Abstract

Background

Low-grade gangliogliomas/gangliocytomas (GG) are rare tumors of the CNS, which occur mostly in young people. Due to their rarity, large-scale, population-based studies focusing on epidemiology and outcomes are lacking.

Objective

To use the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) datasets of the National Cancer Institute to study demographics, tumor location, initial treatment, and outcome data on low-grade GG in children.

Methods

SEER-STAT v8.1.2 identified all patients aged 0-19 years in the SEER datasets with low-grade GGs. Using the Kaplan-Meier method and Cox proportional hazard regression, we examined associations between these characteristics and survival.

Results

There were 348 children with low-grade GG diagnosed from 2004-2010, with a median follow-up of 37 months. Tumors were more prevalent in males (n=208, 59.8%) than females (n=140, 40.2%) (p<0.001). Almost 63% percent occurred in children >10 years, while only 3.5% were found in those <1 year old. Approximately 50% were located in the temporal lobes, while only 3.7% and 3.5% were located in the brainstem and spinal cord, respectively. Surgery was performed on 91.6% of cases, with gross total resection (GTR) achieved in 68.3%. Radiation was used in 3.2%. Young age (<1yrs) and brainstem location were associated with worse overall survival (OS).

Conclusion

This study shows that low-grade GG occur in older children with a male preference. GTR is achieved in the majority of cases, and radiation is rarely used. While the majority of patients have an excellent prognosis, infants and patients with brainstem tumors have worse survival rates.

Keywords: Demographics, Low-grade ganglioglioma/gangliocytoma, Outcomes, SEER, Treatment

Introduction

Low-grade GG are rare, well-differentiated, glial-neural tumors that account for only 0.5% of all CNS tumors, and 1-5% of all pediatric CNS tumors1-4. Indeed, they are thought to be tumors of young people, with most studies reporting mean or median ages anywhere from 8-26 years1. While the majority occur in the temporal lobes, causing epilepsy5, they occur throughout the CNS, including the brainstem and spinal cord1;2;6-10. These latter lesions may present with varied neurological signs/symptoms, including cranial nerve deficits, focal weakness and hydrocephalus7;8;11;12. In general, supratentorial low-grade GG are thought to be very benign lesions, with good prognosis being associated with temporal location, epilepsy, and GTR6;9;10;13. Due to their rarity, the epidemiology and factors affecting outcome are poorly understood.

The U.S. National Cancer Institute's SEER datasets represent approximately 28% of the US population14 and include data on patient demographics, primary tumor site, treatment information, as well as patient survival data,15 thereby making them a useful resource for studying rare tumors16. We used SEER to study low-grade GG in patients aged 0-19 years and, in particular, to investigate associations between patient and treatment characteristics and survival. We hypothesized that demographic, and treatment factors affect survival for children with low-grade GG, and based on our clinical experience, that brainstem tumors would have a worse outcome than others GG.

Methods

The sample frame was identified from the most recent SEER datasets (Incidence-SEER 18 Regs Research Data + Hurricane Katrina Impacted Louisiana Cases, Nov 2012 Sub (1973-2010 varying)14. We included patients with age <20 years and ICD-O-3 diagnosis codes 9505/0 (Ganglioglioma) and 9492/0 (Gangliocytoma), diagnosed from January 1, 2004 – December 31, 2010. Anaplastic ganglioglioma (9505/3), and desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma/ganglioglioma (9412/1) were excluded from this study. The primary outcome was OS, defined as the number of months from the date of diagnosis to the date of last follow-up or death. Cause-specific survival was also examined. Data collected for each subject included gender, race, age at diagnosis, anatomical location, extent of surgical resection, use of radiation therapy, OS, and cause-specific survival. SEER does not contain data regarding treatment with chemotherapy17.

For most analyses we categorized age as <1, 1-4, 5-9, 10-14, and 15-19 years. Due to small numbers we dichotomized age into <1 vs “other age” to examine cause-specific survival. Race was dichotomized as “white” and “non-white”. Tumor location was recorded in SEER in 14 categories corresponding to the various lobes of the brain, as well as cerebrum, cerebellum, brainstem, spinal cord, cerebral meninges, ventricles, optic nerves, brain-not otherwise specified (NOS), and overlapping lesion of the brain. The extent of surgical resection was divided into three groups: subtotal resection (STR), GTR, and no surgery (none), based on SEER site-specific coding guidelines18. The STR group included patients with surgical codes 20 (local excision of tumor, lesion, or mass, excisional biopsy, or stereotactic biopsy of the brain), 21 (subtotal resection of tumor, lesion or mass, NOS), 22 (partial resection of tumor, lesion, or mass), and 27 (excisional biopsy), while the GTR group included patients with surgical codes 30 (radical, total, gross resection of tumor, lesion or mass in brain), 40 (partial resection of lobe of brain, when the surgery cannot be coded as 20-30), and 55 (gross total resection of lobe of brain (lobectomy)18. These definitions have been used by us and others previously for SEER dataset analysis 19;20. Two cases with surgical codes 90 (surgery, NOS) and 99 (unknown if cancer-directed surgery performed; death certificate only), respectively, were excluded from the analysis.

For survival analysis, overall and cause-specific survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. For the purpose of univariate survival analysis, we categorized location as “brainstem”, “spinal cord”, and “other”. For variables found to be associated with survival, we also performed 5-year relative survival analysis. Proportional hazards ratios were estimated using Cox regression analysis. The assumption of proportionality was visually assessed using log-log survival plots and by testing the statistical significance of time dependent covariates. Relative survival was calculated using the Actuarial method. Finally, we compared survival of brainstem GG to other GG in terms of age at diagnosis, gender, use of radiation, and extent of resection. SEER*STAT v8.1.2 was used to extract case-level data21. SAS v9.2 and SEER*STAT v8.1.2 were used for data analyses. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Findings from SEER were compared to the previously published literature. Relevant reports were found through a review of the English language articles in the PubMed database using the search terms “low-grade ganglioglioma”, “ganglioglioma”, or “gangliocytoma” in combination with one or more of the following search terms: “treatment”, “clinical outcomes”, “demographics”, and “pediatric”. The first author screened all abstracts and selected articles for full review. The references for each article were further reviewed to identify other relevant articles.

Results

We identified 348 children who were diagnosed with low-grade GG between 2004 and 2010. Of the total population, 59.8% (208/348) were male, producing a male to female ratio of almost 1.5:1.0 (Table 1). Eighty-three percent (282/341) were “white”. The mean and median ages at diagnosis were 10.9 and 12.0 years, respectively, with 62.9% (219/348) being older than 10 years of age, and 3.5% (12/348) younger than 1 year of age (Table 1, Fig 1). Regarding anatomical location, 47.4% (165/348) of patients had temporal lobe tumors (Table 2). The next most frequent locations were the frontal lobe, parietal lobe, and cerebellum at 10.3% (36/348), 8.9% (31/348), and 6.3% (22/348), respectively. Brainstem and spinal cord tumors occurred in 3.7% (13/348) and 3.5% (12/348) of patients, respectively. The least common locations were the cerebral meninges and pituitary gland, with only one such tumor (0.3%) found in each of these sites. GTR was achieved in 68.3% (235/344), STR in 23.3% (80/334), and 8.4% (29/344) of patients did not have surgery. Those patients who did not have surgery were diagnosed by imaging alone or at autopsy. Radiation treatment was used in 3.2% (11/345) of patients.

Table 1. Univariate analysis of demographics & treatments of pediatric patients with low-grade gangliogliomas/gangliocytomas, 2004-2010 (n=348).

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 208 | 59.8 |

| Female | 140 | 40.2 |

| Age (yrs) | ||

| 0 | 12 | 3.5 |

| 1-4 | 49 | 14.1 |

| 5-9 | 68 | 19.5 |

| 10-14 | 110 | 31.6 |

| 15-19 | 109 | 31.3 |

| Race (n=341) | ||

| White | 282 | 82.7 |

| Other | 59 | 17.3 |

| Extent of Resection (n=344) | ||

| GTR | 235 | 68.3 |

| STR | 80 | 23.3 |

| No Surgery | 29 | 8.4 |

| Radiation Treatment (n=345) | ||

| No Radiation | 334 | 96.8 |

| Beam Radiation | 11 | 3.2 |

| Vital status | ||

| Alive | 339 | 97.4 |

| Dead | 9 | 2.6 |

Figure 1.

Age distribution of 348 children with low-grade gangliogliomas/gangliocytomas from the SEER datasets (2004-2010).

Table 2. Anatomical location of pediatric low grade gangliogliomas/gangliocytomas, 2004-2010 (n=348).

| Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal lobe | 165 | 47.41 |

| Frontal lobe | 36 | 10.34 |

| Parietal lobe | 31 | 8.91 |

| Cerebellum, NOS | 22 | 6.32 |

| Overlapping lesion of brain | 15 | 4.31 |

| Occipital lobe | 15 | 4.31 |

| Brainstem | 13 | 3.74 |

| Ventricle, NOS | 13 | 3.74 |

| Brain, NOS | 12 | 3.45 |

| Spinal cord | 12 | 3.45 |

| Cerebrum | 10 | 2.87 |

| Optic nerve | 2 | 0.57 |

| Cerebral meninges | 1 | 0.29 |

| Pituitary gland | 1 | 0.29 |

| Total | 348 | 100 |

Very young age at diagnosis (<1year) and brainstem location were associated with worse OS (p≤0.01 for both) (Table 3). These findings were confirmed by proportional hazard ratio estimated using cox regression analysis (HR=31.4, 95% CI=2.8-351.4, and HR=8.2, 95% CI=1.7-39.5, respectively). No such association was found for gender, race, the use of radiation, the use of surgery, or extent of surgical resection. Only age group was associated with cause-specific survival, with patients < 1 year of age faring worse than older patients (log-rank p-value=0.009, HR 10.4, 95% CI: 1.2-91.0, data not shown).

Table 3. Log rank test p-values and crude hazard ratios for mortality among cases of low grade pediatric gangliogliomas/gangliocytomas, 2004-2010 (n=348).

| p-value* | HR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 31.4 | 2.8-351.4 | |

| 1-4 | 2.2 | 0.1-35.5 | |

| 5-9 | 5.4 | 0.6-52.4 | |

| 10-14 | 2.0 | 0.2-21.7 | |

| 15-19 | ref | ||

| Sex | 0.35 | ||

| Female | 1.9 | 0.5-6.9 | |

| Male | ref | ||

| Race (n=341) | 0.23 | ||

| White | ref | ||

| Not white | 2.3 | 0.6-9.1 | |

| Extent of resection (n=343) | 0.84 | ||

| GTR | ref | ||

| STR | 0.6 | 0.1-4.9 | |

| No surgery | 1.3 | 0.2-10.8 | |

| Radiation treatment (n=345) | 0.16 | ||

| No radiation | ref | ||

| Beam radiation | 4.0 | 0.5-31.8 | |

| Location | 0.01 | ||

| Brainstem | 8.2 | 1.7-39.5 | |

| Spinal cord** | N/A | ||

| Other site | ref |

Overall survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the log-rank test.

0 deaths in patients with spinal cord tumors

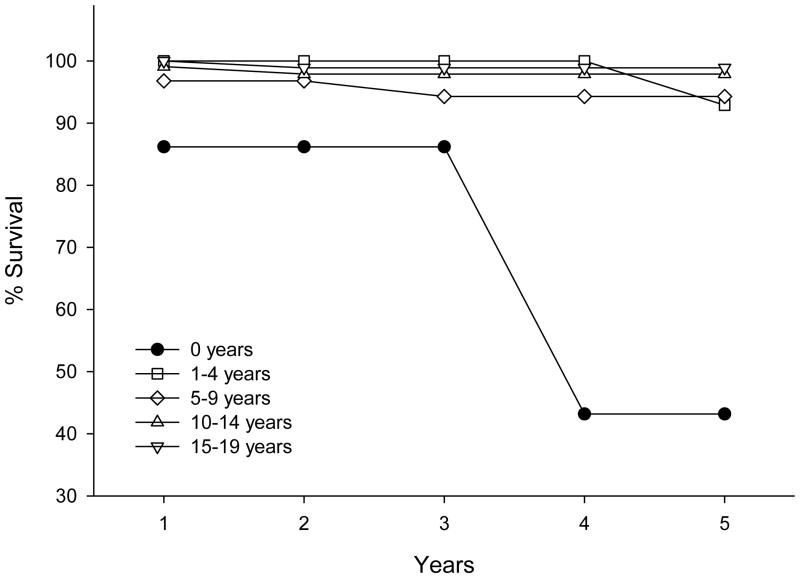

Due to survival associations found for age at diagnosis and anatomical location, we performed 5-year relative survival analysis for these two variables. For age at diagnosis, the 5-year relative survival was >92% for all age groups tested (1-4, 5-9, 10-14, and 15-19 years), except for children diagnosed at less than 1 year of age, for whom 5-year survival was 43.2% (Fig 2). This survival difference could not be explained by differences in anatomical location, extent of resection, or radiation treatment (Table 4), although it should be noted that no patient under 1 year old was treated with radiation, versus a 3.3% radiation use in older patients. There was, however, a statistically significant difference in male to female ratio with only 25% (3/12) males in patients < 1 year old versus 61% males (205/336) in the older patients.

Figure 2.

5-year relative survival analysis of different age groups of patients with low-grade gangliogliomas/gangliocytomas from the SEER datasets (2004-2010).

Table 4. Comparison of demographic and treatment factors by age group among pediatric patients with low-grade gangliogliomas/gangliocytomas, 2004-2010 (n=348).

| < 1 year , n (%) | 1-19 years, n(%) | *p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor location | 0.37 | ||

| Brainstem | 1 (8.3) | 12 (3.6) | |

| Other | 11 (91.7) | 324 (96.4) | |

| Sex | 0.02 | ||

| Male | 3 (25.0) | 205 (61.0) | |

| Female | 9 (75.0) | 131 (39.0) | |

| Extent of Resection (n=344) | 0.63 | ||

| None | 1 (8.3) | 28 (8.4) | |

| STR | 4 (33.3) | 76 (22.9) | |

| GTR | 7 (58.3) | 228 (68.7) | |

| Radiation (n=345) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 11 (3.3) | |

| No | 12 (100.0) | 322 (96.7) |

Fisher's exact test

The 5-year relative survival for patients with low-grade GG in locations other than the brainstem was 96.6%, while 5-year relative survival for patients with brainstem tumors was 80.6% (Fig 3). This difference could not be explained by differences in age, gender, use of radiation, or extent of surgical resection (Table 5). Radiation was used in 1/13 (7.7%) brainstem tumors and 10/332 (3.0%) tumors in other sites. Patients with brainstem tumors had GTR less than patients with tumors at other sites (58.3% and 68.7%, respectively). The GTR percentage for spinal cord tumors alone and other tumors alone was 83.3% and 68.1%, respectively (data not shown). The percentage of brainstem tumors not operated on was double that of other locations (2/12, 16.7% vs 27/332, 8.1%, respectively). Despite the above described male predisposition in the overall population, there were 7 males (53.9%) to 6 females (46.2%) in the brainstem group. These trends did not achieve statistical significance.

Figure 3.

5-year relative survival analysis of patients with gangliogliomas/gangliocytomas of the brainstem, spinal cord, and other locations, from the SEER datasets (2004-2010).

Table 5. Comparison of demographic and treatment factors by anatomic location among pediatric patients with low-grade gangliogliomas/gangliocytomas, 2004-1020 (n=348).

| Other, n (%) | Brainstem, n (%) | *p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.56 | ||

| 0 | 11 (3.3) | 1 (7.7) | |

| 1-4 | 48 (14.3) | 1 (7.7) | |

| 5-9 | 64 (19.1) | 4 (30.8) | |

| 10-14 | 107 (31.9) | 3 (23.1) | |

| 15-19 | 105 (31.3) | 4 (30.8) | |

| Sex | 0.66 | ||

| Male | 201 (60.0) | 7 (53.9) | |

| Female | 134 (40.0) | 6 (46.2) | |

| Extent of Resection (n=344) | 0.38 | ||

| None | 27 (8.1) | 2 (16.7) | |

| STR | 77 (23.2) | 3 (25.0) | |

| GTR | 228 (68.7) | 7 (58.3) | |

| Radiation (n=345) | 0.35 | ||

| Yes | 10 (3.0) | 1 (7.7) | |

| No | 322 (97.0) | 12 (92.3) |

Pearson's chi-square or Fisher's exact test

Discussion

Most reports of low-grade GG include a limited number of patients with mostly tumors of the cerebral hemispheres2;5-7;10-13;22;23. A 30-year review of all age groups from the Mayo Clinic included 88 patients10. The largest study to date included 184 patients, but focused exclusively on supratentorial GG, and included both high-grade and low-grade tumors6. Reports regarding brainstem and spinal cord GG are exceedingly rare, with only 3 previous case series in the literature7-9. Only one of these, which included 58 patients of all ages, attempted to compare outcomes of cerebral, spinal cord, and brainstem tumors9. Few case series have focused specifically on children2;5;7;11-13;22;23;24. To our knowledge this report, which includes 348 pediatric low-grade GG, is the largest study of its kind, and is the only study to compare brainstem and spinal cord GG to tumors in other locations with a large number of children. Inclusion of such a large number of rare tumors in children alone was only made possible by the use of the SEER datasets.

This study confirmed several previously described epidemiological phenomena regarding low-grade GG. First, within the pediatric age groups these are thought to be tumors of older children and young teenagers. In seven studies focusing specifically on children, the mean age ranged from 5.6 to 15.6 years, but the average of all mean ages from those seven studies, including 232 children, was 10.5 years 2;5;5;7;11-13;22. In our study, with 348 children, the mean and median ages at diagnosis were 10.9 and 12.0 years, respectively. Indeed, the majority of patients (62.9%) were older than 10 years of age, while only 3.5% were less than 1 year of age. Secondly, the majority of studies describe an increased male to female ratio of 1.5-1.9:1 for GG in all locations6;9;11;13,24, but a study of only infratentorial GGs found a male to female ratio of 1:113. Likewise, in our study the male to female ratio was 1.5:1 for non-brainstem tumors, but closer to 1:1 for brainstem tumors, with 7 males to 6 females. Finally, most studies describe the temporal lobes as the predominant location for low-grade GG, making these tumors the number one neoplastic entity leading to long-term epilepsy 1;5. Some studies report that 43-79% of GG occur in the temporal lobes2;6;10;24. Here, we found a 47.4% occurrence in the temporal lobes. However, the SEER datasets also included three non-specific codes for “cerebrum”, “overlapping region of the brain”, and “brain, not otherwise specified”15. Together these coding categories contained 37 GG, some of which might represent temporal GGs.

We found that GTR was achieved in 68.3% of children, in keeping with other studies, which report a rate of GTR ranging from 45-79%5;9;10;12;13;22;23,24. At least part of this variability reflects differences in tumor location. Mickle et al. described a 100% GTR rate for supratentorial tumors, and 0% GTR for infratentorial tumors11. In the only study looking specifically at brainstem GG, none underwent GTR8. On the contrary, Lang et al. described 97% GTR for spinal cord GGs, 33% for those of the brainstem, and 63% for those of the cerebral hemispheres9. Similarly, we found a higher GTR percentage for spinal cord tumors (83.3%) than brainstem tumors (58.3%), and the percentage of GTR for other GG (i.e., mostly supratentorial and cerebellar) was in the middle (68.1%) (data not shown). The fact that our study reveals a higher GTR rate for brainstem tumors cannot be explained by more modern techniques or surgical approaches, because some of the above-described series were also very recent.

There appears to be a trend toward less use of radiotherapy for GGs over the last 30 years. Between 1983 and 1997, there were five studies that described a rate of radiation use that ranged from 20-40%9;11;12;22;23. However, since 2004, four studies reported rates of radiation between 2-10%6;7;10;13. The realization that these are generally very benign tumors, and an increased understanding of the detrimental effects of radiation, are likely the main factors responsible for this trend. In our study, which included patients added to the SEER datasets between 2004 and 2010, radiation treatment was used in only 11/345 (3.2%) children.

GGs, in general, are thought to be very benign lesions. In a report regarding supratentorial lesions, Luyken et al. reported a 7.5-year recurrence-free survival of 97%, and a 7.5-year OS of 98%6. These authors found that low-grade lesions, temporal location, epilepsy, and complete resection were associated with better progression-free survival (PFS). Compton et al. studied only low-grade GGs and found 15-year OS of 94%, with a median PFS of 5.6 years and a 10-year PFS of 37% 10. PFS was dramatically associated with extent of resection. This study included supra- and infratentorial tumors, but only 5/88 tumors were located in the brainstem and spinal cord. Specifically looking at children and including 7/38 brainstem/spinal cord tumors, Khashab et al. found the 5-year PFS rate to be 81.2%13. Prolonged PFS was associated with initial presentation with seizures, cerebral hemisphere location, and complete resection. In a rare study that may have been biased toward brainstem/spinal cord tumors (39/58), Lang et al. described worse operative morbidity rates (35% vs 5%), worse 5-year relative survival rates (78.5% vs 93%), and worse event-free survival rates (44.5% vs 95%) for brainstem/spinal cord GGs versus cerebral tumors9. Tumor location was the only factor associated with outcome, with spinal cord/brainstem tumors having a 3.5- and 5-fold increased risk of recurrence. Most recently, Haydon et al. reported on 53 low-grade GG in children, including six infratentorial tumors, and found a 5-yr recurrence-free survival rate of 70.5% and OS rate of 98%. These authors found that older age, supratentorial location, seizure history, and complete resection were associated with prolonged recurrence-free survival, but only complete resection retained significance in multivariate analysis.

The SEER datasets do not allow us to study PFS, but we found that brainstem location was significantly associated with worse OS. This must be interpreted with caution as only 9 patients (2 brainstem and 7 other) died in our study. Furthermore, although the hazard ratio for mortality is elevated, the wide confidence intervals (1.7-39.5) reflect the small sample number of patients with tumors located in the brainstem (n=13). We also found 5-year relative survival to be ≥97% for non-brainstem tumors, but 80.6% for brainstem tumors. The only other factor that was negatively associated with survival was young age (i.e., <1 year), which is similar to the findings of Haydon et al. above. When we performed 5-year relative survival analysis on the patients of different age groups, we found that all patients older than one year of age had 5-year survival of greater than 92%, while patients <1 year of age had a 5-year OS rate of only 43%. Unlike the recent study of Haydon et al.24, and other previous studies6;10;13 we did not identify an association between extent of resection and survival. Of note, for both 5-year relative survival analyses of different age groups and different anatomic locations there was a delayed separation of the survival curves that became most obvious at 3-4 years after diagnosis. This likely reflects the amount of time it takes for recurrence/progression and subsequent patient demise for such a histologically benign and slow-growing tumor, and reinforces the need for long-term follow-up studies for such tumors. Unfortunately, due to the limitations of the SEER datasets we cannot say whether the patients suffered morbidity related to the initial tumor resection, and/or repeated procedures to treat delayed recurrences. At present, it is unclear why very young patients would do so much worse. This could not be explained by differences in age, extent of resection, or radiation use. There was a statistically significant difference in male to female ratio with much fewer males in children <1 year of age, but how this might relate to survival is unclear. Unlike other pediatric brain tumors, where such a relationship might be attributed to the lack of radiation therapy use in the very young children, radiation therapy was only employed in 3.4% of pediatric patients of all ages in SEER. However, while we did not find a statistically significant difference between these very young patients and older patients in terms of radiation use, it should be noted that not a single patient < 1 year of age was treated with radiation. In addition, GTR was achieved in a smaller percentage of patients <1 year old. As the small numbers of patients in this subgroup precluded us from studying interactions between GTR and radiation use, at this point we cannot fully dismiss the possibility that these infants have worse survival because they are left with greater residual tumor, without an option for adjuvant radiation post-operatively.

Likewise, it is unclear why outcome is worse for low-grade GG in the brainstem. It is intuitive that tumors in this location would be more difficult to resect, and indeed we found a trend toward less GTR for these tumors. However, this did not achieve statistical significance. Furthermore, there was no statistically significant difference in age, gender, or radiation use. This leaves us to speculate that these tumors are inherently different, due to genetic or molecular characteristics. Rush et al., noted that brainstem GG are difficult to treat despite their low-grade pathological characteristics and suggested that this might be related to activating mutations in the BRAF gene25,26. To our knowledge, genetic differences between brainstem GG and those in other locations have not been described, but molecular signatures, such as BRAF mutations, or other yet to be defined genetic alterations, might provide insight into the survival trends observed in SEER.

Limitations

We have previously described various limitations inherent in the use of SEER datasets as a means of studying epidemiology and outcomes, particularly for benign tumors 19. Briefly, because benign tumors, such as GG, were added to the SEER datasets in 2004, there is a relatively short period of follow-up, which limits the conclusions that can be drawn from survival statistics. Also, the small number of outcome events (i.e., deaths) limits our ability to detect survival relationships. In particular, we were not able to perform multivariate analysis due to the small number of deaths. PFS is perhaps more relevant for such tumors, but the SEER datasets do not provide information regarding this outcome measure. Furthermore, SEER offers no data regarding quality-of-life, such as control of seizures or cranial nerve dysfunction. In addition, SEER does not include data on other factors affecting survival, such as the use of chemotherapy, socioeconomic status, and the biological profiles of tumors. Also, as we and others have done previously, we defined “extent of resection” based on the surgical codes provided by SEER that are most in keeping with GTR and STR. However, SEER does not offer a standardized means of defining these variables, which leaves our definition open to criticism. Furthermore, retrospective database analysis using the SEER datasets is not conducive to pathology re-review, which can be a concern when basing conclusions on small numbers of tumors within sub-groups. For instance, here we report that very young patients (<1 year old) had the worse survival, but this is based on only 12 cases. Although the individual institutions, SEER delegates, as well as independent examiners review the cases entered into the SEER dataset, without 2014 pathology re-review we cannot say with 100% certainty that all cases were truly low-grade gangliogliomas/gangliocytomas. Finally, this study is subject to all the potential biases of a retrospective, registry-based study, including selection and reporting bias. For instance, it is possible that some patients with brainstem, or spinal cord, or supratentorial tumors in eloquent regions of the brain were not treated, and therefore possibly not reported as well.

Conclusion

Analysis of 348 low-grade GG from the SEER datasets defines these as tumors of older children and young teenagers, with a male predominance, and a predilection to the temporal lobes. GTR is achieved in the majority of these tumors, and radiation therapy is only rarely used. Survival rates for patients with low-grade GG are high, with 96% 5-year relative survival. Worse OS is associated with young age and brainstem location, but at present this cannot be explained by age, gender, extent of resection, or the use of radiation treatment. We did not find an association between extent of resection and survival. Analysis of a larger group of low-grade pediatric GG cases would permit a more robust evaluation of demographic and treatment factors associated with mortality in this patient population. Further work is needed to confirm these findings and to improve outcomes for the more vulnerable subgroups.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to Judy Gault, PhD., for all her assistance in the final formatting and submission of this manuscript.

Funding Sources: Grant UL1 TR001082 from NCATS/NIH (TCH), Morgan Adams Foundation (TCH), Children's Hospital Colorado Research Institute (TCH), NIH/NICHD Child Health Research Career Development Award (K12 HD068372) (JML)

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no personal, financial, or institutional interest in any of the drugs, materials, or devices described in this article.

References

- 1.Becker AJ, Wiestler OD, Figarella-Branger D, Blumcke I. Ganglioglioma and gangliocytoma. In: Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2007. pp. 103–105. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ventureyra E, Herder S, Mallya BK, Keene D. Temporal lobe gangliogliomas in children. Childs Nerv Syst. 1986;2:63–66. doi: 10.1007/BF00286222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adachi Y, Yagishita A. Gangliogliomas: Characteristic imaging findings and role in the temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroradiology. 2008;50:829–834. doi: 10.1007/s00234-008-0410-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumcke I, Wiestler OD. Gangliogliomas: an intriguing tumor entity associated with focal epilepsies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:575–584. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.7.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khajavi K, Comair YG, Prayson RA, et al. Childhood ganglioglioma and medically intractable epilepsy. A clinicopathological study of 15 patients and a review of the literature. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1995;22:181–188. doi: 10.1159/000120899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luyken C, Blumcke I, Fimmers R, Urbach H, Wiestler OD, Schramm J. Supratentorial gangliogliomas: histopathologic grading and tumor recurrence in 184 patients with a median follow-up of 8 years. Cancer. 2004;101:146–155. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baussard B, Di RF, Garnett MR, et al. Pediatric infratentorial gangliogliomas: a retrospective series. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:286–291. doi: 10.3171/PED-07/10/286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang S, Wang X, Liu X, Ju Y, Hui X. Brainstem gangliogliomas: a retrospective series. J Neurosurg. 2013;118:884–888. doi: 10.3171/2013.1.JNS121323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lang FF, Epstein FJ, Ransohoff J, et al. Central nervous system gangliogliomas. Part 2: Clinical outcome. J Neurosurg. 1993;79:867–873. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.79.6.0867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Compton JJ, Laack NN, Eckel LJ, Schomas DA, Giannini C, Meyer FB. Long-term outcomes for low-grade intracranial ganglioglioma: 30-year experience from the Mayo Clinic. J Neurosurg. 2012;117:825–830. doi: 10.3171/2012.7.JNS111260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mickle JP. Ganglioglioma in children. A review of 32 cases at the University of Florida. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1992;18:310–314. doi: 10.1159/000120681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson JH, Jr, Hariharan S, Berman J, et al. Clinical outcome of pediatric gangliogliomas: ninety-nine cases over 20 years. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1997;27:203–207. doi: 10.1159/000121252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El KM, Gargan L, Margraf L, et al. Predictors of tumor progression among children with gangliogliomas. Clinical article J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2009;3:461–466. doi: 10.3171/2009.2.PEDS0861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.List of SEER registries - About SEER. [Accessed Jan 2014];2014 http://seer.cancer.gov/registries/list.html. http://seer.cancer.gov/registries/list.html [serial online]

- 15.List of SEER registries - AboutSEER. [Accessed Jan 2014];2014 http://seer.cancer.gov/registries/list.html. http://seer.cancer.gov/registries/list.html [serial online]

- 16.Sampson JH, Lad SP, Herndon JE, Starke RM, Kondziolka D. Editorial: SEER insights. J Neurosurg. 2013 doi: 10.3171/2013.6.JNS13993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park HS, Lloyd S, Decker RH, Wilson LD, Yu JB. Limitations and biases of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Curr Probl Cancer. 2012;36:216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.SEER Program Coding and Staging Manual. [Accessed May 2014];2012 http://seer.cancer.gov/registries/list.html. http://seer.cancer.gov/registries/list.html [serial online]

- 19.Hankinson TC, Fields EC, Torok MR, et al. Limited utility despite accuracy of the national SEER dataset for the study of craniopharyngioma. J Neurooncol. 2012;110:271–278. doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-0966-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noorbakhsh A, Tang JA, Marcus LP, et al. Gross-total resection outcomes in an elderly population with glioblastoma: a SEER-based analysis. J Neurosurg. 2014;120:31–39. doi: 10.3171/2013.9.JNS13877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.SEER-Stat Software Version 8.1.2 . Surveillance Research Program. National Cancer Institute; 2014. Version Version 8.1.2. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chintagumpala MM, Armstrong D, Miki S, et al. Mixed neuronal-glial tumors (gangliogliomas) in children. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1996;24:306–313. doi: 10.1159/000121060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sutton LN, Packer RJ, Rorke LB, Bruce DA, Schut L. Cerebral gangliogliomas during childhood. Neurosurgery. 1983;13:124–128. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198308000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haydon DH, Dahiya S, Smyth MD, Limbrick DD, Leonard JR. Greater extent of resection improves gangliogliomarecurrence-free survival in children: A volumetric analysis. Neurosurgery. 2014;75:37–42. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rush S, Foreman N, Liu A. Brainstem ganglioglioma successfully treated with vemurafenib. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:e159–e160. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donson AM, Kleinschmidt-Demasters BK, Aisner DL, et al. Pediatric Brainstem Gangliogliomas Show BRAF Mutation in a High Percentage of Cases. Brain Pathol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/bpa.12103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]