Abstract

Neurotensin (NT) is an endogenous neuropeptide involved in a variety of central and peripheral neuromodulatory effects. Here we show effects of site-specific glycosylation on the in vitro and in vivo pharmacological properties of this neuropeptide. NT analogs containing O-linked disaccharides (β-melibiose and α-TF antigen) or β-lactose unit linked via a PEG3-spacer were designed and chemically synthesized using Fmoc chemistry. For the latter analog, Fmoc-Glu-(β-Lac-PEG3-amide) was prepared. Our results indicate that the addition of the disaccharides did not negatively affect the subnanomolar affinity nor the low nanomolar agonist potency for the neurotensin receptor subtype 1 (NTS1). Interestingly, three glycosylated analogs exhibited subpicomolar potency in the 6 Hz limbic seizure mouse model of pharmacoresistant epilepsy following intracerebroventricular administration. Our results suggest for the first time that chemically-modified NT analogs may lead to novel antiepileptic therapies.

Keywords: neurotensin, anticonvulsant, glycosylation, binding, agonist

Introduction

Neurotensin (NT) is a tridecapeptide, ZLYENKPRRPYIL (Z is pyroglutamate), involved in a variety of central and peripheral neuromodulatory effects.[1–4] NT and its analogs exhibit potent antinociceptive activity[5, 6] and may also play a major role in the pathophysiology of several brain diseases.[7] As recently reviewed by Boules et al,[8] metabolically-stable NT analogs that penetrate the blood-brain-barrier (BBB) could be used as effective therapeutics for the treatment of pain, schizophrenia, or other neurological and psychiatric diseases. Various approaches have been undertaken to improve bioavailability and pharmacological properties of NT, including truncations,[9] cyclization,[10–12] backbone modification,[13–15] substitution of individual amino acids with nonnatural residues,[16, 17] and mimetics.[18] The efforts from several research groups, including the Richelson[18–21] and Dix laboratories[17, 22–24] resulted in a number of BBB-permeable NT analogs. These analogs exhibit potent antinociceptive activity following systemic administration, furthermore, they have been tested as potential antipsychotic drugs.[19–21]

Glycosylation of neuroactive peptides is a promising strategy to develop new therapies for neurological and psychiatric disorders.[25] For example, glycosylation has proven to be useful for enhancing bioavailability of opioid peptides. In this regard, improved analgesia has been reported for glycosylated deltorphin,[26] cyclized Met-enkephalin analog,[27] and linear Leu-enkephalin analogs.[28] A glycosylated NT analog found in venoms of cone snails, Contulakin-G, was recently shown to posses a potent analgesic activity.[29] When delivered intrathecally, Contulakin-G produced pronounced antinociceptive effects in rat models of inflammatory pain.[30] Two additional examples of naturally-occurring glycosylation of neuropeptides are; vespulakinin (bradykinin analog) from wasps[31, 32] and somatostatin from catfish.[33] Interestingly, the glycosylated derivatives of both neuropeptides exhibited equipotent or better bioactivity, as compared to carbohydrate-free analogs. In the present study, we investigated the effects of site-specific glycosylation on pharmacological properties of NT. Our results suggest that the glycosylated analogs exhibited low nanomolar affinities and agonist activities for neurotensin receptor subtype 1 (NTS1), and suppressed seizures with subpicomolar potency in the pharmaco-resistant model of epilepsy following intracerebroventricular (icv) injections.

Results

Design of glycosylated neurotensin analogs

To investigate how glycosylation affected pharmacological properties of NT, we designed several analogs containing O-linked sugar moieties (α-d-Gal-(1→6)-β-d-Glc (β-melibiose) and β-d-Gal-(1→3)-α-d-GalNAc (α-Thomsen-Freidenreich antigen, α-TF)) attached to position 7 of NT (Table 1). Mel-S is the Ser conjugated with β-melibiose, TF-T is the Thr conjugated with α-TF, and Lac-PEG3-E is the Glu conjugated with Lac-PEG3.The structure of glycoamino acids introduced to NT analogs is shown in Figure 1. The position 7 was specifically selected since the naturally-occurring glycosylated NT analog, Contulakin-G, has a β-d-Gal-(1→3)-α-d-GalNAc-(1→) (α-TF) attached to Thr10 in the following sequence; ZSEEGGSNATKKPYIL.[30] Therefore, Thr10 in Contulakin-G is equivalent to Pro7 in NT with respect to the active fragment “-RRPYIL” (shaded sequence), as shown below:

|

Table 1.

Neurotensin analogs studied here. Summary of mass spectrometry and HPLC analysis.

| Analog | Sequence | Mass (Calcd/Exp) |

Rta | Puritya |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurotensin | ZLYENKPRRPYIL-OH | 1671.91/1672.90 | 16.6 | 99.6 |

| NT-Mel | ZLYENK(Mel-S)RRPYIL-OH | 1985.99/1986.94 | 16.7 | 98.0 |

| NT-TF | ZLYENK(TF-T)RRPYIL-OH | 2041.04/2042.28 | 16.3 | 99.9 |

| NT(8–13) | H-RRPYIL-OH | 816.50/817.53 | 13.5 | 98.5 |

| NT(8–13)-Mel | H-(Mel-S)RRPYIL-OH | 1227.63/1228.71 | 14.8 | 98.0 |

| NT(8–13)-PEG3-Lac | H-(Lac-PEG3-E)RRPYIL-OH | 1400.74/1401.77 | 15.3 | 99.9 |

HPLC was run in a linear gradient (5–65%) of Buffer B (90% acetonitrile, 0.1% TFA) for 30 min.

Figure 1. The structure of glycoamino acids introduced to NT and the C-terminal hexapeptide, NT(8–13).

One of the sugar moieties, α-d-Gal-(1→6)-β-d-Glc (β-melibiose), was chosen based on the extensive studies of glycosylated enkephalin analogs.[34] The enkephalin-based glycopeptides were shown to increase central nervous system bioavailability. When administered intravenously (iv), the glycosylated enkephalin containing melibiose was 20-fold more potent as an analgesic than the unglycosylated parent peptide. The other sugar moiety, β-d-Gal-(1→3)-α-d-GalNAc (α-TF), was chosen based on the structure of Contulakin-G.[30] The full-length NT analogs, NT-Mel and NT-TF, had identical amino acid sequence except the different glycoamino acid (Table 1).

The C-terminal hexapeptide, NT(8–13), retained biological activity of NT, including the affinity and agonist potency for NT receptors.[35, 36] Therefore, we introduced the glycoamino acid, β–melibiose-Ser, to the N-terminus of NT(8–13). Once we discovered that all NT analogs containing “natural” glycoamino acids were very potent in the receptor binding assay, we also explored how “nonnatural” glycosylation would affect the pharmacological properties of NT. To this end, we designed a NT(8–13) analog containing “extended” glycoamino acid; a β-lactose unit linked via a PEG3-spacer (Figure 1). This particular glycoamino acid was chosen based on the commercial availability of the synthesis intermediate. The structures of all NT analogs studied here are summarized in Table 1.

Synthesis of glycosylated neurotensin analogs

For the preparation of NT-Mel, NT(8–13)-Mel, and NT-TF, Fmoc-Ser(β-Mel-Ac7)-OH and Fmoc-Thr(α-TF-Ac6)-OH were obtained from a commercial source. For the preparation of NT(8–13)-PEG3-Lac, Fmoc-Glu-(β-Lac-PEG3-amide), 4, was synthesized as shown in Figure 2. Firstly, Fmoc-Glu(OBn)-OH, 1 was activated with pentafluorophenol (PFP) in the presence of DCC to generate Fmoc-Glu(OBn)-OPFP, 2. The acylation reaction between 2 and β-Lac-PEG3-amine in CH2Cl2 and diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) generated Fmoc-Glu(OBn)-(β-Lac-PEG3-amide), 3. Debenzylation of 3 with 10% Pd/C in EtOAc under 1 atm hydrogen produced the final product, Fmoc-Glu-(β-Lac-PEG3-amide), 4. Degradation of Fmoc group was found only minimal during hydrogenation condition, and the minor impurity was removed easily in a single chromatography purification step. The overall yield (70%) of hydrogenation was sufficient enough to get the final product, 4.

Figure 2. Synthesis of Fmoc-Glu-(β-Lac-PEG3-amide), 4, the intermediate compound for the preparation of NT(8–13)-PEG3-Lac.

a) Pentafluorophenol (PFP), DCC, CH2Cl2, rt, 72%; b) DIPEA, CH2Cl2, 57%; c) H2, 10% Pd/C, EtOAc, 70%.

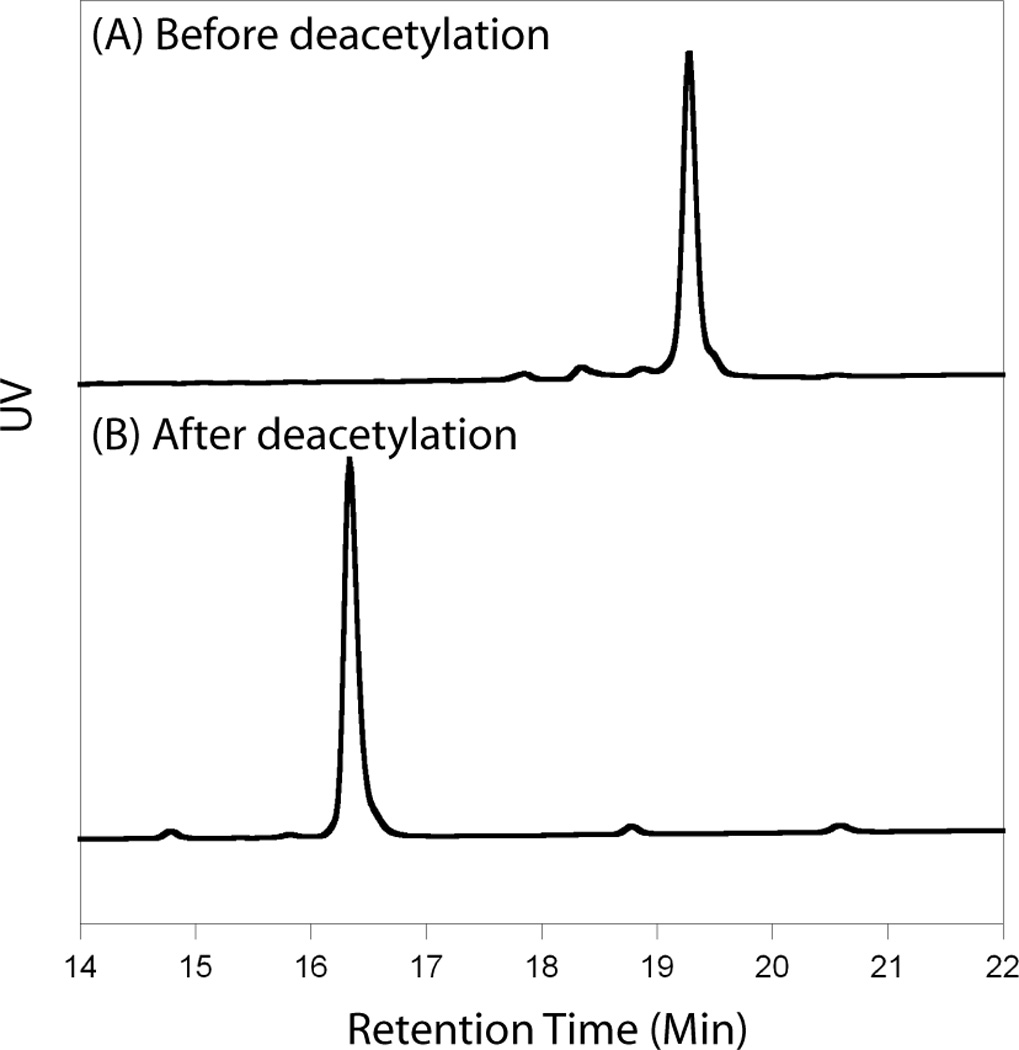

For the all NT analogs, excess of Fmoc-protected and peracetylated glycoamino acids (25~50 µmol) were incorporated manually. The peptides were synthesized using the preload Fmoc-Wang resin, and PyBop™ was used as coupling reagents in the presence of DIPEA. Fmoc group was removed during the last synthesis step. After peptide synthesis, NTanalogs were cleaved from the resin by incubation with reagent K (TFA/water/ethanedithiol/phenol/thioanisole) for 2 h, precipitated with methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) at −20 °C for 30 min, and purified by reversed-phase HPLC (RP-HPLC). After the purification of peracetylated NT analogs was completed, deacetylation reaction was performed in 50 mM of sodium methoxide/methanol solution for 2 h. The progress of deacetylation was monitored by RP-HPLC. The change of HPLC retention time for the representative NT analog, NT-TF, is shown in Figure 3. The chemical identity of the final products was confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Table 1).

Figure 3. HPLC profile of NT-TF before deacetylation (A) and after deacetylation (B).

The retention time changed from 19.5 min to 16.3 min during deacetylation reaction. The analogs were purified by RP-HPLC using a semi-preparative C18 column in a linear gradient (5–65%) of Buffer B (90% acetonitrile, 0.1% TFA). The molecular weight of the analogs was confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

Receptor binding and agonist activities

The binding affinity of NT analogs for human recombinant NTS1 receptor was tested with europium-labeled NT (Eu-NT) using membrane preparations derived from HEK-293 cells. The replacement of fluorescence of Eu-NT was detected as a function of the concentration of NT analogs (Figure 4, top). Competition binding curves were analyzed using the sigmoidal dose-response (variable slope), classical equation for nonlinear regression analysis, yielding Ki values reported in Table 2. Neither glycosylation nor truncation affected the binding affinity for NTS1. All studied analogs retained the high affinity for the receptor, similar to that measured for the unmodified NT. Even the truncated NT analog containing the nonnatural glycoamino acid (NT(8–13)-PEG3-Lac) displayed a subnanomolar Ki, further emphasizing the critical role of the C-terminal hexapeptide in the receptor recognition.

Figure 4. Receptor binding curve for NT analogs (top) and the agonist activity from functional assay (bottom).

The binding affinity of NT and NT-TF for NTS1 remains same, 0.5 nM. EC50 values in intracellular calcium mobilization assay for NT and NT-TF are 1.1 nM and 0.9 nM, respectively.

Table 2.

Receptor binding assay and agonist activity for NTS1, and anticonvulsant assay in 6 Hz model of epilepsy.

| Analog | Receptor Binding Ki [nM] |

Agonist Activity EC50 [nM] |

Anticonvulsant Assay, icv ED50 (nmol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurotensin | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.0010 |

| NT-Mel | 1.0 ± 0.3 | n/d | 0.0004 |

| NT-TF | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.0004 |

| NT(8–13) | 0.2 ± 0.1 | n/d | 0.0011 |

| NT(8–13)-Mel | 0.4 ± 0.1 | n/d | 0.0004 |

| NT(8–13)-PEG3-Lac | 0.3 ± 0.1 | n/d | < 0.0010 |

The ability of a selected NT analog to stimulate intracellular Ca2+ mobilization was tested in HEK-293T cells expressing human NTS1 (Figure 4, bottom). The NT-TF analog retained full potency as NTS1 agonist, indicating that the presence of glycoamino acids did not affect the binding mechanism of the peptide to the receptors (Table 2). The activation of intracellular Ca2+ mobilization was concentration-dependent with EC50 values of 1.1 nM and 0.9 nM for NT and NT-TF, respectively. The EC50 values for stimulation of intracellular Ca2+ release confirmed the comparable binding affinities of NT and NT-TF.

Anticonvulsant activity

To investigate the in vivo activity of the NT analogs, we tested their ability to suppress seizures in an animal model of epilepsy. This assay was chosen based on a preliminary report that the glycosylated NT analog, Contulakin-G, possessed the potent anticonvulsant activity in the Frings mouse model of epilepsy (USPTO; patent 6,696,408). All analogs were evaluated in the mouse 6 Hz partial psychomotor seizure model following icv injections (Figure 5). Animals were considered protected if they did not display a motor seizure characterized by vibrissae twitching, jaw chomping, or forelimb clonus. The median effective dose (i.e., ED50) calculated from dose-response curves are reported in Table 2. The ED50 values for all the analogs were found to be in the picomolar range. It is noteworthy to mention that three analogs; NT-Mel, NT-TF and NT(8–13)-Mel, exhibited subpicomolar potency. The glycosylated NT analogs were not found to be anticonvulsant following systemic administration (intraperitoneally, ip) at doses as high as 10 mg·kg−1, suggesting that the glycosylation did not improve the CNS bioavailability for these peptides.

Figure 5. Dose response curves of NT and a representative glycosylated NT analog, NT-TF, in the 6 Hz (32 mA) anticonvulsant assay in mice following the icv administration.

The log values of dose were plotted against the percentage of mice protected from seizures. The ED50 values for NT and NT-TF were 1.0 pmol and 0.4 pmol, respectively.

Discussion

In this work, we describe how “nature-inspired“ glycosylation of NT analogs affected their pharmacological properties. We present a novel design strategy, solid-phase chemical synthesis of several glycopeptides analogs, including synthesis of a nonnatural glycoamino acid, as well as an in vitro pharmacological characterization of the resulting analogs (the receptor binding and agonist activities), and in vivo pharmacology in a mouse model of pharmacoresistant epilepsy. Our design strategy of the glycosylated analogs is very unique, since it is based on studying peptide-based marine natural products and available SAR data on NT analogs. Despite numerous studies on engineering glycosylated neuropeptides,[25, 37] to best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive study of applying natural product-inspired posttranslational modifications to bioactive fragments of neuropeptides.

NT analogs containing O-linked sugar moieties (α-d-Gal-(1→6)-β-d-Glc and β-d-Gal-(1→3)-α-d-GalNAc) or β-lactose unit linked to the peptide via a PEG3-spacer, had comparable receptor binding properties, suggesting that the relatively bulky modification did not interfere with the peptide-receptor interactions. Even the presence of nonnatural glycoamino acid, β-lactose linked via a short PEG spacer, did not change receptor binding affinity. Furthermore, glycosylation did not affect the agonist activity of the analogs. Our findings are also different from those reported on Contulakin-G and its deglycosylated analog, [Thr10]Contulakin-G,[30] since the disaccharide-free analog had over 40-fold higher affinity, as well as over 30-fold higher agonist potency for human NTS1. The apparent differences of how glycosylation affected the receptor affinities and agonist potencies of NT (this work) and Contulakin-G [30] suggest that these two peptides may have different binding mechanisms to NT receptors: perhaps the shorter length of NT can better accomodate the sugar moiety in the complex with the target receptor. These results are encouraging in further explorations of neo-glycopeptide NT analogs as a strategy to improve the bioavailability.

Structure–activity studies on NT showed that its C-terminal hexapeptide NT(8–13) was equipotent to, or even more potent than, the native NT on binding to NT receptor (membrane preparations from human frontal cortex) in radioligand binding assay, while maintaining the same biological and pharmacological properties.[9] Our results obtained from the fluorescence-based binding assay are consistent with previous studies; e.g., Ki values of 0.5 ± 0.2 nM and 0.2 ± 0.1 nM, for NT and NT(8–13), respectively. Both NT and NT(8–13) displayed equipotent anticonvulsant ED50 values (i.e., 0.0010 nmol, icv). Since the glycosylated C-terminal hexapeptide also maintained the same as NT in vitro and in vivo activities, this finding supported the critical role of the “RRPYIL” motif. The apparent correlation between the receptor affinity, agonist potency and anticonvulsant activity suggest that the suppression of seizures might be accounted for by targeting NT receptors.

Perhaps the most important finding from our study is that NT and the glycosylated analogs exhibited picomolar, or even subpicomolar, anticonvulsant potencies in the 6 Hz model of epilepsy. Although previous studies reported correlations between NT and seizures,[38, 39] there is only one reported example of the anticonvulsant activity of a NT analog (Contulakin-G) determined in the Frings mouse model of epilepsy (USPTO 6,696,408, Figures 19–20). Although the hypothermic activity of NT may in part account for some of its anticonvulsant activity, this neuropeptide was recently shown to potentiate GABAergic activity in rat hippocampus CA1 region.[40] Since NT is known to exert hypothermia, the anticonvulsant activity observed in the present study may contribute to the anticonvulsant action of the modified NT analogs described herein; however, we did not observe a direct correlation between the changes in the body temperature and the percent of animals protected in the seizure test. The mechanism of the NT-mediated anticonvulsant activity remains unknown, and needs further pharmacological studies.

The immediate impact of the discovery that NT and its glycosylated analogs exhibit high potencies in suppressing seizures is a new research direction of exploring BBB-permeable NT analogs as potential first-in-class antiepileptic drugs. The unexpected, anticonvulsant role of NT in the brain will trigger more mechanistic studies carried out by neuropharmacologists. Furthermore, many research groups, including academic labolatories, pharma and biotech companies, have been working for two decades on NT analogs with improved bioavailability.[1–21] As a result, a number of CNS-active lead compounds derived from NT analog libraries have been identified.[8, 16] We hope that this work will encourage these laboratories to test their BBB-permeable NT agonists in various models of epilepsy (for example using the NIH-sponsored Anticonvulsant Screening Program).

Experimental Section

General

General organic chemicals were obtained from Aldrich Chemical Corporation and were used without prior purification. β-Lac-PEG3-amine, Fmoc-Ser(β-Mel-Ac7)-OH, and Fmoc-Thr(α-TF-Ac6)-OH were purchased from Sussex Research Laboratories Inc. Fmoc-protected amino acids and preload Fmoc-Leu-Wang resins were obtained from Chem-Impex International Inc. Reactions were performed under N2 atmosphere, unless otherwise indicated. Chromatography refers to flash chromatography on silica gel (Whatman 230–400 mesh ASTM silica gel). Analytical thin layer chromatography (TLC) was performed using Whatman glass plates coated with 0.25 mm thickness of silica gel containing PF254 indicator. NMR spectra were recorded at 400 MHz (1H), 100 MHz (13C), and 376 MHz (19F) at 25 °C. Proton and carbon chemical shifts are given in ppm with relative to TMS as the internal standard; external standards were used for 19F (CFCl3,δ=0.00). MALDI/TOF MS were determined at the University of Utah Core Facility. Optical rotations were measured on a polarimeter (Perkin-Elmer, model 343) using quartz cell with 10 cm path length.

Fmoc-Glu(OBn)-OPFP, 2

DCC (0.246 g, 1.19 mmol) was added to a solution of Fmoc-Glu(OBn)-OH (0.459 g, 1 mmol) and PFP (0.190 g, 1.03 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL) at 0 °C and then stirred at room temperature for 16 h, filtered, washed with NaHCO3 solution, and purified by chromatography with hexane/EtOAc (3:1) to afford 2 (0.45 g, 72%) as white solid: Rf =0.25 (CH2Cl2/CH3OH, 7:1); mp: 144.0–146.0 °C; [α]20D =−13.0 (c = 3.8 in CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ=7.66 (d, J =7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.49 (t, J =6.0, 5.2 Hz, 2H), 7.18–7.30 (m, 9H), 5.51 (d, J =8.4 Hz, 1H), 5.06 (s, 2H), 4.70 (m, 1H), 4.35 (m, 2H), 4.12 (t, J =6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.46 (m, 2H), 2.34(m, 1H), 2.10 ppm (m, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ=172.60, 168.62, 156.126, 143.95, 143.77, 141.56, 135.75, 128.86, 128.67, 128.57, 128.02, 127.34, 125.26, 120.26, 67.54, 67.08, 53.55, 47.32, 30.31, 27.27 ppm; 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3): δ=−152.55 (d, J =15.6 Hz, 2F), −157.33 (t, J =24.4, 22.8 Hz, 1F), −162.06 ppm (t, J =24.4, 22.8 Hz, 2F); HRMS (MALDI) (m/z) (MNa+) calcd for C33H24F5NO6Na: 648.1416, found: 648.1422.

Fmoc-Glu(OBn)-(β-Lac-PEG3-amide), 3

DIPEA (89.5 µL, 0.514 mmol) was added to a stirred solution of 2 (0.236 g, 0.514 mmol) and β-Lac-PEG3-amine (0.329 g, 0.428 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (10 mL). After stirring for 16 h, the reaction mixture was concentrated, and purified with chromatography (hexane/EtOAc 1:1) to afford 3 (0.296 g, 57%) as white amorphous solid: Rf = 0.41 (EtOAc); [α]20D =−4.6 (c = 0.5 in CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ=7.70 (d, J =7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.53 (d, J =6.8 Hz, 2H), 7.24–7.34 (m, 9H), 6.67 (m, 1H), 5.64 (d, J =7.2 Hz, 1H), 5.24 (d, 2H), 5.13-5.00 (m, 4H), 4.85 (m, 2H), 4.46-4.12 (m, 6H), 4.01 (m, 4H), 3.85 (m, 1H), 3.72 (m, 2H), 3.60 (m, 1H), 3.52-3.30 (m, 10H), 2.49-2.35 (m, 2H), 1.82–2.07 ppm (m, 23H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ=173.24, 171.34, 170.66, 170.55, 170.40, 170.30, 170.06, 169.35, 158.91, 143.95, 141.49, 138.97, 135.39, 128.82, 128.55, 128.47, 127.99, 126.73, 125.34, 120.26, 101.34, 100.89, 76.51, 72.92, 71.83, 71.19, 70.82, 70.72, 70.54, 70.36, 69.75, 69.47, 69.29, 67.27, 66.74, 64.60, 62.27, 60.96, 54.26, 47.33, 39.61, 30.85, 30.52, 29.93, 28.73, 21.08, 21.02, 20.97, 20.85, 20.75, 19.34 ppm; HRMS (MALDI) (m/z) (MNa+): calcd for C59H72N2O25Na: 1231.4316, found: 1231.4284.

Fmoc-Glu-(β-Lac-PEG3-amide), 4

A solution of 3 (0.270 g, 0.24 mmol) and 10% Pd/C (54 mg) in EtOAc (10 mL) was stirred under 1 atm hydrogen for 48 h. The mixture was then filtered through Celite, and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. Chromatography (EtOAc/MeOH 3:1) gave 4 (0.202 g, 70%) as clear oil: Rf = 0.52 (EtOAc/MeOH, 3:1); [α]20D =−3.6 (c = 1 in CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ=7.68 (d, J =7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.50 (m, 2H), 7.29–7.33 (t, J =6.8 Hz, 2H), 7.22 (d, J =4.4 Hz, 2H), 6.99(br, 1H), 5.99 (br, 1H), 5.24 (s, 1H), 5.11 (t, J =9.2 Hz, 1H), 5.01 (t, J =8.4, 9.6 Hz, 1H), 4.80–4.89 (m, 2H), 4.45-4.37 (m, 3H), 4.28 (m, 3H), 4.12 (m, 1H), 4.05-3.94 (m, 3H), 3.81 (m, 1H), 3.76-3.73 (m, 2H), 3.64-3.34 (m,12H), 2.37 (m, 2H), 1.89–2.07 ppm (m, 23H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ=170.79, 170.64, 170.39, 170.32, 170.20, 170.12, 169.39, 144.04, 143.95, 141.44, 127.98, 127.35, 125.37, 120.22, 101.26, 100.84, 76.43, 72.89, 71.83, 71.18, 70.77, 70.69, 70.31, 69.67, 69.40, 69.32, 67.35, 66.82, 64.58, 62.22, 60.98, 54.26, 47.25, 39.56, 30.83, 29.89, 21.23, 21.07, 21.00, 20.94, 20.83, 20.73, 19.34 ppm; HRMS (MALDI) (m/z) (MNa+): calcd for C52H66N2O25Na: 1141.3847, found: 1141.3832.

Peptide synthesis, purification, and characterization

Peptides were synthesized on Symphony automatic peptide synthesizer (Protein Technologies Inc.) using Fmoc SPPS methods on 25 µmol scale. Preload Fmoc-Leu-Wang resin (Chem-Impex international), PyBop™ as a coupling reagent, and piperidine (20%) as a deprotection reagent, were used. Nonnatural amino acids were coupled manually using the previously listed reagents, and Fmoc group was removed during the last step. After the synthesis, the peptide was cleaved from the resin by incubating in reagent K (TFA/water/ethanedithiol/phenol/thioanisole, 90/5/2.5/7.5/5 by volume) for 2 h, was precipitated with MTBE (6 mL) at −20 °C for 30 min, and purified by RP-HPLC. After the purification of peracetylated NT analogs was completed, the peracetylated NT analogs was hydrolyzed in 50 mM CH3ONa/MeOH for 2 h to remove the acetyl group, and purified by RP-HPLC using C18 semi-preparative column (Vydac, 4.6 mm × 250 mm) in a linear gradient (5–65%) of Buffer B (90% acetonitrile, 0.1% TFA). The flow rate was 5 mL·min−1, and the elution was monitored by UV detection at 220 nm. Prepared peptides were quantified by measuring UV absorbance at 274.6 nm (molar absorbance coefficient = 1,420.2). The molar masses of peptides were determined by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

Receptor binding assay

Competitive binding assays were performed on membrane preparation using Eu-NT (both from Perkin-Elmer), and the samples were tested in quadruplicate. Membrane preparation, Eu-NT, and ligands were diluted in binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 25 µM EDTA, 0.2% BSA). Samples were incubated at room temperature for 90 min in a total volume of 200 µL. Following the incubation, samples were washed 4 times with wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2). Enhancement solution (200 µL) was added, and the plates were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The plates were read on a Wallace VICTOR3 instrument using the standard Eu-TRF measurement (340 nm excitation, 400 µs decay, and emission collection at 615 nm for 400 µs). Competition curves were analyzed with GraphPad Prism using the sigmoidal dose-response (variable slope) classical equation for nonlinear regression analysis.

Agonist activity

HEK-293T cells transiently co-transfected with NTS1 were plated in 96-well plates, and grown to confluence. After incubation with Fluo-3/Am, cells were washed with HBS, and equilibrated for 20 min. The fluorescence emission due to intracellular calcium mobilization elicited by agonists of the expressed receptor was determined with a fluorescence imaging plate reader (FLIPR™, Molecular Devices Corporation). The results were analyzed using SOFTmax Pro and GraphPad Prism software. This assay was performed by Millipore Inc.

Anticonvulsant assay

The analogs were tested in the 6 Hz partial psychomotor seizure model following icv administration (total volume, 5 µL) to CF-1 male adult mice (Charles River). Mice were dosed with the analogs (icv). Thirty min later, animals were challenged with 6 Hz, 32 mA, 3 sec corneal stimulation. Animals were considered protected if they did not display a motor seizure characterized by vibrissae twitching, jaw chomping, or forelimb clonus. The fitted curves were analyzed with GraphPad Prism using the dose-response classical equation for nonlinear regression analysis. ED50 values were determined based on 50% protection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Epilepsy Therapy Grants Program from the Epilepsy Research Foundation, the University of Utah Startup Funds, and the Anticonvulsant Screening Program (ASP) at the NIH/NINDS. GB also acknowledges a financial support from the NIH grants R21 NS055845 and Program Project GM 48677. We would like to thank the ASP Director, Mr. James Stables, for numerous discussions.

References

- 1.Vincent J-P, Mazella J, Kitabgi P. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1999;20:302–309. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01357-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bissette G, Nemeroff CB, Loosen PT, Prange JAJ, Lipton MA. Nature. 1976;262:607–609. doi: 10.1038/262607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kitabgi P, De Nadai F, Labbe-Jullie C, Dubuc I, Nouel D, J C, Masuo Y, Rostene W, Woulfe J, Lafortune L. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 1992;15:313A–314A. doi: 10.1097/00002826-199201001-00162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nemeroff CB, Bissette G, Manberg PJ, Osbahr AJ, III, Breese GR, Prange AJJ. Brain Res. 1980;195:69–84. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90867-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Rodhan NRF, Richelson E, Gilbert JA, McCormick DJ, Kanba KS, Pfenning MA, Nelson A, Larson EW, Yaksh TL. Brain Res. 1991;557:227–235. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90139-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dobner PR. Peptides. 2006;27:2405–2414. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rostene W, Brouard A, Dana C, Masuo Y, Agid F, Vial M, Lhiaubet AM, Pelaprat D. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;668:217–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb27352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boules M, Fredricksona P, Richelson E. Peptides. 2006;27:2523–2533. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanba KS, Kanba S, Nelson A, Okazaki H, Richelson E. J. Neurochem. 1988;50:131–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb13239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bredeloux P, Cavelier F, Dubuc I, Vivet B, Costentin J, Martinez J. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:1610–1616. doi: 10.1021/jm700925k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sefler AM, He JX, Sawyer TK, Holub KE, Omecinsky DO, Reily MD, Thanabal V, Akunne HC, Cody WL. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:249–257. doi: 10.1021/jm00002a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bittermann H, Einsiedel J, Hübner H, Gmeiner P. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:5587–5590. doi: 10.1021/jm049644y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.García-Garayoa E, Allemann-Tannahill L, Bläuenstein P, Willmann M, Carrel-Rémy N, Tourwé D, Iterbeke K, Conrath P, Schubiger PA. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2001;28:75–84. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(00)00190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Einsiedel J, Hübner H, Hervet M, Härterich S, Koschatzky S, Gmeiner P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:2013–2018. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.01.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Couder J, Tourwé D, Van Binst G, Schuurkens J, Leysen JE. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 1993;41:181–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1993.tb00129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kokko KP, Hadden MK, Price KL, Orwig KS, See RE, Dix TA. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lundquist JT, IV, Dix TA. J. Med. Chem. 1999;42:4914–4918. doi: 10.1021/jm9903444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong F, Zaidi J, Cusack B, Richelson E. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2002;10:3849–3858. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00342-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tyler-McMahon BM, Stewart JA, Farinas F, McCormick DJ, Richelson E. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000;390:107–111. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00877-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cusack B, Boules M, Tyler BM, Fauq A, McCormick DJ, Richelson E. Brain Res. 2000;856:48–54. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02363-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tyler BM, Douglas CL, Fauq A, Pang YP, Stewart JA, Cusack B, McCormick DJ, Richelson E. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1027–1034. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kokko KP, Hadden MK, Orwig KS, Mazella J, Dix TA. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:4141–4148. doi: 10.1021/jm0300633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lundquist JT, IV, Büllesbach EE, Dix TA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2000;10:453–455. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lundquist JT, IV, Dix TA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999;9:2579–2582. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00420-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polt R, Dhanasekaran M, Keyari CM. Med. Res. Rev. 2005;25:557–585. doi: 10.1002/med.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Negri L, Lattanzi R, Tabacco F, Orrù L, Severini C, Scolaro B, Rocchi R. J. Med. Chem. 1999;42:400–404. doi: 10.1021/jm9810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egleton RD, Mitchell SA, Huber JD, Janders J, Stropova D, Polt R, Yamamura HI, Hruby VJ, Davis TP. Brain Res. 2000;881:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02794-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egleton RD, Mitchell SA, Huber JD, Palian MM, Polt R, Davis TP. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;299:967–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allen JW, Hofer K, McCumber D, Wagstaff JD, Layer RT, McCabe RT, Yaksh TL. Anesth. Analg. 2007;104:1505–1513. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000219586.65112.FA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Craig AG, Norberg T, Griffin D, Hoeger C, Akhtar M, Schmidt K, Low W, Dykert J, Richelson E, Navarro V, Mazella J, Watkins M, Hillyard D, Imperial J, Cruz LJ, Olivera BM. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:13752–13759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.13752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshida H, Geller RG, Pisano JJ. Biochemistry. 1976;15:61–64. doi: 10.1021/bi00646a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gobbo M, Biondi L, Filira F, Scolaro B, Rocchi R, Piek T. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 1992;40:54–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1992.tb00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen L, Jensen KJ, Tejbrant J, Taylor JE, Morgan BA, Barany G. J. Pept. Res. 2000;55:81–91. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2000.00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elmagbari NO, Egleton RD, Palian MM, Lowery JJ, Schmid WR, Davis P, Navratilova E, Dhanasekaran M, Keyari CM, Yamamura HI, Porreca F, Hruby VJ, Polt R, Bilsky EJ. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004;311:290–297. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.069393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carraway R, Leeman SE. Peptides: Chemistry, Structure and Biology. Ann Arbor: Ann Arbor Science; 1975. pp. 679–685. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kitabgi P, Poustis C, Granier C, Van Rietschoten J, Rivier J, Morgat JL, Freychet P. Mol. Pharmacol. 1980;18:11–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elliott S, Lorenzini T, Asher S, Aoki K, Brankow D, Buck L, Busse L, Chang D, Fuller J, Grant J, Hernday N, Hokum M, Hu S, Knudten A, Levin N, Komorowski R, Martin F, Navarro R, Osslund T, Rogers G, Rogers N, Trail G, Egrie J. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:414–421. doi: 10.1038/nbt799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sperk G, Wieser R, Widmann R, Singer EA. Neuroscience. 1986;17:1117–1126. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shulkes A, Harris QL, Lewis SJ, Vajda JE, Jarrott B. Neuropeptides. 1988;11:77–81. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(88)90014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li S, Geiger JD, Lei S. J. Neurophysiol. 2008;99:2134–2143. doi: 10.1152/jn.00890.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.