Abstract

β-catenin signaling has recently been tied to the emergence of tolerogenic dendritic cells (DC). Here we demonstrate a novel role for β-catenin in directing DC subset development through IRF8 activation. We found that splenic DC precursors express β-catenin, and DC from mice with CD11c-specific constitutive β-catenin activation upregulated IRF8 through targeting of the Irf8 promoter, leading to in vivo expansion of IRF8-dependent CD8α+, plasmacytoid, and CD103+CD11b− DC. β-catenin-stabilized CD8α+ DC secreted elevated IL-12 upon in vitro microbial stimulation, and pharmacological β-catenin inhibition blocked this response in WT cells. Upon infections with Toxoplasma gondii and vaccinia virus, mice with stabilized DC β-catenin displayed abnormally high Th1 and CD8+ T lymphocyte responses, respectively. Collectively, these results reveal a novel and unexpected function for β-catenin in programming DC differentiation towards subsets that orchestrate proinflammatory immunity to infection.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DC) critically bridge innate and adaptive immunity through their exquisite capacity to drive antigen-specific T cell activation and effector subset differentiation. Furthermore, DC are central players in determining tolerance versus immunity during inflammation and infection (1). DC are a heterogeneous population of cells with varying surface markers and transcription factor requirements. All originate from a common myeloid progenitor (CMP), but they subsequently differentiate into distinct subsets, including monocyte-derived DC (moDC), conventional DC (cDC), and plasmacytoid DC (pDC). Many elegant studies have identified phenotypic and functional differences amongst these subsets, but identifying factors determining control points of DC subset generation is a continuing focus of intense interest. Several key cytokines and transcription factors have been implicated in controlling DC developmental pathways (2), and recent gene mapping studies have begun to elucidate the order in which these factors become expressed (3, 4). For example, transcription factor Batf3 is involved in generation of splenic CD8α+ DC, while IRF4 is important in differentiation of CD11b+CD103+ DC in the intestinal lamina propria (5, 6). Recently, Zbtb46 was identified as a global transcription factor necessary for generation of cDC(3). Nevertheless, a thorough understanding of the mechanisms of DC differentiation and the signals that direct branch points leading to distinct subsets remains incomplete.

β-catenin is the primary mediator of the Wnt signaling pathway and is critical for numerous cellular functions, including hematopoietic cell fate determination and proliferation (7, 8). Cytosolic β-catenin levels are normally maintained at low levels through continual phosphorylation by the serine threonine kinases glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3β and casein kinase (CK) I-α, which cooperate to promote its ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation. Activating Wnt ligands trigger disassembly of the complex that coordinates these kinases, leaving β-catenin unphosphorylated, in turn enabling nuclear translocation for transcriptional activity in association with T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor (Tcf/Lef) transcription factors (9). While normally associated with embryonic development and tumorigenesis (10), β-catenin is increasingly being recognized for its role in immunity (11). This is particularly the case for DC, where β-catenin signaling was first implicated in cluster disruption-mediated maturation towards a tolerogenic phenotype during in vitro culture (12). Moreover, β-catenin was found to be involved in the generation or maintenance of tolerogenic DC subsets in the intestinal mucosa (13).

Here, we provide surprising new insight into the role of β-catenin in DC function by employing transgenic mice with a CD11c-specific deletion in the third exon of the β-catenin gene. The exon 3 fragment encodes the β-catenin amino acid sequence that is targeted for GSK-3β-mediated serine threonine phosphorylation and subsequent degradation. Removal of this region through Cre-lox mediated excision therefore results in phosphorylation-resistant and constitutively active β-catenin (14). We made the unexpected discovery that β-catenin stabilization in DC results in selective expansion of steady-state levels of splenic CD8α+ DC, pDC, and peripheral CD103+ DC. These DC subsets share a dependence on IRF8 for their differentiation, and in accordance with this observation, we show that constitutive β-catenin signaling increases IRF8 expression by these DC subsets via enhanced targeting of the Irf8 promoter. We employed infections with the intracellular protozoan Toxoplasma gondii and vaccinia virus to determine the in vivo consequences of DC-specific β-catenin stabilization. In accord with the known role of CD8α+ DC as an IL-12 source and driver of Th1 responses during T. gondii infection (15), the parasite triggered an abnormally strong Th1 response associated with overproduction of IL-12 and IFN-γ. Immunity to vaccinia virus is known to require a DC-mediated cross-presentation pathway (16). As such, vaccinia infection in mutant mice triggered enhanced expansion and activation of virus-specific CD8+ T cells. Our results uncover a new role for β-catenin in controlling IRF8 expression in DC, thereby revealing this transcription factor as a key player regulating IRF8-driven DC differentiation and proinflammatory function.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All experiments in this study were performed strictly according to the recommendations of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Cornell University (permit number 1995–0057). All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering during the course of these studies.

Mice and infections

Female Swiss Webster mice (6–8 weeks of age) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), and female C57BL/6 were purchased from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY). C57BL/6-Tg (TcraTcrb)425Cbn/J (OT-II) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory and maintained as a breeding colony at Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. The β-catenin Ex3fl/fl mice were kindly provided by M. M. Taketo (Kyoto University) and were maintained as breeding colonies crossed to CD11c-cre expressing mice at the Transgenic Mouse Core Facility at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. Cre+ offspring (Ex3DC−/− mice) were identified by PCR amplification of the Cre gene from genomic DNA isolated from tail snips. Infections were initiated in 8–12 week old mice. T. gondii infections were performed by intraperitoneal inoculation of 25 cysts of the type II ME49 strain. Cysts were isolated from chronically infected Swiss Webster mice by homogenization of whole brain in sterile PBS. Alternatively, mice were inoculated with 2×105 pfu of recombinant vaccinia virus expressing MHCI-restricted HSV gB498-505 (VACV-gB) by intraperitoneal injection (17). VACV-gB was maintained in 143B cells for the generation of viral stocks.

Preparation and purification of leukocytes

Splenocyte single cell suspensions were prepared by crushing spleens between sterile glass slides and filtering the resulting suspension through 40 μM filters. For lung leukocytes, lung tissue was minced with sterile razor blades and incubated with collagenase type IV (Sigma) in a 37°C water bath for 30 min with frequent agitation. The resulting digest was passed through a 40-μM filter to create a single cell suspension. A single round of positive selection using CD11c+ magnetic bead sorting was performed for purification of total splenic DC from single cell suspensions (Stem Cell Technologies), while two-step magnetic bead sorting, with an initial negative selection to enrich for DC followed by CD8α+ positive selection (Miltenyi Biotec), was performed to isolate CD8α+ splenic DC.

In vitro culture of bone marrow-derived DC and MutuDC1940 cells

Bone marrow-derived DC were cultured as described previously (18). Briefly, femurs of Ex3fl/fl, Ex3DC−/−, or C57BL/6 mice were flushed with PBS and cultured for 9 days in media containing 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone), 100 U/ml penicillin (Life Technologies), 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin (Life Technologies), 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), and 20 ng/ml GM-CSF (Peprotech). Cells were harvested from the plates with gentle pipetting and cultured as indicated. Flt3L BMDC cultures were performed by flushing femurs with PBS, lysing red blood cells with ACK lysis buffer (Life Technologies), and plating cells in RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 25 mM HEPES (Life Technologies), 100 U/ml penicillin (Life Technologies), 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin (Life Technologies), and 100 ng/ml murine Flt3L (Peprotech). Cells were cultured for 9 days at 37°C. MutuDC1940 cells, kindly provided by Dr. Hans Acha-Orbea (University of Lausenne), were grown in a monolayer in media containing 8% fetal calf serum (Hyclone), 10 mM HEPES (Life Technologies), 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 U/ml penicillin (Life Technologies), and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin (Life Technologies). Cells were harvested by 10 min incubation with PBS and 5 mM EDTA.

Western blotting

To validate nuclear translocation of β-catenin in Ex3DC−/− mice, BMDC were subjected to nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation following the manufacturer’s guidelines (Active Motif). Resulting nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins were diluted in reducing SDS sample buffer and separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. Separated proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose and blocked for 1 hr at room temperature in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 5% nonfat dry milk (TBST). Following 3 washes in TBST, blots were incubated overnight in primary antibody diluted in TBST containing 5% BSA. Blots were subsequently washed in TBST and incubated for 1 hr with anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase-conjugated (HRP) diluted in TBST containing 5% nonfat dry milk. Following 5 washes in TBST, blots were developed and imaged using a chemiluminescent detection system (Thermo Scientific). Anti-β-catenin and anti-PARP were purchased from Cell Signaling, and anti-Rab5a was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions were washed in PBS prior to resuspension in Zombie Aqua viability dye (BioLegend) for 15 min at room temperature to exclude dead cells. Primary antibodies (anti-CD11c FITC, eFluor610, or APC; anti-CD8α Pacific Blue or APC-Cy7; anti-CD4 PerCP-Cy5.5 or FITC; anti-PDCA-1 APC or PE; anti-NK1.1 FITC or APC; anti-CD11b FITC or APC-Cy7; anti-CD24 Pacific Blue; anti-CD103 PE; anti-B220 PE; anti-CD3 FITC; anti-Gr1 FITC; anti-CD127 PerCP-Cy5.5; anti-CD16/32 eFluor450; anti-CD19 FITC; anti-CD135 PE; anti-Sca1 PE-Cy7; anti-CD117 APC-Cy7; anti-MHCII PE or FITC) resuspended in ice-cold FACS buffer (1% bovine serum albumin/0.01% NaN3 in PBS) were added directly to the cells for 30 min. Tetramer staining for Tgd057+CD8+ T cells (provided by George Yap, New Jersey School of Medicine and Dentistry), CD4Ag28m+CD4+ T cells (provided by Marion Pepper, University of Washington), and gB-8p:Kb+CD8+ T cells (NIH Tetramer Core Facility, Emory University) was performed by labeling at room temperature for 1 hour. For intracellular staining, cells were fixed using the FoxP3/transcription factor staining kit fixative (eBioscience) and subsequently incubated with primary antibodies resuspended in the FoxP3/transcription factor permeabilization buffer (eBioscience). Antibodies used for intracellular cytokine staining include anti-IRF8 PerCP, and anti-IRF4 eFluor450 (eBioscience); anti-β-catenin Alexa-647 (Cell Signaling). IgG isotype controls (eBioscience) were used for each fluorophore. For IFN-γ staining following T. gondii infection, cells were incubated for 4 hr with Brefeldin-A (eBioscience; 10 ug/ml), PMA (Sigma; 10 ng/ml), and ionomycin (Sigma; 1 ug/ml), while for VACV-gB infection, splenocytes were restimulated with gB-8p peptide (SSIEFARL; 10−7 M) for 5 hr in the presence of Brefeldin-A. Cells were then fixed with the FoxP3/transcription factor staining kit fixative (eBioscience) and subsequently incubated with anti-IFN-γ (PE-Cy7, BioLegend; PE, eBioscience). All samples were run on an LSRII flow cytometer (BD), and the data were analyzed using FlowJo software (FlowJo, Ashland, OR).

Identification of bone marrow and splenic DC progenitors

Bone marrow was flushed from the femur and tibia of Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− mice and broken up with a 21-gauge syringe. Bone marrow and splenocyte pellets were lysed with ACK buffer and passed through a 40-μm filter to generate single cell suspensions. For precursor staining, a FITC lineage cocktail was created in-house (anti-NK1.1, anti-CD11b, anti-Gr1, anti-Ter119, anti-CD3, anti-MHCII, anti-CD19). Gating strategies were adopted from a previous study (3), whereby CMP were defined as Lin−Sca1−CD127−CD117hiCD11c−CD135+CD16/32−, GMP as Lin-Sca1−CD127−CD117hiCD11c−CD135−CD16/32+, CDP as Lin−Sca1−CD127−CD117intCD11c−CD135+CD16/32−, and pre-cDC as Lin−Sca1−CD127−CD117loCD16/32−CD11c+CD135+. Pre-CD8α+ DC were defined as CD11c+CD8α−B220−CD24+ as previously described (19).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Recombinant murine Flt3 ligand bone marrow cultures from Ex3DC−/− mice (1×107) were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde (Pierce) at room temperature for 6 min, and chromatin/protein complexes were prepared following the manufacturer’s instructions (Millipore). Shearing was performed using a Bioruptor UCD-200 sonicator (Life Technologies) in an ice slurry, with a program of 30 seconds on and 60 seconds off for 30 min. Protein immunoprecipitation was performed overnight with agitation at 4°C using protein G magnetic beads and 2 μg of a rabbit monoclonal β-catenin antibody or rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling). The following day, samples were proteinase K digested at 65°C to free the DNA, and semi-quantitative PCR was performed to amplify a region of the Irf8 promoter containing a Wnt/β-catenin binding site (Forward, CACACTGGGTGGACATTTG; Reverse, ACCTTATAAGCGTATGCAGATT). DNA levels were normalized to 1% input chromatin.

ICG-001 inhibition

BMDC (1×106) or MutuDC1940 cells (2×105) were plated and cultured overnight. The following day, the cells were cultured with 5 or 20 μM ICG-001 (Selleck Chemicals), respectively, or DMSO control for 5 hr or overnight at 37°C. Cells were surface stained for CD11c and/or CD24, fixed, intracellularly stained for IRF8, IRF4, and β-catenin, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Alternatively, DC were resuspended in Trizol (Life Technologies) for quantitative PCR analysis of Irf8 and Axin2 mRNA transcripts.

Measurement of mRNA by quantitative PCR

RNA was isolated from CD11c+ splenocytes magnetically sorted from naïve Ex3DC−/− and Ex3fl/fl mice or from BMDC by resuspension in Trizol reagent (Life Technologies). RNA was converted to cDNA (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD) and assayed for gene expression by SYBR green technology (Quanta Biosciences). Primers were designed to span exons by Integrated DNA Technologies. The following primer sequences were used: Irf8 Forward, TGCCACTGGTGACCGGATAT; Reverse, GACCATCTGGGAGAAAGCTGAA; Nfil3 Forward, GAACTCTGCCTTAGCTGAGGT; Reverse, ATTCCCGTTTTCTCCGACACG; Id2 Forward, ATGAAAGCCTTCAGTCCGGTG; Reverse, AGCAGACTCATCGGGTCGT; Batf3 Forward, CAGACCCAGAAGGCTGACAAG; Reverse, CTGCGCAGCACAGAGTTCTC; Axin2 Forward, TAGGTTCCGGCTATGTCTTTG; Reverse, TGTTTCTTACTCCCCATGCG. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping gene. Gene expression was normalized to Ex3fl/fl samples or DMSO controls.

Cytokine measurement

IFN-γ IL-12p70 and TNF-α secretion were assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) following the manufacturer’s instructions (eBioscience) following culture with media, LPS (100 n/gml), or soluble tachyzoite antigen (50 μg/ml) prepared as previously described (20). IL-12p40 secretion was measured using an in-house ELISA(21).

Parasite burden measurement

Levels of T. gondii DNA were measured as described previously (22). Briefly, spleens were homogenized, and DNA was extracted using a tissue extraction kit (Omega Biotech). The T. gondii B1 gene and the host argininosuccinate lyase (ASL) gene were amplified by quantitative real-time PCR, and resulting ct values were compared to standard curves developed from 10-fold serial dilutions of parasite DNA and splenocyte DNA, respectively. The parasite burden is displayed as the ratio of T. gondii DNA to host DNA.

Statistical analyses

Differences between groups were analyzed by Student’s t test. Expression of β-catenin among splenic DC subsets was analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by a Newman-Keuls post-test. A Kaplan-Meier curve (Logrank test) was used to calculate differences in survival between Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− mice. P values were considered statistically significant at <0.05 and were designated *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; *** p<0.001.

Results

β-catenin is selectively enriched in splenic DC precursors and mature DC

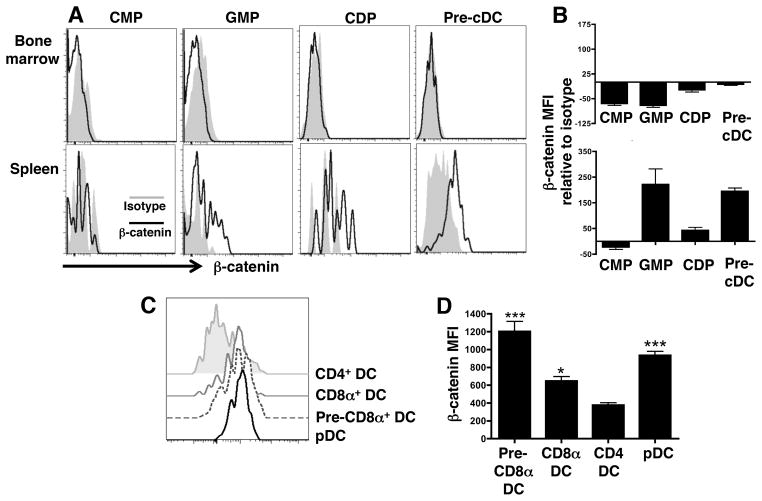

Common myeloid progenitors, (CMP), granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMP), common dendritic progenitors (CDP), and pre-conventional dendritic cells (pre-cDC) represent different stages of hematopoiesis towards the dendritic cell (DC) lineage and can be distinguished by surface marker expression (Supplemental Fig. 1) (3, 23). While CMP can develop into any cell of the myeloid lineage and GMP can ultimately become macrophages, granulocytes, or DC, CDP and pre-cDC are restricted to the DC lineage, although they remain immature until terminal differentiation within the tissue (23). To investigate the role of β-catenin at these different stages of DC differentiation, β-catenin expression levels were determined among DC precursor populations in the bone marrow and spleens of wild-type (WT) mice by flow cytometry. We were able to detect each precursor population in both tissues, although the overall levels of precursors, particularly CDP, were far lower in the spleen (Supplemental Fig. 1). Interestingly, β-catenin was undetectable in the precursor populations in the bone marrow and in splenic CMP. However, β-catenin expression was increased in splenic GMP, CDP, and pre-cDC with GMP and pre-cDC displaying the highest levels (Fig. 1A, 1B). These results provide evidence that the β-catenin signaling axis may be active in later stages of DC development.

FIGURE 1.

β-catenin is upregulated in splenic DC precursors and mature DC subsets. (A and B) Flow cytometric analysis of β-catenin expression by mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) in DC precursors from the bone marrow and spleen of naïve WT mice compared to isotype control staining. The data are representative of 2 independent experiments (n=4 mice per group). (C) Comparison of β-catenin expression levels among splenic DC subsets by flow cytometry. (D) MFI of β-catenin expression among different DC subsets. Statistics are relative to β-catenin expression in CD4+ DC. The data are representative of 3 independent experiments (n=5 mice per group). *, p<0.05; ***, p<0.001.

To ask if β-catenin expression was maintained in mature tissue-resident DC, levels were measured in splenic conventional DC (cDC) subsets and plasmacytoid DC (pDC). Compared to the CD4+ splenic cDC subset, immediate CD8α+ DC precursors (pre-CD8α+ DC), which are defined by CD24 expression (19), CD8α+ DC, and pDC were all significantly enriched for β-catenin expression, where pre-CD8α+ DC and pDC expressed the highest levels (Fig. 1C, 1D). These data demonstrate that β-catenin is selectively induced in particular DC subsets and that, based upon protein expression levels, β-catenin signaling is more active in tissue-resident DC progenitors and mature DC than in bone marrow cells.

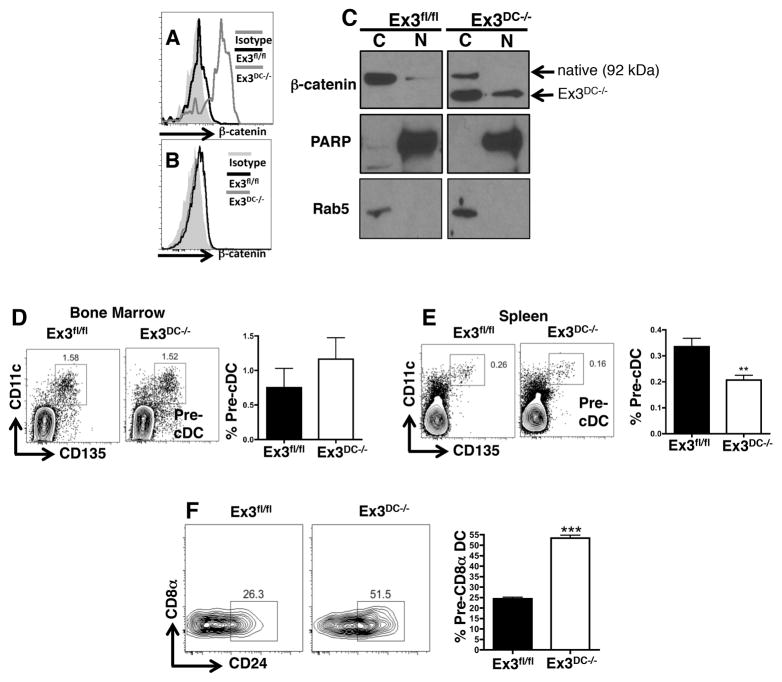

β-catenin stabilization directs splenic DC progenitors towards CD8α+ DC

Because β-catenin was clearly expressed by DC progenitors, we next investigated the effect of β-catenin stabilization on the outcome of DC differentiation. To address this, mice floxed for exon 3 of the β-catenin gene were crossed with CD11c-cre animals, resulting in Cre-positive progeny whose CD11c+ cells possessed an exon 3-deleted β-catenin form resistant to phosphorylation-induced degradation (14). Flow cytometric analysis of CD11c+ splenic DC from Cre-positive offspring (Ex3DC−/− mice) demonstrated high β-catenin expression levels compared to Cre-negative littermate controls (Ex3fl/fl mice), indicating accumulation of β-catenin protein upon exon 3 deletion (Fig. 2A). This was confirmed to be specific to CD11c+ cells, as CD4+ T cells from Ex3DC−/− mice did not display upregulation of β-catenin compared to CD4+ T cells from Ex3fl/fl mice (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, upon cytoplasmic and nuclear fractionation, Ex3DC−/− BMDC were found to be enriched for a truncated form of nuclear β-catenin compared to Ex3fl/fl DC, confirming enhanced nuclear translocation of protein (Fig. 2C). Thus, CD11c-directed exon 3 deletion results in β-catenin accumulation and nuclear translocation.

FIGURE 2.

β-catenin stabilization directs splenic DC progenitors towards CD8α+ DC development. (A) Intracellular β-catenin expression in naïve Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− splenic CD11c+ cells. (B) Intracellular β-catenin levels in splenic CD4+ T cells isolated from Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− mice. The data show results from an individual mouse that is representative of of at least 3 experiments with 3–5 mice per group. (C) Western blot analysis of β-catenin in bone marrow-derived DC from Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− mice following cytoplasmic (C) and nuclear (N) fractionation. Antibodies against PARP and Rab5 were used for nuclear and cytoplasmic loading controls, respectively. The data are from 1 independent trial. (D and E) Comparison pre-cDC populations from the (D) bone marrow and (E) spleen of Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− mice by flow cytometry. Numbers in representative plots represent percentages of relevant populations within the indicated gate. Bar graphs show mean percentages plus standard error (S.E.) of relevant populations. The data represent the combination of 2 independent experiments (n=10 mice per group). (F) Levels of splenic pre-CD8α+ DC, defined as CD11c+CD8α−B220−CD24+, in Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− mice by flow cytometry. The data are representative of 3 independent experiments, each involving 4–5 mice per group. **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

To determine the effect of β-catenin stabilization on DC precursor levels, bone marrow and splenic pre-cDC were quantified from Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− mice by flow cytometry. Consistent with the failure to detect β-catenin in bone marrow precursors (Fig. 1B), no differences were observed in the levels of DC progenitors in the bone marrow following β-catenin stabilization (Fig. 2D). However, β-catenin stabilization in Ex3DC−/− mice led to significantly fewer splenic pre-cDC compared to Ex3fl/fl littermate controls (Fig. 2E), suggesting that constitutive β-catenin signaling was depleting this precursor pool. We next asked whether this decrease in progenitors influenced later stages of DC development, in particular by quantifying levels of pre-CD8α+ DC. Indeed, DC-specific β-catenin activation resulted in a 2-fold increase in splenic pre-CD8β+ DC compared to WT controls (Fig. 2F). These data suggest that β-catenin signaling drives the differentiation of splenic DC progenitors into the immediate precursors of mature CD8β+ DC.

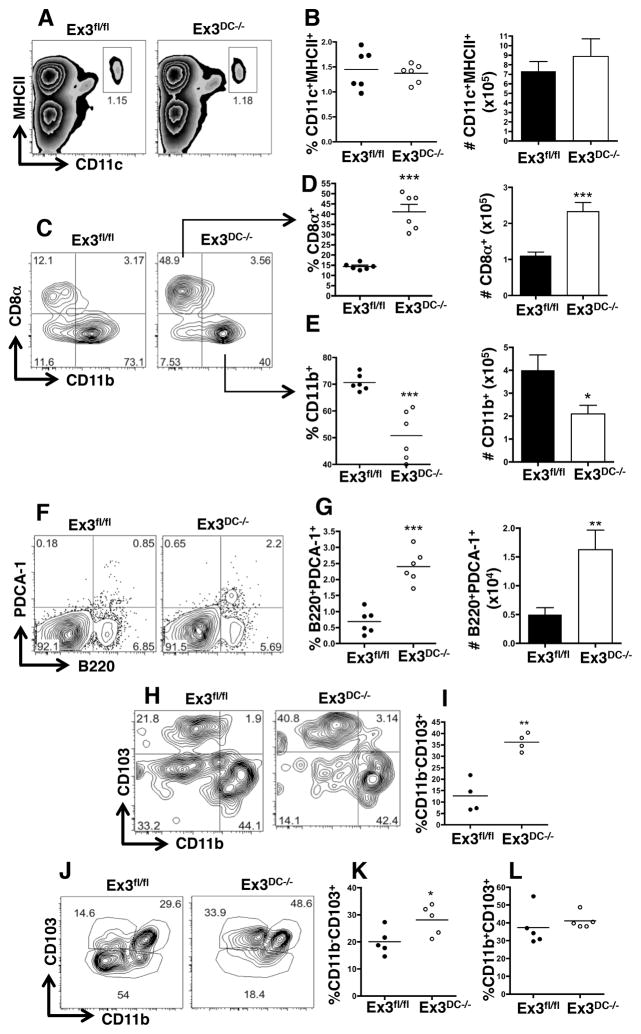

β-catenin stabilization expands splenic and peripheral dendritic cell populations

Since β-catenin signaling influenced the levels of splenic DC progenitors, we next focused on the outcome of β-catenin stabilization on steady-state levels of mature tissue-resident DC. We first observed that the percentage and total number of CD11c+MHCII+ cells were unaffected in Ex3DC−/− mice (Fig. 3A, 3B). However, further analysis revealed a striking expansion of the CD8α+ DC subset and a concomitant decrease in CD11b+ DC (Fig. 3C, 3E). Furthermore, plasmacytoid DC (pDC), as defined by expression of B220 and PDCA-1, were also expanded in the spleens of Ex3DC−/− mice (Fig. 3F, 3G). These collective data suggest that β-catenin exerts major effects on the generation of specific splenic DC populations and are consistent with the finding that these particular subsets upregulate β-catenin during development (Fig. 1D).

FIGURE 3.

β-catenin stabilization expands splenic CD8α+ and plasmacytoid DC populations. (A–G) Mature DC subset analysis of naïve Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− splenocytes by flow cytometry. (A and B) Percentage and total number of CD11c+ cells in Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− spleens. (C–E) Percentage and total number of (C and D) CD8α+ DC and (C and E) CD11b+ DC in naïve Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− spleens. The data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments (n=3–5 mice per group). (F and G) Percentage and total number of B220+PDCA-1+ plasmacytoid DC in naïve Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− spleens. (H and I) Mature DC subset analysis of naïve Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− lung tissue by flow cytometry. (H) Plots from representative mice and (I) percentage of CD103+CD11b− lung DC for multiple mice are shown. (J–L) Mature DC subset analysis of naïve Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− intestinal lamina propria by flow cytometry. (J) Plots from representative mice and percentages of (K) CD103+CD11b− and (L) CD103+CD11b+ intestinal DC for multiple mice are shown. Dots in relevant graphs represent results from individual mice. Bar graphs display means and standard errors of individual mice. The data are representative of at least 2 independent experiments (n=3–5 mice per group). *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

Peripheral DC can be subdivided into CD103+CD11b−, CD103+CD11b+, and CD103−CD11b+ DC and, much like splenic DC subsets, these DC display differential transcription factor requirements and functions (6, 24). Importantly, CD103+CD11b− DC found in non-lymphoid tissues, such as the intestine and the lung, exhibit a similar dependence upon Batf3 as the CD8α+ DC subset, leading to the conclusion that these two subsets are developmentally related (24). Examination of these DC subsets in Ex3DC−/− mice revealed a dramatic expansion of resident lung CD103+CD11b− DC compared to Ex3fl/fl littermate controls (Fig. 3H, 3I). Furthermore, intestinal CD103+CD11b− DC, but not CD103+CD11b+ DC, were also expanded in Ex3DC−/− mice (Fig. 3J–L). These data demonstrate that constitutive DC β-catenin signaling promotes a developmental pathway that is shared by splenic CD8α+ DC, pDC and peripheral CD103+ DC.

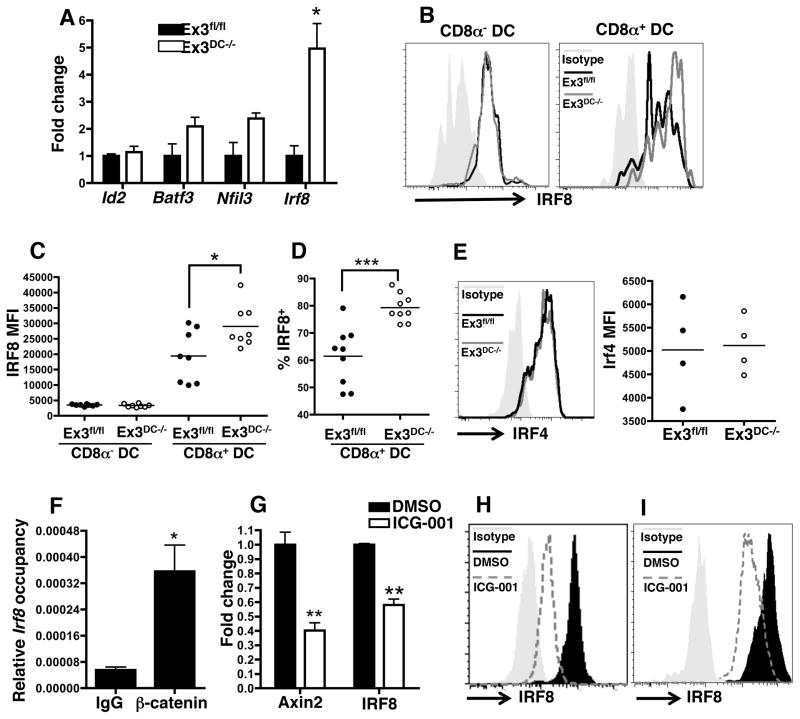

β-catenin signaling controls Irf8 expression

Genetic knockout studies have identified several transcription factors involved in CD8α DC differentiation, including Id2, Nfil3, Batf3, and Irf8 (5, 25–27). Therefore, we determined expression levels of these transcription factors amongst splenic CD11c+ cells from Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− mice. While there was no significant difference in Id2 expression, Nfil3 and Batf3 transcripts were slightly increased albeit in a statistically non-significant manner (Fig. 4A). However, there was a striking increase in Irf8 expression in the CD11c compartment upon β-catenin stabilization (Fig. 4A). We also assessed IRF8 protein expression in CD8α− and CD8α+ splenic DC in Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− mice by flow cytometry. Levels of IRF8 were relatively low in CD8α− DC from both mouse strains (Fig. 4B, 4C). However, there was an increase in IRF8 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) in CD8α+ DC in both mouse strains. Furthermore, IRF8 MFI and percent positive populations were increased when comparing CD8α+ DC from Ex3DC−/− relative to Ex3fl/fl strains (Fig. 4B–D). To confirm that the effect of β-catenin stabilization was specific for IRF8, we examined expression of IRF4 and found it to be unchanged in Ex3DC−/− relative to Ex3fl/fl CD8α splenic DC (Fig. 4E). Consistent with this finding, levels of splenic CD4+ DC and intestinal CD11b+CD103+ DC, both of which are known to depend on IRF4 for development, were unchanged between Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− mice (6, 26) (Fig. 3J, 3L; data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

β-catenin signaling controls Irf8 expression. (A) Semi-quantitative PCR analysis of Nfil3, Batf3, Id2, and Irf8 mRNA in CD11c+ splenocytes magnetically purified from naïve Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− mice. mRNA levels were normalized to GAPDH. The data are representative of 2 independent experiments (n=2–3 mice per group) (B) Representative flow cytometric plots of IRF8 expression by Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− CD8α− and CD8α+ splenic DC. (C) MFI of IRF8 within Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− CD8α− and CD8α+ DC and (D) the percent of CD8α+ DC expressing IRF8 are shown. Dots represent results from individual mice. The data are the combined results of 2 experiments, and the experiment was independently performed at least 3 times (n=4–5 mice per group). (E) Representative FACS plot of IRF4 expression and IRF4 MFI in Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− CD11c+ splenocytes. The data are representative of 3 independent experiments (n=4 mice per group). (F) Chromatin immunoprecipitation of naïve Ex3DC−/− Flt3L DC cultures with control IgG or β-catenin antibody followed by quantitative PCR to determine Irf8 promoter occupancy. DNA levels were normalized to 1% input chromatin. The data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (G) Quantitative PCR analysis of Axin2 and Irf8 gene expression in BMDC following 5 hr culture with DMSO or ICG-001. Fold change is relative to DMSO control. The data are from one independent trial. (H and I) Intracellular expression of IRF8 and β-catenin following ICG-001 treatment of BMDC (H) or MutuDC1940 cells (I). The data are representative of 2 (MutuDC1940 cells) and 4 (BMDC) independent experiments with 3 replicates per treatment per experiment. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

To ask whether β-catenin targets the Irf8 promoter in vivo, chromatin immunoprecipitation assays were performed on Flt3 ligand cultures of bone marrow DC derived from Ex3DC−/− mice. β-catenin displayed a greater than 6-fold enrichment in Irf8 promoter occupancy over IgG control, suggesting a direct role for this signaling axis in Irf8 transcription (Fig. 4F). To ask if Irf8 transcription could be blocked by inhibiting β-catenin, WT BMDC were cultured with the Wnt/β-catenin inhibitor ICG-001, which competes with β-catenin for binding to its co-factor Creb-binding protein (CBP)(28). As a control, 5 hr of ICG-001 treatment led to a significant reduction in transcript levels of the known β-catenin target gene Axin2(29). Importantly, Irf8 transcripts were also significantly reduced following ICG-001 treatment (Fig. 4G). This downregulation was observed at the protein level, as IRF8 expression in BMDC was markedly decreased compared to DMSO-treated control cells by flow cytometry (Fig. 4H). Furthermore, ICG- 001 treatment of MutuDC1940 cells, a DC-derived cell line that has many characteristics of CD8α+ DC(30), also resulted in strong downregulation of IRF8 (Fig. 4I). IRF4 levels were unchanged by ICG-001 treatment, confirming the specificity of β-catenin signaling for IRF8 (data not shown). These data establish a functional link between β-catenin and IRF8 expression that controls differentiation of CD8α+ DC, pDC and peripheral CD103+ DC.

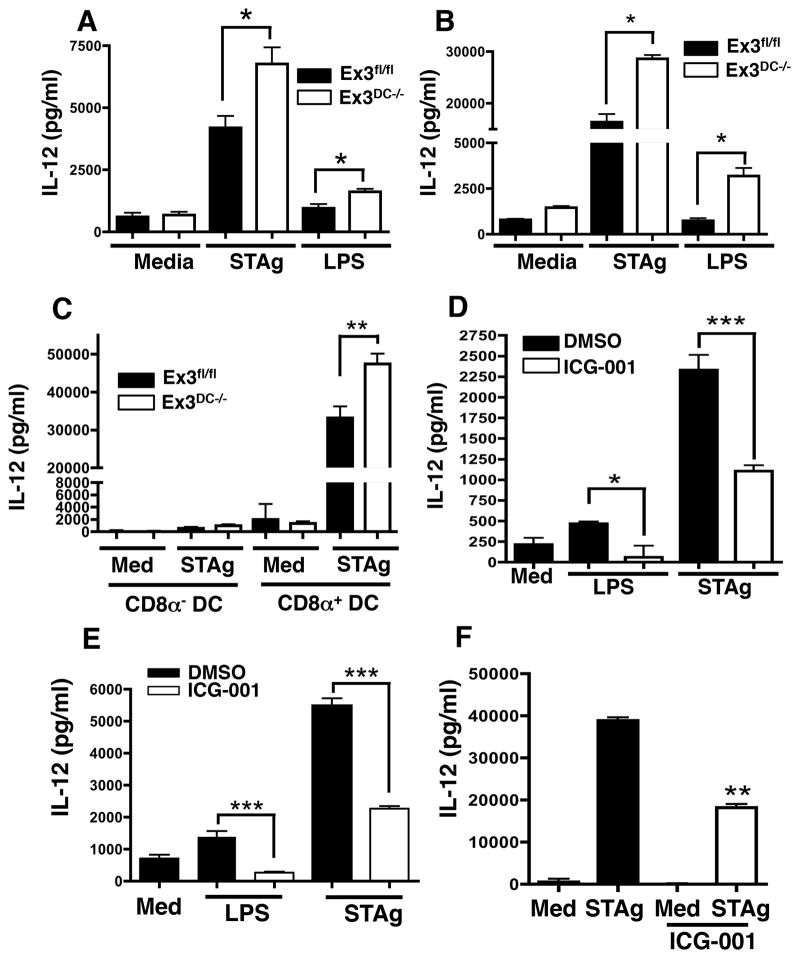

β-catenin stabilization enhances IL-12 production by CD8α+ DC

CD8α+ DC are a potent IL-12 source during infection with the Th1 pathogen Toxoplasma gondii (15). Furthermore, it was recently shown that this cytokine activity requires IRF8(31). Additionally, LPS has been shown to upregulate Irf8 expression, resulting in binding to the IL-12 promoter (32). Therefore, we wanted to determine if increased IRF8 expression in CD8α+ DC from Ex3DC−/− mice would impact their functional activity, in particular as related to IL-12 production.

To examine this, whole splenocytes from Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− mice were cultured in the presence of media, LPS, or soluble tachyzoite antigen (STAg), an antigenic preparation of T. gondii that stimulates CD8α+ DC IL-12 through the interaction between TLR11/12 and parasite profilin (31). Indeed, upon LPS or STAg stimulation, supernatants from Ex3DC−/− splenocytes contained significantly increased levels of IL-12p40 compared to Ex3fl/fl controls (Fig. 5A). To confirm that the source of IL-12 was DC, CD11c+ cells were magnetically purified (~90% purity) from Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− splenocytes and cultured with LPS and STAg. As expected, increased IL-12 secretion was again observed in Ex3DC−/− cells (Fig. 5B). These results clearly show that DC from Ex3DC−/− produce more IL-12 than cells from WT littermates. However, they leave open to question whether this is a result of an increase in the proportion of CD8α+ DC, or whether Ex3DC−/− CD8α+ DC produce increased IL-12 on a cell-to-cell basis relative to corresponding cells from Ex3fl/fl mice. Therefore, CD8α+ and CD8α− DC were magnetically purified from Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− spleens and stimulated in vitro with STAg. While IL-12 production was restricted to the CD8α+ subset, the Ex3DC−/− CD8α+ DC secreted enhanced IL-12 levels compared to Ex3fl/fl CD8α+ DC (Fig. 5C). Next, WT splenocytes were treated with the β-catenin inhibitor ICG-001 and then stimulated with STAg or LPS overnight. Inhibitor-treated cells secreted lower levels of IL-12p40 compared to DMSO-treated cells without negatively affecting viability (Fig. 5D, data not shown). Furthermore, the elevated IL-12 secretion displayed by Ex3DC−/− splenocytes over Ex3fl/fl splenocytes could be inhibited by treatment with ICG-001, further indicating that ICG-001 treatment suppresses β-catenin-dependent responses (Fig. 5E). To further implicate CD8α+ DC in these findings, we replicated these experiments in vitro using MutuDC1940 cells. Stimulation of MutuDC1940 cells with STAg resulted in extremely high IL-12 levels, consistent with their origin from splenic CD8α+ DC. Furthermore, pre-treatment of MutuDC1940 cells with ICG-001 significantly impaired the IL-12 response to STAg (Fig. 5F). Thus, β-catenin stabilization promotes both differentiation and IL-12-secreting capacity of CD8α+ DC by promoting increased Irf8 expression.

FIGURE 5.

β-catenin stabilization enhances IL-12 production by CD8α+ DC. (A) IL-12p40 production by naïve Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− splenocytes stimulated in vitro with LPS, STAg, or media control measured by ELISA. (B) IL-12p40 production by splenic CD11c+ DC magnetically purified from Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− mice stimulated in vitro with LPS, STAg, or media control measured by ELISA. (C) IL-12p40 production by CD8α+ and CD8α− DC DC purified from naïve Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− splenocytes following in vitro stimulation with media or STAg for 48 hr measured by ELISA. (D) IL-12p40 secretion by Ex3fl/fl splenocytes pre-treated with ICG-001 for 5 hr and then stimulated overnight with LPS or STAg measured by ELISA. (E) IL-12p40 production by splenocytes (106) from Ex3DC−/− mice cultured for 5 hr with 5 μM ICG-001 or DMSO and then stimulated with media, LPS (100 ng/ml), or STAg (25 μg/ml) overnight. (F) IL-12p40 production by MutuDC1940 cells (105) pre-treated with 20 μM ICG-001 or DMSO for 2 hr and then stimulated with media or STAg (25 μg/ml) overnight. The data are representative of at least 3 (A, F) and 2 (B–E) independent experiments, each involving 3–5 mice per group, except (C), which used pooled samples from 3 mice per experiment. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

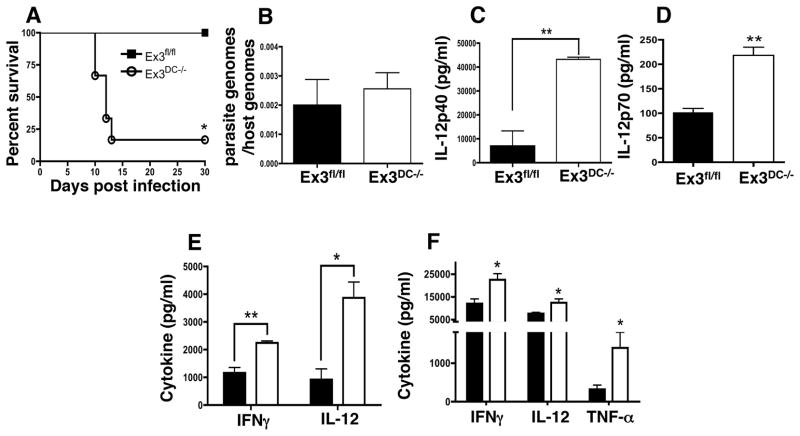

Constitutive DC β-catenin signaling promotes Th1 immunity during Toxoplasma gondii infection

As a source of IL-12 that drives Th1 activation, CD8α DC are required to control infection with Toxoplasma, yet overexpression of IL-12 and downstream proinflammatory cytokines is also lethal (15, 33). Therefore, we used intraperitoneal infection with T. gondii to evaluate the impact of DC β-catenin stabilization on host immunity. Ex3DC−/− mice began to succumb within 9 days of low dose T. gondii intraperitoneal infection, while the Ex3fl/fl littermate controls fully survived acute infection (Fig. 6A). Parasite levels in the spleen (Fig. 6B) and peritoneal cavity (data not shown) were equivalent between the genotypes, arguing that susceptibility of Ex3DC−/− mice was not due to defective control of Toxoplasma.

FIGURE 6.

Constitutive DC β-catenin signaling increases the proinflammatory cytokine response to Toxoplasma. (A) Survival of Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− mice following i.p. infection with Toxoplasma Type II strain ME49 (25 cysts) (n=4–6 mice per group). The data are representative of at least 3 experiments. (B) Quantitative PCR amplification of parasite (B1 gene) and host DNA (ASL gene) isolated from Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− spleens 9 days post-infection. Parasite load is displayed as a ratio of parasite genomes to host genomes (n=3–4 mice per group). (C) IL-12p40 production by CD11c+ DC magnetically separated from Day-6 post-infection Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− splenocytes and cultured overnight without additional stimulation (n=3 mice per group). (D) IL-12p70 production by bulk splenocytes from Day-6 post-infection Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− mice (n=3 mice per group). The data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (E) IL-12p40 and IFN-γ production by splenocytes from Day-10 post-infection Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− mice cultured for 72 hr without additional stimulation (n=3–5 mice per group). The data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (F) IL-12p40, IFN-γ, and TNF-α levels in serum collected from Day-9 post-infection Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− mice (n=3–5 mice per group). The data are representative of 2 independent experiments. The means and S.E. of individual mice are shown. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01.

Splenic DC from infected Ex3DC−/− mice secreted dramatically more IL-12 compared to Ex3fl/fl controls as measured by both p40 (Fig. 6C) and p70 (Fig. 6D) subunits and, at nearly 50 ng/ml, the level of IL-12p40 detected in Ex3DC−/− mice was approximately 5-fold over WT controls. To examine Th1 responses in these animals, Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− splenocytes from infected mice were cultured in vitro, and the supernatants were assayed for both IL-12 and IFN-γ. Accompanying increased IL-12 secretion by Ex3DC−/− splenocytes, IFN-γ levels were enhanced, suggesting elevated T and possibly NK cell activation in Ex3DC−/− mice in response to T. gondii infection (Fig. 6E). Furthermore, serum collected from infected mice revealed significantly elevated levels of IFN-γ, IL-12, and TNF-α in Ex3DC−/− mice compared to Ex3fl/fl controls (Fig. 6F), suggesting systemic hyperproduction of proinflammatory cytokines upon DC β-catenin stabilization. By contrast, IL-17 was undetectable or expressed at very low levels in splenocyte cultures or serum prepared from infected Ex3fl/fl or Ex3DC−/− mice (data not shown).

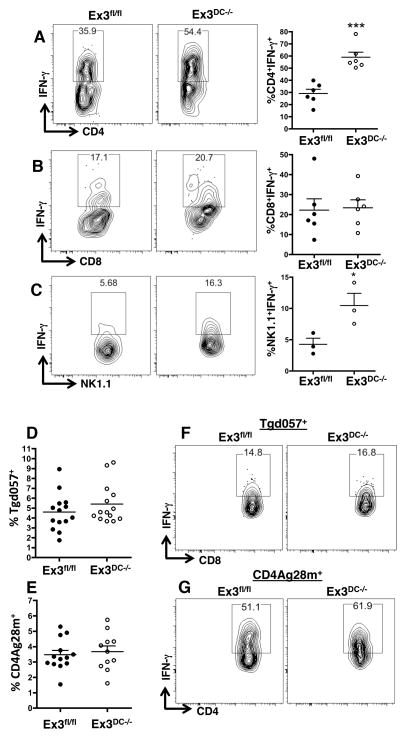

To determine the source of elevated Th1 cytokines in Ex3DC−/− mice during T. gondii infection, IFN-γ production by splenic CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and natural killer (NK) cells was assayed 8 days post-infection. Both CD4+ T cells and NK cell populations in Ex3DC−/− mice displayed a marked increase in IFN-γ responses compared to Ex3fl/fl littermate controls (Fig. 7A, 7C). Interestingly, given previous studies implicating CD8α+ DC in cross-presentation (5, 34), IFN-γ from CD8+ T cells was not significantly changed between the two genotypes (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

CD4+ T cells and NK cells, but not CD8+ T cells, overproduce IFN-γ following Toxoplasma infection in mice with constitutive DC β-catenin signaling. (A–C) Intracellular flow cytometric analysis of IFN-γ production by (A) CD4+ T cells, (B) CD8+ T cells, and (C) NK cells from Day 9 T. gondii-infected Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− spleens following 4 hr of PMA and ionomycin stimulation in the presence of Brefeldin-A. Shown are representative contour plots of individual mice and the mean ± standard error of IFN-γ levels from multiple mice. The data are representative of 3 independent experiments (CD4 and CD8) and 1 (NK) experiment. (D and E) Quantification of Toxoplasma-specific (D) Tgd057+CD8+ T cells and (E) CD4Ag28m+CD4+ T cells. Means and standard errors of individual mice are shown, and each dot represents a single mouse. (F and G) IFN-γ levels expressed by tetramer-positive CD8+ (F) and CD4+ (G) T cells following 4 hr of culture with PMA, ionomycin, and Brefeldin-A. The data are representative of 3 independent experiments (n=3 mice per group). *, p<0.05; ***, p<0.001.

We next determined whether the increase in IFN-γ could be explained by increased activation and expansion of Toxoplasma-specific T cells. We used MHCI tetramers that bind CD8+ T lymphocytes specific for the endogenous T. gondii epitope Tgd057 and MHCII tetramers that bind CD4+ T cells specific for the Toxoplasma epitope CD4Ag28m (35, 36). The frequency of parasite-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was equivalent in Ex3DC−/− and Ex3fl/fl mice (Fig. 7D, 7E). Although IFN-γ produced by antigen-specific CD8+ T cells was equivalent in Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− mice, levels of cytokine produced by tetramer-positive CD4+ T lymphocytes were increased in Ex3DC−/− relative to Ex3fl/fl mice (Fig. 7F, 7G). Therefore, in the context of T. gondii infection, DC β-catenin stabilization impacts the intensity of the CD4 and NK cell IFN-γ response, but does not have a measurable influence on IFN-γ production by CD8+ T cells.

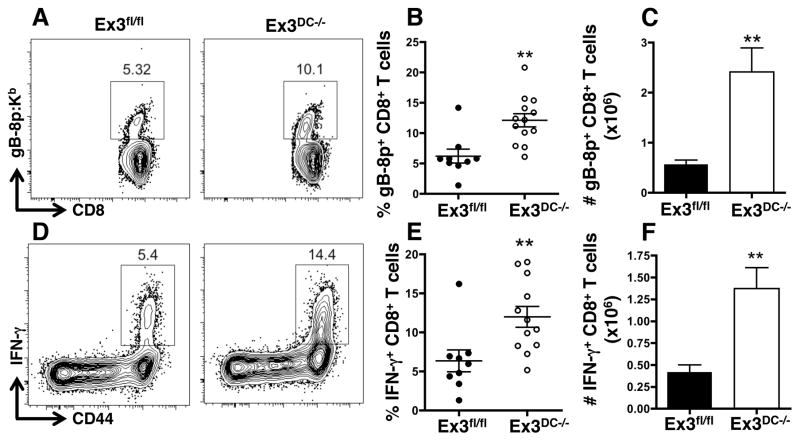

DC β-catenin signaling enhances CD8+ T cell priming during vaccinia virus infection

DC-mediated cross-presentation of exogenous antigen through the cytosolic pathway is crucial for the generation of a CD8+ T cell response against vaccinia virus (VACV) infection (16, 37). Thus, we finally asked if DC β-catenin signaling influenced DC cross-presentation in the context of VACV infection. To address this, Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− mice were infected intraperitoneally with recombinant VACV expressing the herpes simplex virus (HSV) glycoprotein B (gB) peptide (VACV-gB)(17). On day 6 post-infection, spleens were harvested, and gB-specific CD8+ T cells were quantified by flow cytometry using MHCI-restricted gB-8p:Kb tetramers. We found a striking increase in the percentage and total number of gB-specific CD8+ T cells in Ex3DC−/− mice compared to littermate controls, suggesting increased cross-presentation by β-catenin-stabilized DC (Fig. 8A–C). Furthermore, restimulation of splenocytes with gB peptide revealed significantly increased IFN-γ+CD8+ T cells in Ex3DC−/− mice, demonstrating a functional impact of DC β-catenin activation on CD8+ T cell activity (Fig. 8D–F). These results demonstrate that stabilization of DC β-catenin promotes development of CD8+ T cell responses in the context of viral infection.

FIGURE 8.

β-catenin stabilization promotes activation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells during viral infection. (A–C) Quantification of gB-8p-specific CD8+ T cells in Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− spleens 6 days post-VACV-gB infection. (A) Representative plots of MHCI-restricted gB-8p:Kb tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells, and (B) percentage and (C) total number of gB-8p:Kb+CD8+ T cells. (D–F) IFN-γ production by gB-8p-specific CD8+ T cells in Ex3fl/fl and Ex3DC−/− spleens 6 days post-VACV-gB infection. (D) Representative plots of CD8+CD44+IFN-γ+ T cells following gb-8p restimulation of splenocytes, and (E) percentage and (F) total number of gB-8p-specific CD8+CD44+IFN-γ+ T cells. The data shown are the combination of 2 independent experiments (n=9–13). **, p<0.01.

Discussion

Dendritic cell differentiation is a complex process involving an array of transcription factors and growth factor cytokines whose details are continuing to be elucidated. In this study we identify an unexpected role for β-catenin in controlling differentiation of CD8α+ DC, pDC, and developmentally related non-lymphoid CD103+ DC. This pattern of transcriptional control precisely matches that of IRF8(24, 26, 38). In support of a functional connection between β-catenin and IRF8, overexpression of β-catenin increased steady state IRF8 levels in CD8α+ DC. In addition, IL-12 production by CD8α+ DC, a known function of this cell subset, was prevented by β-catenin inhibition concomitant with IRF8 down-modulation, and CD8α+ DC overexpressing β-catenin produced enhanced IL-12 in response to microbial stimulation. During infection with T. gondii, a prototypic Type 1-inducing pathogen, mice overexpressing DC-specific β-catenin developed exacerbated Th1 responses culminating in early death. In addition, infection with VACV increased expansion and IFN-γ production by virus-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes.

Wnt/β-catenin signaling has a well-studied role in embryogenesis and tumorigenesis (10). It is now also clear that differentiation of T cells and NK cells requires LEF-1/TCF β-catenin cofactors. Furthermore, β-catenin regulates proliferation of pro-B cells (39). Using a β-catenin stabilization approach similar to that employed here, it has been found that this signaling molecule plays a fundamental role in regulating hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow (40). Furthermore, β-catenin has been recently shown to target Irf8 during hematopoiesis to alter granulocyte development (41). We now show that stabilization of β-catenin at the CD11c-expressing stage has unanticipated effects on generation of mature DC subsets whose differentiation depends upon IRF8.

Our data are notable because other recent studies have implicated β-catenin signaling in promoting tolerogenic DC phenotypes. For example, in contrast to activation by microbial stimulation, cluster disruption of bone marrow-derived DC activates β-catenin, endowing the cells with the ability to promote regulatory T cells that protect against experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE)(12). In the intestine, β-catenin expression by CD11c+ cells was shown to be required for regulatory T cell induction and production of anti-inflammatory factors, including retinoic acid-metabolizing enzymes, TGF-β and IL-10 (13). In this case, absence of β-catenin in DC increased sensitivity to dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-mediated colitis. Our data uncover an important new facet of β-catenin signaling because they reveal a role in promoting the differentiation of IRF8-dependent CD8α+ DC with enhanced proinflammatory activity.

IRF8 controls conventional DC formation by actively suppressing granulocyte differentiation while simultaneously promoting commitment to the DC lineage (42, 43). This is best illustrated by the observation that IRF8-deficient mice suffer from chronic myeloid leukemia-like syndrome with massive expansion of granulocytic cells (44). As such, IRF8 expression is enriched in CDP over common myeloid progenitors and is nearly absent in GMP(43), which is consistent with our finding that splenic DC precursors express β-catenin. Mice expressing constitutive β-catenin in the hematopoietic stem cell compartment, either through exon 3 deletion or transgenic expression of a phosphorylation resistant β-catenin, display a differentiation block at the granulocyte progenitor stage, which leads to lethality of the host (40, 45). It is tempting to speculate, therefore, that over-activation of β-catenin may lead to excessive IRF8 expression as early as the progenitor stage, resulting in suppression of granulocytic precursors and the subsequent direct promotion of DC development. This is supported by earlier findings that showed impaired granulocyte formation following β-catenin activation in HSC (41). Further, constitutive DC β-catenin signaling in our study appeared to push differentiation towards mature DC subsets by depleting early progenitor pre-cDC pools. Future studies should identify the activating Wnt ligand responsible for driving DC differentiation and suppressing granulocyte formation during hematopoiesis.

Several lines of evidence indicate a role for CD8α+ DC in antigen cross-presentation and activation of CD8+ T lymphocytes (5, 34). Toxoplasma is well known for its ability to elicit potent CD8+ T cell responses, and cross-presentation has previously been found to play a role in MHC class I presentation to CD8+ T cells during infection with this intracellular protozoan (46, 47). Therefore, it was initially surprising that there was no indication of abnormally strong CD8+ T cell responses in T. gondii-infected Ex3DC−/− mice that overexpress CD8α+ DC. However, the recent discovery that the parasite directly injects a subset of secretory proteins into the host cell cytoplasm (48), as well as evidence that the majority of T cell activation is stimulated by actively infected DC (49), argues that conventional presentation rather than cross-presentation may be the dominant mechanism for CD8+ T cell priming during T. gondii infection.

In contrast to normal CD8+ T cell responses following Toxoplasma infection in mice with DC-specific β-catenin activation, there was a clear increase in CD4+ T cell, and to a lesser extent NK cell, IFN-γ production in the mutant mice. This is of interest because CD4+ and CD11b+ DC, which are believed to be the most adept at activating CD4+ T cells (50), were unchanged or even reduced in Ex3DC−/− mice. Therefore, it is most likely that increased CD4+ T and NK cell IFN-γ resulted from increased splenic CD8α+ DC activity, and that failure to activate CD8+ T cells was due to the lack of cross-presentation. This is supported by the finding that virus-specific CD8 T cell responses were enhanced during VACV infection, which has been shown to require the cross-presentation pathway for CD8+ T cell activation.

Our findings uncover for the first time a role for stabilized β-catenin signaling in promoting DC subset differentiation and activity. Based upon previous findings, it has been suggested that exploiting strategies that activate β-catenin signaling in DC might be useful in the control of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases (12, 13). Our study throws a cautionary light on this approach, showing that constitutive β-catenin signaling promotes differentiation of IRF8-dependent DC resulting in increased proinflammatory responses during protozoan and viral infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (AI109061, EYD; AI083405, GSY; AI110613, BDR) and a scholarship from the Cornell Vertebrate Genomics group (SBC).

We thank M. Hossain for technical assistance.

Abbreviations used in this article

- BMDC

bone marrow-derived DC

- cDC

conventional DC

- CDP

common dendritic progenitor

- CMP

common myeloid progenitor

- DC

dendritic cell

- GMP

granulocyte-macrophage progenitor

- IRF

interferon regulatory factor

- pDC

plasmacytoid DC

- STAg

soluble tachyzoite antigen

References

- 1.Merad M, Sathe P, Helft J, Miller J, Mortha A. The dendritic cell lineage: ontogeny and function of dendritic cells and their subsets in the steady state and the inflamed setting. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:563–604. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belz GT, Nutt SL. Transcriptional programming of the dendritic cell network. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:101–113. doi: 10.1038/nri3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Satpathy AT, KC W, Albring JC, Edelson BT, Kretzer NM, Bhattacharya D, Murphy TL, Murphy KM. Zbtb46 expression distinguishes classical dendritic cells and their committed progenitors from other immune lineages. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2012;209:1135–1152. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson JT, Hu Y, Liu R, Masson F, D’Amico A, Carotta S, Xin A, Camilleri MJ, Mount AM, Kallies A, Wu L, Smyth GK, Nutt SL, Belz GT. Id2 expression delineates differential checkpoints in the genetic program of CD8α+ and CD103+ dendritic cell lineages. EMBO J. 2011;30:2690–2704. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hildner K, Edelson BT, Purtha WE, Diamond M, Matsushita H, Kohyama M, Calderon B, Schraml BU, Unanue ER, Diamond MS, Schreiber RD, Murphy TL, Murphy KM. Batf3 deficiency reveals a critical role for CD8alpha+ dendritic cells in cytotoxic T cell immunity. Science. 2008;322:1097–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1164206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Persson EK, Uronen-Hansson H, Semmrich M, Rivollier A, Hägerbrand K, Marsal J, Gudjonsson S, Håkansson U, Reizis B, Kotarsky K, Agace WW. IRF4 transcription-factor-dependent CD103(+)CD11b(+) dendritic cells drive mucosal T helper 17 cell differentiation. Immunity. 2013;38:958–969. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Staal FJT, Clevers HC. WNT signalling and haematopoiesis: a WNT-WNT situation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:21–30. doi: 10.1038/nri1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reya T, Duncan AW, Ailles L, Domen J, Scherer DC, Willert K, Hintz L, Nusse R, Weissman IL. A role for Wnt signalling in self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423:409–414. doi: 10.1038/nature01593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clevers H, Nusse R. Wnt/β-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012;149:1192–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klaus A, Birchmeier W. Wnt signalling and its impact on development and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:387–398. doi: 10.1038/nrc2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Staal FJT, Luis TC, Tiemessen MM. WNT signalling in the immune system: WNT is spreading its wings. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:581–593. doi: 10.1038/nri2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang A, Bloom O, Ono S, Cui W, Unternaehrer J, Jiang S, Whitney JA, Connolly J, Banchereau J, Mellman I. Disruption of E-cadherin-mediated adhesion induces a functionally distinct pathway of dendritic cell maturation. Immunity. 2007;27:610–624. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manicassamy S, Reizis B, Ravindran R, Nakaya H, Salazar-Gonzalez RM, Wang YC, Pulendran B. Activation of β-Catenin in Dendritic Cells Regulates Immunity Versus Tolerance in the Intestine. Science. 2010;329:849–853. doi: 10.1126/science.1188510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harada N, Tamai Y, Ishikawa T, Sauer B, Takaku K, Oshima M, Taketo MM. Intestinal polyposis in mice with a dominant stable mutation of the beta-catenin gene. EMBO J. 1999;18:5931–5942. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.5931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mashayekhi M, Sandau MM, Dunay IR, Frickel EM, Khan A, Goldszmid RS, Sher A, Ploegh HL, Murphy TL, Sibley LD, Murphy KM. CD8α(+) dendritic cells are the critical source of interleukin-12 that controls acute infection by Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites. Immunity. 2011;35:249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sigal LJ, Crotty S, Andino R, Rock KL. Cytotoxic T-cell immunity to virus-infected non-haematopoietic cells requires presentation of exogenous antigen. Nature. 1999;398:77–80. doi: 10.1038/18038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rudd BD, Venturi V, PDavenport M, Nikolich-Zugich J. Evolution of the antigen-specific CD8+ TCR repertoire across the life span: evidence for clonal homogenization of the old TCR repertoire. The Journal of Immunology. 2011;186:2056–2064. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider AG, Abi Abdallah DS, Butcher BA, Denkers EY. Toxoplasma gondii triggers phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of dendritic cell STAT1 while simultaneously blocking IFNγ-induced STAT1 transcriptional activity. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e60215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bedoui S, Prato S, Mintern J, Gebhardt T, Zhan Y, Lew AM, Heath WR, Villadangos JA, Segura E. Characterization of an immediate splenic precursor of CD8+ dendritic cells capable of inducing antiviral T cell responses. The Journal of Immunology. 2009;182:4200–4207. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denkers EY, Gazzinelli RT, Hieny S, Caspar P, Sher A. Bone marrow macrophages process exogenous Toxoplasma gondii polypeptides for recognition by parasite-specific cytolytic T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1993;150:517–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butcher BA, Kim L, Johnson PF, Denkers EY. Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites inhibit proinflammatory cytokine induction in infected macrophages by preventing nuclear translocation of the transcription factor NF-kappa B. J Immunol. 2001;167:2193–2201. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen SB, Maurer KJ, Egan CE, Oghumu S, Satoskar AR, Denkers EY. CXCR3-dependent CD4+ T cells are required to activate inflammatory monocytes for defense against intestinal infection. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003706. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu K, Victora GD, Schwickert TA, Guermonprez P, Meredith MM, Yao K, Chu FF, Randolph GJ, Rudensky AY, Nussenzweig M. In vivo analysis of dendritic cell development and homeostasis. Science. 2009;324:392–397. doi: 10.1126/science.1170540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edelson BT, KC W, Juang R, Kohyama M, Benoit LA, Klekotka PA, Moon C, Albring JC, Ise W, Michael DG, Bhattacharya D, Stappenbeck TS, Holtzman MJ, Sung S-SJ, Murphy TL, Hildner K, Murphy KM. Peripheral CD103+ dendritic cells form a unified subset developmentally related to CD8alpha+ conventional dendritic cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2010;207:823–836. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kashiwada M, Pham NLL, Pewe LL, Harty JT, Rothman PB. NFIL3/E4BP4 is a key transcription factor for CD8α+ dendritic cell development. Blood. 2011;117:6193–6197. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-295873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamura T, Tailor P, Yamaoka K, Kong HJ, Tsujimura H, O’Shea JJ, Singh H, Ozato K. IFN regulatory factor-4 and -8 govern dendritic cell subset development and their functional diversity. J Immunol. 2005;174:2573–2581. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hacker C, Kirsch RD, Ju XS, Hieronymus T, Gust TC, Kuhl C, Jorgas T, Kurz SM, Rose-John S, Yokota Y, Zenke M. Transcriptional profiling identifies Id2 function in dendritic cell development. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:380–386. doi: 10.1038/ni903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emami KH, Nguyen C, Ma H, Kim DH, Jeong KW, Eguchi M, Moon RT, Teo JL, Oh SW, Kim HY, Moon SH, Ha JR, Kahn M. A small molecule inhibitor of beta-catenin/CREB-binding protein transcription [corrected] Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12682–12687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404875101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jho EH, Zhang T, Domon C, Joo CK, Freund JN, Costantini F. Wnt/beta-catenin/Tcf signaling induces the transcription of Axin2, a negative regulator of the signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1172–1183. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1172-1183.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fuertes Marraco SA, Grosjean F, Duval A, Rosa M, Lavanchy C, Ashok D, Haller S, Otten LA, Steiner Q-G, Descombes P, Luber CA, Meissner F, Mann M, Szeles L, Reith W, Acha-Orbea H. Novel murine dendritic cell lines: a powerful auxiliary tool for dendritic cell research. Front Immunol. 2012;3:331. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raetz M, Kibardin A, Sturge CR, Pifer R, Li H, Burstein E, Ozato K, Larin S, Yarovinsky F. Cooperation of TLR12 and TLR11 in the IRF8-dependent IL-12 response to Toxoplasma gondii profilin. The Journal of Immunology. 2013;191:4818–4827. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu H, Zhu J, Smith S, Foldi J, Zhao B, Chung AY, Outtz H, Kitajewski J, Shi C, Weber S, Saftig P, Li Y, Ozato K, Blobel CP, Ivashkiv LB, Hu X. Notch-RBP-J signaling regulates the transcription factor IRF8 to promote inflammatory macrophage polarization. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:642–650. doi: 10.1038/ni.2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mordue DG, Monroy F, La Regina M, Dinarello CA, Sibley LD. Acute toxoplasmosis leads to lethal overproduction of Th1 cytokines. J Immunol. 2001;167:4574–4584. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haanden JM, Lehar SM, Bevan MJ. CD8(+) but not CD8(−) dendritic cells cross-prime cytotoxic T cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1685–1696. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson DC, Grotenbreg GM, Liu K, Zhao Y, Frickel EM, Gubbels MJ, Ploegh HL, Yap GS. Differential regulation of effector- and central-memory responses to Toxoplasma gondii Infection by IL-12 revealed by tracking of Tgd057-specific CD8+ T cells. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000815. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grover HS, Blanchard N, Gonzalez F, Chan S, Robey EA, Shastri N. The Toxoplasma gondii peptide AS15 elicits CD4 T cells that can control parasite burden. Infection and Immunity. 2012;80:3279–3288. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00425-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramirez MC, Sigal LJ. Macrophages and dendritic cells use the cytosolic pathway to rapidly cross-present antigen from live, vaccinia-infected cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:6733–6742. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schiavoni G, Mattei F, Sestili P, Borghi P, Venditti M, Morse HC, Belardelli F, Gabriele L. ICSBP is essential for the development of mouse type I interferon-producing cells and for the generation and activation of CD8alpha(+) dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1415–1425. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Timm A, Grosschedl R. Wnt signaling in lymphopoiesis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;290:225–252. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26363-2_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scheller M, Huelsken J, Rosenbauer F, Taketo MM, Birchmeier W, Tenen DG, Leutz A. Hematopoietic stem cell and multilineage defects generated by constitutive beta-catenin activation. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1037–1047. doi: 10.1038/ni1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheller M, Schönheit J, Zimmermann K, Leser U, Rosenbauer F, Leutz A. Cross talk between Wnt/β-catenin and Irf8 in leukemia progression and drug resistance. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2013;210:2239–2256. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tamura T, Nagamura-Inoue T, Shmeltzer Z, Kuwata T, Ozato K. ICSBP directs bipotential myeloid progenitor cells to differentiate into mature macrophages. Immunity. 2000;13:155–165. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Becker AM, Michael DG, Satpathy AT, Sciammas R, Singh H, Bhattacharya D. IRF-8 extinguishes neutrophil production and promotes dendritic cell lineage commitment in both myeloid and lymphoid mouse progenitors. Blood. 2012;119:2003–2012. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-364976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holtschke T, Löhler J, Kanno Y, Fehr T, Giese N, Rosenbauer F, Lou J, Knobeloch KP, Gabriele L, Waring JF, Bachmann MF, Zinkernagel RM, Morse HC, Ozato K, Horak I. Immunodeficiency and chronic myelogenous leukemia-like syndrome in mice with a targeted mutation of the ICSBP gene. Cell. 1996;87:307–317. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81348-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kirstetter P, Anderson K, Porse BT, Jacobsen SEW, Nerlov C. Activation of the canonical Wnt pathway leads to loss of hematopoietic stem cell repopulation and multilineage differentiation block. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1048–1056. doi: 10.1038/ni1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldszmid RS, Coppens I, Lev A, Caspar P, Mellman I, Sher A. Host ER-parasitophorous vacuole interaction provides a route of entry for antigen cross-presentation in Toxoplasma gondii-infected dendritic cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2009;206:399–410. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.John B, Harris TH, Tait ED, Wilson EH, Gregg B, Ng LG, Mrass P, Roos DS, Dzierszinski F, Weninger W, Hunter CA. Dynamic Imaging of CD8(+) T cells and dendritic cells during infection with Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000505. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Melo MB, Jensen KDC, Saeij JPJ. Toxoplasma gondii effectors are master regulators of the inflammatory response. Trends Parasitol. 2011;27:487–495. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dupont CD, Christian DA, Selleck EM, Pepper M, Leney-Greene M, Harms Pritchard G, Koshy AA, Wagage S, Reuter MA, Sibley LD, Betts MR, Hunter CA. Parasite Fate and Involvement of Infected Cells in the Induction of CD4+ and CD8+ T Cell Responses to Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004047. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vander Lugt B, Khan AA, Hackney JA, Agrawal S, Lesch J, Zhou M, Lee WP, Park S, Xu M, DeVoss J, Spooner CJ, Chalouni C, Delamarre L, Mellman I, Singh H. Transcriptional programming of dendritic cells for enhanced MHC class II antigen presentation. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:161–167. doi: 10.1038/ni.2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.