Abstract

Group B streptococci (GBS; Streptococcus agalactiae) are beta-hemolytic, Gram-positive bacteria that are common asymptomatic colonizers of healthy adults. However, these opportunistic bacteria also cause invasive infections in human newborns and in certain adult populations. To adapt to the various environments encountered during its disease cycle, GBS encodes a number of two-component signaling systems. Previous studies have indicated that the TCS comprising the sensor histidine kinase RgfC and the response regulator RgfA mediate GBS binding to extracellular matrix components, such as fibrinogen. However, in certain GBS clinical isolates, a point mutation in rgfA results in premature truncation of the response regulator. The truncated RgfA protein lacks the C-terminal DNA binding domain necessary for promoter binding and gene regulation. Here, we show that deletion of rgfC in GBS strains lacking a functional RgfA increased systemic infection. Furthermore, infection with the rgfC mutant increased induction of proinflammatory signaling pathways in vivo. Phosphoproteomic analysis revealed that 19 phosphopeptides corresponding to 12 proteins were differentially phosphorylated at aspartate, cysteine, serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues in the rgfC mutant. This included aspartate phosphorylation of a tyrosine kinase, CpsD, and a transcriptional regulator. Consistent with this observation, microarray analysis of the rgfC mutant indicated that >200 genes showed altered expression compared to the isogenic wild-type strain and included transcriptional regulators, transporters, and genes previously associated with GBS pathogenesis. Our observations suggest that in the absence of RgfA, nonspecific RgfC signaling affects the expression of virulence factors and GBS pathogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

All living organisms sense and adapt to dynamic changes in their environment using signaling systems. Signaling in prokaryotic organisms is achieved primarily by two-component signaling systems (TCS) that regulate gene expression in response to environmental signals (1–5). A typical two-component system comprises a membrane-associated sensor histidine kinase that responds to an environmental signal and phosphorylates its cognate DNA binding response regulator at an aspartate residue. Phosphorylation often alters the affinity of the response regulator to its target promoters, regulating gene expression.

Group B streptococci (GBS) or Streptococcus agalactiae strains are a common cause of bacterial infections in human newborns and are emerging pathogens of adult humans (6). These bacteria reside as commensal organisms in the lower gastrointestinal and genital tracts of healthy adult women. Human neonates are at risk for GBS infections due to ascending infection from the lower genital tract or from aspiration of contaminated amniotic/vaginal fluids during birth. GBS can disseminate into multiple neonatal organs, causing pneumonia, sepsis, and meningitis (for reviews, see references 6–8). Thus, GBS has to efficiently adapt to the changing environmental conditions encountered during its life cycle.

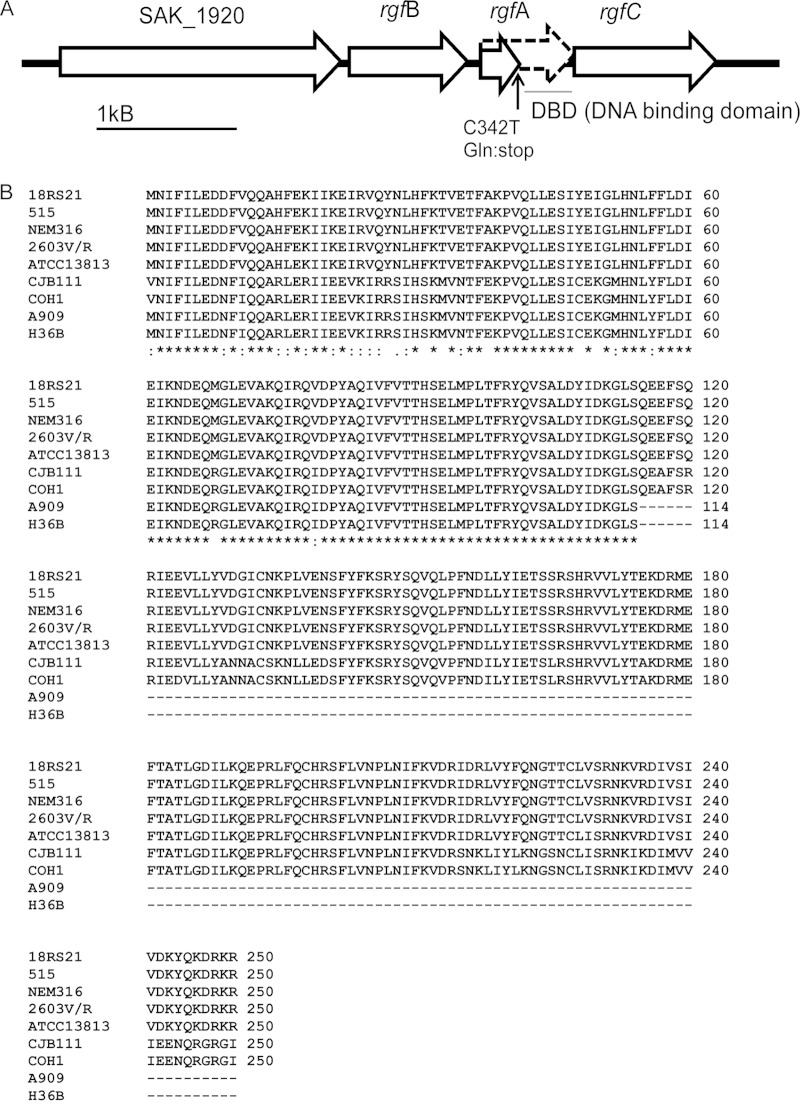

Signaling mechanisms that enable GBS transition from commensal environments to invasive niches is not understood (8). Like other prokaryotic organisms, signaling in GBS is achieved primarily by two-component signaling systems (TCS) that regulate gene expression in response to external signals (1, 3, 4). The GBS genome sequence indicates the presence of 18 to 20 TCS (9), and the roles of a few TCS have been well characterized and include CovR/CovS (10–15), DltR/DltS (16), CiaH/CiaR (17), SAK_0188/0189 (18), RgfC/A (19, 20), and FpsR/S (21). Previous studies have indicated that GBS deficient for RgfC/A exhibit reduced adherence to extracellular matrix components due to altered expression of the fibrinogen binding proteins, such as FbsA and FbsB (19, 20). However, in certain GBS clinical isolates that were obtained from infected newborns (e.g., A909 and H36B), a point mutation in rgfA results in the premature truncation of the response regulator (9; also see the schematic in Fig. 1A and B); this feature was observed in another 61 GBS strains (21). The truncated RgfA protein lacks the C-terminal DNA binding domain necessary for promoter binding and regulation of gene expression. The presence of a spontaneous mutation resulting in premature truncation of the response regulator rgfA in certain GBS strains and regulation of these genes by CovR/S (12) prompted us to determine if RgfC function was abolished in strains lacking a functional RgfA. Here, we show that in strains lacking a functional RgfA, deletion of RgfC increased the expression of virulence factors and systemic GBS infection. These data suggest that nonspecific kinase activity in the absence of the cognate response regulator affects GBS virulence.

FIG 1.

Sequence alignment and open reading frame of the TCS RgfC/A in GBS. (A) rgfC encodes a sensor histidine kinase, rgfB shows homology to nucleases, and SAK_1920 encodes a putative glucose-specific phosphotransferase system (PTS) transporter. In GBS A909, RgfA is truncated by the nonsense mutation C342T; thus, it lacks the DNA binding domain. (B) Alignment of the available RgfA sequences shows that the nonsense mutation present in A909 also is found in H36B.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General growth.

The strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The wild-type (WT) GBS strains A909 and COH1 are clinical isolates belonging to capsular polysaccharide serotype 1a (22) and serotype III (23), respectively. Routine cultures of GBS were performed in tryptic soy broth (TSB; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Routine cultures of Escherichia coli were performed in Luria-Bertani broth (LB; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) at 37°C. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), unless mentioned otherwise. GBS cell growth was monitored at 600 nm after incubation in 5% CO2 at 37°C unless mentioned otherwise. Antibiotics were added at the following concentrations when necessary: for GBS, erythromycin, 1 μg ml−1; kanamycin, 1,000 μg ml−1; chloramphenicol, 2.5 to 5 μg ml−1; spectinomycin, 300 μg ml−1; for E. coli, erythromycin, 300 μg ml−1; kanamycin, 50 μg ml−1; chloramphenicol, 10 μg ml−1; spectinomycin, 50 μg ml−1.

Construction of ΔrgfCA mutants.

Approximately 1 kb of DNA located upstream of rgfA was amplified using the primers upstream F and upstream R and high-fidelity PCR (Invitrogen, CA, USA). Likewise, 1 kb of DNA downstream of rgfC was amplified using primers downstream F and downstream R as described above. The gene conferring kanamycin resistance (Ωkm-2) was amplified from pCIV2 (24) using primers KanF and KanR for allelic replacement of rgfC and rgfA (denoted rgfCAd for A909). Subsequently, splicing by overlap extension PCR (SOEing PCR) (25) was performed to introduce the antibiotic resistance gene between the flanking regions of rgfC and rgfA described above. The PCR fragment then was ligated into the temperature-sensitive vector pHY304 (26), and the resulting plasmid (ΔrgfCA::kn) was electroporated into GBS A909 and COH1 as described previously (27). Selection and screening for the double crossover (ΔrgfCA::kn) was performed as described previously (27). PCR was used to verify the presence of Ωkm-2 and the absence of rgfCA. The A909 ΔrgfCAd strain was used as the parent strain to derive the ΔrgfCAd ΔcspA double mutant. The gene cspA was allelically replaced with aad9, encoding spectinomycin resistance in pLZ12spec (28), using SOEing PCR and PCR products obtained from primer pairs cpsAupF and cspAupR, specF and specR, and cpsAdnF and cspAdnR. PCR was used to verify the allelic replacement of cpsA with aad9 (encoding spectinomycin resistance). The complementing pRgfC and pRgfAd plasmids were constructed by amplifying rgfC using primers pDCSAK_1917F and pDCSAK_1917R and rgfAd using primers pDCSAK_1918F and pDCSAK_1918R, respectively, and A909 genomic DNA was used as the template. The PCR fragment was digested with restriction enzymes present on the primer sequence(s) and then cloned into the multiple cloning site of the GBS complementation vector pDC123 downstream of the constitutive promoter as described previously (27, 29). The complementing plasmid for corrected pRgfCA, i.e., functional rgfA without the premature stop codon, was obtained by amplifying rgfCA with GBS COH1 DNA as the template using the Gibson Assembly cloning kit by following the manufacturer's instructions (New England BioLabs, USA). Overlapping primers (RgfA-Gibson-F, RgfA-Gibson-FC, RgfC-Gibson-R, and RgfC-Gibson-RC) were designed to amplify rgfCA from COH1 and the GBS complementation vector pDC123 such that the insert DNA was downstream of the constitutive promoter in pDC123. In all cases, DNA sequencing was used to verify the orientation and sequence of cloned plasmids. The complementing plasmids then were electroporated into the A909 ΔrgfCAd mutant using methods described previously (27).

Virulence analysis.

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol 13311) and performed using guidelines in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th ed.) (30).

Neonatal rat sepsis model.

Virulence analysis using the neonatal rat sepsis model of infection was performed as described previously (31). Briefly, time-mated, female Sprague Dawley rats were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (MA, USA). WT A909 and ΔrgfCAd strains were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.3, washed, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline, and used as the inoculum. Groups of six rat pups (24 to 48 h of age) were given 10-fold serial dilutions of each strain by intraperitoneal injection, and the pups were checked for signs of morbidity every 8 h for 72 h. The 50% lethal dose (LD50; also called the 50% moribund dose [MD50]) estimates were derived using logistic regression models for the probability of death conditional on dose and strain as described previously (10). The experiment was repeated twice, and P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

GBS sepsis/meningitis model of infection.

The murine model of hematogenous GBS meningitis was used to compare the virulence potential of strains used in this study (32, 33). Briefly, 6-week-old male CD-1 mice obtained from Charles River Laboratories (MA, USA) were injected via the tail vein with 3 × 107 to 3 × 108 of either the WT A909 or isogenic ΔrgfCAd strain. Spleen and brains from infected mice were collected aseptically 24 h postinfection. Bacterial counts in spleen and brain homogenates were determined by plating serial 10-fold dilutions on TSB agar. Interleukin-6 (IL-6), MIP-2 (macrophage inflammatory protein 2, also known as CXCL2), and KC (keratinocyte-derived chemokine, also known as CXCL1; IL-8 homologue) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were performed on supernatants from spleen and brain homogenates using the DuoSet kit as described by the manufacturer (R&D Systems, USA).

Adherence and invasion of hBMEC.

The human brain microvascular endothelial cell (hBMEC) line, immortalized by transfection with the simian virus 40 (SV40) large T antigen (34), was used in these studies. Propagation of hBMEC and GBS adherence, invasion, and intracellular survival were performed as described previously (33). A 2-fold increase or decrease in adherence or invasion compared to the isogenic WT A909 was considered significant, as described previously (33).

Phosphopeptide enrichment and MS.

Total protein was isolated from the WT A909, the ΔrgfCAd mutant, and ΔrgfCAd/pRgfC complemented strain as described previously (35, 36). Briefly, GBS were grown to an OD600 of 0.6 in TSB. The bacteria were washed twice with 0.25× ice-cold buffer containing phosphatase inhibitors (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 10 mM NaF, 10 mM Na pyrophosphate, and 50 mM β-glycerophosphate). The cells subsequently were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, with the phosphatase inhibitors described above at a concentration of 5 mM) and disrupted using the FastPrep FP101 bead beater (Bio 101). The lysates were treated with DNase I and ultracentrifuged to pellet unlysed cells and cell debris at 25,000 × g as described previously (35, 36).The supernatant from each sample was normalized to contain equal amounts of protein. The proteins then were denatured and reduced in 4% SDS with 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) at 95°C for 5 min. Subsequently, the protein samples were added to centrifugal filter units with a 30-kDa molecular mass cutoff (Microcon-30; Millipore) and washed with 8 M urea in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). Proteins were alkylated with 30 mM iodoacetamide for 20 min at room temperature in the dark. The samples were washed again with 8 M urea in Tris-HCl before the buffer was changed to 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate. The samples were digested overnight at 37°C using sequencing-grade trypsin (1:50, trypsin to total protein). The next day, peptides were eluted from the filters using 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate followed by 0.5 M NaCl. The peptide samples were desalted using Sep-Pak C18 columns according to the manufacturer's instructions (Waters, USA) and dried using a Speedvac. From the peptide samples of each strain (800 μg), phosphopeptides were captured using a soluble nanopolymer functionalized with titanium, PolyMAC-Ti (Tymora Analytical, West Lafayette, IN), as described previously (37). Unbound nonphosphopeptides were washed away, and phosphopeptides were eluted as described previously (37). The samples were analyzed by capillary liquid chromatography-nanoelectrospray tandem mass spectrometry (μLC-nanoESI-MS/MS) with a high-resolution hybrid linear ion trap orbitrap (LTQ-orbitrap Velos; Thermo Fisher) coupled to an Eksigent NanoLC Ultra two-dimensional high-performance liquid chromatography (2D HPLC) system using methods described previously (36, 38). Data were searched using Proteome Discoverer software with the SEQUEST algorithm using a 10-ppm precursor mass tolerance and a 0.6-Da MS/MS mass tolerance. The searches included variable modifications on cysteine residues (+57.021 or +79.966), methionine residues (+15.995), and aspartate, serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues (+79.966) to identify phosphorylation as described previously (35, 36, 38). Spectra were searched against the GBS A909 genome database (accession number NC_007432) with a 1% false discovery rate (FDR) based on a reverse decoy database search. Proteome Discoverer generated a reverse decoy database from the GBS A909 protein database, and any peptides passing the initial filtering parameters of this decoy database were defined as false positives. Based on the number of random false positives matched to the decoy database, Proteome Discoverer adjusted the minimum cross-correlation factor (Xcorr) filter for each charge state to meet the predetermined target FDR of 1%. Thus, each data set had its own passing parameters. Phosphorylation site localization was determined from tandem mass spectra (39) with phosphoRS (40). The unique phosphopeptides and nonphosphopeptides identified then were manually counted and compared. For phosphopeptides with potentially ambiguous phosphorylation, only the top-scored phosphorylation site was used for further analysis.

Isolation and purification of GBS RNA.

Total RNA from GBS was isolated using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA) as described previously (13). In brief, GBS strains were grown to an OD600 of 0.6, centrifuged, washed in 1:1 mixed RNA Protect (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA) and Tris-EDTA buffer, and resuspended in kit-supplied RLT buffer. The cell suspensions were lysed through the use of a FastPrep FP101 bead beater (Bio 101), followed by clarification of the lysates via centrifugation. The supernatants then were purified and DNase digested (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA) as described by the RNeasy minikit manufacturer's instructions. RNA integrity and concentration were determined using an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) or a NanoDrop 1000 (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE) for use in microarrays or quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR), respectively.

GBS microarrays and qRT-PCR.

RNA was isolated from two independent biological replicates for each strain and purified as described above. Purified RNA was sent to NimbleGen Systems, Inc. (Madison, WI), for full expression services. NimbleGen performed cDNA synthesis, labeling of the cDNA, and hybridization of the labeled cDNA to the Streptococcus agalactiae A909 chip (A4327-00-01; NimbleGen Systems, Inc. Madison, WI) according to company protocols. The chips were composed of 18 probes per target sequence, and each probe was replicated five times (see www.nimblegen.com/products/exp/index.html for details). Microarray data were interpreted and analyzed using the program GeneSpring GX (version 7.3.1; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Genes with statistically significant differences among groups were calculated using the Welch t test (parametric, with variances not assumed equal) with a P value cutoff of 0.05 and an associated Benjamini and Hochberg FDR multiple-testing correction (about 5.0% of the identified genes would be expected to pass the restriction by chance) (41). Standard error propagation was calculated using the Delta method for ratios of means from the three independent biological replicates for A909 (WT) and ΔrgfCAd strains. All fold changes were defined as relative to the level for A909 WT. qRT-PCR was performed using a one-step QuantiTect SYBR green RT-PCR kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA) as described previously (13). The reference gene used for all runs was the housekeeping ribosomal protein S12 gene rpsL (10).

Sialic acid quantification of capsular polysaccharide (CPS).

As a measure of the amount of capsule produced by isogenic GBS strains, capsular sialic acid was quantified after acid hydrolysis of equivalent numbers of whole cells and measured by HPLC as described previously (42). Briefly, equivalent numbers of whole cells of each GBS strain were treated with 4N acetic acid for 1 h, and the sialic acid that was recovered was derivatized with fluorescent 1,2-diamino-4,5-methylene-dioxybenzene (DMB) and quantified compared to a standard curve using pure sialic acid (Sigma) similarly derivatized with DMB as described previously (42).

Statistical analysis.

Unless mentioned otherwise, the Mann-Whitney test or unpaired t test was used to estimate differences between GBS strains. These tests were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 5.0 for Windows; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Microarray data accession number.

The entire set of microarray data has been deposited at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under accession number GSE21563.

RESULTS

GBS deficient in RgfC expression exhibit increased virulence.

Our previous studies indicated that the CovR/S two-component system regulated the expression of rgfC and rgfA in GBS serotype Ia, strain A909 (12). The GBS strain A909 is a clinical isolate obtained from an infected newborn (23, 43), and genome sequencing indicated the presence of a point mutation encoding a stop codon in rgfA that results in premature truncation of the response regulator (9) (Fig. 1A and B). The same point mutation in rgfA also was identified in other GBS clinical strains, such as H36B (9) (Fig. 1B) and 61 other GBS strains (21). To determine if RgfC had a significant role in gene regulation and virulence of GBS in strains lacking a functional RgfA, we constructed a strain deficient in rgfC expression from the wild-type (WT) strain A909. Briefly, the entire coding sequence of rgfC and the nonfunctional rgfA was replaced with a gene that conferred kanamycin resistance (here referred to as ΔrgfCAd; see Materials and Methods). The growth characteristics of the ΔrgfCAd mutant were similar to those of WT A909 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). We next compared the virulence potential of the ΔrgfCAd mutant to that of WT A909 using the neonatal rat sepsis model of infection described previously (27, 31, 35). Interestingly, the 50% moribund dose (MD50; previously known as LD50) estimates of the ΔrgfCAd mutant were 10-fold lower than those for WT A909 (Table 1) (P = 0.012). These results suggest that virulence of the ΔrgfCAd mutant is greater than that of WT A909.

TABLE 1.

Increased virulence of RgfC mutant in the neonatal rat model of GBS sepsisa

| Strain | MD50 (CFU) | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT (A909) | 1.05 × 106 | 4.4 × 105–2.57 × 106 | NA |

| ΔrgfCAd | 1.05 × 105 | 2.98 × 104–3.69 × 105 | 0.012 |

MD50 estimates and confidence intervals (CI) were calculated as described in Materials and Methods. P values reflect the comparison of the value of the mutant strain to that of WT A909. NA, not applicable.

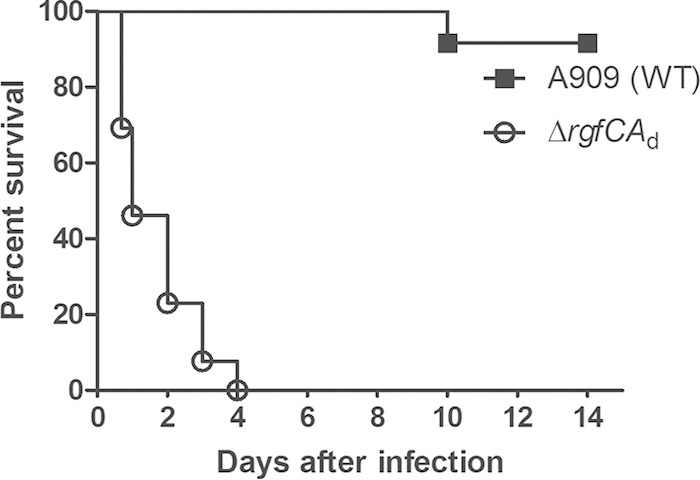

We also examined the ability of the ΔrgfCAd mutant to cause infections in the adult murine model of GBS sepsis and meningitis (32). As the ΔrgfCAd strain demonstrated an increased ability to cause bloodstream infections in neonatal rats, we hypothesized that this strain is more proficient than the WT for infections in adult mice. To test this hypothesis, 3 × 108 CFU of either WT A909 or the ΔrgfCAd mutant were injected into the tail vein of adult CD-1 mice (n = 13), and the mice were monitored up to 15 days for signs of infection as described previously (12, 32). Interestingly, we observed that all mice infected with the ΔrgfCAd mutant succumbed to the infection within 4 days postinfection, in contrast to the WT GBS strain A909, wherein only 1 of 13 inoculated mice succumbed to the infection (Fig. 2). The survival of mice infected with the rgfCAd-deficient strain was statistically significant compared to that of mice infected with the WT (P < 0.0001). Together, these results indicated that the RgfC mutant exhibits increased virulence.

FIG 2.

ΔrgfCAd mutant shows increased virulence in the adult mouse model of GBS infection. Thirteen 6-week-old male CD-1 mice were intravenously injected with 3 × 108 CFU of either the WT or ΔrgfCAd strain. A Kaplan-Meier survival curve shows the percent survival of mice after the infection. Note that all of the mice infected with the ΔrgfCAd mutant succumbed to the infection within 4 days postinoculation, in contrast to the WT (P < 0.0001 by log-rank test).

GBS deficient in RgfC exhibit increased dissemination.

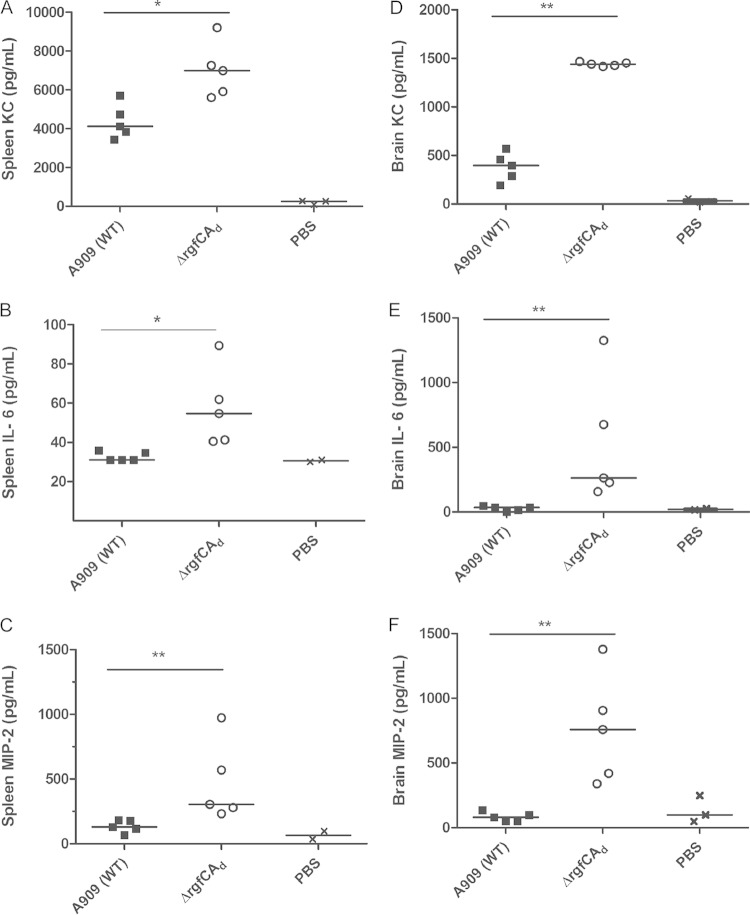

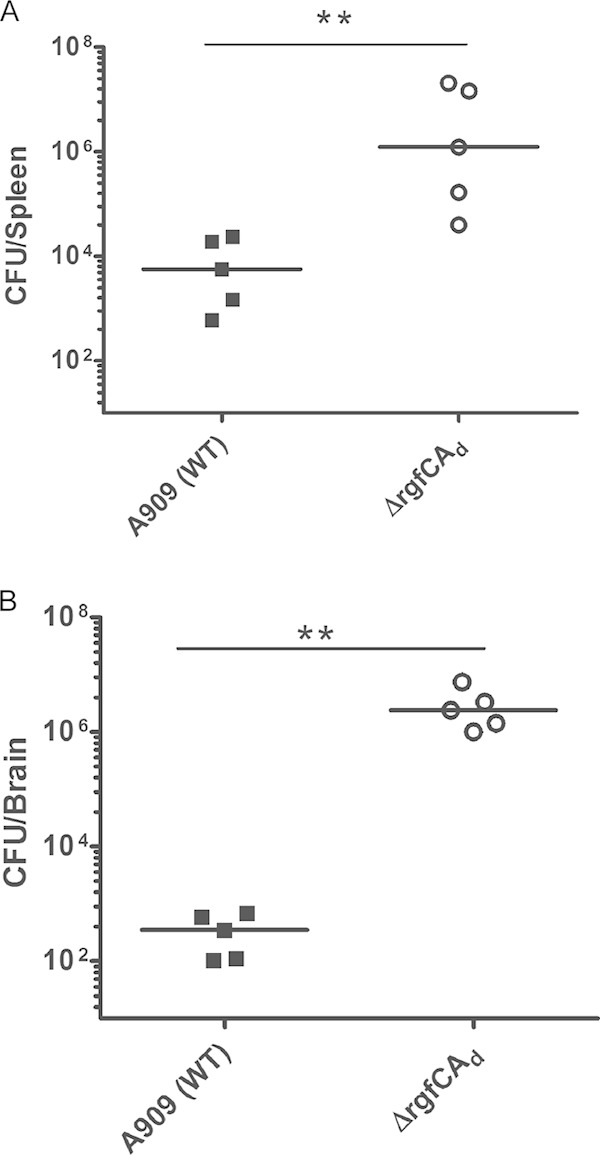

We then compared bacterial dissemination and blood-brain barrier penetration of the ΔrgfCAd mutant to that of WT A909 in vivo. To this end, CD-1 mice (n = 5) were infected with 3 × 107 CFU of the WT or the ΔrgfCAd mutant. At 24 h postinfection, mouse brains and spleen were harvested and the number of CFU were enumerated as described previously (12, 32). These studies indicated that the average number of CFU of the ΔrgfCAd mutant obtained from the spleen and brain of the infected mice were significantly higher than that of WT A909 (Fig. 3A and B) (P = 0.007). We also compared the expression of cytokines, including KC (the murine functional homologue of IL-8), IL-6, and chemokines, such as CXCL2/MIP2, in the spleen and brain of mice infected with the WT or the ΔrgfCAd mutant. The results shown in Fig. 4A to C indicate a significant increase in expression of KC, IL-6, and MIP-2 in spleens of mice infected with the ΔrgfCAd mutant compared to expression in WT A909. Likewise, an increase in KC, IL-6, and MIP-2 expression also was observed in the brains of mice infected with the ΔrgfCAd mutant (Fig. 4D to F). Taken together, these data indicate that the absence of rgfC accelerated GBS systemic infections.

FIG 3.

Increased infection in the spleen and brain of mice infected with the ΔrgfCAd mutant. Five 6-week-old male CD-1 mice were intravenously injected with 3 × 107 CFU of the WT or ΔrgfCAd strain. At approximately 24 h postinfection, brains and spleens were harvested from the infected mice and CFU were enumerated. Note that mice infected with the GBS ΔrgfCAd mutant have increased CFU in the brains and spleens (**, P = 0.007 by Mann-Whitney test).

FIG 4.

Increased chemokine and cytokine expression in spleens of mice infected with the ΔrgfCAd mutant. Five 6-week-old male CD-1 mice were intravenously injected with 3 × 107 CFU of the WT or ΔrgfCAd strain. At approximately 24 h postinfection, spleens and brains were harvested from the infected mice, and the expression of KC (IL-8 equivalent), IL-6, and CXCL2/MIP2 was measured in the homogenates. Note that mice infected with the GBS ΔrgfCAd mutant have increased levels of KC, CXCL2/MIP-2, and IL-6 (*, P = 0.01; **, P = 0.007 by Mann-Whitney test).

RgfC regulation of GBS gene expression.

To determine if the absence of RgfC affected gene expression in GBS A909, we performed microarray analysis using methods described previously (12, 35; also see Materials and Methods). The results shown in Table S2 in the supplemental material indicate that 101 genes showed increased expression, and 115 (excluding rgfC-rgfA) genes showed decreased expression in the A909 ΔrgfCAd mutant. This included an approximately 6-fold increase in expression of the surface-associated serine protease known as CspA that was previously described to promote GBS resistance to opsonophagocytic killing (44, 45) (see Table S2). Furthermore, increased expression of genes encoding the sialic acid-rich capsular polysaccharide (Sia-CPS) critical for GBS virulence (46, 47) also was observed. Other genes that showed increased expression in the ΔrgfCAd strain include genes predicted to be important for metabolic functions (see Table S2). We observed a significant increase in gene expression of metabolite transporters, such as a hydrophobic amino acid uptake system (18- to 50-fold; SAK_1594 to SAK_1597), a branched-chain amino acid uptake system (8.5-fold; SAK_1575), and components of the phosphotransferase system (2.5 to 7-fold; SAK_0399, SAK_1909, SAK_0398, SAK_0400, SAK_0523, SAK_ 0529, SAK_0915, SAK_0530, SAK_0257, and SAK_1920). Increased expression of such genes may facilitate GBS survival and nutrient acquisition during infection and may in part account for the increased CFU observed during systemic infections (Fig. 3). A large number of genes that showed decreased expression in the ΔrgfCAd mutant are proteins of unknown function (see Table S2). Downregulated genes included rgfC-rgfA (SAK_1917-SAK_191718), which served as controls in these analyses. Previous studies on RgfC/A indicated that this TCS regulated the expression of genes encoding fibrinogen binding proteins such as FbsA and FbsB in GBS encoding a functional RgfA (19). The microarray analysis revealed that expression of fbsA and fbsB in the A909 ΔrgfCAd mutant was not significantly different from that of WT A909 and is consistent with observations that adherence and invasion of the A909 ΔrgfCAd mutant to hBMEC was similar to that of WT A909 (see Fig. S2). qRT-PCR analysis confirmed that the expression of genes associated with GBS pathogenesis, i.e., cspA and Sia-CPS genes, such as cpsH, cpsK, neuB, and SAK_1593, was increased in the A909 ΔrgfCAd mutant (Table 2). Complementation of the A909 ΔrgfCAd mutant with a plasmid encoding only RgfC restored transcription of these genes to WT levels (Table 2), whereas complementation with either a plasmid encoding RgfAd or both RgfC and a functional RgfA did not (Table 2). We further observed that the deletion of rgfC-rgfA in GBS encoding a functional RgfA, such as the serotype III strain COH1, did not result in increased virulence or increased expression of cspA and capsular polysaccharide genes compared to the isogenic WT COH1 (see Fig. S3). Collectively, these data suggest that RgfC can have nonspecific activity in the absence of functional RgfA.

TABLE 2.

RgfC regulates expression of capsular polysaccharide and serine protease genes in GBS A909

| Locus | Relative gene expressiona |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A909 ΔrgfCAd | A909 ΔrgfCAd/pRgfC | A909 ΔrgfCAd/pRgfAd | A909 ΔrgfCAd/pRgfCAb | |

| cspA | 7.28 ± 1.1 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 6.06 ± 1.03 | 10.37 ± 4.4 |

| cpsH | 10.14 ± 2.05 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 10.8 ± 1.7 | 14.75 ± 5.3 |

| cpsK | 8.2 ± 3.28 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 9.02 ± 1.2 | 13.37 ± 3.2 |

| neuB | 9.65 ± 1.01 | 1.36 ± 0.24 | 8.7 ± 2.45 | 9.6 ± 3.3 |

| SAK_1593 | 25.49 ± 3.08 | 0.74 ±.24 | 30 ± 4.48 | 20.5 ± 4.14 |

qRT-PCR was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Gene expression is denoted as fold difference relative to the WT GBS strain A909. Standard deviations are indicated.

A909 ΔrgfCAd/pRgfCA indicates a complementing plasmid encoding both RgfC and RgfA without the premature stop codon in RgfA.

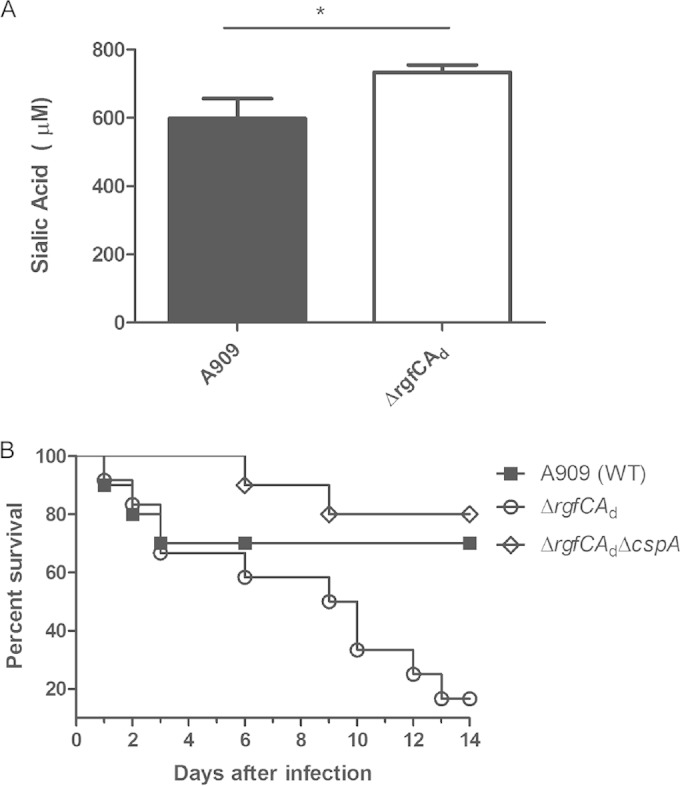

Sia-CPS levels in the A909 ΔrgfCAd mutant.

Sialylation of the GBS capsular polysaccharide is critical for GBS bloodstream infections and pathogenesis (46, 48). To determine if the increase in gene expression of the capsular polysaccharide operon correlated with increased sialic acid levels in the A909 ΔrgfCAd mutant, we compared sialic acid levels in cell surface-associated capsular polysaccharide using HPLC as described previously (42, 49). The results shown in Fig. 5A indicate that sialic acid levels were higher in the ΔrgfCAd mutant than in WT A909 (P < 0.01), which could in part contribute to the enhanced virulence of the ΔrgfCAd mutant. Increased sialic acid levels were not observed in the COH1 ΔrgfCA mutant (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

FIG 5.

Effect of increased expression of Sia-CPS and CspA in ΔrgfC mutant. (A) Quantity of sialic acid associated with the capsular polysaccharide of each GBS strain was measured using HPLC. Data indicate that sialic acid levels are higher in the ΔrgfCAd mutant (n = 3; P = 0.01 by Student's t test). (B) Ten 6-week-old male CD-1 mice were intravenously injected with 3 × 107 to 3 × 108 CFU of the WT A909, ΔrgfCAd, or ΔrgfCAd ΔcspA strain. The Kaplan-Meier survival curve shows percent survival of mice after the infection. Note that virulence of the ΔrgfCAd mutant is restored to WT levels in the ΔrgfCAd ΔcspA double mutant (P = 0.004 by log-rank test).

Role of CspA in virulence potential of ΔrgfCAd mutant.

We examined whether the increase in expression of CspA contributed to the increase in virulence potential of the rgfCAd mutant. To test this possibility, we constructed a double mutant that was deficient for both CspA and rgfCAd in GBS A909 (a ΔrgfCAd ΔcspA strain; see Materials and Methods). Subsequently, the virulence potential of the ΔrgfCAd ΔcspA double mutant was compared to those of the WT and ΔrgfCAd strains using the adult murine model of GBS infection described previously. The results shown in Fig. 5B indicate that the increase in virulence of the rgfCAd mutant was diminished in the ΔrgfCAd ΔcspA double mutant (P = 0.004). These data indicate that the increase in CspA expression contributes to the increase in virulence potential of the RgfC mutant.

RgfC regulation of protein phosphorylation.

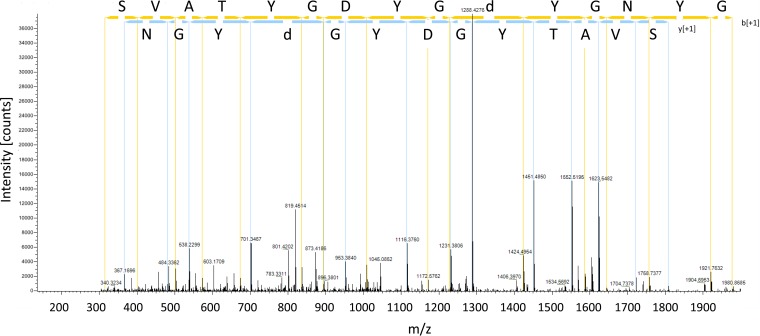

To determine if the absence of RgfC altered protein phosphorylation, we performed phosphopeptide enrichment analysis to identify peptides/proteins that were differentially phosphorylated between WT A909, the rgfCAd mutant, and the complemented strain carrying pRgfC (see Materials and Methods). Although the phosphoproteomic analysis that we utilized is optimized to enrich and identify S/T/Y phosphorylation, we minimized acid treatment to also identify potential D/H phosphosites. The results obtained from these analyses are shown in Table 3. Table 3 indicates aspartate phosphopeptides that were identified only in RgfC-expressing strains and correspond to a transcriptional regulator and the tyrosine kinase CpsD (Fig. 6 shows a sample peptide sequence/spectrum). These results suggest that RgfC directly or indirectly regulates phosphorylation of these peptides/proteins. Also, it is worth noting that two aspartate phosphopeptides corresponding to a methyltransferase were identified in the RgfCAd mutant (Table 3), suggesting that RgfC influences dephosphorylation of the methyltransferase in GBS A909. Interestingly, we also observed changes in C/S/T/Y phosphorylation between RgfC-proficient and -deficient strains. This included 3 phosphopeptides in RgfC-proficient strains and 12 in the RgfC-deficient strain (Table 3). Further studies are essential to determine how these phosphorylation/dephosphorylation events regulate protein function and for a better understanding of the role of RgfC in GBS.

TABLE 3.

Differential protein phosphorylation between WT GBS and the ΔrgfCAd mutanta

| Phosphopeptide | Protein | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Aspartate phosphopeptides unique to RgfC expressing strains (A909 and/or the ΔrgfCAd/pRgfC complemented strain) | ||

| AdFVDILQNPSLMDQLPPLDMMK | SAK_0723 | XRE family transcriptional regulator |

| VSESVATYGDYGdYGNYGK | SAK_1259 | CpsD/tyrosine kinase |

| Aspartate phosphopeptides unique to ΔrgfCAd mutant | ||

| VEdCSVLDIGTGSGAIAISLK | SAK_1162 | HemK family modification methylase |

| DLIFFVdER | ||

| S/T/Y/C phosphopeptides unique to WT A909 and/or the ΔrgfCAd/pRgfC complemented strain | ||

| GLMMGVAAMVTLLAPAVGPTYGGVIsGMLGWK | SAK_1173 | H+ antiporter-2 (DHA2) family protein |

| QKQVDLCQNcyQIIK | SAK_0590 | ATP-dependent Clp protease, ATP-binding subunit ClpE |

| LVGAPPGYVGYEEAGQLtEKVR | ||

| S/T/Y phosphopeptides unique to ΔrgfCAd mutant | ||

| QVILsEASR | SAK_0420 | Enoyl-(acyl-carrier-protein) reductase II |

| ILYLQEIFAEEMsK | SAK_1017 | Hypothetical protein SAK_1017 |

| yFNLEDK | ||

| LEsEGIHVR | SAK_1756 | Transketolase |

| FVLSAGHGsALLYSLLHLAGYDLSIDDLK | ||

| KVSYVtIR | SAK_0620 | Hypothetical protein SAK_0620 |

| ELyIMIK | ||

| QSGsIPEGTVIGDGK | SAK_0435 | PTS mannose/fructose/sorbose family transporter subunit IIA |

| LLHGQVAtAWTPASK | ||

| VKIsAQDEASNLMGK | SAK_0586 | Cell division protein DivIVA |

| ISAQDEAsNLMGK | ||

| DLSGVTQTQIsLPFITAGSAGPLHLEMSLSR | SAK_0147 | Molecular chaperone DnaK |

Phosphopeptide enrichment was performed as described previously (50; also see Materials and Methods), and peptides were identified by mass spectrometric analyses. The phosphorylation site was determined by phosphoRS. The phosphorylated aspartate, threonine, serine, tyrosine, or cysteine residue is indicated by d, t, s, y, or c, respectively. SAK numbers correspond to the open reading frame of the gene in the GBS A909 genome (9). The proteins below were identified in two independent phosphopeptide enrichment analyses.

FIG 6.

Representative mass spectrum of an aspartate phosphopeptide unique to RgfC expressing GBS. The peptide, VSESVATYGDYGdYGNYGK from CspD, was identified uniquely in the RgfC-expressing strains (Table 3). The fragmentation of the precursor ion gives rise to peaks that can be mapped to the peptide sequence shown above the spectrum. In particular, both the y ion sequence and b ion sequence indicate the presence of a phosphorylated aspartate residue. This phosphorylated residue is highlighted by a lowercase “d” in the sequence.

Collectively, our studies indicate that RgfC functions as a nonspecific or orphan kinase in GBS strains with a mutation in RgfA, and this has an impact on GBS virulence. A detailed understanding of two-component regulation is necessary for the evaluation of either histidine kinases or cognate response regulators as an antimicrobial target(s) in strategies to prevent bacterial infections in humans.

DISCUSSION

Signaling systems are critical for bacterial adaptation to changing environmental conditions. As GBS encounters diverse niches in its life cycle, it is likely that the approximately 20 TCS encoded by GBS sense diverse environmental signals and contribute to bacterial environmental adaptation. However, our understanding of environmental signals that are sensed by these various TCS and mechanisms of gene regulation is incomplete. The sensor histidine kinase/response regulator RgfC/A initially was identified as regulating the expression of genes such as fbsA and fbsB, which are important for GBS binding to extracellular matrix components such as fibrinogen (19, 20). However, the presence of a spontaneous mutation resulting in premature truncation of the response regulator rgfA in certain GBS strains and regulation of these genes by CovR/S (12) prompted us to determine if RgfC function was abolished in strains lacking a functional RgfA. We provide evidence that deletion of rgfC in strains encoding a nonfunctional RgfA resulted in altered expression of >200 genes and included critical virulence components, such as the serine protease CspA and the sialic acid capsular polysaccharide. Control of these genes suggests that RgfC regulation of gene expression is altered in the absence of a functional RgfA and that sensor kinase has a broader role in GBS virulence than previously appreciated. Support for this observation also is provided by the recent findings of Faralla et al. (21). The authors reported that the deletion of RgfC in the GBS serotype V strain CJB11, which encodes a functional RgfA, resulted in increased mortality of mice without significant differences in bacterial dissemination (21). Notably, only 2 genes showed altered transcription in the RgfC mutant compared to WT GBS CJB11 (see Δrr17 in reference 21). Our studies using GBS COH1 indicate that an RgfCA mutant does not exhibit altered virulence compared to the isogenic WT strains (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Collectively, these observations suggest that RgfC regulation in GBS virulence is influenced by the presence or absence of a functional RgfA and strain-specific genes.

Expression of the sialic acid capsular polysaccharide is critical for GBS virulence (46, 48). Our results suggest that RgfC regulates production of the GBS capsule at both the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels. Apart from changes in transcription of genes in the capsule operon, we identified aspartate phosphopeptides corresponding to the tyrosine kinase CpsD (Table 3 and Fig. 6). While tyrosine phosphorylation of CpsD at the C-terminal YGX motif has been shown previously to regulate capsule polymer length in Streptococcus pneumoniae (51), the role of tyrosine phosphorylation of CpsD in GBS capsule has not been established specifically. As aspartate phosphorylation of CpsD was observed at the YGD motif that also contains the putative tyrosine phosphorylation site (51), we speculate that aspartate phosphorylation impacts tyrosine phosphorylation and vice versa, as previously shown with serine/threonine and aspartate phosphorylation for the GBS response regulator CovR (13). Further studies on CpsD will establish the role of tyrosine and aspartate phosphorylation on GBS capsule production and virulence.

Interestingly, we also identified an aspartate phosphopeptide corresponding to a transcriptional regulator as a potential target of RgfC (Table 3). Although this regulator is annotated as a hypothetical protein in the A909 genome, it shows homology to the xenobiotic response element family of transcriptional regulators. The potential for this protein to be an alternative DNA binding response regulator of RgfC in the absence of RgfA is an exciting hypothesis that remains to be investigated.

The signal(s) sensed by RgfC remains unknown. The microarray data indicate that the deletion of RgfC results in a strong increase in transcripts of the phosphotransferase system (PTS) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), which aids in the uptake of carbohydrates, such as fructose, mannose, and sucrose, into the cell. Additionally, transcription levels are increased for uptake machinery for both hydrophobic and polar amino acids. This suggests that RgfC responds to altered carbon metabolite levels, and concurrent with this observation, we observed that the ΔrgfCAd strain expressed greater levels of the carbon starvation protein CtsA. In E. coli, this protein is thought to aid in the utilization of peptides during carbon starvation (52). Thus, another purpose of the increased expression of serine protease CspA is to increase the availability of carbon in the form of peptides cleaved by this protease. Interestingly, downregulation of the PTS recently was observed with GBS deficient in FspS/R (21), suggesting that TCS have differing roles in GBS metabolism.

It remains unclear if any evolutionary or selective advantage is conferred to GBS by the stop codon mutation in RgfA. As the increased expression of virulence factors often can be associated with invasive disease, we speculate that decreased expression of virulence factors (e.g., due to the presence of RgfC in strains lacking a functional RgfA) promotes the existence of GBS in commensal niches, such as the rectovaginal tract of adult humans. Reports of spontaneous mutations in TCS have been described in many bacteria that affect various phenotypic characteristics. For example, mutations in TCS have been shown to confer antibiotic resistance in certain strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterococcus faecium (53–56). Clinical isolates containing mutations in the TCS CovR/S (also known as CsrR/S) have been reported in GBS and group A streptococci (GAS) (57, 58). As this TCS regulates the expression of important virulence genes, mutation(s) in this locus significantly affects pathogenesis (11, 12, 59). Further studies are needed to elucidate the RgfC phosphosignaling cascade in GBS. Nevertheless, our studies indicate that the acquisition of spontaneous mutations in signaling systems alters virulence gene expression in novel ways and provides insight into new mechanisms of gene regulation that can occur in bacterial organisms.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Francesco Bedogni and Rebecca Hodge (Seattle Children's Research Institute) for their expert advice in harvesting the mouse brain. We thank James Connelly, Melissa de los Reyes, Mason Craig Bailey, and Nguyen-Thao BinhTran for technical support.

This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health, grants R01AI100989, R56 AI070749, R01AI088255, and R21AI109222 to L.R., grant R01NS051247 from the NINDS/NIH to K.S.D., and RO1GM088317 to W.A.T. Support for C.W. was provided by an NIH training grant (T32 AI07509; principal investigator, Lee Ann Campbell). We also thank the Center for Childhood Infections and Prematurity Research at Seattle Children's Research Institute for strategic funds.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.02738-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoch JA, Silhavy TJ (ed). 1995. Two-component signal transduction. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beier D, Gross R. 2006. Regulation of bacterial virulence by two-component systems. Curr Opin Microbiol 9:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calva E, Oropeza R. 2006. Two-component signal transduction systems, environmental signals, and virulence. Microb Ecol 51:166–176. doi: 10.1007/s00248-005-0087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassler B, Losick R. 2006. Bacterially speaking. Cell 125:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novick RP. 2003. Autoinduction and signal transduction in the regulation of staphylococcal virulence. Mol Microbiol 48:1429–1449. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker CJ, Edwards MW. 1995. Group B streptococcal infections, p 980–1054. In Remington JS, Klein JO, Wilson CB, Baker CJ (ed), Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn infant. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doran KS, Nizet V. 2004. Molecular pathogenesis of neonatal group B streptococcal infection: no longer in its infancy. Mol Microbiol 54:23–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajagopal L. 2009. Understanding the regulation of group B streptococcal virulence factors. Future Microbiol 4:201–221. doi: 10.2217/17460913.4.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tettelin H, Masignani V, Cieslewicz MJ, Donati C, Medini D, Ward NL, Angiuoli SV, Crabtree J, Jones AL, Durkin AS, Deboy RT, Davidsen TM, Mora M, Scarselli M, Margarit y Ros I, Peterson JD, Hauser CR, Sundaram JP, Nelson WC, Madupu R, Brinkac LM, Dodson RJ, Rosovitz MJ, Sullivan SA, Daugherty SC, Haft DH, Selengut J, Gwinn ML, Zhou L, Zafar N, Khouri H, Radune D, Dimitrov G, Watkins K, O'Connor KJ, Smith S, Utterback TR, White O, Rubens CE, Grandi G, Madoff LC, Kasper DL, Telford JL, Wessels MR, Rappuoli R, Fraser CM. 2005. Genome analysis of multiple pathogenic isolates of Streptococcus agalactiae: implications for the microbial “pan-genome.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:13950–13955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506758102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang SM, Cieslewicz MJ, Kasper DL, Wessels MR. 2005. Regulation of virulence by a two-component system in group B streptococcus. J Bacteriol 187:1105–1113. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.3.1105-1113.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamy MC, Zouine M, Fert J, Vergassola M, Couve E, Pellegrini E, Glaser P, Kunst F, Msadek T, Trieu-Cuot P, Poyart C. 2004. CovS/CovR of group B streptococcus: a two-component global regulatory system involved in virulence. Mol Microbiol 54:1250–1268. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lembo A, Gurney MA, Burnside K, Banerjee A, de los Reyes M, Connelly JE, Lin WJ, Jewell KA, Vo A, Renken CW, Doran KS, Rajagopal L. 2010. Regulation of CovR expression in group B Streptococcus impacts blood-brain barrier penetration. Mol Microbiol 77:431–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin WJ, Walthers D, Connelly JE, Burnside K, Jewell KA, Kenney LJ, Rajagopal L. 2009. Threonine phosphorylation prevents promoter DNA binding of the group B Streptococcus response regulator CovR. Mol Microbiol 71:1477–1495. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06616.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajagopal L, Vo A, Silvestroni A, Rubens CE. 2006. Regulation of cytotoxin expression by converging eukaryotic-type and two-component signalling mechanisms in Streptococcus agalactiae. Mol Microbiol 62:941–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patras KA, Wang NY, Fletcher EM, Cavaco CK, Jimenez A, Garg M, Fierer J, Sheen TR, Rajagopal L, Doran KS. 2013. Group B Streptococcus CovR regulation modulates host immune signalling pathways to promote vaginal colonization. Cell Microbiol 15:1154–1167. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poyart C, Pellegrini E, Marceau M, Baptista M, Jaubert F, Lamy MC, Trieu-Cuot P. 2003. Attenuated virulence of Streptococcus agalactiae deficient in D-alanyl-lipoteichoic acid is due to an increased susceptibility to defensins and phagocytic cells. Mol Microbiol 49:1615–1625. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quach D, van Sorge NM, Kristian SA, Bryan JD, Shelver DW, Doran KS. 2009. The CiaR response regulator in group B Streptococcus promotes intracellular survival and resistance to innate immune defenses. J Bacteriol 191:2023–2032. doi: 10.1128/JB.01216-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rozhdestvenskaya AS, Totolian AA, Dmitriev AV. 2010. Inactivation of DNA-binding response regulator Sak189 abrogates beta-antigen expression and affects virulence of Streptococcus agalactiae. PLoS One 5:e10212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al Safadi R, Mereghetti L, Salloum M, Lartigue MF, Virlogeux-Payant I, Quentin R, Rosenau A. 2011. Two-component system RgfA/C activates the fbsB gene encoding major fibrinogen-binding protein in highly virulent CC17 clone group B Streptococcus. PLoS One 6:e14658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spellerberg B, Rozdzinski E, Martin S, Weber-Heynemann J, Lutticken R. 2002. rgf encodes a novel two-component signal transduction system of Streptococcus agalactiae. Infect Immun 70:2434–2440. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.5.2434-2440.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faralla C, Metruccio MM, De Chiara M, Mu R, Patras KA, Muzzi A, Grandi G, Margarit I, Doran KS, Janulczyk R. 2014. Analysis of two-component systems in group B Streptococcus shows that RgfAC and the novel FspSR modulate virulence and bacterial fitness. mBio 5:e00870–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00870-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madoff LC, Michel JL, Kasper DL. 1991. A monoclonal antibody identifies a protective C-protein alpha-antigen epitope in group B streptococci. Infect Immun 59:204–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin TR, Rubens CE, Wilson CB. 1988. Lung antibacterial defense mechanisms in infant and adult rats: implications for the pathogenesis of group B streptococcal infections in neonatal lung. J Infect Dis 157:91–100. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okada N, Geist RT, Caparon MG. 1993. Positive transcriptional control of mry regulates virulence in the group A streptococcus. Mol Microbiol 7:893–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horton RM. 1995. PCR-mediated recombination and mutagenesis. SOEing together tailor-made genes. Mol Biotechnol 3:93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaffin DO, Beres SB, Yim HH, Rubens CE. 2000. The serotype of type Ia and III group B streptococci is determined by the polymerase gene within the polycistronic capsule operon. J Bacteriol 182:4466–4477. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.16.4466-4477.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajagopal L, Clancy A, Rubens CE. 2003. A eukaryotic type serine/threonine kinase and phosphatase in Streptococcus agalactiae reversibly phosphorylate an inorganic pyrophosphatase and affect growth, cell segregation, and virulence. J Biol Chem 278:14429–14441. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212747200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Husmann LK, Scott JR, Lindahl G, Stenberg L. 1995. Expression of the Arp protein, a member of the M protein family, is not sufficient to inhibit phagocytosis of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect Immun 63:345–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaffin DO, Rubens CE. 1998. Blue/white screening of recombinant plasmids in Gram-positive bacteria by interruption of alkaline phosphatase gene (phoZ) expression. Gene 219:91–99. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00396-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Research Council. 2011. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed. National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones AL, Knoll KM, Rubens CE. 2000. Identification of Streptococcus agalactiae virulence genes in the neonatal rat sepsis model using signature-tagged mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol 37:1444–1455. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doran KS, Liu GY, Nizet V. 2003. Group B streptococcal beta-hemolysin/cytolysin activates neutrophil signaling pathways in brain endothelium and contributes to development of meningitis. J Clin Investig 112:736–744. doi: 10.1172/JCI17335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doran KS, Engelson EJ, Khosravi A, Maisey HC, Fedtke I, Equils O, Michelsen KS, Arditi M, Peschel A, Nizet V. 2005. Blood-brain barrier invasion by group B Streptococcus depends upon proper cell-surface anchoring of lipoteichoic acid. J Clin Investig 115:2499–2507. doi: 10.1172/JCI23829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stins MF, Prasadarao NV, Zhou J, Arditi M, Kim KS. 1997. Bovine brain microvascular endothelial cells transfected with SV40-large T antigen: development of an immortalized cell line to study pathophysiology of CNS disease. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 33:243–247. doi: 10.1007/s11626-997-0042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burnside K, Lembo A, Harrell MI, Gurney M, Xue L, Binhtran NT, Connelly JE, Jewell KA, Schmidt BZ, de Los Reyes M, Tao WA, Doran KS, Rajagopal L. 2011. Serine/threonine phosphatase Stp1 mediates post-transcriptional regulation of hemolysin, autolysis, and virulence of group B Streptococcus. J Biol Chem 286:44197–44210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.313486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silvestroni A, Jewell KA, Lin WJ, Connelly JE, Ivancic MM, Tao WA, Rajagopal L. 2009. Identification of serine/threonine kinase substrates in the human pathogen group B streptococcus. J Proteome Res 8:2563–2574. doi: 10.1021/pr900069n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iliuk AB, Martin VA, Alicie BM, Geahlen RL, Tao WA. 2010. In-depth analyses of kinase-dependent tyrosine phosphoproteomes based on metal ion-functionalized soluble nanopolymers. Mol Cell Proteomics 9:2162–2172. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.000091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iliuk A, Tao WA. 2009. Quantitative phospho-proteomics based on soluble nanopolymers. Methods Mol Biol 527:117–129, ix. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-834-8_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olsen JV, Blagoev B, Gnad F, Macek B, Kumar C, Mortensen P, Mann M. 2006. Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks. Cell 127:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taus T, Kocher T, Pichler P, Paschke C, Schmidt A, Henrich C, Mechtler K. 2011. Universal and confident phosphorylation site localization using phosphoRS. J Proteome Res 10:5354–5362. doi: 10.1021/pr200611n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B 57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones AL, Needham RH, Clancy A, Knoll KM, Rubens CE. 2003. Penicillin-binding proteins in Streptococcus agalactiae: a novel mechanism for evasion of immune clearance. Mol Microbiol 47:247–256. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lancefield RC, McCarty M, Everly WN. 1975. Multiple mouse-protective antibodies directed against group B streptococci. Special reference to antibodies effective against protein antigens. J Exp Med 142:165–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harris TO, Shelver DW, Bohnsack JF, Rubens CE. 2003. A novel streptococcal surface protease promotes virulence, resistance to opsonophagocytosis, and cleavage of human fibrinogen. J Clin Investig 111:61–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI16270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bryan JD, Shelver DW. 2008. Streptococcus agalactiae CspA is a serine protease that inactivates chemokines. J Bacteriol 191:1847–1854. doi: 10.1128/JB.01124-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wessels MR, Rubens CE, Benedi VJ, Kasper DL. 1989. Definition of a bacterial virulence factor: sialylation of the group B streptococcal capsule. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 86:8983–8987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.22.8983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rubens CE, Wessels MR, Heggen LM, Kasper DL. 1987. Transposon mutagenesis of type III group B streptococcus: correlation of capsule expression with virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 84:7208–7212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marques MB, Kasper DL, Pangburn MK, Wessels MR. 1992. Prevention of C3 deposition by capsular polysaccharide is a virulence mechanism of type III group B streptococci. Infect Immun 60:3986–3993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chaffin DO, Mentele LM, Rubens CE. 2005. Sialylation of group B streptococcal capsular polysaccharide is mediated by cpsK and is required for optimal capsule polymerization and expression. J Bacteriol 187:4615–4626. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.13.4615-4626.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burnside K, Lembo A, de Los Reyes M, Iliuk A, Binhtran NT, Connelly JE, Lin WJ, Schmidt BZ, Richardson AR, Fang FC, Tao WA, Rajagopal L. 2010. Regulation of hemolysin expression and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus by a serine/threonine kinase and phosphatase. PLoS One 5:e11071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bender MH, Cartee RT, Yother J. 2003. Positive correlation between tyrosine phosphorylation of CpsD and capsular polysaccharide production in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol 185:6057–6066. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.20.6057-6066.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schultz JE, Matin A. 1991. Molecular and functional characterization of a carbon starvation gene of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol 218:129–140. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90879-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moscoso M, Domenech M, Garcia E. 28 June 2010. Vancomycin tolerance in clinical and laboratory Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates depends on reduced enzyme activity of the major LytA autolysin or cooperation between CiaH histidine kinase and capsular polysaccharide. Mol Microbiol doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Katayama Y, Murakami-Kuroda H, Cui L, Hiramatsu K. 2009. Selection of heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus by imipenem. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:3190–3196. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00834-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lau CH, Fraud S, Jones M, Peterson SN, Poole K. 2013. Mutational activation of the AmgRS two-component system in aminoglycoside-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:2243–2251. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00170-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Depardieu F, Courvalin P, Msadek T. 2003. A six amino acid deletion, partially overlapping the VanSB G2 ATP-binding motif, leads to constitutive glycopeptide resistance in VanB-type Enterococcus faecium. Mol Microbiol 50:1069–1083. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sendi P, Johansson L, Dahesh S, Van-Sorge NM, Darenberg J, Norgren M, Sjolin J, Nizet V, Norrby-Teglund A. 2009. Bacterial phenotype variants in group B streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Emerg Infect Dis 15:223–232. doi: 10.3201/eid1502.080990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miller AA, Engleberg NC, DiRita VJ. 2001. Repression of virulence genes by phosphorylation-dependent oligomerization of CsrR at target promoters in S. pyogenes. Mol Microbiol 40:976–990. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heath A, DiRita VJ, Barg NL, Engleberg NC. 1999. A two-component regulatory system, CsrR-CsrS, represses expression of three Streptococcus pyogenes virulence factors, hyaluronic acid capsule, streptolysin S, and pyrogenic exotoxin B. Infect Immun 67:5298–5305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.