Abstract

Background:

Glaucoma and diabetes have a common pathogenesis. We estimated the magnitude and determinants of glaucoma in adults with type II diabetes who presented to a tertiary level eye center in 2010.

Study Type:

A cross-sectional survey.

Methods:

Diabetes was diagnosed by history and measurement of blood sugar levels. Glaucoma was diagnosed by assessing optic disc morphology, visual fields, and intraocular pressure. Data were collected on patient demographics, clinical characteristics of diabetes and ocular status through interviews and measurements. The prevalence of glaucoma in diabetics was estimated, and variables were analyzed for an association to glaucoma. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Statistical significance was indicated by P < 0.05.

Results:

The study cohort was comprised of 841 diabetics. The mean age of the cohort was 53.8 ± 10.7 years. There were 320 (38%) females. The prevalence of glaucoma was 15.6% (95% CI: 13.1-18.1). More than 75% of the diabetics had no evidence of diabetic retinopathy (DR). Half of the diabetics with glaucoma had primary open angle glaucoma. The presence of glaucoma was significantly associated to the duration of diabetes (Chi-square = 10.1, degree of freedom = 3, P = 0.001). The presence of DR was not significantly associated to the presence of glaucoma (odds ratio [OR] = 1.4 [95% CI: 0.88-1.2]). The duration of diabetes (adjusted OR = 1.03) was an independent predictor of glaucoma in at least one eye.

Conclusions:

More than one-sixth of diabetics in this study had glaucoma. Opportunistic screening for glaucoma during DR screening results in an acceptable yield of glaucoma cases.

Keywords: Diabetes, diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, visual impairment

Introduction

The World Health Organization has classified glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy (DR) as priority eye diseases.[1] Based on the accelerated “VISION - 2020 initiatives” to address cataract, which is considered the leading cause of age-related visual impairment, the contribution of glaucoma and DR to global blindness is significant and continues to increase. Due to the asymptomatic nature of ocular changes in early diabetes, annual screening for DR is recommended for type II diabetics.[2] However, there is no public health strategy for the early detection of glaucoma through screenings. Evaluation for glaucoma could comprise part of comprehensive eye assessments especially at the secondary and tertiary levels of eye care. For example, screening for glaucoma could be combined with the annual DR screening by performing digital photography of the optic nerve head (ONH) for evaluation by specialists. However, such a screening initiative would depend on the magnitude of glaucoma in diabetics.[3]

The prevalence of glaucoma in diabetics ranges from 4.96% to 14.6%.[4,5] However, geographic distribution and race can affect the association between glaucoma and diabetes.[6,7] To the best of our knowledge, there are no peer review papers documenting the magnitude of glaucoma among diabetics in the state of Maharashtra, India. This study estimates the magnitude and determinants of glaucoma among individuals with type II diabetes who presented to a secondary/tertiary eye hospital in Maharashtra, India.

Methods

This study was conducted between January 2010 and December 2013. The Institutional Research and Ethical Committee approved this study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study. A patient with diabetes was included in this study if he/she presented to our institute for an ophthalmic evaluation irrespective of ocular signs and symptoms. Type II diabetics who agreed to participate were enrolled and examined. Patients with secondary glaucoma due to uveitis, retinal vein occlusion, and trauma were excluded.

To calculate the sample size of this cross-sectional study, we assumed that the prevalence of glaucoma among diabetics was 14.6%.[5] To achieve 95% confidence intervals (CIs), 3% error margin and clustering effect of 1.5, we required 794 randomly selected type II diabetics. To compensate for the loss of data, an additional 5% was added to the sample size. Thus, the final sample size was 840 type II adult diabetics. A glaucoma specialist, an ophthalmologist, experienced in glaucoma assessment and two allied eye care professionals were the field investigators.

Diabetes was defined as a fasting blood sugar >7 mmol/L (>125 mg/dl) or an individual currently medicated for glycemic control.[8] An individual was defined with hypertension, if he/she had a history of high blood pressure and/or was using antihypertensive medications or had a systolic blood pressure >130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure >85 mmHg on three measurements.[9]

Monocular best-corrected visual acuity was measured with an Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study chart held 6 m from the patient. Dynamic retinoscopy was performed to assess refractive error. Slitlamp biomicroscopy included evaluation of the anterior chamber depth, pupil, iris (for new vessels and iridectomy) and lens status. Stereoscopic examination of the ONH was performed with + 90 D and + 78 D Volk lenses (Volk optical Inc. Ohio, USA). Intraocular pressure (IOP) was measured with a Goldmann applanation tonometer after instilling one drop of topical anesthetic on the cornea. Visual field was assessed with a Humphrey Field Analyzer 30-2 Swedish Interactive Thresholding Algorithm program (Carl Zeiss Meditec Inc., Dublin, CA, USA). The anterior chamber angle was examined with a four-mirror goniolens. If the angle were narrow, the rest of the eye examination was performed through undilated pupils.

Glaucoma was defined as the presence of two or more of following findings: (1) Cup-to-disc ratio >0.5; (2) any focal notch in the neuro-retinal rim; (3) thinning and pallor of the neuro-retinal rim; (4) hemorrhage on the optic disc; (5) peripapillary atrophy; (6) visual field defects correlating with optic disc changes; (7) mean deviation >6 db and pattern standard deviation >3 db on perimetry and; (8) IOP >21 mm Hg.

Well-controlled diabetes was considered a fasting and postprandial blood glucose level of ≤125 mg/dl (>7mmol/L) and ≥200 mg/dl (≥11.1 mmol/L) respectively on the day of the eye examination. The normal lipid profile was defined as serum cholesterol ≤200 mg/dl, serum low-density lipoprotein ≤100 mg/dl, serum high-density lipoprotein ≥40 mg/dl and serum triglyceride ≤160 mg/dl.

The data were collected using a pretested form and transferred to an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft® Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Univariate analysis was performed with a parametric method using Statistical Package for Social Studies SPSS-16 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Data on continuous variables (age, duration of diabetes, lipid parameters etc.,) are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables are expressed in frequencies and percentages. Comparison of continuous variables was performed between patients with and without glaucoma by using the difference of mean and the corresponding 95% CI. Categorical variables were analyzed by using 2 by 2 tables and calculating odds ratio (OR) with the 95% CI. The trend between duration of diabetes and incidence of glaucoma was assessed with the Chi-square. A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

The study cohort was comprised of 841 adult diabetics (521 males and 320 females). The mean age of study cohort was 58.3 ± 10.7 years. There were 699 diabetics (83%) who followed the Hindu religion. Two hundred and twenty-seven (27%) diabetics were illiterate and 357 (42.4%) were pure vegetarians.

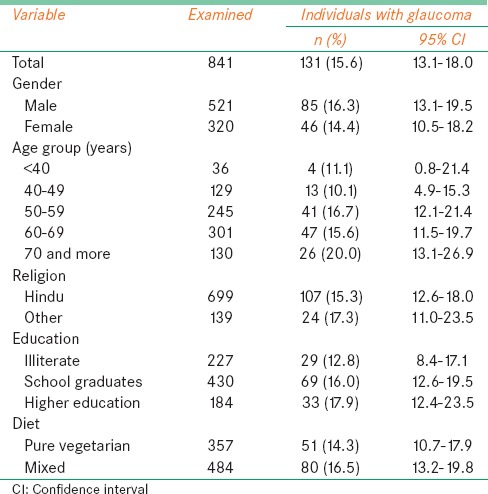

The magnitude and distribution of glaucoma are presented in Table 1. The prevalence of glaucoma among diabetics was 15.6% (95% CI: 13.1-18.0). There was no difference in prevalence between males and females (P > 0.05). The prevalence of glaucoma among diabetics increased with increasing age.

Table 1.

Prevalence of glaucoma among adult diabetics

There were 66 (50.4%) diabetics with primary open angle glaucoma (POAG), 41 (31.3%) with primary angle-closure glaucoma, 14 (9.1%) with neovascular glaucoma and 10 (7.2%) with other types of glaucoma.

Of the 131 diabetics with glaucoma, there were 13 (10%) with nonproliferative DR (NPDR), 17 (13%) with sight threatening DR (STDR) and 101 (77%) without DR in either eye. There were 709 diabetics without glaucoma and DR was absent in 505 (71%) of these patients. NPDR was present in 111 (15.6%) diabetics without glaucoma, and STDR was present in 90 (12.7%) diabetics without glaucoma. The presence of DR was not significantly associated to the presence of glaucoma (OR = 1.4 [95% CI: 0.88-1.2]).

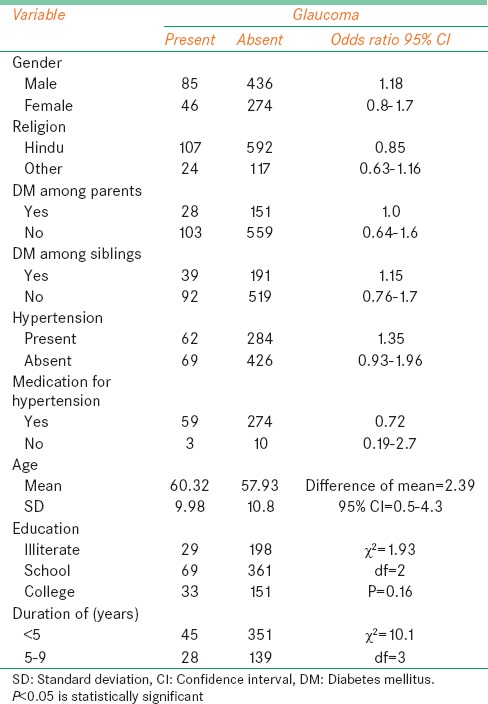

The association of the presence of glaucoma to different risk factors is presented in Table 2. Age (P = 0.01, difference of mean 2.39 years) and duration of diabetes (P = 0.001) were significant risk factors for glaucoma. Binominal regression analysis indicated that the duration of diabetes was a significant predictor of glaucoma among diabetics (P = 0.02). Factors such as age, gender and hypertension were not significant predictors of glaucoma.

Table 2.

Risk factors for glaucoma among diabetics

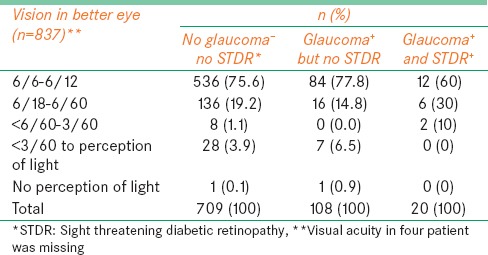

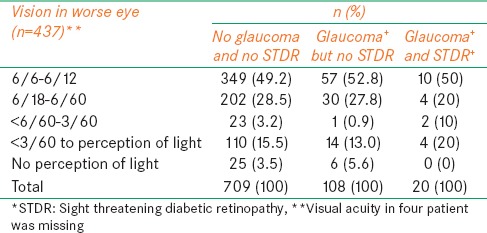

Vision in eyes with less pathology (better eyes) was compared with vision in eyes with greater pathology (worse eyes) grouped by patients according to: (1) Glaucoma and STDR; (2) glaucoma, but no STDR and; (3) no glaucoma and no STDR [Tables 3 and 4]. Status of severe visual impairment (SVI) in the better eyes was not associated to type of ocular morbidity (STDR and glaucoma) (Chi-square = 0.13, degree of freedom = 2, P = 0.73). Status of SVI in the worse eyes was not associated to the type of ocular morbidity (STDR and glaucoma) (Chi-square = 0, degree of freedom = 2, P = 0.97). The visual acuity in four patients was missing.

Table 3.

Vision in better eye in patients with or without glaucoma and sight threatening diabetic retinopathy

Table 4.

Vision in the worse eye of patients with or without glaucoma and sight threatening diabetic retinopathy

Discussion

In this study, we found 1 in 6 diabetics had glaucoma. In addition, we found a statistically significant association between the duration of diabetes and glaucoma (P = 0.02). Hence, the longer the duration of diabetes the greater the association to glaucoma. The prevalence of glaucoma did not differ among those with and without STDR. The risk of SVI in all three groups; those with glaucoma, without glaucoma and with glaucoma and STDR did not differ.

The prevalence of glaucoma among diabetics in our study was 15.6%, which falls within the range reported from other studies worldwide. In an Australian study, the prevalence of glaucoma among diabetics was 7.7%.[10] In Western India, the prevalence of glaucoma among diabetics is 15%.[7] Ellis et al.[11] found that 20% of diabetics had glaucoma. The prevalence of glaucoma among diabetics in Oman was reported at 8.9%.[12] In Botswana (Africa), 2.5% of patients with diabetes had glaucoma.[13] A study of Chinese patients with diabetes reported that diabetes mellitus was associated to increased IOP but not glaucoma.[14] A study in the United Kingdom reported a 2.5 times higher risk of glaucoma among diabetics.[15] Large studies such as the Rotterdam Eye Study and Malay Eye Study also suggested that diabetes was not a risk factor for open angle glaucoma.[16,17] The wide variation in prevalence in the literature may be due to differences in race, geographic locations and the method of measurements among studies.

We found no gender-related differences in the prevalence of glaucoma among diabetics. Among African females, a strong association of diabetes and glaucoma was observed.[18] Pasquale et al. also noted a higher risk of glaucoma among diabetic American females.[19] In Oman, the prevalence of glaucoma was significantly higher among male diabetics compared to female diabetics.[13] Further studies are warranted to review the association of gender and glaucoma among diabetics.

The prevalence of POAG in our study was 7.8%. Most studies in the literature have focused on POAG and diabetes and concluded that diabetes is a risk factor for POAG.[6,16,20] The current study only included individuals with diabetes, and the sample was not calculated to represent POAG (sub-types of glaucoma). Hence, we did not test the association of POAG to diabetes.

The duration of diabetes was a significant predictor of glaucoma in our study. Duration naturally increases with the age of the patient. As age was not significantly associated to glaucoma in our study, it is less likely to influence the positive association of duration of diabetes to glaucoma. Further longitudinal studies are needed to confirm this finding.

In the absence of blindness (vision <3/60) in the better eye in the glaucoma and STDR group, we associated SVI to glaucoma and STDR and noted that there was no statistically significant association. Individuals without glaucoma and STDR (with SVI due to cataract) might be presenting to our institutions. Hence, an association of SVI and comorbidity should be interpreted with caution. A previous study noted that only 14.7% of patients with glaucoma had SVI during follow-up 1-year prior to death.[21] Of note, cases of DR with diabetic macular edema would show some decline in visual acuity.[22] Therefore, the lower proportion of SVI in diabetics in the current study is expected.

There are some limitations to our study. Ideally, a longitudinal study is required to study the risk factors for glaucoma. Our cross-sectional study reports trends only. The subsample size of the type of religion and diet was small. Therefore, their influence on the association of diabetes and glaucoma should be interpreted with caution.

Early detection of chronic and blinding eye conditions such as glaucoma and DR are recommended for timely intervention and treatment. However, universal screening as a public health measure is recommended only if the prevalence of the individual eye disease is high.[23] Nearly 30% of individuals with open angle glaucoma have diabetes.[24] Therefore, DR screening among diabetics is recommended. Global public health policy for preventing visual disabilities due to glaucoma has been proposed by experts to the World Health Organization.[25] We believe that combined screening for DR and glaucoma should depend on the magnitude of both of these potentially blinding conditions, and it should be implemented at that country/sub-regional level despite global policies.[26] We found that 15% of diabetics and 15.9% of STDR cases had glaucoma. These results support the screening of all diabetics for glaucoma as well as screening all STDR cases perhaps at the time of intervention to rule out glaucoma. Although population based glaucoma screening is not recommended, periodic comprehensive eye assessment of all patients older than 40 years (including diabetics) could be an alternative strategy for early detection of STDR and glaucoma.[27]

Acknowledgments

I thank Col. Dr, V. P. Andurkar for allowing using hospital facilities for the study. Mr. Jaysing Jagdale, Mr. Chetan Shishupal and Mr. Vishnu Gaikwad assisted in data collection and co-ordinating the patient's follow-up. Mr. Suresh Morey assisted in data analysis. I appreciated their contribution. I also thank all patients for actively participating in this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization and International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness. Global Action Plan. 2014-2019. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 12]. Available from: http://www.iapb.org/advocacy/who-action-plan .

- 2.Maberley D, Walker H, Koushik A, Cruess A. Screening for diabetic retinopathy in James Bay, Ontario: A cost-effectiveness analysis. CMAJ. 2003;168:160–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloomgarden ZT. Screening for and managing diabetic retinopathy: Current approaches. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64:S8–14. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng Y, Wong TY, Cheung CY, Lamoureux E, Mitchell P, He M, et al. Influence of diabetes and diabetic retinopathy on the performance of Heidelberg retina tomography II for diagnosis of glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:5519–24. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-5060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vyas U, Khandekar R, Trivedi N, Desai T, Danayak P. Magnitude and determinants of ocular morbidities among persons with diabetes in a project in Ahmedabad, India. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2009;11:601–7. doi: 10.1089/dia.2009.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chopra V, Varma R, Francis BA, Wu J, Torres M, Azen SP, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and the risk of open-angle glaucoma the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:227–2321. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orcutt J, Avakian A, Koepsell TD, Maynard C. Eye disease in veterans with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(Suppl 2):B50–3. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.suppl_2.b50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conversion of glucose values from mg/dl to mmol/l. [Last accessed on 2014 Jul 10]. Available from: http://www.soc-bdr.org/rds/authors/unit_tables_conversions_and_genetic_dictionaries/conversion_glucose_mg_dl_to_mmol_l/index_en.html .

- 9.NH Publication; 2004. [Last accessed on 2014 Jul 10]. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Basis for Reclassification of Blood Pressure in ‘The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection and Treatment of High Blood Pressure’; p. 11. Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/hypertension/jnc7full.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen N, Jackson C, Spurling G, Cranstoun P. Nondiabetic retinal pathology-prevalence in diabetic retinopathy screening. Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40:529–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis JD, Evans JM, Ruta DA, Baines PS, Leese G, MacDonald TM, et al. Glaucoma incidence in an unselected cohort of diabetic patients: Is diabetes mellitus a risk factor for glaucoma? DARTS/MEMO collaboration. Diabetes Audit and Research in Tayside Study. Medicines Monitoring Unit. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:1218–24. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.11.1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mengesha AY. Spectrum of eye disorders among diabetes mellitus patients in Gaborone, Botswana. Trop Doct. 2006;36:109–11. doi: 10.1258/004947506776593576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khandekar R, Zutshi R. Glaucoma among Omani diabetic patients: A cross-sectional descriptive study: (Oman diabetic eye study 2002) Eur J Ophthalmol. 2004;14:19–25. doi: 10.1177/112067210401400104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu L, Xie XW, Wang YX, Jonas JB. Ocular and systemic factors associated with diabetes mellitus in the adult population in rural and urban China. The Beijing Eye Study. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:676–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6703104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldacre MJ, Wotton CJ, Keenan TD. Risk of selected eye diseases in people admitted to hospital for hypertension or diabetes mellitus: Record linkage studies-authors’ response. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:1534. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Voogd S, Ikram MK, Wolfs RC, Jansonius NM, Witteman JC, Hofman A, et al. Is diabetes mellitus a risk factor for open-angle glaucoma? The Rotterdam Study. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1827–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan GS, Wong TY, Fong CW, Aung T. Singapore Malay Eye Study. Diabetes, metabolic abnormalities, and glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1354–61. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wise LA, Rosenberg L, Radin RG, Mattox C, Yang EB, Palmer JR, et al. A prospective study of diabetes, lifestyle factors, and glaucoma among African-American women. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21:430–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasquale LR, Kang JH, Manson JE, Willett WC, Rosner BA, Hankinson SE. Prospective study of type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of primary open-angle glaucoma in women. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1081–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newman-Casey PA, Talwar N, Nan B, Musch DC, Stein JD. The relationship between components of metabolic syndrome and open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:1318–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ernest PJ, Busch MJ, Webers CA, Beckers HJ, Hendrikse F, Prins MH, et al. Prevalence of end-of-life visual impairment in patients followed for glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013;91:738–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2012.02555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller AB, Goel V. Oxford Textbook of Public Health. Epidemiology. In: Detels R, McEwen J, Bealehole R, Tanaka H, editors. 4th ed. UK: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 1822–35. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin HC, Chien CW, Hu CC, Ho JD. Comparison of comorbid conditions between open-angle glaucoma patients and a control cohort: A case-control study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:2088–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glaucoma screening Platform Study group, Burr JM, Campbell MK, Campbell SE, Francis JJ, Greene A, et al. Developing the clinical components of a complex intervention for a glaucoma screening trial: A mixed methods study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beynat J, Charles A, Soulié M, Métral P, Creuzot-Garcher C, Bron AM. Combined glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy screening in Burgundy. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2008;31:591–6. doi: 10.1016/s0181-5512(08)75460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hernández R, Rabindranath K, Fraser C, Vale L, Blanco AA, Burr JM, et al. Screening for open angle glaucoma: Systematic review of cost-effectiveness studies. J Glaucoma. 2008;17:159–68. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31814b9693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beynat J, Charles A, Soulié M, Métral P, Creuzot-Garcher C, Bron AM. Combined glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy screening in Burgundy. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2008;31:591–6. doi: 10.1016/s0181-5512(08)75460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]