Abstract

Objective

To review the understanding of the pathogenesis of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) and the role of the immune system in the disease process.

Data Sources

Peer-reviewed articles on EoE from PubMed searching for “Eosinophilic Esophagitis and fibrosis” in the period of 1995 to 2013.

Study Selection

Studies on the clinical and immunologic features, pathogenesis, and management of EoE.

Results

Recent work has revealed that thymic stromal lymphopoietin and basophil have an increased role in the pathogenesis of disease. Additional understanding on the role of fibrosis in EoE is emerging.

Conclusion

The incidence of EoE is increasing like most atopic disease. Similar to other allergic diseases, EoE is treated with topical steroids and/or allergen avoidance.

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune and antigen-mediated clinicopathologic disease that is characterized by eosinophil infiltration into the esophageal epithelium and results in esophageal fibrosis and dysfunction.1 Eosinophilic esophagitis is emerging as an increasingly common cause of esophagitis in children and adults and requires intensive monitoring and treatment to prevent complications, including poor growth, nutritional deficiencies, food impaction, stricture formation, and spontaneous esophageal perforation. The current understanding of the pathobiology of EoE is incomplete but evolving. We searched PubMed for peer-reviewed articles on EoE and selected studies on the clinical and immunologic features, pathogenesis, and management of EoE using the terms “Eosinophilic Esophagitis and fibrosis” from 1995 to 2013. In this article, we briefly review diagnostic and treatment strategies and mechanistic concepts for this rapidly emerging allergic disease.

Clinical Features, Diagnosis, and Management

EoE should be considered in the differential diagnosis for a variety of clinical presentations. In children, EoE is more likely to present with abdominal pain, nausea, emesis, and failure to thrive.1 Adolescents and adults are more likely to present with dysphagia, heartburn, food impaction, and strictures.1 Eosinophilic esophagitis has been estimated to occur in 10% of adults undergoing endoscopy for dysphagia2 with a normal endoscopy results and 12% to 15% of adults who have abnormal endoscopic findings.2,3 This progression of complications toward dysphagia and stricture are attributed to fibrous remodeling associated with the natural history of untreated EoE.4 In fact, the delayed diagnosis of EoE is associated with an increased risk of stricture formation in a time-dependent manner.5 These EoE complications, as well as challenges with the management of EoE, affect patient quality of life and can also result in mental health complications.6,7 Another clinical feature in most EoE patients is the presence of other atopic diseases (asthma, allergic rhinitis, food allergy, and atopic dermatitis), ranging from 40% to 93%, compared with up to 20% in the general population.8

Epidemiology

Eosinophilic esophagitis affects children and adults throughout the world and has been reported in all continents, with recent case reports of isolated cases in South Africa.1 The prevalence of EoE has been previously estimated to range from 10 to 80 per 100,0000 population, with the most recent estimate at 56.7 per 100,000 population9; however, accurate assessment of the incidence and prevalence may be underestimated because International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), codes were only established in 2009. In a recent epidemiologic study in the United States, the estimated prevalence in children is currently 50.5 per 10,000 population, which approaches the prevalence of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease.9

There is a male predominance in EoE, with a male to female ratio of 3:1 in both children and adults.1 Sixty-five percent of the patients in the aforementioned epidemiologic study were male, with a peak of disease activity at 35 to 39 years of age.9 This finding illustrates the increasing incidence of diagnosis in adults, particularly in the third and fourth decades of life.1

Diagnosis and Surveillance

Current consensus diagnostic guidelines for EoE recommend a minimum threshold of 15 eosinophils per high-power field on at least one esophageal biopsy specimen, with eosinophilia limited to the esophagus. Biopsy specimens of both the proximal and distal aspects of the esophagus should be obtained during diagnostic and surveillance endoscopy.1 Common macroscopic endoscopic findings include furrowing, white mucosal plaques, esophageal trachealization, esophageal narrowing, stricture, and mucosal tearing.5 In addition to esophageal eosinophilia, microscopic findings, such as superficial layering and microabscess formation, can be observed.1 Extracellular eosinophil granules, basal cell hyperplasia, dilated intercellular spaces, and lamina propria fibrosis may also be found.10

Before diagnostic and surveillance endoscopy, all patients should be treated with high-dose proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy of 20 to 40 mg twice daily in adults and 1 mg/kg twice per day in children for 8 to 12 weeks1 to exclude gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and other forms of PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia.10 Disease surveillance currently relies on repeated endoscopy because there are no available symptom tools, biomarkers, or pathognomonic elements that can replace clinicopathologic monitoring.1

EoE Management

EoE is known to be a food antigen–driven, chronic allergic disease. There are 2 main, currently accepted clinical treatment strategies for EoE: dietary elimination and corticosteroid treatment.

Dietary Intervention

Most patients with EoE are allergic to food allergens and/or aeroallergens.1 Dietary elimination therapy should be considered in all children diagnosed as having EoE and motivated adults with EoE. Dietary elimination approaches include (1) a strictly elemental diet, (2) specific antigen avoidance based on allergy testing, and (3) empiric food elimination based on the most common food antigens.1 All 3 methods have been proven to be effective with improved clinical symptoms and pathologic findings,11–13 and the regimen chosen should be based on the individual patient.14

Steroid Treatment

Swallowed corticosteroids are effective and can be considered as first-line therapies for initial and maintenance management of EoE based on the patient and physician preference. Swallowed steroids have low bioavailability, have less potential for systemic adverse effects, and are considered to be topical treatments for esophageal inflammation. Fluticasone is administered using a metered-dose inhaler without a spacer. The drug is sprayed into the mouth and swallowed twice daily.15,16 Budesonide is used either in a nebulized form or as an oral viscous slurry.17,18 Overall, swallowed inhaled corticosteroids appear to be safe when used in the short term; however, they increase the risk of local fungal infection.16,18 Systemic steroids are also effective11; however, they are generally reserved for severe cases that do not respond to other therapy because of systemic adverse effects.14,16 Although steroids are effective for treatment, clinical and histologic features of EoE return on discontinued use,1 and it is also unclear whether steroids treat the underlying fibrosis seen in EoE.19

Esophageal Dilation

Esophageal fibrosis and esophageal strictures are known complications of EoE. Endoscopic stricture dilation can be considered for short-term symptomatic relief only if dietary and medical therapy has failed. Importantly, esophageal mucosal fragility is a known feature of EoE,1 increasing the risk of complications, including pain, bleeding, and esophageal perforation.20,21

Molecular Mechanisms of EoE

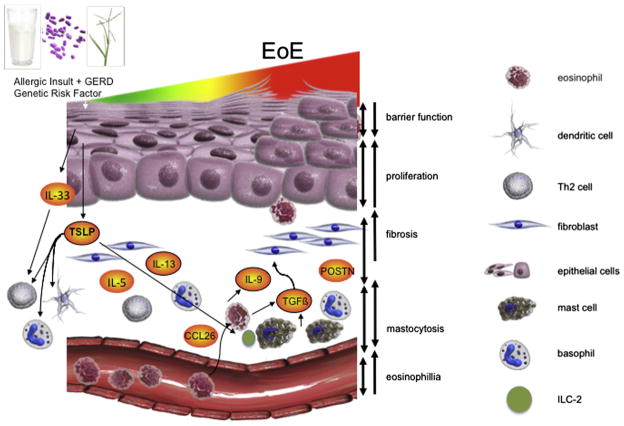

The pathogenesis of EoE originates with genetic risk factors and involves multiple cell types and cytokines. We explore the pathogenesis, beginning at the epithelial layer and progressing to each cell type, and describe their various interactions (Fig 1). Overall, there is a chronic inflammatory infiltrate in EoE, which includes eosinophils, mast cells, basophils, and T cells that produce TH2 cytokines (eg, interleukin [IL] 4 and IL-13) and promote additional inflammation and dysfunction. Similar to other atopic diseases, EoE is triggered by environmental irritants or allergens and food allergens, culminating in esophageal fibrosis or tissue remodeling.22,23 Although clinical evidence points to a true cause-and-effect relationship between food antigen ingestion and EoE-associated inflammation,12,13 it is unknown why the inflammatory infiltration and resulting complications are limited to the esophagus.

Figure 1.

Mechanism of eosinophilic esophagitis pathogenesis. In genetically susceptible individuals, antigens (eg, allergen and infectious agents) and irritants (eg, acid reflux) induce esophageal epithelium to produce thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), interleukin (IL) 33, and eotaxin-3 (CCL-26). Eotaxin 3 (CCL-26) recruits eosinophils to the esophageal epithelium, whereas TSLP and IL-33 lead to dendritic cell and basophil activation and TH2 polarization. This results in TH2 cytokine (eg, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13) secretion and the development of typical TH2 inflammation characterized by eosinophils, mast cells, and T cells. IL-5 further promotes expansion and survival of the recruited eosinophils, which in turn secrete IL-9 and IL-1β. Finally, IL-9 enhances mast cell activation, transforming growth factor β, and tumor necrosis factor α secretion and together with IL-1β induces myofibroblast differentiation and ultimately fibrosis.

Genetic Risk Factors

Similar to other atopic diseases, EoE is linked to a strong genetic element. In collaboration with the Center for Applied Genomics at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, we recently found an association between a single nuclear polymorphism (SNP) in the gene encoding thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and risk for EoE.24 TSLP is an IL-7–like cytokine that regulates host adaptive immune responses through dendritic cell and T-cell interactions. We identified SNP rs3806932, which involves the nucleotides A/G and is present in the promoter region of the TSLP gene. The protective minor allele (G) is present in a higher percentage of controls (45.8%) compared with EoE patients (31.2%). Individuals homozygous for the TSLP risk allele (AA) have increased TSLP expression and basophil infiltration in the esophageal epithelium compared with those carrying heterozygous (AG) risk allele and homozygous (GG) protective minor alleles.24,25 Sherrill et al26 also identified a significant association between an SNP in the TSLP receptor and male EoE patients. The TSLP receptor is on the Yp11.3 chromosome, which may explain some of the male predominance in EoE. Recent work from the Rothenberg laboratory identified a subset of patients with EoE and inherited connective tissue disorders, suggesting additional potential genes involved in EoE.27

A third identified risk factor linked to EoE is a polymorphism in eotaxin-3 (CCL-26). Eotaxin-3 (CCL-26) is a potent eosinophil chemoattractant that signals through CCR3, a chemokine receptor expressed by activated eosinophils and mast cells. It is the most dysregulated gene in EoE patients and is elevated in the esophageal epithelium and peripheral blood during active inflammation.28

Lack of Role for IgE in EoE

Murine models of EoE have found that EoE-like disease can develop independently of IgE because IgE-depleted mice develop food bolus impactions and EoE equivalent to wild-type mice.25 Although IgE-mediated food allergies are common (range, 10%-20%) in EoE, one small pilot study of 2 patients found that anti-IgE therapy had no effect on EoE.29 In addition, 5% to 10% of patients treated with oral immunotherapy for desensitization to IgE-mediated food allergy develop EoE, indicating a non-IgE mechanism.30 Finally, testing for IgE-mediated food allergy by skin prick testing or specific sera IgE has not proven successful in definitive identification of causative foods in EoE.1,12,31 However, a study by Erwin et al32 found that more foods were identified by serum IgE than skin test or atopy patch testing, but this study did not determine whether these foods were causing disease. Rather, the addition of atopy patch testing, which represents a T-lymphocyte–mediated allergen specific response, increases the likelihood of identifying causative foods in EoE12 and suggests that EoE is mixed IgE and non–IgE-mediated or non–IgE-mediated disease.

Esophageal Epithelium and Barrier Dysfunction

It has previously been suggested that EoE patients have altered epithelial barrier dysfunction. Indeed, both gene expression profiling28 and immunolocalization studies29 have demonstrated a down-regulation in the expression of the cell adhesion protein DSG-1 in the esophageal epithelium in actively inflamed EoE, which partially normalizes after clinical treatment. Using in vitro models, Sherrill et al29 found that in the absence of DSG-1, the stratified squamous esophageal epithelium had impaired barrier function and underwent epithelial cell separation. They speculated that the functional ramifications of this finding include enhanced permeability of the epithelium to local food and environmental allergens, leading to increased access to antigens by local esophageal antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as Langerhans cells.30

The esophageal epithelium is more than a physical barrier. We and others have found that human esophageal epithelial cells express Toll-like receptors33,34 and produce proinflammatory cytokines in response to both pathogen-associated molecular patterns and danger-associated molecular patterns.33 We have also demonstrated that EoE-derived epithelial cells can produce the eosinophilic and T-cell chemokine RANTES (CCL5),35 which may play a role in the migration and activation of IL-13–producing invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells in EoE. In addition, others have found that esophageal epithelial cells may also function as nonprofessional APCs. Mulder et al36 demonstrated that the human esophageal epithelial cell line (HET-1A) can internalize and process chicken egg ovalbumin and can activate T cells on antigen priming.

Antigen-Presenting Cells

In addition to a potential role of esophageal epithelial cells as local nonprofessional APCs, a more commonly accepted notion is that professional APCs may play a more prominent role in the adaptive immune response in EoE. Langerhans cells are present in the esophageal epithelium, although the density of Langerhans cells is not greater in EoE compared with non-EoE populations.37 The currently accepted hypothesis of immune responses in EoE is that antigens, perhaps via contact through a dysfunctional esophageal epithelial barrier, are taken up by professional APCs, which in turn promote the polarization of TH2-type T cells (Fig 1). The epithelial cytokine TSLP, which functions at the interface of dendritic cell and T-cell responses,25,38 may be of key importance in this regard. However, clinical observations have revealed that patients receiving enteral nutrition via postpyloric feeding tubes can develop EoE, suggesting that direct contact between food antigens and the esophageal epithelium is not a requirement for disease pathogenesis.

Cytokines and Chemokines

Cytokines and chemokines play an essential role in the inflammation associated with EoE, resulting in increased TH2 response, eosinophil survival, and fibrotic changes (Table 1). Many cytokines have multiple roles in EoE. For example, IL-4 promotes TH2-lymphocyte survival, eosinophil migration via induction of eotaxin-3 (CCL-26), and profibrotic changes by inducing periostin, collagen, and β-actin. There are likely redundancies in cytokine function because anti–IL-5 leads to only partial reduction of esophageal eosinophilia in human trials.39,40 Two key cytokines and chemokines, eotaxin-3 (CCL-26) and TSLP, are discussed further.

Table 1.

Cytokines and chemokines involved in EoE pathogenesis

| Cytokine or chemokine | Increase in serum | Increase in esophageal epithelial biopsy specimen | Potential role in EoE | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | + | Fibrosis | 46,60 | |

| IL-4 | + | + | Results in TH2 cell differentiation | 49,56 |

| Induces fibrosis | ||||

| IL-5 | + | + | Eosinophil migration and survival | 35,46 |

| IL-6 | + | Unknown | 46 | |

| IL-9 | + | Migration, activation, and maturation of mast cells | 61 | |

| IL-13 | + | + | TH2 inflammation | 35,42,46,56 |

| Induces fibrosis | ||||

| Down-regulates filaggrin | ||||

| Induces secretion of eotaxin-3 from epithelial cells | ||||

| IL-15 | + | + | Activates differentiation and proliferation of T cells | 62 |

| Activates natural killer cells | ||||

| IL-33 | + | Stimulates TH2 cell differentiation | 63 | |

| Activated on tissue injury | ||||

| TGF-β | + | Fibrosis | 13,56,60 | |

| Myofibroblast differentiation | ||||

| TSLP | + | Dendritic cell activation and TH2 cell differentiation | 22,23,37,41 | |

| Induced basophil production | ||||

| Activated on tissue injury | ||||

| Necessary in murine models | ||||

| Eotaxin-3 (CCL-26) | + | + | Eosinophil chemoattractant | 25,46 |

| RANTES | + | + | Eosinophil chemotaxis and activation | 35 |

| T-cell chemoattractant | ||||

| TNF-α | + | Epithelial to mesenchymal transition, resulting in fibrosis | 60 |

Abbreviations: EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; IL, interleukin; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α; TSLP, thymic stromal lymphopoietin.

Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin

TSLP is an IL-7–like cytokine that is a master regulator of TH2-type allergic inflammation. It is primarily secreted by cells of nonhematopoetic lineage, such as epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and smooth muscle cells, in response to atopic cytokines (IL-4, IL-13, and tumor necrosis factor α) and environmental allergens. TSLP is increased in the esophageal biopsy specimens of EoE patients compared with those without EoE24,25,38 and is overexpressed within epithelial barriers, including the epidermis in atopic dermatitis.41,42 As previously discussed, polymorphisms in TSLP are linked to EoE, and deletion of TSLP in a murine model of EoE completely eliminates EoE. In EoE, expression of TSLP may be induced by tissue injury or stimulation of the esophageal epithelium, starting the TH2 cascade. TSLP promotes the maturation and activation of dendritic cells, which then secrete factors involved in migration and differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into TH2 cells 42 (Fig 1). This culminates in the production of cytokines, including CCL-26, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, and results in EoE inflammation. TSLP also leads to induction of innate lymphoid cells (IL-2), which lead to expression of IL-9–promoting mast cells, which may express profibrotic cytokines. TSLP also induces a unique basophil population in EoE, which secrete pro-TH2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-6, CCL-3, CCL-4, and CCL-12), leading to increased inflammation.38 Noti et al25 recently described a novel mouse model of EoE in which the development of EoE-like features was dependent on both TSLP and basophils. Neutralizing antibodies against TSLP and basophils helped in ameliorating EoE-like disease when administered after the onset of disease. This finding may suggest that targeting the TSLP-basophil axis may lead to potential therapeutic treatments for EoE.

Eotaxin-3 (CCL-26)

Eotaxin-3 (CCL-26) is a potent eosinophil chemoattractant that signals through CCR3, a chemokine receptor expressed by activated eosinophils and mast cells. It is the most dysregulated gene in EoE patients and is elevated in the esophageal epithelium and peripheral blood during active inflammation.28 In vitro, esophageal epithelial cells secrete eotaxin-3 (CCL-26) in response to IL-4 and IL-13 stimulation.43 However, this effect is not unique to EoE. Epithelial cells from healthy individuals and patients with GERD also express eotaxin-3 (CCL-26) in response to TH2 cytokine stimulation as in EoE.44 Interestingly, eotaxin-3 (CCL-26) expression can be suppressed by the PPI omeprazole in the cells.44 This in vitro observation suggests that PPI therapy may play a role in reducing tissue eosinophilia through mechanisms independent of acid suppression alone. Therefore, eotaxin-3 (CCL-26) plays a key role in the migration of eosinophils to the esophageal tissue.

Circulating Effector Cells in EoE

Eosinophils

Intraepithelial eosinophils are the histologic hallmark of EoE and are used as a standard marker for diagnosis and disease activity. IL-5, secreted by a variety of cell types, including T cells, basophils, and mast cells, is essential for eosinophil differentiation, proliferation, and survival (Table 2). A recent transgenic mouse model of EoE in which esophageal epithelial cells overexpress IL-5 is the first murine model to exhibit marked intraepithelial eosinophilia, in contrast with other murine models in which eosinophil infiltration is limited primarily to the subepithelial compartment.45 Activation of tissue eosinophils results in degranulation or release of granular proteins and secretion of inflammatory cytokines, including transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-13, major basic protein, eosinophilic cationic protein, eosinophilic peroxidase, and eosinophilic-derived neurotoxin.46 These granular proteins cause additional tissue damage, leading to increased epithelial dysfunction as discussed above.

Table 2.

Circulating effector cells in EoE

| Cell type | Role | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Basophil | Secrete IL-4 | 25 |

| Eosinophil | Secrete eosinophil cationic proteins, leading to tissue damage | 46 |

| iNKT cells | Secrete IL-13 | 35 |

| Stimulate TH2 cells | ||

| Mast cells | Secrete TGF-β, leading to fibrosis | 50,51 |

| Secrete tryptase, leading to fibrosis | ||

| T cell (TH2 and regulatory T cells) | Secrete TH2 cytokines | 47,48 |

| Decrease IL-10 | ||

| Activation of basophils, eosinophils, and mast cells |

Abbreviations: EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; IL, interleukin; iNKT, invariant natural killer T; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β.

In clinical trials, 2 humanized monoclonal antibodies against IL-5 (mepolizumab and reslizumab) reduced peripheral and partially reduced esophageal eosinophilia in EoE patients but did not significantly affect clinical symptoms.39,40 Notably, IL-5 is important for the production and early growth of eosinophils, but mature eosinophils lose IL-5 receptors and are more dependent on IL-3 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Therefore, there is probable redundancy in pathways because many tissue eosinophils survived despite loss of IL-5. Together, the results of these clinical studies suggest that although eosinophils are a hallmark of EoE, the pathogenesis of EoE is also dependent on other immune pathways and cell types.

TH2 Lymphocytes

After eosinophils, intraepithelial T lymphocytes are the most prominent infiltrating cell type in EoE. It is well established that EoE, like other atopic diseases, is a TH2-driven disease and that EoE patients have activated TH2 cells secreting IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 in both the peripheral blood and active esophageal biopsies.20,44 In addition, evidence from murine models reveal the importance of T cells in EoE because mice deficient in T cells do not develop EoE.45

Regulatory T Cells

In addition to TH2 cells, an increased presence of regulatory T cells has been reported in the esophageal epithelium of EoE patients compared with GERD patients and healthy controls.47,48 However, the levels of regulatory T cell–derived anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 were decreased in EoE patients. This paradox suggests an altered immune tolerance mechanism in EoE, and additional studies are needed to explore the role of T regulatory cells in EoE.

Invariant Natural Killer T Cells

Food antigen exposure is strongly associated with EoE, and a number of clinical studies have examined causative foods in EoE.1 However, the underlying cellular and immunologic effects mediated by food antigens in EoE remain largely unknown. We recently found that iNKT cells, which are specialized in their ability to recognize self- and foreign lipids,35 may provide a functional link between cow milk allergy with EoE. Children with active EoE had higher numbers of iNKT cells in the esophagus compared with children with inactive EoE and healthy controls. iNKT cells from EoE patients produced higher levels of IL-13 in response to milk sphingolipid stimulation when compared with non-EoE controls. Within the EoE cohort, iNKT cells from active EoE patients had significantly higher IL-13 expression compared with those from inactive individuals. These observations suggest that iNKT cells migrating to the esophageal epithelium during active inflammation in EoE could be a potential source of IL-13.

Mast Cells

Mast cells are widely associated with both IgE-mediated and non–IgE-mediated allergic responses, and their contribution to EoE has recently been recognized. The presence of activated mast cells and mast cell products is reported in the esophageal epithelium in biopsy specimens from active EoE patients.49,50 Corticosteroid treatment for EoE decreases esophageal epithelial mast cell numbers and correlates with decreased tissue eosinophilia.50 Mast cells secrete TGF-β, which is a proinflammatory cytokine that promotes smooth muscle contractility in EoE.50 In addition, mast cell tryptase promotes proliferation and collagen secretion from renal fibroblasts, an observation that may have implications for fibrosis in EoE.51 The effect of mast cell–derived factors on epithelial function is unknown.

Basophils

Basophils are the least common granulocytes, constituting less than 1% of the leukocyte population. Basophils have long been associated with type 1 allergic responses secondary to the surface expression of high-affinity receptor for IgE, FcεRI, and their ability to secrete histamine. Studies have expanded our understanding of basophil function, particularly with regard to their potential role in non–IgE-mediated allergic conditions, such as EoE. Siracusa et al38 identified a unique subpopulation of basophils that developed in the presence of TSLP, which is overexpressed in allergic disorders, including EoE. This basophil population was functionally distinct from the IL-3–elicited basophil population and secreted increased concentrations of IL-4. Critically, basophils isolated from EoE patients exhibited similarities to in vitro TSLP-elicited basophils. Additional studies have found that the TSLP-basophil axis is essential for the development of an EoE-like disorder in mice.25 Together, these studies indicate that TSLP-mediated basophil response might play an important role in the pathogenesis of EoE in humans.

EoE appears to be a mostly non–IgE-mediated disease but dependent on T cells. We speculate that epithelial APCs interacting with T cells prime the system toward a TH2 response. This interaction along with signals from the epithelial layer, including TSLP and IL-33, interact with basophils and mast cells to induce eosinophils and additional growth of TH2 cells, leading toward the eosinophilic infiltrate seen in EoE.

Fibrosis in EoE

The incidence of esophageal food bolus impaction has increased notably in the last 5 to 10 years,52 in parallel with the increased incidence of EoE. EoE is currently the leading cause of emergency endoscopy for esophageal food impaction in adults.53 In a large population-based study based on ICD-9 coding, 55.8% of EoE patients reported dysphagia and 12.5% had a history of food impaction.9 Clinical symptoms of fibrosis range from signs of progressive solid food dysphagia (excessive chewing and drinking with meals) to subtle changes in eating habits (meat avoidance) to frequent episodes of food impaction. This underscores the importance of obtaining a thorough and targeted history in both established EoE patients and all new patients presenting with food allergy, atopy, and GERD-like symptoms.

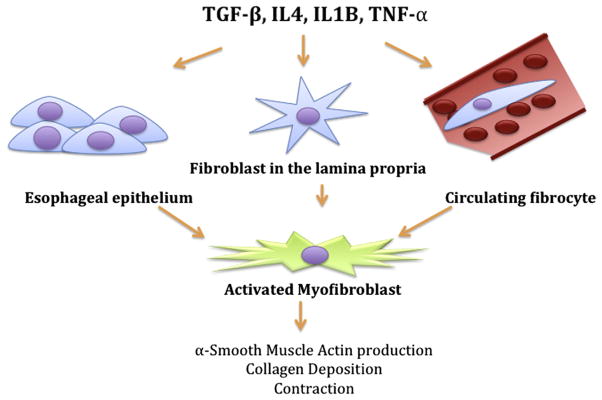

Fibrosis is defined as excess deposition of components of the extracellular matrix, leading to organ dysfunction. Little is currently known about the pathophysiology of fibrosis in EoE, and the current understanding of EoE-associated fibrosis has been extrapolated from in vitro assays and models from other organ systems. Regardless of the organ system, the key effector cell in all models of fibrosis is the activated myofibroblast, a unique cell type that exhibits properties of both smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts (Fig 2). It is hypothesized that the myofibroblast contracts and places tension on the extracellular matrix, resulting in activation and differentiation of neighboring cells. Once contracted, the myofibroblast secretes extracellular matrix components, including type 1 collagen, to stabilize its new, contracted position.54

Figure 2.

Origin and function of the activated myofibroblast. Profibrotic cytokines, such as transforming growth factor β, tumor necrosis factor α, and interleukin 1, secreted in the setting of chronic inflammation activate epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and circulating fibrocytes and induce their transdifferentiation to a myofibroblast phenotype. These activated myofibroblasts contribute to the development of esophageal fibrosis because they produce α-smooth muscle actin, secrete collagen, and contract.

The prototypical cytokine TGF-β, which stimulates myofibroblast differentiation, is released by local cells, including fibroblasts, epithelial cells, and infiltrating inflammatory cells. TGF-β targets members of the SMAD family of transcription factors, resulting in expression of various genes responsible for the fibroblast phenotype, including α-smooth muscle actin and collagen. TGF-β has been localized to the esophageal lamina propria in patients with EoE55 and correlates with increased nuclear phosphorylated SMAD staining in biopsy specimens from EoE patients compared with non-EoE controls.56 Other factors involved in fibrosis, such as subepithelial fibronectin, have been reported to be increased in murine models of ovalbumin-induced EoE models.57–59 However, in humans, only subepithelial collagen deposition has been observed to date in EoE.

We and others have found that esophageal epithelial cells can undergo transdifferentiation to a myofibroblast phenotype through epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition is a process by which epithelial cells lose epithelial markers (eg, E-cadherin) and gain contractile properties of myofibroblasts, marked by increased expression of α-smooth muscle actin.57,60 In vitro studies have found that profibrotic cytokines, including TGF-β, TNF-α, and IL-1β, may play a key role in this process.57,60 However, the occurrence of epithelial to mesenchymal transition in vivo remains a highly controversial notion that requires rigorous cell lineage studies.

Conclusion

The incidence of EoE is increasing like most atopic disease. Similar to other allergic diseases, EoE is treated with topical steroids and/or allergen avoidance. From a mechanistic viewpoint, EoE is a classic allergen-driven atopic disease, although in the absence of a strong IgE-mediated signal. In a genetically susceptible individual, an allergen (typically a food in EoE) initiates the disease process through a dysfunctional epithelial barrier (Fig 1). The disrupted barrier, with increased expression of TSLP, induces TH2 cells and unique basophils. TH2 cells and basophils then secrete cytokines and chemokines, leading to the migration of eosinophils. Eosinophils secrete cytokines and molecules that further disrupt the esophageal layer, leading to tissue damage, esophageal dysmotility, and profibrotic factors and resulting in the symptoms and complications of EoE (Fig 2).

Footnotes

Disclosures: Authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prasad GA, Talley NJ, Romero Y, et al. Prevalence and predictive factors of eosinophilic esophagitis in patients presenting with dysphagia: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2627–2632. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackenzie SH, Go M, Chadwick B, et al. Eosinophilic oesophagitis in patients presenting with dysphagia: a prospective analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:1140–1146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aceves SS, Ackerman SJ. Relationships between eosinophilic inflammation, tissue remodeling, and fibrosis in eosinophilic esophagitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2009;29:197–211. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schoepfer AM, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, et al. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1230–1236. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris RF, Menard-Katcher C, Atkins D, Furuta GT, Klinnert MD. Psychosocial dysfunction in children and adolescents with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57:500–505. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31829ce5ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franciosi JP, Hommel KA, Debrosse CW, et al. Quality of life in paediatric eosinophilic oesophagitis: what is important to patients? Child Care Health Dev. 2012;38:477–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jyonouchi S, Brown-Whitehorn TA, Spergel JM. Association of eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders with other atopic disorders. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2009;29:85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dellon ES, Jensen ET, Martin CF, Shaheen NJ, Kappelman MD. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.008. published online September 11, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Shah A, Kagalwalla AF, Gonsalves N, Melin-Aldana H, Li BU, Hirano I. Histopathologic variability in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:716–721. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liacouras CA, Spergel JM, Ruchelli E, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a 10-year experience in 381 children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1198–1206. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00885-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Cianferoni A, et al. Identification of causative foods in children with eosinophilic esophagitis treated with an elimination diet. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kagalwalla AF, Sentongo TA, Ritz S, et al. Effect of six-food elimination diet on clinical and histologic outcomes in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1097–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, et al. ACG clinical guideline: evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:679–692. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konikoff MR, Noel RJ, Blanchard C, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluticasone propionate for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1381–1391. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaefer ET, Fitzgerald JF, Molleston JP, et al. Comparison of oral prednisone and topical fluticasone in the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis: a randomized trial in children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dohil R, Newbury R, Fox L, Bastian J, Aceves S. Oral viscous budesonide is effective in children with eosinophilic esophagitis in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:418–429. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, et al. Budesonide is effective in adolescent and adult patients with active eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1526–1537. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lucendo AJ, Arias A, De Rezende LC, et al. Subepithelial collagen deposition, profibrogenic cytokine gene expression, and changes after prolonged fluticasone propionate treatment in adult eosinophilic esophagitis: a prospective study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1037–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucendo AJ, Friginal-Ruiz AB, Rodriguez B. Boerhaave’s syndrome as the primary manifestation of adult eosinophilic esophagitis: two case reports and a review of the literature. Dis Esophagus. 2011;24:E11–E15. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2010.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nantes O, Jimenez FJ, Zozaya JM, Vila JJ. Increased risk of esophageal perforation in eosinophilic esophagitis. Endoscopy. 2009;41(suppl 2):E177–E178. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson DS, Hamid Q, Jacobson M, Ying S, Kay AB, Durham SR. Evidence for Th2-type T helper cell control of allergic disease in vivo. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1993;15:17–27. doi: 10.1007/BF00204623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1483–1494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra074081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rothenberg ME, Spergel JM, Sherrill JD, et al. Common variants at 5q22 associate with pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat Genet. 2010;42:289–291. doi: 10.1038/ng.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noti M, Wojno ED, Kim BS, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin-elicited basophil responses promote eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat Med. 2013;19:1005–1013. doi: 10.1038/nm.3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sherrill JD, Gao PS, Stucke EM, et al. Variants of thymic stromal lymphopoietin and its receptor associate with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abonia JP, Wen T, Stucke EM, et al. High prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with inherited connective tissue disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:378–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blanchard C, Wang N, Stringer KF, et al. Eotaxin-3 and a uniquely conserved gene-expression profile in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:536–547. doi: 10.1172/JCI26679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rocha R, Vitor AB, Trindade E, et al. Omalizumab in the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis and food allergy. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170:1471–1474. doi: 10.1007/s00431-011-1540-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ridolo E, De Angelis GL, Dall’aglio P. Eosinophilic esophagitis after specific oral tolerance induction for egg protein. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011;106:73–74. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonsalves N, Yang GY, Doerfler B, Ritz S, Ditto AM, Hirano I. Elimination diet effectively treats eosinophilic esophagitis in adults; food reintroduction identifies causative factors. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1451–1459. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erwin EA, James HR, Gutekunst HM, Russo JM, Kelleher KJ, Platts-Mills TA. Serum IgE measurement and detection of food allergy in pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;104:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lim DM, Narasimhan S, Michaylira CZ, Wang ML. TLR3-mediated NF-κB signaling in human esophageal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297:G1172–G1180. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00065.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mulder DJ, Lobo D, Mak N, Justinich CJ. Expression of toll-like receptors 2 and 3 on esophageal epithelial cell lines and on eosinophils during esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:630–642. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1907-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jyonouchi S, Smith CL, Saretta F, et al. Invariant natural killer T cells in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44:58–68. doi: 10.1111/cea.12201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mulder DJ, Pooni A, Mak N, Hurlbut DJ, Basta S, Justinich CJ. Antigen presentation and MHC class II expression by human esophageal epithelial cells: role in eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:744–753. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yen EH, Hornick JL, Dehlink E, et al. Comparative analysis of FcepsilonRI expression patterns in patients with eosinophilic and reflux esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:584–592. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181de7685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siracusa MC, Saenz SA, Hill DA, et al. TSLP promotes interleukin-3-independent basophil haematopoiesis and type 2 inflammation. Nature. 2011;477:229–233. doi: 10.1038/nature10329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spergel JM, Rothenberg ME, Collins MH, et al. Reslizumab in children and adolescents with eosinophilic esophagitis: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:456–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Assa’ad AH, Gupta SK, Collins MH, et al. An antibody against IL-5 reduces numbers of esophageal intraepithelial eosinophils in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1593–1604. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li M, Hener P, Zhang Z, Ganti KP, Metzger D, Chambon P. Induction of thymic stromal lymphopoietin expression in keratinocytes is necessary for generating an atopic dermatitis upon application of the active vitamin D3 analogue MC903 on mouse skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:498–502. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soumelis V, Reche PA, Kanzler H, et al. Human epithelial cells trigger dendritic cell mediated allergic inflammation by producing TSLP. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:673–680. doi: 10.1038/ni805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blanchard C, Stucke EM, Burwinkel K, et al. Coordinate interaction between IL-13 and epithelial differentiation cluster genes in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Immunol. 2010;184:4033–4041. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng E, Zhang X, Huo X, et al. Omeprazole blocks eotaxin-3 expression by oesophageal squamous cells from patients with eosinophilic oesophagitis and GORD. Gut. 2013;62:824–832. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Masterson JC, McNamee EN, Hosford L, et al. Local hypersensitivity reaction in transgenic mice with squamous epithelial IL-5 overexpression provides a novel model of eosinophilic oesophagitis. Gut. 2014;63:43–53. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Straumann A, Simon HU. The physiological and pathophysiological roles of eosinophils in the gastrointestinal tract. Allergy. 2004;59:15–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1398-9995.2003.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tantibhaedhyangkul U, Tatevian N, Gilger MA, Major AM, Davis CM. Increased esophageal regulatory T cells and eosinophil characteristics in children with eosinophilic esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2009;39:99–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fuentebella J, Patel A, Nguyen T, et al. Increased number of regulatory T cells in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:283–289. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181e0817b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dellon ES, Chen X, Miller CR, et al. Tryptase staining of mast cells may differentiate eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:264–271. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aceves SS, Chen D, Newbury RO, Dohil R, Bastian JF, Broide DH. Mast cells infiltrate the esophageal smooth muscle in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, express TGF-beta1, and increase esophageal smooth muscle contraction. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:1198–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kondo S, Kagami S, Kido H, Strutz F, Muller GA, Kuroda Y. Role of mast cell tryptase in renal interstitial fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:1668–1676. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1281668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crockett SD, Sperry SL, Miller CB, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Emergency care of esophageal foreign body impactions: timing, treatment modalities, and resource utilization. Dis Esophagus. 2013;26:105–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2012.01344.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Desai TK, Stecevic V, Chang CH, Goldstein NS, Badizadegan K, Furuta GT. Association of eosinophilic inflammation with esophageal food impaction in adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:795–801. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Hinz B, Chaponnier C, Brown RA. Myofibroblasts and mechanoregulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:349–363. doi: 10.1038/nrm809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Chen D, et al. Resolution of remodeling in eosinophilic esophagitis correlates with epithelial response to topical corticosteroids. Allergy. 2010;65:109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Dohil R, Bastian JF, Broide DH. Esophageal remodeling in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kagalwalla AF, Akhtar N, Woodruff SA, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: epithelial mesenchymal transition contributes to esophageal remodeling and reverses with treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1387–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cho JY, Rosenthal P, Miller M, et al. Targeting AMCase reduces esophageal eosinophilic inflammation and remodeling in a mouse model of egg induced eosinophilic esophagitis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;18:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rubinstein E, Cho JY, Rosenthal P, et al. Siglec-F inhibition reduces esophageal eosinophilia and angiogenesis in a mouse model of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:409–416. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182182ff8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Muir AB, Lim DM, Benitez AJ, et al. Esophageal epithelial and mesenchymal cross-talk leads to features of epithelial to mesenchymal transition in vitro. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319:850–859. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Otani IM, Anilkumar AA, Newbury RO, et al. Anti-IL-5 therapy reduces mast cell and IL-9 cell numbers in pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1576–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhu X, Wang M, Mavi P, et al. Interleukin-15 expression is increased in human eosinophilic esophagitis and mediates pathogenesis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:182–193. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bouffi C, Rochman M, Zust CB, et al. IL-33 markedly activates murine eosinophils by an NF-kappaB-dependent mechanism differentially dependent upon an IL-4-driven autoinflammatory loop. J Immunol. 2013;191:4317–4325. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]