Abstract

Text message delivered prevention interventions have the potential to improve health behaviors on a large scale, including reducing hazardous alcohol consumption in young adults. Online crowdsourcing can be used to efficiently develop relevant messages, but remains largely understudied. This study aims to use online crowdsourcing to evaluate young adult attitudes toward expert-authored messages and to collect peer-authored messages. We designed an online survey with four drinking scenarios and a demographic questionnaire. We made it available to people who reported age 18–25 years, residence in the US, and any lifetime alcohol consumption via the Amazon Mechanical Turk crowdsourcing platform. Participants rated 71 sample text messages on instrumental (helpful) and affective (interesting) attitude scales and generated their own messages. All messages were coded as informational, motivational, or strategy facilitating. We examined differences in attitudes by message type and by drinking status and sex. We surveyed 272 participants in 48 h, and 222 were included in analysis for a total participant payment cost of $178. Sample mean age was 23 years old, with 50 % being female, 65 % being of white race, and 78 % scored as hazardous drinkers. Informational messages were rated the most helpful, whereas motivational messages were rated the most interesting. Hazardous drinkers rated informational messages less helpful than non-hazardous drinkers. Men reported messages less helpful and interesting than women for most categories. Young adults authored 161 messages, with the highest proportion being motivational. Young adults had variable instrumental and affective attitudes toward expert-authored messages. They generated a substantial number of peer-authored messages that could enhance relevance of future alcohol prevention interventions.

Keywords: Crowdsourcing, Young adult, Intervention

INTRODUCTION

Mobile phones are increasingly being recognized as an important means of delivering interventions to influence health behaviors [1]. Mobile phone messaging, primarily through Short Message Service (SMS), has been used to reduce smoking [2], increase medication adherence [3], and reduce harmful alcohol use among young adults [4, 5]. Compared to printed health materials, SMS offers the advantage of providing support in an individual’s natural environment, tailoring material to individual characteristics, and adapting to individual feedback over time. Compared to other communication modalities, such as smart phone applications (“apps”), SMS have the advantages of instant transmission, low cost, and universal use.

Tailoring behavioral interventions to relevant user groups, if not individuals, can improve uptake and effects on behavior change [6]. To achieve appropriate tailoring, a user-centered and iterative framework for designing mobile health interfaces has been recommended [7]. Designing user-informed materials can improve the socio-cultural relevance of messages and target topics that may not have been identified by experts [8]. Traditionally, health behavior scientists have attempted to improve relevance and user-centered focus of material through interviews and focus groups, which can take a long time and cost considerable amounts to perform.

A promising but relatively understudied form of collecting peer feedback for SMS-based interventions is through online labor markets, or “crowdsourcing”. Internet-based crowdsourcing platforms coordinate large sets of voluntary online workers with human intelligence tasks (HITs). Prior studies demonstrate that crowdsourcing is a viable modality for human subject experimentation [9] and has comparable validity to a young adult university pool [10]. Although prior studies have used crowdsourcing to gain feedback on health promotion materials [11], and identify preferences between different formatting of health messages [12], none have used crowdsourcing to understand attitudes explicitly toward messages aimed at reducing alcohol consumption nor to collect peer-authored behavioral support messages for reducing alcohol consumption.

Therefore, our primary aim was to evaluate instrumental and affective attitudes among young adult drinkers to expert-authored messages. Specifically, we asked participants to rate a series of text messages in response to four different hypothetical situations related to drinking intentions. The secondary aim was to collect peer-authored messages. For each drinking scenario, we asked participants to write any other messages they think would help reinforce a decision to drink below hazardous levels. We explored how alcohol use status (AUDIT-C) and user sex (male/female) influenced attitudes. Level of drinking and sex has been shown to be important moderators of intervention effectiveness [13], which suggests there would be potential differences in attitudes. Findings from this study were used to inform the text message feedback provided to young adult drinkers as part of a 12-week intervention [5].

METHODS

Participants

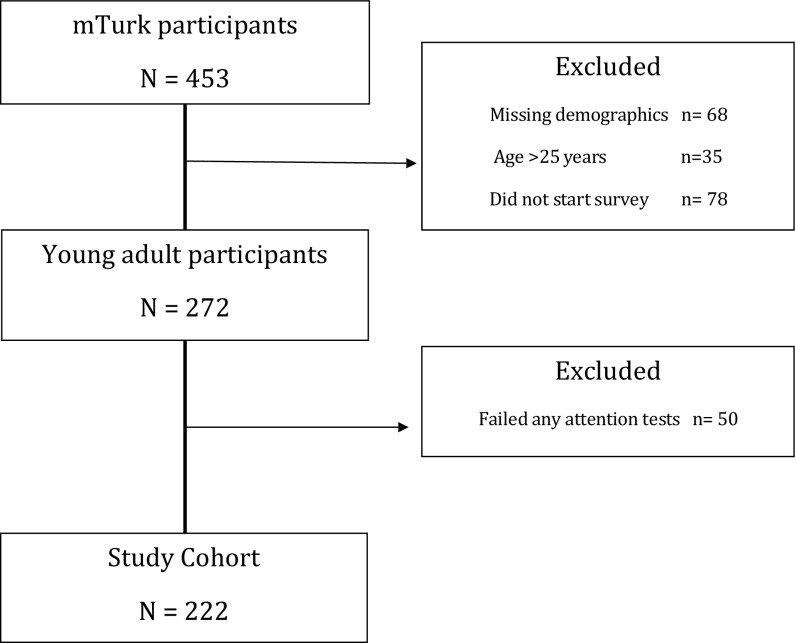

Participants were between 18 and 25 years of age and were recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (www.Mturk.com) between October 27 and 29, 2012. A Mechanical Turk account was created for free and loaded in advance with funds to compensate the participants (Fig. 1). Potential participants were recruited through a human intelligence task (HIT) posted on the mTurk site that contained a brief description of the study and a link to an online informed consent form. To be included, participants needed to be fluent in English, live in the US, and have consumed at least one standard drink of alcohol at some point in their past. To ensure reliable participants, we also required that they have an approval rate of at least 95 % in the HITs they had previously worked on.

Fig. 1.

Participant flow diagram

Procedures

Upon reading the study’s Institutional Review Board–approved consent form, potential participants were asked to hyperlink to a screening questionnaire to confirm eligibility, including questions regarding age and any prior consumption of alcohol (yes/no). Participants who reported their age as between 18 and 25 years and any lifetime alcohol use were asked to complete a questionnaire assessing demographics and alcohol use and another asking them to rate expert-authored messages. They were also asked to author their own messages, which was not mandatory for payment. After the questionnaires were completed, a completion code was presented to the participant. In order for the participant to receive compensation, he or she had to enter the completion code on the Mechanical Turk Website. Once a completion code had been entered, an investigator reviewed the survey to ensure completion and approved the code, thus automatically sending compensation to the participant’s account. Participants were paid US $0.80 for completed questionnaires. This level of compensation was chosen in an attempt to approximate the median pay rate for HITs requiring similar time commitments. Participant IDs were tracked, and only one entry was allowed from a single participant to prevent duplicate entries from the same person.

Measures

In the first questionnaire, we asked a set of questions about the participants demographic background, including gender, age, race/ethnicity, highest education level, and employment status. To assess severity of alcohol use, we used the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test for Consumption (AUDIT-C). The AUDIT-C consists of three alcohol consumption measures (number of drinks per day, frequency of alcohol consumption, and frequency of consuming five or more drinks on one occasion) and is scored from 0 to 12. Literature supports the internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and validity of the AUDIT-C in identifying hazardous drinking [14]. Responses were scored to designate a participant as a hazardous drinker (score ≥4 for men and ≥3 for women) [15].

In the second questionnaire, participants were presented with four different hypothetical situations related to drinking intentions. The introduction stated: “By participating in this research study, you will be helping us design a program that will be used to change drinking behaviors in young adults through text messaging. Imagine you are asked about your drinking intentions for the upcoming weekend through text messaging and you respond in the following ways.” Situation 1: “You text us that you plan to drink to get drunk.” Situation 2: “You text us that you do NOT plan to drink alcohol.” Situation 3: “You text us that you had planned on drinking to get drunk BUT are willing to set a goal to reduce your drinking below hazardous levels.” Situation 4: “You text us that you plan on drinking to get drunk and are NOT willing to set a goal to reduce your drinking.” Following each situation description, participants were presented with a number of feedback messages (32 for Situation #1; 10 for Situation #2; 19 for Situation #3; 10 for Situation #4). They were told to rate each message on level of being “helpful” and “interesting” on a scale from 0 to 7, where 0 is not at all and 7 is extremely. We chose to measure attitudes on both instrumental (helpful) and affective (interesting) scales because, according to Ajzen [16], both are independent and essential components of attitude. Instrumental evaluations relate to whether a message could benefit them in some way whereas affective evaluations relate to their emotional response to the messages. They also represent two key features for maximizing effect and minimizing attrition [7].

A sample of investigator-generated messages used in response to each hypothetical situation is presented in Table 1. Messages were taken either from existing written material “NIH Rethinking Drinking”, from existing statistics on alcohol use and injury, or created by the investigators. Following each situation’s section of messages, participants were then asked to provide any other messages that they think would help reinforce a decision to drink below hazardous levels.

Table 1.

Sample of investigator-generated feedback messages by drinking intention situation

| Situation | Sample of feedback messages | Category | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | You text us that you plan to drink to get drunk. | We are concerned you have made a choice to binge drink this weekend. | Motivational |

| More than 1.6 million hospitalizations each year are due to excessive alcohol use. | Informational | ||

| Try writing down the reasons you want to drink less, like improving your health or getting along better with family or friends. | Strategies | ||

| 2 | You text us that you do NOT plan to drink alcohol. | It sounds like you have made a healthy choice not to drink this weekend. | Motivational |

| A single binge episode can weaken muscle growth and recovery. | Informational | ||

| Stick by your decision; be polite but firm when you refuse a drink. | Strategies | ||

| 3 | You text us that you had planned on getting drunk BUT are willing to set a goal to reduce your drinking below hazardous levels. | We believe that you have made a good choice to limit your drinking. | Motivational |

| 30 % of academic problems in college are due to excessive alcohol use. | Informational | ||

| Don’t let drinking get in the way of a better you! Run, walk, or go play a game with friends. | Strategies | ||

| 4 | You text us that you plan on getting drunk and are NOT willing to set a goal to reduce your drinking. | We understand it is difficult to make changes in your life. | Motivational |

| Research shows that people who binge drink put themselves at risk for both immediate and long term health problems. | Informational | ||

| Try to notice how drinking makes you feel and how it affects your judgment. | Strategies | ||

Data quality

Given the unmonitored nature of online mTurk surveys, we attempted to optimize quality by identifying participants who were not paying attention or providing unreliable answers. We included eight basic arithmetic questions interspersed throughout the 71 messages, with response options ranging from 0 to 7. For example, “Four plus three equals?” We assumed all 18–25-year-olds would be able to complete the basic arithmetic if paying attention; therefore, any participant with any incorrect response was considered not paying attention. Response time was assessed as the number of minutes spent completing the survey, as calculated by using time stamps at survey initiation and completion.

Data analysis

To determine the feasibility of using crowdsourcing to collect user-feedback from young adults, we report the flow of participants from HIT initiation to questionnaire completion. We also describe the proportion of participants who failed the tests of attention. To determine differences in attitudes across individual messages, we calculated both the mean ratings and the proportion of participants who rated the message at least somewhat helpful or interesting (score ≥4). Two investigators independently coded all messages as either informational, motivational, or strategy facilitating. We chose these categories because our intervention is modeled on the Information Motivation Behavior model [17]. Information includes the knowledge about a medical condition and its effect on the body. Motivation encompasses personal attitudes towards the behavior and the patients’ subjective norm. Strategies include specific behavioral tools useful such as planning for self-regulation stress and managing peer pressures. In cases where there was disagreement, which occurred in five (7 %) of messages, the investigators discussed the discrepancy and came to an agreement. To determine whether there were differences in attitudes by message category, we first performed ANOVA with Bonferroni correction in post hoc tests. Finally, we categorized and compared peer-generated messages using similar methods to the investigator-generated messages. All data were analyzed using STATA 10.0 (Statacorp, Inc.).

RESULTS

Sample description

Four hundred fifty-three mTurk participants accessed our demographics questionnaire. A total of 78 (17 %) did not start the survey, 68 (15 %) did not provide complete demographics, and 35 (8 %) reported their age as greater than 25 years old, resulting in 272 participants. Among this group, 50 (18 %) had at least one incorrect response to simple arithmetic question, resulting in 222 individuals available for analysis. The average time to complete the survey was 7 min (SD 4; range 3–16).

As shown in Table 2, mean age was 23 years old, with 50 % being female and the majority (65 %) being of white race. There was a significant proportion (26 %) of young adults who reported themselves as Asian race and 10 % who were of Hispanic ethnicity. The cohort was highly educated, with 87 % having at least some college education. The majority of participants reported either part- or full-time employment. In regards to alcohol use, the majority (67 %) were drinking alcohol at least two to four times per month, 20 % were drinking more than four drinks per occasion, and 72 % reporting at least one drinking occasion where they consumed six or more standard alcoholic drinks. Using the AUDIT-C, 174 (78 %) were rated as hazardous drinkers.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics

| Variable | Enrolled (N = 222) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 23 (1.9) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 112 (50) |

| Race | |

| African American | 21 (10) |

| White | 144 (65) |

| Asian | 57 (26) |

| Other | 0 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 23 (10) |

| Highest level of education | |

| <High school | 4 (2) |

| High school grad or GED | 25 (11) |

| Some college | 83 (37) |

| College graduate | 110 (50) |

| Employment | |

| Unemployed | 38 (17) |

| Part-time employment | 48 (22) |

| Full-time employment | 97 (44) |

| Student/non-employed | 39 (17) |

| Owns a mobile phone with SMS | 218 (98) |

| How often do you have a drink containing alcohol? | |

| Never | 13 (6) |

| Monthly or less | 62 (28) |

| 2 to 4 times a month | 80 (36) |

| 3 or 4 times per week | 38 (22) |

| 4 or more times per week | 19 (9) |

| How many standard drinks do you have on a typical day when drinking? | |

| Don’t currently drink | 11 (5) |

| 1 or 2 | 98 (44) |

| 3 or 4 | 68 (31) |

| 5 or 6 | 35 (16) |

| 7 or more | 10 (4) |

| How often do you have six or more drinks on one occasion? | |

| Never | 63 (28) |

| Less than monthly | 95 (43) |

| Monthly | 38 (17) |

| Weekly | 24 (11) |

| Daily or almost daily | 2 (1) |

Attitudes toward expert-authored messages

Young adult participants rated expert-authored messages as being moderately “helpful” [mean (SD) = 3.4 (1.4)] and moderately “interesting” [mean (SD) = 3.2 (1.3)]. There was a moderate to high inter-correlation between interesting and helpful ratings across messages (alpha = 0.67–0.84). Overall, women rated messages more helpful than men, with means (SD) of 3.6 (1.4) and 3.2 (1.3) respectively; p = 0.01. There were no significant differences overall in ratings by hazardous drinking status or by drinking scenario.

A total of 40 (56 %) of the messages were rated as at least somewhat helpful by at least half of participants whereas only 25 (35 %) were rated as at least somewhat interesting. The three messages with highest proportion of participants rating them as at least somewhat helpful were: “Drinking more than 5 drinks in a 2 h period can result in alcohol poisoning, a medical emergency.” and “Try spacing out one drink per hour, take a break of 1 h between drinks or space a glass of water between drinks.” and “As the sober partyer, look out for friends.” The three messages with highest proportion of participants rating them as at least somewhat interesting were: “2 drinks = 1 cheeseburger in calories.” and “Excessive drinking can decrease the testosterone in a man’s body and cause impotence.” and “You would need to run 25 min at 6 miles an hour to burn off one drink.”

We categorized expert-authored messages as informational (44 %), motivational (18 %), and strategy facilitating (38 %). The proportion of messages differed across categories because the intervention was not designed to split the message types evenly and was assigned post facto. As seen in Table 3, motivational messages had significantly lower mean ratings than informational and strategy-facilitating messages, F(2, 600) = 9.39, p < 0.0001 for being helpful and F(2, 600) = 26.3, p < 0.0001 for being interesting. A total of 23 (74 %) of informational, three (23 %) of motivational, and 14 (52 %) of strategy-facilitating messages were rated as at least somewhat helpful by at least half of participants. A total of 0 (0 %) of informational, 22 (71 %) of motivational, and three (11 %) of strategy-facilitating messages were rated as at least somewhat interesting by at least a half of participants. Hazardous drinkers rated informational messages lower on being helpful than non-hazardous drinkers, but did not report different ratings for messages being interesting. Men reported lower helpfulness ratings than women for all message categories, with the largest difference in strategy-facilitating messages.

Table 3.

Differences in helpfulness and interestingness ratings between hazardous drinkers and non-hazardous drinkers and between men and women

| Helpfulness rating | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample (n = 201) | AUDIT-C+ (n = 160) | AUDIT-C− (n = 41) | Men (n = 103) | Women (n = 98) | ||||||||

| Feedback category | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | t (201) | M | SD | M | SD | t (222) |

| Motivational | 3.06 | 1.44 | 3.00 | 1.44 | 3.30 | 1.44 | 1.16 | 2.86 | 1.37 | 3.28 | 1.49 | 2.10* |

| Informational/educational | 3.62 | 1.48 | 3.50 | 1.47 | 4.13 | 1.44 | 2.45** | 3.34 | 1.42 | 3.93 | 1.49 | 2.90** |

| Tools and strategies | 3.62 | 1.57 | 3.55 | 1.58 | 3.92 | 1.52 | 1.36 | 3.29 | 1.49 | 3.97 | 1.59 | 3.16** |

| Interesting ratings | ||||||||||||

| Motivational | 2.58 | 1.48 | 2.52 | 1.48 | 2.77 | 1.49 | 0.93 | 2.47 | 1.37 | 2.69 | 1.59 | 1.07 |

| Informational/educational | 3.63 | 1.43 | 3.54 | 1.44 | 3.97 | 1.38 | 1.72 | 3.39 | 1.40 | 3.88 | 1.43 | 2.50* |

| Tools and strategies | 3.19 | 1.47 | 3.14 | 1.47 | 3.40 | 1.47 | 1.01 | 2.97 | 1.31 | 3.42 | 1.60 | 2.17* |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

Generation of peer-authored messages

Overall, there were 161 peer-authored feedback messages, with 45 (28 %) generated specific to Scenario 1, 54 (33 %) for Scenario 2, 50 (31 %) for Scenario 3, and 12 (8 %) for Scenario 4. The average number of user-authored messages per user was 1.1, with 112 participants (50 %) providing at least one message. Many of the messages were not directly quotable, given that the wording did not have sufficient clarity. For example: “be safe, have a DD” and “Learn not to need to drink!” We categorized 64 messages (40 %) as motivational, 56 messages (35 %) as informational, and 41 messages (25 %) as strategy facilitating (chi-squared 7.6; p = 0.02). A sample of peer-authored messages used in response to each hypothetical situation is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Sample of user-generated feedback messages by drinking intention situation

| Situation | Sample of user-generated feedback messages | Category | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | You text us that you plan to drink to get drunk. | Be responsible for yourself and be an example to others around you. | Motivational |

| Alcohol kills precious brain cells. | Informational | ||

| Try to drink water between drinks to avoid the dehydration and hangover. | Strategies | ||

| 2 | You text us that you do NOT plan to drink alcohol. | Not drinking will help you stay in control. | Motivational |

| Students who don’t drink do better in school. | Informational | ||

| Stay firm, don’t let others influence you decision | Strategies | ||

| 3 | You text us that you had planned on getting drunk BUT are willing to set a goal to reduce your drinking below hazardous levels. | Although it’d be best if you didn’t drink at all, we’re glad that you’re being safe. | Motivational |

| You will avoid needing to run 25 min to eliminate the calories from 1 drink! | Informational | ||

| Go reward yourself with something you wouldn’t normally do because you were too busy drinking. | Strategies | ||

| 4 | You text us that you plan on getting drunk and are NOT willing to set a goal to reduce your drinking. | Remember that being sober is not a sign of weakness but that of strength. | Motivational |

| A DUI cost 50 times more than a taxi. | Informational | ||

| See how many days/weeks you can go without getting drunk. Make it a bet or dare. | Strategies | ||

Discussion

This study provides evidence that young adults have variable instrumental and affective attitudes about expert-generated text message feedback to specific hypothetical drinking situations. It also demonstrates that crowdsourcing can be an efficient way to collect peer-generated messages for alcohol prevention programs. Although prior research has shown that crowdsourcing can be used to collect feedback on message formatting [12] and preferences across grammatical framing and style of messages [13], no prior study to our knowledge has elicited information about attitudes toward alcohol prevention messages. As well, one prior study had used crowdsourcing to generate peer messages for smoking cessation intervention [18], but none have been focused on alcohol.

We found that participants perceive most expert-authored feedback messages only moderately helpful and interesting, with instrumental attitudes more positive than affective attitudes. This suggests that there is room for improvement in how we interact and engage young adult drinkers in reducing harmful alcohol consumption, especially as we engage them emotionally (affectively). It may also reflect the ambivalence among young adults to receiving any feedback message in response to their drinking plans or behavior.

When examining mean ratings, motivational messages were rated the lowest. However, when examining the proportion of participants who rated messages helpful and interesting, we found that 71 % rated motivational messages interesting. This supports our design choice to examine both instrumental and affective attitudes, examine means as well as proportions, and to separate findings across different types of messages. Information about alcohol and the risks or consequences of drinking can adjust a young adult's perceptions and/or norms. Although education alone may not be effective in reducing alcohol consumption in young adults [19], alcohol-related information has been shown to be an important component in alcohol prevention programs, especially if they avoid coercion and encourage egalitarian communication [20]. Motivational messages likely act to keep young adults emotionally engaged in a program, which are critical to durable changes [21].

We found that participants with hazardous drinking behavior perceived educational messages as less helpful than those without hazardous drinking. This finding suggests that hazardous drinkers may be defensive to statements about health risks associated with drinking which fits with prior research [22] and supports developing feedback messages that do not elicit defensive postures among hazardous drinkers. It may also be that these messages create an emotional response and, although less desired, could allow for insight or reflection on actual behavior.

Women responded more favorably to all messages than men. This finding suggests that women may be more interested than men in interacting through text messaging, more open to communicating about their drinking intentions, or simply more interested in getting feedback on their health. We also found that the differences between women and men were most pronounced for messages providing strategies. This finding suggests that women find strategies more useful to help them manage actual drinking situations than men, which is supported by prior work showing when prompted to use protective behavioral strategies to reduce alcohol-related harm, women are more likely to do so than men [23].

We found that participants author a significant amount of messages, even though they were not paid explicitly to do so. Compared to expert-authored motivational messages, which were rated the lowest, the highest proportion of peer-authored messages were motivational. This suggests that young adults may perceive someone else trying to motivate them as manipulative, but when they create messages, they are more authentic. It could also suggest that many young adults do not inherently know alcohol facts or strategies to reduce alcohol consumption, but are familiar with motivational statements.

Similar to prior research [11], we found crowdsourcing to be a rapid and effective method for collecting feedback from young adults on expert-authored messages and producing user-generated messages to be used in SMS-delivered alcohol-prevention communication. We were able to capture a significant number of respondents with moderate demographic heterogeneity in a short time, and we were able to ensure the quality of responses using simple survey techniques. The total payment cost for 222 participants was $178.00. Given the iterative nature of mobile health application design and the need to inexpensively get feedback on designs from panels of user types, crowdsourcing could play an important role in allowing rapid innovation. We used these findings to modify our text message intervention by (1) increasing the relative proportion of motivational messages and decreasing the relative proportion of strategy-facilitating messages and (2) incorporating peer-generated messages to be at least 15 % of all messages provided.

The present study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, we did not find universal positive attitudes toward any message. We are not sure it is even possible to achieve universal positive attitudes toward any message regarding reducing drinking in young adults, no matter how good they are, suggesting a possible ceiling effect. Second, we focused only on drinking intentions as an interventional target. Our choice was based on prior work of others showing that intentions mediate alcohol use and binge drinking in young adults [24, 25] and interventions aimed at modifying drinking intentions being effective in reducing alcohol misuse in young adults [26]. Third, our scenarios were staged as dialog in the context of SMS communication; therefore, our findings may not be applicable to other communication delivery modalities. Fourth, we used hypothetical situations related to drinking intentions and assume that young adult preferences reported would be similar if they were actually receiving those text messages. Future studies should collect user-feedback of messages in a real-world setting. Fifth, we only collected ratings regarding instrumental and affective attitudes toward messages. Future studies should examine attitudes across more domains, including the ability of a message to elicit personal reflection. We measured attitudes and not changes in actual drinking behavior. There is a possibility that users may not find certain messages helpful or interesting as a result of having a negative emotional response to them, which could in turn spur them to contemplate change. Future studies should attempt to determine whether there is a linkage between perception of specific messages and actual changes in drinking intentions and/or behaviors. Finally, participants were not explicitly paid to generate messages and likely did not generate more due to a perceived extra burden. In the future, investigators could likely improve quantity and quality of peer-generated message by explicitly paying participants to create them.

Despite these limitations, the current study provides unique and useful information about young adult preferences for text messages aimed at reducing alcohol consumption. Incorporating messages that young adults find helpful and interesting could increase the effectiveness of alcohol-related health communication and, just as importantly, keep users engaged in behavioral interventions over time. This study can also help behavioral researchers and intervention developers to use crowdsourcing to collect user-feedback, which could accelerate iterative development of mobile health communication programs [27].

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This was an investigator-initiated study funded by a grant from the National Institute of Health (NIAAA: K23AA023284). The funders played no role in the design, conduct, or analysis of the study, nor in the interpretation and reporting of the study findings. The researchers were independent from the funders. All authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards

Brian Suffoletto and Jeffrey Kristan declare that they have no conflict of interest. All procedures, including the informed consent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Footnotes

Implications

Practice: Medical and behavioral practitioners should be aware of the differences in instrumental and affective attitudes among young adults toward alcohol prevention messages.

Policy: Resources should be devoted to implementing evidence-based and user-centered mobile interventions.

Research: Online crowdsourcing can be a useful methodology for collecting young adult feedback on behavioral intervention materials and generating peer-authored messages.

References

- 1.Free C, Phillips G, Galli L, Watson L, Felix L, Edwards P, Patel V, Haines A. The effectiveness of mobile-health technology-based health behaviour change or disease management interventions for health care consumers: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2013;10(1):1001362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodgers A. Do u smoke after txt? Results of a randomised trial of smoking cessation using mobile phone text messaging. Tob Control. 2005;14(4):255–261. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.011577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foreman KF, Stockl KM, Le LB, Fisk E, Shah SM, Lew HC, Solow BK, Curtis BS. Impact of a text messaging pilot program on patient medication adherence. Clin Ther. 2012;34(5):1084–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suffoletto B, Callaway C, Kristan J, Kraemer K, Clark DB. Text-message-based drinking assessments and brief interventions for young adults discharged from the emergency department. Alcoholism: Clin. Exp. Res. 2012;36(3):552–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suffoletto B, Kristan J, Callaway CW, Kim KH, Chung T, Monti PM, Clark DB. A text-message alcohol intervention for young adult emergency department patients: a randomized clinical trial. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol. Bull. 2007;133(4):673–693. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Gemert-Pijnen JE, Nijland N, van Limburg M, Ossebaard HC, Kelders SM, Eysenbach G, Seydel ER. A holistic framework to improve the uptake and impact of eHealth technologies. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(4):e111. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreuter MW, Wray RJ. Tailored and targeted health communication: strategies for enhancing information relevance. Am. J. Health Behav. 2003;27(3):227–232. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.27.1.s3.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paolacci G, Chandler J, Ipeirotis PG. Running experiments on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Fuzzy Optim. Decis. Making. 2010;5(5):411–4119. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Behrend TS, Sharek DJ, Meade AW, Wiebe EN. The viability of crowdsourcing for survey research. Behav. Res. Methods. 2011;43(3):800–813. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turner AM, Kirchhoff K, Capurro D. Using crowdsourcing technology for testing multilingual public health promotion materials. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(3):e79. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muench F, van Stolk-Cooke K, Morgenstern J, Kuerbis AN, Markle K. Understanding messaging preferences to inform development of mobile goal-directed behavioral interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(2):e14. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carey KB, Henson JM, Carey MP, Maisto SA. Which heavy drinking college students benefit from a brief motivational intervention? J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2007;75(4):663–669. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Frank D, Kivlahan DR. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcoholism: Clin. Exp. Res. 2007;31(7):1208–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Zhou Y. Effectiveness of the derived alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT-C) in screening for alcohol use disorders and risk drinking in the US general population. Alcoholism: Clin. Exp. Res. 2005;29(5):844–854. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000164374.32229.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991;50:179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychol. Bull. 1992;111:455–474. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coley HL, Sadasivam RS, Williams JH, Volkman JE, Schoenberger YM, Kohler CL, Sobko H, Ray MN, Allison JJ, Ford DE, Gilbert GH, Houston TK, National Dental PBRN and QUITPRIMO Collaborative Group Crowdsourced peer- versus expert-written smoking-cessation messages. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013;45(5):543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walters ST, Bennett ME, Noto JV. Drinking on campus: what do we know about reducing alcohol use among college students? J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2000;19(3):223–228. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(00)00101-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ziemelis A, Bucknam RB, Elfessi AM. Prevention efforts underlying decreases in binge drinking at institutions of higher education. J American College Health. 2002;50(5):238–252. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehto T, Oinas-Kukkonen H. Persuasive features in web-based alcohol and smoking interventions: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e46. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller MB, Leffingwell TR. What do college student drinkers want to know? Student perceptions of alcohol-related feedback. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2013;27(1):214. doi: 10.1037/a0031380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walters ST, Roudsari BS, Vader AM, Harris TR. Correlates of protective behavior utilization among heavy-drinking college students. Addict. Behav. 2007;32:2633–2644. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norman P, Armitage CJ, Quigley C. The theory of planned behavior and binge drinking: assessing the impact of binge drinker prototypes. Addict. Behav. 2007;32(9):1753–1768. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norman P, Conner M. The theory of planned behaviour and binge drinking: assessing the moderating role of past behaviour within the theory of planned behaviour. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2006;11(1):55–70. doi: 10.1348/135910705X43741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hagger MS, Lonsdale A, Chatzisarantis NL. A theory-based intervention to reduce alcohol drinking in excess of guideline limits among undergraduate students. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2012;17(1):18–43. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2010.02011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collins L, Murphy S, Strecher V. The multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) and the sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART) new methods for more potent eHealth interventions. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007;32(5):S112–S118. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]