Abstract

The development of new approaches for the treatment of antimicrobial-resistant infections is an urgent public health priority. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogen, in particular, is a leading source of infection in hospital settings, with few available treatment options. In the context of an effort to develop antivirulence strategies to combat bacterial infection, we identified a series of highly effective small molecules that inhibit the production of pyocyanin, a redox-active virulence factor produced by P. aeruginosa. Interestingly, these new antagonists appear to suppress P. aeruginosa virulence factor production through a pathway that is independent of LasR and RhlR.

Introduction

The human pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a leading cause of hospital-acquired infections, posing a particular threat to cystic fibrosis patients, third-degree burn victims, and patients with implanted medical devices.1–3 P. aeruginosa is a versatile pathogen, possessing a number of adaptations – an outer membrane of low permeability, a multitude of efflux pumps, and various degradative enzymes that disable antibiotics. These features combine to limit the range of effective treatment options.3 Of particular concern is the propensity of the P. aeruginosa pathogen to develop resistance to traditional antibiotic therapeutics.4

Standard antimicrobial therapeutics typically function by bactericidal or bacteriostatic mechanisms; however, a widespread reliance on established classes of antibiotics has exacerbated the growing crisis of drug resistance. To address this challenge, we have been pursuing alternative antivirulence strategies for the treatment of bacterial infections.5 The rationale is that when virulence traits are suppressed, the bacteria are rendered benign and are more readily cleared by the host immune system. Importantly, this antivirulence approach is expected to reduce the selective pressure for the spread of drug–resistant mutants and could therefore lead to therapies that retain their efficacy over greater time spans compared to traditional antibiotics.6 In P. aeruginosa, as in many bacterial pathogens, virulence is controlled through quorum sensing – a process of cell-to-cell communication that modulates group behaviors in a population density dependent manner.7, 8 Quorum sensing pathways rely on the production, release, and detection of small molecule signals that regulate virulence genes.

In P. aeruginosa, quorum sensing and virulence are connected by the signaling pathways shown in Fig. 1.9, 10 At the top of this signaling network are LasI – a synthase that produces the acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) signal, 3OC12-HSL – and LasR, the transcriptional regulator that detects this signal.11,12, 13 The LasR:3OC12-HSL complex influences P. aeruginosa behavior by activating expression of many genes, including genes encoding virulence factors, as well as genes encoding additional quorum-sensing circuits.11, 14, 15 One quorum-sensing system activated by LasR:3OC12-HSL is the RhlIR system. RhlI produces a second AHL (C4-HSL), which is detected by the transcriptional regulator RhlR.16–18 The RhlR:C4-HSL complex also regulates virulence genes and other components of the signaling pathway.11, 16, 19, 20 One key virulence factor produced at high cell density in response to the Las and Rhl AHL signal molecules is the redox-active small molecule pyocyanin. Because the oxidized form of pyocyanin imparts a green color to P. aeruginosa cultures, production of pyocyanin is conveniently monitored by UV/Vis absorbance. Multiple other factors also influence virulence factor production, including the transcription factor QscR and the PQS quorum-sensing system, which produces and detects quinolone signals.9, 10

Figure 1.

A simplified diagram of quorum sensing in P. aeruginosa along with inhibitor 1.

Substantial prior work from our laboratory22 and others23 has focused on designing antagonists of LasR-type receptors based on the structures of the native signals, in the present case, 3OC12-HSL. The ligand binds and stabilizes the receptor, promoting dimerization, DNA binding, and gene regulation.24, 25 An effective small molecule antagonist must prevent activation, either through destabilization of the protein or through stabilization of an inactive conformation. For example, in the homologous transcriptional regulator CviR from Chromobacterium violaceum, inhibitors stabilize a conformation of the CviR dimer that is incapable of binding DNA.26

We recently reported that thiolactone 1 (Fig. 1), a structural analog of the native AHL signals, is a potent inhibitor of pyocyanin production in vivo.22 This antagonist interacts with both LasR and RhlR, however, inhibition through RhlR results in the key antivirulence effects of the compound. From the standpoint of applications as a probe or drug candidate, a weakness of this structure – or of any inhibitor possessing a lactone or thiolactone moiety – is its sensitivity to chemical and enzymatic hydrolysis of the (thio)lactone ring.27–30 To overcome this structural liability, we sought to design, synthesize, and evaluate inhibitors that lack the problematic lactone moiety.30–33 We describe herein the development of a series of potent pyocyanin inhibitors. The structure of the optimized antagonists evolved from the architectures of both the native signal and inhibitor 1; however, these new compounds inhibit pyocyanin production by a different mechanism than does 1.

Results and Discussion

The common feature of the AHL quorum sensing signals is the homoserine lactone (HSL) head group, which forms key hydrogen-bonding interactions with the cognate receptor binding pocket (2, Fig. 2); the tail domains generally experience only van der Waals interactions in a hydrophobic pocket of the protein.34, 35 Therefore, a replacement structure for the HSL functionality should maintain the key hydrogen-bond interactions with the receptor and perhaps find additional opportunities for enhanced binding. Along these lines, other groups have explored the use of arenes as HSL replacements.31–33, 36

Figure 2.

Key interactions of the homoserine lactone (2) with LasR34, 35 and modeled interactions of 3 with LasR.

At the outset of our studies, we modeled a series of head group candidates in the LasR binding pocket through a virtual screen using AutoDock.37 Heterocycles, including aminopyridine 3, were identified as promising candidates, with the capacity to maintain native binding contacts and the potential for additional hydrogen-bonding interactions. The chemically stable aminopyridine moiety was viewed as a particularly attractive platform for the synthesis of a focused small molecule library.

With the goal of evaluating the effectiveness of the aminopyridine head group as a replacement for the native HSL, we first investigated analogs possessing these surrogate head groups along with either the native 3OC12 tail of the LasR signal (Fig. 3, 4) or a simplified C12 tail (5). In principle, any head group that binds LasR is of interest, even if the compound possesses agonist activity. Based on our studies toward inhibitor 1, and previous work in the field,23 we anticipated that introduction of an appropriately functionalized tail moiety could transform an agonist into an antagonist. Of course, a new head group structure with inherent antagonistic activity would be of particular interest. Hits identified from the initial head group study would then be merged with a functionalized tail motif to form hybrid analogs (e.g., 6) that should have higher potency as antagonists and enhanced in vivo stability.

Figure 3.

Library design and representative examples.

Figure 4.

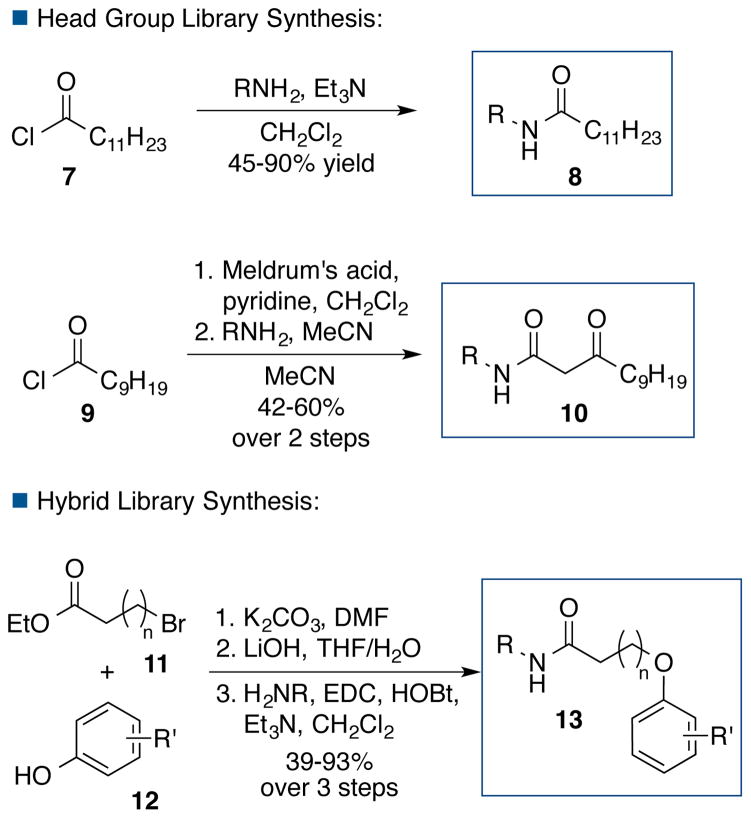

Library synthesis.

For the head group library, acylation of an amino-heterocycle furnished a series of C12 tail analogs (8, Fig. 4). To install the β-ketoamide of the 3OC12 tail, we generated the Meldrum’s acid adduct prior to addition of an amino-heterocycle, to furnish 10. Hybrid structures (13) were generally synthesized via SN2 displacement of an alkyl halide (11) with a phenol (12) to incorporate the tail functionality, followed by appendage of the head group via amide formation.

The compounds were assayed for anti-quorum sensing activity at a concentration of 100 μM in wild-type P. aeruginosa PA14. Deletion of lasR or rhlR dramatically reduces the ability of P. aeruginosa to produce pyocyanin, so pyocyanin was used as a read-out for activity based on its absorbance at 695 nm, as in our previous studies.22 The efficacy of the compounds at reducing pyocyanin levels was calculated with respect to wild-type levels of pyocyanin, where a wild-type level of pyocyanin was assigned a 0% efficacy, and an absorbance equal to the background medium was assigned as 100% efficacy. Agonists that increased pyocyanin production were assigned negative efficacy values. Absorbance at OD600 was also monitored to ensure that potential inhibitors did not impair growth. None of the compounds affected P. aeruginosa growth.

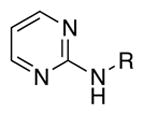

Inspired by virtual screen hit 3, we systematically examined a series of pyridine, pyrimidine and pyrazine head groups with either a 3OC12 or C12 tail (Table 1, entries 1–6, 7–12, respectively). The 4-aminopyridine (entry 3) and 4-aminopyrimidine (entry 4) 3OC12 analogs were the most active compounds. The 2-aminopyridine (entry 1) was a less effective inhibitor, suggesting that incorporation of the nitrogen in the heterocycle para to the amine is key to activity, while the presence of a second nitrogen in the ortho-position was also tolerated.

Table 1.

Pyridine, pyrimidine, and pyrazine head groups.

| Entry | Substrate | Efficacy (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

44 ± 13 |

| 2 |

|

10 ± 9 |

| 3 |

|

63 ± 2 |

| 4 |

|

64 ± 0.8 |

| 5 |

|

21 ± 13 |

| 6 |

|

−0.51 ± 4 |

| 7 |

|

55 ± 3 |

| 8 |

|

34 ± 3 |

| 9 |

|

28 ± 11 |

| 10 |

|

55 ± 8 |

| 11 |

|

−38 ± 3 |

| 12 |

|

23 ± 3 |

|

| ||

|

| ||

We further probed the 4-aminopyridine scaffold by incorporating a variety of substituents around the pyridine ring (Table 2, entries 1–10). We also examined related pyridines (entries 11–14), as well as indole and benzofuran motifs (entries 15–23). Although most analogs were less effective than the parent 4-aminopyridine (63% efficacy), incorporation of a fluoride at the 2-position along with removal of the ketone in the tail led to a compound that decreased pyocyanin production by 70% (entry 7).

Table 2.

4-Aminopyridine and other head groups.

| Entry | Substrate | Efficacy (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

−19 ± 3 |

| 2 |

|

−24 ± 2 |

| 3 |

|

−17 ± 2 |

| 4 |

|

−5.1 ± 1 |

| 5 |

|

24 ± 1 |

| 6 |

|

34 ± 5 |

| 7 |

|

70 ± 2 |

| 8 |

|

−8.5 ± 3 |

| 9 |

|

−12 ± 3 |

| 10 |

|

27 ± 3 |

| 11 |

|

13 ± 3 |

| 12 |

|

7.7 ± 5 |

| 13 |

|

−15 ± 4 |

| 14 |

|

−42 ± 2 |

| 15 |

|

−11 ± 3 |

| 16 |

|

1.5 ± 8 |

| 17 |

|

12 ± 3 |

| 18 |

|

−1.0 ± 3 |

| 19 |

|

9.3 ± 4 |

| 20 |

|

−9.2 ± 4 |

| 21 |

|

4.4 ± 3 |

| 22 |

|

0.60 ± 4 |

| 23 |

|

6.1 ± 4 |

|

| ||

|

| ||

We next evaluated a series of hybrid compounds, combining the 4-aminopyridine head groups with the 3-bromophenol tail group from the previously identified inhibitor 1. At the outset, we examined two linker lengths (Table 3, entries 1–5, 7) and found the combination of a methoxy in the 2-position of the head group along with the longer five-methylene linker to be most effective, reducing pyocyanin levels by 73% (entry 7). Further investigation of the linker length (entries 5–10) revealed the four-methylene linker to be the most active (81%, entry 6); increasing to a five- or six-methylene linker led to reduced efficacy (73–75%, entries 7 and 9) and incorporation of an additional methylene group led to further deterioration of activity (60%, entry 10). The incorporation of a ketone at C3 in the linker significantly decreased antagonist activity (40%, entry 8).

Table 3.

Head group study of hybrids.

| Entry | Substrate | Efficacy (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

21 ± 5 |

| 2 |

|

53 ± 1 |

| 3 |

|

32 ± 4 |

| 4 |

|

31 ± 6 |

| 5 |

|

20 ± 1 |

| 6 |

|

81 ± 6 |

| 7 |

|

73 ± 2 |

| 8 |

|

40 ± 6 |

| 9 |

|

75 ± 3 |

| 10 |

|

60 ± 2 |

| 11 |

|

27 ± 7 |

| 12 |

|

41 ± 9 |

| 13 |

|

16 ± 5 |

| 14 |

|

15 ± 7 |

| 15 |

|

89 ± 5 |

| 16 |

|

43 ± 8 |

| 17 |

|

95 ± 5 |

| 18 |

|

99 ± 0.3 |

| 19 |

|

23 ± 7 |

| 20 |

|

62 ± 6 |

| 21 |

|

44 ± 8 |

| 22 |

|

80 ± 8 |

| 23 |

|

15 ± 7 |

|

| ||

| ||

In our initial head group studies, the 4-aminopyrimidine was as efficacious as the 4-aminopyridine. We revisited this motif in the hybrid series (entries 11–14). The addition of a methoxy group to the 6-position increased activity (entry 11 vs. entry 12), but a methoxy group was not tolerated in the 2-position (entries 13–14). The best analog of this series had an efficacy of only 41% (entry 12); accordingly, we returned to the 4-aminopyridine scaffold for further investigation.

Installation of other inductively withdrawing groups at the 2-position in the head group led to even more effective analogs: incorporation of a chloride (entry 15) afforded 89% efficacy and, most notably, a trifluoromethyl group (entry 18) completely eliminated pyocyanin production (99%). We explored the impact of chain length on the activity of the potent trifluoromethyl analog (entries 16–19), and found the five- and four-methylene linker to be most active (99% efficacy, entry 18 and 95% efficacy, entry 17).

Further studies confirmed that the pyridine nitrogen is important for activity, as its removal led to a compound with only 62% efficacy (entry 20), and an additional trifluoromethyl group failed to rescue activity (44%, entry 21). While the electronics at the 2-position are important, the substituent at that position also appears to be binding a pocket in the target protein because the methyl analog remained fairly active (80%, entry 22). Moving the trifluoromethyl group to the 3-position was not tolerated, leading to a compound with 15% efficacy (entry 23).

We next sought to re-optimize the tail group for the 4-amino-2-trifluoromethylpyridine head group (Table 4). Overall we found that many substitution patterns on the tail moiety were permitted. Repositioning of the bromide to the 2-position of the aryl tail group (94%, entry 1) was preferable to a move to the 4-position (88%, entry 2). Incorporation of other halides in the 3-position also furnished active compounds (entries 3–5). Efforts to reposition the fluoride around the ring led to similar but more pronounced trends than those observed in the bromide series (entries 6–7 vs. entries 1–2); the analog bearing substitution at the 4-position was the least active (54%, entry 7), and the 3-fluoro analog was superior overall (entry 5). The incorporation of additional fluoride substituents only led to decreased activity (entries 8–10).

Table 4.

Hybrid tail group optimization.

| Entry | Substrate | Efficacy (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

94 ± 4 |

| 2 |

|

88 ± 4 |

| 3 |

|

95 ± 3 |

| 4 |

|

101 ± 3 |

| 5 |

|

103 ± 3 |

| 6 |

|

78 ± 3 |

| 7 |

|

54 ± 4 |

| 8 |

|

49 ± 3 |

| 9 |

|

66 ± 4 |

| 10 |

|

21 ± 14 |

| 11 |

|

39 ± 36 |

| 12 |

|

0.48 ± 7 |

| 13 |

|

59 ± 3 |

| 14 |

|

81 ± 4 |

| 15 |

|

70 ± 7 |

| 16 |

|

95 ± 4 |

| 17 |

|

94 ± 4 |

| 18 |

|

96 ± 4 |

| 19 |

|

100 ± 4 |

| 20 |

|

97 ± 4 |

|

| ||

| ||

Substrates bearing other inductively withdrawing groups at the 3-position were less effective inhibitors (entries 11–13). A methyl group substituent was found to be effective (81%, entry 14), but less so than the analogous halides. Finally, incorporation of a hydroxyl group at the 3-position led to an analog with moderate activity (70%, entry 15), although enhanced potency was observed in the 2-hydroxy derivative (95%, entry 16).

We also examined the importance of the ether linkage between the aryl tail and the rest of the compound. Analogs that substituted the oxygen with a sulfur, carbon, or nitrogen retained activity (94%, entry 17, 96%, entry 18, and 100%, entry 19). Interestingly, an alkyne was also well tolerated in the linker (97%, entry 20).

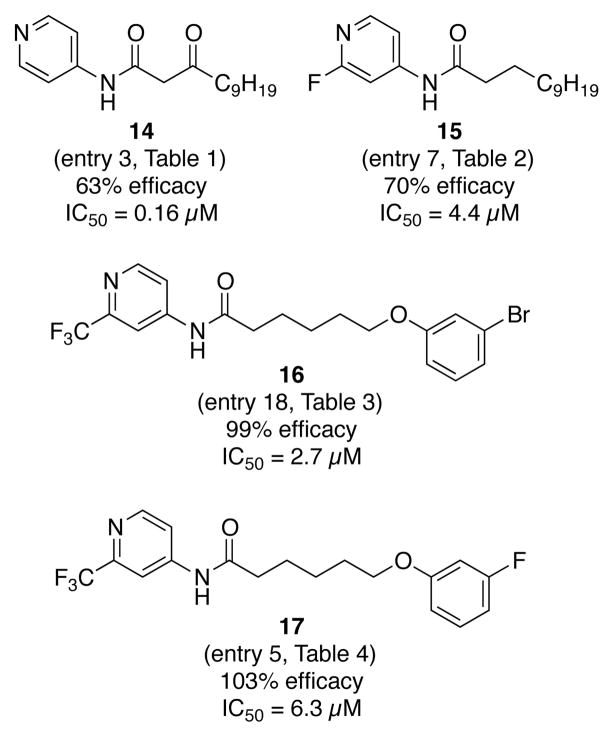

IC50 values were determined for top hits from each of the libraries (Fig. 5). Most of the inhibitors had low micromolar activities, while 14 was an order of magnitude more active. To ensure that the observed activity was not due to the alteration of the oxidation state of pyocyanin, cell-free culture fluids containing pyocyanin were incubated with the inhibitors. No changes in absorbance occurred over 17 hours (Supporting Information Fig. S1).38

Figure 5.

IC50 values of selected hits.

Finally, we investigated the biological target of the inhibitors. The small molecules were designed to be AHL analogs that bind and antagonize LasR and/or RhlR. The activity of the inhibitors was first investigated in a heterologous E. coli system, in which the LasR or RhlR transcription factor and target-gfp fusions were present on plasmids.22 Upon addition of an agonist, such as the native AHL, GFP is produced. None of the compounds acted as agonists for LasR or RhlR at 100 μM (Supporting Information Fig. S2).38 In the presence of the native AHL, an inhibitor will decrease the production of GFP. None of the compounds acted as antagonists for LasR or RhlR at 100 μM (Supporting Information Fig. S2).38 To further probe whether the compound bound LasR or RhlR, we performed competition assays with compound 16 (at 100 μM and 500 μM) and increasing amounts of the respective native AHL. The LasR or RhlR responses were identical following treatment with inhibitor and with the DMSO control (Supporting Information Fig. S3).38 We also explored anti-biofilm activity as an additional quorum-sensing-controlled output; inhibitor 16 had no effect on biofilm formation (Supporting Information Fig. S4).38 Despite having been designed to target the LasR and/or RhlR receptors of P. aeruginosa, clearly the compounds do not function by inhibiting either receptor. This result was initially surprising based on the design of the head groups to mimic AHL-binding and the overall structural similarity to our previously disclosed compound 1, which does influence LasR and RhlR signaling. Upon further inspection of the activity trends, the result is perhaps less surprising. The optimum length for thiolactone 1 is three-methylenes, whereas analogs of 1 with longer linkers showed significantly less activity. By contrast, the anti-pyocyanin compounds reported in the current study have an optimum four- or five-methylene linker. Perhaps these differences lead to the observed reduction in in vivo pyocyanin levels via a pathway independent of LasR/RhlR.

We used microarray analyses to define the effects of the inhibitor 16 in vivo. Wild-type P. aeruginosa PA14 was treated with hybrid 16 and compared to a DMSO-treated control culture. Evaluating changes greater than 2-fold, we found that 75 genes were down-regulated and 24 were up-regulated (Supporting Information Tables S1–S2).38 Among the genes down-regulated were those in the SoxR regulon. Pyocyanin acts as a terminal signal in P. aeruginosa that, through SoxR regulation, activates expression of the gene encoding the putative monooxygenase PA14_35160 as well as genes encoding transporters.39 Thus, decreased expression of the SoxR-controlled genes following treatment with 16 is consistent with reduced pyocyanin production (Table 5).

Table 5.

Changes in the SoxR regulon after treatment with 16.

| Gene Locus | Gene Name | Description | Fold down-regulated |

|---|---|---|---|

| PA14_35160 | hypothetical protein | 4.93 | |

| PA14_16310 | MFS permease | 3.27 | |

| PA14_09530 | mexH | RND efflux membrane fusion protein | 2.93 |

| PA14_09520 | mexI | RND efflux transporter | 2.84 |

| PA14_09540 | mexG | hypothetical protein | 2.68 |

| PA14_09500 | opmD | outer membrane protein | 2.50 |

Examination of the rest of the microarray data revealed that despite an elimination of pyocyanin production in culture, expression of the pyocyanin biosynthetic genes remained unchanged following treatment with hybrid 16. These results suggest a post-transcriptional mechanism of regulation of the virulence factor.38 In general, few genes in the quorum-sensing regulon were affected. Rather, the majority of genes with the largest-fold down-regulation upon addition of 16 were associated with the oxidative stress response (Table 6).40–42

Table 6.

Oxidative stress genes influenced by 16.

| Gene Locus | Gene Name | Description | Fold Down-Regulated |

|---|---|---|---|

| PA14_21530 | ankyrin domain-containing protein | 44.39 | |

| PA14_22320 | hypothetical protein | 35.99 | |

| PA14_01720 | ahpF | alkyl hydroperoxide reductase | 33.03 |

| PA14_53290 | trxB2 | thioredoxin reductase 2 | 27.79 |

| PA14_09150 | katA | catalase | 20.80 |

| PA14_03090 | hypothetical protein | 14.35 | |

| PA14_58040 | hypothetical protein | 5.67 | |

| PA14_51830 | DNA-binding stress protein | 5.60 | |

| PA14_61040 | katB | catalase | 4.15 |

| PA14_58030 | fumC | fumarate hydratase | 2.71 |

In an attempt to clarify the target of 16, we also performed microarrays using an inactive scaffold hoping to distinguish the key targets of 16. We used entry 12 in Table 4, which differs from active 16 only in that entry 12 possesses a nitrile moiety in place of the bromide of 16. The inactive control had almost no effect on transcript levels, with only three genes changing 2-fold or more (katA was up-regulated 2.2-fold, trxB2 was up-regulated 2.0-fold, while norC was down-regulated 2.0-fold, Supporting Information Tables S3–S4).38 Thus, no obvious target candidate for 16 could be identified from these microarray comparisons.

In addition to the population-dependent behaviors regulated by quorum sensing, P. aeruginosa detects and responds to environmental cues to adapt to its surroundings. The response to these cues is key to the pathogen’s ability to thrive in environments ranging from soil to hospital surfaces, and from hot tubs to plant and animal hosts.1–3 In addition to acting as a terminal signal in the quorum-sensing pathway, pyocyanin is also an important component that maintains P. aeruginosa’s redox balance, especially under low oxygen or anaerobic conditions.21 Pyocyanin also helps protect the bacterium from reactive oxygen species.43 It is thus reasonable that signaling pathways sensitive to environmental stimuli could also control pyocyanin production. Further work is needed to identify the molecular target of the pyocyanin inhibitors discovered here and to investigate their possible influence on the oxidative stress response.

Conclusions

We have developed chemically stable and potent inhibitors of pyocyanin production in wild-type P. aeruginosa. Work is underway to determine the specific targets and modes of action of the compounds. We are also investigating the potential antivirulence effects of the inhibitors, with the goal of making further advances to combat P. aeruginosa virulence.38

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Biological Assays

Pyocyanin assays, LasR and RhlR GFP assays, RNA extraction, and microarray analyses were performed as previously reported.22

Chemistry Materials and Methods

Unless otherwise stated, reactions were performed in flame-dried glassware fitted with rubber septa under a nitrogen atmosphere and were stirred with Teflon-coated magnetic stirring bars. Liquid reagents and solvents were transferred via syringe using standard Schlenk techniques. Reaction solvents were dried by passage over a column of activated alumina. All other solvents and reagents were used as received unless otherwise noted. Reaction temperatures above 23 °C refer to oil bath temperature, which was controlled by an OptiCHEM temperature modulator. Thin layer chromatography was performed using SiliCycle silica gel 60 F-254 precoated plates (0.25 mm) and visualized by UV irradiation and anisaldehyde or potassium permanganate stain. Sorbent standard silica gel (particle size 40–63 μm) was used for flash chromatography. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker Avance III (500 MHz for 1H; 125 MHz for 13C) spectrometer fitted with either a 1H-optimized TCI (H/C/N) cryoprobe or a 13C-optimized dual C/H cryoprobe or a Bruker NanoBay (300 MHz). Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in ppm relative to the residual solvent signal (δ = 7.26 for 1H NMR and δ = 77.0 for 13C NMR for CDCl3, δ = 3.31 for 1H NMR and δ = 49.0 for 13C NMR for CD3OD, δ = 2.05 for 1H NMR and δ = 29.8 for 13C NMR for acetone-d6). Data for 1H NMR spectra are reported as follows: chemical shift (multiplicity, coupling constants, number of hydrogens). Abbreviations are as follows: s (singlet), bs (broad singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), q (quartet), p (pentet), dd (doublet of doublets), ddd (doublet of doublet of doublets), dt (doublet of triplets), td (triplet of doublets), m (multiplet). High-resolution mass spectral analysis was performed using an Agilent 1200-series electrospray ionization – time-of-flight (ESI-TOF) mass spectrometer in the positive ESI mode. Analytical high-performance liquid chromatography was performed by Lotus Separations, LLC, using a Rainin HPLC with SD-1 pumps and a Dynamax UV-1 detector. All final compounds were determined to be of >95% purity by analysis of their characterization data.

General Procedures

Synthesis of β-keto amide compounds. General procedure A

To a flame-dried flask was added Meldrum’s acid (1 equiv) and CH2Cl2 (0.34 M). The reaction mixture was cooled to 0 °C, and pyridine (2 equiv) was added over 20 min. Decanoyl chloride (1 equiv) was then added dropwise. The reaction mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 2 h and was allowed to return to room temperature over 1 h. The reaction was diluted with CH2Cl2 and a 2 M HCl/ice mixture. After stirring for 10 min, the phases were separated. The organic phase was washed sequentially with 2 M HCl and brine, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated. The residue was dissolved in CH3CN (0.1 M) and the amino-heterocycle (1 equiv) was added. The reaction was heated to 65 °C for 4 h. The reaction mixture was then concentrated and the crude product was purified by column chromatography.

Synthesis of amide compounds I. General procedure B

The amino-heterocycle (1 equiv), CH2Cl2 (0.15 M), and Et3N (2 equiv) were combined in a flame-dried flask. The reaction mixture was cooled to 0°C, and dodecanoyl chloride (1 equiv) was added dropwise. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature over 3 h. The reaction was then quenched with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 solution. The layers were separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted 3x with CH2Cl2. The combined organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated. The crude product was purified by column chromatography.

Synthesis of amide compounds II. General procedure C

To a flame-dried flask were added the carboxylic acid (1.0 equiv), dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (1.1 equiv), dimethylaminopyridine (1.1 equiv), dodecylamine (1.0 equiv), and CH2Cl2 (0.40 M). After stirring at room temperature for 24 h, the reaction mixture was filtered through a Celite plug and concentrated. The crude product was purified by column chromatography.

Synthesis of 4-amino-2-trifluoromethylpyridine analogs. General procedure D

6-chloro-N-(2-(trifluoromethyl)pyridin-4-yl)hexanamide (1 equiv), anhydrous potassium iodide (12 equiv), anhydrous potassium carbonate (7.5 equiv), and the corresponding aryl nucleophile (3.8 equiv) were dissolved in isopropanol (0.68 M) in a vial. The vial was sealed, and the reaction mixture was heated to 100 °C behind a blast shield for at least 60 h, or until complete as monitored by TLC. After cooling, the reaction was quenched with water and extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic layer was washed sequentially with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (2x), 1 M HCl, and brine. The solution was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated. The crude product was purified by column chromatography.

3OC12-4-aminopyridine (14)

Prepared from 4-aminopyridine using general procedure A to furnish 14 in a 51% yield. HRMS (ESI-TOF) calculated for C17H27N2O2 [M+H]+: m/z 291.2073, found 291.2077; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.61 (s, 1H), 8.51 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 7.58–7.48 (m, 2H), 3.59 (s, 2H), 2.58 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.62 (p, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 1.44–1.15 (m, 12H), 0.87 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 208.0, 164.2, 150.8, 144.3, 113.9, 48.3, 44.3, 31.8, 29.3, 29.3, 29.2, 28.9, 23.3, 22.6, 14.1. >99% purity by HPLC analysis.

C12-4-amino-2-fluoropyridine (15)

Prepared from 4-amino-2-fluoropyridine using general procedure B to furnish 15 in a 45% yield. HRMS (ESI-TOF) calculated for C17H28FN2O [M+H]+: m/z 295.2186, found 295.2188; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.09 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 7.40–7.31 (m, 2H), 7.17 (dt, J = 5.7, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 2.40 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.72 (p, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 1.26 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 16H), 0.87 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.9, 164.8 (d, J = 236 Hz), 148.8 (d, J = 12 Hz), 148.1 (d, J = 17 Hz), 111.2 (d, J = 4 Hz), 98.6 (d, J = 43 Hz), 37.8, 31.9, 29.6, 29.6, 29.4, 29.3, 29.3, 29.1, 25.1, 22.7, 14.1. >99% purity by HPLC analysis.

4-amino-2-trifluoromethylpyridine-C6-3-bromophenoxyhybrid (16)

Prepared from 4-amino-2-trifluoromethylpyridine and 6-(3-bromophenoxy)hexanoic acid22 using general procedure C to furnish 16 in a 42% yield. HRMS (ESI-TOF) calculated for C18H19BrF3N2O2 [M+H]+: m/z 431.0582, found 431.0571; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.60 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (dd, J = 5.5, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (s, 1H), 7.13 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.10–6.99 (m, 2H), 6.81 (ddd, J = 8.2, 2.5, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 3.95 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 2.46 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 1.89–1.74 (m, 4H), 1.63–1.50 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.8, 159.7, 151.0, 149.3 (q, J = 35 Hz), 146.1, 130.6, 124.7–117.9 (m), 123.7, 122.8, 117.6, 115.3, 113.4, 110.3 (q, J = 3 Hz), 67.7, 37.5, 28.8, 25.6, 24.7. >99% purity by HPLC analysis.

4-amino-2-trifluoromethylpyridine-C6-3-fluorophenoxyhybrid (17)

Prepared from 3-fluorophenol using general procedure D to furnish 17 in a 40% yield. HRMS (ESI-TOF) calculated for C18H19F4N2O2 [M+H]+: m/z 371.1383, found is 371.1367; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.59 (s, 1H), 7.92 (s, 1H), 7.77 (s, 1H), 7.73–7.65 (m, 1H), 7.24–7.16 (m, 1H), 6.68 – 6.61 (m, 2H), 6.58 (dt, J = 11.0, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.94 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 2.46 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 1.86–1.76 (m, 4H), 1.60–1.51 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.9, 163.6 (d, J = 245 Hz), 160.3 (d, J = 11 Hz), 150.9, 149.3 (q, J = 35 Hz), 146.3, 130.2 (d, J = 10 Hz), 121.3 (q, J = 274 Hz), 115.4, 110.5–110.1 (m, 2C), 107.4 (d, J = 21 Hz), 102.1 (d, J = 25 Hz), 67.7, 37.5, 28.8, 25.7, 24.7. >99% purity by HPLC analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Lark Perez and Ioannis Mountziaris for early AutoDock studies, and Christina Kraml [Lotus Separations LLC] for HPLC analysis. LCM was supported by Air Force Office of Scientific Research (Grant No. FA9550-12-1-0367). ZZ was supported by a Merck Undergraduate Science Endeavor (MUSE) Grant. AS was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Postdoctoral Fellowship F32AI095002. BLB was supported by Howard Hughes Medical Institute, NIH Grant 5R01GM065859 and National Science Foundation (NSF) Grant MCB-0343821.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information. Supplemental figures and tables can be found in the Supporting Information, as well as experimental procedures and characterization for the rest of the compounds, including 1H spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Mathee K, Narasimhan G, Valdes C, Qiu X, Matewish JM, Koehrsen M, Rokas A, Yandava CN, Engels R, Zeng E, Olavarietta R, Doud M, Smith RS, Montgomery P, White JR, Godfrey PA, Kodira C, Birren B, Galagan JE, Lory S. Dynamics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa genome evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2008;105:3100–3105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711982105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silby MW, Winstanley C, Godfrey SA, Levy SB, Jackson RW. Pseudomonas genomes: diverse and adaptable. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2011;35:652–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gellatly SL, Hancock RE. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: new insights into pathogenesis and host defenses. Pathog Dis. 2013;67:159–173. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. Antimicrobrial resistance: global report on surveillance 2014. WHO Press; Geneva: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rasko DA, Sperandio V. Anti-virulence strategies to combat bacteria-mediated disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:117–128. doi: 10.1038/nrd3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen RC, Popat R, Diggle SP, Brown SP. Targeting virulence: can we make evolution-proof drugs? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:300–308. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rutherford ST, Bassler BL. Bacterial quorum sensing: its role in virulence and possibilities for its control. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a012427. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ng WL, Bassler BL. Bacterial quorum-sensing network architectures. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:197–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams P, Cámara M. Quorum sensing and environmental adaptation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a tale of regulatory networks and multifunctional signal molecules. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;12:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jimenez PN, Koch G, Thompson JA, Xavier KB, Cool RH, Quax WJ. The multiple signaling systems regulating virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2012;76:46–65. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.05007-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuster M, Lostroh CP, Ogi T, Greenberg EP. Identification, timing, and signal specificity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-controlled genes: a transcriptome analysis. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:2066–2079. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.7.2066-2079.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearson JP, Gray KM, Passador L, Tucker KD, Eberhard A, Iglewski BH, Greenberg EP. Structure of the autoinducer required for expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 1994;91:197–201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gambello MJ, Iglewski BH. Cloning and characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasR gene, a transcriptional activator of elastase expression. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3000–3009. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.3000-3009.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner VE, Bushnell D, Passador L, Brooks AI, Iglewski BH. Microarray analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing regulons: effects of growth phase and environment. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:2080–2095. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.7.2080-2095.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilbert KB, Kim TH, Gupta R, Greenberg EP, Schuster M. Global position analysis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing transcription factor LasR. Mol Microbiol. 2009;73:1072–1085. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06832.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Latifi A, Winson MK, Foglino M, Bycroft BW, Stewart GS, Lazdunski A, Williams P. Multiple homologues of LuxR and LuxI control expression of virulence determinants and secondary metabolites through quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:333–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17020333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearson JP, Passador L, Iglewski BH, Greenberg EP. A second N-acylhomoserine lactone signal produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 1995;92:1490–1494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ochsner UA, Koch AK, Fiechter A, Reiser J. Isolation and characterization of a regulatory gene affecting rhamnolipid biosurfactant synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2044–2054. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.2044-2054.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pesci EC, Pearson JP, Seed PC, Iglewski BH. Regulation of las and rhl quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3127–3132. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3127-3132.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brint JM, Ohman DE. Synthesis of multiple exoproducts in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is under the control of RhlR-RhlI, another set of regulators in strain PAO1 with homology to the autoinducer-responsive LuxR-LuxI family. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:7155–7163. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7155-7163.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glasser NR, Kern SE, Newman DK. Phenazine redox cycling enhances anaerobic survival in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by facilitating generation of ATP and a proton-motive force. Mol Microbiol. 2014;92:399–412. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Loughlin CT, Miller LC, Siryaporn A, Drescher K, Semmelhack MF, Bassler BL. A quorum-sensing inhibitor blocks Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence and biofilm formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2013;110:17981–17986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316981110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galloway WR, Hodgkinson JT, Bowden SD, Welch M, Spring DR. Quorum sensing in Gram-negative bacteria: small-molecule modulation of AHL and AI-2 quorum sensing pathways. Chem Rev. 2011;111:28–67. doi: 10.1021/cr100109t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu J, Winans SC. The quorum-sensing transcriptional regulator TraR requires its cognate signaling ligand for protein folding, protease resistance, and dimerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2001;98:1507–1512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu J, Winans SC. Autoinducer binding by the quorum-sensing regulator TraR increases affinity for target promoters in vitro and decreases TraR turnover rates in whole cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 1999;96:4832–4837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen G, Swem LR, Swem DL, Stauff DL, O’Loughlin CT, Jeffrey PD, Bassler BL, Hughson FM. A strategy for antagonizing quorum sensing. Mol Cell. 2011;42:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen F, Gao Y, Chen X, Yu Z, Li X. Quorum quenching enzymes and their application in degrading signal molecules to block quorum sensing-dependent infection. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:17477–17500. doi: 10.3390/ijms140917477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hong KW, Koh CL, Sam CK, Yin WF, Chan KG. Quorum quenching revisited--from signal decays to signalling confusion. Sensors (Basel) 2012;12:4661–4696. doi: 10.3390/s120404661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glansdorp FG, Thomas GL, Lee JK, Dutton JM, Salmond GP, Welch M, Spring DR. Synthesis and stability of small molecule probes for Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing modulation. Org Biomol Chem. 2004;2:3329–3336. doi: 10.1039/B412802H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McInnis CE, Blackwell HE. Thiolactone modulators of quorum sensing revealed through library design and screening. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:4820–4828. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.06.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith KM, Bu Y, Suga H. Library screening for synthetic agonists and antagonists of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa autoinducer. Chem Biol. 2003;10:563–571. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(03)00107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hodgkinson JT, Galloway WR, Wright M, Mati IK, Nicholson RL, Welch M, Spring DR. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of non-natural modulators of quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Org Biomol Chem. 2012;10:6032–6044. doi: 10.1039/c2ob25198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morkunas B, Galloway WR, Wright M, Ibbeson BM, Hodgkinson JT, O’Connell KM, Bartolucci N, Della Valle M, Welch M, Spring DR. Inhibition of the production of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence factor pyocyanin in wild-type cells by quorum sensing autoinducer-mimics. Org Biomol Chem. 2012;10:8452–8464. doi: 10.1039/c2ob26501j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bottomley MJ, Muraglia E, Bazzo R, Carfi A. Molecular insights into quorum sensing in the human pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa from the structure of the virulence regulator LasR bound to its autoinducer. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13592–13600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700556200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zou Y, Nair SK. Molecular basis for the recognition of structurally distinct autoinducer mimics by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa LasR quorum-sensing signaling receptor. Chem Biol. 2009;16:961–970. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McInnis CE, Blackwell HE. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of abiotic, non-lactone modulators of LuxR-type quorum sensing. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:4812–4819. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.06.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.See the supporting information.

- 39.Dietrich LE, Price-Whelan A, Petersen A, Whiteley M, Newman DK. The phenazine pyocyanin is a terminal signalling factor in the quorum sensing network of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:1308–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palma M, DeLuca D, Worgall S, Quadri LE. Transcriptome analysis of the response of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to hydrogen peroxide. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:248–252. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.1.248-252.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang W, Small DA, Toghrol F, Bentley WE. Microarray analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa reveals induction of pyocin genes in response to hydrogen peroxide. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:115. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei Q, Minh PN, Dotsch A, Hildebrand F, Panmanee W, Elfarash A, Schulz S, Plaisance S, Charlier D, Hassett D, Haussler S, Cornelis P. Global regulation of gene expression by OxyR in an important human opportunistic pathogen. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:4320–4333. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vinckx T, Wei Q, Matthijs S, Cornelis P. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa oxidative stress regulator OxyR influences production of pyocyanin and rhamnolipids: protective role of pyocyanin. Microbiology. 2010;156:678–686. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.031971-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.