Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are known to have many notable features, especially their multiple differentiation ability and immunoregulatory capacity. MSCs are important stem cells in the bone marrow (BM), and their characteristics are affected by the BM microenvironment. However, effects of the BM microenvironment on the properties of MSCs are not well understood. In this study, we found that BM from aged mice decreased MSC colony formation. Flow cytometry data showed that the proportion of B220+ cells in BM from aged mice was significantly lower than that in BM from young mice, while the proportion of CD11b+, CD3+, Gr-1+, or F4/80+ cells are on the contrary. CD11b+, B220+, and Ter119+ cells from aged mice were not the subsets that decreased MSC colony formation. We further demonstrated that both BM from aged mice and young mice exhibited similar effects on the proliferation of murine MSC cell line C3H10T1/2. However, when cocultured with BM from aged mice, C3H10T1/2 showed slower migration ability. In addition, we found that phosphorylation of JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinases) in C3H10T1/2 cocultured with BM from aged mice was lower than that in C3H10T1/2 cocultured with BM from young mice. Collectively, our data revealed that BM from aged mice could decrease the migration of MSCs from their niche through regulating the JNK pathway.

Keywords: Aged, Mesenchymal stem cells, Bone marrow microenvironment, Migration

Introduction

The bone marrow (BM) microenvironment is a complex environment constituted by stromal cells, the extracellular matrix, and a variety of soluble cytokines (Dazzi et al. 2006), which provides the foundation for stem cell survival. Particularly, there are two important types of stem cells: hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) with the potential of both self-renewal and multiple differentiations (Prockop 1997; Bruder et al. 1997). The degeneration and functional decline of cells, tissues, and organs that accompany aging are unavoidable. With the aging of the body, the BM microenvironment and HSCs and MSCs within the microenvironment are also senescent. However, most current studies focus on the relationship between HSCs and the BM microenvironment; thus, the BM microenvironment and HSC microenvironment are synonymous. Many studies have focused on the effect of the microenvironment on HSC aging and indicated that HSCs from older mice have a significantly lower cycling activity and a reduced lymphoid differentiation potential than those isolated from young mice (de Haan et al. 1997; Li et al. 2001; Donnini et al. 2007; Zhu et al. 2007). Additionally, in the BM microenvironment, aged BM progenitors produce greater numbers of myeloid than lymphoid lineage cells as compared to young BM progenitors (Morrison et al. 1996; Sudo et al. 2000; Waterstrat and Van Zant 2009; Zediak et al. 2007). Min et al. found that the number of common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs), pro-B cells, and pre-B cells in BM from aged mice was significantly less than that in BM from young mice (Min et al. 2006). However, the number of Gr1+/CD11b+ cells in BM from aged mice is higher than that in BM from young mice (Shao et al. 2011). These studies indicate that aging is associated with intrinsic HSC changes as well as changes in the microenvironment.

MSCs are another important type of stem cell in the BM microenvironment. They can differentiate into osteoblasts, which help to regulate the hematopoietic stem cell niche (Calvi et al. 2003). It follows that the MSC physical environment should be essentially identical with that of HSCs (Chen et al. 2012; Li et al. 2011). In addition, MSCs have the ability to self-renew and differentiate into multiple lineages, including osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic (Prockop 1997; Bruder et al. 1997). Their relative ease of isolation from many tissues and rapid expansion in culture, coupled with their contribution to organ regeneration and overcoming certain diseases (D’Agostino et al. 2010; Mazzini et al. 2010; Loebinger et al. 2009), have made these cells an excellent candidate for a variety of research and therapeutic applications. Despite this, there are few studies regarding the effects of the BM microenvironment on MSC proliferation and migration. As we know, MSCs can migrate toward the region of tissue injury, partly due to the expressed chemokine receptors responding to high levels of chemokines at the site of tissue damage (Chen et al. 2011). Then, will the microenvironment affect the mobilization of MSCs to migrate out of their niche? Which factors in BM from aged mice will restrain MSCs from migrating out from their niche? Whether these changes of the BM subset will affect mobilization of MSCs is still uncovered. Thus, in our study, we investigated the effect of BM from aged mice on the proliferation and migration of MSCs from their niche.

Materials and methods

Animals

Healthy young (3 ~ 4 weeks) and aged (8 ~ 18 months) C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Center of the Academy of Military Medical Sciences of China (Beijing). Both female and male mice were included. All experiments were performed in accordance with the Academy of Military Medical Sciences Guide for Laboratory Animals.

Young and aged BM cocultured with bone fragments

Approximately three to 4 weeks (young) and 8 ~ 18 months (aged) C57BL/6 mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation. Femurs and tibiae were carefully cleaned of adherent soft tissue, the epiphyses were removed using micro-dissecting scissors, and the marrow (BMY, BM from young mice; BMA, BM from aged mice) was harvested by inserting a syringe needle (0.45 mm) into the bone marrow cavity and flushing with phosphate-buffered solution (PBS). The marrow was then homogenized and red blood cell lysis buffer (BD, Franklin L, NJ) added for 6 min, the cells then centrifuged for 10 min at 300 g and suspended in alpha-modified minimal essential medium (α-MEM; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) containing 10 % (vol/vol) lot-selected fetal bovine serum (FBS; ExCell Bio Shanghai, CHN) before seeding the marrow cell into a six-well cell culture plate. The bone marrow cavity was washed thoroughly by drawing and expelling PBS with a syringe until the bones became pale, and then the compact bones were excised into fragments of about 1 ~ 3 mm2 using sterile scissors in 1.5-ml centrifuge tubes. The PBS was removed and the fragments suspended in 1 ml of α-MEM containing 10 % (vol/vol) FBS in the presence of 1 mg/ml (wt/vol) of collagenaseII (Gibco). The fragments were digested for 1 ~ 1.5 h in an incubator at 37 °C. The digestion was stopped when the bone fragments become loosely attached to each other, digestion media and released cells were aspirated and discarded, then the bone fragments were washed three times with PBS, followed by incubation in α-MEM containing 10 % (vol/vol) FBS at 37 °C in 5 % CO2. Colony (with more than 50 spindle-shaped cells) numbers of BMA group (BM from aged mice), BA group (bone from aged mice), and BM A+B A group (co-culture of BM with bone from aged mice, direct contact) were compared; the colony number of (BMY+BY) group and (BMA+BY) group were compared; and finally, a transwell was used to separate BM and bone to compare the colony number of (BMY/BY) group (co-culture of BM with bone from young mice, indirect contact) and (BMA/BY) group (co-culture of BM from aged mice with bone from young mice, indirect contact).

Flow cytometry and magnetic cell sorting

Cells from BMY and BMA were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD11b and CD45, PE-conjugated anti-mouse Ter119 and CD31, APC-conjugated anti-mouse CD45R (B220) and Ly-6G (Gr-1), or PerCP-conjugated anti-mouse CD3 and F4/80 (BD, Franklin L, NJ) for 30 min at 4 °C in the dark. After washing, cells were suspended and analyzed by flow cytometry analysis. Cells from BMA were harvested to sort CD11b+, B220+, and Ter119+ cells by magnetic cell sorting (MACS) according to their data sheet. Sorted CD11b+, B220+, Ter119+, and BMA cells were seeded in the upper chamber of a transwell (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY) with 0.4-μm pore-size membrane, respectively, while the lower chamber of 12-well plate was seeded young bone fragment and incubated at 37 °C in 5 % CO2.

Proliferation and migration assays

Murine MSC cell line C3H10T1/2 were seeded in the lower chamber of a 12-well plate at a density of 3 × 104 cells per well. BMY and BMA were cultured (4 × 106 per well) in the transwell chamber (Corning Incorporated, USA) with 0.4-μm pores and incubated at 37 °C in 5 % CO2. C3H10T1/2 proliferation was evaluated after 12, 24, and 36 h co-culture by counting cell numbers. The wound healing assay was performed to test the migration of C3H10T1/2 cocultured with BMY and BMA. C3H10T1/2 were serum-starved (α-MEM containing 0.5 %FBS) for 8 h. Linear scratch wounds were made on the cell monolayers, and cell debris was removed by washing with PBS, and then fresh α-MEM containing 2 % FBS was added. BMY and BMA were seeded into the upper chamber of the transwell with 0.4-μm pores. Pictures were taken under microscopy at approximately the same fields at selected time points (0, 10, 20 h).

Western blot

C3H10T1/2 were stimulated with BMY and BMA for 0, 15, 30, and 60 min. Then, C3H10T1/2 were harvested and lysed with RIPA lysis buffer (Applygen technologies, Beijing, CHN) containing PMSF and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA method (Applygen Technologies). The proteins were first separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to PVDF membrane. Membranes were incubated with antibodies against p-p38, p-ERK1/2, ERK1/2, and p-JNK (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA).

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least three times. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. Statistical significance was assessed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test, parametric statistics.

Results

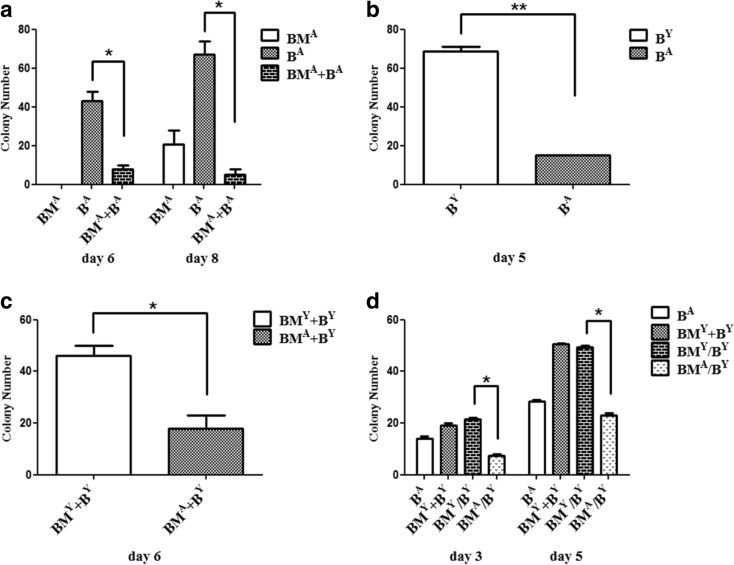

BMA decreased the formation of MSC colony

First, we compared the difference of the MSC colony number between three methods [flushing out bone marrow (BMA), collagenase-digested bone fragments (BA), and bone marrow plus bone fragments (BMA+BA)] of isolating and culturing aged mice MSCs. Results showed that the MSC colony numbers in the (BMA+BA) group were significantly less than in the BA group (Fig. 1a). Next, we analyzed whether the MSC colony number from aged mice was less than that of young mice and compared collagenase-digested bone fragments from aged mice (BA) and from young mice (BY), as shown in Fig. 1b, which was confirmed. As such, we unified the quantity and source of bone fragments, and compared the MSC colony number when BMA and BMY were co-cultured with the same bone fragments. We found that BMA decreased the formation of MSC colonies (Fig. 1c). Moreover, considering that this phenomenon may be related to the direct contact between bone marrow and bone fragments, we added the transwell to separate them for culture and found, as shown in Fig. 1d, that BMA decreased the formation of MSC colonies regardless of whether bone marrow and bone fragments were in direct or indirect contact.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of MSC colony numbers. a Three methods [flushing-out bone marrow (BMA), collagenase-digested bone fragments (BA), bone marrow plus bone fragments (BM A+B A)] were used to isolate and culture the aged mice MSCs. The colony number in the (BM A+B A) group was significantly less than that in the BA group at 6 and 8 days.*P < 0.05. b The method of collagenase-digested bone fragments was used to isolate and culture aged and young mice MSCs. Colonies from aged mice was significantly less than from young mice (BA vs BY), **P < 0.01. c BMA and BMY co-culture with the same bone fragments, *P < 0.05. d Transwell was added to separate bone marrow and bone fragments in culture. BMA decreased the formation of MSCs colonies, *P < 0.05. Data are shown from one of three repeated experiments. (B Y bone fragments from young mice, B A bone fragments from aged mice, BM Y BM from young mice, BM A BM from aged mice, BM+B BM cocultured with B directly, BM/B BM in transwell chamber co-cultured with B)

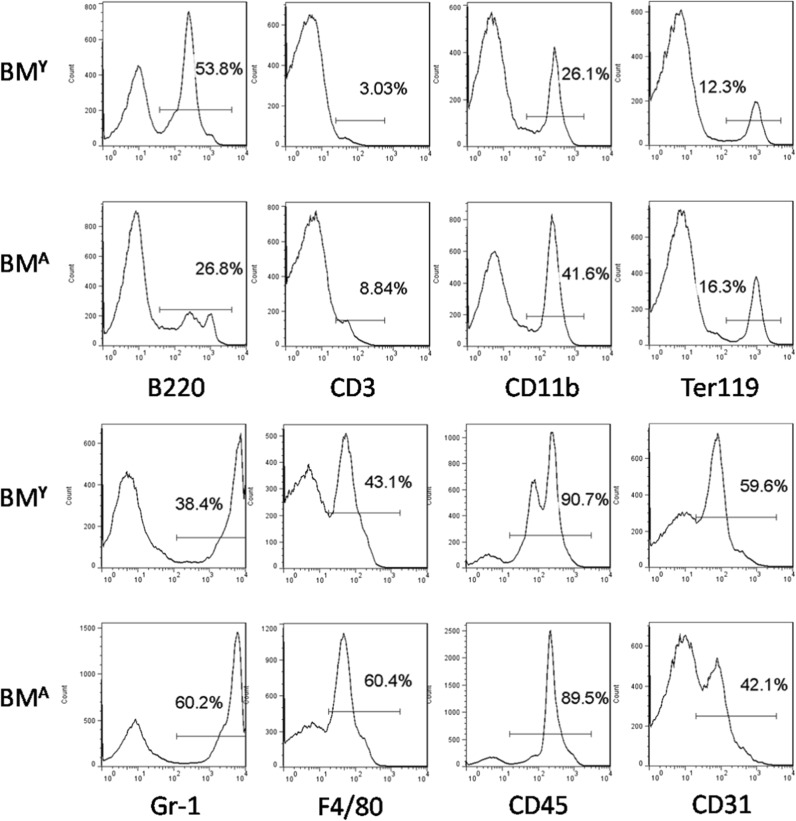

Immunophenotypic characterization of BMA and BMY

To compare the characteristics of BMA and BMY, a flow cytometry assay was used to examine the composition of BM. The results showed that the proportion of B220+ cells in BMA was significantly less than that in BMY, while other subsets of BM such as CD11b+, CD3+, Gr-1+, and F4/80+ cells were higher (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Flow cytometry analysis of BMA and BMY. The proportion of subsets in BMA and BMY: CD3+, CD11b+, Ter119+, Gr1+, and F4/80+ cells in BMA are significantly higher than those in BMY, while B220+ cells in BMA are significantly lower than in BMY. Data are shown from one of three repeated experiments

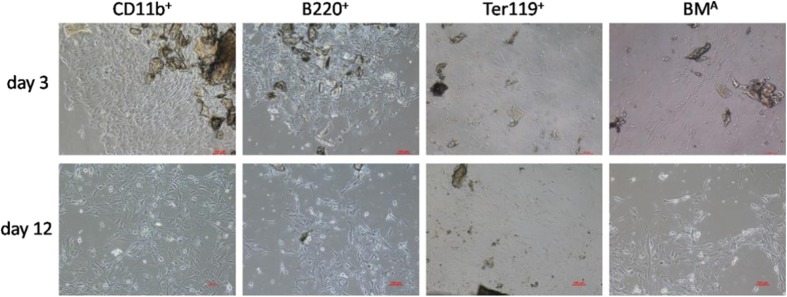

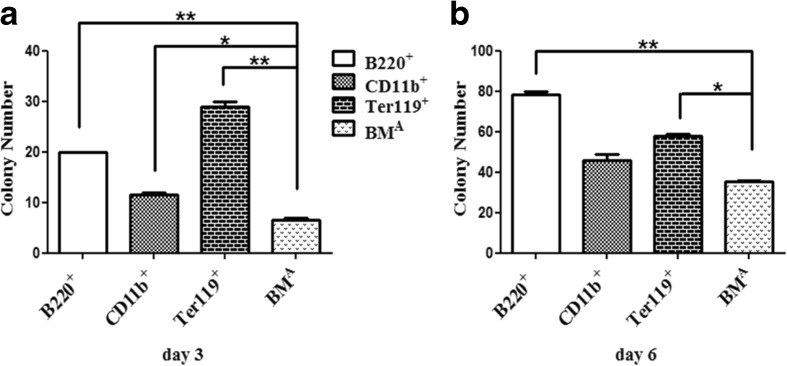

CD11b+, B220+, and Ter119+ cells in BMA did not decrease MSC colony formation

To further discuss which subset of BMA would play a role in decreasing MSC colony formation, we used MACS to sort CD11b+, B220+, and Ter119+ cells, then co-cultured with bone fragments using a transwell. On the third day, the colony number of MSCs began to show differences (Fig. 3) and the number in the total BM group was the least (Fig. 4a). On the sixth day, this difference was still there (Fig. 4b). This result suggested that these three subsets (CD11b+, B220+, and Ter119+) in BMA might not decrease MSC colony formation.

Fig. 3.

MSC colony formation. Morphology of MSC colonies from different subsets of BMA cocultured with bone fragments at day 3 and day 12. Data are shown from one of three repeated experiments (scale bar = 100 μm)

Fig. 4.

MSC colony number of different subsets of BMA cocultured with bone fragments. a The MSC colony number of B220+, CD11b+, and Ter119+ cells of BMA cocultured with bone fragments are significantly more than the number of BMA co-cultured with bone fragments at day 3.*P < 0.05;**P < 0.01. b The MSC colony number of B220+, CD11b+, and Ter119+ cells of BMA cocultured with bone fragments are more than the number of BMA co-cultured with bone fragments at day 6.*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Data are shown from one of three repeated experiments

BMA decreased the migration of MSC cell line C3H10T1/2 compared with BMY

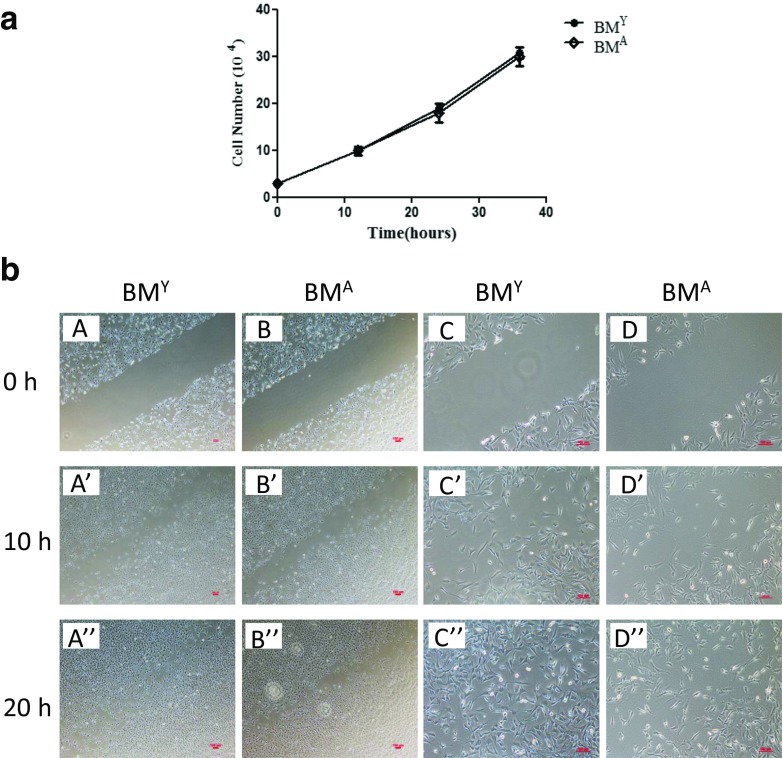

We found that MSC colony numbers in the BMA plus bone fragments group was significantly less than that in the BMY plus bone fragments group through our assays, which prompted us to take two aspects, proliferation and migration of MSCs, into consideration. In other words, BMA might decrease the proliferation or migration of MSCs. As shown in Fig. 5a, we did not find a difference in the proliferation capacity of C3H10T1/2 co-cultured with BMA or BMY. As is well-known, MSCs have powerful healing capacity which has been reported by a multitude of studies. As such, we used a wound-healing test to investigate whether some cytokines in the bone marrow affected the migration of C3H10T1/2 and we observed cell movement in the direction of the wound under BMA and BMY stimulation. Through microscopy, we found a slower migration of C3H10T1/2 undergoing BMA stimulation (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Proliferation and migration of C3H10T1/2 undergoing BMA or BMY stimulation. a Growth curve of C3H10T1/2 cocultured with BMA or BMY. b Wound healing of C3H10T1/2 under BMA or BMY stimulation. (A, B × 40; C, D × 100). Data are shown from one of three repeated experiments (scale bar = 100 μm)

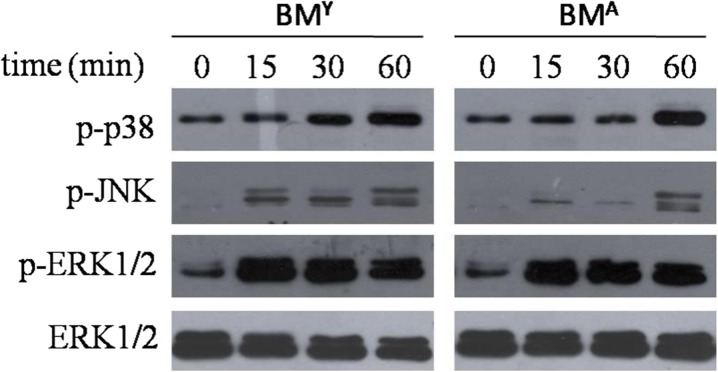

The expression of p-p38, p-ERK1/2, and p-JNK on C3H10T1/2

To further study the signaling pathway involved in C3H10T1/2 stimulated with BMA and BMY, we examined the change of the MAPK/ERK (mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinases) and Jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling pathway, which are not only important to regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis but also to regulate cell migration. Western blot analysis showed the phosphorylation levels of p38, JNK, and ERK1/2 were all increased with the stimulation, but only p-JNK in the BMY group was higher than in the BMA group at 15, 30, and 60 min (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Expression of p-p38, p-JNK, p-ERK1/2, and ERK1/2 was examined by Western blot. p38, JNK, and ERK1/2 pathways were all activated, but only p-JNK in the BMY group was higher than in the BMA group at 15, 30, and 60 min. Data are shown from one of three repeated experiments

Discussion

MSCs are one of the important stem cells in the microenvironment. They have the ability to self-renew, proliferate and support hematopoiesis. MSCs show great capacity to differentiate toward different lineages, such as osteoblasts, adipocytes, chondroblasts, etc. MSCs play an important role in wound healing. This involves migration of MSCs from the BM microenvironment to the damaged area. Indeed, it was shown that MSCs could migrate to many parts of the body, such as across the blood-brain barrier to the cerebral ischemia region (Chen et al. 2001) or to damaged myocardium (Devine et al. 2001). Current studies are mostly based on MSCs’ differentiation properties and exceptional repairing capacity (Veronesi et al. 2014), but few have reported the effects of the BM microenvironment on migration and proliferation of MSCs, which is the problem of MSCs originally moving out of the BM microenvironment.

In our study, we mainly discussed BMA and BMY on migration and proliferation of MSCs. In our early assay of culturing MSCs using the bone marrow plus bone fragments method (Yang et al. 2013), we found that the number of MSC colonies from aged mice, no matter female or male, was significantly less than that from young mice. Next, we compared the number of MSC colonies from aged and young mice using the bone fragments method and found that the number from aged mice was indeed less than from young mice, highlighting that the increasing age of the mice resulted in a reduction in MSC number. Thus, to unify the quantity and source of bone fragments, we cocultured BMA and BMY with the same bone fragments, respectively, and found BMA decreased the formation of MSC colonies significantly. Furthermore, we used a transwell to separate BM and bone fragments and allowed the soluble molecules in BM affect bone fragments, the results of which demonstrated that soluble molecules played an important role in BMA decreasing MSC colony formation.

The flow cytometry results from BM revealed that the B220+, CD11b+, CD3+, Gr-1+, and F4/80+ subsets had significant differences. Similar to earlier studies (Waterstrat and Van Zant. 2009; Zediak et al. 2007; Shao et al. 2011), there were more myeloid lineage cells than lymphoid lineages cells in aged BM. Consequently, we sorted out B220+, CD11b+, and Ter119+ cells which had greater differences and a higher proportion from BMA to coculture with the same bone fragments, respectively. Unfortunately, none of these played a role in the decreased formation of MSC colonies. Therefore, further study is required to test which subset or cell matrix in BMA might have an impact. We supposed the effect of the BM microenvironment on the process of MSCs moving out from stem cell niche might be related to two aspects: proliferation and migration. However, proliferation assay did not show that BMA decreased the formation of MSC colonies, so we continued to explore the difference in migration.

A transwell chamber is a classic method to study cell migration. We chose a chamber with an 8-μm pore-size membrane to perform the migration assay and a 0.4-μm pore-size membrane for the wound-healing assay, as cells cannot cross a membrane with a pore-size of less than 3 μm. Both the migration (data not shown) and wound healing assays showed that the capacity of C3H10T1/2 was decreased under the stimulation of BMA. It is well known that SDF-1/CXCR4 plays a very important role in stem cell mobilizing and homing (Askari et al. 2003), and our results showed that the expression of SDF-1 mRNA level in BMA was significantly lower than that in BMY (data not shown), suggesting BMA was not conducive for the migration of MSCs. Additionally, we explored whether the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway was involved in the migration of MSCs affected by BM. The MAPK/ERK pathway has been shown to regulate a wide variety of cellular processes including cell survival, proliferation, and migration (Muslin 2008; Gao et al. 2009). There are three major components of MAPK/ERK and JNK pathways: ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and JNK. We detected these three pathways by Western blot and found they were all activated. We did not find any significant difference in p-ERK and p-p38 between BMA-induced and BMY-induced group. However, the phosphorylation of JNK in BMY group was markedly higher than that in BMA group. Literatures (Wang et al. 2005; Chishti et al. 2013) have showed that moderate activation of JNK signaling resulted in increased stress tolerance and extended life span in various organisms. Yuan et al reported that MSC migration was affected via JNK signal pathway (Yuan et al. 2013).Whether the low p-JNK expression is directly related to the decreased effect of BMA on MSCs’ migration merits further investigation.

Collectively, our study not only reveals a novel perspective about the effect of aged bone marrow environment on the proliferation and migration of MSCs but also provides some hints for better clinical utilization of MSCs.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Lindsey Jones (Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California) for her critical reading of the paper. This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81271936), the Chinese National Key Program on Basic Research (2010CB529904).

Footnotes

Yan-Mei Yang and Ping Li contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Ning Wen, Phone: 8610-68166874, Email: ning1972@sina.com.

Xiao-Xia Jiang, Phone: 8610-68166874, Email: smilovjiang@163.com.

References

- Askari AT, Unzek S, Popovic ZB, Goldman CK, Forudi F, Kiedrowski M, Rovner A, Ellis SG, Thomas JD, DiCorleto PE, Topol EJ, Penn MS. Effect of stromal cell derived factor-1 on stem-cell homing and tissue regeneration in ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2003;362:697–703. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruder SP, Jaiswal N, Haynesworth SE. Growth kinetics, self-renewal, and the osteogenic potential of purified human mesenchymal stem cells during extensive subcultivation and following cryopreservation. J Cell Biol Chem. 1997;64:278–294. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(199702)64:2<278::aid-jcb11>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, Weber JM, Olson DP, Knight MC, Martin RP, Schipani E, Divieti P, Bringhurst FR, Milner LA, Kronenberg HM, Scadden DT. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425:841–846. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Li Y, Wang L, Zhang Z, Lu D, Lu M, Choop M. Therapeutic benefit of intravenousadministration of bone marrow stromal cells after cerebral ischemia in rats. Stroke. 2001;32:1005–1011. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.32.4.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen FM, Wu LA, Zhang M, Zhang R, Sun HH. Homing of endogenous stem/progenitor cells for in situ tissue regeneration: promises, strategies, and translational perspectives. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3189–3209. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LZ, Yin SM, Zhang XL, Chen JY, Wei BX, Zhan Y, Yu W, Wu JM, Qu J, Guo ZK. Protective effects of human bone marrow mesenchymalstemcells on hematopoietic organs of irradiated mice. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2012;20:1436–1441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chishti MA, Kaya N, Binbakheet AB, Al-Mohanna F, Goyns MH, Colak D. Induction of cell proliferation in old rat liver can reset certain gene expression levels characteristic of old liver to those associated with young liver. Age (Dordr) 2013;35:719–732. doi: 10.1007/s11357-012-9404-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino B, Sullo N, Siniscalco D, De Angelis A, Rossi F. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10:681–687. doi: 10.1517/14712591003610614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dazzi F, Ramasamy R, Glennie S, Jones SP, Roberts I. The role of mesenchymal stem cells in haemopoiesis. Blood Rev. 2006;20:161–171. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haan G, Nijhof W, Van Zant G. Mouse strain-dependent changes in frequency and proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells during aging: correlation between lifespan and cycling activity. Blood. 1997;89:1543–1550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine SM, Bartholomew AM, Mahmud N, Nelson M, Patil S, Hardy W, Sturgeon C, Hewett T, Chung T, Stock W, Sher D, Weissman S, Ferrer K, Mosca J, Deans R, Moseley A, Hoffman R. Mesenchymal stem cells are capable of homing to the bone marrow of non-human primates following systemic infusion. Exp Hematol. 2001;29:244–255. doi: 10.1016/S0301-472X(00)00635-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnini A, Re F, Orlando F, Provinciali M. Intrinsic and microenvironmental defects are involved in the age-related changes of Lin-ckit + hematopoietic progenitor cells. Rejuvenation Res. 2007;10:459–472. doi: 10.1089/rej.2006.0524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Priebe W, Glod J, Banerjee D. Activation of signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 and focal adhesion kinase by stromal cell-derived factor 1 is required for migration of human mesenchymal stem cells in response to tumor cellconditioned medium. Stem Cells. 2009;27:857–865. doi: 10.1002/stem.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Jin F, Freitas A, Szabo P, Weksler ME. Impaired regeneration of the peripheral B cell repertoire from bone marrow following lymphopenia in old mice. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:500–505. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200102)31:2<500::AID-IMMU500>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ZY, Wang CQ, Lu G. Effects of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells on hematopoietic recovery and acute graft-versus-host disease in murine allogeneic umbilical cord blood transplantation model. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2011;32:786–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loebinger MR, Eddaoudi A, Davies D, Janes SM. Mesenchymal stem cell delivery of TRAIL can eliminate metastatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4134–4142. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzini L, Ferrero I, Luparello V, Rustichelli D, Gunetti M, Mareschi K, Testa L, Stecco A, Tarletti R, Miglioretti M, Fava E, Nasuelli N, Cisari C, Massara M, Vercelli R, Oggioni GD, Carriero A, Cantello R, Monaco F, Fagioli F. Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a Phase I clinical trial. Exp Neurol. 2010;223:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min H, Montecino-Rodriguez E, Dorshkind K. Effects of aging on the common lymphoid progenitor to pro-Bcell transition. J Immunol. 2006;176:1007–1012. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SJ, Wandycz AM, Akashi K, Globerson A, Weissman IL. The aging of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. 1996;2:1011–1016. doi: 10.1038/nm0996-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muslin AJ. MAPK signalling in cardiovascular health and disease: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Clin Sci (Lond) 2008;115:203–218. doi: 10.1042/CS20070430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prockop DJ. Marrow stromal cells as stem cells for nonhematopoietic tissues. Science. 1997;276:71–74. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao HW, Xu QY, Wu QL, Ma Q, Salqueiro L, Wang J, Eton D, Webster KA, Yu H. Defective CXCR4 expression in aged bone marrow cells impairs vascular regeneration. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:2046–2056. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01231.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudo K, Ema H, Morita Y, Nakauchi H. Age-associated characteristics of murine hematopoietic stem cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1273–1280. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.9.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veronesi F, Pagani S, Della Bella E, Giavaresi G, Fini M. Estrogen deficiency does not decrease the in vitro osteogenic potential of rat adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Age. 2014;36:1225–1238. doi: 10.1007/s11357-014-9647-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MC, Bohmann D, Jasper H. JNK extends life span and limits growth by antagonizing cellular and organism wide responses to insulin signaling. Cell. 2005;121:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterstrat A, Van Zant G. Effects of aging on hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YM, Li H, Zhang L, Dang RJ, Li P, Wang XY, Zhu H, Guo XM, Zhang Y, Liu YL, Mao N, Jiang XX, Wen N. A new method for isolating and culturing mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2013;21:1563–1567. doi: 10.7534/j.issn.1009-2137.2013.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L, Sakamoto N, Song G, Sato M. Low-level shear stress induces human mesenchymal stem cell migration through the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis via MAPK signaling pathways. Stem Cell Dev. 2013;22:2384–2393. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zediak VP, Maillard I, Bhandoola A. Multiple prethymic defects underlie age-related loss of T progenitor competence. Blood. 2007;110:1161–1167. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-071605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Gui J, Dohkan J, Cheng L, Barnes PF, Su DM. Lymphohematopoietic progenitors do not have a synchronized defect with age-related thymic involution. Aging Cell. 2007;6:663–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]