Abstract

Importance

Maternal immunization with tetanus toxoid and reduced diphtheria toxoid acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine could prevent infant pertussis. The effect of vaccine-induced maternal antibodies on infant responses to diphtheria and tetanus toxoids acellular pertussis (DTaP) immunization is unknown.

Objective

To evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of Tdap immunization during pregnancy and its effect on infant responses to DTaP.

Design, Setting and Participants

Phase I, randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted in private (Houston) and academic (Durham, Seattle) obstetric practices from 2008 to 2012. Forty eight healthy 18–45 year-old pregnant women received Tdap (n=33) or placebo (n=15) at 30–32 weeks’ gestation with cross-over Tdap immunization postpartum.

Interventions

Tdap vaccination at 30–32 weeks’ gestation or post-partum.

Outcome Measures

Primary: Maternal and infant adverse events, pertussis illness and infant growth and development (Bayley-III screening test) until 13 months of age. Secondary: Antibody concentrations in pregnant women before and 4 weeks after Tdap immunization or placebo, at delivery and 2 months postpartum, and in infants at birth, 2 months, and after the third (7 months) and fourth (13 months) doses of DTaP.

Results

All participants delivered healthy newborns. No Tdap-associated serious adverse events occurred in women or infants. Injection site reactions after Tdap immunization were reported in 78.8% (95% CI: 61.1%, 91.0%) and 80% (CI: 51.9%, 95.7%) pregnant and postpartum women, respectively. Injection site pain was the predominant symptom. Systemic symptoms were reported in 36.4% (CI: 20.4%, 54.9%) and 73.3% (CI: 44.9%, 92.2%) pregnant and postpartum women, respectively. Malaise and myalgia were most common. Growth and development were similar in both infant groups. No cases of pertussis occurred. Significantly higher concentrations of pertussis antibodies were measured at delivery in women who received Tdap during pregnancy and in their infants at birth and at age 2 months when compared to infants of women immunized postpartum. Antibody responses in infants of Tdap recipients during pregnancy were modestly lower after 3 DTaP doses, but not different following the fourth dose.

Conclusions and Relevance

This preliminary safety assessment did not find an increased risk of adverse events among women who received Tdap vaccine at 30–32 weeks’ gestation or their infants. Maternal immunization with Tdap resulted in high concentrations of pertussis antibodies in infants during the first 2 months of life and did not substantially alter infant responses to DTaP. Further research is needed to provide definitive evidence of the safety and efficacy of Tdap vaccination during pregnancy.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, study identifier: NCT00707148. URL: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov

Keywords: Maternal immunization, Pertussis, infants, maternal antibodies, response to active immunization

Background

Pertussis is a highly contagious and potentially fatal vaccine preventable disease that has re-emerged in the United States despite high childhood immunization rates. Infants under 6 months of age are at greatest risk of disease, hospitalization and death, and account for more than 90% of all pertussis associated deaths in the U.S. (1) Infants who are too young to receive the primary diphtheria and tetanus toxoid and acellular pertussis (DTaP) immunization series as recommended at 2, 4, and 6 months of age, depend on passive maternal antibodies for protection against pertussis. However, pregnant women have very low concentrations of pertussis antibodies to transfer to their newborn at the time of delivery. (2, 3, 4)

To protect young infants, tetanus toxoid reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine was first recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2008 for postpartum women and close contacts of infants (5, 6, 7), then in 2011 for previously Tdap unimmunized pregnant women (8), and in 2012 for all pregnant women during every pregnancy, regardless of prior Tdap immunization history. (9)

In this phase I study initiated prior to the ACIP recommendation to immunize pregnant women with Tdap, we evaluated the safety and immunogenicity of Tdap vaccine administered to women in the third trimester of pregnancy and measured the efficiency of placental transfer of maternal pertussis antibodies to the neonate, their persistence during the first 2 months of life, and their potential effect on infant immune responses to DTaP immunizations.

Methods

Study design

This was a phase I, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled clinical trial conducted in 3 National Institutes of Health Vaccine Treatment Evaluation Unit sites in the U.S. (Houston, Durham, Seattle) from October 2008 to May 2012. Healthy pregnant women, 18 to 45 years-old and at low risk for obstetrical complications, were recruited from academic and private obstetric office practices. Women with no underlying chronic medical conditions, a singleton pregnancy and prenatal evaluation that predicted an uncomplicated pregnancy with normal first or second trimester screening test results and detailed anatomic fetal ultrasound at 18–22 weeks’ gestation were invited to participate. Women who had previously received Tdap or any tetanus containing vaccine within the prior 2 years were excluded (complete inclusion/exclusion criteria in Supplement). Race and ethnicity as defined by the participant were reported as required by the sponsor. After written informed consent was obtained, eligible pregnant women were randomized 2:1 to receive Tdap vaccine or a saline placebo injection at 30 through 32 weeks’ gestation. Women who received saline during pregnancy were given Tdap vaccine postpartum prior to hospital discharge and women who received Tdap during pregnancy were given saline postpartum (cross-over vaccine administration to ensure blinding of investigators and participants).

Randomization was stratified by site with random block sizes. Each participant was assigned a unique treatment number that corresponded to their treatment allocation. Only the unblinded vaccine administrator had access to the treatment allocation. An age-matched comparison group of healthy non-pregnant women also received Tdap (open label). These non-pregnant women volunteers recruited from the community at each study site provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. Study visits for pregnant women occurred at the day of antepartum vaccination, 4 weeks after vaccination, at delivery, and at 2 and 4 months postpartum; for non-pregnant women, at enrollment, 4 weeks and 6 months after Tdap immunization; and for infants at birth, 2 months, 7 months and 13 months of age. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board and ethics committee at each study site.

Study vaccines

Licensed Tdap vaccine (Adacel® Sanofi Pasteur, Swiftwater, PA) was administered as a 0.5-mL intramuscular (IM) injection containing 5 Lf tetanus toxoid (TT), 2 Lf diphtheria toxoid (DT), 2.5 μg detoxified pertussis toxin (PT), 5 μg filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA), 3 μg pertactin (PRN), and 5 μg fimbriae types 2 and 3 (FIM) in a sterile liquid suspension adsorbed onto aluminum phosphate in single dose vials. The saline control (Hospira, Inc.) contained 2 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride for injection. Each vial was used for a single IM dose of 0.5 mL. Infants received DTaP vaccine (Pentacel® Sanofi Pasteur, Swiftwater, PA) containing the same antigens as in Adacel® (but in different quantities), plus inactivated poliovirus and Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate (tetanus toxoid conjugate), administered by their pediatricians at 2, 4, 6 and 12 months of age.

Safety assessments

Injection site and systemic reactions were assessed in all women by 30-minute observation and completion of a 7-day symptom diary after each injection. Adverse events (AE) and serious adverse events (SAE) were recorded at each study visit for pregnant women from the day of antepartum vaccination to 4 months postpartum, for non-pregnant women for 6 months after Tdap immunization, and for infants from birth to approximately 13 months of age. Whether an AE was attributable to vaccination was judged by the investigators considering temporality, biologic plausibility, and identification of alternative etiologies for each event. The outcomes of pregnancy were documented for mothers and infants at the time of delivery through review of delivery records. Infant growth (weight, length and fronto-occipital circumference) was assessed at each study visit at 2, 7 and 13 months of age, and development with the Bayley-III Scales of Infant and Toddler Development™ Third Edition Screening Test (PsychCorp™) at the last study visit. Pertussis illness was evaluated in mothers and infants by documenting at each study visit any reported cough lasting more than 2 weeks.

Immunogenicity assessments

Blood samples were obtained from pregnant women prior to and 4 weeks after Tdap or placebo antepartum immunization, at delivery, and 2 months after the postpartum Tdap or placebo immunization; in infants at birth (cord blood), approximately age 2 months (prior to the first dose of DTaP), 7 months (4 weeks after the third dose of DTaP), and 13 months (4 weeks after the fourth dose of DTaP). Non-pregnant women had samples collected prior to and 4 weeks after Tdap immunization.

Antibody assays

Serum antibody assays were performed by Sanofi Pasteur in Swiftwater, PA in a blinded manner. Pertussis IgG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were used to quantify the concentration of antibodies to PT, FHA, PRN, and FIM, expressed in ELISA Units per milliliter (EU/mL). (10) The lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) was 3 EU/mL for FHA and 4 EU/mL for PT, PRN and FIM. Anti-tetanus toxoid antibodies were measured by IgG ELISA using the World Health Organization (WHO) International Standard for Tetanus Immunoglobulin, Human, Lot TE3. The LLOQ of the assay was 0.01 International Units per mL (IU/mL). Anti-diphtheria antibody responses were measured by the ability of the test sera to protect Vero cells from a diphtheria toxin challenge using WHO reference serum. The lower limit of detection was 0.005 IU/mL.

Statistical analysis

This was a phase 1 exploratory study that was not powered to test any specific hypotheses. The primary outcome (safety) measures were the incidence of injection site and systemic reactions recorded 0 to 7 days after each injection, the frequency of vaccine-associated AEs and SAEs, the incidence of pertussis illness captured by surveillance of reported cough lasting more than 2 weeks, infant growth measurements, and Bayley III developmental screening of infants. The secondary outcome (immunogenicity) measures were the concentration of IgG antibodies to the vaccine antigens (PT, PRN, FHA, FIM, TT and DT).

Safety outcome measures were described using frequency, proportion, and 95% two-sided exact confidence intervals (95% CI). All participants receiving at least one injection were included in the safety summaries. Pertussis antibody geometric mean concentration (GMC) and 95% CI were calculated for each time point and study group. Placental transfer of antibodies at delivery (ratio of cord blood/maternal GMC) and antibody decay in infants (ratio of GMC at 2 months/cord blood) were estimated. Spearman Rank Correlation was used to detect monotonically increasing/decreasing associations between concentrations and avoid influence of outlying observations. The GMC of pertussis antibodies after 3 doses of DTaP were correlated to cord blood levels in infants. Results that were less than the LLOQ were assigned one-half of the LLOQ for calculations of GMC and placental transmission. The proportion of participants with tetanus and diphtheria antibody concentrations ≥ 0.1 and ≥ 1.0 IU/mL and their 95% CI were calculated. The primary analysis of immunogenicity included participants who received 2 injections (one vaccine and one saline placebo) and contributed both pre- and post-vaccination blood samples for testing and for which valid results were reported. One mother and 4 infants were excluded from immunogenicity analyses due to errors in administration of immunizations to the infants (3 infants), a missed delivery blood sample (1 infant), and a mother receiving the postpartum injection more than 2 months late.

Frequencies were compared using a 2-sided Fisher’s exact test (2-way comparisons) and the Freeman-Halton extension (3-way comparisons). Two sided t-test was used to compare GMCs between groups. An individual alpha level of 0.05 was applied for assigning statistical significance. No imputation was carried out for missing data. The statistical software used was SAS version 9.3 and R version 2.15.2 (2012-10-26).

Results

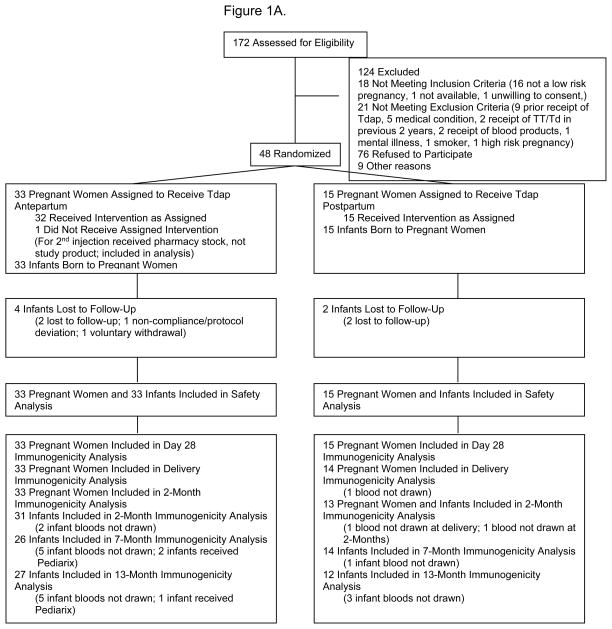

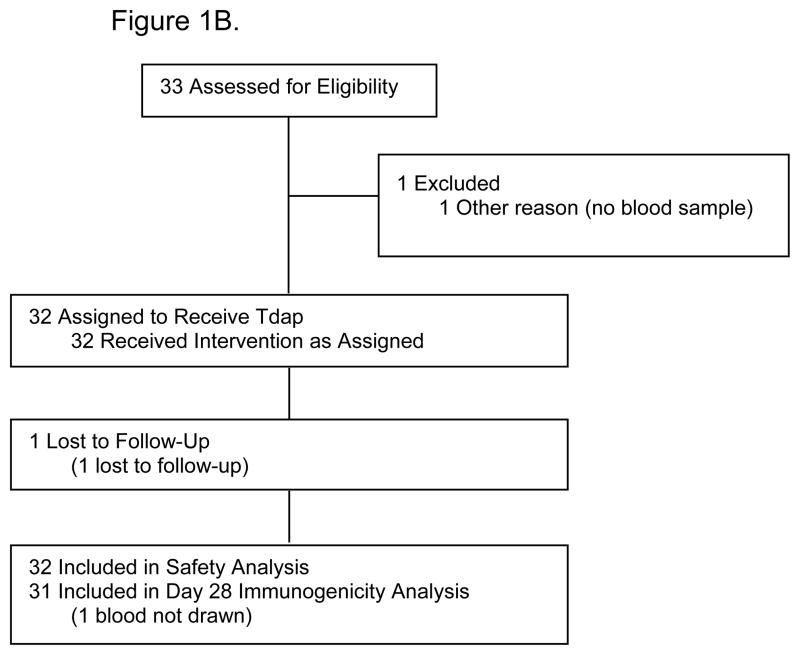

Forty-eight healthy pregnant women and their infants, and 32 healthy non-pregnant women were enrolled. Thirty-three pregnant women received Tdap vaccine and 15 received placebo during pregnancy (Figure 1). The mean interval from Tdap immunization to delivery was 52.1 days (SD, 10.5; 95% CI: 48.4, 55.8) and the median interval was 54 days (min 32, max 68). Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants are described in Table 1.

Figure 1. Parts A–B.

A. Flow diagram for pregnant women study participants.

B. Flow diagram for non-pregnant women study participants.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants.

| Pregnant Women | Non-Pregnant Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tdap Antepartum/Placebo Postpartum (N=33) | Placebo Antepartum/Tdap Postpartum (N=15) | Tdap (N=32) | |

| Ethnicity - n (%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 23 (69.7) | 12 (80.0) | 18 (56.3) |

| Hispanic | 10 (30.3) | 3 (20.0) | 14 (43.8) |

| Race - n (%) | |||

| Asian | 5 (15.2) | 1 (6.7) | 0 |

| Black/African American | 12 (36.4) | 7 (46.7) | 7 (21.9) |

| White | 13 (39.4) | 7 (46.7) | 21 (65.6) |

| Multi-Racial | 1 (3.0) | 0 | 1 (3.1) |

| Other/Unknown | 2 (6.1) | 0 | 3 (9.4) |

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 28.1 (6.7) | 27.8 (6.7) | 28.9 (6.0) |

| Median (min, max) | 30.5 (18, 43) | 27.0 (18, 38) | 28.5 (20, 40) |

| Parity | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.9 (1.1) | 1.8 (0.8) | N/A |

| Median (min, max) | 2 (0,5) | 2 (0, 3) | |

| Mode of Delivery – n (%) | N/A | ||

| Vaginal | 24 (72.7) | 6 (40) | |

| Cesarean Section | 9 (27.3) | 9 (60) | |

| Gestational age at delivery – n (%) | N/A | ||

| ≥ 37 weeks | 30 (90.9) | 14 (93.3) | |

| < 37 weeks1 | 3 (9.1) | 1 (6.7) | |

| Infant birth weight (Kg) | N/A | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.2 (0.5) | 3.5 (0.7) | |

| Median (min, max) | 3.2 (2, 4) | 3.3 (2, 4) | |

| Infant Apgar score at 1 and 5 minutes | N/A | ||

| Mean (SD) | 8 (1.4) and 8.9 (0.2) | 7.9 (1.1) and 8.9 (0.4) | |

| Median (min, max) | 8 (1, 9) and 9 (8, 9) | 8 (5, 9) and 9 (8, 9) | |

| Infant Initial Exam - n (%) | N/A | ||

| Normal | 30 (90.9) | 12 (80) | |

| Abnormal | 3 (9.1) 2 | 3 (20) 3 | |

| Congenital anomalies – n (%) | 1 (3) 4 | 2 (13.3) 5 | N/A |

| Neonatal complications – n (%) | 4 (12.1) 6 | 5 (33.3)7 | N/A |

All infants born at > 35 weeks of gestation

Cephalohematoma (2) and hydrocele (1)

Decreased breath sounds with increased anteroposterior diameter (1), laceration (1), large for gestational age and heart murmur (1)

Bilateral renal pelviectasis

ASD/VSD aymptomatic (1) and cardiomyopathy (1)

Tachypnea (2), jaundice (1), hypoglycemia (1)

Hypoglycemia (1), hypoglycemia and tachypnea (2), tachypnea (1), bilateral pneumothorax (1)

Safety

The proportion of participants reporting any injection site reactions following Tdap immunization was not different between the groups: 78.8% pregnant women, 80.0% postpartum women, and 78.1% non-pregnant women (p=1.0). (Table 2) Following placebo administration, fewer pregnant (20.0%) and postpartum women (18.2%) reported injection site reactions. Pain at the injection site was the most common symptom following Tdap immunization, reported in 75.8%, 73.3% and 78.1% pregnant, postpartum and non-pregnant women, respectively (p= > 0.35); swelling and erythema were infrequent. Most symptoms were mild, and resolved within 72 hours. (Table S1)

Table 2.

Proportion of participants with injection site and systemic reactions after Tdap or saline placebo administration, by study group.

| Tdap Antepartum/Placebo Postpartum (N=33) | Placebo Antepartum/Tdap Postpartum (N=15) | Non-Pregnant Women (N=32) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tdap | Placebo | Placebo | Tdap | Tdap | |||||||

| Symptom | No. (%) | 95% CI | No. (%) | 95% CI | No. (%) | 95% CI | No. (%) | 95% CI | No. (%) | 95% CI | |

| Local Symptoms | Pain at Injection Site1 | 25 (75.8) | (57.7, 88.9) | 5 (15.2) | (5.1, 31.9) | 2 (13.3) | (1.7, 40.5) | 11 (73.3) | (44.9, 92.2) | 25 (78.1) | (60.0, 90.7) |

| Erythema/Redness at Injection Site1 | 3 (9.1) | (1.9, 24.3) | 1 (3.0) | (0.1, 15.8) | 1 (6.7) | (0.2, 31.9) | 0 | (0.0, 21.8) | 2 (6.3) | (0.8, 20.8) | |

| Induration/Swelling at Injection Site1 | 3 (9.1) | (1.9, 24.3) | 0 | (0.0, 10.6) | 0 | (0.0, 21.8) | 2 (13.3) | (1.7, 40.5) | 1 (3.1) | (0.1, 16.2) | |

| Any Injection Site Symptom2 | 26 (78.8) | (61.1, 91.0) | 6 (18.2) | (7.0, 35.5) | 3 (20.0) | (4.3, 48.1) | 12 (80.0) | (51.9, 95.7) | 25 (78.1) | (60.0, 90.7) | |

| Systemic Symptoms | Fever3 (Oral temperature ≥ 100.5) | 1 (3.0)4 | (0.1, 15.8) | 5 (15.2)5 | (5.1, 31.9) | 0 | (0.0, 21.8) | 4 (26.7)5 | (7.8, 55.1) | 3 (9.4)4 | (2.0, 25.0) |

| Headache1 | 11 (33.3) | (18.0, 51.8) | 5 (15.2) | (5.1, 31.9) | 3 (20.0) | (4.3, 48.1) | 7 (46.7) | (21.3, 73.4) | 11 (34.4) | (18.6, 53.2) | |

| Malaise (Feeling Unwell)1 | 4 (12.1) | (3.4, 28.2) | 3 (9.1) | (1.9, 24.3) | 2 (13.3) | (1.7, 40.5) | 3 (20.0) | (4.3, 48.1) | 6 (18.8) | (7.2, 36.4) | |

| Myalgia (Muscle Aches and Pains)1 | 5 (15.2) | (5.1, 31.9) | 3 (9.1) | (1.9, 24.3) | 0 | (0.0, 21.8) | 3 (20.0) | (4.3, 48.1) | 6 (18.8) | (7.2, 36.4) | |

| Any Systemic Symptom6 | 12 (36.4) | (20.4, 54.9) | 9 (27.3) | (13.3, 45.5) | 3 (20.0) | (4.3, 48.1) | 11 (73.3) | (44.9, 92.2) | 17 (53.1) | (34.7, 70.9) | |

| Any Symptom | Any Symptom7 | 26 (78.8) | (61.1, 91.0) | 13 (39.4) | (22.9, 57.9) | 5 (33.3) | (11.8, 61.6) | 14 (93.3) | (68.1, 99.8) | 27 (84.4) | (67.2, 94.7) |

Fisher’s exact p-values > 0.35 comparing individual symptom rates after Tdap doses among Tdap antepartum, Tdap postpartum and non-pregnant women groups.

Fisher’s exact p-values > 1 comparing any injection site symptom rates after Tdap doses among Tdap antepartum, Tdap postpartum and non-pregnant women groups.

Fisher’s exact p-values p=0.044 for fever rates after receipt of Tdap when comparing Tdap antepartum, Tdap postpartum and non-pregnant women groups. This significant difference is attributable to the increased rate in the subjects that received Tdap postpartum (26.7%).

p=0.36 for rates of fever in women who received Tdap antepartum (3.0%) and non-pregnant women (9.4%).

p=0.43 for rates of fever in women who received placebo postpartum (15.2%) and women who received Tdap postpartum (26.7%).

p =0.055 when comparing any systemic symptom rates after Tdap doses among Tdap antepartum, Tdap postpartum and non-pregnant women groups.

p=0.53 for rates of any injection site or systemic symptoms after Tdap doses among Tdap antepartum, Tdap postpartum and non-pregnant women groups.

The proportion of participants with any systemic symptom was 36.4% in women immunized during pregnancy, 73.3% in women receiving Tdap postpartum, and 53.1% in non-pregnant women (p=0.055). (Table 2) The frequencies of headache, myalgia and malaise were not significantly different among the three groups (p= > 0.35), headache being more common than myalgia and malaise. The occurrence of fever after receipt of Tdap was significantly different between the three groups, with pregnant women (3.0%) and non-pregnant women (9.4%) reporting it less frequently than postpartum women (26.7%) (p=0.044). However, the occurrence of fever in women receiving Tdap vaccine postpartum (26.7%) was not different from that of postpartum placebo recipients (15.2%) (p=0.43). There was also no difference in the proportion of participants with fever between recipients of Tdap during pregnancy (3.0%) and non-pregnant women (0.4%) (p=0.36). Most systemic symptoms were mild and self-limited (Table S1).

Serious adverse events were reported by 22 participants, including 7 (21.2%; 95% CI: 8.9%, 38.9%) women who received Tdap during pregnancy and 6 (18.1%; CI: 7.0%, 35.5%) of their infants, 2 (13.3%; CI: 1.7%, 40.5%) women given Tdap postpartum and 6 (40%; CI: 16.3%, 67.7%) of their infants, and 1 (3.1%; CI: <0.1%,16.2%) non-pregnant woman (Table 3). None were judged to be attributable to Tdap vaccine. Non-serious adverse events occurred in 63.6% (CI: 45.1%, 79.6%) women given Tdap during pregnancy, 73.3% (CI: 45.0%, 92.2%) women given Tdap postpartum and 28.1% (CI: 13.7%, 46.7%) non-pregnant women, as well as in 84.8% (CI: 68.1%, 94.9%) infants born to women vaccinated with Tdap antepartum and 93.3% (CI: 68.1%, 99.8%) infants born to Tdap postpartum recipients. All resolved without sequelae.

Table 3.

Serious adverse events (SAE) in study participants, by study group and severity.

| Pregnant Women, Tdap Antepartum (N=33) | Infants of Pregnant Women, Tdap Antepartum (N=33) | Pregnant Women, Tdap Postpartum (N=15) | Infants of Pregnant Women, Tdap Postpartum (N=15) | Non-Pregnant Women, Tdap (N=32) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of participants with SAE (%) | 7 (21.2) | 6 (18.2) | 2 (13.3) | 6 (40.0) | 1 (3.1) | |

| No. of SAE | 7 | 7 | 2 | 10 | 1 | |

| No. with Event by Severity | Mild | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Moderate | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 0 | |

| Severe | 3 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Life-threatening | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| Event Description by Severity | Mild | Atrial septum and ventricular septum defect Cardiomyopathy with biventricular hypertrophy2 |

||||

| Moderate | Hypertension 48 days post-vaccination Preterm contractions 33 days post- vaccination Wound hematoma after C-section |

Gastroenteritis requiring hospitalization Respiratory distress at birth |

Vomiting requiring hospitalization 44 days post-placebo injection | Bronchiolitis requiring hospitalization Respiratory distress/tachypnea3 Anemia3 Hypoglycemia2 Poor feeding due to gastroesophageal reflux2 |

||

| Severe | Pregnancy-induced hypertension 30 days post-vaccination Pancreatitis 3 months after delivery Acute appendicitis 19 days after delivery |

Choking with feeds Requiring prolonged hospitalization Febrile seizures1 Dehydration due to oral herpes simplex virus requiring hospitalization Bronchiolitis |

Preterm labor requiring hospitalization 18 days post-placebo injection | Pelvic fracture (motor vehicle accident) | ||

| Life-Threatening | Fetal distress resulting in C-section 55 days post-vaccination | Fetal distress resulting in C-section Fetal distress resulting in C-section4 Bilateral pneumothoraces4 |

||||

One infant with febrile seizures had two distinct seizure events, both of severe severity.

The mild event of “cardiomyopathy with biventricular hypertrophy” and the two moderate events of “hypoglycemia” and “poor feeding” occurred in the same infant.

The two moderate events “respiratory distress/tachypnea” and “anemia” occurred in the same infant.

The two life-threatening events of “fetal distress” and “bilateral pneumothoraces” occurred in the same infant.

All infants were live born, mostly at term and by vaginal delivery (Table 1). There were no significant differences in the infants’ gestational age, birth weight, Apgar scores, neonatal examination or complications. There were no differences in the infants’ growth and development (Tables S2 and S3), and no cases of pertussis illness occurred in mothers or infants.

Immunogenicity

Antibody responses to Tdap vaccine in pregnant women were not different than those of non-pregnant women and women immunized postpartum (Table 4, Figure S1). Women immunized with Tdap during pregnancy had significantly higher concentrations of antibodies to all vaccine antigens at delivery than women immunized postpartum (Table 4, Figure S2). Infants born to mothers who received Tdap during pregnancy had significantly higher concentrations of pertussis antibodies at birth and at age 2 months (Table 4). The concentration of pertussis antibodies in cord blood was higher than in maternal serum at delivery, with linear correlation between maternal and infant concentrations (Table 5, Figure S3). The ratio of the concentrations of antibodies to Tdap antigens remaining at 2 months in infants is shown in Table 5.

Table 4.

Geometric Mean Concentration (GMC) of antibodies to Tdap vaccine antigens in sera from mothers and infants, and non-pregnant women, by study group and time of sample collection.1,2

| Antigen | Pregnant and Non-Pregnant Women GMC (95% CI) |

Infants GMC (95% CI) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Study Group | Prior to immunization |

4 weeks after antepartum Tdap or placebo |

At Delivery | 2 months after delivery |

At birth (cord blood) |

At 2 months | At 7 months | At 13 months |

|

| ||||||||

| PT (EU/ml) | ||||||||

| Tdap Antepartum | 7.9 (4.9,12.6) | 56.5 (40.0, 79.9) | 51.0* (37.1, 70.1) | 53.1 (39.4, 71.7) | 68.8* (52.1, 90.8) | 20.6* (14.4, 29.6) | 64.9 (53.8, 78.3) | 80.1 (57.3, 112.1) |

| Tdap Postpartum | 9.6 (5.2,17.6) | 10.2 (5.6, 18.7) | 9.1 (4.6, 17.8) | 66.4 (42.2, 104.8) | 14.0 (7.3, 26.9) | 5.3 (3.0, 9.4) | 96.6 (56.7, 164.6) | 83.9 (50.0, 140.8) |

| Non-Pregnant | 17.6 (12.5, 24.7) | 90.9 (69.1, 119.7) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| FHA (EU/ml) | ||||||||

| Tdap Antepartum | 15.1 (8.7, 26.0) | 234.4 (184.1, 298.5) | 184.8* (142.8, 239.1) | 199.8 (153.4, 260.3) | 234.2* (184.6, 297.3) | 99.1* (75.8, 129.6) | 40.6** (30.6, 54.0) | 69.9 (49.5, 98.7) |

| Tdap Postpartum | 23.2 (11.9, 45.3) | 23.6 (13.1, 42.5) | 21.9 (10.9, 44.1) | 270.9 (162.6, 451.3) | 25.1 (10.5, 60.3) | 6.6 (2.8, 15.5) | 78.6 (52.9, 116.7) | 108.9 (78.3, 151.5) |

| Non-Pregnant | 30.1 (18.7, 48.4) | 285.6 (238.0, 342.8) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| PRN (EU/ml) | ||||||||

| Tdap Antepartum | 8.7 (5.7, 13.1) | 205.0 (117.1, 359.1) | 184.5* (110.2, 308.8) | 158.8 (93.5, 269.8) | 219.0* (134.4, 357.0) | 71.1* (42.4, 119.1) | 72.3 (48.7, 107.4) | 203.3 (121.5, 340.1) |

| Tdap Postpartum | 13.2 (5.8, 30.1) | 13.0 (5.7, 29.6) | 12.2 (5.2, 28.4) | 210.1 (80.3, 549.6) | 14.4 (5.4, 38.4) | 5.2 (2.4,11.5) | 77.9 (38.9, 152.6) | 115.2 (54.8, 242.1) |

| Non-Pregnant | 15.4 (11.0, 21.4) | 348.7 (209.1, 581.6) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| FIM 2,3 (EU/ml) | ||||||||

| Tdap Antepartum | 27.2 (14.0, 52.6) | 1533.2 (897.6, 2619.0) | 1485.7* (979.9, 2252.6) | 1274.8 (820.2, 1981.5) | 1867.0* (1211.7, 2876.8) | 510.4* (305.6, 852.3) | 110.8 (83.2, 147.6) | 227.4 (136.4, 379.1) |

| Tdap Postpartum | 36.4 (18.1, 73.1) | 38.2 (19.3, 75.6) | 34.9 (16.3, 74.8) | 2910.2 (1526.4, 5548.5) | 51.8 (22.8, 118.0) | 12.0 (4.9, 29.4) | 186.5 (106.3, 327.2) | 358.8 (151.1, 851.8) |

| Non-Pregnant | 36.8 (21.2, 63.9) | 1785.1 (1222.5, 2606.6) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Tetanus (IU/ml) | ||||||||

| Tdap Antepartum | 2.0 (1.4, 2.8) | 15.3 (10.9, 21.4) | 12.2* (9.0, 16.5) | 12.2 (9.4, 15.9) | 16.5* (12.6, 21.7) | 4.5* (3.4, 5.8) | 1.9 (1.4, 2.5) | 6.8** (4.7, 9.9) |

| Tdap Postpartum | 1.7 (1.2, 2.3) | 1.6 (1.2, 2.2) | 1.5 (1.1, 2.1) | 18.5 (11.7, 29.4) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.6) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.1) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.2) | 2.7 (1.5, 4.8) |

| Non-Pregnant | 2.4 (1.8, 3.3) | 18.4 (13.0, 26.2) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Diphtheria (IU/ml) | ||||||||

| Tdap Antepartum | 0.6 (0.3, 1.1) | 8.3 (5.0, 13.8) | 7.5* (4.6, 12.2) | 6.5 (3.6, 11.6) | 9.4* (5.7, 15.4) | 2.6* (1.6, 4.3) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.9) | 5.3 (3.1, 8.9) |

| Tdap Postpartum | 0.5 (0.2, 1.0) | 0.5 (0.2, 1.0) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.9) | 7.2 (4.1, 12.7) | 0.5 (0.2, 1.2) | 0.1 (0.1, 0.3) | 1.1 (0.6, 2.0) | 7.7 (3.0, 19.4 |

| Non-Pregnant | 0.7 (0.4, 1,2) | 4.6 (2.6, 8.0) | ||||||

Pertussis vaccine antigens: PT = Pertussis Toxin, FHA = Filamentous Hemaglutinin, PRN = Pertactin, Fim 2,3 = Fimbriae 2, 3

See Flow Diagrams for number of participants (N) with immunogenicity data at each time point.

p <0.001 Tdap antepartum vs. Tdap postpartum groups

p <0.01 Tdap antepartum vs. Tdap postpartum groups

Table 5.

Transplacental transfer of antibodies (infant cord blood : maternal antibody ratio) and antibody concentrations in infants at 2 months of age compared to concentrations at birth (infant 2 month : cord blood ratio).

| Tdap Antepartum/ Placebo Postpartum (N=31) | Placebo Antepartum/ Tdap Postpartum (N=14) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine antigen | Infant cord blood : Maternal antibody at delivery ratio (95% CI) | Infant 2 month : Cord blood antibody ratio (95% CI) | Infant cord blood : Maternal antibody at delivery ratio (95% CI) | Infant 2 month : Cord blood antibody ratio (95% CI) |

| Pertussis Toxin | 1.23 (1.03 – 1.47) | 0.34 (0.29, 0.41)1 | 1.54 (1.15 – 2.05) | 0.40 (0.29, 0.56)2 |

| Filamentous Hemagglutinin | 1.27 (1.13 – 1.42) | 0.42 (0.36, 0.49) | 1.15 (0.74 – 1.76) | 0.32 (0.19, 0.53)3 |

| Pertactin | 1.19 (0.93 – 1.52) | 0.31 (0.25, 0.39) | 1.19 (0.98 – 1.44) | 0.42 (0.29, 0.60)2 |

| Fimbriae 2 and 3 | 1.26 (1.02 – 1.55) | 0.26 (0.20, 0.32) | 1.49 (1.27 – 1.73) | 0.25 (0.19, 0.33)2 |

| Tetanus | 1.36 (1.14 – 1.62) | 0.27 (0.22, 0.31)4 | 1.19 (1.02 – 1.40) | 0.38 (0.26, 0.57)3,4 |

| Diphtheria | 1.26 (0.91 – 1.75) | 0.28 (0.22, 0.36) | 1.28 (0.91 – 1.79) | 0.28 (0.22, 0.36)3 |

n=29

n=13

n=12

p=0.042 Tdap antepartum vs. Tdap postpartum groups. Otherwise, no statistically significant differences were observed when comparing infant cord blood:maternal antibody at delivery ratios or Infant 2 month:Cord blood antibody rations between the groups.

At 7 months of age, after receipt of 3 doses of DTaP, infants of women who received Tdap during pregnancy achieved equivalent concentrations of antibodies to PRN, lower concentrations to PT and FIM (32.8% and 40.6% lower, respectively, but not statistically significant), and significantly lower concentrations to FHA (48.3% lower) compared to infants whose mothers received placebo during pregnancy (Table 4). However, at 13 months of age, one month after the fourth dose of DTaP, the concentrations of pertussis antibodies were comparable in the 2 infant groups. (Table 4) Among infants born to women immunized with Tdap during pregnancy, no correlation was observed between cord antibody levels and antibody concentrations achieved after the third DTaP immunization. Among infants of women receiving Tdap postpartum, infants with higher FHA antibody levels at birth had lower concentrations at 7 months of age (Spearman correlation 0.55, p = 0.042). Although the concentration of diphtheria antibodies after the third DTaP dose was lower (54.5% lower) in infants of mothers who received Tdap during pregnancy, these infants had higher concentrations (31.6% higher) of tetanus antibodies. Tetanus and diphtheria antibody responses and protective levels achieved after the fourth DTaP dose were similar in the two infant groups (Tables 4 and S4).

Discussion

In 2012, the United States experienced the most severe pertussis epidemic in more than half a century with nearly 42,000 reported cases. (11) The highest incidence of pertussis and its associated complications continue to occur among infants. (11, 12) The majority of pertussis-related deaths occur in infants too young to be immunized (age < 2 months) or those incompletely immunized (age < 6 months). (1, 11, 12) In 2008, postpartum Tdap immunization of mothers and all contacts of infants (age < 12 months) was recommended to create a protective “cocoon” and prevent pertussis in this population. (7) However, this strategy proved to be challenging to implement, and maternal postpartum immunization alone was not effective in reducing the burden of infant disease. (13, 14) Newborns are unlikely to have protective levels of pertussis antibodies at birth if their mothers have not received a recent dose of a pertussis-containing vaccine. (2, 3, 4) Evidence of rapid decline of pertussis antibody levels in adults and postpartum women immunized with Tdap, the ongoing burden of infant disease, and the increasing severity of pertussis outbreaks in the U.S. led to the 2012 ACIP recommendation to immunize all pregnant women with Tdap during every pregnancy. (9)

We report for the first time, to our knowledge, in a randomized controlled trial, that Tdap immunization of pregnant women in the third trimester was well tolerated and elicited immune responses similar to non-pregnant women. Among primary outcomes, injection site and systemic reactogenicity rates in pregnant women were not significantly different than those observed among postpartum or non-pregnant women, and no Tdap vaccine-related adverse events or adverse pregnancy outcomes were observed. The safety of Tdap immunization in pregnancy also has been documented through passive surveillance by a CDC Vaccine Adverse Event Report System review and in a 6 year report of the Adacel® vaccine pregnancy registry. (15, 16)

Secondary outcome assessments showed that Tdap administration at 30 through 32 weeks’ gestation resulted in high pertussis antibody concentrations in maternal sera at delivery that persisted 2 months postpartum, potentially providing protection to the mother during pregnancy and in the postpartum period. Our findings suggest that third trimester maternal immunization with Tdap results in efficient placental transfer of pertussis antibodies to the fetus, and higher antibody concentrations in infants’ cord blood than in maternal serum at delivery. (2, 3, 4, 17)

A critical finding from our study was that concentrations of vaccine-induced pertussis antibodies in sera from infants born to mothers immunized with Tdap during pregnancy were significantly higher at birth and at age 2 months than in infants whose mothers were immunized postpartum. This suggests that infant protection could occur during the period of highest risk of pertussis-associated mortality and morbidity. Although serum concentrations of pertussis antibodies that correlate with protection remain uncertain, high concentrations to PT, FHA, PRN and FIM are known to be protective. (18, 19) Considering the accumulating evidence that the protective efficacy of Tdap immunization wanes rapidly, most women of childbearing age are likely to be similar to our study participants in their susceptibility to pertussis. (20, 21)

Importantly, although infants born to mothers immunized with Tdap during pregnancy did manifest lower pertussis antibody concentrations to PT, FHA, and FIM following receipt of the third dose of DTaP vaccine, the reductions were modest and disappeared following receipt of the fourth dose of DTaP, suggesting that priming and memory immune responses remained unaltered. Although the presence of maternal antibodies could result in a decreased response to active immunization in infants (22), maternal pertussis antibodies have not been shown to interfere with immunization with acellular pertussis vaccines in young infants. (4, 23) A recent observational study of 16 Tdap immunized pregnant women also found only modest reductions in infant pertussis antibody levels following the third dose of DTaP vaccine. (24)

Our study has several potential limitations. First, the small number of participants potentially limited the ability to detect the occurrence of rare vaccine related adverse events, which may only be detected in large population based studies. Similarly, the small sample size limited the statistical power to detect differences in antibody responses in infants, particularly after administration of the third dose of DTaP vaccine. However, infant immune responses to the fourth dose of DTaP were robust and consistent with a good anamnestic response. While a larger study might reveal a lower overall response to the primary series of DTaP in infants of women immunized during pregnancy, the biological significance would be uncertain and must be weighed against the potentially life-saving protection provided by significantly higher concentrations of pertussis antibodies in the first two months of life. Second, we did not measure antibody concentrations in infants after the first dose of DTaP, but given the high concentrations present at birth and at 2 months, we would anticipate that high concentrations persisted beyond the second month of life. Finally, this study was not designed to evaluate the efficacy of maternal immunization with Tdap to protect mothers or infants against pertussis disease, but our clinical surveillance did not identify any clinical cases of pertussis in study participants. Large prospective studies are needed to determine the effectiveness of Tdap vaccination during pregnancy in preventing young infant pertussis illness.

Conclusion

Tdap immunization in the third trimester of pregnancy was well tolerated and immunogenic, and infants of immunized women had significantly higher concentrations of antibodies to all vaccine antigens from birth until initiation of immunization with DTaP at age 2 months. Maternal immunization with Tdap did not result in substantial or persistent interference of infant antibody responses to immunization with DTaP. Until further research provides definitive evidence of the safety and efficacy of Tdap immunization during pregnancy, our findings support current ACIP recommendations to immunize pregnant women with Tdap during pregnancy to protect infants against pertussis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Sponsor:

Research Support: Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Contracts N01AI80002C (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX), HHSN272200800004C (Group Health Research Institute, Seattle, WA), and HHSN272200800057C (Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC).

JA Englund was also supported in Seattle by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1RR025014. This sponsor had no role in the design or conduct of the study.

Role of Sponsor:

The National Institutes of Health and the Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases had a supervisory role in the design and conduct of the study; but had no direct role in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00707148.

Partial results of this study were presented by FM Munoz at the Second International Neonatal and Maternal Immunization Meeting in Antalya, Turkey, March 3-5, 2013.

Author Contributions: The primary authors, Flor M. Munoz MD, and Carol J. Baker, MD had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study Concept and Design: Munoz, Baker, Ferreira

Acquisition of Data: Munoz, Bond, Maccato, Pinell, Hammill, Swamy, Walter, Jackson, Englund, Edwards, Healy, Baker

Analysis and Interpretation of Data: Munoz, Baker, Swamy, Jackson, Edwards, Ferreira, Goll

Drafting of the Manuscript: Munoz, Baker

Critical Revision of Manuscript for Important Intellectual Content: All authors

Statistical Analysis: Petrie, Ferreira, Goll from the EMMES Corporation, the contract research organization employed by the study sponsor, contributed to the overall study design, managed the data collection and conducted the statistical analysis.

Administrative, Technical and Material Support: Munoz, Bond, Baker

Study Supervision: Munoz, Baker, Swamy, Walter, Jackson, Englund

Conflict of Interest:

No conflict of interest related to this study was reported by the following authors: Bond, Maccato, Pinell, Hammill, Jackson, C. R. Petrie, J. Ferreira and J. Goll performed this work supported by NIAID-DMID contract (Clinical Research in Infectious Disease (CRID), HHSN272200800013C).

F. Munoz has served as a speaker for Sanofi Pasteur and as consultant for Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), and Novavax. She has also conducted clinical trials sponsored by Hoffmann-LaRoche, GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, and Gilead Sciences.

G. Swamy reports receiving consulting and lecturing fees as well as grant support for vaccine-related studies from GSK, as well as for advisory boards, lectures, and the development of educational presentations. She has received grant funding from GSK specific to influenza vaccine and HPV infection.

E. Walter has served as a consultant and advisor for Merck and as a speaker for Sanofi Pasteur. He has conducted clinical trials sponsored by GSK, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer.

J. Englund has received research support from Novartis, Gilead, Chimerix, and Roche. She was a consultant for GSK in 2012–2013 and served on a GSK DSMB on 2012–13, she also received travel expenses from Abbvie (part of Abbot) in 2013.

M. Edwards serves as consultant for and has received grants from Novartis Vaccines.

C. Healy has conducted trials with grants from Sanofi Pasteur and Novartis, and serves as advisor for Novartis Vaccines..

C. Baker serves as consultant and advisory board member to Novartis Vaccines, and advisory board member for Pfizer Inc.

Additional Contributions:

The authors gratefully acknowledge the women and infants who participated in this study, their obstetric and pediatric providers for contributing to the success of the trial, the physician assistants, nurses, coordinators, pharmacists, and administrative personnel at each of the participating VTEU sites, the hospitals where study participants delivered, the members of the DSMB and local safety monitors, and the team at NIH/DMID and the EMMES Corporation (Gina Simone and Cyrille Amegashie) who supported this trial. We would also like to acknowledge Drs. W. Paul Glezen, MD and Wendy A. Keitel, MD from Baylor College of Medicine and Michael D. Decker, MD, MPH, David P. Greenberg, MD, and David R. Johnson, MD, MPH, from Sanofi Pasteur, for providing scientific guidance and expertise throughout the conduct of the study and manuscript preparation; Marcia A. Rench, BSN, who assisted during the initial protocol design, and Susan Bobbitt, RN, study coordinator at the BCM site. No compensation was received by any individual for assistance in the conduct of this study.

Contributor Information

Flor M. Munoz, Email: florm@bcm.edu.

Nanette H. Bond, Email: nbond@bcm.edu.

Maurizio Maccato, Email: maurizio.maccato@hcahealthcare.com.

Phillip Pinell, Email: phillip.pinell@hcahealthcare.com.

Hunter A. Hammill, Email: hunter.hammill@hcahealthcare.com.

Geeta K. Swamy, Email: geeta.swamy@duke.edu.

Emmanuel B. Walter, Email: chip.walter@duke.edu.

Lisa A. Jackson, Email: Jackson.l@ghc.org.

Janet A. Englund, Email: janet.englund@seattlechildrens.org.

Morven S. Edwards, Email: morvene@bcm.edu.

C. Mary Healy, Email: chealy@bcm.edu.

Carey R. Petrie, Email: cpetrie@emmes.com.

Jennifer Ferreira, Email: jferreira@emmes.com.

Johannes B. Goll, Email: jgoll@emmes.com.

Carol J. Baker, Email: cbaker@bcm.edu.

References

- 1.Vitek CR, Pascual FB, Baughman AL, Murphy TL. Increase in deaths from pertussis among young infants in the United States in the 1990s. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003 Jul;22(7):628–34. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000073266.30728.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Healy CM, Munoz FM, Rench MA, Halasa NB, Edwards KM, Baker CJ. Prevalence of pertussis antibodies in maternal delivery, cord, and infant serum. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:335–40. doi: 10.1086/421033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonik B, Puder KS, Gonik N, Kruger M. Seroprevalence of Bordetella pertussis antibodies in mothers and their newborn infants. Infect Did Obstet Gynecol. 2005;13:59–61. doi: 10.1080/10647440500068289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Savage J, Decker MD, Edwards KM, Sell SH, Karzon DT. Natural history of pertussis antibody in the infant and effect on vaccine response. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:487–92. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.3.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Preventing tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis among adolescents: use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccines, recommendations of the ACIP. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006 Mar 24;55(RR-3):1–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) Preventing tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis among adults: use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccine, recommendations of the ACIP and recommendation of ACIP supported by the HICPAC, for use of Tdap among health care personnel. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006 Dec 15;55(RR-17):1–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Prevention of pertussis, tetanus, and diphtheria among pregnant and post-partum women and their infants, recommendations of the ACIP. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008 May 30;57(RR-4):1–51. Erratum in: MMMWR 2008 Jul 4;57(26):723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in pregnant women and persons who have or anticipate having close contact with an infant aged <12 months – ACIP, 2011. MMWR. 2011 Oct 21;60(41):1424–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in pregnant women – ACIP, 2012. MMWR. 2013 Feb 22;62(7):131–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapasi A, Meade BD, Plikaytis B, et al. Comparative study of different sources of Pertussis Toxin (PT) as coating antigens in IgG anti-PT enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012;19:164–72. doi: 10.1128/CVI.05460-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis surveillance report. http://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/surv-reporting.html. Downloaded June 30, 2013.

- 12.Winter K, Harriman K, Zipprich J, Schechter R, Talarico J, Watt J, Chavez G. California pertussis epidemic, 2010. J Pediatr. 2012 Dec;161(6):1091–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castagnini LA, Healy CM, Rench MA, Wooton SH, Munoz FM, Baker CJ. Impact of maternal postpartum tetanus and diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis immunization on infant pertussis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(1):78–84. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halperin BA, Morris A, Mackinnon-Cameron D, et al. Kinetics of the antibody response to tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccine in women of childbearing age and post-partum women. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Nov;53(9):885–92. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheteyeva YA, Moro PL, Tepper NK, et al. Adverse event reports after tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccines in pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:59, e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang M, Khromava A, Mahmood A, Dickinson N. Pregnant women receiving tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine: 6 years of Adacel vaccine pregnancy registry data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf; Presented at the 27th International Congress on Pharmacoepidemiology and Therapeutic Management; Chicago Il. 2011. pp. S1–364. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gall SA, Myers J, Pichichero M. Maternal immunization with tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis vaccine: effect on maternal and neonatal serum antibodies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:334, e.1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taranger J, Trollfors B, Lagergard T, et al. Correlation between pertussis toxin IgG antibodies in post-vaccination sera and subsequent protection against pertussis. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1010–1013. doi: 10.1086/315318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heininger U, Riffelmann M, Bar G, Rudin C, Von Konig CH. The protective role of maternally derived antibodies against Bordetella pertussis in young infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(6):695–8. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318288b610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein NP, Bartlett J, Rowhani-Rhabar A, Fireman B, Baxter R. Waning protection after fifth dose of acellular pertussis vaccine in children. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1012–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klein NP, Bartlett J, Fireman B, Rowhani-Rahbar Al, Baxter R. Comparative effectiveness of acellular versus whole-cell pertussis vaccines in teenagers. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1716–22. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glezen WP. Effect of maternal antibodies on the infant immune response. Vaccine. 2003;21:3389–92. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00339-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Englund JA, Anderson EI, Reed GF, et al. The effect of maternal antibody on the serological response and the incidence of adverse reactions after primary immunization with acellular and whole cell pertussis vaccines combined with diphtheria and tetanus toxoids. Pediatrics. 1995;96:580–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hardy-Fairbanks AJ, Pan SJ, Decker MD, et al. Immune responses in infants whose mothers received Tdap during pregnancy. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(11):1257–60. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182a09b6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.