Abstract

Background

End stage lung disease patients who require a thoracic artificial lung (TAL) must be extubated and rehabilitated prior to lung transplantation. The purpose of this study is to evaluate hemodynamics and TAL function under simulated rest and exercise conditions in normal and pulmonary hypertension sheep models.

Methods

The TAL, the MC3 Biolung®, was attached between the pulmonary artery and left atrium in nine normal sheep and eight sheep with chronic pulmonary hypertension. An adjustable band was placed around the distal pulmonary artery to control the percentage of cardiac output (CO) diverted to the TAL. Pulmonary system hemodynamics and TAL function were assessed at baseline (no flow to the TAL) and with approximately 60, 75, and 90% of CO diverted to the TAL. Zero, 2, and 5 mcg/kg/min of intravenous dobutamine were used to simulate rest and exercise conditions.

Results

At 0 and 2 mcg/kg/min, CO did not change significantly with flow diversion to the TAL for both models. At 5 mcg/kg/min, CO decreased with increasing TAL flow up to 28±5% in normal sheep and 23±5% in pulmonary hypertension sheep at 90% flow diversion to the artificial lung. In normal sheep, the pulmonary system zeroth harmonic impedance modulus, Z0, increased with increasing flow diversion. In hypertensive sheep, Z0 decreased at 60% and 75% flow diversion and returned to baseline levels at 90%. TAL outlet blood oxygen saturation was ≥ 95% under all conditions.

Conclusions

Pulmonary artery to Left atrium TAL use will not decrease CO during rest or mild exercise but may not allow more vigorous exercise.

Keywords: Artificial organs; Pulmonary vascular resistance/hypertension; Transplantation, lung; Bioengineering

Introduction

Lung disease continues to be a leading cause of death and disability. Thirty five million Americans are living with some form of chronic lung disease with up to 400,000 deaths per year [1]. Lung transplantation has strengthened as the preferred treatment for end-stage lung disease, and the demand for transplantable lungs continues to steadily outgrow the supply. If a donor lung is not found, there are no options for these patients, as current methods of lung support are not adequate to act as a bridge to lung transplantation.

A total artificial lung (TAL) could serve as a bridge to lung transplantation. The TAL would assume the majority of the respiratory function to support the patient until the transplant. The device would be attached to the pulmonary circulation with blood flow supplied by the right ventricle (RV). The majority of patients requiring a TAL will have some degree of pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular strain. To relieve this, the device could be attached without pulmonary banding to divert flow to the TAL. This would minimize pulmonary artery pressures, but further flow to the TAL may be necessary to maximize gas exchange. Thus, the TAL should be able to tolerate the majority of blood flow without compromising patient hemodynamics. Furthermore, the TAL should allow patient ambulation and rehabilitation prior to lung transplantation.

Previous studies have demonstrated the feasibility of using the TAL in an in-parallel, pulmonary artery (PA) to left atrial (LA) configuration, for respiratory support in normal sheep for up to thirty days [2]. In order to further prepare for clinical trials, hemodynamics and device function were examined during in parallel artificial lung attachment with high blood flows to the TAL in normal and pulmonary hypertension models.

Materials and Methods

Thoracic Artificial Lung

In this study, the MC3 Biolung® (MC3, Inc., Ann Arbor, MI) was used as the TAL (Figure 1). In this device, blood flows through an inlet compliance chamber; enters a central manifold; flows radially through a fiber bundle, which provides gas exchange; and subsequently exits through two symmetric outlets. The membrane bundle is composed of 300 μm OD, polypropylene, hollow fibers (×30 240, Membrana-Celgard, Charlotte, NC) and has a total surface area of 1.7 m2. The inlet compliance chamber is composed of segmented polyurethane, Biospan (Polymer Technology Group, Berkely, CA).

Figure 1.

MC3 Biolung® (compliance chamber not shown).

Animal Models

A total of 17 male sheep averaging 65 ± 6.8 kg were used. The sheep were divided into two groups. Nine were normal, and eight had chronic pulmonary hypertension caused by serial pulmonary embolization. To create the hypertension model, an indwelling central venous catheter was placed and 0.375 gm of Sephadex G-50 (100-300 μm) beads (Sigma-Aldrich CO, St. Louis, MO) were injected into the pulmonary circulation of these sheep daily for 60 days. Prior to these injections, 60 mg of ketorolac (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) was given to reduce the inflammatory response. Pulmonary hemodynamics were recorded routinely using pulmonary artery catheterization. After 60 days of bead injection, the hypertensive sheep were used for artificial lung testing. Their hemodynamic characteristics at rest were as follows: CO = 7.7 ± 1.4 L/min, mean pulmonary artery pressure = 33.2 ± 9.1 mmHg, pulmonary vascular resistance = 2.81 ± 1.1 mmHg/(L/min). Following euthanization, right ventricular hypertrophy was assessed using the RV free wall to left ventricular plus septal weight ratio. The ratio was (0.42±0.04, n=8) compared to a historical group of untreated control animals (0.35±0.01, n=13).

Experimental Procedure

All sheep were treated in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (US National Institutes of Health publication No. 85-23, National Academy Press, Washington DC, revised 1996), and all methods were approved by the University of Michigan Committee for the Use and Care of Animals. Intravenous access was obtained using the brachial vein and a 16 gauge intravenous catheter (Becton, Dickinson Infusion Therapy Systems Inc., Sandy, UT). Anesthesia was induced via 12 mg/kg of intravenous sodium thiopental for normal sheep and a 4 mg/kg intravenous injection of ketamine HCL (Park Davis, Morris Plains, NJ) with a 0.25-0.5 mg/kg injection of diazepam (Hospira Inc, Lake Forest, IL) for pulmonary hypertensive sheep. The sheep were intubated and mechanically ventilated with oxygen using a Narkomed 6000 ventilator (North American Dräger, Telford, PA). Continuous inhalational anesthesia with 1-5.0 vol% isoflurane (Abbot Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) was used. The ventilator was set to a tidal volume of 10 ml/kg and a frequency of 12 breaths/min and was adjusted accordingly to maintain the arterial pCO2 (PaCO2) between 35 and 45 mmHg and peak inspiratory pressure less than 30 cm H2O. Arterial and central venous pressures were monitored continuously via a carotid arterial line and a jugular venous line that were placed under direct visualization. Both catheters were connected to fluid coupled pressure transducers (Abbot Critical Care Systems, Chicago, IL), and the resulting arterial and central venous pressure signals (PArt and PCV) were displayed continuously (Marquette Electronics, Milwaukee, WI).

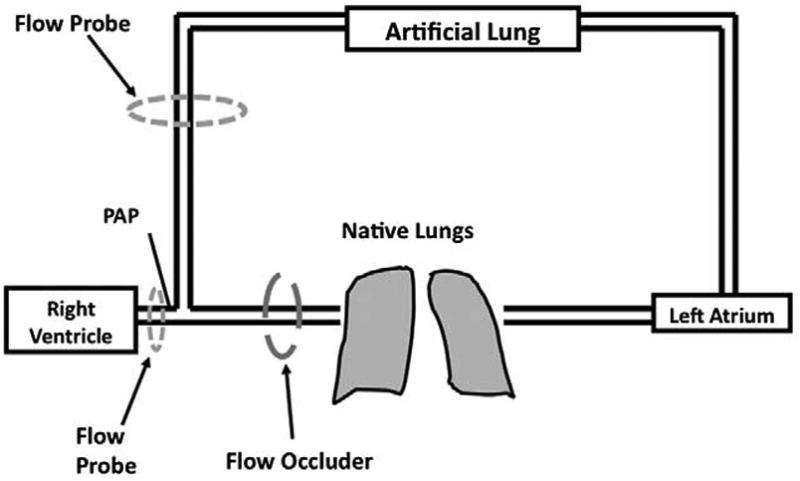

An anterolateral thoracotomy with a 4th rib resection was used to gain adequate exposure. A 60 mg dose of intravenous ketorolac (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) was also given at this time. The pericardium was incised to expose the heart. The PA was dissected from the pulmonic valve to the bifurcation. A pressure catheter (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX) was inserted at the proximal PA for display and recording of the PA pressure (PPA). An ultrasonic perivascular flow probe (Transonic 24AX, Ithaca, NY) was placed around the proximal PA. This allowed for measurement of PA flow (QPA) using a flow meter (Transonic TS420, Ithaca, NY). The conduits for the artificial lung were 18 mm, low porosity woven Dacron vascular grafts (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA). These grafts were solvent bonded to five-eighths inch ID PVC tubing using a PVC glue (12.5 gm of PVC dissolved in 100 mL of cyclohexanone). The animal was anticoagulated with 100 IU/kg of intravenous sodium heparin (Baxter Healthcare Corporation, Deerfield, IL) to achieve activated clotting times of about 400 prior to vascular graft attachment. This level of anticoagulation was maintained throughout the experiments with repeated doses of heparin as needed. Inflow to the Biolung® was created using an end-to-side anastamosis to the PA, distal to the flow probe and PA pressure catheter. Outflow from the device was created using an anastamosis to the left atrium. The device was primed with heparinized saline (10 U/ml) and connected to the two conduits such that the compliance chamber inlet was attached to the proximal PA graft and the Biolung® outlet was attached to the left atrial graft (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Artificial lung attachment and instrumentation.

An adjustable band was placed around the distal aspect of the pulmonary artery using a Rommel tourniquet to control the percentage of cardiac output shunted to the device. An ultrasonic flow probe (Transonic 14XL, Ithaca, NY) was placed around the inflow conduit and connected to a flow meter (Transonic TS410, Ithaca, NY) in order to measure device flow (Qdev). A suction line was attached to the Biolung® gas outlet to maintain -20 mmHg of pressure at the gas inlet, and pure oxygen with 1-5% vaporized isoflurane was used as the sweep gas via the gas inlet. Sweep gas flow rate was set low at 1 L/min initially and adjusted during TAL use to maintain PaCO2 between 30 and 45 mmHg. An intravenous injection of 500 mg of methylprednisolone (Solu-Medrol, Pharmacia and Upjohn Co, NY, NY) was administered prior to allowing flow to the device. Thereafter, clamps on the artificial lung inlet and outlet conduits were removed to allow 10 minutes of blood flow to the artificial lung for equilibration of fluid volumes and a mild inflammatory vasodilation to occur. During this period, 30-40% and 50-60% of cardiac output flowed to the TAL in normal and pulmonary hypertensive sheep, respectively. Thereafter, the conduits were clamped off, and baseline measurements were taken, marking the start of the experiment.

A hemodynamic data set consisting of PArt, PCV, PPA, QPA, and QDev were digitally acquired at a sampling frequency of 250 Hz via a 16-channel circuit board using Labview software (National Instruments, Austin, TX). Rest and exercise were simulated using a continuous infusion of dobutamine (Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL) at concentrations of 0 first and then 2 and 5 mcg/kg/min in random order. At each dose, the hemodynamic data set was acquired at baseline (0% of cardiac output shunted to the TAL) and at targets of 60±5%, 75±5% and 90±7% of cardiac output shunted to the artificial lung. During these conditions, 10 minutes was allowed between each point for equilibration.

At the end of the study, the sheep were euthanized using a 90-150 mg/kg injection of pentobarbital (Fatal-Plus, Vortech Pharmaceuticals, Dearbon, MI).

Data Analysis

Device resistance was calculated using previously described methods [3]. Data from all 17 sheep were included in the data analysis. All comparisons were performed with SPSS (SPSS, Chicago, IL) using a mixed model with the sheep number as the subject variable and flow situation as the fixed, repeated-measure variable. Data sets were truncated to include only entire cardiac cycles in the analysis and are reported as mean±standard error with a p-value ≤ 0.05 being considered significant. The zeroth harmonic input impedance modulus (Z0) was calculated according to the formula:

in which P0 is the mean pulmonary artery (PA) pressure and Q0 is the mean PA blood flow rate. This index is a preferred index of afterload by physiologists due to its independence from cardiac function [4] and because it includes blood flow resistance due to left atrial pressure. Thus, it is less commonly referred to as the “total peripheral resistance.” Previous studies by our group have indicated that this is an excellent index for predicting right ventricular function under high afterload states [5,6].

Results

Sheep Physiology

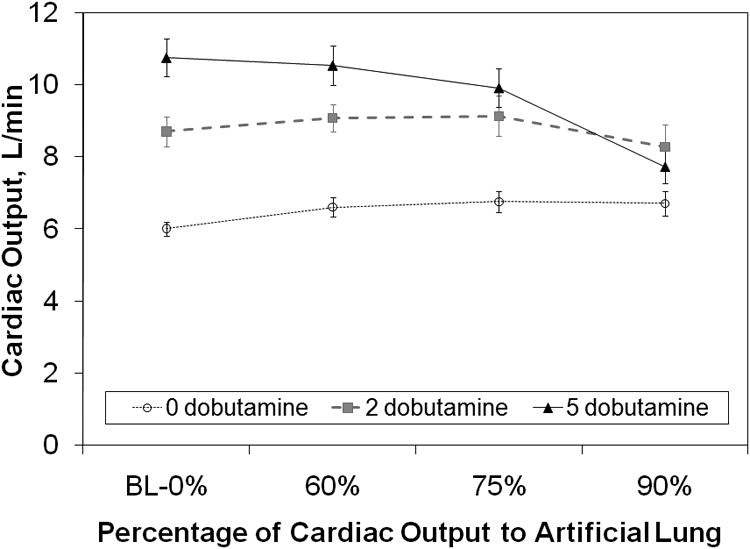

In normal sheep without dobutamine, cardiac output (CO) was 6.02±0.33 L/min baseline (no flow to the TAL) and was maintained at or above this level under all conditions. At 2 mcg/kg/min of dobutamine, CO reached 8.62±0.57 at baseline, and again, there was no significant change in CO for all flow situations tested. At 5 mcg/kg/min, CO was 10.6±0.6 at baseline and decreased with increasing flow to the TAL up to a minimum of 7.53±0.65 with 90% flow to the TAL (Figure 3). This 28±5% drop was significant (p<10-4). Similarly, sheep with pulmonary hypertension did not experience a statistically significant drop in CO under any TAL flow conditions at 0 or 2 mcg/kg/min dobutamine (Figure 4). At 5 mcg/kg/min, baseline CO was 11.9±0.5 L/min but decreased with increasing flow to the artificial lung to a total decrease of 9.22±0.79 (23%±5%, p<0.001).

Figure 3.

Cardiac output vs. the percentage of cardiac output shunted to the artificial lung at all three dobutamine doses in normal sheep. BL = baseline.

Figure 4.

Cardiac output vs. the percentage of cardiac output shunted to the artificial lung at all three dobutamine doses in sheep with chronic pulmonary hypertension. BL = baseline.

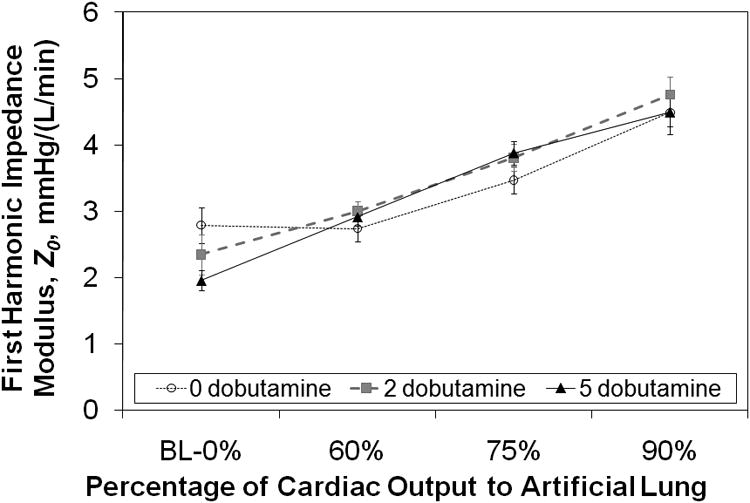

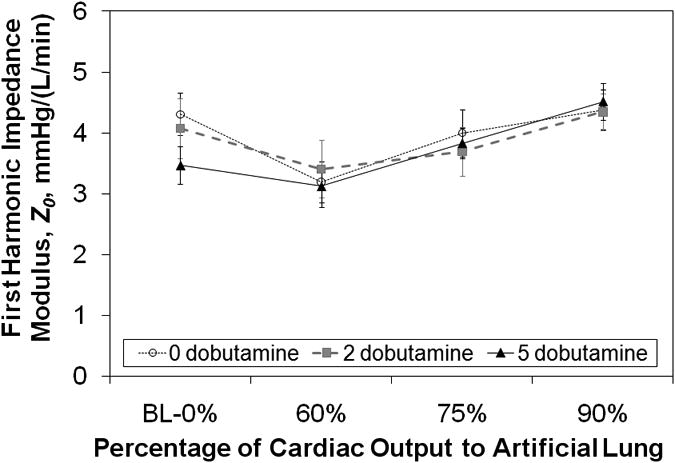

In normal sheep, the zeroth harmonic impedance modulus, Z0, increased with increasing flow to the artificial lung. Statistically significant changes were seen with flows of 75% and 90% for all doses of dobutamine in healthy sheep (Figure 5, 10-10 < p < 0.011). At 5 mcg/kg/min of dobutamine, the impedance was significantly greater for all flows to the artificial lung (p=0.001, p<10-8, and p<10-10). The Z0 at rest was 1.95±0.15 mmHg/(L*min-1) and increased up to 4.49±0.34 mmHg/(L*min-1) with 90% of cardiac output shunted to the TAL (p<10-10). On the other hand, in pulmonary hypertensive sheep, Z0 decreased at least somewhat with 60% flow to the artificial lung at all dobutamine doses, then returned to levels near baseline impedance at 90% (Figure 6). The change was statistically significant only at 2 mcg/kg/min (p=0.03). The baseline impedance at this dobutamine dose was 4.07±0.49 and dropped to 3.41±0.47 with 60% flow to the TAL (p=0.033).

Figure 5.

Pulmonary system zeroth harmonic impedance modulus, Z0, vs. the percentage of cardiac output diverted to the artificial lung in normal sheep. BL = baseline.

Figure 6.

Pulmonary system zeroth harmonic impedance modulus, Z0, vs. the percentage of cardiac output diverted to the artificial lung in sheep with chronic pulmonary hypertension. BL = baseline.

Mean initial PA pressure in normal animals at the 0 mg/kg/min dobutamine baseline was 16.6±1.5 with no significant change at 60% flow to the artificial lung (p=0.99). However, at 75% and 90% flow to the artificial lung the PA pressure significantly increased to 23.4±1.7 (p=0.012) and 29.8±1.6 (p<10-7), respectively. Significant increases were also seen in the higher doses of dobutamine (Table 1), with slightly higher PA pressures than with the 0 dobutamine cases. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) did not change significantly except for at 90% of CO to the TAL where a decrease in MAP was noted (Table 1). In hypertensive sheep, mean pulmonary artery pressure was 33.2±3.2 at the 0 mcg/kg/min dobutamine baseline. The changes in PA pressure followed the same pattern as impedance with an initial decrease at 60% of CO to the TAL. It then increased back to baseline hypertensive levels with increasing flow to the TAL (Table 1). Mean arterial pressure remained stable with very little change during the experiment in all animals with pulmonary hypertension (Table 1).

Table 1. Blood Pressures.

Mean pulmonary artery pressure and mean arterial blood pressure for varied flows to the artificial lung in normal and pulmonary hypertension models. CO = cardiac ouput; TAL = total artificial lung; BL = baseline; mPAP = mean pulmonary artery pressure; MAP = mean arterial pressure.

| 0 mcg/kg dobutamine | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent of CO to TAL | ||||

| Goal | Actual | mPAP, mm Hg | MAP, mm Hg | |

| Normal | BL-0% | 0±0% | 16.6±1.5 | 89±6 |

| 60% | 58±1% | 18.0±1.3 | 85±4 | |

| 75% | 71±1% | 23.4±1.7* | 79±5 | |

| 90% | 90±1% | 29.8±1.6* | 74±5* | |

| Hypertensive | BL-0% | 0±0% | 33.2±3.2 | 80±6 |

| 60% | 61±1% | 23.34±2.7* | 78±5 | |

| 75% | 73±1% | 28.81±2.4 | 83±6 | |

| 90% | 83±2% | 33.5±1.6 | 81±7 | |

| 2 mcg/kg/min dobutamine | ||||

| Percent of CO to TAL | ||||

| Goal | Actual | mPAP, mm Hg | MAP, mm Hg | |

| Normal | BL-0% | 0±0% | 19.5±1.6 | 88±6 |

| 60% | 58±1% | 27.1±1.5 | 84±4 | |

| 75% | 73±2% | 34.2±2.0* | 77±3 | |

| 85-90% | 90±2% | 39.2±2.3* | 74±6 | |

| Hypertensive | BL-0% | 0±0% | 37.1±2.8 | 74±5 |

| 60% | 59±1% | 29.4±2.8* | 84±4* | |

| 75% | 73±1% | 32.4±3.3 | 84±3* | |

| 90% | 85±2% | 39.8±2.9 | 77±5 | |

| 5 mcg/kg/min dobutamine | ||||

| Percent of CO to TAL | ||||

| Goal | Actual | mPAP, mm Hg | MAP, mm Hg | |

| Normal | BL-0% | 0±0% | 20.5±1.1 | 92±7 |

| 60% | 58±1% | 30.3±1.4* | 78±9 | |

| 75% | 73±1% | 38.0±1.9* | 82±8 | |

| 90% | 88±1% | 34.6±3.3* | 59±8* | |

| Hypertensive | BL-0% | 0±0% | 40.9±2.4 | 79±5 |

| 60% | 61±2% | 32.9±3.8* | 87±5 | |

| 75% | 72±1% | 38.5±3.0 | 88±7 | |

| 90% | 84±2% | 40.7±3.4 | 80±8 | |

p-value < 0.05.

Device Function

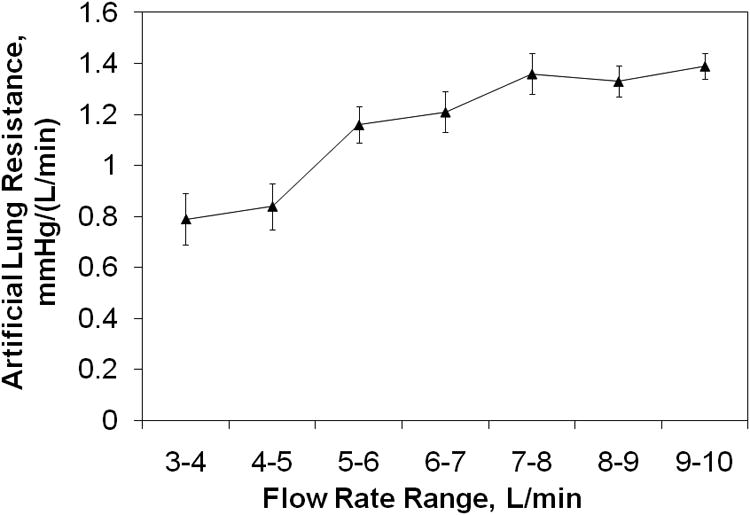

Device resistance is shown in Figure 7, pooled at different flow rate ranges. Average hemoglobin was 9.3 ± 0.7 in these evaluations. Resistance increased linearly with increasing flow rate, increasing from 0.79 mmHg/(L/min) at 3-4 L/min up to 1.39 mmHg/(L/min) at 9-10 L/min. Arterial saturations were maintained above 95% under all conditions. Finally, all devices functioned without failure for the entire acute (4-5 hour) experiment in all animals with no clot formation noted at the end of the procedures.

Figure 7.

Biolung® resistance as a function of flow rate.

Comment

Total artificial lungs are intended to act as a bridge to lung transplantation. Thus, these devices should be designed to provide the majority of gas exchange, even during periods of ambulation and rehabilitation at elevated cardiac outputs. The right ventricle should be able to deliver the majority of cardiac output to the TAL at rest and during mild exercise. In most pulmonary diseases, both gas exchange and hemodynamic abnormalities are present, and the amount of TAL blood flow will depend on the specifics of the pathology and may change with time in a given patient. Ideally, flow to the TAL should be maximized for better respiratory support up to the point where it begins to cause right ventricular dysfunction.

In this study, CO did not change significantly with increasing flow to the TAL with either zero or two mcg/kg/min of dobutamine When dobutamine was 5 mcg/kg/min, however, baseline CO was highly elevated to 10.8±0.5 L/min (normal) and 11.9±0.5 L/min (hypertensive), and CO decreased with increasing TAL flow. In normal sheep, this decrease is minor up to 75% of blood flow to the TAL. In hypertensive sheep, the baseline CO is higher, and the drop in CO with flow diversion to the TAL is steeper, reaching statistical significance at 60% flow to the TAL. At 90% flow to the TAL, CO fell 23%.

Overall, CO tends to fall more steeply when the baseline CO is higher and the increase in pulmonary system Z0 is greater. As seen in Figures 5 and 6, the pulmonary system Z0 depends on the hemodynamics of native pulmonary circulation as well as how much flow is diverted to the TAL. During PA to LA, in parallel TAL attachment, the impedance of the combined pulmonary and artificial lung system is always less than that of the natural pulmonary vascular resistance if there is no PA banding. Thus, RV afterload is also decreased. This decrease is more significant in subjects with pulmonary hypertension [7], and thus, PA to LA attachment is ideal for patients with significant pulmonary hypertension and RV dysfunction [8]. However, as a greater amount of flow is diverted to the artificial lung, the impedance of the combined system can rise above that of the natural pulmonary circulation if the TAL impedance is larger than the natural lung impedance. Thus, Z0 increased with increasing flow diversion in normal sheep because the TAL impedance is greater than that of the normal natural lung. In hypertensive sheep, natural lung impedance is much greater. Thus, Z0 decreased with 60% flow diverted to the TAL when there was little to no PA banding. However, as the PA was banded and additional flow was diverted to the TAL, Z0 rose with increasing flow diversion to the TAL. With 100% flow to the TAL, Z0 had returned to baseline values.

The extent of CO change with TAL attachment is dependent on the baseline CO, or exercise state, in addition to the Z0. Kim et al. [5] and Kuo et al. [6] studied this relationship previously for sheep at resting CO. They both found that sheep with larger baseline CO had larger changes in CO for a given increase in Z0. This is likely due to the effect of CO and Z0 on right ventricular myocardial oxygen demand. Right ventricular oxygen demand is linearly related to its total mechanical energy expenditure (TME) [9]. In brief, TME is elevated by right ventricular pressure and right ventricular flow output. Ultimately, elevations in Z0 increase right ventricular pressure, TME, and the oxygen supply required to maintain CO. Moreover, this increase in TME increases with initial CO. Thus, sheep with higher CO experience a greater oxygen demand for a given increase in Z0. If this increase cannot be met, the CO decreases, most likely until oxygen supply and demand are matched.

In this study, up to 9.8 L/min of flow could be maintained through the artificial lung with 75% of CO to the TAL and Z0 approximately 4 mmHg/(L/min). A maximum of approximately 8 L/min could be maintained with 100% of CO to the TAL and Z0 = 4.8 mmHg/(L/min). Clinically, this effect would manifest itself primarily as reduced exercise tolerance if flows to the TAL are larger than 75% of CO. This effect would be worsened with more resistive artificial lung attachment modes, including proximal PA to distal PA attachment or attachment using longer, smaller bore cannulae, or with more resistive artificial lungs. It could also be ameliorated with less resistive devices and anastomoses.

The effect of hypertension and subsequent RV remodeling appears to have a small effect relative to Z0 and the baseline. The drop in cardiac output at 90% flow to the TAL is similar for the two groups. However, all sheep in this study had compensated for their hypertension and began the study with normal, stable cardiac output. The reaction of the right ventricle would undoubtedly be different after significant acute increases in pulmonary vascular resistance, such as during acute exacerbations of chronic lung diseases or after acute pulmonary embolism.

For the most part, systemic blood pressures remained near normal under all conditions (Table 1). The one exception was in normal animals at 5 mcg/kg/min and 90% of cardiac output to the TAL. Since the lungs are the main site of vasoactive substance processing, significant exclusion of the lung can lead to significant drops in systemic vascular tone and blood pressure [10]. This did not seem to be a problem over the short periods of time studied here. However, the significant drop in MAP in the normal sheep suggests that further reductions in blood pressure may have occurred at 90% flow occlusion if longer periods of time were tested. Complete exclusion of the pulmonary bed could also predispose the lung to thrombosis, as has been demonstrated in veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation with minimal cardiac ejection across the pulmonary bed [11]. Thus, flow of more than 85-90% of the cardiac output shunted to the artificial lung are not recommended in the PA-LA configuration due to the combination of reduced exercise tolerance shown here and the potential for low blood pressure and thrombosis.

Finally, device resistance remains low with various flows to the artificial lung and performance remains good even with 90% of the cardiac output flowing through the artificial lung. This indicates that the MC3 Biolung® design is completely suitable for high flows due to PA banding and exercise.

Graft positioning during exercise was not studied here but must be dealt with carefully during clinical applications. Both grafts and TAL must be well anchored during patient exercise in order to maintain graft position and avoid kinking or device detachment. Previously, our group studied 30-day attachment of artificial lungs in sheep [2]. In this study, graft position was maintained largely by tightly securing both the grafts and the TAL to the sheep's flank. For the most part, activity was minimal. The sheep changed posture (stood, sat, and rolled on their sides). However, recovery from anesthesia typically included more vigorous exertion and in one case, a sheep jumped out of its cage. For the most part, movement occurred without complication. However, in one case, a sheep died at day 10 due to bleeding at the anastomosis site. Thus, this will always be a concern, and patients must be carefully monitored. Kinking of the grafts, however, was not an issue. Despite changes in sheep position, blood flows were largely constant through the device.

In conclusion, the right ventricle can maintain adequate perfusion to the artificial lung in a PA-LA configuration with up to 75% of blood flow to the TAL even with elevated CO. When an attempt is made to divert 85-90% of the CO, the cardiac output drops by 20-30% due to right ventricular dysfunction. The MC3 Biolung® can, furthermore, provide adequate gas exchange at these flow rates. Thus, the MC3 Biolung® is fully capable of supporting patients with pulmonary hypertension in rest and mild activity states, but it may not allow for more vigorous exercise. This amount of activity should be acceptable for lung transplant candidates, allowing them to ambulate and participate in daily physical and occupational therapy exercises in preparation for their transplant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL069420)

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CO

Cardiac Output

- LA

Left Atrium

- MAP

Mean Arterial Pressure

- PA

Pulmonary Artery

- PArt

Arterial Pressure

- PCV

Central Venous Pressure

- PPA

Pulmonary Artery Pressure

- Qdev

Device Flow

- QPA

Pulmonary Artery Flow

- RV

Right Ventricle

- TAL

Total Artificial Lung

- TME

Total Mechanical Energy Expenditure

- Z0

Zeroth Harmonic Input Impedance Modulus

Footnotes

Disclosures and Freedom of Investigation: The total artificial lung devices were supplied by MC3® Incorporated. Dr. Bartlett is a part owner and has a financial interest in this company. The authors had full control of the design of the study, methods used, outcome parameters, analysis of data and production of the written report.

References

- 1.American Lung Association. [Accessed May 15, 2009]; Available at: http://www.lungusa.org.

- 2.Sato H, Hall CM, Lafayette NG, et al. Thirty-day in-parallel artificial lung testing in sheep. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1136–43. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook KE, Perlman CE, Seipelt R, Backer CL, Mavroudis C, Mockros LF. Hemodynamic and gas transfer properties of a compliant thoracic artificial lung. ASAIO J. 2005;51:404–11. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000169707.72242.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nichols WW, O'Rourke MF. McDonald's blood flow in arteries. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim J, Sato H, Grant W, et al. Cardiac output during high afterload artificial lung attachment. ASAIO J. 2009;55:73–77. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e318191500a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuo AS, Sato H, Reoma JL, Cook KE. Pulmonary system impedance and right ventricular function. Cardiovascular Engineering. 2009;9:153–160. doi: 10.1007/s10558-009-9083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perlman CE, Cook KE, Seipelt R, Mavroudis C, Backer CL, Mockros LF. In vivo hemodynamic responses to thoracic artificial lung attachment. ASAIO J. 2005;51:412–25. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000170095.94988.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boschetti F, Perlman CE, Cook KE, Mockros LF. Hemodynamic effects of attachment modes and device design of a thoracic artificial lung. ASAIO J. 2000;46:42–8. doi: 10.1097/00002480-200001000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elberry JR, Lucke JC, Feneley MP, et al. Mechanical determinants of myocardial oxygen consumption in conscious dogs. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:H609–20. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.2.H609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eya K, Tatsumi E, Taenaka Y, et al. Importance of metabolic function of the natural lung evaluated by prolonged exclusion of the pulmonary circulation. ASAIO J. 1996;42:M805–9. doi: 10.1097/00002480-199609000-00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orfanos SE, Hirsch AM, Giovinazzo M, Armaganidis A, Catravas JD, Langleben D. Pulmonary capillary endothelial metabolic function in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. J of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2008;6:1275–1280. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adamson RM, Dembitsky WP, Daily PO, Moreno-Cabral R, Copeland J, Smith R. Immediate cardiac allograft failure ECMO versus total artificial heart support. ASAIO J. 1996;42:314–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]