Abstract

Context:

Little is known about cancer-related worry in thyroid cancer survivors.

Objectives:

We quantified cancer-related worry in Canadian thyroid cancer survivors and explored associated factors.

Design, Setting, and Participants:

We performed a cross-sectional, self-administered, written survey of thyroid cancer survivor members of the Thyroid Cancer Canada support group. Independent factors associated with cancer-related worry were identified using a multivariable linear regression analysis.

Main Outcome Measure:

We used the Assessment of Survivor Concerns (ASC) questionnaire, which includes questions on worry about diagnostic tests, second primary malignancy, recurrence, dying, health, and children's health.

Results:

The response rate for eligible members was 60.1% (941 of 1567). Most respondents were women (89.0%; 837 of 940), and the age was < 50 years in 54.0% of participants (508 of 941). Thyroid cancer was diagnosed within ≤ 5 years in 66.1% of participants (622 of 940). The mean overall ASC score was 15.34 (SD, 4.7) (on a scale from 6 [least worry] to 24 [most worry]). Factors associated with increased ASC score included: younger age (P < .001), current suspected or proven recurrent/persistent disease (ie, current proven active disease or abnormal diagnostic tests) (P < .001), partnered marital status (P = .021), having children (P = .029), and ≤5 years since thyroid cancer diagnosis (P = .017).

Conclusions:

In a population of Canadian thyroid cancer survivors, cancer-related worry was greatest in younger survivors and those with either confirmed or suspected disease activity. Family status and time since thyroid cancer diagnosis were also associated with increased worry. More research is needed to confirm these findings and to develop effective preventative and supportive strategies for those at risk.

Approximately 6000 Canadians were diagnosed with thyroid cancer this year (1). In fact, the incidence of thyroid cancer is rising faster than any other cancer in Canada (1), with an overall rise of 156% from 1991 to 2006 (2). It is currently the most commonly diagnosed malignancy in Canadian women aged 15 to 29 years and the second most common malignancy in women aged 30 to 49 years (1). Furthermore, about 40% of thyroid cancer cases diagnosed in Canadians are in individuals younger than 45 years of age (3). Thyroid cancer has one of the highest relative 5-year survival rates of all cancers (98%) in Canada, and this rate has been relatively stable in recent years (1). Similar increases in thyroid cancer incidence have been reported in the United States (4–9), and such trends are associated with significant clinical and economic burden (9). Given the rise in incidence of thyroid cancer (1–9) and the relatively low risk of dying of this disease (1, 8), the number of thyroid cancer survivors is increasing in both Canada and the United States.

One of the most frequently reported concerns of cancer survivors is fear of recurrence (10, 11). Fear of recurrence may be considered in conjunction with other health concerns as a broader indicator of cancer-related worry in survivors (12). The degree of cancer-related worry in thyroid cancer survivors is not known. Fear of progression of chronic illness was examined in a single-center cross-sectional study of Korean thyroid cancer survivors (13), and the authors indicated that self-reported performance of activities of daily living was impaired in individuals with recurrent or metastatic thyroid cancer compared to those in remission (13). However, the questionnaire employed in that study was designed for use in chronically physically ill patients (14), and it may not necessarily be optimal for thyroid cancer survivors in remission. In the present study, our primary objective was to quantify the degree of cancer-related worry in a sample of Canadian thyroid cancer survivors. A secondary objective was to explore factors associated with cancer-related worry in this population.

Subjects and Methods

We performed a cross-sectional, self-administered, written survey in collaboration with the Thyroid Cancer Canada (TCC) patient support group. TCC is a charitable organization whose mandate includes patient education, provision of emotional support, and facilitating communication among survivors and their healthcare providers, as well as advocacy. The eligibility criteria included membership in TCC, a personal history of thyroid cancer, and willingness to complete and return (by mail) the written questionnaire. The survey was conducted in English. The questionnaire utilized for the study included questions on demographic characteristics, personal thyroid cancer history, and cancer-related worry. The questionnaire was accompanied by a coversheet explaining the study, and participants who were either not thyroid cancer survivors or not interested in the study were provided the opportunity to return the coversheet, indicating the reason for nonparticipation. On behalf of the study, TCC mailed out the questionnaire to all of its members who had a Canadian postal address on January 12, 2012. We provided a self-addressed return envelope, but there was no reimbursement for study participation. There was only one mailing of the survey, but 2 weeks after the initial mailing, a reminder/thank-you postcard was sent to the same individuals who received the original survey. The study was approved by the University Health Network Research Ethics Board.

We utilized the six-item Assessment of Survivor Concerns (ASC) questionnaire (12) to evaluate cancer-related worry. The ASC questionnaire includes three questions focused on the construct of cancer worry (cancer worry subscale), specifically worries about the following: diagnostic tests, another type of cancer, or cancer coming back (12). The ASC also includes three questions focused on health worry (Health Worry Subscale), specifically worry about dying, personal health, or children's health (12). All ASC questions were scored on a Likert Scale of agreement, with responses for individual questions ranging from 1 (least worry) to 4 (most worry). Results for respective cancer worry and health worry subscales were calculated by summing the results of questions in that category. Similarly, the overall ASC score was calculated by summing the results for all questions (range of possible overall ASC scores, 6 [least worry] to 24 [most worry]). The internal reliability of the ASC questionnaire has been previously evaluated by Gotay et al (12), and the alpha level for internal consistency of the cancer worry subscale was reported to be 0.93, whereas the alpha level for the health worry subscale was 0.63 (or 0.73 if the question on worry about children's health was omitted). In the original paper describing the development of the ASC, the authors reported that a large proportion of participants (18.6%; 140 of 753) did not respond to the question on children's health, and the authors suggested that this question could be dropped in the future (12). Because TCC collaborators and investigators in our study considered worry about children's health relevant to a thyroid cancer survivor population, rather than removing this question, we elected to add a “not applicable” response option. For the “not applicable” responses on children's health, although we recorded the frequency of this response, the score for the question was imputed by calculating the mean of other responses in the Health Worry Subscale for respective individuals. Otherwise, missing responses to ASC questions were imputed as per the mean of the relevant subscale for the individual, with the number of missing responses reported descriptively. Published historical control ASC data were reported from the original mixed cancer population study by Gotay et al (12).

Participants' self-reported questionnaire data were electronically entered by research staff in a spreadsheet, and all electronically entered data were checked for accuracy by a second research staff member. Discrepancies in data entry were resolved by research staff discussion with the primary investigator (A.M.S.). Descriptive data were summarized as means and standard deviations or ranges for continuous data or as number and percentage for nominal data. Internal reliability statistics for ASC subscales were calculated using Cronbach's alpha and Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICCs) of average measures for respective cancer worry and health worry subscales. A value of 0.7 or greater has been recommended as a minimum quality criterion for such estimates (15). Univariate predictors of overall ASC score were examined using unpaired Student's t tests or ANOVA, depending on the number of categories examined. A multivariable linear regression analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of overall ASC score for all variables in which P ≤ .2 in respective univariate analyses. Colinearity within the final model was investigated by estimation of the variance inflation factor of each variable, and a variance inflation factor value < 10 was considered acceptable (16). The criterion for statistical significance of predictors in the multivariable model was set at α = 0.05 (with 95% confidence intervals [CIs] for the coefficient of increase in mean score greater than zero). We examined the residuals and also used R-squared to assess goodness-of-fit of the multivariable model. All analyses were conducted using PASW Statistics 18 (formerly known as SPSS, of IBM).

Our target population was defined a priori as TCC members meeting inclusion criteria. We used the CI approach to determine the sample size needed to estimate the mean total ASC score for this population with a 95% CI:

where z = 1.96 is the score corresponding to the 95% CI, SD is the standard deviation for total ASC score, and E is the margin of error. The calculation was performed using Excel (Microsoft Corporation) based on a standard deviation of total ASC score of 5 and a margin of error of 0.4, leading to a sample size of at least 600 respondents. We also assumed that at least 400 participants would be needed to meet the accepted minimum standard for estimation of reliability assessment (17), to be applied to the ASC questionnaire.

Results

Response rate and characteristics of the study population

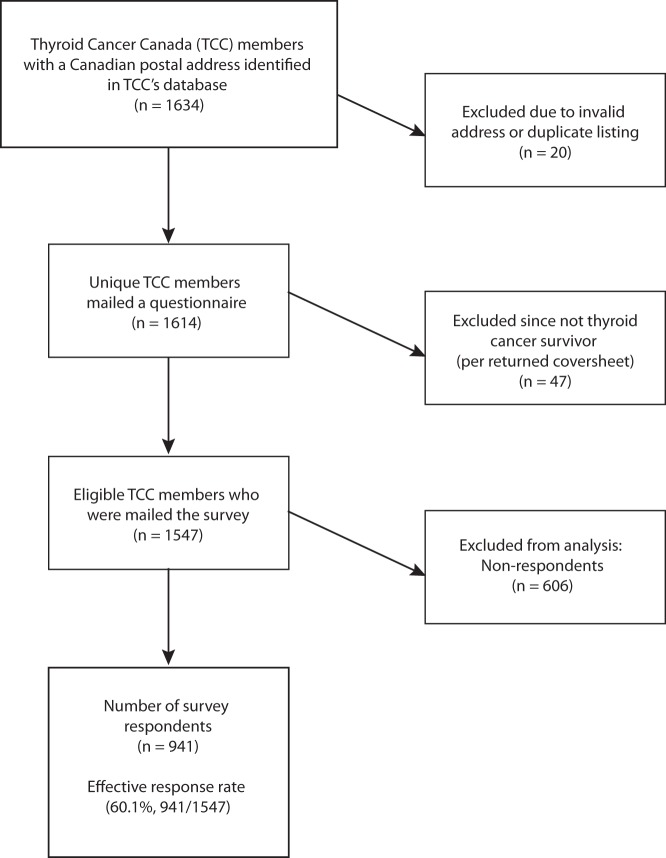

The survey was mailed to 1634 individuals, although 20 of these were invalid due to incorrect addresses or duplicate listings, such that the survey was mailed to 1614 unique individuals with valid mailing addresses. The regional distribution of mailed questionnaires was as follows: Maritime provinces (Newfoundland, Labrador, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick), 9.6% (155 of 1614); Quebec, 9.6% (155 of 1614); Ontario, 64.8% (1046 of 1614); and Western Provinces and Northern territories (Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia, Nunavut, Northwest Territories), 16.0% (258 of 1614). Of the 1614 individuals who were mailed the questionnaire, 47 (2.9%) returned the coversheet, indicating that they were not eligible for the study because they were not thyroid cancer survivors. The effective response rate of potentially eligible individuals was thus 60.1% (941 of 1547) (Figure 1). The regional distribution of received completed questionnaires was as follows: Maritime provinces, 11.1% (104 of 941); Quebec, 9.4% (88 of 941); Ontario, 62.5% (588 of 941); and Western provinces and Northern territories, 17.1% (161 of 941). The demographic characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. Reflecting typical thyroid cancer epidemiology, most respondents were women (89.0%, 837 of 940), and the age was < 50 years in 54.0% of participants (508 of 941). Thyroid cancer had been diagnosed within ≤ 5 years in 66.1% of participants (622 of 940). The vast majority of participants reported a history of well-differentiated nonmedullary thyroid cancer (870 of 926; 94.0%). Most participants had a history of treatment with total thyroidectomy (911 of 939; 97.0%) and radioactive iodine (RAI) treatment (780 of 925; 84.3%). Approximately three-fourths of respondents (601 of 801) indicated that they had no current evidence of thyroid cancer, although abnormal thyroid cancer tests were reported by 18.7% of respondents (150 of 801), and known recurrent or persistent disease in lymph nodes or distant metastases was reported by a minority of individuals (50 of 801; 6.2%). Of note, approximately one in six respondents did not know her/his current thyroid cancer disease status (139 of 941; 14.8%).

Figure 1.

Study flow.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristics | No. of Respondents (%)a,b |

|---|---|

| n | 941 |

| Age | |

| ≤30 y | 55/941 (5.8) |

| 31 to 49 y | 453/941 (48.1) |

| 50 to 65 y | 332/941 (35.3) |

| >65 y | 101/941 (10.7) |

| Female sex | 837/940 (89.0) |

| Partnered marital status (married or common-law relationship) | 716/939 (76.3) |

| Have children | 682/940 (72.6) |

| Education | |

| High school or lower | 241/939 (25.7) |

| College or University degree | 551/939 (58.7) |

| Graduate degree | 147/939 (15.7) |

| Birth country outside of Canada | 178/940 (18.9) |

| Years since diagnosis of thyroid cancer | |

| <1 y | 129/941 (13.7) |

| 1 to 2 y | 227/941 (24.1) |

| 3 to 5 y | 266/941 (28.3) |

| >5 y | 319/941 (33.9) |

| Type of thyroid cancer | |

| Well-differentiated | 870/926 (94.0) |

| Medullary | 10/926 (1.1) |

| Poorly differentiated or anaplastic | 5/926 (0.5) |

| Mixed (more than one type) | 41/926 (4.4) |

| History of total thyroidectomy | 911/939 (97.0) |

| Any known history of distant metastatic disease | 40/883 (4.5) |

| History of neck reoperation for thyroid cancer recurrence | 87/909 (9.6) |

| No. of RAI treatments for thyroid cancer | |

| None | 145/925 (15.7) |

| 1 | 608/925 (65.7) |

| ≥2 | 172/925 (18.5) |

| Self-reported thyroid cancer disease status | |

| No known thyroid cancer at present | 601/801 (75.0) |

| Abnormal tests for thyroid cancer | 150/801 (18.7) |

| Known recurrent/persistent disease in lymph nodes or distant metastases | 50/801 (6.2) |

Percentage of missing response rates for respective questions: 0% (0 of 941) for the question on age, timing of thyroid cancer diagnosis; 0.1% (1 of 941) for the questions on gender, having children, birth country, extent of surgery, RAI treatment, current thyroid cancer disease status; 0.2% (2 of 941) for the questions on marital status, education, thyroid cancer type; 0.4% (4 of 941) for the question on history of neck reoperation for recurrence; and 0.5% (5 of 941) for the question on any history of distant metastases.

Percentage of “don't know” responses for respective questions: 0.1% (1 of 941) for the question on extent of thyroid surgery; 1.4% (13 of 941) for the question on type of thyroid cancer (not including 30 individuals who wrote in their type of thyroid cancer on the questionnaire, and for whom a category could be assigned by investigators); 1.6% (15 of 941) for the question on RAI treatment for thyroid cancer; 3.0% (28 of 941) for the question on neck reoperation for recurrence; 5.6% (53 of 941) for the question on history of distant metastases; and 14.8% (139 of 941) for the question on current disease status.

Cancer-related worry in thyroid cancer survivors

Responses to the ASC questionnaire on cancer-related worry are shown in Table 2, adjacent to reference historical control data from mixed cancer survivors reported by Gotay et al (12). The number of missing responses to questions ranged from 0.2 to 0.6% for each respective ASC question (Table 2). For the question on children's health, 26.5% (249 of 939) of respondents indicated that this was “not applicable” to them, of which 95.6% (238 of 249) were individuals without children; only 0.2% (2 of 941) of individuals chose not to respond to this question. Cronbach's alpha for the ASC subscales was as follows: Cancer Worry Subscale, 0.86 (n = 940); Health Worry Subscale (including the question on children's health), 0.80 (n = 940); Health Worry Subscale (excluding the question on children's health), 0.76 (n = 690). Furthermore, the ICC with 95% CI for average measures within subscales was as follows: Cancer Worry Subscale, 0.86 (0.84, 0.87) (n = 940); Health Worry Subscale (including the question on children's health), 0.80 (0.78, 0.82) (n = 940); and Health Worry Subscale (excluding the question on children's health), 0.76 (0.73, 0.79) (n = 690). The respective means and standard deviations for ASC worry questions in TCC participants were as follows: tests, 2.46 (0.97); second primary, 2.65 (0.95); recurrence, 2.60 (0.98); dying, 2.12 (0.99); health, 2.77 (0.92); and children's health, 2.74 (0.97) (n = 940), where 1 is the least worry and 4 is the most worry. The mean overall ASC score was 15.34 (SD, 4.67) (on a scale from 6 [least worry] to 24 [most worry]), with the mean score for the Cancer Worry Subscale being 7.71 (SD, 2.55) and the Health Worry Subscale being 7.63 (SD, 2.43) (where the possible range for respective subscale scores is 3 to 12, with 12 being the greatest worry). A subgroup analysis of ASC data from long-term cancer survivors is shown in Table 2, with the cut-point for long-term survivorship being approximately 5 years in this study as well as that by Gotay et al (12). For long-term thyroid cancer survivors, the mean overall ASC score was 14.84 (SD, 4.36) (on a scale from 6 [least worry] to 24 [most worry]), with the mean score for the Cancer Worry Subscale being 7.39 (SD, 2.40) and for the Health Worry Subscale being 7.46 (SD, 2.33) (where the possible range for respective subscale scores is 3 to 12, with 12 being the greatest worry).

Table 2.

Responses to ASC Questionnaire

| Specific Type of Cancer-Related Worry | Thyroid Cancer Canada Participants | Published Mixed Cancer Survivorsa |

|---|---|---|

| Entire study population | n = 940 | n = 753 for study |

| Cancer worry questionsb,c | ||

| Future tests | 2.46 (0.97) | 2.56 (1.18) |

| New cancer | 2.65 (0.95) | 2.67 (1.17) |

| Recurrence | 2.60 (0.98) | 2.60 (1.19) |

| Health worry questionsb,c | ||

| Death | 2.12 (0.99) | 1.37 (0.69) |

| Health | 2.77 (0.92) | 1.73 (0.85) |

| Children's healthd | 2.74 (0.97) | 1.57 (0.86) |

| Long-term cancer survivorse | n = 318 | n = 161 for study |

| Cancer worry questionsf,g | ||

| Future tests | 2.33 (0.90) | 2.61 (1.11) |

| New cancer | 2.58 (0.89) | 2.75 (1.12) |

| Recurrence | 2.47 (0.90) | 2.69 (1.16) |

| Health worry questionsf,g | ||

| Death | 2.07 (0.94) | 1.37 (0.72) |

| Health | 2.66 (0.92) | 1.86 (0.93) |

| Children's healthh | 2.72 (0.94) | 1.72 (0.90) |

Data are expressed as mean score (SD). Possible range is 1 to 4, with greatest worry 4.

Ref. 12.

Percentage of missing responses to respective questions in the entire thyroid cancer population: tests, 0.3% (3 of 941); another cancer, 0.2% (2 of 941); recurrence, 0.6% (6 of 941); dying, 0.5% (5 of 941); health, 0.3% (3 of 941); children's health, 0.2% (2 of 941), including one individual who did not respond to any ASC questions.

Percentage of missing responses to respective questions in the entire mixed oncology population as previously reported by Gotay et al (12): tests, 4.0% (30 of 753); another cancer, 4.4% (33 of 753); recurrence, 2.9% (22 of 753); dying, 2.7% (20 of 753); health, 2.0% (15 of 753); children's health, 18.6% (140 of 753).

For the question on children's health (in the entire thyroid cancer study population), the percentage of responses indicating “not applicable” was 26.5% (249 of 941), of which 95.6% (239 of 249) were in individuals without children.

Long-term cancer survivors are defined as >5 years since initial diagnosis in the thyroid cancer population, or 5–6 years after diagnosis in the mixed oncology population, respectively.

Percentage of missing responses to respective questions in the long-term thyroid cancer subgroup population: tests, 0.6% (2 of 319); another cancer, 0.6% (2 of 319); recurrence, 1.9% (6 of 319); dying, 1.3% (4 of 319); health, 0.9% (3 of 319); children's health, 0.6% (2 of 319), including one individual who did not respond to any ASC questions.

Percentage of missing responses to respective questions in the long-term survivor subgroup of the mixed oncology population, as previously reported by Gotay et al. (12): tests, 2.5% (4 of 161); another cancer, 2.5% (4 of 161); recurrence, 0.6% (1 of 161); dying, 1.9% (3 of 161); health, 0.6% (1 of 161); children's health, 16.8% (27 of 161).

For the question on children's health (in the long-term thyroid cancer subgroup population), the percentage of responses indicating “not applicable” was 26.3% (84 of 319).

Associations with cancer-related worry in thyroid cancer survivors

The results of univariate and multivariable linear regression analyses predicting the number of points of increased ASC score above the mean as a coefficient of the mean difference is shown in Table 3. Given the relatively limited number of individuals in the youngest (<30 y) and oldest (>65 y) age categories, and given that the cut-point of 50 years may approximate a distinction in reproductive age and has been used in other types of studies of survivor concerns (15), we compared those < 50 years of age to those ≥ 50 years of age as respective categories for inclusion in predictive analyses. Similarly, for the variable of education, given the relatively low number of individuals with graduate degrees, we grouped those with graduate degrees with others who completed postsecondary (college or university) education. Also, for the purpose of predictive analyses, we grouped prior RAI treatments as either presence or absence of this treatment. Similar to Gotay et al (12), we distinguished long-term cancer survivors as those > 5 years after diagnosis, for use in predictive analyses; those ≤ 5 years after diagnosis were considered short-term survivors in our study. Also, given the relatively low percentage of individuals with known current recurrent/persistent disease in lymph nodes or distant metastases, these individuals were grouped with those with abnormal tests for the predictive analyses. Factors associated with increase in mean ASC score included: younger age (regression coefficient [RC], 1.65; 95% CI, 0.96, 2.27; P < .001), current suspected or proven recurrent/persistent disease (ie, current proven active disease or abnormal diagnostic tests) (RC, 1.77; 95% CI, 0.99, 2.54; P < .001), partnered marital status (RC, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.15, 1.77; P = .021), having children (RC, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.09, 1.61; P = .029), and < 5 years since thyroid cancer diagnosis (RC, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.15, 1.47; P = .017) (Table 3). Education, birth country, and RAI use were not significantly associated with increased ASC score (Table 3).

Table 3.

Variables Predicting Cancer-Related Worry in Thyroid Cancer Survivors

| Variable | Univariate Analyses, Mean Difference ASC Total Score (Student's t Test)a | Multivariable Linear Regression Model (n = 764 for Model)b |

|---|---|---|

| Age <50 y | 1.41 (0.81, 2.00); P < .001 | 1.65 (0.96, 2.27); P < .001 |

| Married/common-law marital status (compared to single, divorced, separated, or widowed) | 0.83 (0.13, 1.54); P = .020 | 0.96 (0.15, 1.77); P = .021 |

| Have children (compared to no children) | 0.82 (0.13, 1.50); P = .019 | 0.85 (0.09, 1.61); P = .029 |

| Birth country outside Canada (vs Canada) | 0.59 (−0.20, 1.38); P = .145 | 0.16 (−0.68, 1.00); P = .705 |

| Short-term cancer survivor (≤5 y after diagnosis vs >5 y) | 0.75 (0.14, 1.36); P = .016 | 0.81 (0.15, 1.47); P = .017 |

| Any history of distant metastases | 1.51 (−0.06, 3.08); P = .059 | 1.47 (−0.09, 3.04); P = .065 |

| Current suspected or proven recurrent or persistent disease | 2.03 (1.26, 2.80); P < .001 | 1.77 (0.99, 2.54); P < .001 |

| College education or higher (vs lower) | 0.34 (−0.37, 1.05); P = .352 | — |

| History of any RAI treatment for thyroid cancer | 0.21 (−0.64, 1.06); P = .631 | — |

Data are expressed as estimate of coefficient of mean difference (95% CI); P value; dashes, not applicable.

Unequal variances were assumed between groups.

All variables for which P ≤ .2 in the univariate analyses were included in the multivariable model. The final model r value is 0.288, and R-squared is 0.083. The variance inflation factor for each factor in the multivariable model was estimated as follows: age, 1.07; marital status, 1.16; having children, 1.17; birth country, 1.02; duration of survivorship, 1.03; any history of distant metastases, 1.09; and current thyroid cancer status, 1.08.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional survey study, we learned that the degree of cancer-related worry in thyroid cancer survivors was at least comparable to published data in general oncology populations. In multivariable analyses, we found that younger age and current thyroid cancer disease status were the strongest predictors of cancer-related worry. Other significant factors independently associated with this outcome included partnered marital status, having children, and shorter time since thyroid cancer diagnosis.

It is important to consider the psychosocial impact of malignancy in the context of patients' lives and disease treatment circumstances. Younger age has been associated with increased fear of disease recurrence in other cancer populations (10, 18–26), sometimes persisting years after primary treatment (27). Also, younger age is associated with greater psychological distress in adult cancer survivors, after adjustment for clinical and sociodemographic variables (28). In a systematic review examining quality of life and behavioral outcomes in breast cancer survivors, Howard-Anderson et al (18) reported that premenopausal women experienced greater depressive symptoms (both incidence risk and severity), stress and anxiety, poorer health-related quality of life, and more menopausal and fertility concerns. Survivors of cancer diagnosed in adolescence and young adulthood face the challenge of coping with cancer treatment in the context of such developmental challenges as achieving emotional and economic independence, developing intimate relationships, forming career goals, and developing personal identity (29). Furthermore, younger age and motherhood have been independently associated with increased fear of recurrence in breast cancer survivors (23, 24). We show here that these factors similarly contribute to thyroid cancer survivors. Mothers who are cancer patients or survivors may be concerned about the impact of their malignancy, its treatment, or treatment complications on their family and offspring. Furthermore, a systematic review reporting experiences of cancer survivors who were parents of young children suggested that some women feel guilty about perceiving themselves as not being a “good parent,” face challenges talking to their children about their malignancy, and struggle to maintain their routine home lifestyle (30). Taking these findings together, it appears that young adults, particularly those with children, may face special challenges in maintaining normalcy in their lives. Also consistent with our results, a cross-sectional study of mixed cancer survivors from oncology clinics suggested that patients with active disease had greater cancer-related worry than those in remission (31). Nevertheless, recent systematic reviews in general oncology populations have reported some conflicting data on the significance of association of marital status (10, 25), having children (10), time since diagnosis/treatment (10, 25), and disease-related factors (metastases or recurrence) (10, 25), treatment modality (25), and psychological factors (25) in predicting fear of cancer recurrence. Although we did not examine fatigue or symptom burden in our study, these variables have been associated with increased cancer-related worry in stage 0 to II breast cancer survivors studied years after primary treatment (27). Further research examining any potential associations between fatigue or symptom burden and cancer-related fatigue in thyroid cancer survivors would be of interest.

Health service consequences of cancer-related worry are important to consider. Cancer-related worry (32) and fear of cancer recurrence (32, 33) have been respectively associated with more medical follow-up visits (32, 33), emergency department visits (33), and telephone calls to healthcare providers (32). The optimal strategy to manage cancer-related worry in the context of medical follow-up is not known, and various cancer specialists may differ in their approach (34). In a recent survey of medical oncologists and surgeons caring for breast cancer survivors (34), approximately 60% of such physicians routinely initiated discussions about cancer-related worry with their patients. In that study, surgeons were more likely to refer affected patients to support groups or online resources, whereas oncologists were more likely to refer to a psychologist or use medications (34). A survey of medical oncologists and primary care physicians suggested that about half of respective physician groups reported broad involvement in psychosocial care of cancer survivors, yet there were some differences in opinions as to which group would deliver specific aspects of care (35). The authors of that study suggested that there was a lack of clarity about the responsibility of providers to deliver psychosocial care to survivors (35). It is not known how thyroid specialists and primary care physicians view their roles in providing psychosocial support to thyroid cancer survivors.

There are little data on thyroid cancer-related worry. However, in a recent international survey of survivors, almost half of respondents indicated that their care could be improved through introduction to a patient support group (42%) or referral to a psychologist (43%) (36). In a recent online survey conducted by an American thyroid cancer support group (ThyCa: Thyroid Cancer Survivors' Association), about two-thirds of respondents, regardless of age, indicated that receiving information about support groups or counseling to manage emotional distress was very important (37).

An unexpected secondary finding in this study was the heightened worry about death in thyroid cancer survivors, particularly given the generally low mortality risk of this malignancy relative to other cancers. Patients' level of worry about death may impact physician behavior and health services use because Papaleontiou et al (38) have recently reported that in a national survey of American thyroid cancer physicians, some physicians reported that patients' worry about death was “quite or very important” in deciding to give postoperative RAI treatment. The impact of patients' worry about death on physicians prescribing RAI was most prevalent in physicians seeing relatively low numbers of thyroid cancer patients (38). In our study, the level of worry about death was relatively similar, regardless of whether RAI was given or not, although a lack of data on initial disease stage and pretreatment worry limits any ability to know whether the RAI administration had any effect on patients' level of worry about death. Younger age and poorer physical well-being have been reported to be risk factors for increased worry about death in ovarian cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy (39). Risk factors for worry about death in thyroid cancer survivors are not known and may need to be formally explored in another study, particularly if our preliminary findings on death worry are confirmed.

Some strengths of our study include its relatively large sample size, the use of a validated questionnaire on survivor concerns, an acceptable participant response rate, and relatively few missing responses to questions on survivor concerns. Some limitations include potential bias in the study population because individuals with greater distress may have been more likely to become members of the group. Furthermore, all measures were self-reported by patient participants, and we did not confirm thyroid cancer disease stage, related investigations, treatments, or proceedings of physician visits through medical record review. We also cannot confirm that the questions, particularly relating to thyroid cancer history or tests, were interpreted correctly by participants. Lack of disease stage data at diagnosis is an important limitation. Our comparisons with mixed oncology populations were based on published historical data, so our results need to be confirmed. Furthermore, the cross-sectional design of our study precluded us from ascertaining the natural history of cancer-related worry within individuals over time. We also lacked information on the demographic characteristics of nonresponders, such that a meaningful comparison of responders and nonresponders was not possible. The limited number of individuals with recurrent/persistent disease is another limitation, warranting confirmation of our findings in a study specifically focused on that group. Our analysis did not include statistical analysis of interactions between variables, something that requires exploration in future prospective studies. Given the exploratory nature of the analysis looking into correlates of overall ASC score, we did not adjust the results for nonresponses. Moreover, the life consequences of various degrees of worry measured by the ASC questionnaire are not known, and we do not know the quality of life implications on individual patients in our study.

In summary, we identified a high degree of disease-related worry among thyroid cancer survivors comparable to that reported in the general oncology survivor populations. Furthermore, cancer-related worry was greatest in younger survivors and those with either confirmed or suspected disease persistence/recurrence. Marital status, parenthood, and time since thyroid cancer diagnosis were also associated with increased worry. More research is needed to confirm these findings and to develop effective preventative and management strategies for those at risk.

Acknowledgments

Financial operating grant support for this study was provided by the University Health Network Thyroid Endowment Fund. A.S. currently holds a Chair in Health Services Research from Cancer Care Ontario, funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care. The funding agencies had no role in the design, execution, or presentation of the results of this study.

The results of this study were presented in part at the 82nd Annual Meeting of the American Thyroid Association in Quebec City, Canada, in September 2012 and at the 96th Annual Meeting of The Endocrine Society in Chicago, Illinois, in June 2014. An interim analysis of data from this study was presented by L.B., in fulfilling requirements for the Determinants of Community Health II course of University of Toronto Medical School (Wightman Berris Academy).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have no commercial competing interests to disclose relating to this manuscript. R.B. is an unpaid volunteer and president of a thyroid cancer support group—Thyroid Cancer Canada.

Footnotes

- CI

- confidence interval

- RAI

- radioactive iodine

- RC

- regression coefficient.

References

- 1. Canadian Cancer Society, Statistics Canada, Public Health Agency of Canada, and Provincial/Territorial Cancer Registries. Canadian Cancer Statistics. 2014. http://www.cancer.ca/∼/media/cancer.ca/CW/cancer%20information/cancer%20101/Canadian%20cancer%20statistics/Canadian-Cancer-Statistics-2014-EN.pdf Accessed October 13, 2014.

- 2. Guay B, Johnson-Obaseki S, McDonald JT, Connell C, Corsten M. Incidence of differentiated thyroid cancer by socioeconomic status and urban residence: Canada 1991–2006. Thyroid. 2014;24:552–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shaw A, Semenciw R, Mery L. Cancer in Canada fact sheet series #1 - thyroid cancer in Canada. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2014;34:64–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Cancer Institute. Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results. 2013 SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Thyroid Cancer. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/thyro.html Accessed July 18, 2014.

- 5. Davies L, Welch HG. Current thyroid cancer trends in the United States. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140:317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen AY, Jemal A, Ward EM. Increasing incidence of differentiated thyroid cancer in the United States, 1988–2005. Cancer. 2009;115:3801–3807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aschebrook-Kilfoy B, Kaplan EL, Chiu BC, Angelos P, Grogan RH. The acceleration in papillary thyroid cancer incidence rates is similar among racial and ethnic groups in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2746–2753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Albores-Saavedra J, Henson DE, Glazer E, Schwartz AM. Changing patterns in the incidence and survival of thyroid cancer with follicular phenotype–papillary, follicular, and anaplastic: a morphological and epidemiological study. Endocr Pathol. 2007;18:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aschebrook-Kilfoy B, Schechter RB, Shih YC, et al. The clinical and economic burden of a sustained increase in thyroid cancer incidence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:1252–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:300–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ness S, Kokal J, Fee-Schroeder K, Novotny P, Satele D, Barton D. Concerns across the survivorship trajectory: results from a survey of cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40:35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gotay CG, Pagano IS. Assessment of Survivor Concerns (ASC): a newly proposed brief questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sung TY, Shin YW, Nam KH, et al. Psychological impact of thyroid surgery on patients with well-differentiated papillary thyroid cancer. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1411–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Herschbach P, Berg P, Dankert A, et al. Fear of progression in chronic diseases: psychometric properties of the Fear of Progression Questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2005;58:505–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Institute for Digital Research and Education, UCLA. 2014. SPSS Web Books, Regression with SPSS. Chapter 2 – Regression Diagnostics. http://www.ats.ucla.edu/stat/spss/webbooks/reg/chapter2/spssreg2.htm Accessed July 25, 2014.

- 17. Charter RA. Sample size requirements for precise estimates of reliability, generalizability, and validity coefficients. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1999;21:559–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Howard-Anderson J, Ganz PA, Bower JE, Stanton AL. Quality of life, fertility concerns, and behavioral health outcomes in younger breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:386–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Janz NK, Hawley ST, Mujahid MS, et al. Correlates of worry about recurrence in a multiethnic population-based sample of women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2011. 1;117:1827–1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, Peters ML, de Rijke JM, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J. Concerns of former breast cancer patients about disease recurrence: a validation and prevalence study. Psychooncology. 2008;17:1137–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Champion VL, Wagner LI, Monahan PO, et al. Comparison of younger and older breast cancer survivors and age-matched controls on specific and overall quality of life domains. Cancer. 2014;120:2237–2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ziner KW, Sledge GW, Bell CJ, Johns S, Miller KD, Champion VL. Predicting fear of breast cancer recurrence and self-efficacy in survivors by age at diagnosis. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2012;39:287–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lebel S, Beattie S, Arès I, Bielajew C. Young and worried: age and fear of recurrence in breast cancer survivors. Health Psychol. 2013;32:695–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arès I, Lebel S, Bielajew C. The impact of motherhood on perceived stress, illness intrusiveness and fear of cancer recurrence in young breast cancer survivors over time. Psychol Health. 2014;29:651–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Crist JV, Grunfeld EA. Factors reported to influence fear of recurrence in cancer patients: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2013;22:978–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koch L, Jansen L, Brenner H, Arndt V. Fear of recurrence and disease progression in long-term (≥ 5 years) cancer survivors–a systematic review of quantitative studies. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Phillips KM, McGinty HL, Gonzalez BD, et al. Factors associated with breast cancer worry 3 years after completion of adjuvant treatment. Psychooncology. 2013;22:936–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hoffman KE, McCarthy EP, Recklitis CJ, Ng AK. Psychological distress in long-term survivors of adult-onset cancer: Results from a national survey. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1274–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zeltzer LK. Cancer in adolescents and young adults psychosocial aspects. Long-term survivors. Cancer. 1993;71(10 suppl):3463–3468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Semple CJ, McCance T. Parents' experience of cancer who have young children: a literature review. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33:110–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lampic C, Wennberg A, Schill JE, Brodin O, Glimelius B, Sjödén PO. Anxiety and cancer-related worry of cancer patients at routine follow-up visits. Acta Oncol. 1994;33(2):119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cannon AJ, Darrington DL, Reed EC, Loberiza FR., Jr Spirituality, patients' worry, and follow-up health-care utilization among cancer survivors. J Support Oncol. 2011;9:141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lebel S, Tomei C, Feldstain A, Beattie S, McCallum M. Does fear of cancer recurrence predict cancer survivors' health care use? Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:901–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Janz NK, Leinberger RL, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Hawley ST, Griffith K, Jagsi R. Provider perspectives on presenting risk information and managing worry about recurrence among breast cancer survivors [published online July 23, 2014]. Psychooncology. doi:10.1002/pon.3625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Forsythe LP, Alfano CM, Leach CR, Ganz PA, Stefanek ME, Rowland JH. Who provides psychosocial follow-up care for post-treatment cancer survivors? A survey of medical oncologists and primary care physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2897–2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Banach R, Bartès B, Farnell K, et al. Results of the Thyroid Cancer Alliance international patient/survivor survey: psychosocial/informational support needs, treatment side effects and international differences in care. Hormones (Athens). 2013;12:428–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goldfarb M, Casillas J. Unmet information and support needs in newly diagnosed thyroid cancer: comparison of adolescents/young adults (AYA) and older patients. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8:394–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Papaleontiou M, Banerjee M, Yang D, Sisson JC, Koenig RJ, Haymart MR. Factors that influence radioactive iodine use for thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2013;23(2):219–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shinn EH, Taylor CL, Kilgore K, et al. Associations with worry about dying and hopelessness in ambulatory ovarian cancer patients. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7(3):299–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]