Abstract

Cardiac Purkinje fibers, due to their unique anatomical location, cell structure and electrophysiologic characteristics, play an important role in cardiac conduction and arrhythmogenesis. Purkinje cell action potentials are longer than their ventricular counterpart, and display two levels of resting potential. Purkinje cells provide for rapid propagation of the cardiac impulse to ventricular cells and have pacemaker and triggered activity, which differs from ventricular cells. Additionally, a unique intracellular Ca2+ release coordination has been revealed recently for the normal Purkinje cell. However, since the isolation of single Purkinje cells is difficult, particularly in small animals, research using Purkinje cells has been restricted. This review concentrates on comparison of Purkinje and ventricular cells in the morphology of the action potential, ionic channel function and molecular determinants by summarizing our present day knowledge of Purkinje cells.

Keywords: Arrhythmias, Purkinje cells, Ion channels, Ca2+ waves, Ventricular cells

1. Introduction

Purkinje fibers play a major role in electrical conduction and propagation of impulse to the ventricular muscle. Many ventricular arrhythmias are initiated in the Purkinje fiber conduction system (eg. [1,2]) since they are susceptible to the development of early and delayed afterdepolarizations and show both normal and abnormal automaticity. Here we will review properties of Purkinje fibers and cells, and compare them to those of ventricles.

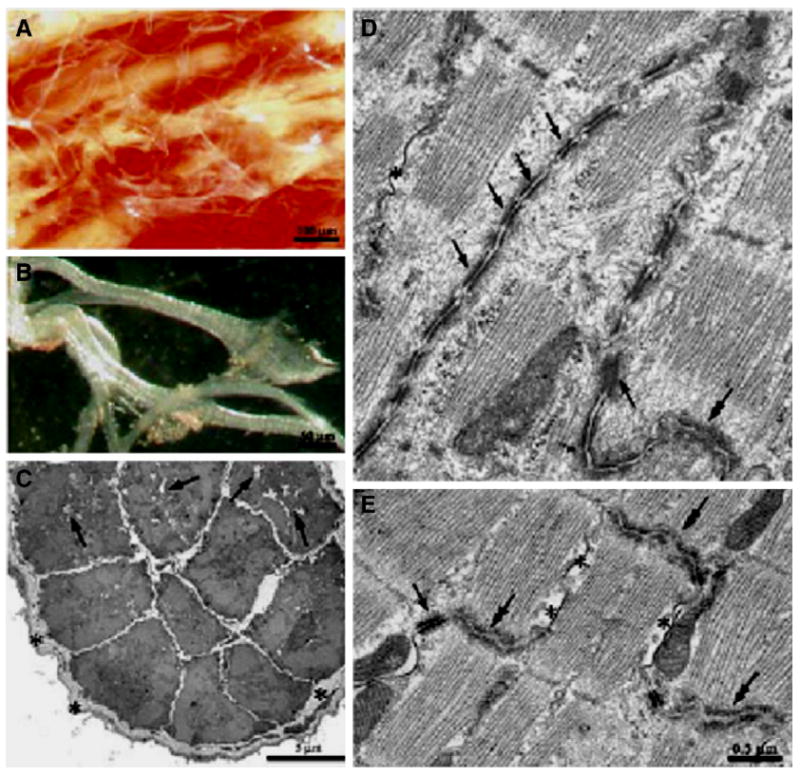

2. Connexin 4×

For Purkinje cells to provide for rapid propagation of the cardiac impulse, local circuit currents must be involved (for review see [3]). One of the factors affecting this propagation is the structure of the intercalated disk between 2 Purkinje cells (see Fig. 1 from [4]), which contains connexin(Cx) proteins. Purkinje cells, like specialized SA and AV nodal cells, reveal distinct compartmentalized Cx expression. However, unlike the compact node and transitional cells (two regions of the AV node where Cx45 predominates), and ventricular myocardium (where Cx43 predominates), the His bundle and Purkinje fibers express both Cx40 and Cx43 (see Table 1 [5]). Additional studies have shown that there is a unique subcellular distribution of Cx43 in bovine Purkinje fibers: Cx43 occupies the entire plasma membrane that faces other Purkinje cells but not the membrane that faces surrounding connective tissues [6]. The relative combination of Cx43 and Cx40 varies depending on part of His–Purkinje system studied. For instance, Cx43 is solely present in the proximal His bundle and branches but Cx40 and Cx43 are coexpressed in the distal bundle branches [7]. In human heart, transcript studies have shown that Cx40 is more strongly expressed in Purkinje fibers than right ventricular myocardium [8], which is consistent with the protein level studies. Obviously, Cx expression patterns will influence propagation between Purkinje and ventricular cells. In fact, recent studies suggest that Cx40 deficiency in mice is accompanied by right Bundle branch block presumably due to loss of Cx40 in Purkinje cells [9,10].

Table 1.

Relative expression levels of Cxs in human cardiac tissues (estimated expression levels are based on immunoconfocal microscopy)

| Cx isoform | SA node | Atrium | Compact AV node | His bundle | Bundle branch | Purkinje fiber | Ventricle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | − | ++++ | − | +++ | ++++ | ++++ | − |

| 43 | − | ++++ | − | ++ | +++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| 45 | +++ | + | +++ | ++ | + | + | ± |

Scale: ++++, very abundant; ±, barely detectable. From [5].

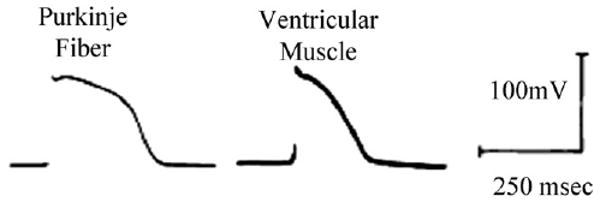

3. Action potentials

Purkinje cell action potentials (APs) are much longer than their ventricular counterpart (eg. see [11–13]). In rabbit, Purkinje cells exhibit a prominent phase 1 of repolarization, a more negative plateau, and a significantly longer APD90 than ventricular cells [14,15]. Similarly, in canine Purkinje fibers, APD50 and APD90 are prolonged (236±10.6 and 321±9.9 ms, respectively) compared to their ventricular counterparts (204±5.6, and 242±5.7 ms, respectively) (Fig. 2 from [16]) [11,17–19], yet there is no difference in resting potential (RP) between the two cell types. However, the total amplitude of the action potential (APA) and the maximal rate of rise of the action potential upstroke (Vmax) are much larger in Purkinje fibers (117±1.2 mV and 445±14.6 V/s, respectively) versus ventricle (106±1.1 ms and 230±9.5 V/s, respectively).

Women are more susceptible to the development of torsades de pointes, a rare life-threatening polymorphic ventricular tachycardia that may originate in Purkinje fibers. Gender differences in APs have been observed in canine Purkinje fibers [20] where APD40, APD50, APD70 and APD90 of Purkinje fibers are found to be significantly longer in female tissues (170.1±0.5, 204.9±9.5, 241.5±8.9 and 282.0±9.9 ms, respectively) compared to male tissues (134.8±13.1, 170.8±11.1, 210.3±9.8 and 246.5±9.8 ms, respectively). However, no differences of RP, APA and Vmax between male and female Purkinje cells were found. Similar findings have been reported for murine Purkinje cells [21]. While it is assumed that human Purkinje cell APDs are longer than their ventricular counterparts, no systematic study has yet been done to show this. Hence, intrinsically long APDs of normal non-remodeled Purkinje fibers (cells) set the stage for both mutation and drug-induced long QT syndromes [22].

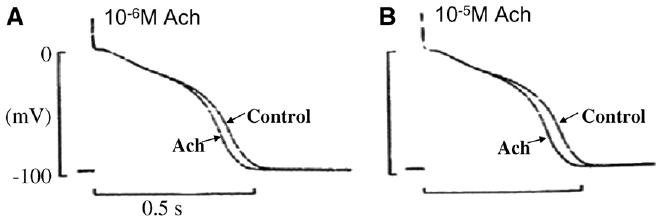

Compared to ventricle, IKAch appears to play an important role in Purkinje cell AP properties. Studies of the autonomic influence on the Purkinje fiber APD show that stimulation of muscarinic2 receptors reduces the APD independent of the spontaneous beating cycle length [23,24] (Fig. 3). This effect of acetylcholine (Ach) has been shown to be due to a production of a rate independent, background current that is linked to a GTP binding protein pathway. On the other hand, Ach has little or a small effect on APDs of ventricular endocardium but can either prolong (Ach 10−6 and 10−7 M) or shorten (10−5 M) APDs of ventricular epicardium [25,26]. However, the response of epicardial APD to Ach is dependent on Ito-mediated spike and dome morphology (a rate-dependence) and not directly due to IKAch activation. Thus, a difference in muscarinic modulation between Purkinje fiber and ventricular electrical activity is consistent with findings that Kir3.1, α-subunit of IKAch, abundance is greater in human Purkinje fibers than that in RV [8].

Fig. 3.

Effects of 10−6 M (Panel A) and 10−5 M (Panel B) acetylcholine (Ach) on action potentials of a canine Purkinje fiber in normal Tyrode's solution. The stimulation rate is 1 Hz. Note that APD is dose-dependently reduced by Ach. The upper ends of the 100 mV calibration bars indicate zero potential levels. From [24].

4. Resting potential

Inward rectifier K+ channels, IK1 (Kir2.1, Kir2.2 and Kir2.3), IKATP (Kir6.1 and Kir6.2) and IKAch (Kir3.1 and Kir3.4), conduct K+ currents more in the inward direction than the outward direction and play an important role in setting the RP close to the equilibrium potential for K+. While it has been known for a long time that Purkinje fibers display two levels of RP [27], this differs significantly from ventricular muscle. Purkinje cells have reasonably strong IK1 [28] but some characteristics (the nature of the negative slope) differ from ventricle(see [29]). Before full repolarization of AP, one or two early afterdepolarizations (EADs) were sometimes observed in the Purkinje cells with slightly more positive RP in normal [K+]o. However, the EADs were never observed when Purkinje cells were exposed to levcromakalim, a IKATP channel opener [14]. Ach significantly increases the RP in Purkinje fibers [24], but has no effect on RP of both epicardium and endocardium tissues [30]. A recent transcript study demonstrates that Kir2.1, Kir2.2, Kir6.1 and Kir6.2 abundance in human Purkinje fibers is about 50% less than that in right ventricle (RV) [8] however, Kir3.1 about 4000% more abundant than that in the RV (Table 2). Finally, there are at least four classes of two pore channels in cardiac cells: TASK, TWIK, TREK and THIK [31] and currents through these channels have been identified to contribute to resting voltages based on their little time- or voltage-dependence and I–V curves. Interestingly, the transcript abundance of TWIK1, TASK1 and TASK2 in the human Purkinje fibers is greater than that in the RV [8]. Perhaps these data help to explain the differences in the levels of RP between Purkinje and ventricular cells.

Table 2.

Comparison of voltage-gated K+ currents/channels between ventricle and Purkinje fibers

| Current | Ventricle | Purkinje fibers/cells | Species | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ito Blockers | ||||

| 4-AP | 511 μM(IC50) | 56 μM (IC50) | Canine, human | [44,45,49] |

| TEA | No effect | Strongly inhibiting | Human | [49] |

| H2O2 | No effect | Slow inactivation | Canine | [44] |

| Expression | ||||

| mRNA | Kv4.3 | Kv4.3 | Canine | [43] |

| Kv1.4 | Kv1.4 | Canine | [43] | |

| Kv3.4 | Kv3.4 ↑ | Canine | [43] | |

| KChIP2 | KChIP2 ↓ | Canine, human | [8,43] | |

| KChAP | KChaP ↑ | Human | [8] | |

| Protein | Kv4.3 | Kv4.3 ↓ | Canine | [43] |

| Kv3.4 | Kv3.4 ↑ | Canine | [43] | |

| Isus Blockers | ||||

| TEA | No effect | Strongly inhibiting | Human | [43] |

| IK1 Expression | ||||

| mRNA | Kir2.1 | Kir2.1 ↓ | Human | [8] |

| Kir2.2 | Kir2.2 ↓ | Human | [8] | |

| IK(ATP) | ||||

| ATP | 21 μM(IC50) | 119 μM(IC50) | Rabbit | [14,86] |

| Expression | ||||

| mRNA | Kir6.1 | Kir6.1 ↓ | Human | [8] |

| Kir6.2 | Kir6.2 ↓ | Human | [8] | |

| IK(ACh) Expression | ||||

| mRNA | Kir3.1 | Kir3.1 ↑ | Human | [8] |

| IKr Expression | ||||

| mRNA | ERG | ERG ↓ | Canine | [43] |

| Protein | ERG | ERG ↓ | Canine | [43] |

| IKs Expression | ||||

| mRNA | KCNQ1 | KCNQ1 ↓ | Canine | [43] |

| KCNE1 | KCNE1 ↑,↓ | Canine, Human | [8,43] | |

| Protein | KCNQ1 | KCNQ1 ↓ | Canine | [43] |

| KCNE1 | KCNE1 ↓ | Canine | [43] | |

| Others Expression | ||||

| mRNA | KCNE2 | KCNE2 ↑ | Canine, Human | [8,60] |

| Protein | KCNE2 | KCNE2 ↑ | Canine | [60] |

Expression is increased comparing to ventricle.

Expression is decreased comparing to ventricle.

5. Sodium currents

With a well polarized RP, a Purkinje cell displays a very rapid maximal upstroke velocity (Vmax) during phase 0 of the AP. The sodium current underlying this upstroke is referred to as the fast activating, inactivating sodium current (INa, thought to be due to the cardiac channel isoform Nav1.5). In addition, there is a prominent tetrodotoxin (TTX) sensitive or late Na+ current (INaL) in Purkinje fibers/cells (eg. [32]). Recently much has been written about the relative contribution of the various isoforms of the voltage gated Na+ channel protein to cell upstroke velocities and cardiac conduction (for review see [33]). Functionally, it has been recognized that APDs of ventricular and Purkinje cells are both sensitive to TTX suggesting the contribution of noncardiac TTX sensitive Na+ channels to depolarizing currents during the AP (eg. see [34]). While immunocytochemistry is not the most perfect method, studies have shown the presence of neuronal Na+ channel isoforms (Nav1.2, Nav1.3 and Nav1.6) in ventricular cells while Purkinje cells displayed only Nav1.1 and Nav1.2, both noncardiac isoforms. These latter authors go further to suggest that TTX sensitive Na+ channels contribute 22% to total peak INa of Purkinje cells [35] implicating a role of neuronal Na+ channel activity in the rapid upstroke velocities of Purkinje cell APs. Others have suggested that the skeletal muscle Na+ channel isoform, Nav1.4, possesses the functional requirements for INaL [13]. Finally, inferred from transcript abundance studies, one group suggests that Nav1.7 subunits underlie the enhanced TTX sensitivity of the human Purkinje cell [8]. Clearly, further work is needed here, for example, it would be important to know whether neuronal Na+ channel isoform mutations by altering Purkinje cell repolarization, are involved in some forms of long QT syndrome.

6. Calcium currents

The heart expresses several different voltage gated Ca2+ channels, each of which has been identified by its pore-forming α1 subunit. Most prominent is the high-voltage activated CaV1.2 (L-type) channel that contains α1C. However, the highly related CaV1.3 L-type channel (which contains the α1D subunit) is also expressed but is restricted to the sino-atrial tissues, AV node and Purkinje cells [36,37]. Despite the high degree of similarity between these α1 subunits, CaV1.3 Ca2+ channels display different biophysical properties compared to CaV1.2 channels, such as activating at more hyperpolarizing potentials and opening with faster activation kinetics [38]. Thus, a change in the balance of between CaV1.2 and CaV1.3 proteins could alter the properties of overall whole cell L-type Ca2+ currents, perhaps as observed in an early Purkinje cell study [39].

However, functionally, only two types of calcium currents have been described in canine Purkinje cells: L-type (ICaL) and T-type (ICaT) [39,40]. 100% of canine Purkinje cells had ICaT compared with 66.7% of ventricular cells, and the ratio of maximal T current to maximal L current in Purkinje cells was higher than the T/L ratio in ventricular cells [39]. The low-voltage activated T-type Ca2+ current has been found in other regions of the heart and because T-type Ca2+ channels activate at more hyperpolarizing potentials than the high-voltage activated Ca2+ channels, regulation of pacemaking has been a suspected role [41,42]. We are unaware of any reports of T-type calcium currents in human cardiac Purkinje fibers or cells. In our laboratory, we have been unable to record such currents in isolated human Purkinje cells.

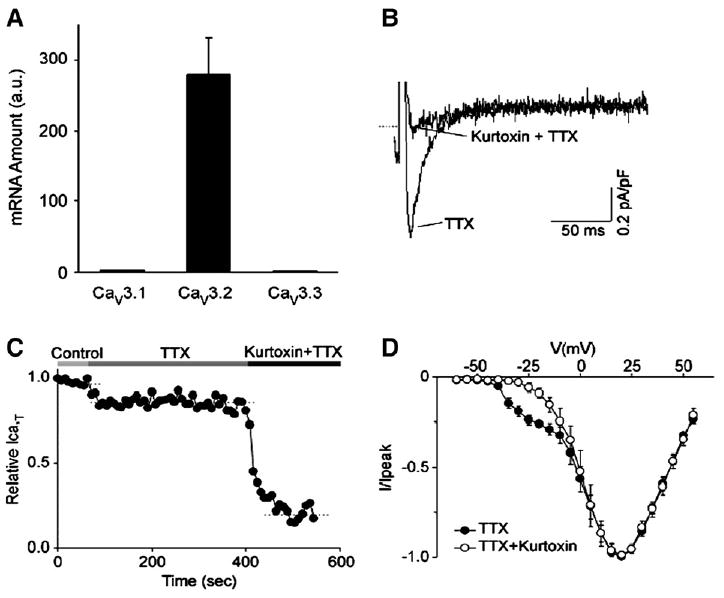

Therefore, in Purkinje cells, ICaT could play an important role in membrane electrical activity whereas in ventricular cells, ICaL is the main Ca2+ current. Recently, real-time PCR studies have verified the above functional results. All isoforms (Cav3.1, Cav3.2 and Cav3.3) of the T-type channel protein are more strongly expressed in canine Purkinje fibers than that in ventricular tissue from same hearts [43]. However Cav3.2 mRNA is expressed at the highest level in canine Purkinje fibers, and ICaT in Purkinje cells is completely suppressed by 200 nM kurtoxin, a specific blocker of both Cav3.1 and Cav3.2 channels [37] (Fig. 4). Therefore, the Cav3.2 gene appears to encode the bulk of the T-type Ca2+ channels in the canine Purkinje cell.

Fig. 4.

Panel A, a bar graph of relative mRNA abundance for the Cav3.1, Cav3.2 and Cav3.3 genes in canine Purkinje fibers. The mRNA quantities are determined by real-time PCR and are represented in arbitrary units. Note that the Cav3.2 gene is expressed at 100-fold more abundance than the Cav3.1 and Cav3.3 genes. Panel B, Kurtoxin selectively blocks the T-type component of the whole cell calcium current in canine Purkinje cells, consistent with Cav3.2 underlying this current. The current is elicited by a test pulse at − 25 mV from a holding potential of −90 mV, in control conditions and after the application of 200 nM kurtoxin, as indicated. Both control and drug recordings are performed in the presence of 20 μM TTX. Panel C, time course for the T-type calcium current inhibition by Kurtoxin. The horizontal bars on top of the graph indicate the bath solution applied. Panel D, average current–voltage plots obtained under control conditions and after application of Kurtoxin. The holding potential is −70 mV and test pulses are applied from −60 to +55 mV at 5 mV intervals. Modified from [37].

7. Transient outward potassium currents (Ito)

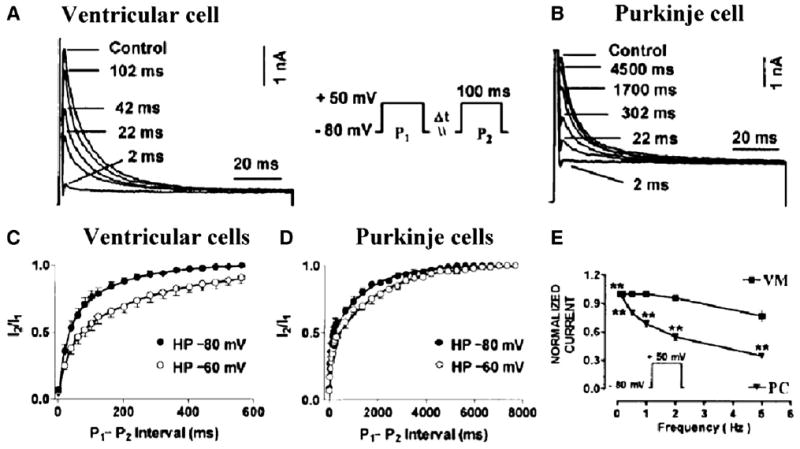

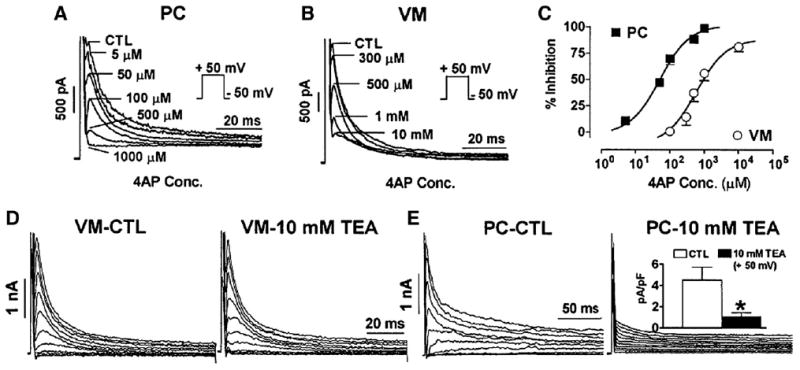

Several properties of the voltage dependent Ca2+ independent, transient outward current (Ito1) of Purkinje cells differ considerably from those of ventricular cells [44–46]. First, Ito currents in Purkinje cells recover from inactivation more slowly than their ventricular counterpart. For example, recovery from inactivation is almost complete within 100 ms in ventricular cells but requires >4 s (or 4 min [47]) in Purkinje cells (Fig. 5). Second, sustained outward currents only in Purkinje cells show a remarkable sensitivity to 4AP [44–46,48] and TEA [44,49] (Fig. 6). The molecular nature of Ito in canine Purkinje cells is reasonably clear and differs from that of ventricular cells. While Kv4.3 transcripts are the same in these two tissues [43], KChIP2 levels are lower in Purkinje fibers versus ventricle, consistent with protein findings (Table 2). KChIP2 coexpression with Kv4 substantially accelerates the recovery of Ito from inactivation [50]. Transcript studies of genes from nondiseased human tissues [8] confirm sparse KChIP2 transcript abundance yet reveal augmented KChaP and MirP1(KCNE2) transcripts in Purkinje tissues. Therefore, the sparse KChIP2 expression in Purkinje fibers likely contributes to the characteristic slow recovery from inactivation of Purkinje fiber Ito. Kv1.4, a K+ channel isoform that underlies Ito in some tissues, transcript is in small abundance in both ventricular and Purkinje tissues [43] suggesting little role in Purkinje cell electrophysiology. On the other hand, Kv3.4 is abundant at both the mRNA and protein level in Purkinje fibers and no so in ventricle [43]. Since the Kv3.4 subunit carries a TEA-sensitive Ito outward current [51], Kv3.4 current may be responsible for the large TEA-sensitive component of Ito in canine Purkinje cells (see the review [52]). Interestingly, there appear to be no differences in Kv3.4 transcript levels between Purkinje and ventricular human samples [8], suggesting that a K+ channel isoform plus its accessory protein may be involved in the augmented TEA sensitivity of the Purkinje voltage activated K currents.

Fig. 5.

Recovery of Ito from inactivation, as determined with paired 100 ms pulses (P1 and P2) delivered at 0.1 Hz from −80 to +50 mV with various P1–P2 intervals. Panel A and B, recording at P1–P2 intervals from a representative ventricular myocyte and a Purkinje cell, respectively. Panel C and D, ratios of current during P2 (I2) to current during P1 (I1) as a function of P1–P2 interval at HPs of −80 and −60 mV in canine ventricular and Purkinje cells, respectively. Best-fit biexponential functions are shown. Panel E, frequency dependence of Ito as determined by the ratio of the current during the 15th pulse to the current during the 1st pulse of a train of 100-ms pulses from −80 to +50 mV. Trains are separated by 60 s at the HP. VM: ventricular cells; PC: Purkinje cells. **P<0.01 versus ventricular cells. Note that Ito is more use dependent in Purkinje cells than ventricular cells. Modified from [44].

Fig. 6.

Recording of canine Purkinje cell (Panel A) and ventricular cell (Panel B) Ito on depolarization to +50 mV before (CTL) and during exposure to a series of 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) concentrations. Panel C, concentration–response curves for Ito inhibition by 4-AP, along with Hill equation fits. Panel D, Ito recording from a ventricular cell before and after exposure to 10 mM tetraethylammonium (TEA), respectively. E, Ito recording from a Purkinje cell before and after exposure to 10 mM TEA, respectively. Inset shows the Purkinje cell Ito density in absence and presence of 10 mM TEA. *P<0.05 versus control. PC: Purkinje cells; VM: Ventricular cells. Note a large TEA-sensitive outward current exists in Purkinje and not ventricular cells. Modified from [49].

Ito is composed of two portions, termed as Ito1, that is, the 4-AP-sensitive and voltage dependent current (see above) and Ito2. This latter current is sensitive to inhibition by stilbene disulfonates such as 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS) and is Ca2+ dependent chloride current (reviewed in [53]). I to2 has been implicated in delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs) in both ventricle and Purkinje fibers [54,55]. In sum, transient outward currents are prominent in Purkinje cells. Both transient and sustained outward currents contribute to Purkinje cell AP repolarization but most likely not directly to its prolonged APD.

8. IKr and IKs

Both IKr and IKs are smaller in Purkinje versus ventricular cells of the rabbit heart [56]. Compared to rabbit Purkinje cells, IKs tail currents are significantly larger in canine Purkinje cells [57], however, IKr tail current densities are comparable [46,58]. In canine Purkinje cells, reduced levels of IK1 and marked activation of IKr currents are consistent with a prominent role of this current in Purkinje cell AP repolarization [57,58]. Thus, IKs contributes little to total AP repolarization in canine Purkinje cells [18,57]. On the other hand, β-adrenergic stimulation increases IKs contribution to repolarization by increasing current amplitude, accelerating its activation, and shifting activation voltages toward the positive potential [59]. There have been no reports of IKs in human Purkinje cells (see [49]).

Molecular transcript data show that Herg (KCNH2) and KvLQT1 (KCNQ1) expression is lower in canine Purkinje fibers at both mRNA and protein levels (Table 2). Further, minK (KCNE1) transcripts are numerous in Purkinje fibers yet KCNE1 protein is significantly more strongly expressed in canine ventricle [43]. In human hearts, KCNE1 transcript levels are lower in Purkinje fibers than that in ventricle yet there are no data about protein levels [8]. Interestingly, mRNA and protein expression of MiRP1 (mink-related peptide 1, the product of the KCNE2 gene) is stronger in canine Purkinje fibers than in ventricle [60]. Considering that KCNQ1 is similar between Purkinje and ventricular cells, we suggest that a mixture of varying amounts of accessory proteins (eg. KCNE1 and KCNE2) could contribute to the phenotype of IKs in disease as well as normal hearts. For example, several have suggested that KCNQ1 can associate with KCNE1 for IKs or KCNE2 to produce large, constitutively active, voltage independent K+ currents [61–63].

9. NCX and NaK pump currents

Very few reports have examined closely the specific currents generated by the sodium calcium exchanger (NCX1) and the sodium–potassium pump in isolated Purkinje cells [43,64] (see review [65]). However a direct comparison between data form Purkinje fibers cannot be done with data from single Purkinje cells since very often other concerns apply. For example, older studies on Purkinje fibers (and ventricular cells for that matter) have stressed the role of ion accumulation in the clefts. Such accumulation would impact directly on transporters. Recent data suggest that transcript abundance of the NaK ATPase is reduced in Purkinje versus ventricular tissues [8] perhaps allowing for a Purkinje cell's greater sensitivity to agents that block this ATPase.

10. Pacemaker currents

The automaticity that occurs in isolated normal multicellular Purkinje fiber strands is an example of normal automaticity. A Purkinje fiber does not show automaticity when it is being overdriven by excitatory waves from the rapidly firing sinus node. This phenomenon is called overdrive suppression. We now know that this overdrive suppression results from enhanced electrogenic Na/K pump activity[66,67] and induced current which in turn results from the increased influx of sodium occurring from well polarized APs at the fast rate. Interestingly, while overdrive suppression is the common outcome in Purkinje fibers, post drive rate acceleration was described in early models of Purkinje pacemaker activity (eg. [68]). These models of automaticity were all enhanced using ouabain or some other form of digitalis suggesting that a role for intracellular Cai in initiation of nondriven electrical activity (see below).

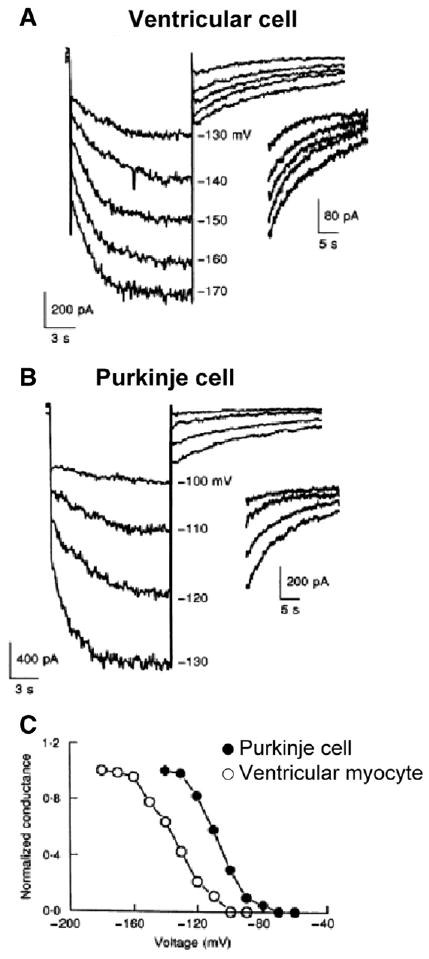

During this pacemaker activity, a Purkinje fiber's transmembrane action potential shows a slow diastolic depolarization during phase 4 preceding a nondriven action potential. Many have suggested that several types of ionic currents existing in the Purkinje myocyte play a role in generating phase 4 activity and thus underlie normal automaticity. These currents include, If, which by some is considered the main current [69]. In other studies using Purkinje fibers, the critical role of If for normal automaticity is less clear since lidoflazine, a drug which decreases If in sheep Purkinje fibers [70] has no effect on normal Purkinje fiber automaticity [71]. At first potassium currents were thought to deactivate (IK2 [72]) to give rise to a slow depolarization due to the presence of a persistent inward Na+ current in Purkinje cells. However, when outward currents are blocked, the If current is revealed and controls automaticity [69]. Recently another K+ current, IKdd, has been defined in Purkinje fibers and this outward current deactivates at more positive potentials than Purkinje If suggesting a role on pacemaking [73]. The nature of the persistently activated Na+ current that exists in this pacemaker potential range has been ascribed to TTX sensitive Na+ channels [34]. While the molecular nature of If has been ascribed to HCN4 and HCN2 proteins in Purkinje fibers [74], the molecular nature of the other currents remains unresolved. In whole cell patch clamp studies, steady-state If activation occurs in Purkinje cells at physiological potentials (−80 to −130 mV), whereas If activation occurs in ventricular cells at more negative potentials (−120 to −170 mV) [75] consistent with the activation curve of If for the ventricular cells being shifted ∼30 mV in the negative direction compared to Purkinje cells (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

The slow time-dependent inward currents were elicited upon hyperpolarization from a holding potential of −50 mV. Panel A: If current traces from a ventricular cell. Panel B: If current traces from a canine Purkinje cell. Panel C: Activation–voltage relation of If in the canine ventricular (○) and Purkinje (●) cells. Note that there is a significant positive shift (30 mV) of the activation curve of If in the Purkinje cell. Modified from [75].

Additional questions arise from single myocytes dispersed from Purkinje fiber bundles where it was found that the normally polarized (−85 mV) individual canine Purkinje myocyte is quiescent and lacks normal automaticity in the absence as well as in the presence of catecholamines [76] despite the fact that If has been identified in the Purkinje single cell [77]. We have shown that focally arising cell wide Ca2+ waves occur in normal Purkinje cells in the absence of electrical stimulation [78]. These Ca2+ waves appear to originate at cell borders similar to those in ventricular trabeculae can propagate the full extent of an aggregate, initiate membrane depolarization and/or nondriven electrical activity of the well polarized Purkinje aggregate. Importantly ryanodine and thapsigargin suppress the Ca2+ wave and accompanying membrane depolarization. Thus spontaneous Ca2+ release and ensuing Ca2+ waves modulate normal Purkinje cell pacemaker function. A similar role has been defined for Ca2+ waves in both SA nodal [79,80] and atrial pacemaker cells [81]. These are examples of reverse EC coupling [53]. Such a mechanism becomes critically important to ectopic pacemaker function of Purkinje cells that have survived in the infarcted heart [82–85].

In summary, we have known for many years about the existence of the specialized conducting fibers, Purkinje fibers, but until recently we knew little about what makes them so specialized. It is clear that their APD phenotype differs from the ventricular phenotype and this appears to be due to a unique composition of sarcolemmal ion channels. Combined with their unique method of EC coupling [53], the Purkinje fiber/cell should remain a serious in vitro model system for our understanding of arrhythmias, particularly those that are acquired, drug-induced or mutation based.

Fig. 1.

Panels A (low power), B (high power), Examples of Purkinje fiber strands from rat ventricle. Strands can be isolated from ventricular tissue and are generally surrounded by a thick layer of collagen. Panel C illustrates a Purkinje fiber strand that has been cut in cross section. Note collagen (asterisks) and empty cell areas filled with glycogen (arrows). Panel D illustrates very well the intercalated disk region between connecting Purkinje cells. Note the long finger like projections that form this connection. This differs substantially from the well-known staircase appearance of the disk region between two ventricular cells (Panel E). Modified from [4].

Fig. 2.

Fine tipped microelectrode recordings from a canine Purkinje fiber strand and ventricular muscle, paced at basic CL=500 ms and [K]o=4 mM. Note the marked differences in action potential duration (APD). Modified from [16].

Acknowledgments

Supported by grant HL58860 from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Bethesda, Maryland.

References

- 1.Weerasooriya R, Hsu LF, Scavee C, Sanders P, Hocini M, Cabera JA, et al. Catheter Ablation of ventricular fibrillation in structurally normal hearts targeting the RVOT and Purkinje ectopy. Herz. 2003;28:598–606. doi: 10.1007/s00059-003-2491-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopera G, Stevenson WG, Soejima K, Maisel WH, Koplan B, Sapp JL, et al. Identification and ablation of three types of ventricular tachycardia involving the His–Purkinje system in patients with heart disease. J Cardiovasc Electr. 2004;15:52–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2004.03189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleber AG, Rudy Y. Basic mechanisms of cardiac impulse propagation and associated arrhythmias. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:431–88. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Maio A, Ter Keurs HEDJ, Franzini-Armstrong C. T-tubular profiles in Purkinje fibres of mammalian myocardium. J Musc Res Cell Motil. 2007;28:115–21. doi: 10.1007/s10974-007-9109-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desplantez T, Dupont E, Severs N, Weingart R. Gap junction channels and cardiac impulse propagation. J Membr Biol. 2007;218:13–28. doi: 10.1007/s00232-007-9046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oosthoek PW, Viragh S, Lamers WH, Moorman JR. Immunohistochemical delineation of the conduction system. II The atrioventricular node and Purkinje system. Circ Res. 1993;73:482–91. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.3.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gourdie RG, Severs NJ, Green CR, Rothery S, Germroth P, Thompson RP. The spatial distribution and relative abundance of gap-junctional connexin40 and connexin43 correlate to functional properties of components of the cardiac atrioventricular conduction system. J Cell Sci. 1993;105:985–91. doi: 10.1242/jcs.105.4.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaborit N, Le Bouter S, Szuts V, Varro A, Escande D, Nattel S, et al. Regional and tissue specific transcript signatures of ion channel genes in the non-diseased human heart. J Physiol. 2007;582:675–93. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.126714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Rijen HVM, van Veen TAB, van Kempen MJA, Wilms-Schopman FJG, Potse M, Krueger O, et al. Impaired conduction in the bundle branches of mouse hearts lacking the gap junction protein connexin40. Circulation. 2001;103:1591–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.11.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu W, Saba S, Link MS, Bak E, Homoud MK, Estes NAM, III, et al. Atrioventricular nodal reverse facilitation in connexin40-deficient mice. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:1231–7. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tseng GN, Robinson RB, Hoffman BF. Passive properties and membrane currents of canine ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol. 1987;90:671–701. doi: 10.1085/jgp.90.5.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gintant GA, Datyner NB, Cohen IS. Slow inactivation of a tetrodotoxin-sensitive current in canine cardiac Purkinje fibers. Biophys J. 1984;45:509–12. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84187-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bocchi L, Vassalle M. Characterization of the slowly inactivating sodium current INa2 in canine cardiac single Purkinje cells. Exp Physiol. 2008;93:347–61. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.040881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Light PE, Cordeiro JM, French RJ. Identification and properties of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in myocytes from rabbit Purkinje fibres. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;44:356–69. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Persson F, Andersson B, Duker G, Jacobson I, Carlsson L. Functional effects of the late sodium current inhibition by AZD7009 and lidocaine in rabbit isolated atrial and ventricular tissue and Purkinje fibre. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;558:133–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaza A, Malfatto G, Rosen MR. Electrophysiologic effects of ketanserin on canine Purkinje fibers, ventricular myocardium and the intact heart. JPET. 1989;250:397–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robinson RB, Boyden PA, Hoffman BF, Hewett KW. Electrical restitution process in dispersed canine cardiac Purkinje and ventricular cells. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:H1018–25. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.5.H1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varro A, Balati B, Iost N, Takacs J, Virag L, Lathrop DA, et al. The role of the delayed rectifier component IKs in dog ventricular muscle and Purkinje fiber repolarization. J Physiol. 2000;523:67–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00067.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balati B, Iost N, Simon J, Varro A, Papp JG. Analysis of the electrophysiological effects of ambasilide, a new antiarrhythmic agent, in canine isolated ventricular muscle and Purkinje fibers. Gen Pharmacol. 2000;34:85–93. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(00)00048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.bi-Gerges N, Small BG, Lawrence CL, Hammond TG, Valentin JP, Pollard CE. Gender differences in the slow delayed (IKs) but not in inward (IK1) rectifier K+ currents of canine Purkinje fibre cardiac action potential: key roles for IKs, [beta]-adrenoceptor stimulation, pacing rate and gender. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;147:653–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anumonwo JMB, Tallini YN, Vetter FJ, Jalife J. Action potential characteristics and arrhythmogenic properties of the cardiac conduction system of the murine heart. Circ Res. 2001;89:329–35. doi: 10.1161/hh1601.095894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gintant GA, Limberis JT, McDermott JS, Wegner CD, Cox SF. The canine Purkinje fiber: an in vitro model system for acquired long QT syndrome and drug-induced arrhythmogenesis. J Cardiovasc Pharm. 2001;37:607–18. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200105000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malfatto G, Zaza A, Vanoli E, Schwartz PJ. Muscarinic effects on action potential duration and its rate dependence in canine Purkinje fibers. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1996;19:2023–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1996.tb03274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gadsby DC, Wit AL, Cranefield PF. The effects of acetylcholine on the electrical activity of canine cardiac Purkinje fibers. Circ Res. 1978;43:29–35. doi: 10.1161/01.res.43.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antzelevitch C, Litovsky SH, Lukas A. Epicardium versus endocardium: electrophysiology and pharmacology. In: Zipes DP, Jalife J, editors. Cardiac electrophysiology: from cell to bedside. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang ZK, Boyett MR, Janvier NC, McMorn SO, Shui Z, Karim F. Regional differences in the negative inotropic effect of acetylcholine within the canine ventricle. J Physiol. 1996;492:789–806. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gadsby DC, Cranefield PF. Two levels of resting potential in cardiac Purkinje fibers. J Gen Physiol. 1977;70:725–46. doi: 10.1085/jgp.70.6.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah A, Cohen IS, Datyner NB. Background K+ current in isolated canine cardiac Purkinje myocytes. Biophys J. 1987;52:519–25. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83241-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boyden PA, Albala A, Dresdner K. Electrophysiology and ultrastructure of canine subendocardial Purkinje cells isolated from control and 24 hour infarcted hearts. Circ Res. 1989;65:955–70. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.4.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Litovsky SH, Antzelevitch C. Differences in the electrophysiologic response of canine ventricular subendocardium and subepicardium to acetylcholine and isoproterenol: a direct effect of acetylcholine in ventricular myocardium. Circ Res. 1990;67:615–27. doi: 10.1161/01.res.67.3.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamargo J, Caballero R, Gomez R, Valenzuela C, Delpon E. Pharmacology of cardiac potassium channels. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;62:9–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gintant GA, Daytner NB, Cohen IS. Slow inactivation of a tetrodotoxin-sensitive current in canine cardiac purkinje fibers. Biophys J. 1984;45:509–12. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84187-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haufe V, Chamberland C, Dumaine R. The promiscuous nature of the cardiac sodium current. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:469–77. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Attwell D, Cohen I, Eisner DA, Ohba M, Ojeda C. The steady state TTX-sensitive (“window”) sodium current in cardiac Purkinje fibres. Pflugers Arch. 1979;379:137–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00586939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haufe V, Cordeiro JM, Zimmer T, Wu YS, Schiccitano S, Benndorf K, et al. Contribution of neuronal sodium channels to the cardiac fast sodium current INa is greater in dog heart Purkinje fibers than in ventricles. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:117–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qu Y, Baroudi G, Yue Y, El-Sherif N, Boutjdir M. Localization and modulation of alpha1D (Cav1.3) L-type Ca channel by protein kinase A. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2123–30. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01023.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosati B, Dun W, Boyden PA, McKinnon D. Molecular basis of the T and L type Ca2+ currents in canine Purkinje fibers. J Physiol. 2007;579:465–71. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.127480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helton TD, Xu W, Lipscombe D. Neuronal L-type calcium channels open quickly and are inhibited slowly. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10247–51. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1089-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tseng GN, Boyden PA. Multiple types of Ca currents in single canine Purkinje myocytes. Circ Res. 1989;65:1735–50. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.6.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hirano Y, Fozzard HA, January CT. Characteristics of L- and T-type Ca2+ currents in canine cardiac Purkinje cells. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:H1478–92. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.5.H1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hagiwara N, Irisawa H, Kameyama M. Contribution of two types of calcium currents to the pacemaker potentials of rabbit sino-atrial node cells. J Physiol. 1988;395:233–53. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp016916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mangoni M, Traboulsie A, Leoni AL, Couette B, Marger L, Quang KL, et al. Bradycardia and slowing of the atrioventricular conduction in mice lacking Cav3.1/alpha1G T type calcium channels. Circ Res. 2006;98:1422–30. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000225862.14314.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han W, Bao W, Wang Z, Nattel S. Comparison of ion channel subunit expression in canine cardiac Purkinje fibers and ventricular muscle. Circ Res. 2002;91:790–7. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000039534.18114.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han W, Wang Z, Nattel S. A Comparison of transient outward currents in canine cardiac Purkinje cells and ventricular myocytes. Amer J Physiol. 2000;279:H466–74. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.2.H466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jeck C, Pinto JMB, Boyden PA. Transient outward currents in subendocardial Purkinje myocytes surviving in the 24 and 48 hr infarcted heart. Circulation. 1995;92:465–73. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.3.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dumaine R, Cordeiro JM. Comparison of K+ currents in cardiac Purkinje cells isolated from rabbit and dog. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007 Feb;42:378–89. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boyett MR. A study of the effect of the rate of stimulation on the transient outward current in sheep cardiac Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 1981;319:1–22. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Bogaert PP, Snyders DJ. Effects of 4-aminopyridine on inward rectifying and pacemaker currents of cardiac Purkinje fibers. Pflugers Arch. 1982;394:230–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00589097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Han W, Zhang L, Schram G, Nattel S. Properties of potassium currents in Purkinje cells of failing human hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H2495–503. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00389.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.An WF, Bowlby MR, Betty M, Cao J, Ling H, Mendoza G, et al. Modulation of A type potassium channels by a family of calcium sensors. Nature. 2000;403:553–6. doi: 10.1038/35000592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vega-Saenz de Miera E, Morena H, Fruhling D, Kentros C, Rudy B. Cloning of ShIII (Shaw-like) cDNAs encoding a novel high-voltage-activating, TEA-sensitive, type-A K+ channel. Proc Biol Sci. 1992;248:9–18. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1992.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schram G, Pourrier M, Melnyk P, Nattel S. Differential distribution of cardiac ion channel expression as a basis for regional specialization in electrical function. Circ Res. 2002;90:939–50. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000018627.89528.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ter Keurs HEDJ, Boyden PA. Calcium and arrhythmogenesis. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:457–506. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Volders PG, Vos MA, Szabo B, Sipido KR, de Groot SH, Gorgels AP, et al. Progress in the understanding of cardiac early afterdepolarizations and torsades de pointes: time to revise current concepts. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;46:376–92. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Verkerk AO, Veldkamp MW, Bouman LN, Van Ginneken ACG. Calcium-activated Cl-current contributes to delayed afterdepolarizations in single purkinje and ventricular myocytes. Circ. 2000;101:2639–44. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.22.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cordeiro JM, Spitzer KW, Giles W. Repolarizing K+ currents in rabbit heart Purkinje cells. J Physiol. 2000;508:811–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.811bp.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Han W, Chartier D, Li D, Nattel S. Ionic remodeling of cardiac Purkinje cells by congestive heart failure. Circulation. 2001;104:2095–100. doi: 10.1161/hc4201.097134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gintant G. Characterization and functional consequence of delayed rectifier current transient in ventricular repolarization. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:H806–17. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.3.H806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Han W, Wang Z, Nattel S. Slow delayed rectifier current and repolarization in canine cardiac purkinje cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H1075–80. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.3.H1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pourrier M, Zicha S, Ehrlich J, Han W, Nattel S. Canine ventricular KCNE2 expression resides predominantly in Purkinje fibers. Circ Res. 2003;93:189–91. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000084851.60947.B5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bendahhou S, Marionneau C, Haurogne K, Larroque MM, Derand R, Szuts V, et al. In vitro molecular interactions and distribution of KCNE family with KCNQ1 in the human heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67:529–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lundquist AL, Manderfield LJ, Vanoye CG, Rogers CS, Donahue BS, Chang PA, et al. Expression of multiple KCNE genes in human heart may enable variable modulation of IKs. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:277–87. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu DM, Jiang M, Zhang M, Liu XS, Korolkova YV, Tseng GN. KCNE2 is colocalized with KCNQ1 and KCNE1 in cardiac myocytes and may function as a negative modulator of IKs current amplitude in the heart. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:1469–80. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boyden PA, Dresdner KP., Jr Electrogenic Na(+)-K+ pump in Purkinje myocytes isolated from control noninfarcted and infarcted hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1990;258:H766–72. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.3.H766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Glitsch HG. Electrophysiology of the sodium–potassium–ATPase in cardiac cells. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1791–826. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.4.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Valenzuela F, Vassalle M. Interaction between overdrive excitation and overdrive suppression in canine Purkinje fibres. Cardiovasc Res. 1983;17:608–19. doi: 10.1093/cvr/17.10.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kline RP, Kupersmith J. Effects of extracellular potassium accumulation and sodium pump activation on automatic canine Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 1982;324:507–33. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wittenberg SM. Acceleration of ventricular pacemakers by transient increases in heart rate in dogs during ouabain administration. Circ Res. 1970;26:705–16. doi: 10.1161/01.res.26.6.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.DiFrancesco D. A new interpretation of the pace-maker current in calf Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 1981;314:359–76. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hart G, Dukes ID. An analysis of the rate dependent action of lidoflazine in mammalian sinoatrial node and Purkinje fibers. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1984;16:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(84)80712-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dangman KH, Miura DS. Does I-f control normal automatic rate in canine cardiac Purkinje fibers? Studies on the negative chronotropic effects of lidoflazine. J Cardiovasc Pharm. 1987;10:332–40. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198709000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Noble D, Tsien RW. The kinetics and rectifier properties of the slow potassium current in cardiac Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 1968;195:185–214. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vassalle M, Yu H, Cohen IS. The pacemaker current in cardiac Purkinje myocytes. J Gen Physiol. 1995;106:559–78. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.3.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shi W, Wymore R, Yu H, Wu J, Wymore RT, Pan Z, et al. Distribution and prevalence of hyperpolarization-activated cation channel (HCN) mRNA expression in cardiac tissues. Circ Res. 1999;85:e1–6. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.1.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yu H, Chang F, Cohen IS. Pacemaker current i(f) in adult canine cardiac ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1995;485:469–83. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Robinson RB, Boyden PA, Hoffman BF, Hewett KW. The electrical restitution process in dispersed canine cardiac Purkinje and ventricular cells. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:H1018–25. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.5.H1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Callewaert G, Carmeliet EE, Vereecke J. Single cardiac Purkinje cells: general electrophysiology and voltage-clamp analysis of the pace-maker current. J Physiol. 1984;349:643–61. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Boyden PA, Pu J, Pinto JMB, Ter Keurs HEDJ. Ca2+ transients and Ca2+ waves in Purkinje cells Role in action potential initiation. Circ Res. 2000;86:448–55. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.4.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lakatta EG, Maltsev VA, Bogdanov KY, Stern MD, Vinogradova TM. Cyclic variation of intracellular calcium A critical factor for cardiac pacemaker cell dominance. Circ Res. 2003;92:e45–50. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000055920.64384.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li J, Qu J, Nathan RD. Ionic basis of ryanodine's negative chronotropic effect on pacemaker cells isolated from the sinoatrial node. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H2481–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.5.H2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Huser J, Blatter LA, Lipsius S. Intracellular Ca2+ release contributes to automaticity in cat atrial pacemaker cells. J Physiol. 2000;542:415–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Boyden PA, Dun W, Barbhaiya C, Ter Keurs HEDJ. 2APB- and JTV519 (K201) sensitive micro Ca2+ waves in arrhythmogenic Purkinje cells that survive in infarcted canine heart Heart Rhythm. 2004;1:218–26. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Boyden PA, Barbhaiya C, Lee T, Ter Keurs HEDJ. Nonuniform Ca2+ transients in arrhythmogenic Purkinje cells that survive in the infarcted canine heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:681–93. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00725-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hirose M, Stuyvers BD, Dun W, Ter Keurs HEDJ, Boyden PA. Wide long lasting perinuclear Ca2+ release events generated by an interaction between ryanodine and IP3 receptors in canine Purkinje cell. JMCC. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.05.008. online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hirose M, Stuyvers BD, Dun W, Ter Keurs HEDJ, Boyden PA. Increased spontaneous Ca2+ release in saponin-treated Purkinje cells that survive in the infarcted heart. Biophysical J. 2006;90:222a. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Light PE, Allen BG, Walsh MP, French RJ. Regulation of adenosine triphosphate sensitive potassium channels from rabbit ventricular myocytes by protein kinase C and type 2A protein phosphatases. Biochem. 1995;34:7252–7. doi: 10.1021/bi00021a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]