Abstract

Background and Aims Stresses such as drought or salinity induce the generation of reactive oxygen species, which subsequently cause excessive accumulation of aldehydes in plant cells. Aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDHs) are considered as ‘aldehyde scavengers’ to eliminate toxic aldehydes caused by oxidative stress. The completion of the genome sequencing projects of the halophytes Eutrema parvulum and E. salsugineum has paved the way to explore the relationships and the roles of ALDH genes in the glycophyte Arabidopsis thaliana and halophyte model plants.

Methods Protein sequences of all plant ALDH families were used as queries to search E. parvulum and E. salsugineum genome databases. Evolutionary analyses compared the phylogenetic relationships of ALDHs from A. thaliana and Eutrema. Expression patterns of several stress-associated ALDH genes were investigated under different salt conditions using reverse transcription–PCR. Putative cis-elements in the promoters of ALDH10A8 from A. thaliana and E. salsugineum were compared in silico.

Key Results Sixteen and 17 members of ten ALDH families were identified from E. parvulum and E. salsugineum genomes, respectively. Phylogenetic analysis of ALDH protein sequences indicated that Eutrema ALDHs are closely related to those of Arabidopsis, and members within these species possess nearly identical exon–intron structures. Gene expression analysis under different salt conditions showed that most of the ALDH genes have similar expression profiles in Arabidopsis and E. salsugineum, except for ALDH7B4 and ALDH10A8. In silico analysis of promoter regions of ALDH10A8 revealed different distributions of cis-elements in E. salsugineum and Arabidopsis.

Conclusions Genomic organization, copy number, sub-cellular localization and expression profiles of ALDH genes are conserved in Arabidopsis, E. parvulum and E. salsugineum. The different expression patterns of ALDH7B4 and ALDH10A8 in Arabidopsis and E. salsugineum suggest that E. salsugineum uses modified regulatory pathways, which may contribute to salinity tolerance.

Keywords: Aldehyde dehydrogenases, ALDH, Arabidopsis thaliana, Eutrema parvulum, Eutrema salsugineum, genome comparisons, glycophyte, halophytes, oxidative stress, ROS, salinity stress, saline adaptation

INTRODUCTION

Environmental stresses such as drought and high salinity induce the rapid generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which subsequently cause excessive accumulation of aldehydes in plant cells. Aldehydes are also intermediates in a range of metabolic pathways, but excessive amounts of aldehydes interfere with metabolism and can become toxic (Jakobyz and Ziegler, 1990; Lindahl, 1992; Bartels, 2001). Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) enzymes contribute to aldehyde homeostasis and are considered to be ‘aldehyde scavengers’ to eliminate toxic aldehydes (Sunkar et al., 2003; Rodrigues et al., 2006). The ALDH superfamily comprises a group of NAD(P)+-dependent enzymes that metabolize a wide range of endogenous and exogenous aliphatic and aromatic aldehyde molecules by oxidation to their corresponding carboxylic acids (Lindahl, 1992; Yoshida et al., 1998). In addition to acting as aldehyde scavengers, ALDHs are involved in a broad range of metabolic functions including participating in intermediary metabolism such as amino acid and retinoic acid metabolism or generating osmoprotectants, such as glycine betaine (Ishitani et al., 1995; Xing and Rajashekar, 2001). Aldehyde dehydrogenase enzymes produce NADPH and NADH in their enzymatic reactions and thus may contribute to balancing redox equivalents.

Aldehyde dehydrogenases are found throughout all taxa and have been classified into 24 distinct families based on protein sequence identities. These families are numbered according to the criteria from the ALDH Gene Nomenclature Committee (AGNC) (Vasiliou et al., 1999). The plant ALDH superfamily contains 14 distinct families: ALDH2, ALDH3, ALDH5, ALDH6, ALDH7, ALDH10, ALDH11, ALDH12, ALDH18, ALDH19, ALDH21, ALDH22, ALDH23 and ALDH24. The families ALDH10, ALDH12, ALDH19, ALDH21, ALDH22, ALDH23 and ALDH24 are specific to plants, whereas the remaining families have mammalian orthologues (Table 1). There are a few ALDH genes identified in algae species: seven ALDH genes in the colonial algae Volvox carteri (Brocker et al., 2013), and six and nine ALDH genes in the unicellular algae Ostreococcus tauri and Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, respectively (Wood and Duff, 2009). The ALDH gene numbers increased in the moss Physcomitrella patens, which contains 21 members including all plant ALDH gene families except for ALDH22 (Wood and Duff, 2009). Physcomitrella patens has gained two novel gene families, ALDH21 and ALDH23, and displays an increase in genes in the ALDH3 and ALDH11 gene families. The expansion of the ALDH genes in bryophytes such as P. patens may be related to the transition from aquatic to amphibious life. Structural and developmental complexity increases and additional protection may be needed against environmental stresses encountered during the transition (Cronk, 2001). When plants completed their life cycles on land, many genes associated with aquatic life were lost, and genes required for adaptation to terrestrial stressors were expanded. Gene loss or expansion also occurred in the ALDH superfamily. Green plants have retained nine ALDH family members from lower plants encompassing ALDH2, ALDH3, ALDH5, ALDH6, ALDH10, ALDH11, ALDH12, ALDH18 and ALDH22. Although the ALDH7 genes are widely present in plants and animals and are highly conserved throughout evolution, they are not reported in the analysed algae (Wood and Duff, 2009; Brocker et al., 2013). The ALDH21, ALDH23 and ALDH24 protein families are present in C. reinhardtii or P. patens, but have been lost in many vascular plants. So far, only in tomato has a single gene of the ALDH19 family been identified, and it encodes a γ-glutamyl phosphate reductase involved in proline biosynthesis (García-Ríos et al., 1997). Other ALDH19 genes have not been reported in higher plants.

Table 1.

Number of ALDH family members identified in representative species

| Taxonomy | Species | ALDH family |

Total no. | References | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | ||||

| Herbaceous dicotyledon | A. thaliana | – | 3 | 3 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | – | 2 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 16 | Kirch et al. (2004) |

| Herbaceous dicotyledon | E. parvulum | – | 3 | 3 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | – | 2 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 16 | This review |

| Herbaceous dicotyledon | E. salsugineum | – | 3 | 4 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | – | 2 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 17 | This review |

| Herbaceous dicotyledon | G. max | – | 5 | 1 | – | – | – | 4 | – | – | 6 | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 18 | Kotchoni et al. (2012) |

| Herbaceous monocotyledon | O. sativa | – | 5 | 5 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | – | 2 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 20 | Gao and Han (2009) |

| Herbaceous monocotyledon | Z. mays | – | 6 | 5 | – | 2 | 1 | 1 | – | – | 3 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 23 | Jimenez-Lopez et al. (2010); Zhou et al. (2012) |

| Herbaceous monocotyledon | S. bicolor | – | 5 | 4 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | – | 2 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 19 | Sophos and Vasiliou (2003); Brocker et al. (2013) |

| Woody plant | V. vinifera | – | 5 | 4 | – | 3 | 3 | 2 | – | – | 2 | 2 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 25 | Zhang et al. (2012) |

| Woody plant | M. domestica | – | 13 | 7 | – | 2 | 2 | 2 | – | – | 2 | 3 | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | 4 | – | – | – | 2 | – | – | 39 | Li et al. (2013) |

| Woody plant | P. trichocarpa | – | 4 | 6 | – | 1 | 4 | 2 | – | – | 2 | 3 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 26 | Brocker et al. (2013) |

| Fern | S. moellendorffii | – | 6 | 2 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | – | 1 | 6 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 1 | 1 | 2 | – | 24 | Brocker et al. (2013) |

| Moss | P. patens | – | 2 | 5 | – | 2 | 1 | 1 | – | – | 1 | 5 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | 1 | – | 21 | Wood and Duff (2009) |

| Algae | O. tauri | – | – | 1 | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 6 | Wood and Duff (2009) |

| Algae | C. reinhardtii | – | 1 | – | – | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | – | 1 | 9 | Wood and Duff (2009) |

| Algae | V. carteri | – | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 7 | Brocker et al. (2013) |

| Mammal | H. sapiens | 6 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 19 | Yoshida et al. (1998); Jackson et al. (2011) |

| Mammal | M. musculus | 7 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 21 | Jackson et al. (2011) |

‘–’ no member of the ALDH gene family was identified in the corresponding species.

Most of the studied plant ALDH genes are expressed in response to high salinity, dehydration, heat, water logging, oxidative stress or heavy metals (Sunkar et al., 2003; Kirch et al., 2005; Gao and Han, 2009), suggesting important roles in environmental adaptation. Several studies have demonstrated that ectopic overexpression of ALDH genes enhances plant tolerance to abiotic stress (Sunkar et al., 2003; Kotchoni et al., 2006; Rodrigues et al., 2006). Besides the ALDH superfamily in the genetic model plant Arabidopsis thaliana (Kirch et al., 2004), ALDH gene families from several plant species have been reviewed (Brocker et al., 2013); these include the algae C. reinhardtii and O. tauri, the moss P. patens (Wood and Duff, 2009) and the vascular plants rice (Gao and Han, 2009), maize (Jimenez-Lopez et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2012), soybean (Kotchoni et al., 2012), grape (Zhang et al., 2012) and apple (Li et al. 2013). No report is available for stress model plants.

Eutrema parvulum or Schrenkiella parvula (formerly known as Thellungiella parvula) and Eutrema salsugineum (formerly known as Thellungiella salsuginea or Thellungiella halophila) belong to the Brassicaceae family and are close relatives of A. thaliana. Older studies on taxonomic diversity, phylogeny and geographic distribution of the Eutrema species have been neglected and caused some confusion over the species' names in some publications. We use the names Eutrema parvulum and Eutrema salsugineum which are currently used in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) despite the fact that German and Al-Shehbaz (2010) suggested Schrenkiella parvula as a new name for Eutrema parvulum (German and Al-Shehbaz, 2010).

Eutrema parvulum and E. salsugineum are halophytes and tolerate high salt concentrations (Inan et al., 2004; Orsini et al., 2010). They are excellent models for revealing the mechanisms of abiotic stress tolerance because they have a short life cycle, are self-fertile, have a small genome and good seed production, and are genetically transformable. Because of these characters, Eutrema species were recommended as halophyte model plants a decade ago (Zhu, 2001). The availability of the genome sequences allows comparative analyses between these species which have a close phylogenetic relationship but with extremely divergent adaptations. The E. salsugineum and E. parvulum genome is approx. 50 and 15 % larger than that of A. thaliana, respectively. The higher content of transposable elements in E. salsugenium is the main reason for its genome expansion besides tandem duplications of single-copy genes. Comparative genomic analysis showed that A. thaliana and E. salsugineum share 95·2 and 93·7 % of all their gene families, respectively (Wu et al., 2012).

We carried out a genome-wide identification of ALDH genes, to study their evolutionary relationships and to investigate their expression profiles in response to stress. Comparing Eutrema and A. thaliana should provide us with some insight into the role of ALDH in abiotic stress tolerance. By searching public databases, we identified 16 ALDH genes from E. parvulum and 17 from E. salsugineum. ALDH genes from both species have been classified and have been assigned to ten subfamilies. We further surveyed genomic organization, sequence homology and subcellular localization of Eutrema ALDH genes. Expression profiles of stress-related ALDH genes were compared between A. thaliana and E. salsugineum under salinity stress conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Database searches and annotation of ALDH genes

The protein databases of Eutrema parvulum were searched in Thellungiella (http://thellungiella.org/) with BLASTP, and of Eutrema salsugineum in Phytozome (http://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/) with TBALSTN. The following ALDH protein sequences were used as queries for the searches: 16 A. thaliana ALDHs (ALDH2B4, ALDH2B7, ALDH2C4, ALDH3H1, ALDH3I1, ALDH3F1, ALDH5F1, ALDH6B2, ALDH7B4, ALDH10A8, ALDH10A9, ALDH11A3, ALDH12A1, ALDH18B1, ALDH18B2 and ALDH22A1), three Selaginella moellindorffii ALDHs (ALDH21A1, ALDH23B1 and ALDH23B2), one Solanum lycopersicum ALDH (ALDH19) and one Chlamydomonas reinhardtii ALDH (ALDH24A1). In addition, the same queries were used to search against the E. salsugineum protein database obtained from the website http://omicslab.genetics.ac.cn/resources.php with BLASTP by using the perfectBLAST2.0 program (Santiago-Sotelo and Ramirez-Prado, 2012). All sequences with an E-value <1e-6 were selected for manual inspection. The Pfam domain PF00171 (ALDH family), PF00070 (ALDH cysteine active site) and PF00687 (ALDH glutamic acid active site) searches (http://pfam.xfam.org/) were performed to confirm the candidate sequences as ALDH proteins. The confirmed Eutrema ALDH proteins were annotated using the criteria established by the AGNC (Vasiliou et al., 1999). Amino acid sequences that are >40 % identical to identified ALDH sequences comprise a family, and sequences that are >60 % identical comprise a protein subfamily, while sequences with <40 % identity are considered to be a new family.

Sequence alignments and phylogenetic analyses

Multiple protein alignments of ALDH protein sequences from A. thaliana, E. parvulum and E. salsugineum were performed using the ClustalW program of MEGA5·0 (Tamura et al., 2011). The phylogenetic tree was constructed in MEGA5·0 using the Neighbor–Joining method and the bootstrap test was replicated 500 times.

Exon–intron structure analyses of ALDH genes

The exon–intron structures of ALDH genes were determined from the alignments of the coding sequences to the corresponding genomic sequences using the program Spidey in NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/spidey/). The diagrams of exon–intron structures were obtained using the program FancyGene (Rambaldi and Ciccarelli, 2009).

Prediction of transcription factor binding sites

Nucleotides –1000 to +200 relative to the transcription start site of the AtALDH10A8 and EsALDH10A8 genes were retrieved from the Phytozome v10 database (http://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/) and taken as promoter sequences. The promoter sequences were scanned using the MATCH program of the TRANSFAC® Professional Suite subscribed from BIOBASE (http://www.biobase-international.com).

Plant materials, growth conditions and treatments

Arabidopsis thaliana (Col-0) and E. salsugineum (Shandong) were used for all experiments. Seeds for Arabidopsis were obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre, UK. Seeds for E. salsugineum were originally obtained from R. Bressan (Purdue University, USA). Seeds were germinated and plants were grown in plastic pots containing potting soil under 120–150 μE m–2 s–1 light at 22 °C with a day/night cycle of 8/16 h. Six-week-old Arabidopsis and E. salsugineum plants were regularly irrigated with NaCl solutions (100, 300 or 600 mm NaCl) for 5 d while well-watered plants served as controls. Leaves were collected 2 and 5 d after starting irrigation with NaCl. All samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80 °C until further analyses.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription–PCT (RT–PCR) analysis

Total RNA extraction was performed according to Valenzuela-Avendaño et al. (2005). For RT–PCR analyses, 2 μg of total RNAs were treated with 10 U of RNase-free DNase I (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) in a 10 μL reaction containing 1 × DNase I buffer (20 mm Tris–HCl pH 8·4, 50 mm KCl and 2 m,M MgCl2) at 37 °C for 30 min. Then, 1 μL of 25 mm EDTA was added and the reaction was heated at 65 °C for 15 min to deactivate the DNase I. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using the RevertAid™ H Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas, Burlington, Canada) following the protocol provided by the supplier.

RESULTS

Genome-wide identification of ALDH gene families in the Eutrema halophytes

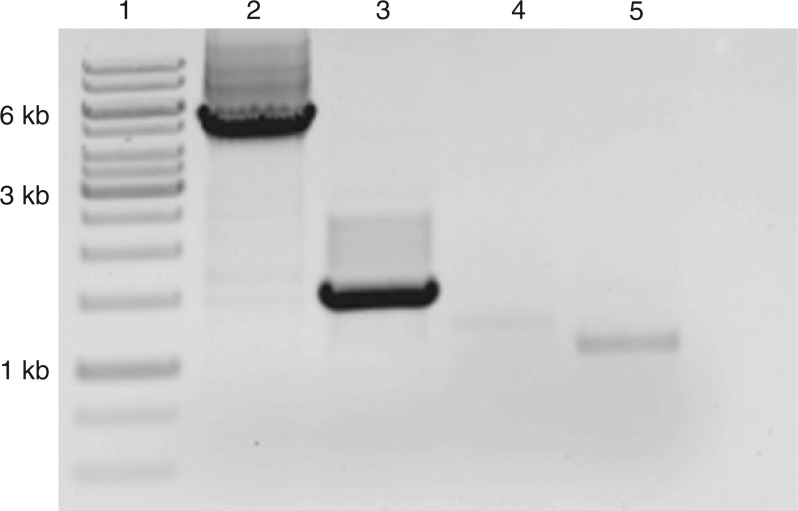

Here, we identified 16 ALDH genes from E. parvulum using the available genome sequence (Tables 1 and 2). In the case of E. salsugineum, the same ecotype (ecotype: Shandong) had been sequenced twice by two different groups (Wu et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2013). When ALDH genes were identified from the two genome datasets, different results were obtained. Seventeen putative ALDH genes were identified from the dataset of Yang et al. (2013) and 19 putative ALDH genes were identified from the dataset of Wu et al. (2012). The datasets differ in three putative orthologues of ALDH2C4 which are designated as Ts3g24340, Ts5g11880 and Ts5g11870 in the dataset of Wu et al. (2012) and only one orthologue found in the dataset of Yang et al. (2013) and designated as Thhalv10002492 m in Phytozome. The discrepancy is most probably due to an assembly error. The question was experimentally addressed by amplifying the ALDH2C4 gene from genomic DNA and cDNA of E. salsugineum. Only one amplicon was obtained from genomic DNA but three different fragments were amplified from cDNA. These results demonstrate that there is one orthologue of ALDH2C4 in the E. salsugineum genome, which generates three different transcripts most probably by alternative splicing. The existence of the transcripts was verified in RT–PCRs (Fig. 1). All transcripts are constitutively expressed and the expression does not change under different salt conditions. The EsALDH2C4.1 transcript is abundantly expressed and transcripts EsALDH2C4.2 and EsALDH2C4.3 are only weakly expressed (Figs 1 and 4).

Table 2.

ALDH genes in Arabidopsis, E. parvulum and E. salsugineum

| Arabidopsis (119.67Mb*) |

E. parvulum (137·07 Mb*) |

E. salsugineum (231·89 Mb*) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene name | Accession no. | Locus | Length (aa)† | Gene name | Accession no. | Locus | Length (aa)† | Gene name | Accession no. | Locus | Phytozome ID | Length (aa)† |

| AtALDH2B4 | NP_190383.1 | AT3G48000 | 538 | EpALDH2B4 | AFAN01000020·1 | Tp5g13980 | 538 | EsALDH2B4 | XM_006404245.1 | Ts5g15070 | Thhalv10010271m | 538 |

| AtALDH2B7 | NP_564204.1 | AT1G23800 | 534 | EpALDH2B7 | AFAN01000001·1 | Tp1g21180 | 540 | EsALDH2B7 | XM_006415991.1 | Ts1g21300 | Thhalv10007303m | 541 |

| AtALDH2C4 | NP_566749.1 | AT3G24503 | 501 | EpALDH2C4 | AFAN01000010·1 | Tp3g22290 | 502 | EsALDH2C4 | XM_006418675.1 | Ts3g24340 | Thhalv10002492m | 500 |

| AtALDH3H1 | NP_175081.1 | AT1G44170 | 484 | EpALDH3H1 | AFAN01000005·1 | Tp1g33460 | 482 | EsALDH3H1 | XM_006393677.1 | Ts1g33100 | Thhalv10011438m | 483 |

| AtALDH3I1 | NP_567962.1 | AT4G34240 | 550 | EpALDH3I1 | AFAN01000039·1 | Tp7g32020 | 548 | EsALDH3I1 | XM_006412189.1 | Ts7g33420 | Thhalv10024844m | 547 |

| AtALDH3F1 | NP_195348.2 | AT4G36250 | 484 | EpALDH3F1 | AFAN01000040·1 | Tp7g33990 | 484 | EsALDH3F1 | XM_006411952.1 | Ts7g35460 | Thhalv10025045m | 485 |

| EsALDH3F2 | XM_006409133.1 | Ts3g33290 | Thhalv10022980m | 502 | ||||||||

| AtALDH5F1 | NP_178062.1 | AT1G79440 | 528 | EpALDH5F1 | AFAN01000027·1 | Tp5g34490 | 527 | EsALDH5F1 | XM_006389827.1 | Ts5g36850 | Thhalv10018394m | 527 |

| AtALDH6B2 | NP_179032.1 | AT2G14170 | 607 | EpALDH6B2 | AFAN01000013·1 | Tp3g27540 | 537 | EsALDH6B2 | XM_006409602.1 | Ts3g28400 | Thhalv10022637 m | 538 |

| AtALDH7B4 | NP_175812.1 | AT1G54100 | 508 | EpALDH7B4 | AFAN01000005·1 | Tp1g40550 | 508 | EsALDH7B4 | XM_006392654.1 | Ts1g42160 | Thhalv10011405m | 508 |

| PseudoEsALDH7B4 | AHIU01008199·1 | Ts4g13390 | scaffold_10: 4569302..4570132 | |||||||||

| AtALDH10A8 | NP_001185399.1 | AT1G74920 | 496 | EpALDH10A8 | AFAN01000027·1 | Tp5g30060 | 501 | EsALDH10A8 | XM_006390308.1 | Ts5g32510 | Thhalv10018437m | 502 |

| PseudoEsALDH10A8 | AHIU01013287·1 | Ts7g03810 | scaffold_14: 4330373..4330927 | |||||||||

| AtALDH10A9 | NP_190400.1 | AT3G48170 | 503 | EpALDH10A9 | AFAN01000020·1 | Tp5g13870 | 503 | EsALDH10A9 | XM_006404229.1 | Ts5g14910 | Thhalv10010305m | 504 |

| AtALDH11A3 | NP_001189589.1 | AT2G24270 | 496 | EpALDH11A3 | AFAN01000016·1 | Tp4g03260 | 503 | EsALDH11A3 | XM_006404869.1 | Ts4g04290 | Thhalv10000267m | 503‡ |

| AtALDH12A1 | NP_568955.1 | AT5G62530 | 556 | EpALDH12A1 | AFAN01000008·1 | Tp2g25700 | 556 | EsALDH12A1 | XM_006394321.1 | Ts2g30990 | Thhalv10003935m | 557 |

| AtALDH18B1 | NP_181510.1 | AT2G39800 | 717 | EpALDH18B1 | AFAN01000019·1 | Tp4g22080 | 717 | EsALDH18B1 | XM_006411149.1 | Ts4g25140 | Thhalv10016322 m | 716 |

| AtALDH18B2 | NP_191120.2 | AT3G55610 | 726 | EpALDH18B2 | AFAN01000020·1 | Tp5g06860 | 726 | EsALDH18B2 | XM_006403379.1 | Ts5g07350 | Thhalv10010150m | 733 |

| AtALDH22A1 | NP_974242.1 | AT3G66658 | 596 | EpALDH22A1 | AFAN01000009·1 | Tp3g05630 | 596 | EsALDH22A1 | XM_006407856.1 | Ts3g05680 | Thhalv10020345m | 596 |

*Genome size in mega bases.

†Length of the deduced amino acid sequence.

‡Length of the amino acid deduced from two datasets (see Supplementary Data Fig. S2).

Fig. 1.

Amplification of EsALDH2C4 from genomic DNA and cDNA using different primer combinations. Lane 1, molecular weight size marker; lane 2, EsALDH2C4 amplified from genomic DNA using the primer combination EsALDH2C4_fwd/EsALDH2C4_rev1; lanes 3–5, different EsALDH2C4 transcripts amplified from 6-week-old E. salsugineum leaf cDNA using the primer combinations EsALDH2C4_fwd/EsALDH2C4_rev1, EsALDH2C4_fwd/EsALDH2C4_rev2 and EsALDH2C4_fwd/ EsALDH2C4_rev3, respectively.

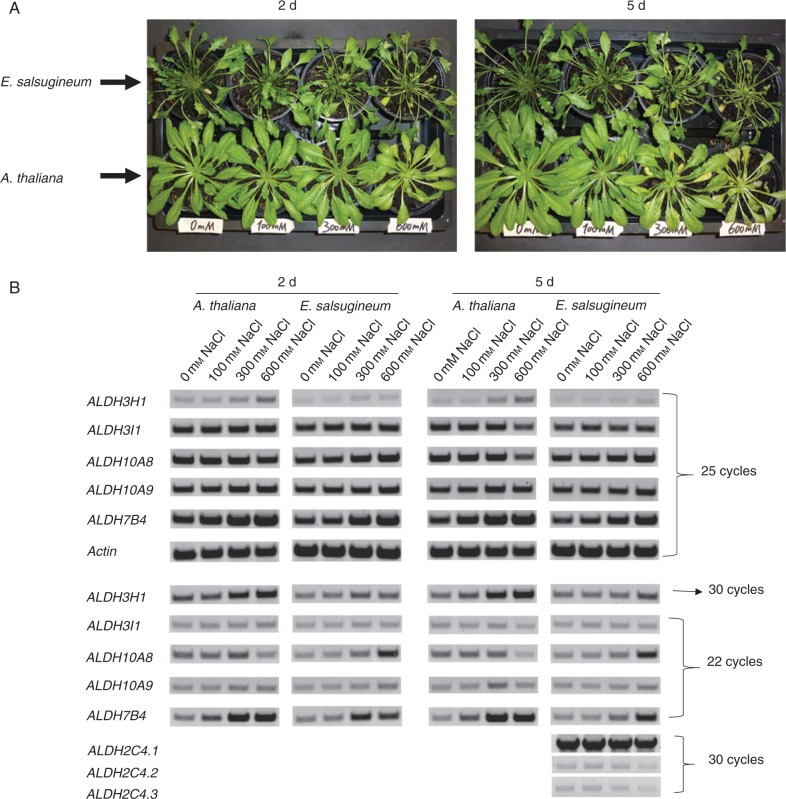

Fig. 4.

(A) Arabidopsis thaliana and E. salsugineum plants under different NaCl stress treatments. Six-week-old A. thaliana and E. salsugineum plants were treated with 100, 300 or 600 mm NaCl, while well-watered plants serve as controls. Photographs were taken 2 and 5 d after NaCl stress application. (B) Expression patterns of stress-associated ALDH genes from A. thaliana and E. salsugineum exposed to different NaCl treatments. Expression patterns of stress-associated ALDH3H1, ALDH3I1, ALDH7B4, ALDH10A8 and ALDH10A9 genes from A. thaliana and E. salsugineum were determined by reverse transcription–PCR analysis. Six-week-old A. thaliana and E. salsugineum plants were exposed to 100, 300 and 600 mm NaCl for 2 and 5 d. Leaf tissue was harvested and transcript abundances were determined using 22, 25 or 30 cycles for amplification. Actin was used as a reference gene to monitor the cDNA quality. Three different EsALDH2C4 transcripts were detected in samples of 5 d-treated E. salsugineum leaf samples after 30 cycles.

Although Ts3g24340 and Thhalv10002492 m which represent the EsALDH2C4 gene have the same DNA sequence in the two datasets, the protein sequences are not identical, because different open reading frames (ORF) were predicted from the two datasets. Our PCR analysis suggests that Thhalv10002492 m is the correct prediction as the corresponding transcript was detected from the cDNA whereas a fragment corresponding to Ts3g24340 could not be amplified. Similar ORF prediction discrepancies were observed for the orthologues of ALDH11A3 and ALDH12A1 in E. salsugineum which are designated as Ts4g04290, Ts2g30990 and Thhalv10000267 m, Thhalv10003935 m, respectively, in the two datasets.

In addition, two fragments were identified that resemble part of ALDH7B4 and ALDH10A8 but with stop codons designated as Ts4g13390 and Ts7g03810, respectively, in the genome dataset of Wu et al. (2012), but no annotation exists in the genome dataset of Yang et al. (2013). It was possible to amplify two cDNA fragments using Ts4g13390-specific primers. DNA sequencing analysis showed that the two transcripts were derived by alternative splicing, but no correct ORFs exist. Our results do not support the prediction of Wu et al. (2012) (Supplementary Data Fig. S1), and the two fragments with homologies to ALDH7B4 and ALDH10A8 are considered as pseudogenes.

Using the nomenclature criteria (Vasiliou et al., 1999), the ALDH proteins from the two Eutrema species fall into ten families based on their sequence identities. In both Eutrema species, six families are represented by a single gene (families 5, 6, 7, 11, 12 and 18), whereas the remaining four families contain multiple members (families 2, 3, 10 and 18). To classify the ALDH genes, a formal name was given for each ALDH gene of the two Eutrema species following the suggested nomenclature system (Table 2). Following the nomenclature criteria, sequences that share ≥60 % identity should be grouped into a subfamily (Vasiliou et al., 1999); therefore, the paralogue of EsALDH3F1 was designated as EsALDH3F2.

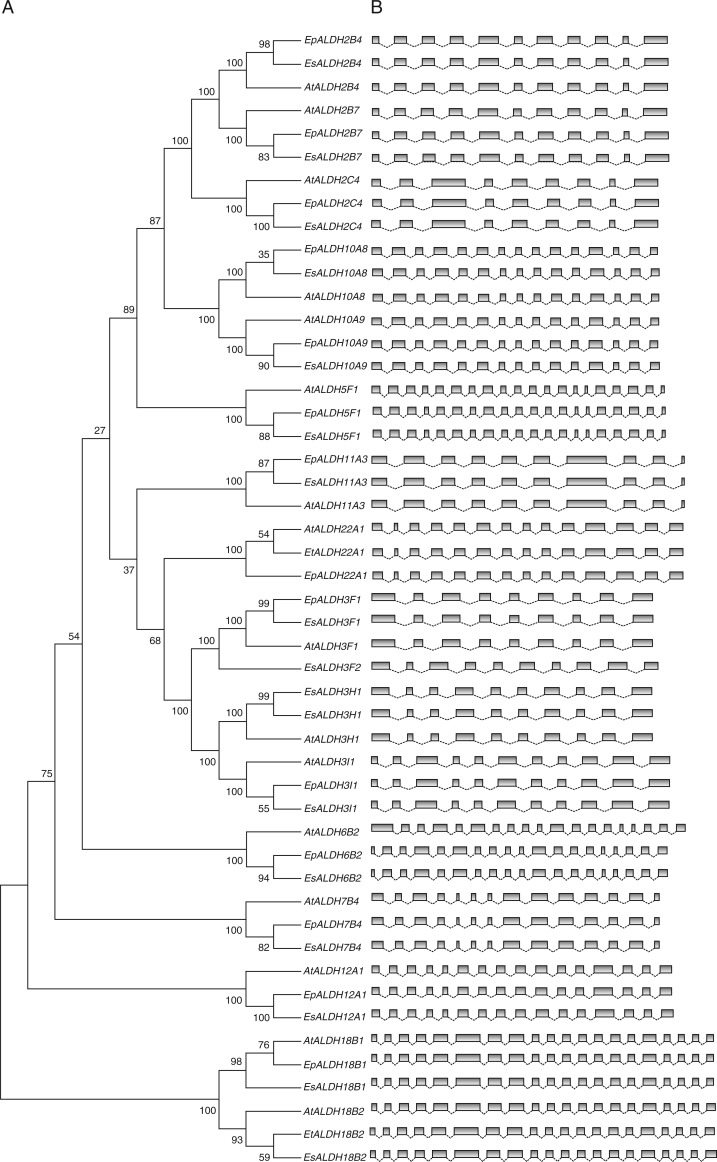

Evolutionary relationships of ALDH genes between Arabidopsis and Eutrema

As organisms evolve, the genetic materials accumulate mutations over time, causing phenotypic changes and speciation. Therefore, molecular phylogenetics is an informative way to reconstruct evolutionary history. To explore the function and evolutionary process of Eutrema ALDH genes, an unrooted phylogenetic tree was constructed from the alignment of full-length protein sequences with Arabidopsis. The two pseudogenes were excluded from the phylogenetic tree construction as they do not encode complete proteins. All of the EpALDHs, EsALDHs and AtALDHs fall into ten families with well-supported bootstrap values (Fig. 2A). The topology is similar to those trees which were constructed with ALDH proteins from other plant species. Families 2, 10 and 5 cluster together, and families 3 and 22 are connected by a node with a high bootstrap value, indicating a close evolutionary relationship among these families. Family 18 was excluded by several other studies because the genes encode bifunctional proteins which contain a glutamate 5-kinase signature (PS00902) in the N-terminal part and a gamma-glutamyl phosphate reductase signature (PS01223) in the C-terminal part instead of a common aldehyde dehydrogenases glutamic acid active site (PS00687) or cysteine active site signature (PS00070). Therefore, family 18 has a distant phylogenetic relationship with other ALDH families. The new family 3 member EsALDH3F2 generates a new branch on the tree and is separated from 3F1 with a high bootstrap value, indicating that this new gene already diverged from its homologue ALDH3F1.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis and exon–intron structures of A. thaliana, E. parvulum and E. salsugineum ALDH genes. (A) Multiple alignments of ALDH protein sequences from E. parvulum, E. salsugineum and A. thaliana were performed using the ClustalW program of the MEGA 5·0 software. The unrooted Neighbor–Joining tree was constructed with MEGA 5·0 software based on the alignments. Bootstrap values from 500 replicates are indicated at each branch. (B) Exon–intron structures of ALDH genes from A. thaliana, E. parvulum and E. salsugineum. Exons are represented by grey boxes and are drawn to scale by using FancyGene (http://bio.ieo.eu/fancygene/). Line angles connecting exon boxes represent introns and are not drawn to scale.

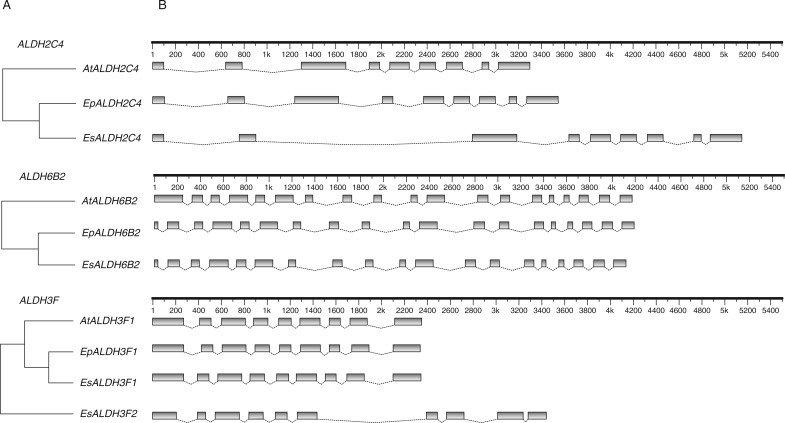

Exon–intron structural divergence plays a pivotal role in the evolution of multiple gene families. To obtain further insight into the evolutionary history of the Eutrema ALDH superfamily, a comparison of the full-length cDNA sequences with the corresponding genomic DNA sequences was made. As mentioned above, the ORF of EsALDH11A3 was predicted differently by the two available genome datasets. The exon–intron analysis showed that neither dataset predicts an exon–intron structure similar to the ORF of AtALDH11A3 and EpALDH11A3. In the dataset of Wu et al. (2012), the last exon is lost and the ORF in the dataset of Yang et al. (2013) has lost the first four exons (Supplementary Data Fig. S2). Thus, the exon–intron structure of EsALDH11A3 shown in Fig. 2 is the combination of the two predicted ORFs. Two more E. salsugineum ALDH genes, EsALDH2C4 and EsALDH12A1, show discrepancies with regards to the predicted ORFs between the two genome datasets. Here we used the predictions from the dataset of Yang et al. (2013) as this gives an exon–intron structure comparable with that of A. thaliana and E. parvulum. ALDH genes from the three species have the same exon numbers with nearly identical exon lengths (Fig. 2B), except for the first exon of Arabidopsis AtALDH6B2 which is longer than in the two Eutrema species (Fig. 3). Genes within the same subfamily such as subfamily ALDH2B, ALDH10A and ALDH18B show >60 % sequence identity and have the same exon–intron structure in all three species (Fig. 2B). The high degree of sequence identity and similar exon–intron structures of ALDH genes within each family suggest that gene duplications most probably occurred before A. thaliana and Eutrema were separated. In contrast to the ALDH superfamily in other analysed species (Gao and Han, 2009; Zhang et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2012), there is no intron loss in Eutrema, indicating a close evolutionary relationship between Arabidopsis and Eutrema. However, different intron lengths were observed in almost all families. Longer introns were found in several E. salsugineum ALDH genes, especially for EsALDH2C4 (Fig. 3). This finding is consistent with reports that E. salsugineum and A. thaliana genes have similar average exon lengths whereas the average intron length is about 30 % larger in E. salsugineum than in Arabidopsis (Wu et al., 2012). The new gene EsALDH3F2 has one more exon than its paralogue EsALDH3F1 and the orthologues AtALDH3F1 and EpALDH3F1, suggesting that EsALDH3F2 diverged from EsALDH3F1, which is consistent with the phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 2). The divergence in gene structure is mainly due to differences in intron sequences while the ALDH protein sequences are highly conserved in these three species, indicating that the enzymes kept their roles during evolution.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic relationship and exon–intron structures of three selected A. thaliana, E. parvulum and E. salsugineum ALDH genes. The genes ALDH2C4, ALDH6B2 and ALDH3F were selected for this analysis. (A) The phylogenetic relationship was constructed using MEGA 5.0. (B) Exons are represented by grey boxes and line angles connecting two boxes represent introns. The scale bars at the top are scaled by number of nucleotides. Exons and introns are drawn to scale by using FancyGene (http://bio.ieo.eu/fancygene/).

Expression profiles of stress-related ALDH genes from A. thaliana and E. salsugineum under salt stress conditions

Expression of the abiotic stress-related genes ALDH3H1, ALDH3I1, ALDH7B4 and two betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase genes ALDH10A8 and ALDH10A9 has been investigated in Arabidopsis (Kirch et al., 2005; Missihoun et al., 2010). To obtain information of these ALDH genes in halophytes, the expression was examined in response to salt stress in both A. thaliana and E. salsugineum after 2 and 5 d of salt treatments (Fig. 4A) using RT–PCR with a variable number of amplification cycles. First, expression was recorded by using 25 cycles, and then the cycle numbers were decreased from 25 to 22 for highly expressed transcripts and increased from 25 to 30 cycles for weakly expressed transcripts (Fig. 4B).

Under the salt treatments used here, ALDH3I1 transcripts were constitutively expressed in Arabidopsis and Eutrema; this result is different from those of other reports (Kirch et al., 2005; Kotchoni et al., 2006). ALDH3H1 shows the lowest expression of all examined transcripts and it is induced at high salt concentrations in Arabidopsis and Eutrema, with a slightly lower level in Eutrema (Fig. 4B). ALDH7B4 accumulates in response to salt similarly to ALDH3H1, but it is more abundant than ALDH3H1. Expression of ALDH7B4 is induced by salt in Arabidopsis and Eutrema, but the induction is delayed and at a lower level in Eutrema (Fig. 4B).

Under the stress conditions used here, ALDH10A9 is constitutively expressed in both A. thaliana and E. salsugineum, although it was reported to be weakly induced by different abiotic stressors (Missihoun et al., 2010). ALDH10A8 shows a differential accumulation in A. thaliana and E. salsugineum. It was constitutively expressed under low salt stress conditions in A. thaliana and downregulated in high salinity conditions, while it was upregulated in 600 mm NaCl in E. salsugineum.

Genomic organization and in silico comparison of putative promoter regions of the ALDH10A8 gene in A. thaliana and E.salsugineum

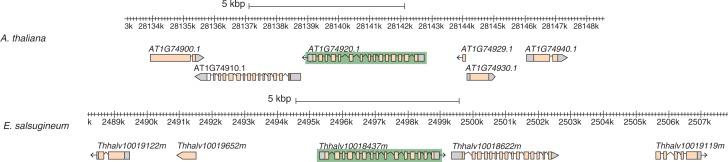

Because ALDH10A8 is differentially expressed in Arabidopsis and E. salsugineum, the gene organization and putative promoter regions were examined. Similar spatial organizations of the ALDH10A8 gene were found in the genome of the two species. The upstream and downstream neighbouring genes of the ALDH10A8 gene encode an ERF/AP2 transcription factor and a homologue of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase, respectively, in both species (Fig. 5). The intergenic region between ALDH10A8 and the upstream gene is much longer in E. salsugineum than in Arabidopsis, with 3959 and 1665 bp, respectively (Fig. 5). In A. thaliana, the intergenic region comprises the gene At1g74929 which encodes a putative protein of 33 amino acids. The sequence is very similar in Eutrema but the stop codon is absent (Supplementary Data Fig. S3A).

Fig. 5.

Genomic organization of ALDH10A8 and neighbouring genes in A. thaliana and E. salsugineum viewed in Gbrowse environment (http://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/). The ALDH10A8 genes are highlighted on a dark green background in the middle along with two 5′ and 3′ adjacent genes. Arrows indicate the 5′ and 3′ orientation of the genes.

To investigate whether sequence conservation exists in the promoter regions of ALDH10A8, the sequences of nucleotides –1000 to +200 relative to the transcription start site of the ALDH10A8 gene were compared in Arabidopsis and E. salsugineum. The sequences were retrieved from the Phytozome v10 database (http://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/) and aligned using the Align X tool of the Vector NTI Advance® 11 software. No regions were observed that are conserved between the two sequences (Supplementary Data Fig. S3B). Since ALDH10A8 showed different expression profiles in Arabidopsis and Eutrema under high salt concentrations (Fig. 4B), the 1000 bp promoter sequences upstream and 200 bp downstream of the transcription start site were scanned using the MATCH program of the TRANSFAC® Professional Suite to predict transcription factor binding sites and to compare their distribution in Arabidopsis and Eutrema. Forty-one transcription factor binding sites were predicted in the 1200 bp Arabidopsis sequence and 20 sites were predicted for the E. salsugineum promoter (Supplementary Data Fig. S4). Although identical sites are identified in both sequences (Fig. S4), the distribution is very different and no common promoter architecture can be predicted. The 1200 bp promoter sequence analysed here covers nearly the complete intergenic region between AtALDH10A8 and the upstream adjacent gene. However, E. salsugineum has a much longer intergenic region between EsALDH10A8 and the upstream adjacent gene. Therefore, there may be additional binding sites beyond the analysed 1200 bp. The non-conserved promoter region implies that AtALDH10A8 and EsALDH10A8 are probably regulated in different ways, which may explain why ALDH10A8 is differentially expressed in Arabidopsis and E. salsugineum under high salt concentrations.

Sub-cellular localization of ALDH proteins and overview of substrates used by ALDH enzymes

Aldehyde dehydrogenase enzymes are localized in different cellular compartments which may be correlated with functional specialization. We searched published data and used Euk-mPLoc 2·0 (Chou and Shen, 2010) to compile the subcellular localizations of the Arabidopsis and Eutrema ALDH proteins (Table 3).

Table 3.

ALDH protein sub-cellular localization and substrates used by the active enzymes

| Arabidopsis |

E. parvulum |

E. salsugineum |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein name | Localization | Substrates* | Protein name | Localization† | Protein name | Localization† |

| ALDH2B4 | Mitochondrion‡ | Acetaldehyde, glycolaldehyde§4 | ALDH2B4 | Mitochondrion | ALDH2B4 | Mitochondrion |

| ALDH2B7 | Mitochondrion‡ | Acetaldehyde, glycolaldehyde§4 | ALDH2B7 | Mitochondrion | ALDH2B7 | Mitochondrion |

| ALDH2C4 | Cytoplasm‡ | Acetaldehyde, glycolaldehyde l-lactaldehyde§4 | ALDH2C4 | Cytoplasm | ALDH2C4 | Cytoplasm |

| ALDH3H1 | Cytoplasm§1 | Medium to long-chain saturated aldehydes (C-6 to C-12)§1 | ALDH3H1 | Chloroplast | ALDH3H1 | Chloroplast |

| ALDH3I1 | Chloroplast§1 | Medium to long-chain saturated aldehydes (C-6 to C-12)§1 | ALDH3I1 | Chloroplast | ALDH3I1 | Chloroplast |

| ALDH3F1 | Cytoplasm§1 | Not determined | ALDH3F1 | Cytoplasm | ALDH3F1 | Cytoplasm |

| ALDH3F2 | Cytoplasm | |||||

| ALDH5F1 | Mitochondrion§2 | Succinic semialdehyde§5 | ALDH5F1 | Mitochondrion | ALDH5F1 | Mitochondrion |

| ALDH6B2 | Mitochondrion‡ | Methylmalonyl semialdehyde§5 | ALDH6B2 | Mitochondrion | ALDH6B2 | Mitochondrion |

| ALDH7B4 | Cytoplasm§1 | Acetaldehyde, glyceraldehyde, malondialdehyde, aminoadipic semialdehyde or guanidinobutyraldehyde§5 | ALDH7B4 | Cytoplasm | ALDH7B4 | Mitochondrion |

| ALDH10A8 | Leucoplast§1 | Not determined | ALDH10A8 | Chloroplast, mitochondrion, peroxisome | ALDH10A8 | Chloroplast, mitochondrion, peroxisome |

| ALDH10A9 | Peroxisome§1 | Betaine aldehyde, 4-aminobutanal, 3-aminopropanal§1 | ALDH10A9 | Chloroplast, mitochondrion, peroxisome | ALDH10A9 | Chloroplast, mitochondrion, peroxisome |

| ALDH11A3 | Cytoplasm‡ | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate§5 | ALDH11A3 | Cytoplasm | ALDH11A3 | Cytoplasm |

| ALDH12A1 | Mitochondrion§3 | Delta1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate§3 | ALDH12A1 | Mitochondrion | ALDH12A1 | Mitochondrion |

| ALDH18B1 | Mitochondrion inner membrane¶ | Gamma-glutamyl, glutamic acid-5-semialdehyde§5 | ALDH18B1 | Cytoplasm | ALDH18B1 | Cytoplasm |

| ALDH18B2 | Mitochondrion inner membrane¶ | Gamma-glutamyl, glutamic acid-5-semialdehyde§5 | ALDH18B2 | Cytoplasm | ALDH18B2 | Cytoplasm |

| ALDH22A1 | Cytoplasm§1 | Not determined | ALDH22A1 | Cytoplasm | ALDH22A1 | Cytoplasm |

*Substrates which have been reported for enzyme activities.

†Prediction according to Euk-mPLoc 2·0 (http://www.csbio.sjtu.edu.cn/bioinf/euk-multi-2/).

‡Information from UniProtKB (http://www.uniprot.org/).

§Experimentally confirmed. 1Stiti et al. (2011), 2Busch et al. (1999), 3Deuschle et al. (2001), 4Kirch et al. (2004), 5Brocker et al. (2013).

¶Information from human homologues.

According to predictions, ALDH2 (EC 1·2·1·3) family members are targeted to mitochondria and the cytoplasm (Skibbe et al., 2002; Kirch et al., 2004) which is consistent with human homologues (Braun et al., 1987). Arabidopsis and E. parvula as well as E. salsugineum contain two highly similar members of ALDH2B (ALDH2B4 and ALDH2B7) targeted to mitochondria, and ALDH2C4, a member of subfamily ALDH2C, is localized in the cytoplasm. In Arabidopsis, AtALDH2B4 was shown to be involved in the pyruvate dehydrogenase pathway (Wei et al., 2009). ALDH2C4 plays a role in ferulic and sinapic acid biosynthesis which are important compounds for maintaining cell wall strength (Nair et al., 2004). Kinetic studies of two maize enzymes ALDH2B2 and ALDH2B5 show that ALDH2B5 only oxidizes short-chain aliphatic aldehydes and ALDH2B2 oxidizes both aliphatic and aromatic aldehydes, indicating that ALDH2B2 has a broader substrate spectrum (Liu and Schnable, 2002; Jimenez-Lopez et al., 2010). Escherichia coli complementation assays showed that ALDH2C4 has a broader substrate spectrum than the two subfamily ALDH2B proteins, as ALDH2C4 oxidizes sinapaldehyde and coniferaldehyde as well as l-lactaldehyde, while ALDH2B does not use these substrates (Kirch et al., 2004; Nair et al., 2004).

ALDH3 (EC 1·2·1·5) proteins may have evolved as a consequence of functional specialization within specific tissues and sub-cellular organelles. An example are AtALDH3H1 and AtALDH3I1 proteins which are localized in the cytoplasm and in the chloroplast, respectively (Kotchoni et al., 2006; Stiti et al., 2011). Recombinant AtALDH3H1 and AtALDH3I1 enzymes both prefer medium to long-chain saturated aldehydes as substrates in enzymatic reactions (Stiti et al., 2011). However, ALDH3I1 can use both NADP+ and NAD+ as co-enzyme, whereas ALDH3H1 only uses NAD+ as co-enzyme due to an isoleucine instead of a valine in its co-enzyme binding site (Stiti et al., 2011). EsALDH3F1 and EpALDH3F1 and the new ALDH member EsALDH3F2 are predicted to localize to the cytoplasm, which is consistent with experimental data of the Arabidopsis orthologues (Stiti et al., 2011).

ALDH7, known as a Δ-1piperideine-6-carboxylate dehydrogenase (P6CDH; EC 1·2·1·31) or antiquitin, is highly conserved across all domains. Studies showed that it can metabolize various substrates such as acetaldehyde, glyceraldehyde and malondialdehyde in rice (Shin et al., 2008), or aminoadipic semialdehyde and guanidinobutyraldehyde in maize and pea (Brocker et al., 2013). The Arabidopsis enzyme is localized in the cytoplasm, which is consistent with the prediction for the E. parvulum homologue (Stiti et al., 2011). The homologue in E. salsugineum is predicted to target to mitochondria, however. Since ALDH7B is highly conserved throughout evolution, it will be interesting to investigate whether a minor sequence difference can change the localization from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria in E. salsugineum and whether this has any functional implications.

There are two members of the ALDH10 family in both Arabidopsis and Eutrema. They are known as aminoaldehyde dehydrogenases (AMADHs; EC 1·2·1·19) or betaine aldehyde dehydrogenases (BADHs; EC 1·2·1·9). Most of the members in this family show preference for aminoaldehyde substrates over betaine aldehyde. However, in vitro activity assays of recombinant ALDH10A9 exhibited both betaine aldehyde and aminoaldehyde dehydrogenase (4-aminobutanal and 3-aminopropanal) activities (Missihoun et al., 2010). It is not conclusive whether A. thaliana or E. salsugineum accumulate glycine betaine (Lugan et al., 2010; Chen and Murata, 2011); this suggests that ALDH10A8 and ALDH10A9 may be involved in as yet unknown metabolic pathways. In Arabidopsis, ALDH10A8 and ALDH10A9 proteins were shown to be localized in leucoplasts and peroxisomes, respectively (Missihoun et al., 2010).

The ALDH18 family contains Δ-1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase enzymes (P5CSs; EC 1·2·1·41 and EC 2·7·2·11). Gene expression is induced by dehydration and salt stress, and subsequently proline accumulates (Hu et al., 1992; Yoshiba et al., 1997). In mammals, ALDH18A1 converts glutamate to pyrroline-5-carboxylate, which is an intermediate in the biosynthesis of ornithine, proline and arginine (Hu et al., 1999; Marchitti et al., 2008). In plants, ALDH18B catalyses the first two steps in proline biosynthesis in moth bean (Vigna aconitifolia) (Hu et al., 1992). All plant species analysed contain two ALDH18 members which are predicted to be localized in the cytoplasm, while the human homologue is localized in the inner mitochondrial membrane.

The ALDH families 5, 6, 11, 12 and 22 are represented by one member in Arabidopsis and Eutrema. ALDH5F1, a succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH; EC 1·2·1·24), catalyses the conversion of succinic semialdehyde to succinate in γ-aminobutyrate (GABA) and may be involved in stress protection. ALDH6B2, a methylmalonyl semialdehyde dehydrogenase (MM-ALDH; EC 1·2·1·27), is involved in valine and pyrimidine catabolism and can catalyse CoA-dependent conversion of methylmalonyl semialdehyde to propionyl-CoA and of malonate semialdehyde to acetyl-CoA. ALDH11A3, a non-phosphorylating glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPN; EC 1·2·1·9), catalyses the irreversible NADP+-dependent oxidation of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate to 3-phosphoglycerate and NADPH, which is the main source for mannitol biosynthesis in many plant species (Valverde et al., 1999; Gao and Loescher, 2000). ALDH12A1, a Δ-1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase (P5CDH; EC 1·5·1·12), degrades the toxic proline intermediate Δ-1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate to glutamate. ALDH22A1, a plant-specific aldehyde dehydrogenase with an as yet unknown function is localized in the cytoplasm in Arabidopsis (Stiti et al., 2011) and in plastids in maize (Huang et al., 2008). In Arabidopsis, ALDH22A1 is constitutively expressed at a low level (Kirch et al., 2005), and in Z. mays it is induced by a variety of stressors (Huang et al., 2008). In Arabidopsis, ALDH5F1 and ALDH12A1 are targeted to mitochondria (Busch and Fromm, 1999; Deuschle et al., 2001), which is also predicted for the two Eutrema species. ALDH6B2 is predicted to localize in mitochondria and ALDH11A3 in the cytoplasm.

DISCUSSION

Arabidopsis is an excellent model to understand basic processes of flowering plants, but it is a stress-sensitive species. Therefore, Eutrema species as close relatives of Arabidopsis have been suggested as halophytic model species to understand adaptation mechanisms to high salinity (Bressan et al., 2001; Zhu, 2001; Amtmann et al., 2005). Recently the genome sequences of E. parvulum and E. salsugineum have become available, which facilitates gene discovery (Dassanayake et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2013). Dating analyses showed that E. salsugineum and E. parvulum diverged from each other about 38·4 million years ago, and both share a common ancestor with the Arabidopsis genus around 43·2 million years ago (Yang et al., 2013), indicating a closer relationship between E. salsugineum and E. parvulum than to Arabidopsis. The same relationship is reflected by the ALDH genes of the three species (Fig. 2). Sixteen and 17 genes encoding members of ten ALDH families were identified from E. parvulum and E. salsugineum, respectively (Tables 1 and 2). Eutrema parvulum has the same number of ALDH genes as Arabidopsis, while one more paralogue designated as EsALDH3F2 was identified in E. salsugineum. EsALDH3F2 has probably arisen by gene duplication after E. salsugineum, E. parvulum and Arabidopsis had split off. Additionally, two pseudogenes resembling ALDH7B4 and ALDH10A8 were identified in E. salsugineum. According to Wu et al. (2012), these pseudogenes are located on different chromosomes from their corresponding paralogues. It is possible that they resulted from ectopic recombination of repetitive elements such as transposable elements as the genome of E. salsugineum contains a high amount of repetitive sequences. Families 2, 5 and 10 are clustered together, which suggests that these families have probably derived from a common ancestor. ALDH18 which does not contain the conserved ALDH active site, is the most distantly related family, as already observed in other plant species.

Except for the ALDH family 3 in E. salsugineum, copy numbers are identical in Arabidopsis and the two Eutrema species. This is in contrast to HKT1 (sodium–potassium co-transporter) genes related to the maintenance of ion equilibrium. These gene families are expanded in Eutrema, with three HKT1 genes in E. salsugenium and two HKT1 genes in E. parvulum, while only one copy is present in Arabidopsis (Dassanayake et al., 2011; Ali et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2012). However, another comparative genomic study on copy numbers in families among all the functional categories including transcription factors and SOS-like genes found that Arabidopsis and E. salsugenium contain equal or near-equal numbers and, in most cases, Arabidopsis has more copies than E. salsugineum (Yang et al., 2013). ALDH7 family genes are considered as ancient genomic DNA sequences as they are broadly present in plants and animals and highly conserved throughout evolution. Unlike soybean and woody plants Vitis vinifera and Populus trichocarpa which contain multiple members in family 7, there is only one member in each of the two Eutrema species as in many other analysed plants. It is not clear why this family has been lost from both the marine unicellular algal species O. tauri and the freshwater unicellular algal species C. reinhardtii, and the multicellular species V. carteri (Wood and Duff, 2009; Brocker et al., 2013). It suggests that this family of proteins may play a fundamental role in land organisms but it is not necessary for aquatic algae.

The localization of ALDH in different cellular compartments has been demonstrated mainly in Arabidopsis. The differential localization indicates that ALDH members have acquired functional specialization during evolution and that different compartments require specific ALDH enzymes to oxidize aldehydes which are generated from different pathways. Except for EsALDH7B4, the same sub-cellular localizations were predicted for the ALDH of the two Eutrema species as for the corresponding Arabidopsis orthologues. This result was expected due to the high degree of conservation of the ALDH proteins in the three species.

High-throughput transcript analysis revealed that a number of universally stress-responsive genes are highly expressed in Eutrema even in the absence of challenges (Inan et al., 2004); therefore, expression of stress-associated ALDH genes was compared under different salinity conditions in A. thaliana and E. salsugineum. No such expression pattern was observed from the selected ALDH genes. Most ALDH genes have a similar expression pattern in Arabidopsis and E. salsugineum, indicating that most ALDH genes are probably not functionally connected with the salinity tolerance of E. salsugineum. However, the two salt-responsive transcripts ALDH3H1 and ALDH7B4 increased in response to higher NaCl levels in E. salsugineum than in Arabidopsis, indicating that higher NaCl levels are required in E. salsugineum than in Arabidopsis to trigger defence reactions. A differential expression profile was only observed for ALDH10A8, which is downregulated in A. thaliana under 600 mm NaCl stress but upregulated in E. salsugineum. This differential regulation is probably due to differences in the promoter structures in the two species, but the functional promoter elements need to be identified experimentally. A comparison of the ALDH7 promoter between A. thaliana and E. salsugineum also revealed a longer putative promoter region in E. salsugineum than in Arabidopsis, with several conserved blocks of functional promoter motifs in both species (Missihoun et al., 2014). Alterations in the sequences and cis-element structures of promoters for other orthologous genes have also been observed in these two species (Wu et al., 2012). Studies carried out so far indicate that genes involved in response to salinity are almost identical in Arabidopsis and in Eutrema halophytes (Zhu, 2000). This implies that the halophytic characteristics of E. salsugenium may be due to specific regulatory mechanisms rather than to increased copy numbers of genes. The analyses of the ALDH genes in Arabidopsis and Eutrema are in agreement with Zhu (2001) who hypothesized that halophytes generally use salt tolerance effectors and regulatory pathways similar to glycophytes and that subtle differences in regulation account for variations in tolerance or sensitivity. Nevertheless there are some potential orphan genes in the genome of the Eutrema halophytes which also may contribute to tolerance mechanisms.

Conclusions

The ALDH superfamily represents a group of NAD(P)+-dependent enzymes that catalyse the oxidation of endogenous and exogenous aromatic and aliphatic aldehydes to the corresponding carboxylic acids. Although ALDH gene families have been reviewed in many plants, no attention was paid to halophytes. In the present study, we identified 16 and 17 ALDH genes from the genomes of the halophyte models E. parvulum and E. salsugineum, respectively. Analyses demonstrate that genomic organization, copy number, sub-cellular localization and expression profiles of ALDH genes are fairly conserved in Arabidopsis, E. parvulum and E. salsugineum. Except for the expression of ALDH7B4, ALDH3H1 and ALDH10A8, no differences were observed which may contribute to salinity tolerance. Transcripts of ALDH3H1 and ALDH7B4 increased in response to NaCl at higher levels in E. salsugineum than in Arabidopsis. In addition, ALDH10A8 showed a different expression pattern under high salt in these two species. This indicates that regulation of transcription may be better adapted to high salt in E. salsugineum than in Arabidopsis.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org and consist of the following. Table S1: primer sequences used for reverse transcription–PCR of ALDH genes analysed from Arabidopsis and E. salsugineum. Figure S1: PCR products of the pseudogene ALDH7B4 on an agarose gel, and nucleotide sequence alignment. Figure S2: exon–intron structures of predicted EsALDH11A3 ORFs in different genome datasets. Figure S3: nucleotide sequence alignment of putative ALDH10A8 gene promoter regions from Arabidopsis and E. salsugineum. Figure S4: predicted transcription factor binding sites in the 1000 bp promoter sequences upstream and 200 bp downstream of the transcription start sites of AtALDH10A8 and EsALDH10A8. Figure S5: ALDH protein sequences from Arabidopsis, E. parvulum and E. salsugineum.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Q.H. acknowledges a fellowship from the China Scholarship Council (CSC). The work was supported by the European COST project FA0901 Putting Halophytes to work: from Genes to Ecosystems. We thank Magdalena Gruca for some initial analysis during a COST STSM fellowship, and Tagnon D. Missihoun for advice and discussions. Requests for materials should be addressed to the corresponding author.

LITERATURE CITED

- Ali Z, Park HC, Ali A, et al. TsHKT1;2, a HKT1 homolog from the extremophile arabidopsis relative Thellungiella salsuginea, shows K(+) specificity in the presence of NaCl. Plant Physiology. 2012;158:1463–1474. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.193110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amtmann A, Bohnert HJ, Bressan RA. Abiotic stress and plant genome evolution. Search for new models. Plant Physiology. 2005;138:127–130. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.059972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels D. Targeting detoxification pathways: an efficient approach to obtain plants with multiple stress tolerance. Trends in Plant Science. 2001;6:284–286. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(01)01983-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun T, Bober E, Singh S, Agarwal DP, Goedde HW. Evidence for a signal peptide at the amino-terminal end of human mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase. FEBS Letters. 1987;215:233–236. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressan RA, Zhang C, Zhang H, Hasegawa PM, Bohnert HJ, Zhu JK. Learning from the arabidopsis experience. The Next Gene Search Paradigm. Plant Physiology. 2001;127:1354–1360. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocker C, Vasiliou M, Carpenter S, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) superfamily in plants: gene nomenclature and comparative genomics. Planta. 2013;237:189–210. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1749-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch KB, Fromm H. Plant succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase. Cloning, purification, localization in mitochondria, and regulation by adenine nucleotides. Plant Physiology. 1999;121:589–597. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.2.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen THH, Murata N. Glycinebetaine protects plants against abiotic stress: mechanisms and biotechnological applications. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2011;34:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K-C, Shen H-B. A new method for predicting the subcellular localization of eukaryotic proteins with both single and multiple sites: Euk-mPLoc 2·0. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9931. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronk QCB. Plant evolution and development in a post-genomic context. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2001;2:607–619. doi: 10.1038/35084556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassanayake M, Oh D-H, Haas JS, et al. The genome of the extremophile crucifer Thellungiella parvula. Nature Genetics. 2011;43:913–918. doi: 10.1038/ng.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuschle K, Funck D, Hellmann H, Däschner K, Binder S, Frommer WB. A nuclear gene encoding mitochondrial Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase and its potential role in protection from proline toxicity. The Plant Journal. 2001;27:345–355. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao C, Han B. Evolutionary and expression study of the aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) gene superfamily in rice (Oryza sativa) Gene. 2009;431:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z, Loescher WH. NADPH supply and mannitol biosynthesis. Characterization, cloning, and regulation of the non-reversible glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in celery leaves. Plant Physiology. 2000;124:321–330. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.1.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Ríos M, Fujita T, LaRosa PC, et al. Cloning of a polycistronic cDNA from tomato encoding γ-glutamyl kinase and γ-glutamyl phosphate reductase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1997;94:8249–8254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German DA, Al-Shehbaz IA. Nomenclatural novelties in miscellaneous Asian Brassicaceae (Cruciferae) Nordic Journal of Botany. 2010;28:646–651. [Google Scholar]

- Hu C-A, Delauney AJ, Verm DPS. A bifunctional enzyme (delta 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase) catalyzes the first two steps in proline biosynthesis in plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1992;89:9354–9358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.9354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C-A, Lin W-W, Obie C, Valle D. Molecular enzymology of mammalian Delta 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase. Alternative splice donor utilization generates isoforms with different sensitivity to ornithine inhibition. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:6754–6762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Ma X, Wang Q, et al. Significant improvement of stress tolerance in tobacco plants by overexpressing a stress-responsive aldehyde dehydrogenase gene from maize (Zea mays) Plant Molecular Biology. 2008;68:451–463. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9382-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inan G, Zhang Q, Li P, et al. Salt cress. A halophyte and cryophyte arabidopsis relative model system and its applicability to molecular genetic analyses of growth and development of extremophiles. Plant Physiology. 2004;135:1718–1737. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.041723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishitani M, Nakamura T, Hart SY, Takabe T. Expression of the betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase gene in barley in response to osmotic stress and abscisic acid. Plant Molecular Biology. 1995;27:307–315. doi: 10.1007/BF00020185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson B, Brocker C, Thompson DC, et al. Update on the aldehyde dehydrogenase gene (ALDH) superfamily. Human Genomics. 2011;5:283–303. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-5-4-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobyz WB, Ziegler DM. The enzymes of detoxification. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265:20715–20719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Lopez JC, Gachomo EW, Seufferheld MJ, Kotchoni SO. The maize ALDH protein superfamily: linking structural features to functional specificities. BMC Structural Biology. 2010;10:43. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-10-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirch H-H, Bartels D, Wei Y, Schnable PS, Wood AJ. The ALDH gene superfamily of arabidopsis. Trends in Plant Science. 2004;9:371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirch H-H, Schlingensiepen S, Kotchoni S, Sunkar R, Bartels D. Detailed expression analysis of selected genes of the aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) gene superfamily in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Molecular Biology. 2005;57:315–332. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-7796-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotchoni SO, Kuhns C, Ditzer A, Kirch H-H, Bartels D. Over-expression of different aldehyde dehydrogenase genes in Arabidopsis thaliana confers tolerance to abiotic stress and protects plants against lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2006;29:1033–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotchoni SO, Jimenez-Lopez JC, Kayodé APP, Gachomo EW, Baba-Moussa L. The soybean aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) protein superfamily. Gene. 2012;495:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Guo R, Li J, et al. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) gene superfamily in apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.) Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2013;71:268–282. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl R. Aldehyde dehydrogenases and their role in carcinogenesis. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 1992;27:283–335. doi: 10.3109/10409239209082565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Schnable PS. Functional specialization of maize mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenases. Plant Physiology. 2002;130:1657–1674. doi: 10.1104/pp.012336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugan R, Niogret MF, Leport L, et al. Metabolome and water homeostasis analysis of Thellungiella salsuginea suggests that dehydration tolerance is a key response to osmotic stress in this halophyte. The Plant Journal. 2010;64:215–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchitti SA, Brocker C, Stagos D, Vasiliou V. Non-P450 aldehyde oxidizing enzymes: the aldehyde dehydrogenase superfamily. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism and Toxicology. 2008;4:697–720. doi: 10.1517/17425250802102627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missihoun TD, Schmitz J, Klug R, Kirch H-H, Bartels D. Betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase genes from arabidopsis with different sub-cellular localization affect stress responses. Planta. 2010;233:369–382. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1297-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missihoun TD, Hou Q, Mertens D, Bartels D. Sequence and functional analyses of the aldehyde dehydrogenase 7B4 gene promoter in Arabidopsis thaliana and selected Brassicaceae: regulation patterns in response to wounding and osmotic stress. Planta. 2014;239:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s00425-014-2051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair RB, Bastress KL, Ruegger MO, Denault JW, Chapple C. The Arabidopsis thaliana reduced epidermal fluorescence1 gene encodes an aldehyde dehydrogenase involved in ferulic acid and sinapic acid biosynthesis. The Plant Cell. 2004;16:544–554. doi: 10.1105/tpc.017509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsini F, D'Urzo MP, Inan G, et al. A comparative study of salt tolerance parameters in 11 wild relatives of Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2010;61:3787–3798. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaldi D, Ciccarelli FD. FancyGene: dynamic visualization of gene structures and protein domain architectures on genomic loci. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2281–2282. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues SM, Andrade MO, Gomes APS, DaMatta FM, Baracat-Pereira MC, Fontes EPB. Arabidopsis and tobacco plants ectopically expressing the soybean antiquitin-like ALDH7 gene display enhanced tolerance to drought, salinity, and oxidative stress. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2006;57:1909–1918. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago-Sotelo P, Ramirez-Prado JH. prfectBLAST: a platform-independent portable front end for the command terminal BLAST+ stand-alone suite. Biotechniques. 2012;53:299–300. doi: 10.2144/000113953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JH, Kim SR, An G. Rice aldehyde dehydrogenase7 is needed for seed maturation and viability. Plant Physiology. 2008;149:905–915. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.130716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skibbe DS, Liu F, Tsui-JungWen, et al. Characterization of the aldehyde dehydrogenase gene families of Zea mays and arabidopsis. Plant Molecular Biology. 2002;48:751–764. doi: 10.1023/a:1014870429630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sophos NA, Vasiliou V. Aldehyde dehydrogenase gene superfamily: the 2002 update. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2003;143–144:5–22. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(02)00163-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiti N, Missihoun TD, Kotchoni SO, Kirch H-H, Bartels D. Aldehyde dehydrogenases in Arabidopsis thaliana: biochemical requirements, metabolic pathways, and functional analysis. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2011;2:65. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2011.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunkar R, Bartels D, Kirch H-H. Overexpression of a stress-inducible aldehyde dehydrogenase gene from Arabidopsis thaliana in transgenic plants improves stress tolerance. The Plant Journal. 2003;35:452–464. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela-Avendaño J, Mota IE, Uc G, Perera R, Valenzuela-Soto E, Aguilar JZ. Use of a simple method to isolate intact RNA from partially hydrated Selaginella lepidophylla plants. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter. 2005;23:199–200. [Google Scholar]

- Valverde F, Losada M, Serrano A. Engineering a central metabolic pathway: glycolysis with no net phosphorylation in an Escherichia coli gap mutant complemented with a plant GapN gene. FEBS Letters. 1999;449:153–158. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00430-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasiliou V, Bairoch A, Tipton KF, Nebert DW. Eukaryotic aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) genes: human polymorphisms, and recommended nomenclature based on divergent evolution and chromosomal mapping. Pharmacogenetics. 1999;9:421–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Lin M, Oliver DJ, Schnable PS. The roles of aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDHs) in the PDH bypass of arabidopsis. BMC Biochemistry. 2009;10:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-10-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood AJ, Duff RJ. The aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) gene superfamily of the moss Physcomitrella patens and the algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Ostreococcus tauri. The Bryologist. 2009;112:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wu HJ, Zhang Z, Wang JY, et al. Insights into salt tolerance from the genome of Thellungiella salsuginea. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2012;109:12219–12224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209954109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing W, Rajashekar CB. Glycine betaine involvement in freezing tolerance and water stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2001;46:21–28. doi: 10.1016/s0098-8472(01)00078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R, Jarvis DE, Chen H, et al. The reference genome of the halophytic plant Eutrema salsugineum. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2013;4:46. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiba Y, Kiyosue T, Nakashima K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. Regulation of levels of proline as an osmolyte in plants under water stress. Plant and Cell Physiology. 1997;38:1095–1102. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida A, Rzhetsky A, Hsu LC, Chang C. Human aldehyde dehydrogenase gene family. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1998;251:549–557. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2510549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Mao L, Wang H, et al. Genome-wide identification and analysis of grape aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) gene superfamily. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M-L, Zhang Q, Zhou M, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase protein superfamily in maize. Functional and Integrative Genomics. 2012;12:683–691. doi: 10.1007/s10142-012-0290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J-K. Genetic analysis of plant salt tolerance using arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2000;124:941–948. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.3.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J-K. Plant salt tolerance. Trends in Plant Science. 2001;6:66–71. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01838-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.