Abstract

Purpose:

Early presentation of rejection facilitates early initiation of treatment which can favor a reversible rejection and better outcome. We analyzed the incidence, clinical features including rejection-treatment period and outcomes following graft rejection in our series of pediatric corneal graft.

Materials and Methods:

Case records of pediatric penetrating keratoplasty (PK) were reviewed retrospectively, and parameters noted demographic profile, indication of surgery, surgery-rejection period, rejection-treatment interval, graft outcome, and complications.

Results:

PK was performed in 66 eyes of 66 children <12 years, with an average follow-up of 21.12 ± 11.36 months (range 4-48 month). The median age at the time of surgery was 4.0 years (range 2 months to 12 years). Most of the children belonged to rural background. Scarring after keratitis (22, 33.4%) was the most common indication. Graft rejection occurred in eight eyes (12.12%) (acquired nontraumatic - 3, congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy [CHED] - 2, nonCHED - 1, congenital glaucoma - 1, regraft - 1). The mean surgery-rejection period was 10.5 ± 7.3 months and mean rejection-treatment interval was 10.9 ± 7.02 days.

Conclusion:

This study showed irreversible graft rejection was the leading cause of graft failure of pediatric PK. Though, the incidence (12.1%) of graft rejection in current study was not high, but the percentage of reversal (25%) was one of the lowest in literature because of delayed presentation and longer interval between corneal graft rejection and treatment. In addition, categorization of the type of graft rejection was very difficult and cumbersome in pediatric patients.

Keywords: Cornea, graft, pediatric penetrating keratoplasty, rejection, transplantation

Introduction

Technical advancements have made corneal grafting possible at pediatric age group, however, allograft rejection still remain an important cause for graft morbidity in the younger age group and influence significantly the clarity and survival time of corneal grafts.[1,2,3,4,5] Pediatric corneal transplantation has an increased rejection rate because of the more active immune system in younger patients. Well-established graft rejection in children is, usually, irreversible.[6] This problem are intensified in developing countries because majority patients belong poor socioeconomic background and thus lack proper medical compliance.

The aim of this study was to determine the incidence, clinical characteristics including rejection-treatment period and the outcome of grafts following rejection in pediatric penetrating keratoplasty (PK).

Materials and Methods

Case records of children <12 years, underwent optical PK, during the period from January 2007 to June 2011 were retrospectively reviewed. The parameters evaluated included demographic profile, indication of surgery, surgery-rejection period, rejection-treatment interval, graft outcome, complications, and duration of follow-up. Preoperative assessment performed in all patients for evaluation of the corneal pathology and the intraocular pressure measurement. PK performed under general anesthesia by using standard techniques.[1] Synechiolysis, anterior vitrectomy, and cataract extraction with or without intraocular lens (IOL) implantation was done wherever required. Topical steroid (two hourly/day) and antibiotic eyedrops (4 times/day) were instilled in the immediate postoperative period along with cycloplegics if required. Topical steroids drops were gradually tapered and changed to less potent steroids in 6 months time following keratoplasty. All patients were followed-up and evaluated for visual acuity, graft clarity, the graft–host junction, intraocular pressure, and signs of infection/rejection at each postoperative visit. Examination under anesthesia (EUA) was performed in uncooperative patients. Sutures loosening before 4-6 weeks postoperative period were replaced. Selective suture removal was done for suture-related problems.

The diagnosis of corneal graft rejection was made on the basis of inflammation of the anterior chamber with cells and flare, apparent ciliary congestion, keratic precipitates, endothelial rejection line along with differential corneal edema or opaque graft in a previously uninflamed eye, after a period of at least 2 weeks after surgery. Irreversible rejection was defined as a rejection episode leading to graft failure. According to our institutional practice protocol, all patients with a diagnosis or suspicion of graft rejection were admitted for evaluation and management.

All cases of rejection were treated with topical prednisolone acetate 1.0% drops, one hourly around the clock for 1 week with a gradual taper thereafter. In addition, after a complete systemic workup, systemic steroid therapy in form of intravenous pulse steroid (intravenous dexamethasone 4-5 mg/kg body weight, diluted in 150 mL of 5% dextrose over 30-60 min with monitoring of vital signs before, during, and after the infusions) was given. Oral systemic steroids (1 mg/kg body weight) were prescribed after the initial pulse therapy in tapering doses. After 1 week, patients were treated with topical prednisolone acetate 1.0% every 2 h around the clock for 2-4 more weeks, after which therapy was slowly tapered over 3 months. Maintenance and tapering of systemic steroids will depend on the time of postoperative presentation of the rejection episode, severity of the graft rejection, and the response to the therapy.[1,7] Rejection was considered reversible when all signs of rejection resolved along with the improvement in graft clarity and visual acuity.

Results

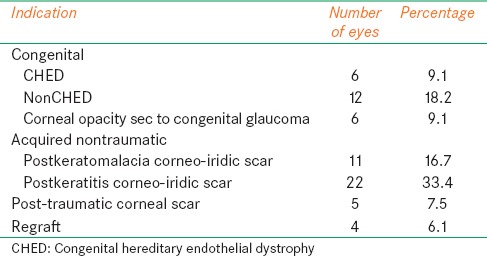

Sixty-six eyes of 66 children underwent optical PK; 43 were male, and 23 were female, the median age of patients at the time of surgery was 4.0 years (range 2 months to 12.0 years). Most of the children belonged to rural background. The mean time of follow-up was 21.12 ± 11.36 months (range 4-48 months). The indications for optical PK included: Congenital, acquired nontraumatic, acquired traumatic, and regraft. The acquired nontraumatic group included 33 (50%) of patients while the congenital group, acquired traumatic group and regraft group included 24 (36.4%), 5 (7.5%), and 4 (6.1%) of patients respectively [Table 1]. Scarring after keratitis 22 (33.4%) was the most common indication in the acquired nontraumatic group. Non-congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (CHED) 12 (18.2%) was the most common in the congenital group; consist of peter's anomaly 6 (9.1%). The mean host cut was 7.33 ± 1.22 mm and mean donor size was 7.80 ± 1.33 mm. A host–graft disparity of 0.25 mm to 1.0 mm was used.

Table 1.

Indications for pediatric keratoplasty

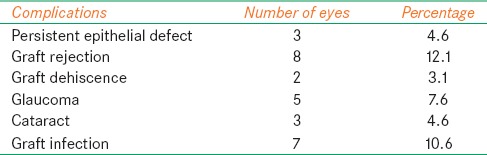

Graft rejection 8 (12.1%) was the most common complication followed by graft infection 7 (10.6%) [Table 2]. Graft failure occurred in 16 (24.2%) in which irreversible graft rejection was responsible for failure in 6 (37.5%) followed by graft infection 5 (31.25%), worsening of glaucoma/postPK glaucoma for 3 (18.8%) cases, and 2 grafts (12.5%) failed after traumatic graft dehiscence.

Table 2.

Occurrence of complications in follow-up period

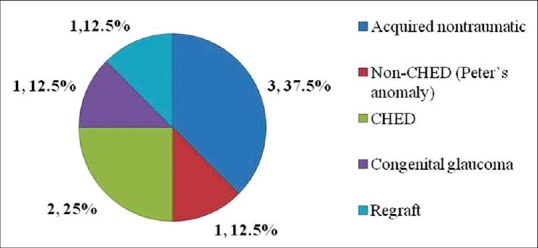

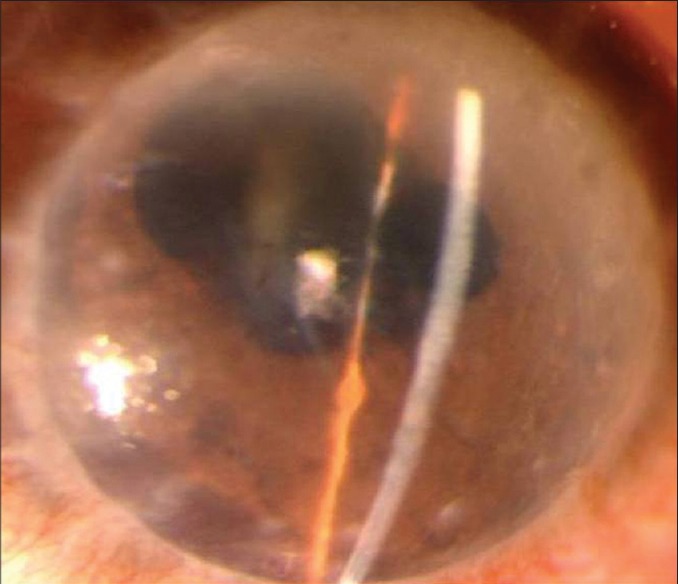

In the 66 eyes that underwent PK, 8 (12.1%) transplants had a rejection episode. Out of them, three grafts were performed for acquired nontraumatic indication, two grafts for CHED and one each for nonCHED, congenital glaucoma, and regraft indications respectively [Figure 1]. The mean period of occurrence of the rejection episode or presentation to the center after PK was 10.5 ± 7.3 months (range 3-24 months) and mean duration of symptoms before treatment was 10.9 ± 7.02 days. The type of graft rejection was made in only three eyes as endothelial rejection [Figure 2] and three eyes could not be labeled the type of rejection except they had ciliary congestion with established corneal edema [Figures 3 and 4] and rest two eyes had rejection occurred without any symptoms and diagnosed on routine follow-up. Intraoperative variables such as lensectomy, vitrectomy, and secondary intraocular procedures were necessary in two out of eight eyes of rejection. During the treatment period, 2 (25%) transplants (1 from acquired nontraumatic and 1 from CHED) showed sign of improvement and had reversible rejection, obtained best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) 20/30 and 20/200 respectively while 6 (75%) transplants did not respond to the treatment and labeled as graft failure after 3 months [Table 3 and Figure 5].

Figure 1.

Distribution of graft rejection (based on indications)

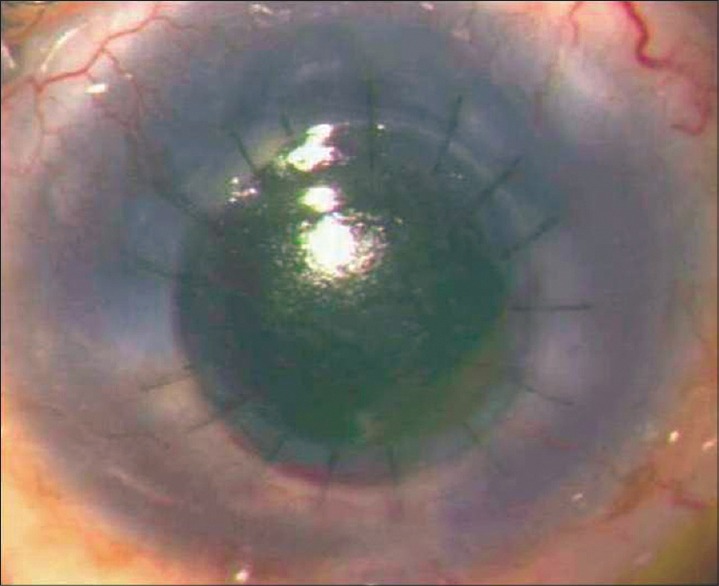

Figure 2.

Early graft rejection, presented with corneal edema, few keratic precipitates and ciliary congestion

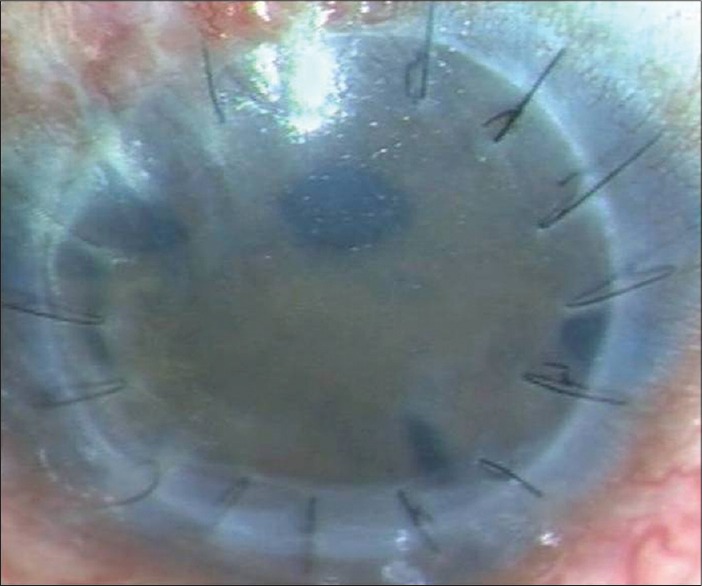

Figure 3.

Episode of graft rejection with delayed presentation in a case of congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy

Figure 4.

Episode of graft rejection with delayed presentation in a case of congenital glaucoma

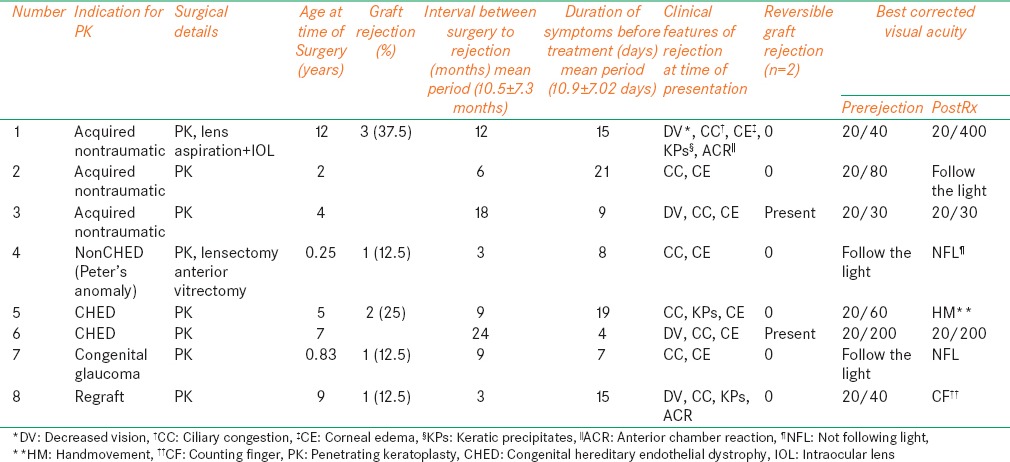

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of eyes with corneal graft rejection

Figure 5.

Failing graft following an episode of irreversible graft rejection in a case of Peter's anomaly

Discussion

Immunological rejection is very common complication after keratoplasty. It can influence significantly the clarity and survival time of corneal grafts. There are various risk factors for graft rejection or graft failure have been studied; recipient age, preoperative diagnosis, recipient rejection status, history of keratoplasty in the contralateral eye, and the preoperative glaucoma.[1] The reported percentages of graft rejection in pediatric keratoplasty vary between 22%[8] and 43.4%[5,9,10] in various studies. Our series of 66 pediatric PK showed an incidence of 12.1% graft rejection.

Although, it may be difficult to determine the contribution of each layer of cornea to a rejection episode[11,12,13] especially in children because of difficulty in examination and unknown onset of process, we could categorize only three cases (37.5%) as endothelial rejection based on clinical examination and three eyes could not be labeled the type of rejection except they had ciliary congestion along with established corneal edema because of late presentation and rest two eyes had rejection occurred without any symptoms and diagnosed during routine follow-up. These children having graft rejection were presented by their parents with complaints of a decrease in visual acuity, hazy cornea, redness, and inability to open eyes in light or for routine follow-up. In the series of pediatric keratoplasty in CHED reported by Javadi et al.,[10] rejection had occurred in 10 eyes (43.4%), of which 7 (70%) were endothelial and 3 (30%) were epithelial.

Corneal graft rejection in children has much lower reversible rate than adults.[11] Thus, these patients should be followed closely to be certain that the signs of rejection are improving. Irreversible graft rejection is one of the major causes of graft failure,[14] the reported percentage of graft rejection resulting graft failure in pediatric keratoplasty vary between 11%[2] and 50%[3] in literature. In this series, irreversible graft rejection was found to be leading the cause of graft failures (37.5%), followed by graft infection (31.25%). The BCVA and graft clarity of children with reversible rejection improved during follow-up. Alldredge and Krachmer[11] showed a much lower reversal rate (28%) in pediatric grafts compared to that of 50−78% in adult grafts. In the current study, we found two grafts (25%) with reversible graft rejection and rest six grafts (75%) rejections were not being reversible perhaps most of these children had reported late for management. Additional surgeries such as lensectomy, anterior vitrectomy, and IOL implantation might be considered as a risk factor for irreversibility.[3,15]

In this series, reversibility seemed to be affected by interval between surgery to rejection and duration of symptoms before initiation of treatment. The mean surgery-rejection period and rejection-treatment period were 10.5 ± 7.3 months and 10.9 ± 7.02 days, respectively. Two children, who had reversible rejection, had longer surgery-rejection period and short rejection-treatment period in comparison with other six children who had irreversible rejection. Yamazoe et al.[16] studied the prognostic factors for corneal graft recovery after severe corneal graft rejection following PK in which they concluded that a longer interval between corneal graft rejection and treatment was associated with an increased risk of corneal decompensation after graft rejection.

In our series, most of the patients were from remote and rural backgrounds. Thus, failed to follow-up regularly or have a delayed presentation to the center which adversely affected graft outcome, especially in cases where the child was preverbal and unable to communicate problems such as vision loss. Early presentation facilitates early initiation of treatment of rejection which can favor a reversible rejection and better outcome. Dana et al.[3] and McClellan et al.[17] concluded that the rejection is not a significant predictor of failure as most of their rejection episodes were successfully treated in their grafts. Therefore, lower socioeconomic status, long distance from referral centers, EUA and large volume of patients remain major contributing factors for the delayed presentation and late initiation of management in developing countries.

Conclusion

This study showed corneal graft rejection was the leading cause of graft failure of pediatric PK. Though, the incidence (12.1%) of graft rejection in current study was not high in comparison to other studies but the percentage of reversal (25%) was one of the lowest in literature because of delayed presentation and longer interval between corneal graft rejection and treatment. In addition, categorization of the type of graft rejection was very difficult and cumbersome in pediatric patients and did not add any advantage to conventional treatment in terms of treating the graft rejection.

Our study suggest that parents of children undergoing corneal grafting surgery should be more aggressively counseled for rejection symptoms so that they may consult with an ophthalmologist in time to facilitate an early diagnosis and prompt initiation of treatment in graft rejection cases.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Vanathi M, Panda A, Vengayil S, Chaudhuri Z, Dada T. Pediatric keratoplasty. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54:245–71. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stulting RD, Sumers KD, Cavanagh HD, Waring GO, 3rd, Gammon JA. Penetrating keratoplasty in children. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:1222–30. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dana MR, Moyes AL, Gomes JA, Rosheim KM, Schaumberg DA, Laibson PR, et al. The indications for and outcome in pediatric keratoplasty. A multicenter study. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1129–38. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30900-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowden JW. Penetrating keratoplasty in infants and children. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:324–8. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32586-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aasuri MK, Garg P, Gokhle N, Gupta S. Penetrating keratoplasty in children. Cornea. 2000;19:140–4. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200003000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beauchamp GR. Pediatric keratoplasty: Problems in management. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1979;16:388–94. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19791101-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panda A, Vanathi M, Kumar A, Dash Y, Priya S. Corneal graft rejection. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52:375–96. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vajpayee RB, Ray M, Panda A, Sharma N, Taylor HR, Murthy GV, et al. Risk factors for pediatric presumed microbial keratitis: A case-control study. Cornea. 1999;18:565–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma N, Prakash G, Titiyal JS, Tandon R, Vajpayee RB. Pediatric keratoplasty in India: Indications and outcomes. Cornea. 2007;26:810–3. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318074ce2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Javadi MA, Baradaran-Rafii AR, Zamani M, Karimian F, Zare M, Einollahi B, et al. Penetrating keratoplasty in young children with congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy. Cornea. 2003;22:420–3. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200307000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alldredge OC, Krachmer JH. Clinical types of corneal transplant rejection. Their manifestations, frequency, preoperative correlates, and treatment. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99:599–604. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1981.03930010599002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tham VM, Abbott RL. Corneal graft rejection: Recent updates. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2002;42:105–13. doi: 10.1097/00004397-200201000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khodadoust AA, Silverstein AM. The survival and rejection of epithelium in experimental corneal transplants. Invest Ophthalmol. 1969;8:169–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowe MT, Keane MC, Coster DJ, Williams KA. The outcome of corneal transplantation in infants, children, and adolescents. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:492–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Torbak AA. Outcome of combined Ahmed glaucoma valve implant and penetrating keratoplasty in refractory congenital glaucoma with corneal opacity. Cornea. 2004;23:554–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000122704.49054.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamazoe K, Yamazoe K, Shimazaki-Den S, Shimazaki J. Prognostic factors for corneal graft recovery after severe corneal graft rejection following penetrating keratoplasty. BMC Ophthalmol. 2013;13:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-13-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McClellan K, Lai T, Grigg J, Billson F. Penetrating keratoplasty in children: Visual and graft outcome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:1212–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.10.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]