Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Guidelines for falls risk assessment include functional performance although evidence supporting specific tests for predicting injurious falls is lacking. We investigated whether a performance battery/its components aid in predicting injurious falls.

DESIGN

Longitudinal analysis; prospective cohort study.

SETTING

Clinical site.

PARTICIPANTS

755 Boston area community-dwelling adults (mean ± SD: age=78.1 ± 5.4, 64.1% women, 77.6% white).

MEASUREMENTS

Baseline functional performance was determined by the SPPB measuring balance, gait speed, and 5 repeated chair stands. Fall history (past year) and efficacy in performing 10 daily activities without falling were assessed. Falls were assessed using a daily calendar over 4 years. Injurious falls were defined by fractures, sprains, dislocations, pulled or torn muscles, ligaments, or tendons or by seeking medical attention.

RESULTS

Poorest chair stand performance was associated with greater hazard of injurious falls compared to all other groups (HR [95% CI]: 1.96 [1.18–3.26], 1.65 [1.07–2.55], and 1.60 [1.03–2.48] for ≥16.7s vs. 13.7–16.6s, 11.2–13.6s, and <11.2s). SPPB did not predict injurious falls. Fall history predicted injurious falls (HR [95% CI]: 1.82 [1.39–2.39]); falls efficacy did not. Fall history and a slow chair stand (<16.7s) compounded 2-year cumulative incidence of an injurious fall (0.46, [0.34–0.58]) compared to positive fall history (0.29, [0.25–0.34]) or a slow chair stand alone (0.21, [0.13–0.30]).

CONCLUSION

An easily administered chair stand test may be sufficient for evaluating performance as part of a risk stratification strategy for injurious falls.

Keywords: falls, injury, aged, risk assessment

INTRODUCTION

Fall-related injuries among older adults are a major public health problem. Annually, 35–40% of community-dwelling adults aged ≥65 years fall, with 10% suffering serious injury.1 Fall-related injuries are a major source of mortality, morbidity, and disability and can lead to loss of independence.2,3 In 2000, $19.2 billion was spent on fall-related injuries in the U.S.4 This is expected to climb $32.4 billion by 2020.5

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has released an algorithm for Falls Risk Assessment and Interventions to aid in care planning and prevention.6 This algorithm recommends assessing fall history, falls self-efficacy (e.g. worrying about falling), and functional performance. These may inform clinical decisions on patient education, referral to exercise or prevention programs, or conduction of multifactorial risk assessments and interventions. Importantly, this algorithm was created to assess overall falls risk, although serious fall-related injuries have more direct consequences for health, function, and healthcare expenditures.

The algorithm evaluates three functional performance domains associated with falls7 and fall-related injuries2: gait, lower-extremity strength or chair stand performance, and balance. Various tests assess these domains, although limited evidence exists on which test is most predictive of injurious falls. Few studies have investigated how these tests perform in combination with other brief assessments like fall history or self-efficacy.8,9

The Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) captures each of these functional domains with established cutpoints predictive of disability and mortality in older adults.10,11 The SPPB is easily administered, requires little equipment, and can be completed in <10 minutes. Despite this, it has not been evaluated longitudinally as a predictor of fall-related injuries. Using the CDC Falls Risk Assessment and Interventions algorithm as a guide, we examined whether functional performance, with fall history and falls efficacy, predicts time to incident injurious falls. We hypothesized that with fall history and falls efficacy, the SPPB and/or its components would predict injurious falls.

METHODS

The Maintenance of Balance, Independent Living, Intellect and Zest in the Elderly (MOBILIZE) Boston study was designed to assess risk factors and mechanisms of falls in a cohort of 765 community-dwelling older adults living in the Boston area.12 Eligibility included age ≥70 years, ability to walk 20 feet without the aid of another person, and intention to stay in the Boston area for ≥2 years.13 Exclusions included moderate to severe cognitive impairment (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE]<18). Our analysis included 755 (98.7%) participants. Participants with <90 days of follow-up due to withdrawal (n=8) from the study or death (n=2) were excluded.

Injurious falls

Falls were defined as unintentionally coming to rest on the ground or another lower level not resulting from major health event (e.g. myocardial infarction) or an overwhelming external hazard (e.g. vehicular accident).14 Participants mailed daily falls calendars to the study site monthly.15 Falls were assessed during a maximum follow-up of 4.3 years. Associated injuries were ascertained via structured interview. Injurious falls were defined by fractures, sprains, dislocations; pulled or torn muscles, ligaments, or tendons; or by seeking medical attention. Falls data were obtained for 98.5% of follow-up months in the first year, 90.8% in the second year, 88.2% in the third year, and 81.2% in the fourth year.16

The SPPB

The SPPB is a well-established, reliable, and valid measure of lower-extremity performance.10,11 The battery includes a test of standing balance, a timed 4-meter usual paced walk, and a timed test of 5 repeated chair stands. Each test is scored from 0–4, with a maximum summed score of 12 for the 3 tests and higher scores representing better functioning. Scores were categorized based on previously validated cutpoints (Tables 1–2).10 The SPPB is predictive of disability, hospitalizations, and mortality in older populations.10,11

Table 1.

Hazard ratios for SPPB score, fall history, and falls efficacy predicting injurious falls

| Model 1: Without SPPB AIC= 2696.4 HR (95% CI) |

Model 2: With SPPB AIC= 2699.1 HR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Fall History (yes vs. no) | 1.82 (1.39–2.39)* | 1.84 (1.40–2.42)* |

| Falls Efficacy Scale (per SD) | 0.90 (0.80–1.02) | 0.92 (0.81–1.04) |

| SPPB Score (1–12) | ||

| 1–3 vs. 4–6 | -- | 0.63 (0.30–1.34) |

| 1–3 vs. 7–9 | -- | 0.89 (0.44–1.79) |

| 1–3 vs. 10–12 | -- | 0.98 (0.48–1.99) |

| 4–6 vs. 7–9 | -- | 1.39 (0.87–2.22) |

| 4–6 vs. 10–12 | -- | 1.53 (0.96–2.44) |

| 7–9 vs. 10–12 | -- | 1.10 (0.80–1.52) |

| Age | 1.03 (1.00–1.05)* | 1.02 (1.00–1.05) |

| Male sex | 0.77 (0.58–1.03) | 0.77 (0.58–1.03) |

| White race | 1.61 (1.11–2.33)* | 1.61 (1.11–2.33)* |

| Psychoactive drug use | 1.76 (1.11–2.80)* | 1.76 (1.11–2.80)* |

| Depression | 1.60 (1.03–2.74)* | 1.60 (1.03–2.47)* |

p<0.05. SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery; a greater score indicates better physical functioning. AIC = Akaike information criterion: lower values indicate better model performance. N= 32 (4.3%) for SPPB = 1–3, N = 68 (9.1%) for SPPB = 4–6, N = 204 (27.3%) for SPPB = 7–9, and N = 443 (59.3%) for SPPB = 10–12. Falls Efficacy Scale range: 1 (not at all confident) to 10 (extremely confident).

Table 2.

Hazard ratios for SPPB component scores, fall history, and falls efficacy predicting injurious falls

| Model 1: Gait speed AIC=2697.7 HR (95% CI) |

Model 2: Chair stands AIC=2309.5 HR (95% CI) |

Model 3: Balance AIC=2670.4 HR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Fall History (yes vs. no) | 1.80 (1.37–2.36)* | 1.79 (1.33–2.40)* | 1.79 (1.36–2.35)* |

| Falls Efficacy Scale (per SD) | 0.93 (0.82–1.06) | 0.93 (0.79–1.08) | 0.91 (0.79–1.03) |

| SPPB Component Scores (1–4) | |||

| 1 vs. 2 | 0.61 (0.25–1.50) | 1.96 (1.18–3.26)* | 1.54 (0.87–2.75) |

| 1 vs. 3 | 0.85 (0.35–2.06) | 1.65 (1.07–2.55)* | 1.08 (0.64–1.81) |

| 1 vs. 4 | 1.01 (0.41–2.47) | 1.60 (1.03–2.48)* | 1.35 (0.82–2.22) |

| 2 vs. 3 | 1.40 (0.87–2.26) | 0.84 (0.54–1.31) | 0.70 (0.43–1.15) |

| 2 vs. 4 | 1.66 (1.05–2.63)* | 0.81 (0.52–1.27) | 0.88 (0.56–1.39) |

| 3 vs. 4 | 1.19 (0.83–1.69) | 0.97 (0.68–1.37) | 1.26 (0.90–1.75) |

| Age | 1.02 (1.00–1.05) | 1.03 (1.01–1.06)* | 1.03 (1.00–1.05) |

| Male sex | 0.80 (0.60–1.07) | 0.69 (0.50–0.94) | 0.80 (0.60–1.07) |

| White race | 1.67 (1.15–2.42)* | 1.59 (1.07–2.38)* | 1.50 (1.04–2.17)* |

| Psychoactive drug use | 1.75 (1.10–2.79)* | 1.87 (1.16–3.01)* | 1.66 (1.04–2.64)* |

| Depression | 1.58 (1.02–2.44)* | 1.57 (0.93–2.64) | 1.59 (1.03–2.47)* |

p<0.05. SPPB=Short Physical Performance Battery; greater scores indicate better physical function. AIC=Akaike information criterion; lower scores indicate better model performance. Falls Efficacy Scale range: 1 (not at all confident) to 10 (extremely confident). Balance: 1=held side-by-side stand for 10s and semi-tandem stand for <10s (N= 57, 7.7%); 2=held semi-tandem stand for 10s and full-tandem for ≤3s (N=96, 13.0%); 3=held full-tandem for >3s and <10s (N=156, 21.1%); and 4=held full tandem for 10s (N=430, 58.2%). Gait speed: 1=<0.46 m/s (N=21, 2.8%); 2=≥0.46 and <0.65 m/s (N=70, 9.4%); 3=≥0.65 and <0.83 m/s (N=140, 18.7%); and 4=≥0.83 (N=516, 69.1%). Chair stand: 1=completed 5 in ≥16.7s (N=85, 12.8%); 2=completed 5 in ≥13.7 and <16.7s (N=129, 19.5%); 3=completed 5 in ≥11.2 and <13.7s (N=232, 32.7%), and 4=completed 5 in <11.2s (N=217, 32.7%).

Baseline characteristics

Baseline assessments included a home interview conducted by a trained research assistant, followed by a clinic assessment visit conducted within approximately 2 weeks of the interview. Fall history (yes/no) within the past year was assessed by self-report. Falls self-efficacy was measured using the Falls Efficacy Scale,17 for which participants were asked to rate their level of confidence from 1 (not at all confident) to 10 (extremely confident) to perform 10 daily activities without falling.

Covariates such as age, sex, race, body mass index (BMI), and baseline health conditions known and hypothesized to be related to falls and fall-related injuries were considered in the analysis.2,6 Psychotropic medication use (yes/no) included use of antidepressants, antipsychotics, hypnotics, benzodiazepines, and other sedatives. Cognitive impairment was defined as a score of <24 on the MMSE.13 Depression was assessed using a modified Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale.18,19 Vision was assessed with the Good-Light Chart Model 600A light box at a 10-foot distance;20 visual deficit was defined as scoring in the lowest quartile. Orthostatic hypotension was defined as a reduction of systolic blood pressure ≥20 mmHg or of diastolic blood pressure ≥10 mmHg within 3 minutes of standing.21 Sensory impairment was defined as being unable to feel a 10-g Semmes-Weinstein monofilament on the dorsum of either great toe.22

Statistical analysis

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were built to predict incident injurious falls. Covariates univariately related to injurious falls (alpha=0.1) were included in the models to prevent overfitting. Predictors fall history and falls efficacy score were adjusted for age, sex, race, psychotropic medication use, and depression;2,6 then SPPB or SPPB component scores were added as ordinal predictors in separate models. The Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used to determine goodness of fit. The proportional hazards assumption was checked by testing the relationship of the interaction between the predictors or covariates and the log of survival time with injurious falls (alpha=0.05). Cumulative incidence was calculated by risk group and plotted against follow-up time. Two sensitivity analysis were performed: one assessing the relationships between continuous functional performance (gait speed and chair rise time) and injurious falls using Cox proportional hazards regression; and a second using classification and regression tree (CART) analysis in R statistical software23 to determines the cutpoint from continuous performance most predictive of injurious falls. Analyses other than CART were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

The proportional hazards assumption was met. Participants had a median follow up time of 2.43 years (IQR: 1.40–3.23). Over the follow-up, 221 participants (29%) experienced ≥1 injurious fall. Out of the 755 participants 64.1% were women, 77.6% were white and the mean age was 78.1 ± 5.4 (mean ± SD) years.

Adjusting for covariates, fall history predicted incident injurious falls (HR [95% CI]: 1.82 [1.39–2.39]), while falls efficacy and SPPB score did not (Table 1). The group with the poorest chair stand performance (≥16.7s) had the greatest hazard of injurious falls compared to any other group (HR [95% CI]: 1.96 [1.18–3.26], 1.65 [1.07–2.55], and 1.60 [1.03–2.48] for 1 vs. 2, 3, and 4, respectively) (Table 2). However, inability to complete the chair stand (n=64) was not associated with greater hazard of injurious fall (HR [95% CI]: 1.07 [0.66–1.73] for 0 vs. 1–4). The second poorest performing gait speed group had a greater hazard of injurious fall than the highest performing group (HR [95% CI]: 1.66 [1.05–2.63]).

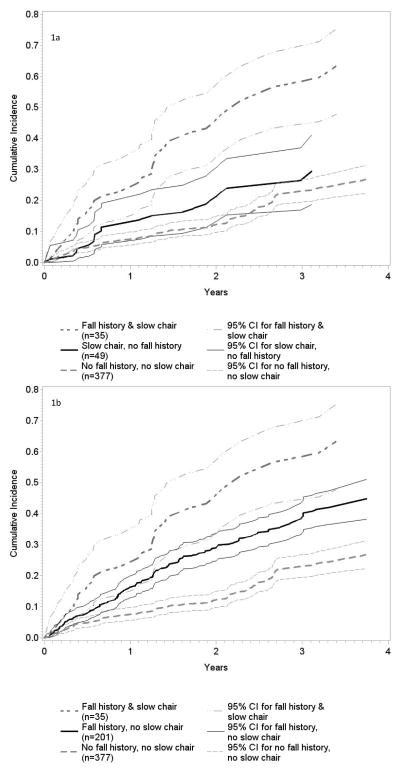

Since the worst performing chair stand group had the highest hazard of injurious falls and the chair stand model had the best goodness of fit, we assessed the cumulative incidence of an injurious falls when having a slow chair stand (score=1; ≥16.7s) and a fall history together and separately (Figure 1). A positive fall history and slow chair stand were associated with a 2-year cumulative incidence of 46% for an injurious fall compared to 12% for neither risk factor, 29% for a fall history alone, and 21% for a slow chair stand alone. Neither gait speed nor chair rise time were significant as continuous predictors of injurious falls (HR [95% CI]: 0.63 [0.33–1.20] and 1.02 [0.99–1.02], respectively). Using CART, the most predictive cutpoint of injurious falls in chair stand time was ≥15.5s.

Figure 1.

Figures 1a-1b: Cumulative Incidence of Injurious Falls by Risk Groups

Figure 1a shows the cumulative incidence rates of injurious falls across 4 years for the slow chair stand, no fall history risk group and Figure 1b shows the cumulative incidence rates for the fall history, no slow chair stand risk group. Both figures additionally show the cumulative incidence rates of the fall history & slow chair risk group and the no fall history, no slow chair risk group for comparison. Bold lines represent cumulative incident rates and fine lines represent upper and lower bounds for 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the cumulative incidence rates.

DISCUSSION

We determined the utility of a lower-extremity function measure as part of an injurious falls risk assessment strategy in older adults. Although SPPB score was not predictive of injurious falls in this cohort, a ≥16.7s cutpoint for the 5 repetition chair stand test was an independent predictor. Performing slower than this threshold and reporting ≥1 falls in the preceding year was associated with a compounded risk of injurious falls over 4 years. These findings both inform fall risk assessment recommendations and stratification guidelines and extend them to include fall-related injuries.

Multiple components of functional performance were assessed separately and in combination using the SPPB to evaluate injurious falls risk. Interestingly, the chair stand component of the SPPB performed better than the combined score, which includes balance and gait speed. This has important clinical implications, suggesting that a short, simple chair stand test, which may identify lower-extremity weakness, poor muscle power, and limitations in dynamic balance, may be sufficient for evaluating performance as part of a risk stratification strategy for injurious falls.

While to our knowledge, the SPPB has not been assessed as a predictor of injurious falls using prospective data, the chair stand test was evaluated as a predictor of falls and fall-related fractures retrospectively.24 The test was predictive of falls but not fall-related factures; although only 10 out of 101 participants experienced fractures, therefore lack of statistical power cannot be ruled out. In addition, previous studies have found that chair stand performance has been associated with recurrent falls,3,25,26 with one study reporting that chair stand performance was a better predictor of multiple falls than the one leg standing balance test and the Timed Up and Go test,26 and another study reporting that it had similar predictive validity to the alternate-step test and the six-meter-walk test.25 None of these studies evaluated the association of these tests with injurious falls.

When we examined the magnitude of the hazard ratios for chair stand performance predicting injurious falls, we noted a hazard ratio closer to 1 in the comparison of the poorest to the best performing group (1 vs. 4) than in the comparison of the poorest to the second poorest performing group (1 vs. 2). Previous findings from this study show that both those with high and low performance have higher rates of falls than those in the middle categories,27 perhaps suggesting that higher functioning may contribute to increased falls due to greater exposure to activities that may precipitate falls. Possibly those with poorer function are driving the significant relationship observed, while those with higher function are responsible for the unexpected trend in magnitude of the hazard ratios. Additionally, those unable to complete the chair stand test did not have an increased hazard of fall-related injury, which was unexpected since this group is likely the most impaired. One potential explanation is that this group’s impairment may decrease their mobility, which could lead to decreased exposure to situations in which falls might occur. Further investigation of fall-related injury risk is needed in these groups.

Having a slow chair stand and a fall history together was not only associated with a greater incidence of injurious falls compared to having neither risk factor, but also compounded a person’s risk of having an injurious fall compared to having either risk factor alone. This emphasizes the importance of assessing both fall history and functional performance when estimating risk for fall-related injury. Though there was some overlap in the confidence intervals for cumulative incidence in these risk groups, this is likely due to the relatively small number of participants in the slow chair stand and fall history risk group (n=35). Having only a positive fall history was also associated with a higher cumulative incidence of having an injurious fall compared to having neither risk factor. A slow chair stand without a positive fall history was associated with a marginally higher incidence, and was not significantly different than that of the low risk group, although this group may still include older adults with poor function who may be at future risk for injurious falls and other unfavorable outcomes. This group also had large confidence intervals likely due to fewer participants (n=49).

Once patients are stratified by basic risk factors, those identified as high risk should undergo a more comprehensive multifactorial risk assessments and treatment, if needed.6,28 Multifactorial assessments and treatment of patients identified as high risk of falling can lead to a 30–40% reduction of falls.29 Consistent with this multifactorial approach, we included additional risk factors for fall-related injury in our analysis and found that psychoactive medication use and depression were predictive, although they did not attenuate the effects of functional performance. More research is needed to evaluate whether multifactorial treatment strategies are similarly effective at preventing fall-related injuries.

A major strength of this study is the collection of longitudinal falls data through monthly calendars over a maximum follow-up of 4.3 years. For functional performance, we used previously defined cutpoints that have been validated in large populations of older adults, which may make them more generalizable.10 We performed sensitivity analyses testing whether continuous chair rise time and gait speed predicted injurious falls, which they did not, supporting our findings of a threshold effect with chair rise time. We also performed a CART analysis, which determines the most predictive cutpoint from a continuous measure. This resulted in a similar cutpoint of 15.5s in chair rise time. A potential future direction is to determine the predictive validity of each of these cutpoints in a separate study population.

Given its direct relationship with poor health, function, and increased healthcare expenditures, our outcome of serious fall-related injury is particularly salient to older adults, the healthcare system, and the economy at large. Much of the literature focuses solely on falls, ignoring resulting injuries. Risk factors that are specific to or have more relative importance with regard to fall-related injuries are crucial to include in studies focusing on risk assessment and treatment.

Limitations to this study include that specific findings may be limited to community-dwelling older adults and may not be generalizable to other populations, such as institutionalized or frail older adults, or those with significant cognitive impairments. Due to the small number of participants in the slow chair stand, fall history group and the slow chair stand, no fall history group, we may have had insufficient power to fully detect differences in cumulative incidence of injurious falls between these and other groups. In addition, injurious falls risk was only assessed at baseline and we acknowledge that participants’ functional status can fluctuate over time. However, our baseline assessment may help shed light on what can be predicted from a onetime medical assessment anywhere from 0 to 4 years down the line, as our figure illustrates. Finally, our analysis was designed to assess time to first injurious fall. An important future direction is to assess whether the SPPB or its components can stratify individuals at risk for multiple future injurious falls.

CONCLUSION

Our results show that the chair stand assessment predicts injurious falls and may have clinical utility when implementing a risk assessment and treatment strategies. This assessment is easy and quick to employ within a busy clinical practice. Our findings both support the use of current algorithms including measures of fall history and functional performance, and extend the use of these tools to risk estimation of fall-related injury. Estimation of injurious falls risk has particularly important implications for prevention of disability and mortality in older adults 30 and reducing healthcare utilization and expenditures.4 Future studies should investigate the effectiveness of intervening on groups stratified by injurious falls risk and how treatment strategies should differ based on results from risk assessment.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING; This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging: Research Nursing Home Program Project #P01-AG004390, and Research Grants R01-AG026316 and R37-AG25037.

Sponsor’s Role: The funding institutes had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, and preparation of manuscript or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Presentation: An abstract reporting results from these data was accepted as a poster presentation to the International Society for Posture and Gait Research World Congress, Vancouver, CA, June 30, 2014

Author Contributions: Suzanne G. Leveille and Jonathan F. Bean were involved in study concept and design, acquisition of data, interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript. Alan M. Jette was involved in the study concept and design, interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript. Rachel E. Ward and Thomas Travison were involved in analysis and interpretation of data and preparation of manuscript. All other coauthors were involved in interpretation of data and preparation of manuscript.

Conflict of Interest:

Alan M. Jette, Jonathan F. Bean, and Suzanne G. Leveille declare grant support from the National Institute on Aging grant 5 R01-AG032052-03 and from the National Center for Research Resources in a grant to the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center grant 1 UL1-RR025758-01. Rachel E. Ward is supported by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research grant H133P120001. Marla K. Beauchamp is supported by a fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

References

- 1.Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR. The epidemiology of falls and syncope. Clin Geriatr Med. 2002;18:141–158. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(02)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tinetti ME, Doucette J, Claus E, et al. Risk factors for serious injury during falls by older persons in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:1214–1221. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Kidd S, et al. Risk factors for recurrent nonsyncopal falls. A prospective study. JAMA. 1989;261:2663–2668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevens JA, Corso PS, Finkelstein EA, et al. The costs of fatal and non-fatal falls among older adults. Inj Prev. 2006;12:290–295. doi: 10.1136/ip.2005.011015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Englander F, Hodson TJ, Terregrossa RA. Economic dimensions of slip and fall injuries. J Forensic Sci. 1996;41:733–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Algorithm for Fall Risk Assessment & Interventions. STEADI Tool Kit for Health Care Providers. 2012 http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/pdf/steadi/algorithm_fall_risk_assessment.pdf.

- 7.Ganz DA, Bao Y, Shekelle PG, et al. Will my patient fall? JAMA. 2007;297:77–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamb SE, McCabe C, Becker C, et al. The optimal sequence and selection of screening test items to predict fall risk in older disabled women: The Women’s Health and Aging Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:1082–1088. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.10.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nandy S, Parsons S, Cryer C, et al. Development and preliminary examination of the predictive validity of the Falls Risk Assessment Tool (FRAT) for use in primary care. J Public Health (Oxf) 2004;26:138–143. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdh132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: Association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M85–94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Pieper CF, et al. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: Consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance battery. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M221–231. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.4.m221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leveille SG, Kiel DP, Jones RN, et al. The MOBILIZE Boston Study: Design and methods of a prospective cohort study of novel risk factors for falls in an older population. BMC Geriatr. 2008;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The prevention of falls in later life. A report of the Kellogg International Work Group on the Prevention of Falls by the Elderly. Danish Med Bull. 1987;34 (Suppl 4):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tinetti ME, Liu WL, Claus EB. Predictors and prognosis of inability to get up after falls among elderly persons. JAMA. 1993;269:65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelsey JL, Procter-Gray E, Hannan MT, et al. Heterogeneity of falls among older adults: implications for public health prevention. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:2149–2156. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tinetti ME, Richman D, Powell L. Falls efficacy as a measure of fear of falling. J Gerontol. 1990;45:P239–243. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.6.p239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eaton W, Muntaner C, Smith C, et al. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Review and Revision (CESD and CESD--R) In: Maruish M, editor. The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment. Vol. 3. Mahwah NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts RE, Vernon SW. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Its use in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:41–46. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wood KM, Edwards JD, Clay OJ, et al. Sensory and cognitive factors influencing functional ability in older adults. Gerontology. 2005;51:131–141. doi: 10.1159/000082199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, pure autonomic failure, and multiple system atrophy. The Consensus Committee of the American Autonomic Society and the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 1996;46:1470. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.5.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perkins BA, Olaleye D, Zinman B, et al. Simple screening tests for peripheral neuropathy in the diabetes clinic. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:250–256. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kabacoff RI. Tree-Based Models. [Accessed July 8, 2014];Quick-R. 2014 http://www.statmethods.net/advstats/cart.html.

- 24.Zhang F, Ferrucci L, Culham E, et al. Performance on five times sit-to-stand task as a predictor of subsequent falls and disability in older persons. J Aging Health. 2013;25:478–492. doi: 10.1177/0898264313475813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tiedemann A, Shimada H, Sherrington C, et al. The comparative ability of eight functional mobility tests for predicting falls in community-dwelling older people. Age Ageing. 2008;37:430–435. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buatois S, Miljkovic D, Manckoundia P, et al. Five times sit to stand test is a predictor of recurrent falls in healthy community-living subjects aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1575–1577. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quach L, Galica AM, Jones RN, et al. The nonlinear relationship between gait speed and falls: The Maintenance of Balance, Independent Living, Intellect, and Zest in the Elderly of Boston Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1069–1073. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03408.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sherrington C, Tiedemann A, Fairhall N, et al. Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: An updated meta-analysis and best practice recommendations. New South Wales Public Health Bull. 2011;22:78–83. doi: 10.1071/NB10056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang JT, Morton SC, Rubenstein LZ, et al. Interventions for the prevention of falls in older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMJ. 2004;328:680. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7441.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Magaziner J, Simonsick EM, Kashner TM, et al. Predictors of functional recovery one year following hospital discharge for hip fracture: A prospective study. J Gerontol. 1990;45:M101–107. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.3.m101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]