Abstract

Background:

Pharmaceutical industries worldwide are heavily involved in aggressive drug promotions. Physician targeted promotion through medical representatives is one of the most common tactic for drug promotion by pharmaceutical drug companies. WHO states that medical representatives to work in an ethical way should make available to prescribers and dispensers complete and unbiased information for each product discussed; therefore this study aimed to evaluate the ethics in the medical brochures of generic pharmaceutical companies that are given through medical representatives to physicians in Iraq.

Materials and Methods:

An observational, cross-sectional study was conducted in Iraq – Baghdad from February to April 2014. Promotional drug brochures were collected mainly from pharmaceutical exhibition during attendance of medical conferences that were sponsored by generic pharmaceutical companies. Evaluation of each brochure was based primarily on WHO criteria for ethical medicinal drug promotion. The availability of emotional pictures in each brochure was also examined. Furthermore, references were checked to find their retrievability, source, and authenticity of presentations.

Results:

Most medical brochures were for antibiotics, and drugs for cardiovascular diseases. All brochures mention drug name, with its active ingredient and indication, but there is a significant absence for drug interaction, while drug side effects and contraindications if present were written in a small font. Emotional picture presented in 70% of brochures. Reference citation was present in 72% of brochures, however only 75% of references in these brochures were correct.

Conclusions:

The information that is provided in medical brochures is biased and mainly persuasive since it is mainly focusing on the positive aspect of drug therapy.

KEY WORDS: Brochures, ethical criteria, generic pharmaceutical companies

Advertisement is a key element of marketing strategy at which the advertising messages consist of a combination of information and persuasion.[1] WHO define drug promotion or advertisement as all informational and persuasive activities by manufacturers and distributors, the effect of which is to induce the prescription, supply, purchase and/or use of medicinal drugs.[2] Pharmaceutical industries worldwide are heavily involved in aggressive drug promotions.[3,4] Physician targeted promotion through medical representatives is one of the most common tactic for drug promotion by pharmaceutical drug companies.[5,6] Medical representatives during their contact with Physicians promote their drugs through verbal in-office presentations which are usually accompanied by promotional advertising brochures, free medical samples, and possibly gifts such as meals or other promotional items.[7,8] WHO states that medical representatives to work in an ethical way should make available to prescribers and dispensers complete and unbiased information for each product discussed, such as an approved scientific data sheet or other source of information with similar content;[2] however there is a debate about the accuracy and reliability of information that was given from drug companies through MRs to physicians not only in developed countries[9,10] but also in developing countries like Yemen[8] and Iraq.[11] Therefore this study aimed to evaluate the ethics in the medical brochures of generic pharmaceutical companies that are given through medical representatives to physicians in Iraq.

Materials and Methods

This observational, cross-sectional study was conducted in Iraq - Baghdad from February to April 2014. Promotional drug brochures were collected mainly from pharmaceutical exhibition during attendance of medical conferences that sponsored by generic pharmaceutical companies, and to little extent by direct request from medical representatives of generic drug companies after they complete their daily promotion to physicians. Collected brochures were then explored to exclude the following materials: Literature promoting medicinal devices and equipments (ECG, insulin pump, blood glucometer, etc.), reminder advertisements (reminder advertisements do not present any therapeutic indication for the promoted drug).[2] Advertisement about dental or herbal products, drugs name list, and brochures promoting more than one drug in the same brochure.

Evaluation of each brochure was based primarily on WHO criteria for ethical medicinal drug promotion at which each promotional literature should contain the following information:[2]

The name of the active ingredient (s) using either international nonproprietary names (INN) or the approved generic name of the drug

The brand name

Content of active ingredient (s) per dosage form or regimen

Name of other ingredients known to cause problems

Approved therapeutic uses

Dosage form or regimen

Side-effects and major adverse drug reactions

Precautions, contra-indications and warnings

Major interactions

Name and address of manufacturer or distributor

Reference to scientific literature as appropriate.

In addition to all the above points, font size for each criteria was also monitored, besides that the availability of emotional pictures in each brochure was also examined. Furthermore, References were checked to find their retrievability, source (if it is from product leaflet, medical book or journal article), and authenticity of presentations. Each reference was read carefully to find if the study that cited as a reference in the promotional brochure is:

Old dated or updated. When the study is old dated, a careful search in the net for the new studies on the same subject was done, to check if these new studies confirm that old study or contradict it

Providing misleading information, by either exaggerating the benefits, or by minimizing the risks of the drug, or by withhold certain information to mask a negative attitude toward their promoted product

Providing wrong information, by mentioning something that not actually present in the cited article

Funded by pharmaceutical drug company

Not related to any pharmaceutical information, but instead it is related to disease or company sales in the world.

Additionally each brochure was checked to find if all references mentioned were cited to defend company claims about the product.

Results

The medical brochures were collected from 12 different Arabic and non Arabic generic pharmaceutical companies as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of examined brochures according to different pharmaceutical companies

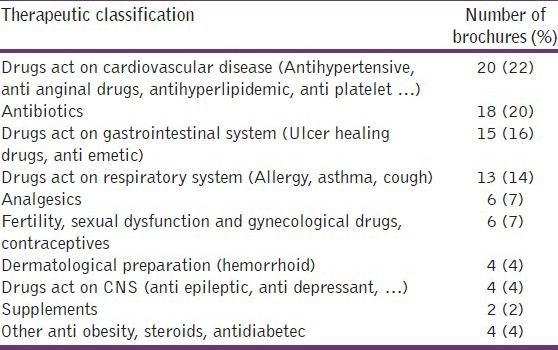

Table 2 showed that most medical brochures were for antibiotics, drugs of chronic diseases like, hypertension, angina, dyslipidemia, asthma, and peptic ulcer.

Table 2.

Therapeutic category of drugs promoted in promotional material

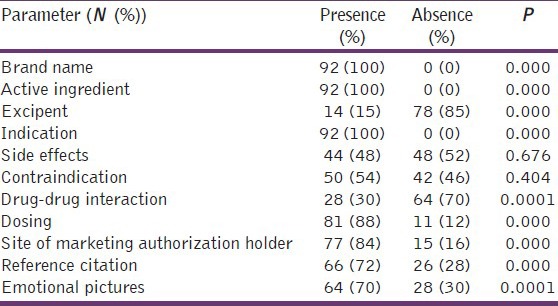

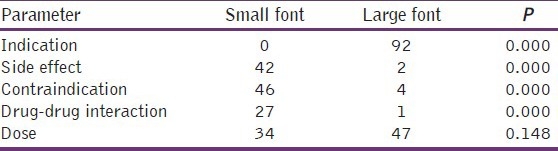

Table 3 showed a significant presence of the brand name of the product (100%), its main active ingredient (100%), indication (100%), drug dosing (88%), site of marketing authorization holder (84%), and reference citation to defend product claims (72%); Additionally emotional pictures were significantly present (70%) in medical brochures, but there is a significant absence for mentioning excipent (15%) with each product and drug - drug interaction (30%). Drug side effects and contraindications were present in 48% and 54% of brochures respectively but without achieving statistical significance. Furthermore, this study showed in Table 4, that only drug indication was written in a large font, while drug side effects and contraindications were significantly written in small fonts.

Table 3.

Percent of compliance of pharmaceutical companies with ethical criteria of drug promotion through their medical brochures

Table 4.

The font size that used in medical brochures for informing physicians with drug indication, side effect, contraindication, drug-drug interaction and drug dosing

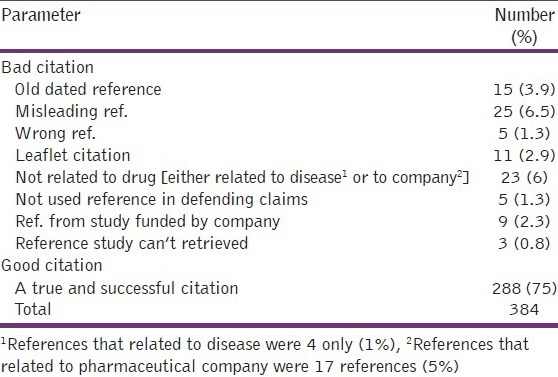

Tables 3 and 5 showed that 72% generic companies defend their claims about the promoted product in the brochure by reference citation, but only 75% of these references that used were accurate and real, while the remaining 25% of references were associated with ethical problems, like using old dated reference, misleading reference, wrong reference, citation based on product leaflet, references that were based on studies that funded by drug company. 6% of the references were not used to defend claims about the drug effectiveness but instead used to present information about disease facts like prevalence and mortality rate, or about drug company sales around the world. Less than 1% of references cannot be retrieved.

Table 5.

Ethical problems with references that used in medical brochures by pharmaceutical companies to confirm their claims about their product

Discussion

This study showed that most medical brochures were focusing on treating cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and respiratory diseases, similarly brochures in Nepal focus mainly on cardiovascular drugs, ulcer healing drugs and those for treating respiratory disorders,[12] additionally it was found in this study that antibiotics were present in 20% of examined brochures, this may be because antibiotics are one of the most commonly dispensed medications in hospital setting,[13] and since antibiotics considered as prescription only medications so it is reasonable to find that antibiotics are the most commonly promoted drugs to physicians.[14]

This study showed that there was a significant mentioning of the brand name of the product (100%), its active ingredient and indication (100%), drug dosing (88%) and the site of marketing authorization holder (84%) in the brochures of generic pharmaceutical companies in Iraq, a similar finding was obtained through evaluation of brochures in Saudi Arabia and Nepal.[12,15] The result of this study also showed that there is a significant absence of mentioning excipent (15%), and drug–drug interaction (30%) in the evaluated brochures, similarly in India, there is a significant lack of excipent mentioning in brochures,[16] while drug-drug interaction was mentioned in only 33% of examined brochures that were given to Libyan physicians.[17]

Table 3 showed that side effects and contraindications of promoted drugs were present in 48% and 54% of examined brochures, respectively, this finding is consistent to that finding in Zimbabwe, at which side effects and precautions were missing in more than 50% of brochures,[18] on the other hand this percent for missing information about drug side effects or contraindications is much lower than that found in other studies as in India and Nepal;[12,16] although the difference is apparent in numerical values, but in reality there is no any difference since this study showed in Table 4, that the majority of information about drug side effects and contraindication were written in small font, which mean although the information about drug side effects and contraindications are physically present but they are actually absent.

Regarding emotional pictures, this study showed that it was used in 70% of brochures, this percent is much higher than that found in non Arabic countries[16] and lower than that found in Arabic countries like Libya.[17]

Tables 3 and 5 showed that 72% generic companies defend their claims about the promoted product in the brochure by reference citation, similarly in the Libyan study 70% of brochures were associated with reference citation[17] but only 75% of these references that used were accurate and real, while in other studies a percent for accurate reference citation in brochures was variable ranging from 54% to -85%,[19,20] while Cardarelli et al. found the ratio of reference citation is 75% which is exactly similar to that find in this study.[21]

For reference studies which are un-retrievable are quite low in this study than that in other studies[17,22] but this percent is more close to the finding of Cooper et al.[23]

This study showed that reference citation based on product leaflet occur in 2.3% of brochures, while reference citation for studies funded by drug company occurred in 2.9% of cases, furthermore reference citations for defending claims about the company sales and innovations were found in 5% of brochure references, collectively all these citations are either based or related to manufacturer information; Similarly in other study it was found that references that related to manufacture information accounting for 10% from the cited references.[22]

This study showed that misleading reference citations were present in 6.5% of brochures, close to this finding misleading information was present in 5% of written pharmaceutical advertisement in UAE.[24] Regarding wrong reference citation, there is no any similar study in the world in this regard except a closely related finding in a study which was done in Pakistan,[25] which divide misleading reference citation into many parts like exaggerated, ambiguous or false citation, in that study, false misleading citation can be considered to be similar in its meaning to the term of wrong citation which used in the current study, however the percent of wrong citation in brochures in that study was slightly higher than that found in this study, this difference may be due to different sample size, or may due to different nature of pharmaceutical company brochures that examined in these two studies; whatever the cause of difference, this less percent of wrong reference citation is a good indicator for ethical and rational promotion through medical brochure.

This study also showed a 3.9% of using old dated reference. Citing old dated reference to defend certain claims is not a strange behavior from pharmaceutical companies to promote their products which may be reasonably occur for old generation drugs to which new generations become available as a drug of choice, this explanation is more applicable with antibiotics since bacterial resistance is more common with old antibiotics,[26] and the antibiotic of choice for certain infection many years ago may become ineffective one nowadays.

Limitation of this study is the small sample size of collected brochures, in addition to collecting the brochures from generic companies in Baghdad governorate only. However, it is one of the first studies in the world that focus on brochures of generic drug companies only, and it is the first study that done to evaluate the reliability and accuracy of written information in medical brochures that distributed by medical representatives to physicians in Iraq.

Conclusion

The information that provided in medical brochures is biased and mainly persuasive since it is mainly focusing on the positive aspect of drug therapy especially drug indication with weak focusing on drug side effects, contraindications or interactions.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Ferner RE, Scott DK. Whatalotwegot-the messages in drug advertisements. BMJ. 1994;309:1734–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6970.1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geneve: 1988. World Health Organization. Ethical Criteria for Medicinal Drug Promotion; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lal A. Pharmaceutical drug promotion: How it is being practiced in India? J Assoc Physicians India. 2001;49:266–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenthal MB, Berndt ER, Donohue JM, Frank RG, Epstein AM. Promotion of prescription drugs to consumers. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:498–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thapa BB. Ethics in Promotion of Medicine (editorial) DBN. 2006;18:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Handa M, Vohra A, Srivastava V. Perception of physicians towards pharmaceutical promotion in India. J Med Market: Device, Diagnostic and Pharmaceutical Marketing. 2013;13:82–92. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zipkin DA, Steinman MA. Interactions between pharmaceutical representatives and doctors in training: A thematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:777–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Areefi MA, Hassali MA, Ibrahim MI. Physicians’ perceptions of medical representative visits in Yemen: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:331. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziegler MG, Lew P, Singer BC. The accuracy of drug information from pharmaceutical sales representatives. JAMA. 1995;273:1296–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lieb K, Brandtönies S. A survey of German physicians in private practice about contacts with pharmaceutical sales representatives. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107:392–8. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mikhael EM, Alhilali DN, AlMutawalli BZ, Toma NM. The reliability and accuracy of medical and pharmaceutical information that were given by drug companies through medical representatives to Iraqi physicians. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2014;6:627–30. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alam K, Shah AK, Ojha P, Palaian S, Shankar PR. Evaluation of drug promotional materials in a hospital setting in Nepal. South Med Rev. 2009;2:2–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharif S, Al-Shaqra M, Hajjar H, Shamout A, Wess L. Patterns of drug prescribing in a hospital in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Libyan J Med. 2008;3:10–2. doi: 10.4176/070928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bbosa GS, Mwebaza N, Odda J, Kyegombe DB, Ntale M. Antibiotics/antibacterial drug use, their marketing and promotion during the post-antibiotic golden age and their role in emergence of bacterial resistance. Health. 2014;6:410–25. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Aqeel SA, Al-Sabhan JF, Sultan NY. Analysis of written advertising material distributed through community pharmacies in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Pharm Pract (Granada) 2013;11:138–43. doi: 10.4321/s1886-36552013000300003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mali SN, Dudhgaonkar S, Bachewar NP. Evaluation of rationality of promotional drug literature using World Health Organization guidelines. Indian J Pharmacol. 2010;42:267–72. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.70020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alssageer MA. Analysis of informative and persuasive content in pharmaceutical company brochures in Libya. Libyan J Pharm Clin Pharmacol. 2013;2:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sibanda N, Gavaza P, Maponga CC, Mugore L. Pharmaceutical manufacturers’ compliance with drug advertisement regulations in Zimbabwe. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61:2678–81. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.24.2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mejía R, Avalos A. Printed material distributed by pharmaceutical propaganda agents. Medicina (B Aires) 2001;61:315–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keng A, Coley RM. Evaluating the accuracy of citations in drug promotional brochures. Ann Pharmacother. 1994;28:1231–5. doi: 10.1177/106002809402801102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cardarelli R, Licciardone JC, Taylor LG. A cross-sectional evidence-based review of pharmaceutical promotional marketing brochures and their underlying studies: Is what they tell us important and true? BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keng A, Coley RM. Evaluating the accuracy of citations in drug promotional brochures. Ann Pharmacother. 1994;28:1231–5. doi: 10.1177/106002809402801102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper RJ, Schriger DL. The availability of references and the sponsorship of original research cited in pharmaceutical advertisements. CMAJ. 2005;172:487–91. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharif SI, Abduelkarem AR. Analysis of written pharmaceutical advertisement in Dubai and Sharjah. Saudi Pharm J. 2008;16:252–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rohra DK, Gilani AH, Memon IK, Perven G, Khan MT, Zafar H, et al. Critical evaluation of the claims made by pharmaceutical companies in drug promotional material in Pakistan. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2006;9:50–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy SB. The 2000 Garrod lecture. Factors impacting on the problem of antibiotic resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;49:25–30. doi: 10.1093/jac/49.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]