Abstract

This paper provides a comprehensive overview of the recent obesity prevention–related food policies initiated in countries worldwide. We searched and reviewed relevant research papers and government documents, focusing on those related to dietary guidelines, food labeling, regulation of food marketing, and policies affecting food prices. We also commented on the effects and challenges of some of the related policy options. There are large variations regarding what, when, and how policies have been implemented across countries. Clearly, developed countries are leading the effort, and developing countries are starting to develop some related policies. The encouraging message is that many countries have been adopting policies that might help prevent obesity and that the support for more related initiatives is strong and continues to grow. Communicating information about these practices will help researchers, public health professionals, and policy makers around the world to take action to fight the growing epidemic of obesity and other nutrition-related diseases.

Keywords: Food policy, Obesity, Overweight, Prevention, Intervention, International

Introduction

Obesity has become a global epidemic, and its prevalence continues to increase. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 1.4 billion adults and 40 million children are overweight, whereas more than 10% of people worldwide are obese [1]. Although obesity once was considered a health problem of developed countries, it has been increasing rapidly in developing countries, especially in urban settings and in high-income groups [1, 2••]. Obesity increases the risk for a variety of noncommunicable, chronic diseases [3••].

Recent studies and reports from influential health organizations call on policy- and population-based approaches to change the “obesogenic” environment to fight the obesity epidemic [4–7]. Public health experts and advocacy organizations suggest that policy makers at various levels—local, regional, national, and international—take coordinated action to address obesity.

During the past decade, the United States and European countries implemented several policies that might contribute to the prevention of childhood obesity, including school-based policies, such as regulation of vending machines inside schools [8]; community-based ones, such as zoning to restrict fast food outlets [9]; food industry–based ones, such as calorie labeling and value sizing [10]; and broad, society-wide ones, such as regulating food advertising to young people [11]. Other countries also have been developing and implementing obesity prevention–related policies.

In this article, we review recent obesity prevention–related national and regional government food policies in selected countries that affect food systems and people's food consumption, such as national dietary guidelines and policies and regulations regarding food labeling, marketing, and pricing. We also comment on the effects and challenges of some related policy options. Communicating information about these practices may help researchers, public health professionals, and policy makers around the world to take action to fight the growing obesity epidemic as well as other nutrition-related diseases.

Conceptual Framework: Food Policy Options and the Need for Obesity Prevention

Globalization, including trade, culture, and personal exchanges and the development of economies and technologies, has brought the benefits of more abundant, affordable food; dramatic shifts in people's lifestyles; and improved health conditions for people in many countries worldwide. However, these changes also have fueled negative consequences, including more unhealthy eating patterns, sedentary lifestyles, and the growing global epidemic of obesity and other lifestyle-related noncommunicable chronic diseases [12••].

Obesity is the result of a positive energy balance that occurs when energy intake (from food consumption) exceeds energy expenditure (i.e., physical activity and inactivity). Some research suggests it might be easier and more effective to help people reduce their energy intake than increase their energy expenditure, although this is still a matter of debate. People's food consumption is affected by many individual (e.g., food preference), family (e.g., family income), and social factors (e.g., food availability and food prices) as well as some international factors, such as global trade policies. Several food policy options have been proposed, and various policies have been implemented by different countries to promote healthy diets. The NOURISHING framework provides a useful approach for adopting food policies that promote healthy diets [13••]. To improve food consumption and prevent obesity, related food policies would aim to increase (decrease) the availability, affordability, and acceptability of healthy (unhealthy) food choices in various settings (e.g., home, school, workplace, and community).

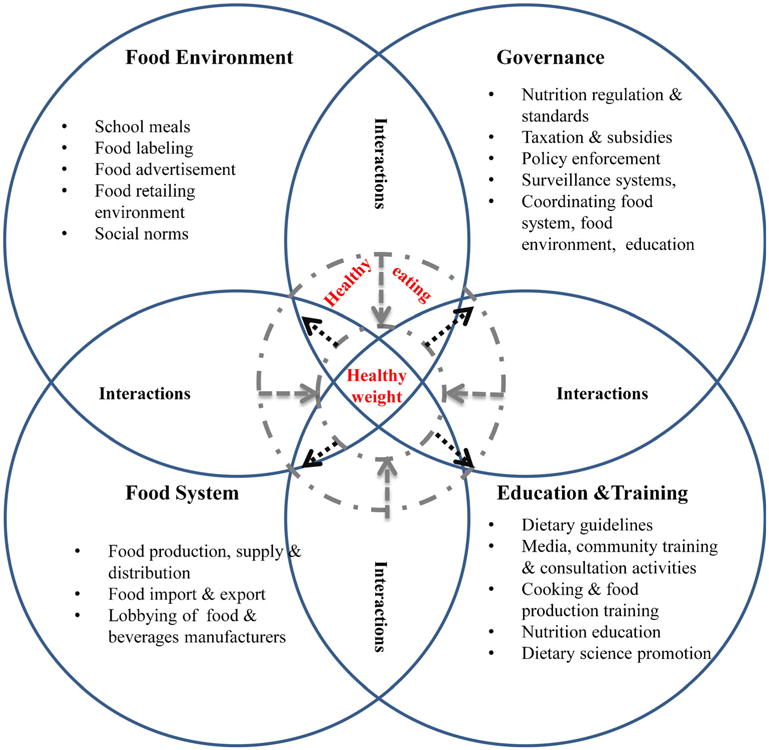

The development and implementation of national and regional government food policies also are affected by multiple factors, including culture, tradition, the political system, and the support of various stakeholders within a society. Successful behavior changes can be achieved only through synergistic interactions and the interoperability of policies from different constituent systems. Ideal policy design at all levels should render a seamless platform targeting individual behavior. Policies should be designed to change the context in which the undesired dietary patterns occur, that is, the food environment individuals confront daily. Attempts to change the food environment must address the food system, which should be overhauled and reengineered to create a healthy food environment. To sustain the desired behavioral change, continuous education and training must be provided to equip individuals with the necessary knowledge and skills to adapt to the new environment. Achieving synergy among all these factors and policies requires institution of enforcement measures and administrative oversight from local and national governments.

High-leverage policies are intended to change original structures and create a context in which people have less chance to form or maintain undesired behaviors. For example, restricting fast foods in school cafeterias can make unhealthy food inaccessible to children, whereas school policies on nutrition education can equip students with more skills and knowledge about how to balance their energy intake and expenditure in such a changing food environment. This dual approach in children actually increases their resilience when faced with unhealthy consumption environments in adulthood. However, most policies target only one aspect of the food environment, thus failing to harness the power of more systematic policy adoptions that might affect more significant changes in unhealthy food environments.

Figure 1 illustrates the complex food policy environment and the interactive policy approaches to obesity prevention. Note, however, that there often is overlap among the domains of food policy options. We propose this conceptual model based on those proposed by other researchers and related research in the field, including the NOURISHING framework [13••].

Fig. 1. Target options and synergized effects of food policies for obesity prevention.

Obesity Prevention–Related Food Policy Implemented by Countries Worldwide

Although it is extremely challenging, if not impossible, to provide an exhaustive list of all relevant food policies implemented by countries to prevent obesity, increasing research helps provide greater understanding of such practices worldwide. For example, some reports presented at the recent Bellagio Conference on Program and Policy Options for Preventing Obesity in Low- and Middle-Income Countries provide some useful insights [12••]. Our team searched related papers published in recent years. We also searched government and organizational Web sites for related policy documents and reports to identify food-related policies relevant to obesity prevention. We provide numerous examples based on research and government reports to which we have had access. Because of the scope of the research, we did not attempt to provide an exhaustive list of all food-related policies worldwide.

Table 1 summarizes recent food policy changes in 22 countries or regions in terms of national nutrition education efforts (i.e., dietary guidelines), school-focused food policy, food labeling, food marketing, and food pricing. We highlight the practices of some countries in the following sections. In many countries, issuing national dietary guidelines has become standard practice during the past three decades, aiming to promote healthy diets for good health. These efforts also help in obesity prevention. School-related policies aimed at preventing childhood obesity have drawn the strongest support and have been implemented in many countries with more success than that achieved by other types of food policies.

Table 1. Food policies to prevent obesity in selected countries.

| Policy type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Country | School-focused | Labeling: packaging and restaurants | Marketing | Pricing | Nutrition education/national dietary guidelines |

| Australia [13••, 69] | 2010 National Healthy School Canteens Guidelines | Health star rating system for front-of-pack labeling | Australian Food and Grocery Council-issued self-regulated codes for marketing unhealthy foods to children | Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code— Standard 1.2.7—Nutrition, Health and Related Claims: issued by Department of Health and Aging in 2013 | |

| Bangladesh [70] | Infant and young children feeding policies | ||||

| Brazil [71, 72] | As of 2001, regulations require 70% of food to be fresh or minimally processed As of 2009, the law requires 30% of food to be purchased from local family farms and their cooperatives |

National Food and Nutrition Policy (NFNP) issued in 1999, updated in 2011; includes regulatory actions for nutritional labeling | Regulations for food marketing to infants and young children, since 2006 | National Food and Nutrition Surveillance System; provides data on dietary and nutritional information at population level Food Guide for the Brazilian Population issued in 2006; guide for children under age 2 issued in 2002 Interministerial network to promote dietary and nutritional education since 2012 NFNP issued in 1999 and updated in 2011; health educators can promote healthy diets with media |

|

| Canada [73, 74] | Provincial requirement that all prepackaged foods have nutrition labeling | Canada's Food Guide, since 1942 | |||

| Chile [75] | Food Labeling and Advertising law in effect since 2012: front-of-pack labeling | Food Labeling and Advertising law in effect since 2012: restricts unhealthy food marketing to children | |||

| China [76] | Guidelines on snacks for children and adolescents, issued in 2008 | General Rules for Nutrition Labeling of Prepackaged Foods (2013) |

Chinese Dietary Reference Intakes (2000–2013 revision) 121 Health Action Strategy: 10,000 steps a day, the balance of eating and activity and a healthy life, issued by Minister of Health in 2007 |

||

| Denmark [52, 77] | Tax on saturated fat (issued in 2011, removed in 2012) | ||||

| Finland [72] | Consumer Ombudsman's Guidelines on Marketing to Children | ||||

| France [52, 77] | Prohibition on food marketing in schools | Tax on SSBs (2012) | |||

| Hungary [52, 77] | Tax imposed in 2011 on foods with high fat, sugar, or salt content | ||||

| India [78] | Complete ban on sale of junk foods and carbonated beverages near schools (2013) | Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI)-issued guidelines recommending <10% trans-fats in food products | Advertising Standards Council of India regulation of junk food advertising FSSAI-issued self-regulation codes in food advertising |

||

| Ireland [44] | New restrictions on advertising of HFSS food and drinks targeting children (2013) | ||||

| Mexico [79] | National Agreement for Nutritional Health (2011) 1. Ban on soda and other unhealthy foods in schools |

Front-of-package labeling | Regulation of food and beverage marketing to children | Mexican Social Security institute prevention programs on television and other media | |

| The Netherlands [80, 81] | Voluntary food rules and recommendations for schools regarding foods and beverages | “Healthy choice” logo on food packages | Ban on food advertising in kindergarten and primary school settings | Healthy diet guidelines issued in 1986 and 2006 Mass media campaigns: “Don't Get Fat,” “Balance Day” | |

| New Zealand [13••, 69] | Health star front-of-pack labeling system | Restrictions on advertising of unhealthy food to children issued in 2008 (New Zealand Television Broadcasters' Council) The Advertising Standards Authority Code for Advertising of Food to Children (2010) National Heart Foundation's 2011 position statement on food marketing to children |

Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code—Standard 1.2.7—Nutrition, Health and Related Claims, issued by Department of Health and Aging in 2013 | ||

| Pacific Islands [82] | Fiji: Requirement of labeling information on sodium and trans-fatty acid values Solomon Islands: warning labels for foods high in fat |

French Polynesia: taxes on SSBs, sweets, ice cream, since 2000 Nauru: “sugar levy” of 30% on high-sugar products, since 2007 Cook Islands: import duty on SSBs since 2013 Fiji: “soda tax” since 2006 |

|||

| Singapore [83] | Health Promotion School Canteen programs in schools | Healthier Choice Symbol to identify foods low in calories and fat | Healthier Hawker Food Programme to add healthier ingredients to daily dishes | ||

| South Africa [84] | Up to 25% rebate on purchase of healthy foods at a national supermarket chain (Vitality HealthyFood) | South African Food Based Dietary Guidelines (HealthyFood) | |||

| South Korea [85-87] | The Special Act on Children's Dietary Life Safety Management (2009) | Food labeling standards issued by Ministry of Health and Welfare and Korea Food and Drug Administration Health Functional Food Act of 2010 Standards and Specifications for Cooked Foods in the Restaurant |

Restrictions on sale and advertising to children of food high in calories and low in nutritional value | Recommended Dietary Allowances for Koreans (1962–2000) National Nutrition Management Act of 2010 Dietary Education Support Act of 2009 |

|

| Thailand [88] | School-based food and nutrition standards, announced in 2010 | Ministry of Public Health–recommended nutrition labeling, on a voluntary basis since 1998 “OK” symbol for qualified food products that meet criteria on saturated fatty acids, sodium, and sugar, since 2013 |

Regulation of commercialization of “Foods for Children” by Thai FDA and Public Relations Department; limits food advertising to children on prime-time television (since 2007) | Thailand food-based dietary guidelines (1996 and 2010) “Thai People Flat Belly” project (2008–2009) Sweet Enough Network (2010) Community-based food, nutrition, and dietetic education program |

|

| United Kingdom [22, 72, 89] | Healthy Weight, Healthy Lives, a national strategy adopted in 2008 to promote a healthy diet Mandatory nutritional standards for school food Voluntary food guidance in preschools Government Buying Standards for Food |

Voluntary “traffic light” front-of-pack labeling Voluntary calorie labeling on menus for standard government purchase |

Restrictions on television advertising of unhealthy foods to children | Eatwell Plate Cooking in curriculum for students aged 11–14 y |

|

| United States [26, 27, 66, 90] | HHFKA (2010) Nutrition Standards in the National School Lunch and School Breakfast Programs (by USDA) “Smart Snacks in School” standards (first nutritional guidelines for school snacks) |

Food labeling guidelines Voluntary “Facts Up Front” system by food industry |

Self-regulatory standards for food and beverage marketing to children younger than 12, established by the Children's Advertising Review Unit and Children's Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative under the Council of Better Business Bureaus (BBB) | >40 states and some cities implemented SSB taxes |

Dietary Guidelines for Americans, published jointly every 5 y since 1980 by HHS and USDA; most recent version published in 2010. The guidelines provide authoritative advice for people ≥2 y about how good dietary habits can promote health and reduce risk of major chronic diseases. They serve as the basis for federal food and nutrition education programs. |

National Public Nutrition Education: Dietary Guidelines

Nutrition education is important to help facilitate desirable health behavioral changes and promote healthy diets, including those aimed at preventing obesity. Many countries have developed dietary guidelines during the past two decades, with the United States leading this effort. Such dietary guidelines help increase public awareness of nutritional needs and facilitate nutrition education at multiple levels and in different settings. At present, more than 60 developed and developing countries from each continent have created their own national dietary guidelines [14]. For example, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and Department of Agriculture (USDA), developed and published Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which has been revised every 5 years since 1980, with the most recent edition published in 2010. This seventh edition was published with a new emphasis on balanced energy intake and maintaining a healthy weight (i.e., for obesity prevention). These guidelines provide authoritative advice for people 2 years and older regarding how good dietary habits can promote health and reduce the risk of major chronic diseases, and they serve as the basis for federal food and nutrition education programs. Some other countries developed their guidelines based on practices in the United States. Promoting fruit and vegetable consumption has become an important role of nutrition education because of the many benefits of adequate fruit and vegetable consumption, including helping to reduce the risk of many diet-related diseases and obesity. National campaigns in countries such as Australia, New Zealand, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany aim to increase daily consumption of fruits and vegetables among their populations. A good example is the “5 A Day” program in the United States, which encourages people to consume at least five servings of fruits and vegetables daily. National and local governments of some countries provide specific funding to support such programs.

Nutrition Labeling for Food Packages

Nutrition labeling may play an important role in helping consumers choose healthy food by informing them about its nutritional content. Therefore, policy makers in many continents are pushing for legislation requiring nutrition labeling on food packages and in restaurants [15•]. Some preliminary evidence suggests that such labeling may influence food choices and improve the intake of fat, sugar, and sodium in some populations [16, 17], although the effectiveness of these policies is still inconclusive [18, 19].

Countries in Europe and Oceania have placed emphasis on nutrition labeling. Since 1989, the Nordic countries, including Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, have adopted a “keyhole” symbol to indicate healthier food choices [20]. Moreover, abundant labeling systems are available in European countries, including multiple back-of-pack and front-of-pack labels. One study compared labeling systems in four European countries (the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands) and suggested that a simple front-of-pack label might help consumers make healthier choices during the short time frame in which they typically make purchasing decisions [21].

Recently, more countries have adopted a simpler, easy-to-identify labeling system. For example, in June 2013, the Food Standards Agency in the United Kingdom launched a voluntary “traffic light,” front-of-pack labeling system [22]. In this labeling system, red, yellow, and green labels correspond to high, medium, and low percentages of fat, saturated fat, salt, sugar, and total energy in the food product. The color coding makes this nutrition information more visible. Although the new system covers only 60% of foods, it is considered a big step toward a clear and consistent way to label food [23].

Similarly, in June 2013, ministers in Australia and New Zealand approved a voluntary health star rating system to replace the Daily Intake Guide [24]. In this front-of-pack labeling system, highly nutritious foods are given higher star ratings, whereas foods with less nutritional value are given lower star ratings. The star rating scale, from one half to five stars, will be printed on the front of food packages. The nutrition label also will include information on sugar, saturated fat, sodium, and energy contained in the food [24]. Compliance with the health star rating system will be of interest to researchers, because its voluntary adoption immediately met some resistance. For example, cheese and other dairy products may contain high levels of saturated fat. Thus, the dairy industry was worried that the labeling would affect the consumer's choice. However, the ministers stand firm in promoting the health star rating system and are prepared to make it mandatory if implementation of the current policy is not successful. More scientific evidence is needed to support the adoption of a stricter policy on food labeling.

Some developing countries also are catching up with their own front-of-pack nutrition labeling systems. For example, the Thai Food and Drug Administration (Thai FDA) adopted a new nutrition labeling system in August 2011 that provides Guideline Daily Amounts for energy, sugar, fat, and sodium [25]. The labeling system is voluntary for most food groups but mandatory for snack foods, including potato chips, popcorn, rice crisps, crackers, and filling wafers. The Thai system is similar to the front-of-pack labeling systems adopted in the United Kingdom and Australia but without obvious coding, such as colors or stars. It will be worth investigating how the different coding systems used by these countries will influence consumers in their food choices.

Interestingly, the United States has not adopted a national policy or regulations regarding front-of-pack labels, which remain voluntary. Many US food industries have adopted the “Facts Up Front” system, which labels the amount of saturated fat, calories, sugar, and sodium per serving [23]. Unlike the front-of-pack labeling system in other countries, the US “Facts Up Front” system also can mention up to two beneficial nutrients, such as vitamins. However, support from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has been cautious: a simple front-of-pack label may help consumers, but it also may make consumers skip the more detailed nutrition information provided on back-of-pack labels [26, 27]. This government position reflects the lack of consistent research evidence regarding the optimal labeling system.

To promote healthy eating and help reduce diet-related diseases, China enacted national regulations for food labeling in 2008. The Chinese Food Nutrition Labeling standards regulate the labeling of food regarding its nutrients and calories [28]. Before the regulations took effect in 2013, the practice of food labeling was rare. For example, our team conducted a study during 2007 and 2008 based on the nutrition information of prepackaged foods collected in two supermarkets in Shanghai and Beijing, the two largest cities in China [29]. The results indicated that the overall labeling rate was not significantly different between the two cities in the two sampled supermarkets (Shanghai, 30.9%, vs. Beijing, 29.7%). We also noted that nutrition labeling of snacks was scarce (20.5%) in both locations, and the percentage of food items labeled was even lower (saturated fat, 8.6%; trans-fatty acids, 4.7%; fiber, 2.1%). The very low food nutrition labeling rate, even among products sold in large chain supermarkets in these two major cities of China, before the regulations took effect illustrates the need for such critical regulations to be implemented to enforce industrial compliance with accurate nutrition labeling.

Menu Nutrition Labeling for Food Provided in Restaurants

Studies indicate that consumers increase their energy intake when eating away from home compared with eating at home, usually because foods in restaurants or other food outlets contain more calories and fat and less fiber [30]. Therefore, public health advocacy groups have long argued for expansion of nutrition labeling to cover food items sold in restaurants [15•, 31]. In the United States, the Affordable Care Act of 2010 has required calorie and nutritional labeling in chain restaurants, retail food establishments, and vending machines [32]. The FDA, the government agency charged with implementing the act, has submitted the proposed regulations for public input.

Ahead of the US federal regulations, some pioneering cities and states already adopted similar regulations, such as New York City in 2008 [33•]. However, such policies have been challenged by some interest groups, and results from recent studies paint a mixed picture as to the effects of restaurant food labeling on the quality of consumers' dietary intake. One natural experiment found that the mandatory nutrition labeling in New York City's fast food restaurants have had little impact on the energy intake of children and adolescents [33•]. Another recent study, conducted in Philadelphia, reported that calorie postings often are ignored and have had little influence on fast food choices since Pennsylvania adopted similar regulations in 2010 [34]. However, a study of full-service restaurants found that although calorie labels may not have an impact on the most health-conscious consumers, they might influence the food choices of the least health-conscious consumers [15•]. With the implementation of the Affordable Care Act of 2010, researchers may be able to take advantage of such windows of opportunity to conduct more natural experiments on the effectiveness of food labeling in restaurants. To our knowledge, few other countries have implemented such national policies.

Regulation of Food Marketing

Food marketing has proven to be an effective strategy for changing consumers' food preferences, especially among children [35]. In the twenty-first century, food companies have integrated multiple media, such as television, the Internet, packaging, and popular movie characters, to penetrate the food market [36]. However, most foods advertised on television are high in fat and sugar and low in nutritional value [37, 38]. Extensive studies suggest that increased exposure to food advertising might be associated with shaping food choices, beliefs, and purchase requests [39]. Findings from many of these studies, particularly those investigating the impact of advertising on children's food choices, have resulted in strong support for government regulation of food advertisements, especially those targeting young people.

Europe leads the world in regulating television advertising of food and drink products. In the 1980s, Sweden adopted a complete ban on junk food advertising in all media aimed at children younger than 12 years [40]. Since 2005, many European countries have followed in Sweden's footsteps. In 2007, France required a health message to be included in advertisements for junk food and unhealthy drinks in all traditional and Internet media [41]. Since 2007, a series of restrictions were phased in to ban junk food advertising in UK media aimed toward children of different ages.

In December 2007, leading food and beverage companies voluntarily launched the EU (European Union) Pledge, which commits members to restricting unhealthy food advertising to children younger than 12 years on traditional and Internet media [42]. EU Pledge membership has increased to 20 companies, covering 80% of EU revenue from food and beverage advertising. In 2012, these companies jointly published a white paper on nutrition criteria and promised a further reduction in marketing toward children [43].

In 2013, the Broadcast Authority of Ireland (BAI) adopted new restrictions on high-fat, -salt, and -sugar (HFSS) food and drink advertising targeting children [44]. The only exception is advertisements for cheese.

In other parts of the world, more countries have joined the battle against childhood obesity by voluntarily or mandatorily restricting advertising of unhealthy food products. The health minister of Singapore announced in 2013 that the country would introduce stricter guidelines to regulate the advertising of sweet drinks and fast foods high in oil and salt [45]. The US-based Walt Disney Company, as the first major media corporation, announced in June 2012 that any food and drink advertising aimed at families with children that appears on any Disney-owned medium are required by 2015 to comply with Disney's nutrition guidelines, which are consistent with US federal standards [46].

Although worldwide efforts to ban the advertising of unhealthy food products are encouraging, an accurate estimation of the impact of these policies remains challenging. Furthermore, in some countries, particularly some developing nations, many food companies, especially some Western fast food restaurant chains, have been investing heavily and successfully in food advertisements, including on television. However, government regulations lag behind these marketing activities. Indeed, central and local governments in some of these nations may not have motivations for strong regulations because of concerns that such measures might hurt economic growth and reduce tax revenues.

Economic Policies Affecting Food Prices: Taxation and Subsidy

Many researchers and policy makers believe economic approaches are more effective than other strategies (e.g., public health education) in promoting health-related behaviors. The successful experience in the United States and some other countries regarding tobacco control provides some useful evidence to support this argument. A large body of literature exists on studies of economic policies regarding tobacco control and the effects of these policies. During recent years, rapidly growing research on obesity has focused on the effect of economic approaches on obesity prevention.

Economic policies may influence food prices and therefore were recommended by the WHO in 2008 to promote healthy eating in public [47]. Taxing unhealthy food and subsidizing healthy food are the two main economic policy strategies to prevent obesity. However, debate continues over whether the government should adopt these economic policies and how effective these economic policies are in reducing obesity rates. One major concern is the possible regressivity of these policies [48]. Low-income populations are more likely to purchase low-priced, unhealthy food and are less likely to consume high-priced, healthy food. Therefore, a food tax or subsidy may favor high-income populations and penalize low-income groups. However, advocates for this economic approach suggest that health gains from obesity reduction benefit low-income groups more, so food taxes or subsidies do serve a purpose [49].

Some countries have introduced tax policies targeting unhealthy food and drink products; others are in the process of adopting similar policies. Those already implemented include the US tax on sweetened drinks, Denmark's “fat tax,” Hungary's “junk food tax,” and France's “tax on sweetened drinks.” Other measures under way include plans by Romania, Finland, and the United Kingdom to initiate a fat tax and Peru's plan to tax junk food [50, 51•, 52].

In recent years, taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) in the United States have drawn much attention. Such soft drink taxes already have been applied at state and city levels in some locations, although there are no national regulations yet. More than 40 states and several major cities, such as Chicago and Washington, DC, already tax sugary drinks [53].

Taxing SSBs and unhealthy foods may have at least two positive effects. One is an increase in revenue that may be used to encourage fruit and vegetable consumption efforts and support other obesity prevention programs. The second effect is an increase in the price of SSBs and unhealthy foods, thereby reducing their consumption. Research shows that a 10% price increase might reduce consumption by 8% to 12.6%. Further estimates indicate that a 20% tax on sugary drinks in the United States would reduce the prevalence of obesity by 3.5% [54, 55]. However, studies on food taxes overall have provided mixed evidence as to their effectiveness in preventing obesity. Some researchers believed the magnitude of food tax was a critical factor for its effectiveness and therefore have proposed a comparatively larger excise tax, which would have a more effective impact on consumer behavior [56, 57].

It is believed that promoting the consumption of fruits and vegetables to replace energy-dense foods may help prevent obesity [58, 59]. However, very few countries have implemented programs to subsidize fruits and vegetables to make them more affordable to low socioeconomic groups. In the United States, First Lady Michelle Obama initiated the “Let's Move” initiative with the objective of dramatically boosting the intake of fruits and vegetables [60]. Through advocacy efforts tied to this initiative and the support of the current National School Lunch Program, 32 million students have been offered both fruits and vegetables every school day. States participating in the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program, established under the Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008, provide free fruits and vegetables to students in participating elementary schools during the school day.

School-focused Food Policies

Schools represent an appropriate setting to implement many nutrition-related programs and policies. Children and adolescents spend a significant amount of their waking time at school: the average American child spends about 1,300 h in a classroom during one 9-month school year [61]. Because obese children are more likely to remain obese in adulthood, childhood is a critical period for obesity prevention. In addition, national and regional policies viewed as beneficial to children often are more likely to get social support than policies targeting other population groups. Therefore, schools have become the front line in obesity prevention, with school wellness policies being essential to combat childhood obesity [62].

In the United States, governments at all levels have given priority to developing school policies to increase nutritional standards and to create active lifestyles for children [63-65]. The most prominent policy change is the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act (HHFKA) of 2010 [66]. The HHFKA requires the development of federal nutrition standards for all foods regularly sold in schools during the school day, including in vending machines, “a la carte” lunch lines, and school stores. Additional funding is provided under the Healthy Kid Act to schools that meet the updated nutritional standards. The USDA has taken steps to create new standards for food sold in schools, such as Nutrition Standards for School Meals and Smart Snacks in School. US schools are revising their existing policies or adopting new ones to comply with the Healthy Kids Act of 2010 and the new nutrition standards [66].

Although the expected impact of the Healthy Kids Act of 2010 on nutritional intake and obesity prevention in children and adolescents might be profound, little scientific evidence for this approach has been presented in the literature. In the absence of federal nutritional standards, alternative standards may be applied, namely the Institute of Medicine's Nutrition Standards for Foods in Schools: Leading the Way toward Healthier Youth (IOM standards). The fundamental tenets of the IOM standards are that federally reimbursable school meal programs should be the main source of nutrition in schools, that schools should limit foods that compete with healthy foods, and that if competitive foods are provided, they should consist primarily of healthy foods, such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and nonfat or low-fat milk and other dairy products [67•].

Similar nutritional standards have been adopted in French schools. GEMRCN (Groupe d'Etude des Marches de Restauration Collective et Nutrition), a national committee on catering and nutrition markets, drafted food-group frequency guidelines (FFGs) in 1999 for meals served in schools, and revised them in 2007 to restrict sugar and fat intake. Results from activity in Europe may be encouraging [68•]. Although a national survey of 707 schools suggests that only 15 to 26% of French schools had fully complied with the FFGs, a more nutritionally balanced lunch was provided after the FFGs were revised in 2007 [68•]. Therefore, it appears that adoption of a national policy is only the first step; how to implement and enforce the policy remains a challenge.

Conclusions

With increasing awareness about the importance of good nutrition and the many consequences of the growing obesity epidemic, many countries worldwide are taking active steps to support food policies aimed at preventing obesity. Developed countries, such as the United States and EU nations, have led obesity policy innovation with measures such as food labeling and school wellness programs. Some developing countries, such as China, Mexico, and Thailand, are catching up quickly. This pattern of adoption reflects the disparity between the obesity burden in developed countries and that in most developing countries. Obesity prevention through food policy provides a collaborative opportunity for policy makers in both developed and developing countries.

Although efforts of some developing countries to prevent and address the obesity epidemic are acknowledged, most developing countries are lagging behind in applying policy approach to obesity prevention. For example, to our knowledge, no developing countries in Africa have actively adopted food policies to promote healthy eating; instead of waiting for the governments to adopt the necessary policies, local citizens and nongovernmental and international organizations should play more active roles in developing or promoting obesity prevention policies at different levels, such as school district policies, company or industrial policies.

In addition, researchers, policy makers, and government officials are increasingly aware of the importance of systematic approaches to prevent obesity through food system improvements. Theoretically, from a policymaking perspective, this represents a very important way to change the obesogenic environment. However, because of the complexity of the food environment and challenges in implementing policy, little evidence is available to show the effectiveness of these food policies in reducing obesity rates. More innovative and rigorous research is needed to assess the impact of related polices and assist in their successful implementation, which may be generalized to other countries tackling obesity. International collaborations are urgently needed to address this global obesity epidemic.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported in part by research grants from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) [research grants 1R01HD064685-01A1 and U54HD070725 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD)]. The U54 project is cofunded by the NICHD and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research of the NIH. Dr. Shiyong Liu's effort was supported in part by a research grant from the Chinese National Social Science Foundation (12CGL103). The content of the paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders. We also thank Dr. HyunJung Lim for her assistance in collecting some related information.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines: Conflict of Interest Qi Zhang has received a consulting fee or honorarium from Johns Hopkins University.

Shiyong Liu, Ruicui Liu, Hong Xue, and Youfa Wang declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Qi Zhang, Email: qzhang@odu.edu, School of Community and Environmental Health, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA 23529, USA.

Shiyong Liu, Email: shiyongliu2006@gmail.com, Department of Epidemology and Environmental Health, School of Public Health and Health Professions, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, Buffalo, NY 14214-8001, USA; Research Institute of Economics and Management, Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, #55 Guanghuacun Street, Chengdu, Sichuan, China 610074.

Ruicui Liu, Email: rliux003@odu.edu, School of Community and Environmental Health, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA 23529, USA.

Hong Xue, Email: hongxue@buffalo.edu, Department of Epidemology and Environmental Health, School of Public Health and Health Professions, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, Buffalo, NY 14214-8001, USA.

Youfa Wang, Email: youfawan@buffalo.edu, Department of Epidemology and Environmental Health, School of Public Health and Health Professions, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, Buffalo, NY 14214-8001, USA.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.World Health Organization. [Accessed November 26, 2013];Obesity and overweight. Available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html.

- 2••.Wang Y, Yang W, Wilson RF, et al. Comparative Effective Review No 115. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); 2013. Childhood Obesity Prevention Programs: Comparative Effectiveness Review and Meta-Analysis. This study (an 835-page full report is available online at AHRQ's Web site) provides a systematic review and meta-analysis of 124 childhood obesity prevention studies published in high-income countries, as well as recommendations for future research directions. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3••.World Health Organization. [Accessed December 26, 2013];Controlling the global obesity epidemic. Available at http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/obesity/en/ The WHO provides recommendations, including policy options for obesity prevention and control.

- 4.Farley TA, Van Wye G. Reversing the obesity epidemic: the importance of policy and policy research. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(3S2):S93–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dodson EA, Eyler AA, Chalifour S, Wintrode CG. A review of obesity-themed policy briefs. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(3S2):S143–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker L, Burns AC, Sanchez E, editors. Institute of Medicine, National Research Council of the National Academies. Local government actions to prevent childhood obesity. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministry of Health. Food and Nutrition Guidelines for Healthy Children and Young People (aged 2-18): A background paper. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Department of Agriculture. [Accessed December 29, 2013];Smart snacks in school. Available at http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/governance/legislation/allfoods.htm.

- 9.Mair JS, Pierce MW, Teret SP. The use of zoning to restrict fast food outlets: a potential strategy to combat obesity. Center for Law and the Public's Health at Johns Hopkins and Georgetown Universities; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed November 28, 2013];Menu and vending machines labeling requirements. 2010 Available at http://www.fda.gov/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/LabelingNutrition/ucm217762.htm.

- 11.Harris JL, Graff SK. Protecting young people from junk food advertising: implications of psychological research for First Amendment law. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(2):214–22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12••.Popkin B, Monteiro C, Swinburn B. Bellagio conference on program and policy: options for preventing obesity in the low- and middle-income countries. Obes Rev. 2013;14(2):1–8. doi: 10.1111/obr.12108. This paper discusses food policies adopted by selected countries to prevent obesity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13••.Hawkes C, Jewell J, Allen K. A food policy package for healthy diets and the prevention of obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases: the NOURISHING framework. Obes Rev. 2013;14(2):159–68. doi: 10.1111/obr.12098. This paper discusses the NOURISHING framework and the food policies adopted by selected countries to prevent obesity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawkes C. Promoting healthy diets through nutrition education and change in the food environment: an international review of actions and their effectiveness. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; Rome: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15•.Ellison B, Lusk JL, Davis D. Looking at the label and beyond: the effects of calorie labels, health consciousness, and demographics on caloric intake in restaurants. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10 doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-21. This study suggests that different types of calorie labels in restaurants might have different effects on a consumer's calorie intake, depending on his or her health consciousness. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim S, Douthitt RA. The role of dietary information in women's whole milk and low-fat milk intakes. Int J Consum Stud. 2004;28(3):245–54. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harnack LJ, French SA. Effect of point-of-purchase calorie labeling on restaurant and cafeteria food choices: a review of the literature. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5(51):1–6. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mhurchu CN, Gorton D. Nutrition labels and claims in New Zealand and Australia: a review of use and understanding. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2007;31(2):105–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2007.00026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swartz JJ, Braxton D, Viera AJ. Calorie menu labeling on quick-service restaurant menus: an updated systematic review of the literature. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:135. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nordic Council of Ministers. [Accessed November 28, 2013];About the keyhole. Available at http://www.norden.org/en/nordic-council-of-ministers/council-of-ministers/council-of-miministe-for-fisheries-and-aquaculture-agriculture-food-and-forestry-mr-fjls/keyhole-nutritinu-label.

- 21.Feunekes G, Gortemaker I, Willems A, Lion R, den Kommer M. Front-of-pack nutrition labeling: testing effectiveness of different nutrition labeling formats front-of-pack in four European countries. Appetite. 2008;50(1):57–70. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Food Standards Agency. [Accessed November 28, 2013];Front-of-pack nutrition labeling. Available at http://food.gov.uk/scotland/scotnut/signposting/#.UpejmuLK-ne.

- 23.International Dairy Foods Association (IDFA) [Accessed November 28, 2013];Front-of-pack labeling around the world. Available at http://www.idfa.org/blogs/nutrition/2013/08/front-of-pack-labeling-around-the-world/

- 24.Australia Food News. [Accessed November 28, 2013];Australian ministers approve front-of-pack labeling system but dairy products approach still to be finalized. 2013 Jun 17; Available at http://www.ausfoodnews.com.au/2013/06/17/australian-ministers-approve-front-of-pack-labelling-system-but-dairy-products-approach-still-to-be-finalised.html.

- 25.Sirikeratikul S. [Accessed November 28, 2013];Thai FDA's new guideline daily amounts (GDA) labeling Global Agricultural Information Network (GAIN) Report No TH1077. Available at http://gain.fas.usda.gov/Recent%20GAIN%20Publications/Thai%20FDA%E2%80%99s%20New%20Guideline%20Daily%20Amounts%20%28GDA%29%20Labeling%20_Bangkok_Thailand_6-13-2011.pdf.

- 26.Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed November 28, 2013];Guidance for industry: letter regarding point of purchase food labeling. 2009 Available at http://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/LabelingNutrition/ucm187208.htm.

- 27.Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed November 28, 2013];Letter of enforcement discretion to GMA/FMI re “Facts Up Front”. 2011 Available at http://www.fda.gov/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeli%5B%5Dng/LabelingNutrition/ucm302720.htm.

- 28.China Product Identification, Authentication and Tracking Systems (CPIAT) [Accessed December 8, 2013];Food labeling regulation. Available at http://www.95001111.com/websiteserv/web/goverment/policy_content.jsp?id=578.

- 29.Tao Y, Li J, Lo YM, Tang Q, Wang Y. Food nutrition labeling practice in China. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(3):542–50. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010002065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin B, Guthrie J. Nutritional quality of food prepared at home and away from home, 1977-2008. [Accessed January 4, 2014];Economic Information Bulletin No (EIB-105) 2012 Available at http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/eib-economic-information-bulletin/eib105.aspx#.UoKPED_VYSQ.

- 31.Burton S, Creyer EH, Kees J, Huggins K. Attacking the obesity epidemic: the potential health benefits of providing nutrition information in restaurants. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(9):1669–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed November 28, 2013];Overview of FDA proposed labeling requirements for restaurants, similar retail food establishments and vending machines. 2013 Available at http://www.fda.gov/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/LabelingNutrition/ucm248732.htm.

- 33•.Elbel B, Gyamfi J, Kersh R. Child and adolescent fast-food choice and the influence of calorie labeling: a natural experiment. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35(4):493–500. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.4. This natural experiment found that mandatory calorie labeling did not influence fast food choices of children and adolescents in low-income communities. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elbel B. [Accessed November 28, 2013];Mandatory calorie postings at fast-food chains often ignored or unseen, does not influence food choice. 2013 Available at http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2013-11/nlmc-mcp111213.php.

- 35.Utter J, Scragg R, Schaaf D. Associations between television viewing and consumption of commonly advertised foods among New Zealand children and young adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(5):606–12. doi: 10.1079/phn2005899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Federal Trade Commission. [Accessed November 28, 2013];A review of food marketing to children and adolescents: follow up report. 2012 Available at http://ftc.gov/os/2012/12/121221foodmarketingreport.pdf.

- 37.Harrison K, Marske AL. Nutritional content of foods advertised during the television programs children watch most. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(9):1568–74. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.048058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chapman K, Nicholas P, Supramaniam R. How much food advertising is there on Australian television? Health Promot Int. 2006;21(3):172–80. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dal021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scully M, Dixon H, Wakefield M. Association between commercial television exposure and fast-food consumption among adults. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(1):105–10. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oommen VG, Anderson PJ. Policies on restriction of food advertising during children's television viewing times: an international perspective. Proceedings Australian College of Health Service Executives 2008 Conference, Going for Gold in Health—Motivation, Effort, Performance; Gold Coast, Australia. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 41.European Public Health Alliance. [Accessed November 28, 2013];Junk food: evolution of the legislation in European countries. 2007 Available at http://www.epha.org/spip.php?article2554.

- 42.EU Pledge. [Accessed November 28, 2013];About the EU pledge. 2013 Available at http://www.eu-pledge.eu/content/about-eu-pledge.

- 43.EU Pledge. [Accessed November 28, 2013];Nutrition criteria: White paper. 2012 Available at http://www.eu-pledge.eu/sites/eu-pledge.eu/files/releases/EU_Pledge_Nutrition_White_Paper_Nov_2012.pdf.

- 44.Broadcast Authority of Ireland. [Accessed November 28, 2013];BAI signals new rules to govern advertising of food and drink in children's advertising. 2013 Available at http://www.bai.ie/?p=2792.

- 45.Strait Times. [Accessed November 28, 2013];Ban on ads that drive kids to unhealthy food. 2012 Oct 28; Available at http://www.facebook.com/notes/reachsingapore/ban-on-ads-that-drive-kids-to-unhealthy-food/10151132709078795.

- 46.Walt Disney. [Accessed November 28, 2013];The Walt Disney Company sets new standards for food advertising to kids. 2012 Jun 4; Available at http://thewaltdisneycompany.com/disney-news/press-releases/2012/06/walt-disney-company-sets-new-standards-food-advertising-kids.

- 47.World Health Organization (WHO) 2008-2013 action plan for the global strategy for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friedman RR, Brownell KD. Sugar-sweetened beverage taxes: an updated policy brief. Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity; New Haven, CT: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 49.National Heart Forum. [Accessed November 28, 2013];What is the role of health-related food duties? 2012 Available at http://www.iaso.org/site_media/uploads/UKHF_duties.pdf.

- 50.Holt E. Romania mulls over fast food tax. Lancet. 2010;375:1070. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60462-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51•.Mytton OT, Clarke D, Rayner M. Taxing unhealthy food and drinks to improve health. BMJ. 2012;344:e2931. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2931. This paper systematically reviews existing evidence on the effectiveness of health-related food taxes. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Villanueva T. European nations launch tax attack on unhealthy foods. CMAJ. 2011;183(17):E1229–30. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-4031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Center for Science in the Public Interest. [Accessed November 28, 2013];Existing soft drink taxes. 2011 Available at http://cspinet.org/liquidcandy/existingtaxes.html.

- 54.Lin H, Smith TA, Lee JY, Hall KD. Measuring weight outcomes for obesity intervention strategies: the case of a sugar-sweetened beverage tax. Econ Hum Biol. 2011;9(4):329–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hall KD, Sacks G, Chandramohan D, et al. Quantification of the effect of energy imbalance on bodyweight. Lancet. 2011;378:826–37. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60812-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brownell KD, Frieden TR. Ounces of prevention—the public policy case for taxes on sugared beverages. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(18):1805–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0902392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brownell KD, Farley T, Willett WC, et al. The public health and economic benefits of taxing sugar-sweetened beverages. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1599–605. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0905723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rolls BJ, Ello-Martin JA, Tohill BC. What can intervention studies tell us about the relationship between fruit and vegetable consumption and weight management? Nutr Rev. 2004;62(1):1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fisher JO, Liu Y, Birch LL, Rolls BJ. Effects of portion size and energy density on young children's intake at a meal. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(1):174–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.1.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Let's Move. [Accessed December 29, 2013];September is fruits & veggies—more matters month. Available at http://www.letsmove.gov/blog/2013/09/16/september-fruits-veggies-%E2%80%94-more-matters-month.

- 61.Juster FT, Ono H, Stafford FP. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2004. [Accessed September 22, 2013]. Changing time of American youth: 1981-2003. Available at http://www.ns.umich.edu/Releases/2004/Nov04/teen_time_report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chriqui JF, Schneider L, Ide K, Pugach O, Chaloupka FJ. Local wellness policies: Assessing school district strategies for improving children's health — school years 2006-07 and 2007-08. Bridging the Gap Program, Health Policy Center, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Briefel RR, Crepinsek MK, Cabili C, Wilson A, Gleason PM. School food environments and practices affect dietary behaviors of US public school children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(Suppl 2):S91–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fox MK, Dodd AH, Wilson A, Gleason PM. Association between school food environment and practices and body mass index of US public school children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(Suppl 2):S108–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fox MK, Gordon A, Nogales R, Wilson A. Availability and consumption of competitive foods in US public schools. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(Suppl 2):S57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.US Department of Agriculture. [Accessed November 28, 2013];Healthy Hunger-free Kids Act of 2010. Available at http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/governance/legislation/PL111-296_Summary.pdf.

- 67•.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Competitive foods and beverages in US schools: A state policy analysis. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. This study pointed out that although many states had set standards for competitive foods sold in schools, few of them had met half of the IOM standard of competitive foods. [Google Scholar]

- 68•.Bertin M, Lafay L, Calamassi-Tran G, Volatier JL, Dubuisson C. School meals in French secondary state schools: do national recommendations lead to healthier nutrition on offer? Br J Nutr. 2012;107(3):416–27. doi: 10.1017/S000711451100300X. This study demonstrates the effectiveness of school dietary guidelines in offering nutrition-balanced school meals. It also points out that school dietary guidelines themselves cannot lead to healthier school meals. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Swinburn B, Wood A. Progress on obesity prevention over 20 years in Australia and New Zealand. Obesity Rev. 2013;14(Suppl 2):60–8. doi: 10.1111/obr.12103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Khan SH, Talukder SH. Nutrition transition in Bangladesh: is the country ready for this double burden? Obesity Rev. 2013;14(Suppl 2):126–33. doi: 10.1111/obr.12100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jaime PC, da Silva ACF, Gentil PC, Claro RM, Monteiro CA. Brazilian obesity prevention and control initiatives. Obes Rev. 2013;14(Suppl 2):88–95. doi: 10.1111/obr.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hawkes C. Regulating food marketing to young people worldwide: trends and policy drivers. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(11):1962–73. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.101162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Health Canada. [Accessed January 2, 2014];Amendments to the Food and Drugs Act (Bill C-38) 2012 Available at http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/legislation/acts-lois/c-38-eng.php.

- 74.Canadian Food Inspection Agency. [Accessed January 2, 2014];Guide to food labeling and advertising. 2013 Available at http://www.inspection.gc.ca/food/labelling/guide-to-food-labelling-and-advertising/eng/1300118951990/1300118996556.

- 75.Corvalán C, Reyes M, Garmendia ML, Uauy R. Structural responses to the obesity and non-communicable diseases epidemic: the Chilean law of food labeling and advertising. Obes Rev. 2013;14(Suppl 2):79–87. doi: 10.1111/obr.12099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang H, Zhai F. Programme and policy options for preventing obesity in China. Obes Rev. 2013;14(Suppl 2):134–40. doi: 10.1111/obr.12106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Madden D. The poverty effects of a ‘fat-tax’ in Ireland. Health Econ. 2013 doi: 10.1002/hec.3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Khandelwal S, Reddy KS. Eliciting a policy response for the rising epidemic of overweight-obesity in India. Obesity Rev. 2013;14(Suppl 2):114–25. doi: 10.1111/obr.12097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Barquera S, Campos I, Rivera JA. Mexico attempts to tackle obesity: the process, results, push backs and future challenges. Obes Rev. 2013;14(Suppl 2):69–78. doi: 10.1111/obr.12096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hawkes C, Lobstein T. Regulating the commercial promotion of food to children: a survey of actions worldwide. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6(2):83–94. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2010.486836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.van Ansem WJ, Schrijvers CT, Rodenburg G, Schuit AJ, van de Mheen D. School food policy at Dutch primary schools: room for improvement? Cross-sectional findings from the INPACT study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:339. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Snowdon W, Thow AM. Trade policy and obesity prevention: challenges and innovation in the Pacific Islands. Obes Rev. 2013;14(Suppl 2):150–8. doi: 10.1111/obr.12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Foo LL, Vijaya K, Sloan RA, Ling A. Obesity prevention and management: Singapore's experience. Obes Rev. 2013;14(Suppl 2):106–13. doi: 10.1111/obr.12092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lambert EV, Kolbe-Alexander TL. Innovative strategies targeting obesity and non-communicable diseases in South Africa: what can we learn from the private healthcare sector? Obes Rev. 2013;14(Suppl 2):141–9. doi: 10.1111/obr.12094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kwak NS, Kim E, Kim HR. Current status and improvements of obesity related legislation. Koren J Nutr. 2010;43(4):413–23. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Korea Mnistry of Food and Drug Safety. [Accessed January 2, 2014];Food labeling standards. 2011 Available at http://www.mfds.go.kr/eng/index.do?nMenuCode=27.

- 87.International Confederation of Dietetic Associations. [Accessed January 2, 2014];Clinical dietary certificate as national qualification in Korea. 2010 Available at http://www.internationaldietetics.org/Newsletter/Vol20Issue2/NDA-Report-Korea.aspx.

- 88.Chavasit V, Kasemsup V, Tontisirin K. Thailand conquered undernutrition very successfully but has not slowed obesity. Obes Rev. 2013;14(Suppl 2):96–105. doi: 10.1111/obr.12091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jebb SA, Aveyard PN, Hawkes C. The evolution of policy and actions to tackle obesity in England. Obes Rev. 2013;14(Suppl 2):42–59. doi: 10.1111/obr.12093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rudd Center. [Accessed January 2, 2014];Industry Self-Regulation. 2013 Available at http://www.yaleruddcenter.org/what_we_do.aspx?id=25.