Abstract

G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs) are the most targeted group of proteins for the development of therapeutic drugs. Until the last decade, structural information about this family of membrane proteins was relatively scarce, and their mechanisms of ligand binding and signal transduction were modeled on the assumption that GPCRs existed and functioned as monomeric entities. New crystal structures of native and engineered GPCRs, together with important biochemical and biophysical data that reveal structural details of the activation mechanism(s) of this receptor family, provide a valuable framework to improve dynamic molecular models of GPCRs with the ultimate goal of elucidating their allostery and functional selectivity. Since the dynamic movements of single GPCR protomers are likely to be affected by the presence of neighboring interacting subunits, oligomeric arrangements should be taken into account to improve the predictive ability of computer-assisted structural models of GPCRs for effective use in drug design.

Keywords: GPCRs, molecular modeling, dynamics, activation, dimerization, oligomerization

Introduction

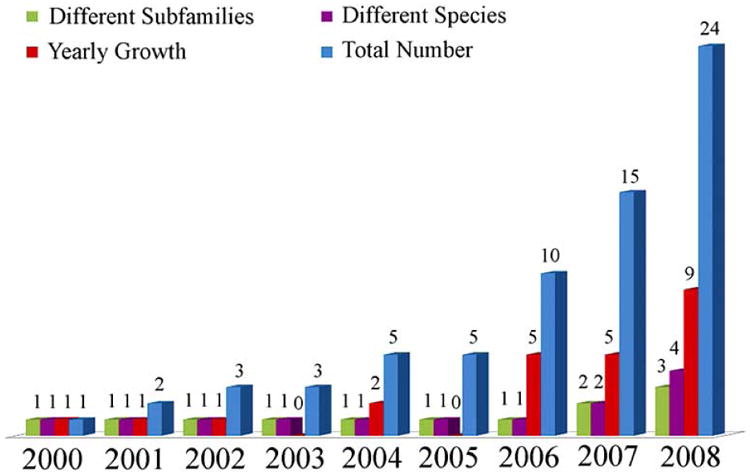

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) represent the largest cell surface receptor superfamily, and the largest class of drug targets with about 50% of the existing drugs currently targeting these receptors for their therapeutic action [1]. Recent detailed structural information has remarkably improved our understanding of the GPCR receptor family. Nevertheless, production of new GPCR crystal structures has proceeded at an extremely slow pace since publication in year 2000 of the first crystal structure of prototypic class A GPCR bovine rhodopsin [2] (see reported yearly growth of available GPCR crystal structures in Fig. (1)). Additional crystal structures of bovine rhodopsin in inactive and early photoactivated states were published from 2000 to 2008 [2-12], with the first crystal structures of a non-rhodopsin class A GPCR, i.e. β2 adrenergic receptor in complex with Fab [13] or fused with T4 lysozyme [14,15], becoming available at the end of 2007. These crystal structures were followed by other rhodopsin/opsin and non-rhodopsin class A GPCR crystal structures, including those of native squid rhodopsin [16,17], a thermally stabilized human β2-adrenergic receptor [18], a β1 adrenergic receptor mutant [19], ligand-free native bovine opsin [20,21], and an engineered adenosine A2A receptor [22]. To date, there are twenty-four crystal structures of class A GPCRs (twenty-two with an intact transmembrane (TM) region) that have been obtained by X-ray crystallography. These crystal structures correspond to Protein Data Bank (PDB) [23] identification codes 1F88, 1HZX, 1L9H, 1U19, 1GZM, 2J4Y, 2PED, 2G87, 2HPY, 2I35, 2I36, 2I37, 2R4R, 2R4S, 2RH1, 3C9L, 3C9M, 2ZIY, 2Z73, 3D4S, 2VT4, 3CAP, 3DQB, and 3EML.

Fig. (1).

Current statistics on the growth of class A GPCR crystal structures since the first publication of bovine rhodopsin crystal structure in year 2000. Total number of crystal structures per year, yearly growth of crystal structures, total number of different species of known structure, and total number of GPCR subfamilies of known structure are shown in blue, red, purple, and green colors, respectively.

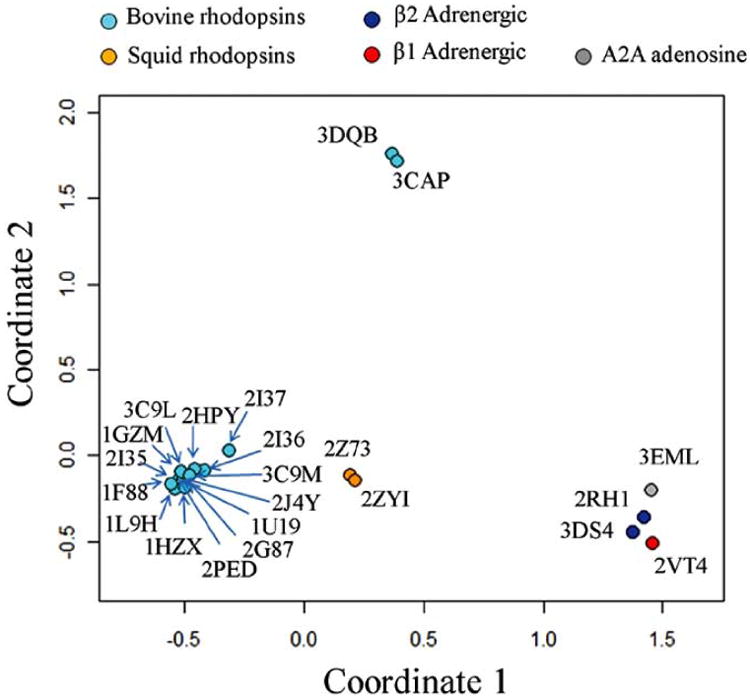

Although the number of available class A GPCR crystal structures has considerably increased as compared to a few years ago, these structures represent only four different species (Homo sapiens, Bos taurus, Todarodes pacificus, and Meleagris gallopavo; purple columns in Fig. (1)) and just three different subfamilies of GPCRs (rhodopsin/opsin, adrenoceptor, and adenosine subfamilies; green columns in Fig. (1)). Thus, the available data constitute a highly redundant set. More importantly, the structural differences between the TM regions of all available GPCR crystal structures appear to be relatively small, albeit sufficient to separate them in different groups. Fig. (2) shows a multidimensional scaling analysis in a two-dimensional Euclidean space of the differences between the TM regions of pairs of the twenty-two available class A GPCR crystal structures with an intact TM region. Each crystal structure is represented by a point in a two-dimensional space. The points are arranged in this space so that distances between pairs of points represent the degree of structural differences among corresponding pairs of GPCR crystal structures. Specifically, GPCR structures with small differences in their TM regions (as measured by backbone root mean square deviation (RMSD)) are represented by points that are close in the two-dimensional space, whereas those with structurally dissimilar TM regions are represented by points that are farther apart. As expected, all available crystal structures of bovine rhodopsin (cyan points in Fig. (2)) form a cluster, with the exception of Palczewski's photoactivated crystal structure of bovine rhodopsin identified by PDB code 2I37 [11], which is spaced a little bit apart. Adrenergic (red points for β1 and blue points for β2 in Fig. (2)) and adenosine A2A (grey point in Fig. (2)) receptors also form a cluster, though less compact than that of rhodopsin. The two structures of squid rhodopsin (orange points in Fig. (2)) are placed between bovine rhodopsins and non-rhodopsin GPCRs, although closer to bovine rhodopsins. It is clear from the plot in Fig. (2) that the class A GPCR crystal structures exhibiting the largest conformational differences from either inactive rhodopsins or inactive non-rhodopsin GPCRs are those corresponding to ligand-free native bovine opsin with and without a co-crystallized peptide derived from the carboxy terminus of the Gα-subunit (PDB codes 3DQB and 3CAP, respectively) [20, 21]. Incidentally, these conformations have been suggested to encompass some of the structural features (e.g., relatively large outward tilt of TM6 and small motion of TM7) that are usually attributed to active states of GPCRs.

Fig. (2).

Multidimensional scaling analysis in a two-dimensional Euclidean space of structural differences (as measured by backbone RMSD) between the TM regions of pairs of the twenty-two available class A GPCR crystal structures with an intact TM region (PDB codes: 1F88, 1HZX, 1L9H, 1U19, 1GZM, 2J4Y, 2PED, 2G87, 2HPY, 2I35, 2I36, 2I37, 2RH1, 3C9L, 3C9M, 2ZIY, 2Z73, 3D4S, 2VT4, 3CAP, 3DQB, and 3EML). Coordinates 1 and 2 correspond to the new coordinate system of the dataset after reduction to a two-dimensional space. GPCR crystal structures with structurally similar TM regions are represented by points that are at short Euclidean distance, whereas GPCR crystal structures with dissimilar TM regions are represented by points that are far apart. Available crystal structures of bovine rhodopsin/opsin, squid rhodopsin, β1 adrenergic, β2 adrenergic, and A2A adenosine receptors are represented as cyan, orange, red, blue, and grey points, respectively. Chain A of the corresponding PDB files was always used for the structural analysis, with the only exception of β1-adrenergic receptor for which chain B was used.

The new crystallographic information on GPCRs has recently been enriched by important new biochemical and biophysical data revealing the details of possible conformational changes of the receptors upon activation (e.g., see [24-26]) as well as their putative oligomeric arrangements [27]. Among them, particularly interesting are Hubbell's recent results of time-resolved electron-paramagnetic resonance studies [24], which suggest a temporal sequence of events in rhodopsin activation, starting with the internal Schiff base proton transfer followed by the TM6 movement, a proton uptake from solution, and final receptor binding to transducin. More recently, the same group has used double electron-electron resonance spectroscopy to determine distances and activation-induced distance changes between pairs of nitroxide side chains introduced in helices at the cytoplasmic surface of rhodopsin [26]. These results point to a 5 Å outward movement of TM6 and smaller movements of TM1, TM7, and the C-terminal sequence following helix H8, in a supposedly activated form of rhodopsin. Although these distance changes are less pronounced than the very large rigid body movements that were originally described for rhodopsin based on data from site-directed spin labeling [28], they still constitute significant structural rearrangements, which may impact the predictive ability of molecular models of the receptor. As a matter of fact, even small variations in the individual TM helices between the recently available carazolol-bound β2-adrenergic crystal structures and rhodopsin-based models of this receptor have been shown to affect the ability of the ligand to bind in a correct orientation in homology-based models using rigid- protein flexible-ligand virtual docking approaches [29]. Moreover, it remains to be elucidated whether the dynamics associated with ligand-induced activation of a GPCR are also affected by receptor dimerization/oligomerization. This is an important required clarification in view of the large number of recent studies supporting a functional role for dimerization/oligomerization of GPCRs (for a recent review see [30]), despite some evidence still sustaining predominant functional GPCR monomers [31-34]. Notably, we have recently shown that the dynamic movements of an unliganded inactive rhodopsin protomer are clearly affected by oligomerization, using inferences from an elastic network model [35].

In aggregate, the new structural and dynamic information currently available on GPCRs provides a valuable framework to improve dynamic molecular models of these receptors with the ultimate goal of elucidating their allostery and functional selectivity for use in rational drug design. In this review, we will discuss progress in obtaining enhanced information-driven computational models of GPCRs in either inactive or active conformations. Inferences from these new generation GPCR models are expected to improve current understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying receptor function, thus helping to develop molecular tools that modulate receptor function.

Impact of New GPCR Crystal Structures on Modeling of GPCRS

Modeling Transmembrane Regions

Recent elucidation of several high-resolution crystallographic structures of family A GPCRs has shed new light on ligand binding to GPCRs and on GPCR activation. Comparison between five representative inactive (inverse agonist-bound) crystal structures of class A GPCRs that are currently available in the literature (i.e. native bovine rhodopsin 1U19, engineered human β2 adrenergic receptor 2RH1, mutant turkey β1 adrenergic receptor 2VT4, engineered human A2A adenosine receptor 3EML, and native squid rhodopsin 2Z73) shows clear differences among these receptors at both the TM and loop level. These structural differences were recently analyzed by comparing two receptors at the time [36, 37]. We recently overlapped the TM regions of all five available representative inactive structures of GPCRs [81], and pro-vided quantitative estimates of differences at the extra-cellular side compared to the intracellular side. By calculating RMSD values of the outer membrane segments of each TM helix separately from their inner membrane sides, we observed that TM1, TM2, TM3 and TM4 of the five available representative inactive crystal structures of GPCRs diverge more in their outer membrane side than in their inner membrane side. In contrast, TM5, TM6 and TM7 exhibited a greater RMSD in their inner membrane sides for most structures. Differences were also recorded at the binding site of the five available representative inactive crystal structures of GPCRs (see the “Predicting Modes of Ligand Binding” section for details), making investigators question the performance of GPCR homology models based on templates with low sequence identity with the receptor target. In general, reliable models (e.g., with Cα RMSD values to the native structure of 2 Å or less) of finely aligned TM regions of membrane proteins may be obtained for template sequence identities of 30% or higher. Based on this consideration, we recently investigated the extent to which current crystal structures of GPCRs are valuable templates for homology modeling of the TM region of human Class A GPCRs [81], and concluded that only a reduced number of these receptors (<25%) can find an accurate template in any of the available GPCR crystal structures. For the majority of human Class A GPCRs for which the sequence identity with any of the available templates is less than 30%, multiple template modeling may offer an alternative strategy to build overall improved three-dimensional (3D) models of GPCRs, though of limited use at this stage [81].

Modeling Loops

The recently available non-rhodopsin class A GPCR crystal structures [13-15, 18, 19, 22] have revealed significant conformational variability in the long loop regions compared to rhodopsin, especially in the case of intracellular (IC) loop IC2 and extracellular (EC) loop EC2. This observation did not come as a complete surprise for three main reasons: 1) loop regions in GPCRs exhibit low sequence identity and variable length due to insertions and deletions; 2) long loops are highly flexible; and 3) loop conformations may strongly depend on crystal packing and crystallization conditions (e.g., interactions with fused proteins). As a result, homology modeling based on the loops of bovine rhodopsin/opsin, squid rhodopsin, human adenosine A2A, turkey β1 or human β2 adrenergic receptors is not feasible for most GPCRs. Thus, we have recently tested the ability of fairly reliable and fast ab initio loop prediction algorithms that are currently available for globular proteins to predict the conformations of long loops of GPCRs, and found that the Rosetta prediction algorithm [38] performs better than others in the identification of low-energy/low RMSD loop conformations from available crystallographic minima of GPCRs (unpublished results). Whether or not these low energy conformations would remain preferred low-energy conformations in the interaction of GPCRs with cellular proteins at their cytoplasmic side (e.g., G-proteins, β-arrestin) will need to be verified both experimentally and computationally.

Modeling Activated States

All currently available GPCR crystal structures refer to inactive receptor forms. A possible reason for the lack of crystal structures of active agonist-bound states of GPCRs resides in their higher conformational flexibility, and thus intrinsic instability, as compared to inactive inverse agonist-bound states [39]. In fact, agonist binding to GPCRs is likely to produce a succession of different conformations [40], triggering G-protein binding to the cytoplasmic side of the receptor. Notably, more and more recent evidence supports the notion that different ligands stabilize different receptor conformations [40], which may be responsible for GPCR functional selectivity. Recently, the thermostability of several GPCRs, including the antagonist-bound turkey β1 adrenergic receptor [19], and both the antagonist- and agonist-bound states of human adenosine A2A receptor [41] was improved by point mutations. While the recently published generic strategy for the isolation of detergent-solubilized thermostable mutants provided the means to obtain diffracting crystals of the antagonist-bound turkey β1 adrenergic receptor mutant [42], no crystal structures of the agonist-bound state of human adenosine A2A receptor are available yet. Notably, ten of the twenty-seven mutations that stabilized the agonist-binding conformation of human adenosine A2A receptor are present at the cytoplasmic side of the receptor, either in the third intracellular loop or at the end of TM6.

In the absence of crystal structures of active GPCR forms, there has recently been a research focus on computational prediction of activated 3D models of GPCRs. We have recently reviewed the methods and results of most of these studies elsewhere [43]. To the best of our knowledge, however, no novel predictions derived from recent activated GPCR models have been validated experimentally yet. It would be interesting to know which of these previous models, if any, contain the structural features that were highlighted by the most recent biophysical [24-26] and structural [20, 21] studies. For instance, the structural similarity between these GPCR activated models and the crystal structures of either the isolated native bovine opsin [20] or the complex between opsin and the C-terminal peptide derived from the α-subunit of the G-protein transducin [21] should be assessed. Although the possibility cannot be ruled out that currently available opsin structures represent more stable conformations of opsin that have passed the stage of regenerability [36], these structures contain some of the structural features that have often been attributed to active states of GPCRs [44]. In fact, they show a relatively large tilt of TM6 and a smaller motion of TM7 at the cytoplasmic side of the receptor, which seem to open a cleft for G-protein binding, in agreement with both earlier and recent spectroscopic studies [28, 45]. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that these opsin structures may provide a new framework for building and assessing putative models of dynamic transformation from inactive to active GPCR forms for a more effective use in rational drug design. Studies along these lines are currently ongoing in our laboratory.

Predicting Modes of Ligand-Binding

The newly available inverse agonist-bound crystal structures of adrenoceptors reveal that ligands mostly occupy similar locations in their respective GPCR, with an overlap of substantial regions. For instance, the β2-adrenergic ligand carazolol and the rhodopsin ligand retinal show a substantial overlap of their non-aromatic regions. However, the β-ionone ring of retinal extends deep into the binding pocket of rhodopsin and contacts residues of TM5 and TM6, including the highly conserved W6.48 (Ballesteros & Weinstein's generic numbering [46]), a residue whose rotamer change produces the so-called “toggle switch” for receptor activation [25, 47-49]. Carazolol does not contact directly W6.48, but it interacts with an extended aromatic network surrounding this residue, which includes residues F6.51 and F6.52. Notably, the slight differences between the binding pockets of β2-adrenergic and rhodopsin crystal structures influence the performance of automatic docking algorithms to the extent that the use of the β2 adrenergic receptor crystallographic structure is largely preferred to rhodopsin-based models of the receptor to predict reliable ligand binding poses, and to explore the potential for discovery of novel chemical classes acting at this receptor [29, 50, 51]. Subtle yet relevant differences were also observed between the carazolol and timolol binding modes in the crystal structures of human β2-adrenergic receptor [13, 15] and its cholesterol-bound thermostable structure [18], respectively. Specifically, the thiadiazole ring of timolol binds deeper into the receptor pocket, and two additional polar interactions are formed.

While available β2 adrenergic receptor crystal structures [13, 15, 18] were determined in the presence of carazolol or timolol in their ligand-binding pockets, the available crystal structure of β1 adrenergic receptor [19] contains cyanopindolol, a ligand that is structurally similar to carazolol. Accordingly, the binding of cyanopindolol to β1 adrenergic receptor was similar to that of carazolol in human β2 adrenergic receptor with the same side chains from TM3, TM5, TM6, TM7, and EL2 contributing to ligand binding. However, carazolol extended more deeply into the binding site of the human β2 adrenergic receptor due to an interaction between the extra ring in the carazolol heterocyclic ring and Y5.38 of the receptor. While the first-shell ligand-receptor interactions are mostly similar, analysis of receptor residues within 8 Å of the binding pockets of β1 and β2 adrenergic receptors allowed to identify two residues (4.56 and 7.35) that are different between the two receptor subtypes, and may therefore be responsible for ligand selectivity. In addition to these residues, there are also significant differences in the amino acid sequence around the entrance to the ligand-binding pocket, which could also affect ligand binding.

In contrast to the β-adrenergic ligands and retinal, the ligand crystallized in the binding site of the recently available human adenosine A2A receptor, ZM241385, occupies a significantly different position in the TM bundle, with the ligand being almost perpendicular to the membrane plane. These differences in the position and orientation of the A2A adenosine ligand binding pocket compared to those of β-adrenergic ligands and retinal seems to suggest that there is no general GPCR family-conserved receptor binding pocket in which selectivity is achieved only through different amino acid side chains. In the majority of previous molecular modeling studies, the ligand binding site of retinal and/or β-adrenergic ligands was used as the starting point for predictions on the A2A adenosine receptor. This may have been the reason for the failure of some computational studies to predict exactly the same binding pocket of A2A adenosine receptor as resulting from crystallographic studies. To address this issue, we are currently attempting classification of the binding pockets of the different human class A GPCRs in terms of sequence and structural similarity, with the ultimate goal of improving current understanding of ligand selectivity to GPCRs for use in drug discovery.

Construction of Dimerization/Oligomerization Interfaces

Despite the explosion of recent interest in GPCR oligomers as attractive potential new drug targets, our understanding of the structural details of GPCR oligomers is still very limited, affecting their complete and efficient exploitation. Among the important questions that remain to be answered is whether or not different GPCRs exhibit different dimerization/oligomerization interfaces. The various evolutionary-based bioinformatics approaches (recently reviewed in [43, 52]) that have been used to predict possible dimerization/oligomerization interfaces of GPCRs did not predict exactly the same interfaces for all the subfamilies studied, although some TM segments (e.g., TM4) were predicted more often than others as likely interfaces [52]. Although the possibility cannot be ruled out that dimerization/oligomerization interfaces of GPCRs are subtype-specific, the success rate of these computational tools in predicting likely interfaces of GPCR oligomers may also depend on the statistical significance of the dataset used for calculations, i.e. the number of sequences available for each subfamily of GPCRs. Moreover, solvent accessibility calculations using the atomic coordinates of the rhodopsin crystal structure to prune the outputs of sequence-based methods may have added an additional level of uncertainty. In fact, the structural differences between rhodopsin and non-rhodopsin GPCR crystal structures, which are evident from the analysis of the recent GPCR crystal structures, are likely to affect local exposure of some of the residues to the environment, thus creating some inaccurate estimates of solvent accessibility values assigned to equivalent positions in different receptors.

In our opinion, to produce more accurate GPCR oligomeric models to successfully guide new experiments, greater integrated efforts by the experimental and computational communities are needed. Along these lines, in collaboration with experimental laboratories, we have recently contributed to the computational structural prediction of several GPCR oligomeric arrangements, including dopamine D2 homo-oligomers [27, 53], and the newly discovered serotonin 2A/metabotropic glutamate receptor 2 complex [54]. Notably, the recent high-resolution structure of the β2 adrenergic receptor [15], which has much greater sequence similarity with the dopamine D2 receptor and a much straighter TM1 compared to rhodopsin, allowed us to build a 3D model of the dopamine D2 homo-oligomer with a packed TM1 interface that satisfied cross-linking data [27]. The same packing was not possible in a rhodopsin-based model of the dopamine D2 homo-oligomer, as the kink in the interacting TM1 helices would interfere with such a configuration. This packing also differed from the model based on inferences from AFM of native rhodopsin [55, 56], as well as from other symmetric TM1 interfaces that have been observed in crystal structures [11, 20, 21]. Although our TM1 interface is closer to that of metarhodopsin I from electron cryo-microscopy [11], the specific residues at the interface differ.

Given the importance of a detailed structural context of GPCR oligomers to facilitate the design and interpretation of current physiological and pharmacological experiments, our recent contribution to the field also includes storing and distributing this information to the scientific community via an information management system called GPCR-Oligomerization Knowledge Base (GPCR-OKB), whose ontology we recently published in the literature [57] in collaboration with several experimental leaders in the field of GPCR oligomerization. Having recently started data entry, curation and internal testing of GPCR-OKB, we anticipate the release of a comprehensive prototype of the system in the near future, so that end-users of this database will soon be able to test it and provide feedback.

Dynamics of GPCR Oligomers

The development of increasingly accurate dynamic 3D models of GPCR oligomers, refined on the basis of ever more detailed structural information from experiments, is anticipated to produce a more complete structural context for understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying GPCR function, possibly yielding successful drug discovery. Unlike the static – yet highly accurate - structural descriptions obtained from experimental techniques such as X-ray crystallography, computational simulations of 3D models of GPCRs can provide a valid characterization of the dynamic properties of GPCR function. Computational approaches using either standard molecular dynamics simulations or coarse-grained models have recently contributed to the understanding of the dynamic behavior of GPCRs in either monomeric [58-69], dimeric [35, 70], or oligomeric [35, 71] arrangements. In a recent review [43], we summarized the approaches used in most of those studies, and the results deriving from them. Analysis of these results aided in the efforts to decipher the complex allosterism that propagates through GPCRs from the extracellular to the intracellular side of the cell membrane. However, a complete picture of the conformational changes associated to ligand-induced activation of a GPCR in an oligomeric arrangement and interacting with G-proteins is still lacking. In case no drastic approximations are used, this is a rather complex task for the following main reasons: 1) the size of the system is very large, easily reaching several hundreds of thousand particles; 2) the time scale accessible to standard molecular dynamics simulations on such large systems is typically less than 100 ns compared to average experimental time scales of seconds; 3) one should simulate several events to understand the thermodynamics of dimerization/oligomerization of GPCRs, and thus be able to obtain estimates that can be compared to experiments; 4) it is unclear whether protomers of GPCR oligomers are activated independently or cooperatively by agonists, and whether one activated protomer is sufficient to activate the G-protein, so several different models should be studied.

To overcome these problems, and provide a more complete description of the allosteric mechanisms regulating GPCR functional selectivity to concurrently help in drug discovery, one should probably consider using coarse-grained models of the GPCR oligomeric machinery, as well as enhanced sampling algorithms. We are currently exploring these possibilities in our laboratory to eventually study the energetics and dynamics of GPCR oligomers interacting with G-proteins in an explicit lipid-bilayer environment. The recent availability in the literature of new structural and dynamic data on the prototypic GPCR rhodopsin/opsin from biophysical studies [20, 21, 24-26] may help to build reliable starting coarse-grained models of the GPCR oligomer-G protein complexes, and to test the accuracy of the dynamic information obtained from these approximate – yet powerful – models and simulations.

Disruption of Dimerization/Oligomerization Interfaces

An understanding at the structural and dynamic level of the nature of the interaction between GPCR protomers is expected to help elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying GPCR cellular function, with the promise of discovering novel improved therapeutics targeting the GPCR oligomeric structures and their exclusive mechanisms. One possibility that might be worth exploring is to develop molecular tools (e.g., peptides or small molecules) that would disrupt specific dimerization interfaces of GPCRs, thereby either impairing cross-talk between GPCR subunits, or promoting specific signaling events.

To date, in the absence of a clear understanding of the key interactions between GPCR protomers, there have been a limited number of studies attempting to disrupt GPCR dimerization/oligomerization. Some of the experimental strategies that have been used to disrupt GPCR oligomers (e.g., employing peptides corresponding to specific transmembrane domains or “knocking down” specific receptor subunits using a small interfering RNA-based strategy) have recently been reviewed in the literature [30]. However, the conclusions from these studies are all but definitive in terms of unraveling the specific dimerization-disrupting residues at the interface between GPCR protomers.

To the best of our knowledge, we are among the first investigators who have contributed to the design of an adhoc computational method for the prediction of mutations that can stabilize or destabilize a GPCR dimer/oligomer while maintaining the monomer's native fold. We tested the efficacy of this new method using the dimer of the single-spanned transmembrane domain of glycophorin A, and comparing experimental data from mutagenesis of the helix-helix interface with computational predictions at that interface. We then developed a flexible template for a rhodopsin homodimer with a symmetric interface involving TM4 and TM5, and used this template to predict sets of three and five dimerization-disrupting mutations. The reason for selecting sets of three and five mutations is that single point mutations may be insufficient to prevent dimerization. Although interesting, these predictions remain to be tested experimentally.

Design of Dimer/Oligomer Specific Drugs

The discovery of clinically relevant GPCR dimers/oligomers (mostly heteromers), including the serotonin 2A-metabotropic glutamate receptor 2 complex (schizophrenia?) [54], κ-δ opioid receptor complex (tissue-specific agonist for pain) [72], κ opioid receptor-chemokine CXC4 receptor complex (pain?) [73], angiotensin AT1-bradikynin B2 receptor complex (pre-eclampsia hypertension) [74], cannabinoid CB1-adenosine A2A receptor complex (Parkinson's disease?) [75], gonadotropin GnRH-GnRH receptor complex (hypogonadotropic hypogonadism) [76], prostaglandin EP1-β2 adrenergic receptor complex (asthma?) [77], and γ-aminobutyric acid GABAB1-GABAB2 receptor complex (GABAB receptor agonist Baclofen is an antispasm) [78] suggests that GPCR complexes may provide a distinct group of targets for novel drug design (for recent reviews, see [30, 79]). The observation that several GPCR heterodimers may exhibit altered pharmacological responses has generated a great deal of excitement about the opportunity to discover heterodimer-selective ligands as new GPCR drugs. One of them is the selective agonist 6′-guanidinonaltrindole (6′-GNTI) at δ opioid-κ opioid receptor heterodimers, which has been shown to exhibit an in vivo action as a spinally selective analgesic [72]. It is not clear, however, how 6′-GNTI might bind selectively to the δ opioid-κ opioid receptor heterodimers, nor are the conformational changes that this ligand would induce in the receptor complex. A similar uncertainty exists for the so-called bivalent ligands (for a recent review, see [80]), i.e. a series of compounds in which two distinct pharmacophores are connected by a linker segment of varying length. These ligands have been suggested to specifically target GPCR dimers/oligomers, but again their mode of binding is unknown. More integrated efforts by the computational and experimental communities are needed to develop molecular models of GPCR oligomers bound to these types of compounds. Inferences from molecular dynamics simulations of these systems compared to canonical ligand-receptor monomer interactions are expected to advance our understanding of the mechanisms underlying selectivity towards heterodimeric assemblies of GPCRs.

Summary

The discussion above highlights the central role that recent structural insights from new diffracting crystals of native and engineered GPCRs are currently playing, together with recent biophysical and biochemical data, in the development of enhanced computer-assisted dynamic molecular models of GPCR oligomers. This new generation of GPCR models is expected to improve current understanding of receptor allostery and functional selectivity for its effective use in rational drug discovery.

Acknowledgments

Our work on structural and dynamics aspects of GPCR dimerization/oligomerization is supported by NIH grants DA017976, DA020032, and DA026434 (to MF) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. AB was supported by American-Italian Cancer Foundation Post-Doctoral Research Fellowship: 2008-2009.

Abbreviations

- GPCRs

G-protein coupled receptors

- TM

Transmembrane

- RMSD

Root mean square deviation

- IC2

Intracellular loop 2

- EC2

Extracellular loop 2

- GPCR-OKB

GPCR-Oligomerization Knowledge Base

References

References 82-84 are related articles recently published.

- 1.Overington JP, Al-Lazikani B, Hopkins AL. How many drug targets are there? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:993–6. doi: 10.1038/nrd2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palczewski K, Kumasaka T, Hori T, Behnke CA, Motoshima H, Fox BA, et al. Crystal structure of rhodopsin: A G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2000;289:739–45. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li J, Edwards PC, Burghammer M, Villa C, Schertler GF. Structure of bovine rhodopsin in a trigonal crystal form. J Mol Biol. 2004;343:1409–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teller DC, Okada T, Behnke CA, Palczewski K, Stenkamp RE. Advances in determination of a high-resolution three-dimensional structure of rhodopsin, a model of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) Biochemistry. 2001;40:7761–72. doi: 10.1021/bi0155091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okada T, Fujiyoshi Y, Silow M, Navarro J, Landau EM, Shichida Y. Functional role of internal water molecules in rhodopsin revealed by X-ray crystallography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5982–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082666399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okada T, Sugihara M, Bondar AN, Elstner M, Entel P, Buss V. The retinal conformation and its environment in rhodopsin in light of a new 2.2 A crystal structure. J Mol Biol. 2004;342:571–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Standfuss J, Xie G, Edwards PC, Burghammer M, Oprian DD, Schertler GF. Crystal structure of a thermally stable rhodopsin mutant. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:1179–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakamichi H, Buss V, Okada T. Photoisomerization mechanism of rhodopsin and 9-cis-rhodopsin revealed by x-ray crystallography. Biophys J. 2007;92:L106–8. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.108225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakamichi H, Okada T. Crystallographic analysis of primary visual photochemistry. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:4270–3. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamichi H, Okada T. Local peptide movement in the photoreaction intermediate of rhodopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12729–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601765103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salom D, Lodowski DT, Stenkamp RE, Le Trong I, Golczak M, Jastrzebska B, et al. Crystal structure of a photoactivated deprotonated intermediate of rhodopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16123–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608022103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stenkamp RE. Alternative models for two crystal structures of bovine rhodopsin. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2008;D64:902–4. doi: 10.1107/S0907444908017162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rasmussen SG, Choi HJ, Rosenbaum DM, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Edwards PC, et al. Crystal structure of the human beta2 adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. 2007;450:383–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenbaum DM, Cherezov V, Hanson MA, Rasmussen SG, Thian FS, Kobilka TS, et al. GPCR engineering yields high-resolution structural insights into beta2-adrenergic receptor function. Science. 2007;318:1266–73. doi: 10.1126/science.1150609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cherezov V, Rosenbaum DM, Hanson MA, Rasmussen SG, Thian FS, Kobilka TS, et al. High-resolution crystal structure of an engineered human beta2-adrenergic G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2007;318:1258–65. doi: 10.1126/science.1150577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimamura T, Hiraki K, Takahashi N, Hori T, Ago H, Masuda K, et al. Crystal structure of squid rhodopsin with intracellularly extended cytoplasmic region. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17753–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800040200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murakami M, Kouyama T. Crystal structure of squid rhodopsin. Nature. 2008;453:363–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanson MA, Cherezov V, Griffith MT, Roth CB, Jaakola VP, Chien EY, et al. A specific cholesterol binding site is established by the 2.8 A structure of the human beta2-adrenergic receptor. Structure. 2008;16:897–905. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warne T, Serrano-Vega MJ, Baker JG, Moukhametzianov R, Edwards PC, Henderson R, et al. Structure of a beta1-adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. 2008;454:486–91. doi: 10.1038/nature07101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park JH, Scheerer P, Hofmann KP, Choe HW, Ernst OP. Crystal structure of the ligand-free G-protein-coupled receptor opsin. Nature. 2008;454:183–7. doi: 10.1038/nature07063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scheerer P, Park JH, Hildebrand PW, Kim YJ, Krauss N, Choe HW, et al. Crystal structure of opsin in its G-protein-interacting conformation. Nature. 2008;455:497–502. doi: 10.1038/nature07330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaakola VP, Griffith MT, Hanson MA, Cherezov V, Chien EY, Lane JR, et al. The 2.6 Angstrom Crystal Structure of a Human A2A Adenosine Receptor Bound to an Antagonist. Science. 2008;322:1211–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1164772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–42. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knierim B, Hofmann KP, Ernst OP, Hubbell WL. Sequence of late molecular events in the activation of rhodopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20290–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710393104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crocker E, Eilers M, Ahuja S, Hornak V, Hirshfeld A, Sheves M, et al. Location of Trp265 in metarhodopsin II: implications for the activation mechanism of the visual receptor rhodopsin. J Mol Biol. 2006;357:163–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altenbach C, Kusnetzow AK, Ernst OP, Hofmann KP, Hubbell WL. High-resolution distance mapping in rhodopsin reveals the pattern of helix movement due to activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7439–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802515105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo W, Urizar E, Kralikova M, Mobarec JC, Shi L, Filizola M, et al. Dopamine D2 receptors form higher order oligomers at physiological expression levels. EMBO J. 2008;27:2293–304. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hubbell WL, Altenbach C, Hubbell CM, Khorana HG. Rhodopsin structure, dynamics, and activation: a perspective from crystallography, site-directed spin labeling, sulfhydryl reactivity, and disulfide cross-linking. Adv Protein Chem. 2003;63:243–90. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(03)63010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Costanzi S. On the applicability of GPCR homology models to computer-aided drug discovery: a comparison between in silico and crystal structures of the beta2-adrenergic receptor. J Med Chem. 2008;51:2907–14. doi: 10.1021/jm800044k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Milligan G. A day in the life of a G protein-coupled receptor: the contribution to function of G protein-coupled receptor dimerization. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl 1):S216–29. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whorton MR, Bokoch MP, Rasmussen SG, Huang B, Zare RN, Kobilka B, et al. A monomeric G protein-coupled receptor isolated in a high-density lipoprotein particle efficiently activates its G protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7682–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611448104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bayburt TH, Leitz AJ, Xie G, Oprian DD, Sligar SG. Transducin activation by nanoscale lipid bilayers containing one and two rhodopsins. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14875–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701433200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.James JR, Oliveira MI, Carmo AM, Iaboni A, Davis SJ. A rigorous experimental framework for detecting protein oligomerization using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer. Nat Methods. 2006;3:1001–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyer BH, Segura JM, Martinez KL, Hovius R, George N, Johnsson K, et al. FRET imaging reveals that functional neurokinin-1 receptors are monomeric and reside in membrane microdomains of live cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2138–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507686103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niv MY, Filizola M. Influence of oligomerization on the dynamics of G-protein coupled receptors as assessed by normal mode analysis. Proteins. 2008;71:575–86. doi: 10.1002/prot.21787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mustafi D, Palczewski K. Topology of class a g protein-coupled receptors: insights gained from crystal structures of rhodopsins, adrenergic and adenosine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:1–12. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.051938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hanson MA, Stevens RC. Discovery of new GPCR biology: one receptor structure at a time. Structure. 2009;17:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang C, Bradley P, Baker D. Protein-protein docking with backbone flexibility. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:503–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gether U, Ballesteros JA, Seifert R, Sanders-Bush E, Weinstein H, Kobilka BK. Structural instability of a constitutively active G protein-coupled receptor. Agonist-independent activation due to conformational flexibility. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2587–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobilka BK, Deupi X. Conformational complexity of G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:397–406. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Magnani F, Shibata Y, Serrano-Vega MJ, Tate CG. Co-evolving stability and conformational homogeneity of the human adenosine A2a receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10744–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804396105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Serrano-Vega MJ, Magnani F, Shibata Y, Tate CG. Conformational thermostabilization of the beta1-adrenergic receptor in a detergent-resistant form. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:877–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711253105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mobarec JC, Filizola M. Advances in the Development and Application of Computational Methodologies for Structural Modeling of G-Protein Coupled Receptors. Exp Opin on Drug Disc. 2008;3:343–355. doi: 10.1517/17460441.3.3.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwartz TW, Hubbell WL. Structural biology: A moving story of receptors. Nature. 2008;455:473–4. doi: 10.1038/455473a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kusnetzow AK, Altenbach C, Hubbell WL. Conformational states and dynamics of rhodopsin in micelles and bilayers. Biochemistry. 2006;45:5538–50. doi: 10.1021/bi060101v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ballesteros JA, Weinstein H. Integrated methods for the construction of three-dimensional models and computational probing of structure-function relations in G protein coupled receptors. Meth Neurosci. 1995;25:366–428. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schwartz TW, Frimurer TM, Holst B, Rosenkilde MM, Elling CE. Molecular mechanism of 7TM receptor activation--a global toggle switch model. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;46:481–519. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shi L, Liapakis G, Xu R, Guarnieri F, Ballesteros JA, Javitch JA. Beta2 adrenergic receptor activation. Modulation of the proline kink in transmembrane 6 by a rotamer toggle switch. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40989–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206801200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ballesteros JA, Jensen AD, Liapakis G, Rasmussen SG, Shi L, Gether U, et al. Activation of the beta 2-adrenergic receptor involves disruption of an ionic lock between the cytoplasmic ends of transmembrane segments 3 and 6. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29171–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103747200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sabio M, Jones K, Topiol S. Use of the X-ray structure of the beta2-adrenergic receptor for drug discovery. Part 2: Identification of active compounds. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:5391–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Topiol S, Sabio M. Use of the X-ray structure of the Beta2-adrenergic receptor for drug discovery. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:1598–602. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Filizola M, Weinstein H. The study of G-protein coupled receptor oligomerization with computational modeling and bioinformatics. Febs J. 2005;272:2926–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guo W, Shi L, Filizola M, Weinstein H, Javitch JA. Crosstalk in G protein-coupled receptors: changes at the transmembrane homodimer interface determine activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17495–500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508950102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gonzalez-Maeso J, Ang RL, Yuen T, Chan P, Weisstaub NV, Lopez-Gimenez JF, et al. Identification of a serotonin/glutamate receptor complex implicated in psychosis. Nature. 2008;452:93–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fotiadis D, Liang Y, Filipek S, Saperstein DA, Engel A, Palczewski K. The G protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin in the native membrane. FEBS Lett. 2004;564:281–8. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00194-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liang Y, Fotiadis D, Maeda T, Maeda A, Modzelewska A, Filipek S, et al. Rhodopsin signaling and organization in heterozygote rhodopsin knockout mice. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48189–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408362200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Skrabanek L, Murcia M, Bouvier M, Devi L, George SR, Lohse MJ, et al. Requirements and ontology for a G protein-coupled receptor oligomerization knowledge base. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:177. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gouldson PR, Kidley NJ, Bywater RP, Psaroudakis G, Brooks HD, Diaz C, et al. Toward the active conformations of rhodopsin and the beta2-adrenergic receptor. Proteins. 2004;56:67–84. doi: 10.1002/prot.20108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Niv MY, Skrabanek L, Filizola M, Weinstein H. Modeling activated states of GPCRs: the rhodopsin template. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2006;20:437–48. doi: 10.1007/s10822-006-9061-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Isin B, Rader AJ, Dhiman HK, Klein-Seetharaman J, Bahar I. Predisposition of the dark state of rhodopsin to functional changes in structure. Proteins. 2006;65:970–83. doi: 10.1002/prot.21158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nikiforovich GV, Marshall GR. Modeling flexible loops in the dark-adapted and activated states of rhodopsin, a prototypical G-protein-coupled receptor. Biophys J. 2005;89:3780–9. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.070722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fanelli F, Dell'Orco D. Rhodopsin activation follows precoupling with transducin: inferences from computational analysis. Biochemistry. 2005;44:14695–700. doi: 10.1021/bi051537y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saam J, Tajkhorshid E, Hayashi S, Schulten K. Molecular dynamics investigation of primary photoinduced events in the activation of rhodopsin. Biophys J. 2002;83:3097–112. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75314-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kong Y, Karplus M. The signaling pathway of rhodopsin. Structure. 2007;15:611–23. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huber T, Botelho AV, Beyer K, Brown MF. Membrane model for the G-protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin: hydrophobic interface and dynamical structure. Biophys J. 2004;86:2078–100. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74268-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grossfield A, Feller SE, Pitman MC. Convergence of molecular dynamics simulations of membrane proteins. Proteins. 2007;67:31–40. doi: 10.1002/prot.21308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Faraldo-Gomez JD, Forrest LR, Baaden M, Bond PJ, Domene C, Patargias G, et al. Conformational sampling and dynamics of membrane proteins from 10-nanosecond computer simulations. Proteins. 2004;57:783–91. doi: 10.1002/prot.20257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Crozier PS, Stevens MJ, Forrest LR, Woolf TB. Molecular dynamics simulation of dark-adapted rhodopsin in an explicit membrane bilayer: coupling between local retinal and larger scale conformational change. J Mol Biol. 2003;333:493–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cordomi A, Perez JJ. Molecular dynamics simulations of rhodopsin in different one-component lipid bilayers. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:7052–63. doi: 10.1021/jp0707788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Filizola M, Wang SX, Weinstein H. Dynamic models of G-protein coupled receptor dimers: indications of asymmetry in the rhodopsin dimer from molecular dynamics simulations in a POPC bilayer. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2006;20:405–16. doi: 10.1007/s10822-006-9053-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Periole X, Huber T, Marrink SJ, Sakmar TP. G protein-coupled receptors self-assemble in dynamics simulations of model bilayers. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:10126–32. doi: 10.1021/ja0706246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Waldhoer M, Fong J, Jones RM, Lunzer MM, Sharma SK, Kostenis E, et al. A heterodimer-selective agonist shows in vivo relevance of G protein-coupled receptor dimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9050–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501112102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Finley MJ, Chen X, Bardi G, Davey P, Geller EB, Zhang L, et al. Bi-directional heterologous desensitization between the major HIV-1 co-receptor CXCR4 and the kappa-opioid receptor. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;197:114–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.AbdAlla S, Lother H, el Massiery A, Quitterer U. Increased AT(1) receptor heterodimers in preeclampsia mediate enhanced angiotensin II responsiveness. Nat Med. 2001;7:1003–9. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Carriba P, Ortiz O, Patkar K, Justinova Z, Stroik J, Themann A, et al. Striatal adenosine A2A and cannabinoid CB1 receptors form functional heteromeric complexes that mediate the motor effects of cannabinoids. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:2249–59. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leanos-Miranda A, Ulloa-Aguirre A, Janovick JA, Conn PM. In vitro coexpression and pharmacological rescue of mutant gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors causing hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in humans expressing compound heterozygous alleles. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:3001–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McGraw DW, Mihlbachler KA, Schwarb MR, Rahman FF, Small KM, Almoosa KF, et al. Airway smooth muscle prostaglandin-EP1 receptors directly modulate beta2-adrenergic receptors within a unique heterodimeric complex. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1400–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI25840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brauner-Osborne H, Wellendorph P, Jensen AA. Structure, pharmacology and therapeutic prospects of family C G-protein coupled receptors. Curr Drug Targets. 2007;8:169–84. doi: 10.2174/138945007779315614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Panetta R, Greenwood MT. Physiological relevance of GPCR oligomerization and its impact on drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:1059–66. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Berque-Bestel I, Lezoualc'h F, Jockers R. Bivalent ligands as specific pharmacological tools for g protein-coupled receptor dimers. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2008;5:312–8. doi: 10.2174/157016308786733591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mobarec JC, Sanchez R, Filizola M. Modern homology modeling of G protein coupled receptors: which structural template to use? J Med Chem. 2009;52(16):5207–5216. doi: 10.1021/jm9005252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Deane R, Sagare A, Zlokovic BV. The role of the cell surface LRP and soluble LRP in blood-brain barrier Abeta clearance in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14(16):1601–5. doi: 10.2174/138161208784705487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu Z, Zhang J, Zhang A. Design of multivalent ligand targeting G-protein-coupled receptors. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15(6):682–718. doi: 10.2174/138161209787315639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ono K, Hirohata M, Yamada M. Alpha-synuclein assembly as a therapeutic target of Parkinson's disease and related disorders. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14(30):3247–66. doi: 10.2174/138161208786404191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]