Abstract

Background and Aims Halophytic eudicots are characterized by enhanced growth under saline conditions. This study combines physiological and anatomical analyses to identify processes underlying growth responses of the mangrove Avicennia marina to salinities ranging from fresh- to seawater conditions.

Methods Following pre-exhaustion of cotyledonary reserves under optimal conditions (i.e. 50 % seawater), seedlings of A. marina were grown hydroponically in dilutions of seawater amended with nutrients. Whole-plant growth characteristics were analysed in relation to dry mass accumulation and its allocation to different plant parts. Gas exchange characteristics and stable carbon isotopic composition of leaves were measured to evaluate water use in relation to carbon gain. Stem and leaf hydraulic anatomy were measured in relation to plant water use and growth.

Key Results Avicennia marina seedlings failed to grow in 0–5 % seawater, whereas maximal growth occurred in 50–75 % seawater. Relative growth rates were affected by changes in leaf area ratio (LAR) and net assimilation rate (NAR) along the salinity gradient, with NAR generally being more important. Gas exchange characteristics followed the same trends as plant growth, with assimilation rates and stomatal conductance being greatest in leaves grown in 50–75 % seawater. However, water use efficiency was maintained nearly constant across all salinities, consistent with carbon isotopic signatures. Anatomical studies revealed variation in rates of development and composition of hydraulic tissues that were consistent with salinity-dependent patterns in water use and growth, including a structural explanation for low stomatal conductance and growth under low salinity.

Conclusions The results identified stem and leaf transport systems as central to understanding the integrated growth responses to variation in salinity from fresh- to seawater conditions. Avicennia marina was revealed as an obligate halophyte, requiring saline conditions for development of the transport systems needed to sustain water use and carbon gain.

Keywords: Avicennia marina, mangrove, plant growth, salinity, hydraulic anatomy, obligate halophyte

INTRODUCTION

Mangrove is an ecological term for a diverse group of woody plant species that form the dominant vegetation in saline, tidal wetlands along tropical and subtropical coasts (Tomlinson, 1986). Salinity is one of the defining environmental features of mangrove habitats and ranges from seasonally freshwater to hypersaline conditions. Mangrove species are differentially distributed along these complex salinity gradients that vary in time and space. Like many other halophytic species (Flowers and Colmer, 2008), growth of mangroves is enhanced under saline conditions, but species differ in both the salinity that supports maximal growth and the range of salinities over which high growth rates are sustained (Ball, 1988b). Species also differ in the capacity for growth in freshwater, with some growing vigorously, such as Sonneratia lanceolata (Ball and Pidsley, 1995), while growth of others is severely inhibited, for example Rhizophora mangle (Werner and Stelzer, 1990). However, the existence of obligate halophytes among mangroves has been questioned because reports of mortality in freshwater are rare (Krauss and Ball, 2013).

What is the nature of variation in halophytic growth along a salinity gradient? Insight can be gained through growth analysis because the relative growth rate (RGR, mg g−1 d−1) is the product of the net assimilation rate (NAR, g m−2 leaf area d−1) and leaf area ratio (LAR, m2 leaf area kg−1 plant mass). NAR reflects the balance between photosynthetic carbon gain and respiratory carbon loss at a whole plant level. LAR is the product of specific leaf area (SLA, m2 leaf area kg−1 leaf mass) and leaf mass ratio (LMR, g leaf mass g−1 plant mass), enabling a quantitative means of integrating effects of variation in allocation and leaf area expansion on growth (Poorter and Remkes, 1990). Both NAR and LAR are important components of the growth responses of halophytes to salinity, but most studies have found NAR to be the more important factor for variation within species (Ball, 1996). However, none of these studies has, to our knowledge, explored the relative importance of LAR and NAR over a broad range of salinity from freshwater to seawater.

Many studies have emphasized effects of high salinity on water use. Mangroves typically have relatively low evaporation rates and high water-use efficiencies (Ball and Farquhar, 1984; Clough and Sim, 1989). These water-use characteristics become increasingly conservative with an increase in salinity and the salt tolerance of the species (Ball et al., 1988, 1997; Ball, 1988a) with far-reaching consequences for the structure and function of mangrove forests along salinity gradients (Ball, 1996). These studies invite the questions: what processes limit water use, and hence growth, in saline environments?

Hydraulic traits of woody plants are known to vary strongly with environmental conditions both across and within species (Tyree et al., 1998; Ewers et al., 2000; Cavender-Bares and Holbrook, 2001; Choat et al., 2007). In mangroves, hydraulic conductance of stems is typically lower in plants grown in higher than lower soil salinities (Sperry et al., 1988; Melcher et al., 2001; Ewers et al., 2004; Lopez-Portillo et al., 2005; Lovelock et al., 2006; Santini et al., 2012, 2013), but effects of salinity have not been systematically investigated except for Laguncularia racemosa (Sobrado, 2005, 2007). Lower stem hydraulic conductivity where salinities are high has been associated with structural changes in hydraulic anatomy that restrict rates of flow but also reduce vulnerability of xylem vessels to cavitation (Melcher et al., 2001; Sperry et al., 1988). Thus, the capacity of roots and stems to supply water to leaves can decline with increasing salinity, with consequent increase in limitations to carbon gain.

The present study focused on growth of the grey mangrove Avicennia marina in response to salinity ranging from freshwater to seawater. The grey mangrove is one of the most widespread species of mangroves with a latitudinal range from 25 °N in Japan to 38 °S in Australia (Tomlinson, 1986; Duke, 2006). In nature, A. marina dominates highly saline habitats with salinities up to 1·5 times (Martin et al., 2010) or twice that of seawater (Reef et al., 2012). It is also one of the most tolerant of mangroves to salinity, aridity, water temperature and frost frequency (Morrisey et al., 2010). According to many growth studies summarized in Table 1 the optimum salinity for growth of A. marina varies from 10 to 90 % seawater (salinity 35 p.p.t.) depending on the source population and growth conditions. However, poor growth was consistently found in freshwater for unknown reasons.

Table 1.

A summary of reported effects of salinity on growth of A. marina under various treatment conditions

| Material | Source | Salinity (% seawater) | Nutrient solution | Time (months) | Optimum salinity (% seawater) | Responses to salinity extremes | Measure of growth | Net biomass increase in freshwater | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seedlings | QLD, Australia | 0, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150 | Modified Hoagland’s | 2 | 60 | No mortality recorded. Growth was similar for 0 and 100 % seawater treatments and lower in 150 % seawater | Final biomass, plant height | Yes | Connor (1969) |

| Propagules | South Australia | 0, 10, 25, 50, 75, 100 | Hoagland’s | 11 | 10–50 | Early development in 0 % seawater was rapid. Necrotic lesions appeared on leaves several months after establishment. Growth in 100 % seawater was as poor as in 0 % seawater | Final biomass, plant height | Yes | Downton (1982) |

| Seedlings | QLD, Australia | 0, 25, 50, 75, 100 | Nutrient | 11 | 25 | Growth in freshwater was as poor as in 100 % seawater. Necrotic lesions appeared in shoots after grown in freshwater for 6 months | Final biomass | Not calculated | Clough (1984) |

| Seedlings | NSW, Australia | 0, 25, 50, 100 | Nutrient (Helyar – 1980) | 1·5 | 25 | Final biomass | Not calculated | Burchett et al. (1984) | |

| Seedlings | Durban, South Africa | 20, 60, 100 | Nutrient | 3 | 20 | Growth decreased with increase in salinity | Net biomass | NA | Naidoo (1987) |

| Seedlings | NSW, Australia | 10, 50, 100 | Johnson’s | 4 | 10–50 | Growth was lowest in 100 % seawater, but responses depended on humidity | Net biomass | NA | Ball (1988b) |

| Seedlings | NSW, Australia | 0, 25, 100 | Aquasol | 11 | 25 | Growths in freshwater and seawater were similar | Final biomass | Not calculated | Burchett et al. (1989) |

| Propagules | Indus delta, Pakistan | 0, 25, 50, 75, 100 | Nitrogen | 6 | 50 | No significant difference was found for growth in seawater and freshwater | Final biomass | Not calculated | Khan and Aziz (2001) |

| Propagules | Hong Kong | 0, 15, 45, 75, 100 | None | 3 | 0 | Growth decreased with increase salinity | Net biomass | Yes | Ye et al. (2005) |

| Propagules | Fujian, China | 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 150 | None | 3 | 15–90 | Growth was poor in extreme conditions (0, 110, 135 % seawater) | Final biomass | Not calculated | Yan et al. (2007) |

| Propagules | Gujjarat, India | 0, 10, 15, 25, 30, 40, 50, 55, 60, 70 | Soil used for growth contained N, P, K, Ca | 6 | 50 | Plant biomass increased with increase in salinity from 0 to 50 % seawater and declined at higher salinities | Final biomass | Not calculated | Patel et al. (2010) |

In the present study, three approaches were combined to gain an understanding of factors limiting growth of A. marina along a salinity gradient. Growth analysis was used to determine the relative importance of LAR and NAR to variation in growth over the salinity gradient. Gas exchange characteristics were measured to determine patterns in carbon gain relative to water use, and hydraulic anatomy was assessed to explore possible structural limitations to water transport and hence also leaf water use.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material and experimental design

Seawater (salinity = 35 p.p.t.) was collected near Batemans Bay, New South Wales, for use in mangrove cultivation. Propagules of Avicennia marina (Forssk.) Vierh. collected in Brisbane, Queensland, were grown on a sand bed irrigated with 50 % seawater under glasshouse conditions at the Australian National University (Canberra, Australia). After 4 months, when cotyledons had senesced and seedlings had grown two leaf pairs, 35 similar-sized plants were chosen for the experiment.

At the start of the experiment, plant height, plant fresh mass, and the length and width of each leaf were measured non-destructively on all 35 seedlings. One group of five seedlings was harvested for measurement of initial leaf area and biomass characteristics. These plants were separated into roots, stems and leaves. Leaf area was measured with a LI 3100 area meter (LI-COR Inc., Lincoln, NB, USA). All plant parts were then dried at 60 °C for 72 h before measuring dry mass with a Mettler – Toledo XP205 balance (Mettler – Toledo Ltd, Greifensee, Switzerland). Data from the harvested seedlings were used to determine the relationship between leaf area and the area estimated by multiplying leaf length by leaf width. This relationship [leaf area = 0·702(leaf length × leaf width) – 0·185, r2 = 0·98] was then used to estimate the initial leaf area of each seedling allocated to the growth experiment. The initial dry mass of each seedling (W1) was then estimated from its leaf area with the assumption that the average ratio of leaf area per plant dry mass determined for harvested seedlings was the same for all seedlings.

The 30 seedlings allocated to the growth experiment were transferred from the sand beds to an aerated hydroponic cultivation system where they were grown for 22 weeks in a fully randomized design with five blocks and six salinity treatments (0, 5, 25, 50, 75 and 100 % seawater). The salinity of all hydroponic solutions was initially 50 % seawater to match the salinity in which the seedlings had been grown. To avoid a sudden change in water potential, the salinity of the hydroponic solutions was changed at a rate of 5–10 % seawater every 2 d until the required treatment salinities were reached. The dilutions of seawater were amended with half-strength nutrient solution (Supplementary Data Table S1; Johnson et al., 1957) for the first 10 weeks and full-strength solution the following 12 weeks. Hydroponic solutions were changed every 2 weeks. Temperature inside the glasshouse fluctuated diurnally with maximum and minimum temperatures of 30 and 15 °C, respectively.

At harvest, plants were separated into roots, stems and leaves; leaf areas were measured and then all plant parts were dried at 60 °C for 72 h before measuring dry mass as described above.

RGRs and other components were calculated for each plant using standard equations presented by Kriedemann et al. (2014) as follows:

in which W2 was the dry mass measured at the time of harvest (t2), and W1 was dry mass at the start (t1), estimated from the allometric relationship between leaf area and plant mass measured at the start of the experiment.

LAR (m2 kg−1) was calculated as the ratio of leaf area to total plant mass. The average LAR during the growth period was calculated for each plant as the mean of the value estimated at the start and that measured at the conclusion of the experiment. The average NAR (g m−2 d−1) during the growth period was calculated for each plant assuming that RGR = NAR × LAR.

Gas exchange measurements

Photosynthetic gas exchange characteristics were measured on the youngest fully expanded leaf of each plant with a Li-Cor 6400XT Portable Photosynthesis System (LI-COR Inc.) in the 17th week (29 March), 4 weeks before harvest. Leaf pairs (consisting of the leaf used for gas exchange measurement and its opposite leaf) were then separated from the plants for fresh weight, and leaf area measurement. One of the two leaves was dried along with other parts of the plant; the other leaf and one stem segment were preserved in formalin–acetic acid–alcohol (FAA) (Berlyn et al., 1976). As the ratio between fresh and dry weight was almost constant within a leaf pair, dry weight of the preserved leaves was estimated from that of the dried leaf and added to total leaf and plant dry weight.

Carbon isotope analysis

The dried leaf samples were ground using a ball mill, homogenized and a subsample (approx. 4 mg) was analysed for carbon isotope ratio, δ13C, using a coupled EA-MS system (EA 1110 Carlo Erba, Milan, Italy; Micromass Isochrom, Middlewich, UK).

Leaf and stem anatomy

After harvest, stems and leaves were fixed in FAA for 1 week and then preserved in 70 % (v/v) ethanol with a few added drops of glycerol. Samples were washed with water before cutting into 20- to 30-µm-thick sections with a sledge microtome (GSL 1, S. Lucchinetti, Schenkung Dapples, Zürich, Switzerland). Those sections were stained with either Toluidine Blue [0·05 % (w/v) in water) or a 50:50 mixture of Alcian Blue [1 % (w/v) in 50 % (v/v) alcohol] and Safranin O [1 % (w/v) in water]. Micrographs of stem were taken at 25× for stem and sapwood area measurements. Counts were made of all vessels in one-quarter of each stem transverse section or in the entire mid-vein vascular bundle of each leaf section at 100×. Vessel areas were measured and diameters were calculated from the area assuming a circular shape (Mapfumo, 1994).

Vein density was determined according to Scoffoni et al. (2013). Leaf areas were measured and leaves were then scanned with a CanoScan LiDe 110 (Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Major vein (primary and secondary vein orders) lengths were measured from images of the whole leaf and minor vein (third vein order onward) lengths were measured in leaf pieces (1 cm2) cut from the centre of the leaf lamina on one side of the midvein. Leaf pieces were incubated in maceration solution [five parts 30 % (v/v) hydrogen peroxide to one part glacial acetic acid] at 70 °C for 30 min or until the epidermal layers separated from the mesophyll. The epidermal peels were saved for measurements of salt gland and stomatal density as described below. The portion containing veins was then transferred to lactic acid (80 %, w/w) and incubated for 1 week to remove mesophyll cells before washing with water and then staining with Safranin O [0·01 % (w/v) in water]. Images were collected at 50×.

Salt glands were counted in three fields of view of the upper epidermal peel (25×). Stomata are obscured by a dense layer of trichomes, and hence cannot be observed directly. For this reason, the lower epidermal peel was stained with a 50:50 mixture of Alcian Blue [1 % (w/v) in 50 % (v/v) alcohol] and Safranin O [1 % (w/v) in water], and then inverted to view stomata from the interior surface of the epidermis (i.e. inside out). Stomata were counted in three fields of view (200×).

Micrographs were taken with digital cameras (SPOT Flex 64MP Color FireWire 15.2, Diagnostic Instruments, Stirling Heights, MI, USA) coupled with light or upright microscopes (Axioskop, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany and DM 6000, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and analysed using ImageJ (Rasband, 1997–2014).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted with Genstat version 16 (Payne et al., 2014). The data were amenable to analysis by one-way ANOVA and linear regressions without prior transformation. Where significant relationships were found, the Fisher’s Least Significant Difference test was applied post hoc to determine significant differences between treatment means.

RESULTS

The average leaf area and biomass characteristics of five seedlings harvested at the start of the experiment are given in Table 2. The average LAR of these seedlings (1·63 ± 0·16 m2 leaf area kg−1 plant dry mass) was used to estimate the initial dry mass of seedlings in the growth experiment, as described in the Methods. With one exception, the average estimated initial dry masses of seedlings (Fig. 1A) were similar to the average measured dry mass (1·90 ± 0·25 g) of the seedlings harvested at the start of the experiment (Table 2). Although seedlings were randomly assigned to each treatment, the estimated initial biomass of seedlings in the 0 % seawater treatment was greater (P = 0·022) than those in the other treatments (Fig. 1A).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the five Avicennia marina seedlings harvested at the beginning of the experiment; all weights are of dried material, mean ± s.e., n = 5

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Total dry mass (g) | 1·90 ± 0·25 |

| Roots (g) | 0·70 ± 0·15 |

| Stems (g) | 0·70 ± 0·15 |

| Leaves (g) | 0·60 ± 0·06 |

| Root/shoot (g g−1) | 0·56 ± 0·09 |

| Root/leaf (g g−1) | 1·12 ± 0·17 |

| Root/leaf area (g m−2) | 22·85 ± 3·85 |

| Total leaf area (cm2) | 29·78 ± 2·34 |

| Leaf area/plant mass (m2 kg−1) | 1·63 ± 0·16 |

| Leaf mass/plant mass (g g−1) | 0·32 ± 0·02 |

| Leaf area/leaf mass (m2 kg−1) | 5·01 ± 0·20 |

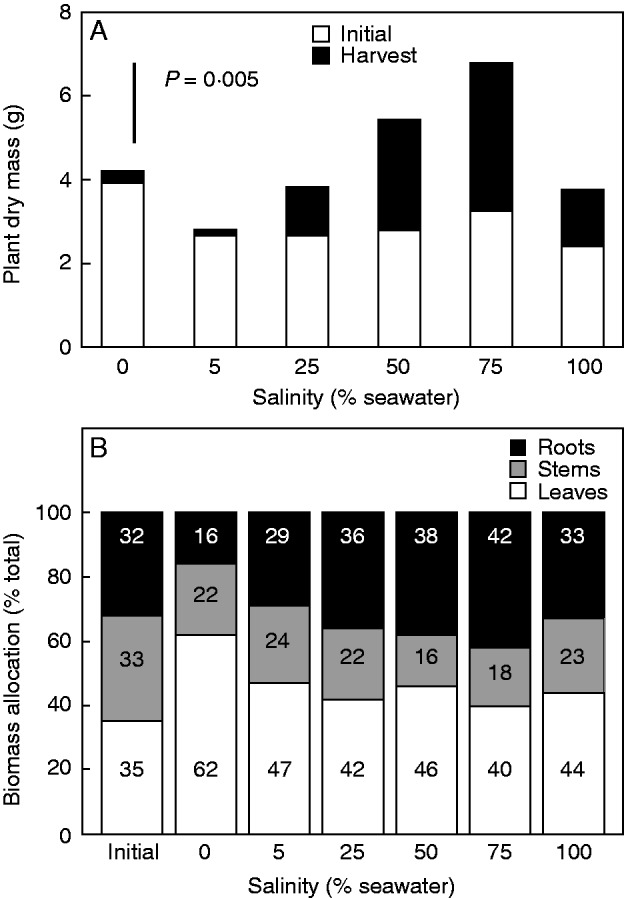

Fig. 1.

Variation along a salinity gradient in (A) total dry mass of A. marina seedlings at the beginning of the experiment and at harvest, and (B) biomass allocation to roots, stems and leaves (see key). Values are means, n = 5; the bar in (A) shows the least significant difference between means at the 5 % level (LSD). P value indicates the overall effect of salinity.

Final biomass increased with increasing salinity to a maximum in 75 % seawater (Fig. 1A). Growth in 0 and 5 % seawater was poor. These seedlings lost at least one leaf or the first leaf pair during the first month after transfer to treatment conditions. Some seedlings initiated new shoot growth but failed to develop new leaves.

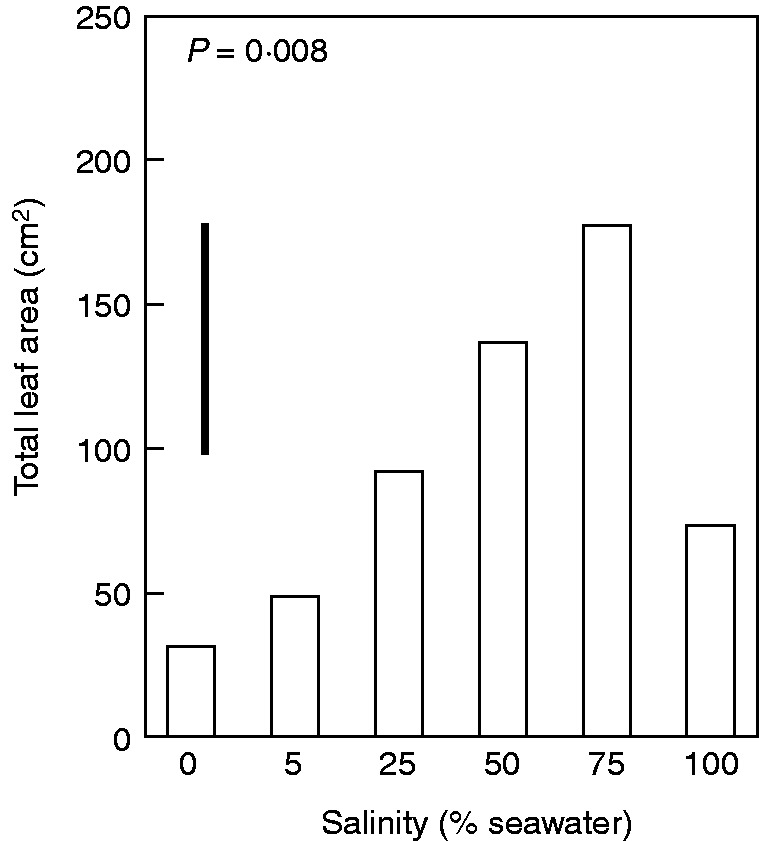

Salinity significantly affected biomass allocation to roots (P = 0·001), stems (P = 0·002) and leaves (P = 0·001) (Fig. 1B). Allocation of plant mass to roots in seedlings was significantly (P = 0·001) greater when grown in freshwater than in dilutions of seawater. Interestingly, seedlings of 50 and 75 % seawater invested significantly (P = 0·002) less in stems than did seedlings in other treatments. In contrast, allocation to leaves was significantly lower (P = 0·001) in seedlings grown in 0 % seawater than in those in other salinities. Biomass allocation to leaves (Fig. 1B) and total leaf area (Fig. 2) increased with increasing salinity with maximal leaf area occurring in 75 % seawater. The values for seedlings grown in 0 and 5 % seawater reflected only the contribution of leaves grown before imposition of treatments as no new leaf growth occurred in these seedlings. Consequently, root/shoot ratio was significantly higher (P = 0·001) in seedlings grown in freshwater than in those grown with salt. LAR is central to understanding effects of allocation patterns on plant growth rates. The LAR measured at harvest varied significantly with salinity (Table 3), although most of the effect was driven by the very low values in plants grown in 0 % seawater. Among the two components that make up LAR, SLA was insensitive to salinity (P = 0·751, Table 3) while LMR significantly (P < 0·001) increased with increasing salinity to a maximum in 75 % seawater (Table 3). Thus, variation in LAR at harvest corresponded with variation in LMR.

Fig. 2.

Total leaf area in A. marina seedlings grown along a salinity gradient. Values are means, n = 5; the bar shows the least significant difference between means at the 5 % level (LSD). P value indicates the overall effect of salinity.

Table 3.

Variation in the leaf area ratio (LAR) and its components at the time of harvest; values are means ± s.e., n = 5

| Treatment (% seawater) | LAR (m2 kg−1) | LMR (g g−1) | SLA (m2 kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0·75 ± 0·3 | 0·16 ± 0·02 | 5·13 ± 1·0 |

| 5 | 1·65 ± 0·3 | 0·29 ± 0·02 | 5·74 ± 1·0 |

| 25 | 2·35 ± 0·4 | 0·36 ± 0·03 | 6·83 ± 1·1 |

| 50 | 2·58 ± 0·3 | 0·38 ± 0·02 | 6·97 ± 0·9 |

| 75 | 2·69 ± 0·3 | 0·42 ± 0·02 | 6·58 ± 0·9 |

| 100 | 2·04 ± 0·3 | 0·33 ± 0·02 | 6·20 ± 0·9 |

| LSD | 1·01 | 0·07 | |

| P value | 0·01 | <0·001 | 0·751 |

LSD is the least significant difference between means at the 5 % level. P value indicates the overall effect of salinity.

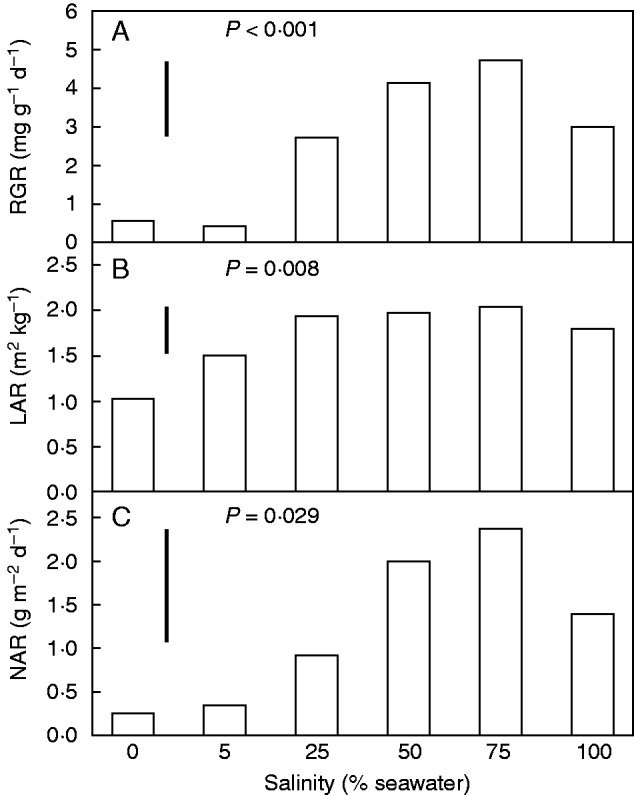

RGR and its components, LAR and NAR, varied with salinity (Fig. 3). Average RGRs were maximal in seedlings grown in 50–75 % seawater (Fig. 3A). At the start of the experiment, seedlings had an average (±s.e.) LAR of 1·63 ± 0·16 m2 kg−1 (Table 2) which changed during growth to the range of values (0·75–2·7 m2 kg−1) shown in Table 3. For the purpose of comparison with RGR, the average LAR during growth was estimated as the mean of values at the start and end of the experiment for each plant. This average LAR during growth was minimal in plants grown in freshwater and showed less variation with salinity from 5 to 100 % seawater than did RGR (Fig. 3B). NAR was calculated as the value that would be required to account for RGR given the average LAR during growth. While both average LAR and NAR varied significantly with salinity in a pattern similar to that of RGR, NAR was a better predictor of RGR (r2 = 0·92, P < 0·001) than LAR (r2 = 0·30, P = 0·002).

Fig. 3.

RGR (A), average LAR during growth (B) and NAR (C) of A. marina seedlings grown along a salinity gradient. Values are means, n = 5; the bar shows the least significant difference between means at the 5 % level (LSD). P value in each panel indicates the overall effect of salinity.

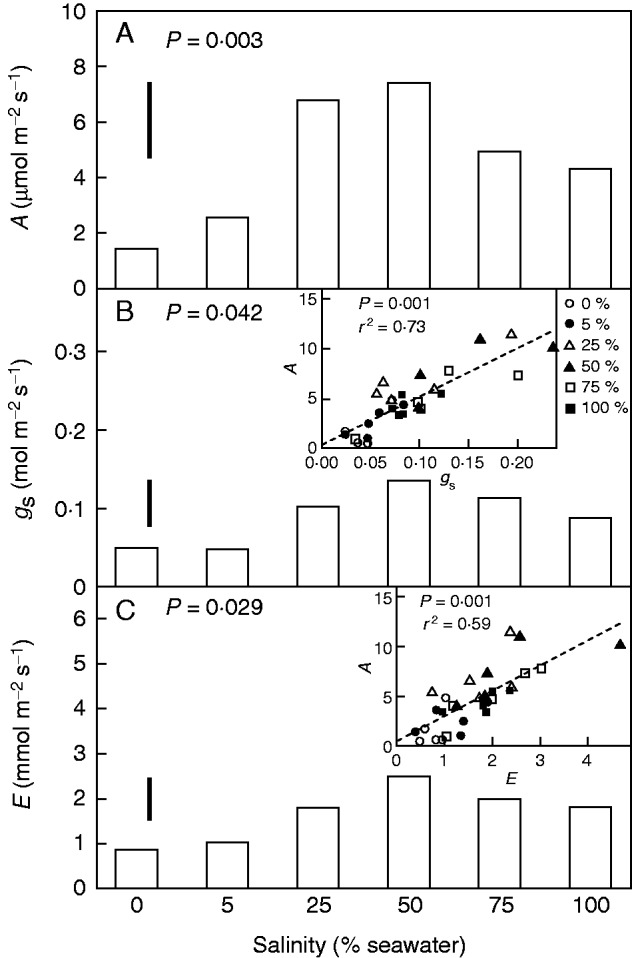

CO2 assimilation rate, stomatal conductance and evaporation rate were all significantly (P = 0·003, 0·042 and 0·029, respectively) affected by salinity (Fig. 4). These gas exchange parameters were all very low in plants grown in 0–5 % seawater and markedly higher in plants grown in higher salinities. Variation in the CO2 assimilation rate was proportional to that in stomatal conductance (Fig. 4B) such that the intercellular CO2 concentration was insensitive to salinity, and averaged 298 ± 3 µmol mol−1 when measurements were made under an ambient CO2 concentration of 400 µmol mol−1. Consequently, the instantaneous water use efficiency (WUE) was approximately constant regardless of whether measured as the ratio of assimilation rate A to stomatal conductance gs (A/gs =52·03 ± 9·4 µmol mol−1) or to evaporation rate (A/E = 2·88 ±0·6 mmol mol−1). As no new leaves formed in plants growing in 0 and 5 % seawater, carbon isotopic composition was analysed only in leaves grown in the four higher salinities. Data revealed no significant effects of salinity on leaf δ13C, which averaged −25·8 ± 0·2‰, the lack of variation being consistent with the gas exchange characteristics. Hydraulic anatomy was then investigated in stems and leaves because the above data showed a correspondence between water use and growth.

Fig. 4.

Gas exchange characteristics of leaves of A. marina grown along a salinity gradient. (A) CO2 assimilation rate. (B) Stomatal conductance – gs. Inset shows CO2 assimilation rate as a function of stomatal conductance. Line drawn by linear regression. (C) Evaporation rate, E. Inset shows CO2 assimilation rate as a function of evaporation rate. Line drawn by linear regression. Values are means, n = 5; bars show least significant differences between means at the 5 % level (LSD). P value in each panel indicates the overall effect of salinity. Each point in an inset is from an individual plant. Symbols indicate salinities (per cent seawater) in which the plants were grown, as indicated in the key in (B).

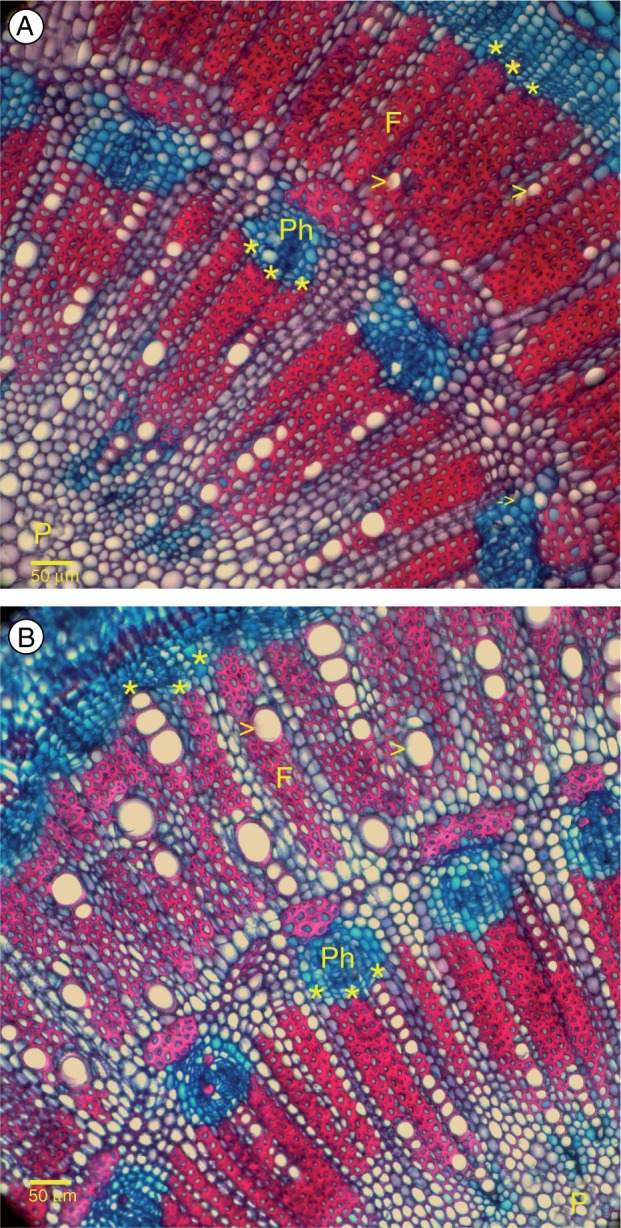

Instead of one vascular cambium, stems of A. marina have successive cambia (Schmitz et al., 2008) that develop and form successive, alternating rings of secondary xylem and phloem (Fig. 5). In the present study, the first vascular rings were formed prior to the start of the experiment when all seedlings were pre-grown in 50 % seawater. There were no significant differences between seedlings in the structure of the first vascular ring. However, salinity affected both growth and composition of the second ring.

Fig. 5.

Transverse sections of stems of A. marina grown in (A) 0 % and (B) 75 % seawater. Sections were stained with Alcian blue and Safranin O. Each panel shows a sector of the stem from the pith through the first two vascular rings, each containing both xylem and phloem. The first or inner-most ring was grown prior to the experiment when seedlings were in 50 % seawater. The second or outer-most ring formed while seedlings grew in the experimental treatments. Abbreviations: arrow, xylem vessel; Ph, phloem; asterisks (***), successive cambia; F, fibres; P, pith. Scale bar = 50 µm.

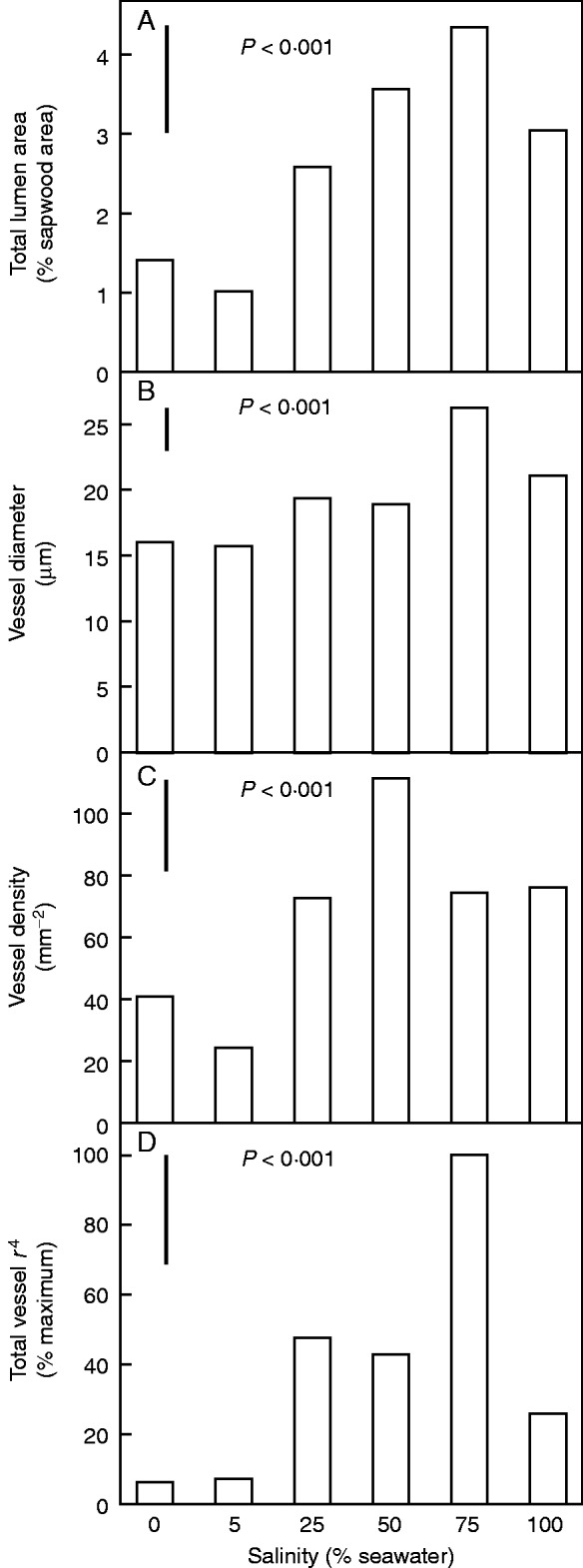

In 0 and 5 % seawater, seedlings formed few vessels despite all other aspects of the newly formed vascular ring appearing normal (Fig. 5A), as shown by comparison with the equivalent second ring in a seedling grown in 50 % seawater (Fig. 5B). In the second rings, total lumen area (Fig. 6A) was smallest in seedlings grown in 0 and 5 % seawater due to combined effects of lower vessel density (Fig. 6B) and smaller average vessel diameter (Fig. 6C) than in the sapwood of seedlings grown in higher salinities. These anatomical differences would severely constrain stem water transport in seedlings grown in the low salinities. This was shown by using the anatomical data to estimate potential stem hydraulic conductance according to the Hagen–Poiseuille law. If vessel lengths are assumed to be the same in all treatments, then a potential hydraulic conductance can be estimated by summing the values of vessel radii, each raised to the 4th power, for stems of each plant in each treatment. As shown in Fig. 6D, the average potential hydraulic conductance was maximal in seedlings grown in 75 % seawater and minimal in seedlings grown in 0 and 5 % seawater, consistent with differences in the numbers and size distributions of vessels in the sapwood of seedlings grown under different salinities.

Fig. 6.

Xylem vessel characteristics in the second vascular ring of stems of A. marina seedlings grown along a salinity gradient. (A) Total lumen area, (B) vessel density, (C) vessel diameter, and (D) sum of the 4th power of vessel radii presented in per cent of the maximum value. Values are means, n = 5; bars show least significant differences between means at the 5 % level (LSD). P value in each panel indicates the overall effect of salinity.

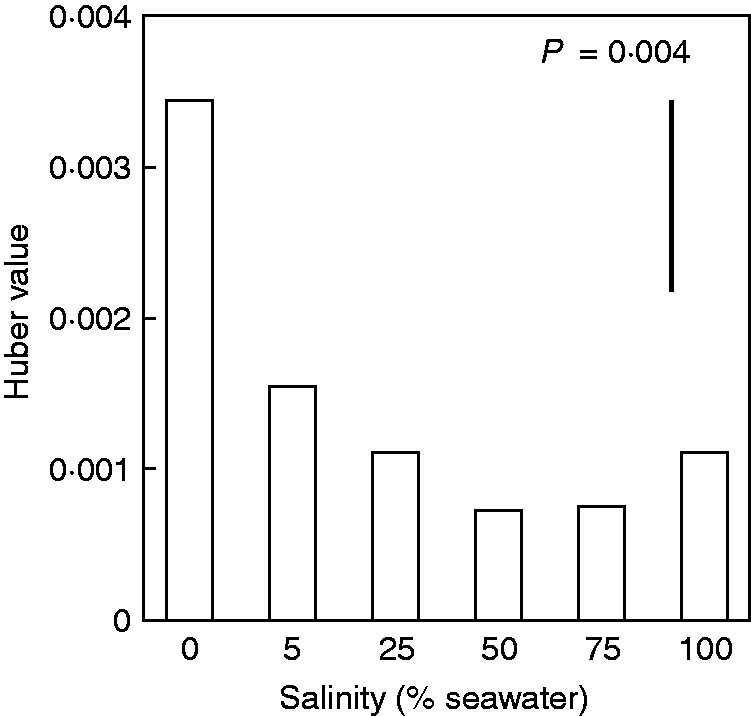

At harvest, stem and sapwood area showed no significant differences among treatments (P = 0·094 and 0·059, respectively). In contrast, total leaf area varied significantly with salinity (P = 0·008) with maximum leaf area occurring in plants grown in 75 % seawater. Consequently, Huber values (i.e. the sapwood area per total downstream leaf area supported by the stem) were also significantly affected by salinity (P = 0·003). Huber values were greater in plants grown in 0 % seawater than in those grown in dilutions of seawater (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Huber value of A. marina seedlings grown along a salinity gradient. Values are means, n = 5; bar shows least significant difference between means at the 5 % level (LSD). P value indicates the overall effect of salinity.

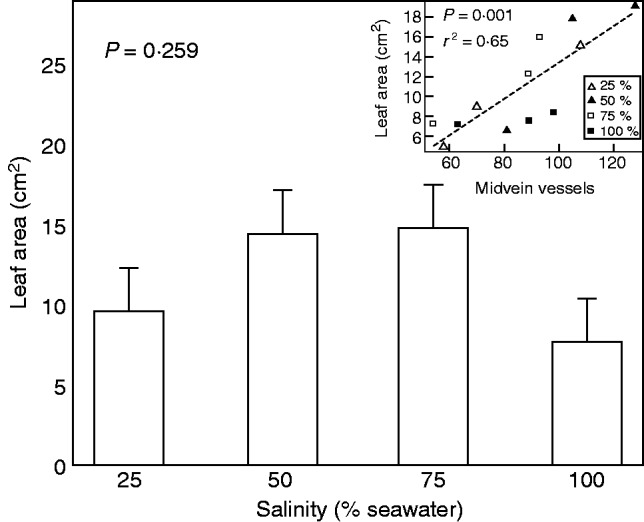

Leaf structures were less sensitive to salinity than those in the stems. However, as plants from 0 and 5 % seawater treatments failed to produce new leaves, anatomical analyses focused only on plants grown in the four higher salinity treatments. There were no significant differences in leaf thickness, nor in the proportions of hypodermis, palisade mesophyll, spongy mesophyll and trichome layers relative to total leaf thickness (Table 4). Salinity also had no significant effects on densities of veins, salt secretion glands or stomata. So unless stomatal pore depths were affected by salinity, the differences in stomatal conductance (Fig. 4B) must have been associated with differences in aperture. In general, differences in the area of individual leaves, although reflecting similar trends to total leaf area, were not statistically significant. However, individual leaf area was proportional to the total number of vessels in the midvein (r2 = 0·65, P = 0·001) (Fig. 8). It is likely that, except for the hydraulic composition of midveins, there were no structural differences in leaves that could account for the differences in water use between seedlings grown in different salinities (Fig. 4C).

Table 4.

Average characteristics of leaves of A. marina developed during plant growth in salinities ranging from 25 to 100 % seawater; there were no significant effects of salinity on any of the characteristics listed; n = 12, three replicates per treatment

| Leaf feature | Units | Mean value | s.e. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf thickness | µm | 675 | 15 |

| Hypodermal thickness | µm | 273 | 6 |

| Palisade mesophyll thickness | µm | 206 | 8 |

| Spongy mesophyll thickness | µm | 101 | 4 |

| Trichome thickness | µm | 96 | 3 |

| Leaf area | cm2 | 11·7 | 1·4 |

| Major vein density | mm mm−2 | 0·16 | 0·01 |

| Minor vein density | mm mm−2 | 11·8 | 0·5 |

| Stomatal density | mm−2 | 174 | 24 |

| Adaxial salt secretion gland density | mm−2 | 4 | 1 |

| δ13C | ‰ | −25·8 | 0·2 |

Fig. 8.

Area of individual leaves in A. marina seedlings grown along a salinity gradient ranging from 25 to 100 % seawater. Values are means ± s.e., n = 5. Inset shows leaf area as a function of total number of midvein vessels. Each point is from an individual plant. Line drawn by linear regression. Symbols indicate salinity (per cent seawater) in which the plants were grown, as indicated in the key.

DISCUSSION

Variation in the growth of A. marina along a salinity gradient is the product of complex adjustments in morphology and function that contribute to carbon, water and nutrient balances at the whole plant level. The results of the present study show that multiple factors can co-limit growth, and that the relative importance of different factors varies along a salinity gradient. In the following discussion, growth will be evaluated from three perspectives: carbon gain, water use and apparent salt requirements for water transport.

Growth in relation to carbon gain

Many factors affect growth but growth analysis provides insight into the nature of carbon balances under saline conditions. In the present study, A. marina seedlings failed to grow in 0–5 % seawater, whereas biomass accumulation was maximal in 50–75 % seawater (Fig. 1A). Biomass accumulation was greatest where biomass allocation was maximal to leaves and minimal to roots (Fig. 1B). Maximal allocation to leaves coincided with the greatest leaf area without significant variation in SLA (P = 0·751). This view suggests that the variation in growth was driven by effects of salinity on leaf area. This is best evaluated by examining effects of the average LAR during growth on relative growth rate (Fig. 3).

In the present study, the average LAR during growth (Fig. 3B) varied significantly with salinity, with responses being most pronounced at salinity extremes. Low LAR in 0 % seawater reflected the failure to form new leaves combined with greater biomass allocation to roots. As salinity increased from 5 to 100 % seawater, the pattern of change in LAR was similar to that of RGR (Fig. 3). However, NAR must have been more responsive than LAR to account for the variation in RGR with salinity. Indeed, the time-averaged estimates of NAR (Fig. 3C) were well correlated (P < 0·001, r2 = 0·60) with the independent, instantaneous measurements of leaf CO2 assimilation rates in response to growth salinity (Fig. 4), emphasizing the strong contribution of photosynthetic rates to variation in RGR. Similarly, research on growth of Avicennia germinans (Suarez and Medina, 2005) emphasized a strong correlation between RGR and NAR. These studies in mangroves are consistent with more general patterns found in a meta-analysis (Shipley, 2006) that NAR is a better predictor than LAR for variation in growth within species. In contrast, LAR is the more important predictor of differences in RGR between species (Lambers et al., 1998; Antunez et al., 2001; Osone et al., 2008; Poorter and Remkes, 1990).

Growth in relation to water use

The above analysis emphasizes NAR as a driver of the variation in growth along a salinity gradient. However, carbon cannot be gained without the expenditure of water. In this sense, growth can be considered as the product of water use and WUE. Measurements of leaf gas exchange characteristics and isotopic compositions independently showed that WUE was constant during instantaneous measurements of leaf function or when integrated over the time required for leaf growth. A highly conservative WUE is consistent with previous studies of A. marina over a smaller salinity range (Ball and Farquhar, 1984; Ball, 1988a) and of crop plants subjected to variation in nitrogen nutrition, water supply and irradiance (Wong et al., 1979). Consequently, growth varied with water use. Plants that used more water had higher stomatal conductance and proportionally higher assimilation rates. The implication might be that the supply of water to leaves limited their capacity to gain carbon.

The present study showed that salinity affected the capacity for water transport through stems. In low salinity, seedlings lost at least one leaf or the first pair of leaves during the first month after transfer to treatment. Some seedlings in low-salinity treatments seemed to produce new shoots but none developed into new leaves. Moreover, although the cambium was still functioning in the stems, very few new vessels formed (Fig. 5A). Therefore, water transport relied mostly on the primary vessels that had developed before the experiment. Both vessel density and diameter were affected by salinity (Fig. 6) but the trends were not as clear as in previous studies that emphasized only the high salinity range. Santini et al. (2012) found that variation in total vessel lumen area in A. marina was driven by variation in vessel diameter. However, vessel density increased while vessel diameter decreased with increase in salinity from 75 % to approx. 1·5 times seawater in Rhizophora mucronata (Schmitz et al., 2006), from 1 to approx. 2 times seawater in A. marina (Robert et al., 2009), and from 0 to 100 % seawater in Laguncularia racemosa (Sobrado, 2007). Huber values were maximal at 0 % seawater in A. marina due to leaf loss and unchanged sapwood area (Fig. 6). However, as the composition of sapwood area (i.e. vessel size and density) changed, the hydraulic conductance would change accordingly. For this reason, the high Huber values in seedlings grown in freshwater were not associated with a greater supply of water to leaves. In another case, Huber values were maximal in L. racemosa grown in 0 % seawater but these maximum values were due to a decrease in xylem area with an increase in salinity and were proportional to hydraulic conductance (Sobrado, 2007). Despite the variation in results between different studies conducted in different species, all studies show change in stem hydraulic anatomy, and hence also in capacity to supply water to leaves, with increasing salinity.

As leaf functions were affected by salinity, leaf structure was also expected to change with salinity. However, anatomical analyses of the four high-salinity treatments showed no significant variation in leaf thickness (P = 0·089) or in the proportions of hypodermal (P = 0·611), palisade mesophyll (P = 0·342), spongy mesophyll (P = 0·203) and trichome layers (P = 0·475) relative to total thickness. There was also no significant difference in major (P = 0·597 and 0·255 for primary and secondary vein densities, respectively), minor (P = 0·276) and total leaf vein density (P = 0·576), stomata (P = 0·825) and salt secretion gland (P = 0·496) densities in A. marina (Table 4), even though the CO2 assimilation rates varied among salinity treatments (Fig. 4). However, we found that leaf size and the total number of vessels in midveins changed proportionally (r2 = 0·65, P = 0·001) (Fig. 8) whereas the number of secondary veins was constant. Variation in the composition of vascular bundles might influence leaf size through effects on hydraulic conductance even as the ratio of vein length per leaf area, the vein density, remained constant. In other words, leaf expansion may partly depend on the capacity of the hydraulic system.

Is A. marina an obligate halophyte?

Three lines of evidence indicated severe loss of function under freshwater conditions. First, when healthy seedlings were transferred gradually from 50 to 0 % seawater, shoot growth continued, but necrotic lesions developed in the newly growing leaves and shoot apices. Similar observations were reported by Downton (1982). Second, all seedlings survived, but anatomical studies of the stems revealed variation in both the rates of development and composition of hydraulic tissues that were consistent with salinity-dependent patterns in water use and growth. Specifically, seedlings grown in freshwater were slow to form the second vascular ring and it contained very few xylem vessels compared with those grown with salt (Fig. 5). Third, impaired differentiation of xylem vessels under freshwater conditions had far-reaching consequences for water transport between roots and leaves, restricting the availability of water to sustain carbon gain and shoot growth under freshwater conditions. Nevertheless, adverse effects of salinity-deficient conditions are unlikely to be limited to effects on xylem development; other factors such as metabolic or hormonal processes might also be impaired under extreme low salinity. Further study is needed to clarify the ontogeny of A. marina under hyposaline conditions.

An apparent limitation in the supply of water available to plants grown in freshwater or low salinity was unexpected given the presumed ease with which water could be accessed at high water potentials. When grown in freshwater, the water potential of A. marina leaves was −1·8 MPa, with an osmotic potential of −2 MPa associated with accumulation of a relatively high concentration of K+ (300 mm) and other organic solutes (Downton, 1982). This would generate a sufficient gradient for uptake of water unless some other factors were adversely affected by either the lack of NaCl or the unusually high concentration of K+. Under saline conditions, leaves accumulate high concentrations of Na+ and Cl−, apparently for osmotic adjustment of the vacuole, and the concentration of K+ declines to approximately 100 mm (Downton, 1982). Flowers and Colmer (2008) speculated that without a normal Na+ and Cl− supply, futile cycling of K+ resulting from a poor capacity to retain K+ in vacuoles might exacerbate energetic demands of ion compartmentation while the high K+ concentration could also have toxic effects on the cytoplasm processes. The mechanism remains elusive.

To date, there is no evidence for the existence of an obligate halophyte among angiosperms given the requirement for sodium chloride to survive (Krauss and Ball, 2013). The latter authors considered the species inhabiting mangrove forests to be either moderately salt-tolerant glycophytes or facultative halophytes, all capable of growth in freshwater with facultative halophytes distinguished by the enhancement of growth under saline conditions. Here we argue that there may be a third category that, while not requiring salt for survival, may require saline conditions to reach reproductive maturity. We refer to saline conditions because seawater contains high concentrations of MgSO4 in addition to Na and Cl. Consequently, our use of dilutions of seawater precludes determination of plant responses to a deficiency in any single constituent. Nevertheless, growth of A. marina in 0 and 5 % seawater was so poor that the plants were unlikely to reach reproductive maturity. In this functional sense, we consider this species to be an obligate halophyte. Other species may also be functionally obligate halophytes based on extreme inhibition of their growth in freshwater. These species include Ceriops tagal (Smith, 1988), Bruguiera parviflora, Ceriops australis, C. decandra (Ball, 2002), Rhizophora mangle (Werner and Stelzer, 1990) and Sonneratia alba (Ball and Pidsley, 1995). Thus, mangrove species are arrayed along a continuum of salt tolerance. Moderately salt-tolerant glycophytes and facultative halophytes would dominate areas subject to prolonged exposure to freshwater or water of extremely low salinity. In contrast, facultative and obligate halophytes could dominate persistently highly saline areas.

CONCLUSIONS

Results of the present study revealed complex variation in the structure and function of A. marina seedlings grown in a range of salinities from 0 to 100 % seawater. This gradient produced two fundamentally different conditions such that salinities from 0 to 5 % seawater were deficient for growth while those from 25 to 100 % seawater were sufficient for growth. Under salinity-sufficient conditions, growth was correlated with all measures related to carbon gain. However, growth was also correlated with the capacity to supply water to leaves. Thus, the variation in growth was co-limited by water and carbon, and this co-limitation was reflected in the maintenance of a constant WUE under all growth conditions.

The variation in growth of A. marina along a salinity gradient from 0 to 100 % seawater reflected parallel trends in biomass allocation, canopy area expansion, gas exchange characteristics and hydraulic anatomy, particularly the size and density of stem xylem vessels. These salinity-dependent effects on differentiation of xylem vessels affected water transport over the whole salinity gradient, including imposition of water limitations to growth under conditions of salt deficiency. These results identified A. marina as a functional obligate halophyte, requiring a minimum salinity for development of the transport systems needed to sustain water use and carbon gain. Thus, while carbon gain and water use co-limited growth, stem hydraulic systems are central to understanding integrated growth responses of halophytes to salinity, and may have played an important role in the evolution of salt tolerance in halophytes.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org and consist of Table S1: Johnson’s nutrient solution.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

H.T.N. was supported by an Australian Awards Scholarship, and the research was supported by Australian Research Council Discovery Project Grant DP1096749. We thank Jack Egerton for expert technical assistance, Dr Ruth Reef (UQ) for providing seedlings of Avicennia marina and Dr Jeff Wood (ANU Statistical Consulting Unit) for advice.

LITERATURE CITED

- Antunez I, Retamosa EC, Villar R. 2001. Relative growth rate in phylogenetically related deciduous and evergreen woody species. Oecologia 128: 172–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball M. 1988a. Ecophysiology of mangroves. Trees 2: 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ball M. 1988b. Salinity tolerance in the mangroves Aegiceras corniculatum and Avicennia marina I. Water use in relation to growth, carbon partitioning, and salt balance. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 15: 447–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ball M. 1996. Comparative ecophysiology of mangrove forest and tropical lowland moist rainforest. In: Mulkey S, Chazdon R, Smith A, eds. Tropical forest plant ecophysiology. New York: Springer, 461–496. [Google Scholar]

- Ball M. 2002. Interactive effects of salinity and irradiance on growth: implications for mangrove forest structure along salinity gradients. Trees 16: 126–139. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MC, Farquhar GD. 1984. Photosynthetic and stomatal responses of two mangrove species, Aegiceras corniculatum and Avicennia marina, to long term salinity and humidity conditions. Plant Physiology 74: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball MC, Pidsley SM. 1995. Growth responses to salinity in relation to distribution of two mangrove species, Sonneratia alba and S. lanceolata, in Northern Australia. Functional Ecology 9: 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MC, Cowan IR, Farquhar GD. 1988. Maintenance of leaf temperature and the optimization of carbon gain in relation to water loss in a tropical mangrove forest. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 15: 263–276. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MC, Cochrane MJ, Rawson HM. 1997. Growth and water use of the mangroves Rhizophora apiculata and R. stylosa in response to salinity and humidity under ambient and elevated concentrations of atmospheric CO2. Plant Cell and Environment 20: 1158–1166. [Google Scholar]

- Berlyn GP, Miksche JP, Sass JE. 1976. Botanical microtechnique and cytochemistry. Iowa City: Iowa State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burchett MD, Field CD, Pulkownik A. 1984. Salinity, growth and root respiration in the grey mangrove, Avicennia marina. Physiologia Plantarum 60: 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Burchett MD, Clarke CJ, Field CD, Pulkownik A. 1989. Growth and respiration in two mangrove species at a range of salinities. Physiologia Plantarum 75: 299–303. [Google Scholar]

- Cavender-Bares J, Holbrook NM. 2001. Hydraulic properties and freezing-induced cavitation in sympatric evergreen and deciduous oaks with, contrasting habitats. Plant Cell and Environment 24: 1243–1256. [Google Scholar]

- Choat B, Sack L, Holbrook NM. 2007. Diversity of hydraulic traits in nine Cordia species growing in tropical forests with contrasting precipitation. New Phytologist 175: 686–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough B. 1984. Growth and salt balance of the mangroves Avicennia marina (Forsk.) Vierh. and Rhizophora stylosa Griff. in relation to salinity. Functional Plant Biology 11: 419–430. [Google Scholar]

- Clough BF, Sim RG. 1989. Changes in gas exchange characteristics and water use efficiency of mangroves in response to salinity and vapor-pressure deficit. Oecologia 79: 38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor DJ. 1969. Growth of grey mangrove (Avicennia marina) in nutrient culture. Biotropica 1: 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Downton WJS. 1982. Growth and osmotic relations of the mangrove Avicennia marina, as influenced by salinity. Functional Plant Biology 9: 519–528. [Google Scholar]

- Duke NC. 2006. Australia’s mangroves: the authoritative guide to Australia’s mangrove plants. Brisbane: University of Queensland. [Google Scholar]

- Ewers BE, Oren R, Sperry JS. 2000. Influence of nutrient versus water supply on hydraulic architecture and water balance in Pinus taeda. Plant Cell and Environment 23: 1055–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Ewers FW, Lopez-Portillo J, Angeles G, Fisher JB. 2004. Hydraulic conductivity and embolism in the mangrove tree Laguncularia racemosa. Tree Physiology 24: 1057–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers TJ, Colmer TD. 2008. Salinity tolerance in halophytes. New Phytologist 179: 945–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CM, Stout PR, Broyer TC, Carlton AB. 1957. Comparative chlorine requirements of different plant species. Plant and Soil 8: 337–353. [Google Scholar]

- Khan MA, Aziz I. 2001. Salinity tolerance in some mangrove species from Pakistan. Wetlands Ecology and Management 9: 229–233. [Google Scholar]

- Krauss K, Ball M. 2013. On the halophytic nature of mangroves. Trees 27: 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kriedemann P, Virgona J, Atkin O. 2014. Growth analysis: a quantitative approach. In: Price C, Munns R, eds. Plants in action, 2nd edn. http://plantsinaction.science.uq.edu.au/content/chapter-6-growth-analysis-quantitative-approach [Google Scholar]

- Lambers H, Chapin FS, Pons TL. 1998. Plant physiological ecology . New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Portillo J, Ewers FW, Angeles G. 2005. Sap salinity effects on xylem conductivity in two mangrove species. Plant Cell and Environment 28: 1285–1292. [Google Scholar]

- Lovelock CE, Ball MC, Feller IC, Engelbrecht BMJ, Ewe ML. 2006. Variation in hydraulic conductivity of mangroves: influence of species, salinity, and nitrogen and phosphorus availability. Physiologia Plantarum 127: 457–464. [Google Scholar]

- Mapfumo E. 1994. Measuring the diameter of xylem – a short communication. Australian Journal of Botany 42: 321–324. [Google Scholar]

- Martin KC, Bruhn D, Lovelock CE, Feller IC, Evans JR, Ball MC. 2010. Nitrogen fertilization enhances water-use efficiency in a saline environment. Plant Cell and Environment 33: 344–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcher PJ, Goldstein G, Meinzer FC, et al. 2001. Water relations of coastal and estuarine Rhizophora mangle: xylem pressure potential and dynamics of embolism formation and repair. Oecologia 126: 182–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrisey DJ, Swales A, Dittmann S, Morrison MA, Lovelock CE, Beard CM. 2010. The ecology and management of temperate mangroves. In: Gibson RN, Atkinson RJA, Gordon JDM, eds. Oceanography and marine biology: an annual review. CRC Press, 43–160. [Google Scholar]

- Naidoo G. 1987. Effects of salinity and nitrogen on growth and water relation in the mangrove, Avicennia marina (Forsk.) Vierh. New Phytologist 107: 317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osone Y, Ishida A, Tateno M. 2008. Correlation between relative growth rate and specific leaf area requires associations of specific leaf area with nitrogen absorption rate of roots. New Phytologist 179: 417–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NT, Gupta A, Pandey AN. 2010. Salinity tolerance of Avicennia marina (Forssk.) Vierh. from Gujarat coasts of India. Aquatic Botany 93: 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Payne RW, Murray DA, Harding SA, Baird DB, Soutar DM. 2014. GenStat for Windows, 16th edn. Hemel Hempstead: VSN International. [Google Scholar]

- Poorter H, Remkes C. 1990. Leaf area ratio and net assimilation rate of 24 wild species differing in relative growth rate. Oecologia 83: 553–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasband WS. 1997–2014. ImageJ. Bethesda, MD: US National Institutes of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Reef R, Ball MC, Lovelock CE. 2012. The impact of a locust plague on mangroves of the arid Western Australia coast. Journal of Tropical Ecology 28: 307–311. [Google Scholar]

- Robert EMR, Koedam N, Beeckman H, Schmitz N. 2009. A safe hydraulic architecture as wood anatomical explanation for the difference in distribution of the mangroves Avicennia and Rhizophora. Functional Ecology 23: 649–657. [Google Scholar]

- Santini N, Schmitz N, Lovelock C. 2012. Variation in wood density and anatomy in a widespread mangrove species. Trees 26: 1555–1563. [Google Scholar]

- Santini NS, Schmitz N, Bennion V, Lovelock CE. 2013. The anatomical basis of the link between density and mechanical strength in mangrove branches. Functional Plant Biology 40: 400–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz N, Verheyden A, Beeckman H, Kairo JG, Koedam N. 2006. Influence of a salinity gradient on the vessel characters of the mangrove species Rhizophora mucronata. Annals of Botany 98: 1321–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz N, Robert EMR, Verheyden A, Kairo JG, Beeckman H, Koedam N. 2008. A patchy growth via successive and simultaneous cambia: Key to success of the most widespread mangrove species Avicennia marina? Annals of Botany 101: 49–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoffoni C, Sack L, et al. 2013. Quantifying leaf vein traits. PrometheusWiki. http://prometheuswiki.publish.csiro.au/tiki-index.php?page=Quantifying+leaf+vein+traits. [Google Scholar]

- Shipley B. 2006. Net assimilation rate, specific leaf area and leaf mass ratio: which is most closely correlated with relative growth rate? A meta-analysis. Functional Ecology 20: 565–574. [Google Scholar]

- Smith TJ. 1988. Differential distribution between sub-species of the mangrove Ceriops tagal: competitive interactions along a salinity gradient. Aquatic Botany 32: 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Sobrado MA. 2005. Leaf characteristics and gas exchange of the mangrove Laguncularia racemosa as affected by salinity. Photosynthetica 43: 217–221. [Google Scholar]

- Sobrado MA. 2007. Relationship of water transport to anatomical features in the mangrove Laguncularia racemosa grown under contrasting salinities. New Phytologist 173: 584–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperry JS, Tyree MT, Donnelly JR. 1988. Vulnerability of xylem to embolism in a mangrove vs an inland species of Rhizophoraceae. Physiologia Plantarum 74: 276–283. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez N, Medina E. 2005. Salinity effect on plant growth and leaf demography of the mangrove, Avicennia germinans L. Trees-Structure and Function 19: 721–727. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson PB. 1986. The botany of mangroves. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tyree MT, Velez V, Dalling JW. 1998. Growth dynamics of root and shoot hydraulic conductance in seedlings of five neotropical tree species: scaling to show possible adaptation to differing light regimes. Oecologia 114: 293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner A, Stelzer R. 1990. Physiological responses of the mangrove Rhizophora mangle grown in the absence and presence of NaCl. Plant, Cell & Environment 13: 243–255. [Google Scholar]

- Wong SC, Cowan IR, Farquhar GD. 1979. Stomatal conductance correlates with photosynthetic capacity. Nature 282: 424–426. [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z, Wang W, Tang D. 2007. Effect of different time of salt stress on growth and some physiological processes of Avicennia marina seedlings. Marine Biology 152: 581–587. [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y, Tam NF-Y, Lu C-Y, Wong Y-S. 2005. Effects of salinity on germination, seedling growth and physiology of three salt-secreting mangrove species. Aquatic Botany 83: 193–205. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.