Abstract

This study used eye-tracking and grammaticality judgment measures to examine how second language (L2) learners process syntactic violations in English. Participants were native Arabic and native Mandarin Chinese speakers studying English as an L2, and monolingual English speaking controls. The violations involved incorrect word order and differed in two ways predicted to be important by the Unified Competition Model (UCM; MacWhinney, 2005). First, one violation had more and stronger cues to ungrammaticality than the other. Second, the grammaticality of these word orders varied in Arabic and Mandarin Chinese. Sensitivity to violations was relatively quick overall, across all groups. Sensitivity also was related to the number and strength of cues to ungrammaticality regardless of native language, which is consistent with the general principles of the UCM. However, there was little evidence of cross-language transfer effects in either eye movements or grammaticality judgments.

Keywords: cue strength, cross-language transfer, eye-tracking, Unified Competition Model, second language learning

Syntax varies widely across languages, differing at both the coarse grain of phrase structure and the finer grain of morphosyntax. These variations are thought to influence second language (L2) processing and learning in different ways (e.g., Clahsen & Felser, 2006a, 2006b; MacWhinney, 2005). Many previous studies have examined L2 morphosyntactic processing (e.g., Sabourin et al., 2006; Sabourin & Stowe, 2008; Tokowicz & MacWhinney, 2005; Tokowicz & Warren, 2010), but almost all work examining purely syntactic structures has focused on relative clause attachment preferences (Dussias, 2003; Dussias & Sagarra, 2007; Frenck-Mestre & Pynte, 1997; Witzel et al., 2009). Expanding this existing research to other kinds of syntactic processing will be vital for a fuller understanding of L2 syntactic processing, especially given the fact that relative clause attachment preferences are often relatively weak and may be influenced by factors such as an individual’s working memory capacity and the depth to which they are processing what they are reading (Swets, Desmet, Hambrick, & Ferreira, 2007; Swets, Desmet, Clifton, & Ferreira, 2008).

The present eye-tracking study builds on previous research regarding how L2 learners process (morpho)syntax, and extends that research to purely syntactic constructions by investigating factors that influence how sensitive L2 learners are to word order violations in their L2. We tested native Arabic, native Mandarin Chinese, and native English speakers on sentences with and without word order violations. To test the predictions of the Unified Competition Model (UCM; MacWhinney, 2005; see also the Competition Model of Bates & MacWhinney, 1987), these violations differed in how many cues to ungrammaticality they included, and in their relationship to the word order of the L2 speakers’ native languages.

According to some models of language processing, cues form the basis of language comprehension. In particular, the UCM is a data-driven connectionist model that describes how cues help the language user determine how to interpret a particular structure or link it into a larger linguistic unit. These cues vary in strength based on their availability (how often they are present) and reliability (how often they lead to a successful interpretation). The product of cue availability and reliability is cue validity; this serves as the primary indicator of cue strength, which is instantiated in the model as the weights that speakers assign to each cue during processing.

Critically, the cues that adult L2 learners initially use to process their L2 will have been derived from L1 input, and therefore will be more appropriate to L1 than L2 processing. As a result, L2 processing success depends in part on whether L1 and L2 are similar enough that the same cues apply to both. Structures for which cues can transfer directly from L1 to L2 (henceforth, “similar” constructions) will benefit from positive transfer and not suffer from any competition between L1 and L2. By contrast, structures for which cues are different in L1 and L2 (henceforth, “different” constructions) will not benefit from positive transfer and will instead suffer from competition. Finally, structures for which cues are unique to the L2 (henceforth, “unique” constructions) do not benefit from positive transfer but also do not suffer from competition. The learning of unique structures will depend on L2 cue strength.

The current study tested the influence of both cue strength and transfer on sensitivity to word-order violations in the L2. Specifically, we had native Arabic and native Mandarin learners of English read and judge the grammaticality of sentences with one of two types of violations while we tracked their eye movements. In the first kind of violation, an article followed a noun (we will refer to this as the ungrammatical noun-article condition). In the second kind of violation, an adjective appeared after a noun (we call this the ungrammatical noun-adjective condition).

| EXAMPLES: | Grammatical: | She pulled the short skirt up over her leggings. |

| Ungram. Noun-Art.: | She pulled skirt the short up over her leggings. | |

| Ungram. Noun-Adj.: | She pulled the skirt short up over her leggings. |

Note that because the manipulation affected only word order, the target region consisting of the article, adjective, and noun contained exactly the same words across conditions. The cues to ungrammaticality, however, differ across the two grammaticality-violation conditions, with more and stronger cues to ungrammaticality in the noun-article condition than in the noun-adjective condition. The noun-article condition has up to three cues to ungrammaticality, whereas the noun-adjective condition has only one. The single cue in the noun-adjective condition is the encountering of a noun-adjective bigram in this context.1 In the noun-article condition, two reliable cues to ungrammaticality are: encountering a noun-article bigram in this context and encountering the following adjective. In addition, in some of the items, the presence of a bare noun in the direct object position could have been a cue to a violation.

To provide a rough estimate of the relative strengths of these unusual bigrams as cues to ungrammaticality, we conducted an analysis of the 305,789 noun-initial bigrams that appear in the one million most frequent English bigrams from the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA; Davies, 2011) and found that adjectives appear more often after nouns (0.89%) than the article “the” appears after nouns (0.58%), x2 (1, 4495) = 209.75, p < .001. Although these frequencies do not take context into account, they suggest that noun-”the” bigrams are less frequent than noun-adjective bigrams in grammatical sentences and therefore are likely to be stronger cues to ungrammaticality. The presence of an adjective following the noun-article bigram in the noun-article condition is an additional cue to ungrammaticality. A possible additional cue to a violation in the noun-article condition in some items is the fact that the inversion of the usual order of the noun and article left a bare noun as the direct object of the sentence. For example,“She pulled skirt…” sounds unnatural, even though it could be grammatically continued with “after skirt out of her drawer.”. Because the acceptability of the bare noun varied across items, we ran a norming questionnaire to determine the strength of this cue across the whole set of items. Participants rated the naturalness of a fragment of each item up to and including the first word in the target region.2 Fragments ending with bare nouns were rated more unnatural than fragments ending with “the”, suggesting that the bare noun may often have been a cue to a violation in the noun-article condition. To summarize, there are more cues to ungrammaticality in the noun-article condition than in the noun-adjective condition, and some of these cues are available earlier in the text in the noun-article condition than in the noun-adjective condition.

The UCM also predicts that transfer will affect processing. In both Arabic and English the definite article (“al” in Arabic) comes before the noun, so for Arabic-English bilinguals, the similarity of the violation in the noun-article condition across languages should make ungrammaticality easier to detect. Mandarin, on the other hand, is considered an article-less language (Chang, 1987; Li & Thompson, 1997), and native Mandarin speakers have difficulty using articles correctly in English (Robertson, 2000; Zdorenko & Paradis, 2008). We therefore considered the noun-article order a violation of a construction unique to the L2 for Mandarin-English bilinguals.3

With respect to the ungrammatical noun-adjective condition, adjective placement is different in Arabic and English. Arabic places adjectives after nouns, so using Arabic cues to process the English input should make Arabic-English bilinguals poorer at detecting this violation. On the other hand, adjective placement is similar in Mandarin and English; in both languages, adjectives come before nouns, so Mandarin-English bilinguals should have positive transfer for this violation. Thus, across the experiment, the native Arabic speakers were presented with violations of both similar and different constructions and the native Mandarin speakers with violations of similar and unique constructions.

In the current experiment, we tracked participants’ eyes as they read sentences in preparation for making a grammaticality judgment. This concurrent meta-task likely influenced reading strategies and eye-movement patterns, which raises the question of whether our data reflects natural reading (Roberts, 2012). Leaving aside questions about whether reading is ever natural during a sentence-reading experiment, it is likely that participants read our sentences more carefully than they would have if they had not been engaged in a meta-task. However, this is not a drawback for a few reasons. First, forcing careful reading is advantageous in this experiment because we are interested in whether or not participants show violation-associated disruption. Given that shallow reading is likely more common in L2 than in L1 (Clahsen & Felser, 2006), and shallow reading can cause even native speakers to miss severe anomalies (e.g. Bohan & Sanford, 2008), pushing our participants to read carefully minimizes the likelihood than any lack of sensitivity to violations in our data will be due to shallow reading rather than a true lack of sensitivity. Second, the first-pass eye-movement record should still be a useful record of on-line sentence processing, because reading a sentence is the fastest and easiest way to decide whether it is grammatical or not. Third, many other studies that have provided insight into questions of L1 transfer have used reading and delayed grammaticality judgment (e.g. Ellis, 1991; McDonald, 2006; Tokowicz & MacWhinney, 2005; Tokowicz & Warren, 2010), so any effects found here will be comparable to those in previous studies. Longer fixation times and more regressions in first-pass reading measures for ungrammatical sentences compared to grammatical sentences will be taken to indicate earlier or relatively more on-line sensitivity to a grammatical violation. Longer total reading times or more accurate grammaticality judgments will be taken to reflect later, more considered sensitivity.

As discussed previously, the current study tests two of the UCM’s hypothesized mechanisms influencing L2 processing: transfer from the L1 to the L2 (as detailed above, with similar, different, or unique constructions) and cue strength modulations (such that the noun-article construction had more and stronger cues to ungrammaticality than the noun-adjective construction). However, it is unclear how (or if) these mechanisms will predict stronger sensitivity to one structure over another. If the relative influence of transfer were greater than that of cue strength, we would expect native English speakers to be sensitive to both types of violations, native Mandarin speakers to be more sensitive to the noun-adjective violation, and native Arabic speakers to be more sensitive to the noun-article condition. Conversely, if the relative influence of cue strength is greater than the influence of transfer, all participants should be more sensitive to the ungrammatical noun-article condition than the ungrammatical noun-adjective condition because the cues to ungrammaticality are stronger and more numerous in the noun-article condition.

Method

Participants

Analyses were based on 20 speakers from each native language group. A total of 29 native Arabic speakers, 31 native Mandarin speakers, and 29 native English speakers participated in this study. Participants were randomly assigned to one of four stimulus lists, which did not yield an equal number of participants per list. Therefore, to perfectly match the counterbalancing of items, it was necessary to remove data from nine native English participants, nine native Arabic participants, and eleven native Mandarin participants were to ensure an equal number (5) per list version and per group. The selection of the particular participants to remove was completed with the goal of choosing groups that were matched as closely as possible in proficiency, operationalized as their self-rated proficiency and performance on grammaticality judgments.

Non-native English speakers were recruited from the English Language Institute (ELI) and the Department of Linguistics at the University of Pittsburgh, using in-class announcements, advertisements, and recruitment posters. Non-native speaking participants received $20 as compensation for their participation in the study. The native Arabic speakers were current students at the ELI, ranging from levels 4 to 5 (out of 5 levels), which represent intermediate to advanced level performance in four classes: reading, writing, listening, and speaking. This corresponds to a Michigan Test of Language Proficiency (MTELP) score of 55 or above (out of 100). Of the twenty native Mandarin speakers who participated, half were current students at the ELI and half were students in the Department of Linguistics at the University of Pittsburgh. These Linguistics students were taking English language classes similar to the ELI courses in preparation to become undergraduates at the University of Pittsburgh. The native English speakers were recruited from the University of Pittsburgh’s Psychology subject pool, and were given credit toward a course requirement for their participation in the study.

All participants completed a questionnaire detailing their language experiences (Tokowicz, Michael, & Kroll, 2004). These measures included reading proficiency, writing proficiency, conversational fluency, and spoken language comprehension. Although the three language groups had very high self-rated ability in all measures in L1, they rated their ability considerably lower in the L2, demonstrating a clear dominant language for the three language groups. The native Arabic and native Mandarin speakers did not differ significantly in self-rated English proficiency, t (38) = .62, p = .54 (see Table 1). As another way of measuring proficiency, we also examined performance on the grammatical judgment task; native Arabic and native Mandarin speakers also did not differ significantly in terms of accuracy, t (38) = 1.46, p = .15.

Table 1. Means for self-rated proficiency for participants in the three language groups.

| Measure | Native English speakers (M = 13, F = 7) | Native Arabic speakersa (M = 15, F = 3) | Native Mandarin speakers (M = 6, F = 14) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 18.79 (1.77) | 25.25 (3.40) | 25.90 (5.52) |

| Time in USA (months) | 223.80 (1.95) | 8.40 (5.73) | 7.40 (7.67) |

| Self-rated proficiencyb | |||

| L1 Reading | 9.48 (0.80) | 9.65 (0.67) | 9.60 (0.60) |

| L1 Writing | 9.39 (0.93) | 9.00 (1.12) | 8.90 (1.12) |

| L1 Speaking | 9.67 (0.69) | 9.75 (0.55) | 9.90 (0.45) |

| L1 Listening | 9.79 (0.48) | 9.80 (0.41) | 9.60 (0.68) |

| L2c Reading | 4.79 (2.48)* | 6.15 (1.31) | 5.62 (1.71) |

| L2 Writing | 3.87 (2.26)* | 5.65 (1.18) | 5.00 (1.81) |

| L2 Speaking | 3.16 (2.10)* | 6.20 (1.79) | 5.95 (1.61) |

| L2 Listening | 3.65 (2.14)* | 6.55 (1.50) | 5.50 (1.50) |

Note: Standard deviations are shown in parentheses. M = male; F = female; L1 = first language; L2 = second language.

Two native Arabic participants did not indicate their gender.

Self-rated proficiency is on a 1- to 10-point Likert-type scale with 10 indicating the highest level of ability and 1 indicating the lowest level of ability.

L2s for native English speakers included Spanish (n = 4), French (n = 4), German (n = 1), and none (11).

Native English speakers had significantly lower L2 self-ratings than did L2 speakers (p < .05).

Design and Stimuli

We used a three native language group (English, Arabic, Mandarin) × 3 grammaticality (grammatical, noun-adjective, noun-article) within-participants design. The stimuli consisted of 56 experimental English items and four practice items. The stimuli were counterbalanced across four presentation lists, such that each participant saw each item only once, in the grammatical condition, the noun-adjective condition, or the noun-article condition. Within each list, participants saw equal numbers of grammatical and ungrammatical experimental stimuli (28 grammatical sentences, 14 ungrammatical sentences with a noun-adjective violation, and 14 ungrammatical sentences with a noun-article violation). Each list also contained the same fifty-six filler sentences, which consisted of 28 grammatical and 28 ungrammatical sentences involving morphosyntactic violations. These sentences were taken from Tokowicz and Warren (2010); one quarter included violations of subject-verb person agreement and one quarter included violations of verb aspect licensing. Thus, 50% of the trials were grammatical and 50% of the trials were ungrammatical. Participants were randomly assigned to presentation lists.

The target region in each sentence was the group of three words that included the syntactic violations. See examples below; the target region is underlined.

| EXAMPLES: | Grammatical: | She demanded the pink cake for her birthday. |

| Ungram. Noun-Art.: | She demanded cake the pink for her birthday. | |

| Ungram. Noun-Adj.: | She demanded the cake pink for her birthday. |

Experimental sentences were divided into five interest areas. The first region included the subject, the second region included the verb, the third region was the target region with the article, noun, and adjective, the fourth region included the two to three words after the target region, and the last region was the remainder of the sentence. For example, the sentence “She demanded the pink cake for her birthday” was divided into the following areas: She/demanded/the pink cake/for her/birthday.

The words were crosschecked with a list of words with which students in the ELI at the University of Pittsburgh should be familiar. This list was composed of the General Service List (Bauman, 2010; West, 1953) and all vocabulary from the first four chapters of the ELI vocabulary textbooks (Rogerson, Davis, Hershelman, & Jasnow, 1992; Rogerson, Esarey, Hershelman, Jasnow, Moltz, Schmandt, & Smith, 1992; Rogerson, Hershelman, Jasnow, & Moltz, 1992).78% of the words in the stimuli were present in this list. Additionally, we conducted vocabulary tests after the eye-tracking task to evaluate the L2 speakers’ knowledge of the vocabulary used in the sentences. On average, native Arabic speakers did not know 9% of the vocabulary used, and native Mandarin speakers did not know 11%. There were no significant differences in vocabulary test performance between L2 speaker groups, t< 1.

Procedure

Participants read the sentences while their eye movements were tracked. They were told that after each sentence, they would see a question asking them if the sentence they saw was grammatical, and they were to respond yes or no by pressing a button on a game controller. The apparatus was an EyeLink 1000 tower-mounted eye-tracker (SR Research Ltd., Toronto, Ontario, Canada). The average eye-gaze position accuracy ranged from 0.05 to 0.25 visual degrees. Data were recorded monocularly from the pupil of the right eye at a sampling rate of 1000Hz. Chin and forehead rests were used to minimize head movement. The screen resolution was set at 1024 × 768 pixels, and the stimuli were presented in black Times New Roman 20-point font on a white background. Sentences were left justified. Before beginning the experiment, the eye-tracker was calibrated to each participant using a nine-point calibration grid, followed by a validation check. Before each sentence, a one-point calibration check on the left side of the screen was conducted to ensure that participants consistently began reading the sentence at the leftmost point. The eye-tracking task took 30 minutes to complete on average, and participants then completed a vocabulary post-test and the language history questionnaire.

Results

Five eye-movement measures were computed: first fixation duration, or the duration of the first fixation on a region during first pass reading; first pass reading times, the sum of the duration of all fixations on a region from when it is first fixated during first pass reading until the eyes leave the region; first pass regressions out, or the proportion of trials on which there was a regression from a region during first pass reading; go-past time, or the sum of all fixations from first entering a region during first pass reading until the eyes move past the region to the right; and total time, or the sum of all fixations on a region. Each measure was analysed using a 3 native language (English, Arabic, Mandarin) by 3 grammaticality condition (grammatical, ungrammatical noun-adjective, ungrammatical noun-article) repeated measures ANOVA. Analyses were conducted using both participants (F1) and items (F2) as random factors. For analyses violating the assumption of sphericity, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied. Following convention (Picton et al., 2000), we report uncorrected degrees of freedom, the corrected p-value, and corrected mean square error values. For all post-hoc analyses performed, the Bonferroni correction was applied. For these, there were always three comparisons, which necessitated a corrected p-value of .0167 (rounded to .02) for significance and .033 (rounded to .03) for marginal significance. We report statistical effects with marginal means to describe the direction and raw magnitude of the effect in the text, and give cell means and statistics in tables. Non-significant effects are not reported in the text, but are reported in the tables.

Eye-tracking data were cleaned such that single fixations shorter than 40 ms that fell within 0.5 characters of another fixation were combined into the longer fixation. Remaining fixations shorter than 80 ms or longer than 1000 ms were removed from the data, following common practice in reading eye-tracking studies (Rayner, 1998). Three characters spanned 1.15 degrees of visual angle. The target region was fixated during first pass reading on the majority of trials for all groups, however there were differences in fixation rates among the groups (native Arabic 95%; native Mandarin 79%; native English 97%). Trials on which the target region was not fixated were removed from the analyses.

Target Region

Table 2 reports reading time measures by native language group and grammaticality condition for the target region, and Table 3 provides the statistical tests for all analyses on the target region. Overall, native Arabic speakers tended to have longer reading times than the other two participant groups, and native Mandarin speakers had longer first pass and total reading times than native English speakers.

Table 2. Mean reading time measures in the target region by native language group.

| Measure | English

|

Arabic

|

Mandarin

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram. | Noun–adj. | Noun–art. | Mean | Gram. | Noun–adj. | Noun–art. | Mean | Gram. | Noun–adj. | Noun–art. | Mean | |

| First-fixation duration (ms) | 218 | 219 | 242 | 226 | 269 | 261 | 310 | 280 | 230 | 225 | 250 | 235 |

| First-pass reading time (ms) | 544 | 681 | 757 | 661 | 1399 | 1508 | 1342 | 1416 | 1015 | 985 | 1038 | 1013 |

| Regressions out (proportion exiting the region) | .16 | .17 | .36 | .23 | .25 | .26 | .38 | .30 | .13 | .22 | .30 | .22 |

| Go-past time (ms) | 680 | 818 | 1127 | 875 | 1857 | 2159 | 2391 | 2135 | 557 | 594 | 687 | 613 |

| Total time (ms) | 917 | 1179 | 1282 | 1126 | 3490 | 4096 | 3777 | 3789 | 2314 | 2937 | 3182 | 2811 |

Note: Gram. = grammatical; adj. = adjective; art. = article.

Table 3. Statistical tests on reading time measures in the target region.

| Effect | First-fixation duration

|

FP reading times

|

FP regressions out

|

Go-past time

|

Total time

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects | Items | Subjects | Items | Subjects | Items | Subjects | Items | Subjects | Items | |

| Native language group | 15.05 (50344)** | 45.78 (118638)** | 30.62 (8580500)** | 169.72 (26121239)** | 1.32 (0.02) | 1.59 (0.08) | 27.44 (39764768)** | 331.99 (112827189)** | 35.45 (108769970)** | 355.66 (322276381)** |

| English vs. Arabic | 4.61** | 9.38** | 7.47** | 17.49** | 2.21* | 2.86** | 5.52** | 18.05** | 8.47** | 26.82** |

| English vs. Mandarin | 1.13 | 1.46 | 5.65** | 11.49** | <1 | 1.06 | 1.60 | 3.51** | 7.68** | 18.55** |

| Arabic vs. Mandarin | 3.71** | 6.49** | 3.33** | 8.16** | 2.27* | 3.59** | 5.87** | 19.22** | 2.75** | 8.66** |

| Gramm. condition | 19.20 (18650)** | 26.26 (68054)** | 2.72 (89309) | 3.37 (518186)* | 55.35 (0.87)** | 23.41 (1.21)** | 25.49 (2065794)** | 20.77 (7058362)** | 16.34 (5040208)** | 17.65 (15989036)** |

| Noun–adjective vs. grammatical | <1 | <1 | 2.83** | 1.92 | 1.55 | 1.58 | 3.96** | 2.21* | 4.54** | 3.49** |

| Noun–article vs. grammatical | 5.04** | 5.12** | 1.71 | 1.74 | 7.48** | 6.82** | 5.47** | 4.78** | 5.54** | 3.47** |

| Noun–adjective vs. noun–article | 5.19** | 5.43** | <1 | <1 | 5.29** | 4.43** | 4.22** | 1.91 | <1 | <1 |

| Native Language × Gramm. Condition | < 1 | < 1 | 4.58 (150336)* | 2.54 (391048)* | 1.32 | 1.59 | 3.10(251135)* | 1.90(644965) | 2.45 (755780)* | 2.56 (2321768)* |

| Native English | ||||||||||

| Noun–adjective vs. grammatical | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 5.11** | 4.14** | 4.04** | 3.37** | 4.27** | 5.19** |

| Noun–article vs. grammatical | 2.52* | 3.53** | 6.17** | 5.22** | 5.92** | 5.28** | 7.48** | 8.92** | 4.28** | 6.05** |

| Noun–adjective vs. noun–article | 2.29* | 2.79** | 5.07** | 4.72** | 1.51 | 1.49 | 5.68** | 5.59** | 2.06 | <1 |

| Native Arabic | ||||||||||

| Noun–adjective vs. grammatical | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 2.14, p = .05 | 1.45 | 3.17** | 2.19* | 2.25* | 2.81** |

| Noun–article vs. grammatical | 3.56** | 4.06** | 3.97** | 3.34** | <1 | <1 | 3.14** | 4.78** | 1.60 | 1.47 |

| Noun–adjective vs. noun–article | 4.59** | 4.62** | 3.10** | 2.71** | 1.68 | 1.62 | 1.84, p = .08 | <1 | 1.12 | 1.57 |

| Native Mandarin | ||||||||||

| Noun–adjective vs. grammatical | <1 | <1 | 1.83, p = .08 | 1.89, p = .06 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | 1.14 | 3.55** | 3.54** |

| Noun–article vs. grammatical | 2.61* | 2.41* | 3.51** | 3.54** | < 1 | 1.17 | 1.78, p = .09 | 2.54* | 5.20** | 5.00** |

| Noun–adjective vs. noun–article | 2.24* | 2.84** | 1.62 | 1.00 | 1.02 | < 1 | 1.61 | 1.57 | 1.76, p = .10 | 1.03 |

Note: Values represent F-test statistics for main effects and interactions with mean square errors in parentheses, and t-test statistics for pair-wise comparisons. FP = first-pass; gramm. = grammatical.

p < .05.

p < .01.

First fixation durations

Grammaticality condition reliably influenced first fixation durations, but did not interact with language group. First fixation durations were longer for the noun-article condition (267 ms) than the noun-adjective (235 ms) and grammatical conditions (239 ms), which did not differ from each other.

Regressions out

The same pattern was evident in first pass regressions out, which were reliably influenced by grammaticality condition, such that there were more regressions out of the noun-article condition (0.35) than the grammatical (0.18) or noun-adjective conditions (0.22). This was not qualified by native language group.

First pass reading times

Grammaticality condition and native language group interacted in first pass reading times. Native English speakers looked longer at the noun-adjective (681 ms) and noun-article (757 ms) ungrammatical conditions than the grammatical condition (544 ms). By contrast, native Arabic and Mandarin speakers showed no effect of condition in this measure.

Go-past times

Grammaticality condition and native language group interacted in the analysis of go-past times in the target region, although this was not significant in the analysis by items. Post-hoc analyses demonstrated that native English speakers had shortest go-past times in the grammatical condition (680 ms), reliably longer times in the noun-adjective condition (818 ms), and reliably longest times in the noun-article condition (1127 ms). Native Arabic speakers had reliably shorter go-past times in the grammatical condition (1857 ms) than in both the noun-adjective (2159 ms), and the noun-article condition (2391 ms), with no difference between the two ungrammatical conditions. Native Mandarin speakers showed no significant differences between conditions except they had shorter times in the grammatical (660 ms) than the noun-article condition (866 ms) by items.

Total time

Across language groups, total times were longer in both the noun-adjective (2737 ms) and noun-article (2747 ms) ungrammatical conditions than the grammatical condition (2240 ms). Furthermore, native language group and grammaticality condition interacted. For native Mandarin and English speakers, total times were longer in both the noun-adjective (Mandarin: 2937 ms; English: 1179 ms) and noun-article (Mandarin: 3182 ms; English: 1282 ms) ungrammatical conditions than in the grammatical condition (Mandarin: 2314 ms; English: 917 ms). Native Arabic speakers did not show significant differences between grammaticality conditions, although they did show longer mean total times on the noun-adjective condition (4096 ms) than the grammatical (3490 ms) and noun-article (3777 ms) conditions generally, and the post-hoc contrast between the grammatical and noun-adjective condition was marginally reliable (and would be considered fully reliable if the Bonferroni correction were not applied to our contrasts).

Post-target Region

Because: (1) grammaticality effects are sometimes delayed in L2 speakers (e.g., Tokowicz & Warren, 2010), and (2) eye-movement effects sometimes spill over or appear on the word following a violation (Rayner, 1998), we also analysed eye-movement measures in the post-target region. Again, for all post-hoc tests, the critical Bonferroni-corrected p is rounded to .02 for three comparisons, and .03 for marginal comparisons. Table 4 reports reading time measures by language group and condition for the post-target region. Table 5 provides the statistical tests for all analyses on the post-target region. Like in the target region, native Arabic speakers tended to have the longest reading times, native Mandarin speakers tended to have intermediate reading times, and native English speakers tended to have the shortest reading times. In the post-target region, however, native Mandarin speakers had reliably more regressions out (.43) than the native Arabic (.27) or native English (.18) speakers. This finding could be related to the fact that Mandarin speakers were more likely to skip the target region on the first pass than the other groups, and thus probably more likely to go back and re-read the target region.

Table 4. Mean reading time measures in the posttarget region by native language group.

| Measure | English

|

Arabic

|

Mandarin

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram. | Noun–Adj. | Noun–Art. | Mean | Gram. | Noun–Adj. | Noun–Art. | Mean | Gram. | Noun–Adj. | Noun–Art. | Mean | |

| First-fixation duration (ms) | 238 | 248 | 249 | 245 | 287 | 291 | 281 | 290 | 256 | 270 | 264 | 271 |

| First-pass reading time (ms) | 381 | 391 | 328 | 366 | 653 | 612 | 605 | 633 | 490 | 505 | 490 | 507 |

| Regressions out (proportion exiting the region) | .14 | .22 | .19 | .18 | .20 | .36 | .26 | 27 | .28 | .60 | .44 | .44 |

| Go-past time (ms) | 613 | 678 | 574 | 621 | 1057 | 1479 | 1152 | 1256 | 795 | 1206 | 1107 | 1092 |

| Total time (ms) | 604 | 593 | 461 | 553 | 1653 | 1622 | 1248 | 1539 | 1201 | 1270 | 1060 | 1205 |

Note: Gram. = grammatical; adj. = adjective; art. = article.

Table 5. Statistical tests on reading time measures in the posttarget region.

| Effect | First-fixation duration

|

FP reading times

|

FP regressions out

|

Go-past time

|

Total time

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects | Items | Subjects | Items | Subjects | Items | Subjects | Items | Subjects | Items | |

| Native language group | 4.74 (25558)* | 26.39 (914380)** | 15.29 (989459)** | 64.87 (2680416)** | 20.35 (0.98)** | 46.66 (2.77)** | 19.34 (5787002)** | 54.48 (16539720) ** | 25.01 (14105830)** | 139.40 (44174688)** |

| English vs. Arabic | 3.99** | 6.81** | 5.82** | 10.95** | 3.17** | 4.53** | 5.53** | 9.88** | 7.86** | 14.86** |

| English vs. Mandarin | 1.65 | 2.44* | 3.78** | 6.78** | 5.99** | 8.49** | 4.96** | 8.44** | 6.48** | 16.22** |

| Arabic vs. Mandarin | 2.61* | 5.16** | 2.67* | 5.27** | 3.23** | 5.15** | 1.97, p = .06 | 3.07** | 2.65* | 5.13** |

| Gramm. condition | 1.02(1319) | 1.08 (44447) | 2.90(19733), p = .06 | 1.59(5515.48) | 15.90 (0.46)** | 18.22 (1.08)** | 2.83 (299075)* | 2.24 (679931), p = .06 | 10.14 (1094155)** | 10.28 (32567167)** |

| Noun–adjective vs. grammatical | 1.46 | 1.81 | <1 | <1 | 5.73** | 5.86** | 4.44** | 3.75** | <1 | <1 |

| Noun–article vs. grammatical | <1 | 1.32 | 2.19* | 1.38 | 3.55** | 3.67** | 2.39* | 1.79 | 3.98** | 3.51** |

| Noun–adjective vs. noun–article | <1 | <1 | 1.94, p = .06 | <1 | 2.05* | 1.87, p = .06 | 2.78** | 2.11* | 4.10** | 3.21** |

| Native Language × Gramm. Condition | <1 | <1 | 1.33 (9059) | <1 | 1.91 (0.06) | 2.70 (0.16)* | 2.83 (299075)* | 2.24 (679931), p =.06 | 1.27 (137245) | 1.89 (598539) |

| Native English | ||||||||||

| Noun–adjective vs. grammatical | <1 | 1.02 | <1 | <1 | 2.25* | 2.20* | 1.04 | 1.25 | <1 | <1 |

| Noun–article vs. grammatical | <1 | 1.07 | 2.64* | 1.47 | 1.35 | 1.14 | <1 | <1 | 3.32** | 3.63** |

| Noun–adjective vs. noun–article | <1 | <1 | 2.50* | 1.60 | <1 | <1 | 2.35* | 1.37 | 2.58* | 2.94** |

| Native Arabic | ||||||||||

| Noun–adjective vs. grammatical | <1 | <1 | 1.58 | 1.09 | 5.35** | 4.01** | 2.85* | 1.83 | <1 | <1 |

| Noun–article vs. grammatical | <1 | <1 | 1.29 | 1.31 | 2.33* | 1.90, p =.06 | 1.02 | <1 | 2.78* | 3.60** |

| Noun–adjective vs. noun–article | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 2.23* | 1.49 | 2.13, p =.05 | 1.78 | 2.49* | 2.31* |

| Native Mandarin | ||||||||||

| Noun–adjective vs. grammatical | 1.57 | 1.49 | <1 | <1 | 3.80** | 4.76** | 3.73** | 4.87** | <1 | <1 |

| Noun–article vs. grammatical | <1 | 1.00 | <1 | <1 | 2.61* | 3.39** | 3.17* | 3.40** | 1.91 | 1.61 |

| Noun–adjective vs. noun–article | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 1.18 | 1.31 | <1 | <1 | 3.08** | 2.69** |

Note: Values represent F-test statistics for main effects and interactions with mean square errors in parentheses, and t-test statistics for pair-wise comparisons, FP = first-pass; gramm. = grammatical.

p <.05.

p <.01.

First fixation durations and first pass reading times

Grammaticality condition and native language group did not interact for first fixation durations or first pass reading times. There was no main effect of grammaticality for first fixation durations, but there was a marginal effect for first pass reading times only in the analysis by items.

Regressions out

There was a significant effect of grammaticality in regressions out of the post-target region. Post-hoc tests showed that both the noun-adjective (.38) and noun-article (.30) ungrammatical conditions had significantly more regressions out than the grammatical condition (.20). There was a marginally significant difference between the two ungrammatical conditions, such that the noun-adjective condition had more regressions out than the noun-article condition. There was no interaction between grammaticality condition and native language group in the analysis by subjects, although this effect was significant in the analysis by items.

Go-past times

Grammaticality condition and native language group interacted in go-past times in the post-target region, although only marginally so in the analysis by items. Native English speakers showed a difference only between the two ungrammatical conditions, such that the noun-adjective condition (678 ms) had longer go-past times than the noun-article condition (574 ms) in the analysis by subjects. There were no differences between these two ungrammatical conditions and the grammatical condition (613 ms). Native Arabic speakers had longer go-past times in the noun-adjective (1479 ms) than the grammatical (1057 ms) condition only in the analysis by subjects. They also had longer go-past times in the noun-article (1153 ms) than the noun-adjective condition, although this contrast was only marginally significant. There was no difference between the grammatical and noun-article condition. Finally, native Mandarin speakers showed significantly longer go-past times in the noun-adjective (1206 ms) and the noun-article (1107 ms) conditions than the grammatical condition (795 ms). They showed no difference in go-past times between the two ungrammatical conditions.

Total time

There was a main effect of grammaticality in total time, such that total times were shorter in the noun-article condition (923 ms) than the grammatical (1152 ms), and the noun-adjective (1162 ms) conditions, although this was not significant in the analysis by items. There was a difference between the grammatical (2251 ms) and noun-adjective (2808 ms) conditions that was significant only in the analysis by items. Native language group and grammaticality condition did not interact.

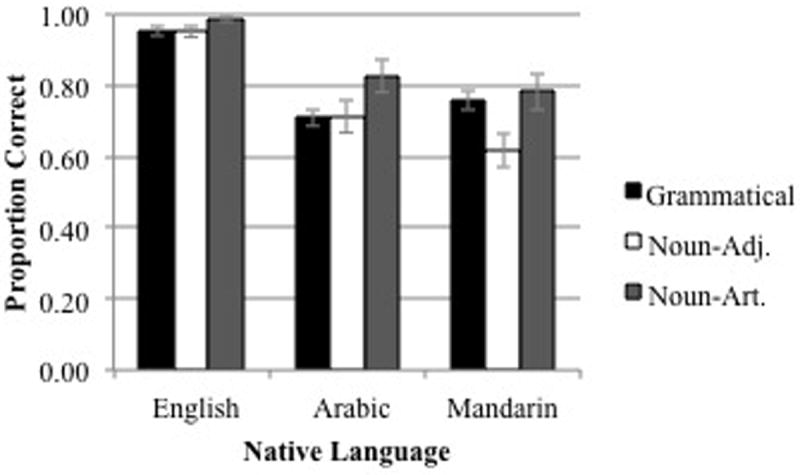

Grammaticality Judgment Task

Table 6 provides the statistical tests for all analyses on the grammaticality judgment data. Grammaticality condition reliably influenced grammaticality judgments. Post-hoc analyses showed that the noun-article condition was judged more accurately (87 %) than the grammatical condition (80 %) and the noun-adjective condition (77 %) (see Figure 1). This is consistent with our finding that eye movements were most sensitive to ungrammaticality in the noun-article condition. Native language group also influenced grammaticality judgments. Native English speakers (96 %) responded more accurately than native Arabic (75 %) and native Mandarin speakers (72 %), who didn’t differ from each other. These main effects were qualified by an interaction between grammaticality condition and native language group. Native English speakers responded more accurately in the noun-article condition (99 %) than the grammatical (95 %) or noun-adjective conditions (95 %). Similarly, the native Arabic speakers responded more accurately in the noun-article condition (82 %) than to the grammatical sentences (71 %) or the noun-adjective sentences (72 %). The native Mandarin speakers responded more accurately in both the grammatical (75 %) and the noun-article (79 %) condition than the noun-adjective condition (63 %).

Table 6. Statistical tests on grammaticality judgement measures.

| Effect | Subjects | Items |

|---|---|---|

| Native language group | 26.91 (1.05)** | 88.35 (2.93)** |

| Native English vs. native Arabic | 6.28** | 11.41** |

| Native English vs. native Mandarin | 8.31** | 13.32** |

| Native Arabic vs. native Mandarin | <1 | 1.07 |

| Grammaticality condition | 9.14 (0.15)** | 13.36 (0.44)** |

| Noun–adjective vs. grammatical | 1.44 | 1.70 |

| Noun–article vs. grammatical | 2.39* | 2.91** |

| Noun–adjective vs. noun–article | 5.13** | 4.26** |

| Native Language × Grammaticality Condition | 2.43 (0.05), p =.051 | 3.34(0.11)* |

| Native English | ||

| Noun–adjective vs. grammatical | <1 | <1 |

| Noun–article vs. grammatical | 2.47* | 2.08* |

| Noun–adjective vs. noun–article | 1.70 | 2.31* |

| Native Arabic | ||

| Noun–adjective vs. grammatical | <1 | <1 |

| Noun–article vs. grammatical | 2.91** | 2.86** |

| Noun–adjective vs. noun–article | 4.42** | 2.51* |

| Native Mandarin | ||

| Noun–adjective vs. grammatical | 2.15, p = .05 | 3.14** |

| Noun–article vs. grammatical | <1 | 1.13 |

| Noun–adjective vs. noun–article | 3.52** | 3.87** |

Note: Values represent F-test statistics for main effects and interactions with mean square errors in parentheses, and t-test statistics for pair-wise comparisons.

p <.05.

p <.01.

Figure 1.

Grammaticality judgment accuracy by native language group and grammaticality.

Discussion

Native Arabic, Mandarin, and English speakers all showed very quick sensitivity to violations in noun-article sentences, as evidenced by longer first fixation times, more first pass regressions out and the longest go past reading times in the target region in this condition. Given that the critical region was three words long, the first fixation effects should be interpreted cautiously, because they are likely based on the processing of only the first few characters or word of the region and could simply indicate that readers may have been able to detect a noun-article violation closer to the left edge of the region than a noun-adjective violation. However, the fact that this same effect appeared in first pass regressions out and go past, which are more meaningful measures on a multi-word region, suggests that it is a real effect. This likely reflects the fact that there were more, stronger, and earlier-encountered cues to ungrammaticality in the noun-article condition. Consistent with this first-pass reading evidence for quick and strong sensitivity to ungrammaticality in the noun-article condition, this condition also was associated with the most accurate grammaticality judgments across groups. This striking consistency across native language groups suggests that the cues to this violation had been similarly well learned by the native Mandarin speakers, whose native language does not have articles, and the native English and native Arabic speakers, in whose languages articles precede nouns. By the post-target region, Native English speakers showed little on-line disruption to either ungrammatical condition, but did do more re-reading of the ungrammatical conditions, as evidenced by total times.

The noun-adjective condition seems a more likely candidate for observing transfer effects, given that: (1) it had fewer and likely weaker cues to ungrammaticality, and (2) negative transfer was predicted for the native Arabic speakers because the noun-adjective ordering is grammatical in Arabic. However, even in this condition there was no evidence of transfer.4 Native Arabic speakers showed disruption as early as go past times on the target region in the noun-adjective condition. This was only slightly later than the native English speakers began showing disruption, and possibly earlier than native Mandarin speakers, who should have had positive transfer from their L1 to help them determine that this word order was ungrammatical. In the post-target region, both L2 groups showed more disruption for this noun-adjective condition than the noun-article condition. The longer persistence of this disruption and the fact that grammaticality judgments were less accurate in the noun-adjective condition suggest that participants may have been less sure of their judgments in this condition than in the noun-article condition. Greater difficulty judging the grammaticality of the noun-adjective word order is not consistent with the UCM predictions of transfer for the native Mandarin speakers, given that this word order is ungrammatical in Mandarin. The weakness of the noun-article condition highlights the importance of the strength and availability of cues in the input, as predicted by the UCM.

Given the considerable previous evidence indicating that cross-language transfer affects L2 processing (e.g., McDonald, 1987; Sabourin & Stowe, 2008; Sabourin, Stowe, & Haan, 2006; Tokowicz & MacWhinney, 2005; Tokowicz & Warren, 2010), the question arises: why was there no evidence of transfer in the current study? Here we consider two potential contributing factors: the nature of our violations and the proficiency of our participants. We think the likeliest factor driving our lack of transfer effects was that violations in this study were unlike many from previous studies of cross-language similarity, in that they involved very salient changes in word order. Most previous studies have investigated morpho-syntactic agreement or relative clause attachment, both of which can occasionally cause difficulty even for native speakers of a language (e.g., Pearlmutter, Garnsey, & Bock, 1999; Swets et al., 2007). Word order may be more strongly learned and represented, and thus less likely to be affected by transfer. A second, perhaps less likely, factor driving our lack of transfer effects was our participants. They were in the highest two (of five) levels of English Language Institute classes, suggesting at least a moderate (to high) level of proficiency, and immersed in an English language university environment when they participated in the study. Although the grammaticality judgment performance of our learners was not very good, our participants were more proficient and had more exposure to their L2 simply by virtue of living in Pittsburgh and taking intensive classes at the ELI than the beginning L2 classroom learners who showed transfer effects in studies like Tokowicz and MacWhinney (2005) and Tokowicz and Warren (2010). If cross-language transfer effects result from an initial porting over of cue strengths from a native language at the beginning of L2 learning, it would make sense that they could be washed out for speakers who are even slightly more proficient or more immersed in an environment with strong L2 cues (e.g., McDonald, 1987). This would suggest that relative proficiency within our set of participants should not relate to performance as much as the salience of cues. To examine this, we correlated L2 speakers’ d-prime scores for the grammaticality judgments with the difference scores for regressions out and go-past reading measures. These analyses showed no significant correlations between these measures, suggesting that proficiency as measured by grammaticality judgment performance is not related to the reading effects we observed. A stronger test of the hypothesis that our participants’ relatively higher proficiency is responsible for the lack of transfer effects would require additional research.

Another possible account of the lack of transfer effects is that participants could have treated the experiment as a problem-solving task in which they used their metalinguistic knowledge of English to judge grammaticality. Personal correspondence with an ELI teacher who taught all four classes (reading, writing, listening, and speaking) indicated that students receive explicit instruction in English, reviewing the parts of speech and how they are used. However, receiving explicit instruction on word order in English would presumably make it easier to judge grammaticality and detect illicit word orders. Although we cannot completely rule out the possibility of participants using a metalinguistic approach to judging the sentences, we would expect better, i.e. more accurate, grammaticality judgments from L2 speakers if they were.

There were a few patterns of results in the current study that could be considered somewhat surprising. First, grammaticality judgment performance was better in the ungrammatical noun-article condition than in the grammatical condition. It is unusual for grammaticality judgment performance to be better on ungrammatical than grammatical strings, but the fact that this pattern held even for native English speakers supports our claim that the cues to ungrammaticality in these noun-article sentences were extremely strong and clear. Additionally, it is possible that the relatively low accuracy on grammatical sentences for the L2 speakers could be related to the presence of these very clear “no” judgments. In most grammaticality judgment experiments that test more subtle morpho-syntactic violations like gender or number agreement, L2 learners tend to have a yes-bias (e.g., Tokowicz & MacWhinney, 2005), which inflates their accuracy on grammatical sentences and depresses it on ungrammatical sentences. In this experiment, the presence of very clear ungrammatical sentences may have reduced that yes-bias. A second potentially surprising finding is the fact that the noun-article condition is sometimes processed more quickly than the other two conditions in the post-target region. This reversal from the target region would not be expected in a situation in which participants were trying to repair the violations they encountered; in those kinds of situations, disruption tends to be sustained into subsequent regions (e.g. Warren & McConnell, 2007). However, given that in the current experiment, the participants’ task was to judge grammaticality, it makes sense that their processing might speed up once they identified a clear cue to ungrammaticality.

Eye-movement patterns across the native language groups indicate potentially interesting differences in reading strategies across the groups. Overall, native Arabic speakers tended to have longer first pass reading times and do more re-reading than the other two groups. Native Mandarin speakers tended to skip the target region more often than the other two groups, but otherwise their reading was more similar to that of the native English speakers. However, when native Mandarin speakers had a first pass regression out of a region, they seemed to do slightly less re-reading than the other two groups did before progressing beyond the region. This is most strongly evident on the post-target region, from which the native Mandarin speaking group made significantly more regressions than the other two groups (possibly because they skipped the target region more often), yet had numerically shorter go past times than the native Arabic speakers.

There are also interesting similarities in reading across the three groups. The consistent first fixation effects for the noun-article condition are striking, especially given the fact that sensitivity to syntactic violations is sometimes not evident until later measures even for native speakers (e.g., Patson & Ferreira, 2009). The fact that first fixation durations were inflated for all groups suggests that there was a relatively strong cue to ungrammaticality at or very near the first word of the target region. The most likely cue was the presence of a bare noun in the direct object position, given that it was the first word in the region. One potential problem for this account would seem to be the fact that in most items, the bare noun could have been followed naturally by another noun (e.g. “He decided to buy kitten toys…”), and thus was not necessarily a strong cue to ungrammaticality. However, Staub, Rayner, Pollatsek, Hyona, and Majewski (2007) found first fixation duration effects associated with temporary semantic anomalies on exactly these types of bare nouns, even in an experiment in which nouns that remedied the anomalies always followed the bare nouns. It is therefore possible that the presence of the bare noun was a strong cue. An additional possibility is that in some cases, e.g., when the noun was relatively short and high frequency, participants may have been able to process the upcoming “the” in their parafovea and may have registered the noun-article bigram as a cue as well. Regardless of which exact cue or combination of cues drove this first fixation effect in the noun-article condition, the presence of the effect for all native language groups indicates that it was strong, well-learned, and available early in processing.

Conclusion

Overall, our results demonstrate quick sensitivity to word order violations in L2, particularly for violations that had more and stronger cues to ungrammaticality. Although we did not find the expected pattern of transfer for native Arabic and Mandarin speakers in the noun-adjective condition, this may be due to the proficiency or amount of exposure to word order cues of our L2 groups and the relative strength of word order cues. Taken as a whole, these findings are not inconsistent with the basic mechanisms hypothesized by the UCM, but they add complexity to the previous literature’s findings regarding the UCM’s predictions for L2 processing.

Acknowledgments

We thank Erik Reichle for access to the eye-tracking lab and procedure and Katherine Martin for her extensive help with the procedure and data collection. During the writing of this manuscript, Alba Tuninetti was supported by the Behavioral Brain Training Grant, NIH 2T32GM081760-06 and 5T32GM081760-04, Tessa Warren was supported by NIH R01 DC011520, and Natasha Tokowicz was supported by NIH R01 HD075800. We thank four anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on our manuscript.

Footnotes

In a few items the adjectives could either have been interpreted as being resultatives or initiating an adjective phrase (e.g. the shirt striped with blue and white…”). For these few items, a savvy reader might not have detected grammaticality violations until the post-target region.

Ten native English-speaking participants who did not participate in the eye-tracking study rated the naturalness of our items truncated after the first word in the target region, i.e. “She pulled skirt” vs. “She pulled the”, on a scale from 1 to 7 on which 1 indicated “very natural” and 7 indicated “very unnatural”. Items were distributed across two counterbalancing lists so no participant saw two versions of the same item. Participants rated sentence fragments ending with nouns as significantly more unnatural than fragments ending with “the” (4.54 vs. 1.58), t (55) = 17.57, p < .01, indicating that the bare noun may have been an additional cue to ungrammaticality.

However, it is important to note that Mandarin Chinese precedes its nouns with determiners, which are thought of as functional equivalents of “this” and “that” in English (Robertson, 2000). Definiteness and indefiniteness may be marked by certain prefixes, but this marking is not required (Li & Thompson, 1997). The possibility arises that Mandarin learners of English may build on their knowledge of these determiners to facilitate acquisition of articles in English, and if our learners do this, then the article-noun construction might be better categorized as similar to the L1 rather than unique to the L2. To foreshadow, however, the noun-adjective condition is much more important to our arguments about cross-language transfer than the noun-article condition, so the exact categorization of the noun-article condition ultimately is not critical.

Additional analyses including the entire set of participants that was tested showed a similar pattern of findings.

Contributor Information

Alba Tuninetti, Email: alt63@pitt.edu, Department of Psychology, Learning Research & Development Center, 3939 O’Hara St., Room 651, University of Pittsburgh; Pittsburgh, PA 15260; USA.

Tessa Warren, Email: tessa@pitt.edu, Department of Psychology, Learning Research & Development Center, 3939 O’Hara St., Room 635, University of Pittsburgh; Pittsburgh, PA 15260; USA.

Natasha Tokowicz, Email: tokowicz@pitt.edu, Department of Psychology, Learning Research & Development Center, 3939 O’Hara St., Room 634, University of Pittsburgh; Pittsburgh, PA 15260; USA.

References

- Bates E, MacWhinney B. Competition, variation, and language learning. In: MacWhinney B, editor. Mechanisms of Language Acquisition: The 20th Annual Carnegie Symposium on Cognition; Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman J. About the General Service List. 2010 Retrieved September 11, 2010, from http://jbauman.com/aboutgsl.html#1953.

- Bohan J, Sanford AJ. Semantic anomalies at the borderline of consciousness: An eye-tracking investigation. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2008;61:232–239. doi: 10.1080/17470210701617219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J. Chinese Speakers. In: Swan M, Smith B, editors. Learner English: A teacher’s guide to interference and other problems. Second Edition. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, England: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Clahsen H, Felser C. Grammatical processing in language learners. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2006a;27:3–42. [Google Scholar]

- Clahsen H, Felser C. How native-like is non-native language processing? Trends in Cognitive Science. 2006b;10:564–570. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies M. N-grams data from the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) 2011 Downloaded from http://www.ngrams.info on November 29, 2012.

- Dussias P. Syntactic ambiguity resolution in L2 learners: Some effects of bilinguality on L1 and L2 processing strategies. Studies in Second Language Acquisition. 2003;25:529–557. [Google Scholar]

- Dussias PE, Sagarra N. The effect of exposure on syntactic parsing in Spanish English bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2007;10:101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis R. Grammatically judgments and second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition. 1991;13(02):161–186. doi: 10.1017/S0272263100009931. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frenck-Mestre C, Pynte J. Syntactic ambiguity resolution while reading in second and native languages. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1997;50:119–148. [Google Scholar]

- Li CN, Thompson S. Mandarin Chinese: a functional reference grammar. Taipei: Crane Publishing; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney B. A unified model of language acquisition. In: Kroll JF, DeGroot AMB, editors. Handbook of Bilingualism: Psycholinguistic Approaches. Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JL. Beyond the critical period: Processing-based explanations for poor grammaticality judgment performance by late second language learners. Journal of Memory and Language. 2006;55:381–401. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlmutter NJ, Garnsey SM, Bock K. Agreement processes in sentence comprehension. Journal of Memory and Language. 1999;41:427–456. [Google Scholar]

- Patson ND, Ferreira F. Conceptual plural information is used to guide early parsing decisions: Evidence from garden-path sentences with reciprocal verbs. Journal of Memory and Language. 2009;60:464–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picton TW, Bentin S, Berg P, Donchin E, Hillyard SA, Johnson R, Jr, Miller GA, Ritter W, Ruchkin DS, Rugg MD, Taylor MJ. Guidelines for using human event-related potentials to study cognition: Recording standards and publication criteria. Psychophysiology. 2000;37:127–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K. Eye movements in reading and information processing: 20 years of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;124:372–422. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.3.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts L. Individual Differences in Second Language Sentence Processing. Language Learning. 2012;62:172–188. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson D. Variability in the use of the English article system by Chinese learners of English. Second Language Research. 2000;16:135–72. [Google Scholar]

- Rogerson HD, Davis B, Hershelman ST, Jasnow C. Words for students of English: A vocabulary series for ESL. Vol. 1. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rogerson HD, Esarey G, Hershelman ST, Jasnow C, Moltz C, Schmandt LM, Smith DA. Words for students of English: A vocabulary series for ESL. Vol. 4. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rogerson HD, Hershelman ST, Jasnow C, Moltz C. Words for students of English: A vocabulary series for ESL. Vol. 3. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sabourin L, Stowe L. Second-language processing: when are first and second languages processed similarly? Second Language Research. 2008;25(3):397–430. [Google Scholar]

- Sabourin L, Stowe L, de Haan GJ. Transfer effects in learning a second language grammatical gender system. Second Language Research. 2006;22(1):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Staub A, Rayner K, Pollatsek A, Hyönä J, Majewski H. The time course of plausibility effects on eye movements in reading: evidence from noun-noun compounds. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition. 2007;33:1162–1169. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.33.6.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swets B, Desmet T, Hambrick DZ, Ferreira F. The role of working memory in syntactic ambiguity resolution: A psychometric approach. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2007;136:64–81. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.136.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swets B, Desmet T, Clifton C, Ferreira F. Underspecification of syntactic ambiguities: Evidence from self-paced reading. Memory & Cognition. 2008;36:201–216. doi: 10.3758/mc.36.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokowicz N, Michael EB, Kroll JF. The roles of study-abroad experience and working-memory capacity in the types of errors made during translation. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2004;7:255–272. [Google Scholar]

- Tokowicz N, MacWhinney B. Implicit and explicit measures of sensitivity to violations in second language grammar: An event-related potential investigation. Studies in Second Language Acquisition. 2005;27:173–204. [Google Scholar]

- Tokowicz N, Warren T. Beginning adult L2 learners’ sensitivity to morphosyntactic violations: A self-paced reading study. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Warren T, McConnell K. Disentangling the effects of selectional restriction violations and plausibility violation severity on eye-movements in reading. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2007;14(4):770–775. doi: 10.3758/bf03196835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West M. A general service list of English words. London, UK: Longman; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Witzel J, Witzel N, Nicol J. The reading of structurally ambiguous sentences by English language learners. Paper presented at the Workshop on Second Language Processing and Parsing: State of the Science; Lubbock, TX. 2009. May, [Google Scholar]

- Zdorenko T, Paradis J. The acquisition of articles in child second language English: fluctuation, transfer, or both? Second Language Research. 2008;24:227–250. [Google Scholar]