here, we present salient examples relevant to cardiovascular development and heart disease and review techniques that can sharpen our understanding of cardiovascular biology. We discuss the interplay between cardiac TFs, cis-regulatory elements and chromatin as dynamic regulatory networks, to orchestrate sequential deployment of the cardiac gene expression program.

Keywords: cardiovascular development, gene regulation, heart disease

Introduction

As one of the first organs to develop, the heart pumps nutrients, including oxygen, to the growing embryo. From embryonic stem cells, mesoderm, cardiac precursors to cardiomyocytes, these differentiating cells undergo movement, proliferation, and death. The mammalian heart undergoes intricate morphogenesis. At least two fields of cardiac progenitors migrate midline to form a linear heart tube, which subsequently loops rightward. Neural crest cells contribute to extensive remodeling to form the mature four-chambered heart. Aberrations in cardiac development lead to congenital heart diseases (CHDs), a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in childhood.

Studying gene regulation of the developing cardiovascular system presents unique challenges, compared to other organ systems. As an essential organ system, environmental or genetic etiologies can cause abnormal cardiac morphogenesis and lead to embryonic demise, which can be difficult to prenatally diagnose and to study. Human heart tissue is not readily accessible and usually limited to pathologic specimens. In mouse, the embryonic heart is relatively small, so only a small amount of in vivo cardiac tissue can be recovered. Despite these hurdles, tremendous progress has been made over the last 25 years to identify the genetic building blocks for cardiac development and the genetic culprits for CHDs, including transcription factors (TFs), their co-factors and regulatory regions that precisely regulate cardiac gene expression 1,2,3. Insights from cardiac development in vivo have been instructive for establishing methods for directed cardiac differentiation in vitro from pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) 4,5, for transdifferentiation of mesoderm to the cardiac lineage 6 and for cardiac reprogramming from fibroblasts 7–11.

A TF is a protein with sequence-dependent affinity for DNA that modulates transcriptional activity of target genes (Figure 1A). Co-factors, which interact with TFs but do not bind DNA directly, also regulate gene expression and participate in transcriptional networks. For this review, a “cardiac” TF is expressed in the progeny or descendants of the heart fields during development, although its expression may not be exclusive to or enriched in the heart. TF functions are targeted to specific sites of the genome called cis-regulatory elements via recognition of specific DNA motifs. Their affinity for a given DNA motif can be modulated by protein or RNA co-factors and by local physical properties of the DNA fiber and surrounding chromatin.

Figure 1. Molecular players for transcriptional regulation.

(A) Cis-regulatory elements containing DNA binding sites are bound by transcription factors and (B) modulate the assembly of the Pre-Initiation Complex at promoters through (C) physical contacts driven by a three-dimensional arrangement of chromatin, thereby acting as (D) a molecular platform between cellular signaling and gene activity.

TFs act as a mechanistic link to the transcription apparatus for gene activation (Figure 1B). Their action culminates in recruitment of transcriptional machinery, including RNA polymerase II (Pol II), to promoters and initiation of RNA synthesis 12. Many types of RNA species have an integral function in control of transcriptional activity, through processes that often involve interaction with TFs or chromatin-modifying proteins, as reviewed in depth elsewhere 13. Many co- and post-transcriptional steps are also important in controlling gene expression, such as polymerase initiation, pausing and elongation 14. We will focus on the mechanisms directly upstream of the assembly of the Pre-Initiation Complex that function during cardiac differentiation and development.

We hope to shed light on principles that govern cellular transitions relevant to cardiovascular biology and human disease. Therefore, we first describe how cardiac TFs were identified and what is known about their binding properties. We then discuss how their partnership with DNA, chromatin and other TFs edifies regulatory elements that control transcription in cis. Finally, we explain how these mechanisms integrate to form regulatory networks, allowing dynamic patterning of gene expression in cardiac development.

I. Cardiac transcription factors and co-factors

In this section, we discuss how TFs and co-factors for cardiac development have been identified, based on evolutionary conservation, expression pattern or function, and then discuss approaches to study their cardiac function.

Identifying transcription factors by evolutionary conservation

Evolutionary conservation can be leveraged to identify orthologous cardiac TF genes in invertebrates and mammalian species. Drosophila melanogaster has a circulatory system composed of a rudimentary tube, the dorsal vessel, whose ontogeny is somewhat comparable to the mammalian embryonic linear heart tube. Many genes involved in specification and differentiation of the cardiac mesoderm in Drosophila play a role in mammalian cardiac development. Tinman (initially named msh-2/NK4) was first identified 15 and shown to be required for specification of heart and visceral muscles in Drosophila 16,17. Soon thereafter, Nkx2-5/Csx was cloned using part of the Drosophila msh2 sequence as a probe for low stringency hybridization with embryonic mouse heart cDNA 18. As more mammalian TFs were identified, similar strategies based on homology were employed to identify paralogous TF family members that share related structural domains. For example, Hand2 was cloned by phagemid library screening of mouse genomic DNA with a mouse Hand1 cDNA hybridization probe 19.

Sequence conservation might tempt us to think that the functions of those TFs in cardiac development are functionally conserved. As one telling example, mouse Nkx2-5 compensates for loss of tinman in Drosophila, for visceral mesoderm specification and even cardiogenesis, though only when appended to the Drosophila-specific tinman N-terminal domain 20. These results illustrate that some degree of functional conservation may exist between orthologous cardiac TFs in mammals and flies. However, loss-of-function of tinman or Nkx2-5 causes different phenotypes, demonstrating divergent functions of a cardiac transcription factor in distinct organisms despite an apparent conservation of its biochemical functions. This may be due to differences in mesoderm development between flies and mammals, or perhaps by targeting different regulatory elements containing similar DNA-binding motifs in a distinct genomic context.

Identifying transcription factors by expression patterns

Complementary methods to identify cardiac factors were based on screening for heart-specific expression. Myocardin was identified by searching publicly available databases of expressed sequence tags (ESTs) for novel sequences present only in cardiac cDNA 21. Using a PCR-based modification of subtractive hybridization to enrich for embryonic chicken cDNAs common to the early heart field and linear heart tube but not the posterior non-cardiogenic region, Bop/Smyd1 was isolated 22. In comparison, although Baf60c was discovered in a screen as a target of Wnt signaling, in situ hybridization demonstrated cardiac-restricted expression during development 23.

Important cardiac TFs were discovered by techniques based on expression in the heart. However, expression-based approaches are limited: they might miss widely expressed TFs and chromatin-modifying enzymes in cardiac development. Ubiquitous factors may function differently in various tissues, and a “heart” role may be important for a “ubiquitous” chromatin-modifying enzyme. For example, Brg1 modulates myosin heavy chain switching during heart development and cardiac hypertrophy 24. Conversely, an expression-based approach may miss TFs that are not expressed in the heart, but their function and expression in other tissues are important for cardiac development.

Identifying transcription factors by function in cardiovascular development

Methods to identify TFs implicated during heart development without a priori knowledge about expression pattern can be deployed, potentially revealing factors required transiently or non-autonomously to the cardiac lineage. In particular, forward genetic screens, based on circulatory system phenotypes in animal models, identified several factors necessary for cardiovascular development. For example, N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)–induced mutations in zebrafish identified Gridlock/Hey2/Hrt2 25, which was also cloned using homology screening to the basic helix-loop-helix domain 26. Such loss-of-function screens are especially challenging in mice because heart dysfunction can cause early embryonic lethality. To overcome these hurdles, several groups used in utero ultrasound-based phenotyping to uncover mutations with early cardiovascular developmental defects in mice 27. Yet, phenotype-based screens may not uncover factors that are also essential before heart formation. Many important heart TFs function in other tissues, complicating forward genetic approaches based on constitutive gene deletions. For example, a role for Eomes in the specification of cardiac mesoderm is not evident unless its early requirement for extra-embryonic tissue growth and the epithelial-to-mesenchyme transition during gastrulation is bypassed 28.

By identifying the genetic basis of human cardiomyopathies, we might better understand human diseases. For example, linkage analysis revealed that heterozygous TBX5 mutations cause Holt-Oram syndrome (HOS), which includes CHDs and upper limb abnormalities, in humans 29,30. Tbx5 is necessary in mice 31 and expressed in the heart 32. However, human linkage analysis of monogenic cardiac diseases, many of them autosomal dominant disorders, implicated only a few factors 1,2. Exome sequencing is a powerful alternative method to survey the integrity of TF-coding genes in patients with cardiovascular defects. Using exome sequencing of parent-offspring trios, de novo mutations of the ubiquitous TF SMAD2 and several chromatin-modifying enzymes were associated with non-syndromic CHDs 33. These included the broadly expressed Trithorax-group histone methyltransferase MLL2, which was also identified in an exome study of unrelated probands with Kabuki syndrome, which includes CHDs and non-cardiac anomalies 34. As congenital heart defects can be isolated or associated with syndromes, this may be explained by the observation that part of the molecular toolbox underlying cardiac development is also deployed in other developmental pathways. Consequently, there may be only a few, truly cardiac-specific factors.

Investigating the roles of transcription factors in cardiac biology

To explore cardiac TFs in heart biology, investigators have typically studied developmental abnormalities from the loss of function of TFs. Yet, a TF can have multiple roles in controlling cardiac function, typically by acting at different developmental times or by distinct functions in different cell types of the heart. Since these functions are not readily revealed by analyzing constitutive deletions, exploring these roles often requires refined genetic analysis in animal models. For example, Tbx5 is expressed in the left ventricle, atria, and conduction system in the developing heart. Tbx5-null mice die by embryonic day (E10.5) with defects in cardiac looping and hypoplasia of the left ventricle 31. Ventricle-restricted homozygous deletion of Tbx5 results in a single, mispatterned ventricle and embryonic lethality by E11.5 35. Deletion of Tbx5 by Mef2CAHF-Cre, which overlaps Tbx5 in the interventricular septum, maintained a morphologic and molecular distinction between left and right ventricles, but lacked an interventricular septum, consistent with a requirement of Tbx5 for ventricular septal formation 35. Endocardium-specific deletion of Tbx5 did not cause embryonic lethality, but caused 100% penetrance of atrial septal defects (ASDs) 36. Thus, TFs necessary for initial specification and expansion of the cardiac lineage, such as Tbx5, can also function later for heart morphogenesis.

Tissue-specific deletions of broadly expressed factors have revealed insights during heart development. Cardiac-specific deletion of Ezh2 37,38 showed that Ezh2 and the Polycomb repressive complex-2 (PRC2) complex are necessary for cardiac morphogenesis and homeostasis. Despite broad expression and function, Ezh2 has a very specific role in cardiac precursors to repress a transiently expressed cardiac TF, Six1 38. This highlights a specific cardiac role for a broadly important chromatin regulator.

Transcription factor-transcription factor protein interactions

A challenge is to understand how disruption of a TF can alter expression of hundreds or thousands of genes. How this works is unclear, but hints can be obtained from how TFs modulate transcription. TFs function within protein complexes, which include other TFs and chromatin-modifying enzymes. A candidate approach revealed several TF-TF interactions between Gata4 and Tbx5 39 or Tbx5 and Nkx2-5 31. Unbiased approaches, such as expression cloning in mammalian or yeast two-hybrid systems, uncovered interactions between Tbx5 and Nkx2-5 40 and Gata and Fog factors 41. These interactions may be crucial in heart development. For example, a single amino acid change in a mutant Gata4 allele disrupts an interaction with the co-factor Fog2 and leads to abnormal heart development 42.

Mass spectrometry can elucidate global protein interaction networks 43 and identify post-translational modifications that modulate TF functions, such as the methylation of Gata4 44. With stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC), the entire cellular proteome can be evaluated, including global post-translational modifications 45 or for nuclear protein components from cardiomyocytes in Xenopus 46. These proteomic approaches provide entry points to identify other important factors in cardiac biology. However, not all TF-TF interactions are functionally relevant at all target genes. Insights into partner functionality came from characterizing how TFs contact the regulatory regions of their target genes.

Transcription factor-DNA binding elements

Sequence-specificity is conferred by properties of the DNA binding domain of TFs. Additional factors participate in modulating TF affinity for a DNA motif, including protein or RNA co-factors, physical properties of DNA (e.g., bending), post-translational modifications of the TF, and local chromatin structure. A TF typically contacts many DNA elements that can be distinct in motif composition, even in the same cell type. The general motif composition of these elements is similar within a TF family (e.g., T-box vs. Homeobox), with variations among TF family members.

A common approach to assess TF affinity is to perform in vitro binding assays and electromobility shift assays (EMSA). Candidate sequences can be obtained using variations of a known motif of a TF from the same family. This approach identified a sequence that recruited Tbx5 in vitro, based on similarity to a Brachyury-specific motif 31,40. In a less biased way, a PCR-based selective enrichment by affinity method was used to identify a similar binding motif for Tbx5 47. Complementary in vitro methods, such as mechanically induced trapping of molecular interactions (MITOMI), can determine quantitative TF binding information 48.

Actual binding in vivo can be assessed by chromatin immunoprecipitation with sequencing (ChIP-seq) and bioinformatics analysis for enriched motifs. This allows ab initio discovery of preferential binding motifs. Differences in cognate motifs for the same TF may be observed in different cell types, because a regulatory co-factor is expressed differentially, such as Fog1 for the hematopoietic TF Gata1 49. Methods to precisely identify TF footprints, such as ChIP-exo 50, may greatly enhance our understanding of TF binding specificity.

Strikingly, TFs bind a small fraction of DNA elements that harbor their consensus binding site. The identity of bound sites can be different between cell types. Thus, features other than nucleotide sequences are major determinants of TF binding to their DNA elements. Chromatin structure and nucleosome positioning are major determinants of TF binding. Nucleosomes can mask the binding site of a given TF. Reciprocally, a TF can interfere with nucleosome sliding once bound to DNA, altering nucleosome positioning and affecting binding of another TF at the same site 51.

Another surprise from compiling ChIP-seq datasets is that distinct TFs often bind similar regions in a given cell type. Some cluster in stretches that span thousands of bases 52,53. In ChIP analysis of cardiac TFs in HL-1 cells 54,55, a mouse cardiomyocyte line, and adult mouse hearts 56, combinatorial binding of several TFs occurs at hundreds of regions across the genome, and binding of multiple TFs marks cardiac enhancer regions. Importantly, this suggests regulatory activity on transcription emerges from combinatorial binding and action of multiple TFs on the same genomic region. Although the underlying mechanism is still unclear, this may imply that different TFs may interact with each other once bound to the same DNA region, provided that arrangement of their binding sites favors such interactions. For example, two regulatory regions with the same motif composition but in a different organization (orientation, position or distance) may have different regulatory outputs. Such a principle, referred to as motif grammar, enables cooperativity between clustered homo- or heterotypic TF binding events 57. High-throughput binding assays, such as high-throughput systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (HT-SELEX) 58 or high-throughput sequencing-fluorescent ligand interaction profiling (HiTS-FLIP) 59, allow progress toward a deeper understanding of how nucleotide context of a TF binding site influences affinity of that TF for its cognate site. With information from massively parallel reporter assays in vivo 60, it is feasible to gain insight into how structural variation quantitatively affects the regulatory function of TF binding sites. This will be invaluable for understanding how genetic alterations of regulatory sequences disrupt cardiac gene expression in human disease.

Finally, a given TF typically binds thousands to hundreds of thousands of genomic regions in a given cell type. Thus, the developmental defects upon loss of function of a cardiac TF likely result from pleiotropic effects on many target genes. This may also explain why abnormal expression of a single TF (loss or gain of expression) sometimes leads to almost coherent switches of transcriptional programs. A telling example is the atrial-expressed COUP-TFII transcription factor, which controls a gene network that leads to ventricularized atria when disrupted during embryonic development, and atrialized ventricles when ectopically expressed 61.

Connecting the dots between aberrant TF expression, target gene dysregulation and phenotypic defects is a daunting task. Furthermore, binding events of cardiac TFs are mostly found remote from promoters of coding genes, further complicating identification of target genes. This suggests that TFs rely on mechanisms to convey regulatory information from their actual binding site at a distance to target promoters. How to identify functional regulatory elements and the mechanisms underlying long-range transcriptional control is discussed below.

II. Enhancer elements

In this section, we discuss how cis-regulatory regions for cardiovascular development were identified based on structural properties, such as sequence conservation and chromatin features, or by functional assays. We then give contemporary examples illustrating how genomic approaches can benefit our understanding and discuss ways to study the function of these regulatory regions for cardiac biology.

“Regulatory sequences” are defined by their ability to control gene expression. Different classes of regulatory elements 57, including promoters, enhancers, silencers, and insulators, were historically defined by functional behavior of these sequences in reporter assays. However, a strict distinction between these elements can be difficult: promoters can function as insulators, and enhancer elements can initiate transcription. An effect on gene expression is a feature of a regulatory element, but also of the target. In particular, we consider an “enhancer” as a functional qualifier for a DNA sequence, rather than an intrinsic property. Its ability as an enhancer depends on the nature of the target promoter, as well as the effect considered (e.g., transcript level or spatio-temporal pattern of expression). Since an “enhancer” effect is context-dependent, we use “element” or “TF binding site” for the physical entity and reserve the term “enhancer” for situations of an implied regulatory function.

Most TF binding events occur outside of promoters 62. “Promoter” refers to the region directly upstream of the transcription initiation site (TSS) of a gene, and typically cannot mediate efficient transcription alone 63. Transcriptional activity of promoters is under the control of cis-acting sequences, known as enhancers or cis-regulatory modules (CRMs). These can be upstream or downstream from the target promoter, within introns or exons, and can reside tens to hundreds of kilobases away from their target promoter. Notably, distal cis-regulatory elements outnumber mRNA promoters by at least one order of magnitude 64,65.

Enhancers are more tissue-specific than promoters 66. Though most enhancers are active in several related cell types, enhancer activation seems to be tightly linked with TFs that define cell-type identity. This property was historically a defining feature of developmental enhancers: they drive expression of reporters in a tissue-restricted or developmental stage-specific fashion.

Since many regulatory regions are composed of several TF binding sites, regulatory regions can act differently depending on the specific combination of TFs expressed in that cell type. This enables CRMs to integrate input of multiple TFs, leading to a specific regulatory output depending on the TF combination. As most signal transduction pathways culminate in modulating TF function by post-translational modifications, this also means that CRMs represent genomic integration hubs for external signaling cascades 67.

We now review strategies to identify cis-regulatory regions for the emergence and differentiation of the cardiac lineage. We then discuss mechanisms by which they orchestrate transcriptional dynamics. Finally, we tie these insights to what is known and what remains to be understood about transcriptional regulation during heart development and homeostasis. Our discussion will mainly involve enhancer elements, as recent years have witnessed considerable progress in our understanding of this type of regulatory elements.

Identifying enhancers by non-coding sequence conservation

With the functional importance of cis-regulatory elements, evolutionary conservation can be leveraged to identify important non-coding regions, some of which may act as enhancers. A common approach has been to survey the genomic neighborhood of a gene of interest for conserved sequences (Figure 2A). Then, short fragments are assessed to determine if they drive expression of a reporter in a fashion that is reminiscent of the gene’s expression pattern. This strategy is performed in cell lines or transgenic animals.

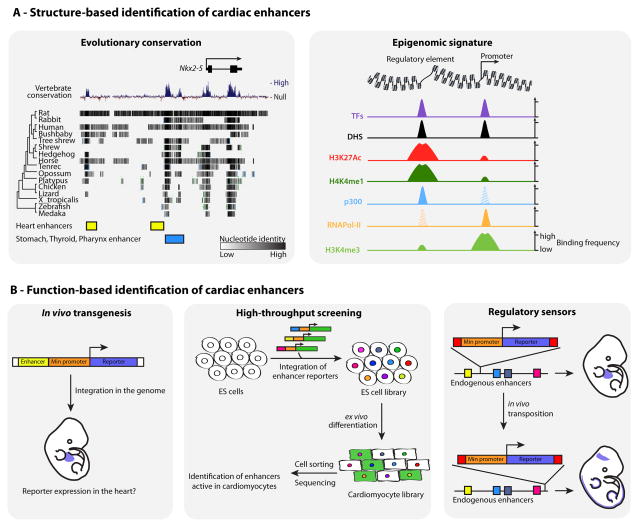

Figure 2. Studying cardiac regulatory elements.

(A) (Left) Evolutionary constraints on some regulatory elements render them identifiable by comparative genomics, as exemplified by enhancers upstream of mouse Nkx2-5 79. (Right) Combinations of specific chromatin features can reveal potential regulatory elements active in a given cell type. (B) (Left) Enhancer activity is classically tested by an ability of candidate elements to drive tissue- or stage-specific activity of a reporter. (Middle) New technologies, such as SIF-seq 76, allow screening of large genomic neighborhoods for tissue-specific enhancers. (Right) GROMIT 81 is a technology that can reveal integrated regulatory inputs exerted at a locus.

Once a minimal element is defined, potential DNA binding sites, and putative TFs that bind them can be identified. By creating enhancer variants, nucleotides that matter most for the enhancer activity can be identified, a strategy commonly referred to as “enhancer bashing”. Identifying transduction pathways connected to these TFs can ultimately reveal the external signals that are responsible for controlling expression of a gene of interest. For example, a Vegf/MAPK-dependent transcriptional pathway specifies arterial identity during cardiovascular development by activating an enhancer of Dll4, a Notch signaling component 68. In a reciprocal way, reporter assays containing enhancer elements and a basal promoter can be used to identify candidate TFs that regulate specific enhancers. This approach revealed that Myocardin co-activates Srf 21 and Hey proteins repress Gata factors 69.

A strength of this approach is that it relies on genomic sequence. Thus, it can uncover regions that are active transiently or in a handful of cells. However, it is also limited. First, the regulatory neighborhood can be tens or hundreds of conserved regions. Second, it assumes genes with conserved expression patterns are controlled by conserved enhancers, which may not be true. Surprisingly, there is a loose correlation between enhancer activity and evolutionary constraint in the heart 70. Evolutionary conservation of heart enhancers correlates with the developmental stage at which they are active, with the tightest conservation during early cardiac development 71.

Surveying regions of evolutionary conservation near cardiac genes genome-wide identified several enhancers, including human cardiac enhancers 72,73. However, a large population of cardiac enhancers marked by p300 are poorly conserved 70, and only developmental enhancers are ultra-conserved 74. Thus, evolutionary conservation may not discover many cardiac developmental enhancers.

Identifying enhancers by chromatin structure

Other methods to identify cardiac enhancers are based on structural features of chromatin. A major difference with the evolutionary approach is that, unlike DNA sequences, chromatin structure depends on the cell type. Binding of TFs to cis-regulatory elements and transcriptional activation is accompanied by changes in chromatin features, such as histone modifications, nucleosome remodeling, DNA demethylation and higher-order reorganization. All can be surveyed to identify regulatory elements across the genome and infer their activity state in a cell type or tissue being profiled.

For example, p300 catalyzes histone-3 lysine-27 acetylation (H3K27ac) at active promoters and enhancers, revealing the genomic location of these elements during heart development 70, 71 or cardiac differentiation 75. Likewise, H3K27me3 enrichment denotes elements repressed by the Polycomb machinery, H3K4me3 marks promoters, and H3K4me1 represents a general signature of enhancers (Figure 2A). Acquisition of promoter and enhancer activity has been classified during developmental transitions for cardiac differentiation in vitro 75,76, embryonic and adult mouse hearts in vivo 65,71 and human heart tissue 77.

TF binding to DNA creates local nucleosome-depleted regions, and general accessibility of their chromatin is another hallmark of cis-regulatory elements. In vitro DNAseI treatment preferentially cleaves accessible genomic DNA, with DNAse-hypersensitive sites (DHSs) highlighting TF binding events and delineating regulatory elements 78,79. As steric hindrance protects nucleotides contacted by TFs from DNAse digestion, DNAseI profiling can identify TF footprints and infer the underlying TFs from the protected motifs. Other methods to assess open chromatin include formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory and sequencing (FAIRE-seq) 80 and assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq) 81. However, it is unclear how structural features relate to enhancer function, and our incomplete understanding of enhancer activity prompts a parallel use of functional screening assays.

Identifying enhancers by regulatory function

Classical approaches consist of cloning candidate enhancer sequences next to a heterologous promoter driving the expression of a reporter (Figure 2B). The construct can be introduced in cultured cells or transgenic animals, as a transient episome or stably integrated in the genome and fully chromatinized. In an early example, a rat Nppa enhancer was identified by transient transfections in cardiomyocytes 82,83,84. Many enhancer regions of cardiac genes have been evaluated using this approach 70,72,74,77.

A promising technology to assess enhancer activity in a high-throughput fashion is based on self-transcribing active regulatory region sequencing (STARR-seq, 85). Bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) or whole genomes are fragmented and cloned downstream of a minimal promoter whose activity is measured by RNA-seq after non-integrative introduction into cells. Surprisingly, about a third of sequences that drive high levels of reporter activity as ectopic episomes reside in closed chromatin in their genomic context. This is attributed to repressive mechanisms that prevent enhancer activity from these sequences in the genome, and illustrates that caution should be taken when inferring endogenous regulatory activity from ectopic non-chromatinized reporters 85. STARR-seq remains to be applied genome-wide in mammals.

Additive transgenesis, meaning ectopic integration of DNA fragments, has been used to find regulatory elements within a region of interest (Figure 2A). This labor-intensive approach remains the gold-standard demonstration of regulatory activity in vivo and in a genomic context. It also revealed the integrated nature of cis-regulatory elements. Studies at the mouse Nkx2-5 locus revealed that enhancer activity of transgenes can be blocked or unleashed by including or excluding a few hundred base pairs 86. The underlying mechanisms remain unknown, but likely involve cross-talk of different TF binding sites within the same regulatory regions and coexistence of activating and repressing TF binding events in the same region.

Recent developments allowed scaling-up the throughput of additive transgenesis. One approach relies on fragmentation of BACs into small fragments that are tested for their ability to drive expression of a fluorescent reporter integrated in a precise genomic location 87 (Figure 2B). Use of embryonic stem cells for such an assay allows differentiating them into other cell types. Differentiation into cardiomyocytes revealed unappreciated regulatory dynamics across 200 kb at the MYH7/MYH6 locus.

Many have also cloned larger DNA fragments into BACs and integrated these constructs into the genome to assess reporter expression. This technique was used to identify distal enhancers for Nppa 88 and Nppb 89. However, after decades of searching for enhancers of cardiac genes, including Nkx2-5 90, it remains challenging to find combinations of elements that recapitulate a gene’s endogenous cardiac expression. Some genes are likely controlled by multiple and sometime interdependent regulatory elements, with regulatory communication depending on genomic organization of the locus 91.

A converse approach to additive transgenesis consists of interrogating regulatory activity directly from the endogenous genomic context, by integrating regulatory sensors in a region to be surveyed. Genome Regulatory Organization Mapping with Integrated Transposons (GROMIT) is a method that allows in vivo transposon-assisted lacZ reporter integration at sites throughout the genome 92 (Figure 2B). An ongoing effort to create a regulatory atlas of the genome has already revealed tens of non-coding genomic loci with heart-enriched regulatory activity that remain to be investigated 93.

Exploring the role of cis-regulatory elements

The above assays monitor the potential of a regulatory region. Once a sequence is identified to drive the desired expression pattern in reporters, a fundamental question remains. Is the sequence necessary to pattern the expression of its target gene in its genomic context?

Functional testing in vivo for necessity can be assessed by loss of function of an enhancer element. In the limb, the zone of polarizing activity (ZPA) regulatory sequence, which is mutated in the Sasquatch and hemimelic extra toes (Hx) mice along with some patients with polydactyly, is 1 Mb from its target gene, Shh 94. Deletion of the branchial-arch enhancer of Hand2 demonstrates a necessary role for craniofacial development 95, and deletion of craniofacial enhancers for Msx1, Snai2 or Isl1 display subtle yet quantifiable morphometric anomalies 96.

Our view of enhancers may be biased: many enhancers were identified because their alterations lead to observable phenotypes. Loci harboring genes important for development are typically populated by many cell-type specific enhancers. What would happen upon deletion of only one of them? Or combinations? This remains to be explored.

The field still awaits identification of cardiac enhancers necessary for heart development. Maybe too few candidates have been tested. Other biological reasons may be involved, including the distributed and redundant nature of regulatory elements 97. Alternatively, certain enhancers may control subtle traits that require thorough phenotyping. Clearly, deeper exploration of the functional relevance of cis-regulatory elements for cardiac development and homeostasis is an exciting research avenue.

How does transcription factor binding confer regulatory activity?

The answer is unclear. A TF might act through different mechanisms, depending on many features, such as the nature of the bound DNA sequence, the presence of co-factors, and the nature of the target promoter 57. Most TFs rely on several intermediate steps to control core transcriptional machinery.

One intermediate, the Mediator complex, contains several subunits that bind TFs and recruit general TFs or RNA polymerase (Figure 1B). Some mediator subunits are constitutive, and others are tissue-specific 98. Missense mutations in some subunits (e.g., MED13, MED15) are associated with cardiovascular abnormalities in humans 99, and mutations in Med30 lead to cardiomyopathies in the mouse 100. The reason for the cardiac-specific phenotype of these mutations is unclear.

As mentioned above, enhancer regions rarely contain a single TF binding site. They often involve clusters of binding sites, suggesting that binding of one TF modulates the binding of others and the functional output on transcription. Several models have been proposed 57. In the “enhanceosome” model 101, TFs interact with strict cooperativity. Their interactions are allowed by motif positioning within an enhancer, and all TFs need to be bound to activate the enhancer. DNA and TFs form a higher-order protein complex that provides an integrated activity of all TFs. However, most developmental enhancers do not work so rigidly. The “billboard” model posits that TF binding does not rely on physical interaction with each other, meaning that positioning of TF binding sites is flexible 102. Cooperativity in binding and output may occur for enhancer activity even if all binding sites are not occupied. A composite model, called “TF collective” combines flexible grammar with TF-TF physical interaction. Thus, the TF cohort occupies each individual enhancer in many combinations of TF-DNA contacts or protein-protein interactions 103. This model may account for the occupancy and activity of cardiac enhancers in Drosophila, with a cardiac TF collective comprising Mad/Smad, Tcf, Tin/Nkx2-5, Dorsocross/Tbx5 and Pannier/Gata 103.

Importance of cooperativity between transcription factors

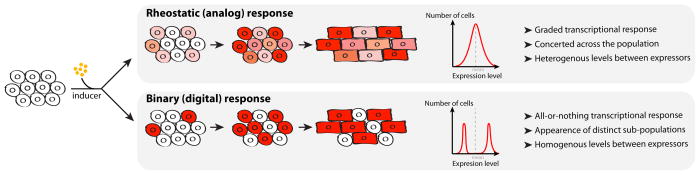

Although common, cooperativity in DNA binding is not observed at all regulatory elements 104. This is important, since it drastically affects the transcriptional response. High cooperativity means that an enhancer exists in two states: bound by few TFs and inactive, or bound by many TFs and active. High DNA binding cooperativity is associated with a digital on/off response to changes in TF availability. On the other hand, DNA binding without cooperativity means that enhancers exist with a wide range of activity, based on how many TFs are bound. Non-cooperative interactions provide a molecular basis for an analog or graded transcriptional response 105 (Figure 5). This aspect is especially relevant when considering heart diseases originating from heterozygous loss of function of cardiac TFs, where TF availability is compromised. As well, it will be interesting to determine if the occupancy of many cardiac TFs is interdependent. Understanding what genes are dysregulated because of disruptions of regulatory elements may elucidate molecular mechanisms behind these cardiac defects.

Figure 5. Population vs. single-cell approaches for gene expression.

Insights from cell population–based studies reveal global changes in fields of cells or tissue during cardiac differentiation and development. However, cell heterogeneity can obscure gene expression analysis from cell populations. Two distinct modes of transcriptional responses, rheostatic (or analog) and binary (or digital), give similar mean behaviors on a population scale. Yet, in a rheostatic regime, cells respond in a concerted fashion homogeneously, while a binary regime leads to the appearance of populations with expressers or non-expressers. During development, this can have fundamental consequences on how cells differentiate. Of importance, long-range activation by enhancers acts through a binary mechanism, therefore contributing of cell-to-cell heterogeneity 139.

Heterogeneity in the initial responsive population must also be considered (Figure 5). The heart comprises four distinct chambers, atrioventricular and semilunar valves, composed of various cell types and subtypes, including cardiomyocytes, cardiac fibroblasts, endocardial, epicardial, conduction and mesenchymal cells, each with different transcriptional programs. Using methods for single-cell gene expression profiling, analysis at single-cell resolution may clarify contributions of different cell types to cell populations of the heart, as well as heterogeneity within each cell type and subtype. This approach has yielded insights for the reprogramming field, with relevance to cardiac development: Single-cell analysis of reprogrammed human fibroblasts to induced cardiomycytes (iCMs) showed gene expression variability among iCMs 10. In another example, single-cell analysis of reprogramming fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) revealed stochastic gene expression changes early, followed by an hierarchical period of gene expression for activation of the endogenous pluripotency program 106. Consequently, application of single-cell analysis to cardiovascular development may elucidate how cardiac cell identity is acquired, perhaps by stochastic (digital) or rheostatic (analog) transcriptional mechanisms 105,107 at different stages of cardiac differentiation and heart development.

Enhancer-promoter interactions

How does TF binding occur thousands to hundreds of thousands of bases from core promoter elements to impact transcriptional activity? How does a regulatory region affect specific promoters among many? Studies focused on large-scale organization of chromosomes are addressing these questions. Chromosome conformation capture (3C) technologies 108 demonstrated that distal enhancers engage physical contacts with promoter(s) that they control. This property can be used to identify regulatory elements for a gene of interest, or conversely, target promoters of an enhancer of interest. By circular chromosome conformation capture (4C)-seq analysis, which evaluates multiple genomic loci to a fixed DNA location, the promoter of the Scn5a gene, encoding a sodium channel involved in cardiac conduction, physically interacts with a novel cardiac enhancer in the intron of the Scn10 gene in mouse heart 109. This region encompasses a functional variant in human arrhythmias. The disease-associated variant changes a T-box consensus binding site 56, impairs enhancer activity in transgenic animals 56,109 and correlates with a reduction of SCN5A expression in humans 109.

Enhancer-promoter specificity is controlled by chromatin folding. Chromosomes are organized in a series of packaging blocks, known as Topologically Associating Domains (TADs, Figure 1C). Enhancer-promoter interactions might be less specific than initially thought; different promoters may be affected by many enhancers within the same TAD 110. Partitioning of chromosomes in TADs prevents regulatory cross-talk between enhancers and promoters located in different TADs 111. Such a principle is at play at the Tbx3/Tbx5 locus. Tbx3 is within one TAD, which contains heart-specific enhancers of Tbx3, and Tbx5 is in another TAD with its own enhancers 112.

It is not clear what drives chromosome folding into TADs. It may rely on a class of cis-regulatory regions distinct from enhancers, sometimes referred to as “architectural elements”, which bind TFs that do not connect with the transcription apparatus, but control targeting of neighboring enhancers to promoters. Nevertheless, these are bona fide cis-regulatory elements, as their disruption disturbs gene expression, presumably by altering chromosome folding 111. From these observations, a picture emerges in which a DNA sequence controls where TFs bind and their ability to cross-talk. Chromosome folding guides the targeting of enhancers, while recruitment of generic and tissue-specific co-factors enables assembly of core transcriptional machinery at promoters.

II. Developmental dynamics of transcriptional regulation

Two questions are not answered by the temporally static view of transcriptional regulation: why does a TF only bind a subset of its cognate binding sites in a given cell type and why do these differ between cell types or developmental stages? We discuss how the regulatory function of DNA sequences is affected by cellular history of the genome. We then discuss how regulatory networks formed from TFs and cis-regulatory elements facilitate patterning and memory of transcriptional activity.

Nuclear transfer and cell fusion experiments using two somatic cell types revealed that transcriptional changes are generally very limited (unlike when fusing a pluripotent and a somatic cell)113. This means that the TFs’ milieu from a somatic cell type is largely incapable of using the genomic template of another somatic cell type, highlighting that cis-acting information in addition to the DNA sequence guides how TFs control transcriptional activity.

Epigenetic priming

Exposure to a TF may result in transcriptional activation if the chromatin context is permissive to TF binding and activity. In this situation, developmental patterning of chromatin is necessary for TFs to affect transcription. For example, TF binding is influenced by DNA methylation, histone modifications, nucleosome positioning and co-factor anchoring to chromatin 114. Reorganizing chromatin can modulate TF activity by controlling physical proximity between distal regulatory regions and can be developmentally modulated 115. Epigenetic priming refers to a pre-requisite for transcriptional activity, but may not result in activation (Figure 3). Priming is epigenetic in that a permissive state is an acquired property transmitted through cellular generations and does not require persistent expression of the priming factor 116. Conversely, occlusis is a developmentally acquired repression, leading to inability of a promoter to react to the TF milieu 117. Therefore, one must consider properties of the epigenome (the structural features of chromatin and chromosomes) to understand how TFs pattern transcriptional activity during development.

Figure 3. Developmental patterning of regulatory elements.

(A, B) Dynamics of transcriptional activity can result from stage-specific action of transactivators or repressors. (C) Cellular history of the genome can also influence transcriptional responses, such as by epigenetic priming of regulatory elements.

Epigenetic priming during cardiac development became evident upon inspection of chromatin states during cardiomyocyte differentiation from mouse ES cells 75. Several hundreds of promoters gained H3K4me1, a signature suggestive of TF binding at an early stage of differentiation, without signs of transcriptional activation. Upon cardiac progenitor and cardiomyocyte differentiation from this early population, a subset was transcriptionally activated, illustrating how priming can potentiate but not commit to transcriptional activation. Although such a phenomenon is not specific to the cardiac lineage, TFs responsible for such patterning remain to be identified, and their roles for cardiac differentiation are unexplored.

Chromatin state modulates transcription factor activity and vice-versa

Chromatin structure and TF binding are engaged in a two-way relationship, with one affecting the other, positively or negatively, depending on the context. Post-translational histone modifications and chromatin-binding proteins are involved in such cross-talk. For example, Polycomb-mediated H3K27me3 prevents transcriptional activation by TFs, while transcriptional activation by TFs prevents Polycomb-mediated repression 118 and is important for gene expression during cardiac development and homeostasis in the adult heart 37,38.

What are the molecular initiators of these transitions in chromatin structure? Some TFs penetrate the chromatin barrier, and their binding represents a pioneering event in the molecular cascade that ultimately leads to transcriptional activation at later developmental stages 119. Importantly, pioneering activity is not completely intrinsic to these TFs, but depends on DNA sequence around the direct binding site of the TF 51. For example, the same TF may initiate nucleosome remodeling at some sites but not others. So, “pioneer” refers more to its activity than to the TF itself.

An alternative yet non-exclusive mechanism is the tissue-specific expression of nucleosome remodelers that bind TFs, allowing TFs to access their binding sites. For example, Baf60c, a cardiac-specific subunit of the SWI/SNF Brg1/Brm-associated factor (BAF), is necessary for differentiation of cardiomyocytes in mouse and zebrafish 120. Baf60c physically interacts with Gata4 and stimulates the association of Tbx5 and Nkx2-5 with Brg1 23, suggesting that Baf60c modulates access of TFs to their binding sites in chromatin. Interestingly, proper cardiac differentiation requires an exquisite stoichiometry between TFs, exemplified by the genetic interaction between heterozygosity of Tbx5, Tbx20 or Nkx2-5 and Brg1 121. Other cardiac TFs physically interact with chromatin-modifying enzymes, mostly through candidate approaches. For example, Gata4 and Hopx associate with Hdac2 122 and Gata4 interacts with PRC2 subunits 44. From yeast two-hybrid systems, Mef2c interacts with class II HDACs 123. How chromatin remodelers modulate TF action is unknown.

Relevance for experimental manipulation of cellular states

Control of TF accessibility is a central question in the field of reprogramming, where ectopic TF expression drives transcriptional changes, ultimately resulting in the acquisition of a new cellular phenotype. Self-perpetuation of chromatin states exerts an impediment to the efficiency of TF-mediated reprogramming 124. Interestingly, trans-differentiation of fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes is possible by ectopic expression of Gata4, Mef2c and Tbx5 in the mouse 8,9,125, though it requires additional factors in human 10,11. In mouse embryos, adding Baf60c to Tbx5 and Gata4 facilitates ectopic cardiac trans-differentiation of mesoderm 6. Although it is possible to trans-differentiate cells, the efficiency is low and suggests ectopic TFs encounter barriers that remain to be overcome. Concomitant manipulation of the epigenome is a promising avenue under investigation 124.

Transcription factor-to-transcription factor: building a regulatory network

If a TF binds to a regulatory region of a gene encoding another TF and controls its expression, this relationship establishes a regulatory network (Figure 4). Aside from information stored in chromatin structure, the topology of a TF regulatory network itself is another way to instruct the execution of a transcriptional program and implement cellular memory. Deciphering the architecture of such regulatory networks allows pivotal factors to be identified. Some TFs may push developmental programs forward, and others may stabilize cell identity 78,79.

Figure 4. Building regulatory circuits to implement developmental patterning.

Simple network motifs allow the emergence of temporal patterning for transcriptional responses. (A) Positive feedback, direct or indirect, can establish cellular memory of an exposure from transient events. (B) An incoherent feed-forward loop can generate a transient expression pulse. (C) TFs and cis-regulatory elements are molecular building blocks of transcriptional networks. As TFs control activity of other TF genes, they create functional connections that organize into regulatory modules, which can be assembled into complex stage- and tissue-specific regulatory networks for transcriptional patterning.

A positive feedback loop, when a TF reinforces its own expression (directly or indirectly), is the simplest regulatory network, and enables self-perpetuation and stability of cellular states (Figure 4A). However, positive feedback loops rarely exist in isolation, as continuous autostimulation would result in an explosive increase in gene activity. Autostimulatory loops are often embedded in larger circuits that include negative regulation. This balance between positive and negative feedback determines the output of transcriptional activity (Figure 4B). With more intermediates in a pathway, there is more opportunity to influence and divert a cell from its stable state. For example, exposure to external signals can lead to directed differentiation of embryonic stem cells to cardiomyocytes 4,5. The reconstruction of regulatory networks through genome-wide assays opens an opportunity to investigate this topic in the context of cardiac cell differentiation 75,78,76.

Combinations of simple “network motifs” may be enough to explain many cellular behaviors (Figure 4C). When a TF controls a target directly and indirectly, it forms a feed-forward loop. Counterintuitively, feed-forward loops are often incoherent, meaning that the TF activates its target on the one hand and represses it on the other 126. Network motifs involving negative regulation can implement temporal dynamics, such as oscillations or pulses in gene expression. This situation is particularly relevant for developmental contexts where a pool of progenitors needs to arise and expand before subsequent differentiation. For example, Nkx2-5 represses genes important for cardiac progenitor proliferation while repressing its own expression through a negative feedback loop involving Bmp2 and Smad signaling 127. The time lag for the negative feedback to operate allows initial cardiac induction and ensures that a break in proliferation only operates after progenitors have arisen.

Developing quantitative approaches to study regulatory networks underlying cardiac development is a formidable challenge, experimentally and computationally. Moving forward will require gathering developmental, molecular and computational biologists. Such integrated approaches have proved valuable in the fly, where information about TF occupancy and transgenic enhancer assays trained a machine-learning algorithm to predict spatio-temporal activity of cis-regulatory elements 128. The recent genome and epigenome engineering revolution offers an unprecedented way to functionally study these networks, in cellular or animal models 129. Though a global understanding of the transcriptional control of cardiac development is not yet within our grasp, pieces of a cardiovascular regulatory network are starting to be unraveled, and are already yielding tremendous insights in the understanding of human cardiac defects.

Conclusions and prospects

In summary, we present general principles to better understand transcriptional control of gene expression during cardiac development. Many cardiac TFs bind to selective DNA sites in regulatory elements, with co-factors and chromatin, to activate cardiac gene expression. Mechanistic diversity for transcriptional regulation is such that each gene might constitute an exception to the general rule. Enhancers may go beyond a sequence-based code, likely involving contributions from genomic organization. Cooperativity of TF binding through protein interactions at enhancers defines modes of target promoter activation. Higher-order chromosomal organization fosters functional cross-talk between control elements in regulatory neighborhoods within TADs. How TFs behave depends on chromatin changes at earlier developmental stages, and at the same time, influences future changes in gene expression. Understanding the nature of regulatory connections between TF proteins and TF genes is key to deciphering molecular mechanisms driving temporal dynamics during developmental patterning. This holds great promise for our comprehension of developmental defects, such as CHDs, where the disruption of one of these nodes may result in pathogenic consequences on many participants of the regulatory network.

For human disease, TF heterozygosity can lead to haploinsufficiency and is a frequent cause of inherited CHD. However, how reducing cardiac TF dosage leads to cardiac defects is not known. Investigation has been hampered by lack of relevant and tractable models in humans and animals. With a few notable exceptions, many mouse models of heterozygous deletions do not recapitulate phenotypic aspects of human disease. Tbx5 heterozygosity causes VSDs, ASDs, and arrhythmias, along with upper limb anomalies reminiscent of HOS, consistent with TF haploinsufficiency 31. Tissue-specific heterozygous deletion of Tbx5 in the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion (DMP) results in ASDs, implicating Tbx5 in the second heart field 130. Interestingly, discovery that Tbx5 haploinsufficiency in mice causes diastolic dysfunction prompted an evaluation of a cohort of HOS patients, which detected diastolic dysfunction 131 that has implications for clinical management.

Genetic modifiers likely contribute as genetic buffers for human health or as perturbations in polygenic human disorders, including many human CHDs. Phenotypes of a few mouse models are strain dependent, including for Tbx5 31 or Nkx2-5 132. Attempts to identify modifier genes of Nkx2-5 for VSDs or ASDs have revealed strain-dependent susceptibility loci that were shared or distinct based on the anomaly 133. However, specific polymorphisms for genetic modifiers have not yet been identified. The advent of iPSC technology 134 from human fibroblasts now allows study of a mixed genetic background derived from patients’ cells. In conjunction with directed cardiac differentiation of human 5 or mouse 4 PSCs, mechanisms for cardiac differentiation can be studied with a scalable method using cellular models.

An integrated understanding of TF networks during cardiac development can provide invaluable information to understand mechanisms of cardiac disease and vice versa. In the near future, it will be interesting and important to determine if SNPs identified by GWAS for CHDs 135,136, CAD 137,138, cardiac hypertrophy and arrhythmias might alter nodes for potential cardiac regulatory networks of different functions. Conversely, GWAS may reveal nodes of cardiac regulation that are clinically relevant to disease. These mechanistic insights may shed light on novel therapeutic targets and may lead to new treatment strategies including regenerative approaches for cardiovascular medicine.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to our colleagues whose work was not presented or cited due to space constraints. We thank members of the Bruneau laboratory for constructive comments, John Wylie for illustrations, Juan Perez-Bermejo for a diagram, and Gary Howard for editorial assistance.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

I.S.K. is supported by the Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research, and the John W. Severinghaus Endowment, E.P.N. is supported by the European Molecular Biology Organization (ALTF523-2013) and Human Frontier Science Program, and B.G.B. is supported by grants from the NIH/NHLBI (Bench to Bassinet Program U01HL098179), the Lawrence J. and Florence A. DeGeorge Charitable Trust/American Heart Association Established Investigator Award, and William H Younger, Jr.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- TF

transcription factor

- CHD

congenital heart disease

- PSC

pluripotent stem cell

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

- Pol II

RNA polymerase II

- EST

expressed sequence tag

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- ENU

N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea

- HOS

Holt-Oram syndrome

- ASD

atrial septal defect

- PRC2

Polycomb repressive complex-2

- SILAC

stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture

- MITOMI

mechanically induced trapping of molecular interactions

- EMSA

electromobility shift assay

- ChIP-seq

chromatin immunoprecitipation with sequencing

- HT-SELEX

high throughput systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment

- HiTS-FLIP

high-throughput sequencing-fluorescent ligand interaction profiling

- TSS

transcription initiation site

- CRMs

cis-regulatory modules

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- FAIRE-seq

formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory and sequencing

- ATAC-seq

assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing

- H3K27ac

histone-3 lysine-27 acetylation

- H3K27me3

histone-3 lysine-27 tri-methylation

- H3K4me1

histone-3 lysine-4 mono-methylation

- H3K4me3

histone-3 lysine-4 tri-methylation

- STARR-seq

self-transcribing active regulatory region sequencing

- BACs

Bacterial artificial chromosomes

- ZPA

zone of polarizing activity

- 3C

Chromosome conformation capture

- 4C

circular chromosome conformation capture

- TADs

Topologically Associating Domains

Footnotes

In December 2014, the average time from submission to first decision for all original research papers submitted to Circulation Research was 14.47 days.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Contributor Information

Irfan S. Kathiriya, Email: kathiriyai@anesthesia.ucsf.edu.

Elphege P. Nora, Email: elphege.nora@gladstone.ucsf.edu.

Benoit G. Bruneau, Email: bbruneau@gladstone.ucsf.edu.

References

- 1.Bruneau BG. The developmental genetics of congenital heart disease. Nature. 2008;451:943–948. doi: 10.1038/nature06801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lalani SR, Belmont JW. Genetic basis of congenital cardiovascular malformations. Eur J Med Genet. 2014;57:402–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCulley DJ, Black BL. Transcription factor pathways and congenital heart disease. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2012;100:253–277. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387786-4.00008-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kattman SJ, Witty AD, Gagliardi M, Dubois NC, Niapour M, Hotta A, Ellis J, Keller G. Stage-specific optimization of activin/nodal and BMP signaling promotes cardiac differentiation of mouse and human pluripotent stem cell lines. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:228–240. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mummery CL, Zhang J, Ng ES, Elliott DA, Elefanty AG, Kamp TJ. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells to cardiomyocytes: a methods overview. Circ Res. 2012;111:344–358. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeuchi JK, Bruneau BG. Directed transdifferentiation of mouse mesoderm to heart tissue by defined factors. Nature. 2009;459:708–711. doi: 10.1038/nature08039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ieda M, Tsuchihashi T, Ivey KN, Ross RS, Hong T-T, Shaw RM, Srivastava D. Cardiac fibroblasts regulate myocardial proliferation through beta1 integrin signaling. Dev Cell. 2009;16:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qian L, Huang Y, Spencer CI, Foley A, Vedantham V, Liu L, Conway SJ, Fu J-D, Srivastava D. In vivo reprogramming of murine cardiac fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes. Nature. 2012;485:593–598. doi: 10.1038/nature11044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song K, Nam Y-J, Luo X, Qi X, Tan W, Huang GN, Acharya A, Smith CL, Tallquist MD, Neilson EG, Hill JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Heart repair by reprogramming non-myocytes with cardiac transcription factors. Nature. 2012;485:599–604. doi: 10.1038/nature11139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu J-D, Stone NR, Liu L, Spencer CI, Qian L, Hayashi Y, Delgado-Olguín P, Ding S, Bruneau BG, Srivastava D. Direct Reprogramming of Human Fibroblasts toward a Cardiomyocyte-like State. Stem Cell Reports. 2013;1:235–247. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nam Y-J, Song K, Luo X, Daniel E, Lambeth K, West K, Hill JA, Dimaio JM, Baker LA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Reprogramming of human fibroblasts toward a cardiac fate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110:5588–5593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301019110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fromm G, Gilchrist DA, Adelman K. SnapShot: Transcription regulation: pausing. Cell. 2013;153:930–930. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris KV, Mattick JS. The rise of regulatory RNA. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:423–437. doi: 10.1038/nrg3722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith E, Shilatifard A. Transcriptional elongation checkpoint control in development and disease. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1079–1088. doi: 10.1101/gad.215137.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bodmer R, Jan LY, Jan YN. A new homeobox-containing gene, msh-2, is transiently expressed early during mesoderm formation of Drosophila. Development. 1990;110:661–669. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.3.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bodmer R. The gene tinman is required for specification of the heart and visceral muscles in Drosophila. Development. 1993;118:719–729. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.3.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azpiazu N, Frasch M. tinman and bagpipe: two homeo box genes that determine cell fates in the dorsal mesoderm of Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1325–1340. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7b.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lints TJ, Parsons LM, Hartley L, Lyons I, Harvey RP. Nkx-2.5: a novel murine homeobox gene expressed in early heart progenitor cells and their myogenic descendants. Development. 1993;119:419–431. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.2.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Srivastava D, Cserjesi P, Olson EN. A subclass of bHLH proteins required for cardiac morphogenesis. Science. 1995;270:1995–1999. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5244.1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ranganayakulu G, Elliott DA, Harvey RP, Olson EN. Divergent roles for NK-2 class homeobox genes in cardiogenesis in flies and mice. Development. 1998;125:3037–3048. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.16.3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang D, Chang PS, Wang Z, Sutherland L, Richardson JA, Small E, Krieg PA, Olson EN. Activation of cardiac gene expression by myocardin, a transcriptional cofactor for serum response factor. Cell. 2001;105:851–862. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00404-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gottlieb PD, Pierce SA, Sims RJ, Yamagishi H, Weihe EK, Harriss JV, Maika SD, Kuziel WA, King HL, Olson EN, Nakagawa O, Srivastava D. Bop encodes a muscle-restricted protein containing MYND and SET domains and is essential for cardiac differentiation and morphogenesis. Nat Genet. 2002;31:25–32. doi: 10.1038/ng866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lickert H, Takeuchi JK, Both Von I, Walls JR, McAuliffe F, Adamson SL, Henkelman RM, Wrana JL, Rossant J, Bruneau BG. Baf60c is essential for function of BAF chromatin remodelling complexes in heart development. Nature. 2004;432:107–112. doi: 10.1038/nature03071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hang CT, Yang J, Han P, Cheng H-L, Shang C, Ashley E, Zhou B, Chang C-P. Chromatin regulation by Brg1 underlies heart muscle development and disease. Nature. 2010;466:62–67. doi: 10.1038/nature09130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhong TP, Rosenberg M, Mohideen MA, Weinstein B, Fishman MC. gridlock, an HLH gene required for assembly of the aorta in zebrafish. Science. 2000;287:1820–1824. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iso T, Kedes L, Hamamori Y. HES and HERP families: Multiple effectors of the notch signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2003;194:237–255. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu Q. ENU induced mutations causing congenital cardiovascular anomalies. Development. 2004;131:6211–6223. doi: 10.1242/dev.01543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costello I, Pimeisl I-M, Dräger S, Bikoff EK, Robertson EJ, Arnold SJ. The T-box transcription factor Eomesodermin acts upstream of Mesp1 to specify cardiac mesoderm during mouse gastrulation. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1084–1091. doi: 10.1038/ncb2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basson CT, Bachinsky DR, Lin RC, Levi T, Elkins JA, Soults J, Grayzel D, Kroumpouzou E, Traill TA, Leblanc-Straceski J, Renault B, Kucherlapati R, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Mutations in human TBX5 [corrected] cause limb and cardiac malformation in Holt-Oram syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;15:30–35. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li QY, Newbury-Ecob RA, Terrett JA, et al. Holt-Oram syndrome is caused by mutations in TBX5, a member of the Brachyury (T) gene family. Nat Genet. 1997;15:21–29. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bruneau BG, Nemer G, Schmitt JP, Charron F, Robitaille L, Caron S, Conner DA, Gessler M, Nemer M, Seidman CE, Seidman JG. A murine model of Holt-Oram syndrome defines roles of the T-box transcription factor Tbx5 in cardiogenesis and disease. Cell. 2001;106:709–721. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00493-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bruneau BG, Logan M, Davis N, Levi T, Tabin CJ, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Chamber-specific cardiac expression of Tbx5 and heart defects in Holt-Oram syndrome. Dev Biol. 1999;211:100–108. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaidi S, Choi M, Wakimoto H, et al. De novo mutations in histone-modifying genes in congenital heart disease. Nature. 2013;498:220–223. doi: 10.1038/nature12141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ng SB, Bigham AW, Buckingham KJ, et al. Exome sequencing identifies MLL2 mutations as a cause of Kabuki syndrome. Nat Genet. 2010;42:790–793. doi: 10.1038/ng.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koshiba-Takeuchi K, Mori AD, Kaynak BL, et al. Reptilian heart development and the molecular basis of cardiac chamber evolution. Nature. 2009;461:95–98. doi: 10.1038/nature08324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nadeau M, Georges RO, Laforest B, Yamak A, Lefebvre C, Beauregard J, Paradis P, Bruneau BG, Andelfinger G, Nemer M. An endocardial pathway involving Tbx5, Gata4, and Nos3 required for atrial septum formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:19356–19361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914888107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He A, Ma Q, Cao J, Gise von A, et al. Polycomb repressive complex 2 regulates normal development of the mouse heart. Circ Res. 2012;110:406–415. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.252205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delgado-Olguín P, Huang Y, Li X, Christodoulou D, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Tarakhovsky A, Bruneau BG. Epigenetic repression of cardiac progenitor gene expression by Ezh2 is required for postnatal cardiac homeostasis. Nat Genet. 2012;44:343–347. doi: 10.1038/ng.1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garg V, Kathiriya IS, Barnes R, Schluterman MK, King IN, Butler CA, Rothrock CR, Eapen RS, Hirayama-Yamada K, Joo K, Matsuoka R, Cohen JC, Srivastava D. GATA4 mutations cause human congenital heart defects and reveal an interaction with TBX5. Nature. 2003;424:443–447. doi: 10.1038/nature01827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hiroi Y, Kudoh S, Monzen K, Ikeda Y, Yazaki Y, Nagai R, Komuro I. Tbx5 associates with Nkx2-5 and synergistically promotes cardiomyocyte differentiation. Nat Genet. 2001;28:276–280. doi: 10.1038/90123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsang AP, Visvader JE, Turner CA, Fujiwara Y, Yu C, Weiss MJ, Crossley M, Orkin SH. FOG, a multitype zinc finger protein, acts as a cofactor for transcription factor GATA-1 in erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation. Cell. 1997;90:109–119. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crispino JD. Proper coronary vascular development and heart morphogenesis depend on interaction of GATA-4 with FOG cofactors. Genes Dev. 2001;15:839–844. doi: 10.1101/gad.875201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Breker M, Schuldiner M. The emergence of proteome-wide technologies: systematic analysis of proteins comes to age. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:453–464. doi: 10.1038/nrm3821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He A, Shen X, Ma Q, Cao J, Gise Von A, Zhou P, Wang G, Marquez VE, Orkin SH, Pu WT. PRC2 directly methylates GATA4 and represses its transcriptional activity. Genes Dev. 2012;26:37–42. doi: 10.1101/gad.173930.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swaney DL, Beltrao P, Starita L, Guo A, Rush J, Fields S, Krogan NJ, Villén J. Global analysis of phosphorylation and ubiquitylation cross-talk in protein degradation. Nat Meth. 2013;10:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amin NM, Greco TM, Kuchenbrod LM, Rigney MM, Chung M-I, Wallingford JB, Cristea IM, Conlon FL. Proteomic profiling of cardiac tissue by isolation of nuclei tagged in specific cell types (INTACT) Development. 2014;141:962–973. doi: 10.1242/dev.098327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghosh TK, Packham EA, Bonser AJ, Robinson TE, Cross SJ, Brook JD. Characterization of the TBX5 binding site and analysis of mutations that cause Holt-Oram syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1983–1994. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.18.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Geertz M, Maerkl SJ. Experimental strategies for studying transcription factor-DNA binding specificities. Briefings in Functional Genomics. 2011;9:362–373. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elq023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chlon TM, Doré LC, Crispino JD. Cofactor-mediated restriction of GATA-1 chromatin occupancy coordinates lineage-specific gene expression. Mol Cell. 2012;47:608–621. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rhee HS, Pugh BF. Comprehensive genome-wide protein-DNA interactions detected at single-nucleotide resolution. Cell. 2011;147:1408–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barozzi I, Simonatto M, Bonifacio S, Yang L, Rohs R, Ghisletti S, Natoli G. Coregulation of Transcription Factor Binding and Nucleosome Occupancy through DNA Features of Mammalian Enhancers. Mol Cell. 2014;54:844–857. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parker SCJ, Stitzel ML, Taylor DL, et al. Chromatin stretch enhancer states drive cell-specific gene regulation and harbor human disease risk variants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110:17921–17926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317023110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Whyte WA, Orlando DA, Hnisz D, Abraham BJ, Lin CY, Kagey MH, Rahl PB, Lee TI, Young RA. Master transcription factors and mediator establish super-enhancers at key cell identity genes. Cell. 2013;153:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.He A, Kong SW, Ma Q, Pu WT. Co-occupancy by multiple cardiac transcription factors identifies transcriptional enhancers active in heart. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:5632–5637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016959108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schlesinger J, Schueler M, Grunert M, Fischer JJ, Zhang Q, Krueger T, Lange M, Tönjes M, Dunkel I, Sperling SR. The cardiac transcription network modulated by Gata4, Mef2a, Nkx2.5, Srf, histone modifications, and microRNAs. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van den Boogaard M, Wong LYE, Tessadori F, Bakker ML, Dreizehnter LK, Wakker V, Bezzina CR, t Hoen PAC, Bakkers J, Barnett P, Christoffels VM. Genetic variation in T-box binding element functionally affects SCN5A/SCN10A enhancer. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2519–2530. doi: 10.1172/JCI62613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spitz F, Furlong EEM. Transcription factors: from enhancer binding to developmental control. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:613–626. doi: 10.1038/nrg3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jolma A, Yan J, Whitington T, Toivonen J, Nitta KR, Rastas P, Morgunova E, Enge M, Taipale M, Wei G, Palin K, Vaquerizas JM, Vincentelli R, Luscombe NM, Hughes TR, Lemaire P, Ukkonen E, Kivioja T, Taipale J. DNA-Binding Specificities of Human Transcription Factors. Cell. 2013;152:327–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nutiu R, Friedman RC, Luo S, Khrebtukova I, Silva D, Li R, Zhang L, Schroth GP, Burge CB. Direct measurement of DNA affinity landscapes on a high-throughput sequencing instrument. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:659–664. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Levo M, Segal E. In pursuit of design principles of regulatory sequences. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:453–468. doi: 10.1038/nrg3684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu S-P, Cheng C-M, Lanz RB, Wang T, Respress JL, Ather S, Chen W, Tsai S-J, Wehrens XHT, Tsai M-J, Tsai SY. Atrial Identity Is Determined by a COUP-TFII Regulatory Network. Dev Cell. 2013;25:417–426. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thurman RE, Rynes E, Humbert R, et al. The accessible chromatin landscape of the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:75–82. doi: 10.1038/nature11232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sandelin A, Carninci P, Lenhard B, Ponjavic J, Hayashizaki Y, Hume DA. Mammalian RNA polymerase II core promoters: insights from genome-wide studies. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:424–436. doi: 10.1038/nrg2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.ENCODE Project Consortium. Consortium TEP. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shen Y, Yue F, Mccleary DF, Ye Z, Edsall L, Kuan S, Wagner U, Dixon J, Lee L, Lobanenkov VV, Ren B. A map of the cis-regulatory sequences in the mouse genome. Nature. 2012;488:116–120. doi: 10.1038/nature11243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Andersson R, Gebhard C, Miguel-Escalada I, et al. An atlas of active enhancers across human cell types and tissues. Nature. 2014;507:455–461. doi: 10.1038/nature12787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Buecker C, Wysocka J. Enhancers as information integration hubs in development: lessons from genomics. Trends Genet. 2012;28:276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wythe JD, Dang LTH, Devine WP, et al. ETS Factors Regulate Vegf-Dependent Arterial Specification. Dev Cell. 2013;26:45–58. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kathiriya IS, King IN, Murakami M, Nakagawa M, Astle JM, Gardner KA, Gerard RD, Olson EN, Srivastava D, Nakagawa O. Hairy-related transcription factors inhibit GATA-dependent cardiac gene expression through a signal-responsive mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54937–54943. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409879200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Blow MJ, McCulley DJ, Li Z, et al. ChIP-Seq identification of weakly conserved heart enhancers. Nat Genet. 2010;42:806–810. doi: 10.1038/ng.650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nord AS, Blow MJ, Attanasio C, Akiyama JA, Holt A, Hosseini R, Phouanenavong S, Plajzer-Frick I, Shoukry M, Afzal V, Rubenstein JLR, Rubin EM, Pennacchio LA, Visel A. Rapid and pervasive changes in genome-wide enhancer usage during mammalian development. Cell. 2013;155:1521–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]