Abstract

Objective: E-health applications are becoming integral components of general medical care delivery models and emerging for mental health care. Few exist for treatment of those with severe mental illness (SMI). In part, this is due to a lack of models to design such technologies for persons with cognitive impairments and lower technology experience. This study evaluated the effectiveness of an e-health design model for persons with SMI termed the Flat Explicit Design Model (FEDM). Methods: Persons with schizophrenia (n = 38) performed tasks to evaluate the effectiveness of 5 Web site designs: 4 were prominent public Web sites, and 1 was designed according to the FEDM. Linear mixed-effects regression models were used to examine differences in usability between the Web sites. Omnibus tests of between-site differences were conducted, followed by post hoc pairwise comparisons of means to examine specific Web site differences when omnibus tests reached statistical significance. Results: The Web site designed using the FEDM required less time to find information, had a higher success rate, and was rated easier to use and less frustrating than the other Web sites. The home page design of one of the other Web sites provided the best indication to users about a Web site’s contents. The results are consistent with and were used to expand the FEDM. Conclusions: The FEDM provides evidence-based guidelines to design e-health applications for person with SMI, including: minimize an application’s layers or hierarchy, use explicit text, employ navigational memory aids, group hyperlinks in 1 area, and minimize the number of disparate subjects an application addresses.

Key words: Web site, Web site usability, Web site design, schizophrenia, e-mental health

Introduction

E-health applications for physical health care are becoming more common and improving access, convenience, education, care quality, and care effectiveness.1–3 There has been relatively less work creating such applications for mental health treatments, but advances are being made, including for depression and anxiety,4,5 panic/phobic disorders,6 and stress management.7 Severe mental illness (SMI) has received comparatively little work, though there are notable examples.8–11

In part, this is due to a dearth of research to create design models to make these technologies usable by persons with SMI and others with cognitive impairments.12–15 A lack of appropriate design models is a primary cause of poor designs of e-health applications for those with cognitive impairments,16 and will continue to limit the inclusion of, and development of applications for those with SMI. There are numerous guidelines for designing Web sites to support user-directed applications for the general public who do not have special cognitive needs, including those with physical and sensory deficits.17 These guidelines can produce Web sites with many potential barriers for persons with cognitive impairments, including organizing contents around a few high level conceptual modules; requiring navigation of deep hierarchies; requiring interpretation of potentially enigmatic 1- and 2-word long hyperlinks and labels; and requiring users to create accurate mental models of the organization of pages’ and a Web sites’ contents in order to navigate them effectively.18 These standard design models can lead to applications that require a high cognitive effort to navigate and can have quite poor usability for persons with SMI.12

Though there are some guidelines to create e-health applications for those with cognitive impairments, with few exceptions,12,15 they are exclusive of persons with SMI and are frequently based on authors’ speculations, intuitions, and commonsense judgments, with little experimental validation.15 In response, we conducted a series of design and usability studies with persons who have SMI.15 From these, we created an empirically based nascent design model, termed the Flat Explicit Design Model (FEDM), to improve designs for those with SMI.15 This model was used to create a Web-based intervention, termed the Schizophrenia Online Access to Resources (SOAR), to provide multifamily psychoeducational treatment to persons with schizophrenia and their family members, in their homes.11 SOAR proved to be highly usable by persons with SMI, and when compared to usual care, persons with schizophrenia showed a large and significant reduction in positive symptoms and a large and significant increase in knowledge of schizophrenia.

The FEDM (table 1), which now contains 18 design variables, was formulated to reduce the cognitive effort required to effectively use an e-health application by reducing the need for users to: (1) think abstractly, eg, to understand text, via the use of low reading level (table 1 variable #15), simple sentence structure (table 1 variable #5), reduced wordiness (table 1 variable #17), and familiar vocabulary (table 1 variable #16); or to interpret hyperlinks and labels, via the use of explicit vs inferential phrasing (table 1 variable #6); (2) rely on working memory to create a “mental model” of an application, eg, by reducing the levels or hierarchy of an application (table 1 variable #1), using memory aids such as pop-up menus (table 1 variable #3), and having more focused content (table 1 variable #18); (3) utilize executive functions to search for information and to explore an application effectively, eg, by reducing the functional separation between navigation and content pages (table 1 variable #9), employing a shallow Web site hierarchy (table 1 variable #1) that places all content just one-page or “click” from the home page, emphasizing scrolling vs paging (table 1 variable #7), and utilizing a single constant navigational toolbar (table 1 variable #8); (4) concentrate to filter out distracting contents, via minimal superfluous content, images, and designs (table 1 variable #4); and (5) scan and search for information on a page or screen, via a simplified page layout design (table 1 variables #2, #4, #10, #12, #13, #14), and covering fewer disparate topics (table 1 variable #18).

Table 1.

Critical Design Characteristics of the Flat Explicit Design Model

| 1. Shallow | Hierarchy should have minimal depth, one level past initial page or screen is best. Schizophrenia Online Access to Resources (SOAR) is mainly one page deep, ie, one page beyond the home page. This is accomplished by listing all categories of the Web site’s resources on the home page, then, by employing a unique pop-up menu structure a user can survey each of the 12 or so resources in the pop-up menu for a given category and choose a resource without leaving the home page. Navigating only one-page reduces the chances that a user might become “lost” or disoriented. |

| 2. Introduction | Minimal content (eg, introductory text) prior to the hyperlinks that lead to an application’s content. |

| 3. Memory aids | Memory aids (eg, pop-up menus) should be used to facilitate navigation and flatten the hierarchy. |

| 4. Plain | Given the potential vulnerability to overstimulation, pages should avoid distracting and superfluous content (eg, bright colors, icons, and graphics). |

| 5. Inference | Minimal need to think abstractly to understand the written content of the application, eg, simple sentence and composition structure should be employed. |

| 6. Explicit | Navigational elements should not need interpretation to understand (eg, hyperlinks, icons, headings, and labels) but should use explicit wording. If 1 or 2 words for a hyperlink or label is not explicit, long phrases are better (eg, SOAR has hyperlinks with up to 19 words), which provide more information and require less interpretation on the part of users. |

| 7. Scrolling | Emphasis should be placed on scrolling down a page for additional content vs paging, going to another page or screen. |

| 8. Toolbar | Use of a single constant navigational tool bar should improve comprehension and navigation. |

| 9. Organization | Grouping of contents (eg, on the home page) should be accomplished using categories or modules that are less abstract, closer conceptually to final destination content, and thus more numerous hyperlink categories should be placed on a home page. Thus, each module or hyperlink on the home page takes a user to a smaller amount of relatively focused content. |

| 10. Navigation areas | Hyperlinks to additional content should be located in a minimal number of locations on a page or screen, preferably in on location or navigational area on a page. In these areas, more hyperlinks to contents should be provided vs less to decrease the number of pages a user must navigate. |

| 11. Hyperlinks | In navigation areas, more hyperlinks to contents should be provided vs less to decrease the number of navigation areas and/or pages a user must navigate. |

| 12. Topic areas | Page contents should be organized using minimal independent topic areas. |

| 13. Arrangement | A simple geometry, employing a single column, is potentially best to present page contents. |

| 14. Location | Hyperlinks to primary contents should be placed in the upper left of a page, where users begin searching a page. |

| 15. Reading level | Low reading level should be used. |

| 16. Dialect | The target group’s vocabulary should be used to create contents. |

| 17. Text quantity | Minimal amounts of total text should be used but adequate to convey concepts without the need to interpret meaning. |

| 18. Themes | A limited number of disparate themes are presented. |

To further evaluate this design model and gain additional insights into the design needs of persons with SMI, we compared the usability and design of the SOAR intervention Web site to 4 publicly available Web sites that also provided information on schizophrenia. We present here the results from this comparison and discuss implications of the findings for e-health technology design. This study focused on persons with psychotic disorders. Prior and ongoing studies include persons with a broader range of SMI diagnoses; thus, we believe these results are more broadly relevant to SMI.

Methods

Choice of Web Sites for Evaluation

Five Web sites that included information on schizophrenia were chosen for evaluation. Web sites were identified using Google (www.google.com) to search for the word schizophrenia and by searching the Google Web site directory for Web sites addressing schizophrenia. The Web sites were chosen to represent a range of variation on important design variables. Web sites www.schizophrenia.com and www.nami.org were the most prominent, ie, first, Web sites returned from either a Google search or directory listing for schizophrenia. The Web site www.chovil.com was the only Web site in the top 10 results that was written by a person with schizophrenia and thus may pose distinctive design insights. The Web site www.nmha.org represents a large national mental health organization catering to individuals with mental illness. The fifth Web site, SOAR,11 we developed to deliver family psychoeducational therapy using a design model specifically created to improve the usability of e-health applications for persons with SMI. Its address is not presented because it is currently under study. All Web sites were downloaded and cached locally to ensure that their contents remained static throughout the study.

The Designs of the 5 Web Sites

The 5 Web sites are characterized using the FEDM design model (table 2). This was accomplished by 2 experts (authors A.J.R. and M.B.S.) independently rating each Web site and then coming to consensus on any differences in their ratings.

Table 2.

Design Characteristics of the 5 Tested Mental Health Web Sites

| Design Variable | Web Site | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOAR | SZ | Chovil | NAMI | NMHA | |

| Shallow | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Introduction | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Memory aids | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Plain | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Inference | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Explicit | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Scrolling | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Toolbar | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Organization | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Navigation areas | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Hyperlinks | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Topic areas | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Arrangement | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Location | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Reading level | No | No | No | No | No |

| Dialect | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Text quantity | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Themes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

Note: NAMI, National Alliance for the Mentally Ill; NMHA, National Mental Health Association; Chovil, Chovil.com; SOAR, Schizophrenia Online Access to Resources; SZ, Schizophrenia.com.

Web Site Evaluation Procedures

Participants were asked to complete a series of tasks and subjectively evaluate each Web site’s usability. To control for learning that might occur as subjects were tested on successive Web sites, their order was varied across participants using a 5 × 5 Latin square design. Likewise, the individual tasks for each of the 2 types of tasks were varied across individual Web sites. Timing of tasks was conducted internally and unobtrusively by the computer for accuracy and to minimize the influence on participants of being timed. If the time allotted to complete an individual task expired, the computer screen would automatically blank, and the researcher would direct the participant to the next task. Finally, to minimize testing anxiety, each participant was read a standardized script explaining that the testing was an evaluation of the Web sites and not the participants and that there were no right or wrong answers.

Web site testing was conducted using ergoBrowser (www.ergolabs.com), a software program for recording and timing Web site navigation during usability testing. This program is a simple variation of the Microsoft Internet Explorer Web browser, which ensures that pages rendered by ergoBrowser and Internet Explorer look and behave the same. The software has a similar interface to Internet Explorer and other popular Web browsers.

Tasks to Evaluate Web Site Usability

Find Specific Information.

To assess the ability to navigate each Web site, participants were asked to find information on 3 topics: (1) treatments for schizophrenia, (2) side effects of medications used to treat schizophrenia, and (3) the causes of schizophrenia. Participants were given up to 5 minutes to find the information on each topic. Once a search was over, participants were returned to the home page to begin the next search. The time it took and whether it was found were automatically recorded.

Effectiveness of a Home Page’s Content Disclosure.

To assess the effectiveness with which a home page conveys information about a Web site’s contents (ie, what a Web site does and does not contain), what we term the content disclosure of a home page, participants were asked to study a home page for 60 seconds and then to decide whether they thought (yes/no) a Web site contained information on each of 7 topics (eg, how schizophrenia is treated and the side effects of medications). Participants were able to use the mouse to move the scroll bar to view the entire home page but were not able to use the mouse to explore the home page (eg, open pull-down menus). To assess the ability of the home pages to convey information about both what a Web site does and does not contain, the topics were chosen so that 2 of the 7 were not covered on each Web site.

Web Site Impressions.

Following testing on a Web site, participants provided their impressions of the Web site using 2 standard usability evaluation statements: the Web site was (1) easy to use and (2) frustrating to use. These were evaluated using a 5-point subjective rating scale ranging from 1 (“Not at all”) to 5 (“Extremely”).

Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted using linear mixed-effects regression models to examine differences in usability metrics between each of the study Web sites and logistic regression models to examine differences in dichotomous outcomes. Omnibus tests of between-site differences were first conducted, followed by post hoc pairwise comparisons across Web site when omnibus tests reached statistical significance. The mixed-effects models accounted for the dependent nature of participants’ responses to multiple Web sites. In order to meet assumptions of normality, time was analyzed using the log of the time. The computer’s automatic task timing mechanism did not function properly for 5 subjects during the tasks to find information. Otherwise missing data were minimal with only one subject missing data from one Web site. Imputation of missing data was not required. In addition to the comparisons of mean times, we compared time to completion of the tasks with log-rank (LR) statistics.

Participants

Participants were recruited from 6 community mental health outpatient psychiatric rehabilitation centers. Enrollment criteria were age ≥18 years; diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, American Psychiatric Association, 1994); physically able to read the screen of a computer and use a mouse; and able to read at a fifth-grade level. Participants’ background characteristics are described in table 3. There were no requirements for prior computer or Internet use. The research protocol for this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (University of Pittsburgh).

Table 3.

Participant Characteristics (n = 38)

| Variable | n | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 19 | 50 |

| Age (y)a | ||

| 31–40 | 6 | 15.8 |

| 41–50 | 23 | 60.5 |

| 51–59 | 9 | 23.7 |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 22 | 57.9 |

| African American, Black | 15 | 39.5 |

| Asian | 1 | 2.6 |

| Education | ||

| <High school | 6 | 15.8 |

| High school | 12 | 31.6 |

| Some college/vocational school | 14 | 36.8 |

| College graduate | 6 | 15.8 |

| Overall level of functioning (GAS)a | ||

| <60 | 13 | 35.1 |

| 60–69 | 18 | 48.7 |

| 70–81 | 6 | 16.2 |

| Computer accessa | ||

| At home | 10 | 26.3 |

| Other than home | 10 | 29.0 |

| No access | 17 | 44.7 |

| Hours of computer use/week | ||

| None | 17 | 44.7 |

| 1–5 | 13 | 34.2 |

| >5 | 8 | 21.0 |

| Previously accessed Web sites | ||

| Yes | 19 | 50.0 |

| Previously played computer games | 19 | 50.0 |

Note: GAS, Global Assessment Scale.

aData were missing for 1 subject.

Participant Background Information and Level of Functioning

The researchers administered a questionnaire that collected background information from each participant. They also used the Global Assessment Scale (GAS)19 to rate each participant’s level of functioning.

Participant Training

To ensure that all participants had the basic skills needed to navigate the 5 Web sites, each participant, regardless of background, was taken through a brief tutorial (covering topics such as mouse use, hyperlink text, navigation buttons, pop-up menus, scrolling down a page) using 3 preselected publicly available Web sites. Training, based on tutorials we have used in previous studies,20,21 was provided until each participant demonstrated mastery of the skills needed to navigate the Web sites, which lasted up to 22 minutes. All who met eligibility criteria were able to master these basic skills.

Results

Participants had a mean age of 42.7 (SD = 6.62), 19 (50%) were female, and 15 (40%) were African American/Black. Twenty-one participants had used a computer (55%). Computers were available to 20 (54%) with 10 (27%) having home access and 10 (27%) having access only outside the home.

Web Site Navigation to Find Content: Time and Accuracy

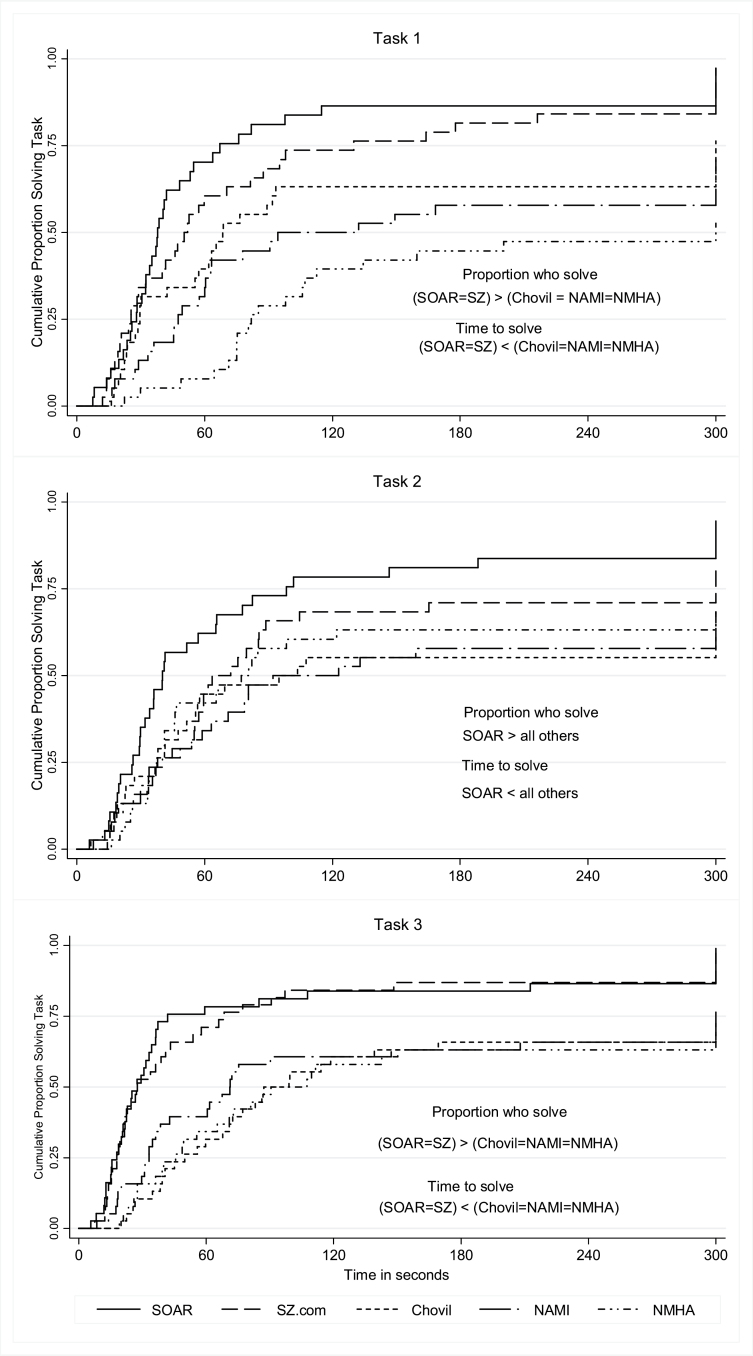

The average time spent searching for information on each site was SOAR (61 ± 41 s), Schizophrenia.com (84 ± 49 s), Chovil (142 ± 94 s, National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI; 143 ± 101 s), and National Mental Health Association (NMHA; 158 ± 80 s). Participants were more successful finding the targeted information (figure 1) with SOAR (for task 2), or SOAR and Schizophrenia.com (for tasks 1 and 3). For tasks completed successfully, participants spent the least amount of time finding the targeted information with SOAR and Schizophrenia.com (table 4). Participants spent less time searching for information using SOAR (for task 2, figure 1), or SOAR and Schizophrenia.com (for tasks 1 and 3). Comparisons of time searching for information with the LR chi-square tests indicated that there were differences among the Web sites for the 3 tasks (task 1, LR = 38.7, P = .000; task 2, LR = 12.2, P = .02; task 3, LR = 34.9, P = .000).

Fig. 1.

Finding information.

Table 4.

Task Performance Across the 5 Web Sites

| Correctly Find Information on Web Site | Web Site | Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOAR | SZ | Chovil | NAMI | NMHA | |||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | χ2, P | Post Hoc Testsa | |

| Total correct out of 3 (SD) | 2.89 (0.39) | 2.79 (0.41) | 2.18 (0.98) | 2.16 (1.08) | 1.89 (1.03) | 15.37, <.001 | A = B; E = C; A, B > C, D, E; D > E (0.05); C > D (0.08) |

| Range | 1–3 | 2–3 | 0–3 | 0–3 | 0–3 | ||

| Time spent on task (includes those who did not solve a task correctly and timed out at 300 s) | |||||||

| n = 33 | n = 33 | n = 33 | n = 33 | n = 33 | |||

| Task 1 | 49 (51) | 66 (65) | 116 (117) | 142(118) | 186 (111) | 52.87, .000 | A = B; E > A, B, C, D; A, B < C, D, E |

| Task 2 | 61 (64) | 101 (100) | 138 (127) | 139(120) | 119 (115) | 10.49, .03 | A < B, C, D, E; B = C = D = E |

| Task 3 | 35 (38) | 37 (31) | 124(103) | 113 (114) | 120 (109) | 44.76, .000 | A = B; C = D = E; A, B < C, D, E |

| Time for only those tasks solved correctly (in seconds) | |||||||

| n = 32 | n = 32 | n = 24 | n = 22 | n = 18 | |||

| Task 1 | 41 (25) | 58 (51) | 47 (26) | 63 (42) | 90 (43) | 21.70, <.0002 | A = B = C = D; E > A, B, C, D |

| n = 31 | n = 27 | n = 21 | n = 22 | n = 24 | |||

| Task 2 | 49 (40) | 57 (33) | 45 (29) | 58 (41) | 51 (27) | 3.19, .53 | |

| n = 32 | n = 32 | n = 25 | n = 25 | n = 24 | |||

| Task 3 | 35 (39) | 37 (31) | 70 (39) | 53 (45) | 64 (38) | 35.84, <.0001 | A = B; C = E; C > D; A, B < C, D, E |

| Content disclosure: predicting Web site contents from home page visual inspection | |||||||

| M (range) | M (range) | M (range) | M (range) | M (range) | |||

| Content disclosure: number correctly judged out of 7 (range) | 5.12 (3–7) | 5.41 (4–6) | 4.61 (3–6) | 4.05 (1–6) | 3.92 (1–7) | 61.85, <.000 | A = B; C = D; D = E; C > E; A, B > C, D, E |

| Subjective reaction to Web site | |||||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Easy to useb | 4.01 (0.89) | 3.63 (0.99) | 2.73 (1.12) | 3.03 (1.28) | 2.84 (1.01) | 61.12, <.0001 | A > B, C, D, E; B > C, D, E |

| Frustratingc | 1.58 (0.78) | 1.60 (0.87) | 2.19 (1.22) | 2.08 (1.23) | 2.35 (1.23) | 32.19, <.001 | A = B < C, D, E; B < D, E |

Note: Abbreviations are explained in the first footnote to table 2.

aBased on pairwise comparisons using Hochberg’s adjustment for multiple comparisons.

bHigher values indicate more easy to use (1–5 scale).

cHigher values indicate more frustrating to use (1–5 scale).

Subjective Evaluations of Each Web Site

Participants rated SOAR the easiest to use and Schizophrenia.com next easiest (table 4). The remaining 3 Web sites all obtaining lower ratings and statistically not different from each other. Rated as the most frustrating Web sites to use were NMHA, NAMI, and Chovil, with the least frustrating being SOAR and Schizophrenia.com, which were statistically not different from each other.

Web Site Home Page Content Disclosure

The ability of participants to accurately judge or predict the contents of a Web site based solely on viewing the home page (table 4) was best for Schizophrenia.com (77%) and SOAR (73%), followed by Chovil.com (66%).

Correlates of Performance Measures: Demographic, Computer Use, and Global Functioning

Performance as assessed by any of our measures was not significantly related to any of the demographic measures nor the GAS score. Previous experience with using Web sites but not with computer games decreased the mean time taken to complete a task by an average of 16.5 seconds (95% CI = 0.6, −32.4, P = .005).

Discussion

There has been a dearth of research on designing e-health applications for use by persons with SMI and others with cognitive impairments.14 As a result, even though there are a growing number of e-applications, their designs may not be effective for persons with SMI.12,15 Without models to design technologies for those with special cognitive needs, these users may be unable to participate in emerging e-health care delivery models. The results presented here indicate that there are clear differences in the effectiveness of designs for persons with schizophrenia and, further, that design models can be developed to increase usability.

When evaluated for the ability to find information and the time to find information, SOAR appears to have the best design model, Schizophrenia.com next, and Chovil.com third. There are several design differences that likely contributed to differences in Web site performances, including SOAR having its hyperlinks at the top of the page, even before introductory text; using explicit hyperlink wording, the most explicit wording of the tested Web sites; employing memory aids for navigation; having a single constant navigational toolbar that reduced the chances of getting lost; having a single navigation area; and having 2 topic areas, the fewest of the tested Web sites.

Though the designs of these 3 Web sites have important differences, they have several commonalities that likely contributed to their superior performance. All 3 have a shallow hierarchy, have little or no distracting and/or superfluous content, rely on scrolling vs paging to provide more hyperlinks to the application’s contents, employ less abstract concepts to organize contents on the home page, and use relatively explicit hyperlink labels. In addition, the information targeted in these tasks was in 1 area on the home page, and the Web sites focused on a single illness, schizophrenia. However, in the Schizophrenia.com home page design, contents and information were presented in several columns, groups of hyperlinks were located in several locations on the page, and it contained images, which are all different than the home page design for SOAR and appear to be less appropriate for persons with SMI. In Chovil.com, the hyperlinks were in 1 location on the home page, but unlike SOAR, they were separated into 2 columns, each column was divided into 3 sections, and as is described below, there was a large amount of text prior to these hyperlinks on the home page. These characteristics of Chovil.com are less appropriate for persons with SMI. But having hyperlinks to the schizophrenia content in 1 general location on the home page and having a single illness focus are likely 2 of the design features that contributed to the relatively superior performance of these 3 Web sites over the other 2. In the other 2 Web sites, many illnesses and themes were addressed on the home page other than schizophrenia, and the hyperlinks to information were scattered across many locations. As a result, the page designs were more complex and required more cognitive effort to understand and use.

The ability of a home page to convey information to users about a Web site’s contents we termed a home page’s content disclosure. The better the disclosure of an application’s contents that a home page design can provide to users, the easier it will be for users to decide if a Web site will meet their needs, and to find and thus use a Web site. A Web site may have dozens, hundreds, or even millions of pages.22 Without an effective home page design, the need to search through a Web site to understand and find its contents could prove an insurmountable challenge, especially for persons with schizophrenia and others with cognitive impairments. Three design characteristics are likely to have contributed to the superior performance of Schizophrenia.com on the content disclosure task: the 24 hyperlinks to the primary information on schizophrenia in the Web site were grouped together in 1 location; they were near the top of the home page, which would reduce the searching required to find them; and they were well labeled to be hyperlinks about schizophrenia. The home page of Schizophrenia.com was designed with 3 columns of information, and these hyperlinks were located in the middle column. This location is close to the top left of the page, which our model would indicate is an even better location because this is where one often begins to search through a page.

SOAR, which performed the second best on the disclosure task, also had the hyperlinks to its primary information on schizophrenia grouped together and near the top of the home page. However, in SOAR’s design, the page was simpler, using only a single column of contents to display these 10 hyperlinks. As one moved the mouse over each of these hyperlinks (ie, “mouse-over”), a list of hyperlinks to final destination contents popped up to the right. Thus, by using the mouse, one could see hyperlinks to virtually all the contents of SOAR. However, if one was not able to move the mouse over the page, but only use it to move the scroll bar, as was the case during the content disclosure task, this additional information available on SOAR’s home page would not be seen, and more information would be revealed about the contents of Schizophrenia.com than about SOAR. This additional information available from mere visual inspection was likely an advantageous design characteristic for this task.

In comparison to the remaining 3 Web sites, none had their hyperlinks to schizophrenia information near the top of the home page. The importance of information being placed near the top of the page is consistent with the relatively poorer performance of Chovil.com. Even though this design had all of its hyperlinks to schizophrenia information on the home page grouped in 1 location, and there were more than 30 hyperlinks, a larger number than Schizophrenia.com or SOAR, there were 4 paragraphs of text before one was able to view these hyperlinks, this is about a full screen/page or more long (depending on monitor size). This was likely one barrier to the effectiveness of this design. For this task, Schizophrenia.com had at least 1 design advantage over SOAR, and these 2 Web sites potentially had several over the other 3 Web sites in the evaluation.

The NAMI and NMHA Web sites had the fewest correct content disclosure judgments across the participants; were the only Web sites receiving judgments that none of the information was present; and were the only Web sites where overall, users underestimated the presence of information on the Web site. The diversity of illnesses and topics covered, and the complexity of their designs likely caused significant impediments to understanding and navigating these Web sites. Participants’ subjective impressions of the 5 Web sites were in line with their performance on tasks. The more usable Web sites were judged to be superior as well.

There are several elements of the FEDM that can be in conflict. For example, while a prescription is to use minimal text, it also indicates that more information should be placed on a screen to prevent the need to navigate to another screen and, instead, have users scroll down a screen. We believe that scrolling for more information is not optimal, but far better than navigating to another page. In this same vein, it is better to present more hyperlinks on a given topic than fewer, if fewer leads to additional navigation, and hyperlinks and headings should be explicit, which often requires the use of more text. There are clearly design trade-offs that must be made between these variables. We hypothesize, based on our observations, that all else being equal, navigation is potentially the variable with the single most important effect on usability. That is, the more user-directed navigation required, the less usable an application will be. The difficulty here is to reduce the need to navigate while still creating a design that incorporates the other prescriptions and is relatively simple.

Not surprisingly, those with experience using Web sites took less time to complete tasks. However, much of the time effect was because they successfully completed more of the tasks, whereas those without experience using Web sites, more frequently could not find the target information in the allotted time or gave up and were assigned the maximum search time allowed. Thus, Web site use experience influenced participants’ ability to complete tasks; however, their experience with computers and GAS score did not.

Conclusions

There has been a dearth of work to create models for designing Web sites to be accessible to persons with SMI and cognitive impairments. Adding to previous work, several components to our design model were reinforced or can be put forward based on these findings. To be more accessible to those with SMI, home pages, and navigation pages in general, should have (1) a single illness or topic focus, or at least have the hyperlinks for a given illness or topic grouped together in one area of a screen; (2) the hyperlinks to contents be as prominent as possible, eg, being at or near the top left of a page, and well labeled; (3) minimal content on a page prior to the hyperlinks to contents (eg, introductory text); (4) the number of hyperlinks on a page about a given illness or topic be more numerous and potentially requiring use of the scroll bar to see all contents, rather than less—the latter utilizes a progressive disclosure approach that provides only a few hyperlinks to major topic areas on a page and requires users to progressively navigate through successive pages to obtain final destination contents; (5) the text of hyperlinks as explicit as possible; and (6) the hyperlinks for a given illness or topic placed together in a single column.

Together, these results indicate that when specific design considerations are implemented, Web sites, and likely other e-health applications, will be appropriate for use by persons with SMI. By creating designs that can reduce the cognitive effort required to use e-health applications, usability can be greatly improved for this population with the potential for marked impact on both mental and traditional physical health outcomes.

Funding

National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH63484); Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Rehabilitation Research and Development Service (D6180R), and VA VISN4 Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center.

Acknowledgment

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. Brattberg G. Internet-based rehabilitation for individuals with chronic pain and burnout II: a long-term follow-up. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;30:231–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bond GE, Burr R, Wolf FM, Price M, McCurry SM, Teri L. The effects of a web-based intervention on the physical outcomes associated with diabetes among adults age 60 and older: a randomized trial. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2007;9:52–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Muñoz RF, Barrera AZ, Delucchi K, Penilla C, Torres LD, Pérez-Stable EJ. International Spanish/English Internet smoking cessation trial yields 20% abstinence rates at 1 year. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:1025–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cavanagh K, Shapiro DA, Van Den Berg S, Swain S, Barkham M, Proudfoot J. The effectiveness of computerized cognitive behavioural therapy in routine care. Br J Clin Psychol. 2006;45:499–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Korten AE, Brittliffe K, Groves C. A comparison of changes in anxiety and depression symptoms of spontaneous users and trial participants of a cognitive behavior therapy website. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. MacGregor AD, Hayward L, Peck DF, Wilkes P. Empirically grounded clinical interventions clients’ and referrers’ perceptions of computer-guided CBT (FearFighter). Behav Cogn Psychother. 2009;37:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hasson D, Anderberg UM, Theorell T, Arnetz BB. Psychophysiological effects of a web-based stress management system: a prospective, randomized controlled intervention study of IT and media workers. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mobile assessment and therapy for schizophrenia (MATS): platform construction, feasibility, and outcomes. Paper session presentation at the 2nd biennial conference of the Society for Ambulatory Assessment (SAA); 2011; Ann Arbor, MI. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ferron JC, Brunette MF, McHugo GJ, Devitt TS, Martin WM, Drake RE. Developing a quit smoking website that is usable by people with severe mental illnesses. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2011;35:111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Granholm E, Ben-Zeev D, Link PC, Bradshaw KR, Holden JL. Mobile Assessment and Treatment for Schizophrenia (MATS): a pilot trial of an interactive text-messaging intervention for medication adherence, socialization, and auditory hallucinations. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:414–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rotondi AJ, Anderson CM, Haas GL, et al. Web-based psychoeducational intervention for persons with schizophrenia and their supporters: one-year outcomes. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:1099–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brunette MF, Ferron JD, Santos M, et al. Smoking cessation websites do not meet usability guidelines or content needs of people with severe mental illness. Health Educ Res. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bulger JR. A usability study of mental health websites with an emphasis on homepage design: performance and preferences of those with anxiety disorders [master’s thesis]. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Edwards ADN. Extra ordinary computer interaction: interfaces for users with disabilities. In: Edwards ADN, ed. Computers and People with Disabilities. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1995:19–43. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rotondi AJ, Sinkule J, Haas GL, et al. Designing websites for persons with cognitive deficits: design and usability of a psychoeducational intervention for persons with severe mental illness. Psychol Serv. 2007;4:202–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Depp CA, Mausbach B, Granholm E, et al. Mobile interventions for severe mental illness: design and preliminary data from three approaches. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198:715–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koyani SJ, Bailey RW, Nall JR. Research-based web design and usability guidelines National Cancer Institute, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2003. http://usability.gov/pdfs/guidelines_book.pdf Accessed March 12, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dalal NP, Quible Z, Wyatt K. Cognitive design of home pages: an experimetal study of comprehension on the World Wide Web. Inform Process Manage. 2000;36:607–621. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The global assessment scale. A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:766–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rotondi AJ, Sinkule J, Spring M. An interactive Web-based intervention for persons with TBI and their families: use and evaluation by female significant others. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2005;20:173–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rotondi AJ, Haas GL, Anderson CM, et al. A clinical trial to test the feasibility of a telehealth psychoeducational intervention for persons with schizophrenia and their families: intervention and three-month findings. Rehabil Psychol. 2005;50:325–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. More than 2 million amazing BBC pages BBC Homepage; 2005. http://www.bbc.co.uk/ Accessed March 14, 2005. [Google Scholar]