Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to determine the impact of prosthesis–patient mismatch on long-term survival after mitral valve replacement.

Methods

From 1992 to 2008, 765 patients underwent bioprosthetic (325; 42%) or mechanical (440; 58%) mitral valve replacement, including 370 (48%) patients older than 65 years of age. Prosthesis–patient mismatch was defined as severe (prosthetic effective orifice area to body surface area ratio <0.9 cm2/m2), moderate (0.9 to 1.2 cm2/m2), or absent (>1.2 cm2/m2).

Results

Multivariate analysis identified nine risk factors for late death including advanced age, earlier operative year, chronic renal insufficiency, peripheral vascular disease, congestive heart failure, nonrheumatic origin, concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting, lower body surface area, and more severe prosthesis–patient mismatch (lower effective orifice area to body surface area ratio; p < 0.05). For bioprosthetic recipients older than 65 years of age, survival at 5 and 10 years was 30% ± 7% and 0% ± 0% with severe mismatch compared with 43% ± 4% and 21% ± 5% for absent or moderate mismatch, respectively (p = 0.05). For mechanical recipients younger than 65 years of age, survival at 5 and 10 years was 77% ± 4% and 62% ± 6% with moderate or severe mismatch compared with 82% ± 3% and 66% ± 4%, respectively, without mismatch (p = 0.08).

Conclusions

Severe mismatch adversely affected long-term survival for older patients receiving bioprosthetic valves. With mechanical valves, there was a trend toward impaired survival when mismatch was moderate or severe in younger patients. Thus, selection of an appropriate mitral prosthesis warrants careful consideration of age and valve type.

More than 30 years ago, Rahimtoola [1] and Rahimtoola and Murphy [2] initially described the phenomenon of prosthesis–patient mismatch (PPM), concluding that “the long-term consequences of mismatch . . . are not known” [1]. Contrary to progress that has been made understanding the impact of PPM on outcomes after aortic valve replacement [3–7], the long-term sequelae of PPM after mitral valve replacement (MVR) remain controversial. For the mitral valve, there have been limited studies evaluating the phenomenon of PPM after MVR [8–14], with most previous studies exhibiting significant selection bias by combining mechanical and bioprosthetic recipients of all ages during statistical analyses. The purpose of the current investigation was to identify patient subgroups in which PPM most influenced outcome after MVR, specifically examining the impact of patient age and prosthesis type on long-term survival.

Material and Methods

Patient Selection and Surgical Procedures

This study was approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board, including a waiver of the need for patient consent for this retrospective study. During a 16-year period (May 1992 to June 2008), 1,678 patients underwent a mitral valve procedure at Washington University School of Medicine (Barnes-Jewish Hospital) by 20 different surgeons. Of these, 765 (46%) underwent MVR and are the subject of this analysis. There were 460 (60%) women and 305 (40%) men, with a mean age (± 1 standard deviation) of 62 ± 15 years (range, 20 to 90 years); 395 (52%) were younger than 65 years of age. Indications for MVR included rheumatic origin (37%), myxomatous degeneration (27%), endocarditis (18%), structural valve degeneration (11%), and ischemic regurgitation (7%). Previous cardiac procedures included MVR in 83 (11%), coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) in 93 (12%), and aortic valve replacement in 8 (1%). Concomitant procedures included CABG (106 patients; 26%), aortic valve replacement (179; 23%), tricuspid valve repair (84; 11%) or replacement (9; 1%), and a Cox-Maze procedure (59; 8%).

Replacement prostheses included 325 (42%) bioprosthetic and 440 (58%) mechanical valves. Table 1 enumerates specific valve types, and Figure 1 demonstrates a shift toward mitral valve repair and bioprosthetic valves in the later years of the study. For patients younger than 65 years of age, mechanical MVR was more common (76% mechanical, 24% bioprosthetic). For patients older than 65 years of age, bioprosthetic MVR was more common (62% bioprosthetic, 38% mechanical). Valve sizes included 118 (15%) 23 to 25 mm, 204 (27%) 27 mm, 228 (30%) 29 mm, and 215 (28%) 31 to 33 mm. Ideally, effective orifice area (EOA) would have been determined postoperatively for each patient's prosthesis, but postoperative echocardiography was inconsistent in the retrospective series. Therefore, estimates of EOA for each valve type and size were obtained from referenced normal values as summarized in Table 1 [11, 12, 15–19]. In no circumstances were EOA values obtained from the valve manufacturers. Rather, EOA values were averaged from previously published peer-reviewed manuscripts in cardiology or cardiothoracic surgery journals and textbooks. Mean body surface area (BSA) was 1.86 ± 0.25 m2. Indexed EOA was defined as prosthetic EOA divided by BSA, and PPM was defined as severe (EOA/BSA <0.9 cm2/m2), moderate (0.9 to 1.2 cm2/m2), or absent (>1.2 cm2/m2) [11–13].

Table 1.

Valves Implanted and Effective Orifice Area Based on Referenced Normal Values

| Effective Orifice Area (cm2) | Patients | 25 mm | 27 mm | 29 mm | 31 mm | 33 mm | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioprosthetic valves | |||||||

| Hancock Standard | 150 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 15, 19 |

| Carpentier-Edwards Pericardial | 80 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 11, 12, 19 |

| Hancock II | 64 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 12, 16 |

| Carpentier-Edwards Porcine | 12 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 15, 19 | ||

| Biocor | 12 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 18 | ||

| Medtronic Mosaic | 7 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 11, 17 | ||

| Mechanical valves | |||||||

| St. Jude Medical | 359 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 11, 12, 19 |

| Carbomedics | 29 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 12, 19 |

| Medtronic-Hall | 25 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 12, 19 |

| On-X | 19 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 11, 12 | |

| Other mechanicala | 8 |

Different values for each valve type.

Fig 1.

Numbers of bioprosthetic (solid circles, solid line) and mechanical (open circles, dotted line) prostheses implanted in the mitral position between 1992 and 2008. The number of mitral valve repair procedures is also demonstrated (solid squares, dashed line).

Survival data were obtained for all 765 patients during a 2-month closing interval ending August 2008 through interrogation of the Barnes-Jewish Hospital medical records database and the Social Security Death Index. Cumulative long-term follow-up totaled 3,683 patient-years. Mean follow-up for all patients in this study was 58 ± 51 months, and 362 (47%) were alive an average of 77 ± 49 months postoperatively.

Data Analysis

Operative mortality included deaths during initial hospitalization or within 30 days of operation for discharged patients. Late survival data included death from all causes. Continuous data are reported as mean ± one standard deviation and were compared among groups using analysis of variance. Clinically important ratios are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Actuarial survival estimates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and were compared using the Mantel log-rank test. We report actuarial estimate variability as ± one standard error of the mean. Univariate and multivariate analysis were used to determine the preoperative and intraoperative risk factors that were significant independent predictors of PPM and death (SigmaStat 2.03, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Univariate analysis was performed for categorical variables using the χ2 test and for continuous variables using linear regression. Multivariate analysis was performed using stepwise backward regression including only factors identified to be signifi-cant during univariate analysis (p < 0.05). Odds ratios (OR) are reported with 95% CI, and regression coefficients for continuous variables are reported with standard error of the mean.

Twenty-seven variables were analyzed: age, year of operation, sex, hypertension, diabetes, chronic pulmonary disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, chronic renal insufficiency, history of myocardial infarction, smoking history, congestive heart failure, pulmonary hypertension (not collected before 1996), ejection fraction, status (urgent, elective), endocarditis, New York Heart Association class, presence of mitral stenosis, degree of mitral regurgitation, rheumatic origin, previous cardiac operation, previous mitral valve procedure, concomitant CABG, concomitant aortic valve replacement, prosthesis type (mechanical, bioprosthetic), BSA, and degree of PPM (EOA/BSA).

Results

Patient Demographics

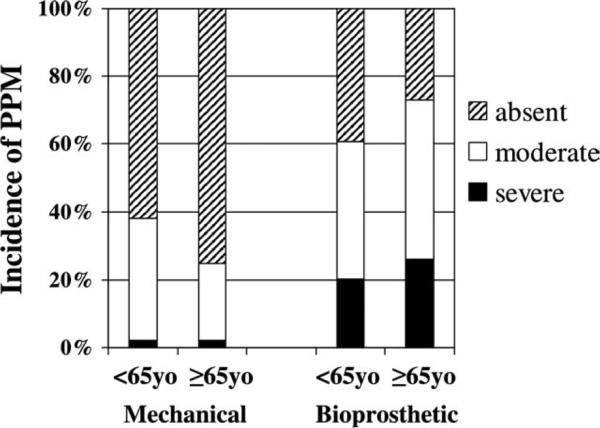

For the total series PPM was severe in 14% (107 patients), moderate in 37% (286), and absent in 49% (372). In mechanical valves, PPM was severe in 2% (10 of 440 patients), moderate in 32% (140), and absent in 66% (290). Prosthesis–patient mismatch was less common with mechanical valves than with biomechanical (p < 0.001). In bioprosthetic valves, PPM was severe in 30% (97 of 325 patients), moderate in 45% (146), and absent in 25% (82). Table 2 summarizes selected preoperative and intraoperative patient characteristics. Moderate or severe PPM was more common in women and patients with endocarditis, diabetes, and chronic renal disease. Ejection fraction was similar among groups, as was the percentage of patients with an ejection fraction of 0.35 or less (23% absent, 18% moderate, 20% severe; p = 0.45). With mechanical valves, the incidence of severe and moderate PPM was higher in younger patients (p = 0.05), but with bioprosthetic valves, the incidence of PPM was higher in older patients (p = 0.03; Fig 2). Multivariate analysis identified four factors to be independent predictors of severe PPM: (1) advanced age (p = 0.006; coefficient = 0.002 ± 0.001), (2) diabetes mellitus (p < 0.001; OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.9 to 4.4), (3) chronic renal disease (p = 0.003; OR, 2.2; OR, 1.3 to 3.6), and (4) bioprosthetic valves (p < 0.001; OR, 18.3; OR, 9.4 to 35.8).

Table 2.

Characteristics for Patients Undergoing Mitral Valve Replacementa

| Variable | No PPM (n = 372) | Moderate PPM (n = 286) | Severe PPM (n = 107) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 60 ± 15 | 62 ± 14 | 65 ± 13 | 0.01 |

| Patients <65 y | 205 (55%) | 146 (51%) | 44 (41%) | 0.04 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 1.76 ± 0.20 | 1.95 ± 0.23 | 1.97 ± 0.31 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 57 (15%) | 75 (26%) | 45 (42%) | <0.001 |

| Chronic renal disease | 47 (13%) | 38 (13%) | 26 (24%) | 0.008 |

| Ejection fraction | 0.47 ± 0.13 | 0.48 ± 0.13 | 0.47 ± 0.14 | 0.31 |

| Emergent/urgent status | 49 (13%) | 35 (12%) | 16 (15%) | 0.77 |

| Endocarditis | 62 (17%) | 47 (16%) | 31 (29%) | 0.009 |

| Bioprosthetic valve implanted | 82 (22%) | 146 (51%) | 97 (91%) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary hypertensionb | 178/290 (61%) | 156/246 (63%) | 66/99 (67%) | 0.66 |

Continuous variables are mean ± standard deviation. Groups were compared using analysis of variance or χ2 test as appropriate. Probability values refer to the comparison among all three groups.

Not collected before 1996.

PPM = prosthesis-patient mismatch.

Fig 2.

Incidence of prosthesis–patient mismatch (PPM) during mechanical (left) and bioprosthetic (right) aortic valve replacement in patients younger than 65 years of age and in patients 65 years of age and older.

Operative Mortality

Operative mortality was 12.7% ± 2.4% (97 of 765 patients), but increased as the complexity of the procedure increased from 5% for an isolated, nonendocarditis MVR to 43% for an emergent, combined MVR and CABG procedure (Table 3). Univariate analysis identified 13 factors associated with operative mortality (Table 4), of which multivariate analysis identified 7 factors to be independent predictors of operative mortality: active endocarditis, chronic renal insufficiency, peripheral vascular disease, nonrheumatic origin, concomitant CABG, urgent or emergent status, and implantation of a bioprosthetic valve (Table 4). Operative mortality was higher with severe PPM (24% ± 8%) compared with moderate PPM (14% ± 4%) or absent PPM (8% ± 3%; p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Operative Mortality for Mitral Valve Replacement Based on the Complexity of the Procedure

| Procedure | Operative Mortality |

|---|---|

| MVR only—nonendocarditis | 5% ± 3% (15/292) |

| MVR only—endocarditis | 11% ± 7% (8/74) |

| MVR, CABG—elective | 16% ± 7% (19/118) |

| MVR, CABG—emergent | 43% ± 16% (16/37) |

| MVR/AVR or TVR | 16% ± 5% (32/203) |

| MVR, AVR, CABG | 17% ± 12% (7/41) |

AVR = aortic valve replacement; CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting; MVR = mitral valve replacement; TVR = tricuspid valve replacement.

Table 4.

Risk Factors for Operative Mortality for Patients Undergoing Mitral Valve Replacement (n = 765 Patients)

| Variable | Number of Patients With Variable (%) | Univariate Analysis |

Multivariate Analysis |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p Value | Odds Ratioa | p Value | ||

| Age | 765 (100) | 0.001 | 0.003 ± 0.001 | 0.13 |

| Operative year | 765 (100) | 0.11 | ||

| Female sex | 460 (60) | 0.13 | ||

| Hypertension | 398 (52) | 0.67 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 177 (23) | 0.79 | ||

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 162 (21) | 0.99 | ||

| Chronic renal disease | 111 (15) | 0.001 | 4.7 (2.6-6.7) | 0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 84 (11) | 0.001 | 2.7 (1.5-4.6) | 0.03 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 155 (20) | 0.44 | ||

| History of myocardial infarction | 178 (23) | 0.02 | 1.8 (1.2-2.6) | 0.55 |

| Smoking history | 447 (58) | 0.97 | ||

| Congestive heart failure | 599 (78) | 0.50 | ||

| Ejection fraction < 0.40b | 195 (38) | 0.25 | ||

| Pulmonary hypertensionc | 400 (63) | 0.07 | ||

| NYHA class IV | 250 (33) | 0.009 | 1.8 (1.2-2.8) | 0.21 |

| Mitral stenosis | 275 (36) | 0.002 | 0.5 (0.3-0.7) | 0.96 |

| Mitral regurgitation (3-4+) | 613 (80) | 0.25 | ||

| Nonrheumatic origin | 484 (63) | 0.001 | 3.6 (2.0-6.4) | 0.02 |

| Active endocarditis | 140 (18) | 0.003 | 2.7 (1.4-5.1) | 0.04 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 167 (22) | 0.93 | ||

| Previous mitral valve surgery | 83 (11) | 0.01 | 0.2 (0.1-0.7) | 0.06 |

| Concomitant coronary bypass | 196 (26) | 0.001 | 2.5 (1.6-4.0) | 0.005 |

| Concomitant AVR | 179 (23) | 0.14 | ||

| Urgent or emergent status | 100 (13) | 0.001 | 2.7 (1.6-4.6) | 0.008 |

| Bioprosthetic valve implanted | 325 (42) | 0.001 | 3.2 (2.0-5.0) | 0.001 |

| BSA | 765 (100) | 0.99 | ||

| EOA/BSA | 765 (100) | 0.001 | –0.173 ± 0.045 | 0.21 |

Odds ratios are reported with 95% confidence intervals for categorical variables. For continuous variables, regression coefficients are reported with standard error of the mean.

Ejection fraction was available in only 507 patients.

Pulmonary hypertension was not recorded before 1996 and was available in only 635 patients.

AVR = aortic valve replacement; BSA = body surface area; EOA = effective orifice area; NYHA = New York Heart Association.

Late Survival

Of the 668 operative survivors, there were 265 late deaths; 403 patients were alive at late follow-up. Univariate analysis identified 14 factors associated with operative mortality (Table 5), of which multivariate analysis identified 9 factors to be independent predictors of late death: advanced age, earlier operative year, chronic renal insufficiency, peripheral vascular disease, congestive heart failure, nonrheumatic origin, concomitant CABG, lower BSA, and more significant PPM (lower EOA/BSA; Table 5). Overall survival was 78% ± 2% at 1 year, 61% ± 2% at 5 years, and 43% ± 2% at 10 years with a mean survival time of 8.3 years. Excluding operative deaths, late survival was 90% ± 1% at 1 year, 70% ± 2% at 5 years, and 49% ± 3% at 10 years with mean survival of 9.5 years. Late survival was impaired with severe PPM (41% ± 9%) compared with moderate PPM (52% ± 6%) or absent PPM (56% ± 5%; p = 0.02).

Table 5.

Risk Factors for Late Death for Patients Undergoing Mitral Valve Replacement (n = 765 patients)a

| Variable | Univariate Analysis |

Multivariate Analysis |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| p Value | Odds Ratiob | p Value | |

| Age | 0.001 | 0.012 ± 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Operative year | 0.001 | –0.037 ± 0.004 | 0.001 |

| Female sex | 0.98 | ||

| Hypertension | 0.45 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.007 | 1.6 (1.2-2.3) | 0.12 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 0.17 | ||

| Chronic renal disease | 0.001 | 3.8 (2.4-5.9) | 0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0.001 | 2.9 (1.8-4.8) | 0.03 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.35 | ||

| History of myocardial infarction | 0.001 | 2.9 (2.0-4.1) | 0.09 |

| Smoking history | 0.38 | ||

| Congestive heart failure | 0.001 | 2.0 (1.4-2.8) | 0.03 |

| Ejection fraction <0.40 | 0.002 | 1.8 (1.2-2.6) | 0.24 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 0.75 | ||

| NYHA class IV | 0.10 | ||

| Mitral stenosis | 0.001 | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | 0.34 |

| Mitral regurgitation (3-1+) | 0.23 | ||

| Nonrheumatic origin | 0.001 | 1.8 (1.3-2.4) | 0.03 |

| Active endocarditis | 0.07 | ||

| Previous cardiac surgery | 0.34 | ||

| Previous mitral valve surgery | 0.86 | ||

| Concomitant coronary bypass | 0.001 | 3.7 (2.6-5.2) | 0.02 |

| Concomitant AVR | 0.52 | ||

| Urgent or emergent status | 0.18 | ||

| Bioprosthetic valve implanted | 0.001 | 2.1 (1.5-2.7) | 0.14 |

| BSA | 0.008 | –0.194 ± 0.073 | 0.005 |

| EOA/BSA | 0.04 | –0.140 ± 0.068 | 0.001 |

See Table 4 for number of patients with each variable.

Odds ratios are reported with 95% confidence intervals for categorical variables. For continuous variables, regression coefficients are reported with standard error of the mean.

AVR = aortic valve replacement; BSA = body surface area; EOA = effective orifice area; NYHA = New York Heart Association.

Impact of Prosthesis–Patient Mismatch on Late Survival

To investigate the potential impact of PPM on survival in various subgroups after MVR, and to account for selection bias with regard to bioprosthetic versus mechanical valve choice in young versus elderly patients, survival analyses were performed stratified by both age and prosthesis type. For patients younger than 65 years of age, PPM had a negative impact on survival. Including prosthesis type (bioprosthetic/mechanical) as a covariate, survival fell at 5 and 10 years from 79% ± 1% and 62% ± 2% without PPM to 73% ± 1% and 58% ± 4% with moderate PPM and stayed at 66% ± 4% and 66% ± 4% with severe PPM (p < 0.001; Fig 3). For patients 65 years of age and older, again including prosthesis type as a covariate, PPM also had a negative impact on survival. Survival at 5 and 10 years for older patients was 52% ± 2% and 26% ± 5% without PPM, 46% ± 2% and 28% ± 7% with moderate PPM, and 38% ± 6% and 12% ± 9% with severe PPM (p = 0.001; Fig 4). When operative mortality was excluded from the survival analyses, patients with moderate and severe PPM still had significantly lower late survival in both the younger (p = 0.03) and older (p = 0.01) patient subgroups.

Fig 3.

Impact of prosthesis–patient mismatch (PPM) on late survival for patients younger than 65 years of age undergoing mitral valve replacement. The numbers of patients at risk for each mismatch group are reported at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 years.

Fig 4.

Impact of prosthesis–patient mismatch (PPM) on late survival for patients 65 years of age and older undergoing mitral valve replacement. The numbers of patients at risk for each mismatch group are reported.

For the overall cohort of mechanical valve recipients, PPM did not significantly impact survival (p = 0.17). However, after stratifying by age, PPM tended to impact survival negatively after mechanical MVR in both age groups. Owing to relatively small numbers of patients in PPM subgroups when stratified by age with mechanical valves, absent PPM was compared with moderate or severe PPM. For patients younger than 65 years of age with mechanical valves, survival fell at 5 and 10 years from 82% ± 3% and 66% ± 4% without PPM to 77% ± 4% and 62% ± 6% with moderate or severe PPM (p = 0.06; Fig 5). Similarly, for mechanical valve recipients 65 years of age and older, survival at 5 and 10 years was 63% ± 5% and 40% ± 5% without PPM compared with only 47% ± 9% and 30% ± 10% with moderate or severe PPM (p = 0.07; Fig 6).

Fig 5.

Impact of moderate-to-severe prosthesis–patient mismatch (PPM) on late survival for patients younger than 65 years of age undergoing mechanical mitral valve replacement. The numbers of patients at risk for each mismatch group are reported.

Fig 6.

Impact of moderate-to-severe prosthesis–patient mismatch (PPM) on late survival for patients 65 years of age and older undergoing mechanical mitral valve replacement. The numbers of patients at risk for each mismatch group are reported.

For the overall cohort of bioprosthetic valve recipients, PPM did not significantly impact survival (p = 0.29). However, after stratifying by age, although PPM did not impact survival in younger patients after bioprosthetic MVR, PPM impaired survival in older bioprosthetic recipients. Owing to relatively small numbers of patients in the bioprosthetic PPM subgroup when stratified by age as well as clinical interest in impact of severe PPM on long-term outcome, severe PPM was compared with absent or moderate PPM. For younger bioprosthetic recipients, survival at 5 and 10 years was 58% ± 8% and 48% ± 11% with moderate or less PPM compared with 51% ± 9% and 51% ± 9% with severe PPM (p = 0.26; Fig 7). For older bioprosthetic recipients, survival at 5 and 10 years was 43% ± 4% and 21% ± 4% with absent or moderate PPM compared with only 30% ± 7% and 0% ± 0% with severe PPM (p = 0.05; Fig 8).

Fig 7.

Impact of severe prosthesis–patient mismatch (PPM) on late survival for patients younger than 65 years of age undergoing bio-prosthetic mitral valve replacement. The numbers of patients at risk for each mismatch group are reported.

Fig 8.

Impact of severe prosthesis–patient mismatch (PPM) on late survival for patients 65 years of age and older undergoing bioprosthetic mitral valve replacement. The numbers of patients at risk for each mismatch group are reported.

Comment

Rahimtoola noted that when choosing the appropriate prosthetic heart valve for a specific patient, “. . . one should not compare, or at least be extremely cautious about comparing, outcomes with different [valves], or even the same brand of valve from different studies unless the baseline characteristics of the patients is identical or at least very similar” [20]. This statement rings true when evaluating the impact of PPM during MVR, and although the findings of the current investigation support previously published reports [10–14], close evaluation is essential because these cited series have interpreted similar findings in different ways.

Jamieson and colleagues [14] recently reported their experience with PPM in the mitral position. During a 20-year period, 2,440 patients underwent MVR at the University of British Columbia, including 56% bioprosthetic and 44% mechanical valves. Operative mortality was more than double with bioprosthetic valves (8.6% versus 3.9% mechanical). In contrast to the current report and others in which PPM was more common with bio-prosthetic valves [10–12], the Vancouver group reported a similar incidence of PPM with bioprosthetic and mechanical valves [14]. This may have been attributable, in part, to their using the lower end of published reference EOA values for mechanical valve calculations. Regardless, the current findings are consistent with the report of Jamieson and associates [14] and those of others [11, 12]. Bioprosthetic valves were an independent predictor of late mortality in these series, a finding that is intuitive inasmuch as bioprosthetic recipients are generally older and potentially sicker (lower ejection fraction in the series by Jamieson and colleagues [14]) than their mechanical counterparts. In the current report, bioprosthetic recipients were older than mechanical recipients (68 ± 14 versus 57 ± 13 years; p < 0.001), but there was no difference in ejection fraction (0.48 ± 0.13 versus 0.47 ± 0.14; p < 0.001).

For the entire cohort of 2,440 patients, the Vancouver group identified PPM as a predictor of early, but not late, mortality [14]. However, when they examined only patients with preoperative pulmonary hypertension (40% of the group), late survival was impaired when PPM was present. The current report did not specifically examine the pulmonary hypertension subgroup because this variable was not collected in all patients. However, the findings in the Vancouver group's pulmonary hypertension cohort are consistent with those of the present report, which may have included a “sicker” group of patients overall, as evidenced by a higher incidence of left ventricular dysfunction (21% versus 8% with an ejection fraction of 0.35) and pulmonary hypertension (63% versus 40%) in the current series. The hazard ratio for late mortality was 1.3 (95% CI, 1.1 to 1.6) with moderate-to-severe PPM compared with 1.6 (95% CI, 1.1 to 2.4) for moderate and 1.8 (95% CI, 1.1 to 2.9) for severe PPM in the Vancouver group's pulmonary hypertension cohort.

Tanne and coworkers in Quebec [21] used mathematical modeling to quantify the detrimental impact of elevated mitral prosthetic gradients and PPM on pulmonary hypertension, findings consistent with their earlier clinical report associating persistent pulmonary hyper-tension after MVR with PPM [10]. The incidence of persistent pulmonary hypertension after MVR was 68% with moderate-to-severe PPM, but only 19% when PPM was not present. In the present study, when examining the entire bioprosthetic and mechanical valve cohorts, PPM did not impact survival; it was only after stratification by age that we were able to identify the negative impact of PPM in specific subsets of patients, similar to the series by Jamieson and associates [14] in which PPM only played a role in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Curiously, although the Vancouver group identified PPM as a predictor of late mortality in a specific subset of patients, they speculated that “PPM after MVR is not of clinical relevance.” We believe strongly that when examining entire populations for PPM, there are too many confounding variables at play, and it is only after stratification into select subsets that one is able to “tease out” important subgroup findings relevant to clinical practice.

More consistent with the present investigation, Lam and associates from Ottawa [12] reviewed 884 patients, 74% of whom received mechanical valves, noting a twofold to threefold increase in the incidence of PPM with bioprosthetic versus mechanical valves. The Ottawa group identified age, bioprosthetic implant, and PPM as multivariate predictors of late death with a decline in 10-year survival by 10% when moderate-to-severe PPM was present. Similarly, Magne and coauthors from Quebec [11] reported impaired survival with severe PPM (63% at 12 years) compared with both moderate (76%) and absent (82%) PPM (p = 0.006). In the current series, PPM became an important contributor to late mortality when patients were stratified by age and prosthesis type, augmenting the findings of these previous reports.

The incidence of moderate-to-severe PPM reported in previous studies is quite variable (32% to 85%), depending on the definition of PPM, referenced EOA values, and the implant rate of bioprosthetic versus mechanical valves [10–14]. In the current study, average valve size was 28.6 ± 2.4 mm (29 mm was most common), yielding a 51% incidence of moderate-to-severe PPM overall. The importance of implanting a mitral valve prosthesis of adequate size was reinforced by Li and coauthors [10] who reported a threefold greater increase in the incidence of PPM when prosthesis size was 27 mm or less, regardless of whether a bioprosthetic or mechanical valve was implanted.

Recent decision algorithms based on meta-analyses recommend bioprosthetic versus mechanical valve implantation during MVR based on patient age, risk factors for thromboembolic events (including atrial fibrillation), and long-term bleeding risks [20]. Although methodical in approach, these clinical guidelines do not relay the importance of mitral valve repair or depend on more recent data with an ever-aging patient population. The current report summarizes the clinical work of 20 different surgeons during a 16-year period, and although there has been no specific protocol for selecting prosthesis size during MVR, we believe strongly that the data presented in this study, when combined with those of other units, support a conscious effort in the future to ensure adequate prosthesis size during MVR.

Unlike during aortic valve replacement, annular enlarging procedures are not a viable option [22]. However, there are ways we can optimize prosthesis size for a given annulus. Although valve types with relatively small EOA characteristics may be appropriate when a large prosthesis can be implanted, valves with more favorable EOA characteristics may be preferable when annular size is a limiting factor, for example, in a patient with a calcified, restricted mitral annulus. Although annular size is never a problem with ischemic regurgitation, for rheumatic patients with mitral stenosis, partial posterior leaflet resection with pseudochord placement to maintain papillary-annular continuity may be an option to make room for a bigger prosthesis. In contrast, patients with a heavily calcified, restricted mitral annulus may be at the mercy of valve selection, unless one wishes to embark on a complex annular decalcification procedure. Do we therefore simply select the largest prosthesis size possible to avoid residual gradients? Although this argument has been championed in the past, Bolman [23] reminds us that oversizing the valve can lead to disastrous complications, including disruption of the atrioventricular groove. Clearly, an integrated approach is necessary to minimize PPM during MVR in a safe, yet successful, manner.

Study Limitations

The current series included 795 patients who were operated on by 20 different surgeons during a 16-year period with no standard approach for valve replacement. Diversity in the technical aspects of MVR, patient selection, prosthesis choice for individual patients, continual evolution of available prostheses, and preconceived notions of the impact of PPM during MVR by individual surgeons all contribute to potential biases that could affect the results. Importantly, though, there were no patients excluded, and trends, therefore, likely represent a combination of current practice patterns and a variable approach to patients with mitral valve disease that developed at our institution. The retrospective nature of this evaluation is suspect to all the observer and selection biases inherent in such a study. Multivariate analysis was used in an attempt to minimize bias. Nonetheless, we clearly recognize that such biases can never be strictly avoided. Next, the original intent when performing subgroup analysis independently for the bioprosthetic and mechanical valves was to compare survival with absent versus moderate versus severe PPM for each valve type. Unfortunately, as the number of subgroups grew, the number of patients in each subgroup fell. Despite the reasonable duration of this study (16 years), the numbers of patients out 8 to 10 years was too small to permit a meaningful statistical analysis when PPM was subdivided into three groups. Thus, subgroups were combined only when necessary to permit a meaningful statistical analysis with translational impact. This study cannot account for valve type selected in the respective age cohorts, and absolute survival curves obtained for the mechanical versus bioprosthetic cohort should surely not be ascribed to PPM alone when interpreting these data. Finally, it would have been ideal to calculate PPM using an in vivo EOA assessment for each patient measured postoperatively with Doppler echocardiography. Unfortunately, given the duration of the study, the number of patients involved, and the irregularity in which postoperative echocardiograms were obtained, this was not possible, and we had to settle for previously published reference valves for PPM calculations. Regardless, we feel that our report is in line with Rahimtoola's recommendation that published studies addressing PPM “need a comprehensive, but reasonable, number of important patient characteristics at baseline that should be provided in all [prosthetic heart valve] publications” [20].

Conclusions

In summary, the goal of the analysis performed in the current report was to identify subgroups in which PPM most influenced outcome after MVR. Stratifying patient subgroups on the basis of age and prosthesis type identified an important association between PPM and late mortality after MVR. Specifically, it is important to avoid PPM in all patients during mechanical MVR and in older patients during bioprosthetic MVR to improve long-term survival.

Acknowledgments

Doctor Aziz was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant T32-HL07776. The authors gratefully acknowledge the clinical contributions of Charles B. Huddleston, MD, Sanjiv K. Gandhi, MD, William A. Gay, Jr, MD, James L. Cox, MD, Nader Moazami, MD, Hendrick B. Barner, MD, Thoralf M. Sundt III, MD, Michael Rosenbloom, MD, Thomas L. Spray, MD, T. Bruce Ferguson, Jr, MD, Scott H. Johnson, MD, Eric N. Mendeloff, MD, and Thomas B. Ferguson, Sr, MD.

Biography

DR NEAL D. KON (Winston-Salem, NC): Doctor Aziz, I enjoyed your excellent presentation very much and thank you for bringing this topic to our attention. We don't talk about patient–prosthesis mismatch that often in the mitral position. In a retrospective study of all-comers, you were able to demonstrate some differences in older patients receiving bioprosthetic valves that had mismatch and even showed a trend toward some major differences in younger patients who received a mechanical prosthesis. Patient–prosthesis mismatch is much more extensively studied in the aortic position than the mitral position, because the solutions for solving patient–prosthesis mismatch are clearly simpler in the aortic position. In the aortic position we have got a multitude of options to solve the problems. We can enlarge the LVOT (left ventricular outflow tract) or, better yet, we can use some of the more efficient valve replacement options like a stentless root replacement or a Ross operation.

In contrast, the replacement options in the mitral position for severe prosthesis–patient mismatch may require some very challenging techniques, which entail opening up the fibrous skeleton of the heart and replacing both the aortic and mitral valves. The situation also that comes to mind often clinically is an elderly patient with extensive calcification of the mitral annulus who you know it is going to be a serious problem to try to remove all the calcium and separate the left atrium and left ventricle, but you pick up a 25 sizer and you know there is no chance that that is going to pass through the mitral annulus.

So my questions to you are these. Which patients do you recommend removing all of the calcium from the mitral annulus when it is an elderly patient to try to get a particular prosthesis in place? In which patients is it justified to open the fibrous skeleton of the heart and replace both the aortic and mitral valves? And third, I personally worry about producing patient– prosthesis mismatch in the mitral position mostly in patients with diastolic dysfunction where ventricular filling is already impaired. The severe example of this would be the patient with IHSS (idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis) and SAM (systolic anterior motion) and who also has severe pulmonary hypertension. So, again, what patients would you take extraordinary measures in to prevent patient–prosthesis mismatch in the mitral position?

Thank you very much.

DR AZIZ: Doctor Kon, thank you very much for those comments and questions. This topic and the few solutions available pose difficult problems for many of the reasons which you stated. In particular, it may be prohibitive in the very elderly patient to engage in the sort of calcium debulking procedure which you mention. Picking the largest valve type, which has been recommended by other authors, is often times not the most reasonable approach. In fact, such a solution can lead to a host of other complications, including disruption of the atrioventricular groove.

Your follow-up questions are insightful but rely on specific technical approaches. For this, I will defer to my principal investigator.

DR MARC R. MOON (St. Louis, MO): Debulking annular calcification in almost any patient can be a real disaster, so that we certainly do not recommend for the majority of patients and surgeons. Before we completed this analysis, I would not have predicted that the consequences of patient–prosthesis mismatch would have been so profound in the mitral position. What I have come to appreciate since reviewing these retrospective data is that a lot of surgeons may have been undersizing the prosthesis without understanding the long-term sequelae. A lot of these patients are fairly ill, especially those getting a bioprosthetic valve, so the thought process may have been to simply “get in and get out.” I think we can with careful debridement of the posterior valve itself get an adequate sized valve in most patients with rheumatic stenosis, and we can implant newer valves that have better flow characteristics than the first- and second-generation we had been implanting in earlier years. So, routine annular debridement in an elderly patient probably is not a great idea, except for surgeons who have extensive experience with that complex, potentially dangerous procedure. However, I think that if we select better valve options for those patients, we are probably going to get the result that we want, diminishing mismatch both acutely and long-term.

DR VINOD H. THOURANI (Atlanta, GA): So, Mark, how many of these patients are coming back to you for symptoms and you had to re-replace them?

DR MOON: Almost none, but if you look at lot of the literature that has been written on this topic, patients do have higher pulmonary pressures postoperatively when mismatch is present, and late congestive heart failure is more prevalent—not to the extent that one put them through another mitral valve procedure, but they simply do not do as well in the long run, and so it is probably something we should avoid preemptively if possible.

DR HERMAN A. HECK (Gretna, LA): I think he partially answered the question. Your series seemed to have a lot of second-generation valves and didn't have any pericardial valves in it. I am wondering how this data applies to the third- and fourth-generation valves now, such as the Mosaic valves and the bovine pericardial valves that have a more effective orifice size in this particular situation? Is this data really applicable to those valves?

DR AZIZ: That is a great question. The short answer is likely “no.” In our series, the Hancock valve comprised about 50% of the bioprosthetic cohort. In particular when we get to the third-or fourth-generation valves, you are getting to numbers that are so small that to derive any meaningful information a conglomeration of data from several different institutions would probably be necessary.

DR MOON: One important point to make in that regard is that these data give us the results based on effective orifice area—irrespective of what particular valve had been implanted. So if you have got a newer valve with a better effective orifice area and you have put a small one in, you may still get a similar result. So for our analysis, it did not matter what valve was implanted, only what the ratio was of the effective orifice area to body surface area.

DR KEVIN D. ACCOLA (Orlando, FL): Very interesting discussion, though I was wondering if you had looked at left ventricular ejection fractions and ventricular function. Mitral valvular function is less of a dynamic circumstance and more passive than the aortic valve when considering this concept as intuitively you would think poorer ventricular function patients would not generate as much gradient or contractility. This is an important study, though I think this concept as it relates to the mitral valve has to be considered differently in regards to patient–prosthetic mismatch than with the aortic valve.

DR AZIZ: Thank you. We actually did look at that, and between absent PPM, moderate, and severe, there is no statistical difference in the ejection fraction between the three.

DR KON: Did you look at the diastolic dysfunction, because that is going to be much more important, the diastolic dysfunction than the ejection fraction?

DR ACCOLA: Yes, as that was my point, I agree with Dr Kon. Left ventricular diastolic function has to be considered as the gradient across the valve is not a dynamic process. It would be ill conceived for surgeons to begin dissecting severely calcified annuluses and get into all types of problems while attempting to obtain a larger valve orifice.

DR AZIZ: Your point is well taken. I think with echocardio-graphic assessment that would be a much more amenable indicator to get, but unfortunately we were not able to do that in this series. It's a clear limitation of the study but impossible to obtain given the long duration of the study and incomplete consistency of prospectively obtaining echocardiograms in all of these patients.

DR KON: Can I add just one more thing, because I didn't quite finish. I got your manuscript, which was beautifully written and everything, and I know that this is a retrospective study and everything, but in there it said that you used the package inserts for the EOA (effective orifice area), and that is like asking a used car salesman if the car is in good condition. The EOAs are probably going to be higher. So the other question I wanted to ask you also was when you did your echoes and you looked at what the effective orifice areas were of the valves by echo, did they somewhat match what the package inserts said they were?

DR AZIZ: As a clarification, we relied on published values obtaining our referenced values. Specifically, the values quoted in this manuscript came from several different studies in peer-reviewed surgical and medical literature, all of which we thought were fairly nonbiased.

Footnotes

Presented at the Fifty-sixth Annual Meeting of the Southern Thoracic Surgical Association, Marco Island, FL, Nov 4–7, 2009.

References

- 1.Rahimtoola SH. The problem of valve prosthesis-patient mismatch. Circulation. 1978;58:20–4. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.58.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahimtoola SH, Murphy E. Valve prosthesis–patient mismatch. A long-term sequela. Br Heart J. 1981;45:331–5. doi: 10.1136/hrt.45.3.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao V, Jamieson WRE, Ivanov J, Armstrong S, David TE. Prosthesis-patient mismatch affects survival after aortic valve replacement. Circulation. 2000;102(Suppl 3):III–5–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.suppl_3.iii-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackstone EH, Cosgrove DM, Jamieson WRE, et al. Pros-thesis size and long-term survival after aortic valve replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126:783–96. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(03)00591-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moon MR, Pasque MK, Munfakh NA, et al. Prosthesis-patient mismatch after aortic valve replacement: impact of age and body size on late survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:481–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.07.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dumesnil JG, Pibarot P. Prosthesis-patient mismatch and clinical outcomes. The evidence continues to accumulate. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:952–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moon MR, Lawton JS, Moazami N, Munfakh NA, Pasque MK, Damiano RJ., Jr Point: prosthesis-patient mismatch does not affect survival for patients greater than 70 years of age undergoing bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:278–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yazdanbakhsh AP, van den Brink RBA, Dekker E, de Mol BAJM. Small valve area index. Its influence on early mortality after mitral valve replacement. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2000;17:222–7. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(00)00343-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruel M, Rubens FD, Masters RG, Pipe AL, Bedard P, Mesana TG. Late incidence and predictors of persistent or recurrent heart failure in patients with mitral prosthetic valves. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128:278–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li M, Dumesnil JG, Mathieu P. Pibarot. Impact of valve prosthesis-patient mismatch on pulmonary arterial pressure after mitral valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1034–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.10.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magne J, Mathieu P, Dumesnil JG, et al. Impact of prosthesis-patient mismatch on survival after mitral valve replacement. Circulation. 2007;115:1417–25. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.631549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam BK, Chan V, Hendry P, Ruel M, et al. The impact of patient-prosthesis mismatch on late outcomes after mitral valve replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:1464–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.12.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Totaro P, Argano V. Patient-prosthesis mismatch after mitral valve replacement. Myth or reality? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134:697–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jamieson WR, Germann E, Ye J, et al. Effect of prosthesis-patient mismatch on long-term survival with mitral valve replacement: assessment to 15 years. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:1135–42. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rashtian MY, Stevenson DM, Allen DT, et al. Flow characteristics of bioprosthetic heart valves. Chest. 1990;98:365–75. doi: 10.1378/chest.98.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.David TE, Armstrong S, Sun Z. Clinical and hemodynamic assessment of the Hancock II bioprostheses. Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;54:661–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(92)91008-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fradet GJ, Bleese N, Burgess J, Cartier TC. Mosaic valve international clinical trial: early performance results. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71(Suppl):S273–7. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02539-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rizzoli G, Bottio T, Vida V, et al. Intermediate results of isolated mitral valve replacement with a Biocor porcine valve. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:322–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gudbjartsson T, Absi T, Aranki S. Mitral valve replacement. In: Cohn LH, editor. Cardiac surgery in the adult. 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 2008. pp. 1031–68. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahimtoola SH. Choice of prosthetic heart valve for adult patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:893–904. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02965-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanne D, Kadem L, Rieu R, Pibarot P. Hemodynamic impact of mitral prosthesis-patient mismatch on pulmonary hyper-tension: an in silico study. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1916–26. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90572.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pibarot P, Dumesnil JG. Prosthesis-patient mismatch in the mitral position. Old concept, new evidences. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:1405–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bolman RM., 3rd Survival after mitral valve replacement: does the valve type and/or size make a difference? Circulation. 2007;115:1336–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.686717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]