Abstract

Nontyphoidal salmonellae, particularly Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, are a major cause of invasive disease in Africa, affecting mainly young children and HIV-infected individuals. Glycoconjugate vaccines provide a safe and reliable strategy against invasive polysaccharide-encapsulated pathogens, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a target of protective immune responses. With the aim of designing an effective vaccine against S. Typhimurium, we have synthesized different glycoconjugates, by linking O-antigen and core sugars (OAg) of LPS to the nontoxic mutant of diphtheria toxin (CRM197). The OAg-CRM197 conjugates varied in (i) OAg source, with three S. Typhimurium strains used for OAg extraction, producing OAg with differences in structural specificities, (ii) OAg chain length, and (iii) OAg/CRM197 ratio. All glycoconjugates were compared for immunogenicity and ability to induce serum bactericidal activity in mice. In vivo enhancement of bacterial clearance was assessed for a selected S. Typhimurium glycoconjugate by challenge with live Salmonella. We found that the largest anti-OAg antibody responses were elicited by (i) vaccines synthesized from OAg with the highest glucosylation levels, (ii) OAg composed of mixed- or medium-molecular-weight populations, and (iii) a lower OAg/CRM197 ratio. In addition, we found that bactericidal activity can be influenced by S. Typhimurium OAg strain, most likely as a result of differences in OAg O-acetylation and glucosylation. Finally, we confirmed that mice immunized with the selected OAg-conjugate were protected against S. Typhimurium colonization of the spleen and liver. In conclusion, our findings indicate that differences in the design of OAg-based glycoconjugate vaccines against invasive African S. Typhimurium can have profound effects on immunogenicity and therefore optimal vaccine design requires careful consideration.

INTRODUCTION

Salmonella enterica serovars Typhimurium and Enteritidis generally cause mild gastroenteritis in developed countries but are a predominant cause of invasive bloodstream infection in sub-Saharan Africa, especially among young children and HIV-infected individuals (1, 2). The case-fatality rate of invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella (iNTS) disease, mainly caused by serovars Typhimurium and Enteritidis, is ca. 20%, and the effectiveness of antibiotic treatment is impaired by a growing frequency of multidrug resistance. Currently, there are no licensed vaccines against iNTS disease, and efforts are ongoing to identify protective antigens and best strategies for vaccine development.

Although salmonellae are facultative intracellular bacteria, they are vulnerable to serum immunoglobulins which can mediate bacteriolysis and osponophagocytosis (3, 4). Previous work from Malawi has shown that antibodies against S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis develop with age in African children, the timing corresponding with a decline in iNTS cases (3).

Approaches to develop an effective vaccine able to elicit a protective immune response include live oral vaccines, which are logistically easy to administer but have potential problems regarding efficient colonization and reactogenicity (5, 6), or subunit vaccines, which could be protein (7, 8) or polysaccharide based, including glycoconjugate vaccines (9–13). Conjugate vaccines have provided a safe and reliable strategy against invasive polysaccharide-encapsulated pathogens such as Haemophilus influenzae type b, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Neisseria meningitidis (14–16). For NTS, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) has been implicated as a target of the protective immune response (17, 18). LPS is composed of lipid A (endotoxin), attached to the 3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonic acid (KDO) terminus of a highly conserved core region, which is linked to a variable O-antigen chain containing serovar-specific repeating units (19). The O-antigen chain of Salmonella contains a trisaccharide backbone of →2)-d-mannose-(1→4)-l-rhamnose-(1→3)-d-galactose-(1→, which is common for Salmonella groups A, B, and D, with a serovar-specific dideoxyhexose side chain attached to the mannose residue, such as abequose for S. Typhimurium and tyvelose for S. Enteritidis (providing O:4 and O:9 specificities, respectively), and glucose branches. Group B salmonellae, such as S. Typhimurium, can also express the O:5 epitope, resulting from the O-acetylation of the 2-hydroxyl group of the abequose residue (O:4,5) (20). LPS protects bacteria from the environment and from complement (3, 21), which can lead to bacterial killing by membrane attack complex formation. However, the ability of LPS to resist complement deposition can be overcome by the production of specific antibodies against O-antigen (22, 23). The O-antigen chain and core sugar alone (here referred to as OAg) constitute a poor immunogen. In contrast, OAg conjugated to a carrier protein can result in protective immunity against lethal challenge, and anti-OAg antibodies are protective in adoptive transfer experiments (9, 12, 13, 24, 25).

In the present study, we synthesized glycoconjugate vaccines against S. Typhimurium, with OAg linked to the nontoxic mutant of diphtheria toxin, CRM197 (26). OAg was extracted by acetic acid hydrolysis directly from the bacterial pellet, a process that removes the toxic lipid A by cleaving the labile bond between lipid A and the KDO sugar at the end of the core region (27). The KDO was used for covalent linkage of OAg to CRM197 through a conjugation chemistry that does not modify the structure of the polysaccharide chain (28). OAg-CRM197 conjugates varied with regard to (i) OAg source, with use of three Typhimurium strains (D23580, NVGH1792, and LT2) producing OAg with specific structural differences, (ii) OAg molecular weight (MW) distribution, with conjugates containing OAg populations of different chain length, and (iii) OAg/CRM197 ratio. Our objective was to gain insights into optimized NTS vaccine design by comparing the immunogenicity and induced serum bactericidal activity of the different OAg-CRM197 conjugate vaccines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Origin and growth of bacterial strains.

The clinical isolate S. Typhimurium D23580 was obtained from the Malawi-Liverpool-Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Programme, Blantyre, Malawi. D23580 is a representative Malawian isolate belonging to the ST313 sequence type isolated from a case of iNTS disease (29, 30). S. Typhimurium NVGH1792 was obtained from the University of Birmingham (27). S. Typhimurium LT2 and S. Enteritidis CMCC4314 (corresponding to ATCC 4931; this strain was used in control experiments) were obtained from the Novartis Master Culture Collection (NMCC). All Salmonella strains were grown in chemically defined medium, using glycerol as the carbon source. D23580, NVGH1792, and LT2 were fermented in a 7-liter bioreactor (EZ-Control; Applikon) to an optical density (OD) of 35, as previously described (27, 31).

OAg extraction and purification.

OAg was directly extracted from the fermentation broth and purified as previously described (27). Briefly, the growth culture was subjected to 2% acetic acid hydrolysis (3 h at 100°C), and the cell supernatant, containing free OAg, was collected after centrifugation. Lower-molecular-weight impurities were removed and the cell supernatant was concentrated by tangential flow filtration (TFF), using a Hydrosart 30-kDa membrane. Protein and nucleic acid impurities were coprecipitated in 20 mM citrate buffer at pH 3. Proteins were further removed by ion-exchange chromatography, and nucleic acids by precipitation in 18 mM Na2HPO4, 24% ethanol, and 200 mM CaCl2. OAg was recovered in water by a second TFF 30-kDa step. Purified OAg from the three S. Typhimurium strains were run on a HiPrep Sephacryl S100 HR16/60 column in 50 mM NaH2PO4–150 mM NaCl (pH 7.2) at a 0.5-ml/min flow rate to separate OAg populations of different MWs. Corresponding fractions were pooled and desalted on a HiPrep 26/10 desalting column (53 ml) prepacked with Sephadex G-25 Superfine (GE Healthcare) prior to conjugation.

OAg characterization.

All OAg preparations were characterized using a range of analytical methods (27, 28): (i) phenol sulfuric acid assay for total sugar quantification (32); (ii) micro-BCA for protein quantification (using bovine serum albumin as a reference according to the manufacturer's instructions [Thermo Scientific]); (iii) UV spectroscopy for nucleic acid content (assuming that a nucleic acid concentration of 50 μg/ml gives an OD260 of 1); (iv) chromogenic kinetic LAL (Limulus amebocyte lysate) for endotoxin level (Charles River Endosafe-PTS instrument); (v) size-exclusion high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC-SEC; differential refractive index [dRI] detection) to estimate molecular size distribution of OAg populations; (vi) high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD) for sugar composition analysis; (vii) semicarbazide/HPLC-SEC method for KDO sugar quantification; and (viii) proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) analysis to identify OAg samples and quantify O-acetylation level.

OAg conjugation to CRM197.

S. Typhimurium OAg-CRM197 conjugates were synthesized by adapting the method previously reported for S. Paratyphi OAg (28). Briefly, OAg was derivatized with adipic acid dihydrazide (ADH) by reductive amination of the KDO sugar and linked to the amino groups on the protein after attachment of a second linker, adipic acid bis(N-hydroxysuccinimide) (SIDEA), to ADH. CRM197 was obtained from Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics.

Purification and characterization of OAg-CRM197 conjugates.

Conjugates were purified either by size exclusion chromatography on a 1.6-by-90-cm S-300 HR column eluted at 0.5 ml/min in 50 mM NaH2PO4–150 mM NaCl (pH 7.2) or by using a Phenyl-HP column, loading 500 μg of protein for ml of resin in 50 mM NaH2PO4–3 M NaCl (pH 7.2). The purified conjugate was eluted in water, and the fractions collected were dialyzed against 10 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 7.2).

Purified conjugates were characterized by phenol sulfuric acid assay (32) for determining the total sugar content, micro-BCA for determining the total protein content, and HPLC-SEC for verifying conjugate formation in comparison to free protein and free OAg and to estimate the conjugate MW distribution (28).

Immunogenicity and challenge studies.

Two immunogenicity studies were conducted (i) to compare the immunogenicities of glycoconjugates made with D23580 OAg populations of different MWs and (ii) to compare the immunogenicities of glycoconjugates made with OAg derived from D23580, NVGH1792, and LT2 S. Typhimurium strains. Whole, unconjugated S. Typhimurium LPS used in the first study was obtained from a commercial source (Enzo Life Sciences, catalog no. ALX-581-011-L002). The glycoconjugate dose was quantified in terms of the OAg amount.

In both studies, 5-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. Mice were injected subcutaneously three times, at 2-week intervals, with immunogen (200 μl/dose). Mice were bled, and sera were collected before the first immunization (day 0), on immunization days 14 and 28, and again 2 weeks after the third immunization on day 42. All animal protocols were approved by the local animal ethical committee (approval N. AEC201018) and by the Italian Minister of Health in accordance with Italian law.

A third mouse experiment was performed to evaluate the in vivo efficacy of the selected D23580 conjugate (OAg containing mixed-MW populations). This experiment was performed in observance of licensed procedures under United Kingdom Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. Two groups of six 8- to 10-week-old female C57BL/6N mice, bred in-house at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (33), were vaccinated subcutaneously with either 1 μg of conjugate or saline/dose, as described above. At day 45, mice were challenged intraperitoneally with 104 CFU of D23580 and sacrificed at 24 h postchallenge. The spleens and livers were homogenized in water, and viable bacterial counts were determined by plating on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar.

Serum antibody analysis by ELISA.

Serum IgG levels against both OAg and CRM197 were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (28, 31, 34). Purified OAg from D23580, NVGH1792, or LT2 (5 μg/ml) and CRM197 (2 μg/ml) were used for ELISA plate coating. Mouse sera were diluted 1:200 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). ELISA units were expressed relative to mouse anti-OAg (generated by immunizing mice with heat-killed D23580 [34]) or anti-CRM197 IgG standard serum curves, with the best four-parameter fit determined by a modified Hill plot. One ELISA unit was defined as the reciprocal of the standard serum dilution that gives an absorbance value equal to 1 in the assay. Each mouse serum was tested in triplicate. The data are presented as scatter plots of individual mouse ELISA units, with the geometric mean of each group. The data from the second immunization study are presented as reverse cumulative distribution (RCD) plots, with antibody levels on the horizontal axis (logarithmic scale), and the percentages of mice with an antibody concentration equal to or greater than the level indicated on the vertical axis (range, 0 to 100%) (35).

SBA.

Equal volumes of day 42 mouse serum belonging to the same immunization group were pooled for serum bactericidal assay (SBA) experiments. Sera from mice immunized with NVGH1792 conjugate were also tested individually.

S. Typhimurium was grown in LB medium to log phase (OD = 0.2), diluted 1:30,000 in SBA buffer (50 mM phosphate, 0.041% MgCl2·6H2O, 33 mg/ml CaCl2, 0.5% BSA) to approximately 3 × 103 CFU/ml, and distributed into sterile polystyrene U-bottom 96-well microtiter plates (12.5 μl/well). To each well (final volume of 50 μl [∼620 CFU/ml]), serum samples serially diluted 3-fold (starting from a 1:20 or a 1:100 dilution) were added. Sera were heated at 56°C for 30 min to inactivate endogenous complement. Active baby rabbit complement (BRC; Pel-Freez lot 0405/lot 12521) used at 50% of the final volume was added to each well. The BRC source, lot, and percentage used in the SBA reaction mixture were previously selected for lowest toxicity against S. Typhimurium. To evaluate possible nonspecific inhibitory effects of BRC or mouse serum, bacteria were also incubated with either the same tested sera plus heat-inactivated BRC (HI-BRC), sera alone (no BRC), or SBA buffer and active BRC. Each sample and control was tested in triplicate. A 7-μl reaction mixture from each well was spotted onto LB agar plates at time zero (T0) to assess the initial CFU and at 1.5 h (T90) after incubation at 37°C. LB agar plates were incubated overnight at 37°C, and the resulting CFU were counted the following day. The bactericidal activity was determined as the percent CFU counted in each pooled serum dilution with active or inactive BRC compared to the CFU of the same serum dilutions with no BRC. SBA graphs show the percent bacterial growth as a function of anti-OAg ELISA units detected in each tested serum pool.

Flow cytometry for anti-Salmonella IgG antibodies.

Bacteria were grown overnight in LB medium, diluted to an OD of 0.17, and incubated in 1:200-diluted (PBS, 1% BSA) serum samples (3 × 106 CFU in 50 μl) for 1 h in ice. After a washing step with PBS, the bacteria were incubated with secondary anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 647-labeled antibody (Molecular Probes; 1:400 in PBS–1% BSA) for 1 h in ice. After further washing, the bacteria were resuspended in 4% formaldehyde (130 μl) and then read using a FACSCanto (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer (10,000 events recorded). We used, as negative controls, bacteria incubated with secondary antibody only. Values were obtained by dividing the geometric mean of fluorescent signals of positive bacteria compared to the negative controls.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis of ELISA results was conducted on day 42 samples (with mice receiving 8 μg/dose for the first study and 0.125 μg/dose for the second study). Groups were compared using Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance. Post hoc analysis was performed using the Student-Newman-Keuls test for both anti-OAg and anti-CRM197 antibody units (using α = 0.05). The dose-response relationship in the first study was evaluated by Spearman rank correlation. Statistical evaluation of SBA growth inhibition of different serum/antibody preparations was performed using a Student t test at each serum dilution.

RESULTS

OAg purification and characterization.

S. Typhimurium strains grew well under the fermentation conditions used (doubling times: 1.2 h, D23580; 1.4 h, NVGH1792; and 1.6 h, LT2), reaching high cell densities (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Purification yields were 250 to 400 mg of OAg per liter of fermentation broth according to strain of origin. All purified OAg were found to have protein and nucleic acid contents of <1% (wt/wt) with respect to OAg and endotoxin levels of <0.1 EU/μg of sugar, indicating the complete removal of lipid A (27).

OAg from the three different strains were similar in terms of MW distribution (27). Analysis by HPLC-SEC (dRI) revealed, for all of them, the presence of two main populations with different average molecular masses (indicated in kDa, which is the distribution coefficient in size-exclusion chromatography, indicating the OAg molecular mass, measured as 0.58 and 0.68 on TSK gel 6000-5000 PW columns, 0.5 ml/min, 100 mM NaH2PO4 100 mM NaCl, 5% CH3CN [pH 7.2]).

Sugar composition analysis by HPAEC-PAD and 1H NMR (Table 1) revealed mannose (Man), rhamnose (Rha), and galactose (Gal) in a molar ratio of 1:1:1, as expected, and an abequose (Abe)/Rha molar ratio close to 1 for all of the strains. The glucose (Glc)/Rha molar ratio was similar for LT2 (0.11) and NVGH1792 (0.08) but was much higher for D23580 OAg (0.39).

TABLE 1.

Characterization of OAg populations from different S. Typhimurium strainsa

| Sample | Molar ratio to Rha |

Avg no. of repeating units (Rha to GlcNAc)b | O-acetyl (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Man | Gal | Glc | Abe | |||

| D23580 | ||||||

| Mix | 1.05 | 1.08 | 0.41 | 1.00 | 24.4 (18.4) | 142 |

| HMW | 1.03 | 1.05 | 0.46 | 1.00 | 71.0 | 138 |

| MMW | 1.04 | 1.12 | 0.35 | 0.99 | 25.5 | 145 |

| LT2 | ||||||

| Mix | 1.03 | 1.27 | 0.11 | 1.02 | 29.7 (13.2) | 65 |

| LT2 HMW | 1.05 | 1.08 | 0.06 | 1.03 | 93.6 | 69 |

| LT2 MMW | 1.04 | 1.12 | 0.11 | 1.01 | 32.3 | 61 |

| NVGH1792 | ||||||

| Mix | 1.02 | 1.22 | 0.08 | 1.07 | 36.1 (22.8) | 149 |

| HMW | 1.05 | 1.09 | 0.06 | 1.03 | 87.0 | 152 |

| MMW | 1.04 | 1.13 | 0.09 | 1.04 | 34.7 | 158 |

Rha, Man, Gal, Glc, and GlcNAc were quantified by HPAEC-PAD. Abe/Rha ratios were determined by 1H NMR. The O-acetyl level was calculated using 1H NMR as the molar ratio percentage of O-acetyl groups to Rha. The strains produced two main OAg populations at different average molecular masses that were copurified. The two species were separated by size-exclusion chromatography and fully characterized. The Rha/GlcNAc molar ratio indicates the average number of repeating units per OAg chain.

Values in parentheses indicate the percent molar ratios of the HMW population present in the OAg mix, as calculated by a semicarbazide/KDO assay.

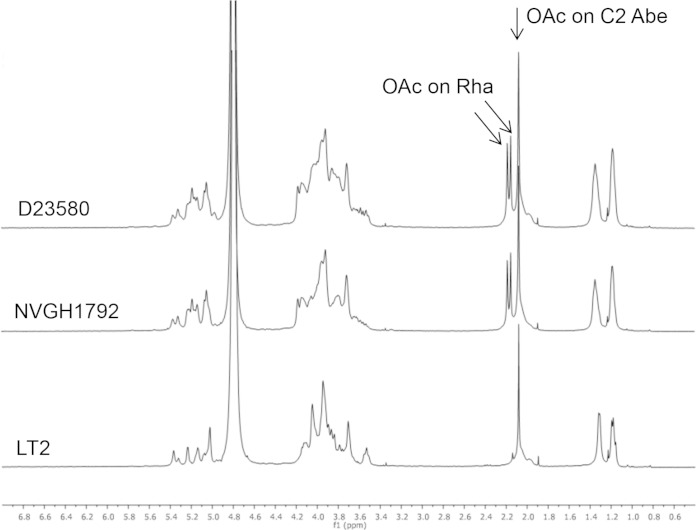

The O-acetyl content (expressed as the percent molar ratio of O-acetyl groups to Rha) was also different according to the OAg source: 142% for D23580, 149% for NVGH1792, and 65% for LT2 OAg. For D23580 and NVGH1792, percentages higher than 100 indicate the presence of O-acetyl groups in more than one position per OAg repeating unit (Table 1). Analyses by 1H NMR (Fig. 1) indicated the presence of O-acetyl groups on C-2 of Abe for OAg from each strain and the additional presence of O-acetyl groups on Rha for D23580 and NVGH1792 OAg (36, 37).

FIG 1.

1H NMR spectra of S. Typhimurium D23580, NVGH1792, and LT2 OAg in D2O, at 500 MHz, and at room temperature, demonstrating the presence of O-acetyl groups on the C-2 of abequose of the OAg repeating unit of each Salmonella strain and the additional presence of O-acetyl groups on rhamnose of the OAg repeating unit of D23580 and NVGH1792. Arrows indicate peaks corresponding to the O-acetyl groups.

For each strain, the two populations at different MWs were separated by size exclusion chromatography and fully characterized (Table 1). Higher-MW (HMW) and lower-molecular-weight (indicated here as the medium-molecular-weight [MMW]) populations were identical in terms of O-acetylation level and sugar composition, differing only in their MWs. The average number of repeating units was calculated based on the molar ratio of Rha (present in each repeating unit) to N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc; present as a unique sugar in the core region). For all OAg, the ratio of KDO to GlcNAc was close to 1, confirming the presence of one KDO unit per OAg chain.

Synthesis and characterization of OAg-CRM197 conjugates.

Acid hydrolysis cleaves the labile linkage between the lipid A and the KDO sugar at the proximal end of the core region, releasing OAg. This sugar has been used to introduce ADH and then SIDEA linkers and to bind OAg to the carrier protein, CRM197, without modifying the OAg sugar chain (28).

Conjugates were prepared using OAg purified from the three different strains, without separating the two populations of different MWs (OAgmix). For D23580 OAg, conjugates were also prepared with the isolated populations of different MWs to investigate the influence of OAg chain length on the immunogenicity of the corresponding conjugate vaccines. All conjugation mixtures were free from residual free CRM197, as shown by SDS-PAGE and HPLC-SEC. The purification of the D23580 MMW OAg conjugate from free polysaccharide was performed by size-exclusion chromatography. For conjugates with mixed HMW and MMW OAg populations, the conjugate overlapped the population of free HMW OAg on the Sephacryl S300 column, so purification of such conjugates was performed by hydrophobic interaction through a Phenyl-HP column, loading the conjugation mixture in 3 M NaCl. Free OAg did not bind to the resin and was removed in the flowthrough. The purified conjugate was eluted in water. Conditions used were optimal for the recovery of the LT2 OAg conjugates (79% conjugate recovery in terms of protein) but not for D23580 and NVGH1792 conjugates (50% conjugate recovery), possibly because of the higher O-acetylation levels of D23580 and NVGH1792 OAg. When purifying D23580 OAgHMW-CRM197, the average size of the conjugate lost in the flowthrough was bigger than in the eluate. The flowthrough population was further purified from free OAg by size-exclusion chromatography and was characterized by a higher OAg/CRM197 ratio than the conjugate retained on the phenyl column (9.2 and 3.1, respectively).

The main characteristics of the conjugates are listed in Table 2. Kd values for all of the conjugates were lower than unconjugated CRM197 (0.72) and both unconjugated HMW (0.58) and MMW (0.68) OAg, indicating that all conjugates are of higher molecular weight compared to their unconjugated component parts.

TABLE 2.

Characterization of OAg-CRM197 conjugates tested in micea

| Conjugate | Molar (wt/wt) OAg/CRM197 ratiob | Concn (μg/ml) |

Kd (SEC) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OAg | CRM197 | |||

| OAgmix-CRM197 (LT2) | 1.56 | 102.4 | 65.7 | 0.48 |

| OAgmix-CRM197 (NVGH1792) | 1.83 | 241.5 | 131.9 | 0.45 |

| OAgmix-CRM197 (D23580) | 1.53 | 34.7 | 22.6 | 0.48 |

| OAgMMW-CRM197 (D23580) | 1.45 (4.2) | 88.9 | 61.4 | 0.49 |

| OAgHMW(9.2)-CRM197 (D23580) | 9.16 (9.9) | 78.8 | 8.6 | 0.42 |

| OAgHMW(3.1)-CRM197 (D23580) | 3.05 (3.3) | 26.2 | 8.6 | 0.51 |

| Unconjugated CRM197 | 0.69 | |||

| Unconjugated HMW OAg | 0.55 | |||

| Unconjugated MMW OAg | 0.66 | |||

The OAg/CRM197 ratio was calculated based on the OAg concentration by phenol sulfuric assay, and the protein concentration was determined by micro-BCA. Kd values were calculated following HPLC-SEC analysis on TSK gel 6000-5000 PW columns (flow rate, 0.5 ml/min; eluent, 100 mM NaH2PO4–100 mM NaCl–5% CH3CN [pH 7.2]) using λ-DNA and NaN3 to determine the void volume and the total volume, respectively. The Kd values were 0.58 and 0.68 for free OAg peaks and 0.72 for free CRM197.

Molar ratios indicated in parentheses were calculated based on the OAg and protein molecular masses (MMW OAg, 20,300 Da; HMW OAg, 54,100 Da [values were estimated considering the number of repeating units, the sugar composition, and the O-acetylation level for each population]; CRM197, 58,400 Da).

Immunogenicity studies.

In the first study (Table 3), eight C57BL/6 mice per group were immunized subcutaneously three times at 2-week intervals with two glycoconjugates containing OAg extracted from D23580 at doses ranging from 0.125 to 8 μg: OAgmix-CRM197, synthesized using a mix of both OAg populations, and OAgMMW-CRM197, produced after selecting the MMW OAg population. Additional groups contained mice immunized with unconjugated OAg, a physical mixture of OAg and CRM197, commercial S. Typhimurium LPS, and saline only.

TABLE 3.

Immunogenicity studies

| Immunization study and groupa | Immunogen | Dose (μg/200 μl) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| OAg | CRM197 | ||

| First | |||

| 1 | OAgMMW-CRM197 | 0.125 | 0.086 |

| 2 | OAgMMW-CRM197 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| 3 | OAgMMW-CRM197 | 2 | 1.4 |

| 4 | OAgMMW-CRM197 | 8 | 5.5 |

| 5 | OAgmix-CRM197 | 0.125 | 0.082 |

| 6 | OAgmix-CRM197 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| 7 | OAgmix-CRM197 | 2 | 1.3 |

| 8 | OAgmix-CRM197 | 8 | 5.2 |

| 9 | OAg + CRM197 | 8 + 8 | 8 |

| 10 | OAg | 8 | |

| 11 | LPS | 8 | |

| 12 | Saline | ||

| Second | |||

| 1 | OAgmix-CRM197 LT2 | 0.125 | 0.08 |

| 2 | OAgmix-CRM197 NVGH1792 | 0.125 | 0.068 |

| 3 | OAgmix-CRM197 D23580 | 0.125 | 0.082 |

| 4 | OAgHMW(3.1)-CRM197 D23580 | 0.125 | 0.041 |

| 5 | OAgHMW(9.2)-CRM197 D23580 | 0.125 | 0.014 |

| 6 | OAgMMW-CRM197 D23580 | 0.125 | 0.086 |

| 7 | OAg NVGH1792 | 0.125 | |

The first immunization study included conjugates with OAg from D23580; the second immunization study included conjugates with OAg from three different S. Typhimurium strains.

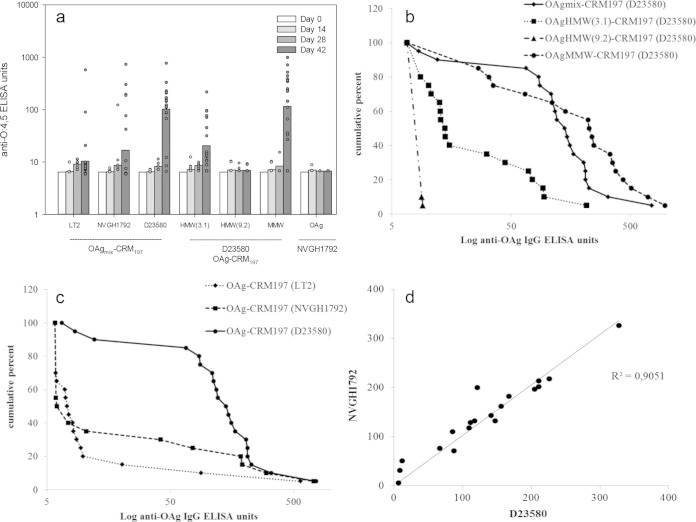

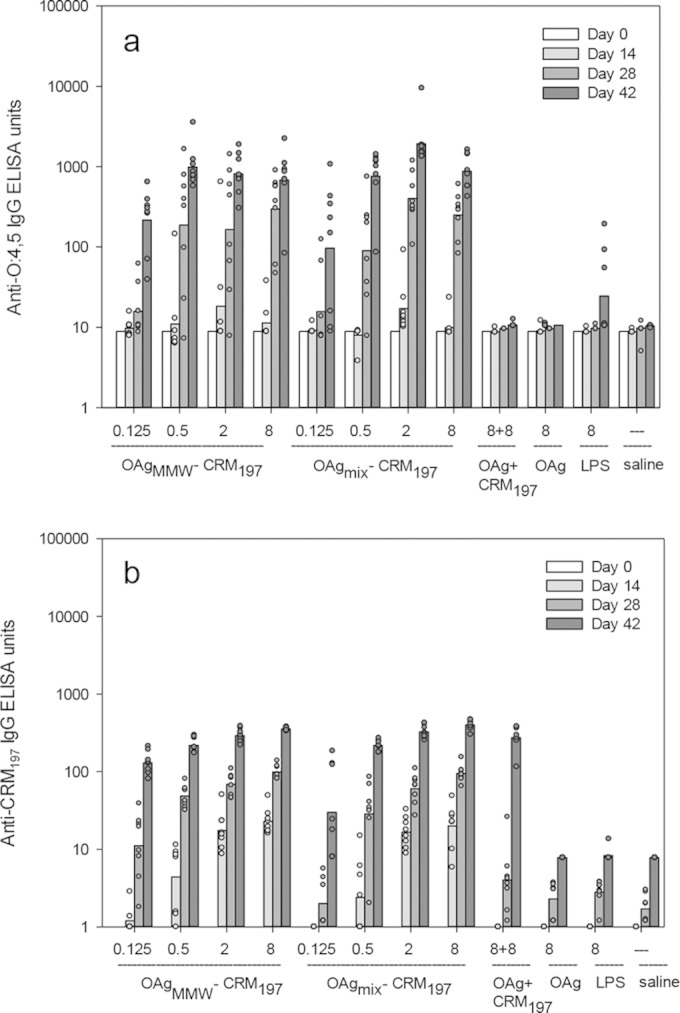

As shown in Fig. 2a, both OAg-CRM197 conjugate formulations generated an antibody dose response (P < 0.001) and were immunogenic at the lowest dose tested (0.125 μg) with significantly higher levels of anti-OAg IgG compared to unconjugated OAg and the OAg and CRM197 physical mixture. No significant difference in anti-OAg titers was found between the two conjugate groups. Unconjugated OAg alone or mixed with CRM197 did not elicit a detectable antibody response (<10 anti-OAg ELISA units) to OAg (Fig. 2a). Also, for anti-CRM197 antibodies, no significant difference was found between the two conjugate groups, and for both groups a dose-response relationship was detected (P < 0.001). As expected, the OAg and CRM197 mixture generated anti-CRM197 antibodies (Fig. 2b).

FIG 2.

First immunization study. Conjugates with OAg from the D23580 strain were evaluated. Anti-OAg IgG (a) and anti-CRM197 IgG (b) ELISA units were detected in the sera of C57BL/6 mice immunized with D23580 OAg-conjugates (OAgMMW-CRM197 and OAgmix-CRM197) and controls (D23580 OAg+CRM197, unconjugated D23580 OAg, S. Typhimurium LPS, and saline). D23580 OAg was used as a coating for the ELISA plates. Mice were immunized three times at 2-week intervals with the indicated doses. Individual animals are represented by the scatter plots; bars represent the group geometric mean. The bar is absent for groups whose geometric mean is below y axis scale.

In the second study (Table 3), 20 mice per group were immunized with glycoconjugates derived from D23580-, NVGH1792-, and LT2-OAg, using a mixture of both OAg size populations for each conjugation, without further purification. The D23580MMW and D23580mix conjugates from the first study were included as internal controls. Two additional D23580 glycoconjugates, produced after isolating the OAg population of higher molecular weight (OAgHMW [not available for the first study]), were included: OAgHMW(3.1)-CRM197 and OAg HMW(9.2)-CRM197, with OAg/CRM197 wt/wt ratios of 3.1 and 9.2, respectively. Unconjugated NVGH1792 OAg was used as a further control. In the present study, the lower suboptimal immunization dose of 0.125 μg was deliberately chosen based on the findings of the first study in order to increase discrimination between responses to the different conjugates. This dose was not selected with the aim of inducing optimal antibody responses, and so there was marked variability in antibody responses within each group and the presence of many nonresponder mice. For this reason, data are also represented as RCD plots (Fig. 3b and c), which allow comparisons of the full distribution of antibody data and display outliers without distortions (35). As shown in Fig. 3a, OAgMMW-CRM197 and OAgmix-CRM197 induced significantly higher anti-OAg IgG responses compared to both OAgHMW-CRM197 formulations (P < 0.001). A similar result was found for the anti-CRM197 IgG responses (data not shown). OAgHMW(9.2)-CRM197 produced anti-OAg titers that were not significantly different from unconjugated OAg (anti-OAg IgG below minimum limit of detection [MLD], at 6 ELISA units). As with the first immunization study, no significant difference in anti-OAg antibodies was found between OAgMMW-CRM197 and OAgmix-CRM197 conjugates (P = 0.9 when conjugates were compared at 0.125 μg/dose). In the RCD representation, the steepness of the plot is a reflection of the spread or variance of values. In the present study, the OAgMMW conjugate produced a curve with a more triangular shape than the OAgmix conjugate, indicating wider variation among individual responses.

FIG 3.

Second immunization study. Conjugates with OAg from three different S. Typhimurium strains were evaluated: D23580 (tested at different OAg MWs and OAg/CRM197 ratios), NVGH1792, and LT2. Note that a suboptimal vaccine dose of 0.125 μg was selected from the first immunization study in order to maximize discrimination between the immunogenicity of the three vaccines. (a) Anti-OAg (D23580) IgG. (b and c) Reverse cumulative distribution (RCD) plots of anti-OAg (D23580) IgG antibody detected at day 42 in C57BL/6 mice immunized with D23580-OAg conjugates (mix, MMW, and HMW) (b) or OAg (mix) conjugates from D23580, LT2, and NVGH1792 strains (c). Mice were immunized three times at 2-week intervals with conjugate vaccine (0.125 μg/dose). ELISAs were performed with D23580-ELISA plate coating agent. (d) Correlation of anti-OAg antibody levels (expressed in units in both axes) in mouse sera (day 42 samples) obtained using either a D23580 (x axis) or an NVGH1792 (y axis) OAg ELISA plate coating agent.

When conjugates obtained with OAg from different strains were compared (Fig. 3c), the highest anti-OAg IgG antibody titers were obtained with D23580 OAgmix-CRM197 conjugate (P < 0.001). The more rectangular curve obtained with this conjugate indicated that a high proportion of mice had antibody levels near the high end of the included range. In contrast, for both NVGH1792 and LT2 OAgmix-CRM197 conjugates, the majority of mice had IgG antibody levels below the MLD (7 ELISA units for this assay), with 12/20 mice of the NVGH1792 group and 8/20 mice of the LT2 group being nonresponders (only 1/20 for D23580). The difference in the responses of the NVGH1792 and LT2 groups was not statistically significant. The D23580 OAgmix-CRM197 conjugate was significantly more immunogenic than the NVGH1792 and LT2 conjugates (P < 0.001), regardless of whether ELISA plates were coated with OAg from D23580 or NVGH1792 (Fig. 3d). When LT2 OAg was used as plate-coating agent, very low ELISA signals were obtained with all immunization groups, with 3/20 mice above the MLD per group at most (no significant differences [data not shown]).

SBA.

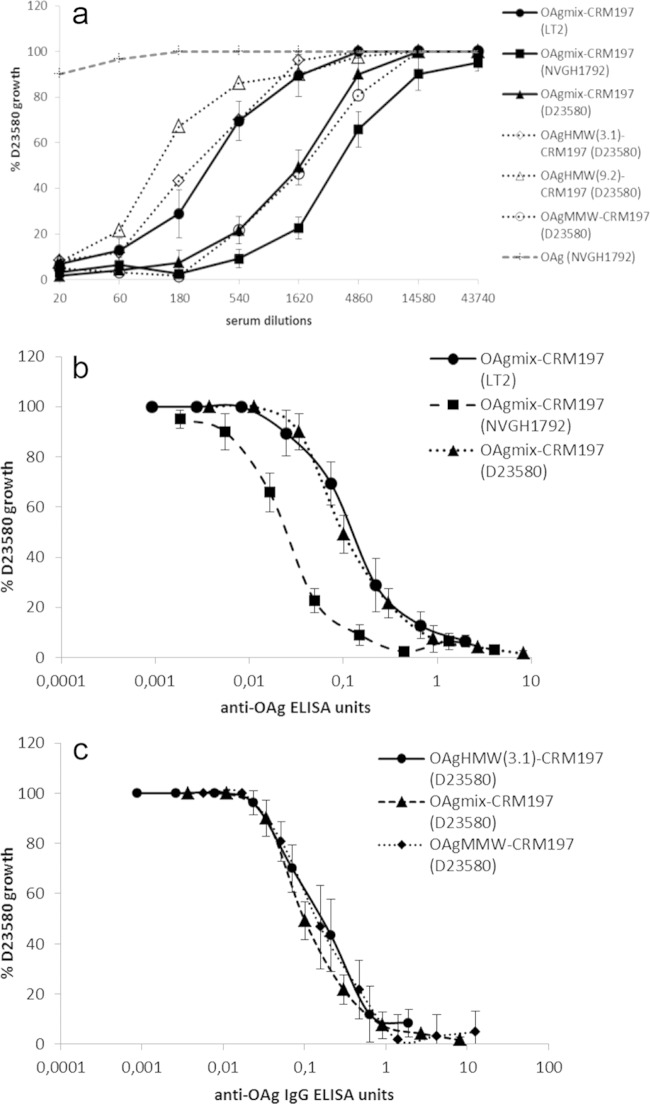

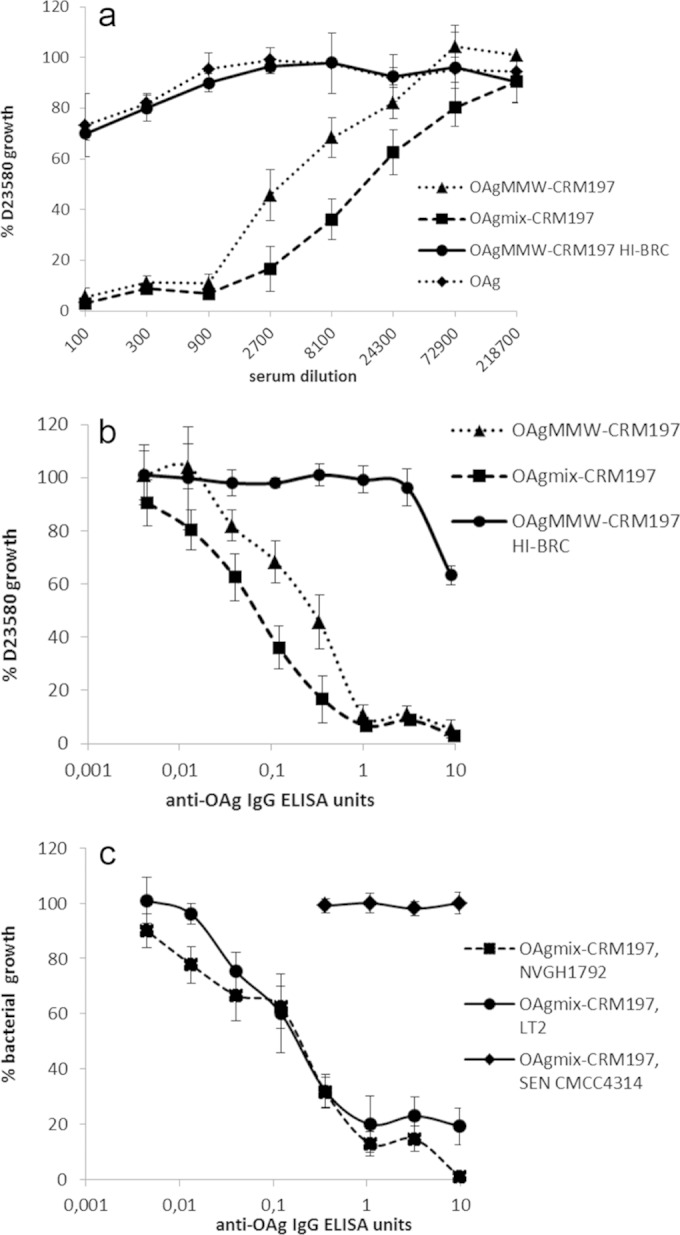

To evaluate the functional activity of elicited antibodies, sera from immunized mice were tested using an SBA. Both D23580 conjugates tested in the first study induced antibodies with high SBA activity (Fig. 4a and b), with >50% growth inhibition of D23580 obtained with about 1:16,000 serum dilution for OAgmix and 1:4,500 for OAgMMW, corresponding to less than 1 ELISA anti-OAg IgG unit. No statistical difference in SBA activity was found between the two conjugates (except at a 1:8,100 dilution, corresponding to 0.1 ELISA units, where D23580 OAgmix-CRM197 was found to be more bactericidal than OAgMMW-CRM197 [P = 0.03]).

FIG 4.

First immunization study. Conjugates with OAg from the D23580 strain were evaluated. SBAs were performed with pooled mouse sera (8 μg/dose, day 42) from OAgmix-CRM197 and OAgMMW-CRM197 (OAg from D23580) immunization groups against S. Typhimurium D23580, with SBA activity expressed in terms of serum dilutions (a); SBA against S. Typhimurium D23580, with SBA activity normalized for anti-OAg IgG ELISA units (b); or SBA against S. Typhimurium NVGH1792, S. Typhimurium LT2, and S. Enteritidis CMCC4314 (c). The data are presented as the percent CFU of S. Typhimurium D23580 recovered from each pooled serum dilution with active/inactive BRC compared to the CFU of the same serum dilutions with no BRC, as a function of anti-OAg ELISA units detected in each serum pool. Error bars represent standard errors.

No growth inhibition was found with sera from unconjugated OAg (Fig. 4a) or from OAg mixed with CRM197 and LPS groups (data not shown), which were both similar to the negative control (OAgMMW-CRM197 with heat-inactivated BRC). Antibodies induced by D23580 OAgmix conjugate were bactericidal against both NVGH1792 and LT2 strains, with comparable levels of growth inhibition, as seen with D23580 (Fig. 4c). As expected, SBA was OAg serovar specific, with no growth inhibition occurring when sera were tested against S. Enteritidis (O:9 antigen, CMCC4314 strain, Fig. 4c).

SBA activity was also tested for the conjugates of the second study, generated using different strain-specific OAg (and for D23580, using OAg at different MWs) (Fig. 5a). Sera from mice immunized with the LT2 OAgmix conjugate showed the lowest SBA activity compared to sera from NVGH1792 and D23580 OAgmix-CRM197 immunizations against D23580 (significant differences between LT2 and NVGH1792/D23580 OAgmix-CRM197 at dilutions of 1:540 to 1:4,860 and 1:540 to 1:1,620 [P ≤ 0.03 and P ≤ 0.02]). However, when SBA activities were normalized per ELISA unit of anti-S. Typhimurium OAg IgG, the bactericidal activity induced by the LT2 conjugate overlapped that of D23580 OAg-CRM197 (Fig. 5b), while the NVGH1792 conjugate yielded significantly more growth inhibition per ELISA unit (P < 0.01 in an ELISA unit interval of 0.01 to 0.3). We further investigated the relationship between anti-OAg antibody amounts and SBA activity by testing sera from individual mice from the NVGH1792 conjugate group for ability to kill D23580 (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). All mouse sera (except for one mouse) produced strong growth inhibition with >1 ELISA units. However, the anti-OAg IgG ELISA units for 50% killing of D23580 ranged between 0.003 and 0.3 ELISA units, corresponding to serum dilutions 1:20 to 1:30,000, suggesting that antibody quality, as well as quantity, determines bactericidal potential of individual sera.

FIG 5.

Second immunization study. Conjugates with OAg from three different S. Typhimurium strains—D23580 (tested at different OAg MWs and OAg/CRM197 ratios), NVGH1792, and LT2—were evaluated. The data are presented as the percent CFU of S. Typhimurium D23580 recovered from each serum dilution with active BRC compared to the CFU of the same serum dilution with no BRC, as a function of serum dilutions (SBA from all conjugate groups and unconjugated OAg control group are represented) (a), and the standard errors are shown only for D23580, NVGH1792, and LT2 OAgmix-CRM197 conjugates; anti-OAg IgG ELISA units (SBA from the sera of mice immunized with D23580, NVGH1792, and LT2 OAgmix-CRM197 conjugates) (b); and anti-OAg IgG ELISA units (SBA from the sera of mice immunized with D23580 OAg conjugates; OAgHMW(9.2)-CRM197 was not plotted because the ELISA units were below MLD) (c).

When comparing responses to D23580 conjugates of different MWs, sera from mice immunized with D23580 OAgHMW conjugates produced less SBA activity than sera from mice immunized with conjugates containing D23580 OAgMMW and OAgmix (Fig. 5a), a finding consistent with the ELISA results (Fig. 3a). However, after normalization per ELISA units, overlapping SBA curves were found for all conjugate sera, indicating that antibodies induced by conjugates with different lengths of D23580 OAg had similar bactericidal activities (Fig. 5c).

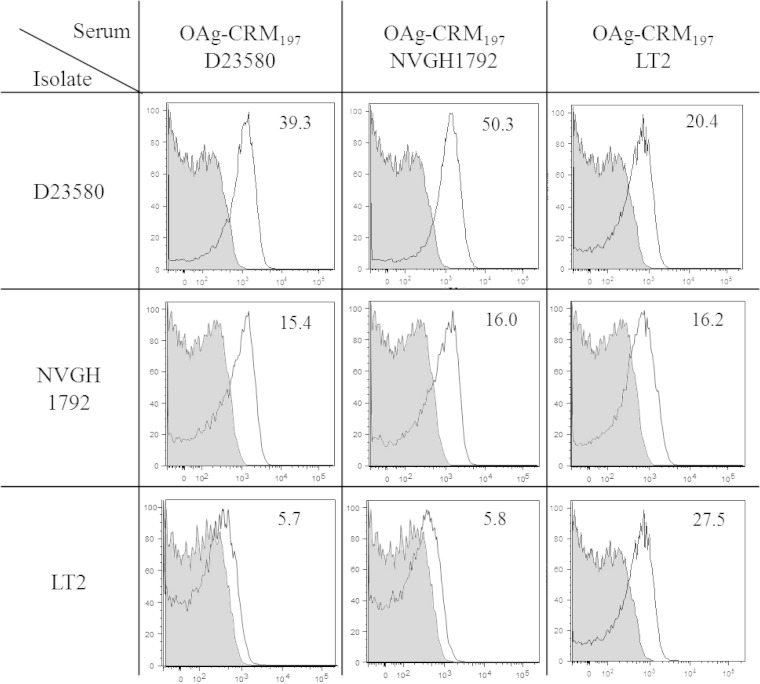

Flow cytometry.

To evaluate possible differences in cell surface binding, sera from mice immunized with D23580, NVGH1792, or LT2 conjugates were tested by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) against both homologous and heterologous strains of S. Typhimurium (Fig. 6). Both D23580 and NVGH1792 conjugates elicited anti-OAg IgG with good binding capacity against D23580 and NVGH1792 but poor recognition of LT2. In contrast, LT2 OAg-conjugate elicited antibodies that could bind all three strains similarly.

FIG 6.

Second immunization study. Conjugates with OAg from three different S. Typhimurium strains—D23580, NVGH1792, and LT2—were evaluated. FACS was performed using the sera from mice immunized with OAgmix-CRM197 using OAg from D23580, NVGH1792, and LT2 strains and salmonellae from homologous and heterologous strains. Geometric mean ratios of fluorescent signals obtained with positive (white, bacteria incubated with tested serum and secondary antibody) versus negative (gray, bacteria incubated with serum only) controls are indicated for each experiment.

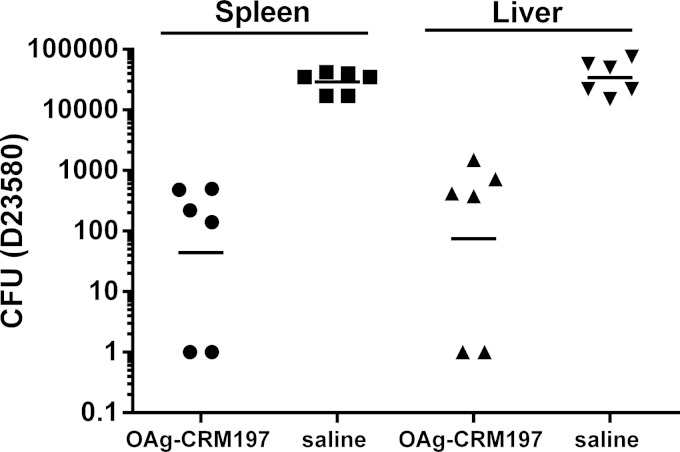

Mouse challenge experiment.

In order to confirm the potential in vivo efficacy of an S. Typhimurium O-antigen–CRM197 conjugate vaccine, we performed a Salmonella challenge study. Based on the immunogenicity results obtained with the different conjugates, D23580 OAgmix-CRM197 was selected for this study. Mice were immunized on days 0, 14, and 28 and challenged with D23580 on day 45. Spleens and livers were examined for bacterial burden 24 h later. Immunized mice showed a 2-log reduction compared to unimmunized control mice in the bacterial colonization of spleens and livers after challenge (Fig. 7).

FIG 7.

In vivo challenge study. Mice were immunized with 1 μg/dose D23580 OAg conjugate (OAg with mixed-MW populations) and saline at days 0, 24, and 48 and then challenged with S. Typhimurium D23580 at day 45. Bacterial CFU were measured in spleens and livers at 24 h postchallenge. Individual animals are represented by dots; the solid bar represents the group geometric mean.

DISCUSSION

Salmonella Typhimurium is among the most important causes of bacterial bloodstream infections in Africa. The huge burden of iNTS disease—estimated at ∼1 million clinical cases per year—coupled with high mortality (around 200,000 deaths/year), multidrug resistance, and difficulty in diagnosis (1) makes this disease a high priority for vaccine development.

Conjugation of a polysaccharide antigen to a carrier protein constitutes a strategy of proven effectiveness to enhance the immunogenicity of polysaccharide alone by inducing T-helper cell-mediated antibody responses (38, 39). To design glycoconjugates with the potential of being effective vaccines, several biochemical factors need to be evaluated that can affect the immunogenicity and tolerability of the final product. Among the most important parameters are the carrier protein (9, 40, 41) and the conjugation chemistry chosen (9, 12, 42), but additional factors, including the molecular weight (MW) of the polysaccharide (43–45), saccharide modifications (such as O-acetylation and glucosylation) (12, 43), and the sugar/carrier ratio (25, 44, 46), need to be explored (47).

With the aim of designing effective glycoconjugate vaccines against iNTS disease, we generated a range of conjugates, by extracting OAg from three different S. Typhimurium strains (Table 1) and coupling them to CRM197 (Table 2), a carrier widely used in licensed vaccines for routine infant immunization (26). Since S. Typhimurium OAg size and structure impact the immune response (25, 48, 49), we investigated both aspects by producing strain-specific conjugates, with OAg populations differing only for the average MW and OAg/CRM197 ratio (D23580 OAg vaccines) and strain-variant conjugates, with OAg differing for both O-acetylation (position and amounts of O-acetyl groups) and glucosylation levels.

In all strains tested, we observed a bimodal distribution of OAg size, as previously described (49, 50), with two main populations of OAg: one at a higher MW (OAgHMW) and one at a medium MW (OAgMMW), representing averages of 70 to 95 OAg repeating units and 25 to 35 OAg repeating units, respectively. OAg with even lower MWs were also detected but not purified, as previous work has shown a lack of immunogenicity for such preparations, when mainly constituted by core sugars (25, 43). Considering that OAg length can be regulated by the wzz genes, which are influenced by growth conditions (51, 52), all strains were grown in the same medium.

When the immunogenicities of D23580 conjugates prepared with OAg from different MW populations were compared, there was no difference for OAgMMW and OAgmix conjugates (Fig. 2a and 4a). A possible explanation for this could be that in OAgmix conjugates, the OAgMMW population outcompetes the OAgHMW fraction during conjugation, resulting in OAgmix conjugates that would predominantly contain OAgMMW. Conjugates made with the OAgHMW population were considerably less immunogenic than those made using OAgMMW or OAgmix. In particular, the OAgHMW(9.2) conjugate, at the low dose used, could not elicit any anti-OAg antibody response detectable by our ELISA (Fig. 4a). The lack of immunogenicity seen with OAgHMW conjugates, especially when containing a higher OAg/CRM197 wt/wt ratio, may be related to the lower dose of CRM197 received by the mice: 0.04 μg [for OAgHMW(3.1)-CRM197] and 0.01 μg [for OAgHMW(9.2)-CRM197] compared to 0.08 (for OAgmix-CRM197) and 0.09 μg (for OAgMMW-CRM197).

With the aim of evaluating the specific bactericidal potential of anti-OAg IgG elicited by each D23580 conjugate, irrespective of amount of serum antibodies (Fig. 5a), SBA activity was normalized for anti-OAg IgG ELISA units (Fig. 5c). A similar bactericidal activity was found for all D23580 conjugates, indicating that the intrinsic antibody bactericidal properties were similar for all conjugates synthesized using different OAg sizes from the same strain.

To evaluate whether fine differences in OAg structure may influence immunogenicity, OAgmix from three different strains were conjugated to CRM197 and tested in mice. These OAg were similar in terms of MW distribution but differed in glucosylation levels (41% for D23580 OAg compared to 8 and 11% for LT2 and NVGH1792 OAg, respectively) and O-acetylation levels and positions (D23580 and NVGH1792 OAg have twice the O-acetylation levels of LT2, with more than one O-acetyl group present per OAg repeating unit) (Table 1, Fig. 1) (37). Such modifications of OAg fine specificities can be caused by bacteriophages (36) or by specific chromosomal genes (53) and can influence pathogenicity. Limited investigations of the relevance and widespread presence of such modifications have shown that most S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis strains are glucosylated and O acetylated, with more diversity reported for S. Enteritidis compared to S. Typhimurium (54). O-acetylation and glucosylation can affect the three-dimensional structure of the OAg molecule and change conformational epitopes. Comparing conjugates made with OAg from three different strains (D23580, NVGH1792, and LT2), we could find differences in both immunogenicity and SBA activity. Considering that the MW distributions and OAg/CRM197 ratios for the three conjugates were very similar, such differences could be attributed to strain-specific OAg modifications. In terms of immunogenicity, the strain with highest O-acetylation and glucosylation levels (D23580) generated more IgG antibodies (Fig. 3c). D23580 has O-acetylation levels similar to those of NVGH1792 but 5-fold-higher glucosylation levels, which may be a critical factor for immunogenicity. Considering that D23580 antibodies could equally bind to D23580 and NVGH1792 OAg in an ELISA (Fig. 3d) but not to LT2 OAg, it is possible that a large proportion of them recognize OAg O-acetylated epitopes on rhamnose. Although consistent with FACS data, where very little signal was found with serum from mice immunized with D23580 and NVGH1792 conjugates incubated with LT2 bacteria (Fig. 6), we cannot rule out that the low ELISA responses obtained for all conjugate groups against LT2 OAg may also be due to poor binding of this OAg on ELISA plates. In contrast to what was found with D23580 and NVGH1792 conjugates, antibodies elicited by LT2 OAg conjugate could bind all three strains as determined by FACS, suggesting that these antibodies bind epitopes common to all of the three strains (Fig. 6).

In terms of SBA, all conjugates synthesized using OAg from the three S. Typhimurium strains could induce bactericidal antibodies, with strong SBA activity obtained with as little as 1 anti-OAg ELISA unit (Fig. 5b). Compared as a function of serum dilution (Fig. 5a), LT2-conjugate serum required a higher concentration of serum than did D23580- and NVGH1792-conjugate sera to achieve the same growth inhibition, a finding consistent with the lower immunogenicity of the LT2 conjugate (Fig. 3c). Once normalized for anti-OAg IgG serum levels, although D23580 and LT2 conjugates varied most for both O-acetylation and glucosylation levels, the anti-OAg IgG antibodies they induced showed similar bactericidal properties, whereas NVGH1792 induced higher SBA activity per ELISA unit (Fig. 5b). It is not clear which NVGH1792-specific OAg feature is responsible for this, and further investigations are required. However, these data show that in synthesizing glycoconjugates against S. Typhimurium, the selection of the strain as OAg source is important, and different strains may result in candidate vaccines with different immunogenicity and antibodies with potentially different cross-reactivity (Fig. 6). Using the in vivo Salmonella challenge study in mice, we were able to demonstrate the efficacy of the D23580 OAg-CRM197 conjugate at reducing bacterial load in the liver and spleen.

An effective glycoconjugate vaccine candidate against invasive African S. Typhimurium should be highly immunogenic and able to elicit bactericidal antibodies. Our study indicates that these immunological characteristics are specifically influenced by OAg glucosylation, OAg MW, and the OAg/CRM197 ratio. The strongest anti-OAg antibody responses were elicited by the conjugate containing OAg with the highest glucosylation levels, mixed or MMW OAg populations, and with an OAg/CRM197 ratio optimized according to the OAg MW (in the present study, a wt/wt ratio of ∼1.5 was the ratio that yielded the best conjugation efficiency). In addition, to generate bactericidal anti-OAg antibodies cross-protective against endemic invasive African S. Typhimurium strains, particular consideration should be given to the interplay of both O-acetylation and glucosylation levels.

To specifically address this last point, further studies are ongoing with additional conjugates made of OAg characterized by different O-acetylation (amount and position) and glucosylation levels. Sera produced in response to immunization with these conjugates will be tested against a broader range of clinical S. Typhimurium isolates.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Robert Heyderman (Malawi-Liverpool-Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Programme) for supplying S. Typhimurium D23580.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.03079-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Feasey NA, Dougan G, Kingsley RA, Heyderman RS, Gordon MA. 2012. Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella disease: an emerging and neglected tropical disease in Africa. Lancet 379:2489–2499. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61752-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon MA. 2011. Invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella disease: epidemiology, pathogenesis and diagnosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 24:484–489. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834a9980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacLennan CA, Gondwe EN, Msefula CL, Kingsley RA, Thomson NR, White SA, Goodall M, Pickard DJ, Graham SM, Dougan G, Hart CA, Molyneux ME, Drayson MT. 2008. The neglected role of antibody in protection against bacteremia caused by nontyphoidal strains of Salmonella in African children. J Clin Invest 118:1553–1562. doi: 10.1172/JCI33998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gondwe EN, Molyneux ME, Goodall M, Graham SM, Mastroeni P, Drayson MT, MacLennan CA. 2010. Importance of antibody and complement for oxidative burst and killing of invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella by blood cells in Africans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:3070–3075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910497107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vishwakarma V, Pati NB, Chandel HS, Sahoo SS, Saha B, Suar M. 2012. Evaluation of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium TTSS-2 deficient fur mutant as safe live-attenuated vaccine candidate for immunocompromised mice. PLoS One 7:e52043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tennant SM, Wang JY, Galen JE, Simon R, Pasetti MF, Gat O, Levine MM. 2011. Engineering and preclinical evaluation of attenuated nontyphoidal Salmonella strains serving as live oral vaccines and as reagent strains. Infect Immun 79:4175–4185. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05278-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Secundino I, Lopez-Macias C, Cervantes-Barragan L, Gil-Cruz C, Rios-Sarabia N, Pastelin-Palacios R, Villasis-Keever MA, Becker I, Puente JL, Calva E, Isibasi A. 2006. Salmonella porins induce a sustained, lifelong specific bactericidal antibody memory response. Immunology 117:59–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gil-Cruz C, Bobat S, Marshall JL, Kingsley RA, Ross EA, Henderson IR, Leyton DL, Coughlan RE, Khan M, Jensen KT, Buckley CD, Dougan G, MacLennan IC, Lopez-Macias C, Cunningham AF. 2009. The porin OmpD from nontyphoidal Salmonella is a key target for a protective B1b cell antibody response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:9803–9808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812431106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon R, Tennant SM, Wang JY, Schmidlein PJ, Lees A, Ernst RK, Pasetti MF, Galen JE, Levine MM. 2011. Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis core O polysaccharide conjugated to H:g,m flagellin as a candidate vaccine for protection against invasive infection with S. Enteritidis. Infect Immun 79:4240–4249. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05484-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jorbeck HJ, Svenson SB, Lindberg AA. 1981. Artificial Salmonella vaccines: Salmonella typhimurium O-antigen-specific oligosaccharide-protein conjugates elicit opsonizing antibodies that enhance phagocytosis. Infect Immun 32:497–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jazani NH, Worobec E, Shahabi S, Nejad GB. 2005. Conjugation of tetanus toxoid with Salmonella typhimurium PTCC 1735 O-specific polysaccharide and its effects on production of opsonizing antibodies in a mouse model. Can J Microbiol 51:319–324. doi: 10.1139/w05-008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watson DC, Robbins JB, Szu SC. 1992. Protection of mice against Salmonella typhimurium with an O-specific polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccine. Infect Immun 60:4679–4686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Svenson SB, Nurminen M, Lindberg AA. 1979. Artificial Salmonella vaccines: O-antigenic oligosaccharide-protein conjugates induce protection against infection with Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun 25:863–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heath PT. 1998. Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccines: a review of efficacy data. Pediatr Infect Dis J 17:S117–S122. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199809001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pace D, Pollard AJ, Messonier NE. 2009. Quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccines. Vaccine 27:B30–B41. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pilishvili T, Lexau C, Farley MM, Hadler J, Harrison LH, Bennett NM, Reingold A, Thomas A, Schaffner W, Craig AS, Smith PJ, Beall BW, Whitney CG, Moore MR. 2010. Sustained reductions in invasive pneumococcal disease in the era of conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis 201:32–41. doi: 10.1086/648593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagy G, Pal T. 2008. Lipopolysaccharide: a tool and target in enterobacterial vaccine development. Biol Chem 389:513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colwell DE, Michalek SM, Briles DE, Jirillo E, McGhee JR. 1984. Monoclonal antibodies to Salmonella lipopolysaccharide: anti-O-polysaccharide antibodies protect C3H mice against challenge with virulent Salmonella Typhimurium. J Immunol 133:950–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raetz CRH, Whitfield C. 2002. Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu Rev Biochem 71:635–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hellerqvist C, Lindberg B, Svensson S, Holme T, Lindberg AA. 1968. Structural studies on O-specific side chains of cell wall lipopolysaccharide from Salmonella Typhimurium 395 Ms. Carbohydr Res 8:43. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6215(00)81689-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joiner KA, Hammer CH, Brown EJ, Cole RJ, Frank MM. 1982. Studies on the mechanism of bacterial resistance to complement-mediated killing. 1. Terminal complement components are deposited and released from Salmonella Minnesota S218 without causing bacterial death. J Exp Med 155:797–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saxen H, Reima I, Makela PH. 1987. Alternative complement pathway activation by Salmonella O polysaccharide as a virulence determinant in the mouse. Microb Pathog 2:15–28. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trebicka E, Jabob S, Pirzai W, Hurley BP, Cherayil BJ. 2013. Role of antilipopolysaccharide antibodies in serum bactericidal activity against Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in healthy adults and children in the United States. Clin Vaccine Immunol 20:1491–1498. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00289-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Konadu EY, Lin FY, Ho VA, Thuy NT, Van BP, Thanh TC, Khiem HB, Trach DD, Karpas AB, Li J, Bryla DA, Robbins JB, Szu SC. 2000. Phase 1 and phase 2 studies of Salmonella enterica serovar Paratyphi A O-specific polysaccharide-tetanus toxoid conjugates in adults, teenagers, and 2- to 4-year-old children in Vietnam. Infect Immun 68:1529–1534. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.3.1529-1534.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Svenson SB, Lindberg AA. 1981. Artificial Salmonella vaccines: Salmonella Typhimurium O antigen-specific oligosaccharide protein conjugates elicit protective antibodies in rabbits and mice. Infect Immun 32:490–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broker M, Costantino P, DeTora L, McIntosh ED, Rappuoli R. 2011. Biochemical and biological characteristics of cross-reacting material 197 (CRM197), a nontoxic mutant of diphtheria toxin: use as a conjugation protein in vaccines and other potential clinical applications. Biologicals 39:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Micoli F, Rondini S, Gavini M, Pisoni I, Lanzilao L, Colucci AM, Giannelli C, Pippi F, Sollai L, Pinto V, Berti F, MacLennan CA, Martin LB, Saul A. 2013. A scalable method for O-antigen purification applied to different Salmonella serovars. Anal Biochem 434:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2012.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Micoli F, Rondini S, Gavini M, Lanzilao L, Medaglini D, Saul A, Martin LB. 2012. O:2-CRM197 conjugates against Salmonella Paratyphi A. PLoS One 7:e47039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kingsley RA, Msefula CL, Thomson NR, Kariuki S, Holt KE, Gordon MA, Harris D, Clarke L, Whitehead S, Sangal V, Marsh K, Achtman M, Molyneux ME, Cormican M, Parkhill J, MacLennan CA, Heyderman RS, Dougan G. 2009. Epidemic multiple drug resistant Salmonella Typhimurium causing invasive disease in sub-Saharan Africa have a distinct genotype. Genome Res 19:2279–2287. doi: 10.1101/gr.091017.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okoro CK, Kingsley RA, Connor TR, Harris SR, Parry CM, Al-Mashhadani MN, Kariuki S, Msefula CL, Gordon MA, de Pinna E, Wain J, Heyderman RS, Obaro S, Alonso PL, Mandomando I, MacLennan CA, Tapia MD, Levine MM, Tennant SM, Parkhill J, Dougan G. 2012. Intracontinental spread of human invasive Salmonella Typhimurium pathovariants in sub-Saharan Africa. Nat Genet 44:1215–1221. doi: 10.1038/ng.2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rondini S, Micoli F, Lanzilao L, Hale C, Saul AJ, Martin LB. 2011. Evaluation of the immunogenicity and biological activity of the Citrobacter freundii Vi-CRM197 conjugate as a vaccine for Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. Clin Vaccine Immunol 18:460–468. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00387-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dubois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F. 1956. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem 28:350–356. doi: 10.1021/ac60111a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skarnes WC, Rosen B, West AP, Koutsourakis M, Bushell W, Iyer V, Mujica AO, Thomas M, Harrow J, Cox T, Jackson D, Severin J, Biggs P, Fu J, Nefedov M, de Jong PJ, Stewart AF, Bradley A. 2011. A conditional knockout resource for the genome-wide study of mouse gene function. Nature 474:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature10163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rondini S, Lanzilao L, Necchi F, O'Shaughnessy CM, Micoli F, Saul A, MacLennan CA. 2013. Invasive African Salmonella Typhimurium induces bactericidal antibodies against O-antigens. Microb Pathog 63:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reed GF, Meade BD, Steinhoff MC. 1995. The reverse cumulative distribution plot: a graphic method for exploratory analysis of antibody data. Pediatrics 96:600–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wollin R, Stocker BA, Lindberg AA. 1987. Lysogenic conversion of Salmonella typhimurium bacteriophages A3 and A4 consists of O-acetylation of rhamnose of the repeating unit of the O-antigenic polysaccharide chain. J Bacteriol 169:1003–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Micoli F, Ravenscroft N, Cescutti P, Stefanetti G, Londero S, Rondini S, Maclennan CA. 2014. Structural analysis of O-polysaccharide chains extracted from different Salmonella Typhimurium strains. Carbohydr Res 385:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Makela PH, Kayhty H. 2002. Evolution of conjugate vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines 1:399–410. doi: 10.1586/14760584.1.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weintraub A. 2003. Immunology of bacterial polysaccharide antigens. Carbohydr Res 338:2539–2547. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2003.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Passwell JH, Harlev E, Ashkenazi S, Chu C, Miron D, Ramon R, Farzan N, Shiloach J, Bryla DA, Majadly F, Roberson R, Robbins JB, Schneerson R. 2001. Safety and immunogenicity of improved Shigella O-specific polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccines in adults in Israel. Infect Immun 69:1351–1357. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1351-1357.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pavliakova D, Chu C, Bystricky S, Tolson NW, Shiloach J, Kaufman JB, Bryla DA, Robbins JB, Schneerson R. 1999. Treatment with succinic anhydride improves the immunogenicity of Shigella flexneri type 2a O-specific polysaccharide-protein conjugates in mice. Infect Immun 67:5526–5529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta RK, Szu SC, Finkelstein RA, Robbins JB. 1992. Synthesis, characterization, and some immunological properties of conjugates composed of the detoxified lipopolysaccharide of Vibrio cholerae O1 serotype Inaba bound to cholera toxin. Infect Immun 60:3201–3208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Konadu E, Shiloach J, Bryla DA, Robbins JB, Szu SC. 1996. Synthesis, characterization, and immunological properties in mice of conjugates composed of detoxified lipopolysaccharide of Salmonella Paratyphi A bound to tetanus toxoid with emphasis on the role of O acetyls. Infect Immun 64:2709–2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pozsgay V, Chu C, Pannell L, Wolfe J, Robbins JB, Schneerson R. 1999. Protein conjugates of synthetic saccharides elicit higher levels of serum IgG lipopolysaccharide antibodies in mice than do those of the O-specific polysaccharide from Shigella dysenteriae type 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:5194–5197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robbins JB, Kubler-Kielb J, Vinogradov E, Mocca C, Pozsgay V, Shiloach J, Schneerson R. 2009. Synthesis, characterization, and immunogenicity in mice of Shigella sonnei O-specific oligosaccharide-core-protein conjugates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:7974–7978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900891106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phalipon A, Tanguy M, Grandjean C, Guerreiro C, Belot F, Cohen D, Sansonetti PJ, Mulard LA. 2009. A synthetic carbohydrate-protein conjugate vaccine candidate against Shigella flexneri 2a infection. J Immunol 182:2241–2247. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Costantino P, Rappuoli R, Berti F. 2011. The design of semi-synthetic and synthetic glycoconjugate vaccines. Expert Opin Drug Discov 6:1045–1066. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2011.609554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holzer SU, Schlumberger MC, Jackel D, Hensel M. 2009. Effect of the O-antigen length of lipopolysaccharide on the functions of type III secretion systems in Salmonella enterica. Infect Immun 77:5458–5470. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00871-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murray GL, Attridge SR, Morona R. 2003. Regulation of Salmonella Typhimurium lipopolysaccharide O antigen chain length is required for virulence: identification of FepE as a second Wzz. Mol Microbiol 47:1395–1406. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peterson AA, McGroarty EJ. 1985. High-molecular-weight components in lipopolysaccharides of Salmonella typhimurium, Salmonella minnesota, and Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 162:738–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bravo D, Silva C, Carter JA, Hoare A, Alvarez SA, Blondel CJ, Zaldivar M, Valvano MA, Contreras I. 2008. Growth-phase regulation of lipopolysaccharide O-antigen chain length influences serum resistance in serovars of Salmonella. J Med Microbiol 57:938–946. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47848-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murray GL, Attridge SR, Morona R. 2005. Inducible serum resistance in Salmonella typhimurium is dependent on wzz(fepE)-regulated very long O antigen chains. Microbes Infect 7:1296–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Slauch JM, Mahan MJ, Michetti P, Neutra MR, Mekalanos JJ. 1995. Acetylation (O-factor 5) affects the structural and immunological properties of Salmonella typhimurium lipopolysaccharide O antigen. Infect Immun 63:437–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parker CT, Liebana E, Henzler DJ, Guard-Petter J. 2001. Lipopolysaccharide O-chain microheterogeneity of Salmonella serotypes Enteritidis and Typhimurium. Environ Microbiol 3:332–342. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2001.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.