Abstract

High-throughput ballistic injection nanorheology is a method for the quantitative study of cell mechanics. Cell mechanics are measured by ballistic injection of submicron particles into the cytoplasm of living cells and tracking the spontaneous displacement of the particles at high spatial resolution. The trajectories of the cytoplasm-embedded particles are transformed into mean-squared displacements, which are subsequently transformed into frequency-dependent viscoelastic moduli and time-dependent creep compliance of the cytoplasm. This method allows for the study of a wide range of cellular conditions, including cells inside a 3D matrix, cell subjected to shear flows and biochemical stimuli, and cells in a live animal. Ballistic injection lasts < 1 min and is followed by overnight incubation. Multiple particle tracking for one cell lasts < 1 min. Forty cells can be examined in < 1 h.

INTRODUCTION

Cells are continuously subjected to mechanical forces that regulate gene activation, protein expression profiles and associated cellular functions, including cell cycle, motility and differentiation. These forces are both externally applied by interstitial, hemodynamic and lymphatic flows or neighboring cells and internally induced through actomyosin-based contractility. The mechanical response of a cell to these mechanical forces is measured in terms of viscous and elastic moduli that reflect the ability of a cell to resist and relax these internally and externally applied mechanical stresses (see Box 1 for working definitions of rheological terms used in the Protocol). Methods that measure the viscoelastic moduli of live cells typically consist of applying a calibrated force or deformation onto the cell surface and measuring the extent of deformation or force induced onto the cell1–5. The majority of commercial instruments, including atomic force microscopes and indenters, are based on this simple principle. However, such instruments cannot readily be used to measure cellular viscoelastic moduli in vivo6, or to measure the viscoelatic moduli of cells in many important physiologically relevant conditions, including cells subjected to externally applied forces (e.g., forces generated by shear flow7), cells embedded inside 3D matrices8,9 or enclosed within an embryo6, as a direct contact between the instrument probe and the surface of the cell cannot occur. Moreover, both the surface area of contact and nonspecific interactions between the probe (e.g., the atomic force microscopy (AFM) cantilever) and the cell surface are not always well controlled. Finally, measurements of the mechanical properties of a single cell can last up to 30 min and these instruments do not measure frequency-dependent moduli. Together, these problems render the computation of cellular viscoelastic moduli either difficult or highly model dependent and make the use of these instruments unfeasible for high-throughput mechanical testing of large, clinically relevant number of cells10.

Box 1 | Definitions.

Particle-tracking microrheology is a method of probing the mechanical properties of a soft material and living cell whereby the spontaneous, thermally excited movements of individual submicron beads or organelles are monitored to extract the local viscoelastic properties of the material or cell. This method is sometimes called passive microrheology or one-point microrheology. When the bead is subjected to an externally applied electric or magnetic field, the method is called active microrheology. When the coordinated movements of multiple beads are analyzed simultaneously to extract the global viscoelastic properties of the material or cell, the method is called two-point microrheology.

Ballistic injection nanorheology is the method based on particle-tracking microrheology, whereby beads are ballistically injected into the cytoplasm of cells and subjected to particle-tracking analysis to rapidly measure the viscoelastic properties of living cells.

Mean-squared displacement (MSD) is the square of the distance between two points in space separated by a duration equal to a time lag τ. If x(t) and y(t) are the time-dependent coordinates of the centroid of a fluorescent bead, then the associated MSD of that bead is given by MSD(τ) = {x(t + τ) − x(t)}2 + {y(t + τ) − y(t)}2. A submicron bead suspended in a viscous liquid undergoes diffusive Brownian motion, and its MSD is proportional to τ and inversely proportional to both the bead radius and the viscosity of the liquid. For the same bead embedded in an elastic solid, the MSD is non-zero, but independent of time. When that bead is embedded in a viscoelastic material, then the MSD is time lag–dependent and has a slope between 0 and 1.

Frequency-dependent viscoelastic moduli are material properties that characterize the ability of the material to both flow (viscous modulus) and stretch (elastic modulus). Viscous and elastic moduli are the out-of-phase and in-phase components of the ratio of output mechanical stress induced in the material for sinusoidal input deformation applied to the material, respectively. Viscoelastic materials, such as the cytoplasm of a living cell, often display frequency-dependent moduli, whereby viscous and elastic moduli depend on the rate (i.e., frequency) at which the material is sheared. If the material is a viscous liquid, then the elastic modulus is zero and the viscous modulus is proportional to the liquid viscosity and rate of deformation. If the material is an elastic solid, then the viscous modulus is zero and the elastic modulus is a constant independent of frequency. Units of viscoelastic moduli are Pa or dyn cm−2 (1 Pa = 10 dyn cm−2).

Creep compliance is the material property that characterizes the ability of the material to deform. It is the mechanical deformation induced in a material by an externally applied mechanical shear stress. If the material is a viscous liquid, then the creep compliance increases linearly with time for a constantly applied shear stress and it is inversely proportional to the liquid viscosity. If the material is an elastic solid, then the creep compliance is independent of time and is inversely proportional to the elasticity of the material. Units of creep compliance are Pa−1 or (dyn cm−2)−1.

Savitzky-Golay filter is a type of filter based on a polynomial regression on a series of known values to determine the smoothed value for each point. This filter preserves the relative maxima, minima and width of the distribution. It is used here to smooth time-dependent MSD of beads suspended in a cytoplasm.

Stokes-Einstein equation is the relationship between the diffusion coefficient of a submicron spherical object (here a bead), D, and the friction coefficient of that object, ξ: D = kBT / ξ, where kBT is the thermal energy. For a spherical bead in a viscous liquid, ξ = 6 π η a, where a is the bead radius and η is the viscosity of the liquid. The generalized Stokes-Einstein equation extends this classical Stokes-Einstein equation to the case of a viscoelastic material for which the friction coefficient is not a constant but depends on history.

The advent of particle-tracking microrheology11 has opened the possibility to rapidly measure viscoelastic moduli of cells in these more physiologically relevant conditions12. Particle-tracking microrheology has been used to assess the mechanical properties of a wide range of soft materials and cells subjected to a wide range of biochemical and mechanical stimuli13–36. Earlier versions of particle-tracking microrheology consisted of injecting submicron beads into the cytoplasm of live cells and monitoring, after over-night incubation, the spontaneous Brownian displacements of these beads37–41. Beads are injected directly into the cytoplasm, because it is necessary to circumvent the endocytic pathway. If the beads are passively engulfed by the cell by endocytosis, they become trapped in vesicles that are connected to cytoskeletal structures via motor proteins, and this would artificially enhance the movements of the beads. Mathematical transformation of the mean-squared displacements (MSDs) of the beads yields the local, frequency-dependent viscoelastic moduli and time-dependent creep compliance of the cytoplasm12,42 (Box 1).

A limitation of this approach is that manual injection of beads is tedious and causes trauma to the cells, which may influence the measurements. The introduction of ballistic injection greatly reduces mechanical trauma to the cells and greatly increases the number of cells amenable to measurement7,8,43–45. Although manual injection may kill up to 50% of the cells, only background levels of cell death are observed during ballistic injection (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Minimal cell death is induced by ballistic injection of nanoparticles into the cytoplasm of adherent cells. (a–j) As a way of assessing whether ballistic injection induced cell death, we used fluorescence microscopy to measure both cell densities after 6 h of plating time (starting from the same plating density) (a) and the fractions of dead cells before ballistic injection (b–d) and after ballistic injection (e–g). We found that ballistic injection changed neither cell density (a) nor the extent of cell death compared with control cells that were not subjected to injection (b–g). In panel a, bars are the numbers of cells per unit area before ballistic injection and after ballistic injection for two independent trials (n = 2). (h–j) As a positive control, we found that the fraction of dead cells subjected to the nonionic surfactant Triton X-100 was effectively 100% (i,j). Nuclear DNA was stained using H33342 (blue in panels b,e and h); cell death was assessed using propidium iodide (red in panels c,f and i). Propidium iodide signal is only colocalized with nuclear DNA within the nucleus of dead cells. Scale bar, 100 µm. BI, ballistic injection.

Here we describe the detailed protocol of a method—high-throughput ballistic injection nanorheology (htBIN)—to inject nanoparticles in the cytoplasm of adherent cells, to track the movements of multiple beads embedded in a living cell at sub-pixel resolution and to transform the resulting trajectories into local viscoelastic moduli of the cytoplasm of living cells. To illustrate the protocol, htBIN is applied to human ovarian cancer cells.

htBIN makes use of submicron nanoparticles (typically 100-to 300-nm diameter) that are fluorescent and carboxylated. We have found that carboxylated beads work better than amine-modified beads, which tend to be actively transported in the cytoplasm of living cells37. As a control, we have previously shown that the measurements of viscoelastic moduli of DNA and actin filament gels by conventional rheometry and particle-tracking microrheology are similar when using carboxylated beads11,42,46,47.

htBIN measurements are highly reproducible. In our lab, the viscoelastic moduli of mouse embryonic fibroblasts have been measured by different investigators, in different facilities, using different fluorescence microscopes and different suppliers of fluorescent beads. Over the years, these measurements have proved to be highly consistent: the elasticity of mouse embryonic fibroblasts was found to have the same value within 20%, which is the level of reproducibility obtained when measuring the elasticity of polymer solutions using conventional rheometers.

Recent studies have raised questions regarding the fluctuation-dissipation theorem used to derive the equation in Step 49 below. It has been suggested that it may only be an approximation for determining the viscoelastic moduli of living cells, as the movements of beads could be driven not only by thermal fluctuations, but also by motor proteins48. We have addressed this in a recent paper by Hale et al.5. Here we investigated whether fluctuations of beads in the cytoplasm of live cells were driven predominantly by thermal energy (as presumed in the formula in Step 48), or by distributed motor proteins generating active forces. We showed—using the same correlation analysis as in the paper by Mizuno et al.48—that when beads are properly embedded in the cytoplasm of the cell as achieved using ballistic injection, the beads undergo strictly thermally excited, non-myosin-driven, fluctuations5. Indeed, treatment of cells with myosin inhibitors, even at concentrations sufficient to dissolve stress fibers and focal adhesions, showed no effect on the two-point correlations among beads and on the values of MSDs themselves. In contrast and as expected, F-actin depolymerization caused an increase in measured MSD, corresponding to a decrease in cytoplasmic elasticity. There is no measurable effect of myosin inhibition because myosin II is not distributed uniformly in the cytoplasm, as in the in vitro actin networks containing purified actin and myosin and considered in reference 48. In adherent cells, myosin II is localized in the cortex and in the basal and dorsal stress fibers, the very regions from which beads are excluded. Several papers have also attempted to use the spontaneous motion of either endogenous organelles or passively engulfed nanoparticles to measure the viscoelastic properties of cells. In these cases, the motion of organelles and engulfed beads includes both thermal and myosin-driven fluctuations49–51. In contrast, htBIN, for which beads are injected into the cytoplasm, probes the rheology of the actin-rich but largely myosin II–devoid cytoplasm. Finally, Hale et al.5 explained with a simple mechanical model why AFM and AFM-like measurements, which mostly probe cortical actomyosin structures, measure very high elastic moduli (kPa instead of tens of Pa) and are highly sensitive to myosin inhibition, in contrast to the htBIN measurements described in this protocol5.

htBIN has already been used in a wide range of applications listed in Table 1 (see also Boxes 2 and 3 for how to perform cell microrheology in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos and cells impregnated in a 3D collagen matrix, respectively). Moreover, htBIN offers multiple crucial advantages over conventional approaches such as AFM and micropipette suction (Table 2).

Table 1.

Live-cell applications of htBIN.

| Applications | References |

|---|---|

| Mechanical response to biochemical stimulation | 8,9,39 |

| Mechanical response of cells to shear flow | 7 |

| Mechanical response of cells to physical cues | 34 |

| Mechanical response of cells during differentiation | 6,63 |

| Mechanical response of cells to cytoskeleton-disrupting drugs (latrunculin, nocadozole, taxol and so on) | 37,39,40,44,45 |

| Mechanical response of cells following injection of purified proteins | 41,43 |

| The mechanical properties of cancer cells | Present study |

| The mechanical properties of diseased cells (muscular dystrophy, progeria and so on) | 45,64 |

| The mechanical properties of a living embryo in vivo | 6 and Box 2 |

| The anisotropic mechanical properties of migrating cells | 38,40,41 |

| Probing the mechanical connections between cytoskeleton and nucleus | 45,64,65 |

| The mechanical properties of the interphase nucleus in living cells | 66 |

| Mechanical response of cells to Rho-GTPase and myosin activation | 5,7,39 |

| The mechanical properties of cells embedded inside a 3D matrix | 8,9,67 and Box 3 |

Box 2 | Cell microrheology in vivo—the case of C. elegans embryos.

We have extended the use of particle-tracking microrheology to living cells in vivo6. Below we briefly describe the application of particle-tracking microrheology to the case of a developing embryo of the nematode C. elegans.

Incorporation of beads in C. elegans

A colloidal suspension of fluorescent polystyrene nanoparticles is dialyzed against ddH2O overnight at room temperature. The nanoparticles are surface modified with the hydrophilic polymer polyethylene glycol (PEG) to ensure that the nanoparticles do not interact directly with subcellular structures. Microneedles (World Precision Instruments) pulled on a vertical micropipette puller (Sutter Instruments)68 are filled by capillary action with the nanoparticle suspension. The needles are mounted on a microinjector controlled by a micromanipulator (Eppendorf 5170) on a Zeiss Axiovert 10 inverted microscope (Zeiss). The nanoparticles are microinjected into the syncytial gonads of gravid hermaphrodites according to the protocol developed for transformation69. After injection, worms are immersed in the recovery buffer (20% (wt/vol) glucose, 1 M KCl, 5 M NaCl, 1 M MgCl2, 1 M CaCl2, 1 M HEPES pH 7.2 in H2O) for at least 15 min and then transferred to M9 buffer (22 mM KH2PO4, 42 mM Na2HPO4, 85 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgSO4 in H2O) for at least 1 h before being incubated at 25 °C for ~4 h before image acquisition.

Preparation of PEG-coated nanoparticles

To probe the micromechanical properties of live embryos, we need to use PEG-coated (PEGylated) 100-nm-diameter nanoparticles, which are prepared as described70. Briefly, 5 mg ml−1 amine-terminated PEG (diamino-PEG, average MW 3400; Shearwater Polymers) in 50 mM MES (pH = 6.0) is mixed at 1:1 ratio with 2% (wt/vol) aqueous suspension of carboxylate-modified polystyrene nanoparticles (Molecular Probes) and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Then 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide is added to a final concentration of 4 mg ml−1 and the pH is adjusted to 6.5. The resulting solution is incubated overnight. Glycine (100 mM) is added to quench the reaction, and the mixture is incubated for 30 min at room temperature. PEGylated nanoparticles are obtained by centrifugation (3,300g for 15 min at 25 °C) and washed three times with PBS.

Light microscopy

Young C. elegans eggs are obtained by cutting gravid hermaphrodite worms in egg salts (118 mM NaCl, 121 mM KCl in H2O) with the help of a dissecting microscope and transferred to 3% (wt/vol) agarose pads (Invitrogen) sealed by capillary action underneath coverslips (VWR). Eggs can be viewed by differential interference contrast (DIC) optics using a Nikon TE300 epifluorescence microscope with a ×60 DIC oil-immersion lens (numerical aperture = 1.4, Nikon) and an Orca II charge-coupled device camera (Hamamatsu). All image collection is performed at 25 °C.

Particle tracking and computation of viscoelastic moduli from MSDs

The process is identical to that described in PROCEDURE Steps 32–50.

Box 3 | htBIN of cells fully embedded in a 3D matrix.

We have extended the use of htBIN to the more physiological case of cells embedded inside a 3D matrix8,9,67. The only substantial difference with the more conventional case of cells on 2D substrates described in the main text is the incorporation of cells within a 3D matrix. This 3D matrix is either composed of purified extracellular matrix component (e.g., collagen I)67, peptides8 or cell-derived matrix9.

Incorporation of cells inside a 3D collagen I matrix

Cell-impregnated 3D collagen matrices are prepared by mixing cells suspended in culture medium and 10× reconstitution buffer, 1:1 (vol/vol), with soluble rat tail type I collagen in acetic acid (BD Biosciences) to achieve a chosen final concentration of (typically between 1 and 6 mg ml−1) collagen71,72). NaOH of 1 M is then added to normalize pH (pH 7.0, 15–30 µl 1 M NaOH), and the mixture is placed in multiwell, coverslip-bottom culture plates (LabTek). All ingredients are kept chilled to avoid premature collagen gelation, with care taken during mixing to avoid the introduction of bubbles into the collagen solution. Collagen gels are allowed to solidify overnight in an incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2, and then 500 µl of cell culture medium is added on top of the gels before use in experiments. Cell density is kept low so as to ensure that htBIN measurements are accurate.

Table 2.

Advantages and limitations of htBIN.

| Advantages | Comparison | References |

|---|---|---|

| htBIN measures local (as opposed to global) rheological properties | AFM can probe local properties; micropipette suction on measures global properties | 37,40,41 |

| htBIN can measure cell mechanics in vivo | No other technique has been shown to probe cell mechanics in vivo | 6 |

| htBIN measurements are extremely rapid and high-throughout | One cell measured in <1 min; AFM requires ~30 min per cell | Present study |

| htBIN can measure the mechanics of cells fully embedded inside a 3D matrix | No other technique has been shown to probe the mechanics of cells in matrix | 8,9,67 |

| htBIN can measure nuclear mechanics in situ | AFM measurements cannot isolate the contributions of plasma membrane, cytoskeleton and nuclear to cell mechanics; micropipette suction requires disassembly of the actin network | 66 |

| htBIN allows real-time measurements of the mechanics of cells under mechanical force | AFM cannot probe the mechanics of cells under mechanical force (e.g., flow) | 7 |

| htBIN allows us to probe the viscoelastic properties of cells as a function of rate of deformation in < 30 s | AFM and micropipette suction do not allow currently for the measurements of frequency-dependent viscoelastic moduli | 7 |

| htBIN can measure the intrinsic mechanical heterogeneity within a single cell | 7 | |

| Limitations | ||

| Optimization of the injection of nanoparticles in cells can be time consuming | Present study | |

| Requires a high-end, mechanically stable fluorescence microscope | Present study |

MATERIALS

REAGENTS

Normal human ovarian epithelial cells (OSE10) and ovarian cancer cells (OVCAR3) (provided by I.-M. Shih) ! CAUTION Adhere to all relevant ethics guidelines when working with human tissues.

RPMI 1640 medium (Cellgro, cat. no. 10-040-cv)

Fetal bovine serum (ATCC, cat. no. 30-2030)

Penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma, cat. no. P0781)

Hank’s buffered salt solution (HBSS, Gibco, cat. no. 14170)

Trypsin-EDTA solution (0.25% (wt/vol), Sigma, cat. no. T4049)

Ethanol (100%, Pharmco-Aaper, cat. no. 111000200)

Isopropanol (J.T. Baker, cat. no. 9084-03)

Hoechst 33342 (Sigma, cat. no. B2261)

Propidium iodide (Invitrogen, cat. no. P1304MP)

He gas (compressed, ultra high purity; Airgas, cat. no. UN1046)

Polystyrene carboxylated 580/605 fluorescent particles (0.1-µm diameter) suspension (2% solids; Invitrogen, cat. no. F8801)

Polystyrene carboxylated 580/605 fluorescent particles (0.2-µm diameter) suspension (2% solids; Invitrogen, cat. no. F8810)

Polystyrene carboxylated 580/605 fluorescent particles (1.0-µm diameter) suspension, 2% solids (Invitrogen, cat. no. F8821)

Cellulose ester dialysis membrane (300 kDa, Spectrum Labs, cat. no. 131450)

Parafilm (Pechiney)

EQUIPMENT

Laminar flow hood

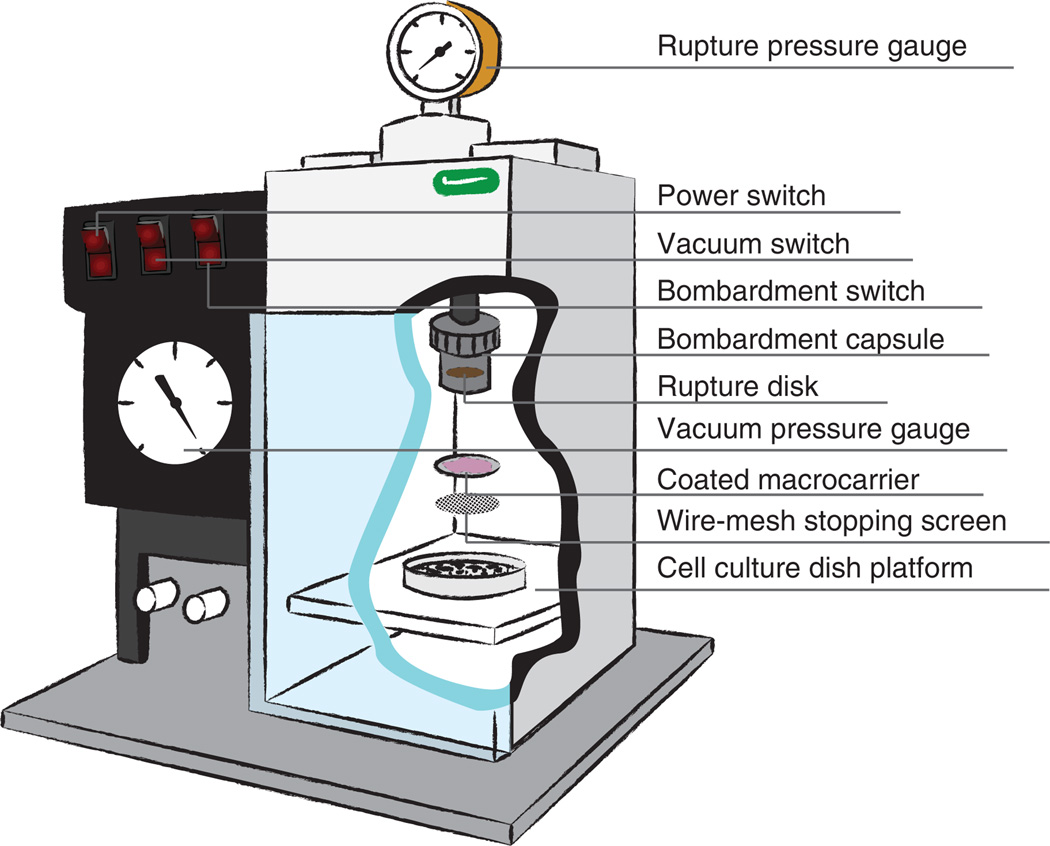

PDS-1000/He biolistic particle delivery system (Bio-Rad, cat. no. 165-2257; Fig. 2)

Hepta adaptor for PDS-1000/He system (Bio-Rad, cat. no. 165-2225)

Dry vacuum pump (Welch, cat. no. 2681B-60)

Inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon, cat. no. TE2000)

Fluorescent illumination (EXFO X-cite 120)

EMCCD camera (Andor LucaR)

Image acquisition software (Nikon Elements, Nikon)

Image analysis software (MATLAB, MathWorks)

LiveCell heat and CO2 regulation chamber (Pathology Devices, cat. no. LC20103)

Benchtop light microscope (Nikon TS100, Nikon)

Humidified incubator (Thermo Scientific, cat. no. 3110)

Benchtop centrifuge (Thermo Scientific, cat. no. IEC-CL10)

Rupture disks (450/650/900/1,100/1,350/1,550/1,800/2,000/2,200 p.s.i. (Bio-Rad, cat. no. 165-23xx)

Macrocarriers (Bio-Rad, cat. no. 165-2335; Fig. 2)

Stopping screens (Bio-Rad, cat. no. 165-2336; Fig. 2)

Hepta stopping screens (Bio-Rad, cat. no. 165-2226)

Protective eyewear

Dialysis equipment: bag, membrane and tubing

Membrane closure clips (23-mm width; Spectrum Labs, cat. no. 132735)

Vortex (Fisher, cat. no. 12-812)

Magnetic stir plate (IKA Works Color Squid, IKA)

Magnetic stir bars

Beaker (4 liter; Pyrex, cat. no. 1003)

Microcentrifuge tubes (1.5 ml; Denville, cat. no. C-2170)

Conical tubes (15 ml; Falcon, cat. no. 352097)

Conical tubes (50 ml; Falcon, cat. no. 352098)

CA sterilizing, low-protein-binding filter system (0.22-µm; Corning, cat. no. 430769)

Cell culture dish (100 mm × 20 mm; Corning, cat. no. 430167)

Cell culture dish (35 mm × 10 mm; Corning, cat. no. 430165)

Glass bottom dish (35 mm, collagen coated; MatTek, cat. no. P35GCOL-0-14-C)

Glass bottom dish (35 mm, uncoated; MatTek, cat. no. P35G-0-14-C)

Kimwipes (Kimberly-Clark, cat. no. 34256)

Tweezers

Razor blade

Styrofoam float

Rubber band

Biolistic torque wrench (Bio-Rad)

Figure 2.

Biolistic machine used to introduce submicron particles inside cells for high-throughout ballistic nanorheology (htBIN) analysis. A high concentration of nanoparticles is placed on the microcarrier. A pressure drop is applied and nanoparticles are pushed through a wire mesh stopping screen. Use of this machine is described in detail in the text.

REAGENT SETUP

Cell culture preparation

Normal ovarian epithelial cells (OSE10) (OVCAR3) are cultured in filtered RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum, 100 U of penicillin and 100 µg of streptomycin and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified, 5% CO2 environment. Cells are passaged every 3–4 d and are seeded at approximately 1 × 104 cells per ml on either 35- or 100-mm cell culture dishes, depending on the number of cells required for experimentation. Cell culture dishes are ready for bombardment when cells reach 80–90% confluence.

Isopropanol preparation

Pipette 50 ml of isopropanol into a 50-ml conical tube; this will facilitate the use of isopropanol during loading of the particle delivery system.

EQUIPMENT SETUP

PDS-1000/He particle delivery system

The PDS-1000/He system allows for variable control of rupture pressure, particle penetration acceleration and particle dispersion. The rupture pressure, which dictates the force imparted to particles by a controlled burst of helium, ranges from 450 to 2,200 p.s.i., and is set by the rating of the rupture disc that is placed in the bombardment capsule (Fig. 2; see Step 13). Different pressures are recommended according to cell type and whether a single- or hepta-macrocarrier adapted is used (see High spatiotemporal resolution with video microscopy in EQUIPMENT SETUP). The acceleration for particle penetration into the cells can be controlled both by the pressure rating of the rupture disk and the physical distance between the bombardment capsule and the macrocarrier adaptor (Fig. 2). It is recommended that the distance between the bombardment capsule and the macrocarrier adaptor be minimized in order to maximize penetration efficiency (Fig. 2); note that this distance can be increased if penetration causes marked cell damage and significant cell detachment.

High spatiotemporal resolution with video microscopy

An inverted microscope with fluorescent light source incorporated with an oil-immersion lens with high magnification (×60) and high numerical aperture (1.4) are used to achieve the high spatial resolution for visualization of fluorescent particles with submicron size. A high-sensitivity CCD camera featured with frame-transfer mode and pixel binning enables a fast acquisition rate and high sensitivity under low-light conditions. Video acquisition speed is set to ~30 frames per second (f.p.s.). To avoid the dynamic error, the exposure time should be at least five times lower than the desired temporal resolution. For example, to reach a 30-Hz frame rate, the exposure time should be less than 6 ms. Reduction of image size using regions of interest and changing the settings of the pixel-binning features can help achieve this high frame rate. Pixel binning is recommended particularly for tracking particles smaller than 200 nm, as it improves tracking resolution by increasing the resolution of the intensity measurements by increasing the pixel size as shown in reference 52. Our typical tracking settings are 6-ms exposure time, 2 × 2 binning and total sensing area of 350 × 350 pixels. The pixel size under such settings is 260 nm using a ×60 objective.

Live/dead cell assessment by light microscopy

Live cells were incubated with Hoechst 33342 (1 µg ml− 1) and propidium iodide (2 µg ml− 1) for 10 min before microscopy. Hoechst 33342 binds to nuclear DNA and emits fluorescence for both living and dead cells; propidium iodide signal is only colocalized with nuclear DNA within the nucleus of dead cells. Here we used a fluorescence light microscope equipped with a low magnification (×10) objective and excitation filters of 340–380 and 528–554 nm to detect and quantify live and dead cells (Table 3). This control to determine the ratio of live to dead cells is conducted separately from live-cell htBIN measurements (i.e., it is not conducted on the same cells, because this live/dead assessment requires cells to be fixed).

Table 3.

Cell line–specific bombardment conditions.

| Cell line | Bombardment conditions | Other notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts | 900 p.s.i. for single-macrocarrier adapter; 2,000 p.s.i. for hepta-macrocarrier adapter | 1–4 | |

| Mouse embryonic/adult fibroblasts | 900 p.s.i. for single-macrocarrier adapter; 2,000 p.s.i. for hepta-macrocarrier adapter | 5,6 | |

| Normal human breast epithelial cells (MCF-10A) | 900 p.s.i. for single-macrocarrier adapter | C.M.H., unpublished data | |

| Human breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) | 900 p.s.i. for single-macrocarrier adapter | Weak substrate adhesion following bombardment | C.M.H., unpublished data |

| Normal ovarian epithelial cells (OSE10) | 1,800 p.s.i. for hepta-macrocarrier adapter | Present study | |

| Ovarian cancer cells (OVCAR3) | 1,800 p.s.i. for hepta-macrocarrier adapter | Present study | |

| Human lung fibroblasts (IMR90) | 900 p.s.i. for single-macrocarrier adapter | 63 | |

| Primary cells | |||

| Human induced pluripotent stem cells | 900 p.s.i. for single-macrocarrier adapter | 63 | |

| Human embryonic stem cells | 900 p.s.i. for single-macrocarrier adapter | 63 | |

| Human umbilical vein endothelial cells | 900 p.s.i. for single-macrocarrier adapter; 2,000 p.s.i. for hepta-macrocarrier adapter | 8 |

Software

All particle-tracking analysis processes are implemented in software that was custom developed in MATLAB (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Image processing steps taken to enhance the high-resolution tracking of fluorescent nanoparticles in the cytoplasm of live cells. Steps 33–50 are detailed in the text. a.u., arbitrary units.

PROCEDURE

Dialyze particles against ethanol to replace stock solvent ● TIMING 24 h

-

1|

Cut an 8-cm-long strip of dialysis membrane using a fresh razor blade. Seal the bottom of the membrane with a membrane closure clip. Rub the top of the membrane between the thumb and forefinger to open the tubing.

-

2|

Vortex fluorescent particles in the stock container for 30 s to ensure that the solution is homogeneous. Pipette 1.5 ml of particles (either 0.1-, 0.2- or 1.0-µm diameter) into dialysis tubing. Seal the top of the membrane with another membrane closure clip.

-

3|

Using a rubber band, attach a styrofoam float to the top of the membrane clip. Place the dialysis bag loaded with particles in a 4-liter beaker filled with 3 liters of 100% ethanol. Insert a magnetic stir bar into the 4-liter beaker and place on a magnetic stir plate.

-

4|

Stir for 24 h at 4 °C to replace the supplied water solvent with ethanol.

-

5|

After 24 h, remove the dialysis bag from the beaker, remove the top membrane closure clip and pipette the contents of the dialysis bag into a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube. Seal the tube with Parafilm, cover in foil and store at 4 °C. These polystyrene particles are stable in ethanol for more than a month.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

Coat macrocarriers with fluorescent particles ● TIMING 40 min

-

6|

In a laminar flow hood, using tweezers, place individual macrocarriers in a 100 mm × 20 mm cell culture dish. For this type of dish, coat seven macrocarriers per dish. If you are bombarding 35-mm dishes of cells, coat one macrocarrier per dish.

-

7|

Briefly vortex the particle solution in ethanol to ensure homogeneity. Using a 200-µl pipette tip, thoroughly mix the solution by pipetting up and down. Pipette 15 µl of particles (regardless of particle diameter) directly onto each macrocarrier. By using a pipette tip, spread the solution as evenly as possible across the surface of the macrocarrier. Mix the solution by pipetting up and down before coating each macrocarrier.

-

8|

Allow 5 min for particles to dry on macrocarrier. Pipette another 15 µl of particles on each macrocarrier. Cover the dish(es) of macrocarriers in foil and store them at room temperature. Coated macrocarriers can be used 30 min after the final coating, or they can be stored for up to 1 week if maintained at room temperature (25 °C) in the dark.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

Load the biolistic delivery system for particle bombardment ● TIMING 20 min

-

9|

Use ethanol and Kimwipes to clean all of the removable parts inside the bombardment chamber (Fig. 2), including the cell culture dish platform. If you are bombarding a 35-mm dish of cells, set the hepta-macrocarrier accessories aside and clean all of the single-macrocarrier accessories. If you are bombarding a 100-mm dish of cells, set the single-macrocarrier accessories aside and clean all of the hepta-macrocarrier accessories.

-

10|

Load the single- or hepta-macrocarrier assembly (Fig. 2) by placing a coated macrocarrier into the metal well using tweezers.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Ensure that the macrocarrier is placed into the assembly with the coating of particles facing up. This assembly will later be flipped when placed into the bombardment chamber so that the particles will face the cells subsequently placed below the assembly in the chamber.

-

11|

Using the provided red plastic Caplug stopper, ensure that the coated macrocarrier is sitting flat in the assembly by inserting the stopper in the metal well and turning it back and forth. To verify that the macrocarrier is flat, hold the assembly up to the light and check for an even reflection on the underside of the macrocarrier.

-

12|

Clean the stopping screen (either single or hepta; Fig. 2) using ethanol and allow it to air-dry for 5 min. Place a clean stopping screen in the macrocarrier assembly.

If you are using a single stopping screen, place the screen at the bottom of the macrocarrier assembly and then place the metal well containing the coated macrocarrier facedown such that the particles are now facing the metal stopping screen. Screw on the macrocarrier assembly cap. If you are using a hepta stopping screen, align the screen’s two holes with the small posts on the macrocarrier assembly. Ensure that the particles are facing the stopping screen. Flip the macrocarrier assembly and stopping screen and place into the macrocarrier assembly platform by aligning the metal notches. Set aside the macrocarrier platform.

-

13|

Use tweezers to grab a rupture disk (choose the pressure rating accordingly; see EQUIPMENT SETUP). Submerge the rupture disk in a conical tube of isopropanol for 3 s. Ensure that rupture disk is fully wetted to provide an adequate seal. Place the rupture disk inside either the single- or hepta-bombardment capsule.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Ensure that only a single rupture disk is placed in the bombardment capsule; the disks are very thin and tend to stick together, and thus multiple disks can easily be confused for a single disk. If multiple disks are placed into the bombardment capsule, rupture will not occur at the target pressure. Also ensure that the rupture disk lies flat inside the bombardment capsule; if the disk lies at an angle, the integrity of the vacuum that will be created in a subsequent step will be compromised.

-

14|

Screw the bombardment capsule into the threads atop the bombardment chamber (Fig. 2). Tighten the bombardment chamber using the provided Bio-Rad biolistic torque wrench by inserting the short end of the wrench into a hole on the bombardment chamber.

-

15|

Insert the macrocarrier assembly platform into the bombardment chamber in the slot immediately below the bombardment capsule, and then insert the cell culture dish platform in the slot below the bombardment capsule. Note that in addition to using a rupture disk with a lower pressure rating, the distance between the bombardment capsule and the macrocarrier assembly platform can be increased in order to reduce the acceleration of particles, if necessary. Furthermore, the distance between the macrocarrier assembly platform and the cell culture dish platform can be increased to allow for greater dispersion of particles, albeit at a reduced penetration acceleration.

▲ CRITICAL STEP If you are using the hepta adaptor, ensure that the seven helium channels on the bombardment capsule are aligned with the holes in the macrocarrier assembly platform for optimal bombardment efficiency. The macrocarrier assembly holes can be aligned using the short metal rod attached to the macrocarrier assembly.

-

16|

Close the bombardment chamber door.

Transfer of particles into cells via bombardment ● TIMING 10 min

-

17|

Flip the leftmost switch on the PDS-1000/He to turn the device on.

-

18|

Open the helium tank. Ensure that the tank is regulated to a pressure that exceeds the pressure of the rupture disk being used (Table 3).

-

19|

Remove the prepared dish of cells (ideally 90% confluent) from the incubator, and aspirate medium in a laminar flow hood.

-

20|

Open the bombardment chamber door. Insert the dish of cells, with the top of the dish removed, on the cell culture dish platform. Push the platform into the chamber.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Ensure that the dish is positioned immediately below the macrocarriers above, especially if you are using a 35-mm dish.

-

21|

Close the bombardment chamber door. Lock the door tightly using the black tab at right.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Ensure that the black tab is fully lowered and tightened. If the door is not fully locked, this can prevent formation of a vacuum and may also cause the door to swing open during bombardment.

-

22|

Turn on the dry vacuum pump. Flip the middle switch on the PDS-1000/He to the top ‘VAC’ position. Pull a vacuum until the needle on the vacuum gauge reaches 28 in Hg. Flip the middle switch to the bottom ‘HOLD’ position (Fig. 2). Turn off the dry vacuum pump.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

23|

Hold the right ‘FIRE’ switch on the PDS-1000/He in the top position (Fig. 2). This will fill the chamber above the rupture disk with helium. Monitor the pressure buildup on the golden pressure gauge above the bombardment chamber. When the pressure reaches the pressure rating of the chosen rupture disk (±100 p.s.i.), you will hear a loud ‘pop’, indicating that the disk has ruptured and that the burst of helium has accelerated the particles into the target cells. Release the ‘FIRE’ switch after the disk has ruptured and move the middle vacuum switch to the ‘VENT’ position to release the vacuum.

! CAUTION Wear safety glasses when operating the PDS-1000/He because of the potentially dangerous conditions associated with the high-pressure helium and high-speed particles used during bombardment.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

24|

When the needle on the vacuum gauge reaches 0 in Hg, the vacuum has been released. Open the door of the bombardment chamber, quickly place the lid back on the dish, view the dish under a benchtop light microscope to assess cell presence and survival, and then transfer the dish to a laminar flow hood for post-bombardment cell washing.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

25|

Gently pipette HBSS heated to 37 °C in the bombarded cell culture dish. For 35-mm dishes, use 3 ml of HBSS per wash. For 100-mm dishes, use 10 ml of HBSS per wash.

Lightly swirl and aspirate the media to remove excess particles that did not pass into the cytoplasm of the target cells. Repeat washing two times. After the last aspiration, pipette 10 ml of warm growth medium in the dish.

▲ CRITICAL STEP This step substantially reduces the number of particles that enter the cell via the endocytic pathway. Endocytosed particles will show directed motion inside the cell and their trajectories will not reflect the mechanical properties of the cytoplasm, but rather the dynamics of intracellular vesicle trafficking.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

26|

View cells under a benchtop light microscope to ensure the presence of cells in the cell culture dish. Return cells to the incubator and allow cells to recover for at least 4 h. In particular, verify that ballistic injection did not cause extensive cell death. Some cell death may occur; however, pressure drops can be adjusted to reduce cell death down to background levels (Fig. 1 and Table 3).

? TROUBLESHOOTING

Replate cells for microscopy ● TIMING 23 h

-

27|

Following the 4-h recovery incubation, wash cells again with HBSS heated to 37 °C in laminar flow hood. Detach bombarded cells with 0.25% (wt/vol) trypsin-EDTA solution heated to 37 °C and incubate at 37 °C for 10 min. For 35-mm dishes, use 0.5 ml of trypsin-EDTA solution. For 100-mm dishes, use 1 ml of trypsin-EDTA solution.

-

28|

After 10 min, visualize cells on a benchtop light microscope and ensure that cells have detached. Dilute cells in growth medium, collect and pipette into a 15-ml conical tube. For 35-mm dishes, dilute to a total volume of 3 ml. For 100-mm dishes, dilute to a total volume of 10 ml.

-

29|

Spin down cells in a benchtop centrifuge at 900–2,000 r.p.m., corresponding to 100–300g, depending on the cell type, for 5 min at room temperature.

-

30|

Aspirate the supernatant and resuspend the cells in growth culture medium. Plate cells at approximately 2 × 103 cells per ml on glass- or collagen-coated (depending on the cell type) 35-mm glass-bottom dishes for high-resolution microscopy.

-

31|

Incubate cells for at least 18 h before performing particle-tracking experiments.

Track particles in living cells at high spatiotemporal resolution with video microscopy ● TIMING 2 h

-

32|

Place the glass-bottom dish on the microscope and locate cells that contain fluorescent beads. Cells typically contain between 5 and 30 beads per cell. Use the video acquisition speed of ~30 f.p.s. to obtain the ~20 s video of fluorescent particles inside living cell. Acquire a phase-contrast image of the cell in the same field so as to be able to subsequently superimpose the trajectories of the nanoparticles and the contour of the cell.

▲ CRITICAL STEP If large aggregates of nanoparticles are present in the cell, vortexing of nanoparticles (Step 2) needs to be lengthened and Steps 1–32 need to be repeated.

Particle identification, analysis and extraction of viscoelastic properties ● TIMING 2 h

-

33|

Using the software described in Figure 1, estimate the local background intensity, IB, in the raw particle image, I. Filter the image, I, using a 2D averaging filter with a window size two times larger than the apparent radius of the nanoparticle (Fig. 3). The image background is mainly composed of two components: the intensity offset value from the camera and autofluorescence from molecules in the medium.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

34|

Convolve the original image with a spatial Gaussian smoothing filter, which has the same size as the used averaging filter, and obtain the convolved image IC (ref. 53; Fig. 3). The s.d. used in the Gaussian filter should be equivalent to and the size of the filter is the same as the averaging filter defined earlier. Image convolution will reduce the noise in the original image and improve the resolution in nanoparticle positioning53,54.

-

35|

Obtain the reduced-noise, no-background image, IN, by subtracting IB from IC (Fig. 3).

-

36|

Estimate the position of a particle at subpixel resolution by applying logarithm-weighted Gaussian fit on a 3 × 3–pixel region of a particle image (Fig. 3). Expanding the Gaussian equation in Logarithm scale gives rise to the linear regression fitting and, as a result, enhances computing efficiency.

-

37|

Identify the same particle in the next frame by finding which particle has the smallest distance to current location at the next frame and run through all time frame to compose the trajectory of a nanoparticle.

-

38|

Measure the signal-noise response of the camera intensity readout (for MSD calibration). Control the halogen bulb power to set different photon fluxes to the CCD by changing the power of the light source. In this analysis, the focusing step is not important, as it is about measuring the noise level at different levels of intensity sensed in the camera as long as the focusing does not cause any inhomogeneous illumination. However, focusing will increase the amount of photon entering the camera for a given power output in the halogen bulb.

-

39|

Take two sequential images for each set of photon flux conditions, ranging from no-light conditions to maximum detection limit (the intensity at which the intensity is completely saturated) using exposure time shorter than 30 ms (or the minimum time lag used for tracking the nanoparticles).

-

40|

Measure the mean intensity readout signal, S, at each photon flux condition by evaluating the mean intensity value from the two images. For the same conditions, measure the intensity readout noise magnitude, N, which is equal to half of the intensity variance estimated from the intensity distribution after subtracting one image from the other.

-

41|

Obtain the signal-noise response curve S-N by fitting the S-N data set using the first-order polynomial model55 (Fig. 3).

-

42|Fit a Gaussian distribution,

directly to the raw image with subtracted background and obtain the Gaussian bead parameter of each tracked nanoparticle (Fig. 3). These parameters include particle location at subpixel resolution, µx and µy, the peak intensity of the nanoparticle, IP, and nanoparticle apparent size, a. Use these parameters, including background intensity, to synthesize a noise-free mimic image of the tracked particle. Introduce the CCD noise to the synthetic image based on the measured camera S-N curve and locate the particle position using the identical tracking protocol as in estimation particle positions. Repeat this procedure 1,000 times with random noise in image intensity and measure the variance of position distribution in the x and y directions, σx and σy. Obtain the static error σs by summing up 2σx and 2σy (Fig. 3).

Calculate the time lag–dependent MSD from each particle trajectory

-

43|

Using the equation MSD(τ) = {x(t + τ) − x(t)}2 + {y(t + τ) − y(t)}2, calculate the reliability score for individual tracking result by computing (MSD − σs) / σs. A high value for this reliability score corresponds to a high resolution of the calibrated MSD (MSDC); generally, we set the reliability score to a value >0.1 to ensure that we use high-resolution MSDC for microrheology analysis.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

44|

Discard the tracking results when the reliability score is <0.1.

-

45|Obtain the calibrated MSD, MSDC, by subtracting σs from the MSD (Fig. 3)56. It can be shown that the local creep compliance, Γ(τ), of the cytoplasm is directly proportional to the MSD42:

Here kB is the Boltzmann constant, T is the absolute temperature and a is the radius of the particle. The creep compliance is a measure of the deformability of the cytoplasm: a high compliance would indicate that the cytoplasm deforms readily under mechanical stress; a low compliance would indicate that the cytoplasm does not deform easily. By using a conventional rheometer, the creep compliance of a material is obtained by subjecting the material to a suddenly applied mechanical stress of constant magnitude and measuring the deformation as a function of time induced in the material; it is usually measured using a so-called stress-controlled rheometer. Γ has the units of inverse pressure (Pa− 1 or cm2 dyn− 1). Similarly to the MSD of beads diffusing in a viscous liquid (e.g., water), Γ(τ) is proportional to the time lag τ and inversely proportional to the cytoplasmic shear viscosity. For an elastic solid (e.g., a gel), Γ(τ) is independent of τ and is the inverse of the elastic (shear) modulus of the solid.▲ CRITICAL STEP It is crucial to assess whether the slope of the time-dependent MSD(τ) grows faster than τ. In this case, nanoparticles undergo directed motion within the cells, probably because nanoparticles were not directly inserted into the cytoplasm of the cell during the injection step and are transported by motor proteins. In this case, ballistic injection has to be repeated on new cells and additional washing steps have to be taken to avoid uptake of nanoparticles by the cell.

-

46|

Smooth the logarithmic MSD along the logarithmic time lag using the Savitzky-Golay filter with window span 11 and second-order polynomial57 (Box 1). This mathematical transformation improves the estimation of the first derivative of the MSD with respect to the time lag by smoothing the often-fluctuating time lag-dependent MSD curve.

-

47|Fit the smoothed logarithmic MSD with a third-order polynomial with the time lag–dependent weight, Wi(τ), where

Here Δt is the time step size in the tracking and T is the length of the total observation time. This weight function is determined by the resolution of MSD realization58, which is dependent on the data size; generally, data size decreases with increasing time lag and hence MSD from a larger time lag is less accurate. Obtain the first derivative, α(τ), and the second derivative, β(τ), of the logarithm MSD-time lag curve. -

48|Calculate the frequency-dependent viscoelastic modulus, G*(ω), using a generalized Stokes-Einstein equation11,59 through the following mathematical expression (Box 1):

Here ω = 1/τ, kB is the Boltzmann constant, a is the radius of the particle and Γ is the gamma function (not to be confused with the creep compliance, Γ(τ), which is italicized). -

49|

Obtain the smoothed G* value via a Savitzky-Golay filter in the logarithmic space over a discrete frequency data point using a second-order polynomial57 (Fig. 3). Fit the G* − ω curve using a third-order polynomial in the logarithmic space. Compute the first derivative, αG (ω), and the second derivative, βG(ω), directly from the fitted polynomial model at every frequency data point (Fig. 3).

-

50|Calculate the frequency-dependent elastic modulus, G′ (ω), and viscous modulus, G″(ω), of the specimen from the two equations (Fig. 3)59,60:

The frequency range for G′(ω) and G″(ω) is set by the range of timescales probed during multiple-particle tracking, from the lowest frequency corresponding to the inverse of the total time of collection of the movie (for the example shown in Fig. 4: 1/20 s = 0.05 Hz) up to the highest frequency corresponding to the inverse of the frame rate (for the example shown in Fig. 4: 30/s = 30 Hz). As the number of data points becomes smaller and smaller for increasing probed time lag, one loses accuracy at low frequencies. Therefore, MSDs and associated creep compliance are typically shown between 1/30 and 5 s (Fig. 4) instead of the 20 s of movie capture. Accordingly, the frequency-dependent moduli are shown only between 1/5 s = 0.2 and 30 Hz (Fig. 4). We selected a 1/30-s acquisition rate and 20 s of total acquisition time because these span the range of timescales most relevant to the dynamics of cytoskeleton remodeling and cell motility events.? TROUBLESHOOTING

Troubleshooting advice can be found in Table 4.

Figure 4.

htBIN analysis of normal and cancer human ovarian epithelial cells. (a,b) Twenty-second-long trajectory (a) and corresponding MSD (b) of a ballistically injected, 100-nm-diameter, fluorescent, polystyrene nanoparticle embedded in the cytoplasm of an OSE10 normal human ovarian epithelial cell. The trajectory is color coded to show the evolution of the movements of the nanoparticle. (c) Ensemble-averaged MSDs of nanoparticles in OSE10 cells (blue line) and OVCAR3 human ovarian cancer cells (green line). At least 100 nanoparticles were tracked for each type of cell. (d) Averaged creep compliance, Γ(τ), of OSE10 (blue) and OVCAR3 cells (green) directly computed from c. (e) Frequency-dependent viscous (continuous line) and elastic moduli (threaded line), G′(ω) and G″(ω), of OSE10 cells (blue) and OVCAR3 (green) computed from ensemble-averaged MSDs in c. (f,g). Shear viscosity (f) and elastic modulus evaluated at a frequency ω = 1 s−1 (g) of OSE10 cells (blue) and OVCAR3 (green). 1 Poise = 0.1 Pa.s; 1 dyn cm−2 = 0.1 Pa.

Table 4.

Troubleshooting table.

| Step | Problem | Possible reason | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Particle solution is extremely clear and appears to have a very low concentration of fluorescent particles | Membrane closure clip was not fully snapped, and thus the particle solution leaked into the ethanol bath. Membrane was not intact | Repeat Steps 1–5, ensuring that membrane closure clips are fully closed |

| 8 | Particle solution does not air dry and remains in liquid form on macrocarrier | Dialysis and exchange of water solvent for ethanol was unsuccessful | Redialyze particle solution against a fresh 3 liters of 100% ethanol |

| 22 | Vacuum does not reach/maintain 28 in Hg | Door is not fully closed or door seal is compromised | Ensure that the door of the bombardment chamber is fully closed and that the black tab to lock the door is fully depressed |

| Rupture disk is not sealed well | Ensure that rupture disk is fully wetted with isopropanol to provide a good seal within the bombardment capsule | ||

| 23 | ‘Pop’ does not occur during bombardment | Bombardment does not occur because of the presence of multiple rupture disks | Reload the bombardment capsule using only a single rupture disk |

| The golden pressure gauge does not reach the target rupture disk pressure | Ensure that the tank is not empty and is regulated to a pressure above the target rupture disk pressure. If the tank is low on helium, replace the tank | ||

| Rupture disk is not sealed well | Ensure that the rupture disk is fully wetted with isopropanol to provide a good seal within the bombardment capsule | ||

| 24 | The majority of cells are detached or cells look extremely unhealthy immediately after bombardment | High rupture pressures can agitate sensitive cell lines, causing significant cell detachment, particularly in cell lines that grow in colonies | Reduce rupture disk pressure Increase bombardment capsule-macrocarrier assembly platform and/or macrocarrier assembly platform-cell culture dish platform distances in bombardment chamber |

| 25,26 | Many cells are present in the cell culture dish after bombardment, but only a few remain after the post-bombardment wash with HBSS | Cells that adhere weakly to a substrate (e.g., MDA-MB-231) may remain in the plate following bombardment, but subsequent washing may detach the cells | To avoid aspiration of these detached cells, collect the first 10 ml of HBSS used to wash the cells in a 15-ml conical tube. Centrifuge, aspirate supernatant, resuspend cells and plate to original cell culture dish |

| 33 | Poor bombardment efficiency; few particles are present in cells | Particles did not have enough momentum to penetrate the plasma membrane | Bombard cells using a rupture disk with a higher pressure rating |

| Partially wet cells limited efficiency of particle penetration | Thoroughly aspirate cellular growth media in Step 19 | ||

| Particles appear aggregated when viewed under the microscope; individual particles cannot be resolved | Particle aggregates form in solution over time | Thoroughly vortex particle solution before coating macrocarriers If aggregation persists, sonicate the particle solution for 30 min before coating macrocarriers | |

| 43 | A substantial portion of particle MSDs are greater than 1 on a log-log plot, indicating active or convective particle motion | Particles may have become endocytosed immediately following bombardment | Ensure that cells are thoroughly washed post bombardment to minimize the number of endocytosed particles |

| Though carboxylated particles show minimal binding to cytoplasmic proteins, a small population of particles may still bind to superdiffusive entities within the cell | Superdiffusive particles can be identified by MSD, and if their motion is confirmed to be atypical in particle tracking movies, these particles should be removed from the computation of the ensemble-averaged MSD, as they will not reflect the mechanical properties of the cytoskeleton |

● TIMING

Steps 1–5, Dialyze particles against ethanol to replace stock solvent: 24 h (Steps 1–3: 10 min; Step 4: 24 h; Step 5: 5 min)

Steps 6–8, Coat macrocarriers with fluorescent particles: 40 min (Steps 6–7: 10 min; Step 8: 30 min)

Steps 9–16, Load the biolistic delivery system for particle bombardment: 20 min

Steps 17–26, Transfer of particles into cells via bombardment: 10 min

Steps 27–31, Replate cells for microscopy: 23 h (Step 27: 4 h; Steps 28–31: 1 h, plus incubation time)

Step 32, Track particles in living cells at high spatiotemporal resolution with video microscopy: 2 h

Steps 33–50, Particle identification, analysis and extraction of viscoelastic properties: 2 h

ANTICIPATED RESULTS

An example of the application of htBIN is shown in Figure 3. Fluorescent carboxylated nanoparticles (100-nm diameter) were diluted from a stock solution, sonicated and placed onto a macrocarrier placed into the BD biolistic machine (Fig. 2). Fluorescent carboxylated nanoparticles (100-nm diameter) were ballistically injected into the cytoplasm of human ovarian cancer cells as described in the PROCEDURE. To minimize damage to the cells and maximize the number of nanoparticles per cell, the distance between the microcarrier containing the nanoparticles and the apical surface of the cells, as well as the magnitude of the pressure drop, was optimized (Fig. 2 and Table 3). Reducing the distance between the microcarrier and the cells will increase the number of nanoparticles inserted in cells, but will also increase the affect of beads on cells (i.e., cell death and vice versa). Table 3 provides the pressure drops used for a wide range of cell types and should be used as a guideline for future applications of htBIN.

The trajectories of the fluorescent nanoparticles were recorded simultaneously at 30 f.p.s. using a ×60 lens on a high-resolution fluorescence microscope and a computer-controlled video camera. Tracking was conducted for 20 s, three times per cell. At least 20 cells were assessed on three different days for a total of at least 60 distinct cells. The coordinates of the nanoparticles locations were measured with <5-nm spatial resolution and 30-ms temporal resolution (total 600 frames per movie per cell). The stage is computer controlled to move quickly from one cell to another, and to track nanoparticles in at least 20 cells within 1 h. Movies of nanoparticle movements were filtered and analyzed following Steps 33–50 described in the protocol above (Fig. 2). The MSDs of individual nanoparticles (Fig. 3a,b) were transformed into local frequency-dependent moduli (Fig. 3e). These measurements show that the local mechanical properties of cells vary not only from cell to cell, but also within a cell. To improve presentation, beads can be color coded according to the values of these moduli.

htBIN analysis can be used to compare the viscoelastic moduli of different cell types

Figure 3 shows an example in which we compared the time-dependent MSDs and associated viscoelastic moduli of normal (OSE10; Fig. 3a) and cancer ovarian epithelial cells (OVCAR3; Fig. 3b). These htBIN measurements showed that the MSDs of nanoparticles embedded in the cytoplasm of cancer cells were lower in magnitude and showed a lower slope compared with normal ovarian epithelial cells (Fig. 3c,d), indicative of a more liquid-like behavior of normal cells compared with ovarian cancer cells within the probed timescales. Computation of viscoelastic moduli from MSDs indeed shows that both normal and cancer cells are more viscous than elastic (i.e., their cytoplasm is a viscoelastic liquid; Fig. 3e) and that both elastic and viscous moduli of cancer cells were higher than those of normal cells12. Moreover, the creep compliance of normal cells is higher than the cancer cells and the slope of the compliance as a function of time lag τ in a log-log plot is higher than 0.5 but lower than 1.0, which is indicative of the viscoelastic liquid behavior of both types of cells (Fig. 3d)42. It is important to notice that in this case both frequency-dependent viscoelastic moduli became parallel to each other (because of Kramers-Kronig relations) and approximately proportional to ω0.75; this reflects the semiflexible nature of cytoskeleton polymers51,61,62.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Normal human ovarian epithelial cells (OSE10) and ovarian cancer cells (OVCAR3) were provided by I.-M. Shih (Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine). This work was supported in part by NIH grants U54CA143868 and R21CA137686, and RO1GM084204. We thank members of the Wirtz and Tseng labs for technical advice and reagents.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS P.-H.W., C.M.H. and W.-C.C. conducted experiments. P.-H.W., C.M.H., J.S.H.L., Y.T. and D.W. designed the experiments, analyzed the results and wrote the paper.

COMPETING FINANCIALINTERESTS The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Hoh JH, Schoenenberger CA. Surface morphology and mechanical properties of MDCK monolayers by atomic force microscopy. J. Cell. Sci. 1994;107:1105–1114. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.5.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Radmacher M, Cleveland JP, Fritz HG, Hansma HG, Hansma PK. Mapping interactions forces with the AFM. Biophys. J. 1994;66:2159–2165. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)81011-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domke J, Parak WJ, George M, Gaub HE, Radmacher M. Mapping the mechanical pulse of single cardiomyocytes with the atomic force microscope. Eur. Biophys. J. 1999;28:179–186. doi: 10.1007/s002490050198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radmacher M. Studying the mechanics of cellular processes by atomic force microscopy. Methods Cell. Biol. 2007;83:347–372. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(07)83015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hale CM, Sun SX, Wirtz D. Resolving the role of actoymyosin contractility in cell microrheology. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniels BR, Masi BC, Wirtz D. Probing single-cell micromechanics in vivo: the microrheology of C. elegans developing embryos. Biophys. J. 2006;90:4712–4719. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.080606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JS, et al. Ballistic intracellular nanorheology reveals ROCK-hard cytoplasmic stiffening response to fluid flow. J. Cell. Sci. 2006;119:1760–1768. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panorchan P, Lee JS, Kole TP, Tseng Y, Wirtz D. Microrheology and ROCK signaling of human endothelial cells embedded in a 3D matrix. Biophys. J. 2006;91:3499–3507. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.084988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou X, et al. Fibronectin fibrillogenesis regulates three-dimensional neovessel formation. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1231–1243. doi: 10.1101/gad.1643308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lekka M, Laidler P. Applicability of AFM in cancer detection. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009;4:72. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.004. author reply 72–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mason TG, Ganesan K, van Zanten JV, Wirtz D, Kuo SC. Particle-tracking microrheology of complex fluids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997;79:3282–3285. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wirtz D. Particle-tracking microrheology of living cells: principles and applications. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2009;38:301–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.050708.133724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu J, Dai LL. Apparent microrheology of oil-water interfaces by single-particle tracking. Langmuir. 2007;23:4324–4331. doi: 10.1021/la0625190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson LG, Harrison AW, Schofield AB, Arlt J, Poon WC. Passive and active microrheology of hard-sphere colloids. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:3806–3812. doi: 10.1021/jp8079028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vanapalli SA, Li Y, Mugele F, Duits MH. On the origins of the universal dynamics of endogenous granules in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biomech. 2009;6:191–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sivaramakrishnan S, DeGiulio JV, Lorand L, Goldman RD, Ridge KM. Micromechanical properties of keratin intermediate filament networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:889–894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710728105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silburn SA, Saunter CD, Girkin JM, Love GD. Multidepth, multiparticle tracking for active microrheology using a smart camera. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2011;82:033712. doi: 10.1063/1.3567801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selvaggi L, et al. Multiple-particle-tracking to investigate viscoelastic properties in living cells. Methods. 2010;51:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savin T, Doyle PS. Static and dynamic errors in particle tracking microrheology. Biophys. J. 2005;88:623–638. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.042457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogers SS, Waigh TA, Lu JR. Intracellular microrheology of motile Amoeba proteus. Biophys. J. 2008;94:3313–3322. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.123851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers SS, van der Walle C, Waigh TA. Microrheology of bacterial biofilms in vitro: Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Langmuir. 2008;24:13549–13555. doi: 10.1021/la802442d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rathgeber S, Beauvisage HJ, Chevreau H, Willenbacher N, Oelschlaeger C. Microrheology with fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Langmuir. 2009;25:6368–6376. doi: 10.1021/la804170k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papagiannopoulos A, Waigh TA, Hardingham TE. The viscoelasticity of self-assembled proteoglycan combs. Faraday Discuss. 2008;139:337–357. doi: 10.1039/b714864j. discussion 399–417, 419–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papagiannopoulos A, Fernyhough CM, Waigh TA. The microrheology of polystyrene sulfonate combs in aqueous solution. J. Chem. Phys. 2005;123:214904. doi: 10.1063/1.2136888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moschakis T, Murray BS, Dickinson E. Particle tracking using confocal microscopy to probe the microrheology in a phase-separating emulsion containing nonadsorbing polysaccharide. Langmuir. 2006;22:4710–4719. doi: 10.1021/la0533258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsen TH, Furst EM. Microrheology of the liquid-solid transition during gelation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;100:146001. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.146001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasnain IA, Donald AM. Microrheological characterization of anisotropic materials. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2006;73:031901. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.73.031901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haro-Perez C, Garcia-Castillo A, Arauz-Lara JL. Confinement-induced fluid-gel transition in polymeric solutions. Langmuir. 2009;25:8911–8914. doi: 10.1021/la902070q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.del Alamo JC, Norwich GN, Li YS, Lasheras JC, Chien S. Anisotropic rheology and directional mechanotransduction in vascular endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:15411–15416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804573105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crocker JC, Hoffman BD. Multiple-particle tracking and two-point microrheology in cells. Methods Cell. Biol. 2007;83:141–178. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(07)83007-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corrigan AM, Donald AM. Particle tracking microrheology of gel-forming amyloid fibril networks. Eur. Phys. J. E Soft Matter. 2009;28:457–462. doi: 10.1140/epje/i2008-10439-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corrigan AM, Donald AM. Passive microrheology of solvent-induced fibrillar protein networks. Langmuir. 2009;25:8599–8605. doi: 10.1021/la804208q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baker EL, Lu J, Yu D, Bonnecaze RT, Zaman MH. Cancer cell stiffness: integrated roles of three-dimensional matrix stiffness and transforming potential. Biophys. J. 2010;99:2048–2057. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baker EL, Bonnecaze RT, Zaman MH. Extracellular matrix stiffness and architecture govern intracellular rheology in cancer. Biophys. J. 2009;97:1013–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alam MM, Mezzenga R. Particle tracking microrheology of lyotropic liquid crystals. Langmuir. 2011;27:6171–6178. doi: 10.1021/la200116e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Addas KM, Schmidt CF, Tang JX. Microrheology of solutions of semiflexible biopolymer filaments using laser tweezers interferometry. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2004;70:021503. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.70.021503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tseng Y, Kole TP, Wirtz D. Micromechanical mapping of live cells by multiple-particle-tracking microrheology. Biophys. J. 2002;83:3162–3176. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75319-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kole TP, Tseng Y, Wirtz D. Intracellular microrheology as a tool for the measurement of the local mechanical properties of live cells. Methods Cell. Biol. 2004;78:45–64. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(04)78003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kole TP, Tseng Y, Huang L, Katz JL, Wirtz D. Rho kinase regulates the intracellular micromechanical response of adherent cells to rho activation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:3475–3484. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kole TP, Tseng Y, Jiang I, Katz JL, Wirtz D. Intracellular mechanics of migrating fibroblasts. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:328–338. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-06-0485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupton SL, et al. Cell migration without a lamellipodium: translation of actin dynamics into cell movement mediated by tropomyosin. J. Cell. Biol. 2005;168:619–631. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu J, Viasnoff V, Wirtz D. Compliance of actin filament networks measured by particle-tracking microrheology and diffusing wave spectroscopy. Rheologica. Acta. 1998;37:387–398. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tseng Y, et al. How actin crosslinking and bundling proteins cooperate to generate an enhanced cell mechanical response. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;334:183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Panorchan P, et al. Probing cellular mechanical responses to stimuli using ballistic intracellular nanorheology. Methods Cell. Biol. 2007;83:115–140. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(07)83006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee JS, et al. Nuclear lamin A/C deficiency induces defects in cell mechanics, polarization, and migration. Biophys. J. 2007;93:2542–2552. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.102426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rufener K, Palmer A, Xu J, Wirtz D. High-frequency dynamics and microrheology of macromolecular solutions measured by diffusing wave spectroscopy: the case of actin filament networks. J. NonNewtonian Fluid. Mech. 1999;82:303–314. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mason TG, Dhople A, Wirtz D. In: Statistical Mechanics in Physics and Biology. Wirtz D, Halsey TC, editors. Materials Research Society; 1997. pp. 153–158. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mizuno D, Tardin C, Schmidt CF, Mackintosh FC. Nonequilibrium mechanics of active cytoskeletal networks. Science. 2007;315:370–373. doi: 10.1126/science.1134404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lau AW, Hoffman BD, Davies A, Crocker JC, Lubensky TC. Microrheology, stress fluctuations, and active behavior of living cells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003;91:198101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.198101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoffman BD, Massiera G, Van Citters KM, Crocker JC. The consensus mechanics of cultured mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:10259–10264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510348103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamada S, Wirtz D, Kuo SC. Mechanics of living cells measured by laser tracking microrheology. Biophys. J. 2000;78:1736–1747. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76725-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spence P, Gupta V, Stephens DJ, Hudson AJ. Optimising the precision for localising fluorescent proteins in living cells by 2D Gaussian fitting of digital images: application to COPII-coated endoplasmic reticulum exit sites. Eur. Biophys. J. 2008;37:1335–1349. doi: 10.1007/s00249-008-0343-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crocker JC, Grier DG. Methods of digital video microscopy for colloidal studies. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1996;179:298–310. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gonzalez RC, Woods RE. Digital Image Processing. Prentice Hall; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu PH, Nelson N, Tseng Y. A general method for improving spatial resolution by optimization of electron multiplication in CCD imaging. Opt. Express. 2010;18:5199–5212. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.005199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu PH, Arce SH, Burney PR, Tseng Y. A novel approach to high accuracy of video-based microrheology. Biophys. J. 2009;96:5103–5111. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Savitzky A, Golay MJE. Smoothing and differentiation of data by simplified least squares procedures. Anal. Chem. 1964;36:1627–1639. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qian H, Sheetz MP, Elson EL. Single particle tracking. Analysis of diffusion and flow in two-dimensional systems. Biophys. J. 1991;60:910–921. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82125-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mason TG. Estimating the viscoelastic moduli of complex fluids using the generalized Stokes-Einstein equation. Rheologica. Acta. 2000;39:371–378. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dasgupta BR, Tee S-Y, Crocker JC, Friseken BJ, Weitz DA. Microrheology of polyethylene oxide using diffusing wave spectroscopy and single scattering. Phys. Rev. E. 2002;65:051505. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.65.051505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Palmer A, Xu J, Wirtz D. High-frequency rheology of crosslinked actin networks measured by diffusing wave spectroscopy. Rheologica. Acta. 1998;37:97–108. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Palmer A, Xu J, Kuo SC, Wirtz D. Diffusing wave spectroscopy microrheology of actin filament networks. Biophys. J. 1999;76:1063–1071. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77271-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Daniels BR, et al. Differences in the microrheology of human embryonic stem cells and human induced pluripotent stem cells. Biophys. J. 2010;99:3563–3570. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hale CM, et al. Dysfunctional connections between the nucleus and the actin and microtubule networks in laminopathic models. Biophys. J. 2008;95:5462–5475. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.139428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stewart-Hutchinson PJ, Hale CM, Wirtz D, Hodzic D. Structural requirements for the assembly of LINC complexes and their function in cellular mechanical stiffness. Exp. Cell. Res. 2008;314:1892–1905. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tseng Y, Lee JS, Kole TP, Jiang I, Wirtz D. Micro-organization and visco-elasticity of the interphase nucleus revealed by particle nanotracking. J. Cell. Sci. 2004;117:2159–2167. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baker EL, Lu J, Yu D, Bonnecaze RT, Zaman MH. Cancer cell stiffness: integrated roles of three-dimensional matrix stiffness and transforming potential. Biophys. J. 2010;99:2048–2057. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rahman A, Tseng Y, Wirtz D. Micromechanical coupling between cell surface receptors and RGD peptides. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;296:771–778. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00903-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fire A. Integrative transformation of Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J. 1986;5:2673–2680. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Panorchan P, Tseng Y, Wirtz D. Structure-function relationship of biological gels revealed by multiple particle tracking and differential interference contrast microscopy: The case of human lamin networks. Phys. Rev. E. 2004;70:041906. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.70.041906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fraley SI, et al. A distinctive role for focal adhesion proteins in three-dimensional cell motility. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12:598–604. doi: 10.1038/ncb2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fraley SI, Feng Y, Wirtz D, Longmore GD. Reply: reducing background fluorescence reveals adhesions in 3D matrices. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;13:5–7. doi: 10.1038/ncb0111-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]