Abstract

Objective:

Gastric ulcer is an important clinical problem, chiefly due to extensive use of some drugs. The aim was to assess the activity of Mumijo extract (which is used in traditional medicine) against acetic acid induced gastric ulcer in rats.

Materials and Methods:

The aqueous extract of Mumijo was prepared. Animals were randomly (n = 10) divided into four groups: Control, sham-operated group (received 0.2 ml of acetic acid to induce gastric ulcer), Mumijo (100 mg/kg/daily) were given for 4 days postacetic acid administration, and ranitidine group (20 mg/kg). The assessed parameters were pH and pepsin levels (by Anson method) of gastric contents and gastric histopathology. Ranitidine was used as reference anti-ulcer drug.

Results:

The extract (100 mg/kg/daily, p.o.) inhibited acid acetic-induced gastric ulceration by elevating its pH versus sham group (P < 0.01) and decreasing the pepsin levels compared to standard drug, ranitidine (P < 0.05). The histopathology data showed that the treatment with Mumijo extract had a significant protection against all mucosal damages.

Conclusion:

Mumijo extract has potent antiulcer activity. Its anti-ulcer property probably acts via a reduction in gastric acid secretion and pepsin levels. The obtained results support the use of this herbal material in folk medicine.

KEY WORDS: Acetic acid, gastric acidity, Mumijo, pepsin, ulcer

Peptic ulcer being one of the most uncontrolled gastrointestinal problems representing a chief health hazards in terms of morbidity and mortality. The etiology of gastroduodenal ulcers is influenced by diverse aggressive and defensive factors for example acid-pepsin secretion, mucosal barrier, mucus secretion, blood flow, cellular regeneration, and endogenous protective agents.[1,2] Mucosal injury may happen when noxious factors “overwhelm” an intact mucosal protection or when the mucosal defense is somehow disrupted.[3]

A number of chemical drugs is accessible for treatment of peptic ulcer, but some side effects and drug interactions make them difficult to use. This is a reason for the development of new anti-ulcer drugs, and the search for novel molecules has been extended to herbal drugs that would offer better protection and decreased relapse.[1] Iran has unique meteorological situation that contributed to the variety of medicinal plants.[4]

In the developed countries, there are several lines of studies about Mumiju and its importance in the treatment of different diseases by health experts and pharmacological organizations. Some have reported the beneficial effects of Mumiju in the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders,[5,6] bone pains, and fractures.[7,8] Asian Mumiju includes 20% minerals, 15% protein, 5% lipids, 5% steroids, and also some carbohydrates, alkaloids, and amino acids.[9,10] Few therapeutic effects of this substance are as follows: Memory improving, neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and anti-oxidant roles.[11,12,13,14,15] The biological effect of Mumiju has been attributed to di-benzo-alpha-pyrone, humic acid, and folic acid contents.[15,16]

With regard to the several beneficial effects mentioned for Mumiju, we hypothesized that the administration of this substance can be effective in the improvement of gastric ulcer. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the gastroprotective effects of this substance by measuring gastric acid and pepsin levels.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats (200-250 g) obtained from the animal room of the Kerman University of Medical Sciences. They were kept in a temperature-controlled environment on a 12:12 h light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. The procedures were in accordance with the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animal of Kerman University Medical Science (IAEC No.: 01/027/04).

Study design

This experimental study was carried out on 40 male Wister rats to study therapeutic effects of Mumijo extract on acetic acid-induced gastric ulcer. Animals were randomly (n = 10 in each group) divided into four groups: (I) Control received normal saline (2 ml/kg), (II) sham-operated group received 0.2 ml of acetic acid to induce gastric ulcer, (III) Mumijo (100 mg/kg/daily) was given for 4 days postacetic acid administration, (IV) ranitidine group received the standard drug, ranitidine (20mg/kg), dissolved in normal saline. Twenty-four hours before each experiment, animals were deprived of food, but free to drink water.

Plant material and extraction

Mumiju was prepared from the local residents of Sardoiyeh in Jiroft/Kerman/Iran. Then it was recognized by botanist from Botanical Survey of Kerman, Iran. Immediately, it was washed thoroughly with running tap water and cut into small pieces. Then the plant material was shade dried at temperature 21-24°C and ground mechanically into a coarse powder and stored in an airtight container. Powdered plant material (150 g) was macerated with 400 ml of distilled water at 21-24°C temperature for 3 days with frequent shaking. After 3 days, the extracts were filtered and to the marc part 300 ml of the solvent was added and allowed to stand for next 2 days at same temperature for second time maceration (re-maceration) and after two days, again filtered similarly. The combined filtrates (macerates) were evaporated in vacuo at 40°C and the dry extract obtained was stored in a vacuum desiccator for future use. All the test samples were administered by oral lavage in a volume of 1 ml/100 g body weight once a day to each rat.[17]

Acetic acid-induced ulcer model

The ulcers were induced by the local application of acetic acid to serosal surface of the stomach as described earlier. Under anesthesia, the midline incision was made, and the stomach was taken out. On the serosal surface of the glandular portion of the stomach, 0.2 ml of 100% acetic acid (anterior gastric wall) was injected. After the treatment, the rats were sacrificed, and stomachs were removed and weighed, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in the paraffin wax, sectioned at 5 μm, stained with hematoxylin and eosin and then examined by the light microscopy.[18]

Evaluation of pepsin

Pepsin levels in the gastric effluent were determined as Anson method. Briefly, 2 ml of 2.5% bovine hemoglobin plus 0.5 ml of 0.3 N HCl and 0.5 ml of gastric effluent were maintained in separate tubes at 37°C for 10 min and then mixed. Mixtures were incubated for 10 min at 37°C, and the reaction was stopped by the addition of 5 ml 0.3 N trichloroacetic acid. After agitation and filtration, optical density was measured at 280 nm by using a spectrophotometer (Unikon 930, Kontron Instrument, Italy). The results were compared to a standard curve, which was generated in an identical manner using known amounts of porcine pepsin (1 μg = 3 peptic units), and were expressed as micrograms of pepsin.[19]

Measurement of intragastric pH

In order to know whether or not the intragastric pH is contributing to the mucosal lesions, intragastric pH was measured 4 days after administration of Mumijo and ranitidine. The pH measurement was performed as previously reported. Laparotomy and pylorus ligation were performed under ether anesthesia. The pylorus of the stomach and esophagocardiac junction were immediately ligated, and the stomach was then removed from each rat, and the gastric contents were collected, centrifuged, and the supernatants were used for pH measurement using pH meter (Ø 50 pH Meter, Beckman, Fullerton, CA, USA).[17]

Ethical considerations

This study protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Committee, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran.

Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean, and statistical significance was evaluated using one-way ANOVA, followed by a Tukey's post-hoc test.[12] Significance of difference was accepted as P < 0.05.

Results

pH of gastric contents

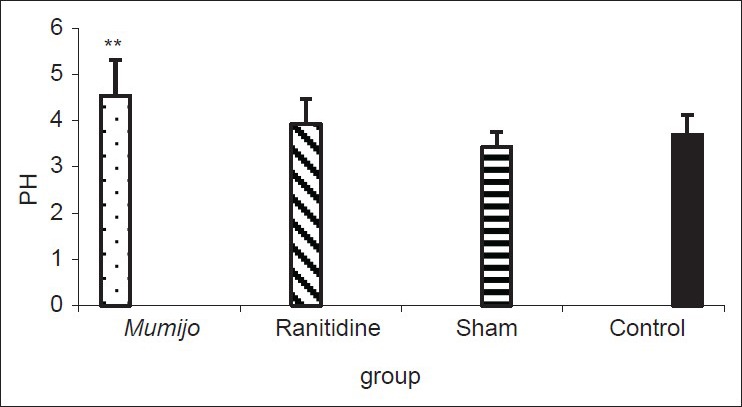

pH data are shown in Figure 1. The pH was 3.43 ± 0.32 and 3.93 ± 0.54, respectively, in sham and ranitidine-treated animals and this difference was not significant. However, when the extract was administered to the acid acetic-treated group, there was a significant increase in pH of gastric contents to 4.54 ± 0.78 (P < 0.01).

Figure 1.

Effect of the extract of Mumijo on gastric pH. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. **P < 0.01, Mumijo versus sham group

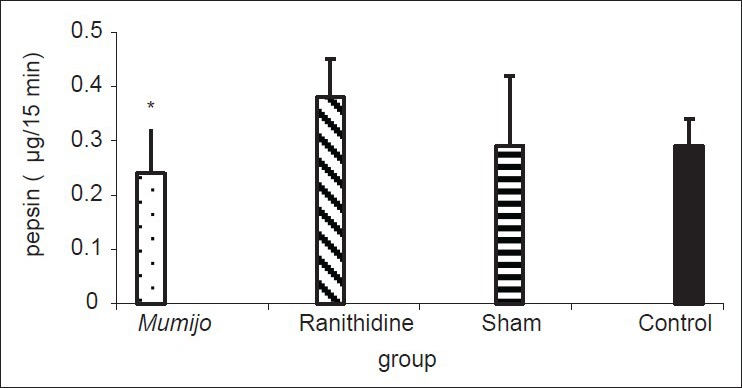

Pepsin levels of gastric contents

Gastric pepsin levels in Mumijo group were significantly lower than ranitidine group (P < 0.05). However, there was no difference between ranitidine or sham groups compared to control [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Effect of the extract of Mumijo on gastric pepsin (μg/15 min). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. *P < 0.05, Mumijo versus ranitidine group

Histopathological findings of gastric tissue

Acid acetic caused histopathological lesions including ulcer with transmural necrosis and degeneration of the gastric tissue. Treatment with Mumijo extract offered significant protection against all damages to mucosa by acid acetic [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs show histopathological changes in the different groups. (a) The normal gastric morphology of the control animals (H and E, original magnification, ×20). (b) The histopathological changes in the gastric tissue of the rats in the sham group. These changes include gastric ulcer with transmural necrosis (H and E, original magnification, ×10). (c) The histopathology changes in the ranitidine group including moderate inflammation with small ulcer (H and E, original magnification, ×10). (d) The histology changes in Mumijo group including extensive repair tissue (H and E, original magnification, ×10)

Discussion

Gastric ulcers are due to inequality between aggressive (acid-pepsin secretion, Helicobacter pylori, bile, increased free radicals, and decreased antioxidants) and defensive factors (mucus, bicarbonate secretion, prostaglandins, blood flow and the process of restitution, and regeneration after cellular injury) of the gastric mucosa.[1,2,20] In the present study, it was recognized that the Mumijo had protective effects against the gastric ulcer induced by acetic acid. Protective effects of Mumijo on the stomach may be related to its anti-secretary action as our results showed that the Mumijo reduced the amount of gastric acidity and pepsin levels in the damaged stomach.

According to the some reports, Mumijo has significant repairing effects. It was shown that the presence of some polyphenols compounds such as fulvic acids (FAs), 4-methoxy-6-carbomethoxybi-phenyl, tirucallane-type triterpenoids, and benzoic acid in Mumijo samples have very important role in decreasing of acid-pepsin secretion, cell shedding, and gastric ulcer index. Also antioxidant activity, cellular repairing, and regenerative functions reported. It also can increase the mucin secretion and carbohydrate/protein ratio which have very important role as anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory effects as reported by other researchers,[2,21,22,23] so they stated its use in gastric ulcer and wound healing. In general, Mumijo has an expected broad biochemical and pharmacological activities due to its contents of FA and other antioxidant materials. FAs have been taken orally as a therapy for gastritis, stomach ulcers, and colitis.[24,15]

In our study, it was also recognized that Mumijo has regenerative and repairing effects as shown in the histopathological findings. It was reported that Mumijo pretreatment at the dose of 100mg/kg orally reduced ulcer index in immobilization and aspirin induced gastric ulcers. In duodenal ulcers also, Mumijo pretreatment significantly reduced the incidence of ulcers induced by cysteamine in rats and histamine in guinea pigs.[6] It may be partly related to its role in decreasing of acid-pepsin secretion as mentioned above but the other functions of this plant is also important. In some studies, the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of this plant are declared. It was shown, that alterations in the antioxidant status following ulceration, implying that free radicals may be associated with gastric mucosal damage in rats.[25]

The reactive oxygen species generated by the metabolism of arachidonic acid, platelets, macrophages, and smooth muscle cells may contribute to gastric mucosal damage. Therefore, by scavenging of free radicals, it may be useful for protecting the gastric mucosa from oxidative damage.[26] Mumijo as antioxidant, inhibit lipid peroxidation and other free radical-mediated process, and therefore, they protect the human body from several diseases attributed to the reactions of radicals.[27]

Additionally, Mumijo has significant anti-inflammatory effects in chronic inflammation. There are some evidence showing the effects of Mumijo on increasing superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase activities in rats.[28] Mumijo can significantly decrease carrageenan-induced edema in rat paw.[29] In some studies, it has also been reported that Mumijo has anti-allergic effects on histamine release and causes mast cells degranulation.[30] Antioxidant properties of Mumijo extract can be attributed to the presence of dibenzo-pyrones and FA.[24]

On the other hand, anti-anxiety activity and anti-stress effects of Mumijo have roles in healing of gastric ulcer as stated by Frawley and Lad, who indicated that Mumijo had significant anxiolytic and anti-stress activity.[31] Furthermore, due to bacteriostatic and anti-inflammatory action, Mumijo extract facilitates the process of wound cleaning from necrotic tissues, granulation, and epithelization and decreases the period of wound healing.[32]

Overall, the results of the present study showed that Mumijo administration has gastroprotective effects in acetic acid-induced ulcers through decreasing gastric acid and pepsin. Furthermore, the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of this extract can be mentioned as probable mechanisms to improve gastric tissues. However, further studies are required to determine other functional mechanisms of Mumijo.

Acknowledgment

The present study was financially supported by the Neuroscience Research Center of Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Neuroscience Research Center of Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Akhtar MS, Akhtar AH, Khan MA. Antiulcerogenic effects of Ocimum basilicum extracts, volatile oils and flavonoid glycosides in albino rats. Int J Pharmacognosy. 1992;30:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goel RK, Bhattacharya SK. Gastroduodenal mucosal defence and mucosal protective agents. Indian J Exp Biol. 1991;29:701–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laine L, Takeuchi K, Tarnawski A. Gastric mucosal defense and cytoprotection: Bench to bedside. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:41–60. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghannadi A, Zolfaghari B, Shamashian S. Necessity, importance and applications of traditional medicine in different ethnic. J Tradit Med Islam. 2011;13:161–76. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosal SK, Kumar Y, Srivastava R, Goel RK, Dey R, Bhattacharya SK. Anti-ulcerogenic activity of fulvic acids and 4’-methoxy-6-carbomethoxybiphenyl isolated from shilajit. Phytother Res. 1988;2:187–91. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goel RK, Banerjee RS, Acharya SB. Antiulcerogenic and antiinflammatory studies with shilajit. J Ethnopharmacol. 1990;29:95–103. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(90)90102-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shakurov AS. Effect of “mumie” on bone regeneration and blood alkaline phosphatase in experimental fractures of the tubular bones. Ortop Travmatol Protez. 1965;26:24–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kel’ginbaev NS, Sorokina VA, Stefanidu AG, Ismailova VN. Treatment of long tubular bone fractures with Mumie Assil preparations in experiments and clinical conditions. Eksp Khir Anesteziol. 1973;18:31–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mirza MA, Alam MN, Faiyazuddin M, Mahmood D, Bairwa R, Mustafa G. Shilajit: An ancient panacea. Int J Curr Pharmaceut Rev Res. 2010;1:2–11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garedewa A, Feist M, Schmolz E, Lamprecht I. Thermal analysis of mumiyo, the legendary folk remedy from the Himalaya region. Thermochim Acta. 2004;417:301–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aiello A, Fattorusso E, Menna M, Vitalone R, Schröder HC, Müller WE. Mumijo traditional medicine: Fossil deposits from antarctica (chemical composition and beneficial bioactivity) Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2011. 2011 doi: 10.1093/ecam/nen072. 738131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghosal SL, Jaiswal AK, Bhattacharya SK. Effects of Shilajit and its active constituents on learning and memory in rats. Phytother Res. 1993;7:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spassov V. Memory effects of the natural product Mumyo on the water maze in rats. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1994;4:396. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhattacharya SK, Sen AP, Ghosal S. Effects of shilajit on biogenic free radicals. Phytother Res. 1995;9:56–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agarwal SP, Khanna R, Karmarkar R, Anwer MK, Khar RK. Shilajit: A review. Phytother Res. 2007;21:401–5. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhattacharya SK, Ghosal S. Effect of Shilajit on rat brain monoamines. Phytother Res. 1992;6:163–4. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phaechamud TJC, Wetwitayaklung P, Limmatvapirat C, Srichan T. Some biological activities and safety of mineral pitch (mumijo) Silpakorn Univ Sci Technol J. 2008;2:7–17. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takagi K, Okabe S, Saziki R. A new method for the production of chronic gastric ulcer in rats and the effect of several drugs on its healing. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1969;19:418–26. doi: 10.1254/jjp.19.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nabavizadeh Rafsanjani F, Vahedian J. The effect of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus on basal and distention-induced acid and pepsin secretion in rat. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2004;66:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canoru A, Üek R, Atamer A, Dursun M, Turgut C, Nelu EG, et al. Protective effects of vitamin E selenium and allopurinol against stress-induced ulcer formation in rats. Turk J Med Sci. 2001;31:199–203. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rajic A, Akihisa T, Ukiya M, Yasukawa K, Sandeman RM, Chandler DS, et al. Inhibition of trypsin and chymotrypsin by anti-inflammatory triterpenoids from Compositae flowers. Planta Med. 2001;67:599–604. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Talbert R. Grass Valley, California: A Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of California College of Ayurveda; 2004. Shilajit; a materia medica monograph. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tiwari P, Ramarao P, Ghosal S. Effects of Shilajit on the development of tolerance to morphine in mice. Phytother Res. 2001;15:177–9. doi: 10.1002/ptr.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schepetkin IA, Khlebnikov AI, Kwon BS. Medical drugs from humus matter: Focus on mumie. Drug Dev Res. 2002;57:140–59. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Repetto MG, Llesuy SF. Antioxidant properties of natural compounds used in popular medicine for gastric ulcers. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2002;35:523–34. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2002000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hahm KB, Park IS, Kim YS, Kim JH, Cho SW, Lee SI, et al. Role of rebamipide on induction of heat-shock proteins and protection against reactive oxygen metabolite-mediated cell damage in cultured gastric mucosal cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;22:711–6. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00406-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Czinner E, Hagymási K, Blázovics A, Kéry A, Szoke E, Lemberkovics E. The in vitro effect of Helichrysi flos on microsomal lipid peroxidation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;77:31–5. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhattacharya SK, Sen AP, Ghosal S. Effects of shilajit on biogenic free radicals. Phytother Res. 1995;9:56–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghosal S. Chemistry of shilajit, an immunomodulatory ayurvedic rasayan. Pure Appl Chem (IUPAC) 1990;62:1285–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghosal S, Lal J, Singh SK, Dasgupta G, Bhaduri J, Mukhopadhyay M, et al. Mast cell protecting effects of shilajit and its constituents. Phytother Res. 1989;3:249–52. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frawley D, Lad V. 2nd ed. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass; 2004. The Yoga of Herbs: An Ayurvedic Guide to Herbal Medicine; p. 265. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shakirov DS. Experimental treatment of infected wounds with mumie asil. Eksp Khir Anesteziol. 1969;14:36–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]