Abstract

Animals bear communities of gut microorganisms with substantial effects on animal nutrition, but the host genetic basis of these effects is unknown. Here, we use Drosophila to demonstrate substantial among-genotype variation in the effects of eliminating the gut microbiota on five host nutritional indices (weight, and protein, lipid, glucose and glycogen contents); this includes variation in both the magnitude and direction of microbiota-dependent effects. Genome-wide associations to identify the genetic basis of the microbiota-dependent variation reveal polymorphisms in largely non-overlapping sets of genes associated with variation in the nutritional traits, including strong representation of conserved genes functioning in signaling. Key genes identified by the GWA study are validated by loss-of-function mutations that altered microbiota-dependent nutritional effects. We conclude that the microbiota interacts with the animal at multiple points in the signaling and regulatory networks that determine animal nutrition. These interactions with the microbiota are likely conserved across animals, including humans.

Introduction

Animal phenotypes are strongly influenced by microorganisms that colonize their surfaces (e.g. skin, gut, reproductive tract) and sometimes internal organs1. Some microbial effects can be attributed to specific microbial functions, e.g. synthesis of specific nutrients or protective toxins2. Other microbial effects on the host, including promotion of intestinal homeostasis, immunity and metabolic function, involve complex networks of interactions between the animal host and microbiota3–7. These complex interactions have been interpreted as evidence that animal regulatory networks are structured to function in the context of the resident microbiota1,2, with the implication that host health and vigor can be prejudiced by mismatch between host function and the composition or activities of the microbiota, a condition known as dysbiosis8.

The purpose of this study was to quantify how the effect of the microbiota on host phenotype varies with host genotype, and to elucidate the genetic bases of these microbiota-dependent host traits. This issue has not been addressed directly for any system, even though it has important implications for our understanding of the genetic basis of human diseases linked to microbiota9, and can potentially make significant contributions to the development of personalized microbial therapies10–12. More generally, understanding how the microbiota-dependent phenotype maps onto the host genotype will enrich our understanding of the evolution and function of interactions between animals and their resident microbiota.

Our research was conducted on the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster and its gut microbiota, which is ideally suited for the study of microbiota-dependent effects for three reasons. First, experimental analysis is facilitated by robust methods to eliminate the gut microbiota by egg dechorionation, yielding axenic flies13,14. This treatment does not affect the complement of the intracellular bacterium Wolbachia, which is present in many Drosophila lines and is vertically transmitted via the egg cytoplasm. Second, axenic individuals of Drosophila lines studied to date commonly display readily-quantified nutritional traits, including elevated levels of indices of triglyceride, glycogen or free glucose15,16, and these changes have been linked to altered function of the nutrient-sensing IIS and TOR signaling pathways that couple organismal growth to nutrient supply17,18. Finally, the superb genetic resources for Drosophila can be harnessed to interrogate the genetic architecture of microbiota-dependent effects. In particular, The Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel (DGRP) of inbred isofemale lines with sequenced genomes enable genotype-phenotype mapping by genome-wide association (GWA)19–21; and candidate genes identified from GWA can then be validated experimentally by mutant analysis. The design of this study was also informed by research on the composition of the gut microbiota, which is dominated by bacteria of the Acetobacteraceae (α-proteobacteria) and Lactobacillales (Firmicutes)22. The impact of the gut microbiota on Drosophila nutritional indices depends on the composition of the microbiota23, which can vary, apparently stochastically, among Drosophila stocks maintained under uniform conditions24,25. To standardize the microbiota in the test DGRP lines, this study was conducted on flies generated from dechorionated eggs and exposed to isolates of 5 bacterial species that were isolated from Drosophila guts, are found ubiquitously in association with laboratory-cultured and wild-caught Drosophila and, in combination, have been shown to restore the nutritional phenotype of Drosophila bearing its unmanipulated microbiota23,24,25.

This study focused on the nutritional effects of the Drosophila microbiota. Using the DGRP, we demonstrated substantial among-line variation in nutritional response to elimination of the microbiota; and identified host genetic variants (single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs) associated with the microbiota-dependent nutritional traits. Many of the genes identified have fundamental roles in cell signaling and control of gene expression that are conserved in many animals, including humans. Our results show the central role of host genotype in shaping the impact of microbiota on animal nutrition.

Results

Genetic variation in microbiota-dependent nutritional traits

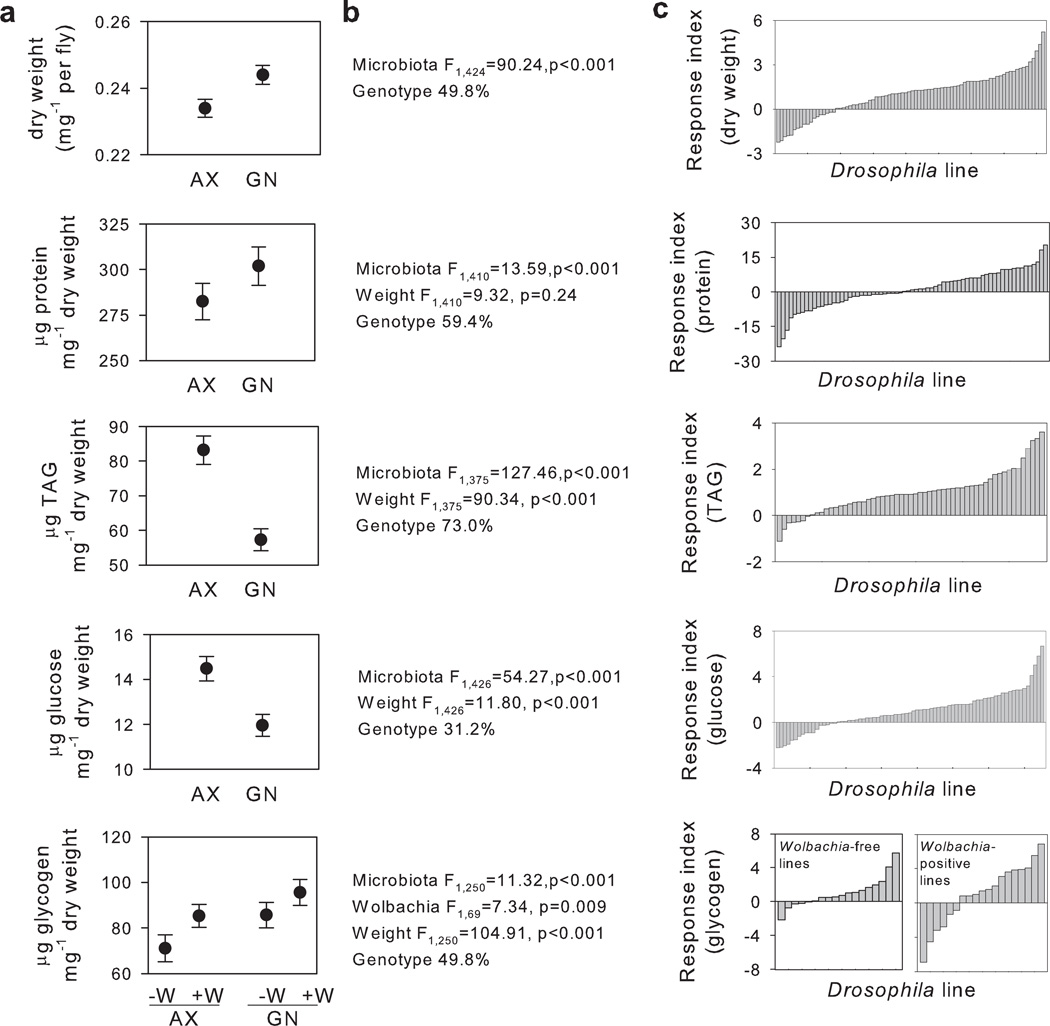

Gnotobiotic Drosophila associated with a defined five-species microbiota and axenic (microbe-free) Drosophila differed significantly in all of the five nutritional traits tested (Figure 1). The global mean values of dry weight per fly were depressed in axenic flies and, after controlling for weight, axenic flies also had reduced glycogen and protein contents but elevated glucose and triglyceride (TAG) contents (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1). Nevertheless, the among-line variation in the response to elimination of the microbiota was appreciable for all traits, and genotype accounted for 31–73% of the total variance (Fig. 1b), and within-line variation was low (Supplementary Fig. 1). For every trait, the variation included lines that differed in response direction, i.e. every trait was elevated in axenic flies of some lines, but decreased in other lines (Fig. 1c). Among the lines tested, 51% bore the intracellular bacterium Wolbachia, which was not eliminated by the egg dechorionation procedure used to generate axenic flies. The Wolbachia-positive lines had significantly elevated glycogen content relative to Wolbachia-free lines in both axenic and gnotobiotic flies (Fig. 1), perhaps due to sensitization to insulin signaling26.

Figure 1.

Effects of elimination of the microbiota on Drosophila nutritional traits vary by host genotype. Data were collected from a total of 108 DGRP lines, in pooled samples of 5 males per line (up to 3 replicate samples per line). (a) Population means and standard error for axenic (AX) and gnotobiotic (GN) flies with standard errors calculated from means per individual DGRP lines. Data are plotted by Wolbachia status (−W, Wolbachia-free, +W, Wolbachia-positive) where effects of Wolbachia are significant, and nutritional indices are normalized to line mean dry weight to avoid confounding effects of variation in weight. (b) ANOVA models of each trait simplified from a full model of microbiota + Wolbachia for weight, and microbiota + Wolbachia + weight for other indices, with genotype nested in experimental block as random effects for all traits (full statistical output in Supplementary Table 1). Percentage variance explained by genotype was calculated as the square of the standard deviation around the genotype coefficient. (c). Response indices of lines to elimination of the microbiota.

For each trait, the mean values were significantly correlated across the axenic and gnotobiotic flies (weight r=0.8; protein/weight r=0.61; glucose/weight r=0.46; glycogen/weight r=0.53; TAG/weight r=0.77; all p<0.001), reinforcing the evidence above for a genetic component to these traits. We also tested for correlations among the various phenotypic traits (Supplementary Table 2). No traits were significantly correlated in axenic flies, irrespective of Wolbachia status; this result indicates that generalized among-genotype variation in sensitivity to elimination of the microbiota is not a major driver of the microbiota-dependent effects. Among gnotobiotic flies, Wolbachia status determined which traits were correlated: TAG was positively correlated with glucose and glycogen contents in Wolbachia-positive gnotobiotic flies, but this effect was absent in Wolbachia-free flies (Supplementary Table 2). The data did not reveal specific lines whose nutritional status was globally hypersensitive to elimination of the microbiota, evidenced by the absence of positive correlations amongst response indices for each trait (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Collectively, these results demonstrate that Drosophila nutrition has a strong genetic component, that trait values are influenced by the microbiota, and that there is genetic variation in the microbiota-dependence of Drosophila nutritional traits. Furthermore, the variation in the response of the various traits to elimination of the microbiota does not appear to be coupled.

Genotype-phenotype associations

To determine the association between SNPs, microbiota, and the nutritional traits, the interactive effect of microbiota and SNP was tested for biallelic SNP markers in the Drosophila genome. We determined SNP significance by p-value rank, because of p-value inflation and the ineligibility of standard post-hoc corrections for GWA38. The top ranking 0.01% of SNPs for each trait (Supplementary Fig. 3) comprised 184–226 SNPs, including SNPs associated with 77–144 genes, with a total of 436 genes mapped across the full dataset (Supplementary Table 3). Linkage disequilibrium (LD) between these SNPs was generally low, apart from an island of linked SNPs on chromosome 2L associated with variation in glycogen stores (Supplementary Fig. 4). The mapped SNPs were found more commonly in genic regions than expected, based on genome background (number of SNPs <5000 bp from known genes: mapped SNPs = 91%, genome background = 57%, proportions test p < 0.0001). Significant GO assignments (FDR≤0.05) and the loci responsible for assignments are presented in Supplementary Table 4.

To gain an overview of the biological functions potentially determining the host phenotypic responses to the microbiota, we interrogated known functions of genes associated with the 20 most significant SNPs found by each GWA (Supplementary Table 3). Associations between microbiota-dependent variation in dry weight and SNPs included a SNP in the transcription factor Lim3, a SNP in dpr10 (a predicted chemosensor enriched in expression in the brain), and two SNPs in the translational modifier boule (bol). Microbiota-dependent variation in protein content was associated with multiple SNPs in varicose, which has known roles in trachea development27; and variation in both dry weight and protein are associated with SNPs in trol, a modulator of various signaling pathways, including FGF, hedgehog and Wnt28,29. Microbiota-dependent variation in TAG was associated with SNPs in genes coding a number of central regulatory elements including the kinase happyhour (Hppy: negative regulator of EGFR signaling and a kinase of JNK and IIS/TOR signalling), the tyrosine protein phosphatase Ptp99A, Highwire (hiw, a member of the BMP signaling pathway), and rugose (rg), homolog of the mammalian Neurobeachin, which regulates neurotransmitter receptor trafficking implicated in associative learning30,31, as well as the transcription factors klumpfuss (klu) and scribbler (sbb). The candidate functional significance of IIS/TOR signaling indicated by the SNP in Hppy is strengthened by lower-ranked associations of TAG with SNPs in two genes S6K (ranked #114) and melted (#136) coding canonical IIS/TOR proteins downstream of Hppy, as well as four further Hppy SNPs (#122, 124, 138, 139). The most significant SNP associated with microbiota-dependent variation in glucose content was in Slit (sli), the ligand of roundabout signaling that controls intestinal stem cell fate32. Other SNPs in this association included dunce (dnc), a cAMP-phosphodiesterase which is involved in regulation of multiple behaviors33, and the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor nAChRα2. Glycogen showed particularly strong associations with the JAK-STAT activated transcription factor chinmo34, the EGFR-responsive transcription factor seven up (svp), as well as the morphogen nuf; numb (an antagonist of Notch signaling) and CG5867, which contains a protein domain for juvenile hormone binding.

In total, SNPs linked to just 26 genes (6% of the 436 genes) were associated with more than one trait (Supplementary Table 5), and no gene mapped to more than two traits. The low incidence of genes associated with multiple traits is consistent with the responses of traits to removal of the microbiota (Supplementary Table 2).

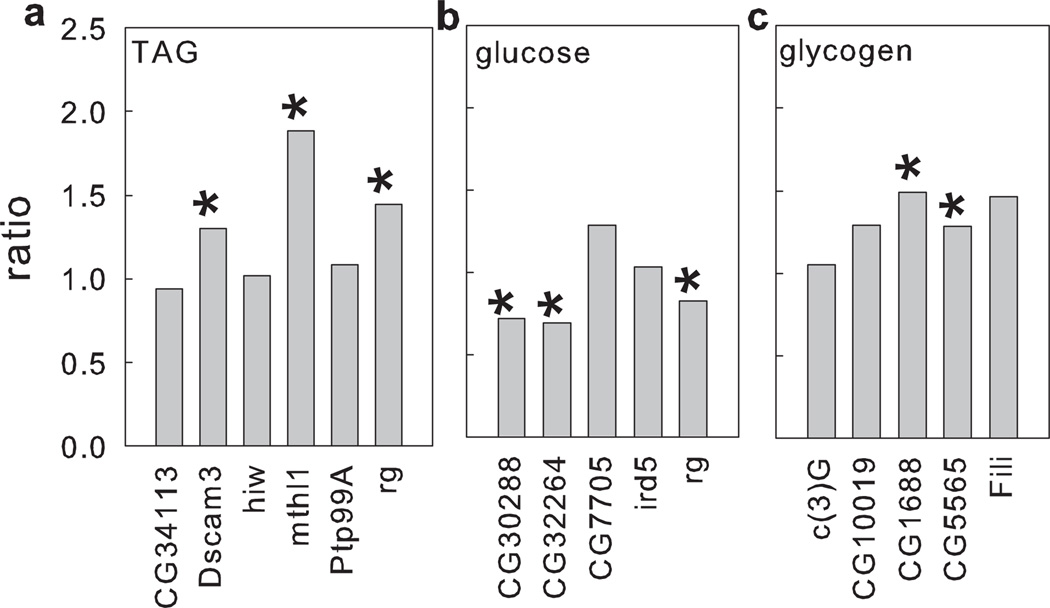

Functional Validation of GWA

The validation of associations between SNPs and microbiota-dependent phenotypic traits focused on genes linked to mapped SNPs. We reasoned that if a SNP correctly infers the role of a gene, then the trait difference between corresponding flies with a null mutation and wild-type flies could be obtained in either axenic flies or gnotobiotic flies, but not in both treatments. Therefore, our definition of a validated effect of mutation is a statistically significant difference between the mutant and background in one but not both of the axenic and gnotobiotic flies, with a p-value ≤0.025 (correcting for two comparisons) by a mixed-effects model. By this criterion, 9 (56%) of 16 predicted microbiota-dependent effects of the tested genes on TAG, glucose and glycogen were validated (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Some off-target effects were anticipated because mutations are predicted to cause greater disruption of genetic networks than natural polymorphisms. In total, four (27%) of 15 tests for off-target effects of genes validated for nutritional traits predicted in the GWAS yielded significant effects (Table 1, Supplementary Table 6 and Supplementary Fig. 5). There were two classes of response to microbiota in validated mutants: the microbiota either suppressed the effects of some mutations, such that the ratio of response (Fig. 2) was significantly greater than unity (e.g. DSCAM3, mthl1 and rg for TAG); or the microbiota promoted the effects of mutations on the host phenotypic trait (e.g. glucose levels for CG32264, CG30288, and rg).

Table 1.

Microbiota-responsive traits among GWA-validated mutants.

| Gene | Wolb.b | SNP Rank in GWA |

Validated effects of microbiotac |

Number of validated effects/total tested | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAG | Glucose | Glycogen | Validatedd | Validated plus off-target effecte |

|||

| TAG | 2/5 | 1/4 | |||||

| Dscam3 | N | 13 | + | ||||

| mthl1a | N | 17 | + | * | |||

| Glucose | 2/4 | 1/4 | |||||

| CG32264 | N | 3 | + | ||||

| CG30288a | Y | 45 | + | * | |||

| Glycogen | 3/5 | 1/6 | |||||

| CG1688 | Y | 1 | + | ||||

| CG5565 | Y | 13 | * | + | |||

| Fili | Y | 15 | + | ||||

| TAG and Glucose | |||||||

| Rg | Y | 5,6,7 TAG | + | + | * | 2/2 | 1/1 |

| 86 glucose | |||||||

nonsynonymous SNP in coding region in GWA.

Incidence of Wolbachia, determined by diagnostic PCR of adult flies (Y, present; N, absent).

+, predicted effect; *, unpredicted effect.

Number validated genes for nutritional trait/total number of genes tested for nutritional trait

Number of off-target effects of genes that had GWA-predicted effects/total possible number of off-target effects of genes that had GWA-predicted effects.

Datasets showing predicted and non-predicted significant effects of mutations on microbiota-dependent nutritional traits are displayed in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Figure 2.

GWAS validation. Effect of microbiota on nutritional indices in fly lines with mutations in GWA-predicted genes for each of (a) TAG, (b) glucose, and (c) glycogen. Ratio refers to the ratio of the gnotobiotic:axenic index value in the mutant relative to the ratio of the gnotobiotic:axenic index value in the background Drosophila stock. Statistical differences (mixed-effects linear models) between the mutant and its background were calculated under each microbiota treatment (axenic and gnotobiotic), and an effect was assigned where mutant and background stocks were significantly different under only one microbiota treatment (indicated by *).

Taken together, these results provide experimental verification that GWAS is an effective route to identify genes with significant microbiota-dependent effects on nutritional traits of Drosophila.

Discussion

This study has demonstrated substantial effects of host genetics on the nutritional response of Drosophila to elimination of the gut microbiota. For every index tested, both the magnitude and direction of the response varied among the Drosophila lines. For example, previous reports of elevated TAG and glucose in axenic flies of the Drosophila line Canton S background15,16,23 are consistent with results obtained for most of the DGRP lines studied here, but a minority displayed the reverse response; and both positive and negative responses to elimination of the microbiota were well-represented among the lines for protein content and glycogen content. These results are complemented by the mutant analysis; and suggest that interactions between the microbiota and host processes that regulate nutrient allocation are not tightly constrained, and are responsive to genetic variation in the host. Host genotypic effects on microbiota-dependent nutritional traits may be general among animals, including the human and mouse, for which some traits of the microbiota are already known to vary with host genotype35–37.

A key result of this study is that the effects of eliminating the microbiota on different nutritional indices are not correlated. This suggests that, although nutrient allocation patterns are coordinately regulated by integrated signaling circuits, the genetic variation that determines the responsiveness of these networks to the microbiota may have effects specific to individual nutritional indices. Fully consistent with this finding, GWAs revealed that variation in each nutritional trait mapped predominantly to distinct sets of loci and functional processes. Although an experimental design with greater statistical power may have yielded evidence for more pleiotropic genes, these results suggest that many of the genes with microbiota-dependent effects on nutrition have low pleiotropy and raise the possibility that many of the genes which influence multiple nutritional indices may generally be microbiota-unresponsive.

The functional validations using mutant Drosophila provided a critical test for the reliability of the GWAs in predicting genes with microbiota-dependent effects on nutritional traits. These tests confirmed that host nutrition is determined by an interaction of the microbiota and host genotype. The nature of this interaction appears to depend on the gene in question, since the microbiota suppressed nutritional effects of some mutations, but were required to detect nutritional effects of other mutations. The mutants commonly had the effects predicted by GWAs. However, our ability to make statements about trait-specific effects of genes mapped by GWA is tempered by nonspecific effects of mutants of some genes on certain phenotypic traits. Possible technical causes of discrepancies between mutants and GWAs are false negatives in the GWAs, and artefacts of mutants' genetic backgrounds. Possible biological causes include off-target effects of mutants, owing to potentially greater disruption of genetic networks by transgenic mutation than by natural polymorphism; or the related issue of SNPs having tissue-specific effects on gene function that are not mirrored by mutations. We therefore interpret the results of our functional validations as consistent with the absence of a signal of pleiotropy from GWA mappings, with the caveat that 27% of possible effects were not predicted by GWAs.

Successful validation of mutants is particularly relevant in the context of two limitations of the genome-wide analyses: poor definition of the critical probability for GWA studies, due to the ineligibility of standard corrections for multiple statistical comparisons38,39; and inflated p-values identified in QQ plots (Supplementary Fig. 6), potentially indicative of mis-specification in GWA models (Supplementary Note 1). We found that the microbiota-dependent effects for each trait were more frequently abrogated in Drosophila bearing mutations in genes mapped by specific GWAs than in collective pools for the individual genes of interest, confirming that mapped genes are microbiota-responsive (Fig. 2 and Table 1). We conclude that the validation studies of mutants support the genome-wide mappings as a strategy to generate hypotheses about the genetics underlying variation in impacts of the microbiota on nutrition.

The GWAs identified genes functioning in IIS/TOR signaling, a network identified previously to interact with the gut microbiota17,18. IIS/TOR signaling is a nexus of nutrition and growth (e.g.40,41), but with extensive cross-talk with other pathways involved in regulation of growth. The identification of genes contributing to multiple signaling pathways other than IIS/TOR indicates that the effects of the microbiota on host phenotype cannot be described exclusively in terms of any single defining pathway: Instead, our results are congruent with the view that the microbiota interact at multiple points in the signaling and regulatory networks that define animal function. These data provide evidence for the argument made previously1,2, but largely without supporting data, that many animal-microbiota interactions are likely conserved across the animal kingdom, including in humans, because the associations with resident microbiota are ubiquitous among animals and important for animal health and vigor.

Immediately relevant to these considerations are genes with no known function, accounting for 43% of mapped genes. The nutritional functions of many of these genes may be microbiota-dependent, and may have gone undetected by traditional genetic screens, which do not control for microbiota effects. Experimental analyses that compare axenic hosts with hosts that are colonized with different microbial partners could promote understanding of these currently un-annotated genes. Also of interest is the absence of canonical immunity genes or immunity-related GO terms significantly associated with any microbiota-dependent trait. Various immune effectors have been implicated in the regulation of interactions with the microbiota in Drosophila42,43 and other animals44–47, raising the possibility that genetic variation in immunity may shape the microbiota in a manner that affects traits other than the nutrition-related traits studied here; or this variation is not exposed in associations with a specified microbiota. Our GWA analyses necessarily did not account for variation in the hosts' ability to associate with the microbiota. The replication of host genotypes and properties of the microbiota (e.g. total abundance, relative abundance) required to distinguish the effects of these two factors on host phenotype would require thousands of Drosophila lines. A key objective of future studies should be to map genetic variation in the predisposition of Drosophila for certain microbial communities, and to characterize any correspondence between such variation and nutrition.

The GWA mappings elucidated in this study offer a rich inventory of genes with candidate roles in microbiota-dependent traits. Although our experimental design precludes detailed analysis of the evolutionary forces shaping this variation because the inbred DGRP lines bear unnaturally segregated allelic combinations that expose variants which may not be subject to selection under field conditions, the host genes identified likely include targets of microbiota-dependent selection. Future research to identify the mode of action and evolutionary significance of genes with microbiota-dependent function will need to account for the complexity of the interactions: that the impacts of the microbiota on host traits are strongly influenced by host genotype and involve variation in multiple genes with largely independent effects on different phenotypic traits.

Methods

The flies

Drosophila from the Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel19 and transposon (P-element insertion) mutant flies obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Resource Center, IN, USA (Supplementary Table 7) were cultured at 25°C on a 12h:12h light-dark cycle on yeast-glucose medium (1 l water, 100 g brewer's yeast [MP Biomedicals 903312], 100 g glucose [Sigma 158968], 1.2% agar [Apex 66–103], 0.84% propionic acid, 0.08% phosphoric acid). Axenic and gnotobiotic flies were generated by allowing flies from stock cultures to oviposit overnight on grape juice agar (1 l water, 100 g yeast, 100 g glucose, 113 ml Welch's concentrated grape juice). The eggs were picked from the agar with a paint brush, and dechorionated by five minutes washing in 0.6% hypochlorite (10% Clorox brand bleach) to remove all microorganisms associated with the egg surface (but not the cytoplasmic Wolbachia), followed by three rinses with sterile water. To produce axenic flies, the eggs were added to 7.5 ml sterile yeast-glucose food medium in 50 ml Falcon tubes (Fisher Scientific) using aseptic technique in a laminar flow cabinet. To produce gnotobiotic flies, 50 µl bacterial suspension at 108 cells ml−1 was added to tubes containing the axenic eggs. The bacterial suspension comprised equal proportions of Acetobacter pomorum DmelCS_004, A. tropicalis DmelCS_006, Lactobacillus brevis DmelCS_003, L. fructivorans DmelCS_002 and L. plantarum DmelCS_001. Bacteria were streaked from clonal glycerol stocks kept at −80°C onto MRS 1.2% agar and grown at 30°C, either aerobically (Acetobacter spp.) or under CO2 (Lactobacillus spp.). Individual colonies were then inoculated into 10 ml MRS broth. Acetobacter spp. were grown overnight at 30°C with shaking, L. brevis and L. plantarum were grown overnight at 30°C without shaking, L. fructivorans was grown for 7 days without shaking. For each Drosophila line, flies were reared from eggs in up to six replicate vials per treatment, and phenotyped for GWA when 6–8 days post-eclosion. The microbiological status of axenic and gnotobiotic flies was checked by plating a sample of fly homogenate (generated as below) onto 1.2% MRS agar and incubating for 48 h at 30°C under aerobic conditions for Acetobacter and under CO2 for Lactobacillus. Because low bacterial counts can be generated by contamination during fly sorting, our criteria for discarding axenic fly samples was >600 CFUs per fly, equivalent to <1% of CFUs per gnotobiotic fly.

For axenic and gnotobiotic flies of each line, the day on which ≥50% flies eclosed was recorded, and the flies were harvested 5–7 days later (both treatments in any line were assayed on the same day). At 4–7 hours after the beginning of the daily light cycle, the flies in each vial were lightly anesthetized with CO2 and males were selected for analysis.

Dry weight quantification and nutritional assays

For GWA, three pools of 5 CO2-anaethetized flies per treatment per line were flash-frozen on dry ice, desiccated over 7 days at 55°C, then weighed on a Mettler Toledo (MX5) microbalance to the nearest µg. For each microbiota treatment per line, a second set of three pools of 5 CO2-anaethetized flies were homogenized in 125 µl TE extraction buffer (35 mM Tris, 25 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5, 0.1% (v/v) Triton-X-100) with ceramic beads (MP Biomedicals 6540-434) for 30 seconds in a tissue homogenizer (MP Biomedicals FastPrep-24). 20 µl homogenate was immediately flash-frozen for subsequent protein quantification; the remainder was heat-treated at 72°C for 15 minutes, then flash-frozen. Samples were subsequently thawed and assayed for soluble protein, glucose, glycogen and triglyceride (TAG) content, according to established protocols15. Protein was quantified by the Lowry assay using the BioRad DC kit (BioRad #500-0111). Glucose and glycogen were quantified with the Sigma Glucose (GO) assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich # GAGO20-1KT): glucose homogenates were assayed directly from TE-buffered homogenates, whilst glycogen was digested to glucose in a 30 minute incubation at 30°C with 5 µl amyloglucosidase solution (Sigma # A7420 at 1 U ml−1), before subtracting the previous glucose reading. TAG was quantified using the Sigma Triglyceride Assay kit (TR0100-1KT), in which glycerol content is determined before and after digestion with supplied Triglyceride Reagent. Triglyceride content was determined as difference in glycerol content between the triglyceride-digested and undigested measurements of glycerol.

Wolbachia status of the flies

DNA was isolated from adult flies by the salting out method48 for most DGRP lines used in this study and for all P-element insertion mutants and backgrounds. Pools of 5 males were homogenised in 180 µl lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1.2% Triton X-100, with 20 mg lysozyme ml−1) with a sterile pestle, incubated at 37°C for 60 min., and vortexed with 100 l 0.1mm glass beads (Scientific Industries SI-BG01) for 5 min. 20 l 10× extraction buffer (2 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, 2.5 M NaCl, 250 mM EDTA, 5% (w/v) SDS) was added to the samples, which were mixed with 10 l 20 mg proteinase K ml−1 (Qiagen) and incubated at 55°C for 60 min. 100 µl 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) were added to each sample before incubation at −20°C for 10 minutes. Samples were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 5,000 g and 4°C. 300 µl isopropanol (cooled to −20°C) were then added to the supernatant, mixed, and then incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes. Following 30 minutes centrifugation at 5,000 g at room temperature, the pellets were rinsed in 500 µl 70% ethanol (cooled to −20°C), vortexed, centrifuged for 5 minutes at 5,000 g and room temperature, and resuspended in sterile Milli-Q water. Wolbachia-specific primers Wsp81F and Wsp691R (5'-AAA AAT TAA ACG CTA CTC CA, 5'-TGG TCC AAT AAG TGA TGA AGA AAC)49 were used for specific detection of Wolbachia in duplicate samples. PCR reactions (25 µl) contained: 20.575 µl ddH2O, 2.5 µl buffer, 0.25 µl 20 µM Wsp81F primer, 0.25 µl 20 µM Wsp691R primer, 0.3 µl 20 mM dNTPs, 1 µl 50 mM MgCl2, 0.125 µl Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (5 U μl−1), and 0.5 µl template DNA (2–100 ng µl−1). Cycle parameters were: 95°C for 5 min; 30 cycles of 60 s 95°C, 60 s 54°C, 60 s 72°C; and final extension 60 s 95°C, 5 min at 72°C. There was high congruence between our detection of Wolbachia and previous descriptions of DGRP Wolbachia status19.

Quantitative and GWA analyses

All data were analysed in R (v3.0.2). The phenotypic traits were analyzed with mixed models using the lme function from the nlme library50,51, excluding any row of the data matrix with missing data points. The interactive effect of microbiota and Wolbachia as binary factors was analyzed with genotype nested within experimental block as a random factor. Mean line dry weight was an additional covariate for the other indices. The interaction of microbiota and Wolbachia was simplified where the Wolbachia term was not significant. Full statistical analysis is presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Response indices were calculated for each trait as the difference between mean axenic and gnotobiotic values for the trait in each line, divided by the difference in mean of axenic and gnotobiotic trait value across all lines38. To calculate correlations between traits, nutritional traits were normalized to line mean dry weight within each microbiota condition, so weight was excluded from these analyses to avoid autocorrelative artefacts. Significance of pairwise Pearson’s correlations were corrected for 10 multiple comparisons by Bonferroni correction.

To associate phenotypic traits with genetic variants, GWAs were conducted, using the data for all replicates. R scripts constructed specifically for this analysis so that all covariates could be fully accounted for. We associated traits with any marker that had a minor allele frequency greater than three in the pool of tested lines, giving a different subset of markers for each trait tested (number SNPs tested per trait: dry weight 1,881,661 SNPs; protein 1,805,384 SNPs; TAG 1,702,250 SNPs; glucose 1,977,756 SNPs; glycogen 1,447,725 SNPs). Models and numbers of DGRP lines used in each GWA are presented in Supplementary Table 8, and degrees of freedom in Supplementary Table 1. QQ plots of p-values from these associations were inflated above the null expectation (Supplementary Fig. 5) and could not be removed by model respecification or additional covariates (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 6). Inferences about function and expression of genes bearing significant SNPs were based on Flybase FB2013_0652.

Empirical validation of GWA

The validation experiments used flies with P-element insertion mutations in genes that included the 20 most significant SNPs and the five most significant non-synonymous SNPs in coding regions of genes associated with each trait. To exclude mutants with generally deleterious effects on fitness and condition we excluded from study genes in which lethal mutations are known, and balanced homozygous-lethal mutants. A total of 15 genes were tested after applying these criteria: five for TAG, four for glucose, five for glycogen, and one (rg) with predicted effects on both TAG and glycogen. Predictions were not validated for protein because only a single mutant was available according to these guidelines. The validation experiments were conducted on three replicate sets of five male flies in each of three separate experiments, by exactly the same procedures as in the GWAS except that dry weights of 5 individual flies per replicate were determined.

The effect of the microbiota on each mutant was analyzed, relative to a Wolbachia-status-matched background stock, by a linear mixed model (lme in R v3.0.2) accounting for genotype (mutant vs. background) as a fixed effect and experiment (n=3, 3 replicates per experiment) as a random effect. The effect was calculated separately for the mutant/background pair raised under each of axenic or gnotobiotic conditions: a significant effect of genotype of (p<0.025, i.e. correcting for two comparisons) under only one of axenic or gnotobiotic conditions indicated the mutant had a different response to the microbiota than the host. The ratio of the gnotobiotic:axenic index value in the mutant, relative to the ratio of the gnotobiotic:axenic index value of the background was calculated to display interactions among host genotype (mutant vs. background) and treatment (gnotobiotic or axenic).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank David Duneau, Søren Franzenburg, Brenda Gustin, Ginny Howick, Xiangfeng Jing, Susan Rottschaefer, Calum Russell, Robin Schwenke and Rob Unckless for their assistance in experiments. Nicolas Buchon provided advice in the design of mutant studies, and Julien Ayroles, Keegan Kelsey, Jason Mezey, Cornelia Scheitz and Rob Unckless provided valuable analytical support. Financial support was provided by NIH grant 1R01GM095372 and The Sarkaria Institute for Insect Physiology and Toxicology.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Conceived and designed experiments: AED, JMC, AJD, BPL and AGC. Conducted experiments: AJD, JMC, PDN, SLH, SW, DRS, LD, AC-NW, BPL. Analyzed data: AJD, JMC, AED.

Competing Financial Interest Statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.McFall-Ngai M, et al. Animals in a bacterial world, a new imperative for the life sciences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:3229–3236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218525110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Douglas AE. Symbiosis as a general principle in eukaryotic evolution. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2014;6:a016113. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sommer F, Backhed F. The gut microbiota--masters of host development and physiology. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 2013;11:227–238. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maynard CL, Elson CO, Hatton RD, Weaver CT. Reciprocal interactions of the intestinal microbiota and immune system. Nature. 2012;489:231–241. doi: 10.1038/nature11551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tremaroli V, Backhed F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature. 2012;489:242–249. doi: 10.1038/nature11552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mortha A, et al. Microbiota-dependent crosstalk between macrophages and ILC3 promotes intestinal homeostasis. Science. 2014 Mar 13;343:1249288. doi: 10.1126/science.1249288. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hooper LV, Macpherson AJ. Immune adaptations that maintain homeostasis with the intestinal microbiota. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010;10:159–169. doi: 10.1038/nri2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stecher B, Maier L, Hardt WD. 'Blooming' in the gut: how dysbiosis might contribute to pathogen evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013;11:277–284. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin J, et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2012;490:55–60. doi: 10.1038/nature11450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.vanNood E, Dijkgraaf MG, Keller JJ. Duodenal infusion of feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. New Eng. J. Med. 2013;368:2145. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1303919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hungin AP, et al. Systematic review: probiotics in the management of lower gastrointestinal symptoms in clinical practice -- an evidence-based international guide. Aliment. Pharmacol. Therapeut. 2013;38:864–886. doi: 10.1111/apt.12460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hardy H, Harris J, Lyon E, Beal J, Foey AD. Probiotics, prebiotics and immunomodulation of gut mucosal defences: homeostasis and immunopathology. Nutrients. 2013;5:1869–1912. doi: 10.3390/nu5061869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakula M. The persistence of a microbial flora during postembryogenesis of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Invert. Pathol. 1969;14:365–374. doi: 10.1016/0022-2011(69)90163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ridley EV, Wong AC, Douglas AE. Microbe-dependent and nonspecific effects of procedures to eliminate the resident microbiota from Drosophila melanogaster. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;79:3209–3214. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00206-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ridley EV, Wong AC, Westmiller S, Douglas AE. Impact of the resident microbiota on the nutritional phenotype of Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong AC, Dobson AJ, Douglas AE. Gut microbiota dictates the metabolic response of Drosophila to diet. J. Exp. Biol. 2014;217:1894–1990. doi: 10.1242/jeb.101725. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin SC, et al. Drosophila microbiome modulates host developmental and metabolic homeostasis via insulin signaling. Science. 2011;334:670–674. doi: 10.1126/science.1212782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Storelli G, et al. Lactobacillus plantarum promotes Drosophila systemic growth by modulating hormonal signals through TOR-dependent nutrient sensing. Cell Metab. 2011;14:403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mackay TF, et al. The Drosophila melanogaster Genetic Reference Panel. Nature. 2012;482:173–178. doi: 10.1038/nature10811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jemc JC, Milutinovich AB, Weyers JJ, Takeda Y, Van Doren M. raw functions through JNK signaling and cadherin-based adhesion to regulate Drosophila gonad morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2012;367:114–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang W, et al. Natural variation in genome architecture among 205 Drosophila melanogaster Genetic Reference Panel lines. Genome Res. 2014;24:1193–1208. doi: 10.1101/gr.171546.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Broderick NA, Lemaitre B. Gut-associated microbes of Drosophila melanogaster. Gut microbes. 2012;3:307–321. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newell PD, Douglas AE. Interspecies interactions determine the impact of the gut microbiota on nutrient allocation in Drosophila melanogaster. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80:788–796. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02742-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong AC, Chaston JM, Douglas AE. The inconstant gut microbiota of Drosophila species revealed by 16S rRNA gene analysis. ISME. J. 2013;7:1922–1932. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chandler JA, Lang JM, Bhatnagar S, Eisen JA, Kopp A. Bacterial communities of diverse Drosophila species: ecological context of a host-microbe model system. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ikeya T, Broughton S, Alic N, Grandison R, Partridge L. The endosymbiont Wolbachia increases insulin/IGF-like signalling in Drosophila. Proc. Roy. Soc. B. 2009;276:3799–3807. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.0778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu VM, et al. Drosophila Varicose, a member of a new subgroup of basolateral MAGUKs, is required for septate junctions and tracheal morphogenesis. Development. 2007;134:999–1009. doi: 10.1242/dev.02785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindner JR, et al. The Drosophila Perlecan gene trol regulates multiple signaling pathways in different developmental contexts. BMC Develop. Biol. 2007;7:121. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamimura K, et al. Perlecan regulates bidirectional Wnt signaling at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. J. Cell Biol. 2013;200:219–233. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201207036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Volders K, et al. Drosophila rugose is a functional homolog of mammalian Neurobeachin and affects synaptic architecture, brain morphology, and associative learning. J. NeuroSci. 2012;32:15193–15204. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6424-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nair R, et al. Neurobeachin regulates neurotransmitter receptor trafficking to synapses. J. Cell Biol. 2013;200:61–80. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201207113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biteau B, Jasper H. Slit/Robo signaling regulates cell fate decisions in the intestinal stem cell lineage of Drosophila. Cell Rep. 2014;7:1867–1875. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis RL. Olfactory memory formation in Drosophila: from molecular to systems neuroscience. Ann. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;28:275–302. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flaherty MS, et al. chinmo is a functional effector of the JAK/STAT pathway that regulates eye development, tumor formation, and stem cell self-renewal in Drosophila. Dev. Cell. 2010;18:556–568. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benson AK, et al. Individuality in gut microbiota composition is a complex polygenic trait shaped by multiple environmental and host genetic factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A. 2010;107:18933–18938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007028107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parks BW, et al. Genetic control of obesity and gut microbiota composition in response to high-fat, high-sucrose diet in mice. Cell Metab. 2013;17:141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tims S, et al. Microbiota conservation and BMI signatures in adult monozygotic twins. ISME. J. 2013;7:707–717. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jordan KW, et al. Genome-wide association for sensitivity to chronic oxidative stress in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown EB, Layne JE, Zhu C, Jegga AG, Rollmann SM. Genome-wide association mapping of natural variation in odour-guided behaviour in Drosophila. Genes, Brain Behav. 2013;12:503–515. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Böhni R, et al. Autonomous control of cell and organ size by CHICO, a Drosophila homolog of vertebrate IRS1-4. Cell. 1999;97:865–875. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80799-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luong N, et al. Activated FOXO-mediated insulin resistance is blocked by reduction of TOR activity. Cell Metabolism. 2006;4:133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryu JH, et al. Innate immune homeostasis by the homeobox gene caudal and commensal-gut mutualism in Drosophila. Science. 2008;319:777–782. doi: 10.1126/science.1149357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Broderick NA, Buchon N, Lemaitre B. Microbiota-induced changes in Drosophila melanogaster host gene expression and gut morphology. mBio. 2014;5:e01117–e01114. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01117-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Login FH, et al. Antimicrobial peptides keep insect endosymbionts under control. Science. 2011;334:362–365. doi: 10.1126/science.1209728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Franzenburg S, et al. Distinct antimicrobial peptide expression determines host species-specific bacterial associations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A. 2013;110:E3730–3738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304960110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chu H, Mazmanian SK. Innate immune recognition of the microbiota promotes host-microbial symbiosis. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14:668–675. doi: 10.1038/ni.2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McFall-Ngai M, Nyholm SV, Castillo MG. The role of the immune system in the initiation and persistence of the Euprymnascolopes-Vibrio fischeri symbiosis. Sem. Immunol. 2010;22:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cenis JL, Perez P, Fereres A. Identification of aphid (Homoptera, Aphididae) species and clones by ran- dom amplified polymorphic DNA. Ann. Ent. Soc. Am. 1993;86:545–550. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou W, Rousset F, O'Neil S. Phylogeny and PCR-based classification of Wolbachiastrains using wsp gene sequences. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1998;265:509–515. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2013 URL http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D. Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version 3.1-117. 2014 http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marygold SJ, et al. FlyBase: improvements to the bibliography. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D751–D757. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.