Abstract

Hysteresis loops are phenomena that sometimes are encountered in the analysis of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic relationships spanning from pre-clinical to clinical studies. When hysteresis occurs it provides insight into the complexity of drug action and disposition that can be encountered. Hysteresis loops suggest that the relationship between drug concentration and the effect being measured is not a simple direct relationship, but may have an inherent time delay and disequilibrium, which may be the result of metabolites, the consequence of changes in pharmacodynamics or the use of a non-specific assay or may involve an indirect relationship. Counter-clockwise hysteresis has been generally defined as the process in which effect can increase with time for a given drug concentration, while in the case of clockwise hysteresis the measured effect decreases with time for a given drug concentration. Hysteresis loops can occur as a consequence of a number of different pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic mechanisms including tolerance, distributional delay, feedback regulation, input and output rate changes, agonistic or antagonistic active metabolites, uptake into active site, slow receptor kinetics, delayed or modified activity, time-dependent protein binding and the use of racemic drugs among other factors. In this review, each of these various causes of hysteresis loops are discussed, with incorporation of relevant examples of drugs demonstrating these relationships for illustrative purposes. Furthermore, the effect that pharmaceutical formulation has on the occurrence and potential change in direction of the hysteresis loop, and the major pharmacokinetic / pharmacodynamic modeling approaches utilized to collapse and model hysteresis are detailed.

INTRODUCTION

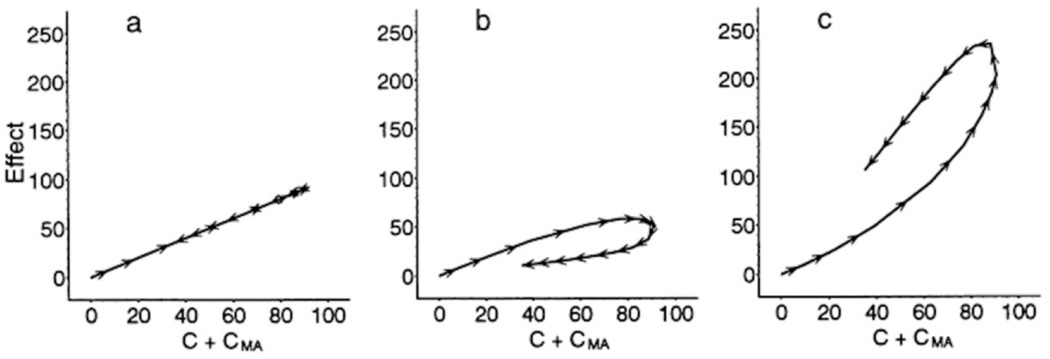

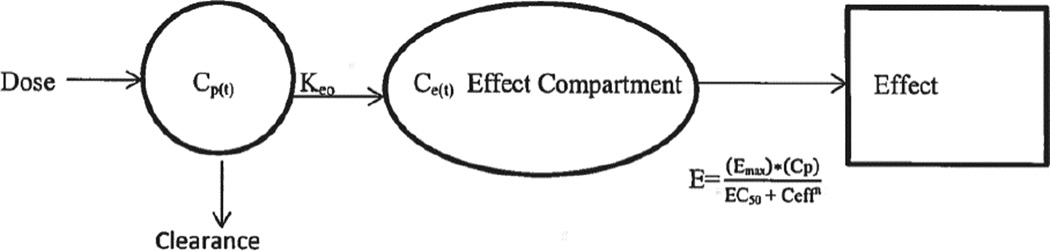

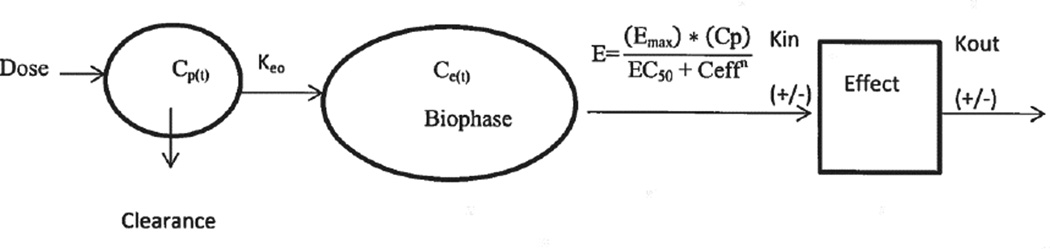

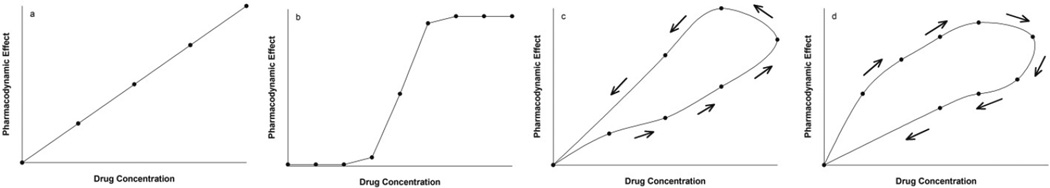

A central tenet of clinical pharmacotherapeutics is that there often exists a relationship between drug concentration and pharmacological and toxicological effects for drugs. The most common pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) models assume that plasma concentration is in equilibrium and proportional with the effect site (biophase) concentration. In its simplest form a plasma drug concentration versus effect graph demonstrates a direct linear relationship between the two variables where effect is directly proportional to drug concentrations at the active site and this relationship is independent of time [1] (Figure 1a).Where equation 1 is:

| (1) |

E is the effect, C is the drug concentration and S is the slope parameter. This linear function model does not predict a maximum pharmacological effect (Emax). The relationship between drug concentration and pharmacological effect more often follows a sigmoidal Emax model (Hill equation) (Figure 1b). This simple mathematical relationship is based on receptor theory that defines the drug concentration effect relationship with two parameters Emax and EC50 (the concentration producing 50% of the maximum effect). It allows for differences in the shape of this relationship, where n is the number of molecules combining with each receptor molecule that affects the shape of the curve. The relationship between drug concentration at the receptor and the response is defined using equation 2.

Figure 1.

(a) Representation of a linear relationship between plasma concentration of a drug and measured pharmacological effect (b) Representation of a Sigmoidal Emax model relationship between plasma concentration of a drug and measured pharmacological effect (c) Representation of counter-clockwise hysteresis between plasma concentration and measured pharmacological effect (d) Representation of clockwise hysteresis between plasma concentration and measured pharmacological effect.

| (2) |

E is the observed effect, Emax is the theoretical maximal effect that can be attained, C is the concentration, EC50 is the C value that produces an effect equivalent to 50% of the theoretical maximal effect and n is a slope factor parameter that determines the steepness of the curve. The time courses of drug effect and concentrations may not be completely superimposable. Time-dependent concentration-effect relationships exist with a time lag present between measurable effect and measurable concentration. In these cases, when pharmacodynamics and drug concentration data are connected in time series at a later point compared with a previous time point there is a discordance in the plasma concentration versus effect relationship with respect to time. Hence, the magnitude of pharmacological effect either increases or decreases at any given plasma drug concentration. The term “hysteresis” has been utilized to describe this time lag. The term “hysteresis” is derived from the Greek husterēsis or husteros meaning ‘shortcoming, to come late or to come behind’. Hysteresis is the dependence of a system on both its current and past environments. Figure 1c and d present the graphical evidence of a temporal relationship of dependence between the pharmacological effect and the drug plasma concentration. As the data modeling field in pharmaceutical science examining the concentration versus effect relationships and simulations has grown, there has been some debate regarding the terminology used to describe these phenomena when encountered. It has been suggested that instead of using the term clockwise hysteresis, the moniker “proteresis” should be employed. “Proteresis” is a term also derived from the Greek language with proteros meaning ‘former, before or to mark an earlier event’. Similarly, instead of stating that a “counter-clockwise” or “anti-clockwise” hysteresis is present it was proposed to simply state the vernacular of ‘hysteresis’ to avoid redundancy [2]. However, the term ‘proteresis’ has not become the conventional lexicon and most studies in the literature still utilize the appellatives ‘clockwise’ or ‘counter-clockwise’ hysteresis. For consistency and clarity in this review clockwise hysteresis will be used instead of proteresis, and counter-clockwise hysteresis instead of simply hysteresis or anti-clockwise hysteresis.

In the counter-clockwise scenario (Figure 1 c) there is often non-instantaneous distribution of a drug to the effect site (biophase), as the drug appearance is delayed into the pharmacodynamic (PD) effect site at a slower rate than that in which it appears in plasma, this temporal delay in delivery results in a mismatch between declining concentrations and the response [3, 4]. When the biophase is not in the central compartment, it exhibits a counter-clockwise hysteresis loop when followed over time (Figure 1c). In this instance, there is a small effect at a given drug concentration; however, after some time has passed the same drug concentration gives rise to a greater measured effect than expected. Thus, the same drug concentration produces two different magnitudes of pharmacological effects depending on the temporal sequence in which the effect is measured. Counter-clockwise hysteresis has been generally defined as the process in which effect increases with time for a given drug concentration [5]. These phenomena can be caused by uptake into an active site, cascade activity, active metabolites or sensitization (Table 1) [5].

Table 1.

Mechanistic Explanations for Hysteresis

| Counter-clockwise Hysteresis | Clockwise Hysteresis |

|---|---|

| Sensitization (up regulation of receptors) | Tolerance (down regulation “desensitation” of receptors) |

| Input rate | Input rate |

| Distribution delay into the site of Effect | Disequilibrium between arterial and venous concentrations |

| Active agonist metabolite | Active antagonistic metabolite |

| Indirect effect(positive input or negative output) | Indirect effect (negative input or positive output) |

| Slow receptor kinetics | Feedback regulation |

| Time dependent protein binding | Time dependent protein binding |

| Racemic drugs and non-stereospecific assays | Racemic drugs and non-stereospecific assays |

In the opposite scenario a hysteresis loop may also occur where a clockwise hysteresis loop is evident, for example if tolerance is developed to a drug such as an opioid (Figure 1d). Here it can be seen that the same plasma concentration has a greater effect early on in temporal sequence and that after some time the effect diminishes at the same plasma concentration. In the case of clockwise hysteresis the measured effect decreases with time. These phenomena can be mechanistically induced by active antagonistic metabolites, tolerance, learning effects, or feed-back regulation etc. (Table 1) [5].

An analysis of the pharmaceutical literature using PubMed, EMBASE and Google Scholar searches indicates that there are many plausible mechanistic proposed reasons for explaining the findings of hysteresis loops in drug concentration versus effect plots (Tables 1–3). Situations that may lead to a clockwise hysteresis are the development of tolerance to a drug, antagonistic metabolites that are formed as the drug is metabolized, down-regulation of receptors and feedback regulation [6]. Some potential causes for counter-clockwise-hysteresis include distribution delay between the plasma and effect site, response delay, sensitization of receptors, the formation and subsequent accumulation of active metabolites through drug metabolism as well as up regulation of receptors after ongoing exposure [6, 7]. Once this type of hysteresis loop relationship has been discovered further mathematical modeling, such as the effect compartmental modeling, or one of its many modifications such as indirect modeling, can be applied to the data to take into account lag times, formation of active metabolites or multiple receptor sites in order to mechanistically define and simplify the concentration-effect relationship [1].

Table 3.

Clockwise Hysteresis

| Drug name | Drug Class (Indication) |

Population / species studied (Comorbidities) |

Route of Administration |

Proposed mechanism(s) |

Effect(s) measured |

Site of drug concentration measure |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alprazolam | Benzodiazepine | 21 humans (healthy) | 10 mg SR po | Tolerance | Mean percentage of decrement in Digit-symbol substitution test scores (sedation scores) | Venous blood samples from antecubital vein Mean alprazolam concentration | [80] |

| Alprazolam | Benzodiazepine | 24 humans (healthy) | 2 mg po (two single doses 15 days apart) | Tolerance | Relative B-1 activity (%), relative alpha activity (%), total number of responses, correct number of responses, activity (mm), drowsiness (mm) | Alprazolam plasma concentration (ng/ml) | [81] |

| Amitriptyline | Tricyclic anti-depressant | 24 humans (healthy) | 75 mg po controlled drug delivery or IR tablets | Tolerance and distributional characteristics | Change in dry mouth from baseline (VAS), change in drowsiness from baseline (VAS) | Amitriptyline plasma concentration (ng/mL) | [82] |

| (+/−) Apomorphine | Non-selective Dopamine Agonist | 10 humans (advanced Parkinson's disease with end of dose fluctuations) | 0.5,1,2,4 mg subcut | Tolerance Redistribution from effect site | CURS (Columbia University Rating Scale) | Apomorphine (pMol/ml) | [83] |

| (+/−) Atenolol | Beta-1 Selective Beta-Blocker | 10 rats | Sustained release pellets 16mg/kg po single dose | Tolerance induced by desensitization or production of regulatory substances | Change in Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | Atenolol concentration (µg/mL) | [14]* |

| Befloxatone | Selective monoamine oxidase A inhibitor | 12 humans (healthy) | 5 mg capsules bid po or 10 mg capsules once daily po | Compartment effect or an indirect response | % of DHPG decrease from baseline | Befloxatone concentration (ng/ml) | [84] |

| Bumetanide | Loop Diuretic | 3 humans (healthy) | 1mg SR capsules po | Tolerance | Urine flow rate (ml/hr) | Plasma concentration of bumetanide (ng/ml), urinary excretion rate of bumetanide (µg/h) | [20]* |

| Bumetanide | Loop Diuretic | 3 humans (healthy) | 1 mg IR tablet po | Tolerance | Urine flow rate (ml/h) | Urinary excretion rate of bumetanide (µg/h) | [20]* |

| Cocaine | Anesthetic/Drug of abuse | 7 humans | Smoked doses (10, 20, and 40 mg) | Tolerance (acute) | Mean change in systolic and diastolic pressure (mmHg) | Plasma cocaine concentration (ng/ml) | [299]* |

| Cocaine | Drug of abuse | 9 humans (healthy) | Smoked dose (12.5, 25, and 50 mg) and i.v. doses (8, 16, 32 mg) | Rapid distribution of drug to the brain | Mean change in systolic and diastolic pressure (BPM) and ratings of stimulated, high or drug liking | Venous plasma cocaine concentration (ng/ml) | [300]* |

| Cyclohexylamine | Sympathomimetic amine | Rats | 30 or 60 mg/kg iv infused over 20 min or 30, 60, or 120 mg/kg infused over 40 min | Tolerance (acute) | Mean Arterial Blood Pressure (mmHg) | Plasma Cyclohexylamine (µg/ml) | [323] |

| Cyclohexylamine | Sympathomimetic amine | Humans | 5 mg/kg po single dose | Tolerance | Mean Arterial Blood Pressure (mmHg) | Plasma Cyclohexylamine (µg/ml) | [324] |

| D-amphetamine | Stimulant | 22 rats | 1.5 mg/kg D-amfetamine base IR | None described | Locomotor activity (min/15 min interval) | Dopamine concentration in the striatum (% of baseline) | [28]* |

| Diazepam | Benzodiazepine | 17 humans (healthy) | 0.28 mg/kg | Tolerance | Adjusted subcritical tracking (rms-cm) Adjusted digit symbol substitution (sec) | Diazepam plasma level × free fraction (ng/mL) | [85]* |

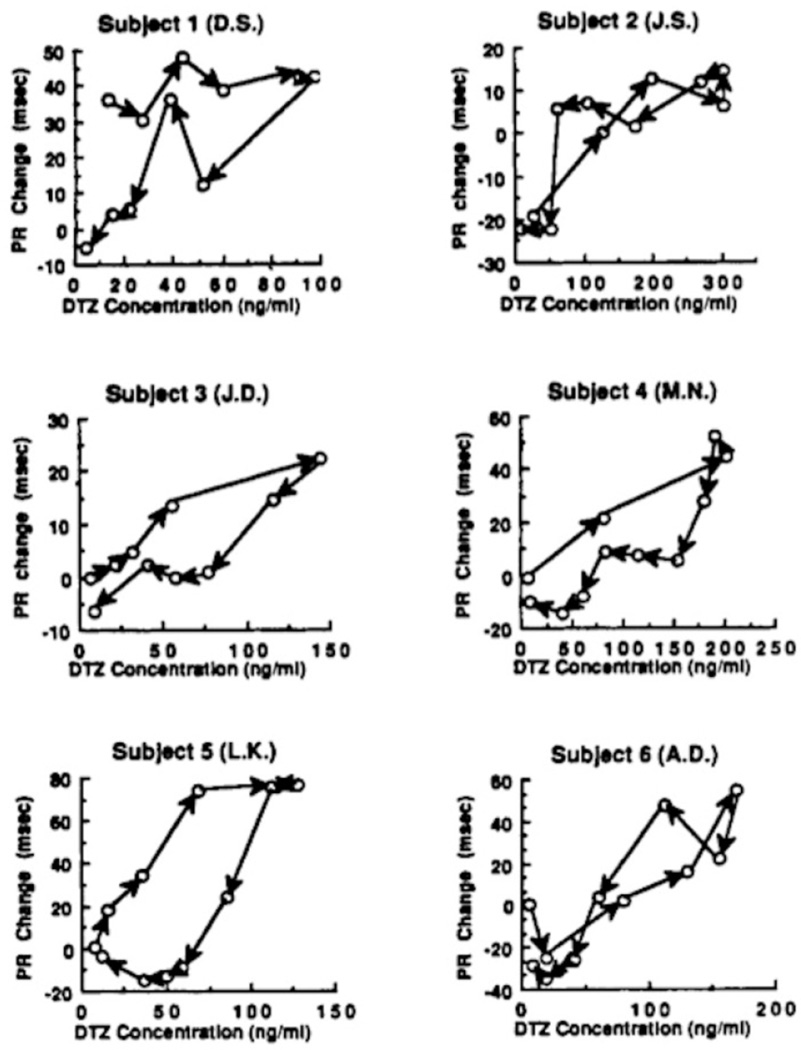

| Diltiazem | Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker | 6 humans (healthy) | 120 mg po single dose (2×60 mg tablets) | Tolerance | PR change (msec) | Diltiazem concentration (ng/ml) | [86] |

| Diltiazem | Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker | 20 humans (healthy) | 180 mg SR capsule with wax matrix 180 mg SR tablet | Tolerance | Changes in PQ interval (% of baseline) | Diltiazem plasma concentration (ng/ml) | [87] |

| Distigmine Bromide | Long acting acetyl-cholinesterase inhibitor | Rats | 0.3, 1, 3 mg/kg po (single dose) | Time lag between arrival of distigmine at the site and the onset of its inhibitory effect. | AChE activity (%) | Plasma Concentration of distigmine (ng/ml) | [88] |

| Fentanyl | Opioid analgesic | Rats | 15 µg/kg Nasal (pressurized olfactory delivery device) | Tolerance | Analgesic effect (%MPE) | Fentanyl (ng/ml) | [57]* |

| Furosemide | Loop diuretic | 26 humans (healthy) | 60 mg CR po (two different formulations) | Tolerance | Diuresis (mL/min) | Furosemide excretion rate (µg/min) | [38]* |

| Furosemide | Loop diuretic | 8 humans (healthy) | 10 mg iv infusion over 30, 100 and 300 minutes | Tolerance | Diuresis (mL/min) and Natiuresis (mmol/min) | Furosemide excretion rate (µg/min) | [41]* |

| Furosemide | Loop diuretic | 4 humans (healthy) | 40 mg SR tablet po | Tolerance | Diuretic rate (ml/h) | Excretion rate of furosemide (mg/h) | [39]* |

| Furosemide | Loop diuretic | 11 humans, Middle Eastern Arabs (healthy) 12 humans, Asian (healthy) | 40 mg tab po single dose | Tolerance | Chloride, sodium, calcium, magnesium and potassium excretion rates | Furosemide excretion rate (µg/hr) | [40]* |

| Furosemide | Loop diuretic | 8 humans (healthy) | 40 mg iv after breakfast 40 mg tablet po after breakfast | Tolerance | Urine flow rate (mL/min) | Furosemide excretion rate (µg/min) | [89] |

| Glutamate-oxaloacetate transaminase (GOT) Glutamate-pyruvate transaminase (GPT) enzymes | Enzymes that metabolize glutamate | 46 rats | Single IV bolus injections of 0.03 or 0.06 mg/kg GOT 0.6 or 1.2 mg/kg GPT | None described | Blood glutamate (µM) | Serum GOT or GPT (mg/L) | [90] |

| Heparin | Anticoagulant | 9 humans (healthy) | 2000 IU continuous infusion over 40 min | Tolerance - may be caused by depletion of endothelial TFPI sources | Plasma concentration of TFPI (free and total) (ng ml−1) TFPI production rate (µg min−1) | Anti-IIa activity (U ml−1), a measure of heparin concentration | [91] |

| (+/−) Irbesartan | Angiotensin II receptor blocker | 24 humans (mild to moderate hypertension) | 300 mg po once daily for 4 weeks | Central-effect compartment Receptor antagonism | Seated diastolic blood pressure | Mean irbesartan concentration (ng/ml) | [92]* |

| (+/−) Meperidine | Opioid analgesic | Sheep | 100 mg iv dose over 1 second | Tolerance | Contractility (% reduction) | Concentrations of meperidine in myocardium and coronary sinus blood (mg/L) | [53]* |

| (+/−) Methylphenidate | Central Nervous System Stimulant | 4 rats | 2, 5, 10 mg/kg iv (three doses) | Tolerance or Desensitization | Dopamine ratio to basal | Methylphenidate concentration in dialysate (ng/ml) | [93] |

| Metolazone | Thiazide-related diuretic | 5 humans (renal transplant patients) 5 humans (creatinine clearance | 5 mg | Tolerance to diuretic effect | Sodium Excretion rate (meq/min) | Urinary metolazone excretion rate (ng/min) | [94] |

| (+/−) Morphine | Opioid analgesic | Rats | 2.5 mg/kg Nasal (pressurized olfactory delivery device) | Tolerance | Analgesic effect (%MPE) | Morphine (ng/ml) | [57]* |

| (+/−) Morphine | Opioid analgesic | 280 rats | 15 mg/kg through intragastric administration (single dose) | Tolerance due to drug induced desensitization of receptors or counter regulatory substances | % MPE on TPR (thermal pain response) | Concentration of blood morphine (µg/L), and concentration of CSF morphine (µg/L), both conjugated and unconjugated | [59]* |

| Nefopam | Non-opioid analgesic | 24 humans (healthy) | 20 mg po and iv (single doses) | None described | Visual analog scale drowsy (mm) | Nefopam plasma concentration (nM), desmethyl-nefopam plasma concentration (nM) | [95] |

| (+/−) Nicotine | Stimulant | 8 humans (healthy) | 2.5 µg/kg/min iv for 30 min, 120 min, and 210 min | Tolerance | Heart rate (BPM) | Blood nicotine concentration (ng/ml) | [315] |

| Pancuronium | Neuromuscular blocking agent | 5 humans (healthy) | 4 mg iv | Effect compartment | % twitch depression | Pancuronium concentration (nmol/L) | [316]* |

| Piritramide | Synthetic opioid analgesic | 24 humans (post-abdominal surgery) | 7 µg kg−1 min−1 up to maximum 0.2 mg/kg | Equilibration delay of piritramide between plasma concentration and effect site | Pain intensity VAS measured (0–100) Pain intensity VAS predicted (0–100) | Piritramide concentration measured (µg/L) Piritramide concentration measured (µg/L) | [96] |

| Propofol | General Anesthetic | 18 rats | 150 mg/kg·h | Delay of equilibrium of blood and effect site | Electroenceph alographic amplitude | Propofol blood concentration | [97]* |

| Propofol | General Anesthetic | Rats | 30 mg/kg in 5 min iv bolus infusion and 150 mg/kg iv continuous infusion (5 hrs) -both doses tested as 1% in Intralipid® 10%, 1% in Lipofundin® and 6% in Lipofundin® emulsions | Hypothetical multiple compartments | EEG effects | Propofol blood concentration (µg/ml) | [98]* |

| (+/−) Propranolol | Beta-blocker | 8 humans (detoxified alcoholics) | 80 mg po | Acute tolerance | Degree of beta-blockade, changes in heart rate (%) | Propranolol plasma concentration (ng/ml) | [317]* |

| Remifentanil | Synthetic opioid analgesic | 10 humans (healthy) | 3 µg/kg/min for 10 minutes | Equilibration between arterial drug concentration and the effect site occurs more rapidly than equilibrium between arterial drug concentration and venous drug concentration | Spectral edge (Hz) (opioid effect) | Venous remifentanil concentration (ng/mL) | [69]* |

| Scopolamine | Anticholinergic | 90 humans (healthy) | 0.5 mg iv infusion over 15 min. | Delayed distribution to effect compartment | Saccadic peak velocity (°s−1) VAS alertness (mm) | Plasma scopolamine concentration (pg ml−1) | [99] |

| Sodium dichloroacetate | Acetic acid analogue | 37 humans (healthy) | 30 mg/kg, 60 mg/kg or 100 mg/kg iv infusions over 30 min | 1) Inhibition of PDH-kinase could be reversible at low concentrations of DCA, becoming irreversible at high concentration 2) PDH-kinase binding of DCA may be more rapid than dissociation 3) There may be Substantial redundancy in the amounts of DCA bound compared with that needed for maximal effect, or 4) A combination of these fairly common pharmacological phenomena | Serum lactate concentration (mM) | Serum Sodium dichloroacetate concentration (µg/mL) | [100] |

| Spiraprilat | Active metabolite of spirapril (ACEI) | 8 humans (CHF) | 6 mg po of spirapril | None described | Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (mmHg) | Spiraprilat plasma concentration (ng/ml) | [330] |

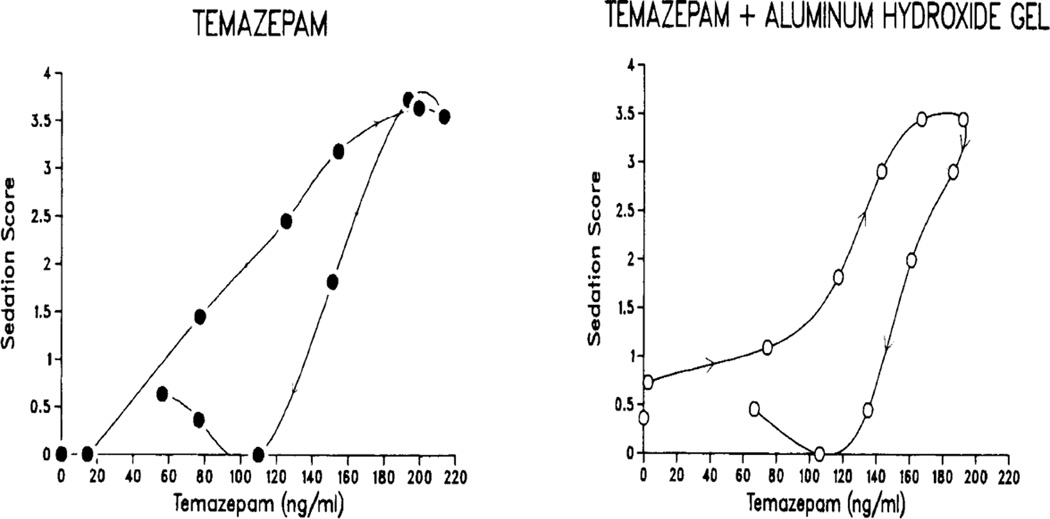

| (+/−) Temazepam | Benzodiazepine | 11 humans (end-stage renal disease) | 30 mg capsule po (two single doses) | Tolerance- discrepancy between plasma t1/2 and binding affinity | Sedation score NRSS Nurse rated sedation score (range 0- wide awake to 4-sleeping soundly, not awakened by blood sampling) | Temazepam concentration (ng/ml) | [101] |

| (+/−) Zopiclone | Short-acting hypnotic | 10 humans (healthy) | 7.5 mg po single dose | Tolerance or pseudo-tolerance | Saccadic peak velocity and Digital symbol substitution test (sedation scores) | Blood sample from forearm vein zopiclone (ng/ml) | [102] |

+/− Indicates Racemic Drug with Enantiomers

Indicates Drug listed in both Table 2 and 3

As hysteresis loops become readily evident during attempts to correlate the pharmacokinetic (PK) measurement [concentration (C)] of a drug with its measured PD measurement [effect (E)], an accurate determination of the PD measurement is critical.[8] In general, most of the clinical pharmacology study designs include in vivo PK and in vivo PD endpoint measurements; however, in the case of antibiotics or immunosuppressants it is common to have in vivo non-steady state dosing of drug, and the sampled matrix is used to determine in vitro PD effect, which can make the interpretation of hysteresis more straightforward. However, in early stages of drug discovery/development analytical assays are sometimes incapable of differentiating parent drug from its metabolite(s) and therefore would not be able to account for the presence/degree of in vivo pharmacological active metabolite(s) [8]. From the pharmacological and mechanistic point of view, counter-clockwise and clockwise hysteresis loops are a phenomenon that occurs under specific conditions, and the amount, activity and potency of parent and metabolite ratio is a key concept in the development and direction of a determined hysteresis.

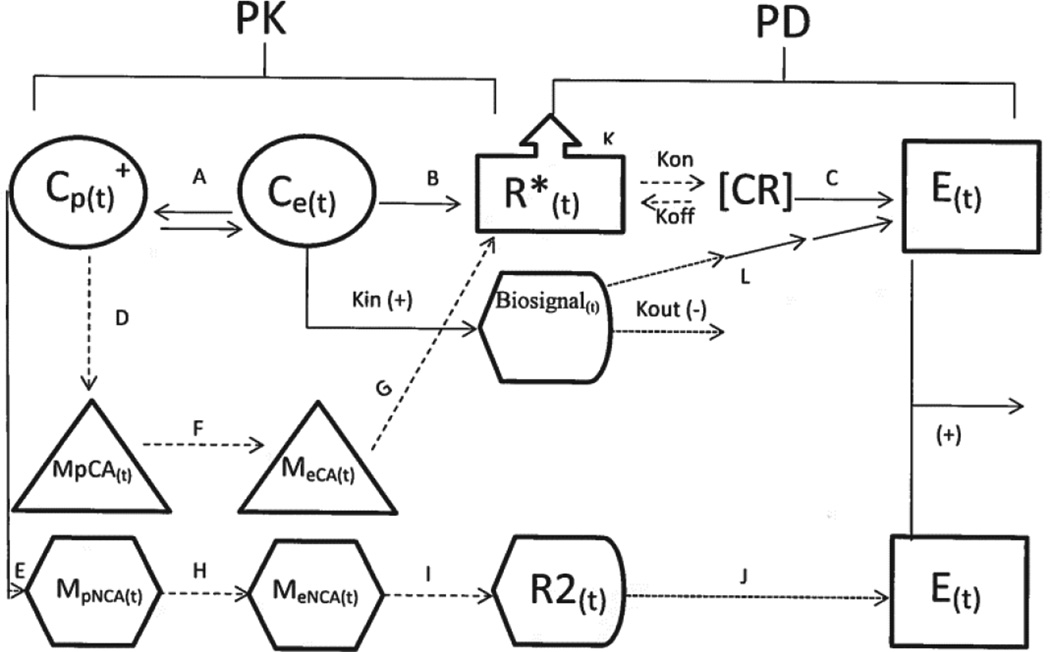

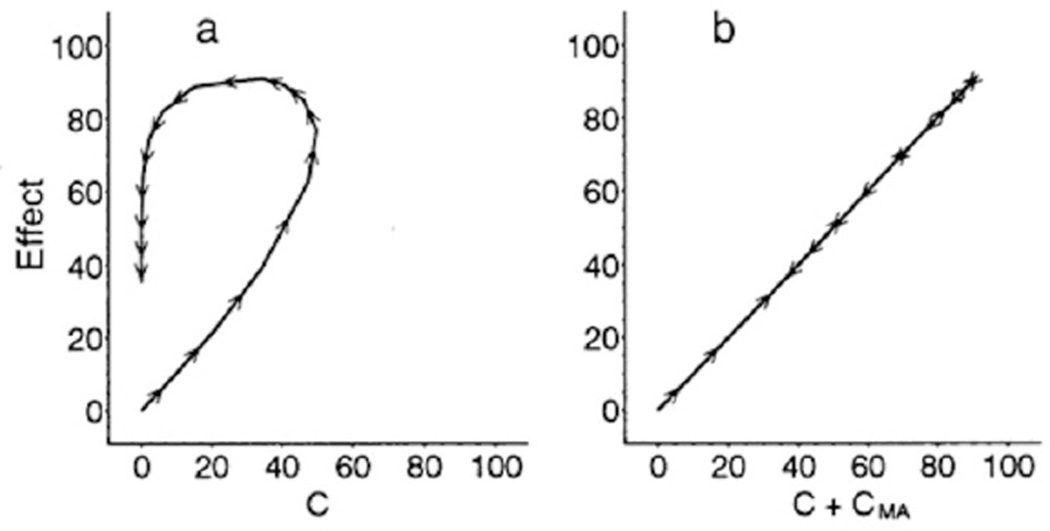

Counter-clockwise hysteresis loops in PK-PD relationships could be explained and defined [319] as a consequence of a number of factors illustrated below in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Factors Influencing Counter-clockwise Hysteresis Cp(t) = Plasma parent drug concentration, Ce(t) = “Effect site” concentration, R*(t) = Receptor site, E(t) = Effect, MPCA(t) = Metabolite(s) in plasma which are competitive agonists, MeCA(t) = Metabolite(s) in “Effect site” which are competitive agonists, MPNCA(t) = Metabolite(s) in plasma which are competitive agonists /(MPPCA) partial agonists which have noncompetitive agonist action acting on a different receptor BUT same Effect, MeNCA(t) = Metabolite(s) in “Effect site” which are competitive agonists which have non-competitive agonist action acting on a different receptor BUT same Effect, R2 = Alternate receptor site (with same Effect).

Counter-clockwise Hysteresis

- Disequilibrium caused by a temporal displacement can occur because of rate limiting steps:

- Step A: Instantaneous equilibrium between C and effect site concentrations (Ce) is not attained, which results in a temporal displacement (between C and Ce), where C(t) in plasma and Ce in the effect site are not identical and C(t) > Ce.[8]

- Step B: The rate of change of Ce is much greater than the rates of pharmacological receptor activation/deactivation (R*). For instance the number of activated receptors (R*) is not reflective of Ce at time (t), resulting in a temporal displacement (between Ce > and R*).[8]

- Step C: The overall rate of conversion of signal transduction induced by R* to measured E is much less than the rate of change of R* so that E(t) is not equal to R*(t), resulting in temporal displacement between R* >and E. The concentration (C) of drug binding with a receptor (R) forms a transient (CR) drug-receptor complex and this altered complex is affected by the receptor association and dissociation on and off the receptor. Kd is the receptor dissociation rate constant and is equal to the ratio of Koff/Kon.

- Transformation of a drug or prodrug into a metabolite(s) with agonist actions (MPCA / MPPCA or MPNCA) are formed from the parent drug (D or E) and are included in the contribution of the combined measurement of E.

- Step D: Common Receptor-Common Transduction Mechanism MPCA or MPPCA is a competitive agonist or competitive partial agonist with lower intrinsic activity, for which it occupies the same receptor (R*) as the parent drug concentration [EmaxMPCA or Emax MPPCa is less than Emax(C)]

- Step E: Separate Receptor-Common Transduction Mechanism. Metabolite with non-competitive agonist actions (MNCA) occupies a different receptor but the same effect is achieved through a similar mechanism.

- Step J: Separate Receptor Separate Transduction Mechanism MNCA is a non-competitive agonist, for which a different pharmacological receptor (R2) is occupied but the same E achieved through a different mechanism.

Step K: Changes in PD over time. PD has a distinct temporal component. For instance, up regulation of receptor response (R*) (Step K) (sensitization) when the EC50 might reduce over time.

Indirect physiological mechanism of drug action with changes in PD over time. A biosensor process leads to a positive modulation in production Kin or a negative change in degradation Kout of the biosignal may occur and be transduced (Step L) into an E.

- The measurement of C(t) is not specific and analysis should seek to measure the active component.

- Total (unbound and bound) drug analyzed is being measured over time rather than unbound concentration of drug being measured over time and time-dependent protein binding due to protein binding changes over time are occurring such that unbound pharmacologically active concentration reduces with time.[9]

- Total achiral (all enantiomers) drug concentration is being measured over time rather than enantiospecific concentration of a racemic drug through the use of non-stereospecific assays [10]. Stereospecific pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics are occurring leading to 1. Stereospecific disequilibirum 2. Stereospecific metabolism and/or 3. Stereospecific changes in PD occurring.

- Common Receptor-Common Transduction Mechanism Stereospecific Competitive Agonist/Partial Agonism.

- Separate Receptors-Common Transduction Mechanisms. One enantiomer with non-competitive agonist actions occupies a different receptor but the same effect is achieved through a similar mechanism.

- Separate Receptor Separate Transduction Mechanism. One enantiomer is a non-competitive agonist, for which a different pharmacological receptor (R2) is occupied but the same E achieved through a different mechanism.

- Total (parent drug + metabolites) concentration together are being measured by a non-specific analytical assay (i.e. radioimmunoassay, radioactive assay, or high performance liquid chromatographic assay, etc.), which is non-specific for the parent drug such that an assumed E vs. C plot is in actuality an E vs. C+MPCA or E vs. C+MPPCA plot.

-

5)A specific analytical assay has been developed to measure C, however, an unknown or unidentified agonist metabolite is adding to the E.

-

5)

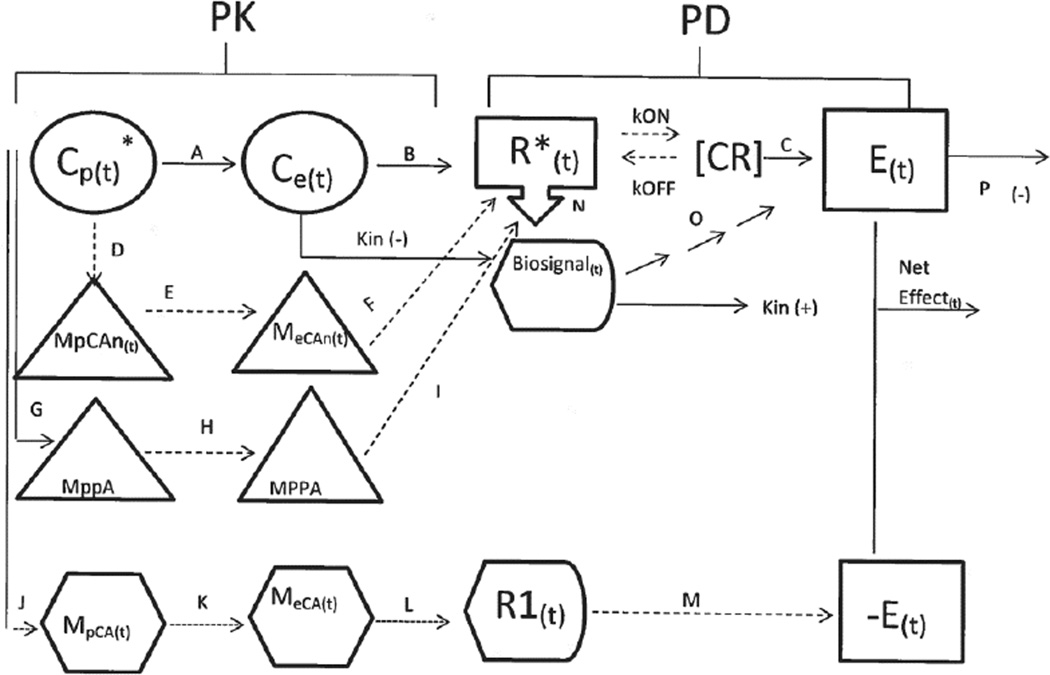

Clockwise hysteresis

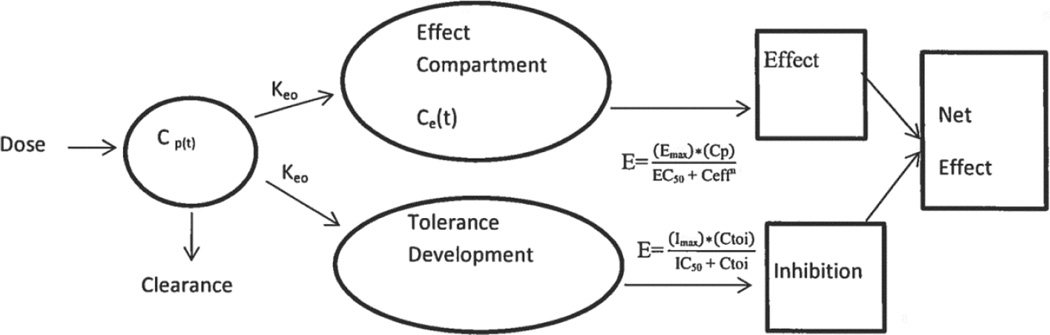

Clockwise hysteresis loops in PK-PD relationships could be explained and defined as a consequence of a number of factors illustrated below in Figure 3.

Disequilibrium caused by a temporal displacement that occurs because of a major rate limiting step: Step A: Disequilibrium occurs when Ce temporally precedes C(t). For instance, the rate of equilibration between arterial plasma concentrations (compartment delivering drug to effect site) and venous plasma concentrations (sampling compartment for drug concentration analysis) is significantly less between arterial concentrations and Ce such that C(t) is not equal to Ce(t), resulting in temporal displacement (between C(t) and Ce.)

- Metabolite(s) with antagonistic actions (MpCAn) are formed. Step D: Common Receptor-Common Mechanism. MpCAn is a competitive antagonist with no intrinsic activity, for which the same receptor (R*) is occupied as the administered drug concentration but it lacks pharmacological activity [Emax(MANTCA)~0 <<<< Emax(C)] so that receptor blockade occurs.[8]

- Step G: Common Receptor-Common Transduction Mechanism. MPPA is a partial competitive agonist with low intrinsic activity, for which it occupies the same receptor (R*) as the parent drug concentration [Emax(MPOa) is less than Emax(C)]

- Step J: Separate Receptor-Separate Mechanism. MpCA is a non-competitive antagonist (reverse agonist), for which it interacts with a different receptor (R1) than the drug concentration administered and has opposing effects over the measured E(t).

- Step N. Changes in PD over time. PD has a measurable temporal component. For instance, with tolerance down regulation of receptors leads to EC50 to increase and/or the Emax would decrease overtime.

Indirect mechanism of drug action with changes in PD over time. A biosensor process leads to a negative modulation of production Kin or a positive increase in degradation in Kout of the biosignal may occur and be transduced (Step O) into E.

Counter regulatory feedback regulation (Step P).

- The measurement of C(t) is not-specific.

- Total (unbound and bound) drug measured is being measured over time rather than unbound free concentration of drug being measured over time and time-dependent protein binding such as the protein binding changes over time are occurring such that unbound pharmacologically active concentration decreases with time [9].

- Total achiral (all enantiomers) drug concentration is being measured over time rather than enantiospecific concentration of a racemic drug through the use of non-stereospecific assays [10].

Figure 3.

Factors Influencing Clockwise Hysteresis Cp(t) = Plasma parent drug concentration, Ce(t) = “Effect site” concentration, R*(t) = Receptor site, E(t) = Effect, MpCAn(t) = Metabolite(s) in plasma which are competitive antagonists, MeCAn(t) = Metabolite(s) in “Effect site” which are competitive antagonists, MpCA(t) = Metabolite(s) in plasma which are competitive antagonists which have competitive agonist action acting on a different receptor BUT same Effect, MeCA(t) = Metabolite(s) in “Effect site” which are competitive antagonists which have competitive agonist action acting on a different receptor BUT same Effect, R1 = Alternate receptor site (with same but opposite Effect).

Stereospecific pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics are occurring leading to 1. Stereospecific Disequilibrium, 2. Stereospecific Metabolism and/or 3. Stereospecific Changes in PD occurring. A. Common Receptor-Common Mechanism Competitive Antagonism, where one enantiomer is active and the other has affinity but no activity.

B. Total (parent drug + metabolites) concentration together are being measured by a non-specific analytical assay is being utilized (i.e. radioimmunoassay, radioactive assay, or high performance liquid chromatographic assay, etc.) that is non-specific for the parent drug such that an assumed E vs. C plot is in actuality an E vs. C+MpCAN or E vs. C+MpCA plot.

A specific analytical assay has been developed to measure parent compound concentration, however, an unknown or unidentified antagonist metabolite is adding to the E.

The following overview of hysteresis loops aims to provide a comprehensive rather than exhaustive appraisal of the available pharmaceutical and biomedical literature in which hysteresis in either direction has been observed or studied. The goal of this article is to provide the reader with a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanistic reasons underlying why these phenomena can occur, provide examples of which drugs and group of drugs have been reported to exhibit these characteristics (Table 2 and 3), the effect that pharmaceutical formulation may have on the occurrence and change in direction of a hysteresis loop, and the main pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling approaches utilized to further understand hysteresis relationships.

Table 2.

Counter-clockwise Hysteresis

| Drug name | Drug /Class (Indication) |

Population / species studied (comorbidities) |

Route of Administration |

Proposed mechanism | Effect(s) measured |

Site of drug concentration measure |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha-human atrial natriuretic peptide |

Peptide drug | Rats | 6–12 µg/kg iv infusion over 60 min | Site of action, for diuretic effect, must be in a tissue or site other than the blood vessels. | Diuretic effect (%) | Plasma concentration (ng/mL) α-hANP | [11] |

| Aripiprazole | Atypical antipsychotic | 18 humans (healthy) | 2, 5, 10, 30mg single po doses | Limited access to the site of action due to the brain-blood barrier and transporters molecules on the barrier | Dopamine receptor occupancy (%) | Plasma concentration (ng/mL) of aripiprazole | [12] |

| Astragaloside IV | Anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory (Traditional Chinese Medicine) | Rats | 20 mg/kg Astragaloside IV, Atractylenolide I 2.165 mg/kg and 116.9 mg/kg Prim-O-glucosylcimifugin via intragastric lavage | Disequilibrium between effect site and central compartment | Spleen cell growth rate | Plasma concentration (ng/mL) | [13] |

| (+/−) Atenolol |

Beta-1 Selective Beta-Blocker | 10 rats | Immediate release pellets 16 mg/kg po single dose | Disequilibrium between effect site and central compartment | Change in Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | Atenolol concentration (µg/mL) | [14]* |

| Atracurium | Neuromuscular blocking agent | 10 humans (critically ill with acute respiratory distress) | 1 mg/kg iv bolus followed by 1mg/kg/hr for 72 hrs | Lag time between concentration and effect, effect may not begin until 80% of receptors are occupied | Train of four count as index of therapeutic effect | Plasma atracurium concentration (µg/mL) | [15] |

| Azithromycin | Macrolide antibiotic | Rats | 40, 100 mg/kg/h iv over 90 min | Delayed distribution in the effect site, potassium channels on ventricular myocytes | Change in QT interval (msec) | Plasma concentration of azithromycin (µg/mL) | [16] |

| (+/−) Baclofen |

Skeletal muscle relaxant | Mice | 1–3 mg/kg intraperitoneally | 2- compartment open model of effect | Antinociceptive effect (% MPE) | Baclofen blood concentration (µg/mL) | [17] |

| Befloxatone | Reversible and selective MAO inhibitor | 12 humans (healthy) | 5 mg po twice daily or 10 mg po once daily | Compartment effect or an indirect response | % of DHPG decrease from baseline | Plasma concentration of befloxatone (ng/ml) | [298] |

| Benidipine | Dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker | Rats | 1 mg/kg po | Effect-compartment model | Change in blood pressure (%) | Plasma concentration of benidipine (ng/mL) | [18] |

| Bromocriptine | Dopamine agonist | Rats | 2.5, 10 mg/kg ip | Equilibration delay between concentrations in the brain and concentration in plasma | Number of rotations (/15min) | Plasma bromocriptine concentration (ng/mL) | [19] |

| Bumetanide | Loop Diuretic | 3 humans (healthy) | 1 mg IR tablet po | Absorption rate | Urine flow rate (ml/h) | Plasma concentration of bumetanide (ng/ml) | [20]* |

| Bunazosin | Alpha-1 blocker | 9 humans (renal insufficiency) 11 humans (healthy) | 3 mg po (single dose) | Delay in the equilibration between the plasma concentration and concentration at the effect site | ΔSBP (mmHg) ΔDBP (mmHg) ΔHR (bpm) | Plasma bunazosin concentration (ng/mL) | [21] |

| (+/−) Buprenorphine |

Opioid analgesic | 4 Rats | 8 µg/kg iv over 20 seconds | Kinetics of target site distribution and receptor association/dissociation kinetics | Change in latency in cerebellum, the rest of brain, and specific binding site (sec) | Concentration of buprenorphine (ng/mL) | [22] |

| (+/−) Candesartan | Angiotensin II receptor blocker | 12 humans (healthy) | 8 mg po | Distributional delay between the concentrations in plasma and effect site | Pharmacodynamics (areas under the effect time profile: DR-1) | Pharmacokinetics (concentration equivalents: nKi) | [22] |

| (+/−) Candesartan | Angiotensin II receptor blocker | 12 humans (healthy) | 4, 8, 16 mg po (single doses) | Slow off-rate of candesartan from the receptor site | Diastolic BP | Plasma concentration of candesartan (ng/mL) | [23] |

| Cibenzoline | Class I antiarrhythmic agent | 6 humans (healthy) | 100 mg iv over 20 minutes | Lag between drug concentration and effect | QRS prolongation (% increase from baseline) | Cibenzoline plasma concentration (ng/mL) | [24] |

| Clarithromycin | Macrolide antibiotic | Rats | 6.6, 21.6, 43.2 mg/kg/h iv over 90 min | Delayed distribution in the effect site, potassium channels on ventricular myocytes | Change in QT interval (msec) | Plasma concentration of clarithromycin (µg/mL) | [16] |

| Clonidine | Alpha2- adrenergic agonist | 10 humans (healthy) | 200 µg po | Delay between drug receptor binding and observed effects | Rm threshold (mA) MAP (mmHg) |

Clonidine concentration (ng/mL) | [25] |

| Cocaine | Drug of abuse | 7 humans | Smoked doses (10, 20, and 40 mg) | Lag between blood concentration and effect due to drug being transported through tissues in the effect compartment | Heart rate mean change (BPM) and pupil diameter mean changr (mm) | Plasma cocaine concentration (ng/ml) | [299]* |

| Cocaine | Drug of abuse | 9 humans (healthy) | Smoked dose (12.5, 25, and 50 mg) and i.v. doses (8, 16, 32 mg) | Rapid distribution of drug to the brain | Mean change in systolic and diastolic pressure (BPM) and ratings of stimulated, high or drug liking | Arterial plasma cocaine concentration (ng/ml) | [300]* |

| Cyclosporin A | Calcineurin Inhibitor Immunosuppressant | Rats | Sandimmune single injection 1 and 10mg/mL | Delay in distribution of the drug to effect site | Calcineurin inhibition (%) | Cyclosporin A concentration (ng/mL) | [26] |

| Cysteamine | Cysteine depleting agent | 11 humans (nephropathic cystinosis) | Varied for each person, QID | Lag time between drug concentration and effect | White blood cell cysteine concentration (nmol ½ cysteine per mg protein) | Mean cysteamine concentration (µM) | [27] |

| D-amphetamine | Stimulant | 22 rats | 1.5 mg/kg D-amfetamine base IR | Delay of drug crossing the BBB and entering the striatal nerve terminals before releassing dopamine to produce the functional outcome | Striatal dopamine concentration (% of baseline) and Locomotor activity | Plasma amphetamine (ng/mL) | [28]* |

| [D- Penicillamine2,5] en kephalin (DPDPE) |

Opioid pentapeptide | Mice [FVB and mdr1a(2/2)] | 10 mg/kg i.v. | The site of action in both strains was pharmacologically distinct from the central compartment | Antinociception (% MPR) | Dose normalized blood concentration (ng/ml per mg/kg) | [329] |

| Diazepam | Benzodiazepine | 12 humans (healthy) | 0.1 mg/kg and 0.2 mg/kg iv infusion (four separate occasions) | None described | Digital Symbol Substitution Test Score (number correct) | Plasma concentration of Diazepam (ng/ml) | [301]* |

| Diazepam | Benzodiazepine | 3 humans (healthy) | 15, 30, and 50 mg iv infusion at 10 mg/min | Disequilibrium between plasma and effect compartment | EEG drug effect (uV) | Plasma concentration of Diazepam (ng/ml) | [302]* |

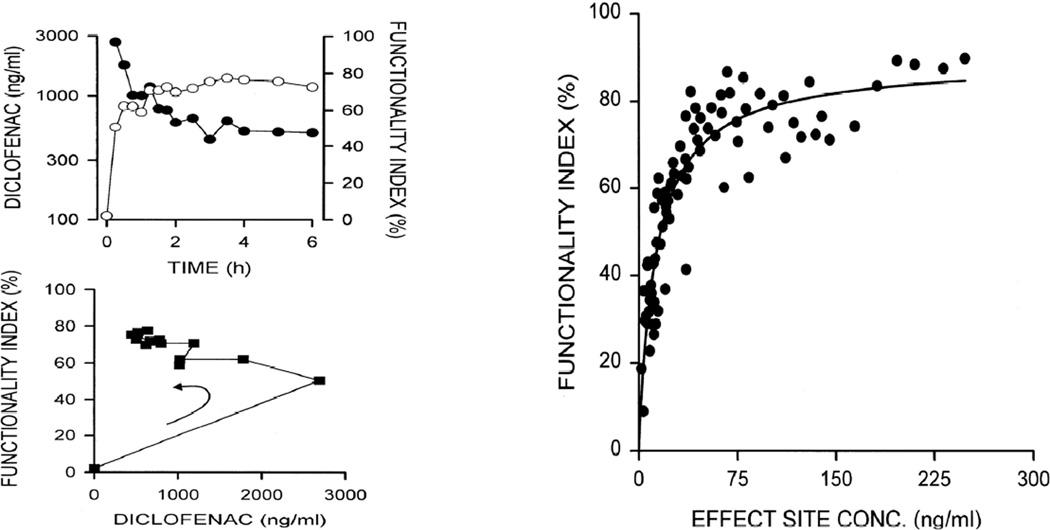

| Diclofenac | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent | 30 rats | 0.56, 1, 1.8, 3.2, 5.6, 10 mg/kg po | Slow equilibrium kinetics between diclofenac concentration in the central and effect compartments | Functionality index (%) (observed antinociceptive effect) | Blood concentration of diclofenac (ng/mL) | [29] |

| Diclofenac | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent | 20 humans (healthy) | 50 mg and 100 mg Diclofenac-Na effervescent po | Time delay between the plasma concentrations of diclofenac and the effect versus time profiles | Analgesic effects using an experimental human pain model | Blood concentration of diclofenac (ng/mL) | [30] |

| Dofetilide | Antiarrhythmic agent | 10 humans (healthy) | 0.5 mg iv infusion over 30 min | Delay of drug penetration to the active site | QTc (ms) | Plasma concentration of dofetilide (ng/mL) | [31] |

| Eptastigmine | Acetyl-cholinesterase inhibitor | 8 humans (healthy) | 10, 20, 30mg po single dose | Formation of active metabolites and/or a slow association to and dissociation from the enzyme in red blood cells | Average plasma cholinesterase inhibition (%) Average RBC cholinesterase inhibition (%) | Average eptastigmine plasma level (ng/mL) | [32] |

| Escitalopram | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | Mice | 1 mg/kg single sub cut injection | Slow permeation over the blood-brain barrier | 5-HTP Score | Escitalopram serum concentration (ng/mL) | [33] |

| Fantofarone | Calcium antagonist | 6 humans (healthy) | 100 mg and 300 mg po single dose | Effect compartment | PR Interval duration (ms) and Brachial Artery Flow (%) | Fantofarone SR 33671 Concentration (ng/ml) | [303] |

| (+/−) Felodipine |

Calcium channel blocker | 18 humans (4 healthy and 14 with impared renal function) | 10 mg felodipine orally as steady state | Slow equilibrium between drug and receptor | Effect of Diastolic Blood Pressure (% reduction) | Plasma Concentration (nmol/l) | [34] |

| Fenretinide | Synthetic retinoid | 50 children with neuroblastoma | 100–4000 mg/m2 po daily for 28 days | Presence of an effect compartment (possibly the liver) | Percentage reduction in retinol levels | Fenretinide (µM) | [35] |

| (+/−) Fexofenadine | H1-antagonist | 6 humans (healthy) | 60 mg po tablet | Equilibration delay between the plasma concentration and effect site compartment | QTc interval in milliseconds | Fexofenadine concentration (ng/mL) | [36] |

| (+/−) Flurbiprofen | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent | 8 rats | 10 mg/kg gastric intubation sustained release granules | Intestinal permeability changes by the sustained release formulation is not only due to systemic availability of the NSAID since it may be also resulted from continuous exposure of the intestinal tract to the drug | Change in intestinal permeability | S-Flurbiprofen concentration (µg/mL) | [37] |

| Furosemide | Loop diuretic | 26 humans (healthy) | 60 mg tablet po | Delay of effect | Diuresis (mL/min) | Furosemide excretion rate (µg/min) | [38]* |

| Furosemide | Loop diuretic | 4 humans (healthy) | 40 mg IR tablet po | Inhibition of the reabsorption of sodium and chloride at Loop of Henle was delayed due to fast absorption resulting in rapid excretion | Diuretic rate (ml/h) | Excretion rate of furosemide (mg/h) | [39]* |

| Furosemide | Loop diuretic | 11 humans, Middle Eastern Arabs (healthy) 12 humans, Asian (healthy) | 40 mg tab po single dose | Delay in drug action/delay in equilibrium | Furosemide excretion rate | Plasma concentration of furosemide | [40]* |

| Furosemide | Loop diuretic | 8 humans (healthy) | 10 mg iv infusion over 10 minutes | Delay between excretion rate and the diuretic effect | Diuresis (mL/min) and Natiuresis (mmol/min) | Furosemide excretion rate (µg/min) | [41]* |

| Indomethacin | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent | 6 rats | 10 and 20 mg/kg po doses | Effect-compartment model | Mean urinary 51Cr-EDTA excretion | Indomethacin plasma concentration (mg/L) | [42] |

| Insulin (Regular and NPH) |

Peptide hormone | 16 humans (healthy) | 10 Units regular insulin given subcutaneously or 25 Units NPH given subcutaneously as single dose | Delay between serum insulin concentrations and effect | Glucose Infusion Rate (mmol/min) | Insulin serum concentration (pmol/L) | [304] |

| (+/−) Irbesartan |

Angiotensin II Receptor Blocker | 36 humans | 150 or 300 mg tablet po single dose | Vasodilatory effect of irbesartan on the AT1 receptor (effect compartment model) | DBP (mmHg) SBP (mmHg) | Plasma drug concentration of irbesartan (µg/mL) | [43] |

| (+/−) Irbesartan |

Angiotensin II Receptor Blocker | 10 dogs | 2 mg/kg or 5 mg/kg po dose (2 treatments 3 weeks apart) | Time needed for the drug distribution from the central compartment to AT1 receptors | Inhibitory effect on SBP (mmHg) | Plasma drug concentration of irbesartan (ng/mL) | [305]* |

| Isosorbide dinitrate | Antianginal agent | 11 humans (coronary artery disease) | 2 mg iv over 15 min, 5 mg sublingual tablet | Changes in blood pressure response lag behind changes in plasma Isosorbide dinitrate concentration | Percent change in standing systolic pressure | Plasma isosorbide dinitrate concentration (ng/mL) | [44] |

| (+/−) Isradipine |

Dihydropyridine Calcium channel blocker | 10 humans (healthy) | 1 mg iv infusion 5 mg po solution 5 mg tablet 10 mg slow release formulation | Possible active metabolite | DBP fall (mmHg) | Concentration of isradipine (ng/mL) | [45] |

| (+/−) Itraconazole | Antifungal agent | Rats | 5 & 40 mg/kg 5 min infusion | Factors other than itraconazole determine the time course for the inhibition of CYP3A | Hepatic availability | Itraconazole concentration (µM) | [46] |

| Lafutidine | H2-receptor antagonist | 5 humans (healthy) | 10 mg po tablet | Equilibration delay between the plasma concentration and effect site | Δ pH after postprandial dose | Lafutidine plasma concentration (ng/mL) | [47] |

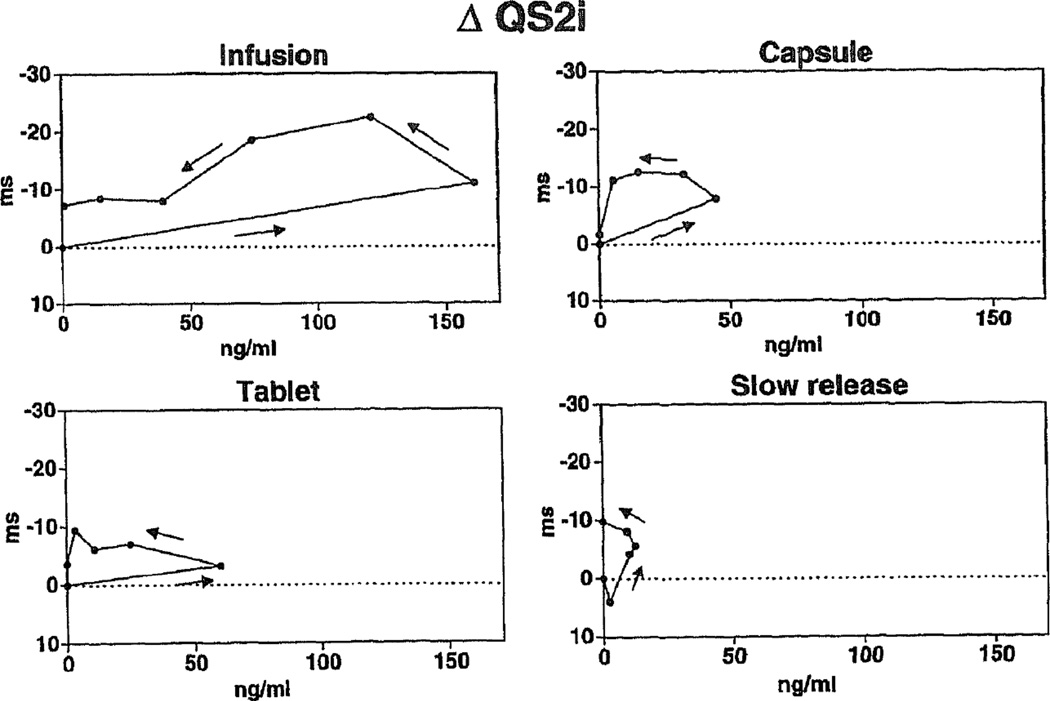

| Levosimendan | Calcium sensitizer | 29 humans (congestive heart failure) | 0.2 µg/kg/min 6 hr continuous infusion or 2 mg single po dose | Delay of drug distribution to its cardiac site of action | QS2i mean change (ms) sBP mean change (mmHg) dBP mean change (mmHg) HR mean changes (bpm) | Levosimendan (ng/mL) | [48] |

| Levosimendan | Calcium sensitizer | 10 humans (healthy) | 2 mg iv, tablet, capsule, SR tablet (single doses) | Takes time for the drug to distribute from plasma to its cardiac site of action | Δ QS2i (ms) | Plasma concentrations of levosimendan | [49] |

| Lignocaine (Lidocaine) |

Anesthetic | 5 sheep | 50 mg, 75 mg and 100mg iv bolus | Lack of pseudo equilibrium between the drug concentrations in the blood and at the receptor sites responsible for drug action in the myocardium | Percentage decreases of myocardial contractility | Atrial lignocaine concentrations (µg/mL) in arterial blood and coronary sinus blood | [50] |

| Lisdexamfetamine | Stimulant | 22 rats | 1.5 mg/kg ip D-amphetamine base 5 mg/kg ip D-amphetamine base | None described | Striatal dopamine concentration (% of baseline) and locomotor activity | Plasma amphetamine (ng/mL) Dopamine concentration in the striatum (% of baseline) | [28]* |

| (+/−) Lorazepam | Benzodiazepine | 6 humans (healthy) | 0.057 mg/kg solution single oral dose | The site of action of lorazepam is kinetically distinguishable from the plasma compartment and there is a distinct time lag between changes in plasma concentration and changes in CNS effects | Subcritical tracking, sway open and digit symbol substitution | Plasma lorazepam concentration (ng/mL) | [51] |

| (+/−) Lorazepam | Benzodiazepine | 9 humans (healthy) | 2 mg bolus iv loading dose followed by a 2 µg/kg/hr infusion for 4 hrs | Delay in equilibration of lorazepam between plasma and the site of pharmacodynamics action in the brain | Percent beta EEG amplitude (change over baseline) | Plasma lorazepam concentration (ng/mL) | [52] |

| Losartan | Angiotensin II receptor blocker | 12 humans (healthy) | 50 mg po | Distributional delay between the concentrations in plasma and effect site | Pharmacodynamics (areas under the effect time profile: DR-1) | Pharmacokinetics (concentration equivalents: nKi) | [22] |

| (+/−) Meperidine | Opioid analgesic | Sheep | 100 mg iv dose over 1 second | None described | Contractility (% reduction) | Concentrations of meperidine in myocardium and coronary sinus blood (mg/L) | [53]* |

| Metformin | Biguanide anti-hyperglycemic | 22 humans (healthy) | 500 mg po | Time delay between the change in plasma concentration and the drug effects | Change % for baseline in plasma glucose concentration | Plasma concentration of metformin (µg/mL) | [54] |

| Metocurine | Neuromuscular blocking agent | 15 dogs 5 pigs | Brief, constant rate infusion | Equilibration delay between drug concentration in the plasma and drug concentration at the site of effect | % NM blockade | Plasma metocurine (µg/mL) | [55] |

| Midazolam | Benzodiazepine | 8 humans (healthy) | 0.1 mg/kg constant rate iv infusion for 1 min | Equilibration effect-site delay | Change in %SB | Plasma midazolam concentration | [52] |

| Midazolam | Benzodiazepine | 12 humans (healthy) | 0.03 mg/kg and 0.07 mg/kg iv infusion (four separate occasions) | Lag time to onset of peak effect | Digital Symbol Substitution Test Score (number correct) | Plasma concentration of Midazolam (ng/ml) | [301] |

| Midazolam | Benzodiazepine | 3 humans (healthy) | 7.5, 15, and 25 mg iv infusion at 5 mg/min | Disequilibrium between plasma and effect compartment | EEG drug effect (uV) | Plasma concentration of Midazolam (ng/ml) | [302] |

| Molsidomine | Vasodialator | 11 humans (CAD) | 4 mg po (single dose) | Active metabolite | Decrease in end-diastolic diameter | Plasma concentration of molsidomine (µg/mL) | [56] |

| (+/−) Morphine |

Opioid analgesic | Rats | 2.5 mg/kg Intraperitoneal 2.5 mg/kg Nose drops |

Direct nose-to-CNS drug transport mechanisim | Analgesic effect (%MPE) | Morphine (ng/ml) | [57]* |

| (+/−) Morphine |

Opioid analgesic | Rats | 14.0 mmol/kg morphine | Delay of polar morphine crossing the BBB | % Anti-nociceptive response (using tail flick method) | Plasma morphine (µmol/L) and Brain morphine (nmol/g), | [58]* |

| (+/−) Morphine |

Opioid analgesic | Rats | 15 mg/kg morphine through intragastric administration (single dose) | Disequilibrium between biophase and plasma compartments | %MPE on MPR (mechanical pain response) | Concentration of blood morphine (µg/L), concentration of CSF morphine (µg/L), both conjugated and unconjugated | [59]* |

| Morphine | Opioid analgesic | Rats | 10 minute i.v. infusion at 4 mg/kg | Effect compartment | EEG amplitude 0.5–4.5 Hz (µV) | Morphine blood concentration (ng/ml) | [328]* |

| Naproxen | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent | Rats (induced hepatitis) | 6 mg/kg po (single dose) | Slow transport of naproxen from circulation to its site of action | Protection (%) | Plasma concentration of naproxen (µg/mL) | [60] |

| Nitroglycerin | Vasodilator | 6 humans (healthy) | 10, 20, 40 µg/min iv infusions | End product inhibition or saturable binding of nitroglycerin to blood vessels | Nitroglycerin Css (ng/mL) | Infusion rate (µg/min) | [61] |

| Nitroglycerin | Vasodilator | 4 dogs | 10, 20, 50, 70 µg/min iv infusion | Active metabolites | Systolic blood pressure decreases (mmHg) | Nitroglycerin concentration (ng/mL) | [62] |

| NPH insulin | Intermediate acting insulin | 6 humans (healthy) | 25 U single subcutaneous dose | Delay between serum insulin concentrations and effect | Glucose infusion rate (mmol/min) | Measured serum concentration (pmol/L) | [63] |

| Pancuronium | Neuromuscular blocking agent | 11 humans (undergoing elective surgery) | 2 or 4 µg/kg/min by i.v. infusion | Effect compartment | Degree of neuromuscular paralysis (%) | Plasma concentration (µg/mL) | [307]* |

| Paroxetine | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | Mice | 0.27 mg/kg single sub cut injection | Slow permeation over the blood-brain barrier | 5-HTP Score | Paroxetine serum concentration (ng/mL) | [33] |

| (+/−) Penbutolol | Beta-blocker | 7 humans (healthy) | 40 mg po film-coated tablets | Active metabolite formation | Standardized antagonist concentration in plasma (IAN/KIAN) | Standardized penbutolol concentration in plasma (Cpen/Kip) | [64] |

| Perindoprilat | Perindopril (ACEI) active metabolite | 10 humans (CHF) | 4 mg po (single dose) | Effect compartment | Plasma converting enzyme activity (PCEA) and brachial vascular resistance (BVR) | Plasma concentrations of perindoprilat (ng/ml) | [310] |

| Pimobendan | Vasodilator | 8 humans (healthy) | 7.5 mg po 5 mg iv | Effect-compartment model | % of maximal decrease in LVESD | Pimobendan in plasma (ng/mL) | [65] |

| Pinacidil | Vasodilator | 12 humans (healthy) | 25 mg tablet or capsule po once daily for 1 week | Time lag to equilibrium | Mean HR (beats/min) Mean ΔHR (beats/min) Mean DBP (mm Hg) Mean ΔDBO (mm Hg) | Mean extrapolated CP (ng/mL) | [66] |

| Pregabalin | Analgesic/anticonvulsant | Rats | 6mg/kg po | Not active metabolite | % protection MES | Pregabalin ECF concentration (ng/mL) | [67] |

| Propofol | General anesthetic | Sheep | 100 mg iv infusion over 2 min | Disequilibrium due to organ drug uptake following rapid drug administration. | Depth of anesthesia (% baseline) CBF (mL/min) |

Arterial concentrations (µg/mL) Sagittal sinus concentrations (µg/mL) Arterial concentrations (µg/mL) | [68]* |

| (+/−) Propranolol | Beta-blocker | 6 humans | 3 × 20 mg PL po tablet or 60 mg LA po tablet | Two distinct beta-adrenoceptor binding sites on the surface membrane which differ in lipophilic characteristics | Beta-blocking activity (%R) | Plasma propranolol concentration (µg/mL) | [304]* |

| (+/−) Quinine | Antimalarial | 6 humans (healthy) | 15 mg/kg po dose and 15 mg/kg iv infusion administered over 6 hours | None described | Hearing threshold shift (dB) | Quinine plasma concentration (µmol/L) | [309] |

| (R)-3-[1-(2,6- Dichloro-3-fluoro- phenyl)-ethoxy]-5- (1-piperidin-4-yl- 1H-pyrazol-4-yl)- pyridin-2-ylamine (PF02341066) |

ATP-competitive small molecule inhibitor of cMet receptor tyrosine kinase | Mice (GTL16 gastric carcinoma or U87MG glioblastoma xenografts) | Oral administration of 8.5, 17, and 34 mg/kg; 3.13, 6.25, 12.5, 25, and 50 mg/kg; and 3.13, 6.25, 12.5, 25, and 50 mg/kg | Slow distribution to tumors | cMet phosphorylation response | Plasma concentration of PF02341066 (ng/ml) | [327] |

| Ranitidine | H2-receptor antagonist | 41 humans (renal impairment) | Single 50 mg and 25 mg iv doses | Effect compartment | Gastric pH | Serum ranitidine concentration (ng/ml) | [310] |

| Regular insulin | Peptide hormone | 10 humans (healthy) | 10 U single subcutaneous dose | Delay between serum insulin concentrations and effect | Glucose infusion rate (mmol/min) | Measured serum concentration (pmol/L) | [63] |

| Remifentanil | Opioid analgesic | 10 humans (healthy) | 3 µg/kg/min for 10 minutes | Equilibrium delay between arterial opioid concentration and concentration at the site of drug effect (brain) | Spectral Edge (Hz) (opioid effect) | Arterial remifentanil concentration (ng/mL) | [69]* |

| Risperidone | Antipsychotic agent | 9 humans (healthy) | 1 mg po (single dose) | Drug moves from the plasma to the effect compartment after time delay | EEG effect | Plasma concentration of risperidone (ng/mL) | [70] |

| Roxithromycin | Macrolide antibiotic | Rats | 20, 40 mg/kg/h iv over 90 min | Delayed distribution in the effect site, potassium channels on ventricular myocytes | Change in QT interval (msec) | Plasma concentration of roxithromycin (µg/mL) | [16] |

| Sertraline | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | Mice | 2.2 mg/kg single sub cut injection | Slow permeation over the blood-brain barrier | 5-HTP Score | Sertraline serum concentration (ng/mL) | [33] |

| Sevoflurane | General anesthetic | 21 Humans (healthy) | Inhalation initially at 1% then increased by 1% to a max of 8%. Then decrease to 1% | Delay of drug concentration at the effect site | QTc interval (m sec) | End-tidal sevoflurane concentration (%) | [71] |

| Sinemet | Anti-parkinson’s agent | 11 humans (Parkinson’s) | Carbidopa 25mg/L-DOPA 100mg po | Takes time for L-DOPA to distribute to the central nervous system | Taps per 60 seconds | Levodopa (µg/mL) | [72] |

| Tacrolimus | Calcineurin Inhibitor | Rats | Prograf single injection 0.1 and 5mg/mL | Delay in distribution of the drug to effect site | Calcineurin inhibition (%) | Tacrolimus concentration (ng/mL) | [26] |

| Tacrolimus | Calcineurin inhibitor | 5 guinea pigs | 0.01 or 0.1 mg/hr/kg iv infusion | The delay in distribution from blood to the ventricle | Change in QTc (msec) | Plasma tacrolimus concentration (ng/mL) Whole blood tacrolimus (ng/mL) | [73] |

| Telmisartan | Angiotensin II receptor blocker | 48 humans (healthy) | 20, 40, 80mg po | Delay and longer persistence of effect than expected, slow dissociation from the receptor | Inhibition (%) | Plasma concentration of telmisartan (mg/L) | [74] |

| Terfentanil | Opioid analgesic (investigational) | 14 humans (healthy) | 4 µg /kg/min for a maximum of 30 minutes or until maximum EEG changes occurred (adjusted by investigators) | Effect compartment | Spectral edge (95%) Hz | Plasma terfentanil concentration (ng/ml) | [318] |

| Tesofensine active metabolite (M1) |

serotonin–noradrenaline–dopamine reuptake inhibitor | 228 mice | 0.3 to 20 mg/kg iv and po | Distribution of the molecules between the plasma and the central nervous system | Inhibition (%) | Tesofinsine plasma concentration (ng/mL) | [75] |

| (+/−) Thiopental | General anesthetic Barbiturate | 4 sheep | 750 mg iv over 2 min | Presence of effect compartment | Maximum rate of change of left ventricular pressure (% reduction from baseline) | Thiopental concentrations of arterial (µg/mL) and coronary sinus (µg/mL) | [76] |

| Tinzaparin | Low molecular weight heparin | 6 dogs | 4 mg/kg sC | Delay in systemic availability | Anti-factor Xa activity (IU/mL) (biological effect) | Plasma concentration of heparin material | [77] |

| Triazolam | Benzodiazepine | 10 humans (healthy) | 1 mg solution po (single dose) | The site of action of triazolam is kinetically distinguishable from the plasma compartment and contains a distinct time lag between changes in the plasma concentration and changes in CNS effect | Subcritical tracking, body sway and digit symbol substitution | Plasma triazolam (ng/mL) | [78] |

| Trimoprostil | Prostaglandin E2 analog | dogs | 250µg po capsule 500µg po capsule 250µg po solution | Delay in equilibrium between plasma concentrations and concentrations at the site of action | Mean % inhibition of gastric acid secretion | Mean trimoprostil plasma concentrations (ng/mL) | [79] |

| (+/−) Verapamil | Calcium channel blocker | 22 humans (healthy) | Single dose i.v. infusion (0.15 – 0.22 mg/kg) | Time lag between plasma verapamil concentrations and maximal drug effect on AV conduction | Change in PR interval (ms) | Plasma verapamil concentration (ng/ml) | [311] |

| Zabiciprilat | Zabicipril (ACEI) active metabolite | 6 humans (healthy) | 0.5 and 2.5 mg po zabicipril | Effect compartment | Plasma converting enzyme activity (PCEA) and brachial/femoral artery flow (BAF, FAF ml/min) | Zabiciprilat plasma concentration (ng/ml) | [312] |

+/− Indicates Racemic Drug with Enantiomers

Indicates Drug listed in both Table 2 and 3

COUNTER-CLOCKWISE HYSTERESIS

A counter-clockwise hysteresis loop may signify an increasing pharmacological effect compared with earlier temporal pharmacological effects obtained with the same plasma concentration of drug. There are a variety of examples in the literature that suggest this type of pharmacokinetic / pharmacodynamic relationship as demonstrated in Table 2 [11–79, 298–312, 318, and 327–329]. A counter-clockwise hysteresis may mechanistically manifest due to a variety of underlying mechanisms as discussed below.

Distribution Delay into Site of Effect

Counter-clockwise hysteresis loops can occur because of a distribution delay between the systemic drug concentration and the time to reach the effect site. This is the most commonly encountered underlying mechanism responsible for the finding of a counter-clockwise hysteresis loop. Effect-concentration is time-dependent and an indirect link is made between the two variables.

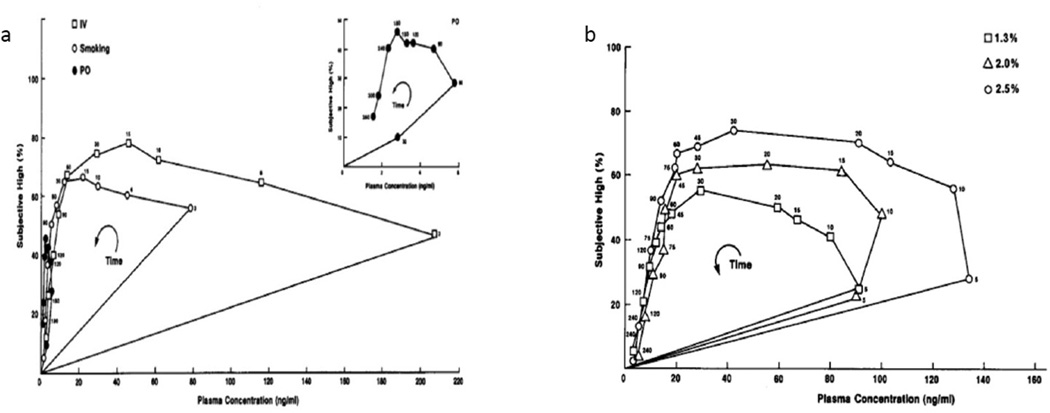

For example, a delay for a drug to be transported from the systemic circulation to its site of action to elicit a response has been reported for Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) after intravenous, oral or smoking administration, and after various intravenous doses [107]. It was observed that counter-clockwise hysteresis was evident after intravenous and smoking administration because THC takes a finite time in order to equilibrate with one of its sites of action (brain). However, it was also observed that after oral administration no hysteresis loop was evident because more time was allowed for penetration into the brain [107]. In the case of intravenous and smoking administration, the time necessary to reach equilibrium was approximately 15 minutes (Figure 4a). Furthermore, it can be observed that the counter-clockwise hysteresis loop was evident after all the intravenous doses (Figure 4b), indicating that this phenomenon is both dose and route-independent [107]. It can be observed that the location and the protective barriers surrounding the active site, in this case the brain, plays a critical role in the occurrence of hysteresis. As the brain possesses multiple protective barriers such as the blood-brain barrier (BBB) it could be expected that a delay in reaching the site of action would occur. This type of hysteresis was also observed for morphine after subcutaneous administration (14 µmol/kg) to rats with renal failure in which counter-clockwise hysteresis was developed between anti-nociceptive activity and morphine plasma concentrations, which correlated with an equilibrium delay as the consequence of the ability of morphine to cross the BBB [58].

Figure 4.

Counter-clockwise hysteresis of Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) plasma concentrations versus self-reported subjective “High” effect (a) different routes of administration and (b) different dosages. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics, [107], copyright 1984.

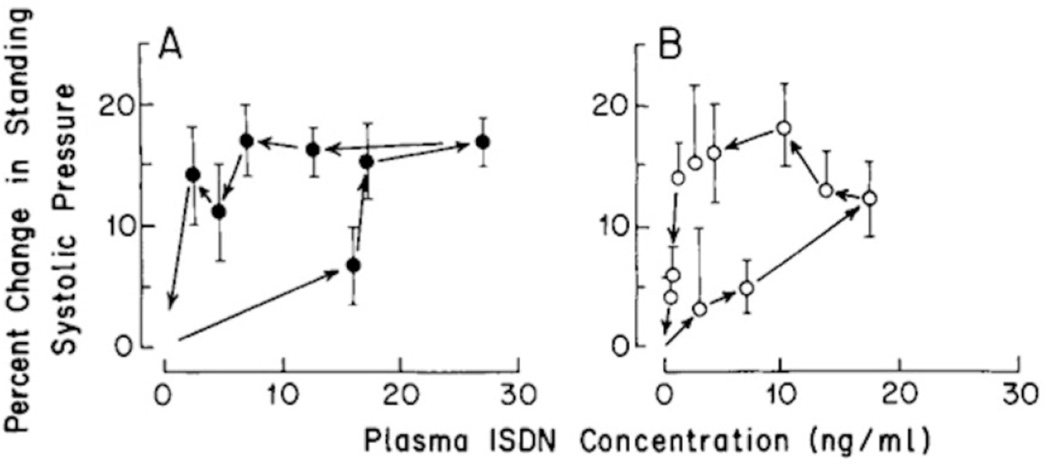

The organic nitrate isosorbide dinitrate (ISDN) exhibited counter-clockwise hysteresis after intravenous infusion (0.133 mg/min for 15 min) or sublingual (5 mg) administration (Figure 5) [44]. It was observed that the changes in standing systolic pressure were greater during the declining phase than in the ascending phase after IV and sublingual administration [44], this correlated with previous studies after oral administration [108].

Figure 5.

Relationship between plasma ISDN concentration and response after intravenous (●) and sublingual (○) dosing. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics, [44], copyright 1983.

The proposed mechanism for this hysteresis was a delay in distribution to the active site in tissue, a delay in saturation at the receptor level because it is a non-instantaneous event, or contribution of vasoactive metabolites [109, 110] which are less active than parent drug [44]. However, the main factor responsible appears to be the delay in equilibrium between the plasma and the site of action [44].

Slow Receptor Kinetics

Drug receptor theory states that as drug concentration increases the occupancy of the receptor will increase rapidly at first but then it will progressively decrease as the receptors become occupied, and that the drug concentrations necessary to achieve maximal effect (Emax) can be many fold higher than that necessary to produce a 50% response. [5]. However, not all drug receptor interactions can be described by an Emax model since there are limitations in the type of binding, regulation, type of receptors, and the use of surrogate sample-feasible biological matrices (i.e. blood) instead of the actual receptor binding site [5]. However, besides the limited access of drugs to the site of action the presence of slow receptor kinetics are recognized as one of the main causes of counter-clockwise hysteresis [111]. It has been reported that in the case of anti-psychotic drugs they need to traverse not only the BBB but also the transporters that reside in this barrier [12]. The rate at which drugs bind to the receptor (kon) and the rate at which it dissociates from a receptor (koff) determine the kinetics of a drug such as in the case of anti-psychotic drugs and their relationship with the dopamine D2 receptor [12]. For these types of drugs the kon values show low variability for various drugs, but the koff can vary within a 1000-fold range [112]. This switching movement has been evaluated by positron emission tomography (PET) studies in dopamine receptor occupancy after single oral administration of aripiprazole (2, 5, 10 or 30 mg) to healthy subjects, which reported that a high receptor occupancy was present after administration (lower arm of hysteresis), but low receptor occupancy was observed at later time points post-drug administration (upper arm of hysteresis) [12].

In the case of telmisartan, an angiotensin receptor antagonist, counter-clockwise hysteresis was observed between plasma concentration and angiotensin II response after oral administration (20, 40 or 80 mg) following an angiotensin II challenge [74]. It was determined that the hysteresis could be explained because of the tight binding and subsequent slow dissociation of telmisartan from the receptor (AT1) on the vascular smooth muscle cells [74], which was based on the 3H-telmisartan binding to rat lung AT1 receptors and slow dissociation (t1/2 = 5.9 h) from the binding sites [113]. Furthermore, the slow dissociation from the AT1 receptor can also contribute to the antagonism of telmisartan [74, 114]. Similarly, candesartan cilexetil and losartan after oral dosing exhibited counter-clockwise hysteresis after angiotensin II challenge in healthy subjects, and it was reported that candesartan exhibited a slower off-rate from the AT1 receptor than losartan [22]. However, the extent of insurmountable antagonistic activity [115–117] or differences in distributional phenomena could also occur. The slow onset of the inhibitory effect on blood pressure for candesartan [23,118–119] could result in a longer than expected PD effect based on the plasma concentrations [22]. On the contrary, in the case of irbesartan the pharmacological effects in the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) are related to the blockade of AT1 receptors by increasing the plasma angiotensin II and plasma renin activity for which an actual clockwise hysteresis was reported [92]. It was reported that the duration of the antagonism of AT1 receptor for irbesartan would be longer than predicted using plasma concentrations [92] as demonstrated after single 150 mg PO for which the antagonism lasted for 2 days, which was much longer than valsartan and losartan [120].

Delayed or Modified Activity

The pharmacological response of a drug is not only bound by the rate of binding to a specific receptor, but can also be related to a progressive series of stochastic events that could cause a modification or delay in pharmacological activity. [63]. For both regular and neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin after a single subcutaneous injection of 10 U or 25 U, the time to reach maximum infusion rate of glucose infusion (Rmax), namely TRmax, occurs at a later time than tmax indicating a delay between maximum serum concentrations and the maximum PD effect. This delay was more obvious for regular insulin, and when the serum concentrations were correlated with glucose infusion rate (GIR) values, a counter-clockwise hysteresis loop was observed for both types of insulin. As the difference in delay between regular and NHP insulin is appreciable, the hysteresis loop was greater for regular insulin than NPH insulin [63].

In the case of molsidomine [a prodrug for the formation of nitric oxide (NO)] it first requires biotransformation (rapid hydrolysis) to its active metabolite SIN-1, which downstream will release NO [56]. It is because of this metabolic delay in the formation of NO from SIN-1 that counter-clockwise hysteresis has been reported in the change of diastolic diameter after a single oral dose (4 mg) of molsidomine to coronary artery disease (CAD) patients [121]. These findings correlated with a separate study in which finger pulse curve as a PD effect exhibited counter-clockwise hysteresis after administration of molsidomine (8 mg) to healthy subjects [122].

Active Agonist Metabolite

As the existence of first pass metabolism occurs predominantly in the liver, the route of administration may play a critical role in the appearance of a hysteresis loop. Hysteresis is possible because a drug can be converted to an active metabolite that has a Cmax and a combined peak activity at a later time point compared to the parent drug [5]. For instance, midazolam exhibited a slower reaction time when administered orally compared to intravenous administration, and when the concentrations were combined (both oral and intravenous routes) a counter-clockwise hysteresis loop was evident. However, when the active metabolite α-hydroxy midazolam was analyzed, their combined concentrations gave similar reaction times regardless of the route of administration [123].

Itraconazole (ITZ) is a chiral oral active triazole anti-fungal agent that has non-linear PK in rats and humans and dose-dependent first pass metabolism [124–127], and it is also metabolized by CYP3A to the major chiral metabolite hydroxyitraconazole (OH-ITZ) that has similar anti-fungal activity compared to ITZ [125, 128]. Counter-clockwise hysteresis was observed between the ITZ and OH-ITZ concentrations entering the liver (expressed as an average of portal venous and aortic concentrations, assuming that the liver receives 25% of total blood flow via the hepatic artery and 75% via the portal vein) after duodenal infusion of ITZ (5 or 40 mg/kg) to chronically catheterized rats [46]. Once the change in hepatic availability (FH) versus ITZ concentrations were plotted over time, a counter-clockwise hysteresis loop was observed indicating an equilibration delay between ITZ and effect (FH) or another factor that would control FH such as the production of an active metabolite. The importance of metabolism was evident because of the lack of hysteresis and only a direct hyperbolic relationship between FH and OH-ITZ. This lack of hysteresis indicates that this metabolite or some other factor with a similar time course would be the key regulator of CYP3A inhibition and the hepatic availability (FH) of ITZ. Similar relationships were obtained at the 40 mg/kg dose [46]. However, although analytical assays were capable of measuring the parent compound and its metabolite, no stereospecific analysis was undertaken to delineate the importance of chirality of this racemic drug and the influence of stereoselective metabolism, which should be considered in the interpretation of the mechanism underlying the hysteresis loop.

The cholinesterase inhibitor eptastigmine was administered to healthy volunteers as a single oral dose (10, 20 or 30 mg), and counter-clockwise hysteresis was observed between plasma eptastigmine concentrations and both red blood cell acetyl-cholinesterase inhibition and plasma butyrylcholinesterase inhibition [32]. It was evident that eptastigmine is more effective and provides a longer duration in inhibition of cholinesterase in RBC (acetyl-cholinesterase) than in plasma (butyryl-cholinesterase), which is similar to previous reports in young [129,130] and elderly subjects [131]. However, these previous findings do not correlate with in vitro studies in which it has been reported that eptastigmine is more active on butyryl-cholinesterase compared to acetyl-cholinesterase [132], which could be attributed to the formation of active metabolites such as 3'- and 5'-carboxylic acid derivatives and 3'-carboxylic acid-1-demethyl derivative [133]. Thus, the therapeutic drug monitoring should not be performed using the unchanged eptastigmine concentrations [32]. Furthermore, the observed counter-clockwise hysteresis in RBCs indicates that eptastigmine does not develop acute tolerance, which could be explained by the formation of active metabolites but also because eptastigmine slowly dissociates from acetyl-cholinesterase in RBCs [134]. The observed invertible character of the hysteresis loop in plasma butyryl-cholinesterase inhibition s suggests that eptastigmine reaches immediate equilibrium with the enzyme [32].

Furthermore, as presented by Gupta et al. [8] the potency of parent compound and the agonistic metabolite (MA) was estimated using generated plasma concentration-time and plasma concentration-effect curves. The degree of counter-clockwise hysteresis increases as the agonistic metabolite accumulates [as elimination rate of the metabolite (kmo) decreases and is not formation rate limited]. Furthermore, the degree of hysteresis is also reflective of the potency of the parent compound and agonist metabolite MA since as the ratio of potency parent compound/agonist metabolite decreases in magnitude (potency of agonist metabolite increases), the degree of hysteresis will increase.

Indirect Physiological Response

Often drugs act via an indirect mechanism of action and the pharmacologic effect takes considerable time to become evident as concentrations of drug are decreasing. Response is governed by the stimulation or inhibition of factors which can modulate the response [320]. There are two indirect situations following drug administration where the response measured when related to drug concentrations will produce a counter-clockwise hysteresis. Counter-clockwise hysteresis occurs when input is stimulated (i.e. stimulating the release of an endogenous physiological factor) or the output is inhibited (inhibiting or degrading the release of an endogenous physiological factor). For example stimulation of insulin or prolactin leads to a counter-clockwise hysteresis and the inhibition of anticholinesterase or diuresis leads to a counter-clockwise hysteresis [321–330] Terbutaline is a bronchodilator that increases cyclic AMP this in turn leads to bronchial smooth muscle dilation. Pyridostigmine and other agents inhibit cholinesterase preserving acetylcholine leading to an increase in muscular activity leading to a gain in muscular response. An indirect response can result in counter-clockwise hysteresis [321–323].

CLOCKWISE HYSTERESIS

A clockwise hysteresis loop may signify a decreasing pharmacological effect compared with earlier temporal pharmacological effects obtained with the same drug concentration. There are a variety of examples in the literature that suggest this type of pharmacokinetic/ pharmacodynamic relationship as reported in Table 3 [80–102, 313–317, and 330]. A clockwise hysteresis may mechanistically manifest due to a variety of underlying mechanisms as discussed below.

Venous vs Arterial Blood Concentrations

Drug concentration is often measured in venous blood sampling sites and the site of effect equilibrates with arterial concentrations at different rates. When the effect site (i.e. the brain or heart, etc.) concentration at the receptor site (leading to drug effect) equilibrates faster with arterial concentration than forearm venous blood concentration, clockwise hysteresis may occur.

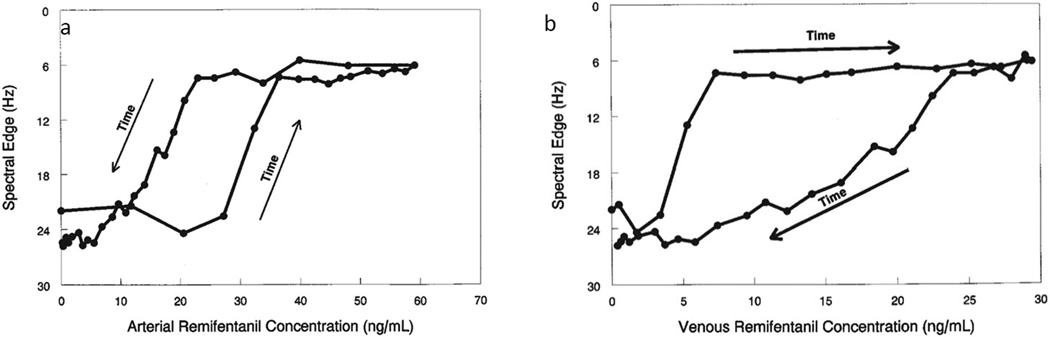

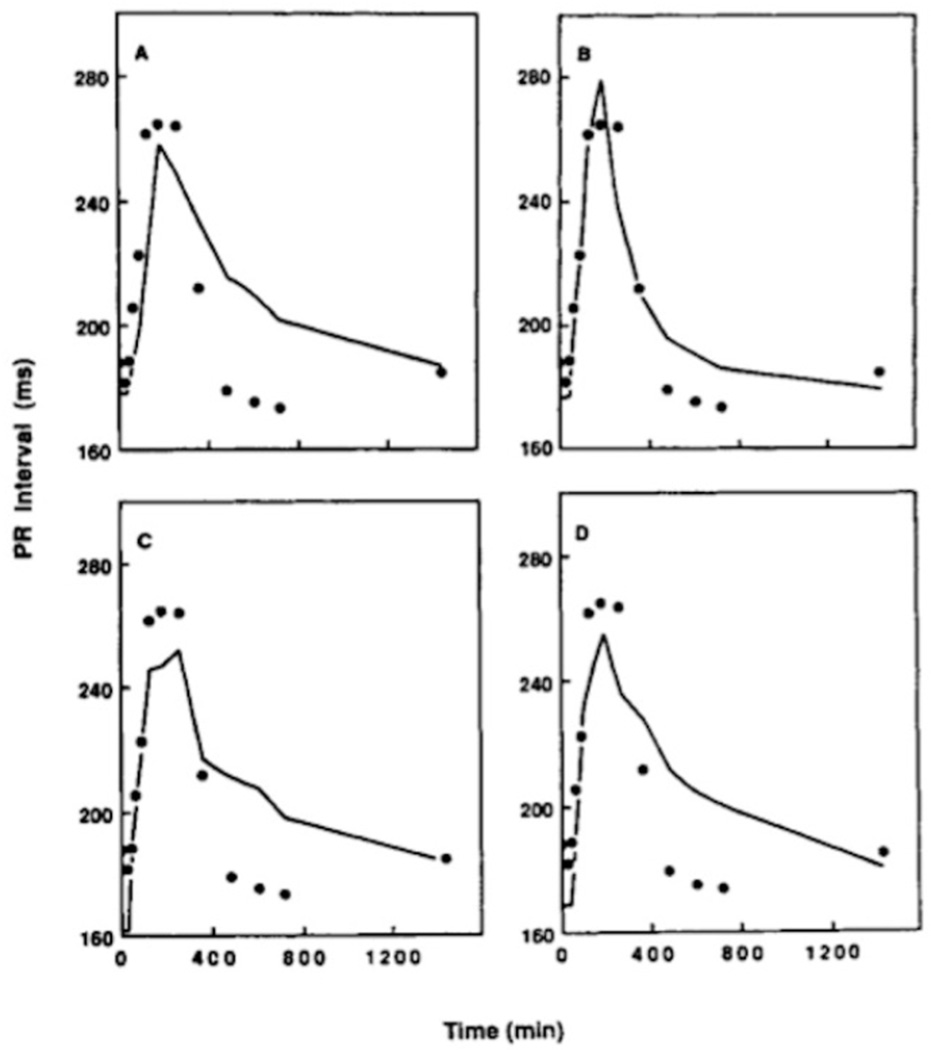

In the case of the opioid remifentanil after IV infusion (3 µg/kg/min for 10 min), it was observed that as opioid concentration increases the spectral edge decreases in the form of counter-clockwise hysteresis as a result of an equilibrium delay between arterial remifentanil concentration and the site of action (brain) (Figure 6a) [69]. However, a significant difference in arteriovenous concentrations in healthy subjects was reported and the direction of the hysteresis loop was reversed in venous drug concentrations (Figure 6b) and it was determined that the venous concentration lag behind the drug effect (clockwise hysteresis) [69]. It was suggested that the arterial drug concentration and effect site reach equilibration faster than the equilibration between arterial and venous concentration [69,103–106].

Figure 6.

(a) Opioid effect plotted against arterial remifentanil concentration from a representative subject (subject 12). Note the counter-clockwise direction of the hysteresis loop. (b) Opioid effect plotted against venous remifentanil concentration from a representative subject (subject 12). Note the clockwise direction of the hysteresis loop. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics, [69], copyright 1999.

Tolerance (Down Regulation of Receptors)

Tolerance is a time-dependent loss of intrinsic activity that can occur within the time course of a single dose, and is called acute tolerance or tachyphylaxis. In the case of pharmacodynamic tolerance intrinsic responsivity of the receptor diminishes over time. Many drugs present clockwise hysteresis due to tolerance because they present a reduced pharmacological effect at the same concentration than earlier leading to an increased effect [140–145]. After oral administration of the benzodiazepine diazepam (0.28 mg/kg) clockwise hysteresis was observed between tracking or digit-symbol substitution impairment and unbound diazepam concentrations relative to receptor occupancy [85]. Acute tolerance to the psychomotor effects of other benzodiazepines like alprazolam [146,147], midazolam [148], and triazolam [149] has been reported. However, it needs to be acknowledged that the actual mechanism of tolerance development to benzodiazepines is poorly understood [81]. There is no consensus delineating the actual mechanism but there are reports that consider that a decrease in binding potential and/or decrease in receptor functionality could explain the appearance of tolerance [150]. However, other mechanisms such as desensitization associated with receptor phosphorylation, uncoupling, and protein internalization or degradation have been proposed [151].