Abstract

The acute impairing effects of alcohol on inhibitory control are well-established, and these disinhibiting effects are thought to play a role in its abuse potential. Alcohol impairment of inhibitory control is typically assessed in the context of arbitrary cues, yet drinking environments are comprised of an array of alcohol-related cues that are thought to influence drinking behavior. Recent evidence suggests that alcohol-related stimuli reduce behavioral control in sober drinkers, suggesting that alcohol impairment of inhibitory control might be potentiated in the context of alcohol cues. The current study tested this hypothesis by examining performance on the attentional-bias behavioral activation (ABBA) task that measures the degree to which alcohol-related stimuli can reduce inhibition of inappropriate responses in a between-subjects design. Social drinkers (N=40) performed the task in a sober condition, and then again following placebo (0.0 g/kg) and a moderate dose of alcohol (0.65 g/kg) in counter-balanced order. Inhibitory failures were greater following alcohol images compared to neutral images in sober drinkers, replicating previous findings with the ABBA task. Moreover, alcohol-related cues exacerbated alcohol impairment of inhibitory control as evidenced by more pronounced alcohol-induced disinhibition following alcohol cues compared to neutral cues. Finally, regression analyses showed that greater alcohol-induced disinhibition following alcohol cues predicted greater self-reported alcohol consumption. These findings have important implications regarding factors contributing to binge or ‘loss of control’ drinking. That is, the additive effect of disrupted control mechanisms via both alcohol-cues and the pharmacological effects of the drug could compromise an individual’s control over ongoing alcohol consumption.

Keywords: alcohol, inhibition, behavioral control, alcohol cues, cued go/no-go task

Introduction

The link between impaired inhibitory control and problematic alcohol consumption has been recognized for some time. Limiting one’s alcohol consumption necessarily requires a certain degree of behavioral control, and thus deficits in inhibitory mechanisms are thought to compromise the ability to control one’s drinking. Studies have tested this association using inhibitory control tasks that require participants to respond as quickly as possible to go signals, but inhibit their responses when stop or no-go signals occasionally appear (e.g., stop signal and go/no-go tasks). As hypothesized, heavy drinkers and alcoholics display deficits in response inhibition compared to social-drinking controls (Bjork, Hommer, Grant, & Danube, 2004; Henges & Marczinski, 2012; Lawrence, Luty, Bogdan, Sahakian, & Clark, 2009; Rubio, Jimenez, Rodriguez-Jimenenz, Martinez, Avila, Ferre, et al., 2008), and longitudinal studies show that deficits in response inhibition can predict greater alcohol use later in life (Nigg, Wong, Martel, Jester, Puttler, Glass, et al., 2006; Rubio et al., 2008). Alcohol consumption acutely impairs performance on these tasks as well (de Wit, Crean, & Richards, 2000; Dougherty, Moeller, Steinberg, Marsh, Hines, & Bjork, 1999; Fillmore & Vogel-Sprott, 1999; Marczinski & Fillmore, 2003), and initial evidence suggests an association between alcohol-induced impairment of inhibitory control and excessive, binge-like consumption. For instance, binge drinkers are more sensitive to the disinhibiting effects of the drug (Marczinski, Combs, & Fillmore, 2007), and individual differences in sensitivity to the disinhibiting effects of alcohol predict ad lib consumption (Gan, Guevara, Marxen, Neumann, Junger, Kobiella, et al., in press; Weafer & Fillmore, 2008). In sum, there is a wealth of evidence demonstrating an association between impaired control and excessive alcohol consumption in both sober and intoxicated drinkers.

The majority of evidence implicating impaired behavioral control in alcohol abuse has assessed response inhibition to arbitrary cues (e.g., colors, geometric shapes and simple auditory tones). However, drinking environments are comprised of a rich array of discrete and contextual cues that are reliably associated with the consumption of alcohol (e.g., beer bottles, wine glasses, neon bar signs, bar rooms), and these cues are thought to play an influential role in drinking behavior. According to the incentive-sensitization theory, drug cues come to be associated with drug-taking and the rewarding effects of the drug, causing the cues to become increasingly salient for the drug user, and to acquire incentive-motivational properties that promote drug-seeking and drug-taking (Robinson & Berridge, 1993, 2001). In terms of alcohol abuse, individuals with a history of heavy drinking show an attentional bias towards alcohol-related stimuli, and this is thought to be indicative of enhanced incentive-salience of alcohol cues (Ceballos, Komogortsev, & Turner, 2009; Fadardi & Cox, 2008; Field, Christiansen, Cole, & Goudie, 2007; Miller & Fillmore, 2010; Murphy & Garavan, 2011; Sharma, Albery, & Cook, 2001; Tibboel, De Houwer, & Field, 2010; Townshend & Duka, 2001; Weafer & Fillmore, 2013). Importantly, there is also evidence that attention towards alcohol-related stimuli is associated with increased craving (Field & Cox, 2008; Field, Munafo, & Franken, 2009).

Recent models of drug addiction emphasize the reciprocal influence of incentive-motivational properties of drug-related cues and impaired inhibitory control over drug taking (Dawe & Loxton, 2004; Feil, Sheppard, Fitzgerald, Yucel, Lubman, & Bradshaw, 2010; Goldstein & Volkow, 2002; Jentsch & Taylor, 1999). These models cite neuroanatomical evidence implicating frontostriatal circuitry dysfunction in both salience attribution and response inhibition, and propose that the intense motivation elicited by drug-associated cues could serve to directly impair control mechanisms necessary to inhibit the cue-induced impulse. In terms of alcohol abuse, attention directed towards alcohol cues could thus serve to acutely disrupt mechanisms of inhibitory control in heavy drinkers. We tested this hypothesis in a recent study by modifying the traditional cued go/no-go task to assess inhibitory control following both alcohol-related and neutral cues (Weafer & Fillmore, 2012). The modified task is called the attentional bias-behavioral activation (ABBA) task and presents either a test condition in which alcohol-related images signal that a response is required or a test condition in which neutral images signal that a response is required. The cues serve to increase response activation and make inhibition difficult on the occasional instances when the response must be suddenly inhibited. In accord with the hypothesis that alcohol cues should impair control mechanisms necessary to inhibit the cue-induced impulse, we showed that inhibitory control was disrupted to a greater degree following alcohol cues compared with neutral cues (Weafer & Fillmore, 2012). Similar results have since been reported from other laboratories using similarly modified cued go/no-go tasks (Fleming & Bartholow, 2013; Kreusch, Vilenne, & Quertemont, 2013). Taken together, these findings provide preliminary evidence for a disruptive effect of alcohol-related stimuli on the ability to inhibit prepotent (i.e., instigated) responses (although see Nederkoorn, Baltus, Guerrieri, & Wiers, 2009).

Given the evidence that inhibitory control can be compromised by the presence of alcohol-related stimuli in the immediate environment, it is important to consider this disruptive effect in the intoxicated individual. Alcohol is well-known for its ability to acutely impair inhibitory control over pre-potent responses in laboratory tasks, such as the cued go/no-go model (for a review see, Fillmore & Weafer, 2013). Such acute impairment of inhibitory control could be especially pronounced in the context of alcohol-related environmental stimuli that also disrupt response inhibition. Such potential additive or over-additive impairments could be particularly important for understanding associations between alcohol-induced disinhibition and binge drinking. As termination of a drinking episode likely occurs in the context of alcohol-related stimuli, greater sensitivity to the acute disinhibiting effects of alcohol in the presence of such stimuli could further disrupt the ability to stop drinking. To our knowledge, only two studies to date have sought to examine the degree to which alcohol effects on inhibition might be exacerbated following alcohol-related images (Adams, Ataya, Attwood, & Munafo, 2013; Rose & Duka, 2008). These studies examined performance on alcohol shifting tasks, where participants shifted between responding to alcohol-related or neutral images following consumption of alcohol or placebo. However, neither study reported a significant main effect of alcohol on disinhibition (regardless of cue type), thus precluding analyses regarding the potentially exacerbating effects of alcohol cues on alcohol-induced disinhibition. The failure to observe a general disinhibiting effect of alcohol in these studies is likely due to limitations of the shifting task as a measure of inhibitory control. In typical go/no-go models, strong response prepotency is established by making the go response dominant, with no-go targets appearing only occasionally. This makes inhibition difficult when a no-go signal unexpectedly occurs. By contrast, the alcohol-shifting task requires participants to shift between responding to alcohol-related or neutral images. Because the ‘go’ target continually shifts throughout the test, a strong prepotent response is less likely to be established, thus limiting the ability to detect alcohol or alcohol-cue effects on inhibition.

For the current study, we compared the magnitude of alcohol-induced disinhibition following alcohol-related versus neutral cues on the ABBA task in a sample of non-dependent, social drinkers. The ABBA task was adapted from a cued go/no-go model in which sensitivity to the disinhibiting effects of alcohol has been well-documented (Fillmore & Weafer, 2013). Further, we have previously demonstrated that alcohol images elicit a strong prepotent response tendency on the ABBA task, as evidenced by significantly disrupted inhibitory control following alcohol cues (Weafer & Fillmore, 2012). In order to replicate our previous findings, participants first performed the task in a sober state. They then completed a placebo-controlled test of the acute effect of 0.65 g/kg alcohol on their inhibitory control in the context of alcohol-related versus neutral cues. We hypothesized that the ability to inhibit responses would be generally poorer when tested in the context of alcohol cues compared with neutral cues, and that alcohol would impair inhibitory control overall. Moreover, we expected an additive effect of alcohol cues and alcohol intoxication, such that disinhibition would be most pronounced following alcohol consumption in the context of alcohol cues versus neutral cues. To examine the degree to which disrupted inhibitory control following alcohol cues is associated with excessive alcohol consumption, we also tested associations of drinkers’ self-reported drinking habits with their inhibitory failures following alcohol and neutral cues. We hypothesized that greater disinhibition would be associated with greater alcohol consumption, and that this association would be stronger for inhibitory failures following alcohol cues. That is, individuals who experience the most difficulty inhibiting responses to alcohol cues were expected to report more excessive drinking patterns, perhaps due to difficulty inhibiting consumption in the presence of such cues.

Method

Participants

Forty adult beer drinkers (11 women and 29 men) between the ages of 21 and 29 years (mean age = 23.3, SD = 2.8) were recruited to participate in this study. Screening measures were conducted to determine medical history and current and past drug and alcohol use. Any volunteers who self-reported head trauma, psychiatric disorder, or substance abuse disorder were excluded from participation. Volunteers who reported alcohol dependence, as determined by a score of 5 or higher on the Short-Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (S-MAST; Selzer, Vinokur, & van Rooijen, 1975), were also excluded. Volunteers were recruited via notices placed on community bulletin boards and by university newspaper advertisements. The University of Kentucky Medical Institutional Review Board approved the study, and participants were compensated for their participation.

Materials and Measures

Attentional Bias-Behavioral Activation (ABBA) task (Weafer & Fillmore, 2012)

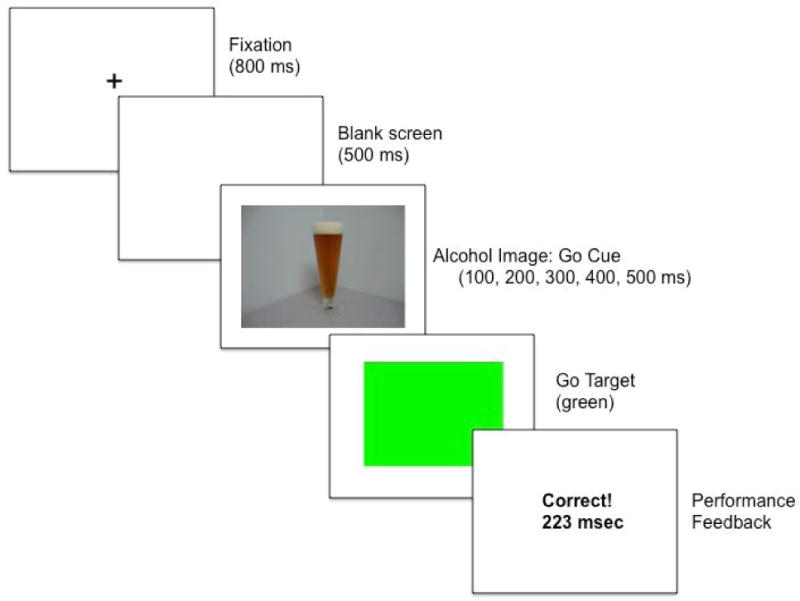

The ABBA task, a modified cued go/no-go reaction time task, was operated using E-prime experiment generation software (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA) and was performed on a PC. A trial involved the following sequence of events: (a) presentation of a fixation point (+) for 800 ms; (b) a blank white screen for 500 ms; (c) a cue image (alcohol or neutral), displayed for one of five stimulus onset asynchronies (SOAs = 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 ms); (d) a go or no-go target, which remained visible until a response occurred or 1,000 ms had elapsed; and (e) an intertrial interval of 700 ms.

The cues consisted of ten alcohol-related images (e.g., beer can, six-pack of beer bottles) and ten neutral images (e.g., stapler, paper towel roll) set against a neutral backdrop. Alcohol and neutral images were matched in terms of size, complexity, color, and brightness. These were 15 cm × 11.5 cm images presented in the center of the computer monitor against a white background. The alcohol beverage type was always beer. Cue presentation was randomized to prevent any unintentional order effects on task performance across participants, and to prevent any anticipation of cue presentation on repeated task performance within subjects. After an SOA the cue image turned either solid green (go target) or solid blue (no-go target). Participants were instructed to press the forward slash (/) key on the keyboard as soon as a green (go) target appeared and to suppress the response when a blue (no-go) target was presented. Key presses were made with the right index finger. The different SOAs between cues and targets prevented participants from anticipating the exact onset of the targets. A schematic of a trial in which an alcohol cue turns into a go target is presented in Figure 1.

Fig 1.

Schematic of a trial in the alcohol go condition on the ABBA task. Following the fixation point, an alcohol image is presented. Alcohol images precede go targets on the majority of trials in this condition, and as such alcohol images serve as go cues and increase difficulty of inhibition. The go target is then presented, and the participant executes the response as quickly as possible. The computer provides feedback immediately following the response.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two task conditions: alcohol go or neutral go. In the alcohol go condition, alcohol images turned into the go target on 80% of trials and turned into the no-go target on only 20% of trials. Therefore, alcohol images operated as go cues, based on the high probability that they would signal go targets. As such, these images should speed reaction time (RT) to the go targets, but also increase failures to inhibit the response when the no-go target is occasionally presented. By contrast, in the neutral go condition the opposite cue image-target pairings were presented. Therefore, in this condition neutral images serve as go cues, producing faster RT to go targets, but more inhibitory failures to the occasional presentation of no-go targets. By comparing the alcohol go condition and neutral go condition (between-subjects), the task measures the degree to which alcohol-related go cues elicit poorer response inhibition compared to neutral go cues.

A test consisted of 250 trials, presented as 5 blocks of 50 trials each, with each individual cue presented 12 or 13 times. For each trial, the computer recorded whether a response occurred and, if so, the RT in milliseconds was measured from the onset of the target until the key was pressed. To encourage quick and accurate responding, the computer presented feedback to the participant during the intertrial interval by displaying the words correct or incorrect along with the RT in milliseconds. Omission errors (when participants failed to respond to go targets) were also recorded. These were infrequent and occurred on less than 0.005% of go target trials (i.e., less than one trial per test). Each block required approximately 2.5 min to complete and blocks were separated by 30 sec breaks, for a total test time of approximately 15 min.

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS; Patton, Stanford, & Barratt, 1995)

Participants completed the BIS to provide a self-report measure of the personality dimension of impulsivity. Impulsivity is thought to contribute to the risk of behavioral disinhibition under alcohol, as well as risk for alcoholism (Boyatzis, 1975; Cloninger, 1987; Finn, Kessler, & Hussong, 1994; Sher & Trull, 1994). Participants indicate how typical each of 30 statements (e.g., “I am self controlled”) is for them on a 4-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicated greater total levels of impulsiveness. This measure was included to ensure that groups did not differ in terms of impulsive personality.

Time Line Follow-Back (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1992)

Participants completed a retrospective time line calendar of their alcohol consumption for the past three months to assess daily patterns of drinking, including number of binge episodes. The measure uses “anchor points” to structure and facilitate participants’ recall of past drinking episodes. For each day, participants estimated the number of standard drinks they consumed and the number of hours they spent drinking. This information, along with gender and body weight, was used to estimate the resultant BAC obtained for each drinking day. This was done using well-established, valid anthropometric-based BAC estimation formulae that assume an average clearance rate of 15 mg/dl per hour of the drinking episode (McKim, 2007; Watson, Watson, & Batt, 1981). These formulae have been used in previous studies and have been shown to yield high correlations with actual resultant BACs obtained under laboratory conditions (Fillmore, 2001). Any day in which the estimated resultant BAC was 80 mg/100 ml or higher was classified as a binge episode (NIAAA, 2004). The TLFB provided three measures of drinking habits over the past three months: (a) drinking days (total number of days alcohol was consumed); (b) binge days (total number of binge episodes); and (c) total drinks (total number of drinks consumed over the three months).

Subjective intoxication

Degree of subjective intoxication was measured on a visual analogue scale that has been used in previous research on acute alcohol tolerance (e.g., Ostling & Fillmore, 2010). Participants rated their degree of subjective intoxication by placing a vertical line at the point representing the extent to which they ‘feel intoxicated’ on a 100-mm horizontal line ranging from 0 mm “not at all” to 100 mm “very much.”

Procedure

Interested volunteers responded to study advertisements by calling the laboratory to participate in an intake-screening interview conducted by a research assistant. At that time, they were informed that the purpose of the study was to examine the effects of alcohol on behavioral tasks. Volunteers were asked to report their preferred alcoholic beverage (beer, wine, or liquor). Because all alcohol-related stimuli presented in the ABBA task consisted of beer images, only volunteers reporting beer as their preferred beverage were eligible for study participation. All sessions were conducted in the Behavioral Pharmacology Laboratory of the Department of Psychology and testing began between 10 a.m. and 6 p.m. All participants were tested individually. Sessions were scheduled at least 24 hours apart and were completed within three weeks. Participants were instructed to fast for four hours prior to each alcohol session, as well as to refrain from consuming alcohol or any psychoactive drugs or medications for 24 hours before all sessions. Prior to each session, participants provided urine samples that were tested for drug metabolites, including amphetamine, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cocaine, opiates, and tetrahydrocannabinol (ON trak TesTstiks, Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and, in women, HCG, in order to verify that they were not pregnant (Mainline Confirms HGL, Mainline Technology, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Breath samples were also provided and analyzed by an Intoxilyzer, Model 400 (CMI, Inc., Owensboro, KY, USA) at the beginning of each session to verify a zero breath alcohol content (BrAC).

Part 1: Sober baseline performance

All participants first completed a sober assessment of their performance on the ABBA task in order to replicate our previous findings that showed inhibitory control was poorer in the context of alcohol-related versus neutral stimuli (Weafer & Fillmore, 2012). Upon arrival to the laboratory, participants provided informed consent for participation and were familiarized with study protocol and procedures. Participants’ heights and weights were measured, and questionnaire measures were completed. Men and women were randomly assigned to either the alcohol go or the neutral go task condition such that gender make-up was equivalent across conditions. Participants then performed the ABBA task to provide a measure of sober task performance.

Part 2: Dose-challenge sessions

Part 2 of the study was designed to test the degree to which alcohol-related stimuli exacerbate the acute disinhibiting effects of a moderate dose of alcohol in a placebo-controlled design. ABBA task performance was tested following placebo (0.0 g/kg) and a moderate dose of alcohol (0.65 g/kg). The 0.65 g/kg dose was reduced to 87% for women to achieve equivalent BrACs for men and women (Fillmore, 2001; Mulvihill, Skilling, & Vogel-Sprott, 1997). Each dose was administered on a separate test session, and dose order was counter-balanced across conditions. Sessions were separated by a minimum of one day and a maximum of one week. Participants were told that they would receive alcohol on each session, and that the dose would not necessarily be the same each session. Alcohol doses were calculated on the basis of body weight and administered as absolute alcohol mixed with three parts carbonated soda. The 0.65 g/kg alcohol dose produces an average peak BAC of 80 mg/100 ml (Fillmore, Marczinski, & Bowman, 2005). The placebo dose (0.0 g/kg) consisted of a volume of carbonated mix that matched the total volume of the 0.65 g/kg alcohol drink. A small amount (3 ml) of alcohol was floated on the surface of the beverage. It was sprayed with an alcohol mist that resembled condensation and provided a strong alcoholic scent as the beverage was consumed. Previous research has shown that individuals report that this beverage contains alcohol (Fillmore & Vogel-Sprott, 1999). All drinks were consumed in six minutes.

Participants completed the subjective intoxication measure, followed by the ABBA task at 30 minutes after drinking. Participants performed the same task condition (alcohol go or neutral go) as in Part 1 following both the placebo and active dose in Part 2. Breath samples were obtained immediately prior to subjective measures and immediately following the ABBA task in order to measure participants’ BrACs. Once testing was finished, participants remained at leisure in the lounge area until their BrACs, which were monitored at 20-minute intervals, reached 20 mg/100 ml or below. Participants were provided a meal during this leisure time and were allowed to watch movies and read magazines. Transportation home was provided as needed. Upon completing the final session, participants were paid and debriefed.

Data Analyses

For Part 1, independent-groups t tests (alcohol go vs. neutral go) tested the degree to which alcohol images disrupted response inhibition (proportion (p) of inhibitory failures) and increased response activation (i.e., speeded RT) relative to neutral images during sober ABBA task performance. For Part 2, p-inhibitory failures and RT during the dose-challenge sessions were analyzed individually by 2 condition (alcohol go vs. neutral go) × 2 dose (0.0 g/kg vs. 0.65 g/kg) mixed-design analyses of variance (ANOVAs) in which dose was the within-subjects factor and condition was the between-subjects factor. Significant interactions were followed up with paired samples t tests comparing performance following placebo and 0.65 g/kg alcohol separately in each condition. For both parts of the study, we conducted hierarchical linear regression analyses to examine the extent to which individual differences in response inhibition predicted self-reported alcohol consumption as measured by the TLFB across conditions, and to test whether this relation differed according to cue condition. We hypothesized that poorer inhibitory control would predict greater alcohol consumption, and that this effect would be more pronounced in the alcohol go condition.

Results

Demographics, Trait Impulsivity, and Drinking Habit Measures

Table 1 summarizes demographic data, trait impulsivity, and drinking habit measures for participants in the alcohol go and neutral go conditions. The groups did not differ significantly in gender make-up, age, BIS scores, or alcohol consumption over the past 90 days as reported on the TLFB (ps > .10). The table shows that participants in both groups were frequent drinkers who regularly engaged in binge drinking episodes. These self-reported drinking patterns provide confirmation of participants’ frequent moderate to heavy alcohol consumption.

Table 1.

Mean demographics, trait impulsivity, and drinking habits by condition

| Condition | Contrasts | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Alcohol Go | Neutral Go | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | Sig | Cohen’s d | |

| Gender (F:M) | 6:14 | 5:15 | ns | |||

| Age | 23.4 | 3.3 | 23.2 | 2.4 | ns | .07 |

| Barratt Impulsiveness Scale | 60.2 | 7.5 | 62.5 | 9.9 | ns | .26 |

| TLFB (past 90 days) | ||||||

| Drinking days | 35.4 | 18.9 | 28.6 | 15.5 | ns | .39 |

| Binge days | 16.6 | 12.6 | 11.0 | 8.7 | ns | .52 |

| Total drinks | 190.1 | 123.6 | 165.0 | 128.1 | ns | .19 |

| Mean BrAC during testing | 80.9 | 11.9 | 86.8 | 11.0 | ns | .51 |

Note. Group contrasts were tested by between-groups t tests. ns indicates p<0.05. Effect size is indicated by Cohen’s d.

Part 1: Sober Baseline ABBA Performance

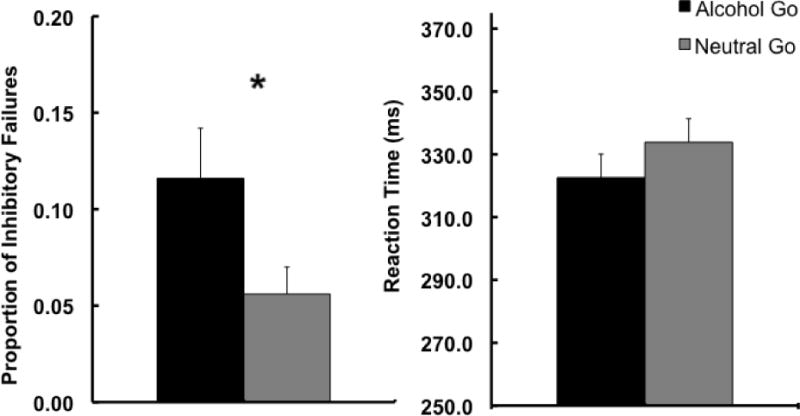

In order to first demonstrate that inhibitory control is impaired in the context of alcohol related cues as well as replicate our initial findings with the ABBA task (Weafer & Fillmore, 2012), we compared task performance in the alcohol go and neutral go conditions when participants were in the sober state in Part 1 of the study. Figure 2 presents mean p-inhibitory failures (left panel) and mean RT (right panel) following go cues for the two conditions. The figure shows greater p-inhibitory failures following alcohol images compared to neutral images. A between-groups t test confirmed that mean p-inhibitory failures were greater in the alcohol go condition compared to the neutral go condition, t(38) = 2.1, p = .047, d = .65, replicating our previous findings. Although the groups did not differ in drinking habits, p-inhibitory failures were significantly related to the measure of drinking days from the TLFB in regression analyses (see below), and so we also examined the group difference in p-inhibitory failures using a one-way ANCOVA with drinking days as a covariate. The covariate was significant, F(1, 37) = 5.1, p = .03, and the a priori group comparison (alcohol go > neutral go) of the adjusted means confirmed the group difference observed in the unadjusted means (p = .05). With regard to RT, the figure also shows that mean RT was slightly faster following alcohol images compared to neutral images. However, similar to our original findings, a between-groups t test showed that this was not a significant difference (p = .29).

Fig 2.

Mean proportion of inhibitory failures (left panel) and RT (right panel) to go cues following alcohol and neutral images on the ABBA task. Capped vertical lines represent standard errors of the mean.

Part 2: Dose-challenge Sessions

Breath alcohol concentrations

A between groups t test revealed no difference in mean BrAC over testing following 0.65 g/kg alcohol in the two conditions (Table 1; p > .10). Mean pre-test BrAC for the sample was 85.2 mg/100 ml (SD=14.5) and mean post-test BrAC for the sample was 82.5 mg/100 ml (SD=10.4). These mean BrACs were expected based on the time course of prior work indicating that BrAC peaks around 50–60 min after drinking (Fillmore and Vogel-Sprott, 1998). No detectable BrACs were observed in the placebo condition.

Subjective intoxication

Intoxication ratings were analyzed by a 2 (condition) × 2 (dose) ANOVA that revealed a significant effect of dose, F(1, 38) = 238.4, p < .001, ηp2 = .86. No main effect or interaction involving condition was observed (ps > .54). Mean intoxication ratings for the sample were 11.7 (SD = 12.4) following placebo and 56.1 (SD = 19.7) following the 0.65 g/kg dose.

ABBA Task Performance

Response Inhibition

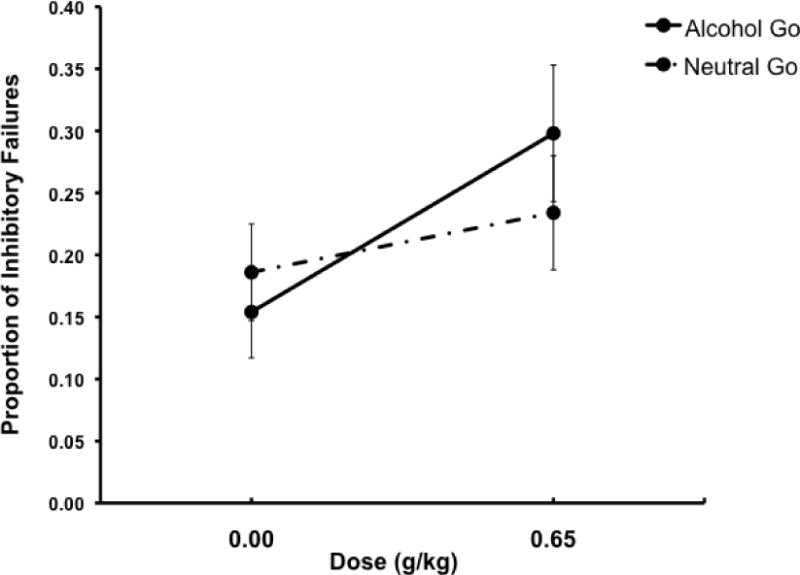

The effects of alcohol on p-inhibitory failures as measured by the ABBA task were analyzed by a 2 condition (alcohol go vs. neutral go) × 2 dose (0.0 g/kg vs. 0.65 g/kg) mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA). This analysis revealed a significant main effect of dose, F(1, 38) = 18.0, p < .001, ηp2 = .32, and a significant dose × condition interaction, F(1, 38) = 4.5, p = .040, ηp2 = .11. Mean p-inhibitory failures following placebo and 0.65 g/kg alcohol are presented in Figure 3. The figure shows that the interaction is due to a greater increase in p-inhibitory failures in response to alcohol compared to placebo in the alcohol go condition than in the neutral go condition. This was confirmed by paired t tests of dose effects conducted separately within each condition. Compared to placebo, p-inhibitory failures were significantly increased following 0.65 g/kg alcohol in the alcohol go condition, t(19) = 4.6, p < .001, d = 1.04, but not in the neutral go condition (p = .16). We did not conduct an ANCOVA for this analysis, as alcohol impairment of p-inhibitory failures interacted with condition to predict drinking days in regression analyses (see below). As such, the covariate did not meet the required assumption of homogeneity of slopes (i.e., the assumption that a covariate must have the same general relation to the dependent measure across all groups/conditions).

Fig 3.

Mean proportion of inhibitory failures following go cues in the alcohol go and neutral go conditions under two alcohol doses: 0.0 g/kg (placebo) and 0.65 g/kg. Capped vertical lines show standard errors of the mean.

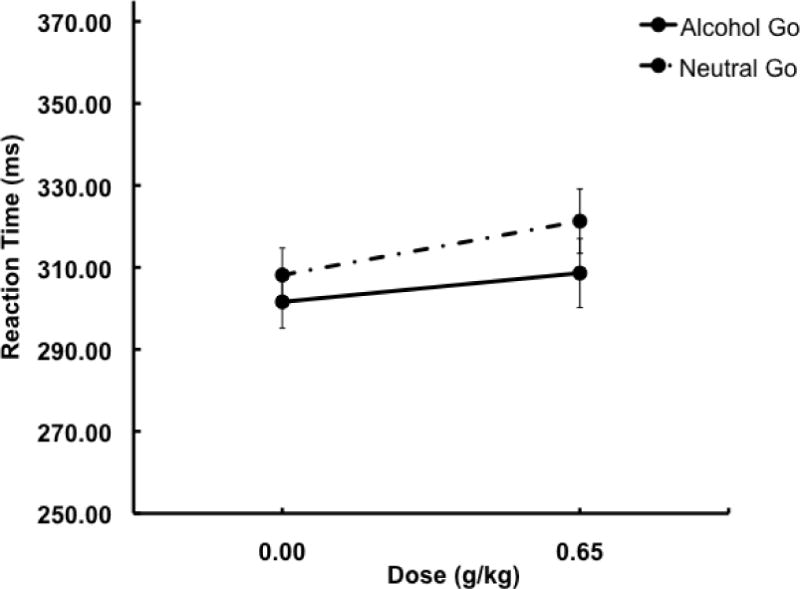

Response Activation

A 2 (condition) × 2 (dose) ANOVA of response RT showed a main effect of dose, F(1, 38) = 10.4, p = .003, ηp2 = .22, but no main effect or interaction involving condition (ps > .33). Mean response RTs are presented in Figure 4. The figure shows the main effect of dose is due to overall slower RT following alcohol compared to placebo in both conditions.

Fig 4.

Mean RT following go cues in the alcohol go and neutral go conditions under two alcohol doses: 0.0 g/kg (placebo) and 0.65 g/kg. Capped vertical lines show standard errors of the mean.

Response inhibition and alcohol consumption

Separate hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to test the hypothesis that individual differences in inhibitory failures would be associated with self-reported measures of alcohol consumption (i.e., drinking days, binge days, and total drinks), and that this effect would be more pronounced in the alcohol go condition. For each regression model, inhibitory failures were entered in Step 1 to test for an association between response inhibition and drinking measures across conditions. Condition was entered in Step 2, and the condition × inhibitory failures interaction term was entered in Step 3. The interaction tested whether the relation between response inhibition and alcohol consumption differed by cue condition.

Results from the regression analyses predicting drinking habits from inhibitory failures during sober baseline ABBA performance (Part 1) are presented in Table 2. Mean inhibitory failures for the sample were positively skewed, and so the square root transformation was entered in these analyses. The table shows a main effect of inhibitory failures in the model predicting drinking days, indicating that greater inhibitory failures were associated with greater number of drinking days across cue conditions. No significant effects were observed in the models predicting binge days or total drinks.

Table 2.

Regresssion models predicting alcohol consumption measures from inhibitory failures on the ABBA task during sober baseline performance (Part 1)

| Alcohol consumption measure | Beta | ΔR2 | ΔF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drinking days | ||||

| Step 1 | P-Failures | 0.36 | 0.13 | 5.82* |

| Step 2 | Condition | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.29 |

| Step 3 | P-Failures*Condition | 0.57 | 0.02 | 0.81 |

| Binge days | ||||

| Step 1 | P-Failures | 0.24 | 0.06 | 2.39 |

| Step 2 | Condition | 0.20 | 0.04 | 1.44 |

| Step 3 | P-Failures*Condition | 0.93 | 0.05 | 2.08 |

| Total drinks | ||||

| Step 1 | P-Failures | 0.24 | 0.06 | 2.32 |

| Step 2 | Condition | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Step 3 | P-Failures*Condition | 0.71 | 0.03 | 1.15 |

Note. P-Failures = the proportion of inhibitory failures (square root transformation).

indicates a significance value of p < .05.

Results from hierarchical regression models testing the relationship between alcohol impairment of inhibitory control (Part 2) and self-reported alcohol consumption are presented in Table 3. Alcohol impairment scores were calculated by subtracting inhibitory failures in the placebo session from inhibitory failures in the alcohol session, such that greater values indicated greater alcohol-induced impairment of inhibitory control. These alcohol impairment scores were then entered into the hierarchical regression analyses described above. Table 3 shows a significant condition × inhibitory failures interaction in the model predicting drinking days. This interaction was probed with bivariate correlational analyses of inhibitory failures and drinking days conducted separately for each condition. Results showed a significant association between greater alcohol impairment of inhibitory failures and greater number of drinking days in the alcohol go condition (r=0.47, p=0.038), but not in the neutral go condition (p=0.27). No significant effects were observed in the models predicting binge days or total drinks.

Table 3.

Regresssion models predicting alcohol consumption measures from alcohol impairment of inhibitory failures on the ABBA task (Part 2)

| Alcohol consumption measure | Beta | ΔR2 | ΔF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drinking Days | ||||

| Step 1 | P-Failures (impairment) | 0.18 | 0.03 | 1.31 |

| Step 2 | Condition | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.82 |

| Step 3 | P-Failures*Condition | 1.31 | 0.14 | 6.04* |

| Binge Days | ||||

| Step 1 | P-Failures (impairment) | 0.19 | 0.03 | 1.35 |

| Step 2 | Condition | 0.22 | 0.04 | 1.73 |

| Step 3 | P-Failures*Condition | −0.32 | 0.01 | 0.31 |

| Total Drinks | ||||

| Step 1 | P-Failures (impairment) | 0.21 | 0.04 | 1.71 |

| Step 2 | Condition | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| Step 3 | P-Failures*Condition | −0.19 | 0.00 | 0.10 |

Note. P-Failures (impairment) = inhibitory failures following placebo subtracted from inhibitory failures following 0.65 g/kg alcohol.

indicates a significance value of p < .05.

Discussion

This study examined the degree to which alcohol images disrupted inhibitory control on the ABBA task in both sober and intoxicated drinkers. In Part 1, participants performed the task in a sober state in order to replicate our previous findings with this task (Weafer & Fillmore, 2012). In Part 2, participants performed the task following placebo and 0.65 g/kg alcohol in order to examine the degree to which alcohol impairment of inhibitory control was potentiated in the context of alcohol-related compared to neutral cues. We then conducted regression analyses to determine if task performance was related to typical drinking habits. Results from Part 1 replicated our previous findings, again showing greater disinhibition following alcohol-related compared to neutral cues in sober drinkers. Moreover, results from Part 2 showed that alcohol-related cues exacerbated alcohol impairment of inhibitory control as evidenced by more pronounced alcohol-induced disinhibition following alcohol cues compared to neutral cues. Finally, regression analyses showed that in sober drinkers, greater disinhibition in both cue conditions predicted greater number of drinking days over the past 90 days. By contrast, the association between alcohol-induced disinhibition and greater number of drinking days was observed following alcohol cues only.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that alcohol-induced disinhibition is exacerbated in the context of alcohol-related images. This finding could have potentially important implications for understanding factors contributing to excessive, undercontrolled alcohol consumption. Alcohol’s impairing effects on inhibitory control are well documented (Fillmore & Weafer, 2013), and previous studies have demonstrated associations between greater sensitivity to alcohol impairment of inhibitory control and heavy drinking (Gan et al., in press; Marczinski et al., 2007; Weafer & Fillmore, 2008). Together, these findings suggest that acute alcohol-induced disinhibition might directly influence on-going consumption by reducing an individual’s ability to stop or control drinking (Fillmore, 2003). It is important to note that these prior studies all assessed inhibitory control following neutral stimuli (e.g., geometric shapes). To the extent that the magnitude of alcohol-induced disinhibition is exacerbated in the context of alcohol-related cues, as indicated by the current findings, such disinhibition might result in greater impairment of control over drinking within real-world drinking contexts. That is, the additive effect of disrupted control mechanisms via both alcohol-cues in the environment and the pharmacological effects of the drug could serve to severely compromise an individual’s control over ongoing alcohol consumption once a drinking episode is initiated.

The current findings replicated previous findings from our lab and others (Fleming & Bartholow, 2013; Kreusch et al., 2013; Weafer & Fillmore, 2012) showing that, as expected, alcohol-related images disrupt inhibitory control in sober drinkers. Importantly, studies are beginning to address the extent to which this finding generalizes to other drugs of abuse. For instance, Pike, Stoops, Fillmore, and Rush (2013) modified the ABBA task by replacing alcohol-related with cocaine-related images, and tested the degree to which these images disrupted inhibitory control in cocaine users. Results showed greater disinhibition following cocaine images relative to neutral images, suggesting that cue-induced disinhibition is not specific to alcohol-related cues. Together, these findings suggest that drug and alcohol-related cues disrupt inhibitory mechanisms necessary to refrain from initiating drinking or drug-taking episodes. This is likely an important mechanism through which such cues serve to increase relapse in individuals attempting to abstain. That is, in addition to increasing desire for drugs or alcohol (i.e., craving), drug-related cues also likely disrupt an individual’s ability to control drug-seeking behavior in response to such cue-induced craving.

These findings provide support for drug addiction models that emphasize the interplay between enhanced salience attribution to drug-related cues and impaired behavioral control in perpetuating ongoing drug abuse (Goldstein & Volkow, 2002; Jentsch & Taylor, 1999). These models propose that the incentive-motivational properties of such cues could directly impair inhibitory mechanisms necessary to control drug-taking urges. Importantly, the attribution of such incentive salience to drug-related cues is thought to result from conditioning processes that occur over a history of heavy drug use (Robinson & Berridge, 2001). As these conditioned cue responses become ‘sensitized’ over continued periods of heavy use, drug-related cues become stronger and stronger motivators of behavior, thus increasing the difficulty in controlling drug use in the face of such cues. Thus, individuals with more extensive experience with heavy alcohol or drug use would be expected to have stronger incentive-motivational responses to drug cues, and perhaps greater cue-induced disinhibition as well. Indeed, the regression analyses in the current study showed that greater alcohol-induced disinhibition following alcohol cues (but not neutral cues) was associated with greater frequency of self-reported alcohol consumption. Although it is not possible to infer causal relations from these analyses, it could be that heavier drinkers have stronger conditioned associations to alcohol-related stimuli, which lead to greater cue-induced urges for consumption, as well as greater cue-induced disruption of inhibitory control. In turn, such enhanced cue-induced disinhibition likely serves as a risk factor for continued alcohol consumption (as discussed above), thus perpetuating the cycle of excessive, binge-like drinking or drug use.

Evidence that alcohol cues disrupt inhibitory control and that the magnitude of disruption is directly related to excessive alcohol use suggests that retraining of inhibitory control in the context of alcohol-related cues could be a potential treatment strategy for lowering alcohol consumption. Initial studies testing this hypothesis have provided promising results. For example, Houben and colleagues conducted two studies in which participants were trained on an alcohol go/no-go task to either inhibit responses to alcohol cues (alcohol no-go) or to respond to alcohol cues (alcohol go) (Houben, Havermans, Nederkoorn, & Jansen, 2012; Houben, Nederkoorn, Wiers, & Jansen, 2011). Although inhibition training did not affect ad lib alcohol consumption immediately following training, those trained to inhibit to alcohol cues consumed significantly less alcohol over the week following the training in both studies. In a similar study, participants were trained to either inhibit or respond to alcohol cues using the stop signal paradigm, in which participants are required to respond to go signals as quickly as possible, but to inhibit their response on the occasional trial when a stop signal (i.e., an auditory tone) is sounded (Jones & Field, 2013). Here, participants trained to inhibit to alcohol pictures drank less alcohol in a taste-test procedure immediately following the training compared to those trained to inhibit to neutral cues, but this effect did not extend to self-reported drinking over the next week. Together, these studies provide promising results regarding the potential effects of inhibition training on lowering alcohol consumption. It will be important for future studies to examine the extent to which such retraining might also reduce cue-induced disinhibition in intoxicated individuals.

There are some limitations to the current study. The between-subjects design could be a potential limitation, as it is possible that the groups differed in baseline levels of inhibitory control. However, we chose this design in order to limit any switching between ‘go’ targets (alcohol vs. neutral) that might serve to reduce the prepotency of the ‘go’ response and thus limit our ability to observe inhibitory failures on this task. Additionally, it is important to note that all participants were recruited from the same population of young adults and randomly assigned to conditions, and the groups did not differ in terms of gender make-up, drinking habits, impulsive personality, or BrACs following alcohol administration. A second potential limitation is the gender make-up of our sample (25% female), which precluded analyses of sex differences in the current study. Our decision to include more men than women was based on logistical difficulties in recruiting moderate to heavy female drinkers who report beer as their most frequently consumed beverage. It will be important for future studies to extend these findings to larger samples comprised of equal numbers of men and women.

In sum, the current study showed that alcohol-related images disrupt inhibitory control in sober and intoxicated drinkers, and that individual differences in cue-induced disinhibition are associated with individual differences in typical drinking habits. These findings have important implications regarding the significance of drug-related cues and disinhibition in promotion of ongoing, excessive alcohol consumption, and suggest directions for future research. For instance, the potential role of cue-induced disinhibition in binge drinking could be assessed more directly in future studies by comparing ABBA task performance in binge and non-binge drinkers, or by examining the degree to which alcohol impairment on this task predicts laboratory measures of alcohol consumption. Additionally, modified versions of the task, such as that developed by Pike et al. (2013) could be used to assess the degree to which alcohol impairment of inhibitory control is potentiated in drug users in the context of other drug-related stimuli. This type of study would provide important information regarding factors influencing the co-administration of alcohol and other drugs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants R01 AA018274 and National Institute on Drug Abuse F32 DA033756. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Adams S, Ataya AF, Attwood AS, Munafo MR. Effects of alcohol on disinhibition towards alcohol-related cues. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;127:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.025. doi: S0376-8716(12)00257-8 [pii] 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork JM, Hommer DW, Grant SJ, Danube C. Impulsivity in abstinent alcohol-dependent patients: relation to control subjects and type 1-/type 2-like traits. Alcohol. 2004;34:133–150. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis RE. The predisposition toward alcohol-related interpersonal aggression in men. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1975;36:1196–1207. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1975.36.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos NA, Komogortsev OV, Turner GM. Ocular imaging of attentional bias among college students: automatic and controlled processing of alcohol-related scenes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:652–659. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR. Recent advances in family studies of alcoholism. Progress in Clinical and Biological Research. 1987;241:47–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawe S, Loxton NJ. The role of impulsivity in the development of substance use and eating disorders. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2004;28:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.03.007. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.03.007S0149763404000363 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Crean J, Richards JB. Effects of d-amphetamine and ethanol on a measure of behavioral inhibition in humans. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2000;114(4):830–837. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.114.4.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty DM, Moeller FG, Steinberg JL, Marsh DM, Hines SE, Bjork JM. Alcohol increases commission error rates for a continuous performance test. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23:1342–1351. doi: 00000374-199908000-00008 [pii] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadardi JS, Cox WM. Alcohol-attentional bias and motivational structure as independent predictors of social drinkers’ alcohol consumption. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;97:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.027. doi: S0376-8716(08)00121-X [pii]10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil J, Sheppard D, Fitzgerald PB, Yucel M, Lubman DI, Bradshaw JL. Addiction, compulsive drug seeking, and the role of frontostriatal mechanisms in regulating inhibitory control. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010;35:248–275. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.03.001. doi: S0149-7634(10)00046-1 [pii]10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Christiansen P, Cole J, Goudie A. Delay discounting and the alcohol Stroop in heavy drinking adolescents. Addiction. 2007;102:579–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01743.x. doi: ADD1743 [pii]10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Cox WM. Attentional bias in addictive behaviors: a review of its development, causes, and consequences. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;97:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.030. doi: S0376-8716(08)00125-7 [pii]10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Munafo MR, Franken IH. A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between attentional bias and subjective craving in substance abuse. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:589–607. doi: 10.1037/a0015843. doi: 2009-09537-005 [pii]10.1037/a0015843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT. Cognitive preoccupation with alcohol and binge drinking in college students: alcohol-induced priming of the motivation to drink. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:325–332. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.15.4.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT. Drug abuse as a problem of impaired control: current approaches and findings. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews. 2003;2:179–197. doi: 10.1177/1534582303257007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT, Marczinski CA, Bowman AM. Acute tolerance to alcohol effects on inhibitory and activational mechanisms of behavioral control. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:663–672. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT, Vogel-Sprott M. Behavioral impairment under alcohol: cognitive and pharmacokinetic factors. Alcohol: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:1476–1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT, Vogel-Sprott M. An alcohol model of impaired inhibitory control and its treatment in humans. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1999;7:49–55. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.7.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT, Weafer J. Behavioral inhibition and addiction. In: MacKillop J, de Wit H, editors. The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Addiction Psychopharmacology. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons Limited; 2013. pp. 135–264. [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Kessler DN, Hussong AM. Risk for alcoholism and classical conditioning to signals for punishment: evidence for a weak behavioral inhibition system? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:293–301. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.103.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming KA, Bartholow BD. Alcohol cues, approach bias, and inhibitory control: Applying a dual process model of addiction to alcohol sensitivity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013 doi: 10.1037/a0031565. doi: 2013-05956-001 [pii]10.1037/a0031565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan G, Guevara A, Marxen M, Neumann M, Junger E, Kobiella A, et al. Alcohol-induced impairment of inhibitory control is linked to attenuated brain responses in right fronto-temporal cortex. Biological Psychiatry. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.12.017. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. Drug addiction and its underlying neurobiological basis: neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of the frontal cortex. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1642–1652. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henges AL, Marczinski CA. Impulsivity and alcohol consumption in young social drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:217–220. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.09.013. doi: S0306-4603(11)00314-5 [pii]10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houben K, Havermans RC, Nederkoorn C, Jansen A. Beer a no-go: learning to stop responding to alcohol cues reduces alcohol intake via reduced affective associations rather than increased response inhibition. Addiction. 2012;107:1280–1287. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houben K, Nederkoorn C, Wiers RW, Jansen A. Resisting temptation: decreasing alcohol-related affect and drinking behavior by training response inhibition. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;116:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.12.011. doi: S0376-8716(11)00032-9 [pii]10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch JD, Taylor JR. Impulsivity resulting from frontostriatal dysfunction in drug abuse: implications for the control of behavior by reward-related stimuli. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;146:373–390. doi: 10.1007/pl00005483. doi: 91460373.213 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A, Field M. The effects of cue-specific inhibition training on alcohol consumption in heavy social drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2013;21(1):8–16. doi: 10.1037/a0030683. doi: 2012-31646-001 [pii]10.1037/a0030683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreusch F, Vilenne A, Quertemont E. Response inhibition toward alcohol-related cues using an alcohol go/no-go task in problem and non-problem drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38:2520–2528. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.04.007. doi: S0306-4603(13)00126-3 [pii]10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence AJ, Luty J, Bogdan NA, Sahakian BJ, Clark L. Impulsivity and response inhibition in alcohol dependence and problem gambling. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;207:163–172. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1645-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marczinski CA, Combs SW, Fillmore MT. Increased sensitivity to the disinhibiting effects of alcohol in binge drinkers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:346–354. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.346. doi: 2007-13102-008 [pii]10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT. Preresponse cues reduce the impairing effects of alcohol on the execution and suppression of responses. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003;11:110–117. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.11.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKim WA. Drugs and behavior: An introduction to behavioral pharmacology. 6. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Miller MA, Fillmore MT. The effect of image complexity on attentional bias towards alcohol-related images in adult drinkers. Addiction. 2010;105:883–890. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02860.x. doi: ADD2860 [pii]10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02860.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvihill LE, Skilling TA, Vogel-Sprott M. Alcohol and the ability to inhibit behavior in men and women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:600–605. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy P, Garavan H. Cognitive predictors of problem drinking and AUDIT scores among college students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;115:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.10.011. doi: S0376-8716(10)00365-0 [pii]10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. NIAAA council approves definition of binge drinking. NIAAA Newsletter. 2004 Winter;3 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nederkoorn C, Baltus M, Guerrieri R, Wiers RW. Heavy drinking is associated with deficient response inhibition in women but not in men. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2009;93:331–336. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.04.015. doi: S0091-3057(09)00137-3 [pii]10.1016/j.pbb.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Wong MM, Martel MM, Jester JM, Puttler LI, Glass JM, et al. Poor response inhibition as a predictor of problem drinking and illicit drug use in adolescents at risk for alcoholism and other substance use disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:468–475. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000199028.76452.a9. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000199028.76452.a9S0890-8567(09)62067-0 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostling EW, Fillmore MT. Tolerance to the impairing effects of alcohol on the inhibition and activation of behavior. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;212:465–473. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1972-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1995;51:768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::AID-JCLP2270510607>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike E, Stoops WW, Fillmore MT, Rush CR. Drug-related stimuli impair inhibitory control in cocaine abusers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;133:768–771. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.08.004. doi: S0376-8716(13)00319-0 [pii]10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Research Reviews. 1993;18:247–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. Incentive-sensitization and addiction. Addiction. 2001;96:103–114. doi: 10.1080/09652140020016996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AK, Duka T. Effects of alcohol on inhibitory processes. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2008;19:284–291. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328308f1b2. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328308f1b200008877-200807000-00002 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio G, Jimenez M, Rodriguez-Jimenez R, Martinez I, Avila C, Ferre F, et al. The role of behavioral impulsivity in the development of alcohol dependence: a 4-year follow-up study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:1681–1687. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00746.x. doi: ACER746 [pii]10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer ML, Vinokur A, van Rooijen L. A self-administered Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST) Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1975;36:117–126. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1975.36.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma D, Albery IP, Cook C. Selective attentional bias to alcohol related stimuli in problem drinkers and non-problem drinkers. Addiction. 2001;96:285–295. doi: 10.1080/09652140020021026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Trull TJ. Personality and disinhibitory psychopathology: alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:92–102. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.103.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biochemical methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Tibboel H, De Houwer J, Field M. Reduced attentional blink for alcohol-related stimuli in heavy social drinkers. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2010;24:1349–1356. doi: 10.1177/0269881109106977. doi: 0269881109106977 [pii]10.1177/0269881109106977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townshend JM, Duka T. Attentional bias associated with alcohol cues: differences between heavy and occasional social drinkers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;157:67–74. doi: 10.1007/s002130100764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson PE, Watson ID, Batt RD. Prediction of blood alcohol concentrations in human subjects. Updating the Widmark Equation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1981;42:547–556. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1981.42.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weafer J, Fillmore MT. Individual differences in acute alcohol impairment of inhibitory control predict ad libitum alcohol consumption. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;201:315–324. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1284-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weafer J, Fillmore MT. Alcohol-related stimuli reduce inhibitory control of behavior in drinkers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;222:489–498. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2667-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weafer J, Fillmore MT. Acute alcohol effects on attentional bias in heavy and moderate drinkers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:32–41. doi: 10.1037/a0028991. doi: 2012-16652-001 [pii]10.1037/a0028991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]