Abstract

Purpose

The Cox-maze III procedure (CMP) has achieved high success rates for the surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation (AF). In 2002, our group introduced a simplified CMP, in which most incisions were replaced with linear lines of ablation using bipolar radiofrequency and cryoenergy. This operation, termed the CMP-IV, has significantly shortened operative times and allowed for a minimally invasive approach. This report evaluates our results in 100 consecutive patients undergoing a stand-alone CMP-IV.

Methods

Data were collected prospectively on 100 patients (mean age, 56±10 years) who underwent a CMP-IV from January 2002 through May 2010. All patients were available for follow-up with a mean follow-up of 17±10 months. Electrocardiograms or 24-h Holter monitorings were obtained at 6, 12, and 24 months. Data were analyzed using a longitudinal database containing over 380 variables.

Results

Thirty-one percent of patients had paroxysmal AF, with the remainder having persistent (6%) or longstanding persistent AF (63%). The mean preoperative duration of AF was 7.4±6.7 years. The mean left atrial diameter was 4.7±1.1 cm. In this group, 40 patients had failed with a mean of 2.6±1.3 catheter ablations. Mean aortic cross-clamp time was 41±13 min. There was one postoperative mortality. Postoperative freedom from AF was 93%, 90%, and 90% at 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively. Freedom from AF off antiarrhythmic medication was 82%, 82%, and 84% at 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively.

Conclusion

The less invasive CMP-IV has a high single procedure success rate, even with improved follow-up and stricter definitions of failure.

Keywords: Ablation, Arrhythmia, Atrial fibrillation, Cox-maze procedure, Surgery

1 Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia in the world with an increasing incidence in our aging population. It is associated with significant morbidity and mortality secondary to its detrimental sequelae [1, 2]. AF accounts for about 25% of all strokes in patients older than 80 years and increases a person's risk of stroke by fivefold [3]. The limitations of pharmacological therapy for AF have led to the development and proliferation of interventional approaches to treat this arrhythmia over the last two decades [4–7]. These have included catheter ablation and surgery.

Following extensive experimental investigation, Dr. Cox introduced the maze procedure (CMP) for the surgical treatment of AF at our institution in 1987 [7]. The final version termed the Cox-maze III procedure proved to be highly efficacious with excellent long-term results and became the gold standard for the surgical treatment of AF for more than a decade [8]. In a long-term study of nearly 200 patients from our institution, the overall freedom of symptomatic AF was 97% at late follow-up [9]. For patients undergoing a stand-alone procedure, 80% of patients were free from symptomatic AF and antiarrhythmic drugs at late follow-up over 10 years following surgery. While these were excellent results, follow-up did not adhere to present guidelines and few patients had electrocardiograms (ECG) or prolonged monitoring. This makes a comparison to the modern series difficult. Moreover, the definition of AF recurrence did not adhere to the present accepted standards. The recent consensus statement for ablation of AF defined success as freedom from AF, atrial flutter, or atrial tachycardia off antiarrhythmic drugs and requires a minimum follow-up of 12 months. Recurrence was defined as any episode lasting over 30 s [10]. The minimal acceptable follow-up was felt to be a 24-h Holter monitoring.

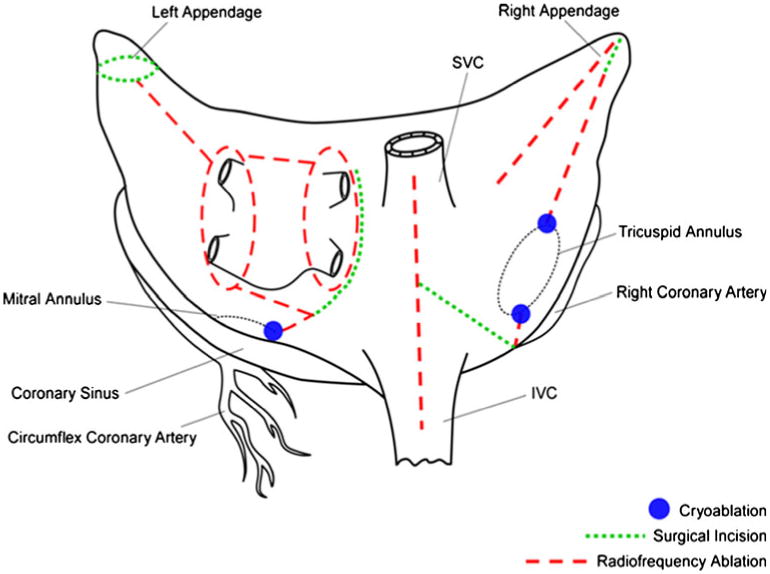

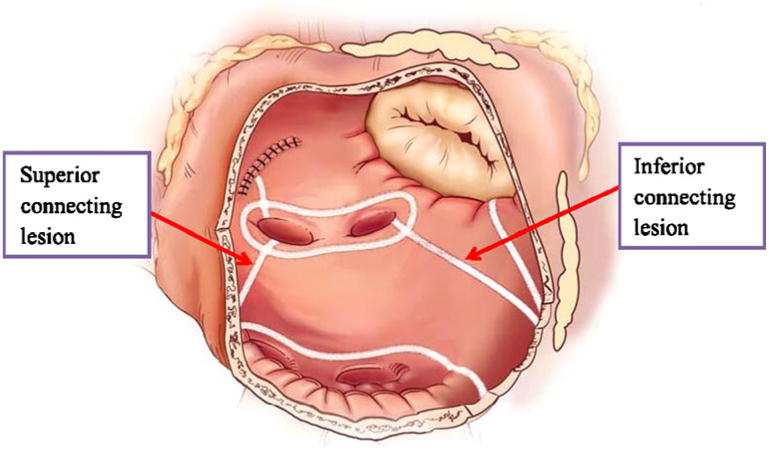

Despite its high success rate, the CMP-III was not widely adopted by cardiac surgeons due to its technical complexity and invasiveness. In an effort to simplify and shorten the procedure, groups around the world, including our own, have used various alternative energy sources to create linear lines of ablation to replace most of the incisions of the original cut and sew CMP-III [11–14]. After experimental studies in our laboratory, bipolar radio-frequency energy was adopted clinically at our institution because of its ability to safely and quickly create reliable transmural lines of ablation while minimizing the risk of collateral damage to surrounding structures [15–17]. A new iteration of the CMP was introduced by our group in 2002: the CMP-IV, which used bipolar radiofrequency ablation to replace most of the original incisions (Fig. 1) [18]. The CMP-IV initially isolated the pulmonary veins and had only a single connecting ablation line between the right and left inferior pulmonary veins, termed as non-box lesion set. However, in 2004, a second connecting lesion was added between the two superior pulmonary veins, which completely isolated the posterior left atrium, termed as the box lesion set (Fig. 2). While we have previously reported excellent initial results with this procedure, the majority of these patients underwent concomitant cardiac surgical procedures [9, 19, 20]. This report examines for the first time results for the stand-alone procedure in patients without concomitant cardiac pathology and represents the largest report of stand-alone CMP-IV in the literature. In this series, a more precise and stricter follow-up regimen was implemented, with all patients having either ECG or 24-h Holter monitoring at 3, 6, and 12 months and annually thereafter.

Fig. 1. Cox-maze IV procedure. SVC superior vena cava, IVC inferior vena cava, Lt left, RF bipolar radiofrequency, Rt right (Adapted from Lall S.C., Melby S.J., Voeller R.K., Zierer A., Bailey M.S., Guthrie, T.J,. et al. [20]).

Fig. 2. Left atrial lesion set of the Cox-maze IV procedure. RF radiofrequency. Adapted from Damiano, R.J. Jr., Schwartz, F. H., Bailey, M.S., Maniar, H.S., Munfakh, N.A., Moon, M.R., et al. [38].

In previous reports, we have shown that the CMP-IV had significantly shorter operating times and lower morbidity than the traditional cut-and-sew CMP-III [20, 21]. In a propensity-matched population, we also demonstrated that the CMP-IV had similar freedom from AF at 6 and 12 months when compared to the CMP-III, despite more aggressive follow-up [20]. In this study, our prospectively collected data were analyzed to evaluate the long-term results of the CMP-IV in the treatment of lone AF in 100 consecutive patients.

2 Methods

From January 2002 through May 2010, 100 patients underwent a stand-alone bipolar radiofrequency ablation-assisted Cox-maze IV. Atrial fibrillation was defined as paroxysmal, persistent or long-standing persistent per recent guidelines [12]. All procedures were performed by the same surgeon (R.J.D). A bipolar radiofrequency clamp was used in all cases. In 72 patients (72%), the AtriCure Isolator systems, Isolator I, II, and Synergy series (AtriCure, Inc., Cincinnati, OH) were used. In 28 patients (28%), the procedure was performed with either the Medtronic Cardioblate BP or LP system (Medtronic, Inc., Minneapolis, MN). All of these devices used alternating current to produce coagulative thermal injury with the energy being applied between electrodes embedded in the jaws of the devices. Algorithms measuring tissue conductance or impedance were used to determine the time of ablation and to estimate when a transmural lesion had been achieved. This study was approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Informed consent and permission for release of information were obtained from all patients.

2.1 Surgical technique

The CMP-IV was performed as a stand-alone procedure using cardiopulmonary bypass with bicaval cannulation. Patient underwent either a median sternotomy (n=79) or a right minithoracotomy (n=21) [22]. All patients underwent intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography, and cardioversion was performed when needed after the presence of a left atrial appendage clot was excluded. Pacing thresholds were measured from the superior and inferior right and left pulmonary veins, which were then isolated by placing the jaws of the bipolar radiofrequency ablation device on the surrounding cuff of atrial tissue. After ablation, electrical isolation was documented, when possible, by pacing from each pulmonary vein with a stimulus strength of 20 mA to confirm exit block. In all patients in whom pacing could be performed (93%), ablation was continued until exit block was documented from each pulmonary vein. In patients undergoing a right minithoracotomy, pacing was performed only from the right pulmonary veins.

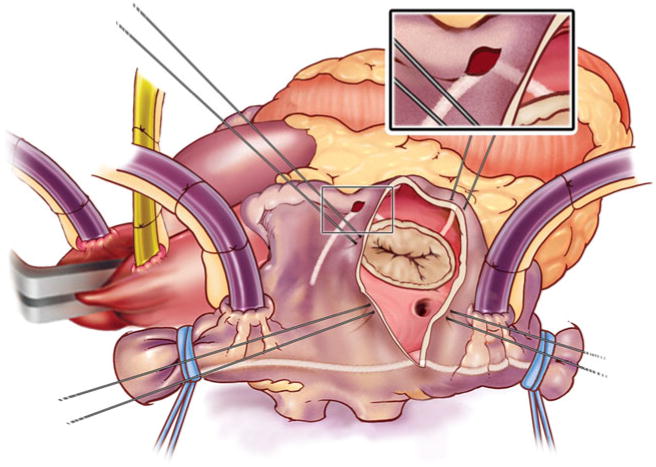

Patients were cooled to 34°C and the right atrial lesion set was done on the beating heart (Fig. 3). Our technique has been previously described [18]. A single incision was usually made in the right atrial free wall, but recently a three purse-string approach has been adopted to eliminate this incision in some patients. All ablations were performed with the bipolar radiofrequency clamp except for two endocardial ablation lines to the tricuspid annulus. These were performed with a linear cryoprobe placed on the endocardium and cooled to −60°C for 2–3 min.

Fig. 3. Right atrial lesion set of the Cox-maze IV procedure.

The left atrial lesion set was performed under cardioplegic arrest using cold blood cardioplegia (Fig. 2). Initially, the heart was retracted and the left atrial appendage was amputated. Through this opening, the bipolar clamp was used to create an ablation line into one of the left pulmonary veins. A small left atriotomy was then performed and the remainders of the ablation lines were completed with the bipolar clamp. Cryoablation was used to connect the isthmus ablation line to the mitral annulus. In patients undergoing a right minithoracotomy, cryoablation was more extensively applied to complete the posterior left atrial isolation and the left atrial appendage was oversewn from the inside [22].

2.2 Postoperative care and follow-up

The clinical demographics and postoperative outcome variables were collected prospectively in a longitudinal database. Prophylactic class I or III antiarrhythmic medication, as well as warfarin were initiated in most patients in the early postoperative period. Patients with postoperative atrial tachyarrhythmias (ATAs) were electrically cardioverted as needed. If patients were in sinus rhythm, antiarrhythmic drugs were discontinued after 2 months. Warfarin was discontinued at 3 months if patients were free of ATAs on prolonged monitoring. Echocardiograms were also obtained to rule out any atrial stasis or thrombus before discontinuation of warfarin.

Follow-up was conducted by scheduled office visits at 3, 6, and 12 months and annually thereafter. At each visit, history and physical examination and electrocardiogram were obtained. Since 2006, when new follow-up guidelines were established, 24-h Holter monitoring or pacemaker interrogation was obtained in 95% of patients. In the entire series, 67% of patients obtained prolonged monitoring during the first year of follow-up. Late recurrence was defined as any episode of AF, atrial flutter, or atrial tachycardia that lasted longer than 30 s. Any patient requiring an interventional procedure after 3 months was deemed a permanent failure. Patients were only considered to be a success if they were both free of AF and free of antiarrhythmic drugs (class I or III).

2.3 Statistical analysis

Continuous data were expressed as mean±standard deviation, unless otherwise specified and categorical data were expressed as counts and proportions. All data analysis was performed with the SPSS system for statistics (SPSS 11.0 for Windows, SPSS, Chicago, IL).

3 Results

3.1 Patient demographics

Patient demographics are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 56±10 years (range, 29–75) with 76% males. The mean duration of preoperative AF was 7.4±6.7 years (range, 0.1–28), with 31% paroxysmal, 6% persistent, and 63% long-standing persistent AF. Left atrial diameter was measured by echocardiography with a mean diameter of 4.7±1.1 cm (range, 2.5–8.0). The common reasons for surgical referral were failure of medical therapy in 53% and transient ischemic attacks or stroke in 12%. Forty percent of patients had failed a previous catheter ablation with a mean number of 2.6±1.3 (range, 1–6) interventions.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

| Variables | (n = 100) |

|---|---|

| Preoperative | |

| Age (years) | 56±10 |

| Male gender | 76% |

| AF duration (years) | |

| Mean | 7.5±6.7 |

| Median | 6.0 |

| Paroxysmal AF | 31% |

| NYHA Class 3 or 4 | 22% |

| Sleep apnea | 18% |

| Indication for surgery | |

| Failed medical therapy | 53% |

| Stroke or TIA | 12% |

| Failed catheter ablation | 40% |

| Operative | |

| Mean CCT (minutes) | 41±13 |

| Mean CPB time (minutes) | 133±28 |

| Box lesion around PVs | 78% |

| LA diameter (cm) | 4.7±1.1 |

AF atrial fibrillation, CCT aortic cross-clamp time, CPB cardiopulmonary bypass, LA left atrium, NYHA New York Heart Association, PVs pulmonary veins, TIA transient ischemic attack

3.2 Perioperative results

The overall 30-day mortality was 1%. There were no intraoperative deaths. The only mortality occurred in a woman who suffered a pulmonary embolus on the day of discharge (postoperative day 19), despite being fully anti-coagulated. The mean aortic cross-clamp time was 41±13 min. This compares to a cross-clamp time of 93±34 min (p<0.001) in our previously published experience with the cut-and-sew CMP-III [9]. Seventy-eight percent of patients received a complete box lesion set isolating the entire posterior left atrium. Patients had a median length of stay at the intensive care unit of 2 days (range, 1–7) and a median length of hospital stay of 7 days (range, 4–53). There was one postoperative stroke (1%). There were no re-operations for bleeding, episodes of mediastinitis or renal failure, and no implantations of an intra-aortic balloon pump. Early postoperative atrial arrhythmias were documented in 40% of patients. Seven patients (7%) required a postoperative pacemaker implantation. Two of the patients needed a pacemaker for chronotropic incompetence and five patients required a pacemaker for slow junctional rhythms.

3.3 Late follow-up

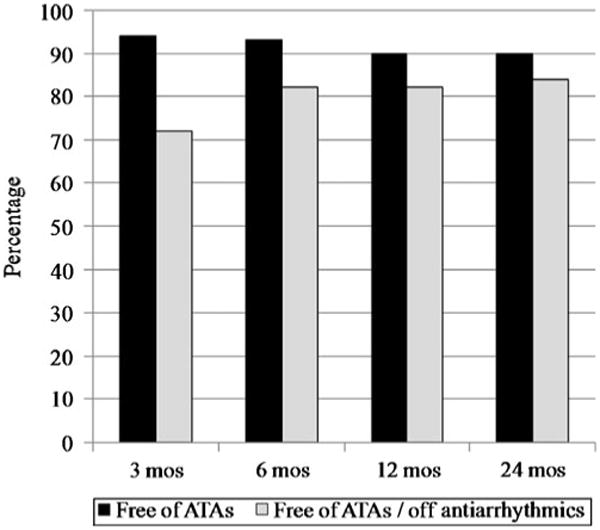

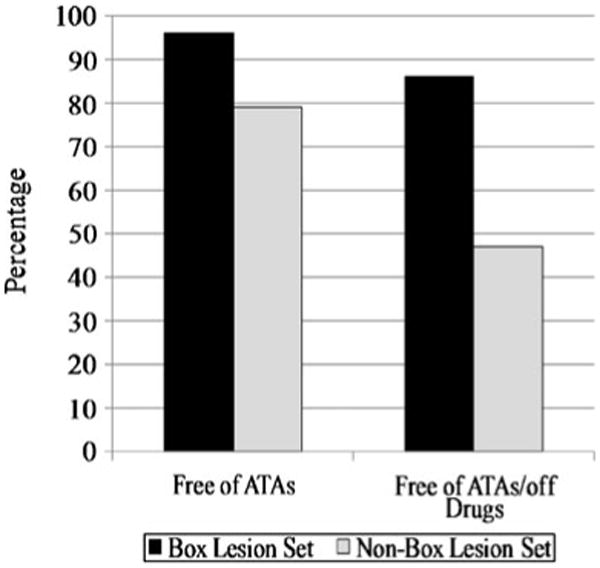

No patient was lost to follow-up at 12 months; follow-up was available on 50% of patients at 24 months. The mean follow-up in the series was 17±10 months. The freedom from AF recurrence was 94%, 93%, 90%, and 90% at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively. The freedom from both AF and antiarrhythmic drugs was 72%, 82%, 82%, and 84% at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively (Fig. 4). In patients receiving a complete box lesion set (n=78), freedom from AF was 96% and freedom from AF off antiarrhythmic drugs was 86% after 1 year (Fig. 5). This compares to patients receiving a non-box ablation set (n=22) with a freedom of AF of 79% and a freedom from AF off antiarrhythmic drugs of 47%. There was no significant difference in success rate off antiarrhythmic drugs for patients with paroxysmal AF (68%) versus patients with persistent or long-standing persistent AF (72%, p=0.886). There were no late strokes in this series. At 24 months, 84% of patients were free of anticoagulation therapy with warfarin. A comparison to the historical cohort of CMP-III patients is difficult because those patients were not followed according to present guidelines and virtually none of the patients had ECG follow-up at 6, 12, and 24 months. The recurrent arrhythmias were atrial fibrillation (80%), atrial flutter (10%), and atrial tachycardia (10%).

Fig. 4. Overall freedom from atrial fibrillation (AF) and freedom from AF off antiarrhythmic drugs at follow-up.

Fig. 5. Freedom from AF on and off antiarrhythmic drugs between the box vs. non-box lesion sets at 12 months.

4 Discussion

The Cox-maze procedure has had the best late results of any single interventional procedure for atrial fibrillation [9, 23, 24]. It was developed at our institution, and our experience over the last 20 years has led to a continual evolution of the original operation. The lesion set in the “cut and sew” CMP-III was empirically designed to interrupt all possible macroreentrant circuits [7, 25, 26]. The CMP-IV was designed to simplify this operation by using bipolar radiofrequency to replace most of the original incisions. Our results have shown that it has significantly decreased operative time and perioperative morbidity while preserving the high efficacy of the traditional procedure [20]. Bipolar radiofrequency energy was chosen because of its ability to reliably create transmural lesions in animal models [16, 17]. Linear ablations were able to be performed in 5–10 s as opposed to minutes required for other energy sources. Finally, the risk of collateral damage that has been reported with unipolar, unfocused energy sources is minimized by the focused application of energy within the jaws of the clamp [27]. Cryoablation was used in all locations not amenable to clamping: the tissue near the mitral and tricuspid annuli and occasionally, the coronary sinus. This energy source has been used safely and reliably for decades in arrhythmia surgery and has the advantage over heat-based ablation in that it preserves collagen and the structural integrity of myocardial and valvular tissue [28, 29].

At the present time the interventional treatment of choice for patients with symptomatic and drug-refractory lone AF is catheter ablation, based principally on isolating the pulmonary veins [5, 6, 10, 30]. However, results have been variable with single procedure success rates varying between 16 and 84% [10]. Moreover, certain patient subgroups have done poorly, particularly patients with longstanding persistent AF and large atria [31, 32]. In the recent consensus statement, the indication for surgical ablation include patients with symptomatic medically refractory AF who have failed one or more catheter ablations, who are not candidates for catheter ablation, or who prefer a surgical approach. This report examines the results with surgical ablation using a complete maze lesion set and modern definitions of AF recurrence and follow-up guidelines.

While our group has published extensively on our experience, prior reports have not followed recent guidelines in terms of recommended follow-up and definition of failure [12]. Moreover, our previous reports have generally been dominated by patients undergoing concomitant surgical procedures, which may not be comparable to the population of patients currently undergoing catheter ablation for lone AF.

This present series of 100 consecutive patients undergoing a stand-alone CMP-IV demonstrated an excellent long-term success rate with 90% of patients being free from AF and 84% being free from AF and off antiarrhythmic drugs after 2 years. As opposed to catheter ablation and surgical pulmonary vein isolation, the CMP-IV had similar success rates in paroxysmal and persistent AF [31, 32]. This compares favorably with our historical data from the CMP-III in which only symptomatic follow-up was obtained [9, 20]. While follow-up in the historical series was longer and showed a freedom from AF and antiarrhythmics of 80%, many of these patients did not have electrocardiographic or Holter monitoring to determine their actual heart rhythm. The CMP-IV requires a biatrial lesion set and is proven to have the same success rates in all types of AF. The attempt to decrease complexity by focusing on surgical pulmonary vein isolation with or without extended left atrial lesions is at the cost of efficacy with a 1-year drug-free success rate of about 65% [33, 34].

A major concern about a surgical approach for treatment of lone AF is its invasiveness. The CMP-IV has significantly decreased cardiopulmonary bypass time as well as major complication rates when compared to our prior experience with the CMP-III. Moreover, with current technology, the procedure can be performed with a minimal invasive approach via a right minithoracotomy without compromising its efficacy [22]. This simplified procedure also makes it easier for a larger number of surgeons to adapt to this technique.

In our entire series, there was only one early stroke and no late strokes noted. Moreover, 84% of patients were off anticoagulation therapy after 24 months. Considering the serious possible side effect of warfarin, especially the higher risk of oral anticoagulation-associated intracranial hemorrhage, this fact might be critical in improving long-term quality of life [35].

Any surgical approach has to compare favorably to the less invasive percutaneous catheter ablation to be considered an alternative in the treatment of lone AF. In a recent review including 19 studies, success rates of catheter ablation ranged from 6% to 93% [36]. The freedom from AF recurrence rates were slightly lower for paroxysmal AF treated with catheter ablation when compared to our results. A closer examination of patient groups suggested a success rate for a single procedure ranging from 22% to 45% in patients with persistent or long-standing persistent AF, with most centers reporting an efficacy of less than 30% in this group [10]. With 90% freedom from AF after a stand-alone CMP-IV, there was no significant difference in success rates between types of AF in our series.

There were several limitations to this study. While follow-up improved considerably over time, a third of patients only underwent follow-up with ECGs. Few patients had more prolonged monitoring than a 24-h Holter. This has likely resulted in an underestimation of the actual failure rate. However, this patient cohort has been well monitored compared to previous reports in literature and no patient was lost to follow-up. Overall, our series was not identical with regard to lesion set and surgical approach in all 100 patients. However, the only difference in the lesion set was the addition of a single extra ablation line later in our experience to allow for complete isolation of the posterior left atrium, termed as a box lesion set. The vast majority of patients received a box lesion set, which resulted in a significantly higher freedom from AF recurrence compared to an incomplete isolation of the posterior atrial wall [37]. The lower success rate in patients that did not receive a complete box lesion set has lead to an underestimate of the true success rate of the currently performed CMP-IV technique. The development of a minimally invasive approach via a right minithoracotomy had no influence on the lesion set or the success rate [22]. However, cryoablation was more extensively applied in these cases. Also, the mechanisms for AF recurrence were not well defined. One possible explanation of failure would be a lack of transmurality of some lesions, since only the efficacy of the pulmonary vein isolation was tested. However, previous experimental investigations in our laboratory have shown reproducible reliable transmural lines of ablation with bipolar radiofrequency energy [16, 17]. The question remains unanswered whether our failure rate was due to technical difficulties in creating a complete Cox-maze lesion set or inherent atrial pathology.

Understanding the methods of failure will be essential to improve surgical results. In our overall series a recent multivariate analysis of predictors of failure in 282 patients revealed that increased left atrial diameter, early ATAs within the first month following surgery, and failure to isolate the entire posterior left atrium predicted recurrence of AF [38]. Interestingly, the type of AF or the duration of preoperative AF was not found to be associated with higher recurrence rates. Future improvement in surgical results will come with a better understanding of the mechanisms of the arrhythmia in a particular patient in order to allow for a more patient-tailored lesion set. Our group has had early success with ECG-imaging in detecting the electrophysiological substrate in patients referred for ablation. This report gives a benchmark for the success rate of a full maze lesion set and will provide a useful comparison for new and less invasive surgical approaches currently under development.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded in part from the National Institute of Health Grants 5RO1 HL032257, RO1 HL085113, and T32 HL07776.

Disclosure: Dr. Damiano is a consultant for AtriCure, Inc. and Medtronic, Inc and has received research grants from AtriCure, Inc., Medtronic, Inc., and Estech. Dr. Schuessler receives research support from AtriCure, Inc., Estech, and Cardialen and serves on the scientific advisory board of Cardialen. Ms. Bailey is a consultant for AtriCure, Inc.

Footnotes

This manuscript was presented at the Sixth International Symposium on Interventional Electrophysiology in the Management of Cardiac Arrhythmias, Newport, Rhode Island, September 24–26, 2010.

References

- 1.Thom T, Haase N, Rosamond W, Howard VJ, Rumsfeld J, Manolio T, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2006 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistic Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2006;113:e85–e151. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.171600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feinberg WM, Blackshear JL, Laupacis A, Kronmal R, Hart RG. Prevalence, age distribution, and gender of patients with atrial fibrillation: Analysis and implications. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1995;155:496–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: The Framingham study. Stroke. 1991;22:983–988. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.8.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcus GM, Sunf RJ. Antiarrhythmic agents in facilitating electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation and promoting maintenance of sinus rhythm. Cardiology. 2001;95:1–8. doi: 10.1159/000047335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerstenfeld EP, Guerra P, Sparks PB, Hattori K, Lesh MD. Clinical outcome after radiofrequency catheter ablation of focal atrial fibrillation triggers. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 2001;12:900–908. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oral H, Knight BP, Tada H, et al. Pulmonary vein isolation for paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2002;105:1077–1081. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox JL, Schuessler RB, D'Agostino HJ, Jr, Stone CM, Chang BC, Cain ME, et al. The surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. III. Development of a definitive surgical procedure. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 1991;101:569–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox JL, Schuessler RB, Lappas DG, Boineau JP. An 8 ½-year clinical experience with surgery for atrial fibrillation. Annals of Surgery. 1996;224:267–273. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199609000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prasad SM, Maniar HS, Camillo CJ, Schuessler RB, Boineau JP, Sundt TM, 3rd, et al. The Cox-Maze III procedure for atrial fibrillation: long-term efficacy in patients undergoing lone versus concomitant procedures. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2003;126:1822–1828. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(03)01287-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calkins H, Brugada J, Packer DL, et al. HRS/EHRA/ECAS expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: recommendations for personnel, policy, procedures and follow-up. A report of the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) task force on catheter on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:816–681. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viola N, Williams MR, Oz MC, Ad N. The technology in use for the surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Seminars in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2002;14:198–205. doi: 10.1053/stcs.2002.35292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khargi K, Hutten BA, Lemke B, Deneke T. Surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. European Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 2005;27:258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams MR, Garrido M, Oz MC, Argenziano M. Alternative energy sources for surgical atrial ablation. Journal of Cardiac Surgery. 2004;19:201–206. doi: 10.1111/j.0886-0440.2004.04037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cummings JE, Pacifico A, Drago JL, Kilicaslan F, Natale A. Alternative energy sources for the ablation of arrhythmias. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 2005;28:434–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2005.09481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prasad SM, Maniar HS, Schuessler RB, Damiano RJ., Jr Chronic transmural atrial ablation by using bipolar radiofrequency energy on the beating heart. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2002;124:708–713. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.125057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prasad SM, Maniar HS, Diodato MD, Schuessler RB, Damiano RJ., Jr Physiological consequences of bipolar radiofrequency on atria and pulmonary veins: a chronic animal study. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2003;76:836–841. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00716-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaynor SL, Ishii Y, Diodato MD, Prasad SM, Barnett KM, Damiano NR, et al. Successful performance of Cox-Maze procedure on beating heart using bipolar radiofrequency ablation: a feasible study in animals. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2004;78:1671–1677. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaynor SL, Diodato MD, Prasad SM, Ishii Y, Schuessler RB, Bailey MS, et al. A prospective single-center clinical trial of modified Cox maze procedure with bipolar radiofrequency ablation. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2004;128:535–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Damiano RJ, Jr, Gaynor SL, Bailey M, Prasad S, Cox JL, Boineau JP, et al. The long-term outcome of patients with coronary disease and atrial fibrillation undergoing the Cox maze procedure. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2003;126:2016–2021. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lall SC, Melby SJ, Voeller RK, Zierer A, Bailey MS, Guthrie TJ, et al. The effect of ablation technology on surgical outcome after the Cox-maze procedure: a propensity analysis. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2007;133:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melby SJ, Zierer A, Bailey MS, Cox JL, Lawton JS, Munfakh N, et al. A new era in the surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation: The impact of ablation technology and lesion set on procedural efficacy. Annals of Surgery. 2006;244(4):583–592. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000237654.00841.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee AM, Clark K, Bailey MS, Aziz A, Schuessler RB, Damiano RJ., Jr A minimally invasive Cox-maze procedure: operative technique and results. Innovations. 2010;5(4):281–286. doi: 10.1097/IMI.0b013e3181ee3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schaff HV, Dearani JA, Daly RC, Orszulak TA, Danielson GK. Cox-maze procedure for atrial fibrillation: Mayo clinic experience. Seminars in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2000;12:30–37. doi: 10.1016/s1043-0679(00)70014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Millar RC, Arcidi JM, Jr, Alison PJ. The maze III procedure for atrial fibrillation: should the indication be expanded? The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2000;70:1580–1586. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01707-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cox JL, Schuessler RB, Boineau JP. The surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. I. Summary of the current concepts of mechanisms of atrial flutter atrial fibrillation. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 1991;101:402–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cox JL, Canavan TE, Schuessler RB, Cain ME, Lindsay BD, Sone C, et al. The surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. II. Intraoperative electrophysiologic mapping and description of the electrophysiologic basis of atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation. Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 1991;101:406–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doll N, Borger MA, Fabricius A, Stephan S, et al. Esophageal perforation during left atrial radiofrequency ablation: is the risk too high? The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2003;125:836–842. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2003.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein GJ, Harrison L, Ideker RF, et al. Reaction of the myocardium to cryoenergy: electrophysiology and arrhythmogenic potential. Circulation. 1979;59:364–372. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.59.2.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gage AM, Montes M, Gage AA. Freezing the canine thoracic aorta in situ. The Journal of Surgical Research. 1979;27:331–340. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(79)90149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haïssaguerre M, Jaïs P, Shah DC, Takahashi A, Hocini M, Quiniou G, et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;339(10):659–666. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809033391003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheema A, Vasamreddy CR, Dalal D, Marine JE, Dong J, Henrikson CA, et al. Long-term single procedure efficacy of catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Journal of Interventional Cardiac Electrophysiology. 2006;15(3):145–155. doi: 10.1007/s10840-006-9005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lo LW, Tai CT, Lin YJ, Chang SL, Udyavar AR, Hu YF, et al. Predicting factors for atrial fibrillation acute termination during catheter ablation procedures: implications for catheter ablation strategy and long-term outcome. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6(3):311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han FT, Kasirajan V, Kowalski M, Kiser R, Wolfe L, Kalahasty G, et al. Results of a minimally invasive surgical pulmonary vein isolation and ganglionic plexi ablation for atrial fibrillation: single-center experience with 12-month follow-up. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2(4):370–377. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.854828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edgerton JR, Brinkman WT, Weaver T, Prince SL, Culica D, Herbert MA, et al. Pulmonary vein isolation and autonomic denervation for the management of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation by a minimally invasive approach. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2010;140(4):823–828. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mant J, Hobbs FDR, Fletcher K, et al. BAFTA Investigators, Midland Research Practices Network (MidReC) Warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in an elderly community population with atrial fibrillation (the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged Study, BAFTA): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:493–503. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61233-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finta B, Haines DE. Catheter ablation therapy for atrial fibrillation. Cardiology Clinics. 2004;22:127–145. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8651(03)00137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Voeller RK, Bailey MS, Zierer A, Lall SC, Sakamoto S, Aubuchon K, et al. Isolating the entire posterior left atrium improves surgical outcome after the Cox maze procedure. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2008;135(4):870–877. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Damiano RJ, Jr, Schwartz FH, Bailey MS, Maniar HS, Munfakh NA, Moon MR, et al. The Cox-maze IV procedure: predictors of late recurrence. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2011;141(1):113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.08.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]