Abstract

Host-adapted Gram-negative bacterial pathogens from the Pasteurellaceae, Neisseriaceae, and Moraxellaceae families normally reside in the upper respiratory or genitourinary tracts of their hosts and rely on utilizing iron from host transferrin (Tf) for growth and survival. The surface receptor proteins that mediate this critical iron acquisition pathway have been proposed as ideal vaccine targets due to the critical role that they play in survival and disease pathogenesis in vivo. In particular, the surface lipoprotein component of the receptor, Tf binding protein B (TbpB), had received considerable attention as a potential antigen for vaccines in humans and food production animals but this has not translated into the series of successful vaccine products originally envisioned. Preliminary immunization experiments suggesting that host Tf could interfere with development of the immune response prompted us to directly address this question with site-directed mutant proteins defective in binding Tf. Site-directed mutants with dramatically reduced binding of porcine transferrin and nearly identical structure to the native proteins were prepared. A mutant Haemophilus parasuis TbpB was shown to induce an enhanced B-cell and T-cell response in pigs relative to native TbpB and provide superior protection from infection than the native TbpB or a commercial vaccine product. The results indicate that binding of host transferrin modulates the development of the immune response against TbpBs and that strategies designed to reduce or eliminate binding can be used to generate superior antigens for vaccines.

INTRODUCTION

A common adaptation among several highly host-adapted Gram-negative species from the Pasteurellaceae, Neisseriaceae, and Moraxellaceae families that exclusively reside in the upper respiratory tract is the ability to directly bind host transferrin (Tf) and use it as a source of iron for growth (1, 2). Iron-loaded transferrin is captured by surface receptors that remove iron from Tf and transport the iron across the outer membrane, where it is subsequently transported into the cell through a periplasm binding protein-dependent ABC (ATP binding cassette) transport system. Early observations that the interaction of the bacterial receptors with Tf was highly host specific (3–5) provided a rational explanation for the strict host specificity of these bacterial pathogens.

The initial capture of iron-loaded Tf is mediated by a surface lipoprotein, Tf binding protein B (TbpB), which consists of two structurally equivalent lobes preceded by a relatively long anchoring peptide that would allow the protein to extend far from the outer membrane surface (6). The role of TbpB is to capture the iron-loaded form of Tf and deliver it to Tf binding protein A (TbpA), the integral outer membrane protein that serves as the channel for transporting iron across the outer membrane. The structure of a Tf-TbpB complex has recently been determined (7), revealing that that the process of binding iron-loaded Tf does not involve substantial changes in the conformation of the TbpB N-lobe or the Tf C-lobe and effectively traps the Tf C-lobe in the iron-loaded state. In contrast, binding of Tf to TbpA involves substantial conformational changes in the TbpB C-lobe, resulting in substantial separation of the C1 and C2 domains that both contribute ligands for coordination of iron (8). In the absence of structural information for TbpA alone one can only speculate on the conformational changes that occur in the surface loop structures of TbpA upon binding Tf.

The process by which TbpB mediates the initial capture of iron-loaded Tf and transfers it to TbpA is only partly understood. The variable association of the anchoring peptide with the C-lobe (9) and its requirement for formation of the ternary complex (10) may indicate that modulation of the anchor peptide may be involved. Although structural models can be developed for the ternary complex (2, 8), these are not based on high-resolution structural information for the actual complex, and how TbpB maintains an interaction with Tf upon domain separation is still not resolved. Similarly, the process by which iron is released and transported across the outer membrane and the degree to which different regions of TbpB participate in this process is uncertain.

Since the first discovery of the bacterial Tf receptors (11, 12) and the demonstration of their exquisite host specificity (4), they were postulated to be essential for survival in the native host and thus potentially ideal vaccine targets. The importance of the receptor proteins has been confirmed in a male gonococcal infection model (13) and a pig infection model with Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae (14). Notably, the latter study demonstrated that the TbpB receptor protein was essential for survival and disease causation, in spite of the fact that growth under laboratory conditions with Tf as the exogenous iron source was not dependent upon the presence of TbpB.

The Tf receptor proteins, particularly TbpB, from Neisseria meningitidis were shown to have suitable properties as vaccine antigens (15, 16). Subsequent studies evaluated the ability of TbpBs to induce a cross-protective response (17) and ultimately led to the conclusion that a vaccine comprised of three representative TbpBs could potentially provide cross-protection against the majority of potential disease isolates, thus warranting further investigation. Since the lipidated recombinant form of TbpB was capable of inducing a strong antibody response in the absence of added adjuvant in animal experiments, phase I trials were performed with recombinant protein alone (18). The somewhat disappointing results in this trial ultimately led to abandoning the development of a commercial product, but considerable uncertainty remained regarding the factors responsible.

Since the Tf receptors are a common adaptation for a number of human and animal pathogens, studies have been performed to examine their potential as vaccine antigens against several other human and veterinary pathogens (19–23). None of the studies with other human pathogens (19, 22, 23) have extended to further trials in humans, and thus they have not provided further insights into the performance of intact TbpB antigens in the natural host. Studies evaluating the potential of Tf receptor based vaccines in food production animals (20, 21, 24) were performed directly in the natural host and thus did not lead to questions regarding their relative performance in the natural and heterologous host.

The present study was initiated to exam whether the suboptimal performance of TbpB-based vaccines could be due to the presence of host Tf during systemic (parenteral) immunization interfering with the optimal development of an anti-TbpB antibody response and, if so, to develop strategies for overcoming the suboptimal immune response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of recombinant TbpB and TbpB subfragments.

Recombinant proteins were expressed and purified essentially as described previously (6, 9). The genes encoding TbpB or mutant TbpB from various species were cloned in to a T7 expression vector encoding an N-terminal maltose binding protein fusion partner containing a polyhistidine tag and a TEV cleavage site preceding the region encoding the mature TbpB protein. The genes comprised the region encoding (i) amino acids 36 to 528 of the mature TbpB (TbpB36–528) from A. pleuropneumoniae strain H49 and (ii) TbpB26–528 from A. pleuropneumoniae strain H87, TbpB27–577 from Actinobacillus suis strain H57, or TbpB20–537 from Haemophilus parasuis Nagasaki strain. After expression and cell disruption, the recombinant fusion proteins were isolated from the crude lysate supernatant by Ni-NTA chromatography. The purified fusion proteins were treated with TEV protease, and the mixtures were subjected to one or more rounds of Ni-NTA chromatography and Q-Sepharose chromatography to achieve purity.

Protein crystallization.

Purified wild-type or mutant TbpB20–537 from H. parasuis Nagasaki strain (Hp5 TbpBs) and N-lobe ApH49 TbpB were initially screened against the MCSG I-IV suite commercial screen using hanging-drop vapor diffusion at 10 mg/ml. Hp5 TbpB W176A single-mutant and the Y167A W176 double-mutant crystals were, respectively, observed in condition 1 (0.16 M sodium acetate [pH 6.5], 80 mM calcium cacodylate, 23% PEG 3350, 15% glycerol) and condition 2 (80 mM potassium phosphate monobasic [pH 6.5], 18% PEG 8000, 20% glycerol) with a 1:1 ratio sitting drop at 20°C, yielding crystals in space groups P21 and C2, respectively. The N-lobe domain of ApH49 carrying the F171A mutation was crystallized in 0.1 M Bis-Tris (pH 5.5), 0.4 M lithium sulfate, 17% PEG 3350, and 20% glycerol to yield crystals in space group P61. AsH57 and ApH87 TbpBs carrying the single point mutation Y63A, Y95A, Y174A, or R179E were crystallized from the previously reported precipitant conditions as determined for the wild-type AsH57 and ApH87 TbpBs (9). Unit cell dimensions and statistics are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics for the Hp5, ApH49, AsH57, and ApH87 TbpB mutants examined in this studya

| Parameter | Hp5 TbpB (W176A) | Hp5 TbpB (Y167A, W176A) | ApH49 TbpB (F171A) | AsH57 TbpB (Y63A) | ApH87 TbpB (Y95A) | ApH87 TbpB (Y174A) | ApH87 TbpB (R179E) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDB code | 4O4U | 4O4X | 4O3X | 4O3W | 4O3Z | 4O49 | 4O3Y |

| Data collection | |||||||

| Space group | P21 | C2 | P61 | P21 | C2221 | C2221 | C2221 |

| Cell dimensions | |||||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 81.0, 135.6, 103.9 | 239.8, 42.2, 114.0 | 41.3, 41.3, 234.0 | 90.8, 74.5, 106.6 | 135.1, 149.2, 90.9 | 132.8, 150.4, 93.4 | 134.7, 149.2, 91.0 |

| a, b, c (°) | 90, 100, 90 | 90, 92.4, 90 | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 105, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 48–2.64 (2.74–2.64) | 42–2.9 (3.0–2.9) | 35–2.5 (2.6–2.5) | 46–2.1 (2.16–2.1) | 46–2.9 (3.0–2.9) | 46–2.5 (2.6–2.5) | 46–2.6 (2.7–2.6) |

| I/σI | 14.6 (0.92) | 19.0 (1.8) | 25.2 (1.5) | 17.6 (3.6) | 26.1 (3.9) | 22.9 (3.3) | 18.1 (1.7) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.5 (99.8) | 93.4 (95.1) | 98.8 (88.5) | 91.4 (59.2) | 99.9 (100) | 99.8 (98.9) | 96.7 (74.6) |

| Rsym | 0.13 (1.57) | 0.09 (1.34) | 0.09 (0.54) | 0.11 (0.52) | 0.09 (0.35) | 0.10 (0.44) | 0.14 (0.69) |

| Refinement | |||||||

| Resolution (Å) | 48–2.64 | 46–2.15 | 35–2.5 | 56–2.1 | 46–2.9 | 46–2.5 | 46–2.5 |

| No. of reflections | 64,657 | 27,897 | 7,822 | 73,246 | 20,745 | 32,664 | 27,629 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.21/0.26 | 0.21/0.23 | 0.19/0.24 | 0.19/0.20 | 0.18/0.19 | 0.19/0.20 | 0.19/0.23 |

| No. of atoms | 15,894 | 7,897 | 1,912 | 9,062 | 3,977 | 4,091 | 4,025 |

| Protein | 15,588 | 7,769 | 1,877 | 8,430 | 3,872 | 3,934 | 3,934 |

| Ligands | 6 | 105 | 0 | 23 | 44 | 135 | 24 |

| Water | 298 | 50 | 35 | 609 | 61 | 135 | 67 |

| B-factors | |||||||

| Protein | 34.4 | 55.3 | 38.3 | 48.1 | 68.9 | 57.8 | 57.1 |

| Ligands | 43.0 | 62.4 | 68.5 | 91.6 | 83.0 | 67.0 | |

| Water | 25.4 | 41.9 | 31.1 | 41.0 | 65.1 | 55.9 | 49.5 |

| RMSD | |||||||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.004 |

| Bond angle (°) | 0.734 | 0.83 | 0.787 | 1.123 | 0.970 | 0.820 | 0.870 |

| Ramachandran | |||||||

| Favored (%) | 96.0 | 94.6 | 94.6 | 95.0 | 96.0 | 97.0 | 96.7 |

| Outlier (%) | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

Highest-resolution shell values are shown in parentheses. RMSD, root mean square deviation.

Structure determination.

Data were gathered on crystals frozen at 105 K on beamline 08ID-1 at the Canadian Light Source. Diffraction data sets were collected at a wavelength of 0.9795 Å using 1° oscillations with 360 images, and the X-ray diffraction patterns were processed with XDS. The first Hp5 TbpB structural model was obtained by molecular replacement based on ApH49 TbpB (PDB code 3HOL) using PHASER (25). The ApH49, AsH57, and ApH87 TbpB mutants were solved by molecular replacement using wild-type ApH49, AsH57, and ApH87 TbpBs as search models (PDB codes 3HOE, 3PQU, and 3PQS, respectively), followed by a rigid body refinement. Final models were generated following several rounds of model building and refinement using Coot and PHENIX refine (25). The numbering of all TbpBs initiates with the first mature amino acid (cys1) remaining after signal peptide cleavage.

Biolayer interferometry.

The recombinant proteins prepared as described above were used to determine the dissociation constant (Kd) of wild-type and mutant TbpBs. Purified deglycosylated pTf was initially biotinylated using EZ-link NHS-PEG4-biotin with a molar coupling ratio of 1 prior to purification via zebra spin desalting column (Thermo Scientific). A FortéBio Octed Red system was then used to measure the binding of various TbpB analytes to immobilized pTf at 25°C: streptavidin-coated tips were soaked for 15 min in HEPES-buffered saline (HBS; 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 200 mM NaCl, 0.02% Tween 20) to rehydrate the sensor surfaces before activation with the pTf. Sensor surfaces were activated after a 10-min incubation of the streptavidin-coated tips within HBS supplemented with 0.25 mg of biotinylated pTf/ml. The sensors were washed for 10 min in assay buffer (HBS supplemented with 0.1 mg of bovine serum albumin/ml) to remove any unbound pTf prior to dipping the pTf-loaded sensors into a dilution series of TbpB to determine the TbpB-pTf binding association; after each association step, the sensor tips were transferred into the HBS solution to monitor the complex dissociation for 10 min. The binding dissociation constants were analyzed by the equilibrium binding method and fitted with Kaleidagraph using a quadratic equation. The results of these analyses are presented in Table 2, along with results from prior studies.

TABLE 2.

Affinity constants for wild-type and mutant TbpBsa

| Protein | Mutation | Loop | Kd (concn) | Method | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ApH49 TbpB | WT | 55 nM | ITC | 6 | |

| F171A | L8 | NDB | ITC | 6 | |

| WT | 44 nM | SPR | 6 | ||

| ApH87 TbpB | WT | 60 nM | SPR | 9 | |

| Y95A | L3 | 585 nM | SPR | 9 | |

| Y121A | L5 | 203 nM | SPR | 9 | |

| Y174A | L8 | 8.9 μM | SPR | 9 | |

| R179E | L8 | 6.1 μM | SPR | 9 | |

| AsH57 TbpB | WT | 120 nM | SPR | 9 | |

| F63A | L1 | 326 nM | SPR | 9 | |

| F152A | L5 | 495 nM | SPR | 9 | |

| Hp5 TbpB | WT | 13 nM | BLI | This study | |

| Y167A | L8 | 3.64 μM | BLI | This study | |

| W176A | L8 | 0.94 μM | BLI | This study |

Binding assays with wild-type and mutant TbpBs were performed using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) (6), surface plasmon resonance (SPR) (9), or biolayer interferometry (BLI). See Materials and Methods for further details. The loop that the mutation was located on is listed using the nomenclature proposed in a prior publication (9). WT, wild type; NDB, no detectable binding.

Immunization and challenge experiments with H. parasuis in pigs.

A total of 22 colostrum-deprived LargeWhite × Pietrain piglets, coming from a farm with an excellent sanitary status and no previous clinical history of infections by H. parasuis or A. pleuropneumoniae, were housed in isolation rooms designed for biosecurity requirement level II (Isolation Unit, University of León, León, Spain). Nasal and tonsillar swabs were obtained from each piglet and determined to be negative for H. parasuis by PCR. The animals were also found to be serologically negative for porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus and A. pleuropneumoniae by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and for circovirus by PCR. The piglets were hand reared and fed pasteurized bovine colostrum for 7 days, a porridge mixture (bovine colostrum plus Startrite 100 [SCA, Iberica, Spain]) from 7 to 14 days, and piglet dry meal formula (Startrite 100) for the rest of the study.

At 4 weeks of age, the piglets were randomly assigned to two control groups and two test groups. The controls groups consisting of five pigs each were immunized with buffer alone or with the commercial Porcilis Glässer (PG) vaccine, serving as the negative- and positive-control groups, respectively. The test groups consisting of six pigs each were immunized with recombinant wild-type TbpB20-537 from H. parasuis strain Nagasaki or with the Y167A mutant of TbpB20–537. The negative-control group (n = 5) received 2 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4; PBS) administered intramuscularly at 28 and 49 days of age. The test groups received 200 μg of protein antigen in 2 ml of a mixture of PBS and Montanide IMS 2215 VG PR adjuvant (Seppic, Inc., Paris, France) administered via intramuscular injection at 28 and 49 days of age. The PG positive-control group (n = 5) received 2 ml of PG vaccine administered intramuscularly at 28 and 36 days of age, as recommended by the vaccine's manufacturer. At 74 days of age, all groups were challenged by intratracheal injection of a lethal dose (108 CFU) of H. parasuis Nagasaki strain suspended in 2 ml of RPMI 1640. Piglets with severe signs of distress were immediately euthanized for necropsy. Animals that survived challenge were humanely euthanized at 88 days of age with an intracardiac sodium pentobarbital overdose. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the University of León Ethical Committee and the Spanish Government.

Clinical and pathological examinations.

Rectal temperatures and other clinical signs (such as weakness, apathy, coughing, limping, dyspnea, lack of coordination, and/or loss of appetite) were monitored every 12 h during the first 7 days postchallenge and, after that, once a day until the end of the study. All animals were subjected to necropsy, and gross lesions were recorded, with particular attention paid to the pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal cavities, the joints, the lungs, and the central nervous system.

Blood collection and PBMC isolation.

Blood samples were collected by aseptic venipuncture from the jugular vein into commercial tubes containing EDTA as an anticoagulant, using a 21-g needle and a holder (Vacutainer; Becton Dickinson, USA) on the challenge day and once a day up to day 4 postchallenge. The samples were processed immediately for peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) isolation by means of a gradient centrifugation using Histopaque (Sigma-Aldrich). Cell viability was evaluated by the trypan blue exclusion test.

Immunostaining.

For immunostaining, 50 μl of each sample (5 × 105 cells) diluted in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin and 0.01% sodium azide) were used for each antibody labeling. Double staining was performed using the following combinations of monoclonal antibodies (MAbs): (i) 74-12-4 (anti-pig CD4α-fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC] conjugated, IgG2b; BD Pharmingen, USA) and 76-12-11 (anti-pig CD8α-phycoerythrin [PE] conjugated, IgG2a; BD Pharmingen) and (ii) 5C9 (anti-pig αIgM-purified, IgG1) and B-ly4 (anti-pig CD21-PE conjugated, IgG1; BD Pharmingen). The MAb 5C9 was generous gifts from Domínguez Juncal (INIA, Madrid, Spain). PBMCs were incubated in a V-shaped 96-well microplate (Nunc, USA) with primary MAbs for 20 min at 4°C and washed in FACS buffer thrice. Nonspecific epitopes were blocked using 5% pig normal serum for 10 min at 4°C. This step was not carried out for the B cell staining (IgM) because the 5C9 clone has affinity for the αIgM heavy chain. After blocking, the cells were incubated for 20 min at 4°C with anti-isotype antibody (FITC-conjugated rat anti-mouse IgG1, A85-1 clone; BD Pharmingen) or with the secondary labeled antibody. When the isotype of the primary MAb was the same as that used for labeling the secondary antibody, a simple blocking of Fab region with 5% normal mouse serum diluted in FACS was carried out. After a washing step with FACS buffer, the cells were resuspended in 400 μl of FACS buffer and transferred into a round-bottom tube (BD Falcon), and 7-amino actinomycin D (BD Pharmingen) was added to stain the DNA of dead and damaged cells and exclude it from analysis. A total of 20,000 events were acquired in a FACSVerse flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). The region to perform the analysis of lymphocyte populations was determined using a forward-scatter versus side-scatter dot plot.

Statistical analysis.

In order to compare survival curves illustrated in Fig. 2, a formal statistical analysis of the Kaplan-Meier curve was performed, and the results are summarized in Table 3. For the results illustrated in Fig. 3, a log-rank test was performed between groups of animals. To evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of our ability to predict risk of death of piglets with lower than a 24.2% B-cell response, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed using the MedCalc version 13.3.1 (MedCalc Software BVBA). Analysis of the specific cellular immune response was evaluated using one-way analysis of variance. Statistical means were contrasted by using the Tukey test (P < 0.05) with Statistix 8.0 software (Analytical Software, Roseville, MN). Figures 2 and 3 were created with GraphPad Prism (version 6.0 for Mac OS X; GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

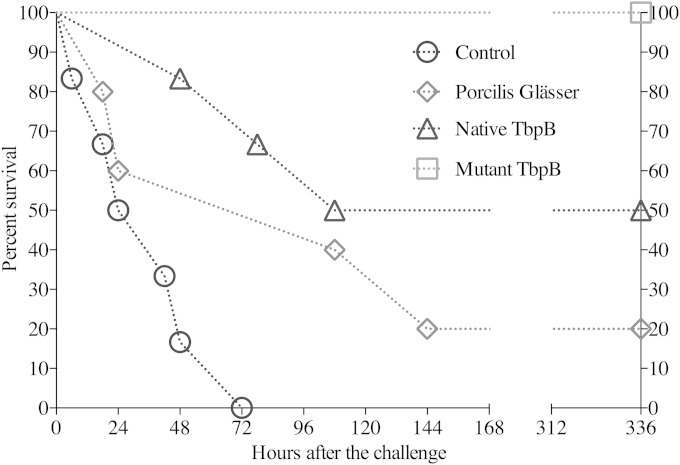

FIG 2.

Comparative abilities of wild-type and mutant TbpB to induce a protective immune response against H. parasuis infection. Groups of pigs were immunized with PBS (control), a commercial vaccine derived from the challenge strain (Porcilis Glässer), wild-type TbpB from H. parasuis strain Hp5 (native TbpB), or the Y167A site-directed mutant derived from the wild-type TbpB (mutant TbpB). The pigs were challenged by intratracheal inoculation with 108 CFU of the Hp5 strain and were monitored for clinical signs and symptoms throughout the duration of the experiment. The experiment was completed after 15 days, and all of the pigs were examined at necropsy for pathological findings.

TABLE 3.

Mean and median survival times of pigs in different treatment groupsa

| Treatment group | Survival time (h) after challenge |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | 95% CI for the mean | Median | 95% CI for the median | |

| PBS control | 35.0 | 9.7 | 15.9–54.0 | 24.0 | 18.0–48.0 |

| Mutant TbpB | 336.0 | 0.0 | 336.0–336.0 | ||

| Native TbpB | 207.0 | 53.1 | 102.8–311.1 | 108.0 | 78.0–108.0 |

| Porcilis Glässer | 126.0 | 51.6 | 24.6–227.3 | 108.0 | 18.0–144.0 |

The survival time of the mutant TbpB group was greater than for the other groups (P < 0.05), and the survival time of the native TbpB group was greater than that of the PBS control group (P < 0.05). CI, confidence interval.

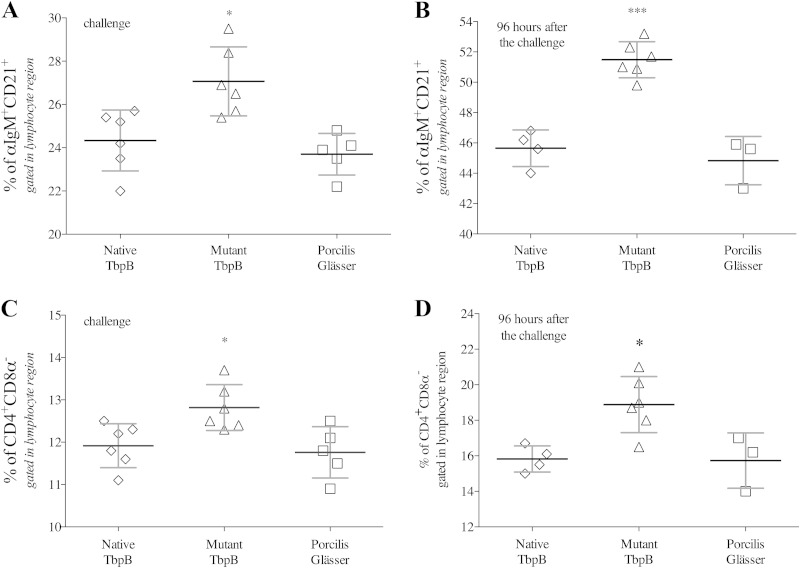

FIG 3.

Specific cellular immune response induced by wild-type and mutant TbpB antigens. (A and B) B-cell responses on the day of challenge (after two intramuscular immunizations) and 4 days (96 h) after challenge, respectively. (C and D) T-helper cell response on the day of challenge and 4 days after challenge. The diamonds, triangles, and squares represent pigs immunized with native TbpB, the Y167A mutant TbpB, and the Porcilis Glässer (PG) vaccine, respectively. There are reduced numbers of samples for the native TbpB- and PG vaccine-treated pigs on day 4 after challenge. The analysis was performed by FACS analysis with PBMCs. Significant differences between groups are indicated by asterisks (*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001).

Ethics statement.

The Veterinary Science Animal Care Committee at the University of Calgary approved protocol AC11-0063 for the immunization of pigs. The University of Saskatchewan's University Committee on Animal Care and Supply approved protocols AS09-191 (pigs), AS09-192 (rabbits), and AS09-193 (mice). These protocols adhered to the Canadian Council of Animal Care guidelines. The Executive Commission of the Ethical Committee of the University of León approved protocol 1-2011. This protocol adhered to the guidelines of the Spanish Government (Law 32/2007, Royal Regulation 664/1997) and the European Community (European Directives 2010/63/UE and 2000/54/CE).

RESULTS

Generating Tf binding mutants of TbpB with minimal structural changes.

Preliminary immunization experiments with TbpBs from human, bovine, and porcine pathogens in different hosts suggested that the TbpB from A. pleuropneumoniae strain H49 had reduced immunogenicity in pigs (data not shown), which we hypothesized to be due to the interaction of host Tf with the administered TbpB influencing the development of anti-TbpB antibodies. This prompted us to more definitively address the question of whether binding of host Tf was impacting the development of an immune response against TbpB by preparing nonbinding mutants and selecting those that had dramatic reduction in Tf binding yet had minimal structural changes. We rationalized that this would be an important consideration when performing the immunization experiments with the site-directed mutant proteins so that they would have a comparable repertoire of epitopes being recognized by antibodies and the cognate B-cell receptors as the native proteins. To provide the opportunity to test the mutant proteins in a readily available infection model (24), we decided to initiate structural studies with TbpBs from Haemophilus parasuis.

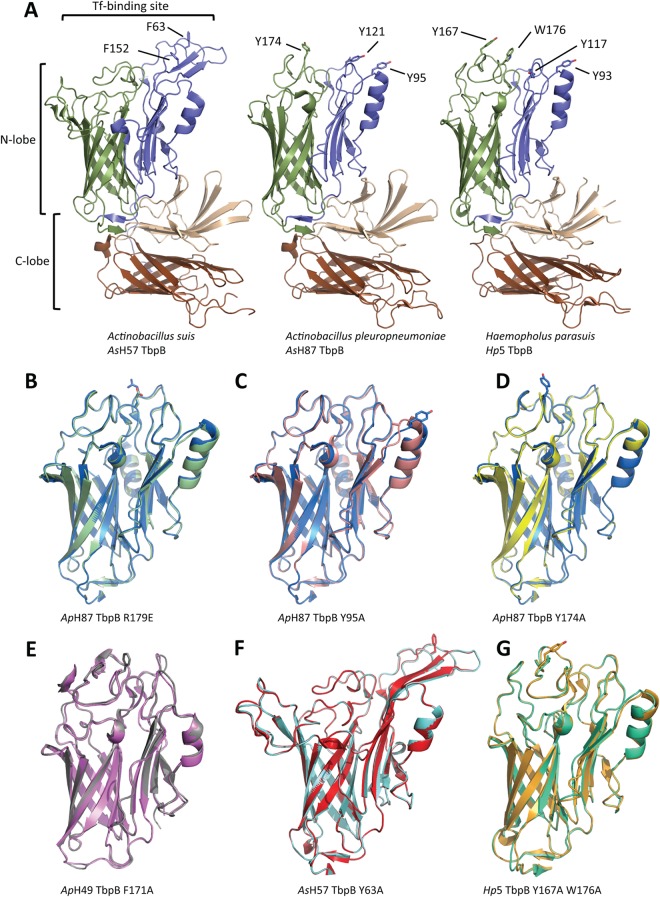

The gene encoding TbpB from H. parasuis Nagasaki strain (serotype 5 [Hp5]) was cloned into our custom expression vector for production and purification of recombinant TbpB. The purified recombinant TbpB was then tested in an extensive set of crystallization screens, and the resulting crystals were used for structural analysis. Unfortunately, we were not able to produce crystals of the Hp5 TbpB that had diffraction properties suitable for structural determination. However, we took advantage of prior studies in which we determined the structures of TbpBs from A. pleuropneumoniae and A. suis and designed Tf binding mutants based on structural models of Tf-TbpB complexes using a customized version of standard Rosetta docking algorithms (6, 9). Thus, a structural model of the Hp5 TbpB was generated with the ApH49 TbpB structure as the template (81% sequence identity), and comparison of the surfaces of the TbpB N-lobe cap region was used to identify potential residues to target for mutagenesis. The modeled structure of native TbpB from Hp5 is illustrated in Fig. 1A and compared to structures of TbpBs from A. pleuropneumoniae and A. suis. Since tyrosine mutants from A. suis H57 and A. pleuropneumoniae H49 and H87 had major impacts on Tf binding (6, 9) a series of tyrosines were targeted for mutagenesis. Tyrosines 93, 117, and 167 and tryptophan 176 were selected through this process (Fig. 1A).

FIG 1.

Comparison of structures of wild-type and mutant TbpBs. (A) Diagram representation of the AsH57 and ApH87 TbpB crystal structures (PDB codes 3PQU and 3PQS), together with a homology model of the Hp5 TbpB. The N-lobe β-barrel and handle domains are, respectively, colored green and blue; the C-lobe β-barrel and handle domains are colored brown and sand. The Tf-binding site is indicated on the AsH57 TbpB. Important residues identified for the Tf-recognition are illustrated in stick representation and labeled on the AsH57 and ApH87 TbpB structures; designed Hp5 mutations are labeled on the Hp5 TbpB model. (B to D) Structure superpositions of the wild-type ApH87 TbpB (blue) with the R179E (green, PDB code 4O3Y), Y95A (pink, PDB code 4O3Z), and Y174A (yellow, PDB code 4O49) mutant TbpB N-lobes, respectively. (E) Structure superposition of the wild-type (gray) and F171A (purple, PDB code 4O3X) ApH49 TbpB N-lobes. (F) Wild-type (red) and Y63A (cyan, PDB code 4O3W) AsH57 TbpB N-lobes. (G) N-lobe superposition of the Hp5 TbpB W176A single mutant (green, PDB code 4O4U) and Y167A/W176A double mutant (gold, PDB code 4O4X). For clarification, all mutated residues are drawn as stick representations and are indicated by lines.

The mutant genes were introduced into our custom expression vector, and the mutant proteins were prepared and tested for their stability and Tf binding capabilities by an affinity capture assay with pTf coupled to Sepharose and a solid-phase binding assay with pTf conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. The results indicated that the Y167A and W176A no longer had detectable pTf binding in these assays, Y117A had relatively weak binding, and Y93A retained the greatest pTf binding activity. Binding assays were performed by biolayer interferometry using the OCTET Red system to determine whether the Y167A mutant had substantially reduced binding affinity. The results from this analysis are presented in Table 2, along with results from prior studies for comparative purposes. The results demonstrate that the Y167A mutant has the greatest reduction in binding affinity compared to the native TbpB (>280-fold) is thus potentially a good candidate for immunization studies. It is interesting that the mutants with the most dramatic drop in binding affinity were all localized to loop 8 (Table 2), which is the first loop in the cap region of the barrel domain of the N-lobe.

Structural studies were performed with wild-type and mutant proteins to determine the degree to which they resulted in conformational changes. The structures of the several of the mutant TbpBs derived from A. pleuropneumoniae H87 TbpB, the A. pleuropneumoniae H49 TbpB, or A. suis H57 TbpB were determined, and the structures were compared to the wild-type proteins (Fig. 1B to F; Table 1, PDB codes 4O3X, 4O3W, 4O3Z, and 4O49). The superimposed structures demonstrate that there were minimal conformational changes associated with the individual site-directed mutants. Comparison of the electron density maps further illustrated that the structures were virtually superimposable except for the difference density representing the respective amino acid side chain.

The lack of a structural model for the wild-type Hp5 TbpB derived directly from protein crystallography precluded making the same comparisons for the Y167A and W176A mutant proteins. However, the W176A single-mutant TbpB and the Y167A W176A double-mutant TbpB provided diffraction quality crystals that enabled us to determine the structure at 2.6 and 2.9 Å resolutions, respectively (Fig. 1G; Table 1, PDB codes 4O4U and 4O4X). Close inspection of the electron density maps demonstrated that the alanine side chain of residue 176 forms a crystal lattice contact in both of the mutant crystals, which may indicate that tryptophan 176 is interfering with crystal formation in the wild-type protein. Further comparative analysis on the W176A single mutant and the Y167A W176A double mutant TbpBs confirms the minimal effect that the Y167A point mutation had on the overall Hp5 TbpB structure (Fig. 1G). Thus, in spite of our inability to directly demonstrate that there were minimal changes in conformation in the Y167A mutant relative to wild-type TbpB, the results with the equivalent point mutation at conserved sites within the Y174A and F171A mutants from A. pleuropneumoniae H87 and H49 TbpBs indicates that substantial changes in binding affinity can be achieved with minimal conformational change (Fig. 1D and E).

A Tf binding mutant of TbpB induces superior protection in an H. parasuis infection model.

In order to compare the immunogenicity of the H. parasuis Hp5 wild-type and Y167A mutant TbpBs, an immunization and challenge experiment was implemented similar to those performed previously (24). Groups of pigs were immunized with PBS (control group, 5 pigs), a commercial vaccine (PorcillisGlässer group, 5 pigs), the wild-type TbpB (native TbpB group, 6 pigs), or the Y167A mutant TbpB (mutant TbpB group, 6 pigs). The pigs were challenged by the intratracheal administration of 108 CFU of the Nagasaki strain (Hp5) of H. parasuis and subsequently monitored for clinical symptoms for the duration of the experiment. Pigs with severe clinical symptoms were euthanized and pathological findings were determined upon necropsy. The survival of immunized pigs is illustrated in Fig. 2, and the statistical analysis is summarized in Table 3.

As expected, all of the pigs treated with PBS (control) did not survive more than 72 h, displaying a mean survival time of 35 h. The characteristic inflammatory changes caused by H. parasuis infection were observed: severe fibrinous polyserositis in pericardial, pleural, and peritoneal cavities, with a great amount of fibrin strands or layers on serosal surfaces, and severe polyarthritis and meningitis. Surprisingly, only one of the 5 pigs immunized with the commercial vaccine (PG) survived the full 15 days, with a mean survival time of 126 h. In the affected pigs there were severe fibrinous polyarthritis located mainly in carpal and hock joints but also moderate to severe polyserositis in peritoneal and pericardial cavities, as well as severe meningitis in some pigs. This vaccine, which is derived from the challenge strain, provided full protection against mortality in previous experiments (24), suggesting that the bacteria used in this challenge experiment were particularly virulent. Three of the pigs immunized with the wild-type TbpB survived the full 15 days of the experiment but showed clinical signs of infection (claudication, dyspnea, or fever) and had severe chronic lesions on autopsy. There were signs of infection (claudication or dyspnea), and severe chronic lesions were observed on autopsy in the surviving pigs (fibrinous polyarthritis, pericarditis, and peritonitis, mainly, along with mild meningitis in some pigs). All of the pigs immunized with the Y167A mutant TbpB survived the full 15 days of the experiment, and two of the pigs did not demonstrate any signs of infection. Upon autopsy, only one surviving pig had serious lesions, and the remaining five pigs had no lesions or only mild lesions. The survival time of the pigs immunized with the mutant TbpB was significantly longer than the other groups (P < 0.05), and the survival time of the pigs immunized with the native TbpB was significantly greater than the control (P < 0.05). Overall, these results provide quite compelling evidence that the mutant TbpB was superior to the native TbpB in inducing a protective immune response, strongly implicating interference in the development of an efficacious immune response through the binding of host transferrin.

A Tf binding mutant of TbpB induces superior B cell and T helper cell responses.

Blood samples were drawn immediately prior to challenge (after two immunizations) and at various times after challenge in order to analyze the adaptive immune response. The samples were evaluated by FACS analysis for mature B cell (αIgM+ CD21+) and T helper cell (CD4+ CD8α−) subsets. The results demonstrated that prior to challenge the Y167A mutant TbpB antigen had induced a stronger B and T helper cell response than had the native TbpB antigen or PG vaccine (Fig. 3A and C). Due to the unexpectedly rapid progression of disease in the control PG vaccine treated group, samples taken 96 h after challenge were the last opportunity to evaluate the cellular response with sufficient numbers of animals for statistical analysis. The results demonstrated that challenge with H. parasuis resulted in an expansion of the B cell response in all three groups, with the response to the mutant TbpB (51.48% ± 1.18%) significantly higher than the response to the native TbpB (45.65% ± 1.20%) or PG vaccine (44.83% ± 1.59%) (Fig. 3B). A similar tendency was observed in the T helper cell response; however, the difference in the percentages between the three groups was less evident (Fig. 3D). Since the low responders were the ones tending to die earlier than 3 days, the observed differences between the groups at the 96-h time point are actually an underestimate. For example, the two lowest B-cell responding pigs in the PG group at challenge (Fig. 3A) were not included in the 96-h time point (Fig. 3B), so the average is actually for the highest three responders of that group. An analysis of the data for Fig. 3A with an ROC curve indicated that there was 90% sensitivity and 91.7% specificity at predicting risk of death with a B cell response of <24.2%.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study clearly demonstrate that the binding of host Tf impairs the ability of systemically administered TbpB to induce a protective immune response against infection by H. parasuis (Fig. 2). Our ability to observe a difference between the immunogenicity of the wild-type and mutant proteins was likely due to a number of factors, including the lack of known toxins contributing to the pathogenesis of infection (26), the virulence of the challenge bacteria, and the fact that mutations in single residues can dramatically impact binding without significant changes in the structure or conformation of the protein (Fig. 1, Table 2). These observations have important implications regarding the previous attempts at developing TbpBs as vaccine antigens (15, 16, 18, 20–22, 27) since they suggest that much more effective vaccines could be developed with TbpB derivatives lacking the ability to bind host Tf. Notably, the results of the present study suggest that TbpB-based vaccines for H. parasuis are not only a viable alternative to existing vaccines but are clearly superior. The results also suggest that further investigation of TbpB-based vaccines against other pathogens is warranted.

Although impairment of development of the immune response by binding of host Tf likely also applies to the TbpA protein, the generation of single site-directed mutants to impair binding of Tf may not be achievable (8). Thus, further modification of TbpA would likely be required, or alternate strategies may need to be considered if vaccines targeting TbpA are considered (28).

Our results clearly demonstrate that there is impairment in the development of a protective immune response by TbpB due to binding of host Tf; however, the mechanism for this impairment is not readily apparent. Simple blocking of epitopes in the “cap” region of the N-lobe where Tf binds is one obvious mechanism that would infer that maximum protection depends upon antibodies targeting this region. It is conceivable that under the conditions of the challenge experiment the antibodies directed to this region of the protein were capable of inhibiting the acquisition of iron from host Tf, which may account for the greater protection conferred by immunization with the mutant TbpB. Directly demonstrating this might be a challenge, since growth dependent upon TbpB for A. pleuropneumoniae has only been demonstrated in an animal infection model and was not observed in growth experiments in the laboratory (14). The fact that we selected a site-directed mutant with the greatest impairment of Tf binding (Table 2) might have been a factor that contributed to the level of protection we observed in the challenge experiment (Fig. 2), and this may be an important consideration when further pursuing this approach for the development of vaccines.

Simple blocking of a subset of epitopes would not necessarily provide an explanation for the lower B-cell and T-cell response induced by the native TbpB compared to the mutant TbpB (Fig. 3). If the number of available epitopes or the effective size of antigen was a major factor, one might anticipate that the PG vaccine would have had the strongest cellular response, which it clearly does not (Fig. 3). However, it is possible that the large flexible loops in the N-lobe Cap region (Fig. 1) are capable of engaging a larger repertoire of B cells due to their ability to assume a variety of different conformations, and this could contribute to the larger B-cell response of the site-directed mutant compared to the native protein, where these multiple epitopes would not be accessible. In order to address this hypothesis, one may have to compare the nonbinding mutant to a derivative with more extensive modifications that result in a reduction in the size and flexibility of the loops, so that binding and loop size would be addressed independently.

Since the bacteria that possess Tf receptors normally reside on the mucosal surface of the upper respiratory or genitourinary tract (1), where the levels of host Tf are substantially lower that within the body compartment (29, 30), the phenomenon observed here may not have any significance in the acquisition of natural immunity to these bacterial species. Similarly, it may be possible to develop mucosal immunization strategies in which the impact of the host Tf on development of the immune response is not as marked. However, our results suggest that there would not be any disadvantage in using an appropriately selected site-directed mutant TbpB, irrespective of the route of immunization.

The present study is the first to report the impact of binding host Tf on the immunogenicity of Tf binding proteins but should be compared to prior studies, demonstrating that reduction in binding of factor H (fH) improves the immunogenicity of the bacterial surface protein factor H binding protein (fHbp) (31). The latter study was performed in transgenic mice, where the human fH gene was under the control of an exogenous constitutive promoter, so the levels at different body sites may not totally reflect the physiological conditions. Nevertheless, the results clearly show an enhanced serum bactericidal antibody response to the nonbinding mutant fHbp and, logically, the results can be extrapolated to immunization studies in humans. Beernink et al. (31) demonstrated that antibody directed against the mutant fHbp was more effective at blocking the binding of fHbp to fH, which provided a logical mechanism by which the mutant fHbp would provide a superior bactericidal response. This may have parallels to our study and supports the hypothesis that the mutant TbpB may be more effective at inducing a protective immune response by blocking binding and inhibiting growth, but, as mentioned above, demonstrating an inhibition of growth may not be feasible in laboratory-based studies.

We also demonstrated here the value of using surrogate host-pathogen systems to study vaccine related issues and drawing comparisons between studies in human and veterinary medicine. Although the use of humanized transgenic mice will be valuable in demonstrating whether this phenomenon applies to human pathogens, since experiments in the native host are not possible, the information presented here will be invaluable for the design and development of vaccines against both human and animal pathogens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was partly supported by an Interdisciplinary Team Grant from Alberta Innovates–Health Solutions, by a grant from Alberta Livestock Management Association (C.C., J.F., D.C., E.C., T.F.M., and A.B.S.), and by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitivity (grant AGL2011-23195 [R.F., S.M.-M., C.B.G.-M., and E.F.R.-F.).

We thank Joenel Alcantara, Erin Brown and Greg Meunch (University of Calgary) for assistance with the pig immunizations, the Canadian Light Source beamline staff at CMCF-08ID-1 for assistance with X-ray data collection, Mirela Noro (University of Passo Fundo) for assistance with statistical analyses, and María José García-Iglesias and Claudia Pérez-Martínez (University of León, Department of Animal Health, Spain) for helping with autopsies and study of macroscopic lesions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gray-Owen SD, Schryvers AB. 1996. Bacterial transferrin and lactoferrin receptors. Trends Microbiol 4:185–191. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(96)10025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgenthau A, Pogoutse A, Adamiak P, Moraes TF, Schryvers AB. 2013. Bacterial receptors for host transferrin and lactoferrin: molecular mechanisms and role in host-microbe interactions. Future Microbiol 8:1575–1585. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schryvers AB, Gonzalez GC. 1989. Comparison of the abilities of different protein sources of iron to enhance Neisseria meningitidis infection in mice. Infect Immun 57:2425–2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schryvers AB, Gonzalez GC. 1990. Receptors for transferrin in pathogenic bacteria are specific for the host's protein. Can J Microbiol 36:145–147. doi: 10.1139/m90-026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray-Owen SD, Schryvers AB. 1993. The interaction of primate transferrins with receptors on bacteria pathogenic to humans. Microb Pathog 14:389–398. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1993.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moraes TF, Yu R-H, Strynadka NC, Schryvers AB. 2009. Insights into the bacterial transferrin receptor: the structure of transferrin binding protein B from Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Mol Cell 35:523–533. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calmettes C, Alcantara J, Schryvers AB, Moraes TF. 2012. The structural basis of transferrin iron sequestration by transferrin binding protein B. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19:358–360. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noinaj N, Easley NC, Oke M, Mizuno N, Gumbart J, Boura E, Steere AN, Zak O, Aisen P, Tajkhorshid E, Evans RW, Gorringe AR, Mason AB, Steven AC, Buchanan SK. 2012. Structural basis for iron piracy by pathogenic Neisseria. Nature 483:53–58. doi: 10.1038/nature10823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calmettes C, Yu R-H, Silva LP, Curran D, Schriemer DC, Schryvers AB, Moraes TF. 2011. Structural variations within the transferrin binding site on transferrin binding protein, TbpB. J Biol Chem 286:12683–12692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.206102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang X, Yu RH, Calmettes C, Moraes TF, Schryvers AB. 2011. The anchor peptide of transferrin binding protein B is required for interaction with transferrin binding protein A. J Biol Chem 286:45165–45173. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.214171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schryvers AB, Morris LJ. 1988. Identification and characterization of the human lactoferrin-binding protein from Neisseria meningitidis. Infect Immun 56:1144–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schryvers AB, Morris LJ. 1988. Identification and characterization of the transferrin receptor from Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol 2:281–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1988.tb00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornelissen CN, Kelley M, Hobbs MM, Anderson JE, Cannon JG, Cohen MS, Sparling PF. 1998. The transferrin receptor expressed by gonococcal strain FA1090 is required for the experimental infection of human male volunteers. Mol Microbiol 27:611–616. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baltes N, Hennig-Pauka I, Gerlach GF. 2002. Both transferrin binding proteins are virulence factors in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 7 infection. FEMS Microbiol Lett 209:283–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danve B, Lissolo L, Mignon M, Dumas P, Colombani S, Schryvers AB, Quentin-Millet MJ. 1993. Transferrin-binding proteins isolated from Neisseria meningitidis elicit protective and bactericidal antibodies in laboratory animals. Vaccine 11:1214–1220. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(93)90045-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lissolo L, Maitre-Wilmotte G, Dumas P, Mignon M, Danve B, Quentin-Millet M-J. 1995. Evaluation of transferrin-binding protein 2 within the transferrin-binding protein complex as a potential antigen for future meningococcal vaccines. Infect Immun 63:884–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rokbi B, Mignon M, Maitre-Wilmotte G, Lissolo L, Danve B, Caugant DA, Quentin-Millet M-J. 1997. Evaluation of recombinant transferrin binding protein B variants from Neisseria meningitidis for their ability of induce cross reactive and bactericidal antibodies against a genetically diverse collection of serogroup B strains. Infect Immun 65:55–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danve B, Lissolo L, Guinet F, Boutry E, Speck D, Cadoz M, Nassif X, Quentin-Millet MJ. 1998. Safety and immunogenicity of a Neisseria meningitidis group B transferrin binding protein vaccine in adults, p 53 In Nassif X, Quentin-Millet MJ, Taha MK (ed), Eleventh International Pathogenic Neisseria Conference. EDK, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du R, Wang Q, Yang Y-P, Schryvers AB, Chong P, England D, Klein MH, Loosmore SM. 1998. Cloning and expression of the Moraxella catarrhalis lactoferrin receptor genes. Infect Immun 66:3656–3664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Potter AA, Schryvers AB, Ogunnariwo JA, Hutchins WA, Lo RY, Watts T. 1999. Protective capacity of Pasteurella haemolytica transferrin-binding proteins TbpA and TbpB in cattle. Microb Pathog 27:197–206. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1999.0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rossi-Campos A, Anderson C, Gerlach G-F, Klashinsky S, Potter AA, Willson PJ. 1992. Immunization of pigs against Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae with two recombinant protein preparations. Vaccine 10:512–518. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(92)90349-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loosmore SM, Yang YP, Coleman DC, Shortreed JM, England DM, Harkness RE, Chong PSC, Klein MH. 1996. Cloning and expression of the Haemophilus influenzae transferrin receptor genes. Mol Microbiol 19:575–586. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.406943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Webb DC, Cripps AW. 1999. Immunization with recombinant transferrin binding protein B enhances clearance of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae from the rat lung. Infect Immun 67:2138–2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frandoloso R, Martínez S, Rodríguez-Ferri EF, García-Iglesias MJ, Pérez-Martínez C, Martinez-Fernandez B, Gutierrez-Martin CB. 2011. Development and characterization of protective Haemophilus parasuis subunit vaccines based on native proteins with affinity to porcine transferrin and comparison with other subunit and commercial vaccines. Clin Vaccine Immunol 18:50–58. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00314-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. 2010. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de la Fuente AJ, Gutiérrez-Martín CB, Rodríguez-Barbosa JI, Martínez-Martínez S, Frandoloso R, Tejerina F, Rodriguez-Ferri EF. 2009. Blood cellular immune response in pigs immunized and challenged with Haemophilus parasuis. Res Vet Sci 86:230–234. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myers LE, Yang Y-P, Du R-P, Wang Q, Harkness RE, Schryvers AB, Klein MH, Loosmore SM. 1998. The transferrin binding protein B of Moraxella catarrhalis elicits bactericidal antibodies and is a potential vaccine antigen. Infect Immun 66:4183–4192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gorringe AR, Borrow R, Fox AJ, Robinson A. 1995. Human antibody response to meningococcal transferrin binding proteins: evidence for vaccine potential. Vaccine 13:1207–1212. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(95)00055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson JE, Hobbs MM, Biswas GD, Sparling PF. 2003. Opposing selective forces for expression of the gonococcal lactoferrin receptor. Mol Microbiol 48:1325–1337. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang AS, Enns CA. 2009. Iron homeostasis: recently identified proteins provide insight into novel control mechanisms. J Biol Chem 284:711–715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800017200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beernink PT, Shaughnessy J, Braga EM, Liu Q, Rice PA, Ram S, Granoff DM. 2011. A meningococcal factor H binding protein mutant that eliminates factor H binding enhances protective antibody responses to vaccination. J Immunol 186:3606–3614. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]